Brawner v. Smith Brief for the Respondent in Opposition

Public Court Documents

September 19, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brawner v. Smith Brief for the Respondent in Opposition, 1969. b4fc1345-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d1b2005a-a7de-4e37-b859-7aa8788cde88/brawner-v-smith-brief-for-the-respondent-in-opposition. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

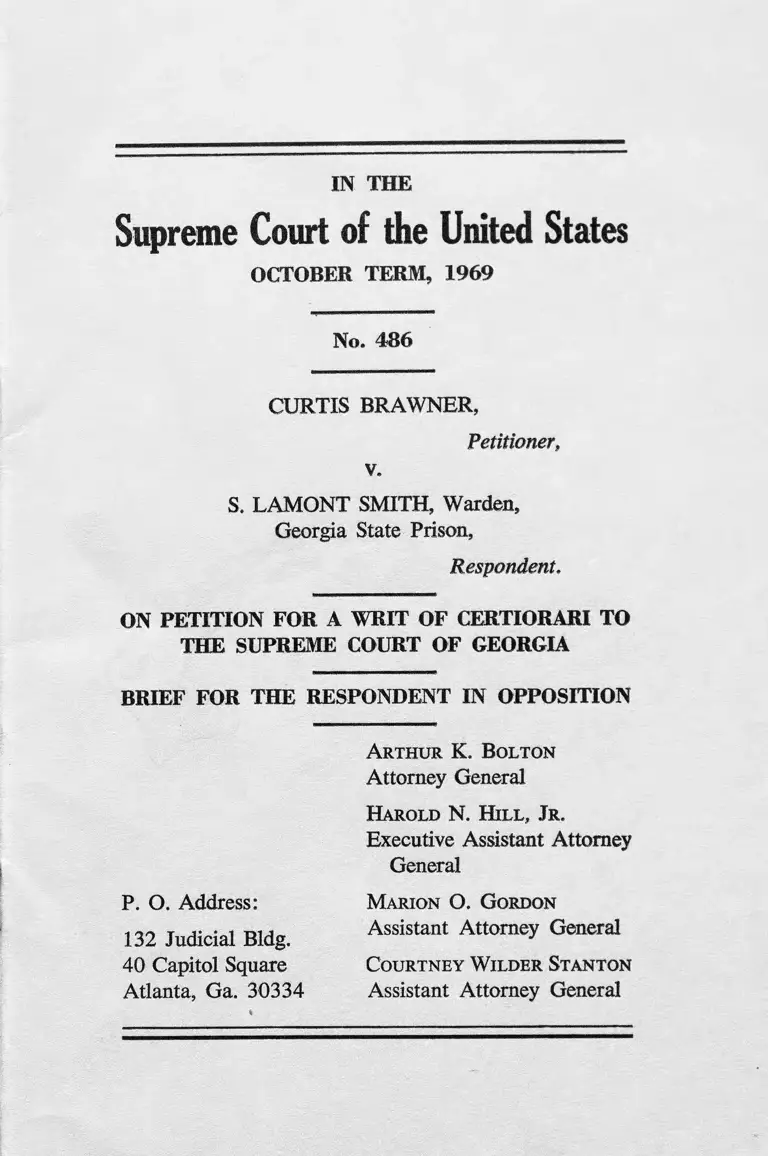

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 486

CURTIS BRAWNER,

Petitioner,

v.

S. LAMONT SMITH, Warden,

Georgia State Prison,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

P. O. Address:

132 Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Ga. 30334

Harold N. H ill , Jr .

Executive Assistant Attorney

General

Marion O. Gordon

Assistant Attorney General

Courtney Wilder Stanton

Assistant Attorney General

INDEX

OPINION BELOW

Page

_______ 1

JURISDICTION _______

QUESTIONS PRESENTED _________________ 2

1. The petitioner was indicted and convicted by

grand and traverse juries of Elbert County, Georgia,

which were drawn from jury lists selected from racially

designated tax digests. Does this fact establish a

prima facie case of systematic, racially based jury

exclusion within the evidentiary rule of Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, where the petitioner estab

lished the racial breakdowns of the jury lists but not

of the source from which the lists were composed___ 2

2. The petitioner was represented at his original

trial by a white, court-appointed trial counsel. Does

such a counsel’s considered decision not to challenge

jury-selection practices constitute a waiver binding on

the petitioner where the decision was considered by

counsel to be in his client’s best interests but where

the petitioner was not himself consulted_________2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED _________________ 2

STATEMENT ______________________________ 2

ARGUMENT ___________________________ ___ 4

CONCLUSION _____________________________ 12

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE________________ 13

i

Page

CASES CITED

Johnson v. Ferbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938)_________ 9

Jones v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967)----------------- 4

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932)__________ 9

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)________2,4

STATUTES

Ga. Code § 59-106 (1933) as amended,

Ga. L. 1955, p. 247___________ ___________ 3

Ga. Code § 59-106 (1965 Rev.)_____________ __ 3

Ga. Code § 92-6307 (1933)__________________ 3

INDEX— continued

ii

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 486

CURTIS BRAWNER,

Petitioner,

v.

S. LAMONT SMITH, Warden,

Georgia State Prison,

Respondent.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia, set

forth in the appendix to the petition, pp. la-6a, is re

ported at 225 Ga. 296 (1969).

JURISDICTION

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth

in the petition.

1

2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does the mere establishment of the racial break

downs of the petitioner’s jury lists without establishing

the racial breakdown of the source from which the lists

were composed establish a prima-facie case of sys

tematic, racially based jury exclusion within the evi

dentiary rule of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545?

2. Does the mere fact that a negro petitioner’s

court-appointed trial counsel was white impeach such

counsel’s considered decision not to challenge jury-selec

tion practices where the decision was considered by

counsel to be in his client’s best interests?

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional and statutory provisions involved

are adequately set forth in the petition.

STATEMENT

In general, the petitioner’s statement of the case as

set forth in his petition accurately reflects the history

of the prior proceedings. There are, however, significant

discrepancies in that portion which purports to discuss

the petitioner’s evidence at his State habeas-corpus pro

ceeding. The respondent’s statement is therefore limited

to that portion of the prior proceeding which the peti

tioner has summarized beginning with the final para

graph on page 4 of his petition and continuing through

the next-to-the-last paragraph on page 5 of the petition.

The statutory procedure in effect at the time of the

petitioner’s original trial required the jury lists to be

3

selected from the tax digests of the respective counties.

Ga. Code § 59-106 (1933), as amended, through Ga.

L. 1955, p. 247; Ga. Code Ann. § 59-106 (1965 Rev.).

At the time of the petitioner’s original trial, a statute

required that the tax digests be maintained on a racially

segregated basis. (Ga. Code § 92-6307 [1933]).

The petitioner presented evidence that based on the

1960 census, the population of Elbert County over

twenty-one years of age contained 3,474 white males,

3,843 white females, 1,272 non-white males, and

1,545 non-white females. (Tattnall County Transcript

22-24, 243; Petitioner’s Exhibit No. 2)* In percentage

terms, non-whites constituted approximately twenty-

seven per centum of the total population aged twenty-

one years or older as of the year of the census.

The petitioner introduced into evidence a certified

copy of the Elbert County jury lists for the years 1963-

64. (TCT 25, 244). It appeared that the 1963-64 jury

lists contained a total of 2,047 names, of which 26 were

non-whites. The petitioner’s mathematics are grossly in

error as an examination of the percentage computation

set forth in the first beginning paragraph on page 5 of

the petition will reveal. The petitioner’s evidence further

went to show that there were forty-eight names on the

trial-jury panel, of which two were negro. (TCT 40).

*The respondent does not have available the paginated, certified

record in this case. Consequently, he is forced to identify those

portions of the record relied upon in the most accurate, available

manner. Attempts to derive the pagination of the certified record

by reference to the petition have not been successful.

4

ARGUMENT

I. THE PETITIONER COMPLETELY FAILED

TO ESTABLISH THE PRIMA-FACIE CASE

OUTLINED IN WHITUS V. GEORGIA, 385 U.S.

545 (1967) AND DETAILED IN JONES V.

GEORGIA, 389 U.S. 24 (1967).

Before discussing the failure of the petitioner’s habeas-

corpus counsel to establish a prima-facie case in ac

cordance with the mode of proof authorized by Whitus

v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) and Jones v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 24 (1967), the respondent notes briefly that

the Georgia law did not prohibit or inhibit the estab

lishment of such a case. In fact, the Georgia Civil

Practice Act, Ga. Code Title 81A (1933), as amended,

is modeled after the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

In particular, the Georgia and Federal Rules for pre

trial evidentiary development, including admissions of

fact and genuineness of documents, axe virtually iden

tical. As a consequence, the establishment of the facts

necessary to show the prima-facie case under Whitus

and Jones would seem to be so simple as to allow every

such challenge to proceed to a decision on the merits.

Instead, in the present case, we have an agonizing

struggle consuming over 800 pages of record in an un

successful attempt to establish the facts activating

Whitus.

In the first place, the Court will search the record in

vain for the establishment of even a minutia of evidence

linking the 1963-64 jury lists to the petitioner’s 1965

trial. In other words, all we really have is a jury list

and a trial; there is absolutely no competent evidence

to establish that the jury panels drawn and called for

5

the trial of petitioner’s case were drawn from the 1963-

64 jury lists. In fact, there is testimony which would

indicate that some revision of the county’s jury lists

took place just prior to the commencement of the peti

tioner’s original trial. (TCT 45-6). The respondent

submits that it goes without saying that the decisions

in Whit us and Jones are both predicated upon a prima-

facie case being established by competent proof de

signed to show the actual jury lists utilized in selecting

the juries involved in the conviction under attack.

The simplicity of such proof suggests itself. All that

need be established would be the date of the subsequent

revision. This could be done without the necessity of

resorting to time-consuming testimonial evidence.

As things presently stand, this Court is without evi

dence upon which to base the decision requested by the

petitioner in view of the petitioner’s failure to estab

lish the racial breakdown of the traverse and grand

jury lists involved in his indictment and conviction.

A closely related failure of the evidence exists with

respect to the racial breakdown of the source. Here

again, the respondent reads Whitus and Jones as re

quiring that the actual source from which the jury lists

were taken be identified by competent evidence. In the

present case, an attempt was made to introduce certain

testimony relative to the 1963 tax digests. There is

absolutely no evidence that establishes whether the

1963-64 lists were based upon the 1963 digests. Normal

experience, however, during the period that the tax

digests constituted the source for jury selection, would

make this nexus highly questionable in that tax digest

preparation is not normally completed until relatively

6

late in the taxing year. Suffice it to say, that petitioner

failed to prove which tax digests were utilized in select

ing the jury lists from which his juries were drawn. Here

again, there is the complete failure of proof. The sim

plicity of such proof within the framework of Whitus

and Jones adequately suggests itself.

As an additional point, it might be well to note that

the petitioner actually fails to demonstrate the racial

breakdown of any tax digest. At the commencement of

the case, counsel for the petitioner indicated that a wit

ness who had been subpoenaed was not present. (TCT

5). The habeas-corpus court offered the petitioner’s

counsel a continuance. (TCT 6). The petitioner’s coun

sel elected to go ahead without the testimony of this

witness. (TCT 6). The petitioner’s attempt to introduce

secondary evidence was unsuccessful. (TCT 113). The

petitioner’s counsel then indicated a desire to offer a

certain deposition upon the point in question; however,

upon the interposing of certain objections relating to

the failure of the deponent to testify from an inde

pendent recollection the proffer was withdrawn. (TCT

117). The net result was a failure of the evidence to

establish the racial breakdown of any tax digest of El

bert County.

This Court is asked to grant this writ to review a

decision which is at best abstract. Because of this, the

present case cannot further illustrate the principle of

law most clearly established in the footnote to Jones.

In both Whitus and Jones there was competent proof

to establish the prima-facie case. In the present case,

there has not only been a failure to prove the case by

competent evidence, but an underlying failure to in

7

vestigate the relevant factual underpinnings with a full

appreciation of the tangible nature of the factors in

volved. This Court has announced a very simple method

whereby a negro can establish a prima-facie case of

constitutionally prohibited systematic racial exclusion.

The present morass has resulted from an unfortunate

failure of the petitioner’s present habeas-corpus counsel

to establish two of the five simple factors which con

stitute the accepted mode of proof.

II. THERE WAS A VALID, CONSCIENTIOUS

WAIVER BY THE PETITIONER’S COUNSEL

OF THE PETITIONER’S RIGHT TO CHAL

LENGE THE JURY-SELECTION PROCEDURES

EMPLOYED BY ELBERT COUNTY.

The language utilized by the petitioner’s counsel in

framing his second contention to this Court has the

unfortunate effect of raising by inference an issue hav

ing purely racist overtones not supported by even a

single shred of evidence. It would seem that the peti

tioner would have us believe that this whole question

should turn upon the racial identification of his original-

trial counsel. Petitioner has shown only that he is a

negro and that his court-appointed defense counsel was

a white attorney. From this, the Court is asked to

deduce and hold that the original-trial counsel pro

miscuously forfeited the rights of his negro client. Va

rious cases are cited all of which deal with operative

facts beyond the skin color of client and counsel. What

ever might have been the lamentable practice in other

cases, it is entirely unfair to make this accusation based

upon the petitioner’s representation by Attorney Wilbur

Orr.

8

The nature of the petitioner’s representation by Orr is

well documented in the record now before this Court.

The full transcript of the original trial is set out. (TCT

241/104-241/292; Petitioner’s Exhibit No. 1). Mr.

Orr’s attitude toward this case is well demonstrated by

his characterization upon deposition of the loss as “so

very painful.” (TCT 69). Further, there is evidence

that the counsel stayed with the case beyond the trial-

court level, filing a motion for a new trial and, sub

sequently, an appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

(TCT 60-70). The record further indicates that Orr

voluntarily associated with compensated counsel em

ployed by the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund in the

preparation of an application for a writ of certiorari to

this Court seeking the review of the original conviction.

(TCT 70). When this Court denied relief, Mr. Orr

testified that he sought commutation from the State

Board of Pardons and Paroles, and, when this was de

nied, he was prepared to seek habeas-corpus relief.

(TCT 70). Further, the record indicates that Mr. Orr

made two trips to Reidsville, Georgia, a distance in

excess of one hundred and fifty miles one-way in order

to file and argue the petitioner’s original State habeas-

corpus case. (TCT 70). Further, during the pendency

of federal habeas-corpus proceedings in the present mat

ter, Orr made two trips from Washington, Georgia, to

Atlanta for the purpose of testifying at depositions taken

on behalf of the petitioner. (TCT 28, 74). The impli

cation that because of the petitioner’s skin color the

original-trial counsel was less diligent or conscientious

in his efforts to defend the petitioner is totally unwar

ranted and should be purged from the petitioner’s pe

tition.

9

The question truly presented is whether any lawyer,

white or negro, was in a position to waive the jury-selec

tion question. There is some point where the guiding

hand of counsel must be allowed to conduct the case in

what conscientiously seems, based on the counsel’s ex

perience, to be the manner most favorable to the client.

If we are to turn over to the client every decision to

be made during the conduct of a trial, the effective coun

sel will soon be dissipated. The sixth amendment “em

bodies a realistic recognition of the obvious truth that

the average defendant does not have- the professional

legal skill to protect himself. . . .” Johnson v. Ferbst,

304 U.S. 458, 462, 58 S.Ct. 1019, 82 L.Ed. 1461

(1938). Every criminal defendant “requires the guiding

hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against

him. . . . If that be true of men of intelligence, how

much more true is it of the ignorant and illiterate, or

those of feeble intellect.” Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S.

45, 69, 53 S.Ct. 55, 77 L.Ed. 158 (1932).

In the present case, it is obvious that Orr’s client was

a person of limited intellectual capacity. (TCT 50, 223).

To require such a person to participate in the decisional

features of his representation is to place a burden upon

both the accused and his counsel which would neces

sarily detract from the representation. Trial counsel

must tap his wisdom, training, and experience in chart

ing the course which, in his considered judgment, is

most likely to produce the best result for the client. The

continued vitality of the sixth amendment’s “realistic

recognition of . . . (an) obvious truth” (Johnson v.

Ferbst, supra) requires that “the guiding hand of coun

sel” (Powell v. Alabama, supra) not be stayed while

10

the hapless client attempts to formulate a judgment

which he is ill-equipped to make. Implicit in the con

cept that a criminal defendant be guided by counsel

is the requirement that the lawyer must make decisions

related to trial strategy. Forcing the defendant to make

such decisions would reduce counsel to a mere vehicle

for the delivery of a position which might be sound, if

by chance, the client happened to decide the course

correctly.

It is obvious from the testimony upon which the peti

tioner relies that Mr. Orr made a deliberate, con

scientious decision to attempt to submerge as much as

possible the racial issues which were unfortunately pres

ent as a result of the killing of a prominent white citi

zen by a negro. It is equally obvious that the motivating

factors did not have anything to do with Orr’s feeling

of being ostracized by his white peer group, as the

implication in the petition would have the Court be

lieve. Rather, it was a conclusion reached on the basis

of what was best for this particular client. It is to be

noted that among the portions relied upon by the peti

tioner in his petition there is contained the testimony

of Mr. Orr to the effect that a challenge to the array

on the ground of racial exclusion would not inure to

the benefit of the petitioner even if successfully main

tained. Orr’s decision to attempt to submerge the racial

issue by waiving the right to file such a challenge was

not only professional but most probably correct. Such

a challenge would only have been advisable if it would

have been beneficial to the client. In the present case,

there was substantial evidence to indicate that the hos

tility against this particular petitioner was not limited

to the white community. (TCT 49, 238).

Cases are continually being framed in which the

strategy adopted by a defense counsel is sought to be

impeached on habeas-corpus applications. Ofttirries, as

here, these decisions are not easily made even by ex

perienced counsel. Particularly where the client is of

limited intellectual capacity, the necessity for making

such decisions is ultimately that of the attorney. If the

right to counsel is to be meaningful, the conscientious

decisions of trial counsel not to engage in preliminary

scrimmages not likely to aid the client’s long-range in

terests in the outcome of the litigation must be upheld,

even where the client has a right to engage in such

preliminary scrimmages.

11

12

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

/s / Arthur K. Bolton

Arthur K. Bolton

Attorney General

/ s / Harold N. H ill , Jr .

Harold N. H ill , Jr .

Executive Assistant Attorney

General

/s / Marion O. Gordon

Marion O. Gordon

Assistant Attorney General

/ s / Courtney Wilder Stanton

Courtney Wilder Stanton

Assistant Attorney General

Please serve:

Courtney Wilder Stanton

P. O. Address:

132 Judicial Building

40 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

13

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have this day served a true

and correct copy of the foregoing upon counsel for the

petitioner, Messrs. Jack Greenberg, Norman C. Amaker

and James N. Finney, 10 Columbus Circle, New York,

New York 10019, and Messrs. Howard Moore, Jr. and

Peter E. Rindskopf, 859:1/2 Hunter Street, N.W., At

lanta, Georgia 30314, by depositing same in the United

States mail, properly addressed and postage prepaid.

This is to further certify that all parties required to

be served have been served.

This.day of September, 1969.

st___________

l- ( f} £ o L.D /Vi