De Funis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. De Funis v. Odegaard Brief Amicus Curiae, 1973. 74cc1c90-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d2332b2f-0681-4b86-8c16-fbdd3082cc07/de-funis-v-odegaard-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

/

>

J

(

* J

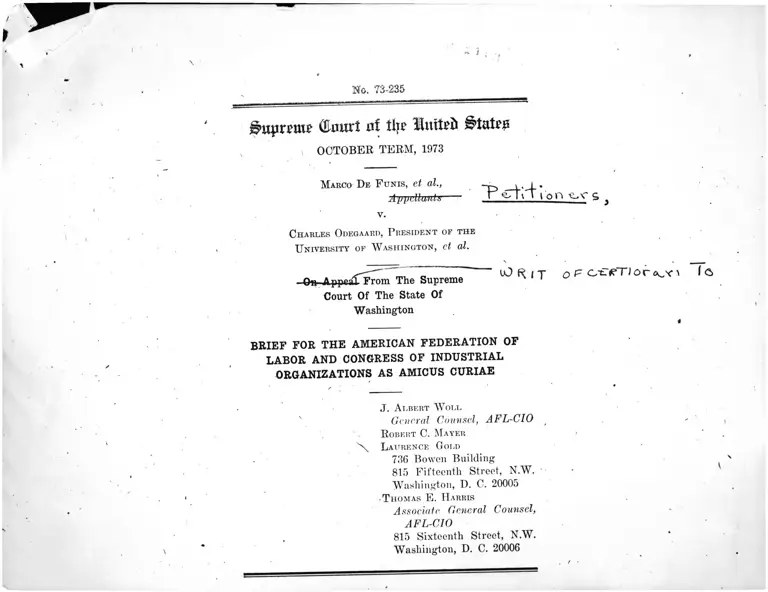

No. 73-235

■§>tuir£tu£ tourt at tlje Xnitrt States

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

M arco D e F unis, et al.,

Appellants

v.

Charles Odegaaro, P resident of the

U niversity of W ashington, ct al.

T c t i ' t i t on <l,<' 9

Q« Appeal From The Supreme

Court Of The State Of

Washington

uO f\; |-p O U Ct-^TIOr ck̂ x \ \ Q>

BRIEF FOR THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF

LABOR AND CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL

ORGANIZATIONS AS AMICUS CURIAE

J. A lbert W oll

General Counsel, AFL-CIO ;

R obert C. M ayer

'X L aurence Gold

736 Bowen Building

815 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

T homas E. H arris

Associate General Counsel,

AFL-CIO

815 Sixteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

t •

2

American Indians and Philippine Americans), who were

acknowledge^ less qualified under the School’s admission

standards than applicants of other races. That court con

cluded that this system of racial classification was justified

by the elimination of “ racial imbalance within public legal

education,” (507 P.2d at 1182), the production of “ a racial

ly balanced student body at the law school,” (id. at 1184),

and the alleviation of a nation-wide “ shortage of minority

attorneys,’ (ibid.).

_/

The position of the American Federation of Labor and

Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is that

this holding can not be squared with the Fourteenth

Amendment’s guarantees of due process and the equal pro

tection of the laws.

The AFL-CIO is a federation of 113 national and inter-'

national unions having a total membership of approxi

mately 13,500,000 working men and women. The Federa

tion’s interest in the question presented here is the product

of the following interrelated considerations:

First:

“ [T]he labor movement is the most integrated major

institution in American society, certainly more inte

grated than the corporations, the churches, or the uni

versities. * * * The percentage of blacks in the unions

is a good deal higher than the percentage of blacks in

the total population. # * * Moreover, blacks are joining

unions in increasing numbers. According to a 1968 re

port by Business Week, one out of every three new

union members is black.” Rustin, The Black And The

Unions, Harper’s Magazine, May, 1971, pp. 73, 76.

The major function of the trade union movement is to act'

ns its members’ exclusive bargaining represenlativc in

dealing with llieir employers on matters of “ wages, hours,,

and other tei'ms and conditions of employment.” See

§§8(a) (5), 8(d) & 9(a) of the National Labor Relations

Act, as amended, 29 U.S.C. §151 et seq. And as this Court

has recognized:

“ Inevitably differences arise in the maimer and degree

to which the terms of any negotiated agreement affect

individual employees and classes of employees. The1

mere existence of such differences does not make then

invalid. The complete satisfaction of all represented is

hardly to be expected. * * * Differences in wages, hours

and conditions of employment reflect countless varia

bles.” Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330, 338.

Thus, unions are front-line institutions dealing with and

attempting to harmonize, on a day-to-day basis, the inevi

table clashes of economic interest between individual em

ployees and between groups of employees (as well as those

between employees as a class and their employers).

Organized labor, therefore, well understands that there

is no escape from the necessity of rules of selection where

there are more applicants than there are openings, whether

the places to be filled are jobs, or positions in a professional

school (which serves as the method of entry to a particular

field of endeavor). And the union movement is fully cog

nizant that in our society, where employment is a major

, determinant of economic position, such rules are perhaps

the most important of all the norms governing the distri

bution of scarce resources. Precisely because this is so,

organized labor knows that if there is to be domestic tran

quility these rule's must be fair in fact and must be per-

l

eoived to bo fair by those whose fate they decide.

George Lichtheim has pointed o u t-“ Tf n

as a source of political antagonism'is rn ledm T * - the

resHlaal tensions • • • need not and doubtless wil] „ ol M

\VX1 'r” C M d * ‘ o'erab,

ZIZZTZZZ; n The N w Y o " k ^ *

™ st potent in a period, such as the present in w h ilh T

and rising nnemplovment spiralin. !„fl hlgh

sess ion , sudden shortensT ^

radical restrnetnring of establ s W , ! T * T * * * *

and an overall nno e * , ! d f and wo,'k Patterns,

‘- “ ’ M r

disequilibrium J" " P thG P0*0" 1''"1 for a violent

. , ^ r : r b°T 7 •

firmly eommitted to ! e*P°n ™«>. is- therefore,

hope ,„ r “ ul° , ~ io” ,h“ ‘ « » one best

‘ "ose rules of selection Z t ^ • * '

"artificial, arbitrarv ! a 7 m" S‘ ” ot constitute

ployment [that] opiate invffiousTy To T -" '" '" *°

the basis of racial ^ T y to discriminate on

and that they must n o t ° p r o ^ ^ ^ . Cl.a8,^ tioil,,»

erence for any group, minority or U o r “ JT, ̂

4

/

GnM N v- Vide rower Co., 401 U.8. 424, 431).

This commitment is not based on tlie fallacy^that there

: : ac,“ ' r c,i,ori“ * '» ^

appioacli the accuracy of the litmus test. Rather it is

from'' f'a a 'W°s,li,io" ,,w‘ retreat is beat

. fair and racialJy neutral employment * * * de

792° 801) ^ 411 u t

two’ t! ’ here -S ” ° equitable method of mediating be

tween the competing claims of minority workers, majority

workers, employers and the society at large.

. ®°CaUSe thG decision below rejects the proposition stated

a l t h o l f U McDonnell Douglas, its effects are pernicious,

although its intentions are the best.

Second, the AFL-CIO’s commitment to equal oppor

tumty as just defined has been manifested in two major

parallel courses of action. J *

T’ “ Rederat‘011 pressed for enactment of Title VII of

tLe CT R« hts A « of 1904 („,,d the strengthen!,,-1972

amendments), with the approving understanding that the

n,o„ movement would be strictly regulated thereby It

as ice,; c only multi-racial organization to thus prefer

fidelity to the eradication of racial discrimination ahead

in the 80 r r r frc0d01" ,rom government dictation

has reclll'ed ** m t N " al ^ AS * * * * * R“sti“

. 7 ! ™ drive aoa‘nst discrimination was ex

a Fair °F th<i figh‘ made b ̂ tbe AFL-CIO to have

• section writtea illt0 tbe

Rohert Tf ? Act B° tb Presid^ t Kennedy and

Robert Kennedy were opposed to including an FEPd

>

V.A

\

6

' ̂ section because they thought it would kill the bill, but

George Meany pressed for it. He did so for a simple

reason. The AFL-CIO is a federation of affiliates

which retain a relatively high degree of autonomy.

The parent body can urge compliance with its policies,

but the decision to act is left up to the affiliates. Meany'

felt that the only way the AFL-CIO could deal ef

fectively with unions practicing discrimination would

be to demand compliance with the law of the land.

He testified before the House Judiciary Committee

that the labor movement was calling “ for legislation

for the correction of shortcomings in its own ranks.”

And the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act greatly

speeded the process of this correction.” Rustin, The

Blacks And The Unions, supra at p. 76.

In a complementary effort, the AFL-CIO has been a

major force in a far-ranging affirmative action program,

the Apprenticeship Outreach Movement, to assure that

minorities have meaningful access to the most highly

skilled and well paying technical jobs in industry. William

M. Ross, the Deputy Executive Director of the Recruitment

and Training Program Inc. of New York, in a speech to

the Annual Rocky Mountain Apprenticeship Conference in

Salt Lake City, delivered in November 1973, described the

essence of the Outreach approach as follows:

“ Above all else, the outreach approach is an advocacy

strategy which is designed to provide a wide variety of

tutorial and supportive services to minority workers

who are seeking entry in the apprenticeship training

programs and skilled jobs in the construction industry.

“ The outreach concept originated in 1964 when The

Workers Defense League established a program to re

cruit black and Spanish speaking youth for placement

i

in construction apprenticeship training programs in

New York City. This program was the outgrowth of

a series of violent demonstrations which occurcd at

several construction sites in the city during the summer

of 19G3. These demonstrations, which were part of an

attempt to halt all publicly financed construction in

New York until 25 percent of the jobs in this industry

were tilled by black and Spanish speaking workers,

resulted in hundreds of arrests and costly work stop

pages. The Harlem hospital project, which was shut

down for more than four months, cost the city of New

York more than $250,000 for overtime payments to

police alone. The total,cost of this shut down ran into

the millions.

“ Together with most of the other civil rights or

ganizations in the city, the W.D.L. became a member

of the Joint Committee on Equal Employment Oppor

tunity which was established to coordinate the various

demonstrations. Initially, these protest activities were

predicated on the belief that it would be relatively easy

to find enough qualified black and Spanish workers to

fill the job slots which were being demanded, if sufficient

legal and community pressure could be brought to bear

upon the unions and contractors to force them to open

their apprenticeship programs to non-whites. However,

it soon became increasingly obvious that a special effort

was required to seek out qualified applicants who would

commit themselves to a career in the building trades.

“ With a-small grant from the Taconic Foundation,

The Workers Defense League rented a storefront in the

heart of the Bedford-Stuyvesant ghetto in Brooklyn and

established a program to (1) disseminate information

on construction employment opportunities; (2) to recruit,

counsel, and tutor black and Spanish speaking appren

ticeship applicants and (3) to provide follow-up sup-

i

portive services to the non-white apprentices who were

accepted into the unions’ training programs.

“ Within our first two years, we had placed more than

500 black and Spanish speaking youths in apprenticeship

programs.

“ Because of our success in New York and the failure

of other approaches in various cities around the coun

try, our outreach concept was adopted as a formal

program within the Manpower Administration of the

U.S. Department of Labor in 1967. Subsequently, our

approach became the model for several other local

organizations throughout the nation.

“ Since 1967, the apprenticeship outreach movement has

grown by leaps and bounds. At the present time, there

are 120 federally funded outreach programs in 227 dif

ferent cities. Of this total

. . . 37 are operated by the Urban League’s leap

program

. . . 26 are operated by R-T-P

. . . 17 are operated by local building and construction

trade councils

. . . 15 are operated by the AFL-CIO Human Re

sources Development Institute

. . . 24 are operated by other miscellaneous local

organizations such as the Trade Union Lcadci ship

Council in Detroit and Philadelphia; The New Jersey

Department of Labor and Industry; The Mexicain-

American Opportunities Foundation in Los Angeles;

The Opportunities Industrialization Center in Pitts

burgh, etc.

“ Because of the apprenticeship outreach movement,

there has been a dramatic and significant increase in

8

0

the number a ml percent ago of minority youth in con

struction apprenticeship programs. For example:

In 1960, there were less than 2,000 non-white

apprentices in the entire united states, and as late as

1906 non-white apprentices represented only two per

cent of all registered construction apprentices.

“ But between the time the outreach program was

first funded in 1967 and July of this year more than

26,000 non-white youths have been indentured in regis

tered apprenticeship programs in construction.

274 Asbestos Workers

1223 Bricklayers

5372 Carpenters

1126 Cement Masons

2896 Electricians •

466 Elevator Constructors k

251 Glaziers

1411 Iron Workers ; -

287 Lathers

1603 Operating Engineers y

1909 Painters

354 Plasterers .

.1031 Roofers

1289 Sheet Metal

145 Tile Setters

2410 Pipe Trades

“ At the present time non-white youths comprise ap

proximately fifteen percent of all registered construc

tion apprentices.”

Both Title VII and the Outreach program are faithful

to the premise that the rules of selection for employment

must, in this Court’s words in Griggs, make “ j6b

qualifications the controlling factor, so that race, religion,

10

nationality and sex become irrelevant” (401 U.S. at 436),

Indeed, perhaps the most significant fact about Outreach

is that it puts the lie to the counsel of despair and con

descension that racial preferences, such as that instituted

by the University of Wasliingon Law School, are nec

essary because minorities can not compete on the basis

of qualifications. As Mr. Ross noted in another passage

o f the same speech:

“ Our experience convinced us that fairly administered

tests and other qualifications which are relevant to job

requirements are not in surmountable obstacles to the

entry of minorities into apprenticeship. Indeed, we are

very proud of the tutoring techniques we have developed

to overcome the testing problem. In fact, we have now-

reached the point where in some cities our applicants:

are achieving higher test scores than all other appli

cants, white or black. For example, 73 percent of our

applicants scored ‘ high’ on a recent test which was given

by the Steamfitters Joint Apprenticeship Committee in

Now York. We have now reached the point where our

applicants are better at taking tests than the average

applicants.”

The answer, in other words, is not to abandon our com

mitment to the allocation of employment opportunities on

the basis of merit, a course that would be inconsistent with

the urgent need to maximize productivity and efficiency to

meet the critical economic problem we now face, but to

refine our measures of merit and to provide those who

have not received a sufficient grounding in . basic skills

the compensatory tutoring necessary to enable them to

compete on the basis of qualifications.

It is, we suppose, possible, in theory, that a system of

I I

equal opportunity embracing tlie principles slates iii

Griggs and McDonnell Douglas could survive affirmance

of the holding below. But it is not even remotely likely

that this would be the consequence. -The pressure, by a

significant number of policy makers, for sweeping, short

term, solutions to the agonizing economic problems of the

minority communities, without regard to the unfairness

of such solutions to those like Mr. De Funis, who have

both legitimate aspirations and substantial problems of /

their own, is too intense. In this area, as in others in our

political life, the overriding recent trend has been to ignore

the long-term costs of utilizing questionable means to

achieve the end sought.

Yet those long-term costs promise to be immense. In

an address to the AFL-CIO’s Eighth Constitutional Con

vention, some five years ago, Mr. Rustin pointed out the

factor that these planners overlook—it is that this country

faces a racial problem consisting of “ two elements—black

rage and white fear [that] feed on each other and set

this nation on a collision course.” (Proceedings of the

AFL-CIO’s Eighth Constitutional Convention, pp. 105-106)

Obviously neither this rag'e nor this fear can be pandered

to insofar as it is irrational. The program the labor move

ment has evolved does not do so. But the white fears en

gendered by racial preferences are not irrational. And

such preferences, while they may give the appearance of

answering “ black [or more broadly minority] rage,” do

not do so in a meaningful sense. As Mr. Rustin noted:

“ We don’t want special categories labeled ‘ Negro

carpenters’ >or ‘ Negro plumbers’ who have lower skills

and get less pay. We want Negroes.who are carpenters

l '

12

and plumbers—with the same skills and training and

wages that everyone else. has. We want the same pride

in our trade that any worker with dignity wants. And

We will not settle for less.” Id at 111.

That result can only be achieved by affording equal em

ployment opportunities as we have defined that concept.

It will not he achieved by a program of racial preferences.

It is because of the foregoing considerations that the

AFL-CIO has sought this opportunity to present its views

concerning this case to the Court.

ARGUMENT

The profound central lesson of the Fourteenth Amend

ment for this case, is, in the words of the brief amicus of

the Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’ritli in- support of

the jurisdictional statement (at pp. 11, 12, 16), that the:

“ Constitutionality [of racial classifications! turns on

whether [they! work any deprivation, and even if not,

on whether they are justified by a compelling interest,

' by ‘ some overriding statutory purpose,’ McLaughlin

' v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192 (1964). ‘ Without such

justification the racial classification . . . is reduced to

an invidious discrimination forbidden by the Equal

Protection Clause.’ McLaughlin v. Florida, supra,

‘ 379 U.S. at 192-93.

# # # #

“ [A! compelling state interest sufficient to justify a

racial classification can he shown only if the classifica

tion is undertaken in the course of administering a

remedy for proven prior discrimination, * * * [so that

the] remedy has followed with precision a wrong shown

with precision in a record # * *, or at least if, while

serving an allowable state purpose, it imposes no depri

vation on anyone.”

That statement of the law is drawn from, and meticulously

documented to, this Court’s decisions. To avoid needless

repetition we therefore incorporate the discussion of those

precedents in that brief by reference, take the conclusion

reached as a given, and devote ourselves herein to enlarg

ing upon and refining the basic proposition quoted above.

1. In allocating the 145 to 150 openings in the first-year

class, the University of Washington Law School applied

its test of qualification, expressed in essence in a weighted

formula, the “ predicted first year average,” so that black

Americans, Chicano Americans, native American Indians

or Philippine Americans (but not Asian Americans) were

treated separately from, and more favorably than, appli

cants of other races. The qualifications of these “ minority”

applicants wore compared only with others in that group,

and not against the entire universe of applicants.

The result was that “ minority” applicants were accepted

who would have been summarily rejected but for their mem

bership in that class. Juris. Stat. App. C. Finding XXIII.

In all, 44 minority applicants .were accepted, 38 of whom

had qualifications lower than Mr. Do Funis, the plaintiff-

appellant here, who is white, and who was not accepted.

Thus, “ the admissions of the less qualified [minority] stu

dents resulted in a denial of places to those better qualified

[of other races].” Juris. Stat. App. C. Finding XXIV.

There can be no dispute, then, that the Law School uti

lized a racial classification in determining who should be

accepted for its first year ftlass. And it is equally clear that

13

(■

14

tliis deprived Mi-. T)e Funis, and others similarly situated,

of a right to compote for placement in the Law School under-

some system of selection that does not discriminate against

them on the grounds of race.

2. There is no showing here that this racial classification

and preference for minority students is justified as a rem

edy, either for present discrimination, or for the present

effects of past discrimination.

(a) The record is barren of evidence that the Law School

was motivated by an intent to discriminate against minority

applicants. And there is no evidence that the School’s pres

ent rules of selection have discriminatory consequences for

minority applicants. Those rules as applied equally to all

had produced a student body with a racial mix approxi

mately that of the state (B ’nai B ’rith Juris. Stat. Brief,

p. 14), and were based on criteria that reliably predicted

'law school performance of both “ minority” and majority

students.

In a carefully considered and comprehensive decision,

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Comm., — F.2d —, 6 FEP

Oases 1045 (C.A.2, Nov. 21, 1973), Judge Friendly has re

viewed the standards for judging the legality of testing

procedures challenged as discriminatory:

“ In Castro v. Beecher, supra, 459 F.2d at 732, the First

Circuit stated that

‘The public employer must, we think, in order to justify

the use of a means of selection shown to have a racially

disproportionate impact, demonstrate that the means

is in fact substantially related to job performance.’

Judge Coffin later referred to the defendants’ obli-

\

15

gation to ‘ come forward with convincing facts estab

lishing a fit between the qualification and the job.’ Td.

* * * [A] showing of a racially disproportionate impact

puts on the municipal or state defendants not simply

a burden of going forward but a burden of persuasion.

* * * But if the public employer succeeds in convincing

the court that the examination was “ substantially re

lated to job performance,” an injunction should not

issue simply because he has not proved this to the hilt.

* * * “ Cases like this one have led the courts deep into

the jargon of psychological testing. Plaintiffs insist

that the only satisfactory examinations are those which

have been subjected to ‘ predictive validation’ or ‘ con

current validation,’ preferably the former. The district

court defined these terms as follows: ‘ Predictive vali

dation consists of a comparison between the examina

tion scores and the subsequent job performance of those

applicants who are hired’ ; ‘ Concurrent validation re

quires the administration of the examination to a group

of current employees and a comparison between their

relative scores and relative performance on the job.’

The judge wisely declined to insist on either. The Four

teenth Amendment no more enacted a particular theory

of psychological testing than it did Mr. Herbert

Spencer’s Social Statics. Experience teaches that the

preferred method of today may be the rejected one of

tomorrow. What is required is simply that an examina

tion must be ‘ shown to bear a demonstrable relation

ship to successful performance of the jobs for which

it was used.’ Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424,

431; McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792,

802 n.14. To be sure, an impressive showing of pre

dictive validation may end the inquiry then and there,

and one of concurrent validation may come close to

•doing so; thus these methods may well be preferable

in that sense. But these two schemes have their own

16

difficulties, and the failure to use one of them is not

fatal, at least from a constitutional standpoint, as long

as the examination is properly job-related.” Vulcan

Society, 6 FEP Cases at pp. 1049, 1050, footnotes

omitted.

In the instant case even the threshold showing—“ racially

.disproportionate impact” —necessary to require justifica

tion of the Law School’s qualifications criteria has not

been met. And, in any event, the “ demonstrable relationship

to successful [school] performance,” which must be proved

on that showing, is, as we understand the record, universally

acknowledged. *

(b) We hasten to add that none of this is -to say that

the present criteria are the only lawful ones, or, indeed,

that Mr. De Funis or any one else has a Fourteenth Amend

ment right to insist on these or similar rules of selection.

The law is a field as broad as human experience itself.

The range of permissible performance-related admission,

criteria is correspondingly broad. The Law School retains

the primary responsibility for the development of sensitive

and accurate measures of qualification attuned to its edu

cational mission as the School defines that mission. In

Judge Friendly Trenchant paraphrase: “ The Fourteenth

Amendment no more enacted a particular theory of psy

chological testing than it did Mr. Herbert Spencer’s Social

Statics.” Vulcan Society, 6 FEP Cases at 1050. But that

Amendment did enact a ban on rules of selection based on

racial classifications. •' ,

. I

(c) Even proof of past discrimination against minority

applicants would not validate the racial classification here

17

l

H

i

which works a deprivation of the constitutional rights of

the majority applicants.

Initially, it is difficult, at best, to give content to the

concept of past discrimination by the Law School against

• the minority applicants who are the beneficiaries of this

preference. A number of attempts, by a single individual,

over a period of years, to gain admission to a law school

is the rare exception. Almost without exception to speak

o f past discrimination in this context, as the court below

recognized, is to speak of overall societal failures or

failures at a lower rung in the educational ladder.

The policy of “ remedying” such discrimination by sub

stituting racial criteria for criteria “ shown to bear a

4 demonstrable relationship to successful performance”

(Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431) suffers from

four fatal flaws:

First, “ the indiyidual [majority applicant who is not

admitted] may have had no part in discrimination against

4 blacks; to impose on him the costs of remedying societal

discrimination seems unjust. It is all the more unjust since

the burden would fall most heavily on, whites who are

themselves relatively deprived.” Developments In The Law

—Employment Discrimination And Title VII Of The Civil

Rights Act of 19C4', 84 Harv. L. Eev. 1109, 1116. To weight

economic competition in this fashion against those who

can not be said to have meaningfully participated in a ,

wrong is impermissibly close to imposing punishment on the

ground of “ collective guilt,” in effect creating “ attaints

of the blood” for all members o f non-minority groups.

Second, such racial classifications:

“ have serious countereducative effects. Gordon Allport

i ' ■ /

i -

has defined ethnic prejudice as ‘ an antipathy based

upon a faulty and inflexible generalization.’ A crucial

objective of any antidiscrimination [program] must,

then, be education; it must break down faulty racial

stereotypes. Preferences, however, have the reverse

effect. * * * white [applicants], resentful of being

turned down * * * due to minority quotas, will only

have their stereotypes reinforced by a government that

proclaims blacks and other minorities to be in need of

special advantages.” Ibid; footnotes omitted.

Both of these factors, as we have pointed out (at pp.

supra) tend to create and maintain legitimate white fears,

thereby increasing social tensions and exacerbating the

, overall racial dilemma.

Third, the paternalistic grant of “ benign” preferences

serves to demean the recipient in his own eyes. The rein

forcement of invidious stereotypes just noted is not confined

to the majority applicants who are discriminated against.

See McPherson, The Blade Law Student: A Problem of

Fidelities, Atlantic Magazine, April 1970, p. 88; Gfraglia,

Special Admission Of The “ Culturally Deprived” To Law

School, 119 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 351, 353-359. By the same

token this device tends to deprive minority applicants, who

have in fact qualified on merit, of the full recognition for

their achievement they richly deserve. See p. supra.

Fourth, it is a delusion to believe that the overall inter

ests of society are advanced by diluting the reliance on

qualification and relying on race in selecting those who

• will fill a limited number of positions (either in a profes

sional school class or a job market). To the extent that well

paying positions are plentiful and there is an economy of

' 18

10

abundance, modifying rules of selection in this manner

may be of relatively little moment except to tliose directly

and adversely affected. Hut neither of those conditions

obtain. These are not times that allow the prodigal waste -

of scarce resources, the most valuable of which is “ efficient

and trustworthy workmanship assured through fair and

racially neutral employment and personnel decisions,”

(McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801),

responsive to the expectation that achievement brings re

wards. Thus:

, i

“ Many economists have suggested that in increasing

: equality, productivity should not be sacrificed. Instead, ]

output should be maximized and changes made in the

way tliat output is distributed. Such an approach is

a more refined and efficient means of giving aid, since ,

the beneficiaries can be identified more precisely and ,

the true costs of the process can be computed with

greater precision.” Developments— Title VII, 84 Harv.

L. Rev. at 1115.

The sum of the matter is that this racial classification is

“ an invidious discrimination forbidden by the Equal Pro

tection Clause” (McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 193), ■>

because the guarantee of the “ equal protection of the law

can not be squared with a system that deprives members

of one race of their rights in order to provide “ recom

pense” tp members of another.

This conclusion accords with that reached by Congress.

Cf. Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641. The problem here

is in all essential respects that treated in Title VII, where

Congress banned all employment discrimination against,

minority groups, (§§703(a)-(d)) as well as preferences for

20

them (§703( j )) and affirmed the lawfulness of job-related

qualifications. (§703(h)). As this Court stated in Griggs

40b U.S. at 430-431 (footnote omitted):

The Court of Appeals’ opinion, and the partial dissent,

agreed that, on the record in the present case, “ whites

register far bettor on the Company’s alternative re

quirements’ ’ than Negroes. 420 F. 2d 1225,' 1239 n. 6.

This consequence would appear to bo directly traceable

to race. Basic intelligence must have the means of

articulation to manifest itself fairly in a testing

process. Because they are Negroes, petitioners have

long received inferior education in segregated schools

and this Court expressly recognized these differences

in Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969). There, because of the inferior education re

ceived by Negroes in North Carolina, this Court barred

the institution of a literacy test for voter registration

on the ground that the test would abridge the right to

vote indirectly on account of race. Congress did not

intend by Title VII, however, to guarantee a job to

every person regardless of qualifications. In short, the.

Act does not command that any person be hired simply

because he was formerly the subject of discrimination,

or because he is a member of a minority group. Dis

criminatory preference for any group, minority or

majority, is precisely and only what Congress has

proscribed. What is required by Congress is the re

moval of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers

to employment when the barriers operate invidiously

to discriminate on the basis of racial or other im

permissible classification’ ’

The critical difference between Gaston County, on the

one hand, and Griggs and the instant case, on the other,

is that in the former the method utilized to eradicate the

21

effects of past discrimination did not deprive any other

voter of his rights, while in the latter, to substitute selec

tion on the basis of race for selection on the basis of

qualification does impinge on the rights of those not

accorded the preference, because their opportunity to obtain

one of a limited number of places is correspondingly

diminished.

(d) The burden of the argument thus far has been that

racial classifications that result in a preference, in securing

' one of a limited number of openings, to less qualified

minority applicants over more qualified majority appli

cants, as measured by criteria “ shown to bear a demonstra

ble relationship to successful performance,” ( Griggs, 401

U.S. at 431), does not meet the.jequirements of the Consti

tution. There is a contrary line of authority in the lower

federal courts upon which the court below relied. The most

recent decision in that line is Associated General Con

tractors v. Altshuler, ------F. 2d------ , 6 FEP Cases 1031

(C.A.l, Nov. 30,1973).

In Altshuler, the court sustained the validity of a re

quirement, imposed by the Commonwealth of Massachu

setts, upon contractors engaged in publically funded con

struction, that the contractor must:

“ ‘ . . . maintain on his project, which is located in an

area in which there are high concentrations of minor

ity group persons, a not less than twenty percent ratio

of minority employee man hours to total employee man »

hours in each job category. . . . ’ ”

• ♦ # #

. “ The Secretary of Transportation and Construction

for the Commonwealth, who is charged with enforcing

22

[this] provision, interprets [it] to mean that [the

Commonwealth] requires the hiring of only ‘ qualified’

workers.”

Contractors who do not meet this ratio are subject to

sanctions unless at a hearing they demonstrate that they

have taken “ every possible measure to achieve compli

ance.” 6 FEP Cases at 1014.

The First Circuit recognized that:

“The Commonwealth’s affirmative action plan forces us

to address a fundamental question: are there consti

tutional limits to the means by which racial criteria

may be used to remedy tbe present effects of past dis

crimination and achieve equal opportunity in the fu

ture?” 6 FEP Cases at 1019.

The answer it proposed was that rules of selection may be

based on racial criteria so long as these do not require pref

erence to “ unqualified minority workers,” and so long, as

the employer is granted the opportunity to prove that the

only reason he did not meet his assigned “ goal” is that to

.do so he would have been required to hire “ unqualified mi

nority workers.'” 6 FEP Cases at 1019-1021. This was in

essence the approach of Contractors A ss’n. of Eastern Pa.

v. The Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (C.A.3) cert,

denied 404 U.S. 854, where the court relied upon the asser

tion that the goals and timetables for minority hiring there

set would not “ eliminat[e] job opportunities for white

tradesmen,” (422 F.2d at 173).

But neither the First Circuit nor the Third Circuit (or

the other of the lower courts that have embraced this posi

tion) have explained the justification for discriminating in

favor of less qualified minority workers and against, more

23

qualified majority workers. This is undoubtedly because no

justification exists. The harm to the majority worker who

is thereby unemployed is precisely the same. It is, in fact,

precisely the same as the harm visited upon a more qualified

minority worker who is rejected in favor of a less qualified

majority worker on racial grounds.

This Court has therefore emphasized that:

“ Congress has not commanded that the less qualified be

preferred over the better qualified simply because of

minority origins. Far from disparaging job qualifica

tions as such, Congress has made such qualifications

the controlling factor, so that race, religion, nationality,

and sex become irrelevant.” Griggs, 401 U.S. at 436. '

Thus, it is not constitutionally sufficient that the better >

qualified worker had an attenuated opportunity for a job

rather than having his job opportunities “ eliminated” . For

his right is to a system of selection embodying “ fair and

racially neutral employment and personnel decisions,”

( cf., McDonell Douglas, 411 U.S. at 801).

(e) The conclusion that the decision below, and kindred

decisions such as Altshuler, are wrongly decided does not

“ provide equality of opportunity merely in the sense of

the fabled offer of milk to the stork and the fox.” Griggs,

401 U.S. 431. The argument pressed here rests on the

premise that if a method of selection “ which operates to

exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be related to * * *

performance, [it] is prohibited.” Ibid. Moreover, organized

labor’s entire response to'the challenge of providing equal

employment opportunity is predicated upon the recogni

tion: first, that the range of affirmative actioji open to

enable minority Americans to meet performance related

\

/

24

rules of selection is, and should be, all but unlimited; and,

v second, that affirmative action, in this sense, does work.

See pp. supra. But we do insist that Government may

“ not command that any person be [preferred] simply

because he was formerly the subject of discrimination,

or because he is a member of a minority group,” and

that the Constitution does forbid “ discriminatory pref

erence for any group, minority or majority,” (cf. Griggs4

.401 U.S. at 431).

-----—'V..

25

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set out above, as well as those stated

by the appellants, and the other amici supporting their

position, the decision below should be reversed.

Ts . '

AT.

(A Hi

*

Respectfully submitted,

J. A lbert W oll i

General Counsel, AFL-CIO

R obert C. M ayer

L aurence Gold

* 736 Bowen Building

815 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20005

T homas E. H arris

Associate General Counsel,

AFL-CIO

815 Sixteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006