National Black Police Association v. Velde Supplemental Memorandum for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. National Black Police Association v. Velde Supplemental Memorandum for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1982. 3f8b4bfe-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d2540dee-ff9a-458f-9eb1-a7c4d9701994/national-black-police-association-v-velde-supplemental-memorandum-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

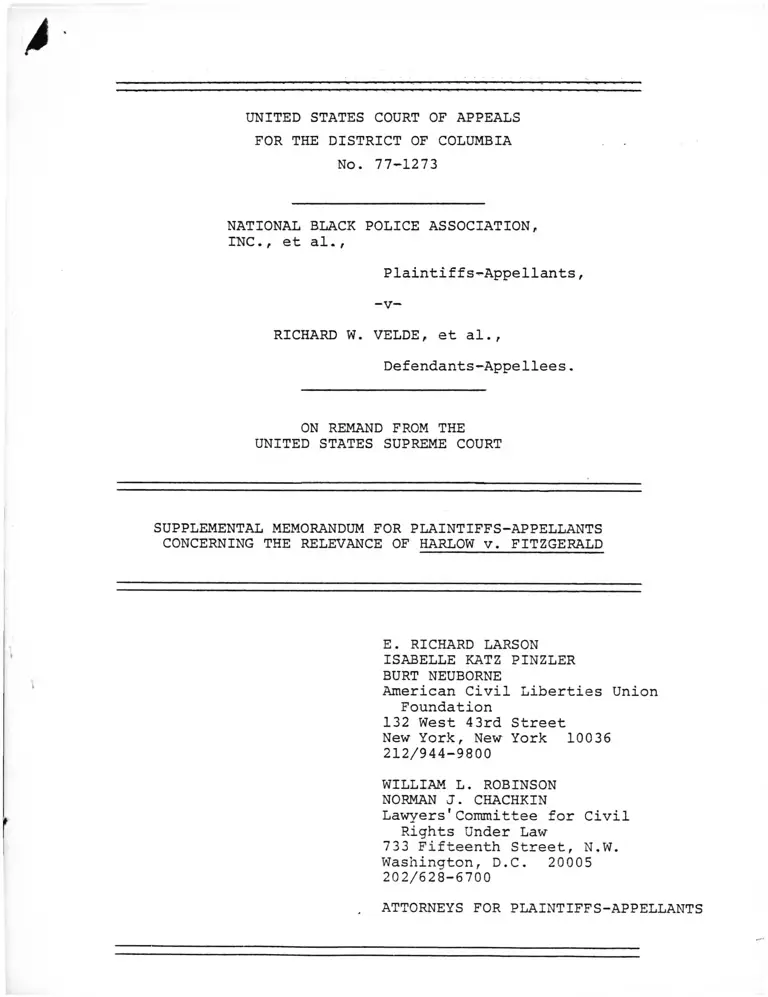

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

No. 77-1273

NATIONAL BLACK POLICE ASSOCIATION,

INC., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

-v-

RICHARD W. VELDE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON REMAND FROM THE

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORANDUM FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

CONCERNING THE RELEVANCE OF HARLOW v. FITZGERALD

E. RICHARD LARSON

ISABELLE KATZ PINZLER

BURT NEUBORNE

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

212/944-9800

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers'Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washinqton, D.C. 20005

202/628-6700

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................. 1

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS IN THIS C A S E ........................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................... 4

ARGUMENT .............................................. 7

I. Under Harlow and this Court's

Prior Ruling, Defendants Are

Not Entitled to Absolute Immunity ................ 7

II. Under Harlow and this Court's

Prior Ruling, Defendants as a

Matter of Law Are Not Entitled

to Qualified Immunity ............................ 10

III. Defendants' Qualified Immunity Claim

Is Due to be Rejected Under Harlow

and Other Relevant Decisions Even

if this Court's Prior Ruling Is Not

Accorded Controlling Significance ................ 13

A. In Determining What Constitutional

and Statutory Rights Were "Clearly

Established" at the Time of the

Defendants' Actions in this Case,

the Court Should Look to Supreme

Court Rulings, Its Own Decisions,

and Those of Other Federal Courts,

as well as to Statutory Enactments

and Legislative History ...................... 15

B. Clearly Established Constitutional

and Statutory Law Required Defendants

to Withdraw Federal Financial Aid

From Recipients Practicing Invidious

Discrimination at the Time of the Acts

Complained of in This C a s e .................. 19

C. Since Plaintiffs Alleged — and Both

the Record And Judicially Noticeable

Materials Conclusively Demonstrate —

That Defendants Deliberately Continued

to Provide Federal Funds to Grantees

Shown by Their Own Investigations to

Practice Invidious Discrimination,

Defendants Violated "Clearly Established

Statutory or Constitutional Rights of

Which a Reasonable Person Would Have

Known" and Are Not Entitled to Qualified

Immunity.................................... 25

CONCLUSION............................................ 33

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Case

*Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159

(D.C. Cir. 1973) ten banc) ...................... 22

Barr v. Matteo, 360 U.S. 564 C1959) .................. 7

*Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497C1954).............................................. 19

Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S. 507 C1980) ................ 16

Brown v. South Carolina State Bd. of

Educ. f 29 6 F. Supp. Ift9 tD.S.C.J,

aff1 d, 393 U.S. 222 CL9681 . . . " .................... 20

*Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478

(1978).......................................... 7, 8, 10

Calkins v. Blum, 511 F. Supp. 1073

(N.D.N.Y. 19 81) , af f' d on the basis

of the district court opinion,

675 F. 2d 44 (2d Cir. 1982) ........................... 18

Chavis v. Rowe, 643 F.2d 1281 (7th

Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 907(1981) . . . . . .................................. 18

Coffey v. State Educational Finance

Comm'n, 296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D.

Miss. 1969) 20

*Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............ 7, 20, 25

Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976) .................. 15

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976) 16

Flores v. Pierce, 617 F.2d 1386 (9th

Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 449 U.S.

875 (1981) . . . . . . ............................ 17

Fowler v. Cross, 635 F.2d 476 (5thCir. 1981).......................................... 15

Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411 U.S. 778 (.1973)

11

Page

15

Ill

Case Page

*Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d

731 (7th Cir. 1971).............................. 20, 22

Gilmore v. Montgomery, 417 U.S.

556 (.1974) 21

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565

(1975) 16

*Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp.

1150 (D.D.C-), aff'd sub nom.,

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971) 20

*Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp.

1127 (D.D.C.), appeal dismissed,

398 U.S. 956 (1970).................................. 20

Gullatte v. Potts, 654 F.2d 1007

(5th Cir. 1981)......................................... 16

*Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 50 U.S.L.W.

4815 (U.S. June 24, 1982)........................... passim

Hicks v. Weaver, 302 F. Supp.

619 (E.D. La. 1969).................................. 22

Hodecker v. Blum, 525 F. Supp.

867 (N.D.N.Y. 1981)..................................... 19

Imbler v. Pachtman, 424 U.S. 409

(1976) 10

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.,

267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.),

aff'd sub nom. , Wallace v. United

States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967).......................... 20

Mary and Crystal v. Ramsden, 635

F. 2d 590 (7th Cir. 1980) ........................... 16

McNamara v. Moody, 606 F.2d 621

(5th Cir. 1979)...................................... 15

Morrisey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471

(1972) 15

*NAACP Western Region v. Brennan,

360 F. Supp. 1006 (D.D.C. 1973)........................ 20

*National Black Police Ass'n v.

Velde, 631 F.2d 784 (D.C. Cir.

1980)...............................................passim

iv

Case Page

Nekolny v. Painter, 653 F.2d 1164

(,7th Cir. 1981)...................................... 15

*Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455

(.1973) .......................................... 20, 21

O'Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S.

563 Q.975) 10

Perez v. Rodriguez Bou, 575 F.2d

21 Cist Cir. 19 78) 16

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979).................................. 21

Poindexter v. Louisina Financial

Assistance Comm'n, 275 F. Supp.

833 CE.D. La. 1967), aff'd, 389

U.S. 571 (.1968) . . . . ............................... 20

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S.396 (1975) 15

Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S.

555 (1978) ...................................... 10, 14

Rogers v. Lodge, 50 U.S.L.W. 5041

(U.S. July 1, 1982).................................. 21

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232

(19 74) ............................................. 7, 10

Shannon v. HUD, 436 F.2d 809

(3d Cir. 1970) .................................. 22

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital, 323 F.2d 959 (4th Cir.

1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S.

938 (1964) . . . ..................................... 20

Visser v. Magnarelli, 542 F. Supp.

1331 (N.D.N.Y. 1982) 15

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976) 21

Washington v. Lee, 263 F. Supp.

327 (M.D. Ala. 1966), aff'd

per curiam, 390 U.S. 333 (1968)...................... 16

Washington v. Seattle School Dist.

No. 1, 50 U.S.L.W. 4998 (U.S.

June 30, 1982) 21

V

Williams v. Anderson, 562 F.2d

1081 (8th Cir. 1977).............................. 17, 18

*Williams v. Treen, 671 F.2d

892 (5th Cir. 1982) .......................... 16, 17, 18

Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S.

308 (1975).............................. 10, 14 , 31

Constitution and Statutes

U.S. Const., Amend. V .............................. passim

Crime Control Act of 1973, §

518(c), Pub. L. No. 93-83, § 2

87 Stat. 197, codified in 42

U.S.C. § 3766(c) (Supp. V 1975) passim

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, codified in 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d-l passim

Regulations

40 Fed. Reg. 56454 (December 3, 1975) ................ 31

41 Fed. Reg. 28478 (June 12, 1976).................... 31

Legislative History

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1155, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976) .................................. 27, 28

119 Cong. Rec. 20071 (June 18, 1973) ........ 24, 26, 28, 29

119 Cong. Rec. 22059 (June 28, 1973).................. 28

LEAA Hearings Before Subcommittee

No. 5 of the House Committee on

the Judiciary, 93d Cong., 1st

Sess. (1973)........................................ 27

LEAA Hearings Before the Subcommittee

on Crime of the House Committee on

the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1976)............................................ 22, 29

Case Page

vi

Page

Other Authorities

The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement

Effort — 1974, Vol. VI — To

Extend Federal Financial Assistance,

C1975)................................................. 26

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

On June 30, 1982, the Supreme Court vacated this Court's

prior judgment and remanded this case "for further consideration

in light of Harlow & Butterfield v. Fitzgerald, 11 50 U.S.L.W.

4815 (U.S. June 24, 1982). 50 U.S.L.W. 5033 lU.S. June 30, 1982),

vacating and remanding National Black Police Ass'n v. Velde,

631 F.2d 784 (D.C. Cir. 1980).

We submit that the Harlow decision confirms the correctness

of this Court's prior ruling that defendants-appellees are not

entitled to an absolute immunity. Harlow, together with this

Court's prior reading of the nondiscretionary obligations imposed

upon defendants-appellees by the Omnibus Crime Control Act, also

compels the conclusion that as a matter of law defendants-

appellees are not entitled to qualified immunity. Defendants

are entitled to no immunity, and this Court's prior judgment

remanding this case for trial on plaintiffs' constitutional and

statutory claims should be reinstated.

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS IN THIS CASE

This lawsuit was filed on September 4, 1975 by the National

Black Police Association, Inc. and by six blacks and six women

who alleged that their constitutional and statutory rights had

been violated by the federal defendants' unabated provision of

direct financial assistance to discriminatory state and local

law enforcement agencies, in violation of, inter alia, the Fifth

Amendment to the United States Constitution; Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d et seq.; and §

-2-

518Cc) and § 509 of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets

Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 3766 (.c) and § 3757. App. 1, 4-39.

Plaintiffs sought declaratory and injunctive relief as well as

damages for alleged willful and knowing violations of their

constitutional and statutory rights. Id.

Proceedings in the Trial Court

One week after the commencement of this litigation, plain

tiffs initiated discovery by serving interrogatories, requests

for admissions, and requests for production of documents. App.

1-2, 289-96. Defendants did not respond to this discovery and

on December 22, 1975 the trial court ordered a stay of all

discovery. Id. Plaintiffs' motion to vacate the stay, id.,

was never ruled on by the trial court.

In January, 1976, plaintiffs filed a motion for a prelim

inary injunction. App. 2, 40-185, 481-623. The motion was

never ruled on by the trial court.

On February 9, 1976, more than five months after the

commencement of this action, defendants moved to dismiss or

for summary judgment. App. 2, 186-245, 624-720. Plaintiffs

opposed this motion. App. 2, 246-477, 481-623, 721-846. Five

months later, defendants filed another motion to dismiss, App.

2, 478, and plaintiffs again opposed. App. 3.

1. The_citations to "App." in this brief are to the three-

volume appendix filed with this Court on plaintiffs' original appeal.

2• Defendants nonetheless immediately provided part of

the relief sought by plaintiffs. See infra pp. 30-31 note 31.

-3-

The trial court, on December 8, 1976, dismissed this

action. App. 3, 479-80. The court held that plaintiffs' claims

for declaratory and injunctive relief had "been rendered moot

by virtue of the enactment of the Crime Control Act of 1976."

Id. The court also held that plaintiffs' damage claims against

the defendant federal officials for their willful and knowing

violation of plaintiffs' constitutional and statutory rights

were "barred by the doctrine of official immunity." Id.

Proceedings in this Court

The trial court's dismissal of this action was reversed

by this Court in National Black Police Ass'n v. Velde, 631 F.2d

784 (D.C. Cir. 1980). As to plaintiffs' claims for declaratory

and injunctive relief, the Court held that the "1976 amendments

did not render any of [plaintiffs'] claims moot and, on remand,

[plaintiffs] will be entitled to proceed on all causes of action

stated in this complaint." Id. at 786 (footnote omitted). As

to plaintiffs' claims for monetary damages, this Court held that

defendants' stringently defined statutory and constitutional

duties deprived them of discretion and thus defeated their claim

that they were "protected by absolute immunity." Id. at 787.

The court concluded, id. (.footnote omitted);

Accordingly, we find that [defendants] have only

a defense of qualified immunity and reverse the

district court's dismissal of the claims for

monetary damages. [Plaintiffs] should be

allowed to go to trial on their claims for

damages and [defendants] given a chance to es

tablish a defense of good faith or reasonable

grounds for their conduct.

Proceedings in the Supreme Court

Defendants did not seek review in the Supreme Court of the

-4-

ruling on mootness. Instead, in their petition for certiorari

filed December 29, 1980, see 49 U.S.L.W. 3496 (Jan. 13, 1981),

defendants presented three questions, all pertaining to plain

tiffs' claims for monetary damages:

(1) Are federal officials absolutely immune

from personal damages liability for their

decision not to initiate administrative

action to terminate federal funding to local

government agencies that allegedly engage in

discriminatory personnel practices?

(.2) Does [defendants'] failure to terminate

federal funding to local government agencies

that allegedly discriminate on the basis of

race and gender give rise to a cause of action

for damages under the Fifth Amendment?

(3) Are [defendants] entitled to qualified

immunity as a matter of law?

See 49 U.S.L.W. 3584 (Feb. 17, 1981). The Supreme Court granted

certiorari, 49 U.S.L.W. 3824 (U.S. May 4, 1981).

After plenary review, the Supreme Court vacated this Court's

prior judgment and remanded the case "for further consideration

in light of Harlow & Butterfield v. Fitzgerald," 50 U.S.L.W.

4815 (U.S. June 24, 1982). 50 U.S.L.W. 5033 (U.S. June 30, 1982).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In view of the Supreme Court's limited remand "for further

consideration in light of Harlow & Butterfield v. Fitzgerald,"

the only issues now before this Court are the alleged avail

ability of absolute immunity and qualified immunity defenses

-5-

to plaintiffs' damage claims.—^

Defendants' absolute immunity defense, premised on their

alleged prosecutorial discretion, was previously rejected by

this Court on the ground that the Omnibus Crime Control Act

allowed defendants "virtually no discretion." 631 F.2d at 787.

Harlow confirms the correctness of this ruling.

Defendants' argument that they are entitled to a qualified

immunity defense as a matter of law was not previously decided

by this Court. Under Harlow, not only must defendants' argument

be rejected, but defendants now must be denied qualified immunity

as a matter of law. Harlow adopts an objective test for qualified

immunity, under which federal officials "performing discretionary

functions" may be held immune from liability so long as their

conduct did "not violate established statutory or constitutional

rights of which a reasonable person would have known." 50 U.S.L.W.

at 4820 (emphasis added). Because this Court has already deter

mined that the Crime Control Act allowed defendants "virtually

3. This Court's prior ruling that plaintiffs' claims

for declaratory and injunctive relief were not mooted by the

1976 amendments to the Crime Control Act, see 631 F.2d at 786,

is not before the Court on this remand. Defendants did not

seek review of this ruling in the Supreme Court, and Harlow

did not decide or discuss any mootness issues. Of course,

any factual developments subsequent to this Court's prior ruling

which may bear upon the continuing need for injunctive relief

may be considered by the district court on the remand which we ask this Court to order.

This Court's prior ruling recognizing plaintiffs' standing,

see 631 F.2d at 787 n.16, compare id. at 788-91 (concurrence in

part as to standing), similarly is not before this Court on

remand. Not only did defendants fail to seek Supreme Court

review of this ruling; but standing is a jurisdictional issue

and the Supreme Court's remand left this Court's ruling on the

question undisturbed. Harlow, of course, did not deal with any standing issue.

-6-

no discretion," 631 F.2d at 787, defendants do not meet the

threshold legal requirement announced in Harlow for an official

immunity claim: the performance of discretionary functions.

Moreover, this Court's prior reading of the statute also

established as a matter of law that defendants, under the

objective test of Harlow, must "reasonably have known" that

their refusal to commence fund termination proceedings against

grant recipients practicing invidious discrimination violated

clearly established statutory rights.

Even putting to one side this Court's prior interpretation

of the Crime Control Act, Harlow compels rejection of defendants'

qualified immunity defense as a matter of law because defendants

here did violate both clearly established constitutional law

and their own equally clear statutory obligations. Contrary to

the established equal protection maxim that government cannot

support discrimination through any arrangement, management,

funds, or property, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19 (1958),

defendants here provided unabated direct financial assistance

to grantees whom they knew to practice invidious discrimination.

And, contrary to the nondiscretionary mandate of § 518Cc)(2)

of the Crime Control Act of 1973 — requiring the termination

of funding to discriminatory grantees — defendants here refused

to initiate fund termination proceedings even when their own

investigations revealed that grantees were continuing to prac

tice discrimination. Thus, under Harlow's objective test, the

defense of qualified immunity must be rejected as a matter of law.

-7-

ARGUMENT

I

Under Harlow and this Court's

Prior Ruling, Defendants Are

Not Entitled to Absolute Immunity

The Supreme Court's decision in Harlow confirms the correct

ness of this Court's prior denial of absolute immunity to defen

dants. This conclusion is apparent from the absolute immunity

defenses periodically asserted in this case by defendants, from

this Court's prior ruling on absolute immunity, and from the

Harlow decision itself.

In the course of this litigation, defendants have advanced

several different theories as to why they should be clothed

with an absolute immunity from damages liability. Initially —

despite the Supreme Court's decisions in Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416

U.S. 232 (1974), and its progeny — defendants alleged that they

were administrative officials who had acted within the outer

perimeter of their official duties and thus had absolute immunity

as federal administrative officials under Barr v. Matteo, 360

U.S. 564 (1959). Although the trial court agreed and dismissed

plaintiffs' damage claims on this basis, App. 479-80, defendants

thereafter — while this case was pending on plaintiffs' appeal

to this Court — quickly abandoned this theory following the

Supreme Court's ruling in Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478 (1978).

After Butz, defendants no longer asserted that they were

immune as administrative officials. Instead, defendants sought

to bring themselves within a limited exception to the "no

absolute immunity" rule of Butz by now describing themselves

-8-

as "prosecutors."— Disregarding both the narrowness of the

exception authorized in Butz, see supra note 4, and also

disregarding the nondiscretionary duties imposed on them by §

518(c)(2) of the Grime Control Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3766(c)(2)

CSupp. V 1975), defendants claimed that they — and thus nearly

all federal agency officials — were now "prosecutors" protected

by an absolute immunity.

In its 1980 ruling, this Court squarely rejected the abso

lute immunity defense because of the fundamental flaw in defen

dants' prosecutorial immunity theory: the fact that defendants,

under both their governing statute and the federal Constitution,

lacked the traditional broad discretion of "prosecutors" upon

which the Butz exception turned.

The purpose of shielding discretionary

prosecutorial decisions from fears of

civil liability has no place where, as

here, agency officials lack discretion.

[Defendants] have virtually no discretion

4/

4. Although Butz rejected the defense of absolute immunity

for federal program administrators, the Supreme Court did allow

an absolute immunity defense for three of the defendants in

that case: the agency's prosecuting attorney who was responsible

for presenting the government's case at the administrative

hearing, the Chief Hearing Examiner who was responsible for

hearing and deciding the case, and the Judicial Officer who was

responsible for reviewing the ruling of the Chief Hearing Examiner.

438 U.S. at 508-18. The Butz Court also indicated that agency

officials who "have broad discretion in deciding whether a pro

ceeding should be brought and what sanctions should be sought"

may also be entitled to an absolute immunity. 438 U.S. at 515.

Aside from the fact that on this record, no defendant has

admitted responsibility for the absolute refusal ever to initiate

administrative fund termination proceedings against discrimina

tory grantees, the dispositive factor defeating defendants'

absolute immunity claim is that, as this Court previously held,

defendants' governing statute deprived them of any discretion --

much less broad discretion — to decide whether a fund termina

tion proceeding should be brought. See 631 F.2d at 787.

-9-

under the relevant statute in deciding

whether to terminate LEAA funding of

discriminatory recipients.

* * *

The mandatory language of 42 U.S.C. §

3766 (c) (.2) CSupp. V 1975) (amended 1976),

when read in light of [defendants']

constitutional and independent statutory

duty not to allow federal funds to be used

in a discriminatory manner by recipients,

takes [defendants'] civil rights enforce

ment duties outside the realm of discretion.

631 F.2d at 787 & n.15 (citation omitted).

The Supreme Court's Harlow decision in no way calls into

question the correctness of this Court's earlier ruling. Harlow

and Butterfield sought absolute immunity not because of alleged

prosecutorial discretion, but on three other grounds: as an

incident of their offices as Presidential aides, as derivative

of Presidential immunity, and as protection for the special

functions of White House aides entrusted with discretionary-

authority in such sensitive areas as national security and

foreign policy. 50 U.S.L.W. at 4817-19. Based upon Butz, the

Harlow Court rejected the first two grounds outright. 50 U.S.L.W.

at 4817-18. Based again upon Butz and upon the record, the

Harlow Court also rejected the special function basis for abso

lute immunity since neither official had shown "that the respon

sibilities of his office embraced a function so sensitive as to

require a total shield from liability," nor "that he was dis

charging the protected function when performing the act for which

liability is asserted." 50 U.S.L.W. at 4819 (footnote omitted).

Defendants here have never asserted, much less sought to

justify, an absolute immunity defense based on alleged special

functions with discretionary responsibilities for national

-10-

security or foreign policy. On this record, and particularly

in view of Butz and Harlow, no such claim could be made. As to

defendants' assertion of prosecutorial discretion to support

a defense of absolute immunity, nothing in Harlow disturbs the

correctness of this Court's prior ruling that defendants lack

such discretion and that defendants are not entitled to absolute

immunity. For this reason, the absolute immunity claim must

be rejected today as it was two and a half years ago.

II

Under Harlow and this Court's

Prior Ruling, Defendants as a

Matter of Law Are Not Entitled

_____to Qualified Immunity____

Throughout the original appeal proceedings in this case,

defendants argued that they were entitled as a matter of law

to a qualified immunity defense.—^ Since the trial court had

6 /not ruled on the qualified immunity claim,— this Court in its

1980 ruling held that plaintiffs "should be allowed to go to

5. See Brief for Appellees, National Black Police Ass'n

v. Velde, 631 F.2d 784 (,D.C. Cir. 1980) , at 51-5 3; Supplemental

Brief for Appellees, id., at 20; Petition for Rehearing and

Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, id., at 11-14.

6. As explained supra p . 2 , there had been no trial in

this case, and all discovery sought by plaintiffs had been

denied. This lack of an opportunity for factual development of

the motivations for defendants' actions was very significant

under the law of qualified immunity prior to the Harlow decision.

See Butz v. Economou, 438 U.S. 478, 497-98 (1978), quoting from

Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232, 247-48 (1974); id. at 498,

quoting from Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 322 (1975); see

also Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. 555, 562 (1978), and

O'Connor v. Donaldson, 422 U.S. 563, 577 (1975), both cited with

approval in Butz, 438 U.S. at 498; Imbler v. Patchtman, 424 U.S.

409, 419 n.13 (1976).

-11-

trial on their claims for damages and [defendants] given a

chance to establish a defense of good faith or reasonable

grounds for their conduct." 631 F.2d at 787 (footnote omitted).

Under Harlow, not only are plaintiffs still entitled to go to

trial, but defendants' assertion of qualified immunity must now

be denied as a matter of law.

1. The Supreme Court in Harlow recognized that qualified

"[i]mmunity generally is available only to officials performing

discretionary functions," 50 U.S.L.W. at 4820, and the Court

formulated the objective test which it announced in Harlow

explicitly for only those officials performing discretionary

functions:

We therefore hold that government officials

performing discretionary functions generally

are shielded from liability for civil damages

insofar as their conduct does not violate

clearly established statutory or constitu

tional rights of which a reasonable person

would have known.

Id. (emphasis added). Because defendants did not meet the thresh

old Harlow requirement of exercising discretionary functions, as

a matter of law they are not entitled to the qualified immunity

defense.

As this Court previously recognized in interpreting defen

dants' duties under § 518(c)(2) of the Crime Control Act, 42

U.S.C. § 3766 (c) (2) (Supp. V 1975), defendants "have virtually

no discretion under the relevant statute in deciding whether

to terminate LEAA funding to discriminatory recipients." 631

F.2d at 787. In fact, the "mandatory language" of the statute,

when read in conjunction with defendants' "constitutional . . .

duty not to allow federal funds.to be used in a discriminatory

-12-

manner by recipients, takes [defendants'] civil rights enforce

ment duties outside the realm of discretion." Id. at 787 n.15

(citation omitted). This absence of discretion in turn takes

defendants outside of the realm of qualified immunity under

Harlow.

2. This Court's prior reading of defendants' obligations

under the Constitution and the Crime Control Act compels rejec

tion of the qualified immunity defense for yet another reason.

At the time of this Court's prior decision, qualified immunity

for officials performing discretionary functions rested upon

both an "objective" test and a "subjective" test. Official

immunity was available only upon a showing (a) that governmental

officers acted "in good faith," with the subjective belief that

their actions were lawful, and (b) that there were objectively

reasonable grounds for that belief. See cases cited supra p. 10

note 6. Harlow eliminates the burden upon those claiming the

defense to establish their subjective good-faith motivation.

50 U.S.L.W. at 4819-20. Harlow teaches that officials "performing

discretionary functions" may establish entitlement to qualified

immunity by showing that their conduct did not "violate established

statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person

would have known." Id. at 4820.

In this case, in which all of the defendant officials are

lawyers, this Court's prior determination that defendants'

governing statute on its face vested them with no discretion

to fail to commence fund termination proceedings against dis

criminatory grantees, and its reliance upon defendants' then

existing "constitutional . . . duty not to allow federal funds

-13-

to be used in a discriminatory manner by recipients," establish,

as a matter of law that defendants' conduct did indeed "violate

established statutory or constitutional rights of which a

reasonable person would have known." Therefore, the change in

the law of official immunity announced in Harlow means that

there is no longer any factual development required on remand

in order to decide the qualified immunity claim, and that it

must be rejected as a matter of law and plaintiffs permitted to

go to trial on the merits.

Ill

Defendants' Qualified Immunity Claim

Is Due to be Rejected Under Harlow

and Other Relevant Decisions Even

if this Court's Prior Ruling Is Not

Accorded Controlling Significance

We have suggested in the preceding section that in its

prior ruling, this Court made a determination of controlling

significance when it recognized the lack of discretion allowed

to defendants under the Crime Control Act and the federal

Constitution. Based upon that reading of the law, which is

entirely unaffected by any holding or discussion in Harlow,

this Court should reject the qualified immunity defense of the

defendant officials on this remand.

In the present discussion, we assume for purposes of argu

ment that the Court wishes to consider the qualified immunity

defense ab initio, without reference to its prior ruling. As

we demonstrate, Harlow and other relevant decisions establish

conclusively that defendants in this action are not entitled to

official immunity.

-14-

Under Harlow, the critical determination in evaluating a

defense of qualified immunity is whether the "statutory or

constitutional rights" alleged to have been violated by official

conduct were "clearly established . . . rights of which a rea

sonable person would have known." 50 U.S.L.W. at 4820, citing

Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. 555, 565 (1978), and Wood v.

Strickland, 420 U.S. 308, 321 (.1975). Thus, the Supreme Court

suggested that on official defendants' motions for summary judg

ment based on an assertion of qualified immunity, courts "may

determine, not only the currently applicable law, but whether

that law was clearly established at the time an action occurred."

Id. at 4820. We demonstrate below that the legal rights invaded

by defendants' conduct were, in fact, so "clearly established"

within the meaning of Harlow as to vitiate any defense of

qualified immunity in this case. Preliminarily, however, we

pause to consider how the state of "clearly established law"

7 /should be determined by the Court.—

7. In a footnote in Harlow, the Supreme Court Quoted

from Procunier v. Navarette, 434 U.S. at 565, and again stated

that it "need not define here the circumstances under which

'the state of the law' should be 'evaluated by reference to

the opinions of this Court, of the Courts of Appeals, or of

the local District Court."' 50 U.S.L.W. at 4820 n.32. The

question has, however, been widely addressed by the courts of

appeals and the federal district courts. Their consistent

conclusion has been that the state of the law, for immunity

purposes, may be established by decisions rendered not only by

the Supreme Court but also by the courts of appeals and the

federal trial courts, and by laws enacted by Congress and other

indicia of statutory and regulatory law, including interpre

tations of legislative requirements by the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts.

-15-

A. In Determining What Constitutional and Statutory-

Rights Were "Clearly Established" at the Time of

the Defendants' Actions in this Case, the Court

Should Look to Supreme Court Rulings, Its Own

Decisions, and Those of Other Federal Courts, as

well as to Statutory Enactments and Legislative History______ _______________________________

The experience of federal courts in passing upon defenses

of official immunity teaches that all potential sources must be

consulted in determining whether the constitutional and statutory

rights which are claimed to have been violated by defendants

were "clearly established" at the time the actions were taken.—^

1. Turning first to constitutional rights, it is almost

self-evident that decisions of the Supreme Court may conclusively

establish constitutional principles for purposes of the immunity

determination. E.g., Nekolny v. Painter, 653 F .2d 1164, 1170-71

(7th Cir. 1981) (Supreme Court decision in Elrod v. Burns, 427

U.S. 347 (1976), established the law on political firing);

Fowler v. Cross, 635 F.2d 476, 480-84 (5th Cir. 1981) (.right of

parolee to on-site revocation hearing established by Morrisev

v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (.1972)̂ and Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411

U.S. 778 (1973)); McNamara v. Moody, 606 F.2d 621, 625-26 (5th

Cir. 1979) (prisoner's right to mail letter established by

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974), decided a year and a

half prior to challenged conduct); Visser v. Magnarelli, 542 F.

Supp. 1331, 1336-38 (N.D.N.Y. 1982) (law on patronage employment

practices settled by Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (.1976) and

8. The Supreme Court has neither approved nor disapproved

this method of determining the "state of the law" for immunity purposes. See supra p.14 note 7.

-16-

Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S. 507 C1980)). See also Perez v.

Rodriguez Bou, 575 F.2d 21, 23-24 (1st Cir. 1978) (no immunity

for school official who suspended students without hearing one

week after Supreme Court decision in Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S.

565 (1975)).

Similarly, immunity may be rejected on the basis of lower

federal court rulings establishing the operative constitutional

principles. Thus, in Williams v. Treen, 671 F.2d 892 (5th Cir.

1982), the Fifth Circuit rejected the immunity defense in two

different instances based on lower court decisions. First, the

court held that a prisoner's right not to be denied necessary

medical treatment had been established by pre-1971 lower court

rulings well before the Supreme Court's decision in Estelle v.

Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 C1976). Id. at 901. Second, as to racial

segregation in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, the

Fifth Circuit held that the law had been established by a sum

marily affirmed district court decision in Alabama:

We believe that the right to be free from

general policies of racial segregation in

prison housing and administration was

clearly established in the opinions rendered

by Judge Johnson in Washington v. Lee, 263

F. Supp. 327 (M.D. Ala. 1966), and the

Supreme Court's per curiam affirmance in

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968).

671 F.2d at 902 (footnote omitted). See also, e.g., Gullatte

v. Potts, 654 F.2d 1007, 1012 (5th Cir. 1981) (prior Fourth and

Fifth Circuit decisions established law regarding prison offi

cials' responsibility to protect inmates who they know are in

danger); Mary and Crystal v. Ramsden, 635 F.2d 590, 600 (7th Cir

1980) (trial court decision within circuit established right of

incarcerated juvenile to call witnesses at disciplinary hearing)

-17-

Courts have also relied upon broad and well-known consti

tutional standards of conduct in reaching the conclusion that

particular actions are not covered by a defense of official

immunity. E.g., Williams v. Anderson, 562 F.2d 1081, 1101 (8th

Cir. 1977) (relying on "long line of [school desegregation]

court cases beginning with Brown v. Board of Education" to reject

claim that defendants had official immunity from liability for

employment discrimination); see also, Flores v. Pierce, 617 F.2d

1386, 1392 (9th Cir. 1980) ("The constitutional right to be

free from such invidious discrimination is so well established

and so essential to the preservation of our constitutional

order that all public officials must be charged with knowledge

of it. Cooper v. Aaron"), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 875 (1981).

2. As to statutory rights, the courts have frequently

canvassed relevant enactments and even regulatory requirements

governing official conduct and have held officials to the

standards expressed therein. For example, in Williams v. Treen,

supra, the Fifth Circuit passed upon qualified immunity as a

defense to a prisoner's alleged Eighth Amendment right to safe

and sanitary conditions. Finding only one prior case which

even "suggest[ed] that conditions such as those at Angola might

violate the constitutional rights of inmates," the court

"recongize[d] that the decisions to be found in the Federal

Reporter are not the only source of law governing the actions

of state prison officials." 671 F.2d at 898. The court then

rejected the immunity defense because the "conditions at the

facility violated applicable state fire, safety and health

regulations . . . . If an official's conduct contravenes his

-18-

own State's explicit and clearly established regulations, a

subjective belief in the lawfulness of his action is per se

unreasonable . . . . To hold otherwise would be to encourage

official ignorance of the law." Id. at 898-99, 899-900 (.foot

note omitted). See also Chavis v. Rowe, 643 F.2d 1281, 1288-89

(7th Cir.) (rejecting immunity in part on ground that officials

"may not take solace in ostrichism"), cert, denied, 454 U.S.

907 (1981).

Similarly, in Williams v. Anderson, 562 F.2d at 1102, the

Eighth Circuit also relied, in rejecting the claim of immunity

from liability for employment discrimination, upon the federal

Equal Pay Act as putting government officials on notice that

they could not pay blacks less than whites, although the precise

terms of the legislation required only that women be paid at the

same rate as men for substantially equal jobs. And in Calkins

v. Blum, 511 F. Supp. 1073, 1101 (N.D.N.Y. 1981), aff'd on basis

of district court opinion, 675 F.2d 44 (2d Cir. 1982), county

welfare officials were held not entitled to qualified immunity

because of the language of the Social Security Act and implement

ing administrative policies:

At the time of the plaintiffs' medicaid

determinations, federal law and HHS policy

statements required that SSI financial

eligibility criteria be . . . applied to

SSI medically needy persons and that

qualified individuals be provided a choice

of categories. Because the actions of the

County Commissioners ran directly contrary

to this federal law, of which the defen-

dants were obliged to know and follow, their

behavior cannot support a claim . . . of

qualified immunity.

-19-

511 F. Supp. at 1101 (.emphasis added) ; see also Kodecker v. Blum,

525 F. Supp. 867, 873 (N.D.N.Y. 1981) (since "the State Commis

sioner has violated federal law, this Court is also of the

opinion that inasmuch as she is being sued in her official capa

city, the State Commissioner enjoys no defense of 'good faith '").

3. In sum, obligations imposed by federal or state enact

ment or decisional law will undermine or preclude the availa

bility of the official immunity defense, and all potential

sources of legal standards should be canvassed in the process

of inquiring whether a reasonably performing official would

have known that his conduct violated applicable legal standards.

B. Clearly Established Constitutional and Statutory Law

Required Defendants to Withdraw Federal Financial Aid

From Recipients Practicing Invidious Discrimination

at the Time of the Acts Complained of in This Case

1. The constitutional obligation of government agencies

and officials to avoid entanglement with or the provision of

direct financial aid to institutions that discriminate was well

established at the time defendants in this case decided never

to initiate fund termination proceedings against discriminatory

grantees. Federal officials, like state officials, are barred

by equal protection principles from engaging in racial dis

crimination. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). This

constitutional obligation applies not just to direct involvement,

but as well to government "support" of discrimination "through

any arrangement, management, funds or property." Cooper v.

-20-

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19 (1958).-/

The principle was most emphatically reiterated by the

Supreme Court in Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), a

9. These clearly established principles announced by the

Supreme Court in 1954 and 1958, respectively, have been widely

applied by the lower federal courts in a variety of contexts.

For example, in three different cases — all summarily affirmed

by the Supreme Court — district courts in the late 1960's con

sistently held state tuition grants to students attending

racially discriminatory schools unconstitutional. Brown v.

South Carolina State Bd. of Educ., 296 F. Supp. 199 (D.S.C.),

aff1 d, 393 U.S. 222 (_1968) ; Poindexter v. Louisiana Fin. Assis-

tance Comm'n, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff'd,389 U.S.

571 (.1968); Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458,

475 (M.D. Ala.), aff'd sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389

U.S. 215 (1967). Accord, Coffey v. State Educ. Fin. Comm'n,

296 F. Supp. 1389 (S.D. Miss. 1969) (loans, as well as grants).

Particularly in the District of Columbia, where the defen

dants officially resided during the time periods relevant to

this case, these principles governing official conduct were

repeatedly made clear. In the first of its decisions involving

the provision of federal tax exemptions to discriminatory private

schools, the three-judge court in Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp.

1127, 1136 (D.D.C.), appeal dismissed, 398 U.S. 956 (1970),

squarely recognized that "[tjhe due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment does _not permit the Federal Government to act in aid

°f private racial discrimination." In its subsequent opinion —

supporting a judgment which was summarily affirmed by the Supreme

Court — the same court noted that while tax-exempt status was

more attenuated than direct financial aid, "it would be difficult indeed for [the government] to establish that such support

[through tax exemption] can be provided consistently with the

Constitution . . . . Clearly the Federal Government could not

under the Constitution give direct financial aid to [institutions]

practicing racial discrimination." Green v. Connally, 330 F.

Supp. 1150, 1164-65 (D.D.C.) (Leventhal, J.), aff'd sub nom. Coit

v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971). A nearly identical result was

reached in a 1973 case involving federal funding to discrimina

tory state employment services. Applying both the applicable

statutory law, see text infra at 22, as well as equal protection

principles, the court in NAACP, Western Region v. Brennan, 360

F. Supp. 1006, 1012 (D.D.C. 1973), expressly held that "both

-̂i-tle VI [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964] and the Fifth Amend

ment impose upon Federal officials not only the duty to refrain

from participating in discriminatory practices, but the affirma

tive duty to police the operations of and prevent such discrimina

tion by State and local agencies funded by them."

Other federal jurisdictions had earlier applied the same standards. E.g. , Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731, 740 (7th

' S r̂m^^ns v‘ Moses Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d 959, 967-70 (4th Cir. 1963) , certT denied, 376 U.S. 9T8 (.1964).

-21-

case challenging the provision of free textbooks by a state

agency to students attending racially exclusionary schools.

Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Burger unequivocally

declared that a government agency's "constitutional obligation

requires it to steer clear . . . of giving significant aid to

institutions that practice racial or other invidious discrim

ination." 413 U.S. at 467. This "steer-clear" obligation, the

Chief Justice pointed out, was hardly a novel constitutional

principle, but had long been applied by the Court in "consistently

affirm[ing] decisions enjoining state tuition grants to students

attending racially discriminatory private schools." Id. at

463 (citing, in a footnote, not only the decisions in Brown,

Poindexter and Lee, see supra p. 20 note 9, but also the summary

affirmance in Coit v. Green, see i d . ) ^ Accord, Gilmore v.

City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556 (.1974) .

10. In some other contexts the United States has suggested

that Norwood was tacitly overruled by Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229, 239-44 (1976), and Personnel Administrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256, 279 (1979), but there is absolutely no basis for

this interpretation. None of the opinions in Davis or Feeney

even mentions Norwood, because both cases addressed a completely

different issue. Those cases considered policies which in

operation allegedly had disparate impacts upon blacks and women,

respectively, and the issue in each was whether this dispropor

tionate impact alone made the policies unconstitutionally

discriminatory. Neither case involved express discrimination

of any kind, let alone findings of discrimination made by a

government agency which then continued to provide financial

aid to the discriminatory institution. Thus "one immediate and

crucial difference" between the instant matter and Washington

v. Davis or Personnel Administrator v. Feeney is that here, the

existence of discrimination is uncontested; the only question

is whether defendants were obligated to cease providing direct

federal monetary support for that discrimination. See Washington

v. Seattle School Dist. No. 1, 50 U.S.L.W. 4998, 5005 (U.S. June

30, 1982); cf., Rogers v. Lodge, 50 U.S.L.W. 5041, 5049-50 (U.S.

July 1, 1982T (Stevens, J., dissenting).

-22-

2. Statutory constraints also controlled defendants'

conduct. Initially defendants' conduct was statutorily governed

by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d,

which (similar in some respects to the obligation imposed by

the Fifth Amendment), barred federal officials from providing

assistance to discriminatory recipients or grantees. The

statute explicitly directs the termination of federal financial

assistance to grantees which are determined to practice dis

crimination. 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l. It has long been interpreted

to require federal officials to act promptly to withdraw federal

aid which might be used for discriminatory purposes. E.g.,

Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731, 740 (_7th Cir. 1971); Shannon

v . HUD, 436 F.2d 809 C3d Cir. 1970); Hicks v. Weaver, 302

F. Supp. 619, 623 (E.D. La. 1969).

Moreover, this Court a decade ago rejected federal officials

claim that Title VI vested them with broad discretion to commence

or to delay or decline to commence, administrative fund termina

tion proceedings once an investigation indicates that a grantee

is practicing discrimination. Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d

1159, 1162 (D.C. Cir. 1973) (en banc). Such discretion was

"untenable in light of the plain language of the statute," in

view of "Congress' clear statement of an affirmative enforcement

duty," and "in view of the admitted effectiveness of fund termina

tion proceedings in the past to achieve the Congressional

objective." Id. at 1162, 1163 n.4.

Whatever discretion, if any, may have remained after Adams,

it was removed frcm defendants only two months later, when

Congress made fund termination proceedings mandatory through

-23-

enactment of § 518(c) of the Crime Control Act of 1973, Pub. L.

No. 93-83, § 2 (Aug. 6, 1973), 87 Stat. 197, codified at 42

U.S.C. § 3766 (c) (Supp. V 1975). Of particular significance

was § 518Cc)(2), the administrative enforcement provision,

through which Congress removed the Title VI option of initially-

referring matters of noncompliance to the Justice Department

for possible judicial enforcement,— ^ and replaced it with a

mandatory procedure requiring that matters of noncompliance be

dealt with first through the initiation of fund termination

proc ee ding s'

11. Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act provides, at

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l (.1976)'(emphasis added):

Compliance with any requirement adopted

pursuant to this section may be effected

(1) by the termination of or refusal to

grant or to continue assistance . . . or

(2) by any other means authorized by law.

12. Section 518(c)(2) of the Crime Control Act of 1973

provided, at 42 U.S.C. § 3766(c)(2) (Supp. V 1975) (emphasis

added):

Whenever the Administration determines

that a State government or any unit of general

local government has failed to comply with

paragraph (1) of this subsection or an applic

able regulation, it shall notify the chief

executive of the State of the noncompliance

and shall request the chief executive to secure

compliance. If within a reasonable time after

such notification the chief executive fails or

refuses to secure compliance, the Administration

shall exercise the powers and functions provided

Tn section 3757 of this title [§ 509 of the

Act, which pertains to fund termination pro

ceedings] , and is authorized concurrently with

such exercise —

(A) to institute an appropriate civil

action;

(B) to exercise the powers and functions

pursuant to title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (section 2000d of this title); or

(C) to take such other action as may be

provided by law.

-24-

The reason for this mandatory enforcement was as obvious

as the requirement itself. As explained by Rep. Barbara Jordan,

the author of § 518(c)(2), the statutory "amendment was necessary

to reverse LEAA's traditional reliance on court proceedings to

correct discrimination, rather than undertaking administrative

13/enforcement of civil rights requirements."— • As Rep. Charles

Rangel later remarked, through enactment of § 518(c) (.2) in

August, 1973, Congress "imposed upon LEAA the most stringent

statutory civil rights mandate" governing any federal agency.— ^

3. Thus, as both a constitutional and statutory matter,

the defendant LEAA officials had "clearly established" obliga

tions to withdraw federal funding from grantees and recipients

whom their own investigations revealed to be practicing invidious

discrimination. As this Court aptly summarized it in 1980, the

defendants had "virtually no discretion . . . in deciding

whether to terminate LEAA funding of discriminatory recipients."

631 F.2d at 787.

13. 119 Cong. Rec. 20071 (June 18, 1973). As Rep. Jordan

explained her amendment, which became § 518(c) (2), id.:

The effect of my amendment . . . is to require

LEAA to first use the same enforcement procedure

which applies to any other violation of LEAA

regulations or statutes. That procedure of

notification, hearings, and negotiations is

spelled out in Section 509, which provides the

ultimate sanction of funding cutoff if

compliance is not obtained.

14. LEAA Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Crime of the

House Comm, on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 606 (1976).

-25-

C. Since Plaintiffs Alleged — and Both the Record And

Judicially Noticeable Materials Conclusively

Demonstrate — That Defendants Deliberately Continued

to Provide Federal Funds to Grantees Shown by Their

Own Investigations to Practice Invidious Discrimination,

Defendants Violated "Clearly Established Statutory or

Constitutional Rights of Which a Reasonable Person

Would Have Known" and Are Not Entitled to Qualified

Immunity_______________________________________________

1. A decade after the Supreme Court announced in Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19 (.1958), that it was unconstitutional for

government to "support" discrimination "through any arrangement,

management, funds or property," the LEAA was established. In

the first seven years of its existence, from 1968 until the

complaint in this action was filed in September, 1975, LEAA

distributed more than one and a quarter billion dollars to

state and local law enforcement agencies. Many of these

grantees were discriminatory; many in fact were found by the

federal courts to be violators of the law.

There appears to be no dispute in this case that the

responsible federal officials — the defendants here — never

denied federal funding to a discriminatory grantee, never

terminated funding to a discriminatory grantee, and never even

initiated fund termination proceedings against a discriminatory

grantee until after this complaint seeking damages was filed.

The scope of this unabated financial assistance to discriminatory

grantees is alleged in considerable detail in our complaint,

App. 4-39.— ^ It is confirmed in a report issued by the United

15. For example, plaintiffs alleged in 1[23 of their

complaint that since 1970, more than fifty law enforcement

agencies had been sued for discrimination and had ultimately

had judgments entered against them or had entered into consent

[footnote 15 continued on next page]

-26-

States Commission on Civil Rights in November, 1975, only two

months after the complaint in this case was filed. App. 481-

16 /623.— And it was made a matter of record in Congress,■both

prior to the filing of this action— ^ as well as

[footnote 15 continued from previous page]

decrees; that defendants had "provided LEAA funding to each of

these law enforcement agencies"; and that defendants "never

terminated that funding for civil rights noncompliance." App.

11. More specifically, each of the twelve individual plaintiffs

alleged in 1M[42-102 of the complaint that his or her own LEAA-

funded police department was known by the defendants to be

discriminatory, and that the defendants nonetheless refused to

terminate that direct financial assistance. App. 19-35.

16. The findings in the report, U.S. Comm'n on Civil

Rights, The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement Effort — 1974,

Vol. VI, To Extend Federal Financial Assistance 271-393, 773-77

(.1975) , closely paralleled the allegations in plaintiffs'

complaint. The Commission observed, for example, that "LEAA

staff states that the agency has never terminated funding be

cause of a civil rights violation." App. 607. The Commission

also found that "LEAA continues to fund jurisdictions in which

there is prima facie evidence of civil rights violations."App. 603, 623.

17. As discussed in greater detail infra pp. 27-28, in

1973, because of its impatience with LEAA's funding of blatantly

discriminatory grantees, Congress imposed upon defendants a

mandatory statute requiring the termination of funding to

discriminatory grantees. The need for this mandatory enforce

ment requirement — in the words of Rep. Barbara Jordan, the

author of the statutory amendment — was apparent not only be

cause "[o]ne need go no further than the reports of decided

Federal cases to obtain evidence of the persistence and pre

valence of racism in employment" but also because, "[i]n effect,

LEAA has had no civil rights enforcement program." 119 Cong. Rec. 20071 (June 18, 1973).

- 2 7 -

s u b s e q u e n t thereto.— ^

2. Defendants' statutory violations, first of Title VI

and later of § 518 Cc) (.2). of the Crime Control Act of 1973,

were also extensive, blatant, and documented by Congress. And

they are illustrated, at least to a limited extent, on the

record in this case, despite the trial court's denial of all

discovery.

Although LEAA, from its creation in 1968, was bound by an

"affirmative obligation to insure that the funds it distributes

. . . do not tend to support racial and sex discrimination" —

an "obligation [which] stems from the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments and is reflected in the policy underlying Title VI" —

19 /LEAA's response to this obligation was one of "failure."—

20 /LEAA "only reluctantly admitted its Title VI responsibilities,"—

and "[i]t took over two years . . . before LEAA recognized its

18. Congress' imposition in 1973 of a statutory mandate

requiring the termination of funding to discriminatory grantees,

see supra pp.22-24, was altogether disregarded by defendant

officials. As the House Judiciary Committee found in 1976:

The response of LEAA to the 1973 civil rights

amendment has been less than minimal.

* * * *

LEAA has never terminated payment of

funds to any recipient because of a civil

rights violation. Despite positive findings

of discrimination by courts and administrative

agencies, LEAA has continued to fund violators

of the Act.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1155, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 11 (1976).

19. LEAA Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House

Comm, on the Judiciary, 9 3d Cong., 1st Sess. 621 (1973) (Rep.

Hawkins).

20. Id. at 623.

-28-

responsibilities to prevent racial discrimination in the use of

21/its funds."— By the summer of 1973, when Congress was con

sidering Rep. Barbara Jordan's mandatory termination amendment

which became § 518(c) 12), Rep. Jordan observed that, "[i]n

2 2 /effect, LEAA has no civil rights enforcement program. " — ■

Despite the mandatory fund termination procedure enacted

by Congress in 1973, defendants continued to fund discrimination.

For example, the House Judiciary Committee concluded in 1976

that "[t]he response of LEAA to the 1973 civil rights amendments

23/has been less than minimal."— Even after the filing of this

lawsuit, defendants continued to violate their governing

statutory mandate: they "never terminated payment of funds to

any recipient because of a civil rights violation" and "con

tinued to fund violators of the Act."— ^

Of particular concern to Congress in 1976 was the renten-

tion by LEAA officials of their policy — as defined by defendant

Velde in 1975 — "to pursue court action and not administrative

25/action to resolve matters of employment discrimination. " — ■

21. 119 Cong. Rec. 22059 (June 28, 1973) (Sen. Bayh).

22. 119 Cong. Rec. 20071 (June 18, 1973).

23. H.R. Rep. No. 94-1155, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 11 (1976).

24. Id. See also the parallel findings of the United

States Commission on Civil Rights, discussed supra p. 26 note 16.

25. App. 85. This statement by defendant Velde was made

in a 1975 letter sent to Rep. Charles Rangel in an attempt to

explain why LEAA had violated § 518 (c) (2) by not initiating

administrative proceedings against the Philadelphia Police

Department, App. 76-86, a grantee which LEAA in 1974 had for

mally determined to be in noncompliance, App. 91. See also infra

pp. 30-31 note 31.

-29-

This was precisely the policy which Congress in 1973 had sought

"to reverse"— ^ when it enacted Rep. Jordan's amendment as §

518(c)(2). Nonetheless, as Rep. Charles Rangel observed in the

spring of 1976: "LEAA's unlawful regulatory preference remains

27/in effect today. " — ' In other words, the "attempt by Congress

[in 1973] to make clear to LEAA that it is to utilize and give

preference to its administrative enforcement powers rather than

its traditional reliance on judicial remedies has been blatantly

28/disregarded. " — ' Not only had the 1973 statutory mandate "not

been enforced, but it had been "ignored.

Defendants’ disregard of their nondiscretionary statutory

mandate is explicitly illustrated in at least one instance on

the record in this case. This example arises from defendants'

refusal, in early 1974 and continuing thereafter, to initiate

their mandatory fund termination proceedings against the

26. 119 Cong. Rec. 20071 (June 18, 1973) (Rep. Jordan).

27. LEAA Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Crime of the

House Comm, on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 606 (1976).

Rep. Jordan was a bit more blunt: "Simply put, LEAA's civil

rights regulations contravene the law." Id. at 446.

28. Id. at 606 (Rep. Rangel) (emphasis added).

29. Id. at 442 (Rep. Jordan),.

30. Id. at 443 (Rep. Conyers). As Representative Conyers

observed at somewhat greater length, id.:

We all enacted a law; everyone understood

what it meant; it went on the books; the

President signed it; and then it was ignored.

Now, some of us — yourself included —

are getting a little tired of this. We can

pass civil rights laws year in and year out,

and the agency charged with the enforcement

ends up being the prime noncompliant.

-30-

Philadelphia Police Department; this refusal is documented in

the record at App. 45-47, 51-111, 169-177; and it is briefly

summarized in the margin.— ^

31. After finding extensive discrimination in the Phila

delphia Police Department, and after concluding that voluntary

compliance could not be achieved, LEAA officials in late

January, 1975 formally determined the Police Department to be

in noncompliance. App. 45-46, 63-65. This determination was

confirmed in a mailgram from defendant Herbert Rice to Phila

delphia Police Commissioner Joseph O'Neill dated January 28, 1974

THIS WILL ALSO FORMALLY ADVISE YOU THAT

LEAA HAS DETERMINED THAT THE PHILADELPHIA

POLICE DEPARTMENT HAS FAILED TO COMPLY WITH

[THE NONDISCRIMINATION REQUIREMENTS]. THE

LEAA HAS FURTHER DETERMINED THAT COMPLIANCE

[WITH THE LAW] CANNOT BE ACHIEVED BY

VOLUNTARY MEANS.

App. 91 (upper case in original); see also App. 177. Rather

than initiating fund termination proceedings at this point, as

was statutorily required by § 518(c) (2), defendants instead

took a step which was statutorily authorized only after the

nondiscretionary first step of initiating fund termination

proceedings, id.:

ACCORDINGLY THIS MATTER HAS BEEN REFERRED TO

THE CIVIL RIGHTS DIVISION OF THE DEPARTMENT

OF JUSTICE FOR CONSIDERATION OF THE INSTITU

TION OF APPROPRIATE LEGAL PROCEEDINGS

One year later, in January, 1975, defendant Velde attempted

to explain this continuing violation of § 518(c)(2) by stating

that defendants chose to follow not their governing statute,

but instead their internal policy "to pursue court action and

not administrative action to resolve matters of employment

discrimination." App. 85. The existence of this illegal policy

was no secret. It was publically confirmed by the senior attor

ney in LEAA's Office of Civil Rights Compliance, in a 1975

interview: "She reports that, when the agency discovers dis

crimination, its policy is to seek judicial relief rather than

to stop paying out the money." App. 844 (emphasis in original).

Defendant Velde, also in January, 1975, admitted that

"[n]o formal administrative hearing was held by LEAA leading to

fund cutoff," that instead "LEAA funds are still going to the

Philadelphia Police Department," and that in fact "[t]wo $1 mil

lion discretionary awards were recently made." App. 84-85.

Only after this lawsuit for damages was filed on September

4, 1975, did defendants slowly begin to follow their governing

statute. On January 29, 1976, nearly five months after this

[footnote 31 continued on next page]

-31-

3. None of the defendant officials has ever asserted on

this record that he did not know, or should not have known, that

the unabated provision of direct financial assistance to dis-

driminatory grantees violated basic equal protection law

clearly established by the Supreme Court and repeatedly applied

by the lower federal courts, and also violated the statutory

mandates of Title VI and of § 518(c) (2) of the Crime Control

Act. Defendants, of course, could not have made such assertions.

As federal officials — indeed, as federal officials who also

are lawyers — defendants instead must be presumed to have

considerable knowledge of and respect for basic constitutional

law, and for their governing statutes.

In Harlow, the Supreme Court reiterated that the objective

test of qualified immunity "involves a presumptive knowledge

of and respect for 'basic unquestioned, constitutional rights.'"

50 U.S.L.W. at 4819, quoting from Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S.

at 322. Adhering to the necessity for government respect of

constitutional rights, the Harlow Court ruled that "qualified

[footnote 31 continued from previous page]

suit was filed and two weeks after plaintiffs moved for a pre

liminary injunction requiring initiation of administrative fund

termination proceedings against the Philadelphia Police Depart

ment based upon defendants' then two-year-old determination of

noncompliance, App. 40-185, defendant Velde finally did initiate

the nondiscretionary fund termination proceedings against Philadelphia, App. 195.

Similarly, three months after this lawsuit was filed,

defendants issued a proposed regulation in which they proposed

to reverse their policy of refusing to initiate fund termination

proceedings. 40 Fed. Reg. 56454 (December 3, 1975). Ten

months after this lawsuit was filed, defendants promulgated the proposed regulation as a final rule. 41 Fed. Reg. 28478 (June 12, 1976).

-32-

immunity would be defeated if an official 'knew or reasonably

should have known that the action he took within his sphere

of official responsibility would violate the constitutional

rights of the [plaintiff] { " Id. (emphasis by the Harlow

Court). Measured by this standard, defendants' blatant

disregard of their constitutional "steer clear" duty cannot

be justified, and deprives them of any claim to immunity.

Harlow enunciates a similar standard with respect to

statutory rights, and again, as we have demonstrated above,

there can be no credible argument whatsoever that any reasonable

LEAA official would have interpreted either Title VI or the

Crime Control Act to authorize continued funding of discrimina

tory grantees with no attempt to initiate administrative fund

termination proceedings. On this ground as well, therefore,

defendants' claim of qualified immunity must be rejected.

-33-

CONCLUSION

On this remand from the Supreme Court, the absolute immunity

and qualified immunity defenses should be rejected as a matter

of law, and this case should be remanded to the district court

for discovery and trial.

Dated: December 3, 1982

Respectfully submitted,

BURT NEUBORNE

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

212/944-9800

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

202/628-6700

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

CERTIFICATE' OF' SERVICE

The undersigned, counsel of record for plaintiffs-appellants,

certifies that two copies of the foregoing Supplemental Memorandum

for Plaintiffs-Appellants were served by United States first-class

mail this 3rd day of December, 1982, on counsel for the defendants-

appellees as follows:

Barbara L. Herwig

Robert E . Kopp

Appellate Section,

Civil Division

U.S. Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

Bennett Boskey

World Center Building

918 16th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

NORMAN J. CHACHKII4

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants