National Negro Business and Professional Commitee for the Legal Defense Fund

Press Release

March 25, 1967

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. National Negro Business and Professional Commitee for the Legal Defense Fund, 1967. 49e60aac-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d1c7f6e0-7c36-4184-8a4a-5211ee0c910f/national-negro-business-and-professional-commitee-for-the-legal-defense-fund. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

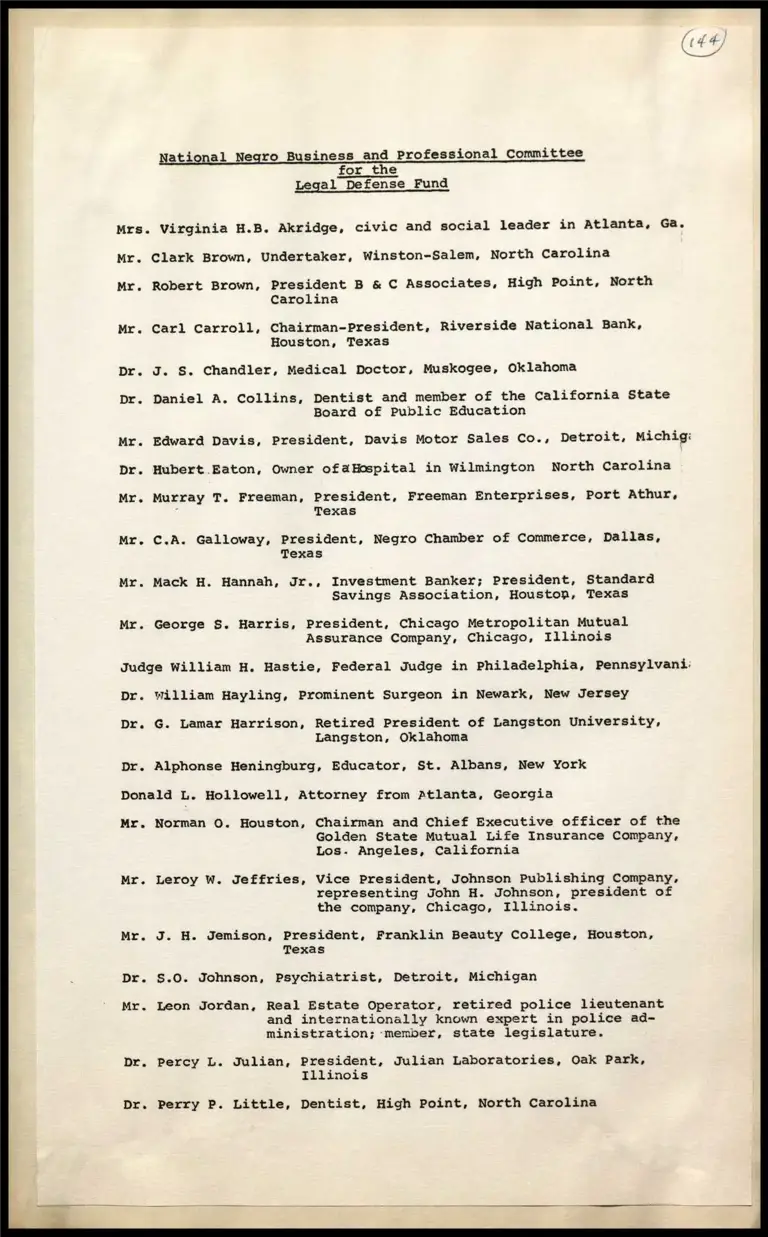

National Negro Business and Professional Committee

for the

Legal Defense Fund

Mrs. Virginia H.B. Akridge, civic and social leader in Atlanta, Ga.

Mr. Clark Brown, Undertaker, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Mr. Robert Brown, President B & C Associates, High Point, North

Carolina

Mr. Carl Carroll, Chairman-president, Riverside National Bank,

Houston, Texas

Dr. J. S. Chandler, Medical Doctor, Muskogee, Oklahoma

Dr. Daniel A. Collins, Dentist and member of the California State

Board of Public Education

Mr. Edward Davis, President, Davis Motor Sales Co., Detroit, Michig:

Dr. Hubert Eaton, Owner ofaHospital in Wilmington North Carolina

Mr. Murray T. Freeman, President, Freeman Enterprises, Port Athur,

Texas

Mr. C.A. Galloway, President, Negro Chamber of Commerce, Dallas,

Texas

Mr. Mack H. Hannah, Jr., Investment Banker; President, Standard

Savings Association, Houston, Texas

Mr. George S. Harris, President, Chicago Metropolitan Mutual

Assurance Company, Chicago, Illinois

Judge William H. Hastie, Federal Judge in Philadelphia, Pennsylvani

Dr. William Hayling, Prominent Surgeon in Newark, New Jersey

Dr. G. Lamar Harrison, Retired President of Langston University,

Langston, Oklahoma

Dr. Alphonse Heningburg, Educator, St. Albans, New York

Donald L. Hollowell, Attorney from Atlanta, Georgia

Mr. Norman 0. Houston, Chairman and Chief Executive officer of the

Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company,

Los. Angeles, California

Mr. Leroy W. Jeffries, Vice President, Johnson Publishing Company,

representing John H. Johnson, president of

the company, Chicago, Illinois.

Mr. J. H. Jemison, President, Franklin Beauty College, Houston,

Texas

Dr. S.O. Johnson, Psychiatrist, Detroit, Michigan

Mr. Leon Jordan, Real Estate Operator, retired police lieutenant

and internationally known expert in police ad-

ministration; ‘member, state legislature.

Dr. Percy L. Julian, President, Julian Laboratories, Oak Park,

Illinois

Dr. Perry P. Little, Dentist, High Point, North Carolina

ey

Mrs.

Dr.

Dr.

Alice R. Mollison, Widow of Judge Irving Mollison

Von D. Mizell, Surgeon and hospital owner in Fort Lauderdale

Florida

F. D. Moon, Executive of the Oklahoma Baptist Convention

J. Leslie Patton, Principal, Booker T. Washington Technical

High School, Dallas, Texas

F. H. Purnell, President, Fairchilds Purnell Mortuaries,

Houston, Texas

Judson W. Robinson, Sr., President, Judson Robinson & Sons

Mortgage Company, Houston, Texas

Carl Russell, President, Russell Funeral Home; also Mayor

Pro-Tem of Winston-Salem, North Carolina

George L. Shelton, Medical Doctor, Dallas, Texas

George Simkins, Dentist and civic leader, Greensboro, North

Carolina

J. J. Simmons, Sr., Independent oil producer in Oklahoma and

Nigeria, Muskogee, Oklahoma

H. H. Southall, President, Southern Aid Life Insurance Company,

Richmond, Virginia

Asa T. Spaulding, President, North Carolina Mutual Life

Insurance Company, Durham, North Carolina

J. S. Stewart, President, Mutual Savings & Loan Association,

Durham, North Carolina

R. B. Taylor, Sr., Physician, Okmulgee, Oklahoma

Julian B. Wilkins, Attorney and President of Seaway National

Bank, Chicago, Illinois

Business and professional leaders unable to attend because of

other commitments who nevertheless wrote, wired and called in

their pledges of support:

Judge Raymond Pace Alexander, Judge in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Mr.

Felton J. Capel, Mayor Pro-Tem, Southern Pines, North Carolina

Earl B. Dickerson, President, Supreme Liberty Life Insurance

Company of America, Chicago, Illinois

A. G. Gaston, President of Gaston Enterprises, Birmingham, Alab

Amos T. Hall, Attorney in Tulsa, Oklahoma

Ben Johnson, President, Ben Johr.son Funeral Homes, Natchitoches

Louisiana ;

John H. Johnson, President, Johnson Publishing Company, Chicago

Illinois

Mrs. Rose Morgan, President, House of Beauty, New York, New York

Mr.

Mr.

Maceo 0. Walker, Insurance Executive, Memphis, Tennessee

John H. Wheeler, President, Mechanics & Farmers Bank, Durham,

North Carolina