Covington v. Edwards Brief and Supplemental Appendix of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Covington v. Edwards Brief and Supplemental Appendix of Appellees, 1958. 1d35b584-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d2eb2116-6021-4221-8767-a0108bf2a7e5/covington-v-edwards-brief-and-supplemental-appendix-of-appellees. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

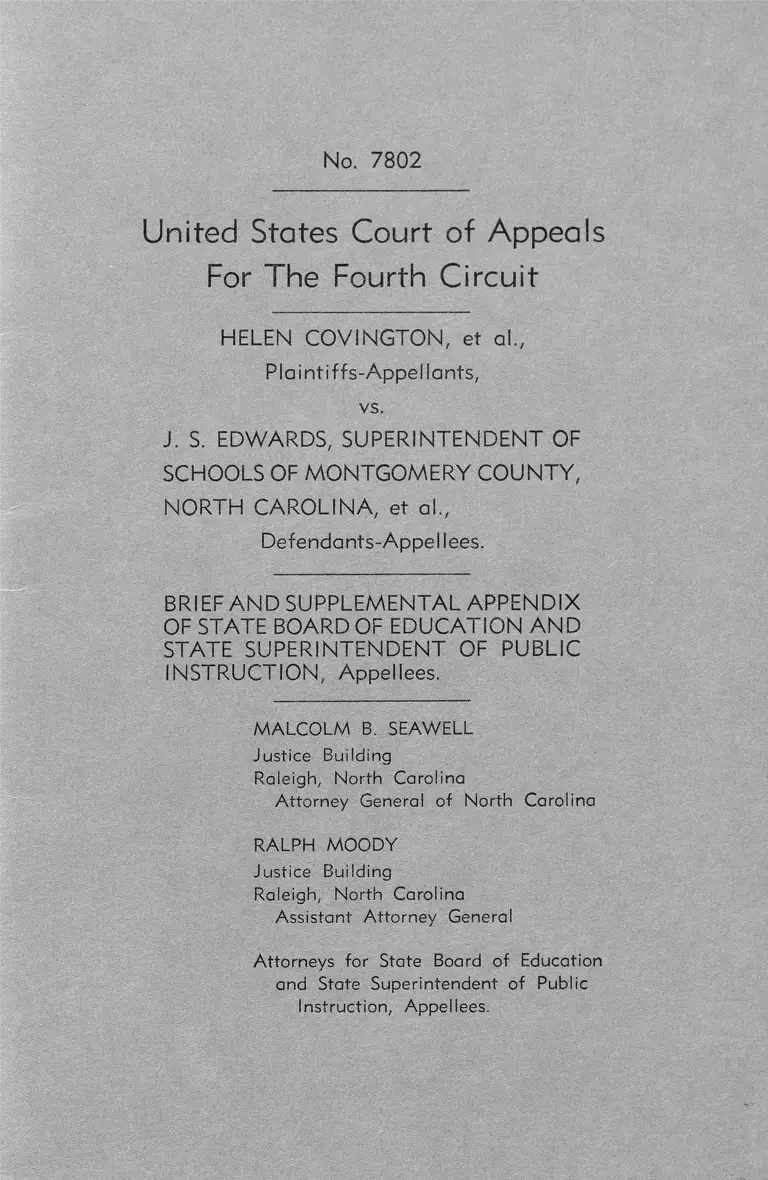

No, 7802

United States Court of Appeals

For The Fourth Circuit

HELEN COVINGTON, et al.;

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

J. S. EDWARDS, SUPERINTENDENT OF

SCHOOLS OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY,

NORTH CAROLINA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF AND SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX

OF STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION, Appellees.

MALCOLM B. SEAWELL

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina

Attorney General of North Carolina

RALPH MOODY

Justice Building

Raleigh, North Carolina

Assistant Attorney General

Attorneys for State Board of Education

and State Superintendent of Public

Instruction, Appellees.

I N D E X

Statement of the Case................................................... 1

Questions Presented .............................................................................. 3

Statement of Facts ................................................................................ 3

Argument ........................................................................................... 3

I. Plaintiffs-Appellants Having Failed To Exhaust

The State’s Administrative Remedy, The District

Judge Was Correct In Dismissing The A ction .............. 5

II. The Members Of The State Board Of Education

And The State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion have Nothing to Do With The Assignment Of

Pupils In Local Schools And Are Not Indispens

able And Necessary Parties To This A ction .................. 9

III. Plaintiffs-Appellants Have No Legal Status To

Attack The Constitutionality Of The Various

Statutes Which Comprise the So-Called “Pearsall

Plan” ...................................................................................... 25

IV. The Motion to Dismiss Filed by These Appellees

Should be Sustained Because the Supplemental and

Amended Complaint Does Not Allege Any Cause

of Action Against State Officers...................................... 29

Conclusion.............................................................................. ................ - 31

Appendix (Special Appearance and Motion) ............ .............. - ....... 33

TABLE OF CASES

Acheson, Topeka & S. Fe R. Co. v. Matthews, 174 IJ. S. 96,102 ....... 18

Adkins v. School Board of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430;

aff’d. 246 F. 2d 325 ......................................................................... 6

Alabama State Fed. of Labor v. McAdory, 325 U. S. 450, 461;

89 L. ed. 1725, 1734 ......................................................................... 27

Arizona v. California, 283 U. S. 423, 455 ........................ ....................... 18

Ashwander v. T. V. A., 297 U. S. 288, 324, 80 L. ed. 688, 699 ...... 28

Atkins v. McAden, 229 N. C. 752, 757 .................................................. 14

J

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School Dist., 241 F 2d 230 ...... 6

Bailey v. Richardson, 182 F. 2d 46, 62, aff’d. 341 U. S. 918......... 18

Baird v. Peoples Bk. & Trust Co., 120 F. 2d 1001................................ 22

Blue v. Durham Public School District, 95 F. Supp. 441, 443 .......10, 19

Board of Education v. Walter, 198 N. C. 325, 328, 330 ..................... 14

Board of Health v. Commissioners, 173 N. C. 250 ............................. 29

Bode v. Barrett, 344 U. S. 583; 97 L. ed. 567, 571 ................................ 27

Branch v. Board of Education, 233 N. C. 623, 625 ............................ 15

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 ........................................................ 6

Brown v. Ford Motor Co., 48 F. 2d 732 ........ .................................... 30

Brunnell v. United States, 77 F. Supp. 68 ............................................ 30

Butler v. Thompson, 97 F. Supp. 17, a ff d. 341 U. S. 937 ................ 18

Calder v. Michigan, 218 U. S. 591, 598 ................................................... 18

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789 .... 7

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 .......................................................... 8, 9

Coggins v. Board of Education of Durham, 223 N. C. 763 .......... 13, 14

Cohn v. Public Housing Administration, 257 F. 2d 73, 78 ..............6, 7

Cohn v. United States, 129 F. 2d 730 .................................... ........ ...... 30

C. I. O. v. McAdory, 325 U. S. 472, 475, 89 L. ed. 1741 ...................... 28

Collie v. Commissioners, 145 N. C. 170, 176 ............. .................. 14

Colorado v. Toll, 268 U. S. 228, 69 L. ed. 927 ................................ 22, 23

Columbus & G. R. Co. v. Miller, 283 U. S. 96, 99; 75 L. ed. 861, 865 .... 28

Conductors of America v. Gorman, 133 F. 2d 273 ......................... 20, 22

Connor v. Board of Commissioners of Logan County, Ohio,

12 F. 2d 789, 795 .............................................................................. 19

Conrad v. Board of Education, 190 N. C. 389, 396 ............................. 14

Constantian v. Anson County, 244 N. C. 221, 93 S. E. 2d 163 ....10, 14, 22

County of Platte v. New Amsterdam Casualty Co., et als., 6

F. R. D. 475 ....................................................................................... 21

Covington v. Edwards, 165 F. Supp. 957 ........................................2, 10

Covington v, Montgomery County School Board, 139 F. Supp.

161 ............................. ..................................................................... . 2

n

Currier v. Currier, D. C. N. Y., 1 F, R. D. 683 ................................ 21

Dahnke v. Bondurant, 257 U. S. 282, 289; 66 L. ed. 239, 243 .............. 28

Daniel v. Family Security Life Ins. Co., 336 U. S. 220 ........ - ........... 18

Davenport v. Board of Education, 183 N. C. 570 ...................... .......... 14

Dean Oil Co. v. American Oil Co., 147 F. Supp. 414, 417..................... 28

Doremus v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 429, 434; 96 L. ed.

475, 480; 72 S. Ct. 394; 50 L. ed. 382 ............................................... 28

Doyle v. Continental Ins. Co., 94 U. S. 535, 541; 24 L. ed. 148........ 17

Ducker v. Butler, et al., 70 App. D. C., 103, 104 F. 2d 236, 238 ........ 20

Duke Power Co. v. Greenwood County, 91 F. 2d 665 ......................... 18

Fitzgerald v. Jandreau, 16 F. R. D. 578 ............................... ............... 22

Frasier v. Board of Trustees of the University of North Caro

lina, 134 F. Supp. 589, 593 .............................................................. 8

Frasier v. Commissioners, 194 N. C. 49, 62 ........................................ 14

Gallup v. Caldwell, 120 F. 2d 9 0 ............................................................ 30

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 246 F. 2d 913......................... 6

Green v. Brophy, 110 F. 2d 539 ............................................................ 30

Helvering v. Griffiths, 318 U. S. 371 ................................................... 18

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816, 824, 70 S. Ct. 843; 94

L. ed. 1302 ................................................................................. ...... 8

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach County,

258 F. 2d 730 ....................................................................................5, 6

Holliday v. Long Manufacturing Co., 18 F. R. D. 45 ......................... 22

Holt v. Raleigh City Board of Education, 164 F. Supp. 853 ........ 10, 15

Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District

232 F. 2d 627, cert. den. 352 U. S. 870, 1 L. ed. 2d 76 ................ 9

Howell v. Howell, 151 N. C. 575, 581 ................................................... 14

Hynes v. Grimes Packing Co., 337 U. S. 86, 93 L. ed. 1231.............. 24

In Re Application for Reassignment, 247 N. C. 413....................... . 15

In Re Assignment of School Children, 242 N. C. 500 ..................... 15

In Re Doyle, 257 N. Y. 244, 177 N. E. 489, 87 A. L. R. 418, 49

Am. Jur. sec. 36, 81 C. J. S. sec. 40; 82 C. J. S. sec. 2 0 ........ 16

iii

Insurance Co. of New York v. Fire Association of Philadelphia,

152 F. 2d 239 ....................................................... .............................. 29

Insurance Society v. Brown, 213 U. S. 25, 29 S. Ct. 404 ..................... 29

Jeffers v. Whitley, 165 F. Supp. 951 ................................................... 10

Jeffrey Manufacturing Co. v. Blagg, 235 U. S. 571, 576; 59 L.

ed. 364, 368 ......................................................................................... 28

Joyner v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 244 N. C.

164, 92 S. E. 2d 795 ......................................................................... 7

Kelly v. Board of Instruction of the City of Nashville, 159

F. Supp. 272 ...................................................................................... 5

Keys v. United States, 119 F. 2d 444, 447 ........................................... 30

Kirby v. Board of Education, 230 N. C. 619 ........................................ 14

Kistler v. Board of Education, 233 N. C. 400, 404, 407 ..................... 14

Kuhn v. Yellow Transit Freight Lines, 12 F. R. D. 252 ..................... 20

Lacy v. Bank, 183 N. C. 373, 378 .......................................................... 13

Lane v. Graham Co., 194 N. C. 723 ....................................................... 29

Larsen v. City of Colorado Springs, 142 F. Supp. 871, 873 .............. 28

LeClair v. Swift, 76 F. Supp. 729 .......................................................... 30

Lovett v. United States, 66 F. Supp. 142, 145 .................................... 19

Lucking v. Delano, 129 F. 2d 283, 286 ............................................... . 29

Massachusetts v. Melon, 262 U. S. 447, 484; 67 L. ed. 1078, 1084 ....... 28

Mills v. Lowndes, 26 F. Supp. 792 ....................................................... 22

Missouri v. Holland, 252 U. S. 416, 431; 64 L. ed. 641, 646;

11 A. L. R. 984; 40 S. Ct. Rep. 382 ............................................... 23

Moore v. Board of Education, 212 N. C. 499, 502 ................................ 14

Moore Ice Cream Co. v. Rose, 289 U. S. 373, 383, 384 ......................... 28

Mclnnish v. Board of Education, 187 N. C. 494, 495 ......................... 14

McRanie v. Palmer, 2 F. R. D. 479 ...................................................... 19

Newport News Co. v. Schuffler, 303 U. S. 54, 57 ............................... 30

Niles-Bement-Pond Co. v. Iron Moulders’ Union, 254 U. S. 77,

80, 41 S. Ct. 39, 41; 65 L. ed. 145 ................................................... 20

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156, 164 .................. 9

Iv

Pacific States v. White, 296 U. S. 176, 185 ........................................... 30

Parker v. Anson County, 237 N. C. 78, 86 ........................................... 14

Pellican Oil & Gasoline Co. v. Commissioner of Internal

Revenue, 128 F. 2d 837 ................................................................. 30

Peterson v. Parsons, 73 F. Supp. 840 ............................................... 18

Philadelphia Co. v. Stimson, 223 U. S. 605, 619, 620; 56 L.

ed. 570, 576, 577; 32 S. Ct. Rep. 340 ............................................... 23

Photometric Products Corp. v. Radtke, 17 S. R. D. 103.................. 22

Porter v. Karadas, 157 F. 2d 984 .......................................................... 29

Premier-Pabst Sales Co. v. Grossup, 298 U. S. 266, 227; 80 L.

ed. 1155, 1156 .................................................................................... 28

Prudential Ins. Co. of America v. Carlson, 126 F. 2d 607 .................. 30

Pullman Co. v. Richardson, 261 U. S. 330; 67 L. ed. 682 .................. 28

Rast v. Van Deman & L. Co., 240 U. S. 342, 357, 366 ......................... 18

Samuel Goldwyn, Inc. v. United Artists Corp., 3 Cir., 113 F.

2d 703 ................................................................................................. 21

Savoi Films A. I. v. Vanguard Films, 10 F. R. D. 6 4 ..................... 20

School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Va., v. Allen, 240 F.

2d 5 9 .................................................................................................. 6, 9

School Board of the City of Newport News, Va., v. Adkins, 246

F. 2d 325 ........................................................................................... 6

School Committee v. Taxpayers, 202 N. C. 297, 299 ......................... 14

Shields v. Barrow, 17 How. 130, 139, 15 L. ed. 158.........................19, 21

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp.

372, Motion to Affirm granted 3 L. ed. 2 and 5 ......................... 16

Smith v. School Trustees, 141 N. C. 143 ........................................... 14

So. Ry. Company v. King, 217 U. S. 524; 30 S. Ct. 594 ................... 29

Standard Stock Food Co. v. Wright, 225 U. S. 540, 550; 56 L.

ed. 1197, 1201 .................................................................................... 27

State Bank v. Weaver, 282 U. S. 765 ............................................... 30

State of Washington v. United States, et al., 9 Cir., 87 F. 2d 421....... 20

Stephenson v. Binford, 287 U. S. 241 ........................................... 18, 27

v

Sweatt v. Board of Education, 237 N. C. 653, 656 ............................. 14

Tate v. Board of Education, 192 N. C. 516, 520 ................................ 14

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U. S. 357 ................................................... 18

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington County, 144

F. Supp. 239 ................. 6

Tileston v. Ullman, 318 U. S. 44, 46; 87 L. ed. 603 ............................. 28

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75, 89; 91 L. ed.

754, 766 ............................................................................................... 26

United States v. Appalachian Power Co., 311 U. S. 377, 423; 85

L. ed. 243, 261 .................................................................................. 28

United States v. Des Moines Nav. & R. Co., 142 U. S. 510, 554 ...... 18

United States v. Petrosky, 2 F. R. D. 422 ............................................ 22

United States v. Washington Institute of Technology, 3 Cir.,

138 F. 2d 25 ...................................................................................... 21

Watson v. Buck, 313 U. S. 387, 402; 85 L. ed. 1416, 1424 ...................... 27

Weber v. Freed, 239 U. S. 325, 330 ...................................................... 18

West v. Lee, 224 N. C. 79 ..................................................................... 14

Williams v. Fanning, 332 U. S. 490; 92 L. ed. 95; 68 S. Ct. 188 .....24, 25

Williams v. Kansas City, Mo., 104 F. Supp. 848, 854 ......................... 23

Wyoga Gas & Oil Corp. v. Schrack, et al., D. C. 27 F. Supp. 35 .... 20

Young v. Garrett, 8 Cir., 149 F. 2d 223 ............................................... 21

S T A T U T E S

Article 2, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C..................... 34

Article 3, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C..................... 34

Article 7, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C.................... 12

Article 9, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C..................... 12

Article 17, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C.................... 12

Article 20, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C................11, 12

Article 21, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C.........11, 34, 37

Article 22, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C.................... 12

vi

Article 34, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C........11, 34, 36

Article 35, Chapter 115 of the General Statutes of N. C........11, 34, 36

General Statutes of N. C., sec. 115-27.................................................. 12

General Statutes of N. C., sec 115-35.................................................. 12

General Statutes of N. C., sec. 115-51 ................................................. 12

General Statutes of N. C., sec. 115-53.................................................. 12

(All General Statutes Citations Refer to Cumulative

Supplement of 1957)

Resolution 4, Session Laws of 1956 (Extra Session) ..................... 16

Resolution 29, Session Laws of 1955 ................................................... 16

28 U. S. C. A. 1652 .................................................................................. 10

MISCELLANEOUS

11 A. L. R. 984 ......................................................................................... 23

87 A. L. R. 418 ....................................................................................... 16

158 A. L. R. 1126 .................................................................................... 25

11 Am. Jur. p. 748, sec. I l l .................................................................. 25

49 Am. Jur. sec. 36 ................................................................................ 16

Barron & Holtzoff, F. P. P., p. 81, sec. 515........................................... 25

Constitution of Alabama (1901) sec. 4 5 .............................................. 16

Constitution of North Carolina, Article I, secs. 3 & 5 ......................... 11

Constitution of North Carolina, Article IX, sec. 2 ..................10, 22, 34

Constitution of United States, Article I I I ........................................... 26

Constitution of United States, Article VI ....................................11, 17

16 C. J. S., sec. 76, p. 226 ..................................................................... 25

81 C. J. S„ sec. 4 0 .................................................................................... 16

82 C. J. S., sec. 20 .................................................................................. 16

Moore’s Federal Practice................................................................. 19, 21

vii

No. 7802

United States Court of Appeals

For The Fourth Circuit

HELEN COVINGTON, et al„

Piaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

J. S. EDWARDS, SUPERINTENDENT OF

SCHOOLS OF MONTGOMERY COUNTY,

NORTH CAROLINA, et at.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURl

OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CARO

LINA, ROCKINGHAM DIVISION.

BRIEF AND SUPPLEMENTAL APPENDIX

OF STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION, Appellees.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The plaintiffs originally instituted this action against the

Superintendent of Schools of Montgomery County and against

the Board of Education of Montgomery County. The plaintiffs

did not allege in their original complaint, or in any of their

amendments to the original complaint, nor do they allege in

their Amended and Supplemental Complaint (Appellants

Appendix, p. 39a) that they ever at any time exhausted the

State’s administrative remedy provided for the assignment

and enrollment of pupils. Nowhere in the pleadings do the

2

plaintiffs-appellants allege that any of the pupils named as

plaintiffs in the complaint desire to be admitted to any specific

public school in Montgomery County. For some reason coun

sel for plaintiffs-appellants have been working hard to obtain

a 3-Judge Court as witness their Amendment of December 16,

1955 (Appellants’ Appendix, pp. 33a, 35a, 50a) and when this

was denied (COVINGTON v. MONTGOMERY COUNTY

SCHOOL BOARD, 139 F. Supp. 161) counsel for the plaintiffs-

appellants then filed a Motion for Leave to File an Amended

and Supplemental Complaint and to make the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion parties defendant (Appellants’ Appendix pp. 36a, 39a).

The Motion for Leave to File an Amended and Supplemental

Complaint and add parties defendant was filed on September

13, 1956. The matter was not immediately heard, and on

March 26, 1958, the Attorney General of North Carolina in

behalf of the State Board of Education and the State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction entered a special appearance

and opposed plaintiffs’ motion. The special appearance enter

ed by the Attorney General, as well as the Answer to the

Motion of plaintiffs, appears in the Supplementary Appendix

to this Brief on p. 33. This matter was heard upon the motions

on March 26, 1958, and the Attorney General was ordered to

file a brief as to his positions on all the issues raised in the

pleadings. On October 6, 1958, the Judge of the District Court

of the United States for the Middle District entered judgment

dismissing the action, denying the Motion to File the Amend

ed and Supplemental Complaint, and also denied the Motion

to Add the State Board of Education and the State Superinten

dent of Public Instruction as parties defendant (Appellants’

Appendix, p. 55a). The District Judge issued an Opinion,

giving his legal reasons for the Judgment, which is reported

as COVINGTON v. EDWARDS, 165 F. Supp. 957.

While the Attorney General believes that any adequate

reason for the dismissal of this action as to the County School

Board and County Superintendent is available also in his

behalf for the benefit of the State officers, it is further urged,

however, and, it will be the Attorney General’s position in

3

this brief, that under the constitution and laws of North

Carolina pertaining to the public schools the State officers

have nothing to do with the cause of action alleged against

the County Board and the County Superintendent, and, there

fore, the ruling of the District Judge dismissing the Motion

as to the State officers is correct.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

These appellees submit that the dominant questions which

are decisive of this case are as follows:

(1) Under existing decisions of the Circuit Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit can plaintiffs maintain this action

without exhausting the administrative remedy provided by

the State statute?

(2) Under the Constitution and Laws relating to the public

school system of North Carolina are the members of the State

Board of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction indispensable or necessary parties defendant in

this case?

(3) Can the plaintiffs attack the constitutionality of State

statutes which have never been applied to their status or

situation by any process of administration?

(4) Do the allegations of the plaintiffs’ Amended and Sup

plemental Complaint state a cause of action as against these

appellees?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

As heretofore pointed out, plaintiffs instituted this suit as

a class action against the Superintendent of Schools of Mont

gomery County and the Board of Education of Montgomery

County. In their original complaint the plaintiffs allege that

the Board of Education of Montgomery County “maintains

and generally supervises certain schools in said County for

4

the education of white children exclusively and other schools

in said County for the education of Negro children exclusive

ly.” In paragraph VIII of the original complaint it was alleged

that the customs, practices and usages of the Montgomery

County school officials, as applied to the plaintiffs, deprived

them of constitutional rights in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment (Appellants’ Appendix, pp. 7a, 8a). The Court

will further note that counsel for the plaintiffs kept amend

ing their complaint in their efforts to secure a 3-Judge Court

and finally wound up with this Motion to File an Amended

and Supplemental Complaint and make the State officers

parties defendant.

Appellants’ statement in their Brief that “The North Caro

lina Advisory Committee on Education petitioned the Court

for the right to appear in this case, take depositions and other

wise participate” is not correct. The Court will note on p. 28a

of Appellants’ Appendix that this Committee merely asked

that its counsel be present at any legal proceedings in the

action, including the taking of depositions and other prelim

inary hearings. It is very plain that the Advisory Committee

did not ask to take any depositions but wanted to be present

when depositions were taken. The Court will further see on

p. 29a of Appellants’ Appendix that the District Judge merely

signed an Order allowing counsel for the Advisory Committee

to be present “during any legal proceedings or preliminary

hearings in the above entitled action.” On p. 32a of Appellants’

Appendix the Court will see that the District Judge amended

the Order and allowed members of the Advisory Committee,

as well as counsel, simply to be present during any legal

proceedings.

If the Court will examine paragraphs 2, 3 and 4 of the

Motion for Leave to File Supplemental Complaint and Add

Parties Defendant (Appellants’ Appendix, p. 36a) the Court

will see that it is nowhere alleged in the Motion that the State

officers administer the enactments complained about nor is it

alleged how or why the members of the State Board of Educa

tion and the Superintendent of Public Instruction have now

5

become necessary parties. It is alleged in the Amended and

Supplemental Complaint in Paragraph IVb (Appellants’ Ap

pendix, p. 42a) that the State officers who are members of

the State Board of Education “are charged with the general

supervision and administration of a free public school system

of said State” but this is merely some phraseology taken from

the Constitution and statutes of the State and does not take

into account the other statutes which vest certain sole and

exclusive powers in the city and county administrative units.

It is now alleged for the first time, in Paragraph VI of the

Amended and Supplemental Complaint, that the Montgomery

County Board of Education refuses to desegregate its schools

“pursuant to orders, resolutions or directives of the State

Board of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion.” This allegation is on information and belief, and no

order or resolution or directive is designated or referred to.

The allegations as to the so-called “Pearsall Plan” , referring to

certain Acts passed by the General Assembly of North Caro

lina, do not charge that these appellees have acted thereunder

to deprive the plaintiffs of any constitutional rights. When the

plaintiffs get to the actual paragraph in which it is alleged

that their constitutional rights have been violated (see Par

agraph VIII) these charges are made against the Montgomery

County school officials and not these appellees, whom, they

say, they should make parties defendant.

ARGUMENT

I

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS HAVING FAILED TO EX

HAUST THE STATE’S ADMINISTRATIVE REMEDY,

THE DISTRICT JUDGE WAS CORRECT IN DISMISS

ING THIS ACTION.

Counsel for the appellants attempt to bring this case within

the purview of certain rulings in other circuits (HOLLAND

v. BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF PALM BEACH

COUNTY, 258 F. 2d 730 - 5th Circuit, 1958; KELLY v. BOARD

OF INSTRUCTION OF THE CITY OF NASHVILLE, 159 F.

6

Supp. 272 - M. D. Term., 1958; GIBSON v. BOARD OF PUB

LIC INSTRUCTION, 246 F. 2d. 913 - 5th Cir., 1957). To this

line of cases we could also add the Virginia cases where the

administrative remedy and the placement statute were held

to be unconstitutional and totally inadequate (ADKINS v.

SCHOOL BOARD OF NEWPORT NEWS, 148 F. Supp. 430;

affirmed 246 F. 2d 325 - 4th Cir.). In the case of GIBSON v.

BOARD OF INSTRUCTION, supra, the Board of Public In

struction of Dade County, Florida, had passed a resolution

saying: “Until further notice the free school system of Dade

County will continue to be operated, maintained and conduct

ed on a nonintegrated basis.” This Court has always said

(SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF CHARLOTTESVILLE,

VIRGINIA, v. ALLEN, 240 F. 2d 59 - 4th Cir., 1956) that

where an application, because of a preconceived order, resolu

tion or policy, would always result in a referral to a segregated

school, the proceedings would be futile. The case of HOL

LAND v. BOARD OF INSTRUCTION OF PALM BEACH

COUNTY, supra, is in the same category. It is quite evident

that in the Holland case there was a strong feeling that the

school districts had been gerrymandered and arranged so as

to provide for segregated schools, and the Court of Apeals for

the 5th Circuit, therefore, said:

“ In the light of compulsory residential segregation of the

races by city ordinance, it is wholly unrealistic to assume

that the complete segregation existing in the public

schools is either voluntary or the incidental result of valid

rules not based on race.”

Several cases have interpreted the meaning of the Brown

case, and these interpretations have been given approval by

this Court (SCHOOL BOARD OF CHARLOTTESVILLE,

VIRGINIA, v. ALLEN, 240 F. 2d 59, 62; BRIGGS v. EL

LIOTT, 132 F. Supp. 776; AVERY v. WICHITA FALLS IN

DEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, 241 F. 2d 230; THOMP

SON v. COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ARLINGTON COUN

TY, 144 F. Supp. 239; SCHOOL BOARD OF CITY OF NEW

PORT NEWS, VIRGINIA, v. ADKINS, 246 F. 2d 325;

COHN v. PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, 257 F. 2d

7

73, 78). The controlling principles in all these decisions are

to the effect that: “The Constitution, in other words, does not

require integration. It merely forbids discrimination. It does

not forbid such segregation that occurs as the result of volun

tary action. It merely forbids the use of governmental power

to enforce segregation.” And, further: “No general reshuffling

of the pupils in any school system has been commanded. The

order of that Court is simply that no child shall be denied

admission to a school on the basis of race or color.*** Con

sequently, compliance with that ruling may well not neces

sitate such extensive changes in the school system as some

anticipate.” And, further, (COHN v. PUBLIC HOUSING

ADMINISTRATION, supra,) the Circuit Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit says: “Neither the Fifth nor the Fourteenth

Amendments appears postively to command integration of

the races but only negatively to forbid governmentally enforc

ed segregation.”

We think that the litigation connected with the McDowell

County School is decisive of this point. In the first action

(CARSON v. BOARD OF EDUCATION of McDOWELL

COUNTY, 227 F. 2d 789) a large group of Negro children

brought an action before the Brown case was decided in which

they asked for substantially equal facilities. This was dismis

sed on the ground that the decision in the Brown case made

inappropriate the relief prayed for. This Court remanded the

case, saying that the District Judge should consider not only

the decision of the Supreme Court but also the administrative

remedy provided by the State, and this Court further said that

the administrative remedy must be exhausted. Thereafter

(May 23, 1956) the Supreme Court of North Carolina inter

preted the Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils Act of the

State (JOYNER v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF Mc

DOWELL COUNTY, 244 N. C. 164, 92 S. E. 2d 795). The Su

preme Court of North Carolina decided that under the statute

school children could not apply for admission to any schools

en masse but that applications must be prosecuted in behalf of

the child or children by the interested parent, guardian, etc. of

such child or children respectively and not collectively. In

other words, the application of each child must be considered

on an individual basis. The fact that an applicant is colored

does not remove or do away with the eligibility conditions that

are applicable to all children irrespective of color (FRASIER

v. BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

NORTH CAROLINA, 134 F. Supp. 589, 593). After the de

cision of the Supreme Court of North Carolina the applicants

in the McDowell County case applied to this Court for a man

damus (CARSON v. WARLICK, 238 F. 2d 724-4th Circuit). In

this application it was alleged that the Board of Education of

the County was exercising discrimination on the grounds of

race in refusing to admit them “to schools maintained in the

Town of Old Fort.” This Court quoted from the opinion of the

Supreme Court of North Carolina and stated in substance that

the applicants had not attempted to comply with this statute

but had merely written the Secretary of the Board of Educa

tion a letter inquiring as to the steps being taken for the

admission of the Negro children to the Old Fort School. The

Secretary replied that no application had been made under the

the statute. The applicants then made a Motion to File a

Supplemental Complaint, and without alleging compliance

with the statute, as interpreted by the Supreme Court of North

Carolina, they asked for a declaratory judgment, and this was

declined by the District Judge who stayed proceedings and

ordered that the administrative remedies be exhausted. This

Court held that the administrative remedy must be exhausted

and denied the application for a mandamus, saying:

“There is no question as to the right of these school

children to be admitted to the schools of North Carolina

without discrimination on the ground of race. They are

admitted, however, as individuals, not as a class or group;

and it is as individuals that their rights under the Con

stitution are asserted. Henderson v. United States, 339

U. S. 816, 824, 70 S. Ct. 843, 94 L. ed. 1302. It is the state

school authorities who must pass in the first instance on

their right to be admitted to any particular school and

the Supreme Court of North Carolina has ruled that in

the performance of this duty the school board must pass

upon individual applications made individually to the

board.”

9

It will be seen from the Answer filed by the Board of

Education of Montgomery County (Appellants’ Appendix,

pp. 18a, 19a) that the Board used the same assignments that

they had used in the School Year 1954-1955, and they did not

say that they were going to operate segregated schools, but,

to the contrary, (p. 19a) the Board said that the parent or

guardian of any child who desired a child to be sent to another

school should file written application and the matter would

be considered by the Board as required by North Carolina

Law. It is quite evident, therefore, that the Board of Educa

tion of Montgomery County does not have any fixed policy of

segregation and the case of CARSON v. WARLICK, supra, is

decisive of this matter. Incidentally, CARSON v. WARLICK,

supra, and the principles therein set forth have been approved

in several cases (ORLEANS PARISH SCHOOL BOARD v.

BUSH, 242 F. 2d 156, 164—5th Circuit; SCHOOL BOARD OF

CITY OF CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA., v. ALLEN, 240 F. 2d

59, 64—4th Circuit; HOOD v. BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF

SUMTER COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, 232 F. 2d 627, cert,

den. 352 U. S. 870, 1 L. ed. 2d 76). It should also be noted that

the Supreme Court of the United States denied certiorari in

CARSON v. WARLICK, supra, which denial is reported in

353 U. S. 910, 1 L. ed. 2d 664.

II

THE MEMBERS OF THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

AND THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH THE

ASSIGNMENT OF PUPILS IN LOCAL SCHOOLS AND

ARE NOT INDISPENSABLE AND NECESSARY PAR

TIES TO THIS ACTION.

So far as the members of the State Board of Education and

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction are concerned

this is the important point in this case. The District Judge

(Judge Stanley) was a North Carolina lawyer before he

became Judge of the District Court of the United States, and

it is believed that he knows the legal framework of the public

school system of this State. We could very well rest our case

10

on this point with the discussion and authorities given in his

opinions (HOLT v. RALEIGH CITY BOARD OF EDUCA

TION, 164 F. Supp. 853—E. D. N. C., 1958; JEFFERS v.

WHITLEY, 165 F. Supp. 951—M. D. N. C., 1958; COVING

TON v. EDWARDS, 165 F. Supp. 957—M. D. N. C., 1958).

The Supreme Court of North Carolina has many times inter

preted the school laws of this State, and it has defined the

duties and functions of the various officers and agencies that

participate in the administration of the public school system.

To a certain extent, therefore, these appellees rely upon State

laws as Rules of Decision (28 U. S. C. A. 1652). In the case of

CON ST ANT IAN v. ANSON COUNTY, 244 N. C. 221, 93 S. E.

2d 163 (1956) the Supreme Court of North Carolina said:

“Full responsibility for the administration of school

affairs and the instruction of children within each ad

ministrative unit, including the assignment of pupils to

particular schools, rests upon the school authorities of

such units.”

Judge Johnson J. Hayes was a North Carolina lawyer before

he became District Judge and is familiar with the legal back

ground of the public school system of this State. In the case of

BLUE v. DURHAM PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT, 95 F.

Supp. 441, 443—M. D. N. C., 1951, Judge Hayes in commenting

on this situation said:

“ It appears from the foregoing statutes that the State

officials are given broad general powers over the public

school system which must be construed in connection

with statutes which confer specific authority on local

officials. The decisions of the North Carolina Supreme

Court have consistently upheld the powers of the local

authorities. * * * The mere discretionary powers of the

State officials are not to be controlled by injunctive power

of the court. It follows that the action against the state

officials must be dismissed.”

It is no longer necessary to discuss Article IX, Sec. 2, of the

Constitution of North Carolina, which provides for separate

schools for the races, because the Supreme Court of North

Carolina has said that this section is no longer valid. In

CONSTANTIAN v. ANSON COUNTY, supra, the Supreme

11

Court of North Carolina stated that it thought the question of

the administration of the State schools was a State matter,

and then said:

“However that may be, the Constitution of the United

States takes precedence over the Constitution of North

Carolina. Constitution of North Carolina, Article I, sec

tion 3 and 5; Constitution of the United States, Article

VI. In the interpretation of the Constitution of the United

States, the Supreme Court of the United States is the final

arbiter. Its decision in the Brown case is the law of the

land and will remain so unless reversed or ̂ altered by

constitutional means. Recognizing fully that its decision

is authoritative in this jurisdiction, any provision of the

Constitution or statutes of North Carolina in conflict

therewith must be deemed invalid.” (Emphasis ours)

There is no doubt but what the enrollment, assignment and

reassignment of pupils is entirely in the hands of the local

school units (Article 21 of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes,

Cumulative Supplement of 1957, Vol. 3A). There is no doubt

but what the so-called Local Option Plan, providing for an

election as to whether any particular school or schools shall

be closed, is entirely a matter in the hands of the local school

units and the voters in the various local units of the districts

(Article 34 of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes, Cumulative

Supplement of 1957, Vol. 3 A). There is no doubt but that the

administration of the expense grants is entirely in the hands

of local units except that the State Board of Education does

one thing and that is it determines “the maximum amount

of the grant to be made available to each child.” (Article 35

of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes, Cumlative Supplement

of 1957, VoL 3A). An examination of Article 20, Chapter 115

of the General Statutes, Cumulative Supplement of 1957, Vol.

3A, dealing with the compulsory attendance law, will show

that this is in the hands of the local units, and any findings

required to be made must be found and administered by the

local units.

In addition to the above, we point out some more amend

ments that have further decentralized the Public School

System of the State, as follows:

12

(1) The transportation of the pupils; in other words, the

school buses are in the hands of the local units (Article 22 of

Chapter 115 of the General Statutes, Cumulative Supplement

of 1957, Vol. 3A).

(2) State boards of education are now bodies corporate and

can sue and be sued, which was formerly not the case, but was

true and still is true of a county board of education (G. S. 115-

27).

(3) Formerly the State officials held the power of approval

of the budgets of the local units but this is not now required

(Article 9 of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes).

(4) Formerly the enforcement of the Compulsory Atten

dance Law had to be according to rules and regulations of

the State Board of Education, and while this is now true under

the present law, nevertheless, a State or county unit can put

in force higher compulsory attendance requirements and not

be subject to the rules of the State Board (Article 20 Chapter

115 of the General Statutes).

(5) County and State Boards can now divide administra

tive units into attendance areas without regard to district

lines, which power they did not have under the former law

(G. S. 115-35).

(6) Powers and duties of local school committees have

now been enlarged (Article 7 of Chapter 115 of the General

Statutes).

(7) Teachers no longer have continuing contracts (Article

17 of Chapter 115 of the General Statutes).

(8) Local boards now have authority to secure liability

insurance, waive governmental immunity and be liable to the

extent of the insurance (G. S. 115-53).

(9) Local units can now operate lunchrooms on an official

basis (G. S. 115-51).

13

There are perhaps other features that might be pointed out

which show a greater measure of local autonomy granted by

the General Assembly to county and city boards of education.

As a further indication of the judicial thinking of the State,

we submit the views of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

when the question arose as to whether or not secret societies,

known as Greek letter fraternities and sororities, could be

operated in the Public School System of Durham. The

Supreme Court of North Carolina, after laying down the

principle that city administrative units exercised the same

powers as county administrative units, then said (COGGINS

v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF DURHAM, 223 N. C. 763):

“ Each County Board of Education is vested with author

ity to fix and determine the method of conducting the

public schools in its county so as to furnish the most

advantageous method of education available to the child

ren attending its public schools. Sec. 31. It may; (1) fix

the time of opening and closing schools, sec. 32; (2)

determine the length of the school day, sec. 33; (3) en

force the compulsory school law, sec. 34; (4) provide for

the teaching of certain subjects in elementary schools,

sec. 39; (5) determine the necessity for kindergartens,

sec. 40; (6) provide for a training school for each race, sec.

41; (7) make rules and regulations not in conflict with

State law for the guidance of the County Superintendent

as the enforcement officer, sec. 47; (8) make all just and

needful rules and regulations governing the conduct of

teachers, principals, and supervisors, sec. 53; (9) provide

for the training of teachers, sec. 54. In addition it is given

general control and supervision over all matters pertain

ing to the public schools within its county, sec. 30, and

all powers and duties conferred and imposed by law

respecting public schools, which are not expressly con

ferred and imposed upon some other officials, are con

ferred and imposed upon the county board of education.

Sec. 29.”

We do not wish to multiply quotations and extend the

length of this Brief but the same views of the Supreme Court

of this State are set forth in a number of cases, which we cite

as follows:

LACY v. BANK, 183 N. C. 373, 378;

14

TATE v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 192 N. C. 516,520;

COLLIE v. COMMISSIONERS, 145 N. C. 170, 176;

McINNISH v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 187 N. C. 494,

495;

SMITH v. SCHOOL TRUSTEES, 141 N. C. 143;

DAVENPORT v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 183 N. C.

570;

HOWELL v. HOWELL, 151 N. C. 575, 581;

SCHOOL COMMITTEE v. TAXPAYERS, 202 N. C. 297,

299'

FRASIER v. COMMISSIONERS, 194 N. C. 49, 62;

BOARD OF EDUCATION v. WALTER, 198 N. C. 325,

328, 330;

CONRAD v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 190 N. C. 389,

396;

WEST v. LEE, 224, N. C. 79;

MOORE v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 212 N. C. 499, 502;

COGGINS v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 223 N. C. 763;

SWEATT v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 237 N. C, 653,

656;

KISTLER v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 233 N. C. 400,

404, 407;

CONSTANTIAN v. ANSON COUNTY, 244 N. C. 221, 225;

PARKER v. ANSON COUNTY, 237 N. C. 78, 86;

ATKINS v. McADEN, 229 N. C. 752, 757;

KIRBY v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 230 N. C. 619;

15

BRANCH v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 233 N. C. 623,

625;

IN RE APPLICATION FOR REASSIGNMENT, 247 N.

C. 413;

IN RE ASSIGNMENT OF SCHOOL CHILDREN, 242

N. C .500.

A complete history of the Assignment and Enrollment of

Pupils Act of this State and the proceedings leading up to its

adoption will be found in the case of IN RE APPLICATION

FOR REASSIGNMENT, 247 N. C. 413. There is not a single

reference to the Public School Laws of the State of North

Carolina (Chapter 115 of the General Statutes, Cumulative

Supplement of 1957) dealing with race at all, at least so far as

the colored race is concerned, and, as we pointed out when the

case of HOLT v. RALEIGH CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION

was before this Court, there have been approximately 110

applications by colored pupils for reassignment to so-called

white schools, and out of this number 15 colored students have

been admitted but two colored students later on withdrew

because of their own reasons and not by any action or com

pulsion on the part of the school authorities.

The Report of the North Carolina Advisory Committee on

Education, dated April 5, 1956, has been referred to by plain-

tiffs-appellants, and we wish to refer to certain portions of

this Report as follows:

“But we must in honesty recognize that: because the

Supreme Court is the Court of last resort in this Country,

what it has said must stand until there is a correcting

constitutional amendment or until the Court corrects its

own error. We must live and act now under the decision

of that Court. We should not delude ourselves about that.

***Defiance would alienate those who may be won to our

thinking, that separateness of the races is natural and

best. Defiance would forfeit the consideration we must

have from the Federal Judges if we are to educate our

children now. Defiance of the Supreme Court of the

United States and of the law as declared by that Court

could mean the closing of the public schools very quickly.

16

We cannot make a single plan about what we are going

to do in our schools this year without giving paramount

consideration to our relationship with the Federal

Courts.”

This same Committee, in making its recommendations to

the people of the State and the General Assembly, in Recom

mendation No. 2 said:

“ Specifically, we recommend that all school units re

cognize that since the Supreme Court decision there can

be no valid law compelling the separation of the races in

public schools.”

The plaintiffs-appellants refer to Resolution 29, which

purports to state the policy of the State as to the mixing of the

children of different races in the public schools (see Resolu

tion 29, Session Laws of 1955). They also refer to Resolution 4,

which protests the usurpation of power by the Supreme Court

of the United States (see Resolution 4, Session Laws of 1956—

Extra Session). The answer to this is that these Resolutions

did not fix the policy of the State for we have already admitted

colored children to so-called white schools. The same argu

ment was made in the case of SHUTTLESWORTH v. BIR

MINGHAM BOARD OF EDUCATION, 162, F. Supp. 372,

Motion to Affirm granted, 3 L. ed 2nd 5, and in the Shuttles-

worth case on this point the 3-Judge Federal Court said:

“With much force, the plaintiffs’ counsel point to the

Resolution of Interposition and Nullification passed by

the Special Session 1956 of the Alabama Legislature,

effective February 2, 1956. While the concluding sentence

of the resolution terms it an ‘Act’, it is in fact no more

than a joint resolution and does not have the force and

effect of law. See Alabama Constitution of 1901, Sec. 45;

In re Doyle, 257 N. Y. 244, 177 N. E. 489, 87 A. L. R. 418,

49 Am. Jur. States, etc., Sec. 36; 81 C. J. S. States Sec. 40;

82 C. J. S. Statutes Sec. 20. It amounted to no more than a

protest, an escape valve through which the legislators

blew off steam to relieve their tensions. Though defiant

in spirit, the intent expressed by the resolution was con

fined to measures ‘constitutionally available to us.’ That

resolution came before the adoption of the amendment

which eliminated from the State constitution the require-

17

ment for segregated public schools. It cannot prevail over

that amendment and over the subsequently amended and

rewritten School Placement Law. The utmost benefit of

the Interposition and Nullification Resolution to the

plaintiffs’ case is to color the construction of the School

Placement Law by its spirit of intransigence. By itself

alone, that Resolution is not enough to permit us to

declare the School Placement Law unconstitutional.

“The plaintiffs would have us conclude without further

ado ‘that the whole intent is to continue the system of

separate schools for Negro and white in the State of

Alabama’. In dealing with an Act of the legislature of a

sovereign State, we cannot lightly reach such a conclu

sion, nor, indeed, are we permitted to do so except upon

the most weighty and compelling of reasons.

“ In testing constitutionality ‘we cannot undertake a

search for motive.’ ‘If the State has the power to do an act,

its intention or the reason by which, it is influenced in do

ing it cannot be inquired into.’ Doyle v. Continental Insur

ance Co., 94 U. S. 535, 541, 24 L. ed. 148. As there is no

one corporate mind of the legislature, there is in reality

no single motive. Motives vary from one individual

member of the legislature to another. Each member is

required to ‘be bound by Oath or Affirmation to support

this Constitution.’ Constitution of the United States,

Article VI, Clause 3. Courts must presume that legisla

tors respect and abide by their oaths of office and that

their motives are in support of the Constitution.

“ If, however, we could assume that the Act was passed

by the legislature with an evil and unconstitutional

intent, even that would not suffice. As executive officers

of the State, the members of the defendant Board are

likewise required to ‘be bound by Oath or Affirmation to

support this Constitution.’ Constitution of the United

States, Article VI, Clause 3. No court, without evidence,

can possibly presume that the members of the defendant

Board will violate their oaths of office.

“ It is possible for the Act to be applied so as to admit

qualified Negro pupils to nonsegregated schools. Upon

oral argument, counsel for both sides expressed their

understanding that the North Carolina Pupil Enrollment

Act was actually being so applied. We cannot say, in

advance of its application, that the Alabama Law will not

be properly and constitutionally administered.

18

“The burden assumed by the plaintiffs is not simply to

show that some one or more sections or parts of the

Alabama School Placement Law are unconstitutional,

but that said law is utterly void in toto. That is true

because the plaintiffs are not in position to show upon

what particular ground they were not permitted to attend

the schools of their choice.”

As to the motives of legislators in passing Acts and Reso

lutions, see the following:

ARIZONA v. CALIFORNIA, 283 U. S. 423, 455;

UNITED STATES v. DES MOINES NAV. & R. CO., 142

U. S. 510, 554;

ACHESON, TOPEKA & S. FE R. CO. v. MATTHEWS,

174 U. S. 96,102;

CALDER v. MICHIGAN, 218 U. S. 591, 598;

WEBER v. FREED, 239 U. S. 325, 330;

TENNEY v. BRANDHOVE, 341 U. S. 367;

RAST v. VAN DEMAN & L. CO., 240 U. S. 342, 357, 366;

HELVERING v. GRIFFITHS, 318 U. S. 371;

DANIEL v. FAMILY SECURITY L. INS. CO., 336 U. S.

220;

BAILEY v. RICHARDSON, 182 F. 2d 46, 62, affirmed

341 U. S. 918;

BUTLER v. THOMPSON, 97 F. Supp. 17, affirmed 341

U. S. 937;

PETERSON v. PARSONS, 73 F. Supp. 840;

DUKE POWER CO. v. GREENWOOD COUNTY, 91 F.

2d 665;

STEPHENSON v. BINFORD, 287 U. S. 241;

19

CONNOR v. BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF LOGAN

COUNTY, OHIO, 12 F. 2d 789, 795;

LOVETT v. UNITED STATES, 66 F. Supp. 142, 145.

As we have pointed out above, the District Court for the

Middle District in the case of BLUE v. DURHAM PUBLIC

SCHOOL DISTRICT thoroughly explored and considered the

relationship between the State Board of Education, State

Superintendent of Public Instruction and the County and

City Boards of Education, and as a result, sustained the

State’s Motion to Dismiss. We think we have further shown

the Court above that since the Blue case the relationship

between these units has been of such a nature that the General

Assembly has decentralized the System more and more and

has granted more and larger local autonomy and greater

powers to the County and City Boards of Education. In other

words, if a Motion to Dismiss should have been sustained in

the Blue case, there is all the more reason to sustain such

Motion now or to refuse to have such Defendants made parties

Defendants where such action has not already been taken.

This leads us to the conclusion, which we think is sound,

that neither the State Board nor the State Superintendent are

indispensable or necessary parties defendant to this ac

tion, nor is their joinder authorized by the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure or the Federal Statutes as interpreted by

the Federal Courts. In the case of McRANIE v. Palmer, 2 F.

R. D. 479, the Court classifies the different types of parties

under the Federal Practice, saying:

“ In the federal courts, parties to actions are divided into

different classes: (1) formal, (2) proper, (3) necessary,

and (4) indispensable. Moore’s Federal Practice, section

19.01.***

***

“The leading case which states the rule with respect to

indispensable parties is Shields et al. v. Barrow, 17 How.

130, 139, 15 L. ed. 158. The court there said, in dealing

with parties not before the court: '*** if their interests

20

are separable from those of the parties before the court,

so that the court can proceed to a decree, and do complete

and final justice, without affecting other persons not

before the court, the latter are not indispensable parties’.

See Ducker v. Butler et al., 70 App. D. C. 103, 104 F. 2d

236, 238; State of Washington v. United States, et al., 9

Cir., 87 F. 2d 421; and Wyoga Gas & Oil Corp. v. Schrack

et al., D. C. 27 F. Supp. 35. In Niles-Bement-Pond Co. v.

Iron Moulders’ Union, 254 U. S. 77, 80, 41 S. Ct. 39, 41, 65

L. ed. 145, the court said: ‘There is no prescribed formula

for determining in every case whether a person or corp

oration is an indispensable party or not.’ ”

In KUHN v. YELLOW TRANSIT FREIGHT LINES, 12

F. R. D. 252, on the question of parties ,the Court said:

“Decision on the applicability of this rule must turn on

the character of the parties sought to be joined. The rule

declares those parties whose presence is ‘required’ for

granting of complete relief on the counterclaim shall be

brought in. What meaning shall be given to the word

required’? Use of that particular word indicates its use

as synonymous with ‘indispensable’ parties. The three

general classes of parties to any action were defined in

Division 525, Order of Ry. Conductors of America v. Gor

man, 8th Cir., 133 F. 2d 273, 276: ‘Proper’ or ‘formal’

parties include those who are not interested in the con

troversy between the immediate litigants but have an

interest in the subject matter which may be conveniently

settled in the suit. ‘Necessary parties’ are those who have

an interest in the subject matter and who are within the

jurisdiction of the court, but who are not so indispensable

to the relief asked as would prevent the court from enter

ing a decree in their absence. ‘Indispensable’ parties are

those whose interests are so bound up in the subject

matter of litigation and the relief sought that the court

cannot proceed without them, or proceed to a final judg

ment without affecting their interests.’

“We conclude that ‘indispensable’ parties are the only

class whose presence is ‘required’ in order to grant

complete relief in this case. In the Gorman case the Court

states in no uncertain language that an adjudication can

be reached without the presence of mere ‘necessary’

parties, and certainly without ‘proper’ parties.”

In SAVOIA FILMS A. I. v. VANGUARD FILMS, 10 F. R.

21

D. 64, there was before the Court a suit between two film

corporations. The plaintiff alleged that David 0. Selznick

should be a party defendant because Vanguard Films made

the agreement in question on behalf of itself and on behalf of

Selznick. In sustaining the motion to drop Selznick as a party

defendant, the Court said:

“Defendant Selznick is not an indispensable party to this

action. He was not a party to the agreement and any

determination of the rights of plaintiff and defendant

Vanguard Films, Inc., under the contract will not affect

the legal rights of Selznick. An indispensable party must

be distinguished from a necessary party, who is a person

having such an interest in the controversy that he ought

to be made a party in order to finally determine the entire

controversy, but whose interest is separable. Shields v.

Barrow, 1854, 17 How. 130, 58 U. S. 130, 139. At best the

defendants’ interests are joint and several, and in that

event the joinder of all the parties as indispensable is not

required, 3 Moore’s Federal Practice, 2d Ed., p. 2164. In

the opinion of this Court, defendant David O. Selznick

is not an indispensable party to this action but only a

necessary party, and the action may be continued without

him.”

The term ‘joint interest’ as used in 19 (a) of F. R. C. P. has

been explained in the case of COUNTY OF PLATTE v. NEW

AMSTERDAM CASUALTY CO. et als., 6 F. R. D. 475, where

the Court said:

“The term ‘joint interest’, as used in Rule 19 (a), refers

to parties designated as necessary or indispensable under

the former practice, and means an interest which must

be directly affected by the adjudication in the case. United

States v. Washington Institute of Technology, 3 Cir., 138

F. 2d 25; Currier v. Currier. D. C. N. Y., 1 F. R. D. 683;

Samuel Goldwyn, Inc., v. United Artists Corporation, 3

Cir., 113 F. 2d 703.

“Subdivision (a) of Rule 19 deals with the necessary

joinder of indispensable parties and is declaratory of the

law as it previously existed with respect to who are in

dispensable parties. Under such previously existing law,

the indispensability of parties depended upon state law.

Young v. Garrett, 8 Cir., 149 F. 2d 223.

22

“The court will therefore look to the law of Nebraska in

determining whether W. L. Boettcher, or his representa

tives, are necessary or indispensable parties to the instant

actions.”

On this question, see also the following:

HOLLIDAY v. LONG MANUFACTURING CO., 18 F. R.

D. 45;

PHOTOMETRIC PRODUCTS CORPORATION v. RAD-

TKE, 17 F. R. D. 103;

FITZGERALD v. JANDREAU, 16 F. R. D. 578;

CONDUCTORS OF AMERICA v. GORMAN, 133 F. 2d

273;

BAIRD v. PEOPLES BANK & TRUST CO., 120 F. 2d

1001;

COLORADO v. TOLL, 268 U. S. 228, 69 L. ed. 927;

UNITED STATES v. PETROSKY, 2 F. R. D. 422.

In view of the fact that the Supreme Court of North Caro

lina has already said in CONSTANTIAN v. ANSON COUNTY,

supra, that the portion of Article IX, Sec. 2, of the Constitu

tion, which attempts to separate the schools according to

races, is void, invalid and of no effect, and also in view of the

fact that the present school law has no reference whatsoever

to races and has no provision requiring segregated schools,

and when we consider further that enrollment and assignment

of pupils is not in the hands of State officers at all but has

been directly committed and vested in the local units by the

General Assembly, there could not possibly be any foundation

for legal liability as against the State officers and as to this

action they are not even eligible to be formal or proper

parties defendant much less necessary or indispensable parties

defendant. As said by the Court in MILLS v. LOWNDES, 26

F. Supp. 792:

“ In making an officer of the state a party defendant in a

suit to enjoin the enforcement of an act alleged to be

unconstitutional, it is plain that such officer must have

23

some connection with the enforcement of the act, or else

it is merely making him a party as a representative of the

state, and thereby attempting to make the state a party.”

Assuming for the sake of argument that the school system

in this State was a hierocratical, authoritarian organization

and there was a straight line of authority from the State

officers to the local units (we have shown that this is not

true) then in that event under the Federal decisions it

would not be necessary to make the State officials parties

defendant in these cases. This is true because of the nature of

the North Carolina School Statutes and because the relief

demanded by the plaintiffs can be effectively granted by

decree operating on the subordinate units without requiring

any action directly or indirectly on the part of the superiors,

State officers. It is very plain that under these statutes an

order or decree of this Court operating on the local units can

be made without fear of the possibility that the decree may be

rendered nugatory by any subsequent action on the part of

the State officials. This has been demonstrated in the Federal

Courts by many decisions. In COLORADO v. TOLL, 268 U. S.

228, 69 L. ed. 927, on this point the Court said:

“The object of the bill is to restrain an individual from

doing acts that it is alleged that he has no authority to

do, and that derogate from the quasi sovereign authority

of the state. There is no question that a bill in equity

is a proper remedy, and that it may be pursued against

the defendant without joining either his superior officers

or the United States. Missouri v. Holland, 252 U. S. 416,

431, 64 L. ed. 641, 646, 11 A. L. R. 984, 40 Sup. Ct. Rep.

382; Philadelphia Co. v. Stimson, 223 U. S. 605, 619, 620,

56 L .ed. 570, 576, 577, 32 Sup. Ct. Rep. 340.”

In WILLIAMS v. KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, et al., 104

F. Supp. 848, 854, suit was brought for an injunction and

declaratory judgment in that plaintiffs were denied admit

tance to the municipal swimming pool because of their color.

The swimming pool was operated by a Board of Park Commis

sioners which was an independent agency under the City

Charter, and in this action the plaintiffs saw fit to make

the Mayor of the City a party defendant. In ruling that the

24

Mayor of Kansas City was not a necessary or proper party,

the Court said:

“ It should be pointed out now that the Board of Park

Commissioners, as an independent agency under the

charter of Kansas City, Missouri, is not subject to control

or supervision of the Mayor of said City, or its City

Manager. The latter mentioned officials of the City are

brought into official contact with said Board only through

appointive power resident in the Mayor, and in regard to

fiscal matters controllable by the City Manager. Other

wise the Mayor and City Manager of the City have no

control over the administrative functions of such Board.

As a consequence thereof the defendant William Kemp,

as Mayor of Kansas City, Missouri, is not a necessary or

proper party in the instant action. He is not connected,

in the evidence or by operation of law, with the subject

matter thereof.”

In HYNES v. GRIMES PACKING COMPANY, 337 U. S.

86, 93 L. ed. 1231, the plaintiffs, a fish canning company,

brought an action against the Regional Director for Alaska

of the Fish and Wildlife Service to permanently enjoin the

exclusion of their fishermen from a fishing reservation. In

holding that the Secretary of the Interior did not have to be

joined as a party defendant, the Court said:

“ (a) At the outset the United States contends that the

Secretary of the Interior is an indispensable party who

must be joined as a party defendant in order to give the

District Court jurisdiction of this suit. In Williams v.

Fanning, 332 U. S. 490, 92 L. ed. 95, 68 S. Ct. 188, the test

as to whether a superior official can be dispensed with as

a party was stated to be whether ‘the decree which is

entered will effectively grant the relief desired by ex

pending itself on the subordinate official who is before

the court.’

“ Such is the precise situation here. Nothing is required

of the Secretary; he does not have to perform any act,

either directly or indirectly. Respondents merely seek an

injunction restraining petitioner from interfering with

their fishing. No affirmative action is required of petition

er, and if he and his subordinates cease their interference,

respondents have been accorded all the relief which they

25

seek. The issues of the instant suit can be settled by a

decree between these parties without having the Secre

tary of the Interior as a party to the litigation.”

In WILLIAMS v. FANNING, 332 U. S. 490, 92 L. ed. 95, it

was held that the Postmaster General did not have to be

joined as a party defendant in a suit against the local post

master to restrain the enforcement of a fraud order. See also:

Annotation in 158 A. L. R. 1126. See also: Text and Cases

Cited in Notes in BARRON & HOLTZOFF: F. P. P. p. 81, sec.

515 et seq.

Ill

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS HAVE NO LEGAL STATUS

TO ATTACK THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE

VARIOUS STATUTES WHICH COMPRISE THE SO-

CALLED “PEARSALL PLAN”.

It is well established as one of the elementary principles of

constitutional law that the constitutionality of a legislative

act is open to attack only by a person whose rights are affected

thereby. Such a person must show that the enforcement of the

law would not only be an infringement of his rights but that

he would be injuriously affected. The corollary to this rule is

that one who is not prejudiced by an enforcement of an act

of the legislature or one against whom no attempt has been

made to enforce the statute may not challenge its constitution

ality.

11 Am. Jur (Constitutional Law) p. 748, Sec. Il l ;

16 C. J. S. (Constitutional Law) p. 226, Sec. 76.

There has been no attempt to enforce the Local Option

Article in the State of North Carolina. There has been no

application for tuition expense grants made by the plaintiffs

or any other persons in the State of North Carolina. No colored

people or white people have invoked these statutes, and this

also includes the plaintiffs in this action. Since the Pupil

Assignment and Enrollment Statute has been declared to be

26

constitutional and since these other Articles of the School

Law have in no manner been applied to the situation of the

plaintiffs, they do not have sufficient legal status to attack the

constitutionality of these statutes.

We are aware of the fact that in Virginia and perhaps in

Florida placement or assignment acts have been declared to be

unconstitutional because certain other collateral statutes re

quired all schools to be closed if any integration took place

and cut off all public funds for public school purposes. Such

is not the situation in North Carolina, and, therefore, the

plaintiffs have no basis for seeking to tie all these statutes

together and having them all declared unconstitutional. The

legal authorities support our view that the plaintiffs have no

legal status to attack these statutes.

In UNITED PUBLIC WORKERS v. MITCHELL, 330 U. S.

75, 89; 91 L. ed. 754, 766, the Court said:

“As is well known the federal courts established pursuant

to Article III of the Constitution do not render advisory

opinions. For adjudication of constitutional issues ‘con

crete legal issues, presented in actual cases, not abstrac

tions,’ are requisite. This is as true of declaratory judg

ments as any other field. These appellants seem clearly

to seek advisory opinions upon broad claims of rights

protected by the First, Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Amend

ments to the Constitution. ***

“ ***The power of courts, and ultimately of this Court,

to pass upon the constitutionality of acts of Congress

arises only when the interests of litigants require the use

of this judicial authority for their protection against

actual interference. A hypothetical threat is not enough.

We can only speculate as to the kinds of political activity

the appellants desire to engage in or as to the contents

of their proposed public statements or the circumstances

of their publication. It would not accord with judicial

responsibility to adjudge, in a matter involving consti

tutionality, between the freedom of the individual and

the requirements of public order except when definite

rights appear upon the one side and definite prejudicial

interferences upon the other.”

27

In STEPHENSON v. BINFORD, 287 U. S. 251, 277; 77 L.

ed. 288, 301, the United States Supreme Court said:

“So far as appears no attempt yet has been made to

enforce the provision against any of these appellants,^and

until this is done they have no occasion to complain.”

In ALABAMA STATE FEDERATION OF LABOR v. Mc-

ADORY, 325 U. S. 450, 461; 89 L. ed. 1725, 1734, the Court

said:

“The requirements for a justiciable case or controversy

are no less strict in a declaratory judgment proceeding

than in any other type of suit. ***This Court is without

power to give advisory opinions. ***It has long been its

considered practice not to decide abstract, hypothetical

or contingent questions, ***or to decide any constitu

tional question in advance of the necessity for its decision,

***or to formulate a rule of constitutional law broader

than is required by the precise facts to which it is to be

applied, ***or to decide any constitutional question ex

cept with reference to the particular facts to which it is

to be applied.***”

In STANDARD STOCK FOOD CO. v. WRIGHT, 225 U. S.

540, 550; 56 L. ed. 1197, 1201, Mr. Chief Justice Hughes, on

this point, says:

“The case in this aspect falls within the established rule

that ‘one who would strike down a state statute as

violative of the Federal Constitution must bring himself

by proper averments and showing within the class as to

whom the act thus attacked is unconstitutional. He must

show that the alleged unconstitutional feature of the law

injures him, and so operates as to _deprive him of rights

protected by the Federal Constitution.” ’

This rule is so well established that we will not bother the

Court with further quotations but we do refer the Court to the

following cases:

BODE v. BARRETT, 344 U. S. 583; 97 L. ed. 567, 571;

WATSON v. BUCK, 313 U. S. 387, 402; 85 L. ed. 1416,

1424;

28

COLUMBUS & G. R. CO. v. MILLER, 283 U. S. 96, 99;

75 L. ed. 861, 865;

MASSACHUSETTS v. MELON, 262 U. S. 447, 484; 67 L.

ed. 1078, 1084;

DOREMUS v. BOARD OF EDUCATION, 342 U. S. 429,

434; 96 L. ed. 475, 480; 72 S. Ct. 394. See Anno. 50 L,

ed. 382;

PULLMAN CO. v. RICHARDSON, 261 U. S. 330; 67 L.

ed. 682;

PREMIER-PABST SALES CO. v. GROSSUP, 298 U. S.

226, 227; 80 L. ed. 1155, 1156;

DEAN OIL CO. v. AMERICAN OIL CO., 147 F. Supp.

414, 417;

MOORE ICE CREAM CO. v. ROSE, 289 U. S. 373, 383,

384;

LARSEN v. CITY OF COLORADO SPRINGS, 142 F.

Supp. 871, 873;

C. I. O. v. McADORY, 325 U. S. 472, 475, 89 L. ed. 1741;

TILESTON v. ULLMAN, 318 U. S. 44, 46, 87 L. ed. 603;

ASHWANDER v. TYA, 297 U. S. 288, 324, 80 L. ed. 688,

699;

UNITED STATES v. APPALACHIAN POWER CO., 311

U. S. 377, 423; 85 L. ed. 243, 261;

JEFFREY MANUFACTURING CO. v. BLAGG, 235 U.

S. 571, 576; 59 L. ed. 364, 368;

DAHNKE v. BONDURANT, 257 U. S. 282, 289; 66 L. ed.

239, 243.

29

IV

THE MOTION TO DISMISS FILED BY THESE APPEL

LEES SHOULD BE SUSTAINED BECAUSE THE