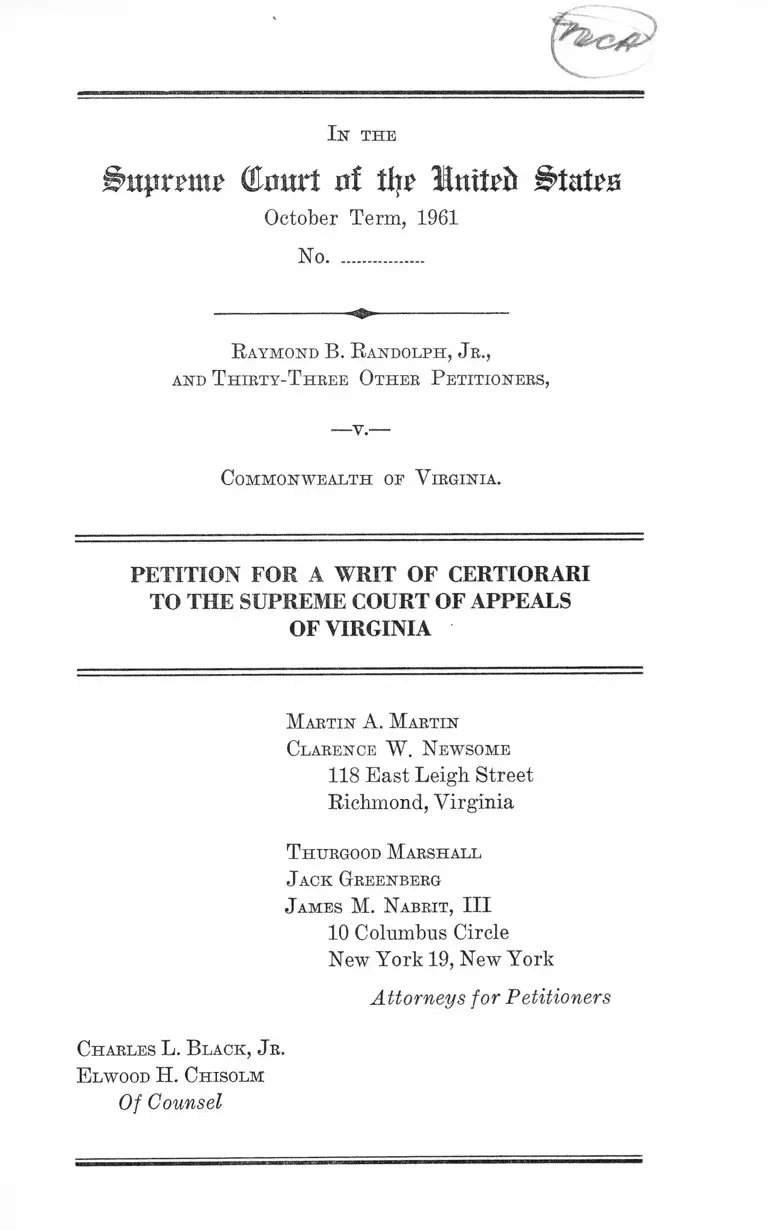

Randolph, Jr. v. Virginia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Randolph, Jr. v. Virginia Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1961. 1bfe32ca-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d28e4d45-60ca-471b-8a52-7a92a2317797/randolph-jr-v-virginia-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme Ghmrt #i tty Jshata

October Term, 1961

No.................

R aymond B. R andolph, Jr.,

and T hirty-T hree Other P etitioners,

Commonwealth oe V irginia.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS

OF VIRGINIA

Martin A. Martin

Clarence W . Newsome

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

T hurgood Marshall

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. B lack, J r.

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ........................................... 2

Jurisdiction ................. 2

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement ........................................................................... 4

How the Federal Questions Are Presented.................... 6

Reasons for Granting the W rit.................... -................. H

I. The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions Of

This Court On Important Issues Affecting Federal

Constitutional Rights ...............................................

A. The arrest and conviction of these petitioners

for disobedience to an order to leave a public

place, motivated by a custom of segregation,

which custom in turn was in part created and

has long been maintained by state law and

policy, constituted state enforcement of racial

discrimination contrary to the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment ........................................................

~p~ B. The decision below conflicts with decisions

of this Court securing the right to freedom

of expression under the Fourteenth Amend

ment .....................................................................

11

C. Petitioners either were convicted without proof

of an element of the crime—their knowledge

or notice of the authority of the persons order

ing them to leave—or if such knowledge or

notice is not an element of the crime, then

they were convicted under a statute which they

could not have known to embody the harsh

and arbitrary rule that one who refuses to

leave a public place at the command of a

stranger does so at his peril. In either case,

standards of the Fourteenth Amendment have

been violated ...................................................... 26

II. The Public Importance Of The Issues Presented .. 29

Conclusion ......................................................................... 32

Appendix ........................................................................... 33

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia.................................................................... 33

Order or Judgment in Randolph.............................. 40

Order or Judgment in Bray ................................... 41

Opinion of Hustings Court ..................................... 42

T able op Cases

Avent v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, 29

U. S. L. Week 3336 .................................................... 30

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531

(5th Cir. 1960) ............................................................ 31

Briggs v. State, Ark. Sup. Ct. (No. 4992) .................. 30

PAGE

I ll

Briscoe v. Louisiana, cert, granted, 29 U. S. L. Week

3276 ................................... 30

Briscoe v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 432 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) ............................................................................. 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .............16,17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) ...................... 13

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F. 2d 879 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied 341 U. S. 941 (1951) .................................... 18

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 .................... . 13,. 14,15, 20

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 27

Crossley v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 339 (Tex. Crim. App.

1961) ............................................................................. 30

Dept, of Conservation & Development v. Tate, 231 F.

2d 615 (4th Cir.), cert, denied 352 IJ. S. 838 (1956) 18

Drews v. State, 167 A. 2d 341. (Md. 1961), jurisdictional

statement filed, 29 U. S. L. Week 3286 ...................... 30

DuBose v. City of Montgomery, 127 So. 2d 845 (Ala.

App. 1961) ..................... 30

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 ...... ........................... 25

Fox v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, 29 IT. S. L.

Week 3336 ..... 30

PAGE

Garner v. Louisiana, cert, granted, 29 IT. S. L. Week

3276 ............................................................................... 30

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ..................................... 17

Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339

IT. S. 605 ......................... 14

Griffin v. State (Md. Ct. App. No. 248, decided June 8,

1961) ............................................................................. 30

Henderson v. Commonwealth, 49 Ya. (8 Grat) 708 (Va.

Gen. Ct. 1852) ........................................... .................... 28

iy

Henry v. Commonwealth, writ of error denied, April 25,

PAGE

1961 (N o .------ ) _______ __________ ___________ ___ 31

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879....................... . 17

Hopkins v. City of Richmond, 117 Va. 692, 86 S. E. 139

(1915) ......... ............................. ......................... - ......... 16

Hoston v. Louisiana, cert, granted, 29 U. S. L. Week

3276 ............................................ ....... ..... ................... 30

Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U. 8. 349,

52 L. Ed. 828 (1908) .................................................... 12

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (D. C. E. D. Va.

1959) ................. .................... ....... ........... ..................16, 18

Johnson v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) ................................ ............................................ 30

King v. City of Montgomery, 128 So. 2d 340 (Ala. App.

1961) ..................................... .............- .... .................... 30

King v. State, 119 S. E. 2d 77 (Ga. 1961) ...................... 30

Lambert v. California, 355 U. S. 225 ......... .................... 27

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 H. S. 451 .............. ........... 27

Lupper v. State, Ark. Sup. Ct. (No. 4997) .................... 30

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501..................................... 13, 21

Martin v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 233 (Ga. App. 1961) ....... 30

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141................................. 21

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 H. S. 373 ................ ................. 17

Morissette v. U. S., 342 U. S. 246 ..............................27, 28

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113 ....................................... 13

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (D. C. E. D. Va.

1958), vacated on other grounds, 360 U. S. 167----- 16

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D.

Va, 1949) ..................................................................... 18

y

New Orleans City Park Improvement Association v.

Detiege, 358 U. S. 5 4 ................................................ - 17

Eeid v. City of Norfolk, 179 F. Supp. 768 (E. D. Va.

1960) ....................................................................... -.... 18

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 U. S. 793.... 21

Rex v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698 ................... ........................... 28

Rucker v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960) ................. 30

Rucker v. State, 342 S. W. 2d 325 (Tex. Crim. App.

1961) ............................................................................. 30

Samuels v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 231 (Ga. App. 1961) .... 30

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................—........ -........ 13

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 4 L. ed. (2d) 205 .... 25

Smith v. State (No. 4994), Ark. Sup. Ct........................ 30

State ex rel. Steele v. Stoutamire, 119 So. 2d 792 (Fla.

1960) ............ 30

Steele v. City of Tallahassee, 120 So. 2d 619 (Fla.

1960) ............................................................................. 30

Steele v. City of Tallahassee, cert, denied, 29 U. S. L.

Week 3263 .................................................................... 30

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ........................... 21

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461.......... .............................. 15

Thompson v. Commonwealth, petition for writ of error

filed Ju ly------ , 1961................ .................................... 31

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 IT. S. 199 .......... -----.......... 29

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 88 .................................. 21

Tinsley v. Commonwealth, 202 Va. 707, petition for

cert, filed, July 24, 1961, 30 IT. S. L. Week....... ........ 31

Tucker v. State, 341 S. W. 2d 433 (Tex. Crim. App.

1960)

PAGE

30

VI

Union Paper Bag Machine Co. v. Murphy, 97 U. S.

120 ...................................... -----..................... -----......... 14

United States v. Beaty, 288 F. 2d 653 (6th Cir. 1961) .... 13

Walker v. State, 118 S. E. 2d 284 (Ga. App. 1961) .... 30

Williams v. Howard Johnson Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845

(4th Cir. 1959) ...........— .... -.... -....... -................-.....

Williams v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed,

29 U. S. L. Week 3336 ............................. -----..... - 30

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183 ............................. 25

Statutes

Louisiana Acts, 1960, Nos. 70, 77, 80 .............— ...... - 31

South Carolina Acts, 1960, No. 743 ...................- ............ 31

Dallas, Texas, 1960 Ordinance (6 Race Rel. L. Rep.

317) ............................................................................... 31

Constitution of Virginia, §140............. .......... ................ 19

Code of Virginia, 1950, §18-225 ................................. 3, 28, 29

Code of Virginia, 1950, §§18-327, 18-328 (now Code of

Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, 18.1-356, 18.1-

357) ........................................ -........... -.................... -15,18

Code of Virginia, 1950, §20-54 .......................-................ 19

Code of Virginia, 1950, §22-221 ..................................... 19

Code of Virginia, 1960 Supp., §37-183 .......... -.............. 19

Code of Virginia, 1953 Replacement Volume, §38.1-597 19

Code of Virginia, 1958 Replacement Volume, §53-42 .... 19

Code of Virginia, 1959 Replacement Volume, §56-196 .... 19

Code of Virginia, 1959 Replacement Volume, §56-326 - . 19

Virginia Acts, 1960, ch. 97 ...................—........................ 31

28 U. S. C., §1257(3) ........................................................ 2,8

PAGE

Oxheb A uthorities

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tentative

Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment................................. 28

Citizens in Protest: A comment on the Student Demon

strations of 1960, 6 How. L. J. 187 (1960) .............. 29

Foster, Race Relations in the South, 1960, 30 J. Negro

Ed. 138 (1961) ............................................................ 29

Hand, The Bill of R ights................................................ 14

House Joint Resolution No. 97, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

589 ................................................................................. 16

Opinion Letter, Feb. 14, 1956, Attorney General J.

Lindsay Almond, Jr. to Hon. Robert Whitehead, 1

Race Rel. L. Rep. 462 .................................................. 16

Opinion of the State Attorney General to the Common

wealth Attorney of Arlington County, Oct. 16, 1956,

1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1156 (1956) ................................. 16

Opinion of the State Attorney General to the Common

wealth Attorney of the City of Roanoke, Aug. 24,

1960, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1282 (1960) ...................... 19

Pollitt, Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal

Problems of First Sixty Days, 1960 Duke L. J.

315 ......................................................................... 13,25,29

Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Rev.

55 (1933) ....................................................................... 28

Senate Joint Resolution, No. 3, Feb. 1, 1956 ................ 16

Southern School News, April 1956, p. 1 3 ..................... 16

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955) - 19

Vll

PAGE

In the

(tart af tlp> Hutted States

October Term, 1961

No.................

R aymond B. R andolph, Jr.,

and T hirty-T hree Other P etitioners,

Commonwealth op V irginia.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioners (Raymond B. Randolph, Jr., Leroy M. Bray,

Jr., Gordon Coleman, Gloria Collins, Robert B. Dalton,

Joseph E. Ellison, Jr., Marise Ellison, Wendell T. Foster,

Jr., A. Franklin, Donald Goode, Woodrow Grant, Albert

Van Graves, Jr., George Wendell Harris, Jr., Yvonne Hick

man, Joana Hinton, Carolyn Horne, Richard C. Jackson, Jr.,

Elizabeth Johnson, Ford T. Johnson, Jr., Milton Johnson,

Celia E. Jones, Clarence A. Jones, Jr., John Jones McCall,

Frank G. Pinkston, Larry Pridgen, Ceotis L. Pryor, Samuel

Shaw, Charles M. Sherrod, Virginia Simms, Ronald Smith,

Barbara Thornton, Randolph Allen Tobias, Patricia Wash

ington, and Lois B. White) pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgments of the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virgina, entered in the above-entitled cases on

April 24,1961.

2

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion and judgment or order of the Supreme Court

of Appeals of Virginia in the case styled Randolph v. Com

monwealth is reported at 202 Va. 661, 119 S. E. 2d 817,

and it is set forth in the appendix hereto, infra, pp. 33-39, 40

The thirty-three identical judgments or orders of the Su

preme Court of Appeals, denying writs of error and super

sedeas in the other cases “ for the reasons stated in the

[Randolph] case” are not reported; however, one of these

judgments or orders is set forth in the appendix hereto,

infra, p. 41.

The verbatim opinion filed by the Hustings Court of

the City of Richmond in each of the thirty-four eases (see,

e.g., R. Randolph 11-14) is not reported; but it is also

set forth in the appendix hereto, infra, pp. 42-45.

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia were entered on April 24, 1961. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C., §1257(3), peti

tioners having claimed and been denied rights, privileges,

and immunities under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Petitioners, Negro students, peacefully sought food

service at lunch counters located in a public establishment

wdiich welcomed their presence and trade except at these

lunch counters. They were ordered to leave the premises,

and upon their refusal were arrested, tried and convicted

under a statute making it a crime to “ . . . remain upon the

3

lands or premises of another, after having been forbidden

to do so by the owner, lessee, custodian, or other person

lawfully in charge of such land. . . . ” Under the circum

stances, were the petitioners deprived of rights protected

by the:

1. equal protection and due process clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment, in that their arrest and convictions

implemented a state custom, long supported and fostered

by state law, of racial segregation in public places;

2. due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as

that clause embodies the guarantee of free expression, in

that their arrest and conviction in the circumstances of this

case constituted an abridgement of the freedom of ex

pression;

3. due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

in that they were convicted on records barren of evidence

of an element of guilt, viz., notice to them of the authority

of the person ordering them out;

4. (in the alternative to 3) due process clause, in that

they were convicted under a statute which gave no adequate

warning of the harsh and irrational rule that one must

leave a public place at the command of an unidentified

stranger?

Statutory and Constitutional

Provisions Involved

1. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States.

2. Section 18-225 of the Virginia Code of 1950, as

amended, reading as follows:

4

If any person shall without authority of law go upon

or remain upon the lands or premises of another, after

having been forbidden to do so by the owner, lessee,

custodian or other person lawfully in charge of such

land, or after having been forbidden to do so by sign

or signs posted on the premises at a place or places

where they may be reasonably seen, he shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof

shall be punished by a fine of not more than One Hun

dred Dollars or by confinement in jail not exceeding

thirty days, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

Statement

These thirty-four cases, all decided on the same day

(April 24, 1961) and on the same grounds by the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia, arose out of the same course

of events, occurring in the early afternoon of February 22,

1960, at Thalhimer’s Department Store in the City of Rich

mond. Petitioners were tried and convicted in the Police

Court of the City of Richmond, all before the same judge

and with the same prosecutor and defense counsel, between

March 4 and March 22, 1960. On appeal to the Hustings

Court of the City of Richmond, these cases were retried, per

stipulation, on the records made in the Police Court (see

Appendix, infra, pp. 33, 43) and all petitioners were found

guilty in thirty-four verbatim opinions filed by the Hust

ings Court of May 26, 1960 (Appendix, infra, pp. 42-45).

All the cases were taken to the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia on applications for writ of error and super

sedeas, which court delivered an opinion only in the case

styled Randolph v. Virginia (Appendix, infra, pp. 33-39)

and decided each of the other cases on the basis of that

opinion by specific reference thereto (see, e.g., Appendix

infra, p. 41).

5

These cases have thus received a unitary treatment in

the judicial system of Virginia. In this petition, reference

will be made to the Records by name of the particular

defendant. The Records are substantially identical in

all parts other than the transcripts of testimony.

On February 22, 1960, petitioners, Negro students, en

tered Thalhimer’s Department Store, to which they were

invited as members of the public. While there, they at

tempted to obtain service at eating facilities reserved for

white patrons—two lunch counters, a soup bar, and a

restaurant. There is a lunch counter for Negroes in the

basement. All petitioners were refused service at the facili

ties reserved for whites, “because they were Negroes.” (R.

Randoph 26, stipulation repeated verbatim in each other

record.)

Each of the petitioners was then ordered to leave the

store by a person who later turned out to be an official of

the store. There is no hint, testimonial or inferential, that

this order was motivated by any ground other than the

one suggested by the circumstances—that petitioners were

ordered to leave because they sought unsegregated service.

There is nothing to suggest that petitioners, or any of them,

were for any reason or for no reason personally obnoxious

to Thalhimer’s, Inc., or to any official thereof.

These records do not show with any clarity that peti

tioners, or any of them, had notice of the authority of the

persons ordering them to leave. In some of the records

that possibility is rebutted with particular clarity. For

example, in the ease of Robert B. Dalton, the store employee

who issued the order, testified that he was a stranger to

Dalton and that he did not notify Dalton in any way either

of his identity or of his authority (R. Dalton 10-11).

Upon their refusal to leave, petitioners were taken before

a Magistrate sitting in the store (R. Pinkston 7) and war

6

rants sworn for their arrest. They were tried and con

victed in Police Court, and fined twenty dollars each; these

convictions, as stated above, were in effect affirmed in

de novo trials, on the Police Court transcripts, in the

Hustings Court. The Supreme Court of Appeals affirmed

the Randolph conviction and rejected the other petitions

for writ of error, which had the effect of affirming the

judgments.

How the Federal Questions Are Presented

The federal questions which petitioners seek to have

this Court review were raised in the court of first impres

sion, the Police Court of the City of Richmond, by timely

motions to dismiss and to strike the evidence in each case

on the following grounds (see, e.g., R. Randolph 22-23):

A conviction under this warrant and the evidence

presented would:

1. Violate the right of this defendant of freedom of

assembly under State law and the United States Con

stitution.

2. Violate the right of this defendant of freedom of

speech and of association under State law and the

United States Constitution.

3. Deny this defendant due process of law in that

he was arrested and prosecuted under a State law

and deprived of his liberty and ejected from a public

place solely on account of his race and color.

4. Violate the rights of this defendant under the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution by being singled out for

ejection and arrested by reason of his race and color.

7

5. Deny him due process of law by making it a

crime for him to obey a private rule or regulation and

the statute, even if constitutional on its face, is being

unconstitutionally applied.

6. Make it a crime, at the whim of a private per

son, for the defendant to be on property upon which

the general public has a right to be, and thereby denies

him due process and the equal protection of the law,

regardless of race.

7. Authorize and permit private persons to dis

criminate against this defendant on account of race,

and when such discrimination is enforced by the con

viction of this defendant by the State would constitute

a denial of the equal protection of the laws and due

process of law guaranteed by the United States Con

stitution.

8. Deny this defendant the equal protection of the

laws since, after having been invited into the store,

he was then ordered out and discriminated against by

the store on account of his race, and when, as in this

case, such discrimination is enforced by State legal

process.

9. Violate defendant’s common law and statutory

right not to be excluded from the common market.

The Police Court overruled the motion in each case (see,

e.g., R. Randolph 25) and petitioners were each found

guilty and fined $20.00 (Id.).

Thereafter, on appeal of these thirty-four cases to the

Hustings Court of the City of Richmond (Appendix, infra,

p. 43), the State and each defendant stipulated and agreed

that the following was to be read in conjunction with the

reporter’s transcript of the hearing in the Police Court

of the City of Richmond (R. Randolph 26) :

8

5. That all motions and objections made in any of

the other 33 cases shall be considered by the court

as having been made in this case and the rulings on

such motions and objections shall be considered as

having been made in this case.

The constitutional issues preserved by this stipulation were

briefed and argued (Appendix, infra, p. 43); and, after

review and consideration thereof, the Hustings Court held

“ that no constitutional rights of the defendants have been

violated” (Appendix, infra, p. 45), and “ that the failure

of the defendants to leave the premises when requested by

an official of Thalhimer’s constituted trespass under Section

18-225 of the Code of Virginia” (Id.).

Thereupon petitioners sought, and the Hustings Court

granted, a stay of execution of the sentence in order that

they might apply to the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia for a writ of error and supersedeas (R. Randolph

8, 9, 10). Each such application for a writ of error and

supersedeas made the following assignments of error (see,

e.g., R. Randolph 15-17) :

1. The Court erred in refusing to strike the evidence

and dismiss this cause on the ground that the statute,

as applied, abridges the right of the defendant to free

dom of assembly under the First Amendment, as im

plemented by the Fourteenth Amendment, to the Con

stitution of the United States.

2. The Court erred in refusing to strike the evidence

and dismiss this action on the ground that the statute,

as applied, violates the rights of this defendant to free

dom of speech and of association under the Constitution

of the State of Virginia and the First Amendment, as

implemented by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

9

3. The Court erred in convicting this defendant of

trespass since there is no evidence that the defendant

knew that he was trespassing upon the property of

Thalhimer’s Store.

4. The Court erred in convicting this defendant of

trespass, contrary to the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and contrary to the law’s of the State

of Virginia which recognize that a conviction of tres

pass may not be obtained against one on the premises

under a claim of property right, since he was upon the

premises in question under a claim of constitutional

right.

5. The Court erred in convicting this defendant since

there was no evidence to show that this defendant

had any knowledge of the policy of Thalhimer’s Store

not to serve this defendant or persons of his race and

color, and no reason was given this defendant as to why

he was trespassing either at the lunch counter or in the

store, nor did the employee of the store identify himself

as such, nor did this defendant know of the official

capacity of the employee, nor the reason for the de

mand to leave, thereby denying this defendant due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws

contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

6. This defendant was denied due process of law

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States by being convicted of a

crime for having disobeyed the order to leave the prem

ises of one allegedly in possession, without requiring

that such person establish his identity or authority for

making the demand and when no proof of this identity

or authority was presented at the time of the demand.

10

7. This defendant was denied dne process of law

contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States in that he was arrested, prose

cuted and convicted under a state law which deprived

him of his liberty and authorized his ejection from a

public place, solely on account of his race and color.

8. The statute, as applied, violated the rights of this

defendant under the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States by his being singled out for ejection

and arrest by reason of his race and color.

9. The statute, as applied, denied this defendant

due process of law by making it a crime for him to dis

obey a rule or regulation of a private person, when

the State enforced such rule by establishing magis

trate’s office in the store and arresting defendant.

10. The statute, as applied, denied this defendant

due process and the equal protection of the laws guar

anteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, in that it authorized or re

quired the conviction of this defendant of a crime for

failing or refusing to obey an order of a private per

son, based solely upon the race or color of the de

fendant.

11. This defendant was denied the equal protection

of the laws guaranteed to him under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

when, after having been invited into the store, he was

then ordered out and discriminated against by the store

on account of his race and color, and when the State

enforced such discrimination by the arrest and con

viction of this defendant.

1 1

12. The statute, as applied, violates the common

law and statutory right of this defendant not to be

excluded from the common market.

The Supreme Court of Appeals disposed of these conten

tions adversely to petitioners in its opinion and order filed

in the Randolph case (Appendix, infra, pp. 34, 36, 37, 38, 39,

40) and the orders entered in conformity therewith in the

other thirty-three cases.1

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I

The Decision Below Conflicts With Decisions of This

Court on Important Issues Affecting Federal Constitu

tional Rights.

A. The arrest and conviction of these petitioners for

disobedience to an order to leave a public place,

motivated by a custom of segregation, which cus

tom in turn was in part created and has long been

maintained by state law and policy, constituted

state enforcement of racial discrimination contrary

to the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

These petitioners were tried and convicted for viola

tion of a statute which makes it a crime not to get off

private property when ordered to do so by the owner or by

1 R. Bray 15; R. Coleman 25; R. Collins 11; R. Dalton 21; R.

Ellison (J.E.) 25; R. Ellison (M.) 36; R. Foster 11; R. Franklin

21; R. Goode 11; R. Grant 18; R. Graves 19; R. Harris 17; R.

Hickman 12; R. Hinton 12; R. Horne 22; R. Jackson 11; R.

Johnson (E.) 23; R. Johnson (F.T.) 17; R. Johnson (M.) 30;

R. Jones (C.E.) 12; R. Jones (C.A.) 33; R. McCall 21; R. Pinkston

30; R. Pridgen 19; R. Pryor 33; R. Shaw 12; R. Sherrod 47; R.

Simms 23; R. Smith 22; R. Thornton 13; R. Tobias 12; R. Wash

ington 12; R. White 12.

12

someone acting for him. There could be no question of

either the constitutionality or the desirability of such a

statute, in its normal functioning as a basic sanction for

the protection of private property. A man ought to have

a right to order from his home anybody he prefers not to

have there, and to have the help of the law in making the

order effective. But Thalhimer’s, a public commercial

establishment to which petitioners were invited, is the

home of no one, and Thalhimer’s, Inc. was not in this case

exercising a mere “personal” choice but has invoked state

power to help it obey the force of massive custom, which in

its turn has been long supported by state law and policy.

The “property” interest of Thalhimer’s Inc. is an exceed

ingly narrow one, for these petitioners, with the general

public, were not so much “ invited” as besought to come into

Thalhimer’s, so long as they abstained from the single

forbidden fruit of equal treatment in a few restaurants;

the “property” right actually at stake is the specific right

to segregate, and no other. The cases were tried and af

firmed on the theory that these sweeping differences in fact

can make no difference in result—that the right to choose

those who come or stay on one’s property is (through the

whole range of motivation, through the whole range of pub

lic connection and effect, through the whole range of prop

erty classified for other purposes as “ private” ) an absolute,

yielding to no competing considerations. Property rights

are rarely if ever quite that absolute;2 in this case the right

of private property collides with the Fourteenth Amend

2 As Mr. Justice Holmes pointed out in Hudson County Water

Co. v. McCarter, 209 U.S. 349, 52 L.Ed. 828 (1908) : “ All rights

tend to declare themselves absolute to their logical extreme. Yet

all in fact are limited by the neighborhood of principles of policy

which are other than those on which the particular right is founded,

and which become strong enough to hold their own when a certain

point is reached.” Id. at 356, 56 L.Ed. at 832.

13

ment right not to be subjected to public racial discrimina

tion. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; V. S. v. Beaty, 288

F. 2d 653 (6th Cir. 1961).

Thalhimer’s property is open to the public, including

Negroes. As a great department store, Thalhimer’s is a

part of the public life of the community. In choosing to ex

clude Negroes from some of its restaurants, and to expel

from the store all who protest against this humiliation,

Thalhimer’s followed a policy of public racial discrimina

tion. It was in support of this policy of public racial dis

crimination that the public force was invoked, in the shape

of police intervention and these convictions. The assimila

tion of this situation to the broadly dissimilar one of the

householder who orders an unwelcome intruder to leave is

not the product of skill in generalizing, but rather the re

sult of refusal to have regard to clearly significant distinc

tions where these leap to the eye. Only doctrinal clumsiness

could force the law to treat alike two things so utterly dif

ferent.

Our doctrine is not that clumsy. Quite aside from the

obvious amenability of “private” property rights to many

limitations in the public interest, Mnnn v. Illinois, 94 U. S.

113,3 even when these limitations root in the Constitution

alone, Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, the action here is

not in any relevant sense purely “private” .

The requirement of “ state action” as a prerequisite to

the invocation of Fourteenth Amendment guarantees has

proven an unreliable and perhaps meaningless guide among

the intricacies of state involvement in activities nominally

“ private” . The Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, from which

3 See also, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 74 (1917); Pollitt,

Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal Problems of First

Sixty Days, 1960 Duke L.J. 315, 358-9.

14

the requirement stems, laid it down that “ some” state ac

tion supporting the forbidden activity is enough, 109 U. S.

13; since total absence of state involvement, except pos

sibly in cases of common crime, never occurs, the “ state

action” doctrine is fated to become more and more trouble

some as insight deepens into the complexities of state in

volvement.

Nor is it clear that “ state action” , even under the Civil

Rights Cases, must always be “ political” action; “ custom”

is specifically included in the Civil Rights opinion, as one

of the forms of “ state authority” , 109 U. S. 17, and it may

be that behind this is the conception of the “ state” as a

community, imposing its will through “ custom”. It is ques

tionable whether even the verbal requirement of “ state ac

tion” in equal protection cases ever rested on more than a

misunderstanding,4 for the “ denial” of “ protection” seems

to refer even more naturally to state inaction than to state

action.

We have, moreover, lately been reminded by one of our

most illustrious judges, in a solemn constitutional context,

that “ for centuries it has been an accepted canon in inter

pretation of documents to interpolate into the text such

provisions, though not expressed, as are essential to pre

vent the defeat of the venture at hand . . . ” Hand, The Bill

of Rights, p. 14. It may be that this ancient principle

justifies the extension of Fourteenth Amendment protec

tion to “ private” actions which must be prohibited lest the

Amendment fail of its broad purposes. (Something like

this, in the doctrine of “ equivalents” has long aided the

patentee, Union Paper Bag Machine Co. v. Murphy, 97 U. S.

120; Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339

4 See generally Mr. Justice Harlan dissenting in Civil Rights

Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 26-62 (1883).

15

U. S. 605; Fourteenth Amendment rights of full member

ship in the community call for no less favorable treat

ment. Cf. Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461.)

But in the present case the involvement of the State of

Virginia as a whole entity is so intimate and manifold

that we need not reach these ultimate problems. As a com

munity and as a polity, Virginia had its hands in the oc

currences at Thalhimer’s to an extent sufficient to satisfy

any reasonable “ state action” standard.

The intervention of the police in cooperation with the

Thalhimer management, the sitting of the magistrate actu

ally in the store (R. Pinkston 7-8), the invocation of the

whole machinery of arrest and prosecution—these are the

immediate and overt state interventions. “ Whether the

statute book of the State actually laid down any such rule

. . . , the State, through its officer, enforced such a rule;

. . . ” Civil Rights Cases, supra, 109 U. S. at 15.

But the deeper involvement of the State arises from two

facts: 1) Thalhimer’s, in excluding Negroes, was not acting

capriciously, or in obedience to the personal whims of those

in control, or in conformity with their desires as to asso

ciation, but was following a custom which is deeply char

acteristic of the State of Virginia as a community; 2) this

custom, in turn, has been firmed up and supported by a

policy which is the cornerstone policy of the State of Vir

ginia as a political body, and which has received expres

sion in its laws5 and other official utterances6—the policy

5 Code of Virginia, 1950, §§18-327 and 18-328 (now Code of

Virginia, 1960 Replacement Volume, §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357)

requires segregation in all places of public entertainment or as

semblage. Some other statutes requiring segregation in other areas

of public life are cited infra, p. 19.

6 As long ago as 1915, the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

stated that it was “ the declared policy of this state that association

16

of segregating Negroes in public life. The refusal to see in

this pattern a sufficient involvement of the State to support

the application of the equal protection clause could arise

only from a supposed obligation to swallow wdiole the

formalities of “ private” property, and “private” action,

where the action is in its roots as public, as deeply com

munal, as action ever can be.

Although the Commonwealth attorney was repeatedly

upheld by the Police Court judge in objections to explora

tion of the motives of Thalhimer’s officials on this occasion,

the only rational or even imaginable ground Thalhimer’s,

Inc. could have had for its actions on February 22, 1960

must be that of obedience to Virginia custom. Deference

to the prejudices of white patrons, or fear of disorder, are

merely alternative ways of referring to different aspects

of this custom. Petitioners were refused service because

they were Negroes, were ordered from the store, refused

to leave, and were arrested. It is hard to imagine evidence

of the races tends to breach of the peace, unsanitary conditions,

discomfort, immorality and disquiet.” Hopkins v. City of Rich

mond, 117 Va. 692, 86 S.E. 139, 145. The League of Women Voters

was told by State Attorney General Almond that it had a duty

to segregate the races at a meeting of voters. Opinion of the

State Attorney General to the Commonwealth Attorney of Arling

ton County, October 16, 1956, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1156 (1956).

The response of the Virginia Legislature to this Court’s decision

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, was the adoption

of a resolution of “ interposition” , Senate Joint Resolution No. 3,

Peb. 1, 1956; see also, Opinion Letter, Feb. 14, 1956, Attorney

General J. Lindsay Almond, Jr., to Honorable Robert Whitehead,

1 Race Relations Law Reporter 462. Other utterances are referred

to in James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331, 333-334 (D.C. E.D. Va.

1959). See also NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp., 503, 513-515

(D.C. E.D. Va. 1958), vacated on other grounds 360 U.S. 167. In

1956 The Virginia House of Delegates and Senate adopted House

Joint Resolution No. 97, declaring that “ . . . The long established

policy of this Commonwealth has been to provide for the separation

of the races . . . ” and that “ . . . this wise policy should be pre

served by all the legal means at our command . . . ” 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 589; Southern School News, April 1956, p. 13.

17

which could rebut the inference, from these facts, that their

arrest was the direct consequence of Thalhirner’s election

to bow to the custom of segregation, and not a scintilla of

such rebutting evidence appears.

No “ right not to associate” can here be asserted on

Thalhimer’s behalf, even if a corporation can have such

an interest, for the employees who made the decision were

acting in an official rather than a personal capacity, and

had nothing personal at stake. The President of Thal

himer’s Inc. testified to his own utter detachment from the

whole situation (R. Sherrod 37-8). The only “ right not to

associate” being protected was that of the white patrons

of Thalhimer’s Inc., but (aside from the fact that they had

no voice in the matter) this is only another way of saying

that Thalhimer’s Inc. acted in obedience to the public cus

tom of public segregation that prevails in Virginia, and

to nothing else.

The State of Virginia as a community was thus inextri

cably involved in these events. But the State of Virginia as

a political body was also involved, because the custom of

public segregation is one to which the State has given

(and continues to give) the massive support of all its

political institutions. The “ custom” of segregation is not

a “ custom” simpliciter, but a custom which has been, if

not the chief end of Virginia’s policy, one of its absolutely

prime objectives.7

It is true that most of the official support given by

Virginia to segregation is now, formally at least, nullified

by the decisions of this Court.8 (The segregation laws as

7 See note 6, supra.

8E.g., Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373; Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483; New Orleans City Park Improvement

Association v. Detiege, 358 U.S. 54; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S.

903; Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U.S. 879.

18

to public places were, however, still being enforced de facto

in Virginia at about the time these petitioners were ar

rested. See, e.g., Reid v. City of Norfolk, 179 F. Supp. 768

(E. D. Va. I960).) But a factual causal nexus is not so

easily broken. If, for decades, the State of Virginia has

fostered and enforced the separation of the races, that

separation, as it exists today in custom, cannot be said to

have no causal relation to the action of the State, merely

because, much against its officially declared will,9 the State

may no longer lawfully enforce segregation laws under

that name.10 A house remains the product of its builder,

even if he is forbidden to keep it in repair. And Virginia,

as a political entity, built the custom of segregation.

It is, to be sure, doubtful whether segregation in restau

rants was formally required by the Virginia law concern

ing segregation in places of public assembly (Code of Vir

ginia, 1950 §§18-327 and 18-328, now Code of Virginia, 1960

Replacement Volume, §§18.1-356 and 18.1-357). One fed

eral court has said it was, Nash v. Air Terminal Services,

85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D. Va. 1949); another federal court,

on concession by a party, has proceeded on the assumption

that it was not, Williams v. Howard Johnson Restaurant,

268 F. 2d 845 (4th Cir. 1959). After the present cases were

tried, the Attorney General of Virginia (in response to an

inquiry from a municipality that still, it seems, desired to

enforce the segregation laws in accordance with their just

9 See note 6, supra.

10 Efforts are nevertheless made to achieve segregation by devices

short of literal enforcement of laws on their face requiring it. See

e.g., Dept, of Conservation & Development v. Tate, 231 F.2d 615

(4th Cir.) cert, denied 352 U.S. 838 (1956) (leasing of public park

facilities to lessee practicing segregation); Chance v. Lambeth, 186

F.2d 879 (4th Cir.) cert, denied 341 U.S. 941 (1951) (Ry. com

pany regulation used to enforce segregation after statute declared

unconstitutional); James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.

1959) (schools closed to avoid desegregation).

19

construction) gave it as Ms opinion that the statute does

not require restaurant segregation, but he relied wholly

on the rule ejusdem generis, hardly a satisfying guide for a

restaurant manager. Opinion of the State Attorney Gen

eral to the Commonwealth Attorney of the City of Roanoke,

Aug. 24, 1960, 5 Race Relations Law Reporter 1282 (1960).

The point has not been settled by the Virginia courts, and

is now without intrinsic interest, since on either construction

the statute is clearly void under the decisions of this Court.

But the question is not whether Virginia as a polity

literally required restaurant segregation. The question is

whether Virginia as a polity has contributed to maintain

ing the custom followed by Virginia as a community. And

it is beyond any question that a State which enacts that

whites and Negroes may not study together (Const, of Va.

§140; Code of Va., 1950, §22-221), marry one another (Code

of Va., 1950, §20-54), go to prison together (Code of Va.,

1958 Replacement Volume, §53-42), join a fraternity to

gether (Code of Va., 1953 Replacement Volume, §38.1-597),

go together to the hospital for feebleminded (Code of Vir

ginia, 1960 Supp., §37-183), wait for an airplane together

(Code of Va., 1959 Replacement Volume, §56-196), get on

a bus together (Code of Va., 1959 Replacement Volume,

§56-326),—is making it at least vastly more likely that

they will not, as a matter of custom, eat together or be fed

together. Segregation is all one piece; when the State holds

up the edifice at a hundred points by law, it is surely

contributing to its standing up even at the points where

the law does not directly take hold.

There is even good historic ground for the belief that

the segregation system, of which the “ custom” enforced

by Thalhimer’s Inc. is a part, was brought into being, or

at least given firm contour in its beginnings, by state law.

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 16-22, 81-85,

91-93.

20

Thalhimer’s Inc. therefore invoked the immediate force

of state law in order to continue obedience to a statewide

custom that is itself the creature of state law. The ele

ment of “private” choice in this pattern is negligible, and

Thalhimer’s Inc. has actually no “private” interest in the

matter at all, apart from the gains it may have anticipated

from following the state-fostered custom. On the most

stringent criteria, “ state action” permeates the whole course

of treatment to which these petitioners have been subjected.

A contrary holding would turn upside-down the criterion

stated in the Civil Rights Cases, for it would have to rest

on the proposition that action is “private” unless it is

wholly public—that the entrance of any small component

of private choice into an essentially public pattern robs that

pattern of its public character.

This being so, no other aspect of the present point is

even arguable, for racial segregation, where infected with

state power, is clearly unconstitutional.11

B. The decision below conflicts with decisions of this

Court securing the right to freedom of expression

under the Fourteenth Amendment.

It is stipulated in this case that petitioners, members of

the Negro race, came into the store in which they were

arrested for the purpose of peacefully seeking service at

a counter reserved for whites (R. Randolph 26, in stipula

tion repeated verbatim in all other records). It cannot

be doubted that such an entrance, for such a purpose, con

stitutes not only an attempt to eat lunch but also a solemn

expression of a demand for equal treatment. Although a

non-verbal expression of such a character is quite suffi

cient for invocation of the constitutional guarantees of

11 See note 8, supra.

21

freedom of expression, Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 TJ. S.

88; Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, it is fairly in

ferrable, from the stipulation that petitioners were “ re

fused service” (R. Eandolph 26), that they verbally re

quested it, and this too was, in the circumstances, very

clearly an expression of belief that it ought to be given

them.

The fact that these attempts at expression of belief oc

curred on private property is of course not enough, without

more, to strip them of constitutional protection. Marsh

v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501; Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S.

141; see also Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324

U. S. 793. These petitioners were, with the general public,

invited onto this property, and being lawfully there they

had the right to express themselves, at the least, on topics

connected with their relations with the store, and hence

clearly adapted to time and place. There is no hint in the

records that their expression wTas other than moderate and

peaceful. Nor is there any doubt that the machinery of

the state was invoked for the sole purpose of putting an

end to this expression, for it is stipulated that they were

refused service (R. Eandolph 26) and no reason is sug

gested for their attempted expulsion and arrest other than

their persistence in the expression of their peaceful demand.

But in these cases there is a more specific ground for

holding that the petitioners’ right to free expression has

been curtailed. These convictions were obtained without

clear evidence, in any of the cases, of notice to petitioners

of the authority, or even the identity, of the store employee

who ordered them out. In some of the cases the testimony

of the Commonwealth’s own witness is to the effect that

no notice of authority was given (e.g., R. Dalton 10-11).

In none of the cases was it made clear by the courts below

22

that such knowledge had to exist for a conviction to be

sustained.

The course of treatment of these cases leaves it unclear

on just what theory the Virginia courts proceeded to dis

regard the question of notice of authority, but it is crystal

clear that they did so disregard it. At many points in

these records, the prosecutor who tried all the cases states

explicitly his theory of the essentials to conviction, and

notice of authority is never one of them (e.g., R. Pinkston

13). In the Sherrod case, the objection was raised explicitly

by counsel for the defendant, in the form of a motion to

strike the Commonwealth’s evidence; the following quota

tion exhibits very clearly the theories on which the prosecu

tor and the police court judge were proceeding (R. 25-6):

Mr. Martin: If Your Honor please, we move to

strike the evidence of the Commonwealth in this case.

It appears to me that this case is even weaker than

the cases we tried yesterday. Here is a man that was

in Thalhimer’s, apparently on business, as a number

of other people were there as customers. The Common

wealth’s own witness does not deny that he was a

customer there and, for some reason he refuses to

state, he just asked him to leave. There is no state

ment from the Commonwealth’s Attorney or the Com

monwealth’s evidence that he even identified himself

as being an employee of Thalhimer’s. Here is a strange

man comes up to a stranger and orders him to leave

the store and he refuses to leave, as I would have done

or Your Honor would have done, and then he gets a

warrant for him and puts the processes of the State

of Virginia in motion to prosecute this man, charging

him with a crime. I submit that is no crime where a

stranger, an unidentified person, comes up and asks a

man to leave the store in which he is a customer and

23

an invitee. For that reason, we move to strike the

evidence.

Mr. Wilkinson: If Your Honor please, my remarks

will be very brief in this ease, but, as I recall the testi

mony, the man was advised several times to leave by

Mr. Hamblet and he was advised what would happen

if he did not leave, and he refused to leave, and I think

the Commonwealth has carried the burden of this case.

The Court: The motion is overruled.

In a good many of the cases, it is especially clear that no

rational trier of fact could have concluded, on the basis of

testimony, that the defendant had notice of the authority or

identity of the person ordering him to leave, for both the

Commonwealth witness and the defendant testified to the

contrary (e.g. R. Dalton 10-11, 14; R. Elizabeth Johnson

13-14, 16; R. Clarence A. Jones 19, 24). Yet a finding of

guilty was nonetheless entered by the Police Court judge.

The Hustings Court judge, with the transcripts of the

Police Court trials (and no other evidence) before him,

found the defendants all guilty, in identical opinions not

mentioning the question of notice of authority. No tran

script before him had adequate evidence for an affirmative

finding on this point, but it is even more significant that

many of them affirmatively forbade such a finding, as just

shown. His actions in these cases make it entirely clear

that he was proceeding throughout in entire disregard of

the question of the defendants’ notice of the authority of

the person giving the order on the basis of which conviction

was predicated.

In its opinion in the Randolph case, the Supreme Court

of Appeals, though it seems to find in the at best incon

clusive evidence ground for the “ inference” that Randolph

“ knew that Ames [who ordered him off] was a person

in authority . . . ” concedes that Ames neither identified

24

himself nor disclosed his authority, and says expressly

that the statute “does not require this” 202 Va. 661,------ ,

119 S. E. (2d) 817, 819. The Supreme Court of Appeals de

cided the other thirty-three cases without opinion, includ

ing those in which the absence of notice to defendants was

incontrovertible on the testimony.

From this history, it is impossible to be quite sure

whether these cases were tried and affirmed on the substan

tive theory that scienter is not an element in the charged

crime, or whether, on the other hand, the lack of evidence

of scienter (ranging in the cases all the way from a want

of clear evidence up to the decisive refutation, on the Com

monwealth’s own evidence, of the presence of scienter) was

simply disregarded by the trier of fact. What is entirely

clear is that one of these two things, or both of them in

interplay, did happen. As a practical matter, in the con

text of constitutionally protected free expression, they are

equivalents, for on either alternative the eases up to now

stand for the proposition that a man, engaged in the exer

cise of his federally protected right of free expression,

in a public place where he has been invited, must, at the

command of any casual stranger who neither identifies him

self nor states his authority, either cease his expression and

leave, or run the chance of successful criminal prosecution.

This is an unacceptable circumscription of the right of

free expression.

It may be true that in these cases it did turn out, at the

trial, that the persons issuing the request were authorized.

But the effect of this rule on freedom of expression cannot

practically be judged from the vantage point of hindsight.

At the time the purported order to leave is issued, the per

son subjected to it would be required, under this rule, either

to run the chance of jail or to cease his federally protected

expression at the command of one who may well be a mere

25

onlooker, and who does not claim to be anything else. Such

a rule, requiring hairbreadth decisions on the spur of the

moment, and on insufficient or non-existent data, would

inhibit and cripple the exercise of rights to which this

Court has given broad protection.

On this aspect, the present case is not materially dis

tinguishable from Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 4

L. ed. (2d) 205, recently decided in this Court, except that

in Smith the obscene books were at least in possession of

the defendant, as part of his stock in trade, while in this

case the authority of Thalhimer’s officers, or even their

identity, was in no sense a matter of which the petitioners

had any reason to have any special knowledge. This case,

therefore, presents an even more appealing set of cir

cumstances than Smith for application of the rule of the

latter case. See also Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183,

where the penalizing of unknowing membership in a sub

versive organization was held to offend against the right

of free political expression and association.

Surely, this Court would never hold that a speaker

could be convicted for disobeying a command to cease

speaking, given by a man in plain clothes who later turned

out to be a policeman, though at the time he did not identify

himself as such. Cf. Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315. But

the sustaining of the present convictions would require

just that deference to persons who may or may not be the

assistant managers of stores.

It should be added that the possibility of people in peti

tioners’ situation being told to leave by strangers is not

a mere philosophic one. The matters on which their protest

was mounted are of high, excited, and quite general public

interest in the affected communities.12 There was (and in a

12 See generally Pollitt, op. cit. supra note 3.

26

new case, would be) no reason for their assuming that any

body who told them to get out was thereunto authorized

by the Vice President in Charge of Store Operations.

C. Petitioners either were convicted without proof of

an element of the crime— their knowledge or no

tice of the authority of the persons ordering them

to leave— or if such knowledge or notice is not

an element of the crime, then they were convicted

under a statute which they could not have known

to embody the harsh and arbitrary rule that one

who refuses to leave a public place at the com

mand of a stranger does so at his peril. In either

case, standards of the Fourteenth Amendment

have been violated.

As petitioners have shown (point IB, supra) none of the

records in these thirty-four cases shows that petitioners

herein knew or had notice of the authority or position of

the persons ordering them from the premises of Thal-

himer’s, and some of them directly and unambiguously con

tradict the imputation of such notice. As exhibited in

the discussion under IB, supra, it cannot be surely known,

from the manner in which this point was dealt with in the

state courts, whether those courts considered the absence

of notice to be immaterial, holding scienter to be not an ele

ment of the crime, or whether, though taking it to be an

element of the crime, they proceeded to conviction without

evidence of its presence.

If the first alternative states the correct view, then the

Virginia rule is unbelievably harsh. Whatever may be the

case as to farmland or residential property, no one has any

practical reason to presume that anyone who tells him to

get out of a public place, to which the proprietor has in

vited him, is authorized to do so, when no claim of such

authority is made. Particularly is this true when his pres

ence on such publicly used property is manifestly in con

27

nection with a matter which is of high controversial interest

to the members of the community in general. A statutory

command to quit a public place when ordered to do so by a

person who later turns out to have been in authority, absent

so much as a claim of authority at the time, is, in a practical

situation such as that which confronted petitioners, very

close to a statutory command to quit a public place when

ever ordered to do so by any stranger, since the alternative

is running a risk of fine or imprisonment. Whether or not

such a rule might be held substantively wanting in due

process, cf. Lambert v. California, 355 U. S. 225, it is very

clear that, in the framework of Anglo-American conceptions

of crime, this statute gives no fair warning of such a rule.

People normally go about in public places under an assump

tion of general autonomy, obeying orders only from those

who at least claim with some definiteness the right to give

them. The petitioners, and others similarly situated, were

and are entitled to assume that this general rule conditions

the construction of this statute. As a matter of due process,

more warning than its innocuous text ought to be required

before persons are held to criminal liability under a rule so

arbitrary. Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 IT. S.

385; Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451.

As this Court has said:

“ The contention that an injury can amount to a crime

only when inflicted by intention is no provincial or

transient notion. It is as universal and persistent in

mature systems of law as belief in freedom of the

human will and a consequent ability and duty of the

normal individual to choose between good and evil.”

Morissette v. U. S., 342 U. S. 246, 250.

The utterances of the Morissette case, it is true, were de

livered in the context of this Court’s responsibility to the

28

federal criminal law. But the holding and the opinion in

escapably rest on an awareness of the pervasive character

of the concept of scienter as an element in criminality.13

The exceptions, fully canvassed in Morissette, 342 U. S. 252-

260, have no application to the present case. It is this per

vasiveness, and hence expectability, of the requirement of

scienter, that makes it clear that a general statute like the

present one, though failing explicitly to lay down the re

quirement of scienter, gives, in the whole frame of civ

ilized conceptions of criminality, no adequate warning of

an absolute liability.

Trespass statutes like the present, far from falling in

the class of “public welfare” statutes as to which absolute

liability has been considered appropriate (see Morissette

v. U. 8., supra, 342 U. S. 252-260)14 root in a long common

law tradition which by no means equated civil and criminal

trespass, but required for the latter such special circum

stances as breach of the peace. Henderson v. Common

wealth, 49 Va. (8 Grat) 708 (Va. Gen. Ct. 1852); Rex v.

Storr, 3 Burr. 1698. Cf. American Law Institute, Model

Penal Code, Tentative Draft No. 2, §206.53, Comment.

In the contexts, then, of our criminal law as a whole,

of criminal trespass in particular, and of normal expecta

tions in fact, this statute conveys inadequate warning of

its drastic tenor, if its meaning is that scienter is no part

of the crime charged.

If, on the other hand, the correct Virginia rule is that

§18-225 applies only when the accused had knowledge or

notice of the authority of the person ordering him off the

property, then these convictions were had without the most

13 See Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Columbia L. Rev. 55,

55-6 (1933).

14I d at 73, 84-88.

elementary form of due process. Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U. S. 199. The records themselves would not support

conviction if notice is an element. (See point IB, supra,

pp. 21-23.)

Thus, either one of two things must be true: 1) By a

draconic construction of §18-225, petitioners are held to a

standard of which they had no adequate warning; or 2) on

a reasonable construction, the evidence fails at a crucial

point to support the convictions. In either case, due proc

ess is wanting.

II

The Public Importance of the Issues Presented.

Since February 1960, when these thirty-four petitioners

sought service at eating facilities then reserved for white

patrons of Thalhimer’s, Inc., were refused service there

solely because of their race or color, and subsequently

were arrested upon their refusal to leave without obtaining

service, thousands of students have participated in similar

protest demonstrations. Their protests spread to 65 south

ern cities within two months and today they have engulfed

the entire South.13 However, despite widespread gains in

nondiscriminatory treatment at lunch counters and other

places of public accommodation,16 most of these demon

strations have, as in the cases at bar, culminated in arrests

and criminal prosecutions which variously present as an

underlying question the issues presented herein. Many of

these cases have already reached the appellate courts of 15 16

15 See Pollitt, supra, note 3, at 317-336; Citizens in Protest: A

Comment on the Student Demonstrations of 1960, 6 How. L. J.

187-192 (1960) ; Foster, Race Relations in the South, 1960, 30 J.

Negro Ed. 138, 147-149 (1961).

16 See Petition for Cert., p. 26, Briscoe v. Louisiana, infra note 17.

30

Louisiana,17 North Carolina,18 Florida,19 Maryland,20 Ar

kansas,21 Alabama,22 Georgia,23 South Carolina,24 Texas,20

17 E.g., Garner v. Louisiana, cert, granted 29 U.S.L. Week 3276

(No. 617, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 26, 1961 Term) ; Briscoe v.

Louisiana, cert, granted Id. (No. 618, 1960 Term, renumbered No.

27, 1961 Term ); Hoston v. Louisiana, cert, granted Id. (No. 619,

1960 Term; renumbered No. 28, 1961 Term).

18 E.g., Avent v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, 29 U.S.L.

Week 3336 (No. 943, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 85, 1961 Term );

Fox v. North Carolina, petition for cert, filed, Id. (No. 944, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 86, 1961 Term) ; Williams v. North. Caro

lina, petition for cert, filed 29 U.S.L. Week 3319 (No. 915, 1960

Term; renumbered No. 82, 1961 Term).

19 E.g., Steele v. City of Tallahassee, cert, denied 29 U.S.L. Week

3263 (No. 671, 1960 Term ); Steele v. City of Tallahassee, 120

So.2d 619 (Fla. 1960) ; State ex rel. Steele v. Stoutamire, 119 So.2d

792 (Fla. 1960).

20 E.g., Griffin v. State, decided June 8, 1961 (Md. Ct. App. No.

248, September 1960 Term ); Drews v. State, 167 A.2d 341 (Md.

1961), jurisdictional statement filed 29 U.S.L. Week 3286 (No.

840, 1960 Term; renumbered No. 71, 1961 Term).

21 E.g., Briggs v. State, Ark. Sup. Ct. (No. 4992) with which

Smith v. State (No. 4994) and Lupper v. State (No. 4997) have

been consolidated.

22 E.g., DuBose v. City of Montgomery, 127 So.2d 845 (Ala. App.

1961); cf. King v. City of Montgomery, 128 So.2d 340 (Ala. App.

1961).

23 E.g., Samuels v. State, 118 S.E.2d 231 (Ga. App. 1961);

Martin v. State, 118 S.E.2d 233 (Ga. App. 1961); Walker v. State,

118 S.E.2d 284 (Ga. App. 1961) ; cf. King v. State, 119 S.E.2d

77 (Ga. 1961).

24 E.g., see Petition for Cert., p. 27 note 15, Briscoe v. Louisiana,

supra note 17.

25 E.g., Crossley v. State, 342 S.W.2d 339 (Tex. Crim. App.

1961); Rucker v. State, 342 S.W.2d 325 (Tex. Crim. App. 1961);

Briscoe v. State, 341 S.W.2d 432 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960) ; Tucker

v. State, 341 S.W.2d 433 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960); Johnson v.

State, 341 S.W.2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960) ; Rucker v. State,

341 S.W.2d 434 (Tex. Crim. App. 1960).

31

and Virginia;26 countless others are still at the trial level

in those states and also in Kentucky, Tennessee, West

Virginia and Mississippi.

In addition to the mass litigation which has resulted

from these student demonstrations, they have created new

problems for local law enforcement authorities27 and they

have spurred the enactment of new laws or more stringent

amendments to existing laws.28 Moreover, the two national

political parties were impelled in an election year to en

dorse such demonstrations and pledge stronger sanctions

for civil rights in their platforms.

It is therefore of great public importance that this Court

consider the issues presented herein so that the courts

below, and people everywhere, can be authoritatively ap

prised regarding the constitutional limitations on state

prosecutions of young people for engaging in this type

of protest.

26 E.g., Thompson v. Commonwealth, petition for writ of error

filed July — , 1961; Henry v. Commonwealth, writ of error denied

April 25, 1961 (No. 5093); ef. Tinsley v. Commonwealth, 202 Va.

707, petition for cert, filed July 24, 1961, 30 U.S.L. W eek------ .

27 Cf. Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F.2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960).

28 E.g., see Va. Acts, 1960, ch. 97; S.C. Acts, 1960, No. 743;

La. Acts, 1960, Nos. 70, 77, 80; Dallas, Tex., 1960 Ordinance (6

Race Rel. L. Rep. 317).

32

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respect

fully submitted that the petition or petitions for writ

of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

Martin A. Martin

Clarence W . Newsome

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond, Virginia

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. B lack, Jr.

E lwood H. Chisolm

Of Counsel

33

APPENDIX

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

at R ichmond

Present: All the Justices

Record No. 5233

R aymond B. R andolph, J r .

Commonwealth oe V irginia

Opinion by Chief Justice J ohn W . E ggleston

Richmond, Virginia, April 24,1961

F rom the H ustings Court of the City of R ichmond

W. Moscoe Huntley, Judge

Raymond B. Randolph, Jr., hereinafter called the de

fendant, was one of thirty-four Negroes arrested under

separate warrants charging each with trespassing on the

property of Thalhimer Brothers, Incorporated, in viola

tion of Code, § 18-225, as amended. Each was convicted

in the police court and upon appeal to the Hustings Court,

with their consent and the concurrence of the court and

the attorney for the Commonwealth entered of record, the

several defendants were tried jointly by the court and

without a jury. Upon consideration of the evidence the

34

court adjudged that each defendant was guilty of trespass

as charged and assessed a fine of $20 against each. To

review this judgment each defendant has filed a petition

for a writ of error. We have granted the defendant, Ran

dolph, a writ of error and deferred action on the other

petitions until this case has been disposed of.

Section 18-225 of the Code of 1950 (as amended by Acts

of 1956, ch. 587, p. 942; Acts of 1958, ch. 166, p. 218) reads

as follows fi

18-225. Trespass after having been forbidden to

do so.—If any person shall without authority of law

go upon or remain upon the lands or premises of an

other, after having been forbidden to do so by the

owner, lessee, custodian or other person lawfully in

charge of such land, or after having been forbidden to

do so by sign or signs posted on the premises at a

place or places where they may be reasonably seen,

he shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon

conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not

more than one hundred dollars or by confinement in

jail not exceeding thirty days, or by both such fine and

imprisonment.”

On this appeal the defendant makes several contentions

which overlap but may be fairly summarized thus: (1) The

judgment is contrary to the law and the evidence in that

there is no showing that the defendant was guilty of hav

ing violated the statute; (2) The statute as here applied

violated the rights guaranteed to the defendant by the

fourteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

1 This statute was further amended by the Acts of 1960, ch. 97,

p. 113, and as so amended was recodified as Code, 1960 Replace

ment Volume, § 18.1-173, by the Acts of 1960, ch. 358, p. 448.

35

The undisputed facts are before us on the evidence heard

in open court and a stipulation of the parties. Thalhimer

Brothers, Incorporated, a privately owned corporation,

operates a large department store in the city of Richmond.

It operates lunch counters in the basement and on the

first floor and a restaurant on the fourth floor. Negro

patrons are served at one of the lunch counters in the

basement. Only white patrons are served at the other

lunch counters and in the restaurant. The separation of

these facilities for serving white and Negro customers,

respectively, is well known to the patrons of the store.

On February 22, 1960, the defendant and the thirty-three