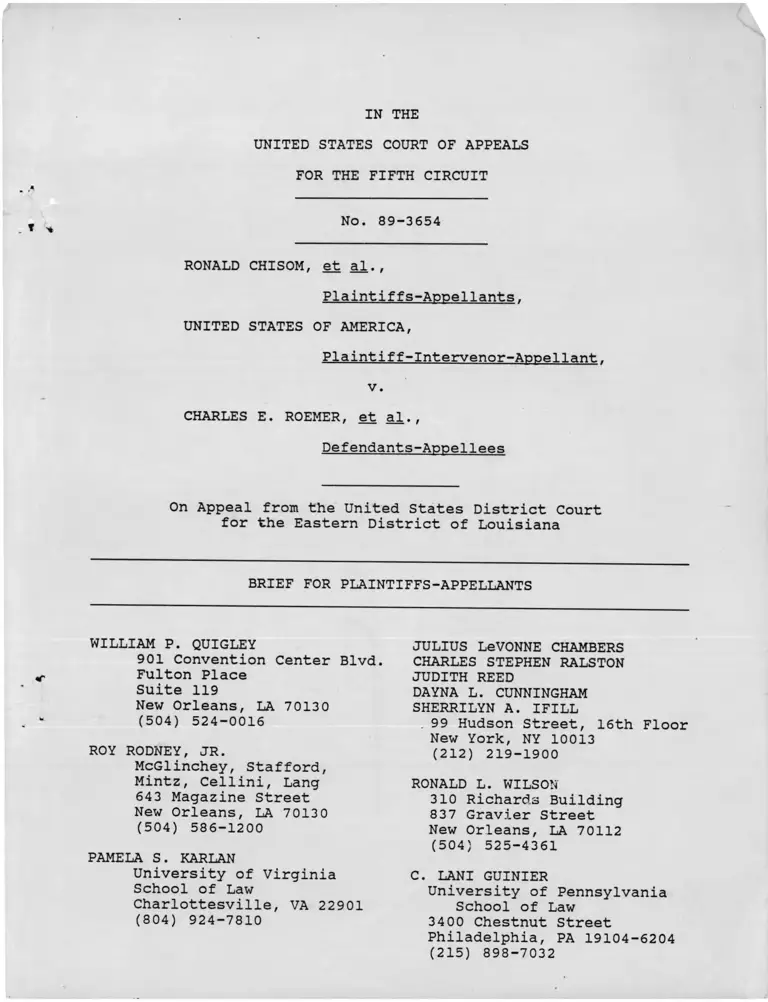

Chisom v. Roemer Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 18, 1989

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chisom v. Roemer Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1989. 597c1b6e-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d29d3298-d6b8-403d-a12d-210644570be9/chisom-v-roemer-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant.

v.

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al. ,

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

McGlinchey, Stafford,

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S . KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JUDITH REED

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

. 99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. WILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LANI GUINIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6204

(215) 898-7032

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel certifies that the following

listed person's have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that the Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

1. The plaintiffs in this action: Ronald Chisom, Marie

Bookman, Walter Willard, Marc Morial, Henry Dillon III, and

Louisiana Voter Registration/Education Crusade, a non-profit

corporation.

2. The attorneys who represented the plaintiffs: Julius L.

Chambers, Judith Reed, Sherrilyn A. Ifill, of the NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.; Pamela S. Karlan; C. Lani

Guinier; William P. Quiqley; Roy Rodney of the law firm of

McGlinchey, Stafford, Mintz, Cellini, Lang? and Ronald L. Wilson.

3. The attorneys who represented the plaintiff-intervenor

United States of America: Gerald W. Jones, Steven H. Rosenbaum,

Robert S. Berman.

4. The defendants in this action: Charles Roemer, Governor

of the State of Louisiana; W. Fox McKeithen, Louisiana Secretary

of State; and Jerry M. Fowler, Commissioner of Elections of the

State of Louisiana.

5. The attorneys who represented the defendants: Robert G.

Pugh; Kendall Vick; Moise W. Dennery of the law firm of Lemle,

Kelleher, Kohlmyer, Dennery, Hunley, Frilot; Blake Arata; M. Truman

Woodward, Jr. of the law firm of Milling, Benson, Woodward,

Hillyer, Pierson, Miller; and A.R. Christovich of the law firm of

Christovich, Kearney.

6. The attorneys who represented the defendants-intervenors:

George M. Strickler of the law firm of LeBlanc, Strickler,

Woolhandler; Peter J. Butler of the law firm of Sessions, Fishman,

Voisfontaine, Nathan, Winn, Butler, Barkley; and Moon Landrieu.

Attorney of record for plaintiffs-appellants

11

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs-appellants hereby request that this case be set for

oral argument. This appeal presents several distinct and important

legal issues. Although the resolution of many of the issues on

appeal should not be difficult, given that the parties stipulated

to virtually all the relevant facts, and the issues are governed

by settled Supreme Court and Fifth Circuit precedent, we believe

that oral argument would be valuable to the Court.

i n

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS ............................ i

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT ............................ iii

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ..................................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED ............................ 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .......................................... 1

I. Proceedings Below ................................... 1

II. Statement of F a c t s ................................. 3

A. The Louisiana Supreme Court ................. 3

1. The Method of Selecting the Louisiana

Supreme Court ............................ 3

2. Configuration of the Current Supreme Court

Districts ................................. 4

B. Facts Related to the "Gingles Factors" . . . . 5

1. Black Population Size and Geographic

Compactness in Orleans Parish ............. 6

2. Political Cohesion of Blacks in Orleans

Parish . ................................. 7

3. Bloc Voting by White Voters in Elections

within the First District ................. 8

C. The "Senate Report" Factors ................. 10

1. A History of Official Discrimination . . 10

2. Racial Polarization in Voting ........... 11

3. The Use of "Enhancing" D e v i c e s ............. 12

4. Candidate Slating Process ............... 12

5. Depressed Socioeconomic S t a t u s ....... 13-

6. The Role of Race in Political Campaigns . 14

7. Minority Electoral Success .............. 15

xv

8 . Tenuousness 16

D. The District Court's Findings of "Ultimate"

F a c t ............................................16

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................................IV

A R G U M E N T ......................................................... 20

I. The District Court Misinterpreted The First Gingles

F a c t o r .................................................20

A. The Applicable Legal Standard .................. 20

B. The Evidence in this C a s e ....................22

C. The District Court Erred in Rejecting a Single-

Parish District at the Liability Phase of

T r i a l ............................................ 24

II. The District Court Made Critical Errors of Fact and

Law In Its Analysis Of Racially Polarized Voting . 26

A. The Applicable Legal S t a n d a r d ................. 26

1. The Particular Salience of Elections

Involving Both Black and White

C a n d i d a t e s ................................. 27

2. The Legal Inconsequentially of Voting

Patterns in Elections Involving Only White

C a n d i d a t e s ................................. 29

3. The Level of Black Support for Black

Candidates Necessary to Prove Political

Cohesiveness ............................ 29

4. The Meaning of Legally Significant White

Bloc V o t i n g ................................. 30

5. The Relevance of Voting Behavior Within

Majority-Black Subsections of Majority-

White Districts............................. 31

B. The District Court's Errors in this Case . . . 34

1. The District Court Wrongly Ignored the

Inability of Black Voters to Elect Black

Candidates to the Louisiana Supreme

C o u r t ....................-.......... .. 34

2. The District Court Wrongly Relied on

Contests Involving Only White

C a n d i d a t e s ...............................37

v

3. The District Court Used an Improper

Standard for Assessing Black Political

Cohesiveness ............................ 38

4. There Was No Basis Whatsoever for the

District Court's Finding of Legally

Sufficient White Crossover Support for

Black C a n d i d a t e s ........................... 39

5. The District Court's Reliance on Black

Electoral Success Within Orleans Parish

Was Misplaced............................... 40

C. The District Court's View of Judicial

E l e c t i o n s ........................................ 43

III. The District Court Made Factual And Legal Errors

With Regard To The Remaining Senate Factors . . . . 45

Historical Discrimination and Socioeconomic

Disparities................................. 46

Racial Appeals in Campaigns .................. 47

Enhancing Factors ............. . . . . . . . 48

Minority Electoral Success .................... 48

T e n u o u s n e s s ......................................49

C O N C L U S I O N ....................................................... 49

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, N.C., 470 U.S. 564 . . 45

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) . . . . . 14

Baldwin v. Alabama, 472 U.S. 372 (1985) . . . . . 10

Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of Inc, 466 U.S. 485 (1984) . 45

Brewer v. Ham, 876 F.2d 448 (5th Cir. 1989) . . . 18, 21, 22, 32

Brown V. Thompson, 462 U.S. 835 ( 1 9 8 3 ) .................. 23

Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240 (5th Cir. 1988) . Passim

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La. 1987) . . 2, 43

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La. 1988) . . 2, 3, 9

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988),

rehearing and rehearing en banc denied. . . . 2 , 28, 43

Chisom v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988) rehearing

and rehearing en banc d e n i e d ...........................2, 3

Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna, 834 F.2d

496 (5th Cir. 1987) cert, denied. 106 L. Ed. 2d 564

(1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . . Passim

Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna,

636 F. Supp. 1113 (E.D. La. 1986), aff'd 834 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1987) cert, denied. 106 L. Ed. 2d 564 (1989) 36

Clark v. Edwards, Civ. Ac. No. 86-435

(M.D. La. Aug. 15, 1 9 8 8 ) ............................... 45

Dillard v. Baldwin County Board of Education, 686 F. Supp.

1459 (M.D. Ala. 1 9 8 8 ) ................................... 21

East Jefferson Coalition for Leadership and Development v.

Jefferson Parish, 691 F. Supp. 991

(E.D. La. 1 9 8 8 ) ...................................... 11, 12, 33-

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 ( 1 9 7 3 ) .................. 21

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984) 33

Long v. Gremillon, Civ. Suit 142, 389, 9th Jud. Dist.

vii

Rapides Par. (Oct. 14, 1 9 8 6 ) ........................... 11, 47

LULAC V. Mattox, civ. Ac. No. 88-CA-154

(W.D. Tex-. November 15, 1989) . . . . . . . 45

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983) . . 11, 25, 40

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987) . . 45

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037 (11th Cir. 1984) . . 36

Rangel v. Mattox, Civ. Ac. No. B-88-053

(S.D. Tex. July 28, 1989) ............................... 45

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 ( 1 9 8 2 ) ...................... 32

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 ( 1 9 6 8 ) .................. 15

United States v. State of Louisiana, 692 F. Supp. 642

(E.D. La 1988) . . . . . . . . . . 13

United States v. State of Louisiana, Civil Action 80-3300

(W.D. Tex. Nov. 15, 1989) ............................ 14

Velasquez v. City of Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1984) 47

Wells v. Edwards-, 347 F. Supp. 453 (E.D. La. 1972) , aff'd

per curiam. 409 U.S. 1095 ( 1 9 7 3 ) ...................... 10, 23

Westwego Citizens for Better Government v. City of

Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989) . . 18, 26, 46, 49

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978) .................. 11, 21

STATUTES, CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 1 ............................................ !

30 Fed. Reg. 9897 ( 1 9 6 5 ) ................................ 10, 11

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 . 2, 19

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 7 3 b ............................................ ... 3 , 27

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000h-2 . . . . 2

La. Const, art. V § 22(b) . . . . . . . . . 4

House Report No. 96-227, 97th Cong. 1st Sess. (1981) . . 28

Senate Report No. 97-417, 97th Cong. 2d Sess. (1982) . 10, 11, 13

viii

U.S. Const. XIV

20, 27

2

U.S. Const. XV ........................................MISCELLANEOUS

B. Grofman, Representation and Redistrictinq’ Issues 58

L. Guinier, "Keeping The Faith: Black Voters in the

Post-Reagan Era," Harv. C.R.C.-L.L. Rev. 393 (1989)

New York Times, November 8, 1989 . . • _ •

P. DuBois, From Ballot to Bench: Judicial Elections and the

Quest for Accountability (1980) ......................

Volcansek, "The Effects of Judicial-Selection Reform: What

We Know and What We Do Not" in The Analysis of Judicial

Reform 85 (P. DuBois ed. 1982) . . . . . .

2

28

28

44

44

44

ix

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The district court entered final judgment dismissing the

claims of plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenor, United States, on

September 14, 1989. Plaintiffs-appellants filed a notice of appeal

on September 25, 1989. This Court's jurisdiction is invoked under

28 U.S.C. § 1291.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Did the district court err in holding that the black

population was not sufficiently large and geographically compact

to constitute a majority in a single-member district, when, as the

court found, (a) the overwhelming majority of black registered

voters in the challenged at-large district reside in a definable

subdistrict, Orleans Parish;- (b) a -district made up of Orleans

Parish only would contain a black registered voter majority; and

(c) minority voters in a district made up of Orleans Parish only

would possess the potential to elect candidates of their choice?

2. Did the district court err in holding that there was no

significant racially polarized voting in the challenged district,

where black voters support black candidates and white voters

support white candidates and whites consistently vote as a bloc to

defeat black candidates?

3. Did the district court err in failing to apply the

totality of circumstances test with regard to the relevant Senate

Factors?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Proceedings Below

This voting rights action was commenced in September 1986 by

five black individuals registered to vote in Orleans Parish,

Louisiana, and a nonprofit corporation active in the field of

voting rights whose members are black registered voters in Orleans

Parish.1 Plaintiffs sought to represent a class consisting of all

black registered voters in Orleans Parish.

The complaint alleged that the system under which Justices of

the Louisiana Supreme Court are elected in the First Supreme Court

district ("First District") impermissibly dilutes the voting

strength of the black voters of Orleans Parish, in violation of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 and the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. Amend. Compl. at 1. Defendants moved to dismiss the

complaint for failure to state either a statutory or a

constitutional claim. Dkt. Nr. 18. On May 1, 1987, the district

court (Charles Schwartz, Jr., J.), ruled that section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act does not apply to the election of judges and that

plaintiffs had failed to plead an intent to discriminate with

sufficient specificity to support their constitutional claims.

Chisom v. Edwards. 659 F.Supp. 183 (E.D. La. 1987). In its June

8, 1987, judgment, the court dismissed plaintiffs' complaint. Dkt.

Nr. 25. This Court reversed that judgment and remanded for further

proceedings. Chisom v. Edwards. 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988),

rehearing and rehearing en banc denied, Chisom v. Roemer. 853 F.2d.

1186 (5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied. 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988).

On remand, and after a hearing, the court granted plaintiffs'

motion to enjoin the election for a Supreme Court seat in the First

District scheduled for October 1, 1988. The preliminary injunction

On August 8, 1988, the United States' motion to intervene

as a party plaintiff pursuant to Title XI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C § 2000h-2, was granted.

2

was granted. Dkt. Nr. 43; 52; Chisom v. Edwards. 690 F. Supp. 1524

(E.D. La. 1988). This Court vacated the injunction. Chisom v.

Roemer. 853 F.2d 1186. Shortly thereafter, plaintiffs moved for

summary judgment, and that motion was denied. Dkt. Nr. 69. The

matter was tried to the court on April 5, 1989. After issuing

findings of fact and conclusions of law, the court entered judgment

in favor of all defendants. Dkt. Nr. 110. This appeal followed.

II. Statement of Facts

The seven justices of the Louisiana Supreme Court are elected

from six geographically defined judicial districts. Five of the

justices are elected from single-member districts. Two are elected

from the lone multimember district, the First District. The

plaintiffs in this case are black registered voters who reside in

Orleans Parish, one of the four parishes in the First District.

They claim that their inclusion within the First District denies

them an equal opportunity to elect a Justice to the Louisiana

Supreme Court, in violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973b.

As this brief sets out below, the basic evidence supporting

plaintiffs' claim was uncontested at trial2; this evidence is set

out in Parts A through C of this Section. In Part D, we summarize

the district court's interpretation of the evidence.

A. The Louisiana Supreme Court

1. The Method of Selecting the Louisiana Supreme Court

Justices must reside in the district from which they seek

election. Only voters living in a particular district are eligible

2 Indeed, most of the evidence was admitted in the form of

stipulations between the parties.

3

to vote in its judicial elections. RE 13, 14. Candidates for

seats on the Supreme Court run in a preferential primary. If no

single candidate receives a majority of votes in the preferential

primary, the State's majority vote requirement dictates that the

two candidates with the most votes in the primary compete in a

general election for the Supreme Court. RE 14. Elections for the

two Supreme Court positions from the First District are staggered,

Id. , thus precluding voters from single-shot voting.

No black person has been elected to the Louisiana Supreme

Court in this century. The only black person to serve on the

Louisiana Supreme Court in this century, was appointed to a vacancy

on the court for a period of 17 days during November 1979. Pre-

Trial Order, Stipulations 46-47 (hereafter "Stip.")3 Under the

Louisiana Constitution, he was not permitted to seek election to

the seat for which he had been appointed. See La. Const, art. V

§ 22(b).

2. Configuration of the Current Supreme Court Districts

The five single-member Supreme Court election districts

consist of between eleven and fifteen whole parishes each. The

First District consists of four whole parishes, Orleans Parish and

three suburban parishes — St. Bernard, Plaquemines and Jefferson

Parishes.4 RE 14. The First District is the most populous

election district in the State of Louisiana. Stip. 82.

3 For the Court's convenience, the parties' stipulations of

fact are included in the record excerpts filed with this brief at

RE 66 to 104.

4 No parish lines are cut by the election districts for the

Supreme Court. RE at 14.

4

The Louisiana Constitution does not require that the election

districts for the Supreme Court be apportioned equally by

population. RE 14. Indeed, the total population deviation between

districts is 74.95%. See RE 17 (comparinq Fourth and Fifth

Districts).

Although blacks constitute 29% of the state's population, none

of the six Supreme Court election districts are majority black in

either total population in the number of registered voters. RE 16.

Although the First District is majority white in both total

population and in the number of registered voters, Orleans Parish

(which contains more than half of the First District's total

population) is majority black in both total population and

registered voter population.5 RE 15. The three other parishes are

each majority white in total population and registered voter

population. RE 15, 16.

B. Facts Related to the "Gingles Factors"

In Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), the Supreme Court

identified three critical elements of a section 2 challenge to the

use of multimember election districts:

First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate

that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact

to constitute a majority in a single-member district.

. . . Second, the minority group must be able to show

that it is politically cohesive. . . . Third, the

minority must be able to demonstrate that the white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it — in

the absence of special circumstances, such as minority

candidate running unopposed, . . . — usually to defeat

the minority's preferred candidate.

5 As of March 3, 1988, 81.2% of black registered voters within

the First District resided within Orleans Parish. RE at 15.

5

Id. at 50-51. In this case, the stipulations and uncontradicted

evidence squarely establish the existence of each Gingles

circumstance.

1. Black Population Size and Geographic Compactness in

Orleans Parish

At trial, plaintiffs presented two plausible divisions of the

existing First District that would result in the creation of a

single-member district that is majority black in registered voter

population. First, plaintiffs showed that the current district

could be divided into two districts — an Orleans Parish-only

district and a suburban district containing Jefferson, St. Bernard,

and Plaquemines Parishes. PX 2 . Each of these districts would have

a larger population than the current Fourth District and would have

a population roughly the size of the current Sixth District.

Compare RE 16 (table showing that Orleans district would have total

population of 557,515, leaving a suburban district with a

population of 544,738) with RE 15 (table showing total populations

of existing districts). They would thus fit comfortably within the

deviations currently countenanced by Louisiana's practice.6

Second, plaintiffs and the United States presented evidence

that a majority-black, single-member district with a smaller

population deviation could be obtained by adding contiguous,

predominantly black areas of Jefferson Parish to Orleans Parish.

See United States' Exhibit 14. According to the 1980 Census, this

district would have a population deviation from the ideal district

of 4.4%.

6 Both districts also would comport with the State's practice

of not dividing parishes between or among Supreme Court districts

and of using single-member election districts.

6

2 . Political Cohesion of Blacks in Orleans Parish

The parties here stipulated to the reliability of the two

techniques, approved by the Gingles Court, for determining voting

behavior and minority political cohesion: extreme case analysis and

bivariate ecological regression analysis. 478 U.S. at 52-53; see

also id. at 53 n. 20 & 55 (citing with approval the methodological

work of plaintiffs' expert in this case, Dr. Richard L. Engstrom).

Stip. 78.

In this case, experts for both sides, as well as all lay

witnesses who testified, agreed that in both judicial and

nonjudicial elections, black voters within Orleans Parish were

politically cohesive.7 With regard to nonjudicial elections, the

district court specifically found that blacks within Orleans Parish

had won a number of parishwide offices "due to large support by the

black community." RE 34. Black candidates testified that they

received the majority of their electoral support from black

voters.8

7 The evidence of black political cohesion was particularly

strong in elections in which both black and white candidates

competed. See, e.g.. RE 55 (based on Stip. 78) (showing that on

average, black candidates were supported by 80% of black voters).

8 See e.g.. Testimony of Melvin Zeno, Tr. at 75; Testimony of

Anderson Council, Tr. at 88; Testimony of Edwin Lombard, Tr. at

103. Black candidates also testified that the bulk of their

campaign contributions came from black organizations and black

citizens. See e.g.. Testimony of Revius Ortique, Tr. at 35;

Testimony of Melvin Zeno, Tr. at 80; Testimony of Anderson Council,

Tr. at 97.

7

3. Bloc Voting by White Voters in Elections within the

First District

In almost every case in which a black candidate opposed a white

candidate, the black candidate was the candidate of choice of black

voters. See RE 55.

Table 3 of the Appendix to the district court's opinion

reports the voting behavior of white and black voters within the

First District in the 34 recent judicial elections in which both

black and white candidates competed. The figures reveal a stark

fact: although black voters supported the black candidate in 29

of the 34 elections, white voters never cast even a simple

plurality of their votes for any black candidate. They

overwhelmingly preferred the white candidate in every election.

The differential support of black candidates is staggering.

Within Orleans Parish, black support for black candidates in

contested elections since 1978 has averaged 80.%. White support for

those same candidates has averaged only 17%. U.S. Ex. 49 at 11.

The difference in Jefferson Parish is even greater. There, the

average support for the black candidates among black voters was

90%, while among white voters it was only 10%. Id. The same

racial polarization is revealed by an analysis of "exogenous"

elections — elections other than the elections challenged here.

In the 1987 Secretary of State election in which three blacks were

among ten candidates on the ballot, black voters in the First

District cast a majority of their votes for black candidate Edwin

Lombard. Tr. at 12 0, PX 1. White voters, however, cast a majority

of their votes for white candidates. See Stip. 81. Similarly, in

the 1988 Democratic Presidential Primary, the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson

8

received approximately 96.9% of the votes cast by black voters in

the First District, but only 3.5% of votes cast by whites in the

First District. See PX 1.

Uncontested lay testimony supports the conclusion that white

voters within the First District, particularly whites in the three

suburban parishes, simply will not vote for black judicial

candidates. Community leaders with extensive political experience,

such as Revius Ortique, Melvin Zeno and Bernette Johnson, testified

that they received little support from white voters. See, e.g..

Tr. at 75, 88. Bernette Johnson campaigned vigorously and received

endorsements from both white and black political leaders in Orleans

Parish, as well as from the Times-Picavune. Although she received

85% of black votes cast, she received only 30% of the votes cast

by whites in her campaign for Civil District Judge in 1984. Tr.

at 47-50.

In light of this uncontradicted evidence, the district court

found that only within Orleans Parish itself are black voters, a

numerical majority, able to overcome white bloc voting to elect

candidates of their choice. RE 34. Thus, "black persons . . .

serve as judges only in Orleans Parish." RE 33, Table 1. In the

three majority white suburban parishes, however, "no black

candidate has been elected in a contested election to parish-wide

office . . . " since 1978.9 RE 37. And "[i]n this century, no

black person has served as a judge in St. Bernard or Plaquemines

Parish." RE 37.

9 There is no evidence in the record that black candidates

were elected to office prior to 1978.

9

c. The "Senate Report" Factors

The three circumstances highlighted by Ginales represent a

distillation of a longer list of nine "[t]ypical factors" relevant

to claims of vote dilution identified in the Senate Report that

accompanied the 1982 amendment of section 2. S. Rep. No. 97-417

97th Cong. 2d Sess. 28-9 (1982) [hereafter "Senate Report".],10 the

"authoritative source for legislative intent" in interpreting

amended section 2, Ginales. 478 U.S. at 43 n. 7. While the Senate

Report makes clear that the factors are not to be treated as a

mechanical point-counting device, see Senate Report at 29, the

evidence in this case establishes the presence of each one of the

relevant factors.11

1. A History of Official Discrimination

As the district court acknowledged, "Louisiana has . . . a

past history -of official discrimination bearing upon the right to

vote." RE 24. The parties stipulated to the existence of, among

other practices, Louisiana's imposition of a "grandfather" clause,

as well as educational and property qualifications for voter

registration (Stip. 37); an all-white primary, that was used until

the Supreme Court outlawed white primaries in 1944 (Stip. 39); the

use of "citizenship" tests, anti-single-shot voting laws, and the

0 See Appendix to this brief for a list of these factors.

In light of the holding that judges do not "represent"

the voters who elected them in any constituent services-related

manner, see. Wells v. Edwards. 347 F. Supp. 453 (E.D. La. 1972),

aff1d per curiam. 409 U.S. 1095 (1973), the eighth Senate factor-

-responsiveness— is not particularly relevant in a judicial

election case. But see, Baldwin v. Alabama, 472 U.S. 372, 397

(1985) (Stevens, J., dissenting) ("[R]esponsiveness and

accountability provide the justification for an elected judiciary")

citing P. DuBois, From Ballot to Bench: Judicial Elections and the

Quest for Accountability 3, 29, 145 (1980).

10

adoption of a majority vote requirement by the State Democratic

Party following the invalidation of the all-white primaries. Stip.

42; see also Stips. 36-39. Indeed, Louisiana's history of official

discrimination repeatedly has been a subject of judicial notice.

See, e .g. . Major v. Treen. 574 F. Supp. 325, 339-341 (E.D. La.

1983) (three-judge court).

Since 1965, Louisiana has been subject to the special

preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. 30 Fed.

Reg. 9897 (1965). Pursuant to those provisions, twelve parishes,

including one within the First District, have been designated for

the appointment of federal examiners. Stip. 45.

Unrebutted evidence and stipulations by the parties prove that

voting discrimination in Louisiana, and within the First District,

continues to this day. See. e.g. . Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325,

339-341 (E.D. La. 1983) (entire metropolitan area); East Jefferson

Coalition for Leadership and Development v. Jefferson Parish, 691

F. Supp. 991 (E.D. La. 1988) (Jefferson Parish); and Citizens for

a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna. 834 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir.

1987) cert, denied 106 L.Ed.2d 564 (1989) (Jefferson Parish).

Noted Louisiana historian Dr. Raphael Cassimere testified that

black voters in East Baton Rouge and Orleans Parishes were targeted

for a, voter purge in 1986, during an extremely close state

senatorial race. Tr. at 132; see also Long v. Gremillon, Civ. Suit

142, 389, 9th Jud. Dist. Rapides Par. (Oct. 14, 1986).

2. Racial Polarization in Voting

As Gingles points out, the second and third prongs of the

Gingles test are the two sides of racially polarized voting. See

11

478 U.S. at 56. The evidence regarding this Senate factor has thus

already been discussed. See supra at 7-9.

3 . The Use of "Enhancing" Devices

The Senate Report specifically identifies three practices that

"may enhance the opportunity for discrimination against the

minority group": unusually large election districts, majority vote

requirements, and anti-single shot provisions. S. Rep. at 29: All

of these practices are present in the First District.

a. The First District is the sole multi-member district

among all Supreme Court districts. It has twice the population of

any congressional district in Louisiana and, in terms of

population, is the largest of any of the state's election

districts. Stip. 82. Black candidates are disadvantaged as a

result of the unusually large size of the district, and the large

number of voters who must be reached and persuaded. See RE 31.

b. Elections for the two Supreme Court positions from the

First District are not conducted in the same year. Because the

terms are staggered, voters are prevented from single-shot voting.

RE 14; Stip. 22.

c. A majority vote requirement applies in elections for

the Supreme Court. RE 13. If no candidate receives a majority of

the vote in the primary, the top two vote-getters compete in a

general election. RE 14.

4. Candidate Slating Process

There is no formal slating process for judicial candidates

within the First District. Nonetheless, in judicial elections, bar

group endorsements provide a critical form of candidate support

akin to slating in traditional legislative contests. The district

12

court found that "all of the current officers of the Louisiana Bar

Association are white, and no black judge has ever served as one

of the officers of the Louisiana District Judges Association." RE

30. Moreover, the New Orleans Bar Association has never endorsed

a black candidate for judicial office. RE 30-31. Thus blacks do

not have equal access to the informal slating/endorsement process.

5. Depressed Socioeconomic Status

The Senate Report expressly recognized that "disproportionate

education, employment, income level and living conditions arising

from past discrimination tend to depress minority political

participation." S. Rep. at 29, n. 114. The 1980 Census reported

vast disparities in socioeconomic indicators for blacks and whites

in Louisiana.12

Particularly in the area of education, blacks continue to

suffer the vestiges of discrimination in Louisiana, affecting their

ability to participate in the political process. RE 20. "As

recently as August 1988, a panel of three judges found Louisiana

higher public education operated as a dual system." RE 30, citing

United States v. State of Louisiana. 692 F.Supp. 642 (E.D. La.

1988) .

No law school in Louisiana accepted black students in this

century until the opening of Southern University Law School in

1947. RE 30; Stip. 93. "At the present time, Louisiana operates

12 For instance, according to the 1980 Census, the percentage

of black residents aged 25 or over who completed four years of high

school is substantially lower in each parish within the First

District than the corresponding percentage for whites. Stip. 101.

The 1980 Census reported that the median income for white families

was twice the median income for black families in Orleans Parish.

Stips. 106, 107.

13

two public law schools: Southern University attended by virtually

all of the State's public black law student population and the

academically superior LSU Law School, attended by most of the white

public law student population," RE 30, (taking judicial notice of

findings in United States v. State of Louisiana. Civil Action 80-

3300). The district court specifically found that "[t]he

relatively lower economic status of local black residents further

affects accessibility to better education and such practicalities

as campaign funding." RE 31.

6. The Role of Race in Political Campaigns

Although this case does not involve claims of overt racial

appeals in judicial elections, see RE 37, unrebutted testimony

showed clearly that race continues to play a prominent role in

judicial campaigns in the First District, particularly in

Jefferson, Plaguemines and St. Bernard Parishes.

For example in 1988, Melvin Zeno, a highly qualified black

candidate for criminal court judge was advised by many white

advisors not to use his picture on campaign literature or to make

personal appearances in Jefferson Parish during his campaign in

order to avoid highlighting his race for fear that white voters

would vote against him. Tr. at 64-66, 69-70, 74. Zeno's white

opponent understood the salience of race: during radio interviews

he repeatedly attempted to signal to listeners that Mr. Zeno was

black. Tr. at 78.13 Similarly, Anderson Council, another black

judicial candidate, also was advised against using his picture or

13 The State of Louisiana was prohibited from "encoura[ging]

its citizens to vote for a candidate solely on account of race,"

by indicating the race of candidates on election ballots. Anderson

v. Martin. 375 U.S. 399, 433 (1964).

14

appearing before the white community in Jefferson Parish. Tr. at

87-88.

Finally Judge Revius Ortigue testified that he would feel

"intimidated" campaigning in either Plaquemines or St. Bernard

Parishes. Tr. at 25. In fact, on a recent trip to hold a judicial

session in Plaquemines, Judge Ortique felt compelled to contact the

sheriff of Plaquemines to ensure his safety while traveling there.

Tr. at 2 5.14

7. Minority Electoral Success

No black candidate has been elected to the Louisiana Supreme

Court in this century. RE 33; Stip. 46. The only black to serve

on the Louisiana Supreme Court was appointed and served for a

period of 17 days in November 1979. RE 33; Stip. 47. In 1972 a

black candidate unsuccessfully ran for Supreme Court from the First

District.

The district court itself found that in the four-parish area

that makes up the First District, blacks serve as judges in Orleans

Parish only. See RE 53. No black person has won a contested

parish-wide race in either St. Bernard, Plaquemines or Jefferson

Parishes since 1978. RE 35.

The district court found that blacks did have an opportunity

to elect their preferred candidates in Orleans Parish-only

elections, see RE 44-46. But even in Orleans Parish, blacks are

still "a clear minority of elected officials" RE 44. Since the

14 Plaquemines Parish has a well documented history of

harassing civil rights lawyers and activists. See, e.g. . Sobol v.

Perez. 289 F. Supp. 392 (1968). Like Judge Ortique, several black

lawyers in the Sobol case "testified as to their unwillingness or

reluctance to go to Plaquemines Parish in a civil rights case."

289 F. Supp. at 401.

15

combined white electorate in Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemines

outnumbers the black electorate of Orleans Parish, there is no

realistic potential for black electoral success in the four-parish

district.

8. Tenuousness

Defendants presented no evidence of any policy — racially

neutral or otherwise — that justified including Orleans Parish

within the only multimember Supreme Court district. The only

rationale offered by the State for maintaining the currently

constituted Supreme Court districts was "continuity, stability and

custom." Tr. at 184.15

D. The District Court's Findings of "Ultimate" Fact

The district court made'a number of findings of ultimate fact

based on the uncontested subsidiary facts detailed above. With

regard to the Gingles test it found that plaintiffs had failed to

satisfy the first prong because an Orleans Parish-only Supreme

Court district was unacceptable, both for reasons related to

excessive population deviation and for reasons connected with the

undesirability of creating single-parish Supreme Court districts.

We explain below why the district court's conclusions reflect both

clearly erroneous findings of fact and serious distortions of the

applicable law. See infra Arg. I. C.

15 The district court noted that in 1879, when the present

configuration of the First District was established, "the parishes

of Orleans> St. Bernard, Plaquemines and Jefferson were considered

an inseparable metropolitan or quasi-metropolitan area." RE 27.

The court below did not address the question whether such a

rationale supports the maintenance of the current multimember First

District.

16

The district court then found that plaintiffs had failed to

satisfy the second and third prongs of Gingles -- a showing of the

existence of racially polarized voting — because it found that

black voters could elect black candidates in Orleans Parish only

elections and could elect white candidates in elections involving

the four-parish area. We explain below how the district court's

findings involved legal errors in equating ability to elect within

Orleans Parish with ability to elect in a multi-parish district,

and in relying on white-on-white elections to overcome the clear

evidence that blacks are unable to elect black candidates in the

current First District. See infra Arg. II. B. 2, 5.

As for the remaining Senate Factors, although the district

court recognized their presence in this case, it found with regard

to some of the factors that blacks were overcoming the legacy of

discrimination and political exclusion in Louisiana and simply

denied the legal relevance of other Senate Factors. We explain

below why all the Senate Factors are legally relevant to

plaintiffs' claims and how they buttress the conclusion that

plaintiffs are currently being denied an equal opportunity to

participate and elect the candidates of their choice in contests

involving the selection of Louisiana Supreme Court Justices. See

infra Arg. III.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court incorrectly held that the method of

electing judges in Louisiana's First District did not violate

section 2. This wrong conclusion is based on the district court's

refusal to make logical inferences from a largely stipulated

factual record, and is irredeemably tainted by the court's

17

misconception of the legal standard to be applied in section 2

cases.

In such cases, plaintiffs are required to make a three-part

threshold showing. Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 50-51

(1986). Brewer v. Ham. 876 F.2d 448, 452 (5th Cir. 1989); Campos

v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240, 1244 (5th Cir. 1988), cert,

denied. 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989). The district court erred in holding

that plaintiffs failed to satisfy this three-pronged test. The

district court erred in holding that the black population in the

First District was not sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district. The

overwhelming majority of black registered voters in the challenged

at-large district reside in a geographically definable subdistrict,

Orleans Parish, which has a sizeable total population. Thus

minority voters in a district made up of Orleans Parish only would

possess the potential to elect candidates of their choice.

The district court erred in holding that there was no

significant racially polarized voting in the challenged district.

Racial bloc voting constitutes the linchpin of a section 2 vote

dilution case, and evidence of polarized voting satisfies both the

second and third prongs of Gingles1 test. 478 U.S. at 56. Campos

v. City of Baytown. 840 F.2d 1240 (5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied,

109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989); Westwego Citizens for Better Government v.

City of Westwego. 872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir. 1989), and 834 F.2d 496.

Here, the district court erred in relying on electoral results in

white-on-white contests to find that there was no racially

polarized voting. Cf. Gretna, 834 F.2d at 503, 504; see Campos.

840 F.2d at 1245; 478 U.S. at 83, 101. The evidence shows that

18

those black candidates who were not deterred from running were not

successful in district-wide contests. Analysis of elections

involving black and white candidates epitomized bloc voting: whites

voted for white candidates and blacks for black candidates.

The district court's analysis of black political cohesiveness

(which it referred to as "black crossover voting") was

fundamentally flawed. The court's treatment of white crossover

voting in black-on-white contests wholly misunderstood the relevant

legal standard. Finally, its reliance on evidence of black

electoral success within Orleans Parish in Orleans Parish-only

elections critically misused that evidence. Such evidence cannot

be used, as the district court did, to rebut a showing of numerical

submergence and legally significant white bloc voting in the

existing multimember district.

The Voting Rights Act requires a court to look at the totality

of circumstances. Once a plaintiff meets the Ginqles test,

impermissable vote dilution is shown. Evidence of the Senate

Factors buttresses that showing and must be considered in its

totality. While, the district court below made relevant findings

with regard to each Senate Factor, i.e., finding that the First

District is "unusually large" and that single shot voting is

precluded, it stopped short of drawing the obvious and appropriate

conclusions from these findings. The court below also failed to

give proper weight to the Senate Factors, and to view them

interactively as part of a "functional view of the political

process" in the First District, as directed by this Circuit and the

Supreme Court in Ginqles. 478 U.S. at 45.

19

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Misinterpreted The First

Gingles Factor

One of the threshold requirements established by the Supreme

Court's decision in Gingles. 478 U.S. 30 is that the minority group

in a section 2 challenge to multimember districting "demonstrate

that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to

constitute a majority in a single-member district." Id. at 50.

In this case, the district court held that plaintiffs had failed

to meet this requirement because the only way to establish a

majority black single member district would be to create a

"gerrymandering [sic] district lacking geographical compactness."

RE 19-20. The district court was wrong. Its conclusion reflects

a fundamental misunderstanding both of the applicable law and of

the evidence in this case.

A. The Applicable Legal Standard

The Gingles Court squarely rejected a formalistic approach to

section 2 cases in favor of a "'functional' view of the political

process." 478 U.S. at 45 (quoting S. Rep. at 30 n. 120 (1982)).

The first prong of the Gingles test reflects this functional

approach, for it asks essentially whether "minority voters possess

the potential to elect representatives in the absence of the

challenged structure or practice," that is, whether "a putative

districting plan would result in districts in which members of a

racial minority would constitute a majority of the voters . . . ."

478 U.S. at 50 n.17 (internal quotation marks omitted). In light

of this guidance/ two things are clear. First, the question

whether a particular districting scheme identified by the

20

plaintiffs satisfies the first prong of Gingles is not the

functional equivalent of deciding that scheme should be imposed on

the defendant jurisdiction. Should the court find a section 2

violation, it must accord the defendant an opportunity to propose

its own scheme and must defer to that scheme if it provides a

complete remedy. See Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 (1978).

Second, the "compactness" aspect of the requirement must be

assessed in real-world terms: it does not refer to some abstract

notion of district "attractiveness," Gaffney v. Cummings. 412 U.S.

735, 752 (1973), but rather to whether the proposed districts

exhibit a sufficient sense of community to enable effective

political participation by their inhabitants, Dillard v. Baldwin

County Board of Education. 686 F. Supp. 1459, 1466 (M.D. Ala.

1988) .

This Court's interpretations of the first prong of Ginales

have recognized this pragmatic approach. For example, in

interpreting the numerosity component of the Gingles requirement,

the Court has asked whether the minority group has the potential

to form a majority of the electorate in a proposed district, since

a minority that possesses that characteristic also has the

potential to elect the candidates of its choice. See Brewer v.

Ham. 876 F.2d 448, 452 (5th Cir. 1989). Similarly, this Court has

rejected the requirement that all minority voters in the

jurisdiction live within a proposed district, as long as minority

voters have a sufficient concentration within the district to elect

their preferred candidates. See Campos. 840 F.2d at 1244.

Finally, this Court has exhibited a strong preference for asking

whether the creation of a majority-black district is possible

21

within the parameters of the existing electoral structure, without

distorting aspects of the electoral system other than the ones

being challenged directly. See, e.g.. Brewer, supra.

In short, the legal issue raised by the first prong of Gingles

is not whether any particular districting scheme should supplant

the scheme being challenged. Rather, the question is whether it

would be possible to create alternative schemes that would afford

minority voters the ability to elect their preferred candidates.

B. The Evidence in this Case

The crux of the district court's erroneous conclusion rests

on its rejection of a simple, elegant alternative to the present

First District: a division of the district into two single-Justice

districts, one composed of Orleans Parish, and the other composed

of Jefferson, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines Parishes. The following

salient, undisputed facts about an Orleans Parish-only district

show how it meets the first prong of Gingles:

1. Such a district would be majority black in registered

voters. RE 16 (53.6% of registered voters in Orleans Parish are

black.) Thus, black voters clearly would possess the ability to

elect the candidates of their choice. See also RE 44 (concluding

that black voters do have the ability to elect their preferred

representatives in Orleans Parish-wide elections).

2. The use of an Orleans Parish-based district would by

definition involve a "sufficiently . . . geographically compact"

district. 478 U.S. at 50. Orleans Parish already constitutes a

discrete electoral unit for a host of elections: a mayoralty,

numerous lower court judgeships, a sheriff, and the like. See RE

53 & 61 (Tables 1 & 7 including some parish-wide offices) .

22

Moreover, by creating and recognizing parishes, the State has

already decided that parishes form distinct communities. Thus, the

district court was clearly erroneous in asserting that an Orleans

Parish-only district was a "gerrymandering [sic] district lacking

geographical compactness." RE 20. If anything, the creation of

two single-justice districts that avoid splitting parish lines

precludes any artificiality in districting.16

3. The illustrative division of the present First District

would comport with Louisiana's existing policy regarding population

deviations among Supreme Court districts. The plain fact is that

the current Supreme Court apportionment scheme in Louisiana bears

no relation to the "ideal district" scheme to which the district

court unfavorably compares plaintiffs' proposal.17 At present,

four of the six districts deviate from the ideal size by more than

10%, see RE 17 (districts 1, 3, 4, and 5). The current total

deviation is 74.95% (between districts 4 and 5), while the average

deviation is 19.55%. The deviations of plaintiffs' proposed

districts are -7.2% (for the Orleans Parish district) and -9.3%

(for the Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard district). These

figures fall well within the deviations Louisiana implicitly finds

This is not to say, of course, that an appropriate

remedial plan might not split parish lines. See RE 19, n. 26.

17 Ideal districts, as identified by the district court, are

obtained by dividing the total population of the state by the

number of districts, see RE 69. This methodology derives from the

one person one vote concept that applies in legislative election

schemes only. Since the one person one vote principle does not

apply to the Louisiana Supreme Court, see Wells v. Edwards. 347 F.

Supp. 453 (E.D. La. 1972); there is no basis for comparing

plaintiffs proposal to an equal population ideal. Nevertheless,

plaintiffs' alternative is well within legally tolerable limits.

Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. 835 (1983).

23

tolerable: they are smaller than all but two of the existing

deviations.

Moreover, the district court's assertion that the

"isolat[ion]" of Orleans Parish in a single district "would leav[e]

a second district with an atypically low voter population," RE 19,

is clearly erroneous. Each of the alternative districts would have

more registered voters than the current Fourth District has, see

RE 16 (Orleans District would have over 237,000 voters; other new

district would have over 255,000 voters; Fourth District presently

has only 208,000). Moreover, each of the new districts would have

larger total populations than either the Fourth or the Second

District, see RE 15-16.

C. The District Court Erred in Rejecting a Single-Parish

District at the Liability Phase of Trial

The district court's real objection seems to lie not in any

true application of Ginqles to the facts of this case but rather

in its belief that because "to date, no parish is isolated as a

single district in this state," RE 19, plaintiffs cannot use a

single-parish district to meet the threshold liability requirement.

That belief is quite simply misguided.

First, the district court mistakes the relevant inquiry: at

the liability stage, the question is not whether Louisiana must

adopt a single-parish district. There may in fact be many ways of

avoiding single-parish districts that would afford black voters an

equal opportunity to elect Supreme Court justices. Rather, the

question is only whether the use of the present multiparish,

multimember district is causally related to the current inability

24

of blacks to elect the candidate of their choice. For the reasons

we explain below, see infra Arg. II. A. 5., it is.

Second, the district court has not identified any important

state policy that precludes single-parish districts. Indeed, the

Louisiana Constitution apparently would authorize such a division.

See RE 14-15.

Third, the district court's conclusion ignores the "'past and

present reality'" that Ginales expressly directed it to consider.

478 U.S. at 79 (quoting S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 30 (1982)). At the

time the present scheme was inaugurated in 1879, Orleans Parish

numerically, economically, and politically dominated the First

District. See Major v. Treen. 574 F. Supp. 325, 329 (E.D. La.

1983) (three-judge court) (prior to 1980, New Orleans' population

sufficiently outnumbered the suburban population for Orleans Parish

to dominate both metropolitan congressional districts). Thus, to

have an Orleans Parish-dominated district would hardly represent

a repudiation of Louisiana tradition.

Finally, all justices, regardless of the district from which

they were elected, sit on all cases, see RE 14. More importantly,

justices are not permitted, let alone expected, to advance the

interests of litigants from particular geographical regions of the

State. In light.of these factors, the configurations of territory

from which they are elected cannot play the major role assigned

them by the district court in this case.

25

II. The District Court Made Critical Errors of Fact and Law In Its

Analysis Of Racially Polarized Voting

Racial bloc voting constitutes the linchpin of a section 2

to

vote dilution case. The district court's refusal to find such

polarization in this case rests on a fundamental misunderstanding

of the relevant legal principles. In this section of the brief,

we first discuss the legal standards to be applied in assessing

racial bloc voting and then show how the district court's

misunderstanding of those standards jaundiced its view of the

undisputed evidence in this case, deflected its attention from

legally relevant facts to legally irrelevant ones, and tainted its

application of the law to the facts which it properly found.

A. The Applicable Legal Standard

The second and third prongs of Gingles require that plaintiffs

show that "the minority group ... is politically cohesive" and

"that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it

... usually to defeat the minority's preferred candidate." 478 U.S.

at 51. These two factors together establish racially polarized

voting. See id. at 56. Gingles and this Court's post-Gingles

decisions18 have set out a well-defined method of assessing the

issue of racial bloc voting, which is "usually proven by

statistical evidence" regarding election returns. Campos. 840 F.2d

at 1243. A close reading of those cases shows five legal

principles that must guide district courts' assessments of the

electoral evidence before them.

18 Campos v. City of Baytown. 840 F.2d 1240; Westwego Citizens

for Better Government v. City of Westwego, 872 F.2d 1201 (5th Cir.

1989) , and Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna.

Louisiana. 834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987), cert denied, 109 S.Ct.

3213 (1989) .

26

1. The Particular Salience of Elections Involving Both

Black and White Candidates

In Ginqles. both the district court and the Supreme Court

relied on evidence concerning voter behavior in so-called black-

on-white contests only. See 478 U.S. at 52. Examination of such

elections, in which "blacks strongly supported black candidates

while . . . whites rarely did, satisfactorily addresses each facet

of the proper legal standard." Id. at 61. In light of Ginqles,

this Court has consistently affirmed findings of racial bloc voting

based solely on the analysis of black-on-white elections. See,

e.q.. Campos. 840 F.2d at 1245 ("district court was warranted in

its focus on those races that had a minority member as a

candidate"); Gretna, 834 F.2d at 504 ("black preference is

determined from elections which offer the choice of a black

candidate").

A particular focus on races involving black candidates is

faithful to the language of section 2 and the directives provided

by the House and Senate Reports that give "authoritative" guidance

in interpreting section 2. Ginqles. 478 U.S. at 43 n. 7. Section

2 itself makes "[t]he extent to which members of a protected class

have been elected to office . . . one circumstance which may be

considered ...." 42 U.S.C. § 1973b. Indeed, minority electoral

success is the only circumstance explicitly identified in the

statute itself. The Senate Report also identifies minority

electoral success "in the jurisdiction" involved in a section 2

suit as a probative factor. S. Rep. No. 97-417 at 29 (1982).

Finally, the House Report defines "representatives of choice" as

27

"minority candidates or candidates identified with the interests

of a racial or language minority." H. Rep. No. 96-227, 97th Cong.,

1st Sess. at 30 (1981).

Elections involving black candidates are of particular

salience because an election scheme that complies with section 2

must provide black voters with an equal opportunity to elect the

candidates that they have "sponsored," Gingles, 478 U.S. at 57 n.

25, and not simply to choose among candidates sponsored by the

white community. Blacks must be provided with an equal opportunity

to vote for candidates who reflect their "sentiment ... as to the

individuals they choose to entrust with the responsibility of

administering the law." Chisom v. Edwards. 839 F.2d at 1063; cf.

Gingles. 478 U.S. at 51 (the political cohesiveness prang of the

Court's test takes into account the existence of "distinctive

minority group interests" that lead minorities to vote for the same

candidates). As this Court recognized, blacks are afforded the

ability to give effective voice to that sentiment "only within the

context of an election that offers voters the choice of supporting

a viable minority candidate." Gretna, 834 F.2d at 503; see Campos,

840 F . 2d at 1245 (although of necessity, some Anglo candidates

received a majority of the minority vote in each election involving

only Anglo candidates "[tjhere was no evidence that any Anglo-

Anglo race ... offered the voters the choice of a 'viable minority

candidate ' " ) .19

9 See, e.g.. B. Grofman, Representation and Redistricting

Issues 58 (1982) (black elected officials, and thus black

candidates, are the "focus of black expectations" for a voice in

the selection of government officials); C. Lani Guinier, "Keeping

the Faith: Black Voters in the Post-Reagan Era," 24 Harv. C.R.-

28

2. The Legal Inconseguentialitv of Voting Patterns in

Elections Involving Only White Candidates

A° logical corollary to the particular salience of black and

white voting behavior in elections involving both black and white

candidates is the relative irrelevance of voting behavior in

contests in which only white candidates are competing. Indeed, in

Gingles, five Justices found the presence of a black candidate so

important in determining bloc voting that they suggested that only

elections involving black and white candidates can be probative.

See id. at 83, 101. As this Court succinctly noted in Gretna,

"[t]he various Gingles concurring and dissenting opinions do not

consider evidence of elections in which only whites were

candidates. Hence, neither do we." - 834 F.2d at 504 ; see also

Campos, 840 F.2d at 1245 (same).

3. The Level of Black Support for Black Candidates

Necessary to Prove Political Cohesiveness

Gingles clearly stated that a "showing that a significant

number of minority group members usually vote for the same

candidates is one way of proving the political cohesiveness

necessary to a vote dilution claim, and consequently, establishes

minority bloc voting within the context of § 2." 478 U.S. at 56

(internal citation omitted). Gingles does not require minority

unanimity to show cohesiveness. See id. at 80-82; Campos, 840 F.2d

at 1249 (finding minority cohesion on the basis of three elections

in which the minority candidates received 83%, 78%, and 63% of the

minority vote); Gretna. 834 F.2d at 500 n. 9 (political

L.L. Rev. 393, 421 (1989).

29

cohesiveness in Ginqles was shown by black support for black

candidates ranging from 71 to 96% of votes cast).

In light of Ginqles this Court has found black cohesiveness

on the basis of evidence showing that a black plurality has

supported a black candidate, as well as on the basis of virtually

unanimous black support for particular candidates. See Gretna. 834

F.2d at 503 n. 17 (statistics showing black candidate received 49%

of black vote "indicate [candidate] as a black aldermanic

preference"); see also, e. q. . Campos. 840 F.2d at 1246 n. 9

(receipt by minority candidate of 62% of minority vote indicates

political cohesiveness).

4. The Meaning of Legally Significant White Bloc Voting

Just as some black support for white candidates in black-on-

white contests does not disprove the existence of black political

cohesiveness, so too, the fact that some white voters cast their

ballots for the black candidate does not disprove the existence of

white bloc voting. Ginqles squarely held that "a white bloc vote

that normally will defeat the combined strength of minority support

plus white 'crossover' votes rises to the level of legally

sufficient white bloc voting." 478 U.S. at 56. Thus, whether

there is legally significant white bloc voting is necessarily a

fact-intensive inquiry.20 Thus, "Ginqles does not require total

? Q ,The Court went on to explain:

The amount of white bloc voting that can

generally 'minimize or cancel' black voters'

ability to elect representatives of their choice

will vary from district to district

according to a number of factors, including the

nature of the allegedly dilutive electoral

mechanism; the presence or absence of other

potentially dilutive electoral devices, such as

30

white bloc voting. Instead, it requires only that ' [the] white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it . . . usually

to defeat the minority's preferred candidate." Campos. 840 F.2d

at 1249.

In Campos. there was legally significant white bloc voting in

one election in which the Hispanic candidate received 37% of the

white vote because, even with that crossover and "over-whelming

minority support (83%)," id. . he still was defeated. Such a

conclusion was entirely consonant with Gingles teaching, since in

that case, although white support for black candidates averaged

over 18% and ranged as high as 50% in primary elections and 49% in

general elections, see 478 U.S. at 59, the court nevertheless found

legally significant white bloc voting. In sum, as long as not

enough whites support black candidates to enable those candidates

actually to win, there is legally significant white bloc voting.

5. The Relevance of Voting Behavior Within Maioritv-Black

Subsections of Maioritv-White Districts

Black electoral success in a majority black subsection of a

challenged district provides a concrete illustration of the causal

relationship between the challenged electoral practice — the use

of a larger, multimember district — and the dilution of black

majority vote requirements, designated posts,

and prohibitions against bullet voting; the

percentage of registered voters in the district

who are members of the minority group; the size

of the district; and, in multimember districts,

the number of seats open and the number of

candidates in the field.

478 U.S. at 56 (internal citations omitted).

31

voting strength.21 Indeed, it is the existence of this submerged

majority black district that is the essence of dilution where

voting is racially polarized. See, e.g.. Gingles. 478 U.S. at 90-

91 (O'Connor, J., concurring in the judgment) (when plaintiff class

identifies a potential majority-black district, "the

representatives that it could elect in the hypothetical single

member district ... in which it constitutes a majority will serve

as the measure of its undiluted voting strength"); Rogers v. Lodge.

458 U.S. 613, 616 (1982) (an indication of the dilutive tendency

of multimember schemes is the fact that blacks "may be unable to

elect any representatives in an at-large election, yet may be able

to elect several representatives if the political unit is divided

into single member districts"); see also Brewer v. Ham. 876 F.2d

448, 455 (5th Cir. 1989). In short, black . voting behavior in

majority black subsets of the district can show the potential

ability to elect candidates if the larger district is disaggregated

into smaller districts, one of which is majority black.

21 Voting behavior within a geographically distinct, majority-

black portion of a multimember district can be legally relevant to

a section 2 claim in two well-delineated circumstances. First, it

can show black political cohesion through the use of extreme case,

or homogenous precinct, analysis — one of two standard methods of

quantifying racial bloc voting approved in Gingles. See also,

Gretna. 834 F.2d at 500 n. 8 (noting how results of extreme case

analysis can support conclusions reached through regression

analysis).

Second, black electoral success within majority black

electoral districts or jurisdictions that are contained within the

challenged multimember district can also provide potent evidence

regarding the first prong of the Gingles test: the potential

ability of blacks to elect the candidate of their choice from a

"geographically compact" single-member majority black district

carved out of the challenged multimember district being attacked

in the section 2 case. 478 U.S. at 50.

32

What examination of black voting behavior and electoral

success within a majority black subset of an overall white

jurisdiction cannot do, however, is prove that blacks have the

potential to elect their candidates from that larger, predominantly

white district. For example, Ginqles involved a challenge to

multimember state House districts and to a single-member multi

county state Senate district.22 The Ginqles district court

expressly noted that blacks had been elected to local offices in

portions of some of the state legislative districts. See Ginqles

v. Edmisten. 590 F. Supp. 345, 365-66 (E.D.N.C. 1984) (three-judge

court), aff'd in relevant part. 478 U.S. 30 (1986). But it

discounted the legal significance of that electoral success with

regard to the question whether black voters could elect the

candidates of their choice to state legislative seats because many

of those local candidates had been elected from heavily black

jurisdictions within the challenged state legislative districts.

See, e.g. . 590 F. Supp. at 366 (sole black member of the school

board was elected from a majority black subdistrict within a 21.8%

black multimember house district); id. at 367 (that black

candidates can get elected "when the candidacy is in a majority

black constituency" or "is for local rather than statewide office"

does not prove that blacks have an equal opportunity to elect the

candidates of their choice in majority-white, multimember state

legislative districts). See also, East Jefferson Coalition for

22 The Supreme Court summarily affirmed the district court's

finding of a section 2 violation with regard to the senate

district. 478 U.S. at 41.

33

Leadership and Development. 691 F. Supp. 991 (cannot extrapolate

from black electoral victories in two local contests).

In sum, black voting behavior in majority-black areas within

a larger majority-white jurisdiction cannot rebut a showing of

numerical submergence and legally significant white bloc voting in

a challenged multimember district.

B. The District Court's Errors in this Case

The district court's analysis in this case flouts all five of

the well-established principles discussed above. First, the

district court wrongly ignored the evidence showing that plaintiffs

have no opportunity to elect a black candidate to the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First District. Second, the district court

erroneously relied on electoral results in white-on-white contests

to find unimpeded black political access and opportunity to elect.

Third, the district court's analysis of black political

cohesiveness (which it referred to as "black crossover voting") was

fundamentally flawed. Fourth, its treatment of white crossover

voting in black-on-white contests wholly misunderstood the relevant

legal standard. Finally, its reliance on black electoral success

in Orleans Parish-only elections critically misused that evidence.

1. The District Court Wrongly Ignored the Inability of

Black Voters to Elect Black Candidates to the Louisiana

Supreme Court

The district court declined to accord special weight to voting

behavior in contests in which both black and white candidates

sought judicial office: to its way of thinking such elections were

"not determinative of a finding of racial cohesion or racially

polarized voting." RE 45. It found that blacks "routinely elect

their preferred candidates." Id. at 51. That finding was based

34

in part on blacks' ability to elect black candidates within Orleans

Parish alone, an error in applying principle five below. See infra

at 40-43. To the extent that it was based on a belief that blacks

within the four-parish First District either have or could elect

a black to the Louisiana Supreme Court, however, it is flatly

wrong.

First, the district court failed to point to a single instance

in which a black candidate has ever carried a majority of the vote

in the First District. The.history of black candidates' defeat in

judicial elections and other parish-wide contests is well

established in this case. See supra at 15-16; RE 33, 35, and 37.

Outside of Orleans Parish, no black person has ever won any parish

wide office in a contested election. Id. White voters in the

suburban parishes outnumber black voters in Orleans Parish, thereby

giving white voters the absolute ability to veto any black-

sponsored black candidate. And black candidates in so-called

exogenous elections involving all four First District parishes have

carried the black vote overwhelmingly, but have never received

sufficient white votes to finish first overall. See RE 42-43.

Thus, as a matter of historical fact, the district court was

clearly erroneous: blacks have yet to be able to elect a black

candidate to office in an election involving the First District.

Second, the undisputed evidence shows that the numerical

submergence of Orleans Parish within the majority-white four-

parish First District has denied blacks the ability even to sponsor

candidates, let alone elect them. Undisputed testimony by sitting

black judges Revius Ortique, Tr. at 36, and Bernette Johnson, Tr.

at 52; see RE 33, revealed that they would not even run for seats

35

from the current First District because of the district's current

configuration would prevent them from winning. See also Tr. at

105-06 (testimony of Edwin Lombard) (black candidates would not be

able to raise money for a First District race because of the

perception that they would be unable to win); id. at 83 (testimony

of Melvin Zeno) (blacks are deterred from running for judicial

office in Jefferson Parish because they cannot win). The district

court dismissed this testimony "as speculative, and lacking

probative value; if black candidates do not run and increase their

notoriety, they surely cannot win." RE 34.

That dismissal reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the

relevant law. That black candidates refuse to run is critically