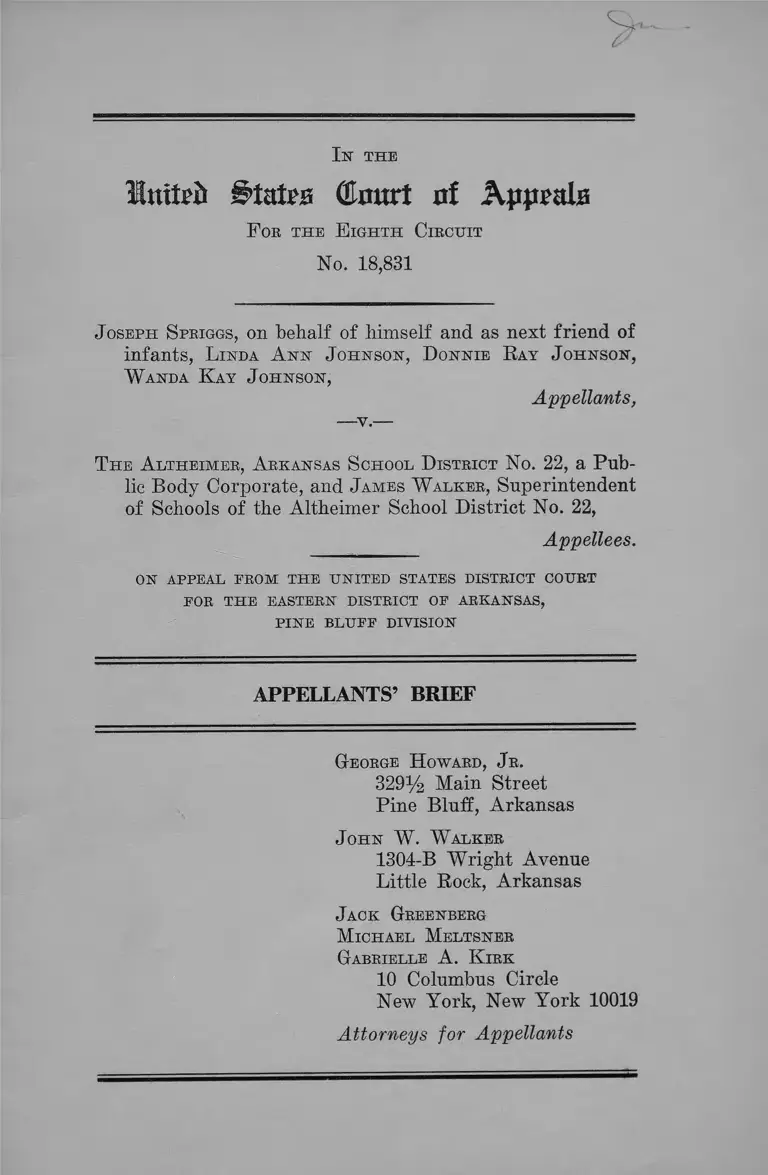

Spriggs v The Altheimer School District Appellants Brief

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1967

27 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Spriggs v The Altheimer School District Appellants Brief, 1967. 1e5354ec-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d2e05152-3b46-4493-a188-ed5c73502389/spriggs-v-the-altheimer-school-district-appellants-brief. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

I s r t h e

Ittttei* States dmtrt at Appeals

F oe the E ig h th Cikcuit

No. 18,831

J oseph S peiggs, on behalf o f h im self and as next friend of

infants, L inda A n n J ohnson , D onnie E ay J ohnson ,

W anda K ay J ohnson ,

Appellants,

—v.—

T he A ltheim ee , A rkansas S chool D isteict No. 22, a Pub

lic Body Corporate, and J ames W alkee , Superintendent

of Schools of the Altheimer School District No. 22,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL EBOM TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POE T H E EASTERN DISTEICT OP ARKANSAS,

P IN E B L U PP DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

George H oward, Je.

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

M ichael M eltsner

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement............................................................................ 1

Statement of Points to Be Argued .............................. 6

A bgumektt—

I. Altheimer Has Violated Appellants’ Bights

Guaranteed by the Equal Protection and Due

Process of Law Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution

by Requiring That They Pay Tuition to Attend

the Public Schools in the District...................... 9

A. Altheimer’s Tuition Policy Violates the

Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment...................... 9

B. Altheimer has Applied Its Tuition Policy in

a Way Which Violates the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ....... 12

C. Appellants Were Charged Tuition Because

Appellant Linda Ann Johnson Exercised a

“Freedom of Choice” to Attend the Pre

dominantly White School in Altheimer....... 13

II. Minor Appellants Are Residents of the Al

theimer, Arkansas School District No. 22 ....... 16

III. Although Residency Is Determined by State

Law, the District Court Can Apply That Law

in an Action Where Appellants Have Raised,

and Supported With Testimony, Substantial

Federal Claims ..................................................... 19

Conclusion ....................................................................—• 20

Certificate of Service ......................................................... 21

11

T able of Cases

page

Brigham v. Brigham, 229 Ark. 967, 319 S.W.2d 844

(1959) ............................................................................... 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ................................................................. .....11,13,14

Willie Earl Carthan, et al. v. Mississippi State Board

of Education, Civil Action No. 3814 (S.D. Miss.,

October 13, 1965) ...........................................................

Central Manufacturers Mut. Ins. Co. v. Friedman, 213

Ark. 9, 209 S.W.2d 102 (1948) ......................................

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ..............................

11

17

14

Erie By. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938) ........... 20

Green, et al. v. The Department of Public Welfare of

the State of Delaware, et al., Civil Action No. 3349

(D.C. Del., June 28, 1967) .......................................... 20

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ...................................... 9

Hurn v. Oursler, 289 U.S. 238 (1932) ........................... 19

Husband v. Crockett, 195 Ark. 1031, 115 S.W.2d 882

(1938) - ............................................................................. 17

In re Watson, 99 F. Supp. 49 (W.D. Ark. 1951) ....... 16

Kelley, et al. v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir.

1967) .............................................................................. 13,14

Krone v. Cooper, 43 Ark. 547 (1884) .......................... 16

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961) ------------ 9

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) .................. 9

Bainey v. Board of Education of the Gould School Dis

trict, No. 18,527 (8th Cir., August 9, 1967) ............... 13

Ill

PAGE

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) ...................... 11

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958) ...................... 11

Stephens v. AAA Lumber Co., 238 Ark. 842, 384 S.W.2d

943 (1964)......................................................................... 16

Thompson v. Shapiro, Civil Action No. 11,821 (D.C.

Conn., June 19, 1967) ................................................... 20

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966) .... 19

Watson v. Maryland, 218 U.S. 173 (1910) ...................... 10

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) .................. 9

S t a t u t e s a n d C o n s t i t u t i o n s

Ark. Stat. Ann., §80-1501 —................................................9,16

Senate Bill No. 1516, amending §6248-02, Miss. Code

(1942) .............................................................................. U

Ark. Constitution, Art. 14, Section 1 ..............-..... -........ 10

I n t h e

Irnteft (Eimrt of Appals

Foe th e E ig h th C ircuit

No. 18,831

J oseph S priggs, on behalf o f h im self and as next fr ien d o f

infants, L inda A nn J ohnson , D onnie R ay J ohnson ,

W anda K a y J ohnson ,

Appellants,

T he A ltheim er , A rkansas S chool D istrict No. 22, a Pub

lic Body Corporate, and J ames W alker , Superintendent

of Schools of the Altheimer School District No. 22,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS,

P IN E B L U FF DIVISION

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement

This is an appeal from the April 22, 1967 order of the

District Court of the Eastern District of Arkansas dis

missing appellants’ complaint (R. 145).

During the Spring of 1966, two days after minor ap

pellant Linda Ann Johnson, a Negro, chose to attend the

predominantly white Altheimer High School, pursuant to

a “Freedom of Choice Plan” introduced in 1966 as the

first step taken by Altheimer, Arkansas School District

No. 22 (hereinafter referred to as Altheimer) to end its

2

racially segregated schools (R. 141), her grandfather,

Joseph Spriggs, appellant herein, was notified that Linda

and her brother and sister, Donnie Ray and Wanda Kay,

also appellants herein, would each be required to pay

$20.00 per month as tuition for the ensuing school term

and that minor appellants would be required to furnish

their own transportation. Altheimer charged appellants

tuition upon a determination that they were not residents

in the school district since their mother resided in the

adjoining distrct of Wabbesaka approxmately four miles

from Altheimer (R. 72, 84 and 135).

Joseph Spriggs has been a long time resident of Al

theimer. He was given Linda Ann by her father when she

was only three days old. Linda Ann and the other minor

appellants have lived with their grandfather, Mr. Spriggs,

as long as they can remember (R. 137-138). Except for a

few years spent in California and Nevada, Linda has

always attended the public schools in Altheimer and prior

to the Spring of 1966 had never been called upon to pay

tuition (R. 31-32). Since Mrs. Johnson and her husband

manage a cafe, she is unable to properly care for her

children and for that reason all except one of her six

children live with her father, Mr. Spriggs (R. 98 and 101).

Except for a summer she spent with her mother in 1958

because she wanted to attend summer school and take

courses not offered at Altheimer, Linda has never lived

with her mother who is now divorced from her father

and has remarried (R. 34).

Fred Martin, principal of Martin School (predominantly

Negro), in April 1966 conducted the enumeration for the

bi-annual school census (R. 70). In conducting the enumera

tion, he visited Mr. Spriggs’ home and asked the names

and ages of his grandchildren attending the public schools

in that district. At the time of his visit, minor appellants

3

were at their mother’s house and Mr. Spriggs indicated

that he could get this information by calling his daughter,

which he did (R. 62, 63 and 137). Mr. Martin testified

that Mr. Spriggs also said that he intended to let Wanda

Kay stay with him and go to the public schools in the

district since her sister had attended these schools (R. 63).

At the completion of the enumeration, Mr. Martin re

ported this information to the Superintendent of Schools,

Mr. James Walker. Mr. Martin testified that although

there are no records of how many pupils attending the

public schools in the district live with persons other

than their parents (R. 61), he knows of other pupils who

are in this category (R. 58). As part of the enumeration

he visited such families; however, he did not report these

findings to the Superintendent of Schools (R. 75). Mr.

Martin further testified that he did not know that minor

appellants lived with their mother (R. 66) and, in fact,

never asked Mrs. Johnson whether her children lived

with her (R. 67). He admitted that it is his belief that

Linda lives with Mr. Spriggs (R. 70).

For a number of years Altheimer has maintained a

policy of charging tuition to nonresident students but this

policy was not reduced to writing until 1963 (R. 81).

Robert J. Bowen, Jr., chairman of the Board of Educa

tion of Altheimer, during the trial quoted from the

Altheimer’s tuition policy as follows:

Children whose parents reside outside the Altheimer

school district will pay tuition. Tuition for pupils in

the first six grades is $14.00 per month; in grades

seven through twelve, $16.00 [subsequently altered

to $20.00 per month, R. 82]. A pupil who lives with

relatives or friends but who will return to the homes

of his parents or guardian after the school term ends

will be required to pay tuition. (R. 22)

4

Mr. Bowen interpreted this policy as requiring children

who come into the district solely for the purpose of at

tending school to pay tuition, but if the pupils actually

reside within the district, regardless of whether such resi

dence is with a natural parent, they would be entitled to

attend the public schools without the payment of tuition

and would be eligible to receive the transportation pro

vided by Altheimer (R. 23). However, Mr. James Walker,

the Superintendent of Schools for Altheimer, interprets

residence of the child as being the residence of the parents

(R. 83) although he testified that “ from what I ’ve heard

this morning they [minor appellants] reside with Joseph

Spriggs” (R. 84).

There are approximately 1,438 children enrolled in the

Altheimer district (R. 88). No student (except the appel

lants) living in the district with relatives has ever been

required to pay tuition (R. 86). Children who reside out

side of the boundaries of Altheimer may attend its public

schools but must pay tuition. There are approximately

20 children presently enrolled in Altheimer in this category

(R. 82). Children of employees of the school district may

attend the public schools of Altheimer without paying

tuition even if they reside outside of the district. There

are approximately four or five white pupils in this cate

gory attending the schools of Altheimer (R. 26).

Mr. Samuel L. Dendy, Mrs. Sylvia Mae Jamerson, Mr.

Amos Jones, and Mr. Ernest Kearney, Negro residents

of Altheimer, testified that they presently have children

of relatives or friends living with them who have chosen

to attend Negro schools and that these children have not

been required to pay tuition and have been afforded the

free transportation provided by Altheimer (R. 46-57).

On August 22, 1966, Joseph Spriggs, on behalf of him

self and as next of friend of infants Linda Ann Johnson,

5

Donnie Ray Johnson and Wanda Kay Johnson, filed a

complaint in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas, in which he sought a pre

liminary and permanent injunction enjoining Altheimer

and James _ Walker, Superintendent of Schools of Al

theimer, from conditioning the right of minor appellants

to attend the public schools in that district upon the pay

ment of tuition. A declaratory judgment was also sought.

Mr. Spriggs alleged that the minor appellants were resi

dents of the district; that the imposition of the tuition

and transportation requirements upon them was for the

purpose of punishing minor appellant Linda Ann Johnson

for exercising her choice to attend a predominantly white

school and for the purpose of discouraging other persons

similarly situated from making a choice to attend

predominantly white schools; and that Altheimer’s exact-

ment of tuition deprived appellants of their right to free

public education and rights of due process and equal pro

tection guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution (R. 3). On April 20, 1967, this

cause was tried before Honorable Oren Harris, who, on that

same day, rendered a decision in this matter dismissing ap

pellants’ complaint (R. 140). Notice of appeal was filed on

April 21, 1967 (R. 2). The order of dismissal was filed on

April 22, 1967 (R. 145). On April 28, 1967, an order for

injunction pending appeal was entered allowing minor

appellants to attend the public schools of Altheimer with

out the payment of tuition (R. 154).

6

STATEMENT OF POINTS TO BE ARGUED

I.

Altheimer Has Violated Appellants’ Rights Guaran

teed by the Equal Protection and Due Process of Law

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution by Requiring That They Pay Tuition

to Attend the Public Schools in the District.

Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954);

Willie Earl Carthan, et al. v. Mississippi State

Board of Education, Civil Action No. 3814

(S.D. Miss., October 13, 1965);

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958);

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

Kelley, et al. v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8th

Cir. 1967);

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961);

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964);

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963);

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958);

Watson v. Maryland, 218 U.S. 173 (1910);

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

Statutes:

Ark. Stat. Ann., §80-1501;

Senate Bill No. 1516, amending §6248-02 of the

Miss. Code (1942).

7

Minor Appellants Are Residents of the Altheimer,

Arkansas School District No. 22.

Cases:

Brigham v. Brigham, 229 Ark. 967, 319 S.W.2d

844 (1959);

Central Manufacturers Mut. Ins. Co. v. Fried

man, 213 Ark. 9, 209 S.W.2d 102 (1948);

Husband v. Crockett, 195 Ark. 1031, 115 S.W.2d

882 (1938);

In re Watson, 99 F. Supp. 49 (W.D. Ark. 1951);

Krone v. Cooper, 43 Ark. 547 (1884);

Stephens v. AAA Lumber Co., 238 Ark. 842,

384 S.W.2d 943 (1964).

Statutes:

Ark. Stat. Ann., §80-1501.

II.

8

Although Residency Is Determined by State Law, the

District Court Can Apply That Law in an Action Where

Appellants Have Raised, and Supported With Testi

mony, Substantial Federal Claims.

Cases:

Erie Ry. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938);

Green, et al. v. The Department of Public Wel

fare of the State of Delaware, et al., Civil

Action No. 3349 (D.C. Del., June 28, 1967);

Hum v. Oursler, 289 U.S. 238 (1932);

Thompson v. Shapiro, Civil Action No. 11,821

(D.C. Conn., June 19, 1967);

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715

(1966).

III.

9

ARGUMENT

I.

Altheimer Has Violated Appellants’ Rights Guaran

teed by the Equal Protection and Due Process of Law

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution by Requiring That They Pay Tuition

to Attend the Public Schools in the District.

A. Altheimer’s Tuition Policy Violates the Equal Protection

and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Altheimer seems to have based its decision to charge

minor appellants tuition on the fact that their mother did

not reside in its school district but in the adjoining district

of Wabbesaka. This decision was reached without a proper

investigation and denies minor appellants the right to free

public education afforded similarly situated pupils by

Altheimer.

It has long been held that the policy behind the equal

protection clause is to prevent discrimination against par

ticular classes of persons defined on an arbitrary and un

reasonable basis. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

Although a state (and boards of education) may make

classifications among its citizens, such classifications can

not be based upon race. Griffin v. County School Board of

Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 230 (1964), and

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964).

Arbitrary classifications, even though not based on race,

which are not reasonably related to the purpose of a stat

ute, i.e., §80-1501, Ark. Ann. Stat., are void.1 See McGowan

1 Section 80-1501 provides:

The public schools of any school district shall be open and free to

all persons between the ages of six [6] and twenty-one [21] years,

residing in that district, and the directors of any district may per-

10

v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961) and Watson v. Maryland,

218 IT.S. 173 (1910).

For the purposes of eligibility for free public education,

Altheimer has classified children according to their parents’

place of residence. If one factor which motivated this

classification was a desire to insure that only persons who

were taxed by Altheimer would receive the benefits of free

public education, this classification fails to reasonably ef

fectuate this purpose. Certainly, Mr. Spriggs and his wife

pay taxes to Altheimer and have been doing so for

a long time. Are they not entitled to have their grand

children who have been living with them for most of their

natural lives reap the benefits (and rights) of their long

tax-paying years!

Altheimer permits children of its employees to attend the

schools on a tuition-free basis notwithstanding the fact

that these children’s parents reside outside of the district.

If the insistence on parental residence is to insure that

only those who pay taxes are allowed free public educa

tion, again Altheimer has failed to accomplish its purpose

since its employees residing in other districts do not assist

in Altheimer’s tax burden. Do not children living in the

district with their grandfather have a greater right to bene

fit from the district’s free education than children who re

side in another district, and are entitled to free public

education in that district in which they reside!

mit older or younger persons to attend tlie schools under such regu

lations as the State Board of Education may prescribe.

Article 14, Section 1 of the Arkansas Constitution provides:

Intelligence and virtue being the safeguards of liberty and the bul

wark of a free and good government, the state shall ever maintain

a general, suitable and efficient system of free schools whereby all

persons in the state between the ages of 6 and 21 years may receive

gratuitous instruction.

Altheimer’s tuition policy ignores both the state law guaranteeing free

public education and the policy expressed by the Arkansas Constitution.

11

A similar classification of pupils based upon the resi

dence of their parents was made by a Mississippi statute.2

In September of 1965 a motion for a temporary restrain

ing order was filed in the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Mississippi3 seeking to enjoin the

Mississippi State Board of Education from enforcing Sen

ate Bill No. 1516 and thereby denying persons their right

to free public education because their parents reside out

side of the state. The United States government subse

quently intervened and also sought a temporary restrain

ing order. On October 13, 1965, Judge Harold Cox entered

a temporary restraining order enjoining the defendants

from implementing or in any way giving effect to the stat

ute. This statute has since been repealed.

Appellants submit that Altheimer’s classification based

upon the residence of the parents—denying free public

education to those who reside in the district simply because

their parents reside in another district—is likewise arbi

trary and unreasonable and contravenes the equal protec

tion of laws guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954),

stands for the proposition that where the state has under

taken to provide education it is a right which must be

made available to all on equal terms. Once the govern

ment confers advantages to some of its citizens, it must

justify the denial of such advantages to other citizens.

No such justification exists for Altheimer’s refusal to al

low appellants to attend the public schools on a tuition-

free basis. See Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 405-406

(1963), and Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958).

2 Senate Bill No. 1516, amending §6248-02 of the Mississippi Code of

1942.

8 Willie Earl Carthan, et al. v. Mississippi State Board of Education,

Civil Action No. 3814.

12

Altheimer’s tuition policy is itself contradictory. If all

“ children whose parents reside outside the Altheimer School

District” and “a pupil who lives with relatives or friends

but who will return to the homes of his parents or guardian

after the school term ends” must pay tuition, what about

the pupil who lives with relatives or friends but does not

return to the home of his parents or guardian after the

school term ends? Because the parents of such a child

reside outside of the district, must he pay tuition? On the

other hand, if he does not return to his parents’ home at

the end of the school term, must he pay tuition? The reso

lution of these questions depends upon which of these

contradictory provisions of the Altheimer’s tuition policy

is enforced.

B. Altheimer has Applied Its Tuition Policy in a Way Which

Violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Testimony at trial showed that there are many other

children residing in Altheimer with persons other than

their parents who attend the public schools without the

payment of tuition (R. 46-57). Mr. Martin knew of this

situation and yet failed to advise the Superintendent of

Schools (R. 75). Mr. Bowen testified that he “ supposes

that there are other children physically residing in the

district with friends and relatives but whose parents re

side in other districts (R. 29). This testimony alone

clearly indicates that Altheimer has failed to apply its

tuition policy consistently. Instead, minor appellants have

been singled out and have been required to pay tuition.

13

C. Appellants Were Charged Tuition Because Appellant Linda

Ann Johnson Exercised a “ Freedom of Choice” to Attend

the Predominantly White School in Altheimer.

Broivn v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, in 1954 de

clared racial segregation in public education to be in

herently unequal and violative of guarantees of the Four

teenth Amendment. However, as of 1965, Altheimer op

erated racially segregated schools (E. 141). In that year,

eleven years after Brown, in an attempt to comply with

the HEW guidelines so as not to forfeit federal financial

school assistance (R. 96), it adopted the “Freedom of

Choice” plan (R. 141). However, even as of April 12,

1967, the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in

Kelley, et al. v. Altheimer, Arkansas School District No.

22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) required Altheimer to

institute extensive corrective measures to eliminate a ra

cially segregated school pattern which had been perpet

uated by a racially designed school construction program

in existence at the time Altheimer charged appellants tui

tion and after one of them chose to attend the previously

all white school. The facts supporting this design to per

petuate the racial segregation were clear and convincing.

See Rainey v. Board of Education of the Gould School

District, No. 18,527 (8th Cir., August 9, 1967).

The choice forms were first sent out in the Spring of

1966 for the 1966-1967 term. Linda Ann Johnson chose

to attend the formerly all-white Altheimer High School.

Two days later she, and her brother and sister who also

attend the public schools of Altheimer (her brother and

sister chose the Negro school), received a notice from

Altheimer that they would each have to pay $20.00 per

month to attend the public schools and would not receive

transportation generally afforded pupils in the district

(R. 135). This decision by Altheimer was predicated on

a finding by it that the appellants were nonresidents of

the district.

14

Appellants submit that the Board reached this sudden

and unprecedented (R. 86) decision in retaliation of

Linda’s choice to attend the white high school. This is

just a different method of continuing the racially segre

gated educational system which the Court of Appeals con

demned in Kelley v. Altheimer, supra. “ [T]he Constitu

tional rights of children not to be discriminated against in

school admission on grounds of race or color declared by the

court in the Brown case can neither be nullified openly

and directly by state legislators or state executive or

judicial officers, nor nullified indirectly by them through

evasive schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘in

genuously or ingeniously’.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT.S. 1,

17 (1958). (Emphasis added).

Admittedly, appellants do not have any direct proof

that Altheimer required that they pay tuition as a conse

quence of Linda’s choice to attend a white school—such

proof can rarely be found in any case. No official of

Altheimer actually told appellants that the reason they

were being charged tuition was Linda’s choice to attend

a formerly all-white school. However, the following cir

cumstances surrounding the decision to charge appellants

tuition, require that one draw the inescapable conclusion

that the decision was in retaliation of Linda’s attempt to

break out of Altheimer’s traditional segregated educational

pattern and was an attempt to discourage any Negroes

who in the future might wish to choose to attend a white

school:

1. Appellants have lived with their grandfather in

Altheimer as long as they can remember and have attended

the public schools (although these schools were Negro

schools) without the payment of tuition (R. 31-32 and

R. 137-138);

15

2. Appellants were charged tuition two days after Linda

exercised her choice to attend the white high school (R.

135);

3. There are, known to officials of Altheimer, many

other children who live in the district with persons other

than their parents and this is the first and only time that

Altheimer has ever charged tuition to persons living

within the boundaries of the district (R. 29; 58 and 86);

4. Altheimer failed to conduct any real investigation to

ascertain where the appellants resided:

a. No Altheimer official ever asked Mrs. Johnson (ap

pellants’ mother) whether appellants resided with

her (R. 67);

b. No Altheimer official ever asked Mr. Spriggs (ap

pellants’ grandfather) whether appellants resided

with him;

c. Altheimer decided to charge appellants tuition on

the basis of a single report of Mr. Martin (Princi

pal of Martin School) (R. 80); and

d. As had been done in the past for a white pupil

(R. 89), Altheimer failed to advise Mr. Spriggs

that some legal guardian relationship must be es

tablished between him and the appellants or tuition

would be charged them.

For these reasons, together with Altheimer’s past his

tory of racially segregated education, manifested as late

as April 12, 1967, appellants submit that there is ample

evidence to show that Altheimer imposed a tuition require

ment upon appellants and denied them transportation

because Linda Ann Johnson chose to attend a previously

all-white high school in the district.

16

n.

Minor Appellants Are Residents of the Altheimer,

Arkansas School District No. 22.

The State of Arkansas guarantees a child the right to

free public education in that district in which the child

resides. Section 80-1501 of the Arkansas Annotated Stat

utes provides:

The public schools of any school district shall be

open and free to all persons between the ages of

six [6] and twenty-one [21] years, residing in that

district, and the directors of any district may permit

older or younger persons to attend the schools under

such regulations as the State Board of Education

may prescribe. (Emphasis added)

The test is not where the child is domiciled nor where

the parents reside, but where the child resides. Any defini

tion of residency which would make the residence of the

parents determinative is arbitrary, unreasonable and viola

tive of the equal protection of law clause, as has been

discussed.

Residence and domicile are not synonymous. Stephens

v. AAA Lumber Co., 238 Ark. 842, 384 S.W.2d 943, 945

(1964). It is possible for one to have more than one resi

dence at the same time. In re Watson, 99 F.Supp. 49, 53

(W.D. Ark. 1951). Webster’s dictionary defines residence as

the “act or fact of abiding or dwelling in a place for some

time; act of making one’s home in a place.” In Krone v.

Cooper, 43 Ark. 547 (1884), one of the earliest Arkansas

cases discussing residence, the court stated that “residence

[in this case in contemplation of the attachment laws]

implies an established abode fixed permanently for a

17

time for business or other purposes although there may

be an intent existing all the time to return at some time

or other to the true domicile . . . ” p. 551. Also see Brigham

v. Brigham, 229 Ark. 967, 319 S.W.2d 844, 847 (1959)—resi

dency is largely a matter of intent; Central Manufacturers

Mut. Ins. Co. v. Friedman, 213 Ark. 9, 209 S.W.2d 102, 103

(1948)—residence and place of abode are synonymous;

Husband v. Crockett, 195 Ark. 1031, 115 S.W.2d 882 (1938).

Minor appellants have lived with Joseph Spriggs, their

grandfather, a long time resident of Altheimer, for most

of their natural lives (E. 31). The fact that minor appel

lants may visit their mother in the adjoining district oc

casionally cannot negate their residence with their grand

father. Certainly, this Court would not have minor children

visit their mother only at the peril of being denied their

right to a free public education in the district in which

they live. The proximity (4 miles) of appellants’ mother

makes it even more unnatural for them not to visit her

(E. 72).

Altheimer’s tuition policy, as interpreted by the Chair

man of its Board, is to provide free public education for

all pupils who reside within the district regardless of

whether such residence is with a natural parent if the

pupil living in the district does not return to his parents’

home after the close of the school term (E. 23). There was

absolutely no testimony that any of the minor appellants

ever returned to their mother’s home at the end of the

school term. Further, minor appellants are not in the

district solely to avail themselves of alleged superior

education since their mother has testified that they would

be living with her except for the fact that she is unable

to care for them because she is required to work (E. 102).

Finally, it has been demonstrated that no school official

ever asked Mrs. Johnson whether her children resided with

18

her (T. 56) and neither was Mr. Spriggs asked if his

grandchildren resided with him. Instead, based solely on

Mr. Martin’s report to the Superintendent of Schools

after he took the census enumeration, minor appellants

were notified within two days after Linda chose to attend

the previously all-white Altheimer school (E. 135) that

they would have to pay tuition at the rate of $20.00 per

month to attend the public schools since they had been

found to be non-residents of the district.

Appellants submit that they have demonstrated that

minor appellants live with their grandfather in Altheimer,

have been living with him for a number of years, and have

no intention of leaving his abode; therefore, minor appel

lants are clearly residents of Altheimer School District

and as such are entitled to attend the public schools of

that district without the payment of tuition.

m .

Although Residency Is Determined by State Law, the

District Court Can Apply That Law in an Action Where

Appellants Have Raised, and Supported With Testi

mony, Substantial Federal Claims.

The Honorable Oren Harris, in his decision dismissing

appellants’ complaint, stated: “ [T]he state law provides

a method of determination of the residence of the students

within a school district.” He went on to say: “ [C]ertainly

proper determination may be made by proper forum

as to the legal residence of any person and there are

legal procedures in the state for such determination” (R.

144). If, by these statements, Judge Harris was holding

that the question of residence since it involves an applica

tion of state law should properly be presented to a state

19

court forum, appellants respectfully submit that such deci

sion was erroneous.

The substance of appellants’ complaint is that they are

residents of Altheimer, that Altheimer has deprived them

of their right to a free public education and of their

rights of due process and equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution by requiring that they pay tuition to

attend school, and that Altheimer has imposed these tuition

and transportation requirements upon them for the pur

pose of punishing Linda Ann Johnson for-exercising her

choice to attend a predominantly white school and for the

purpose of discouraging other persons similarly situated

from making a choice to attend predominantly white schools

(R. 3). Although the meaning of residence must be re

solved by an application of state law, it was an error for

the court to refuse to apply this state law in the resolu

tion of appellants’ essentially federal claims.

Indeed, even if appellants asserted a state law claim for

relief along with a federal ground for relief, if these two

distinct grounds were in support of a single cause of

action a federal court through the application of pendent

jurisdiction could dispose of the case upon a nonfederal

ground though the federal ground may not have been es

tablished. See Hum v. Oursler, 289 U.S. 238 (1932), and

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966).

However, the appellants are not even seeking a state

remedy but instead ask for a declaratory judgment and

injunction enjoining Altheimer from pursuing those poli

cies which they claim deny them federal constitutionally

protected rights. Implicit in a decision on these claims is

a determination of whether Altheimer’s tuition policy either

on its face or as applied contravenes these rights as as-

serted by appellants. In rendering this decision, although

a question of state law may have to be resolved, a federal

court is authorized and indeed must apply the state law.

Erie Ry. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938).4

CONCLUSION

W herefore, appellants pray that the judgment below be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

George H oward, Jr.

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

Jack Greenberg

M ichael Meltsner

Gabrielle A. K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

4 Thompson v. Shapiro, Civil Action No. 11,821 (D.C. Conn., June 19,

1967) and Green, et al. v. The Department of Public Welfare of the

State of Delaware, et al., Civil Action No. 3349 (D.C. Del., June 28, 1967),

recent district court cases invalidating residence as a requirement for the

receipt o f welfare benefits lend support to appellants’ contention that

the existence of a question o f residence which is normally resolved through

the application of state law cannot deprive a federal court of jurisdic

tion to resolve a substantial federal claim.

21

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the ------ day of September,

1967, I served a copy of the foregoing Appellants’ Brief

upon C. Harley Cox, Jr., Esq., Coleman, Gantt, Ramsay,

and Cox, Simmons National Building, Pine Bluff, Ar

kansas, attorney for appellees, by mailing a copy thereof

to him at the above address via United States mail, postage

prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .« @ * > 2 1 9