Correspondence from Robert W. Marx (Bureau of the Census) to Lani Guinier; 1980 Census Population Counts by Race for Arkansas Counties

Correspondence

May 14, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Robert W. Marx (Bureau of the Census) to Lani Guinier; 1980 Census Population Counts by Race for Arkansas Counties, 1987. df71dc55-ea92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d31613a4-e745-4f33-989e-2e4ec40d85ea/correspondence-from-robert-w-marx-bureau-of-the-census-to-lani-guinier-1980-census-population-counts-by-race-for-arkansas-counties. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

ffi BxlS3"?IilI}.[PARrmEilr

oF GommERcE

Wuhington. O.C. 90233

a1

./P

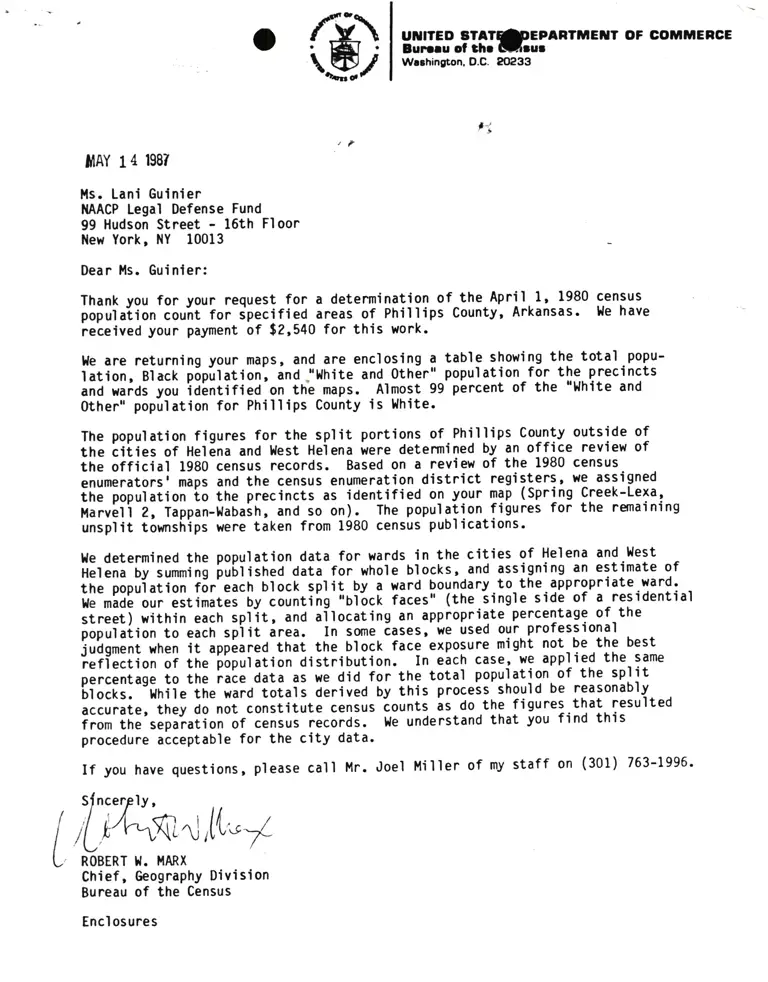

llAY 1 4 1987

ils. Lani Gulnier

iIAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street - l6th Floor

l{ew York, NY 10013

Dea r ils. Gui nl er:

Thank you for your request for a determination of the April.l' 1980 census

popriaiion ior-nt for specified areas of Phillips County, Arkansas. l'le have

received your payment of $2,540 for this work-

l{e are returning your maps, and are enclosing a table showi!9 the total popu-

lation, Black p6pirtation, ind."Uhite and 0ther" population-for the precincts

inO *i.Ai you iOlntified-on thL maps. Almost 99 percent of the uUhite and

0ther" popul ation for Phi I I i ps County i s l'lhite.

The population figures for the split portions of Phillips County outside of

tne tittes of Helina and Iest Heiena were determined by an office review of

the official 1980 census records. Based on a review of the 1980 census

"nrr...torr'

,.pr and the census enumeration district regig!er:, we assigned

Iii" popriuiion io ttre precincts as identified on your map (Spring Creek-Lexa,

Uarvlli Z, tappan-llabaih, and so on). The population figures for the remaining

unsplit townsirips were taken from 1980 census publications.

t{e determined the population data for wards in the cities of Helena and }'lest

ietena-by iummins prLiiinea outa for whole blocks, and assigning an estimate of

ine popuiation f6r'eictr block split by a ward boundary.to-the.appropriate.ward'

l{e made our esttmitei-uy-coJntihg iui-oct faces" (the-single side of a residential

ri...il within eictr split, and ailocating an appropriat. q.!9:ltage of-the

popuiaiton to "ait

spiit irea. In some iases' we used our professional

juhgment when it ippiarea that the block face exposure might not be the best

reflection of tft.-['opriiiion distribution. In eich case' we applied the same

percentage to the i'ate data as we did for the total popu]ation.of the split

blocks. t{hile the ward totals Oerived by this proceis should be reasonably

accurate, they do not constitute census Lounts as do the figures that resulted

from the separation of census ...oiOi. l{e understand that you find this

procedure acceptable for the city data.

If you have questions, please call l,lr. Joel l'tiller of my staff on (301) 763-1996'

;[iT:k^] ,r(*

ROBERT ll. l,lARX

Chief , Geography Division

Bureau of the Census

Encl os ures

1980 Census Populatlon Counts bY

Helena and llest Helena, and for

Race for Speclfled Areas of the Cltles of

the Balance of Phllllps County, Arkansas

PouI atl on

Total Black and 0therArea l{ame

Helena clty

llard I

llard 1A

llard 2

t{ard 2A

lJard 3

llard 4

Hest Helena city

Uard I

Iard 1A

l{ard lB

Ilard 2

Hard 2A

l{ard 28

lla rd 3

llard 38

l{ard 4

Hard 4A

Iard 48

llard 4C

Hard 4C2

Balance of Phillips County

Spring Creek-Lexa

Lexa

Spring Creek-Barton

Spring Creek-Oneida

l*la rvel I I

ilarvel I 2

ilarvel'l 3

Hi ckory Ri dge-ilarvel I

Upper Bi g Creek

Lower Big Creek

Lakevi ew

Tappan-Lakevi ew

Tappan-t'labash

Tappan-Lambrook

Tappan-El ai ne

Elaine I

Elaine 2

9,598

2,093

641

1,234

914

2,210

2,506

ll,367

2,292

17?

352

I,818

899

63

1 ,125

I,791

922

267

478

297

891

5,796

I,700

584

511

390

733

I,878

4,905

2,249

53

82

44

75

45

68

219

896

267

477

?84

146

3,802

393

57

723

524

1,477

628

6,462

43

119

?70

1,774

824

l8

I,057

1,572

26

0

I

l3

745

391

3s3

951

4s6

256

491

977

639

577

ll5

608

?35

422

606

547

687

304

105

r30

467

3?9

2

0

773

345

456

80

s89

133

222

260

331

453

0

286

223

484

t27

254

491

204

294

lzl

35

l9

t02

200

346

2t6

234

304

1980 Census Populatlon

Helena and l{est Helena, and

Area Name

Counts by Race for Speclfled Areas of the Cttles of

for the

-Balance of Phllllps County, Arkansas (contlnued)

Pooul atl on

,?

Unspllt Areas

Cleburne tormship

Cleveland townshiP

Cypress township

Hicksville tormshlp

Horner townshi p

(outslde citles)

James R. Bush town-

ship (Lakeview

portion onlY)

Lake township

L'Anguille townshlP

Flari on townshi p

i{ooney township

St. Francis township

(outside Helena)

534

439

189

424

1,177

I

181

29

1,029

778

4ll

202

233

lr9

79

680

0

95

20

379

?75

83

332

206

70

345

497

I

86

9

650

503

328