Lea v. Cone Mills Corporation Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

September 15, 1966 - October 8, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lea v. Cone Mills Corporation Joint Appendix, 1966. 8b346ec8-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d29240ce-2c91-4f57-a325-7ce05b0352a6/lea-v-cone-mills-corporation-joint-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

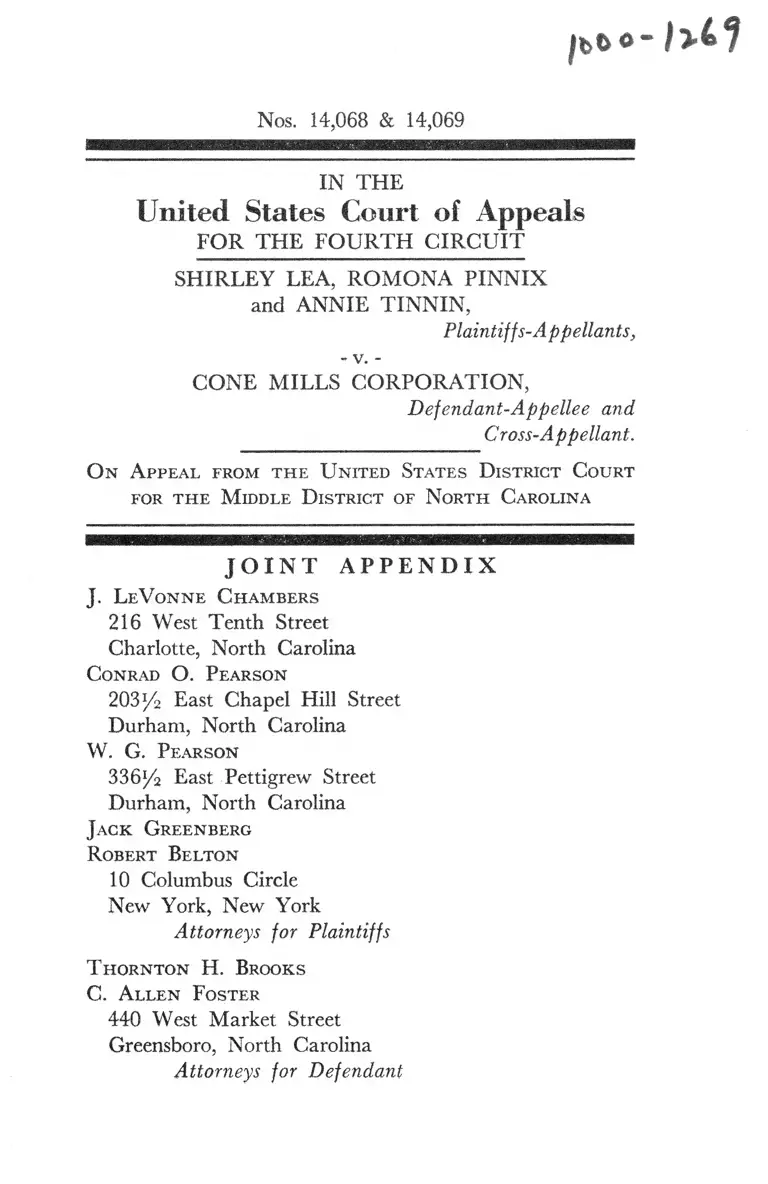

Nos. 14,068 & 14,069

)*t>1

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FO R THE FO U RTH C IR C U IT

SHIRLEY LEA, RO M O N A PINNIX

and ANNIE TINNIN,

Plaintiff s- Appellants,

- v. -

CONE M ILLS CO RPORATIO N ,

Defendant-Appellee and

Cross-Appellant.

O n A ppeal from the U nited States District Court

for the M iddle District of North Carolina

J O I N T A P P E N D I X

J. LeV onne C hambers

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Conrad O. Pearson

203/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

W. G. Pearson

336/2 East Pettigrew Street

Durham, North Carolina

Jack Greenberg

Robert Belton

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

T hornton H. Brooks

C. A llen Foster

440 West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carolina

Attorneys for Defendant

I N D E X

Page

Final Order ........................................................................... 1

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law .................... 5

Findings of Fact ............................................................ 6

Discussion......................................................................... 15

Conclusions of L a w ........................................................ 18

Notice of Appeal by Plaintiffs ......................................... 19

Notice of Cross-Appeal by Defendant .......................... 20

Complaint of Plaintiffs........................................................ 20

Answer of Defendant .......................................................... 25

Order [class action] 29

Stipulation [pre-trial conference] ..................................... 30

Memorandum Order [triable issues] ................................. 34-

Trial Proceedings

Witnesses of the Plaintiffs:

Shirley Aim Lea

Direct Examination.................................................. 47

Cross Examination .................................................. 52

Redirect Examination............................................. 72

Deposition of Shirley Ann Lea— PL Ex. 12 .......... 114

Romona Pinnix

Direct Examination.................................................. 87

Cross Examination .................................................. 92

Deposition of Romona Pinnix— PI. Ex. 13 ............ 117

Annie Tinnin

Direct Examination.................................................. 74

Cross Examination ................................................. 81

i

Page

Deposition of Annie Tinnin— PI. Ex. 14 122

Witnesses of the Defendant:

Mabel Miller Austin

Direct Examination.................................................. 96

Deposition of Mable Miller Austin-—PI. Ex. 16 130

Otto King

Direct Examination.................................................. 102

Cross Examination ................................................. 110

Deposition of Otto King— PI. Ex. 15 127

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1

(Charge by plaintiff Lea with Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission— signed 2 September

1965) ........................................ 37

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4

(Decision of Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission— dated 24 June 1966) ............................ 39

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 17

(Deposition of John W. Bagwill— dated

11 May 1967) ................................................................. 131

Defendant’s Exhibit 1

(Personnel Policy Manual— dated 1 April 1963) 42

n

9-15-66

11- 7-66

1-31-67

3- 1-67

3- 1-67

6-28-67

6-28-67

11- 2-67

3-15-68

5-23-68

9-17-68

11- 3-68

11- 20-68

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

Lea, et al.

v.

Cone Mills Corporation

Filed Complaint and cost bond

Filed defendant’s Answer

Filed Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference

Filed defendant’s Motion to Dismiss

Filed defendant’s Motion to determine if class

action

Filed plaintiffs’ Response to Defendant’s Motion

to Dismiss and Motion re class action

Filed Order signed by Judge Eugene A. Gordon

on class action

Filed Order signed by Judge Gordon denying

defendant’s Motion to Dismiss

Final pre-trial conference before Judge Gordon

and filed Stipulation of the parties

Filed Memorandum Order signed by Judge

Gordon as to triable issues

Case called for trial on merits before Judge

Edwin M. Stanley. The case was tried before

the Court without a jury, and both parties

presented oral testimony and documentary evi

dence into the record

Filed plaintiffs’ proposed Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law and supporting Brief

Filed defendant’s comments on, alteration of

and additions to plaintiffs’ proposed Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law

iii

1- 9-69

7-29-69

9- 8-69

9-26-69

9-30-69

9-30-69

10- 8-69

Oral argument by parties before Judge Stanley

Filed Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law

and Discussion by Judge Stanley

Filed Order by Judge Stanley ordering:

1. Enjoining defendant from discriminating

against Negro female applicants for employ

ment at Eno plant because of race in violation

of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

2. Defendant to adopt and implement ob

jective and reviewable standards and procedures

with respect to the hiring and assignment of

females at its Eno plant, and providing steps

for the implementation of the terms of the

Order

3. Denial of back pay for the plaintiffs

and their attorneys’ fees, in the exercise of the

Court’s discretion

4. Plaintiffs are allowed their costs

Filed plaintiffs’ Notice of Appeal to the United

States Court of Appeals

Filed defendant’s Notice of Cross-Appeal to

the United States Court of Appeals

Filed defendant’s Motion for Stay of Order

Filed Order signed by Judge Stanley granting

stay of Order, upon consent of plaintiffs

xv

IN THE

United States District Court

for the Middle District

OF N O RTH CAROLINA

DURH AM DIVISION

SHIRLEY LEA, RO M O N A PINNIX, )

and ANNIE TINNIN, )

)

Plaintiffs, )

) No. C-176-D-66

v. )

)

CONE M ILLS CORPORATION , )

)

Defendant. )

O R D E R

[Filed 8 September 1969]

This cause came regularly on for trial before the Court

without a jury, and was duly submitted for consideration

and decision, and the Court, after due deliberation, having

on the 29th day of July, 1969, filed herein its Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law;

Now, therefore, pursuant to said Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law filed herein, it is ORDERED, A D

JUDGED and DECREED as follows:

1. The defendant, Cone Mills Corporation, its officers,

agents, employees, servants, successors and all persons and

2

organizations in active concert or participation with them,

are hereby permanently enjoined and restrained from dis

criminating against Negro female applicants for employ

ment at the Cone Mills manufacturing facility located in

Hillsborough, Orange County, North Carolina, known as

the Eno Plant, because of race in violation of Title V II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq.

2. The defendant shall forthwith adopt and implement

objective and reviewable standards and procedures with

respect to the hiring and assignment of females at its Eno

Plant, designed to insure that all female applicants for

employment are afforded equal consideration for any

vacancy which may exist during the period of time when

their application was current.

3. The defendant shall, within twenty days of the entry

of this Order, post on the bulletin boards at its Eno Plant

a brief written explanation of the provisions of this Order,

and the objective and reviewable standards and procedures

adopted with respect to the hiring of females at its Eno

Plant, prepared in non-technical terms, understandable to

all employees who have had limited educational oppor

tunities.

4. The defendant shall file with the Court and serve

copies on counsel for the plaintiffs, promptly after ninety

days from the entry of this Order, a report reflecting the

following information with respect to its Eno Plant:

(a) All changes in the procedures governing the

selection of applicants for employment which differ

from those set forth in the defendant’s Personnel Policy

Manual which was introduced into evidence in this

case. The report will also include all steps taken in

compliance with the provisions of Paragraphs 2 and 3

of this Order.

a

(b) Copies of any printed matter or letters pub

lished or distributed in effectuating compliance with

the terms of this Order.

5. With respect to the plaintiffs, and the class they

represent, the defendant at its Eno Plant is specifically

ordered:

(a) To refrain from giving any applicant for em

ployment preference over any other applicant because

of her relation to or acquaintance with any officer,

employee or former employee, at the Eno Plant, or at

any other plant operated by the defendant.

(b) To notify all applicants for employment, at

the time of their application, that they are required to

renew their applications each thirty days in order to

maintain same on an active basis. Such notification

shall be given by having each application form contain

a printed statement that such application would remain

active for a period of thirty days, and that the appli

cant will not be considered for employment after thirty

days unless she renews her application in writing, and

by calling same to the attention of each applicant.

(c) When a vacancy is to be filled by the employ

ment of an individual not then employed at the Eno

Plant (i.e., “new hire” or “ re-hire” ), the personnel

manager will consider those persons whose applications

were made within the preceding thirty days, and he

shall offer the opportunity to fill such vacancy to the

applicant who is available and considered qualified for

the vacancy, and will, to the extent practicable, choose

that qualified person in the order of the filing date of

her application.

(d) Each application for employment shall be dated

either by the applicant, personnel manager, or the

4

receptionist, and each shall contain a specific written

designation of the race of the applicant.

(e) If any applicant eligible for consideration fails,

in the judgment of the personnel manager, to meet

the minimal requisite qualifications for any vacant

position, a brief statement of the reason therefor shall

be recorded on the application. Similarly, if any appli

cant declines to accept the position offered, or cannot

be reached by telephone, or any other reasonable means

designated in the application, within a reasonable time,

this information will likewise be recorded on the appli

cation.

6. The defendant shall make a reasonable effort to con

tact each of the named plaintiffs herein, as well as Lizzie

M. Bradshaw, Magdalene Bradshaw and Ida Fuller, and

advise them that any of them who desire to be considered

for employment may file an application in writing, and that

same will be considered in the manner provided in this

Order and the objective and reviewable standards and pro

cedures adopted to implement this Order. If the personnel

manager is unable to communicate with any of said indi

viduals by telephone or other means of communication,

he shall endeavor to contact her by sending a letter by

certified mail, return receipt requested, addressed to her

last-known address.

7. The defendant shall not discriminate or retaliate in

any manner against any employee or applicant or other

person or organization who has furnished information or

participated in any respect in the investigation of the em

ployment practices at the Fmo Plant in connection with this

action.

8. Back pay for plaintiffs, and any members of the class

they represent, and attorneys’ fees, are denied in the exer

cise of the Court’s discretion.

9. The plaintiffs are allowed their costs as provided

by Local Rule 27.

10. The Court retains jurisdiction of this cause.

EDW IN M. STANLEY

United States District Judge

September 5, 1969

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

[Filed 29 July 1969]

STANLEY, CHIEF JUDGE

The plaintiffs, Shirley Lea, Romona Pinnix, and Annie

Tinnin, all Negro females residing in Orange County,

North Carolina, seek to restrain the defendant, Cone Mills

Corporation, from continuing or maintaining any policy

or practice limiting or otherwise interfering with the rights

of plaintiffs, and others similarly situated, to enjoy equal

employment opportunities without regard to race or color,

as secured by Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. I 2000 et seq.

The case was tried by the Court without a jury. Follow

ing the trial, counsel for the parties filed proposed findings

of fact and conclusions of law, and briefs, and later ap

peared before the Court and orally argued their respective

contentions.

After considering the entire record, including argu

ments of counsel, the Court now makes and files herein its

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, as follows:

6

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. Plaintiffs, Shirley Lea, Romona Pinnix and Annie

Tinnin, are Negro citizens of the United States and the

State of North Carolina, residing in Orange County,

North Carolina.

2. The defendant, Cone Mills Corporation (herein

after referred to as “ Cone Mills” ), is a corporation

incorporated and doing business pursuant to the laws

of the State of North Carolina.

3. The defendant maintains its principal corporate

office and place of business in Greensboro, North Caro

lina, and also maintains and operates mills, facilities

and offices located in various other cities and towns in

the State of North Carolina. Among other manufactur

ing plants, defendant operates a mill known as the Eno

Plant, located in Hillsborough, Orange County, North

Carolina, for the manufacture of greige (unfinished)

goods.

4. As of July 2, 1965, 346 persons were employed

in the Eno Plant. O f these, approximately 310 were

white employees and 36 were Negro male employees.

No Negro females were employed in any capacity at

the Eno Plant.

5. Defendant is an employer within the meaning of

S 701(b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

I 2000e-(b).

6. The Cone Mills’ Personnel Policy Manual, ap

plicable to all Cone Mills facilities, including the Eno

Plant, which has been in effect since April 1, 1963,

establishes company policy for the recruitment and

selection of applicants for employment. The primary

standards applied is the applicant’s ability to perform

7

any job currently vacant, and the manual directs that

this standard be applied without regard to race, creed,

color or national origin. When two or more applicants

each meet the ability criteria for a particular vacancy,

the manual establishes the following priorities for selec

tion among the applicants:

(a) Laid-off employees

(b) Former employees

(c) Persons residing in or near the communi

ties in which Cone Mills plants are

located

7. The written hiring procedures of Cone Mills, also

applicable to the Eno Plant, are as follows:

(a) The applicant fills out an application

form, is interviewed by the personnel

manager, and given aptitude and visual

tests.

(b) The applicant’s work history is investi

gated, and if found staisfactory, the ap

plicant is further interviewed.

(c) Applicants found satisfactory are then

given a physical examination.

(d) Applicants satisfying all such require

ments, including the physical examina

tion, are offered employment.

8. When the portion of the Personnel Policy Manual

covered by Finding 7 was issued, the testing of appli

cants referred to in sub-paragraph (a) was optional

with various plant managers. All other provisions were

mandatory. Testings began at the Eno Plant in Novem

ber or December of 1965.

9. Prior to July 2, 1965, males, Negro and white,

and white females were employed in various job classi

fications at the Eno Plant. No Negro females had ever

been employed in any capacity at the plant as of that

date. However, prior to the spring of 1965, no Negro

females had ever applied for employment at the plant.

While unable to recall specific names, dates or circum

stances, the personnel manager and receptionist at the

Eno Plant stated that some Negro females did apply

for jobs between January 1, 1965, and July 2, 1965.

10. In 1960 or 1961, John Bagwill, the then Vice

President for Industrial Relations of Cone Mills, re

quested and received a review of Cone’s hiring policies

and procedures with regard to the number of Negroes

employed. In 1963, more than one year before the

enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the pre

viously referred to directive to plant managers was

placed in the Personnel Policy Manual. This directive

made it mandatory that there be no discrimination on

the basis of race in the hiring or promotion of Cone

Mills employees. In the summer of 1965, shortly before

the effective date of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Cone

Mills officials met with all plant managers and reviewed

the provisions of the Act and the established company

policy. No specific recommendation was made, how

ever, concerning the hiring of Negro females at the

Eno Plant.

11. Prior to July 9, 1965, Cone Mills performed

some work at some of its plants and mills pursuant to

contracts with the United States under Executive Order

No. 10925, and therefore was under an obligation to

institute an affirmative action program to insure that

its hiring and promotional practices were carried out

without regard to race, creed, color or national origin

of the applicants and employees. There is no evidence,

however, that Cone Mills has ever been found in viola

tion of its affirmative obligation to insure non-discrimi

nation.

12. Both before and after July 2, 1965, the practice

at the Eno Plant was to accept applications from all

applicants, even though no vacancy existed at the time

the application was made. The only times no applica

tions were taken were the last week of July of each1

year when the plant was closed for vacations, and the

single period of about one week in June of 1965 when

a sign was posted on the door that no applications

would be received.

13. No basic changes occurred in the written hiring

policies of Cone Mills subsequent to July 2, 1965, ex

cept to provide that, in addition to “ race, creed, color

or national origin,” “ sex” would not be a consideration

in the hiring and promotion of applicants and em

ployees.

14. Because of the requirements of physical strength,

certain jobs at the Eno plant are considered “ male”

jobs, and other jobs, not so physically demanding, are

considered “ female” jobs. For example, all jobs in the

carding department, with the exception of the part-

time job of lab technician, are considered male jobs.

The classifications of spinner, spool tender, quiller

operator, and battery filler, are considered female jobs.

Jobs in the cloth room are considered male jobs.

15. This action was instituted on September 15,

1966, and by November 1, 1966, there were five Negro

females employed at the Eno Plant.

16. The present personnel manager at the Eno

Plant had served in that capacity for at least ten years

10

prior to the filing of the complaint in this action. The

personnel manager is also the office manager.

17. With regard to the hiring procedures at the

Eno Plant, an applicant for employment is given an

application form by the receptionist. When the form

has been completed, the applicant is interviewed by the

personnel manager to determine the applicant’s work

history. The interview also covers the determination of

facts concerning the priorities enumerated in Finding

6, such as whether the applicant is a former Cone Mills

employee, whether he resides in a community near a

Cone Mills facility, and whether he has friends or

relatives working at the plant in question. This inter

view is conducted without regard to the existence of a

vacancy. When there is a vacancy, an interview, under

certain circumstances, is scheduled between the appli

cant and the supervisor in whose department the va

cancy exists. If the applicant is satisfactory and a

vacancy exists, the applicant is given a physical exami

nation. If the applicant passes the physical examination,

he is given the job.

18. If the applicant is not offered a job at the time

the application is made, the application is placed on

the top of a stack of previously filed applications on

the desk of the personnel manager. It is expected that

applications will be renewed approximately every two

weeks to assure the personnel manager that the appli

cant is still interested in a job. As applications are re

newed, they are placed on top of the stack and the

renewal date recorded. If an applicant does not renew

his applictaion within approximately two weeks, his

application stays on the bottom of the stack. At some

point between two weeks and a month, applications

which have not been renewed are filed in an alpha-

11

betical file. If a renewal is subsequently made, the

application is removed from the alphabetical file, the

renewal date is noted thereon, and the application is

again placed on top of the stack.

19. When a vacancy exists and no prospect fitting

the qualifications happens to apply personally, the per

sonnel manager examines the files of current applica

tions for a suitable prospect. If there is such an appli

cation on file, the applicant is contacted by telephone,

postcard or through the references he has given on the

application. After a satisfactory physical examination,

he is offered the job. If no applicant with experience is

available, the personnel manager will consider employ

ing an inexperienced person.

20. Generally, a vacancy in the Eno Plant can be

filled within one or two days.

21. In filling vacancies, the Eno Plant Manager

accords first priority to those applicants with experi

ence, either in the particular job to be filled or in a

related industry. Second priority is accorded to an

applicant who has a relative then working at the Eno

Plant. Next in order of priority is an applicant who

has a close friend working at the plant. Residence of

the applicant is the last in the order of priority. None

of the plaintiffs have relatives or close friends employed

at the Eno Plant, and none were experienced in any

type of manufacturing work.

22. No applicant is required to disclose his race on

the application form. He is required, however, to list

the schools which he attended, and, prior to 1965, the

race of the applicant could generally be determined by

the schools the applicant had attended because the

12

schools in Orange County were at that time predomi

nantly Negro or predominantly white.

23. On one or more occasions prior to September

2, 1965, some of the plaintiffs had applied for employ

ment at the Eno Plant, and had gained the impression

that the Eno Plant, as a matter of company policy, did

not employ Negro females.

24. On the morning of September 2, 1965, pursuant

to a previous agreement, the plaintiffs and several other

Negro females met at a church and received instruc

tions with respect to plants they were to visit and make

applications for employment. It was part of the plan

for the individuals to return to the church following

the filing of the applications in order to sign complaints

against companies which did not offer them employ

ment.

25. On September 2, 1965, each of the plaintiffs, in

addition to several other Negro females, applied for

employment at the Eno Plant. Plaintiffs and the other

Negro females were allowed to file applications. After

completing the applications, the personnel manager

interviewed the plaintiffs and the other applicants two

or more at a time.

26. When the plaintiffs applied for employment at

the Eno Plant on September 2, 1965, one of them, Mrs.

Tinnin, was already employed, one had never worked

before, and none had had experience working in a

textile plant.

27. Plaintiffs Lea and Pinnix were interviewed by

the personnel manager at the same time. Both testified

that the personnel manager told them that the Eno

Plant did not employ Negro females. The personnel

manager did not remember the question being asked,

13

but testified that it was a fact that no Negro females

had ever been employed at the plant. From the con

flicting evidence, it is found that, for all practical pur

poses, Negro females were not considered for employ

ment at the Eno Plant, at least prior to July 2, 1965.

28. Plaintiffs Pinnix and Tinnin listed telephone

numbers on their application forms. As of the date of

the trial neither of them had been contacted by tele

phone or otherwise concerning the possibility of em

ployment. However, one of the Negro females who

applied for employment along with the plaintiffs re

newed her application subsequent to September 2, 1965,

and was employed in August of 1966, when a vacancy

occurred and no experienced person could be found to

fill the position.

29. The history of employment at the Eno Plant

shows that the company relies heavily on the employ

ment of relatives and friends of the family as a prime

source of filling vacancies. A number of members of the

same family are employed at the Eno Plant at the same

time. The Eno Plant is practically the only manufactur

ing plant in the Hillsborough area which offers indus

trial employment, and is the only textile mill in the area

operated to any extent.

30. The Personnel Policy Manual does not require

the renewal of applications every two weeks, and the

plaintiffs were not advised that in order for their appli

cations to remain active it would be necessary for them

to renew their applications approximately every two

weeks.

31. On or about November 5, 1965, approximately

two months after plaintiffs applied for employment, a

vacancy occurred for which at least one of the plain-

14

tiffs could have been employed. An inexperienced white

female was employed to fill the vacancy, and no effort

was made to contact any of the plaintiffs. The first

Negro female employed at the Eno Plant was employed

on March 17, 1966.

32. Between July 2, 1965, and November 1, 1966,

approximately 167 persons were employed at the Eno

Plant. O f these, 85 were white males, 53 were Negro

males, 22 were white females, and 7 were Negro females.

33. On or about October 26, 1965, the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission accepted charges

as properly filed made by each of the named plaintiffs,

as well as charges made by Lizzie M. Bradshaw, M ag

dalene Bradshaw, Ida Fuller, Inez Corbett, Laura Jean

Battle, Caroline Corbett, and Annie Torraine, all Negro

females residing in Orange County, North Carolina,

alleging that they had been denied employment by

Cone Mills at its Eno Plant on September 2, 1965,

because of their race.

34. On June 24, 1966, the Equal Employment O p

portunity Commission found reasonable cause to believe

that the named plaintiffs, and Lizzie Bradshaw, M ag

dalene Bradshaw, and Ida Fuller, had been denied

consideration for employment on September 2, 1965,

because of their race.

35. By letter dated August 19, 1966, Kenneth F.

Holbert, Acting Director of Compliance for the Com

mission, sent letters to each of the named plaintiffs

advising that “ due to the heavy workload of the Com

mission, it has been impossible to undertake or to con

clude conciliation efforts,” and that a civil action could

be filed in the appropriate Federal District Court.

15

36. The complaint in this action was filed on Sep

tember 19, 1966 within 30 days after notification from

the Commission.

D I S C U S S I O N

Section 703(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) provides:

“ (a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for an employer—-

“ (1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge

any individual, or otherwise to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his com

pensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of em

ployment, because of such individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

“ (2) to limit, segregate, or classify his em

ployees in any way which would deprive or tend

to deprive any individual of employment oppor

tunities or otherwise adversely affect his status

as an employee, because of such individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Section 706(g) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2Q00e-5(g) provides:

“ (g) If the court finds that the respondent has

intentionally engaged in or is intentionally engaging in

an unlawful employment practice charged in the com

plaint, the court may enjoin the respondent from engag

ing in such unlawful employment practice, and order

such affirmative action as may be appropriate, which

may include reinstatement or hiring of employees, with

or without back pay (payable by the employer, em

16

ployment agency, or labor organization, as the case may

be, responsible for the unlawful employment practice).

Interim earnings or amounts earnable with reasonable

diligence by the person or persons discriminated against

shall operate to reduce the back pay otherwise allow

able. No order of the court shall require the admission

or reinstatement of an individual as a member of a

union or the hiring, reinstatement, or promotion of an

individual as an employee, or the payment to him of

any back pay, if such individual was refused admission,

suspended, or expelled or was refused employment or

advancement or was suspended or discharged for any

reason other than discrimination on account of race,

color, religion, sex or national origin or in violation of

section 2000e-3(a) of this title.”

While the defendant’s Personnel Policy Manual, effec

tive since April 1, 1963, directs the selection of applicants

for employment without regard to race, statistics, which

often tell more than words, effectively refute the claim

that the policy was practiced with respect to Negro females.

State of Alabama v. United States, 5 Cir., 304 F.2d 583

(1962). The fact that no Negro females had applied for

employment before the spring of 1965 does not, contrary

to the argument of defendant, show either lack of interest

or disprove discrimination. The more plausible explanation

of this inaction is that, because of defendant’s hiring prac

tices over a long period of years, Negro females felt their

efforts to obtain employment would be futile. Cypress v.

Newport News General & Nonsectarian Hosp. Ass’n., 4 Cir.,

375 F.2d 648 (1967). Moreover, defendant’s hiring pro

cedures of granting initial hiring preference to former em

ployees and close friends and relatives of its existing work

force is inherently discriminatory against Negro females.

Dobbins v. Local 212, International Bro. of Elec. Wkrs.,

292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D.Ohio, 1968). Even though seven

17

Negro females have been employed, the hiring preferences

of defendant will continue to place Negro female applicants

at a competetive disadvantage when seeking employment,

thus constituting a prima facie inference of discrimination.

Another practice inherently discriminatory, particularly

when tested by its operation and effect, was the failure of

the defendant to notify the plaintiffs that they were re

quired to renew their applications about every two weeks

in order for them to be considered for employment in the

event a vacancy arose. This renewal policy was not included

in any written manual or other hiring policy to which the

plaintiffs would have had access. Since plaintiffs had no

employed relatives or friends whereby they could learn

of the policy, they were effectively denied the right to even

be considered for employment after about two weeks from

the time their applications were filed.

The Court is authorized by 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) to

enjoin the discriminatory employment practices engaged

in by defendant with respect to Negro female employees

at its Eno Plant, and the plaintiffs, and the class they

represent, are entitled to an order which will effectively

eliminate such discriminatory practices. Since it is clearly

apparent that when plaintiffs applied for employment at

defendant’s Eno Plant on September 2, 1965, their primary

motive was to test defendant’s employment practices rather

than to seek actual employment, and since there has been

no showing whatever that defendant has since employed

any females, either Negro or white, possessing plaintiffs’

education, background, skill and work experience, and

since no vacancy of any type existed on September 2, 1965,

plaintiffs are not entitled to recover back pay from Sep

tember 2, 1965, or counsel fees. The fact that no vacancy

existed on September 2, 1965, does not, however, preclude

plaintiffs from maintaining this action, since Negro females

18

were not considered for employment at that time. The

order will apply prospectively only, but will be sufficient

to effectively eliminate all discriminatory practices with

respect to future female applicants for employment.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. The Court has jurisdiction over the parties and of

the subject matter of this action.

2. This action is properly maintained as a class action

under Rule 23(a) and (b ) (2 ) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. The class includes all Negro females who are,

or who might be, affected by any racially discriminatory

policies or practices of the defendant.

3. The policies and practices of the defendant at its

Eno Plant, and its conduct pursuant thereto, with reference

to employment of Negro females, constitute a pattern and

practice of discrimination within the meaning of Title V II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

4. The defendant has intentionally engaged in, and

continues to intentionally engage in, unlawful employment

practices at its Eno Plant with respect to the employment

of Negro females.

5. The plaintiffs are entitled to enjoin the discrimina

tory employment practices herein described.

Counsel for the plaintiffs will prepare and present to

the Court an appropriate order after same has been ap

proved by counsel for the defendant as to form. Failing to

agree on the form of the order, counsel for the parties will

express themselves with reference thereto not later than

August 20, 1969.

EDW IN M. STANLEY

United States District Judge

July 29, 1969

19

N OTICE OF APPEAL BY PLAINTIFFS

[Filed 26 September 1969]

Notice is hereby given that Shirley Lea, Romona Pinnix

and Annie Tinnin, plaintiffs above named, on this 25th

day of September, 1969 hereby appeal to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit from that portion

of the Order of the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina, Greensboro, North Car

olina, entered on September 5, 1969, which denies bach

pay to plaintiffs and any member of their class and further

denies attorney fees to plaintiffs.

Dated: September 25, 1969.

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203]/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & LANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

W. G. PEARSON

336/2 East Pettigrew Street

Durham, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

ROBERT BELTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

20

N OTICE OF CROSS-APPEAL BY DEFENDANT

[Filed 29 September 1969]

Notice is hereby given that Cone Mills Corporation,

defendant above named, hereby cross-appeals to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit from all

parts, except Paragraph 8, of the final Order entered in

this action on the 8th day of September, 1969.

This the 29th day of September, 1969.

Thornton H. Brooks

440 West Market Street

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

Attorney for Defendant Cone Mills

Corporation

COM PLAIN T

[Filed 15 September 1966]

I

This is a proceeding for injunctive relief, restraining

the defendant from maintaining a policy, practice, custom

and usage of withholding, denying or attempting to with

hold or deny and depriving or attempting to deprive or

otherwise interfering with the rights of the plaintiffs and

others similarly situated to equal employment because of

race or color.

II

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. ̂1343. This is a suit in equity authorized and

21

instituted pursuant to Title V II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U. S. C. jj|2000e et seq. Jurisdiction of the

Court is invoked to secure protection of and to redress

deprivation of rights secured by Title V II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000e et seq., providing

for injunctive and other relief against racial discrimination

in employment.

III

Plaintiffs bring this action on their own behalf and on

behalf of others similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23(a)

and (b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. There

are common questions of law and fact affecting the rights

of others seeking employment opportunities without dis

crimination on the basis of race and color, who are so

numerous as to make it impracticable to bring them all

individually before the Court; the claims and defenses of

the plaintiffs are typical of the claims and defenses of the

class. The defendant has adopted rules and policies, and

has refused to eliminate same, which have deprived, and

will continue to deprive, the plaintiffs and others of the

class of their rights to equal employment opportunities

without regard to race and color as secured to them by

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C.

j!2000e.

IV

Plaintiffs, Shirley Lea, Romona Pinnix, and Annie

Tinnin, are Negro citizens of the United States and the

State of North Carolina, residing in Orange County, North

Carolina.

V

The defendant, Cone Mills Corporation, is a corpora-

22

tion, incorporated pursuant to the laws of the State of

North Carolina with power to sue and to be sued in its

corporate name and is doing business in the State of North

Carolina, including Orange County. Defendant owns and

operates textile mills and other plant facilities, one being

known as the Eno Plant, located at Hillsboro, North

Carolina.

VI

Defendant is an employer engaged in an industry which

affects commerce and employs more than one hundred

(100) employees.

V II

The defendant has pursued a policy and practice of

discriminating against plaintiffs and members of their class

in employment opportunities solely because of their race,

to wit:

A. On or about September 2, 1965, plaintiffs applied

for positions as industrial trainees at defendant’s Eno Plant

in Hillsboro, North Carolina. Plaintiffs were permitted to

fill out applications but were told that no positions were

available. Shortly thereafter, the defendant hired 13 indus

trial trainees and denied such employment to plaintiffs

solely because of their race and color.

B. The defendant hires no Negro female employees

although it does hire white female employees.

C. The defendant denies Negro employees and pros

pective employees the same opportunities for advancement

and wage earnings it accords to white employees.

23

Plaintiffs were refused employment on the basis of race

and color pursuant to defendant’s long-standing practice,

policy, custom and usage of denying and limiting employ

ment and employment opportunities of Negroes at its plant

facilities. Defendant’s denial of employment opportunities

to the plaintiffs was intended to deny and had the effect

of denying the plaintiffs equal employment opportunities

and to otherwise adversely affect their status as employees

solely because of their race and color.

IX

There is no State or local law or ordinance prohibiting

the unlawful practices complained of herein. On October

26, 1965, the plaintiffs filed complaints with the Equal

Employment Opportunities Commission alleging denial by

defendant of their rights under Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §§2000e et seq. On August 19,

1966, the Commission found reasonable cause to believe

that violations of the Act had occurred by the defendant

and advised the plaintiffs that the defendant’s compliance

with Title V II had not been accomplished within the maxi

mum period allowed to the Commission and that the plain

tiffs were entitled to maintain civil action for relief in the

United States District Court.

X

Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate or complete remedy

at law to redress the wrongs alleged, and this suit for

injunctive relief is their only means of securing adequate

relief. Plaintiffs and the class they represent are now suffer

ing and will continue to suffer irreparable injuries from

V III

24

defendant’s policy, practice, custom and usage as set forth

herein until and unless enjoined by the Court.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray that the

Court advance this cause on the docket, order a speedy

hearing at the earliest practicable date, and upon such

hearing to:

1. Grant plaintiffs and the class they represent an

injunction, enjoining the defendant, Cone Mills Corpora

tion, its agents, successors, employees, attorneys, and those

acting in concert with them and at their direction from

continuing or maintaining any policy, practice, custom and

usage of denying, abridging, withholding, conditioning,

limiting or otherwise interfering with the rights of plain

tiffs and others of their class to equal employment oppor

tunities, including equal pay, terms, conditions and priv

ileges of employment without regard to race or color.

2. Grant the plaintiffs injunctive relief, enjoining the

defendant, its agents, successors, employees, attorneys, and

those acting in concert and participation with them and at

their direction from continuing or maintaining any policy,

practice, custom and usage of denying, abridging, with

holding, conditioning, limiting or otherwise interfering with

the rights of plaintiffs and others similarly situated to

enjoy equal employment opportunities as secured by Title

V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. ^2000e

et seq.

3. Grant plaintiffs back pay from the time of defen

dant’s wrongful denial of equal employment opportunities

to the plaintiffs.

4. Allow plaintiffs their costs herein, including reason

25

able attorneys’ fees and such other additional relief as may

appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

CONRAD O. PEARSON

203/2 East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

405/2 East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

W. G. PEARSON

336 /2 East Pettigrew Street

Durham, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

LEROY D. CLARK

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

A N S W E R

[Filed 7 November 1966]

Defendant, Cone Mils Corporation, by its counsel, for

its answer to the complaint herein:

FIRST DEFENSE

The Complaint fails to state a claim against defendant

upon which relief can be granted.

26

SECOND DEFENSE

The right of action set forth in the Complaint was not

brought within the time requirements of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. The Court lacks jurisdiction over the subject

matter of the action alleged in the Complaint.

TH IRD DEFENSE

The plaintiffs have failed to exhaust their administra

tive remedies provided under the Civil Rights Act of 1964-

prior to the institution of this action, and this action should

be abated or stayed pending the determination by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission of its attempts in

that area.

FOURTH DEFENSE

The prerequisites of a class action have not been satis

fied by the plaintiffs and the Court should determine by

order that it may not be so maintained.

FIFTH DEFENSE

The plaintiffs are not entitled to maintain this suit in

equity for the action was not brought with a good-faith

desire to remedy alleged discriminatory employment prac

tices, but constitutes an attempt on the part of persons,

organizations or associations whose identity are presently

unknown to the defendant, to solicit, excite and stir up a

large number of claims of the same or similar nature against

this defendant and against other employers within the

jurisdiction of this Court. This action was instituted with

out the plaintiffs’ knowledge and is being managed and

controlled by persons or organizations other than the plain

27

tiffs, and constitutes an abuse of judicial proceedings. It

will not effectuate the purposes and policies of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 to permit the plaintiffs to maintain

this action.

SIXTH DEFENSE

(Numbered paragraphs of this Answer in this Defense

refer to correspondingly numbered paragraphs of the Com

plaint.)

I.

Paragraph I of the Complaint containing no allegation

of fact requires no response.

II.

Paragraph II of the Complaint containing no allegation

of fact requires no response.

III.

Defendant denies the allegations of Paragraph III.

IV.

Defendant admits the allegations of Paragraph IV of

the Complaint.

V.

Defendant admits the allegations of Paragraph V of

the Complaint.

VI.

Defendant admits the allegations of Paragraph V I of

the Complaint.

28

V II.

Defendant denies the allegations of Paragraph V II of

the Complaint except that it admits that on 2 September

1965 the plaintiffs applied for positions as learners at its

Eno plant, were permitted to fill out applications and were

denied positions.

VIII.

Defendant denies the allegations of Paragraph V III

of the Complaint.

IX.

Paragraph IX of the Complaint contains conclusions

of law which require no response, but it is admitted that

on October 26, 1965, the plaintiffs filed unsworn statements

with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

X .

Defendant denies the allegations of Paragraph X of

the Complaint.

WHEREFORE, defendant, Cone Mills Corporation,

having fully answered the Complaint, prays that the Com

plaint herein be dismissed with prejudice and for all other

proper relief, including costs and attorneys’ fees.

Thornton H. Brooks

Charles B. Robson, Jr.

Attorneys for Defendant, Cone

Mills Corporation

Dated: 7 November 1966

29

O R D E R

[Filed 28 June 1967]

This cause coming on to be heard before the under

signed upon motion of defendant to dismiss and for a

determination whether this cause may be prosecuted as

a class action and upon motion of plaintiffs to strike de

fendant’s demand for trial by jury and to inspect the record

of part of defendant’s answers to plaintiffs’ interrogatories

22, 24, 26 and 51, which were ordered filed under seal

with the Clerk of Court, and it appearing to the Court

upon the pleadings, exhibits, briefs and arguments of

counsel for both parties that the defendant’s motion to

dismiss and motion for determination by the Court that

this is not a proper class action should be denied. It further

appears to the Court that plaintiffs’ motion to inspect the

record of answers to interrogatories ordered to be filed

under seal should be denied and that the Court should

defer ruling upon plaintiffs’ motion to strike demand for

jury trial until final pre-trial conference;

IT IS, THEREFORE, ORDERED, ADJUDGED and

DECREED:

1. That defendant’s motion to dismiss be and the same

is hereby denied.

2. That this is a proper class action and may be prose

cuted as such pursuant to Rule 23(a), (b )(2 ) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court finding that

this is a proper class action under Rule (b )(2 ) , no notice

to members of the class need be given at this time.

Pursuant to Rule 23(c) the Court finds that the class

here involved are all Negroes who are or who might be

affected by any racially discriminatory policies or prac

tices of defendant, should the Court find any such prac

30

tices, at defendant’s Eno Plant in Hillsborough, North

Carolina.

This ruling is conditional and may be amended, modi

fied or altered at any time prior to final determination of

this cause on the merits.

3. That plaintiffs’ motion to inspect the answers of

defendant to plaintiffs’ interrogatories 22, 24, 26 and 51

which were ordered filed under seal with the Clerk of

Court be and the same is hereby denied.

4. That ruling by the Court on plaintiffs’ motion to

strike defendant’s demand for jury trial be deferred pend

ing the final pre-trial conference of this case.

This 27 day of June, 1967.

EUGENE A. GORDON

JUDGE, UNITED STATES D ISTRICT CO U RT

Approved as to form:

TH O RN TO N H. BROOKS

Counsel for Defendant

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

Counsel for Plaintiffs

S T I P U L A T I O N

[Filed 15 March 1968]

Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 22 of the Rules of

this Court, the attorneys for the parties met and conferred

on March 13, 1968, for the purposes required by said rule.

31

A pre-trial conference with the Court was held on March

15,

As a result of such conference, the parties herewith

stipulate as to their respective contentions of position to

be taken at the trial upon the merits (Part I ) ; triable

issues (Part I I ) ; a designation and agreement concerning

exhibits (Part I I I ) ; and an exchange of list of witnesses

(Part IV ), as follows:

PART I

CONTENTIONS OF PARTIES

A. At the trial of the action, the plaintiffs will contend

that:

1. Plaintiffs contend that defendant has pursued

and is presently pursuing a policy and practice of

discriminating against and limiting the employment

and promotional opportunities of plaintiffs and the

class they represent solely because of race in violation

of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

2. Plaintiffs further contend that because of said

practices:

(a ) plaintiffs were denied employment by

defendant in September 1965 because of their

race and color;

(b) Negro employees are limited to the

lowest paying jobs;

(c) the use of, and administration of em

ployment tests are not professionally developed

as required under the Act, and that the tests

32

are intended to and have the effect of dis

criminating against Negro employees.

3. Plaintiffs seek injunctive relief against such

practices and an award of costs and counsel fees.

B. At the trial of the action, the defendant will contend

that:

1. The defendant did not refuse to hire the plain

tiffs because of their race or color on 2 September

1965 in violation of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964-, as charged in writing by the plaintiffs with

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on

26 October 1965. The plaintiffs were denied employ

ment because there were no openings at that time

for persons with the qualifications, skills and abilities

possessed by the plaintiffs and as they had not pre

viously worked for the defendant nor had relatives

working there at the time.

2. The defendant has not intentionally engaged

in an unlawful employment practice as charged by

the plaintiffs; and the plaintiffs are not entitled to

equitable relief for the reason that this civil action

was not brought with a good-faith desire to remedy

alleged unlawful employment practices on the part

of the defendant, but constituted an attempt on the

part of organizations or associations to solicit, excite

and stir up a large number of claims of the same or

similar nature against this defendant and against

other employers within the jurisdiction of this Court.

The action was instituted without the plaintiffs’

knowledge and is being managed and controlled by

persons or organizations other than the plaintiffs,

and constitutes an abuse of judicial proceedings.

33

PART II

TRIABLE ISSUES

A. The triable issues as contended by the plaintiffs are

1. Whether the plaintiffs were denied employ

ment and employment opportunities because of their

race and color in violation of Title V II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.

2. Whether in light of defendant’s former prac

tice of refusing to accept applictaions from Negro

women and the refusal to do more than limited hiring

of Negro women unlawfully discriminates against

Negro employees in violation of Title V II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964.

3. Whether in limiting the opportunity of Ne

groes to transfer or be promoted to other job classi

fications the defendant discriminates against Negro

employees in violation of Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

4. Whether the defendant’s policy of preferen

tial hiring of friends and relatives of current em

ployees, upon such employees referral and recom

mendation, is discriminatory per se against Negroes

in view of the racial imbalance and mal-distribution

through the pay grades in the defendant’s plant and

therefore in violation of Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

5. Whether the tests administered by the Cone

Mills Corporation, which were instituted shortly after

the filing of the complaints by the plaintiffs, have

been scientifically validated on established norms by

trained professionals in the area of testing after being

34

fully apprised as to the requirements of the positions

in question at the Cone Mills Corporation and are

administered by persons trained in the art or science

of testing.

6. Whether there is a high positive correlation

between scores obtained on the test and actual per

formance on the job.

7. Whether the requirement that Negro employ

ees and potential employees are required to make

an acceptable score on the Oral Directions Test,

Mechanical Aptitude Test and the Manual Dex

terity Test unlawfully discriminates against Negro

employees and potential employees in violation of

Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in light of

the fact that defendant has hired and promoted

white employees who have not taken the test since

the enactment and effective date of Title VII.

B. The triable issues as contended by the defendant are

the same as set forth in its statement of contentions, pages

2-3, supra.

M EM O RAN D U M ORDER

[Filed 23 May 1968]

A final pre-trial conference was held before the Court

on March 15, 1968, at which time the parties submitted a

signed stipulation to the Court for the entry of a final pre

trial order. It appears from Part II of the stipulation that

the parties were unable to agree upon the triable issues

and that same are in dispute.

In the subject case the plaintiffs’ rights arise solely by

reason of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq.). Those cases involving discrimina

tion in public schools, hospital, and similar public facilities

are not applicable, as there is no allegation or issue arising

concerning the violation of constitutional rights as was in

volved in the public school cases, among others.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 with some detail sets out

specific steps that a complainant must take before action

is permitted in the District Court. An aggrieved person

must first file with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission a written statement under oath setting forth

the facts contended to constitute a violation of the Act.

A copy of the charge must be furnished the employer or

agency against whom the complainant seeks relief. Title

V II, { 706(a) of the Act (42 U.S.C. $ 2000e-5). In the

subject case, the plaintiffs in their respective written state

ments filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission state:

“ I applied for work with the above named employer

on September 2, 1965, and was refused work on September

2, 1965. I applied for a position as ajn] industrial trainee.

My qualifications for the position are: . . . I think that I

was refused work because of my race or color. I went to the

above named mill on the above date and applied for a

job as an industrial trainee. I filled out an application, and

was informed that there were no openings. We were also

informed that all workers had been working for 20 years.

There are no Negroes hired in this mill.” (emphasis added)

It is provided by the Act that the Commission will

investigate the charge and if there is reasonable cause to

believe that the charge is true the Commission will “ en

deavor to eliminate any such alleged unlawful employment

practice by informal methods of conference, conciliation

and persuasion.” The Commission in the subject case found

the following:

“ 1. The Commission finds reasonable cause to be-

36

lieve the charges by applicants for industrial

trainee positions that they were denied con

sideration for employment because of their

race.”

In summarizing the charge in each complaint, the Com

mission states that the “ [clharging parties allege that they

were denied employment because of their race (Negro).”

Thus, it is clear that there has never been a charge before

the Commission by the plaintiffs, or either of them, con

tending that the defendant has violated the Act in connec

tion with promotions, transfers, testing procedures or other

wise except in its denial of employment by reason of race.

If plaintiffs know or have been advised of violations

not heretofore the subject of a charge before the Commis

sion, the Commission should be afforded an opportunity to

investigate the charges, hear the defendant’s viewpoint, and

if violations are believed to exist, attempt to eliminate the

offensive practices before the extreme remedy of court

action ensues. This procedure is clearly contemplated by

the Act.

After giving consideration to the pleadings, the briefs

of counsel, argument of counsel, and the entire official file,

the Court is of the opinion that the triable issues are only

those which reasonably relate to the charges filed by the

plaintiffs with the Commission.

IT IS, THEREFORE, ORDERED:

1. The stipulation of the parties filed with the Court

on March 15, 1968, constitutes the final pre-trial

order in this action and will control the subsequent

course of this action unless modified by consent of

the parties and the Court, or by order of the Court,

to prevent manifest injustice.

37

2. The contested issues to be tried by the Court are

substantially the narrower issues as set forth by the

defendant on page 4 of the stipulation, rather than

the broader issues as set forth by the plaintiffs on

pages 3 and 4. In general, the triable issues are only

those which reasonably relate to the charges filed

by the plaintiffs with the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, and which it has investigated

and notified the aggrieved parties and the defendant

of its determination.

3. This order does not purport to rule on the admis

sibility of any evidence at the trial, as such ruling

will be made as the occasion requires.

EUGENE A. GORDON

United States District Judge

May 22, 1968

PLAINTIFF EXHIBIT 1

PL. EX. 1

TO : Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

CO M PLAIN T OF UNFAIR EM PLOYM ENT

PRACTICES UNDER THE 1964 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT

TITLE V II

DATE: Sept. 2, 1965 Age: 24

M y name is Mrs. Shirley Lea. I am a Negro citizen of the

United States and a resident of North Carolina. M y address

is Rt. 1, Box 136A, Cedar Grove, N. C. M y complaint is

38

against Cone Mills Inc., whose address is Hillsboro, N. C.

I applied for work with the above named employer on

Sept. 2, 1965, and was refused work on Sept. 2, 1965. I

applied for a position as a industrial trainee. M y quali

fications for the position are (State education, training

and/or experience.) High school graduate.

I think that I was refused work because of my race or

color. (State briefly the circumstances and/or reasons upon

which the complaint is based. Such things as known, stated

or written racial employment policies, either total or par

tial, can be included.)

I went to the above named mill on the above date and

applied for a job as an industrial trainee. I filled out an

application, and was informed that there were no openings.

We were also informed that all workers had been working

for 20 years. There are no Negroes hired in this mill.

MRS. SHIRLEY LEA

Signature

I, P. R. WEAVER, a Notary Public in and for the County

of Orange, in the State of North Carolina, do certify that

SHIRLEY LEA personally appeared before me in my

County aforesaid and subscribed and acknowledged the

same this 2nd day of September, 1965.

P. R. WEAVER

Notary Public

SEAL

M y Commission Expires the 4th day of April, 1967.

39

PLAINTIFF EXHIBIT 4

PL. EX. 4

EQUAL EM PLOYM ENT O PPORTU N ITY

COM M ISSION

W ASHINGTON, D. C. 20506

DECISION

Magdalene Bradshaw

Ida Fuller

Romona Pinnix

Shirley Lea

Annie Tinney

Lizza Bradshaw

Case No. 5-10-2251

5-10-2252

5-10-2253

5-10-2254

5-10-2255

5-10-2256

Charging Parties (Applicants for “ industrial trainee”

jobs)

Inise Corbett

Laura Jean Battle

Caroline Corbett

Annie Torain

5-10-2257

5-10-2258

5-10-2259

5-10-2260

Charging Parties (Applicants for “ secretarial” jobs)

vs.

Cone Mills Corporation

Eno Plant

Hillsboro, North Carolina

Date of alleged violations: September 2, 1965

Filing Date: October 26, 1965

Date of service of charges: November 24 and 26, 1965

(by mail)

SUM M ARY OF CHARGES

Charging parties allege that they were denied employment

40

because of their race (Negro) in that:

1. Applicants for industrial trainee (5-10-2251 thru

5-10-2256)

a. were permitted to fill out applications but were

told there were no openings;

b. were told all employees had worked at respon

dent plant for 20 years.

2. Applicants for secretarial positions (5-10-2257 thru

5-10-2260)

a. were refused applications and were told there

were no openings;

Case Nos. 5-10-2251 thru 5-10-2256

(Applicants for “ industrial trainee” jobs)

Case Nos. 5-10-2257 thru 5-10-2260

(Applicants for “ secretarial” jobs)

SU M M ARY OF CHARGES (continued)

b. were referred to the Greensboro plant;

c. were told that respondent had only two secre

taries, who had worked there for 12 and 19 years.

3. All industrial trainee applicants allege there are no

Negroes working in respondent mill.

4. All secretarial applicants allege there are no Negro

secretaries in respondent company.

SU M M ARY OF IN VESTIGATION

The respondent mill is within the jurisdiction of Title V II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The mailed interrogatory and subsequent investigation

indicated:

1. That charging parties who applied for jobs as in

41

dustrial trainees were discriminated against because

of their race:

a. Subsequent to charging parties applications, re

spondent hired 13 industrial trainees—-four white

males, eight Negro males and one white female.

b. None of the charging parties were hired. Re

spondent has never hired a Negro female. Re

spondent has hired white females.

2. That charging parties’ allegation that no Negroes

are hired in the mill is without substance. There

are 44 Negro males in respondent’s employ, thirty-

one of whom are unskilled laborers. There are, how

ever, no Negro females.

3. That charging parties who applied for secretarial

positions were not denied employment because of

their race.

a. There are only two secretarial positions at re

spondent plant;

Case Nos. 5-10-2251 thru 5-10-2256

(Applicants for “ industrial trainee” jobs)

Case Nos. 5-10-2257 thru 5-10-2260

(Applicants for “ secretarial” jobs)

SUM M ARY OF INVESTIGATION (continued)

b. There were no openings at the time of applica

tion, nor subsequent to that time;

c. The two incumbents of these secretarial positions

(both white) have held these jobs for 12 and 19

years respectively;

d. There are no Negro secretaries, nor have there

ever been, in respondent’s employ.

42

FINDING

1. The Commission finds reasonable cause to believe

the charges by applicants for industrial trainee posi

tions that they were denied consideration for employ

ment because of their race.

2. The Commission finds no reasonable cause to believe

the charges by applicants for secretarial positions

that they were denied employment because of their

race.

For the Commission

John H. Royer, Jr., Secretary

Date: June 24, 1966

DEFENDANT EXHIBIT 1

PERSONNEL POLICY M ANUAL

CONE M ILLS CO RPORATIO N

H OU RLY EMPLOYEES

SLTBJECT: Employment

PAGE 1 of 2

DATE April 1, 1963

REVISED

Policy: The company recognizes a continuing need to ob

tain and retain highly competent personnel. It is there

fore the company’s policy to recruit and select applicants

for employment on the basis of their ability to perform

satisfactorily the jobs currently available, and their

capacity to be up-graded in accordance with the com

pany’s policies, without regard to race, creed, color, or

national origin.

To assure the recruitment and selection of competent

43

people, the company has established and will maintain

employment standards consistent with its needs. The

employment standards are based on tests and techniques

widely accepted for insuring the objective and impartial

consideration of employee applicants.

Procedure:

1. job Applicants

When the need arises to fill vacancies or newly created

positions with persons not currently at work in the

organization, first consideration will be given to quali-

field applicants in the following groups:

(1) Laid-off employees.

(2) Former employees.

(3) People residing in or near the communities in which

our operations are located.

In the event a qualified candidate cannot be found in

these groups, other candidates are considered.

Persons seeking employment are to make application

at the personnel or employment office.

2. Hiring Procedure

Details of the hiring procedure are set forth in the

“ Manual of Employment Practices” used by the per

sonnel manager or employment manager as a guide.

Briefly, the steps followed in the hiring procedure are:

(1) The applicant fills out the application form, is

interviewed by the employment or personnel man

ager and is given aptitude tests and visual tests.

44

PERSONNEL POLICY M ANUAL

CONE M ILLS CO RPORATIO N

H OU RLY EMPLOYEES

SUBJECT: Employment

PAGE 2 of 2

DATE April 1, 1963

REVISED

(2) The applicant’s work history is investigated, and

if found satisfactory, the applicant is interviewed

by appropriate members of management.

(3) Applicants approved by management next take a

physical examination.

(4) Candidates found acceptable on all counts are

offered employment.

3. Employment of Relatives

A person may not be employed for work in a depart

ment in which his close relative is a supervisor or de

partment head. “ Close relative” means mother, father,

brother, sister, husband, wife, son, daughter, niece,

nephew, aunt, uncle, or first cousin, either in-law or

by blood.

4. Employment of the Handicapped

Physically handicapped persons may be employed when

the handicap does not interfere with other employees, or

with the requirements of the job, or with the welfare

of the handicapped person.

5. Legal Requirements

All requirements of state and federal law are met, and

45

these requirements are posted on all bulletin boards

where such posting is required.

6. Induction of New Employees

Following employment, employees are inducted in ac

cordance with a procedure described in the company

policy entitled, “ Induction of New Employees.”

7. Probationary Period

The first six weeks of employment are probationary

and during this period employees may be terminated

for any reason.

46

(1)

UNITED STATES D ISTRICT CO U RT

MIDDLE D ISTRICT OF N O RTH CAROLINA

DURH AM DIVISION

)

SHIRLEY LEA, RO M O N A PINNIX, )

and ANNIE TINNIN, )

Plaintiffs, )

) Civil Action

v- )

) No. C-176-D-66

CONE M ILLS CORPORATION , )

a corporation, )

Defendant.

Greensboro, North Carolina

September 17, 1968

9:30 o ’clock A. M.

APPEARANCES:

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS, ESQ.,

and

ROBERT BELTON, ESQ.,

appearing on behalf of the Plaintiffs.

M cLe n d o n , b r i m , b r o o k s , p i e r c e &

DANIELS, by

TH O RN TO N H. BROOKS, ESQ., and

C. ALLEN FOSTER, E SQ , of counsel,

appearing on behalf of the Defendant.

* *

47

The above-entitled cause came on for trial in the United

States Courtroom, United States Courthouse Building,

Greensboro, North Carolina, before the Honorable EDWIN

M. STANLEY, Judge Presiding, on the 17th day of

September, 1968, commencing at 9:30 o’clock A. M.

* « t-

(23) SHIRLEY ANN LEA

one of the Plaintiffs herein, was called as a witness in her

own behalf and, being first duly sworn, was examined and

testified on her oath as follows:

DIRECT EXAM IN ATIO N

Q (By Mr. Chambers) Would you state your name,

please?

A Mrs. Shirley Ann Lea.

Q Mrs. Lea, you are one of the plaintiffs in this proceed

ing?

A Yes.

Q Calling your attention to the date September 2, 1965,

were you employed anywhere at that time?

A No.

Q Were you seeking employment at that time?

A Yes.

Q Would you give the Court your address?

A My permanent—

Q Yes.

A Route 1, Box 220-C, Efland, N. C.

THE C O U R T : Is that where you lived then?

THE WITNESS: No.

48

O (By Mr. Chambers) What was your address at the time

in September of ’65?

A Cedar Grove Route.

(24) Q Is that in Orange County or Alamance?

A Orange.

Q How far is that from the Eno Plant?

A I ’m not sure, but I think it’s about between 12 and 14

miles.

Q Were you seeking employment on September 2, 1965?

A Yes.

Q Did you go to the defendant’s plant, the Eno Plant, to

seek employment?

A Yes.

Q Had you been to that plant before?

A Yes.

Q Would you give the first time that you went to the

plant to apply for employment?

A I can’t remember the exact date or month. I don’t

remember.

THE COU RT: Where is this Eno Plant?

THE WITNESS: Hillsborough.

THE COU RT: At Hillsborough?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

THE COU RT: Is that the date you went there,

September 2nd?

THE WITNESS: Something like that.

THE COU RT: All right.

O (By Mr. Chambers) Do you recall whether it was in

1965 (25) that you went there the first time?

49

A I ’m not sure, but I think it was. I can’t be positive.

Q Did you go there alone the first time?

A No, I don’ t think so.

Q Who did you go with the first time?

A I believe Mrs. Romona Pinnix. I don’t know. There

might have been someone else with us. There were some

ladies together. I don’t know.

O What were you told at that time when you went there

to apply for employment?

A That there weren't any openings.

O Did you talk to Mr. King?

A No.

O Did you get a chance to fill out an application form?

A I don’t remember if I filled out one then.

Q And you went to the plant a second time to apply for

employment? Was September 1965 the second time that

you had been there to apply for employment?

A Yes.