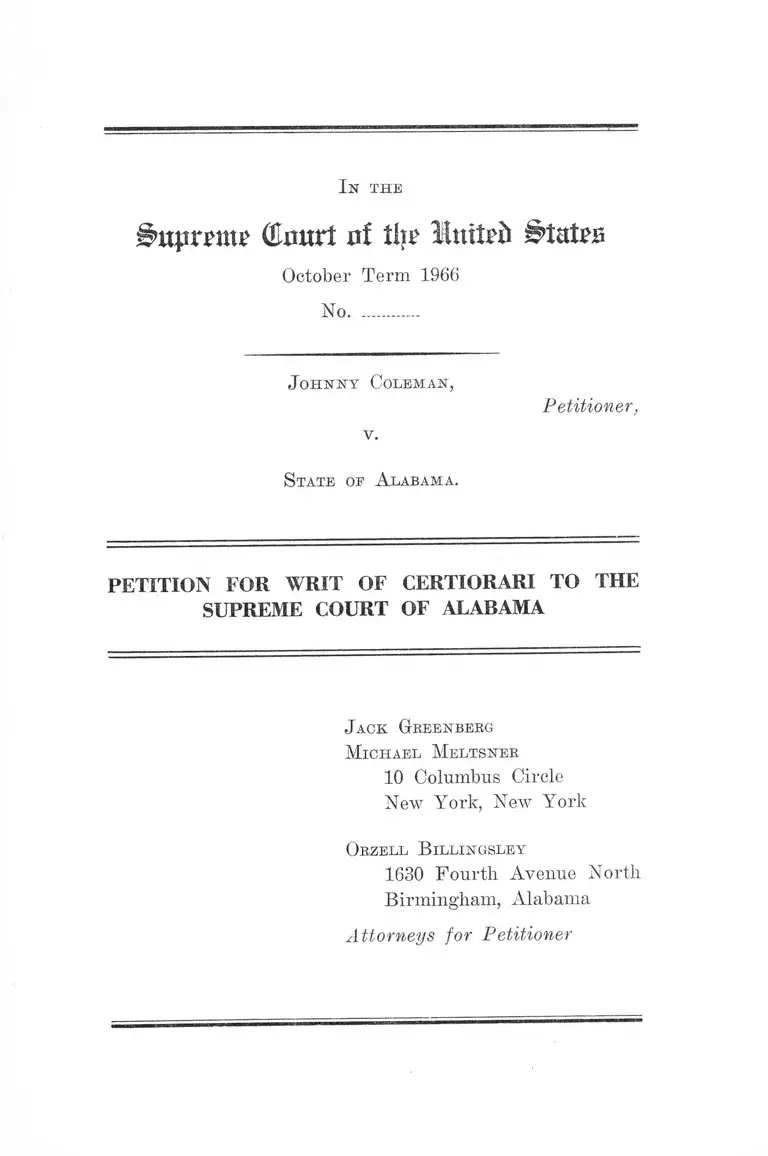

Coleman v. Alabama Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Coleman v. Alabama Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama, 1967. 261e29ed-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3079f0a-581b-4a7b-a0d5-37fd7afcea62/coleman-v-alabama-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-alabama. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Ihtprmp (Emtrt at tiu Hutted States

October Term 1966

No. ______

J o h n n y C o lem an ,

v.

Petitioner,

S tate oe A labam a .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

J ack G reenberg

M ich ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

O rzell B illin g sley

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions Below ...........................................- 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ................................... ... ...... .......... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement ........................................................................... 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below ............................................................................... 13

Reasons for Granting the Writ ....................................... 16

I. Petitioner Has Established a Prima Facie Case

of Racial Discrimination in Selection of Jurors

Which the State Has Failed to Rebut .............. 20

A. The Decided Racial Variation on the Jury

Roll Makes Out a Prima Facie Case ........... 20

B. Vague and Subjective Standards for Selec

tion of Jurors Establish a Prima Facie Case

of Discrimination ............................................... 25

C. The State Failed to Offer a Satisfactory

Explanation for the Gross Disparity Be

tween Negro and White Jury Service ........... 28

II. Appellant Was Deprived of Due Process of Law

and Equal Protection of the Laws in Violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment Because Women

Were Totally Excluded From the Juries Which

Indicted, Convicted and Sentenced H im .............. 33

C onclusion ........................................... ................................ -.......... 36

PAGE

IX

A ppendix

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama.............. la

Denial of Rehearing ............................. 7a

Opinion of the Circuit Court of Greene County....... 8a

Judgment of United States District Court .............. 12a

Appendix of Statutes Involved .......... 15a

Appendix on Computation ......................................... 26a

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Allen v. State, 137 S.E.2d 711, 110 Ga. App. 56 (1964) 35

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 (1964) ........... 22

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964) .......................... 27

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946) ............ 35

Board of Supervisors v. Ludley, 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir.

1958) .................................................. 27

Bostick v. South Carolina, 18 L.Ed. 2d 223 (1967) ....18, 25

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953) ............................. 24

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952) .... 26

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) .... ......................22, 32

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445 (1927) ............. 26

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964) ........... ........ 3,15

John Coleman v. State of Alabama, 164 So. 2d 708 .....3,13

Coleman, et al. v. Barton, et al. (No. 63-4, N.D. Ala.).— 3, 7

Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University of

N. Y., reported with Superior Films, Inc. v. Depart

ment of Education, 346 U.S. 587 (1954) .................. 26

PAGE

I ll

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala.) aff’d per

curiam, 336 U.S. 933 (1949) ....................................... . 27

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963) ......... 27

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) .....-............ 22

Fikes v. Alabama, 263 Ala. 89, 81 S.2d 303 (1955) re

versed on other grounds 352 U.S. 191 ...................... 5

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 339 (1966) .......... 27

Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1941) .............. 24

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663

(1966) ...................... ....................................................... 34

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937) ........................ 26

Howard v. State,------A la.------- , 178 So, 2d 520 (1967) 15

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961) ..............................33, 34

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. en bane 1966)

16,19, 24, 26, 35

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......26,27

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966) 21

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958) .................... 15

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) .............18,29,32

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939) .............. 29,30,32

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir.

en banc 1966) ......................................... .................... 16, 24

Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 56 (5th Cir. 1966) .............. 21

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 376 U.S. 339 (1964) .... 15

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ...........16, 22, 24, 26, 35

Speller v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1952) ............................ 21

PAGE

IV

South. Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) ..... 27

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 (1958) .............. 27

Strauder v. "West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ......... . 21

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) _.......................5,19

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946) ..... 24

United States v. Atkins, 323 F.2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 27

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U.S. 81

(1921) ............................................................................. 26

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965) ....... 26

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1962) ....................................................................... 21

White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ....33, 34

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) .............18,21,23,25,

26, 28, 32

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) .................... 15

Williams v. South Carolina, 237 F. Supp. 360 (E.D.

S.C. 1965) ..................................................................... 33

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948) ...................... 26

Statutes Involved:

Alabama Act No. 284 (Special Session, 1966) ..............2, 33

Alabama Act No. 285 (Special Session, 1966) ...............2,33

Ala. Code Tit. 15, §§382 et seq. (1958 Recompiled) ....... 15

Title 30 §20, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) ....... 2, 5

Title 30 §21, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) .......2, 5,

10,12,14,15, 25, 26,

27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34

Title 30 §24, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) .....2, 5, 6

Title 30 §30, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) ..... 2

Title 30 §38, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) ....... 2,8

Title 30 §72, Code of Alabama (1958 Recompiled) ....... 2

PAGE

V

Arizona Rev. Stat. Ann. (1956) §21-201.......................... 17

Arkansas Stat. Ann. (1962): §39-101.. 17

39-206 ....................... 17

39-208 .................... 17

Connecticut Gen. Stat. Ann. (Supp. 1965) §51-217...... 17

Florida Stat. Ann. (1961) Tit. 5 §40.01........................... 17

Georgia Code Ann. (1965): §59-106 ............................... 17

Illinois Ann. Stat. (Smith-Hurd Supp. 1966) Tit. 78

§2 ....................................................................................- 17

Iowa Code Ann. (1950) §601.1 .......... ........ ..... .............. 17

Kansas Stat. Ann. (1964) §43-102 ................ ..... ........... 17

Louisiana Rev. Stat. Ann. (1950) §13-3041 ................... 17

Maine Rev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 14 §1254 (Supp. 1965) ....... 17

Maryland Ann. Code Art. 51 (Supp. 1966) §9 ......... 17

Michigan Stat. Ann. (Supp. 1965) §27A.1202 .............. 17

Miss. Code Ann. 1942 (Recompiled Vol. 1958) §1762 .... 33

Missouri Ann. Stat. (Supp. 1966) §494.010 .................. 17

Nebraska Rev. Stat. (1964) §25-1601 ........................... 17

New York Judic. Law (Supp. 1966) §504(5) ........... 18

North Carolina Gen. Stat. (1953) §9-1 ............ ............. 18

Oklahoma Stat. Ann. Tit. 38 (Supp, 1966) §28 ............ 18

South Carolina Code Ann. (1962) §38-52 ........... ...... 18, 33

Texas Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. (1964) §2133 ...................... 18

West Virginia Code Ann. (1966) §52-1-4 ...................... 18

Wisconsin Stat. Ann. (1957) §255.01(5) ........................ 18

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ............................................................ 2

42 U.S.C. §1971 (c) ............ ...................... ........................ 30

42 U.S.C. §§1973 et seq............................... -......... ..... -.30, 32

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............. ...... ................. ......... ..... .......... 3

PAGE

VI

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Bureau of Census, 18th Decennial Census of the United

States (1960) ....................................................... ........ 4,5

Civil Rights Bill of 1966 (reintroduced as the Civil

Rights Bill of 1967) .................................................... 16

“ Civil Rights, 1966” Hearings before Subcommittee

No. 5 Comm, on Judiciary, House of Representa

tives, 89th Cong. 2nd Sess........................................... 18

“ Civil Rights” United States Civil Rights Commission

report for 1963, p. 32 .................................................. 6

Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, U.S.

Census of Population: 1960, Vol. I, pt. 2 (Alabama) 30

Finklestein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory to Jury Discrimination Case, 80 Harv. L.

Rev. 338 (1966) ............................................................ 23

Moroney, Facts from Figures (3rd and revised edition,

Baltimore, Md., 1956, Penguin Books) .................... 23

In t h e

Qkmrt of % HmM Btu&s

October Term 1966

No.............

J o h n n y C olem an ,

v.

Petitioner,

S tate of A labam a .

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioner, Johnny Coleman, prays that a writ of cer

tiorari issue to review the judgment of the Supreme Court

of Alabama entered in the above-entitled case on Feb

ruary 9, 1967, rehearing of which was denied March 9,

1967.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama is re

ported at ------ - Ala. —-—, 195 So.2d 800 (1967) and is set

forth in the appendix, infra, p. la. The unreported opin

ion of the circuit court of Greene County is set forth

in the appendix, infra, p. 8a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered February 9, 1967 (R. 185-93). Application for

rehearing was denied March 9, infra, p. 7a (R. 194-96).

On April 10, 1967, Mr. Justice Black stayed execution of

the death sentence pending disposition of this petition.

2

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and as

serting here deprivation of rights secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner, a Negro sentenced to death, is

denied due process of law and equal protection of the laws

when indicted, tried, convicted, and sentenced by juries of

a county where:

(1) approximately 80 percent of the population is Negro;

(2) Negroes rarely, if ever, serve on grand or petit

juries;

(3) jurors are selected by means of good character

tests; and

(4) the state did not offer a satisfactory explanation of

the gross disparity in Negro and white representa

tion on the jury rolls. 2

2. Whether petitioner is denied due process of law and

equal protection of the laws when indicted, tried, con

victed, and sentenced by juries chosen pursuant to statu

tory exclusion of females from service.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Due Process and Equal Protec

tion Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

This case also involves Title 30, §§20, 21, 24, 30, 38, and

72 of the Code of Alabama (1958 recompiled) and Ala

bama Acts Nos. 284, 285 (Special Session, 1966) which are

set forth in the appendix infra, pp. 15a-25a.

Statement

A. History of Litigation

This case is here for the second time. Johnny Coleman

a Negro, was indicted March 22, 1962 and convicted April 4,

1962 of murder by juries of Greene County, Alabama and

sentenced to death.1 2 The Supreme Court of Alabama af

firmed, 276 Ala. 513, 164 So.2d 704 (1963), but this Court

unanimously reversed and remanded for an evidentiary

hearing, holding: “Petitioner was not permitted to offer

evidence to support his claim” of racial discrimination in

selection of the grand and petit juries, Coleman v. Alabama,

377 U.S. 129, 133 (May 4, 1964).

The Supreme Court of Alabama remanded the case to

the trial court on May 28, 1964, “ so that evidence may be

taken” (164 So.2d at 708). At a hearing held April 27,

1965 before the circuit court of Greene County, the parties

stipulated that the transcript of trial in the case Coleman

et al. v. Barton, et al. (No. 63-4, N.D. Ala.), would con

stitute part of the record. This case, in which appellant

Coleman was one of six Negro plaintiffs, was a civil action

brought January 3, 1963 in a United States district court

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1983 seeking to eliminate racial

discrimination from the grand and petit juries of Greene

County. The district court found that plaintiffs were en

titled to declaratory relief and issued a judgment2 provid

1 “ There were no witnesses to the killing and the evidence of guilt

was circumstantial” Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129, 130 (1964).

2 The judgment, dated June 11, 1964, is set forth in the Appendix,

infra pp. 12a-14a and provides that:

(a) the jury commission is under a statutory duty to see that

the name of every person possessing- the qualifications to serve is

placed on jury rolls and in the jury box;

(b) the clerk o f the commission must visit each precinct in the

county at least once a year;

4

ing for reorganization of the county jury system on a con

stitutional basis.8 In addition, the circuit court considered

testimony from the prosecuting attorney at Coleman’s trial

and, despite a claim of attorney-client privilege, the white

attorney who represented Coleman at his arraignment and

trial. Coleman also took the stand to deny certain testi

mony of his former lawyer.

The court denied Coleman’s claim that juries of the

county which indicted and tried him were unconstitu

tionally selected infra, pp. 8a-lla. On February 9, 1967,

the Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed on the ground

that there was no conflict between the evidence and the

Fourteenth Amendment: the “figures would tend to indi

cate a disparity and in fact do indicate a disparity” but

it “can be explained by a number of other factors” (E. 190).

However, the only factor mentioned by the court was that

qualified Negroes migrated from the county. Application

for rehearing was denied March 9, 1967 (R. 196).

B. Population Figures

Greene County is overwhelmingly Negro in population.

Census figures compiled by the Bureau of Census in the

18th Decennial Census of the United States (1960) were 3

(e) the commissioners are under duty to familiarize themselves

with the qualifications of eligible jurors;

(d) no person otherwise qualified may be excluded from jury

service because of his race;

(e) the commission could not “ pursue a course of conduct” which

operated to discriminate and could not accept symbolic or token

representation of Negroes;

( f ) proportional limitations as to race are forbidden;

(g) the jury roll and box as presently constituted should be ex

amined for compliance with constitutional standards.

3 The district judge denied a prayer for injunctive relief against county

jury commissioners on the ground that Coleman’s criminal case was

awaiting retrial of the jury issue in the courts of Alabama, making it

“unseemly” in the court’s view to decree injunctive relief.

5

introduced in evidence (R. 188).4 They show that approxi

mately 8 out of every 10 males in the county over 21 are

Negro:

N W

Total population 13,600 11,504 (85%) 2,546 (15%)

Total males over 21— 3,022 2,247 (78%) 775 (22%)

C. Compilation of the Jury Roll and the Jury Box

Alabama law requires that the three jury commissioners

place on the jury roll “ the names of all male citizens of

the county” over 21 “who, are generally reputed to be

honest and intelligent men and are esteemed in the com

munity for their integrity, good character and sound judg

ment.” Habitual drunkards and those afflicted with per

manent disease or physical weakness are excluded. Literacy

is only required of those who do not own freeholds or

households, Ala. Code, Tit. 30 §§20, 21 (1958 Recompiled).5 6

Although the statutes aim at an exhaustive jury roll (Ala.

Code Tit. 30, §24 (1958 Recompiled)), the practice of the

commissioners is to place only a small proportion of the

total number of male citizens over 21 on the rolls.*

The jury roll is reworked annually in August of each

year (R. 89). Jury commissioners testified that there are

approximately 12 precincts or beats in Greene County

4 United States Census of Population, General Population Character

istics, PC (1) 2B Ala. p. 2-81 (1960).

6 One of the three commissioners was under the impression that only

qualified voters were qualified for jury service (R. 74) but both the

Ala. Code Tit. 30 §21 and testimony of other officials refute this belief.

6 The Supreme Court of Alabama has held that failure to include

every qualified person on the roll is not a ground to quash an indictment

or venire. See Fikes v. Alabama, 263 Ala. 89, 81 S.2d 303 (1955) re

versed on other grounds 352 U.S. 191; Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202,

207 N. 3 (1965).

6

from which qualified persons could be chosen for the roll

but the precincts were visited only sporadically despite

the requirement of Ala. Code Tit. 30, §24 (1958 Recompiled)

that it be done every year (R. 72-74, 81, 84, 85, 145). To

compile the jury roll, primary reliance was placed on

telephone directories, voter lists,7 and consultation with

officials, such as the sheriff, tax assessor and tax col

lector. After complaints from Negro leaders (R. 145, 146)

three Negroes in the county were asked to supply names

for the first time when the roll was reworked in August,

1962 (R. 85, 89, 90, 97, 98, 67, 70, 71). Coleman was in

dicted March 22, 1962 and convicted April 4, 1962 and

his grand and petit jury were chosen from the 1961 jury

roll, prepared in August 1961, prior to use of the three

Negro “key men” (R. 84-86, 89, 90).

D. Jury Box and Rolls

Both grand and petit jury venires are drawn from a jury

box by lot. All the names on the jury roll are placed in

this box and the present jury roll and jury box contain

approximately 375 names, a number which has been fairly

constant during the past ten years. Jury commissioner

Durrick was unable to estimate the number of Negroes

on the roll prior to 1962 but it was “a limited number”

(R. 86, 87). After the 1962 revision, he estimated the

Negro proportion to be “in the neighborhood of ten per

cent” (R. 90). After Durrick, who knew most of the Negroes

on the jury rolls, examined the rolls for the years 1961,

1962, and 1963 he stated that the largest number of Ne

7 The record does not reflect the number of Negro and white registered

voters but according to “ Civil Eights,” United States Civil Eights Com

mission Report for 1963 (p. 32) only 6.4% o f eligible Negroes were

registered while more than 100% o f the eligible whites were registered

in Greene County.

7

groes that he was able to identify on any one jury roll

was 28 (from a total of 377) for the 1963 jury roll (R. 89,

90, 141). The number for the 1961 roll from which Cole

man’s juries were chosen, was 16 (of 354) (R. 141). The

increase in the total number of persons on the roll between

1961 and 1963 reflects inclusion of Negroes subsequent to

the complaints of Negro leaders (R. 90, 91).

Durrick’s response with respect to the roll prepared in

1962 is disputed. The typed transcript of trial in Coleman

v. Barton, supra, repeats “ sixty-two” after the year 1962s

(R. 141) but Durrick testified that the 1963 roll contained

the largest number of Negroes (R. 89-91). Judge Grooms,

who heard the evidence, found that Durrick testified 26

(of 374) Negroes were on the 1962 roll, and that no more

than 10% of any roll was Negro even “allowing for those

not identified.” It seems likely, therefore, that “ sixty-two”

is a repetition of the year 1962 by the witness. The Su

preme Court of Alabama did not dispute the finding that

no more than 10% of the roll was Negro or testimony that

there were more Negroes on the roll in 1963 than 1962,

but, nevertheless, read the transcript to mean that the

commissioner had testified to 62 Negro names for 1962

(R. 188).8 9

8 The typed transcript shows the following interrogation of commis

sioner Durrick (R. 141) :

Q. Would you indicate for each of those years how many Negroes

you could identify are on those jury rolls? A. In 1961, Roll Number

45, I picked out sixteen. Roll Number 46, 1962, sixty-two. Roll

Number 47, 1963, twenty-eight.

Q. Did you, for each of those years, indicate the total number of

persons on the jury roll? A. 1961 there was three hundred fifty-

three; 1962 there was three hundred seventy-four and 1963, three

hundred seventy-seven.

9 Petitioner called this inconsistency to the attention of the Supreme

Court of Alabama in his application for rehearing. It was also urged

that under the rules of that court it was bound to accept the facts as

8

E. Grand Jury Venires and Panels

Grand jury venires are drawn from the general jury

roll and box and the circuit judge draws the panel of

18 from the venire by lot, Ala. Code Tit. 30, §38 (1958

Recompiled). The Supreme Court of Alabama found that

“generally 8 to 10” Negroes served on the grand jury

venires but the record only reveals the jury commission

clerk’s testimony that she had observed about eight to ten

(R. 153, 154, 189) Negroes on a grand jury venire of 50

to 60 (R. 20). A number of grand jury foremen testified

that during the previous ten years Negroes had always

served on the grand jury venires, but they put the maxi

mum number at between two and four (R. 21, 50, 54, 56).

Aside from one occasion in 1963 (after Coleman had

been indicted and convicted) when two to four Negroes

served on a grand jury panel, no Negroes had actually

served on the panel of 18 (R. 21, 38, 39, 44, 45, 48, 49, 53,

54, 56, 58, 65, 176).10 On the other hand many whites testi

fied who had each served repeatedly on the grand jury

stated in petitioner’s brief, because the state had failed to challenge

petitioner’s interpretation of the evidence for the roll prepared in 1962.

The State had declined to file a brief in the Supreme Court of Ala

bama which amounts to a concession of accuracy under Rule 9 of the

rules of the Supreme Court o f Alabama:

The statements made by appellant under the headings “ Statement of

the Case” and “ Statement of the Pacts” will be taken to be accurate

and sufficient for decision, unless the opposite party in his brief

shall make the necessary corrections or additions. (Ala. Code Tit. 7,

Sup. Court Rule 9)

In his brief before the Supreme Court of Alabama, Coleman stated that

the number of names identified for 1962 was not reflected in the transcript

but that the evidence showed that in no event was it greater than 28.

10 The clerk had seen 2 or 3 Negroes on a grand jury and one or two

Negroes on a petit jury, but this has not occurred very often (R. 154).

When asked if any Negroes served on the grand jury prior to 1962 she

answered “ I couldn’t tell you because I cannot keep dates completely

straight in my mind and I don’t want to say yes or no” (R. 154).

9

(E. 20, 21, 42, 53). A witness who was present in court

at the time testified that no Negro served on the panel

which indicted Coleman (E. 137), and the Deputy Solicitor,

who had been present at all criminal trials for eight years,

was questioned as follows (E. 176):

Q. Now Mr. Banks, do you know of any Negro

that ever served on a Grand jury in this county prior

to the time that this defendant was tried? A. I can’t

recall.

Q. You don’t recall any Negro that did? A. Not

offhand I can’t.

Q. Do you recall any Negroes who served on the

Grand Jury that indicted this defendant? A. I can’t

recall whether there was one or not.

F. Petit Jury Venires and Panels

Although the Supreme Court of Alabama found that

the venires of 50 to 60 “generally” include “6, 7 to 10

members of the Negro race,” the testimony is only that a

number up to eight to ten has been observed on a venire

(E. 19, 20, 189). It is uncontradicted that there were 2 to

4 Negroes on the venire of 56 from which petitioner’s

petit jury was struck (E. 175-77), and that few Negroes

have actually served on petit juries because they are struck

by attorneys’ use of peremptory challenges (E. 15, 16,

17, 101, 108, 154). The record as a whole suggests that

one Negro actually served on a criminal jury prior to

Coleman’s conviction (E. 102). For example, one of the

prosecuting attorneys testified (E. 176-77):

Q. Do you recall any Negro who served on a petit

jury on the trial of any case in this court prior to the

time that this defendant was tried? A. I can’t say

positively one did or did not.

1 0

Q. You don’t recall any, do you? A. I ’m just a

little hazey (sic). I’m trying to think—yes.

Q. Which one was that? A. I can not recall the

case.

Q. You mean actually served on a petit jury in this

county? A. Yes. To the best of my recollection, it

was a criminal case.

Q. When was that? A. I ’m not certain, but to the

best of my judgment, it was a criminal case that I

remember prior to. . . .

Q. Prior to the time this defendant was tried?

A. The best of my recollection it was.

Q. Can you give us the name of that Negro? A. I

can’t do it.

Q. Can you give us the name of the defendant who

was tried at that time? A. No.

Q. Can you give us the name of the attorney who

tried the case of the defendant at that time? A. I

don’t know whether it was Mr. Hall or not.

Q. Mr. who? A. Mr. David Hall. It might have

been him. I ’m not positive. I can’t say for sure.

Q. How long have you been practicing in this county?

A. Seventeen years.

Q. And you have been present during the trial of

all criminal cases, have you not? A. No, the last

eight years I have.

G. Relative Qualifications of Negroes and Whites

The record contains general “opinion” evidence regard

ing the relative qualifications of Negroes and whites for

jury service. The circuit judge thought, for example, that

only twenty per cent of the Negro community was quali

fied under §21 (E. 24). A banker found it a “hard ques

tion” but testified a “good number” more whites than Ne

11

groes were generally reputed to be honest, intelligent men,

esteemed in their community for their good character and

sound judgment (E. 40, 41). On the other hand several

Negro witnesses, including ministers, and property owners,

testified to long-term residence in the county, and to

knowledge of Negroes who met the statutory qualifications

who had not been called to serve as jurors. One of the

witnesses, Eev. Branch, pastor of two churches and a

school teacher, who had lived in the county all his life,

testified that no one had ever asked him to supply any

names of qualified Negro residents but that if asked he

could supply at least 1,500 names (E. 116, 118-20, 123-24,

129, 134-39).

The circuit judge also testified generally that of Negroes

“who receive an education . . . practically a hundred per

cent” left the county in search of better economic oppor

tunity (E. 24) while a Negro minister testified that quite

a few migrated to the north but that in his opinion the

more intelligent remain and “try to make it a good home

to stay” (E. 120). The Supreme Court of Alabama stated

in its opinion that “ . . . many of the Negroes who would

otherwise be eligible are moving away from the county

because of the lack of economic opportunity existing in

Greene County for them and other young people. The

members of the white and Negro races who would be a

benefit to this community and whose loss is felt in the

country leave and hence leave the community poorer for

their loss” (E. 190-91).

The only specific evidence offered to explain the variance

between the Negro proportion of the population and the

Negro proportion of the jury roll concerned the crime rate

and high school graduation.

The clerk of the jury commission testified that there

were 325 felonies committed by Negroes in the county in

12

the last 10 years and 12 committed by whites (R. 151).

Some of these were persons convicted more than once and

her statistics were not broken down to show recidivism, age,

sex or county residence of the offender (R. 151). The

Supreme Court of Alabama expressly refused to consider

crime statistics probative of the lack of qualified Negroes

because of the high Negro proportion of the population

(R. 190).

The county superintendent of education testified that

he had examined the graduation records of Negro and

white public school students (R. 155). He described the

number of students who had enrolled and subsequently

graduated between 1937 and 1952 (R. 156). In 1937, 63

whites registered and twelve years later 36 graduated

(R. 157). In 1947-1948 there were 50 white first graders of

whom twelve years later 29 graduated high school (R. 158).

In 1937-1938, 763 Negroes entered the first grade. Twelve

years later 81 graduated. In the year 1947-1948, 874

Negro children entered the first grade. Twelve years later

119 graduated (R. 158, 159). The statistics were not

broken down on the basis of sex. Nor did they reveal the

number of children who had left the county and gone to

school in another jurisdiction (R. 160, 161).

The statistics did not show the number of grades com

pleted by students who had not graduated although the

superintendent stated that whether or not a person who

dropped out of school could read English (required only

of non-property owners by Ala. Code Tit. 30 §21) depended

on the point at which he dropped out. He also testified

that children who dropped out of the 10th grade would be

able to read English; that no particular level of education

makes a man esteemed in the community for his integrity,

good character and sound judgment or is proof against

his being a drunkard or afflicted with a physical weakness;

13

and that a student who did not graduate could be a house

holder or freeholder and thus eligible for jury service even

if illiterate (E. 161-63). The record establishes that there

are an “unusual” number of Negro property owners in

Greene County (E. 35).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

In 1964, this Court reversed the judgment of the Supreme

Court in Alabama, and ordered a hearing of petitioner’s

claims, initially made by motion and amended motion for

new trial, that “ Negroes qualified for jury service in Greene

County, Alabama are arbitrarily, systematically and inten

tionally excluded from jury duty in violation of . . . the

Fourteenth Amendment.. ” (377 U.S. 129; E. (C) — (E )).

On remand, Coleman also filed in the trial court a motion

for discharge seeking release from custody on the grounds

that:

“1. The conviction of the defendant in this cause

was in violation of the laws and Constitution of Ala

bama and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States;

2. this Honorable Court failed to grant the de

fendant a speedy hearing in this cause (see John C.

Coleman v. State of Alabama, 164 So.2d 708).

3. the laws and statutes of Alabama pertaining to

the compiling, drawing and summoning of jurors are

vague and unconstitutional” (E. F).

On June 29, 1965, the circuit court of Greene County

held that, “there was no racial discrimination and that per

sons of the Negro race was not arbitrarily or systematically

14

excluded or intentionally excluded from jury roll and from

the jury box” (R. G-I), infra p. 10a.

Petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court of Alabama

claiming, that he had been denied due process and equal

protection of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States in

that:

(1) The state had failed to satisfactorily explain

the fact that at the time of his indictment Negroes had

never served on the grand juries of Greene County;

(2) The state had failed to satisfactorily explain

the fact that a decided variation existed between the

proportion of Negroes on the jury roll and the Negro

proportion of the population;

(3) Ala. Code Tit. 30 §21 on its face and as applied

granted excessive discretion to the jury commissioners

and was unconstitutionally vague and ambiguous.

The Supreme Court of Alabama rejected petitioner’s

Fourteenth Amendment claims of racial discrimination in

selection of jurymen holding that the disparity between

Negroes and whites on the jury rolls was explained because

“ . . . many of the Negro people remaining in the county are

not qualified under the statute for jury duty. It was not

shown that there was any discrimination against Ne

groes . . . as proscribed by our (sic) federal decisions”

(R. 191). Application for rehearing was denied (R. 196).

The unconstitutionality under the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the state’s exclusion of females from jury service

was first raised by petitioner in his brief in the Supreme

Court of Alabama. The court did not discuss this claim

or suggest any state law ground for declining to consider

it. Its opinion does state that “ The single issue in which

15

the Supreme Court of the United States reversed was the

trial court’s refusal to permit proofs of systematic exclu

sion of Negroes from the jury roll in Greene County . .

(R. 186).

The Supreme Court of Alabama had, however, discretion

to consider the claim of unconstitutional exclusion of fe

males because the question was properly raised in peti

tioner’s brief and also because the Supreme Court heard

this case “under the enlightened procedure of its automatic

appeal statute” which permits it in capital cases to consider

issues even if not raised,11 Coleman v. Alabama, 377 TJ.S.

129 (1964); Ala. Code Tit. 15, §§382 et seq. (1958 Recom

piled) ; Howard v. State, ------ Ala. ------ , 178 So.2d 520,

524-25 (1967). Jurisdiction over the claim of unconstitu

tional exclusion of females is premised, therefore, on the

doctrines that this Court may consider a federal question

(1) notwithstanding a state court’s discretionary refusal to

do so, Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375, 389 (1955) (dis

cretion to consider motion); Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham,

376 U.S. 339 (1964) (discretion to consider petition filed

on wrong size paper), or (2) unless a non-federal ground

which independently and adequately supports the judgment

is asserted. NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 455 (1958).

11 In his brief in support o f application for rehearing petitioner called

the attention o f the Supreme Court of Alabama to its failure to dispose

of the challenged exclusion of females in §21. The petition was denied

without opinion (R, 196).

16

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Introduction

The Public Importance of the Questions Presented

This capital case raises a claim of systematic racial dis

crimination in jnry selection which merits granting cer

tiorari. The decision below plainly conflicts with decisions

of this Conrt. Moreover, the case involves two issues of

transcendent importance to achieving nonracial jury se

lection.12

First. To what extent may a state delegate to jury selec

tion officials farreaching discretion to administer subjective

characterlogical standards which operate to exclude far

more Negroes than whites? The challenged statutory stan

dards “define” the framework within which jury selection

takes place and present, by their vagueness, a convenient

mask for discrimination. The long history of jury discrimi

nation makes clear that excessive discretion is the enemy

of nonracial selection: “It is this broad discretion located

in a no a-judicial office which provides the source of discrim

ination in the selection of juries.” Labat v. Bennett, 365

F.2d 698, 713 (5th Cir. en banc 1966) ; Smith v. Texas, 311

U.S. 128 (1940); Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34

(5th Cir. en banc 1966). The critical role of indefinite jury

qualifications is acknowledged by the proposed Civil Rights

Bill of 1966 (reintroduced as the Civil Rights Bill of 1967)

which provides affirmative procedures to comply with the

12 “ In a transitionary period where jury commissioners are moving, but

moving slowly, toward a nondiscriminatory system of selecting a cross-

section of the community, sophisticated methods of token inclusion o f

Negroes on venires have increased the defendant’s burden of proving a

prima facie case of systematic exclusion.” Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d

698, 712 (5th Cir. en banc 1966.)

17

Fourteenth Amendment by authorizing district courts to

require use of objective criteria for state jury selection.13

13 The following state statutes require jurors to be of good moral char

acter :

Alabama Code tit. 30 §21(1959) : “all male citizens of the county

who are generally reputed to be honest and intelligent men and are

esteemed in the community for their integrity, good character and

sound judgment. . . .”

Arizona Rev. Stat. Ann. (1956) §21-201: “ . . . sober and intelligent,

of sound mind and good moral character. . .

Arkansas Stat. Ann. (1962) : §39-101 Grand Juror: . . temperate

and o f good character. . . §39-206 Other Jurors: “ persons of good

character, o f approved integrity, sound judgment and reasonably in

formed. . . .” See also §39-208: same as 206 and applies to grand

jurors.

Connecticut Gen. Stat. Ann. (Supp. 1965) : §51-217: . . esteemed

in their community as persons o f good character, approved in

tegrity, sound judgment and fair education. . . .”

Florida Stat. Ann. (1961) Tit. 5 §40.01: “ law abiding citizens of

approved integrity, good character, sound judgment and intelli

gence. . . .”

Georgia Code Ann. (1965): §59-106: “ upright and intelligent citi

zens. . . .”

Illinois Ann. Stat. (Smith-Hurd Supp. 1966) Tit. 78 §2: “ of fair

character, o f approved integrity, of sound judgment, well-in

formed. . . .”

Iowa Code Ann. (1950) §601.1: “ of good moral character, sound

judgment. . . .”

Kansas Stat. Ann. (1964) §43-102: “ possessed of fan,' character

and approved integrity. . .

Louisiana Rev. Stat. Ann. (1950) §13-3041: “ of well known good

character and standing in the community. . . .”

Maine Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14 §1254 (Supp. 1965) : “o f good moral

character, o f approved integrity, o f sound judgment and well-in

formed. . . .”

Maryland Ann. Code Art. 51 (Supp. 1966) §9: “ with special refer

ence to the intelligence, sobriety and integrity of such persons.”

Michigan Stat. Ann. (Supp. 1965) §27A.1202: “ of good character,

o f approved integrity, o f sound judgment, well informed.”

Missouri Ann. Stat. (Supp. 1966) §494.010: “sober and intelligent,

o f good reputation” .

Nebraska Rev. Stat. (1964) §25-1601: “ intelligent, o f fair char

acter, of approved integrity, well informed” .

18

President Johnson emphasized the role in denying Four

teenth Amendment rights of “officials [who] make highly

subjective judgments of a jurors ‘integrity, good charac

ter and sound judgment’ ” when he proposed the 1966

Bill.14 Recently in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967) and Bostick v. South Carolina, 18 L,Ed.2d 223

(1967), this Court condemned statutes which injected race

into the source of jurymen because they provided an “op

portunity to discriminate.” The vague and subjective moral

standards challenged here provide a similar opportunity to

discriminate.

Second. The judgment below rests on the validity of the

state’s explanation of a gross disparity on the jury rolls

which, if unrebutted, establishes a case of racial discrimi

nation. This Court has never directly considered the proper

standards to be applied in appraising whether the state

has carried its burden once a prima facie case has been

established. The rule of proof set out in Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587 (1935) has been applied by this Court and

the lower courts for over thirty years to measure discrim

New York Judie. Law (Supp. 1966) §504(5) : “o f good character,

o f approved integrity, o f sound judgment” .

North Carolina Gen. Stat. (1953) §9-1: “ o f good moral character

and have sufficient intelligence to serve” .

Oklahoma Stat. Ann. tit. 38 (Supp. 1966) §28 “ o f sound mind and

discretion, of good moral character” .

South Carolina Code Ann. (1962) §38-52: “ o f good moral char

acter” .

Texas Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. (1964) §2133: “ of sound mind and

good moral character” .

West Virginia Code Ann. (1966) §52-1-4: “ of sound judgment,

o f good moral character” .

Wisconsin Stat. Ann. (1957) §255.01(5) : “ esteemed in their com

munities as of good character and sound judgment” .

14 “ Civil Rights, 1966” Hearings before Subcommittee No. 5 Comm, on

Judiciary, House of Representatives, 89th Cong. 2nd Sess., pp. 1050,

1056, 1057.

19

ination in jury selection. As a consequence of a small in

crease in Negro jury service from total exclusion to to

kenism, however, there are increasing numbers of cases

where attempts are made to “ justify” decidedly dispropor

tionate selection of Negroes and whites. In Swain v. Ala

bama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), for example, the Court failed to

find a prima facie case and, therefore, did not reach the

state’s attempted justification for a disparity in rates of

venereal disease, public assistance, and illegitimacy. In

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. en banc 1966),

the state unsuccessfully sought to excuse a failure to call

wage earners and laborers which resulted in a great under

representation of Negroes.

In this case the Supreme Court of Alabama accepted

the state’s “explanation” for the discrimination but failed

to articulate clearly the manner in which it reached this

result or the standard of proof applied. The question of

what constitutes sufficient explanation to overcome a prima

facie showing now assumes the same critical importance as

the question of what constitutes a prima facie showing.

Acceptance as rebuttal of the sort of inconclusive evidence

of Negro disqualification produced below seriously affects

the vitality of the prima facie rule.

20

I.

Petitioner Has Established a Prima Facie Case of

Racial Discrimination in Selection of Jurors Which the

State Has Failed to Rebut.

A. The Decided Racial Variation on the Jury

Roll Makes Out a Prima Facie Case

The gross disproportion between the Negro population

of Greene County and its representation on the county jury

roll establishes a prima facie case of discrimination which,

if not satisfactorily explained, requires that petitioner’s

conviction be set aside. The state acted on this assumption

as shown by its attempt to justify the disproportion by

crime and high school graduation statistics. And the Su

preme Court of Alabama rested its affirmance on the

ground that the disparity between Negroes and whites “can

be explained by a number of other factors” than race

(R. 190, 191). The United States district judge who heard

much of the testimony, which later served as the record

before the Alabama courts, found discrimination, entered

a declaratory judgment, and denied a prayer for injunctive

relief only because of the pendency of this case in the

state courts, infra, pp. 12a-14a.

The disparity on the jury rolls is simply too large to go

unexplained. Although 8 of every 10 males in the county

are Negro, at the most only 1 out of every 10 persons on

the 1963 jury roll was Negro. The 10 percent estimate

likely overstates Negro participation for a jury commis

sioner familiar with the Negroes of the county could only

identify 16 Negroes out of 354 persons on the 1961 roll

from which petitioner’s juries were selected. Thus, be

cause of the relatively few whites who reside in the county

21

approximately 1 of every 2 white males over 21 are listed

for jury service,15 16 while accepting the 10 percent estimate,

approximately 1 Negro male out of every 65 Negroes over

21 is on the jury roll.16 Whites serve as jurors repeatedly

while few, if any, Negroes serve at all.

A jury list which so distorts the racial composition of

the community “strongly points” to discrimination, Whitus

v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552 (1967). In Whitus Negro

participation in the jury franchise was far greater than

here (Negroes constituted 9.3% and 7.8% of the venires

and only 27% of the taxpayers) and the court found a

prima facie case. See also Speller v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443,

481 (1952) (variance between 38% Negro population and

7% on jury list must be explained); United States ex rel.

Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962) (Negroes 31%

of population and 2% of lists; prima facie case estab

lished) ; Scott v. Walker, 358 F.2d 56 (5th Cir. 1966) (Ne

groes 13% of population and 1% of lists; prima facie case

established).

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966)

is instructive because it concerns an Alabama county where

the Negro-white population ratio is similar to Greene’s.

The Macon County jury list contained 732 whites and 406

Negroes. Negroes constituted 35.7% of the names on the

list and 82% of the population, a far more favorable rep

resentation of Negroes than in Greene, but the court found

that the underrepresentation established racial discrimina

tion.

15 319 (90% of 354) whites on 1961 list of 775 whites over 21 in the

population.

16 35 (10% of 354) Negroes on the 1961 list of 2247 Negroes over 21

in the population.

22

The record also clearly shows that petitioner was in-

dieted prior to empanelling of the first grand jury on which

a Negro served, a circumstance which has always been con

sidered sufficient by itself to establish a prima facie case.17

This Court has consistently reversed convictions in cases

where there has not been actual Negro grand jury service

or where only a token number have served over the years

in counties with far smaller Negro populations than Greene

County, Alabama; Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584

(1958) (one Negro served in eighteen years); Arnold v.

North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 (1964) (one Negro served in

24 years). Cf. Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) (one

Negro on each of 21 consecutive juries over a six year

period); Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) (Negroes con

stituted 20% of population; 10% of poll taxpayers but

“very few” served on grand juries).

A scientific appraisal of the result confirms that there

is racial discrimination in Greene County jury selection.

17 Nine white men who had been grand jury foremen usually on two,

three or four occasions but in some cases even more often during the pre

vious ten years testified that (1) two to four Negroes appeared on the

grand jury venires of from 50 to 60; (2) with one exception, Negroes

never served on the panel of 18 grand jurors; (3) the exceptions men

tioned was the September, 1963 grand jury empanelled over a year after

Coleman’s indictment. The Deputy Solicitor of the Circuit and one o f the

attorneys who prosecuted Coleman, testified that he had been present for

all criminal trials during the last eight years, had a “ fairly wide” ac

quaintance with Negroes in the community, and could not recall any

Negro who had served on a grand jury of the county prior to Coleman’s

trial (R. 175, 176).

A witness, who was present in court at the time, testified that there

were no Negroes on the grand jury which indicted Coleman, March 22,

1962.

This testimony was not contradicted by the clerk of the jury commis

sion, who when asked if Negroes served on the grand jury prior to 1962

answered:

I couldn’t tell you because I cannot keep dates completely straight in

my mind and I don’t want to say yes or not (R. 154).

23

Use of the techniques to determine the mathematical prob

ability which were employed by Mr. Justice Clark, writing

for the court in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552, note 2

demonstrates that the results here are even less likely to

have occurred by chance than those condemned by the

court in Whitus. Mr. Justice Clark used and referred to

the method described in Finklestein, The Application of

Statistical Decision Theory to Jury Discrimination Case,

80 Harv. L. Rev. 338 (1966) which involves use of the

Chi-Square test, Finklestein, supra at 365-373.18

By application of the Chi-Square test described in

Finklestein, supra, to these facts we find that assuming

there was a random selection from the eligible population

of males over 21 (containing 2247 Negroes and 775 whites),

the probability of getting (1) 26 or fewer Negroes on a jury

roll of 374; (2) 62 or fewer Negroes on a jury roll of 374;

(3) 16 or fewer Negroes on a jury roll of 353 are truly

astronomical. (Note that the “62” figure assumes the cor

rectness of a finding of the Supreme Court of Alabama

which is not supported by the record.)

The probability of random selection of 26 or fewer Ne

groes is a number which is written as a decimal point

followed by 195 zeroes and then the number 8432. The

probability of 62 or fewer Negroes is a number written as

a decimal point followed by 143 zeroes and the number

2076. The probability that 16 or fewer Negroes could be

selected by chance is a number written as a decimal point

followed by 197 zeroes and then the number 2873. Thus,

under any formulation the probability of Negroes serving-

on the jury lists being accounted for by chance is signif

18 A readily available paperback book giving an explanation o f the

statistical method and written for laymen without mathematical training

is, Moroney, Facts from Figures (3rd and revised Edition, Baltimore,

Md., 1956, Penguin Books) 246-270.

24

icantly less than one chance in a trillion. The computation

of these results is set out in full in the appendix infra,

pp. 26a, 27a.

The disproportion between Negro and white jury ser

vice is also contrary to the idea that: “A jury is a body

of men composed of the peers or equals of the person whose

rights it is selected or summoned to determine; that is,

of his neighbors, fellows, associates, persons having the

same legal status in society as that which he holds.”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308 (1880). This

standard, that a jury must fairly represent the community,

was recently adopted by the Fifth Circuit in Labat v. Ben

nett, 365 F.2d 698, 720-24 (5th Cir. en banc 1966) relying

upon Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130 (1940); Glasser v.

United States, 315 U.S. 60, 86 (1941); Thiel v. Southern

Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946); Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S.

443, 474 (1953). See also opinion of Judge Bell joined by

Judge Coleman concurring in the result and referring to

the requirement of a “fair cross section of the community”

(365 F.2d at 740, 741). The Fifth Circuit also decided

that a “ fair cross section of the community was required

in the selection of federal court juries” Rabinowits v.

United States, 366 F.2d 34, 55, 56 (5th Cir. en banc 1966).

Far from reasonably reflecting that approximately eighty-

five percent of Greene County is Negro, the jury rolls in

the county are rather the organ of a “special group or

class”—the whites of the county—Glasser v. United States,

315 U.S. 60, 86 (1941). The very legitimacy of the jury

as the institution which passes judgment on the community

as a whole is impaired by such a result.

25

B. Vague and Subjective Standards for Selection of

Jurors Establish a Prima Facie case of Discrimina

tion.

The marked disproportion between Negro and white jury

service which could not have occurred by chance itself

establishes a prima facie case of discrimination which the

State must rebut. A prima facie case also is made out

under the rule of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)

for jury selection in Greene County operates within a

statutory framework which provides an “opportunity to

discriminate.” Because of inherent vagueness and delega

tion of unlimited, essentially unreviewable, discretion to

the jury commissioners, the Alabama statutory scheme

operates to provide the “ opportunity for discrimination”

which the racially designated source of names supplied in

Whitus at 385 U.S. 552. See also Bostick v. South Caro

lina, 18 L.Ed.2d 223 (1967).

In the selection of the jury lists the commissioners chose

only “male citizens of the county who are generally reputed

to be honest and intelligent men and are esteemed in the

community for their integrity, good character and sound

judgment” (Ala. Code, Tit, 30, §21 (Recompiled 1958).19

19 At the time the juries which indicted and convicted petitioner were

selected Title 30, §21 stated:

Qualifications of persons on jury roll.— The jury commission shall

place on the jury roll and in the jury box the names o f all male citi

zens of the county who are generally reputed to be honest and intel

ligent men and are esteemed in the community for their integrity,

good character and sound judgment; but no person must be selected

who is under twenty-one or who is an habitual drunkard, or who,

being afflicted with a permanent disease or physical weakness is unfit

to discharge the duties of a juror; or cannot read English, or who

has ever been convicted o f any offense involving moral turpitude. I f

a person cannot read English and has all the other qualifications pre

scribed herein and is a freeholder or householder his name may be

placed on the jury roll and in the jury box. No person over the age

26

It is settled, however, that when constitutional rights are

involved officials may not exercise a discretion which con

sists solely of their own subjective judgment. Require

ments of specificity are necessary to a determination of

the qualifications of jurymen in Greene County because

“exclusion from jury service . . . is at war with our basic

concepts of a democratic society.” Smith v. Texas, 311

U.S. 128, 130 (1940) and because (as with racial discrim

ination in voting)20 excessive discretion in the hands of

local officials thwarts nonracial selection. Smith v. Texas,

supra; Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698, 712, 713 (5th Cir.

en banc 1966).

The character and intelligence tests of §21 provide the

“ opportunity for discrimination” condemned in Whitus,

supra, because they are not described with sufficient preci

sion to enable one to know where the statute draws the

line between the qualified and the disqualified. The Court

has declared similar language permitting public officials

to make subjective decisions unconstitutionally vague:

“unreasonable charges” United States v. L. Cohen Grocery

Co., 255 U.S. 81 (1921); “unreasonable profits” Cline v.

Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445 (1927); “reasonable time”

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937); “sacrilegious”

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952); “ so

massed as to become vehicles for excitement” (a limiting

interpretation of “indecent or obscence” ) Winters v. New

York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948); “immoral” Commercial Pictures

of sixty-five years shall be required to serve on a jury or to remain

on the panel of jurors unless he is willing to do so.

In 1966, §21 was amended to permit females to serve as jurors, see

infra, pp. 20a-25a.

20 Condemnation of discretion in the hands of state voting officials is the

heart of two recent decision o f the Court. See United States v. Mississippi,

380 U.S. 128 (1965) and Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).

27

Corp. v. Regents of University of N. Y., reported with

Superior Films, Inc. v. Department of Education, 346

U.S. 587 (1954); “an act likely to produce violence” in

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963); “ sub

versive person” in Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964);

“reprehensive in some respect” ; “improper” ; and out

rageous to “morality and justice” Giaccio v. Pennsylvania,

382 U.S. 339 (1966). See also Staub v. City of Baxley,

355 U.S. 313 (1958); South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301, 312-313 (1966) ;21 Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145, 153 (1965); see also United States v. Atkins,

323 F.2d 733, 742-43 (5th Cir. 1963); Davis v. Schnell,

81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala.) aff’d per curiam, 336 U.S. 933

(1949); Board of Supervisors v. Dudley, 252 F.2d 372,

74 (5th Cir. 1958).

The record here fully confirms the inherent vagueness of

§21 and its capacity for arbitrary administration. The

officials charged with selection of jurymen considered

that Negroes as a class were overwhelmingly unqualified

(although the state’s evidence showed more Negroes than

whites graduated high school) but aside from unsatis

factory crime and high school graduation statistics, see

infra pp. 28-31, they offered nothing specific to explain

why they believed Negroes as a class less honest, esteemed,

or not of good character, integrity or intelligence. Faced

with the conclusory statements of white officials regarding

the relative qualifications of Negro and white residents,

petitioner presented witnesses who refuted these general

conclusions with those of their own to the effect that many

21 Dealing with voting qualifications imposed by South Carolina law

which are similar to those of Tit. 30, §21, the Court declared in South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 312-313 (1966) :

“ The good morals requirement is so vague and subjective that it has

constituted an open invitation to abuse at the hands of voting offi

cials.”

28

Negroes were qualified. Nothing demonstrates the inherent

vagueness of §21 more than the inability to appraise, and

to review, the contrary perceptions of Negroes and whites

as to the qualifications of members of the community. As

the court said in Whitus, supra: “under such a system,

the opportunity for discrimination was present and we

cannot say on this record that it was not resorted to by

the commissioners.”

C. The State Failed to Offer a Satisfactory Explanation

for the Gross Disparity Between Negro and White

Jury Service.

Petitioner’s prima facie ease placed a burden on the

state of coming forward with evidence and a constitu

tionally acceptable explanation for the facts creating the

inference of discrimination. But the state relied on con-

elusory “ opinion” evidence and high school graduation

and crime statistics to argue that ninety percent of the

Negro males of the county over 21 “were not fully quali

fied” Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552 (1967).

The Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed petitioner’s

death sentence on the ground that the state’s explanation

of the large racial disproportion was satisfactory. The

court did not, however, specify the evidence or the rea

soning which supported its conclusion that the “disparity

can be explained by a number of other factors” (R. 190)

other than that “Negroes who would be otherwise eligible

are moving away from the county because of lack of eco

nomic opportunity” (R. 190-91). The court totally rejected

the crime statistics (which did not reflect sex, residence

or recidivism) because they showed “ simply that the great

est number of crimes are committed by the race making-

up the greatest part of the population” (R. 190).22

22 The Circuit Judge had testified that Negroes committed 95% of the

serious crimes in the County and the Clerk of court testified that of 337

29

I f it were necessary to a decision of the case, this

Court could undertake the “duty to make independent

inquiry and determination of the disputed facts,” Pierre

v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1939), and “analyze the facts”

to protect the federal constitutional rights involved. Nor

ris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 590 (1935). But this is un

necessary because the only specific evidence offered by the

state totally fails to rebut the inference of discrimination.

General denials of the presence of sufficient qualified Ne

groes are insufficient to carry the state’s burden.

The testimony of the superintendent of schools as to

relative numbers of Negroes and whites who entered ele

mentary school between 1937 and 1948 and the numbers

who graduated twelve years later does not explain why so

few Negroes are selected as jurors. In the 1947-48 school

year 50 whites and 874 Negroes entered first grade. Twelve

years later, 29 whites and 119 Negroes graduated.23 One

might expect that there would be four times as many Ne

groes as whites on the rolls; four times as many Negroes

as whites graduated.

No level of educational attainment, moreover, much less

high school graduation, is a statutory prerequisite for jury

service in Alabama. The state did not link graduation

statistics to “intelligence” or “literacy” although proof of

felonies over the last 10 years, only 12 had been perpetrated by whites.

As 85% of the total population of Greene County is Negro it is not sur

prising that Negroes are convicted for about 9 out of 10 crimes. Indeed,

the Negro conviction rate may be to some extent explained by the very

jury discrimination which is asserted here, for a judicial system in which

Negroes rarely serve is more likely to indict and convict Negroes unfairly

than whites.

23 These statistics were not broken down on the basis o f sex and did

not reflect change in residence. The superintendent conceded that many

Negroes could have finished school in other jurisdictions and that this

would not be reflected in the statistics offered.

30

such a relationship is necessary to meet it’s burden. When

questioned as to the relationship between high school grad

uation and intelligence, the superintendent of schools con

ceded men can be and are “intelligent” , as well as esteemed

in the community for their integrity, good character, and

sound judgment without having graduated high school. As

the literacy requirement of §21 is waived in the case of

property owners, of which there are a great many Negroes

in Greene County, it hardly serves as a statutory qualifica

tion to which high school graduation might relate. Never

theless, even if literacy were required unconditionally, high

school graduation statistics, as the superintendent con

ceded, would not establish a comparative literacy rate. 42

U.S.C. §§1971 (c), 1973b(e) set a sixth grade education as

a standard for presumptive literacy under the Voting-

Rights Act of 1965. If the state could have established that

insufficient numbers of Negroes were literate under this

standard, or any other, it had the proof within its power

to produce. Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.8. 354 (1939).

Reference to public documents shows, moreover, that

even if the state had produced such evidence it would not

have explained the disproportion. The Census Bureau has

not reported how many Negroes in Greene County over

the age of 21 have completed six years of school but the

statewide average at the last census showed that about

48% of adult male Negroes and 83% of adult male whites

have had 6 grades of schooling.24 If any average remotely

approaching this applies to Greene County, the rate of

illiteracy cannot (even if literacy were required uncon

ditionally as it is not under §21) explain the absence of

Negroes from the rolls. The ratio of white-Negro literacy

24 Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census, U.S. Census of Popula

tion: 1960, Yol. I, pt. 2 (Alabama).

31

is two-to-one not nine-to-one or less as represented on the

rolls.

While the Supreme Court of Alabama found Negro un

derrepresentation on the rolls justifiable, the court em

ployed conclusory language to affirm aside from stating that

many qualified Negroes left the county.25 This suggests

that the court found dispositive conclusory statements by

whites to the effect that few Negroes in the county were

qualified. These whites failed however, to offer any reason

why the Negroes who remained were as a class less honest,

intelligent, or esteemed than whites or not of good char

acter or integrity. As Negro witnesses testified that more

Negroes than whites were qualified and that many qualified

Negroes were never called to serve, the unsupported opin

ions of the whites can only be decisive under a reading of

§21 which necessarily accepts their subjective judgments.

Such a construction confirms the vagueness of the statutory

language and its capacity for arbitrary administration, see

supra, pp. 25-28. As long as the state’s explanation is

couched in general “opinion” terms it would be unthinkable

to accept the enormous variation in jury service because

this would be to accept without more the “ opinion” that

Negroes in Greene County are not honest and intelligent or

esteemed in the community for their integrity, good charac

ter and sound judgment. The Court has never permitted

25 One of the factors the Supreme Court of Alabama found to explain

the disparity was that “ many of the Negroes who would otherwise be

eligible are moving away from the county because of the lack of economic

opportunity existing in Greene County for them and other young people.

The members of the white and Negro races who would be a benefit to this

community and whose loss is felt in the country leave and hence leave

the community poorer for their loss” (R. 190-91). It is difficult to under

stand the manner in which this generalization explains the ineligibility

of ninety percent of the Negroes because as “ members of the white and

Ne°ro races . . . leave the community poorer for their loss” it is not con

tended that only eligible Negroes leave the county and no specific evidence

was offered.

general denials of discrimination or of Negro qualifications

to carry the state’s burden of overcoming a prima facie

showing. Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 555 (1967);

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 598 (1935); Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 289 (1949); Pierre v. Louisiana, 306

U.S. 354, 360 (1939).

The slight evidence offered by the state must be con

sidered in light of evidence which suggests that the com

missioners knew that they were restricting Negro partici

pation. For example, the commissioners relied on voter

registration lists, a source which Congress legislatively

determined to be discriminatory in Alabama by passage

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §§1973 et seq.

In August, 1962, subsequent to selection of Coleman’s juries,

Negro community leaders complained of lack of Negro

service on the juries. As a result, three Negroes were

asked to supply names and there was a modest increase in

the number of Negroes who could be identified on the rolls

from 16 to 28 (R. 91, 145).

Alabama has delegated the broadest possible discretion

to those who select jurors. The results of this system,

whether tested intuitively or by statistical analysis, con

firm that the “opportunity for discrimination” was “re

sorted to by the commissioners” Whitus v. Georgia, 385

U.S. 545, 552 (1967). The evidence produced by the state

simply fails to rebut petitioner’s showing that his Four

teenth Amendment rights have been violated necessitating

reversal of the judgment below.

33

II.

Appellant was Deprived of Due Process of Law and

Equal Protection of tlxe Laws in Violation of the Four

teenth Amendment Because Women Were Totally Ex

cluded From the Juries Which Indicted, Convicted and

Sentenced Him.

The grand jury which indicted petitioner and the trial

jury which convicted and sentenced him were chosen pur

suant to Ala. Code Ann., Tit. 30, §21 (1958 Recompiled),

which confined jury service to males. Subsequent to a dec

laration of the unconstitutionality of this provision by a

three-judge district court in White v. Crook, 251 F. Supp.

401 (M.D. Ala. 1966), §21 was amended. Females are now

eligible jurors in Alabama although they may be excused

for good cause in the discretion of the trial judge, Acts

Nos. 284, 285 of September 12, 1966 (Special Session).26

Petitioner’s sentence of death turns, however, on the dis

position of his obviously substantial claim that by excluding

the female population of Greene County, Alabama has

discriminated on the basis of sex in violation of his Four

teenth Amendment right to a jury selected from the com

munity without arbitrary exclusion. In Hoyt v. Florida,

368 U.S. 57 (1961), the Court in affirming the conviction

of a woman for second degree murder in the face of her

claim that Florida excluded women from jury service in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment expressly reserved

decision of whether a state may confine jury duty to males

consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment (Id. at p. 60).

26 See infra, p. 20a. Similar provisions remain in force in Mississippi

and South Carolina, Miss. Code Ann. 1942 (Recompiled Vol. 1958),

§1762; South Carolina Code 1952, §§38-52. See Williams v. South Caro

lina, 237 F. Supp. 360, 370 (E.D.S.C. 1965). (Exclusion of females con

stitutional.)

34

The court found that Florida had not arbitrarily under

taken to exclude women from jury service because the state

granted women an automatic exemption, subject to service

on a voluntary basis. The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice

Black, and Mr. Justice Douglas concurred upon finding a

“good faith effort to have women perform jury duty with

out discrimination on the basis of sex.” (Id. at 69). In

White v. Crook, supra, the district court declared Ala

bama’s exclusion of females under §21 to be “ so arbitrary

and unreasonable as to be unconstitutional.”

Petitioner respectfully urges the Court to adopt the

holding in White v. Crook, supra. There is no apparent

reason why women are any less qualified to render ser

vice as jurors than men. Perhaps the only justification

for their exclusion, one may suggest, is that women are

more likely to have family responsibilities which make

jury service a hardship, but the conclusion that women

may be declared ineligible for jury service does not follow

from this premise. The procedure approved in Hoyt v.

Florida, supra, or the common practice of granting an

exemption to women, subsequently adopted by the state,

present appropriate means to meet the states’ interest in

mitigating hardships flowing from jury service.

The answer to the argument that “the Fourteenth Amend

ment was not historically intended to require the state

to make women eligible for jury service” is that it “re

flects a misconception of the function of the Constitution

and this Court’s obligation in interpreting it” (White v.

Crook, supra at 408), see Harper v. Virginia Board of

Elections, 383 IJ.8. 663, 669 (1966) (“notions of what con

stitutes equal treatment for purposes of the equal pro

tection Clause do change” ) (emphasis in original).

35

Appellant, a male, lias standing to challenge the total ex

clusion of women from jury service in Alabama, for he is

entitled to a jury impartially drawn from the community

as a whole. Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128; Labat v. Ben

nett, supra. See also Allen v. State, 137 S.E.2d 711, 110

Ga. App. 56 (1964) (white may complain of Negro ex

clusion from jury). As the Court; said in Ballard v. United

States, 329 U.S. 187, 193-94 (1946) :

The truth is that the two sexes are not fungible; a

community made up exclusively of one is different from

a community composed of both; the subtle interplay of

influence one or the other is among the imponderables.

To insulate the courtroom from either may not in a

given case make an iota of difference. Yet a flavor, a

distinct quality is lost if either sex is excluded. The