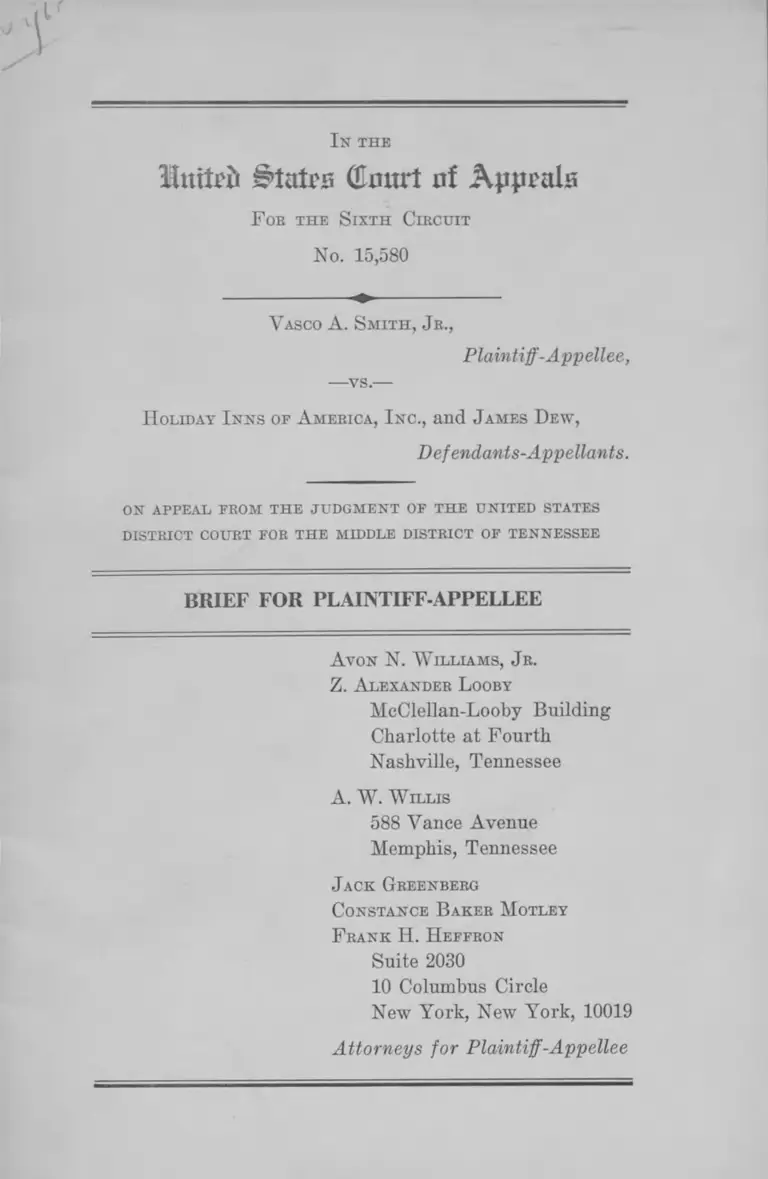

Smith v Holiday Inns of America Brief for Plaintiff Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Holiday Inns of America Brief for Plaintiff Appellee, 1965. 2f0c0ca3-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d319bebb-0d65-43fa-ab95-c0236e7efd4a/smith-v-holiday-inns-of-america-brief-for-plaintiff-appellee. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

luitri} #tatrs (Emu*! of Ajijirals

F or the Sixth Circuit

No. 15,580

I n the

V asco A. Smith, Jr.,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

—vs.—

H oliday I nns of A merica, I nc., and James Dew ,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL FROM THE JUDGMENT OF THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. Alexander Looby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

A. W . W illis

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

F rank H. Heffron

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee

Counter-Statement of Questions Involved

1. Does racial discrimination by a redeveloper of land

in an urban redevelopment project conceived, sponsored,

and controlled by state and federal agencies violate the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution!

The District Court answered “ yes.”

The plaintiff-appellee contends that the answer should

be “yes.”

2. Did the District Court have power under 28 U. S. C.

§1343 and 42 U. S. C. §1983 to redress the denial of the

plaintiff-appellee’s constitutional right?

The District Court answered “yes.”

The plaintiff-appellee contends the answer should be

“yes.”

I N D E X

PAGE

Counter-Statement of F acts.............................................. 1

A rgument :

I. Does Eacial Discrimination by a Redeveloper of

Land in an Urban Redevelopment Project Con

ceived, Sponsored, and Controlled by State and

Federal Agencies Violate the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution?

The District Court answered “ yes.”

The plaintiff-appellee contends that the answer

should be “yes” ...................................................... 8

II. Did the District Court Have Power Under 28

U. S. C. §1343 and 42 U. S. C. §1983 to Redress

the Denial of the Plaintiff-Appellee’s Constitu

tional Right?

The District Court answered “yes.”

The Plaintiff-Appellee contends the answer

should be “ yes” ...................................................... 16

Cases Cited

Adams v. City of New Orleans, 208 F. Supp. 427 (E. D.

La. 1962), aff’d 321 F. 2d 493 (5th Cir. 1963) .......12,18

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .................................. 12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ........................................................8,10,12,13,14,15,17

11

PAGE

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957), affirming 149 F. Supp. 562 (M. D. N. C.

1957) ...............................................................................12,18

Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga.

I960) ...............................................................................12,18

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied sub nom. Casey v. Plummer, 355 U. S.

924 ............................................................................. 10,12,18

Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304 F. 2d 320 (5th

Cir. 1962), cert, denied sub nom. Ghioto v. Hampton,

371 U. S. 911..............................................................11,12,18

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501.................................... 11,14

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 ...................................... 16

Plummer v. Casey, 148 F. Supp. 326 (S. D. Tex. 1955) .. 18

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital (4th Cir.,

No. 8908, November 1, 1963) ............................12,13,15,18

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 ...................................... 11

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 .................................12,17

Other A uthorities Cited

12 U. S. C. §1716K............................................................. 5

28 U. S. C. §1343(3) ........................ ...... ... ........... ...16,17,18

42 U. S. C. §1983 ............................................................... 16, lg

I k the

llmtvb States (Eaurt n! Apprals

F or the S ixth Circuit

No. 15,580

V asco A. Smith, Jr.,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

— vs.—

H oliday Inns o f A merica, Inc., and James Dew,

Defendants-Appellants.

ON APPEAL f r o m t h e j u d g m e n t of t h e u n it e d s t a t e s

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE

Counter-Statement of Facts

With the exception of certain matters mentioned below,

plaintiff-appellee does not dispute the defendants-appel-

lants’ statement of facts. It is submitted, however, that the

district court’s presentation of the facts in its opinion (App.

42a-53a), adopted as formal findings of fact in the judg

ment (App. 57a), is a more complete and balanced sum

mary of the material facts.1 This portion of the brief will

1 The district court’s opinion as printed in defendants-appellants’

appendix contains two minor typographical errors. On page 48a,

the amount spent on site clearance should be $99,500 rather than

$9,500. The amount spent on site development should be $2,491,967

rather than $2,492,967.

2

discuss the disputed portions of defendants-appellants’

statement of facts and direct the Court’s attention to some

evidentiary matters not included in the district court’s

findings.

In defendants-appellants’ statement of facts (Brief, p. 4),

it is asserted that the restrictions placed by covenant upon

land in the Redevelopment Project “were of the same type

that the City is authorized to place on property by virtue

of its zoning powers (Tennessee Code, Section 13-701)

whether or not the property is or ever has been owned by

any government or governmental agency.” While the cor

rectness of this statement is not disputed, it is pointed out

that the restrictive covenants covering the Project area are

a unique body of restrictions covering a distinct area of

land. Article V, section 6 of the covenants (App. 17a, 22a)

states that they “ are in addition to the provisions of the

zoning or building ordinances or any other regulations of

the City of Nashville. . . . ”

Defendants-appellants also assert that because the cove

nants permit several types of land use,

Holiday Inns of America, Inc., could, without violation

of its covenants, lease a portion of its building to a

club or a barber shop, convert the building into a club

house or an apartment hotel, sell the property for use

as a church, or do any number of things within the

permitted uses. The Nashville Housing Authority

could not lawfully have retained the right to forbid

uses permitted by the Redevelopment Plan, nor can

the deeds be fairly construed as giving The Nashville

Housing Authority any greater control over the prop

erty than the City has over all property within its

boundaries under its general zoning powers. (Brief,

P -5 ) .

3

This is extremely misleading. In the contract of sale Holi

day Inns agreed to construct a motel (App. 49b-50b, 92b,

52a-53a), not a clubhouse, church or other type of enter

prise. Plans and specifications for the motel were attached

to the contract of sale, and these had to be approved by the

Housing Authority.2 Article V, section 2 of the covenants

(App. 21a) provides that

“ No use or change in use shall be established or made,

nor shall any improvement be erected, constructed,

placed, or altered on any building site until the pro

posal for such use or improvement is first submitted

to and approved in writing by the Grantor” (emphasis

added).

In fact Holiday Inns actually submitted plans for an auto

mobile service station to be placed on property adjoining

the motel, but the Housing Authority disapproved (App.

49b-50b), even though the covenants did not prohibit such

a use (App. 50b, 22a-24a). In the words of Mr. Gerald

Gimre, Executive Director of the Nashville Housing Au

thority (App. 14b), “ It was just a matter of discretion”

(App. 50b). On another occasion a minor structural change

in the motel was approved (App. 51b).

Several factual matters relied on by plaintiffs below were

not included in the district court’s findings of fact or con

sidered in the opinion. Although it seems clear that the

court’s conclusions of law were amply supported by the

facts relied upon in the opinion, these additional factors

are presented for this Court’s consideration.

As administrator of the Capitol Hill Redevelopment

Project, the Nashville Housing Authority had the respon

2 See also the deeds conveying the properties, App. 30a, 32a-33a,

34a, 37a.

4

sibility for relocating the persons living in the area. Of the

301 families residing in the area, 288 were Negroes; 180

of the 196 individuals living alone were Negroes (App.

128b). An effort was made to place these dispossessed per

sons in public housing projects operated by the Housing

Authority, all ten of which are strictly segregated accord

ing to race (App. 63b). However, most residents of the

Project area were placed in substandard housing (App.

128b).

When the Redevelopment Plan was before the City Coun

cil of Nashville on April 29, 1952, Councilman Z. Alexander

Looby offered an amendment stipulating that occupants of

the land in the Project area be given preference on resale

of the land. This amendment was voted down. (App. 54b,

83b, 132b, 134b).

The Loan and Grant Contract between the Federal Gov

ernment and the Nashville Housing Authority included

among its comprehensive regulations a provision prohibit

ing racial discrimination against employees working in the

development of the Project. Nevertheless, the Housing

Authority approved the specifications submitted by Holiday

Inns which stated that racially segregated toilet facilities

would be provided for construction workers (App. 66b-68b).

In the early 1950’s the management of Holiday Inns was

looking for a suitable motel site in the center of Nashville

when it learned of the availability of land in the Project

area. Mr. Charles M. Collins, Vice-President and General

Counsel of Holiday Inns remarked, “ . . . there is a slogan in

the motel business in selecting a site for a hotel or motel

or inn, that the three most important things are location

and location and location” (App. 143b). Among the factors

5

which made Project land suitable for motel purposes were

its proximity to the Capitol and downtown office buildings

and its location on the newly constructed James Robertson

Parkway (App. 143b, 144b), which is on major interstate

highway routes (App. 100b-103b).

The Capitol Hill Redevelopment Project has transformed

a large segment of downtown Nashville from a run-down

slum into a modern, attractive, and prosperous center for

municipal and commercial affairs (Photographs,3 App.

147b). Several new buildings of modern design, including a

Municipal Auditorium and a Municipal Parking Garage,4

have been erected, and others are to be erected when the

remaining land is sold. Property values have increased to

such an extent that the City of Nashville already receives

twice as much revenue from property taxes as it did before

the Project was undertaken even though approximately

one-third of the marketed land was sold to tax-exempt or

ganizations (App. 42b, 90b, 91b, 131b).

In accordance with local law, Holiday Inns secures vari

ous licenses from the City of Nashville and from Davidson

County permitting it to operate a motel with restaurant

and bar (App. 116b-118b).

3 The photographs comprising Plaintiff’s Exhibit 3C show por

tions of the Capitol Hill area as it looked before the Redevelop

ment Project (App. 123b, 126b). Those in Plaintiff’s Exhibit 7

are more recent (App. 72b-74b, 81b-82b).

1 See App. 76b. Of the 72 acres in the Project, 35.22 acres are

used for streets, alleys, and public right-of-way. An additional

6.64 acres are set aside for public and semi-public uses, such as the

municipal facilities mentioned above (App. 128b, 130b). In addi

tion, two large apartment buildings built in the Project area were

financed by mortgage loans insured on extremely favorable terms

by the Federal Housing Authority, in accordance with a special

statutory provision, 12 U. S. C. §1716K, relating to housing in

urban renewal and redevelopment areas (App. 42b-46b, 94b-96b

121b).

6

At the time of trial, no motels in the downtown section

of Nashville, the capital of Tennessee, admitted Negroes as

paying guests (App. 108b, 113b).

Plaintiff-appellees submit that Holiday Inns paid con

siderably less than the fair market value of the two parcels

of land purchased from the Housing Authority.5 Two quali

fied real estate men, James F. McClellan and A. C. Walker,

both experienced in appraising property values in down

town Nashville, testified that land in the Project area on

James Robertson Parkway normally would have sold at

$3.50 per square foot (App. 107b, 112b). Based on these

measures, the value of Parcel G (44,582 sq. ft.) was $156,037

as opposed to the $90,029.00 paid, and Parcel H was worth

$162,200.50 rather than $104,742.00.

Mr. Gimre testified that the Housing Authority hired

independent appraisers to calculate the fair market value

of properties in the Project area, and that the federal regu

lations limited sales to a range of 10% below and 15%

above appraised value (App. 24b-26b, 55b). However, Mr.

Hershell Greer of the Guaranty Realty Company, which

handled land disposition for the Housing Authority, testi

fied that the latest appraisal figures supplied to him by the

Authority were $2.60 per square foot for Parcel G and $2.90

per square foot for Parcel H (App. 93b, 97b-99b, 135b).

The following figures demonstrate the advantage received

by Holiday Inns:

5 The issue of fair market value is the only factual matter remain

ing in the case about which there was any substantial dispute.

7

Appraised value per square

Number of square feet

Total value

10% of value

Value reduced by 10%

Price paid by Holiday Inns

Difference

Parcel G Parcel H

$2.60 $2.90

44,582 46,343

$115,913.20 $134,394.70

11,591.32 13,439.47

104,321.88 120,955.23

90,029.00 104,742.00

$ 14,292.88 $ 16,213.23

Thus, even if the land had been sold at 10% below ap

praised valuation, Holiday Inns would have had to pay

$30,000 more than it paid. If it had paid full market value

as computed by the Housing Authority’s appraisers, it

would have had to pay approximately $55,000 more than

it paid.

8

A R G U M E N T

I

Does Racial Discrimination by a Redeveloper of Land

in an Urban Redevelopment Project Conceived, Spon

sored, and Controlled by State and Federal Agencies

Violate the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution?

The District Court answered “ yes.”

The plaintiff-appellee contends that the answer should

be “ yes.”

Appellee was refused accommodations in the Holiday

Inn-Capitol Hill motel solely because of his race (App. 43a;

220 F. Supp. 1, 2). It is well settled that “private conduct

abridging individual rights does no violence to the equal

protection clause unless to some significant extent the State

in any of its manifestations has been found to have become

involved in it.” Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715, 722. The question presented here is whether

the state and federal governments have been shown to he

significantly involved in the conduct of Holiday Inns of

America.

It is submitted that the extent of governmental involve

ment present in this case is more than sufficient to impose

a duty of nondiscrimination on the management of the

motel. A brief review of the facts illustrates the tremendous

scope of governmental action and the relationship of mutual

dependence existing between this motel and the state.

The State of Tennessee created the Nashville Housing

Authority to deal with problems of urban housing and re

development. The Housing Authority undertook a study

of the Capitol Hill area and determined that the extreme

9

slum conditions existing there were detrimental to the eco

nomic and social health of the city, in addition to providing

an unsatisfactory setting for the State Capitol Building.

The Authority’s studies were subsidized by the Housing and

Home Finance Agency of the United States Government.

A plan for slum clearance was formulated, and approvals

were obtained from the Planning Commission, City Council,

and Mayor of the City of Nashville, which undertook to pay

one-third of the net cost of the Project. Approval was also

secured from the federal government, which agreed to pay

two-tliirds of the net cost of the project if certain standards

were met. (The net cost is expected to amount to more

than $7.8 million.) Meanwhile, the State of Tennessee was

devising an interdependent plan to acquire other lands sur

rounding the Capitol for various state purposes. With the

full force of the federal, state and local governments placed

behind its effort, the Nashville Housing Authority carried

its plan into execution, acquiring 72 acres of slum lands,

clearing all the structures from them, installing facilities

for all types of utility services, constructing a wide boule

vard, and landscaping the area. It then sold 38 acres to

private entities for continued execution of the plan.

An integral part of the redevelopment plan is the par

ticipation of private business. Sale of the developed sites

substantially reduces the net cost of the project to the gov

ernment. Each purchaser provides the capital for the erec

tion of a business enterprise and enjoys the profits accruing

from its operation. The likelihood of profit is enhanced by

the fact that each business is surrounded by other modern

buildings in an attractively planned setting created by the

government. In return for these unquestioned business ad

vantages, the purchaser submits to a comprehensive regula

tion: it is obligated to build a suitable structure within a

limited amount of time; it must carry on only the type of

business which fits into the general plan; it must obey spe

10

cial zoning regulations in addition to those imposed on

other property owners. And, of course, the city receives

greatly increased tax revenues from the redeveloped land.

These numerous and pervasive forms of governmental

participation amount to significant state involvement in

the motel. They lend full support to the district court’s

conclusion that:

Extensive involvement by the state, in many and varied

forms and through various agencies, is evident not only

in the conception, formulation, development, and carry

ing out of the over-all public plan and project, but also

in its continuation and perpetuation. The two aspects

of the Project must not be overlooked, i.e., the clear

ance of the area of slums, and its redevelopment under

a state-designed plan to be maintained under state con

trol and supervision (App. 55a; 220 F. Supp. at 8).

It is important to stress that this is not a case in which

the State is merely a link in the chain of title. Neither is

this a case in which the fact of prior development of the

property, without more, is asserted to amount to “ state

action” (App. 43a-44a, 220 F. Supp. at 2). Nor is this a

case involving the sale of “ surplus property” 6 where the

State has no concern in the use of the property. In this

case, the State has not only conceived and executed the

plan, but has retained strict supervisory powers over the

use of the land to ensure fulfillment of the purposes of the

plan. Appellants do not dispute these findings. Rather

they attempt to belittle their significance by contending

that they amount to no more than normal zoning regula

tions.

6 See Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922, 925 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied 353 U. S. 924; Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715, 723-724.

11

The controls imposed on Holiday Inns by the contract

of sale, the deeds, and the restrictive covenants far exceed

those of normal zoning regulations. The covenants, like

typical zoning provisions, do regulate such matters as re-

subdivision, building heights, display signs, and loading

practices (App. 24a-26a), but they are special limitations

applicable to a unique group of property owners. More im

portantly, Holiday Inns operates under restrictions never

contemplated by usual zoning and building ordinances.

Upon purchase of the land, Holiday Inns freely bargained

away some of the most valuable incidents of property own

ership. It gave up the right to choose whether to develop

the property, when to build, what to build, or how to build.

Holiday Inns, or any grantee from it, cannot change the use

of the building site or make any structural alteration with

out written permission from the Housing Authority. It

undertook to conduct its business so that the governmental

purposes which gave rise to the plan would be served.

Thus it matters little that the form of the transaction was

a sale rather than a lease. As the district court held, “ The

crucial test of state action is the actuality of state involve

ment rather than the form of the transaction” (App. 55a;

220 F. Supp. at 8). In Hampton v. City of Jacksonville,

304 F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied sub nom. Ghioto

v. Hampton, 371 U. S. 911, the city sold its golf course to

bona fide vendees, but the interest it retained in restricting

the property’s use subjected the vendees to the strictures

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

It is well-settled that “ private” organizations may be re

quired to uphold basic constitutional standards. In Terry

v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461, a “ private” political organization

meticulously isolated from the state electoral machinery

was forbidden to hold primary elections from which Negroes

were excluded. In Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, a pri

12

vate corporation with no governmental status, but owning

all the land in a town, was forced to recognize Fourteenth

Amendment rights. And in Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U. S. 715, the private lessee of a state agency

similar in many respects to the Nashville Housing Authority

was forced to abandon its racially discriminatory policy of

customer selection.7 Several other cases have held that

private lessees of state-owned property or vendees of state-

restricted property may not discriminate. See, e.g., Der-

rington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956), cert,

denied, 353 U. S. 924; Hampton v. City of Jacksonville, 304

F. 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 371 U. S. 911; City

of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir. 1957) ;

Adams v. City of New Orleans, 208 F. Supp. 427 (E. D.

La. 1962); Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D.

Ga. 1960).

Thus the test is not whether the actor is “ private” or

“ public” ; it is whether the state is involved to a significant

extent in private conduct. The Fourth Circuit recently ap

plied the rationale of the Supreme Court decision in Burton

to a case involving two “ private” hospitals. Simkins v.

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital (No. 8908, November 1,

1963). The court held that the hospitals’ participation in

a “ joint federal and state program allocating aid to hospital

facilities throughout the state” subjected them to the pro

hibitions of the Fifth8 and Fourteenth Amendments. Two

relevant factors in the Fourth Circuit’s decision were “ the

massive use of public funds” and “ extensive state-federal

sharing in the common plan.”

7 Followed in Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350.

8 Defendants-appellants argued that the Fifth Amendment has

no provision applicable to this case (Brief, pp. 18-19). The due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment condemns racial discrimi

nation by the federal government. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497.

13

The court wrote:

Not every subvention by the federal or state govern

ment automatical}- involves the beneficiary in “ state

action” , and it is not necessary or appropriate in this

case to undertake a precise delineation of the legal rule

as it may operate in circumstances not now before the

court. Prudence and established judicial practice coun

sel against such an attempt at needlessly broad adjudi

cation. Our concern is with the Hill-Burton program,

and examination of its functioning leads to the conclu

sion that we have state action here. Just as the Court

in the Parking Authority case attached major signifi

cance to the “ obvious fact that the restaurant is oper

ated as an integral part of a public building devoted to

a public parking service,” 365 U. S. at 724, we find it

significant here that the defendant hospitals operate

as integral parts of comprehensive joint or intermesh

ing state and federal plans or programs designed to

effect a proper allocation of available medical and hos

pital resources for the best possible promotion and

maintenance of public health. Such involvement in dis

criminatory action “ it was the design of the Fourteenth

Amendment to condemn.”

In this case it seems significant that the motel’s operation

is an integral part of a comprehensive state and federal plan

to revitalize the downtown section of Nashville.

It is submitted that the facts in both the Simkins case

and this case represent stronger instances of significant

governmental involvement than those in the Burton case, in

which there was little more than an arm’s length business

transaction between the state and a private business. The

state’s only purpose in leasing space to the restaurant was

to augment revenues from the parking project. 365 U. S. at

14

719. Here the motel is more closely supervised, and its

operation is essential to the success of the government’s

plan.

Appellants argue (Brief, pp. 11, 27-28) that the judg

ment below must be reversed because it ipso facto requires

the identical result in the case of a church or clubhouse

located in the Capitol Hill Redevelopment Area. But the

status of a a church or clubhouse is not in issue in this

case and need not trouble the Court at this time. More

over, the identical result need not in fact be reached in

those situations, because weighty constitutional interests

of privacy, association, and the free exercise of religion

might there compel different results. Here, the motel is

in the business of serving the public. “ The more an owner,

for his advantage, opens up his property for use by the

public in general, the more do his rights become circum

scribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of those

who use it.” Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 506.

Finally, it is necessary to dispel any confusion that ap

pellants may have generated over the definition of the

constitutional right in this case. Appellants erroneously

assert (Brief, p. 12) that the District Court held that “ a

Negro has the ‘ right’ to be served or accommodated without

discrimination by any business establishment or non-busi

ness establishment in the State of Tennessee; but his right

to relief is dependent on state involvement to a significant

extent in the proprietor’s conduct.” Having thus defined

the terms, appellants naturally found a “ self-contradic

tion” in terms. What the District Court held was that,

pursuant to Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365

U. S. 715, appellee had a right to be free from racial dis

crimination in a motel in which the State was to a significant

extent involved.

15

Moreover, appellants misconstrue the Burton definition

of state action by suggesting (Brief, p. 34) that they must

be shown to have acted “ as an arm, branch, agency or in

strumentality of the state in denying motel accommodations

to the plaintiff.” The District Judge in Simkins v. Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital, supra, fell into the same error

and was reversed. The Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit said:

In the first place we would formulate the initial ques

tion differently [from the District Judge] to avoid

the erroneous view that for an otherwise private body

to be subject to the antidiscrimination requirements

of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments it must actu

ally be “ render[ed an] instrumentality] of govern

ment— .” [Quoting the District Judge]. In our view

the initial question is, rather, whether the state or the

federal government, or both, have become so involved

in the conduct of these otherwise private bodies that

their activities are also the activities of these govern

ments and performed under their aegis without the

private body necessarily becoming either their instru

mentality or their agent in a strict sense.

In conclusion, appellee submits that in this case the gov

ernment is so inextricably involved in assisting and con

trolling the ultimate redevelopment that fairness to all

the people represented by government requires use of the

property unrestricted by consideration of race.

16

II

Did the District Court Have Power Under 28 U. S. C.

§13-13 and 42 U. S. C. §1983 to Redress the Denial of

the Plaintiff-Appellee’s Constitutional Right?

The District Court answered “ yes.”

The Plaintiff-Appellee contends the answer should be

“ yes.”

The district court properly held that appellee had been

deprived of his constitutional right to be free from racial

discrimination by a motel in which the state is to a signi

ficant extent involved. Therefore, the district court held,

without discussion, that it had power under 28 U. S. C.

§1343 (3) and 42 U. S. C. §1983 to provide redress (App.

pp. 43a, 57a). Discussion seemed hardly necessary, for

Congress, through the enactment of the Civil Rights Acts,

has mandated federal courts to redress deprivations of con

stitutional rights.9

Appellants, however, challenge the power of the district

court to redress the violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

established in this case. They contend that they have not

been shown to have acted “ under color of any State law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage” .

Appellee submits that precedent and policy make clear

beyond cavil that the quoted term is not to be construed

so as to prevent federal courts from redressing deprivations

of constitutional rights.10 Rather, the term is to be con

9 See Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, 171:

Its [section 1983’s] purpose is plain from the title of the

legislation, “An Act to enforce the provisions of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States,

and for other purposes.” 17 Stat. 13.

10 See Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167, where that term was con

strued to embrace defendants who acted in defiance of state law.

17

strued so as to impose a requirement that will be satis

fied by the same nexus of state controls that satisfies the

Fourteenth Amendment requirement of “ state action” .

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 is squarely in point.

Turner was a suit brought under 28 U. S. C. §1343(3) and

42 U. S. C. §1983 to enjoin the defendant restaurant, a

lessee of the City of Memphis, from segregating its cus

tomers. The suit was ordered held in abeyance in the dis

trict court pending a state court suit. Plaintiff appealed

this order to the United States Supreme Court. At oral

argument before the Court the defendant conceded that it

“was subject to the strictures of the Fourteenth Amend

ment under Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority” (369

U. S. at 353). This concession ended the case. The Court

said:

On the merits, no issue remains to be resolved. . . .

[T]he case is remanded to the District Court with

directions to enter a decree granting appropriate in

junctive relief against the discrimination complained

of. 369 U. S. at 353-354.

In short, once a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

was established, the power of the federal courts to afford

relief was beyond question. This Court, on April 11, 1962,

ordered the District Court for the Western District of

Tennessee to enter an injunction against the defendant,

which it did on May 11, 1962.

Appellants seek to escape the command of Turner v.

Memphis by arguing that there the defendant made the

mistake of invoking certain state statutes as a defense—

thereby supplying the element of action “ under color o f”

law— rather than having had the suit dismissed for lack of

jurisdiction. This argument is fallacious. It is perfectly

plain that those statutes had nothing to do with the power

18

of the federal court, for the unconstitutionality of those

statutes, insofar as they applied to the case, was so patent

as to raise a legal issue “ wholly insubstantial, legally

speaking nonexistent” , 369 U. S. at 33.

Lower federal courts have had no difficulty in deciding

that federal courts have power to enjoin racial discrimina

tion by privately owned or operated public accommodations

in which the state is to a significant extent involved.11 The

decisions have generally been without discussion, but ab

sence of discussion does not mean absence of decision. In

Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga. 1960),

a suit to desegregate a leased airport restaurant, the de

fendants were both public and private parties. The court

held, “ This Court has jurisdiction of this cause by virtue

of the provisions of Title 28, U. S. C. §1343 and Title 42,

U. S. C. §1983.” Id. at 583. See also, Plummer v. Casey,

148 F. Supp. 326, 327 (S. D. Tex. 1955).

It is axiomatic that the jurisdiction of federal courts is

always under scrutiny. It is wholly unrealistic to assume

that the innumerable federal courts that have enjoined

discrimination by private parties closely associated with

the state have done so on the blind assumption that juris

diction was present. Rather, it would appear that the issue

is so well settled that extended discussion would be super

fluous.

11 Adams v. City of New Orleans, 208 F . Supp. 427 (E . D. La.

1962), aff’d 321 F. 2d 493 (5th Cir. 1963) (leased restaurant in

municipal airport); Herrington v. Plummer, 240 F . 2d 922 (5th

Cir. 1956), cert, denied 353 U. S. 924 (leased cafeteria in court

house) ; City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F . 2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957), affirming 149 F. Supp. 562 (M. D. N. C. 1957) (leased golf

course) ; Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga.

1960) (leased restaurant in Municipal airport); Simkins v. Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital (4th Cir., No. 8908, November 1, 1963)

(hospital receiving government fu n d s); Hampton v. City of Jack

sonville, 304 F . 2d 320 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, denied 371 U. S. 911

(golf course in which city had reversionary interest).

19

The Civil Rights Acts and corresponding jurisdictional

statutes were intended to empower federal courts to guar

antee constitutional rights. They should be so construed.

Specifically, the term “ under color of any State law, statute,

ordinance, regulation, custom or usage” must be construed

to impose a requirement which may be satisfied by the same

pervasive governmental involvement which satisfies the re

quirement of “ state action.” This is the most natural and

reasonable construction of the term, for if the State is so

involved in the motel as to render the motel’s actions im

putable to the State, then the motel’s actions must be under

color of State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom

or usage.

Respectfully submitted,

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander Looby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

A. W . W illis

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

F rank H. H effron

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee