School District No. 20, Charleston, South Carolina v. Brown Brief of Interveners-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School District No. 20, Charleston, South Carolina v. Brown Brief of Interveners-Appellants, 1963. 72485449-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d266bbb5-792f-438e-a70a-4b28eebebca2/school-district-no-20-charleston-south-carolina-v-brown-brief-of-interveners-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

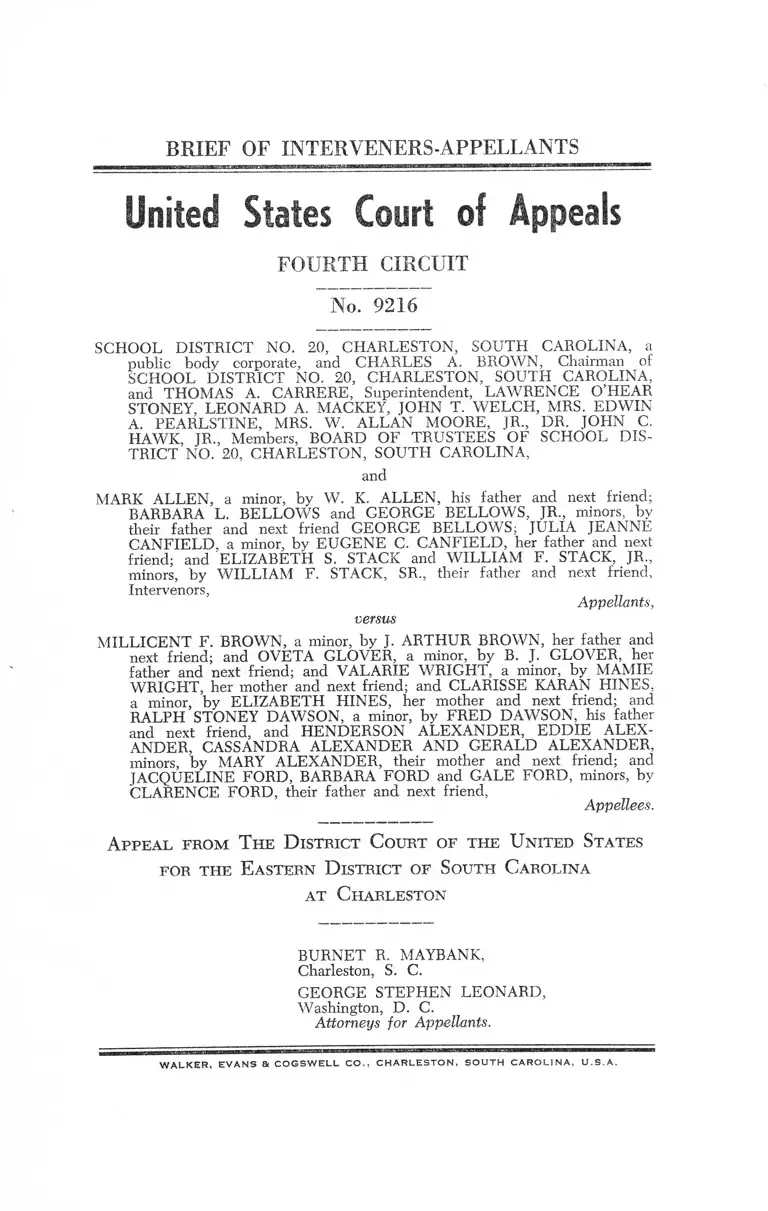

B R IE F OF INTERVENERS-APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 9216

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, a

public body corporate, and CHARLES A. BROWN, Chairman of

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and THOMAS A. CARRERE, Superintendent, LAWRENCE O’HEAR

STONEY, LEONARD A. MACKEY, JOHN T. WELCH, MRS. EDWIN

A. PEARLSTINE, MRS. W. ALLAN MOORE, JR., DR. JOHN C.

HAWK, JR., Members, BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DIS

TRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and

MARK ALLEN, a minor, by W. K. ALLEN, his father and next friend;

BARBARA L, BELLOWS and GEORGE BELLOWS, JR., minors, by

their father and next friend GEORGE BELLOWS; JULIA JEANNE

CANFIELD, a minor, by EUGENE C. CANFIELD, her father and next

friend; and ELIZABETH S. STACK and WILLIAM F. STACK, JR.,

minors, by WILLIAM F. STACK, SR., their father and next friend,

Intervenors,

Appellants,

versus

MILLICENT F. BROWN, a minor, by J. ARTHUR BROWN, her father and

next friend; and OVETA. GLOVER, a minor, by B. J. GLOVER, her

father and next friend; and VALARIE WRIGHT, a minor, by MAMIE

WRIGHT, her mother and next friend; and CLARISSE KARAN HINES,

a minor, by ELIZABETH HINES, her mother and next friend; and

RALPH STONEY DAWSON, a minor, bv FRED DAWSON, his father

and next friend, and HENDERSON ALEXANDER, EDDIE ALEX

ANDER, CASSANDRA ALEXANDER AND GERALD ALEXANDER,

minors, by MARY ALEXANDER, their mother and next friend; and

JACQUELINE FORD, BARBARA FORD and GALE FORD, minors, by

CLARENCE FORD, their father and next friend,

Appellees.

Ap p e a l f r o m T h e D is t r ic t C o u r t o f t h e U n it e d S t a t e s

f o r t h e E a s t e r n D is t r ic t o f S o u t h C a r o l in a

a t C h a r l e s t o n

BURNET R. MAYBANK,

Charleston, S. C.

GEORGE STEPHEN LEONARD,

Washington, D. C.

Attorneys for Appellants.

W A L K E R . E V A N S a C O G S W E L L C O . , C H A R L E S T O N , S O U T H C A R O L I N A , U S . A .

TABLE OF CASES

Bell v. School City o f Gary, Indiana — F. 2d—(C.

A. 7, Oct. 31, 1963) _____________________________25

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1 9 5 4 )______________24

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E . D. S. C. 1955) - .2 5

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954) ____________________________________ 4, 12, 26

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U. S. 294

(1955) ______________________________________ 30, 31

Calhoun v. Board o f Education o f Atlanta, 188 F.

Supp. 401 (N. D. Ga. 1959) _____________________.28

Commission v. Henninger, 320 U. S. 467 (1943) ______ 18

Frasier v. Board o f Trustees o f N. C. Univ., 134 F.

Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955) Affirmed per

curiam 350 U. S. 979 (1956) _____________________ 28

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 45 (1935) __________ 17

H ale v. Finch, 104 U. S. 261 (1881) _________________ 34

Hansberry et al v. L ee, 311 U. S. 32 (1940) __________ 34

Hart Steel v. Railroad Supply Co., 244 U. S. 294

(1917) _________________________ 34

Helvering v. National Outdoor Advertising Bureau,

Inc., 89 F. 2d 878 (C. A. 2, 1937) _______________18

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954) __________ 23

Kean v. Hurley, 179 F. 2d 888 (C. A. 8, 1950) ______34

Kessler v. Eldred, 206 U. S. 285 (1907) ____________ 34

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61

(1911) __________________________________________ 21

P a g e

M cGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420 (1961) ----------- 22

Mahnich v. Southern S. S. Co., 321 U. S. 96 (1944 )------ 18

Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457 ______________________ 21

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) _____________ 4

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d

156 (C. A. 5, 1957) _____________________________ 24

Padovani v. Bruchhausen, 293 F. 2d 546 (C. A. 2,

1961) ___________________________________________ 29

People v. Charles Schweinler Press, 214 N. Y. 395,

108 N. E. 639 (1915), appeal dismissed, 242 U. S.

618 (1916) ______________________________________15

People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438 (1883) ___________ 33

People v. W illiams, 189 N. Y. 131, 81 N. E. 778

(1907) __________________________________________ 14

The Pinas D el Rio, 277 U. S. 151 (1928) ____________19

Pyeatte v. Board o f Regents, 102 F. Supp. 407 (W.

D. Okla., 1951) affirmed without opinion, 342

U. S. 936 (1952) ___________________________ — 23

Polhemus v. American M edical Ass’n., 145 F. 2d

357 (C. A. 10, 1944) ____________________________ 28

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944) ___________ 17

Stell v, Savannah-Chatham County Board o f Edu

cation, 220 F. Supp. 667 (S. D. Ga. 1963) _____ 28,31

Sw eezey v. State o f N ew Hampshire, 354 U. S.

234 (1957) _________________________________

TABLE OF CASES— Continued

P a g e

17

Taylor v. Board o f Education o f New Rochelle,

191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), cert, denied,

368 U. S. 940 (1961) ____________________________27

Teamsters Union v. Vogt, Inc., 354 U. S. 284 (1957)____ 16

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940) __________ 17

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S.

144 (1938) ______________________________________ 20

W augh v. Board o f Trustees, 237 U. S. 589 (1 9 1 5 )-------23

W ebb v. State University, 125 F. Supp. 910 (N. D.

N. Y. 1954), appeal dismissed, 348 U. S. 867

(1954) ____________________________ 23

W illiamson v. L ee Optical o f Oklahoma, Inc., 348

U. S. 483 (1955) ________________________________ 22

Statutes:

South Carolina Pupil Assignment Law, §§ 21-247

et seq., S. C. Code of Laws (1962) _______________ 2

United States Code, Title 28, § 1291__________________ 2

Miscellaneous:

American Jurisprudence, Courts, p. 290 _______________35

Annotation, “Conflict of Laws—Questions for Jury,”

89 ALR 1278 _____________________________________13

21 C.J.S. 305, 386 __________________________________ 35

Douglas, William O., W e The Judges, p. 398

(1955) __________________________________________24

TABLE OF CASES— Continued

P a g e

TABLE OF CASES— Continued

P a g e

Fahr, S. M., & Ojemann, R. H., “The Use of Social

Behavior Science Knowledge in Law,” 48 Iowa

L. Rev. 59 (1962) _______________________________ 29

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 8 ------------------- 28

Frankfurter, Felix, Note, 28 Harv. L. Rev. 790

(1915) _______________________________________ 15,31

Myrdal, An American Dilemma, p. 147 --------------------31

New York Times, November 11, 1963 (Statement

of Kenneth B. Clark) ------------------------------------------ 8

Rules of Board of Trustees of Charleston (S. C.)

School District No. 20, June 10, 1959 ------------------- 2

“Science and the Race Problem,” Science, Novem

ber 1, 1963, p. 558 _______________________________ 31

Washington Post, October 26, 1963, (article on

“track system” of grouping pupils) ----------------------- 11

B R IE F OF INTERVENERS-APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 9216

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, a

public body corporate, and CHARLES A, BROWN, Chairman of

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and THOMAS A. CARRERE, Superintendent, LAWRENCE O’HEAR

STONEY, LEONARD A. MACKEY, JOHN T. WELCH, MRS. EDWIN

A. PEARLSTINE, MRS. W. ALLAN MOORE, JR., DR. JOHN C.

HAWK, JR., Members, BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SCHOOL DIS

TRICT NO. 20, CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA,

and

MARK ALLEN, a minor, by W. K. ALLEN, his father and next friend;

BARBARA L. BELLOWS and GEORGE BELLOWS, JR., minors, by

their father and next friend GEORGE BELLOWS; JULIA JEANNE

CANFIELD, a minor, by EUGENE C. CANFIELD, her father and next

friend; and ELIZABETH S. STACK and WILLIAM F. STACK, JR.,

minors, by WILLIAM F. STACK, SR., their father and next friend,

Intervenors,

Appellants,

versus

MILLICENT F. BROWN, a minor, by J. ARTHUR BROWN, her father and

next friend; and OVETA GLOVER, a minor, by B. J. GLOVER, her

father and next friend; and VALARIE WRIGHT, a minor, by MAMIE

WRIGHT, her mother and next friend; and CLARISSE KARAN HINES,

a minor, by ELIZABETH HINES, her mother and next friend; and

RALPH STONEY DAWSON, a minor, by FRED DAWSON, his father

and next friend, and HENDERSON ALEXANDER, EDDIE ALEX

ANDER, CASSANDRA ALEXANDER AND GERALD ALEXANDER,

minors, by MARY ALEXANDER, their mother and next friend; and

JACQUELINE FORD, BARBARA FORD and GALE FORD, minors, by

CLARENCE FORD, their father and next friend,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m T h e D is t r ic t C o u r t o f t h e U n it e d S t a t e s

f o r t h e E a s t e r n D is t r ic t o f S o u t h C a r o l in a

a t C h a r l e s t o n

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the District Court in Civil Action No. 7747,

August 22, 1963, is not officially reported, but may be found

in the Appendix of Appellants, pp. 276-96.

(1)

2 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

JURISDICTION

The opinion and order of the District Court was filed Au

gust 22, 1963. The order of the District Court refusing the

petition of the defendants to amend the findings and con

clusions and to vacate or amend the judgment and order was

filed September 6, 1963. The notice of appeal of the defend-

ants-appellants and the intervenors-appellants (hereinafter

called “intervenors”) was filed October 2, 1963. The juris

diction of this Court is conferred by Title 28, Section 1291,

of the United States Code.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Is the District Court foreclosed as a matter of law from

considering uncontradicted proof that there is such an inherent

variation in learning patterns between the average negro and

white child in the public schools of Charleston that a reasonable

classification of such children for educational purposes requires

separate and different programs and classes to avoid major

educational loss and psychic injury?

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS INVOLVED

South Carolina Pupil Assignment Law, §§ 21-247 et seq.,

S. C. Code of Laws (1962).

Rules of Board of Trustees of Charleston School District

No. 20, adopted June 10, 1959.

STATEMENT

The action was tried on August 5 and 6, 1963. Intervenors-

appellants introduced, without contradiction or rebuttal, the

testimony of witnesses conceded by plaintiffs-appellees to be

authorities in their respective fields. These witnesses were

unanimous to the effect that test differences between white

Millicen t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 3

and negro students in mental maturity and educational achieve

ment in Charleston schools showed inherent educational varia

tions of such a degree and character that the integration re

quested by plaintiffs would destroy the quality of instruction

in the City schools and would cause severe and permanent

educational and psychological injury to both negro and white

school children.

The Court refused to consider or make findings on this

evidence, holding instead:

“The position taken by the defendants and the inter-

venors in effect, asks this Court (a U. S. District Court)

to overrule the United States Supreme Court, the Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals and all the numerous decisions

by those courts, reiterating, expanding and amplifying the

holdings of the United States Supreme Court in Broivn

v. Board o f Education (supra). Under the doctrine of

stare decisis, this Court has no such authority.”

Accordingly, the legal question before this Court is whether

Brown v. Board o f Education holds that the Constitution re

quires not merely non-discrimination by race, but affirmative

and compulsory congregation regardless of any adverse edu

cational or psychological result to the children.

TH E ISSUE

This case presents a small but novel and important frag

ment of the over-all problem of negro-white education in

America—whether political or educational values govern the

problem of non-discriminatory schooling.

Under present world tensions, the inadequate education of

a single generation could cost this country its leadership and

endanger its constitutional system. If the uncontroverted facts

presented to the Court below are true—and on this record no

other conclusion can be drawn—the compulsory congregation

of classes requested by the plaintiffs would seriously diminish,

and could ultimately destroy, the education of thousands of

Charleston children, both white and negro. The rule con

tended for by plaintiffs, if applied generally, could sharply

diminish the education of all other children similarly situated.

Is the position of the plaintiffs below one taken on behalf

of these children, or is it merely another phase of that political

battle of their elders which the Supreme Court described in

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963)? Has the problem

of education become so interinvolved with political, emotional

and ideological assertion, that the law is powerless to consider

any consequential injury to the children whose education is

at stake?

It is the position of intervenors-appellants that the educa

tional benefit and psychological health of these specific negro

and white children must be the principal issue in this or any

school case and that any statute or regulation based upon

such facts, rather than upon race or color as such, falls within

the ambit of permissible state action under its power to rea

sonably classify citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment

for health, education or welfare reasons.

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), as we

later show in detail, is not in conflict with our statement that

optimum education for both white and negro children is the

basic issue in the present case. There the Court—acting on a

specific factual showing and “Brandeis Brief”—held that the

negro children, in the four areas considered, were injured by

the mere existence of segregated schools.

Here, the record shows a wide and educationally invariable

divergence between the learning ability of white and negro

students in Charleston. It shows that a single curriculum, or a

4 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

Millicen t F. B rown, e t al, Appellees 5

single class and common educational standards pedagogically

unfitted to their differing capacities and talents, would cause

irreparable harm to both races. The record shows that the

true injury would be greater by integration here than was

found by the Supreme Court to exist from segregated schools

in Kansas and Delaware in the first Brown case.

We reiterate that whether or not these children will in fact

be injured by compulsory congregation in Charleston is and

must be the issue before the trial court and the relevance of

such evidence is the sole issue before this Court.

FACTS

T he Charleston P ublic S chool System

The population of School District No. 20 is 65,925; 32,313

white, 33,612 negro. There are 12,647 public school students

in the District, 9,539 negro, 3,108 white. [93* ] The school

system operates six schools for white children and nine schools

for negro children, the facilities of which are substantially

equivalent. [76-83, 94-8, 136-9, 144-5]

The teaching programs, through a choice of elective subjects

and teacher adaptation of state and national progress norms,

are varied to meet the different educational aptitudes of white

or negro students in each individual school. [90-1, 95-6, 122-4,

126-9]

Com parative Educational A ptitudes: Charleston

The educational aptitudes of students in the Charleston,

South Carolina, school system have been measured over a

period of ten years by educationally standardized psychometric

intelligence and subject achievement tests. These show wide

divergencies between the average and median proficiency of

'AH references are to pages in Appendix of Appellants.

School D ist . No. 20 & M ark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v .

white and negro students, respectively. [100-22, 151-8, 162,

166-7, 198-9] Specifically:

(1 ) The median I.Q. of all negro students averages 15-20

points below the median for all white students. While both

groups have a normal distribution of high and low individuals

around this median figure, the difference in average is such

that the negro overlap of the median white child is only 10%

to 20%. This compares to an overlap of 50% which would be

shown by groups of similar learning capacity. [20-1, 152-8,

166-7]

(2 ) This difference does not remain constant in the indi

viduals of the two races. It increases at a relatively constant

rate of one year in four, such that the grade achievement levels

of negro children which only lag behind those of white stu

dents by an average of a half to one year in the primary

grades will increase to three years plus by the end of the

secondary grades. This rate is independent of the intelligence

quotients (mental maturity) of the children so that negro-

white students matched for intelligence do not thereafter re

main at the same level but separate thereafter at the rate

indicated. [104-19, 150-2]

(3 ) The basic educability difference between the two

groups exists not only as to mental age and learning rate but

varies by type of subject, e.g., the greatest difference being

found in mathematical abstraction, the least in areas of memo

rization. [151, 162, 198-9]

C om parative Educational A ptitudes: O ther Parts o f United

States and Canada

The learning pattern differences shown to exist in Charles

ton students are substantially identical to all known tests of

negro and white students whether tested in the separated

Millic en t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 7

schools of the South or the inter-mixed schools in the North

and West. [133-4, 164-70, 203-4, 218-21]

Not only were these differences standard in all tested areas

but various studies were made which showed they were in

herent, not caused by the home or school environment of the

students. Such studies tested negro and white groups where

social and environmental factors had been matched and where

change of condition was shown to be unable to change the

results. Only an educationally negligible proportion of these

differences between the two ethnic groups was shown to be

a possible result of educational or socio-economic factors.

[133-4, 160-1, 164-70, 191-2, 198-9]

Physiological D ifferences

These differences in the educability of negro and white

students are functionally related to natural physiological dif

ferences between the two races arising from their different

origins.

The variations in intellectual abilities are thus innate, re

lated both quantitatively and qualitatively not to color or race

but to certain common physical variances in the relative size,

proportion and structure of the brain and neural system. These,

within scientific limitations, permit the prediction of differences

in personality and learning capacity directly proportioned to

the tested differences. [176-92, 198-201]

Psychological Problem s

Modern psychological doctrine shows that a failure to main

tain the existing standards of a white or mixed class creates

a serious psychic problem of frustration on the part of the

negro child and forces him to compensate by attention-creating

anti-social behavior. In New York, 37% of all negro truants

stated that they had run away from home because of inability

to keep up in school. [163-4, 167-8, 171-4, 222-4, 237-9]

The result has been that in all cities where there is a large

negro school population in mixed classes, this situation has

caused serious disciplinary problems and has thereby deprived

both negro and white children of an effective education. The

chief psychologist of the organization supporting the plaintiffs

in this case described negro graduates of the highly rated New

York high schools as “functional illiterates” unable to read or

write effectively after twelve years of school. Moreover, he

stated: (New York Times, November 11, 1963).

“The retardation is cumulative. [This is the divergent

rate measured in the Charleston studies.] As the children

become more retarded, they become more and more dis

affected from school—they become restless, often un

manageable over discipline problems or withdrawn, seek

ing escape with lowered motivation, and desire to leave

school at the earliest opportunity.”

Counsel for the same organization shows that 20 times as

high a percentage of negro students attain minimum College

Entrance Examination standards under conditions of separate

schools in the South as they do from intermixed schools in the

North. [146-7, 219-22, 235-6]

An additional factor which directly affects the education

of both ethnic groups is that which results from the inter

mixture of recognizably different groups in a single class. The

principles of that branch of psychology known as social

dynamics have shown that all individuals identify themselves

with specific groups such as trades, nationalities, sex, religion,

age and race. Such identifications are made at the unconscious

level in infancy and are essential to normal personality de

velopment. The strongest of all such identifications are visible

8 School D ist . No. 20 & Mabk Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v.

Millic en t F . B rown, e t al, Appellees 9

physical and psychological differences. Identification on the

basis of visible differences will occur whether or not the indi

vidual wishes it and is a form of unavoidable self-identifica

tion. This reaction to physically specific differences between

people is a universal human characteristic and compels group

identification along racial lines and racial association prefer

ences to be formed in early pre-school years for both negro

and white children. In fact, the tests referred to by the Su

preme Court in the original Brown case were, in effect, tests

of such group identification, and the psychological injury on

w hich that Court acted was not the acquiring o f this racial

identification but the loss o f it. [209-15, 224-32]

Contrary to common belief, group preference is strength

ened by group contacts. Where two substantial groups of

students having obvious visible group characteristics are mixed

in a single classroom, the reaction is to increase or exacerbate,

in increasing proportion to the degree of contact involved, any

existing racial preferences or hostilities. The attendant con

flict which this situation causes diminishes available classroom

time and attention and defeats pro tanto the educational op

portunity of the children of both groups. It is the unconsidered

factor which in large part has led to the severe impairment

of the standing of school systems where group integration is

in effect. [215-8, 235-6]

Selective Transfers

Apart from the mass congregation of unlike pupils which

plaintiffs demand, a further consideration is whether transfers

should be made of negro students in the top 20% of their group

who could meet the progress norms of an equivalent white

class. Concededly, selective transfers of such students would

not injure white students in any sense comparable to the ef

fects of total group integration. However, it was shown that

this would be an even greater source of psychological harm

to the negro children selected and to the group not capable

of meeting such transfer standards. [222-4]

On the basis of the tests, a negro student easily able to

excel in a white class at the start of a school year would be

forced to press to keep up by its end and be overpressed in

increasing degree thereafter. Also, the difference in learning

patterns invalidates a prediction as to the educational success

of the individual in a class which stresses reading comprehen

sion or mathematical calculation. [104-19, 150-2, 162, 198-9]

A negro student so transferred would lose his sense of out

standing achievement within the group with which he identi

fies himself, would be inescapably conscious of the social

preferences of the new group and, if he tries to transfer his

identity to the white class, could readily cause himself severe

psychological injury. [221-4]

The adverse effects on the non-transferred negro children

would be even more injurious. The loss of their group leaders

would substantially increase any existing presumption of racial

inferiority. Self-viewed as a rejected group, the competitive

drive of those not transferred is hurt, drop-outs become com

mon and they fail to secure the education which they could

undertake. [222-3]

Educational and Psychological Advantages o f D ivided School

Systems

There is no modern psychological evidence of mental or

educational injury resulting to negro students by education

in separate schools. To the contrary, every known experimental

authority has shown greater personality stability and a higher

degree of learning accomplishment in the divided school sys

tem. This is even true as to the author of the principal study

10 School D ist . No. 20 & Mask Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

Millic en t F . Bhown, e t al, Appellees 11

relied on by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board o f Educa

tion, Although not brought to that Court’s attention, the same

authority demonstrated in an earlier study of a far larger

number of children, that the psychological injury traceable

to loss of racial identification was more common in integrated

schools in the North than in segregated schools in the South.

No other reference listed by the Supreme Court suggests any

experimental evidence that compulsory congregation would

benefit negro children. [164, 220-2, 226-32]

Sum m ary

The respective educational capacities of negro and white

children vary to such a degree that it is not pedagogieally or

psychologically feasible to teach both groups in the same

class, with the same subjects, texts and achievement norms.

In addition to class disciplinary problems illustrated by Wash

ington experience, any such mixture would either lower the

prevailing white progress norm to the point of leaving the

white children uneducated; or, if the national grade norms

used for the white students were to be continued, a majority

of the negroes would fail. Any middle of the road level would

educate neither group.9 “Equal” education is thus a denial

of “equal educational opportunity.”

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. Questions of fact are matters as to which reasonable

men can differ. The development of new scientific data re

quires reconsideration of conclusions drawn from earlier evi

dence.

2. Evolutionary constitutional interpretation is often based

on social and other scientific proof and when so based is al-

*cf. attack on the modem track system of grouping faster and slower students

together as a form of “resegregation” in integrated Northern schools. (Wash

ington Post, October 26, 1963)

ways open to a demonstration of later knowledge or prior

omission of pertinent principle.

3. Under the equal protection clause, States are permitted

to make reasonable classifications of their citizens for health,

education or welfare purposes where the basis of division is

relevant to the end to be accomplished. In such classifica

tions, it is the group characteristic that must be considered

and the fact that the underlying justification may not apply

to exceptional individuals does not delimit the practical neces

sity for classifications.

4. A true difference in learning ability is a meaningful basis

for reasonable classification of the groups concerned. Race

or color in such a case is merely a “convenient index” identi

fying such group and is not itself the basis of or reason for

the selection used.

5. Brown v. Board o f Education o f T opeka does not hold

to the contrary. Actually it supports the criteria here used.

6. Neither stare decisis nor resjudicata apply to these facts.

ARGUMENT

It is the position of intervenors that the Supreme Court’s

holding in Brown v. Board o f Education , 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

that injury resulted to negro children from separate schooling

was a holding of fact on the record before it in that case. If

so, the District Court erred in holding that the Brown decision

foreclosed judicial consideration of evidence that congregated

schooling of negro and white children in Charleston, South

Carolina, would result in educational and psychological dam

age to both.

We first consider the broad distinction between fact and

law. We then inquire into the nature of facts underlying rea

12 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

sonable classifications under the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment. We then will review the first

Brown case to show that the conclusion that separate schools

are “inherently unequal” is derived from a finding of injury

to negro children while the actual fact is to the contrary. Hence,

the continued operation of a dual school system in Charles

ton, South Carolina, constitutes a reasonable and constitu

tionally permissible classification.

L

FACTS vs. LAW

The discovery of a clear-cut criterion distinguishing between

fact and law presents a difficult problem. One situation in

which the distinction must be made is in determining what

are matters of fact which should be submitted to a jury and

what are matters of law which must be decided by the court.

The rule which has been distilled from this practice, and

which is completely applicable here is to be found in Annota

tion, “Conflict of Laws—Questions For Jury,” 89 ALR 1278,

where it is stated:

“When it is said that a certain question is for the jury,

it is meant that, assuming that there was sufficient evi

dence to prove its primary facts, or to sustain a verdict

if rendered, the facts are such that fair-minded people

may differ as to their legal effect. . . . On the other hand,

when it is said that a certain question is for the court,

it is meant that, assuming that there is sufficient evidence

to prove its primary facts, the facts are such that fair-

minded men may not possibly differ as to their legal

effect, and that therefore the court itself, without the

intervention of a jury, must apply a predetermined rule

as to the legal effect of such facts.”

Millic en t F . Brown, et al, Appellees 13

Reasonable men do not differ on the question of whether

negro and white persons in America are constitutionally en

titled to equality of political rights, to equality of employment

opportunities, or to equality of educational development. But

reasonable men do and must differ as to whether in any given

situation the applicability of such a general principle is being

evenhandedly applied or not and whether the action of a

state upon given facts is a reasonable classification or an un

constitutional discrimination.

The classification of persons with reference to “race” is a

specific example of a situation requiring the application of

evidentiary facts, rather than the mechanical invocation of a

predetermined rule of law. “Race” is today considered a bad

word. Yet it is actually only a coined word. As the anthro

pologists point out, each man is free to define “race” for him

self. The only obligation is that he take recognizable human

characteristics as a basis for his definitions.

Under some definitions, there are as few as three races, under

others as many as thirty-five or more. Conceivably one could

define a race of men and a race of women, even though it

would be necessary to concede considerable overlap in many

intellectual and physical capacities. It was once held by a high

court that a division of citizens into male and female for pur

poses of state economic legislation was unconstitutional in

denying equal protection of the laws.

The Court of Appeals of the State of New York in People

v. W illiams, 189 N. Y. 131, 81 N. E. 778 (1907), invalidated

as unconstitutional a State statute which prohibited night work

for women in factories during specified hours. The court held

that on the record before it there was nothing to show that

an adult woman should not be “entitled to be placed upon

an equality of rights with the man” (id., 137).

14 School D ist . No . 20 & Mark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v .

Millic en t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 15

This did not solve the underlying problem, which was in

fact based upon the physiological differences between the sexes

and the resultant necessity for difference of treatment in grant

ing them equal employment opportunity. Accordingly, eight

years later, when an attack was made upon a similar successor

statute, the defense proved for the first time the scientific

basis for the difference between men and women which re

quired that different standards be applied. In this case, the

Court of Appeals in People v. Charles Schweinler Press, 214

N. Y. 395, 108 N. E. 639 (1915), appeal dismissed, 242 U. S.

618 (1916), held that its former decision in W illiams was

necessarily limited to the facts of that record, and that the

failure to show the relevant differences between the two groups

was the cause of the earlier decision.

In upholding the statute, the Court of Appeals specifically

considered the problem offered by the exceptional case. It was

“not a basis for a constitutional objection” to a statute like this

“that in exceptional cases it may prevent employment of some

women for a short time between those hours under such con

ditions as would be productive of no substantial harm” (214

N. Y. 395, 407).

Distinguishing the W illiams case, the court said (id., 410-1):

“But the facts on which the former statute might rest

as a health regulation and the arguments made to us in

behalf of its constitutionality were far different than those

in the present case. . . . While theoretically we may have

been able to take judicial notice of some of the facts, . . .

actually very few of these facts were called to our atten

tion.”

The Schweinler case was commented upon in a Note, 28

Harv. L. Rev. 790 (1915), written by Felix Frankfurther, in

which he stated (791):

16 S chool D is t . No . 2 0 & M a rk Al l e n , e t a l , Ap p e l l a n t s , c .

“First: Questions as to the constitutionality of modern

social legislation are substantially questions o f fact. The

formulae of the Bill of Rights do not furnish yardsticks

by which the validity of specific statutes can be measured.

Concepts like ‘liberty’ and ‘due process’ are too vague in

themselves to solve issues. They derive meaning only if

referred to adequate human facts. The legal principles

cannot be employed in vacuo. . . . Deference to this

data [on the relevant male-female differences by the

Factory Investigating Committee] was the very founda

tion of the court’s decision on the legal question.

“Secondly, and closely following as a corollary, inas

much as facts are dynamic, constitutional decisions upon

which they must be based cannot be static. Conditions

change, legislation deals with these changed conditions,

and so must the courts. A book like Miss Goldmark’s

‘Fatigue and Efficiency’ com pletely undermines prevalent

assumptions as to facts and, thereby, may well destroy

the very groundwork of prior judicial decisions. There

fore, the doctrine o f stare decisis has no legitim ate ap

plication to constitutional decisions w here the court is

presented with a new body o f knowledge, largely non

existing at the time o f its prior decision. This was pre

cisely the situation in the Schweinler case. The seven

years that elapsed between it and the Williams case de

veloped an overwhelming mass of authoritative data, and

it is by the light of such new knowledge that the justifica

tion of legislative action must be determined.” ( Emphasis

added)

At a later date, Mr. Justice Frankfurther referred to his

earlier article and approved the principle of the Schweinler

case in Teamsters Union v. Vogt, Inc., 354 U. S. 284 (1957),

affirming an injunction against peaceful picketing, contrary

Millic en t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 17

to the Court’s prior decision in Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S.

88 (1940); saying (354 U. S. 284, 289):

“Soon, however, the Court came to realize that the

broad pronouncements, but not the specific holding, of

Thornhill had to yield ‘to the impact of facts unforeseen,’

or at least not sufficiently appreciated.”

Similar recognition of the principle that new scientific data

should change earlier conclusions, is shown in Sweezey v.

State o f New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 (1957), in which the

Supreme Court departed from earlier ruling to reverse a “sub

versive activities” conviction. The concurring opinion stated

(id., 261-2):

“Progress in the natural sciences is not remotely con

fined to findings made in the laboratory. Insights into

the mysteries of nature are born of hypothesis and specula

tion. The more so is this true of the pursuit of under

standing in the groping endeavors of what are called the

social sciences, the concern of which is man and society.

The problems that are the respective preoccupations of

anthropology, economics, law, psychology, sociology and

related areas of scholarship are merely departmentalized

dealing, by way of manageable division of analysis, with

interpenetrating aspects of holistic perplexities. For so

ciety’s good—if understanding be an essential need of so

ciety-inquiries into these problems, speculations about

them, stimulation in others of reflection upon them, must

be left as unfettered as possible.”

As a further example of change based on revised or fuller

evidence, let us take the case where the Supreme Court ruled

that the right to vote in a Texas primary was not a right guar

anteed by the Constitution, Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S.

45 (1935). Then, nine years later in Smith v. Allwright, 321

U. S. 649 (1944), on being shown the meaning of a primary

election in a southern state such as Louisiana, the Court re

versed itself, saying of its earlier decision that it had “looked

upon the denial of a vote in a primary as a mere refusal by a

party of party membership.”

The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, in Helvering v. Na

tional Outdoor Advertising Bureau, Inc., 89 F. 2d 878 (C. A.

2, 1937), denied as a business deduction for tax purposes the

legal fees involved in negotiation resulting in a consent decree

in an antitrust suit. Thereafter the Board of Tax Appeals,

based solely upon the Second Circuit’s ruling, denied a deduc

tion for lawyers’ fees incurred in the contesting of a fraud

order of the Postmaster General. In Commissioner v. Hein-

inger, 320 U. S. 467 (1943), the Supreme Court reversed and

remanded to the Board of Tax Appeals holding that the Board

“was not required to regard the administrative finding of guilt

. . . as a rigid criterion of the deductibility of respondent’s

litigation expenses” (id., 475).

In remanding the case to the Board, the Supreme Court

significantly concluded (ibid):

“Whether an expenditure is directly related to a busi

ness and whether it is ordinary and necessary are doubt

less pure questions of fact in most instances . . . How

ever, as we have pointed out above, the Board of Tax

Appeals here denied the claimed deduction not by an

independent exercise of judgment but upon a mistaken

conviction that denial was required as a matter of law.”

These distinctions between rules of law and their controlling

determinations of fact are aptly illustrated by Mahnich v.

Southern S. S. Co., 321 U. S. 96 (1944), where the Supreme

Court reversed a holding of the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit that a ship, the “Wichita Falls,” was not unseaworthy

18 S chool D is t . No. 20 & Mark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v.

M illicen t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 19

by reason of the defective rope used in rigging the staging. The

Court held that the Court of Appeals had erroneously believed

itself to be bound by a statement in an earlier Supreme Court

opinion, The Pinar Del Rio, 277 U. S. 151, 155 (1928), as

follows:

“The record does not support the suggestion that the

Pinar Del Rio was unseaworthy. The mate selected a

bad rope when good ones were available.”

In Mahnich, the Supreme Court remarked that (321 U. S.

96, 98-9):

“A finding of seaworthiness is usually a finding of fact

. . . . Ordinarily we do not, in admiralty, more than in

other cases, review the concurrent findings of fact of

two courts below.”

The Court, however, found as a fact that ( id., 103):

“The staging from which petitioner fell was an ap

pliance appurtenant to the ship. It was unseaworthy in

the sense that it was inadequate for the purpose for

which it was ordinarily used, because of the defective

rope with which it was rigged.”

Explaining why the two courts below were in error in rely

ing on the quoted statement from The Pinar D el Rio, supra,

the Court said ( id., 104-5):

“The statement from The Pinar D el Rio, supra, relied

upon by the two courts below, could be taken to support

their decision, only on the assumption either that the

presence of sound rope on the "Wichita Falls’ afforded an

excuse for the failure to provide a safe staging, or that

antecedent negligence of the mate in directing the use

of the defective rope relieved the owner from liability

for furnishing the appliance thereby rendered unsea

worthy. But as we have seen, neither assumption is

tenable in the light of our decisions before and since

The Pinar D el Rio, supra. So far as this statement sup

ports these assumptions, it is disapproved.”

The importance of factual inquiry in determining questions

of consitutionality is illustrated by United States v. Carotene

Products Co., 304 U. S. 144 (1938). In an opinion upholding

the validity of a Federal act which prohibited the shipment

of filled milk in interstate commerce, the Court said (id., 153):

“Where the existence of a rational basis for legislation

whose constitutionality is attacked depends upon facts

beyond the sphere of judicial notice, such facts may prop

erly be made the subject of judicial inquiry . . . , and the

constitutionality of a statute predicated upon the existence

of a particular state of facts may be challenged by show

ing to the court that those facts have ceased to exist.”

The foregoing authorities establish that constitutional de

terminations based upon particular showings or assumptions

of fact are always open to reconsideration when a different

state of facts can be shown in a particular situation. The

change of circumstance may be either a real difference in the

factual situation, or a failure to have shown the original facts

to the court in the first case, or a change or advance in

scientific doctrine after the first case. Stated more simply,

changed circumstances may lead to a different conclusion,

when a general principle is applied to a specific situation.

II.

REASONABLE CLASSIFICATION

The broad principles of reasonable classification have been

laid down by the Supreme Court over the years and are a

substantial and fundamental part of our constitutional law.

20 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v.

Millic en t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 21

In Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61

(1911), the Court held that a State statute prohibiting a land-

owner from withdrawing an unreasonable amount of mineral

waters from a common underground supply did not deprive

the landowner or his property without due process of law.

The Court also held that the presence in that statute of an

exemption of pumping from wells not penetrating the rock,

where the pumping was done for purposes other than col

lecting and vending carbonic acid gas as a separate com

modity, did not make the statute “arbitrary in its classifica

tion” so as to deny the equal protection of the laws to those

whom it affected (id., 78).

In Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457 (1957), holding that an

Illinois law regulating currency exchanges denied equal pro

tection of the laws because the exception of the money orders

of one company was an unreasonable legislative classification,

the Court quoted with approval from the Lindsley case, supra

(354 U. S. 457, 463-4):

1. The equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment does not take from the State the power to

classify in the adoption of police laws, but admits of the

exercise of a wide scope of discretion in that regard, and

avoids what is done only when it is without any reason

able basis and therefore is purely arbitrary. 2. A classi

fication having some reasonable basis does not offend

against that clause merely because it is not made with

mathematical nicety or because in practice it results in

some inequality. 3. When the classification in such a

law is called in question, if any state of facts reasonably

can be conceived that would sustain it, the existence of

that state of facts at the time the law was enacted must

be assumed. 4. One who assails the classification in

such a law must carry the burden of showing that it does

not rest upon any reasonable basis, but is essentially

arbitrary.’ Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220

U. S. 61, 78-79, 31 S. Ct. 337, 340, 55 L. Ed. 369.”

W illiamson v. L ee Optical o f Oklahoma, Inc., 348 U. S.

483 (1955), upheld, as against the contention that it violated

the equal protection clause, a State statute subjecting opticians

to a regulatory system but exempting from regulation all sellers

of ready-to-wear glasses. That reasonable classifications are

constitutionally valid is plainly implied by the Court’s state

ment (id., 489):

“The prohibition of the Equal Protection Clause

goes no further than the invidious discrimination. We

cannot say that that point has been reached here. For

all this record shows, the ready-to-wear branch of this

business may not loom large in Oklahoma or may present

problems of regulation distinct from the other branch.”

In McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420 (1961), the Court

upheld as a reasonable discrimination a State Sunday-closing

law which allowed only certain retailers to sell specified mer

chandise on Sunday. Dismissing contentions that the statu

tory classifications were without rational and substantial rela

tion to the object of the legislation the Court said (id., 425-6):

“The standards under which this proposition is to be

evaluated have been set forth many times by this Court.

Although no precise formula has been developed, the

Court has held that the Fourteenth Amendment permits

the States a wide scope of discretion in enacting laws

which affect some groups of citizens differently than

others. The constitutional safeguard is offended only if

the classification rests on grounds wholly irrelevant to

the achievement of the State’s objective. State legisla

tures are presumed to have acted within their constitu

22 School D is t . No. 20 & Mark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v .

Millic en t F . B rown, e t al, Appellees 23

tional power despite the fact that, in practice, their laws

result in some inequality. A statutory discrimination will

not be set aside if any state of facts reasonably may be

conceived to justify it. See Kotch v. Board of River Port

Pilot Com’rs., 330 U. S. 552, 67 S. Ct. 910 L. Ed. 1093;

Metropolitan Casualty Ins. Co. of New York v. Brownell,

294 U. S. 580, 55 S. Ct. 538, 79 L. Ed. 1070; Lindsley v.

Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61, 31 S. Ct. 337,

55 L. Ed. 369; Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co. v. Matthews,

174 U. S. 96, 19 S. Ct. 609, 43 L. Ed. 909.”

It is well established that education is primarily a problem

of the individaul states. Barring unconstitutional discrimina

tion, the state has the obligation and the correlative authority

to determine the location of school districts, the level of study,

the scholastic norm, the textual content, the various pedagogi

cal theories which will govern the educational progress, wheth

er education will be compulsory or voluntary, and for what

period, and the amount of money which will be budgeted for

it. See for example, Pyeatte v. Board o f Regents, 102 F. Supp.

407 (W . D. Okla. 1951), affirmed without opinion, 342 U. S.

936 (1952) (supervision of student housing arrangements);

W augh v. Board o f Trustees, 237 U. S. 589 (1915) (prohibi

tion of Greek letter fraternities); W ebb v. State University,

125 F. Supp. 910 (N. D. New York 1954), appeal dismissed,

348 U. S. 867 (1954) (outlawing fraternities and sororities).

The problem of race and color as bases of classification is

illustrated by H ernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 (1954),

which also shows the necessity of ascertaining facts as a

prerequisite for the determination of the question of reason

ableness of classification. Mr. Chief Justice Warren, after

pointing out that race and color may serve as a convenient

index for differentiating between groups, said (id., 478):

“Whether such a group exists within a community is a

question of fact. When the existence of a distinct class

is demonstrated and it is further shown that the laws, as

written or as applied, single out that class for different

treatment not based on some reasonable classification,

the guarantees of the Constitution have been violated.”

Writing two years after the Brown decision, Mr. Justice

Douglas recognized the legal importance of the distinction

between race as such and a racial trait, saying in his book,

W e the Judges, that “regulations based on race may . . . be

justified by reason of the special traits of those races” (p. 398).

Similarly, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, noting

the absence of any relevant criteria for racial separation in

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156 (C.A. 5,

1957), specifically called attention to the lack of evidence of

“any reasonable classification of students according to their

proficiency or health. . . .”

To the same general effect is the statement of the Court in

Bolling v. Sharpe, decided the same day as Brown, where the

Court said, with respect to a classification of children into

separate schools by race in the District of Columbia (347

U. S. 497, 499 [1954]):

“Classifications based solely upon race must be scruti

nized with particular care, since they are contrary to our

traditions and hence constitutionally suspect.”

Clearly a classification which can be “scrutinized with par

ticular care” is not a classification which is invalid per se. In-

tervenors-appellants have no objection to such scrutiny—on the

contrary, it was the District Court’s refusal to scrutinize from

which this appeal is taken.

24 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v .

Millicen t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 25

III.

FACTS vs. LAW AND REASONABLE CLASSIFICATION:

BROWN vs. BOARD OF EDUCATION AND PRESENT

CASE

At the outset, it should be recognized that there is no af

firmative command that schools be integrated in the decision

of the Supreme Court in the Brown case. As recently pointed

out by the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Bell v.

School City o f Gary, Indiana,____ F. 2d____ (C. A. 7, Oct.

31, 1963):

“Plaintiffs are unable to point to any court decision

which has laid down the principle which justifies their

claim that there is an affirmative duty on the Gary School

system to recast or realign school districts or areas for

the purpose of mixing or blending Negroes and whites in

a particular school.

“Plaintiffs argue that Brown v. Board o f Education 347

U. S. 483, proclaims that segregated public education is

incompatible with the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment in a school system maintained pursuant to

state law. However, the holding in Brown was that the

forced segregation of children in public schools solely

on the basis of race, denied the children of the minority

group the equal protection of the laws granted by the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

In Briggs v. Elliott, quoted with approval in the Bell case,

the Court said (132 F. Supp. 776, 777 [E. D. So. Carolina

1955]):

“The Constitution, in other words, does not require

integration. It merely forbids discrimination.”

In summary, the holding of the Supreme Court in Brown

is that an educational classification made solely on the basis

of race or color is invalid under the equal protection clause

as there was no evidence of any educational connection and

“modern psychological knowledge” showed that segregated

schools were inherently unequal since they created a presump

tion of inferiority on the part of the negro and thus caused

him psychological injury.

The Court defined the underlying inquiry thus (347 U. S.

483, 493):

“We come then to the question presented: Does

segregation of children in public schools solely on the

basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other

‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of

the minority group of equal educational opportunities?”

(Emphasis added).

Although it would appear sufficiently clear on its face that

this calls for a conclusion of fact rather than of law, we are

confirmed when we find that Court looking to the testimonial

and other evidence in the records before it and to a “Brandeis”

submission of scientific opinion rather than seeking the answer

to this question in precedent.

From the Kansas record, the Court read (id., 494):

“ ‘ . . . the policy of separating the races is usually in

terpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group.

A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child

to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, there

fore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and

mental development of Negro children and to deprive

them of some of the benefits they would receive in a

racial [ly] integrated school system’.”

26 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , et al, Appellan ts, v.

Millic en t F . B rown, et al, Appellees 27

These are facts, not law. To make these findings the

Kansas District Judge presumably considered evidence—not

cases. Whether negroes in Kansas believed that separate

schooling denoted inferiority, whether a sense of inferiority

affected their motivation to learn, and whether motivation

to learn was increased or diminished by segregation, were

questions requiring evidence for decision. There were as

much subjects for scientific inquiry as the braking distance

required to stop a two-ton truck moving at ten miles an hour

on dry concrete.

When the Court said that the above-quoted finding, in the

Kansas case, of injury through segregation “is amply sup

ported by modern authority” (347 U. S. 483, 494, N. 11), was

the Court making a finding of fact or a ruling of law? On its

face it seems patently absurd to assume that the Supreme

Court was trying to fix for all times the content of modern

psychological knowledge. But it could only be by regarding

that holding as a ruling of law that the judge below in this

case could logically conclude that he was foreclosed from

considering any facts differentiating the present case from

Brown.

It was only after marshalling facts and considering the

statements of “modern authority’ ’that the Court came to the

conclusion that the minor plaintiffs in the Broion case were

injured by segregation and thereby “deprived of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment” (id., 495).

Each of the several courts which have previously con

sidered this question have concluded that the decision in

Brown is based on facts contained in the four case records

before the Supreme Court. Taylor v. Board o f Education of

New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), cert.

28 S chool D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

denied, 368 U. S. 940 (1961); Calhoun v. Board o f Education

o f Atlanta, 188 F. Supp. 401, 409 (N. D. Ga. 1959); Frasier v.

Board o f Trustees o f N. C. Univ., 134 F. Supp. 589, 592

(M . D. N. C. 1955), affirm ed per curiam, 350 U. S. 979 (1956);

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Cty. Bd. o f Ed. 220 F. Supp. 667

(S. D. Ga. 1963). That the factual existence or non-existence

of injury through segregation is the basis on which plaintiffs’

case must be determined is admitted by parapragh 10 of the

complaint [7] which reads in pertinent part:

“Plaintiffs, and the members of the class which they

represent, are injured by the refusal of the defendants

to cease operation of a compulsory biracial school system

in Charleston County. . . . The plaintiffs, and the members

of their class, are injured by the policy of assigning

teachers, principals and other school personnel on the

basis of the race and color of the children attending a

particular school and the race and color of the person

to be assigned.

“The injury which plaintiffs and members of their class

suffer as a result of the operation of a compulsory biracial

school system in Charleston County is irreparable and

shall continue to irreparably injure plaintiffs and their

class until enjoined by this Court.”

These allegations of “injury” are plainly statements of al

leged facts, not conclusions of law. In fact, a complaint con

taining only legal conclusions would fail to satisfy FRCP, Rule

8, which requires:

“. . . (2 ) a short and plain statement of the claim

showing that the pleader is entitled to relief.”

A pleader cannot show that he is “entitled to relief” by

alleging conclusions of law. Polhemus v. American M edical

Millicent* F . B bown , e t al, Appellees 29

Ass’n., 145 F. 2d 357 (C. A. 10, 1944); Padovani v. Bruch-

hausen, 293 F. 2d 546 (C. A. 2, 1961).

In the latter case, the Court stated (293 F. 2d 546, 549):

“Yet if there is any characteristic of the federal rules

(and indeed of code pleading generally) which is well

settled, it is that a plaintiff pleads facts and not law and

that the law is to be applied by the court.”

It is not a reason to change the rule that the facts involved

are of a scientific nature with the social sciences. Fahr, S. M.

and Ojemann, R. H., in “The Use of Social and Behavioral

Science Knowledge in Law,” 48 Iowa L. Rev. 59 (1962), state:

“Social and behavioral scientists and lawyers have long

recognized that the law is concerned with, and is also

in turn very deeply affecting, concepts of behavior and

of society which these sciences are in the process of

investigating. Consequently there have been from time

to time attempts not only to incorporate the attitudes of

science in certain areas but, what is more, to adopt the

findings of scientists. . . . In fact, since law in the end

always deals with human beings, there would seem to be

almost no area in which the influence and the findings of

the social and behavioral sciences might not be used to

explain and improve the law in its daily operation upon

the members of our society.

“Some progress has been made in the acceptance of

this point of view by lawyers. For example, we are

used to seeing the trained social service worker or proba

tion officer in and around the courts. In antitrust actions,

not only the government but also the corporations under

attack employ the factual findings and the arguments of

economics as a major part of their cases. When the

United States Supreme Court reversed a long-standing

position on segregation of the races, it relied in part upon

evidence drawn from areas such as education and sociol

ogy. [Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U. S. 294 (1955);

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U. S. 483 (1954]. Many

other examples could be cited to show that in fact there

has been considerable acceptance of the techniques and

conclusions of all the areas of inquiry we group under the

heading of Social and Behavioral Science.”

As to the necessity for evaluating carefully the qualifications

of scientific witnesses and the validity of their testimony, the

same article states ( id., 64-5):

“The foregoing examples (many others could be cited)

represent very familiar situations in which the court

draws upon social or behavioral science ‘findings’ to help

it reach a conclusion. It is significant that almost never

does a court inquire into the social science orientation

of witnesses in such cases; to most courts a psychologist

is a psychologist, a doctor is a doctor, a social service

worker is a social service worker.

“In very few cases is any attempt made to show from

what sector of the science ‘knowledge spectrum’ the evi

dence given derives, whether from near the hypotheti

cal or from the ‘proved’ end, and such evidence is rarely

attacked in court as representing only one school of any

given social science body of opinion. Very often lawyers,

though suspicious of the validity of the testimony they

hear from social or behavioral scientists, are completely

unaware of the internecine battles and bitter disagree

ments currently raging in these areas. This uncritical

attitude among lawyers is surprising; years ago Wigmore

warned his profession to watch the findings of science

30 School D ist . No. 20 & Mahk Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

M illic en t F . B rown, e t al, Appellees 31

and not to take action in reliance upon scientific evidence

till the findings of that science produced results of good

probability.

It is precisely this failure of lawyers to be properly

skeptical and scientists to be properly scientific which

leads to unsatisfactory results in so many cases where

such evidence is received/’**

Similarly a recent report of a special committee of the

American Association for the Advancement of Science while

arguing that the relative educability of white and negro stu

dents is legally “irrelevant” to the issue of school segregation

(“Science and the Race Problem,” in Science, November 1,

1963, p. 558), nevertheless recognizes the factual nature of

such an inquiry ( id., 558):

“These allegations confront the scientific community

with an unavoidable challenge, for in our view all scien

tists bear a responsibility toward the proper social ap

plication of scientific knowledge and have the duty to

resist the corrosive effects of social and political pres

sures on the integrity of science. It is essential, therefore,

that we determine whether these claims are valid, and,

whether valid or not, what their significance is to the

scientific community and to the public.”

That factual issues are necessarily involved in the solution

of the school problem is similarly indicated in Myrdal, An

American Dilemma, which was cited with approval by the

Supreme Court in the Brown case (347 U. S. 483, 495, n. 11),

“Contrast the statement of Dr. Alfred H. Kelly of Wayne State University,

assistant to plaintiffs’ counsel in B ro w n : “It is not that we were engaged in

formulating lies; there was nothing as crude and naive as that. But we were

using facts, emphasizing facts, bearing down on facts, sliding off facts,

quietly ignoring facts, and above all interpreting facts in a way to do what

[Thurgood] Marshall said we had to do—‘get by those boys down there.’ ”

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education, supra, at 680.

32 S c h o o l D i s t . N o . 20 & M a r k A l l e n , e t a l , A p p e l l a n t s , t>.

and is also cited in “Science and The Race Problem,” supra.

In discussing the differences between white and negro per

sons Myrdal states that (p. 147):

“Present evidence seems, therefore, to make it highly

improbable that innate differences exist which are as large

as is popularly assumed and as was assumed even by

scholars a few decades ago.”

The uncontroverted evidence in the instant case supplies

the evidence that these differences are far larger than Myrdal

predicted. The evidence in the case shows that three major

differences exist between the average white and negro child

which directly control the efficacy of any educational program

to which they are subjected:

First, at any given time there is a difference in mental

age, sometimes referred to as mental maturity or psycho

metric intelligence and measured by a figure known as

I.Q. This difference ranges from half a year on entering

first grade to three and a half years in the twelfth grade.

Second, the growth rates of learing ability also differ

as indicated, approximately a lag of one year for every

four.

Third, the two groups differ sharply in the type of

subject and type of teaching to which they respond most

readily. The widest differences occur in mathematical

abstraction and reading comprehension, while the smallest

differences occur in subjects more largely based on

memorization.

These three differences are found not only in Charleston but

in all cities of the country regardless of either separate or

intermixed schooling and without significant variation by rea

son of the social background of the children.

Millicent* F . B rown, et al, Appellees 33

Laws do not effect changes in such basic differences. The

Court of Appeals of New York in People v. Gallagher, 93

N. Y. 438, 448 (1883), in discussing legislation concerning the

lack of social equality between the races, said:

. . this end can neither be accomplished nor pro

moted by laws which conflict with the general sentiment

of the community upon whom they are designed to op

erate. When the government, therefore, has secured to

each of its citizens equal rights before the law and equal

opportunities for improvement and progress, it has ac

complished the end for which it is organized and per

formed all of the functions respecting social advantages

with which it is endowed.”

If the facts given in evidence in the Court below are true—

and on this record there is neither rebuttal nor avoidance-

then the maintenance of a dual school system in order to

provide optimum educational opportunities for both white and

negro children in Charleston, South Carolina, constitutes a

reasonable classification. Both before and since the Brown

case, the Supreme Court has upheld reasonable classifications

under State law as against contentions that such classifications

violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ( see cases cited in II above). That the legally relevant

characteristics are also common to a group usually referred to

as a “race” does not make them any the less pertinent or alter

settled rules of constitutional construction.

In conclusion, it is submitted that an unassailable factual

basis exists for distinguishing between the two identifiable

racial groups for educational purposes, and that the separation

of schools in Charleston is a reasonable classification for educa

tional purposes where the schools are, as the evidence showed,

specially adapted to the characteristics of each student group

in order to afford “equal educational opportunities.”

IV.

NEITHER RES JUDICATA NOR STARE DECISIS

FORECLOSES CONSIDERATION OF THIS EVIDENCE

The Court below stated that its decision in this regard was

compelled by the principle of stare decisis. Neither the prin

ciple nor its correlative rule of res judicata are in point. The

principle of res judicata does not apply because intervenors

were not parties to, or members of, any class represented by

defendants in Brown v. Board o f Education.

As to parties and privies, the final decision in Brown v.

Board o f Education , 347 U. S. 485 (1954), is a conclusive

adjudication of all questions, both of law and of fact, which

were determined by the Supreme Court. Kessler v. Eldred,

206 U. S. 285 (1907); Hart Steel v. Railroad Supply Co., 244

U. S. 294 (1917); Hale v. Finch, 104 U. S. 261 (1881); Hans-

herry et al., v. L ee , 311 U. S. 32 (1940); Kean v. Hurley, 179

F. 2d 888 (C. A. 8, 1950); 28 USCA Rule 65 (d ).

In Hansberry v. L ee , the Supreme Court recognized the

“principle of general application in Anglo-American jurisprud

ence that one is not bound by a judgment in personam in a

litigation in which he is not designated as a party or to which

he has not been made a party by service of process” (311

U. S. 32, 40). As to whether the principle is changed because

Brown was a class suit, the Court in Hansberry further stated

(id., 41):

“To these general rules, there is a recognized exception

that, to an extent not precisely defined by judicial opinion,

the judgment in a class’ or ‘representative’ suit, to which

some members of the class are parties, may bind mem

bers of the class or those represented who were not made

parties to it.”

34 School D ist . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v.

Millic en t F . B rown, e t al, Appellees 35

However, for one to be bound in a “class” suit, “adequate

representation” is an absolute essential. On that point, Mr.

Justice Stone continued (id., 42-3):

“It is familiar doctrine of the federal courts that mem

bers of a class not present as parties to the litigation may

be bound by the judgment where they are in fact ade

quately represented by the parties who are present, or

where they actually participate in the conduct of the

litigation in which members of the class are present as

parties . . . or where the interest of the members of the

class, some of whom are present as parties, is joint, or

where for any other reason the relationship between the

parties present and those who are absent is such as legally

to entitle the former to stand in judgment for the latter.”

Since intervenors were not parties to, or members of any

class represented by defendants in Brown, it follows that

Brown does not bind them under the doctrine of res judicata.

Inasmuch as the central issue of injury occurring through

segregation presents a question of fact, and does not involve

a rule of law, the principle of stare decisis is equally inap

plicable. This principle applies only to conclusions of law in

causes subsequently arising in the same court or inferior courts,

and applies to strangers as well as to privies. 21 C. J. S. 305,

386; 14 Am. Jur. 290.

Under this principle, therefore, this court is bound by the

decision in the Brown case only to the extent that it states

rules of law. Stare decisis could have no application to any

determinations of fact in the Brown case. Since we have shown

that injury through segregation is a question of scientific fact,

the trial Court should have considered the evidence tendered

to rebut plaintiffs’ assertion of such injury. See Frankfurter,

Note, 28 Harv. L. Rev. 790 (1915), supra.

36 School D is t . No. 20 & Mark Allen , e t al, Appellan ts, v .

It is submitted that the Court below erred in believing that

the doctrine of stare decisis precluded it from considering the

evidence that educational and psychological injury would re

sult from forcible interracial congregation in the public schools

of Charleston.

CONCLUSION

Intervenors-appellants pray this Court to reverse and re

mand the case to the District Court with instructions to dis

miss the complaint with prejudice with or without leave to

plaintiffs-appellees to rebut the present uncontroverted show

ing of injury from the plan they propose.

Respectfully submitted,

BURNET R. MAYBANK,

GEORGE STEPHEN LEONARD,

Attorneys for Interveners-Appellants.