Teague v. Lane Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 12, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Teague v. Lane Brief Amicus Curiae, 1988. 4c5bb1cd-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d1b7f77b-a9b0-4f22-a396-6516c0982e40/teague-v-lane-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed March 09, 2026.

Copied!

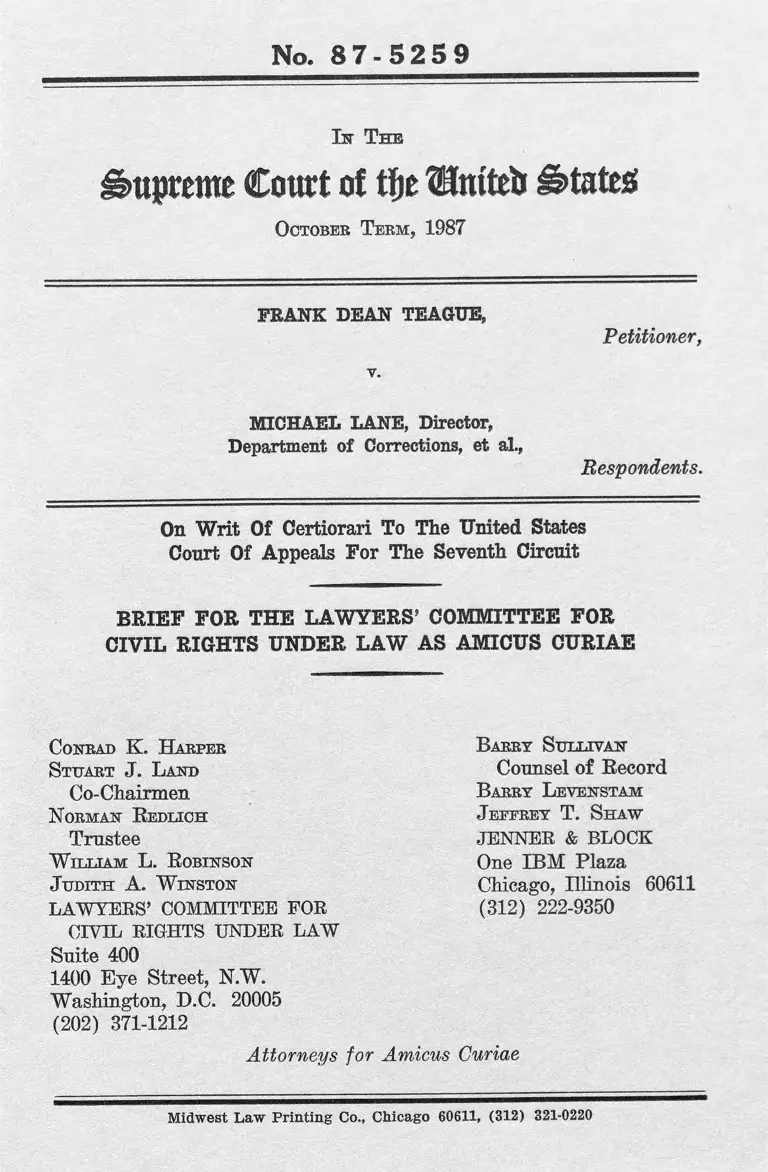

No. 8 7 - 5 2 5 9

I n T h e

Supreme Court ot tfjr lln te b S ta tes

O c to b er T e r m , 1987

FRANK DEAN TEAGUE,

V.

Petitioner,

MICHAEL LANE, Director,

Department of Corrections, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Seventh Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

C on r a d K. H a r p e r

S t u a r t J. L a n d

Co-Chairmen

N o r m a n R e d l ic h

Trustee

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

J u d it h A. W in s t o n

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

Suite 400

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

B a r r y S u l l iv a n

Counsel of Record

B a rry L e v e n s t a m

J e f f r e y T . S h a w

JENNER & BLOCK

One IBM Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60611

(312) 222-9350

A tto rn eys for Am ieus Curiae

Midwest Law Printing Co., Chicago 60611, (312) 321-0220

TABLE OF CONTENTS

P age

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................ iii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF

AMICUS CURIAE ........................................... 1

STATEMENT .............................................................. 2

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 5

ARGUMENT:

I.

THE STATE’S USE OF ALL ITS PEREM P

TORY CHALLENGES TO EXCLUDE 10 BLACK

VENIREM EN VIOLATED THE SIXTH AM END

MENT ................................................................................ 7

A . The Sixth Amendment Fair Cross-Section

Requirement Guarantees The “Fair Possi

bility” That The Petit Jury Will Reflect A

Fair Cross-Section Of The Community . . . 7

B . Because The Peremptory Challenge Is A

Non-Constitutional Privilege, Its Exercise

Is Strictly Subject To Constitutional Limi

tations ............................ 10

C . The Prosecutorial Use Of Peremptory Chal

lenges In A Manner That Undermines The

Fair Cross-Section Requirement Violates

The Sixth Amendment, And Must There

fore Be Subject To Limitation ............ 12

11

II.

RELIEF SHOULD BE GRANTED IN THIS

CASE UNDER BATSON BECAUSE PETI

TIONER HAS ESTABLISHED A PRIMA FACIE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT VIOLATION .. 15

A. Given The Fundamental Nature Of The

Right To The Equal Protection Of The

Laws, This Court Should Give Full Retroac

tive Effect To Batson ............... ............ 15

B . Because The Principles Established In Bat

son Protect And Enhance The Reliability

Of Criminal Trials, They Should Be Applied

Retroactively . . ........................................ 19

C . Reliance On Swain v. Alabama After This

Court’s Denial Of Certiorari In McCray v.

New York Was Erroneous . . . . . . . . ------ 21

III.

WHEN THE PROSECUTOR OFFERED JUSTI

FICATIONS FOR HIS USE OF PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGES, THE TRIAL COURT SHOULD

HAVE CONSIDERED WHETHER THE JUSTI

FICATIONS WERE PRETEXTUAL ............. 24

CONCLUSION ....................................................... 28

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases P age

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) . . . 21

Allen v. Hardy, 106 S. Ct. 2878 (1986) (per curiam) ..

................................................................... 16, 19, 24

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978) ............... 8, 9

Barnette v. West Virginia St. Bd. o f Educ., 47 F.

Supp. 251 (S.D. W. Va. 1942) (3-judge court), affd,

319 U.S. 624 (1943) ........................................... 23

Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 108 S. Ct. 978 (1988)........ 25

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) . . . ........passim

Booker v. Jabe, 775 F.2d 762 (6th Cir. 1985), vacated,

106 S. Ct. 3289, opinion reinstated, 801 F.2d 871

(6th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 910

(1987) .................................................................. 13,23

Bowden v. Kemp, 793 F.2d 273 (11th Cir.), cert.

denied, 106 S. Ct. 3289 (1986) ......................... 22

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala.)

(3-judge court), affd, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) (per

curiam) ............................................................. 23, 24

Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393

(1932) ................................................................. 23

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992 (1983) ........... 18

Carter v. Jury Comm’n, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) ........ 13

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) ......... 21

Commonwealth v. Martin, 461 Pa. 289,336 A.2d 290

(1975) .................................................................. 11

Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461,387 N.E.2d

499, cert, denied, 444 U.S. 881 (1979) ............. 13

IV

Desist v. United States, 394 U.S. 244 (1969) ........... 15,16

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968) .......... 7, 8

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979)........ 5, 9, 14, 15

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ............. 23

Elkins v. United States, 364 U.S. 206 (1960) . . . . 27

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) ................ 5

Fields v. People, 732 P.2d 1145 (Colo. 1987) ........ 13

Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d 509 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

108 S. Ct. 233 (1987) ........................................ 27

Griffith v. Kentucky, 107 S. Ct. 708 (1987) .......... 2, 16

Ivan V. v. City of New York, 407 U.S. 203 (1972)

(per curiam) ....................................................... 19

Jordan v. Lippman, 763 F.2d 1265 (11th Cir.

1985) ........... 22,23

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) ................... . 12

Lockhart v. McCree, 476 U.S. 162 (1986)............. 8

Lowenfield v. Phelps, 108 S. Ct. 546 (1988) . . . . . 18

Mackey v. United States, 401 U.S. 667 (1971) . . . 15, 16

Marhury v. Madison, 1 U.S. (1 Cranch) 267 (1803) .. 12

Martin v. Texas, 200 U.S. 316 (1906).................. 5

McCray v. Abrams, 576 F. Supp. 1244 (E.D.N.Y.

1983), a ffd in part and vacated in part, 750 F.2d

1113 (2d Cir. 1984) ............................................ 22

McCray v. Abrams, 750 F.2d 1113 (2d Cir. 1984),

vacated, 106 S. Ct. 3289 (1986) ................. 13, 15, 23

McCray v. New York, 461 U.S. 961 (1983) .. 7, 21, 22,23, 24

Norris v. United States, 687 F.2d 899 (7th Cir.

1982) ................................................................... 23

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319 (1937).......... 16, 17

V

Panduit Carp. v. All States Plastic Mfg. Co., 744 F.2d

1564 (Fed. Cir. 1984) (per curiam) ................... 25

People v. Frazier, 127 111. App. 3d 151, 469 N.E.2d

594 (1st Dist. 1984) .......................................... 11

People v. Johnson, 148 111. App. 3d 163, 498 N,E.2d

816 (1st Dist. 1986) ........................................... 11

People v. Teague, 108 111. App. 3d 891, 439 N.E.2d

1066 (1st Dist. 1982), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 867

(1983) ........... ..................................................... 2, 26

People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258,148 Cal. Rptr. 890,

583 P.2d 748 (1978) .................................... . 13

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972) ....................... 8

Prejean v. Blackburn, 743 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir.

1984) 23

Procter v. Butler, 831 F.2d 1251 (5th Cir. 1987) . 16

Riley v. State, 496 A.2d 997 (Del. 1985), cert, denied,

106 S. Ct. 3339 (1986) ...................................... 13

Roberts v. Russell, 392 U.S. 293 (1968) (per curiam) . 19

Roman v. Abrams, 822 F.2d 214 (2d Cir. 1987) .. 13

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545 (1979) ................... 17

Simpson v. Commonwealth, 622 F. Supp. 304 (D.

Mass. 1984), rev’d, 795 F.2d 216 (1st Cir.), cert,

denied, 107 S. Ct. 676 (1986)............... .......... 22

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ................. .. 17

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97 (1934)___ 17

Solem v. Stumes, 465 U.S. 638 (1984) ................. 21

State v. Gilmore, 103 N.J. 508, 511 A.2d 1150

(1986) ........................................... ..................... 13,23

State v. Neil, 457 So. 2d 481 (Fla. 1984)............. 13, 23

Stilson v. United States, 250 U.S. 583 (1919) . . . . 10

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) .. 5, 17

VI

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ........... passim

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975)___5, 6, 8, 9,17

Tenneco Chemicals v. William T. Burnett & Co., 691

F.2d 658 (4th Cir. 1983) .................................... 26

Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28 (1986) ................. 18

Ulster County Court v. Allen, 442 U.S. 140 (1979) .. 25

United States v. Clark, 737 F.2d 679 (7th Cir.

1984) .............................. ....................... ............ 23

United States ex rel. Palmer v. DeRobertis, 738 F.2d

168 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 924 (1984) .. 23

United States ex rel. Ross v. Franzen, 688 F.2d 1181

(7th Cir. 1982) (en banc) .................................... 25

United States v. Green, 742 F.2d 609 (11th Cir.

1984) .................................................................... 12

United States v. Hawkins, 781 F.2d 1483 (11th Cir.

1986) .................................................................... 22

United States v. Johnson, 457 U.S. 537 (1982) . . . 16

Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254 (1986) ............... 17

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous

ing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ............... 21

Vukasovich, Inc. v. Commissioner, 790 F.2d 1409

(9th Cir. 1986) ................................ 22

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ........... 21

Weathersby v. Morris, 708 F.2d 1493 (9th Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 464 U.S. 1046 (1984) ...................... 26

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970) ............. 8

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)........ 19, 20

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) .. 18

Yates v. Aiken, 108 S. Ct. 534 (1988) ................... 15,16

Vll

Constitutional Provisions, Rule, and Statute

U.S. Const, art. VI, cl. 2 ................................... 12

U.S. Const, amend. VI ........... ......................... passim

U.S. Const, amend. XIV ............. ..................... passim

Supreme Court Rule 36.2 ...................................... 2

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, f 115-4(e) (1985) ................. 3

Books and Articles

Adler, Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Jury Ver

dicts, 3 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 1 (1973) ..

Bell, Racism in American Courts: Cause for Black

Disruption or Despair?, 61 Calif. L. Rev. 165

(1973) ......... ................... ............................

Bernard, Interaction Between the Race of the De

fendant and That o f Jurors in Determining Ver

dicts, 5 L. & Psych. Rev. 103 (1979) ............. 20

Broeder, The Negro in Court, 1965 Duke L.J. 19 .. 20

Comment, A Case Study of the Peremptory Chal

lenge: A Subtle Strike at Equal Protection and

Due Process, 18 St. Louis U.L.J. 662 (1974) . 20

Davis & Lyles, Black Jurors, 30 Guild Prac. I l l

(1973) .................................................................. 20

Gerard & Terry, Discrimination Against Negroes in

the Administration of Criminal Law in Missouri,

1970 Wash. U.L.Q. 415 .................................... 20

Ginger, What Can Be Done to Minimize Racism in

Jury Trials?, 20 J. Pub. L. 427 (1971) ............ 20

Gleason & Harris, Race, Socio-Economic Status, and

Perceived Similarity as Determinants of Judg

ments by Simulated Jurors, 3 Soc. Behav. & Per

sonality 175 (1975) ............................................ 20

20

20

V lll

H. Kalven & H. Zeisel, The American Jury (1966) .. 20

McGlynn, Megas & Benson, Sex and Race as Fac

tors Affecting the Arbitration of Insanity in a

Murder Trial, 93 J, Psych. 93 (1976) ............. 20

J. Rhine, The Jury: A Reflection of the Prejudices

of the Community, in Justice on Trial 40 (D.

Douglas & P. Noble, eds. 1971) .. ...................... 20

Schaefer, Reducing Circuit Conflicts, 69 A.B.A. J.

452 (1983) ......... 18

R. Simon, The Jury and the Defense of Insanity

(1967) ................................ 20

Tussman & tenBroek, The Equal Protection o f the

Laws, 37 Calif. L. Rev. 341 (1949) ................. 17, 18

Ugwuegbu, Racial and Evidential Factors in Juror

Attribution of Legal Responsibility, 15 J. Experi

mental Soc. Psych. 133 (1979) ............................. 20

J. Van Dyke, Jury Selection Procedures: Our Un

certain Commitment to Representative Panels

(1977) .................................................................. 20

No. 8 7 - 5 2 5 9

In T he

Supreme (to rt af ttyz lEnftcb States

October T er m , 1987

FRANK DEAN TEAGUE,

Petitioner,

v.

MICHAEL LANE, Director,

Department of Corrections, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Seventh Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF

AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963, at the request of the President

of the United States, to involve private attorneys in the

national effort to assure the civil rights of all Americans.

- 2-

During the past 25 years, the Lawyers’ Committee and

its local affiliates have enlisted the services of thousands

of members of the private bar to address the legal prob

lems of minorities and the poor. The Committee’s mem

bership includes former presidents of the American Bar

Association, a number of law school deans, and many of

the nation’s leading lawyers. The importance to our crim

inal justice system of having criminal verdicts rendered

by juries untainted by discrimination, and the widespread

perception that prosecutors have practiced discrimination

in the exercise of peremptory challenges, prompted the

Lawyers’ Committee to file briefs amicus curiae in Bat

son v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986), and Griffith v. Ken

tucky, 107 S. Ct. 708 (1987). Similar concerns for the integ

rity of our criminal justice system have prompted the

Lawyers’ Committee to file a brief amicus curiae in this

case. The parties have consented to the filing of this brief,

which is therefore submitted pursuant to Supreme Court

Rule 36.2.

STATEMENT

Petitioner Frank Dean Teague, a black man, was con

victed of armed robbery and attempted murder by an all-

white Illinois state jury (J.A. 15). He was sentenced to

two concurrent terms of 30 years’ imprisonment. People

v. Teague, 108 111. App. 3d 891, 893, 439 N.E.2d 1066, 1068

(1st Dist. 1982), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 867 (1983).

Although the venire in petitioner’s case included 11

black veniremen, the State peremptorily struck 10 of

them, using each and every one of the 10 peremptory

- 3-

challenges then allowed by Illinois law. See 111. Rev. Stat.

ch. 38, 5 115-4(e) (1985).1 When petitioner objected to this

discrimination, the prosecutor volunteered a series of pur

portedly neutral explanations for excusing the 10 black

veniremen (J.A. 3-4). The trial court overruled petition

er’s objections, but made no finding as to the validity of

the prosecutor’s “explanations” (J.A. 4).

On appeal, the Illinois Appellate Court indicated that

the prosecutor’s “explanations” were dubious, but affirm

ed the conviction on the ground (Pet. App. A, at 2) that

petitioner had not shown the systematic exclusion in case

after case required by Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965). Following the denial of a petition for rehearing,

the Illinois Supreme Court denied leave to appeal (J.A.

15), and, in October 1983, this Court denied certiorari (J.A.

15).

In March 1984, petitioner filed a habeas corpus petition

in the United States District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Illinois. Petitioner claimed that the State had

violated his Sixth Amendment right to be tried by a jury

chosen from a fair cross-section of the community, and

his Fourteenth Amendment right to the equal protection

of the laws. The district court granted summary judgment

in favor of the State, holding that petitioner’s claims were

foreclosed by Swain and Seventh Circuit case law (J.A.

5-6).

On appeal, a divided panel of the Seventh Circuit held

that petitioner had established a prima facie violation of

the Sixth Amendment fair cross-section requirement and

1 The eleventh black venireman, the wife of a police officer, was

struck by petitioner, who was accused of the attempted murder

of police officers (Pet. 2-3).

—4

remanded the case for a hearing (Pet. App. A, at 24-30).2

The State filed a petition for rehearing en banc, which

was granted in December 1985 (J.A. 7-8). Subsequently,

while petitioner’s case was pending before the en banc

court, this Court announced its decision in Batson v. Ken

tucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). By divided vote, however, the

en banc court reversed the panel decision and affirmed

the decision of the district court (J.A. 36). First, the en

banc court held, as a matter of law, that the State’s dis

criminatory exercise of its peremptory challenges did not

violate the Sixth Amendment fair cross-section require

ment (J.A. 34-36). Second, the court held that this Court’s

decision in Batson did not apply to petitioner’s Fourteenth

Amendment claim, which was therefore controlled by

Swain (J.A. 16 & n.4). Finally, the court held that peti

tioner was not entitled to relief on his equal protection

claim because, even assuming that the claim was not

proceduraliy barred, petitioner had not established sys

tematic exclusion in case after case, as required by Swain

(J.A. 17 n.6).

On March 7, 1988, this Court granted certiorari (J.A.

54).

2 The Seventh Circuit panel ordered a remand because of the

“relative novelty” of its holding, but noted that, “on the present

facts, a remand would be unnecessary and perhaps undesirable in

allowing the state to conjure up a rationale having little to do with

the reality at trial if all parties at trial had prior notice of [the]

holding” (Pet. App. A, at 27-28).

- 5-

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

OF ARGUMENT

For more than a century, beginning with its decision

in Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880), this

Court has consistently condemned discrimination in jury

selection procedures because a criminal defendant has a

constitutional “right to be tried by a jury whose members

are selected pursuant to non-discriminatory criteria.” Bat

son, 476 U.S. at 85-86. See also Martin v. Texas, 200 U.S.

316, 321 (1906) (Fourteenth Amendment); Ex parte

Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345 (1880) (same); Duren v.

Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 363-64 (1979) (Sixth Amendment);

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 530 (1975) (same).

In Swain v. Alabama, the Court reaffirmed this

longstanding principle, but sought at the same time to

afford special protection to the S tate’s peremptory

challenge privilege by creating a presumption that the

State’s use of peremptory challenges be deemed proper

in any individual case. Swain, 380 U.S. at 221-22. Lower

courts subsequently interpreted Sivain as holding that

discrimination could be established in this context only

by proving its existence in case after case, and thus

precluded the granting of relief in any particular case (ab

sent such statistical evidence), even if the State’s

challenges in the particular case could not be explained

except as invidious discrimination. See Batson, 476 U.S.

at 92.

In Batson, this Court acknowledged the “crippling bur

den of proof” which Swain and its progeny had imposed

on defendants, and concluded that each defendant must

be allowed to prove discrimination on the facts of his own

case. Id. at 92-98. The Court therefore fundamentally

altered the balance which Swain had struck between the

■6-

peremptory challenge privilege and the constitutional right

to be free from invidious discrimination, and confirmed

the primacy of the latter.

In the case at bar, the Seventh Circuit improperly de

clined to give effect to Batson and the long line of cases

upon which its rationale is based. Indeed, the Seventh Cir

cuit expressly based its decision (J.A. 31-34) upon its view

of the peremptory challenge as a sacrosanct privilege

which need not give way to constitutional requirements.

Reversal is required for three separate reasons.

First, the State’s deployment of its peremptory chal

lenges violated the Sixth Amendment. Under the Sixth

Amendment, as this Court held in Taylor, 419 U.S. at

527, a criminal defendant is entitled to be tried by a jury

drawn from a fair cross-section of the community. While

the fair cross-section principle does not require that any

particular petit jury actually include members of any par

ticular group, it does ensure the “fair possibility” that

the jury will be comprised of various distinct community

groups, and thus prohibits the State from affirmatively

acting to subvert that possibility. Because the prosecutor’s

use of peremptory challenges effectively eliminated any

possibility that blacks could sit on the petit jury in this

case, petitioner established a prima facie violation of the

Sixth Amendment.

Second, the facts of this case established a prima facie

equal protection violation. Contrary to the Seventh Cir

cuit’s decision, petitioner was not required by Swain v.

Alabama to prove discrimination by showing exclusion in

case after case: (1) The Court’s decision in Batson is con

trolling here, rather than Swain, because a central pur

pose of Batson was to eliminate racial discrimination from

the criminal justice system, a goal which is central to our

“concept of ordered liberty” and thus requires retroac

tive treatment; (2) Batson, rather than Swain, must be

- 7-

applied to this case for the additional reason that Bat

son protects and enhances the truth-seeking goal of the

criminal justice system; and (3) Regardless of whether

retroactive application of Batson would otherwise be re

quired, such application is required in the extraordinary

circumstances of this case because the courts below per

functorily applied the Swain presumption after a majority

of this Court had indicated in McCray v. New York, 461

U.S. 961 (1983), that Swain should not be blindly followed.

Third, even if the Swain decision controls petitioner’s

equal protection claim, it was error for the trial court to

rely on the Swain presumption when the prosecutor ex

pressly invited the court to adjudge the validity of his

volunteered “explanations.”

ARGUMENT

I.

THE STATE’S USE OF ALL ITS PEREMPTORY CHAL

LENGES TO EXCLUDE 10 BLACK VENIREMEN VIO

LATED THE SIXTH AMENDMENT.

A. The Sixth Amendment Fair Cross-Section Requirement

Guarantees The “Fair Possibility” That The Petit Jury

Will Reflect A Fair Cross-Section Of The Community.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees to each criminal de-.

fendant the right to trial by an impartial jury of his peers.

U.S. Const, amend. VI.3 That right necessarily “con

3 It is indeed significant that Swain, a Fourteenth Amendment

equal protection case, was decided in 1965, three years before this

Court held that the Sixth Amendment was applicable to the states.

See Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 149 (1968). Thus, there

was no reason in Swain for this Court to test its holding in that

case against the requirements of the Sixth Amendment.

— 8—

templates a jury drawn from a fair cross section of the

community.” Taylor, 419 U.S. at 527. See also Williams

v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 100 (1970). In Taylor v. Loui

siana, this Court recognized that the “fair-cross-section

requirement [not only is] fundamental to the jury trial

guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment,” but is mandated

by the central purpose of the jury system, which is “to

guard against the exercise of arbitrary power—to make

available the commonsense judgment of the community

as a hedge against the overzealous or mistaken prosecutor

and in preference to the professional or perhaps over con

ditioned or biased response of a judge.” Taylor, 419 U.S.

at 530. See also Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145,

155-56 (1968).

This Court, of course, has never construed the fair cross-

section principle to require that any particular petit jury

include members of any particular group. Nonetheless, the

Court repeatedly has emphasized that the Sixth Amend

ment prohibits the State from acting affirmatively to

defeat the “fair possibility” that the petit jury will reflect

a fair cross-section of the community. Ballew v. Georgia,

435 U.S. 223, 239 (1978); Taylor, 419 U.S. at 528. See also

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 500 (1972); Williams, 399 U.S.

at 100. Indeed, the preservation of that “fair possibility”

is central to the integrity of the jury system because ex

clusion of groups “for reasons completely unrelated to the

ability of members of the group to serve as jurors in a

particular case . . . raise[s] at least the possibility that

the composition of juries would be arbitrarily skewed in

such a way as to deny criminal defendants the benefit

of the common-sense judgment of the community.” Lock

hart v. McCree, 476 U.S. 162, 175 (1986).

In giving effect to the Sixth Amendment, and, more spe

cifically, to guard against this kind of imbalance, this

Court has carefully restricted those State practices—

- 9-

whether intentional or not—which tend to exclude or

dilute representation of diverse community groups. In

Taylor v. Louisiana, for example, the Court invalidated

the conviction of a male defendant who had been tried

by a jury selected from a venire from which most women

had been excluded by statute. 419 U.S. at 538. See also

Duren, 439 U.S. at 370 (underrepresentation of women

on the venire violates the Sixth Amendment fair cross-

section requirement). Further, in Ballew v. Georgia, the

Court held that the Sixth Amendment prohibits the use

of a five-person petit jury in a criminal misdemeanor trial.

Although there was no suggestion in Ballew that the

venire did not represent a fair cross-section, the Court

nonetheless concluded that the size of the petit jury raised

an unconstitutional possibility that the jury might reach

an inaccurate or biased decision, or might not truly repre

sent the community. Ballew, 435 U.S. at 239.4

By restricting State action which eliminates or dilutes

the fair possibility that the jury will truly reflect the com

position of the community, the Sixth Amendment fair

cross-section requirement promotes the interests of plural

ism which are essential both to the integrity of our jury

system and to public confidence in it. See Taylor, 419 U.S.

at 530-31.

4 Although there was no majority opinion in Ballew, six members

of the Court believed that Georgia’s five-person jury violated the

Sixth Amendment. See 435 U.S. at 239 (Blackmun, J., joined by

Stevens, J.); id. at 245 (White, J.); id. at 246 (Brennan, J., joined

by Stewart and Marshall, JJ.). Moreover, the three remaining

members of the Court, Chief Justice Burger and Justices Powell

and Rehnquist, noted that the reduced size of the jury raised

“grave questions of fairness.” Id. at 245.

- 10-

B. Because The Peremptory Challenge Is A Non-Constitu

tional Privilege, Its Exercise Is Strictly Subject To Con

stitutional Limitations.

When used properly, the peremptory challenge, like the

fair cross-section requirement, promotes the integrity and

reliability of the jury system. It is well-established, how

ever, that there is no constitutional right to the exercise

of peremptory challenges. Batson, 476 U.S. at 91; Swain,

380 U.S. at 219; Stilson v. United States, 250 U.S. 583,

586 (1919). The peremptory challenge is solely a creature

of legislative grace, which must be schooled in constitu

tional ways.

In Swain, the Court sought to accommodate the diver

gent interests embodied in the constitutional right to be

free from invidious discrimination, on the one hand, and

in the State’s privilege of exercising peremptory chal

lenges, on the other hand. The Court reaffirmed that the

Constitution prohibits racial discrimination in jury selec

tion, but also emphasized the wide discretion which the

peremptory challenge historically has entailed. The Court

therefore held that the use of peremptory challenges in

any given case should be presumed proper, and not sub

ject to judicial scrutiny. 380 U.S. at 221-22. The Court

indicated, however, that discrimination in case after case

would require judicial scrutiny. Id. at 223-24.

Experience with the Swain presumption showed that

the balance struck in Swain was too one-sided, and effec

tively eviscerated constitutional protections. Contrary to

constitutional principles, prosecutors frequently exercised

their peremptory challenges to practice racial discrim

ination.5 At the same time, the “crippling” burden im

5 As this Court observed in Batson, “[t]he reality of practice,

amply reflected in many state and federal court opinions, shows

that the [peremptory] challenge . . . at times has been . . . used

(Footnote continued on following page)

- 11-

posed by Swain made it virtually impossible for criminal

defendants to enforce their constitutional rights. Batson,

476 U.S. at 92-93.

In Batson, the Court therefore reassessed the balance

struck in Swain. In doing so, the Court stated unequivo

cally that the peremptory challenge may be exercised only

within constitutional bounds, 476 U.S. at 89, and empha

sized anew that exclusion of jurors solely because of their

race is never constitutionally permissible, even in a single,

isolated case. Id. at 95. The practically insurmountable

presumption and burden of proof imposed by Swain had

effectively condoned discrimination in individual cases by

“largely immun[izing] [peremptory challenges] from consti

tutional scrutiny,” id. at 92-93, and thus tempted prose

cutors to locate an optimal level of discrimination (one

which would achieve their invidious purposes without trig

gering judicial scrutiny).6 Thus, the Batson Court adopted

5 continued

to discriminate against black jurors.” 476 U.S. at 99. Experience

in the State of Illinois shows that the Court’s observation in

Batson may well have understated the magnitude of the problem.

See People v. Frazier, 127 111. App. 3d 151, 156-57, 469 N.E.2d

594, 598-99 (1st Dist. 1984) (cataloguing 36 Illinois cases between

1980 and 1984, in which discriminatory use of peremptory chal

lenges by prosecutor was in issue); People v. Johnson, 148 111. App.

3d 163, 179 n.2, 498 N.E.2d 816, 826-27 n.2 (1st Dist. 1986) (cata

loguing 22 additional Illinois cases).

6 In other words, the practical effect of Swain was not to dis

courage prosecutors from practicing discrimination, but to en

courage them to practice discrimination with circumspection. Thus,

prosecutors refrained from discriminating in “case after case,” and

limited their discrimination to cases where it would matter most,

that is, where the prosecution’s evidence was weak and the facts

most susceptible to manipulations of racial prejudice. See Common

wealth v. Martin, 461 Pa. 289, 299, 336 A.2d 290, 295 (1975) (Nix,

J., dissenting) (“[t]he glaring weakness in the Swain rationale is

that it fails to offer any solution where the discriminatory use of

peremptory challenges is made on a selected basis”).

12-

a more effective means of ensuring constitutional compli

ance. Id. at 95. In doing so, the Court firmly rejected any

notion that the peremptory challenge is to be held in

violate, and confirmed that constitutional commands must

take precedence over non-constitutional privileges. See

U.S. Const, art. VI, cl. 2; Marbury v. Madison, 1 U.S.

(1 Cranch) 267, 285-86 (1803).

C. The Prosecutorial Use Of Peremptory Challenges In A

Manner That Undermines The Fair Cross-Section Re

quirement Violates The Sixth Amendment, And Must

Therefore Be Subject To Limitation.

Unless the State may accomplish through the indirec

tion of peremptory challenges what it cannot do directly

in empaneling a venire or legislating the size of the petit

jury—eliminate the fair possibility that the petit jury will

reflect a fair cross-section of the community—the Sixth

Amendment must be construed to impose limitations on

the use of peremptory challenges. Cf Lane v. Wilson, 307

U.S. 268, 275 (1939) (Frankfurter, J.) (the Constitution pro

hibits “sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of

discrimination”)- Otherwise, the fair cross-section require

ment would be a dead letter because the deployment of

peremptory challenges against a particular racial group

can undercut that requirement “to the same extent . . .

[as if the group] had not been included on the jury list

at all.” United States v. Green, 742 F.2d 609, 611 n.* (11th

Cir. 1984) (citations omitted).7 Two courts of appeals have

7 Indeed, this Court noted in Swain that peremptory challenges

have been used in this country with a greater vengeance than in

the United Kingdom because American jury pools are drawn from

“a greater cross-section of a heterogeneous society.” Swain, 380

U.S. at 218 (footnote omitted). In the case at bar, the Seventh

Circuit went so far as to assert that the fair cross-section require

ment “increases the necessity of employing peremptories” (J.A.

(Footnote continued on following page)

- 13-

recognized this fact and have imposed limitations, under

the Sixth Amendment, to prevent peremptory challenges

from being deployed as a means of abridging the fair

cross-section requirement. McCray v. Abrams, 750 F.2d

1113, 1130-31 (2d Cir. 1984), vacated, 106 S. Ct. 3289

(1986) ;8 Booker v. Jabe, 775 F.2d 762, 767-71 (6th Cir.

1985), vacated, 106 S. Ct. 3289, opinion reinstated, 801

F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 910

(1987) .9

If the fair cross-section requirement is to achieve its

constitutional purpose, each defendant must be allowed

to challenge the discriminatory use of peremptory chal

lenges in his own case, whenever their use eliminates or

substantially dilutes the participation of any particular

racial group on the petit jury.10 Consistent with this

1 continued

33; emphasis added). However, any suggestion that the peremp

tory challenge may properly be used to subvert the fair cross-

section requirement cannot stand. That requirement is both consti

tutionally mandated and grounded in “the very idea of a jury.”

Carter v. Jury Comm’n, 396 U.S. 320, 330 (1970).

8 In Raman v. Abrams, 822 F.2d 214, 225 (2d Cir. 1987), the Sec

ond Circuit reaffirmed the continued validity of McCray.

9 A number of state appellate courts have reached the same con

clusion. See People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258, 276-77, 148 Cal.

Rptr. 890, 903, 583 P.2d 748, 761-62 (1978); Fields v. People, 732

P.2d 1145, 1153-55 (Colo. 1987); Riley v. State, 496 A,2d 997, 1012

(Del. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 3339 (1986); State v. Neil, 457

So. 2d 481, 486-87 (Fla. 1984); Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass.

461, 488, 387 N.E.2d 499, 516, cert, denied, 444 U.S. 881 (1979);

State v. Gilmore, 103 N.J. 508, 526-29, 511 A.2d 1150, 1159-60

(1986) (all recognizing defendant’s right, under the Sixth Amend

ment or equivalent state constitutional provisions, to be tried by

a petit jury from which members of his race have not been

excluded).

10 It is well to remember that the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments serve different constitutional purposes by different means.

The Sixth Amendment focuses upon the composition of the venire

(Footnote continued on following page)

14-

Court’s holding in Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. at 364,

a prima facie violation of the fair cross-section require

ment should be found when:

(1) the prosecutor, through his use of peremptory

challenges, has excluded members of a distinct

racial group;

(2) the representation of the group in the remain

ing portion of the venire from which the jury

is selected is not reasonable in relation to the

number of group members in the community at

large; and

(3) the underrepresentation is due primarily to the

prosecutor’s use of peremptory challenges.!11]

10 continued

and its relationship to the petit jury. Thus, under the Sixth

Amendment, any defendant may challenge the underrepresenta

tion or exclusion (whether intentional or not) of any racial group.

Duren, 439 U.S. at 359 n.l, 368 n.26. On the other hand, the Four

teenth Amendment protects against discrimination and is con

cerned with the composition of the venire and its relationship to

the petit jury only insofar as they provide evidence relevant to

the ultimate question of discrimination. Thus, under the Four

teenth Amendment, a defendant may challenge only the intentional

exclusion of members of his own racial group. Batson, 476 U.S.

at 96. In some cases, therefore, the State’s racial manipulation of

the jury venire may violate the Fourteenth Amendment, but not

the Sixth Amendment. In other cases, the State’s actions may

violate only the Sixth Amendment. Thus, the constitutional pro

tections afforded by the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, re

spectively, are not redundant, and both must be given effect.

11 When a Sixth Amendment challenge is directed to the facial valid

ity of a statute, Duren also requires a showing of “systematic”

exclusion. 439 U.S. at 364. The case at bar, of course, does not

involve any facial challenge to the peremptory challenge statute,

and, thus, the “systematic” prong of Duren has no bearing here.

It is enough, as the Court observed in Batson, that “peremptory

challenges constitute a jury selection practice that permits ‘those

to discriminate who are of a mind to discriminate.’ ” 476 U.S. at

96 (citation omitted). At all events, to require something more in

terms of “systematic” discrimination effectively would make the

Sixth Amendment a dead letter, as Swain did with respect to the

Equal Protection Clause. See Batson, 476 U.S. at 92-93.

- 15-

Once a prima facie fair cross-section violation has been

established, the prosecutor must show that a “significant

state interest” was advanced by the deployment of his

peremptory challenges. Id. at 367. The prosecutor cannot

prevail, of 0010*86, merely by invoking race or group affili

ation because “[a] person’s race simply ‘is unrelated to

his fitness as a juror.’ ” Batson, 476 U.S. at 87, 97 (cita

tion omitted). Instead, the prosecutor must support his

actions by reference to some legitimate, racially neutral,

non-pretextual justification. See McCray v. Abrams, 750

F.2d at 1132.

The deployment of peremptory challenges in a manner

that subverts the fair cross-section guarantee must be sub

ject to these reasonable limitations because the peremp

tory challenge, as this Court unequivocally held in Batson,

476 U.S. at 89, cannot take precedence over fundamental

constitutional rights.

II.

R E L IE F SHOULD B E GRANTED IN THIS CASE UNDER

BATSON BECAUSE PETITIO NER HAS ESTABLISHED A

PRIM A FACIE FO U R TEEN TH AM ENDM ENT VIOLA

TION.

A. Given The Fundam ental N ature O f The R ight To The

Equal P rotection O f The Laws, This Court Should Give

F ull R etroactive E ffect To Batson.

Almost two decades ago, Justice Harlan, in two thought

ful dissenting opinions in Desist v. United States, 394 U.S.

244, 256-69 (1969), and Mackey v. United States, 401 U.S.

667, 675-702 (1971), articulated a set of principles to govern

the retroactive effect of new decisions of this Court.12 In

12 We recognize, of course, that Justice Harlan’s analysis has not

yet been fully adopted by this Court. See Yates v. Aiken, 108 S.

(Footnote continued on following page)

- 16-

the intervening 20 years, this Court has extensively recon

sidered the law of retroactivity, and has adopted many

of those principles. See, e.g., Yates v. Aiken, 108 S. Ct.

534, 537 (1988); Griffith, 107 S. Ct. at 713; United States

v. Johnson, 457 U.S. 537, 549 (1982).

In the process of resurveying the metes and bounds of

retroactivity law, this Court has not yet adopted Justice

Harlan’s view that newly announced constitutional rules

should be applied retroactively whenever they affect funda

mental rights, without regard to whether they represent

a “clear break” with the past. See Yates, 108 S. Ct. at

537; Griffith, 107 S. Ct. at 716 (Powell, J., concurring).

This case presents that opportunity.

In Mackey v. United States, Justice Harlan suggested

that new constitutional rules should be made fully retro

active “for claims of nonobservance of those procedures

that . . . are ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.’ ”

401 U.S. at 693 (Harlan, J., dissenting; quoting Palko v. 12

12 continued

Ct. 534, 537 (1988); Griffith, 107 S. Ct. at 716 (Powell, J., con

curring). Nonetheless, in addressing the retroactive application of

Batson, we believe that the logical force of Justice Harlan’s opin

ions in Desist and Mackey, and the extent to which the Court al

ready has adopted the principles articulated there, warrant con

sideration of these principles at the outset.

We also recognize that in Allen v. Hardy, 106 S. Ct. 2878, 2880

& n .l (1986) (per curiam), this Court summarily held, without full

briefing or oral argument, that Batson would not be applied retro

actively to those cases on collateral review which became final be

fore Batson was announced, and that the Court reached that con

clusion because Batson was a “clear break” with past precedent.

More recently, however, the Court in Griffith discarded the “clear

break” doctrine in determining the retroactive effect that Batson

should be accorded in cases that were pending on direct appeal

when Batson was decided. Griffith, 107 S. Ct. at 714. As the Fifth

Circuit recently noted, this Court’s decision in Griffith casts consid

erable doubt on the continued vitality of the rationale in Allen.

Procter v. Butler, 831 F.2d 1251, 1254-55 n.4 (5th Cir. 1987).

17-

Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319, 324-25 (1937) (Cardozo, J.)).

Under Justice Harlan’s view, retroactive application should

occur whenever the new rule implicates a “ ‘principle of

justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our

people as to be ranked as fundamental.’ ” 302 U.S. at 325

(quoting Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97, 105 (1934)).

The racial discrimination involved in Batson indisputably

implicated fundamental principles of justice, because “[dis

crimination on the basis of race, odious in all aspects, is

especially pernicious in the administration of justice,” Rose

v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545, 555 (1979), and is “at war with

our basic concepts of a democratic society and a represen

tative government.” Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130

(1940). See also Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. 254, 262

(1986); Taylor, 419 U.S. at 527. The remedy prescribed

in Batson is therefore informed by the most basic prin

ciples upon which our criminal justice system is founded.

For that reason, Batson is precisely the type of case to

which Justice Harlan’s view would grant full retroactive

effect.

Given the fundamental nature of the rights which Batson

protects, it would be improper to deny redress to those

who, solely due to the fortuities of the judicial process,

completed their direct appeals before Batson was decided.

The chronological details of petitioner’s appeals bear no

relation to whether he suffered the kind of discrimination

which this Court condemned over 100 years ago in Strauder,

condemned most recently in Batson, and, indeed, con

demned in every intervening equal protection case, includ

ing Swain.13 Moreover, there is no question here that

13 The central meaning of the Equal Protection Clause is, of

course, “that those who are similarly situated be similarly

treated.” Tussman & tenBroek, The Equal Protection of the Laws,

(Footnote continued on following page)

18-

petitioner was denied his fundamental right to the equal

protection of the laws.14 Because racial discrimination is

at war with our concept of ordered liberty, and nowhere

more so than in the context of our criminal justice system,

which is empowered to take our very lives and liberties,

the rule in Batson must be given retroactive effect.

13 continued

37 Calif. L. Rev. 341, 344 (1949). If, through the fortuities of the

judicial process, a case reached this Court on direct appeal before

the Court was prepared to announce the governing constitutional

principle, that fact cannot provide any principled basis for

distinguishing the case, or for denying to those who came first

the relief which the Court has now deemed necessary to redress

a fundamental constitutional violation. In fashioning a rule of

retroactivity applicable to such cases, it is well to remember that

“percolation” may be an indispensable part of our judicial process,

but, as Justice Schaefer has aptly observed, the Court also must

take care not to “ignore[ ] the impact of the law on real people.”

Schaefer, Reducing Circuit Conflicts, 69 A.B.A. J. 452, 454 (1983).

Indeed, many of the cases that reached this Court prior to Bat

son, when the Court (for its own institutional reasons) was not

yet ready to expound the Constitution, may well involve factual

circumstances far more susceptible to manipulation of racial prej

udice than was the case in Batson itself. Similarly, many of them

undoubtedly involve more serious penalties, such as capital punish

ment, where the Eighth Amendment’s heightened demand for im

partial fact-finding, untainted by racial prejudice or unfairness of

any kind, is manifest. See, e.g., Lowenfield v. Phelps, 108 S. Ct.

546, 551 (1988); Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S. 28, 35-36 (1986); Cali

fornia v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 998-99 (1983); Woodson v. North

Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305 (1976). One cannot reasonably assert

that the vindication of a criminal defendant’s right to have a jury

selected without racial discrimination should be nullified by his ar

rival on the steps of this Court before the doors were opened.

14 The prosecutor in this case used all of his peremptory chal

lenges to exclude blacks, and could muster only patently pretextual

explanations. See page 26, note 22, infra.

- 19-

B . B ecause The Princip les E stablished In Batson P rotect

And E nhance The R eliab ility O f Crim inal Trials, They

Should B e Applied R etroactively.

To preserve the integrity and reliability of the criminal

justice system, this Court has given retroactive applica

tion to new rules designed to enhance the reliability of

the trial. See Ivan V. v. City o f New York, 407 U.S. 203,

204 (1972) (per curiam); Roberts v. Russell, 392 U.S. 293,

294-95 (1968) (per curiam). In Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391

U.S. 510 (1968), for example, the Court held that the ex

clusion for cause of certain veniremen, merely because

they voiced general reservations about the death penalty,

violated the Due Process Clause. Id. at 522-23. In accord

ing full retroactive effect to this holding, this Court ob

served (id. at 523 n.22; citations omitted):

[W]e think it clear . . . that the jury-selection stan

dards employed here necessarily undermined “the

very integrity of the . . . process” that decided the

petitioner’s fate, . . . and we have concluded that

neither the reliance of law enforcement officials . . .

nor the impact of a retroactive holding on the ad

ministration of justice . . . warrants a decision against

the fully retroactive application of the holding we an

nounce today.

Just as the integrity and reliability of the criminal

justice process was undermined by the “stacking of] the

deck” in Witherspoon (id. at 523), the prosecutorial use

of peremptory challenges to skew the racial composition

of the petit jury in Batson similarly jeopardized its truth

seeking function. See Allen v. Hardy, 106 S. Ct. 2878,

2880-81 (1986) (per curiam). Indeed, if the exclusion of

blacks from petit juries were not thought to affect the

jury’s truth-seeking function, then prosecutors would not

have abused the peremptory challenge privilege, and the

- 20-

Batson decision would not have been necessary.15 But the

Batson decision was necessary, in large part to protect

and enhance the reliability of the criminal trial. In this

sense, Batson is indistinguishable from Witherspoon and

other decisions that this Court has deemed to warrant

retroactive application.16

15 Prosecutors discriminate against black veniremen for only one

reason, which goes to the very heart of the judicial process: they

believe that eliminating blacks from the jury panel will affect the

outcome of the case and make a conviction easier to obtain, a belief

which is well-founded on social science studies. See, e.g., H. Kalven

& H. Zeisel, The American Jury 196-98, 210-13 (1966); J. Rhine,

The Jury: A Reflection of the Prejudices of the Community, in

Justice on Trial 40, 41 (D. Douglas & P. Noble, eds. 1971); R.

Simon, The Jury and the Defense of Insanity 111 (1967); J. Van

Dyke, Jury Selection Procedures: Our Uncertain Commitment to

Representative Panels 33-35, 154-60 (1977); Adler, Socioeconomic

Factors Influencing Jury Verdicts, 3 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc.

Change 1, 1-10 (1973); Bell, Racism in American Courts: Cause

for Black Disruption or Despair?, 61 Calif. L. Rev. 165, 165-203

(1973); Bernard, Interaction Between the Race of the Defendant

and That of Jurors in Determining Verdicts, 5 L. & Psych. Rev.

103, 107-08 (1979); Breeder, The Negro in Court, 1965 Duke L.J.

19, 19-22, 29-30; Davis & Lyles, Black Jurors, 30 Guild Prac. I l l

(1973); Gerard & Terry, Discrimination Against Negroes in the

Administration of Criminal Law in Missouri, 1970 Wash. U.L.Q.

415, 415-37; Ginger, What Can Be Done to Minimize Racism in

Jury Trials?, 20 J. Pub. L. 427, 427-30 (1971); Gleason & Harris,

Race, Socio-Economic Status, and Perceived Similarity as Deter

minants of Judgments by Simulated Jurors, 3 Soc. Behav. & Per

sonality 175, 175-80 (1975); McGlynn, Megas & Benson, Sex and

Race as Factors Affecting the Attribution of Insanity in a Murder

Trial, 93 J. Psych. 93 (1976); Ugwuegbu, Racial and Evidential

Factors in Juror Attribution of Legal Responsibility, 15 J. Experi

mental Soc. Psych. 133, 143-44 (1979); Comment, A Case Study

of the Peremptory Challenge: A Subtle Strike at Equal Protec

tion and Due Process, 18 St. Louis U.L.J. 662, 673-83 (1974).

16 To the extent that prosecutors should now claim detrimental

reliance, that claim sounds hollow. This Court has never condoned

discrimination in jury selection, and the only change effected by

Batson was a change in the scheme of proof to be used in estab

lishing discrimination. Moreover, prosecutors cannot claim prejudice

(Footnote continued on following page)

- 21-

C. Reliance On Swain v. Alabama After This Court’s

Denial Of Certiorari In McCray v. New York Was Er

roneous.

Soon after this Court announced its decision in Swain

v. Alabama, it became clear that the Court’s attempt to

set the balance—between the constitutional freedom from

discrimination and the peremptory challenge privilege—

was a failed experiment. As Justice White noted in Batson,

prosecutorial discrimination was widespread after Swain.

476 U.S. at 101 (White, J., concurring). Moreover, as Justice

Powell noted, the evidentiary burden that Swain had im

posed upon criminal defendants was both “crippling,” 476

U.S. at 92, and doctrinally inconsistent with less onerous

evidentiary burdens developed in subsequent equal protec

tion cases. Id. at 93. See also Castaneda v. Partida, 430

U.S. 482, 494-95 (1977); Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266

(1977); Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 241-42 (1976);

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 630-32 (1972).

Indeed, the continuing vitality of Swain was seriously

questioned in the unprecedented opinions announced in

connection with this Court’s denial of certiorari in McCray

v. New York. In their dissent from that denial of cer

tiorari, Justices Marshall and Brennan expressed the view

that the Swain evidentiary burden was inappropriate, 461

U.S. at 968-69, and they urged plenary review “to re

examine the standard set forth in Swain.” Id. at 966.

Justice Stevens, joined by Justices Blackmun and Powell,

voted to deny the petition, but added (id. at 961-63): 16 *

16 continued

from having failed to preserve relevant information, when any such

failure was based, in turn, on some tactical advantage which, under

Swain and its progeny, prosecutors perceived to exist. This Court

has never held such “[ujnjustified ‘reliance’ [to be] . . . a bar to

retroactivity.” Solem v. Stumes, 465 U.S. 638, 646 (1984).

- 22-

My vote to deny certiorari . . . does not reflect dis

agreement with Justice Marshall’s appraisal of the im

portance of the underlying issue. . . . I believe that

further consideration of the substantive and pro

cedural ramifications of the problem by other courts

■will enable us to deal with the issue more wisely at

a later date. . . . In my judgment it is a sound exer

cise of discretion for the Court to allow the various

States to serve as laboratories in which the issue re

ceives further study before it is addressed by this

Court.[17]

Taken together, these two opinions clearly demonstrate

that a majority of the Court agreed in McCray that the

lower courts should undertake further analysis with re

spect to the problem of racial discrimination in jury selec

tion, and that Swain should not be followed blindly.

Numerous state and federal courts recognized that Swain

had been questioned,18 but few of them accepted the in-

17 In his opinion, Justice Stevens clearly invited the lower courts

to reexamine the issues involved in Swain and its progeny, to un

dertake an independent analysis, and to avoid a slavish or un

critical reliance on Swain. That this invitation was extended to

both the state courts and the lower federal courts is evidenced

by Justice Stevens’ observation that the absence of “conflict of

decision within the federal system” counseled in favor of postpon

ing plenary review. See 461 U.S. at 962. At least two federal

courts so interpreted this observation. See Simpson v. Common

wealth, 622 F. Supp. 304, 308 (D. Mass. 1984), rev’d, 795 F.2d 216

(1st Cir.), cert, denied, 107 S. Ct. 676 (1986); McCray v. Abrams,

576 F. Supp. 1244, 1246 (E.D.N.Y. 1983), affd in part and vacated

in part, 750 F.2d 1113 (2d Cir. 1984). Finally, Justice Stevens noted

in Batson, 476 U.S. at 110-11 n.4, that “[t]he eventual federal

habeas corpus disposition of McCray [v. Abrams], of course, proved

to be one of the landmark cases that made the issues in this case

ripe for review.”

18 See Vukasovich, Inc. v. Commissioner, 790 F.2d 1409, 1416 (9th

Cir. 1986); Bowden v. Kemp, 793 F.2d 273, 275 n.4 (11th Cir.), cert,

denied, 106 S. Ct. 3289 (1986); United States v. Hawkins, 781 F.2d

1483, 1486 (11th Cir. 1986); Jordan v. Lippman, 763 F.2d 1265,

(Footnote continued on following page)

•23

vitation to reexamine the issues involved, and virtually

all continued to follow Swain without any critical analysis.

Joining these ranks was the Seventh Circuit, which, within

a year of the denial of certiorari in McCray, declared that

Swain remained “controlling.” United States ex rel.

Palmer v. DeRobertis, 738 F.2d 168, 172 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied, 469 U.S. 924 (1984). See also United States v.

Clark, 737 F.2d 679, 682 (7th Cir. 1984).

In light of McCray, the mechanical reliance on Swain

by the courts below was error. By relying on questioned

authority when fundamental constitutional rights are at

stake, courts distort the doctrine of stare decisis, and,

more important, abdicate their essential obligation to up

hold the Constitution (Barnette v. West Virginia St. Bd.

of Educ., 47 F. Supp. 251, 253 (S.D. W. Va. 1942) (3-judge

court), affd, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)):

[judges] would be recreant to our duty as judges, if

through a blind following of a decision which the Su

preme Court itself has . . . impaired as an author

ity, we should deny protection to rights which we

regard as among the most sacred of those protected

by constitutional guaranties.[19]

is continued

1283 (11th Cir. 1985); Booker, 775 F.2d at 766-67; Prejean v. Block-

bum, 743 F.2d 1091, 1104 n .l l (5th Cir. 1984); McCray v. Abrams,

750 F.2d at 1116. See also State v. Neil, 457 So. 2d at 483-84; State

v. Gilmore, 103 N.J. at 518, 511 A.2d at 1154-55.

19 In constitutional cases, where erroneous decisions cannot be

cured by legislation, this Court has long recognized the duty of

the judiciary to “ ‘bow[ ] to the lessons of experience and the force

of better reasoning. . . .’ ” Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 671

n.14 (1974) (Rehnquist, J.; quoting Burnet v. Coronado Oil & Gas

Co., 285 U.S. 393, 407-08 (1932) (Brandeis, J., dissenting)). See also

Norris v. United States, 687 F.2d 899, 904 (7th Cir. 1982) (Posner,

J.) (“to continue to follow [doubtful precedent] blindly until it is

formally overruled is to apply the dead, not the living, law”);

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, 717 (M.D. Ala.) (3-judge court)

(Footnote continued on following page)

- 24-

To correct the lower courts’ misguided application of

stare decisis in this case, this Court should hold that con

tinued reliance on Swain after the denial of certiorari in

McCray warrants reversal.20

III.

WHEN THE PROSECUTOR OFFERED JUSTIFICATIONS

FOR HIS USE OF PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES, THE

TRIAL COURT SHOULD HAVE CONSIDERED WHETHER

THE JUSTIFICATIONS WERE PRETEXTUAL.

Even if this Court determines that Batson should not

be given retroactive effect, and that the courts below

properly continued to rely on Swain after the denial of

certiorari in McCray, petitioner still is entitled to a hear

ing on his equal protection claim.21 This is so because the

19 continued

(Rives, J.) (“[w]e cannot in good conscience perform our duty as

judges by blindly following the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson

. . . when our study leaves us [believing] . . . that the separate

but equal doctrine can no longer be safely followed as a correct

statement of the law”), ajfd, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) (per curiam).

20 This Court’s ruling in Allen v. Hardy has no bearing on the

foregoing argument, which focuses, not on the retroactive effect

that should be accorded to Batson, but on the precedential effect

to which Swain was entitled after this Court denied review in Mc

Cray. Moreover, Allen is inapposite because that conviction be

came final before the denial of certiorari in McCray, and the pres

ent contention was therefore unavailable in Allen.

21 The court below erred in concluding that the claim is pro-

cedurally barred (J.A. 17 n.6). At every level of the state and

federal proceedings, the State responded to petitioner’s claims by

contending that petitioner was raising an equal protection claim

controlled by Swain (J.A. 41 (Cudahy, J., dissenting)). Moreover,

because the Illinois Appellate Court and the federal district court

both rejected petitioner’s claim on the ground that he had failed

to demonstrate systematic exclusion under Swain (J.A. 41 n.2

(Cudahy, J., dissenting); J.A. 5-6), those courts specifically con

sidered and rejected the equal protection issue on the merits.

Thus, even if petitioner had not actually raised the issue at each

(Footnote continued on following page)

■25-

prosecutor in this case chose to waive the benefit of the

Swain presumption, and, instead, put the matter at issue

by volunteering “explanations” for his peremptory chal

lenges.

Presumptions generally are rooted in considerations such

as fairness, public policy, probability, and judicial econ

omy. Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 108 S. Ct. 978, 990 (1988).

Specifically, the Swain presumption was principally

grounded in the public policy concern that a prosecutor

should have wide discretion in exercising his peremptory

challenges in a particular case, without being forced to

explain his motives. See Swain, 380 U.S. at 222. However,

while the Swain presumption may have served an impor

tant purpose, presumptions cannot be applied mechanical

ly, without regard either to their purposes or to the par

ticular circumstances of the case. Courts “must not give

undue dignity to [this] procedural tool and fail to recognize

the realities of the particular situation at hand.” Panduit

Corp. v. All States Plastic Mfg. Co., 744 F.2d 1564, 1581

(Fed. Cir. 1984) (per curiam).

The “reality” here is that there was no principled rea

son for the courts below to have given effect to the Swain

presumption in the particular circumstances of this case.

By making a tactical decision to “explain” the reasons

for his peremptory challenges (and thus, perhaps, neutra

lize a trial judge who had doubtless noticed that all 10

of the prosecutor’s challenges had been deployed against

blacks), the prosecutor himself defeated the central pur- 21

21 continued

level in the state courts, the issue would now properly be before

this Court. See Ulster County Court v. Allen, 442 U.S. 140, 152-54

(1979); United States ex rel. Ross v. Franzen, 688 F.2d 1181, 1183

(7th Cir. 1982) (en banc). See also J.A. 41-42 & nn.1-2 (Cudahy,

J., dissenting).

- 26-

pose of this presumption. At that point, the presumption

should have disappeared.

Moreover, the prosecutor’s explanations themselves es

tablished racial discrimination.22 Certainly, the Swain pre

sumption of propriety was not intended to preclude judi

cial action in the face of admitted discrimination, as Justice

White, the author of Swain, confirmed in Batson. 476 U.S.

at 101 n.* (White, J., concurring). See also Tenneco Chem

icals v. William T. Burnett & Co., 691 F.2d 658, 663 (4th

Cir. 1983) (citations omitted) (“a party may not rely on

a presumption when evidence from its own case is incon

sistent with the facts presumed”). Similarly, the Swain

presumption should not be read to preclude judicial scru

tiny in the present case. The pretextual justifications of

fered by the prosecutor demonstrate racial discrimination

with force equal to that of an outright admission, and

therefore require judicial scrutiny.

Because there is no credible reason for giving effect to

the Swain presumption once the prosecutor has volun

teered his pretextual “reasons” for exercising his peremp

tory challenges, that presumption should not preclude judi

cial inquiry into the validity of those reasons. The Ninth

Circuit made this point in Weathersby v. Morris, 708 F.2d

1493, 1496 (9th Cir. 1983) (citation omitted), cert, denied,

464 U.S. 1046 (1984):

22 Judges Cudahy and Cummings were not the only judges to

remain unmoved by the prosecutor’s pretextual explanations (J.A.

48 & n.6 (Cudahy, J., dissenting)). The Illinois Appellate Court also

was unimpressed by the State’s justifications (People v. Teague,

108 111. App. 3d 891, 895, 908, 439 N.E.2d 1066, 1069-70, 1078 (1st

Dist. 1982), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 867 (1983)), and, indeed, none

of the judges who have heard this case has ever suggested that

the prosecutor’s explanations are credible.

- 27-

Cases where the prosecutor at trial volunteers his

or her reasons for using peremptory challenges . . .

present a situation distinguishable from Swain. . . .

Our reading of Swain, convinces us that in such cir

cumstances a court need not blind itself to the ob

vious and the court may review the prosecutor’s

motives to determine whether “the purposes of the

peremptory challenge are being perverted.”

In Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d 509, 511 (8th Cir.), cert,

denied, 108 S. Ct. 233 (1987), the Eighth Circuit also con

cluded that the presumption must fall away in such cir

cumstances because “the court has a duty to satisfy itself

that the prosecutor’s challenges were based on constitu

tionally permissible trial-related considerations, and that

the proffered reasons are genuine ones, and not merely

a pretext for discrimination.”

In these limited circumstances, inquiry into the prose

cutor’s volunteered explanations must be permitted if

courts are to avoid being made unwilling “accomplices in

the willful disobedience of a Constitution they are sworn

to uphold.” Elkins v. United States, 364 U.S. 206, 223

(1960). The lower courts’ mechanical invocation of the Swain

presumption therefore warrants reversal here.

- 28-

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit should be reversed and the cause

remanded.

Respectfully submitted,

C o n r a d K. H a r p e r

S t u a r t J. L a n d

Co-Chairmen

N o r m a n R e d l ic h

Trustee

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

J u d it h A. W in s t o n

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

Suite 400

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

B a r r y S u l l iv a n

Counsel of Record

B a r r y L e v e n s t a m

J e f f r e y T. S h a w

JENNER & BLOCK

One IBM Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60611

(312) 222-9350

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Dated: May 12, 1988