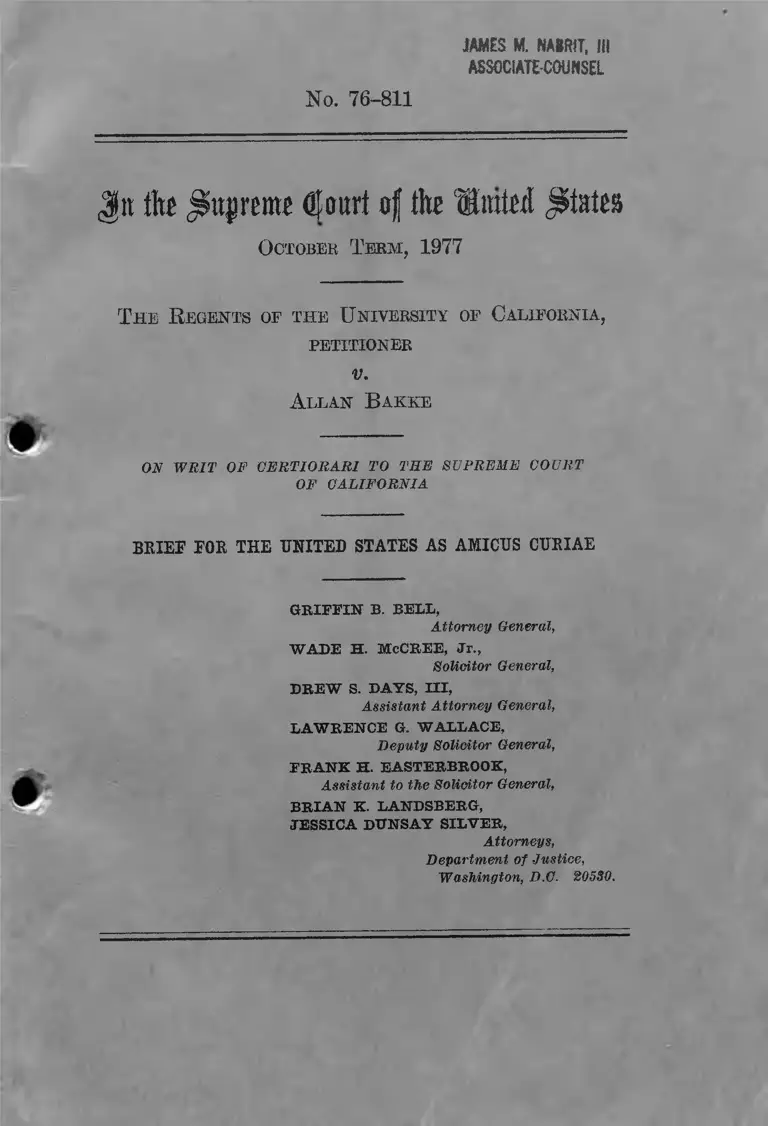

Bakke v. Regents Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1977. 7241b341-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3216c84-e8fa-4ffb-84bb-b67c0b3effb8/bakke-v-regents-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 76-811

JAMES M. NAIRfT, III

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

Jit the Supreme <£ourt of the 'fimtei states

O ctober T erm , 1977

T h e R egents of t h e U niversity of C alifornia ,

PETITIONER

V.

A llan B aickb

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

GRIFFIN B. BELL,

Attorney General,

WADE H. McCREE, Jr.,

Solicitor General,

DREW S. DAYS, III,

Assistant Attorney General,

LAWRENCE G. WALLACE,

Deputy Solicitor General,

FRANK H. EASTERBROOK,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG,

JESSICA DDNSAY SILVER,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Questions presented________________________________ 1

Interest of the United States________________________ 1

Statem ent-------------------------- 3

A. F ac ts_____________________________________ 3

1. The regular admissions process--------------- 5

2. The special admissions program._________ 7

a. Facial composition of applicants and

students _____________________ 9

b. Eligibility for the special admissions

program ____________________ 10

c. The process of selection__________ 12

d. Purpose of the program_________ 11

3. Respondent’s application_______________ 15

B. The state courts’ opinions_____________________ 17

1. The Superior Court____________________ 17

2. The Supreme Court of California________ 18

Introduction and summary of argument_______________ 23

Argument _______________________________________ 30

I. Race may be taken into account to counteract the

effects of prior discrimination______________ 30

A. This Court has held that minority-

sensitive decisions are essential to

eliminate the effects of discrimination

in this country__________________ 30

B. Both the legislative and executive

branches of the federal government

have adopted minority-sensitive pro

grams for the purpose of eliminating

the effects of past discrimination___ 33

(i)

245—950— 77- 1

II

Argument—Continued

II. The University could properly conclude that

minority-sensitive action was necessary to

remedy the lingering effects of past discrimi- page

nation -------------------------------------------------- 38

A. Minority-sensitive relief is not limited

to correction of discrimination perpe

trated by the institution offering

relief _________________________ 38

B. Discrimination against minority groups

has hindered their participation in the

medical profession---------------------— 41

III . The central issue on judicial review of a minority-

sensitive program is whether it is tailored to

remedy the effects of past discrimination---------- 50

A. A program is tailored to remedy the

effects of past discrimination if it

uses race to enhance the fairness of

the admissions process-------------- — 55

B. There is no adequate alternative to the

use of minority-sensitive admissions

criteria________________________ 68

IV. The Supreme Court of California applied incor

rect legal standards in evaluating the constitu

tionality of the special admissions program— 66

A. The declaratory judgment forbidding

the use of minority-sensitive admis

sions programs should be reversed— 66

B. Whether respondent was wrongfully

denied admission to the medical

school should not be decided on the

present record___________________ 67

Conclusion--------------- <4

Appendix A------------------------------------------ 1A

Appendix B---------------------------------------------------------- 3A

Appendix C_________________________ 4A

Appendix p ______________________________________ 9-4.

Ill

CITATIONS

Cases: page

Albemarle Paper Go. x. Moody, 422 U.S. 405_______24,32

Anderson x. Martin, 375 U.S. 399________________ 30

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc.

x. Altschuler, 490 F. 2d 9, certiorari denied, 416 U.S.

957 ________________________________________ 37

Boston Chapter, N.A.A.C.P., Inc. x. Beecher, 504 F.

2d 1017, certiorari denied, 421 U.S. 910___________ 30

Brown x. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483_________ 41

Galifano x. Webster, No. 76-457, decided March 21,

1977 --------------------------------------------------- 28,39, 64-65

Castaneda x. Partida, No. 75-1552, decided March 23,

1977 _______________________________________ 54

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylavina x.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F. 2d 159, certiorari denied,

404 U.S. 854 ________________________________ 34

Craig x. Boren, 429 U.S. 190_____________________ 54, 65

Cypress x. Newport News General and Nonsectarian

Hospital Association, 375 F. 2d 648_____________ 48

Dayton Board of Education x. Brinkman, No. 76-539,

decided June 27, 1977_________________________ 31

DeFunis x. Odegaard, 82 Wash. 2d 11, 507 P. 2d 1169,

vacated as moot, 416 U.S. 312___________________ 19

Dothard x. Rawlinson, No. 76—422, decided June 27,

1977 ------------------------------------------------------------ 40

Drummond x. Acree, 409 U.S. 1228____ ____________ 53

Endo, Ex parte, 323 U.S. 283____________________ 47

Franks x. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747__24, 31

Gaston County x. United States, 395 U.S. 285________ 56

Georgia x. United States, 411 U.S. 526____________ 32

Green x. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430________ 30,54

Griggs x. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424____________ 32

Hazelwood School District x. United States, No. 76-255,

decided June 27, 1977__________ _______________ 61

Hernandez x. Texas, 347 U.S. 475________________ 41

International Brotherhood of Teamsters x. United

States, No. 75-636, decided May 31,1977_______31,40, 55

Kahn x. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351____________________ 40

Keyes x. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189. 41

IV

Cases—Continued Page

Lav v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563--------------------------------- 41

Limnark Associates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro,

No. 76-357, decided May 2,1977_________________ 25,39

Lucas v. Forty-Fourth General Assembly of Colorado,

377 U.S. 713_________________________________ 54

Mathews v. Lucas, 427 U.S. 495----------------------------- 26,51

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39__________________ 40

McDonald v. Sante Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427

U.S. 273____________________________________ 52

MilliJcin v. Bradley, No. 76-447, decided June 27,1977_ 56

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337-------- 44

Morales v. New York, 396 U.S. 102----------------------- 23

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535--------------------------- 54

Mt. Healthy City School District Board of Education

v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274________________________ 72

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43__________________________________24,31

Northeast Construction Co. v. Romney, 485 F. 2d 752_ 34

Otero v. New York City Housing Authority, 484 F. 2d

1122_______________________________________ 37

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F. 2d 1254, certiorari denied, 402

U.S. 944____________________________________ 37

Rios v. Enterprise Association, 501 F. 2d 622---------- 53

Rossetti Contracting Co. v. Brennan, 508 F. 2d 1039_ 34

Simpkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.

2d 959, certiorari denied, 376 U.S. 938___________ 47

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301________ 33

Spring-field School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F. 2d

261________________________________________ 37

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303___________ 37

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1__________________________________ 30

Trafficonte v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Go., 409

U.S. 205____________________________________ 39

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, No. 75-1126,

decided June 16,1977--------------------------------------- 52

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144_____________ 24,32,40,50, 51, 60

United States v. Antelope, No. 75-661, decided April 19,

1977 54

V

Cases—Continued

United, States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa- page

tion, 395 U.S. 225____________________________ 30

Weinberger v. Weisenfeld, 420 U.S. 636------------------- 50

Wheeler v. Barrera, 417 U.S. 402__________________ 23

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356________________ 47

Constitution, statutes, and regulations:

United States Constitution:

Thirteenth Amendment_____________________ 37

Fourteenth Amendment________________ 17,18,51,52

Fifteenth Amendment_______________ *______ 37

Civil Eights Act of 1964:

Title IV, 78 Stat. 248, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6_______ 3

Title VI, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq____ 34

42 U.S.C. 2000d____________ ____________ 3

42 U.S.C. 2000d - l___ ______ ____________ 35-

Title V II, 78 Stat. 253, as amended by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 86 Stat.

103, 42 U.S.C. (and Supp. V) 2000e et seq.:

Section 703 (j ), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (j ) _______ 53

Section 715, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e-14— 36

Title IX , 78 Stat. 266, 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2_______ 3

Civil Eights of 1974, 86 Stat. I l l , Section 715, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 2000e~14___ ______ 36

Emergency School Aid Act, 86 Stat. 354, as amended,

20, U.S.C. (Supp. V) 1601 et seq________________ 43

Public Works Employment Act of 1977, Pub. L. 95-28,

91 Stat, 116-117-____________________ ________ 2,33

42 U.S.C. 1981_______________________________... 52

42 U.S.C. 3766(b)________________ 53

41 C.F.E, 60-2.10______________________________ 34

45 C.F.E. Part 80— _________ _________________ 35

45 C.F.E. 80.3(b) (6) (i-i)____________ ___________ 2,35

45 C.F.E. 80.5( j)_______________________________ 35

Miscellaneous:

AAMC, Medical School Admission Requirements 1978-

1979 (1977)— ——.___________________________

Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical

School Admission Requirements 1978-1979 (1977)— 48,49

Brest, The Supreme Court, 1975 Term, Forward: In

Defense of the Antidiscrimination Principle, 90

Harv. Law Eev. (1976)_______________________ 60

VI

Miscellaneous—Continued

Carroll, A 0 omparative Analysis of Three Admission/

Selection Procedures (It.E.W. Technical Paper 77- page

D4) (1977)---------------------------------------------------- 66

Comment, The Philadelphia, Plan: A Study on the

Dynamics of Executive Power, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev.

732 (1972)_________________________________ 34

122 Cong. Rec. Sl.7320 (daily ed., September 30,1976) _ 53

123 Cong. Rec. II1430-II 1*137 (daily ed., February 24,

1977) --------------------------------------------------- _____ 33

123 Cong. Rec. H6099-H6106 (daily ed., June 17,

1977) ----------------------------------------------------------- 34

Curtis, Blacks, Medical Schools, and Society (1971)_45,48

Dube, Datagram,: TJ.S. Medical Student Enrollment,

1968-1969 Through 1972-1973, 48 J. Med. Educ. 293

(1973) -------------------------------------------------------- 46,47

Dube, Datagram: U.S. Medical Student Enrollment,

1972-1973 Through 1976-1977, 52 J. Med. Educ. 164

(1977) _______________________________ 47

Executive Order 11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 12319, as amended

by Executive Order 11375, 32 Fed. Reg. 14303___ 2, 33, 34

41 Fed. Reg. 38814-38815____________ ___________ 2, 36

Gordon, Descriptive Study of Medical School Appli

cants, 1975-1976 (1977)_________ ____ _________ 47

Greenawalt, Judicial Scrutiny of “Benign” Racial

Preference in Law School Admissions, 75 Colum. L.

Rev. 559 (1975)______ 51

Haug and Martin, Foreign Medical Graduates in the

United States, 1970 (1971)_____________________ 46-47

Johnson, Smith and Tarnoff, Recruitment and. Prog

ress of Minority Medical School Entrants 1970-1972,

50 J. Med. Educ. 713 (1975 Supp.)____ _____ ___48,49

Kaplan, Equal Justice in A n Unequal World: Equality

for the Negro—The Problem, of Special Treatment,

61 Nff. U. L. Rev. 363 (1966)__________________ 51

Melton, The Negro Physician, 43 J. Med. Educ. 802

(1968) ____________________ __________________ 47,48

Morals, The History of the Negro in Medicine

(1967) _______________________________ 44,45,47,48

Murray, States' Laws on Race and Color (1951)_____ 44

Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine (1977)_______ 49

VII

Miscellaneous—Continued

O’Neil, Preferential Admissions: Equalizing the Ac

cess of Minority Groups to Higher Education, 80 pag9

Yale L. J. 699 (1974)_________________________ 51

Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs for

State and Local Government Agencies, 41 Fed. Reg.

38811 ________________________________ 2

Reitzes, Negroes and Medicine (1958)_____ 45

Report of the Task Force to the Inter-Association

Committee on Expanding Educational Opportu

nities in Medicine for Blacks and Other Minority

Students (1970)_____________________________ 49

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census, Yol. I, Char

acteristics of the Population (1973):

California (Part 6)______________________ 4,43,70

United States Summary_______________ 41,42,45,46

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Re

ports, Persons of Spanish Origin in the United

States: March 1976___________________________ 42

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Re

ports, The Social and Economic Status of the Black

Population in the United States 197Jj (1975)______ 42

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census, Subject Re-

. ports'- Final Report PC(2)-7A, Occupational Char

acteristics; Final Report PC (2)AC, Persons of

Spanish Origin (1973)________________________ 46

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Subject Reports-Japanese,

Chinese, and Filipinos in the United States_______ 42

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare,

Office of Health Resources Opportunity, Identifica

tion of Problems in Access to Health, Services and

Health Careers for Asian Americans (1976)______ 46

Waldman, Economic and Racial Disadvantage as Re

flected in Traditional Medical School Selection Fac

tors : A Study of 1976 Applicants to U.S. Medical

Schools (1977)____________ _________________ 43

Wellington and GyOrffy, Draft Report of Survey and

Evaluation of Equal Educational Opportunity in

Health Profession Schools:

Table I I (1975)__________ ________________ 49

Table V III__________ ________ ____________1 49, 50

Jfit tht ih WnW states

October T erm , 1977

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of t h e U niversity of California ,

PETITIONER

V.

A llan B ajcke

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPMERE COURT

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

QUESTIONS PR ESEN TED

1. Whether a state university admissions program

may take race into account to remedy the effects of

societal discrimination.

2. If so, whether, as applied to respondent, peti

tioner’s admissions process operated in a constitution

ally permissible manner.

IN T E R E ST OP T H E U N IT E D STATES

Congress and the Executive Branch have concluded

that race must sometimes be taken into account in

order to achieve the goal of equal opportunity. They

have adopted numerous minority-sensitive programs,

(i)

2

which are collected in Appendix A to this brief. They

also have established several programs to assist per

sons handicapped by their language background (see

Appendix B to this brief). For example, the Depart

ment of Commerce provides technical and financial

assistance to promote enterprises owned by members

of minority groups, and the Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare provides financial assistance

to help colleges and universities increase the number

of minority faculty, students, and investigators en

gaged in biomedical research. The Public Works Em

ployment Act of 1977 provides that applicants for

public works grants must give assurances that at least

ten percent of each grant will be expended “for mi

nority business enterprises” (Pub. L. 95-28, 91 Stat.

116, 117). Moreover, pursuant to Executive Order

11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 12319, as amended by Executive

Order 11375, 32 Fed. Reg. 14303, enterprises holding

federal contracts must take affirmative action to cor

rect disproportionately low employment of racial mi

norities. These and other programs might be affected

by the Court’s disposition of this ease.

The United States has concluded that voluntary ef

forts to increase the participation of racial minorities

in activities throughout our society that were form

erly closed to them should be encouraged. See the

Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs for

State and Local Government Agencies, 41 Fed. Reg.

38814. The United States also encourages appropriate

minority-sensitive efforts in programs supported by

federal funds (see, e.g., 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (ii)).

3

Moreover, several departments and agencies of the

Executive Branch have the responsibility to enforce

legislation passed by Congress to protect persons from

unlawful discrimination on account of race. For ex

ample, the Attorney General may intervene in actions

of general public importance involving assertions of

racial discrimination; he may also sue upon a claim

that any person has been denied admission to a public

college because of race, and he may bring suit to

prevent racial discrimination in federally-assisted

programs. See the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

248, 252, 266, 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6, 2000d and 2000h-2.

The Court’s decision in this ease could affect that en

forcement responsibility.1

The United States is committed to achieving equal

opportunity and preventing racial discrimination.

.For the reasons discussed in this brief it has con

cluded that the achievement of both goals can be at

tained by the use of properly designed minority-

sensitive programs that help to overcome the effects

of years of discrimination against certain racial and

ethnic minorities in America.

STATEM ENT

A. FACTS

The Medical School of the University of California

at Davis opened in 1968. The entering classes of that

year and of the following year included one Chicano,

two black, and 14 Asian-American students out of a

1 Respondent’s claim was based in part upon Section 2000d.

4

total of 100 (R. 215-216).2 This proportion compared

unfavorably with the aggregate proportion of these

three groups to the general population of California—

25.7 percent.3

In 1969 the faculty of the Medical School adopted

a resolution establishing a special admissions pro

gram for disadvantaged applicants (R. 216). Under

that program, sometimes called the “task force” pro

gram, between 1970 and 1974 the school admitted

71 minority persons: 26 blacks, 33 Chieanos and 12

Asian-Americans (R. 216-218). An additional 49

minority persons, including 41 Asian-Americans, were

admitted through the regular admissions process dur

ing those years (R. 216-218). Of the 451 students

entering between 1970 and 1974, 120 (or 26.6 per

cent) were members of minority groups.

On June 20, 1974, respondent brought suit in Cali

fornia Superior Court alleging that as a result of the

special admissions program the Medical School had,

in 1973 and 1974,4 denied him admission solely be-

2 “R.” refers to the record that has been filed with the Clerk of

this Court.

3 U.S. Bureau of Census, 1970 Census, Yol. I, Characteristics of

the Population, California, Part 6, p. 6-387 (1973). The percent

ages of the population are: persons of Spanish language or sur

names, 14.7 percent; blacks, 7.0 percent; Asian-Americans (per

sons of Japanese, Chinese or Filipino descent), 2.65 percent.

American Indians made up 0.45 percent of the California popula

tion in 1970. Spanish language or surnamed persons may be of any

race. For computation purposes Spanish-speaking or surnamed

persons are assumed to be white.

4 We refer throughout this brief to medical school classes by the

year in which the class entered. Applications for an entering class

are received beginning in July of the year before the one in which

the class will enter (R. 150).

5

cause of his race. He sought declaratory relief and

an order to compel his admission (App. 1-4). The

defendants filed a cross-complaint, seeking a declara

tion that the special admissions program was lawful

(App. 9-11).

Counsel agreed to dispense with an evidentiary

hearing and to submit the ease to the court on the

facts set out in the pleadings and in the declaration

and deposition (with exhibits) of George H. Lowrey,

Chairman of the Admissions Committee and Associate

Dean of Student Affairs at Davis (R. 282).

1. T H E REGULAR ADMISSIONS PROCESS

The admissions committee at the medical school

is composed of faculty and students chosen by the

Dean of the school (R. 62, 148-149). Several fac

ulty members screen each application to determine

whether an applicant shows sufficient promise to be

invited for an interview (R. 62, 150). An interview

is a necessary step in the application process; no

one is admitted without being interviewed. No ap

plicant in the regular program with a grade point

average below 2.5 is interviewed (R. 63, 151).5 Al

though other factors are considered in deciding who

is interviewed, there are no written standards (R.

151). Interviews are conducted by one faculty mem

ber of the admissions committee and, since 1974, one

student member. The interviewers write summaries

evaluating each applicant’s potential contribution to

5 Although it is not made explicit, it appears from the record

that grade point averages are scaled from 0.0 to 4.0 (E. 68).

6

the medical profession. On the basis of the file (in

cluding grades and test scores) and interview sum

maries, the interviewers and four other committee

members each rate each applicant on a scale of 0 to

100 (R. 155-159).

All committee members attend an orientation ses

sion in which they discuss the importance of various

factors, including the basic requirements for admis

sion, the depth of study in science and the humanities,

the quality of undergraduate training, and personal

information including letters of recommendation,

extracurricular activities, personal comments and

career plans (R. 62).6 Each numerical rating (also

called a “benchmark score”) is a subjective evaluation

of the applicant’s potential contribution to the medi

cal profession, and the rating is intended to reflect

all of the salient factors, including not only those

mentioned above but also character, motivation, con

templated type of practice, and contemplated location

of practice (R. 64-65, 180).7 Committee members also

consider objective criteria such as college grade point

average and scores on the Medical College Admission

Test (MCAT), a four-part standardized test taken

by medical school applicants, in the course of evaluat-

6 The record does not reveal whether there are written guidelines

for evaluating the applicants.

7 The record indicates that some preference is given to appli

cants who are from (and expi*ess an interest in returning to prac

tice in) areas of northern California that are in need of physicians;

preference is also given to spouses of accepted applicants (It. 64-65,

183). The record does not indicate what weight these factors carry

in the selection process.

7

ing each applicant and assigning a benchmark score

(R. 152). The record does not indicate the relative

weight of these factors in the selection process.

The combined numerical rating is the “major

factor” in selection, but it is not rigidly followed

(R. 63, 182-183). Because acceptance letters are

sent periodically, a rating that will warrant admis

sion early in the selection process may not do so

later (R. 64). In addition, there are two situations in

which an applicant with a lower numerical rating

may be chosen over one with a higher score. First, a

file may be updated with information received after

the rating is made. The decision to “accept people

out of the order of their numerical rating” because of

added information is made by the full admissions

committee (R. 64, 182-183). Second, a list of those

whose scores are “very close to admission” is created

to fill places that may be available because of an

unexpectedly low rate of acceptance by those offered

admission, or because of attrition; the Dean of Ad

missions selects from this list those whom he believes

will bring “ special skills or balance” to the class (R.

64). See Pet. App. 8a.

2 . T H E SPECIAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM

Sixteen percent of the places in each class are

reserved for applicants admitted through the special

admissions program.8 The special admissions pro-

8 Before 1971 the entering class was 52, and eight places were

earmarked for the special admissions program; in 1971 the enter

ing class was increased to 100, and the special admissions program

to 16 (R. 164,215).

8

gram is administered primarily by a special admis

sions committee, comprised principally of faculty and

students who are members of minority groups (R.

161-163, 165, 169, 251-252). Applicants referred to

the special admissions committee could be inter

viewed even though their grade point averages would

not have justified interviews by the regular commit

tee (R. 175). The special admissions committee

selected applicants that, in its view, should be ad

mitted, and it referred their files to the regular ad

missions committee, which made the final admission

decision (R. 165).

Although there is some evidence that the 16 slots

earmarked for special admissions could be varied

when that was justified by unexpected circumstances,9

Dr. Lowrey stated that the special admissions com

mittee “ would continue to approve and process Task

Force applications until 16 had been accepted” (R..

168). The trial court found that 16 places were re

served for minority applicants (Pet. App. 114a-

115a), and the University did not challenge that

finding on appeal (id. at 2a n. 1, lO a-lla).

9 Only 15 places were filled from the special admissions program

in 1971 and in 1974 (Mi. 217-218). Petitioner explains (Br. 3-4.

n. 5) that in 1974 one person admitted through the special admis

sions program withdrew after he had accepted the offer of admis

sion, and that this place was filled by an applicant to the regular

admissions program even though there was a special admissions

waiting list.

9

a. Racial composition of applicants and students

The record includes the following corrected sta

tistics regarding regular and special admissions (R.

214-215, 216-218, 205, 207, 219) :

Referred

Total to special Interviews Offers Matriculations

appli- commit------------------------- ------------------------ —--------------------

Entering class cants tee Total Special Total Special Total Special

1968_______ 564 — — 104 — 48 —

1969-................ 1,038 — — 99 — 52 —

1970 ______ 1,338 104 — 80 — 52 8

1971 ..... 2,433 146 — 160 — 100 15

1972 ...... .............. 1 2,046 169 628 64 192 — 100 16

1973 ..................... 2,464 2 297 886 71 s 185 * 20 * 100 16

1974......................... 3,737 628 550 88 157 26 99 * 16

1 This figure is reported as 2,050 as of May 8,1973 (R. 207).

2 This figure is reported as 291 as of May 8, 1973 (R. 205).

3 This figure is reported as 162 as of May 8, 1973 (R. 207).

4 This figure is reported as of May 8,1973 (R. 205). Dr. Lowrey indicated that there were 32 special

admissions offers (R. 69), and this may reflect later data.

5 But see note 9, supra.

The racial composition of students enrolled in the

Medical School was (R. 174, 216-218) :

Applications referred to Race of regular admittees

special committee —--------------------------------------

— ------------------------------ Asian-

Entering class Total Minority Black Chicano American

1968 __ — 122 — — 3

1969 ...................................... — 1 34 2 1 11

1970—..............___..................... 104 104 0 0 4

1971 ............................ 146 140 1 0 8

1972 .............................................. 169 148 0 0 11

1973 ........................................... 297 224 0 2 13

1974 .................................... 628 456 0 4 2 5

Race of special admittees

Minority admittees — -------------------------------------

.—.---------------------------— Asian-

Entering class Total Special Black Chicano American

1968........................................... 3 — — — —

1969................. !4 — — — —

1970.................................... 12 8 5 3 —

1971........ 24 15 4 9 2

1972....... 27 16 5 6 5

1973-.............. 31 16 6 8 2

1974....................................... . 3 26 * 16 6 7 3

1 These figures represent minority applicants prior to institution of the special admissions program.

2 One American Indian was also admitted through the regular process in 1974 (R. 218).

8 The document in the record indicates 25 but appears to reflect an error in addition (R. 218).

* Petitioner contends that there were only 15 special admittees in 1974. See note 9, supra.

245-950— 77------2

10

b. Eligibility for the special admissions program

Each applicant’s interest in the special admissions

program is initially ascertained from his application

for admission. The 1973 application form asked each

applicant whether he wished to be considered by a

special admissions subcommittee for applicants from

“economically and educationally disadvantaged back

grounds” (R. 232). In 1974 Davis began using a

nationwide application processing service, whose

standard application asked whether the applicant

wished to be considered as a “minority group appli

cant” (R. 65, 197).10 Only those who responded affirm

atively were referred to the special admissions com

mittee (R. 65, 171). In 1974 applicants were not asked

whether they wished to be considered for a program

for the disadvantaged (R. 197). Applications of

whites, blacks, Chicanos, American Indians and Asian-

Americans were referred to the special admissions

committee (R. 65, 216-218).

The special admissions program is open only to

those who are considered disadvantaged, a deter

mination made by the chairman of the special ad

missions committee. The chairman makes this deci

sion on the basis of the application, which reveals

whether the applicant was granted a waiver of appli-

10 The term “minority” was not defined. A separate question on

the application listed the following categories, in addition to white,

under the question “How do you describe yourself?” : Black/Afro-

American, American Indian, Mexican-American or Chicano,

Oriental/Asian-American, Puerto Rican (Mainland), Puerto

Rican (Commonwealth), Cuban, Other (R. 197).

11

cation fee, was a participant in an educational oppor

tunity program in college, worked during under

graduate years or interrupted his or her education

to support himself or herself or family members,

and the occupation and educational level of the appli

cant’s parents (R. 65). Applicants from minority

backgrounds who are not considered disadvantaged

are referred to the regular admissions process

(R. 66) A

Dr. Lowrey stated that the program was open to

all disadvantaged applicants, but that membership

in a minority racial group was considered “as an

element which bears on economic or educational dep

rivation” (R. 65-66). I t is not clear what weight

race is given in the determination that a person is or

is not disadvantaged. Counsel for the Medical School

stated (Pet. App. 92a) that “minority status is * * *

considered as one factor in determining a disadvan

taged status,” but Dr. Lowrey explained that “ [i]n

choosing among the disadvantaged applicants favor

able weight is given to minority group membership in

determining relative disadvantage because minority

applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds labor

under special handicaps in American society” (R. 67).

Written material distributed about the program

characterizes it as one for disadvantaged students

11 See the tables at page 9, supra, which show that after 4l«r^

the special admissions program began many members of minority

groups were also admitted through the regular admissions process.

Of the 380 entering students so admitted, 41 (10.8 percent) were

Asian-Americans, 6 (1.6 percent) were Chicanos, 1 (0.3 percent)

was black, and 1 (0.3 percent) was American Indian.

12

and does not mention racial considerations (R. 65,

195, 196, 248). Although many non-minority per

sons applied for the program (R. 65, 216-218), every

person admitted through it for the classes of 1970

to 1974 was black, Chieano, or Asian-American (R.

216-218). The record does not indicate whether any

whites were interviewed or offered admission. The

trial court found that no white applicant had ever

been admitted through the program and that (Pet,

App. 115a) “ [i]n practice this special admissions

program is open only to members of minority races

and members of the white race are barred from par

ticipation therein.”

c. The process of selection

A special admissions committee, composed of stu

dents and faculty the majority of whom, in 1973,

were from ethnic minorities (R. 162-163, 169, 251-

252), considers each application.12 The special admis

sions committee reviews applications in the same

manner as the regular admissions committee and as

signs a numerical rating to each applicant (R. 66) .13

12 The Supreme Court of California stated (Pet, App. 6a) that

the special admissions committee “consists of students who are all

members of minority groups, and faculty of the medical school

who ai*e predominantly but not entirely minorities.” Faculty mem

bers of the special admissions committee also were members of

the regular admissions committee (R, 196), although they served

primarily on the special committee (R. 162,168).

13 Members of the special admissions committee were given no

formal instructions on selection of students (R. 163), but they

were given a statement on the purposes of the program (R. 163,

196).

13

The chairman of the special admissions committee

screens the applications to determine who will be

invited for an interview (R. 66). The record does

not disclose what criteria the chairman uses in mak

ing this decision, but applicants with grade point

averages lower than 2.5 are not automatically elimi

nated (R. 175), and some have been admitted (R. 210,

223).14

At appropriate intervals the chairman of the spe

cial admissions committee refers several of the “most

promising” special admissions applicants to the regu

lar admissions committee with recommendations that

they be admitted; the regular admissions committee

reviews the applicants and determines whether to ac

cept the special committee’s recommendations (R.

66-67, 165-166). The regular admissions committee

has in some cases rejected recommendations (R. 166-

167).

The trial court found that (Pet. App. 115a) “ [ a p

plicants in the special admissions program are rated

for admission purposes only against other applicants

in this program and not against applicants under the

general admissions program.” 15 That finding was not

challenged on appeal, but the record does not indicate

14 In 1972, 37.9 percent of special applicants were interviewed,

•compared with 30.0 percent of regular applicants. In 1973 the

figures were 23.9 percent (special) and 37.6 percent (reg

ular) ; in 1974 they were 14 percent (special) and 14.9 percent

(regular) (see page 9, supra).

lo I t is not clear whether the court was referring to assignment

of a numerical rating or comparative evaluation of applicants

after ratings are assigned.

14

whether special applicants are compared with regular

applicants whose applications are considered at the

same time.

All those admitted are considered by the Medical

School to be qualified to practice medicine and to

contribute to the school and the medical profession.

Dr. Lowrey stated (R. 67):

Every admittee to the Davis Medical School,

whether admitted under the regular admissions

program or the special admissions program,

is fully qualified for admission and will, in the

opinion of the Admissions Committee, contrib

ute to the School and the profession.

d. Purpose of the program

Dr. Lowrey stated that it was the judgment of the

faculty that (R. 67) :

the special admissions program is the only

method whereby the school can produce a di

verse student body which will include quali

fied students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Dr. Lowrey believed that without the program there

would be few disadvantaged minority students at Da

vis (R. 67-68).16

Dr. Lowrey gave several reasons why the faculty

had instituted the program: (1) the paucity of minor

ity persons in the medical profession; (2) the bene

fits to students and physicians of achieving diversity

in the student body and the profession through ad

mission of minority applicants; (3) the need to train

These statements were not challenged or refuted by

respondent.

15

minority physicians who would serve the needs of

disadvantaged minority communities by working in

those communities and would encourage non-minor

ity physicians to do so also;17 (4) the need to train

physicians who would serve as examples to encourage

younger persons from minority backgrounds to aspire

to professional careers; and (5) the need to give

special consideration to minority applicants because,

as a result of poor education, economic burdens, and

lack of family support, test scores and grades do

not necessarily reflect their abilities (R. 67-69).

3. r e s p o n d e n t ’s a p p l i c a t i o n

Respondent applied to Davis for the classes begin

ning 1973 and 1974 (R. 231, 236). He did not request

consideration in either year as a disadvantaged appli

cant (R. 232, 236). He was granted an interview in

both years (R. 69).

In 1973 the admissions committee gave respondent

a “ benchmark” rating of 468 (R. 179-180),18 and he

was comparatively high among regular applicants

(R. 180).19 Respondent’s application was received late

in the admissions process, however, and he was not

interviewed until after a majority of the positions in

the class (and 12 special admissions positions) had

17 Every applicant admitted through the special admissions pro

gram has expressed an interest in practicing in a disadvantaged

community (K. 68). I t is not clear whether respondent expressed

such an interest (It. 228).

18 The maximum possible rating that year was 500.

19 The record contains the following information regarding

grade point averages and MCAT scores(R. 189-190, 210, 223) :

1 6

been filled (R. 64, 69-70). Dr. Lowrey recalled that

regular admittees had ratings as low as 452. He stated

that the “ average” rating of special admittees was

probably 10 to 30 points below respondent’s, but that

the overall “range * * * [was] comparable” to that

of regular admittees (R. 181).20

The defendants initially contended in the trial court

and on appeal that the special program did not cause

respondent’s rejection in 1973 because most of the

places had been filled by the time his application was

ready to be considered, and the remaining places

would have gone to those with higher scores and to

those on the list of alternates, which did not include

respondent (R. 69-70).

Science Overall MCAT MCAT

grade grade verbal science

point point score1 score1

average average (percentile) (percentile)

Respondent.......... .............. ...................... - 3.45 3.51

Mean Scores

1973 Entering Class:

Regular Admittees........................ - ........ 3.51 3.49 81 83

Special Admittees_____________ 2.62 2.88 46 35

1974 Entering Class:

Regular Admittees................... 3.36 3.29 69 82

Special Admittees......... ......................... 2.42 2.62 34 37

Ranges

1973:

Regular Admittees.................................. 2.57-4.0 2.81-3.99

Special Admittees.............. ...................- 2.11-2.93 2.11-3,76

1974:

Regular Admittees................................... 2.5-4.0 2.79-4.0

Special Admittees......... —....................... 2.02-3.89 2.21-3.45

i Verbal and science scores are considered more significant than scores on the quantitative and

general information portions of the MCAT exam (R.152,153).

20 No other evidence establishes the numerical ratings of reg

ular or special admittees (B,. 181-182).

17

In 1974 respondent made an early application and

was interviewed early (R. 70-71). His rating of 549

on a scale with a maximum of 600 was equivalent to

that in 1973, but there were more applicants with

higher scores ahead of him (ibid.\21 Respondent was

rejected not only by Davis hut also by 12 other me

dical schools (R. 49-50, 51) .22

B. THE STATE COURTS' OPINIONS

1. T H E SUPERIOR COURT

The Superior Court found (Pet. App. 114a-115a)

that the special admissions program was not open to

white applicants, and it concluded that their exclu

sion from competition for 16 of the 100 places at the

Medical School violated the California Constitution

and the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States

Constitution {id. at 107a, 117a). The court reasoned

that any program using race was arbitrary and un

fair, and it did not, discuss the justifications that had

been offered in support of the program.

The court entered a declaration that the special

admissions program was unconstitutional and en

joined petitioner from “considering [respondent’s]

race or the race of any other applicant in passing upon

his application for admission” (Pet. App. 120a). It

denied respondent’s request to be admitted to the

Medical School because it concluded that respondent

21 His 1973 rating was 93.6 percent of the maximum; his 1974

rating was 91.5 percent of the maximum.

22 Bakke was informed by two schools that his age—33 in 1973—

played a part in his rejection (E. 49-50,52).

18

had not carried his burden of establishing that, but

for the Medical School’s use of race, he would have

been admitted (id. at 107a-108a, 111a, 116a-117a).

2 . T H E SUPREM E COURT OP CALIFORNIA

Both petitioner and respondent appealeds Peti

tioner challenged the Superior Court’s holding and

declaratory judgment that the special admissions pro

gram is unconstitutional; respondent contested the

court’s holding that he should be denied relief because

he failed to prove that he would have been admitted

if the 16 places had not been reserved for minority

applicants.

The Supreme Court of California agreed to hear

the case in advance of decision by the intermediate

appellate court (Pet. App. 4a). I t affirmed the

Superior Court’s decision that the special admissions

program is unconstitutional, but in so doing it relied

only on the Fourteenth Amendment.

After describing the admissions process at the Med

ical. School, the Supreme Court of California observed

that racial classifications may sometimes be constitu

tionally employed—for example, in assigning students

to public schools to achieve integration (Pet. App.

13a). The court concluded, however, that the use of

race by the Medical School must be judged by es

pecially rigorous standards because “the extension of

a right or benefit to a minority [had] the effect of

depriving persons who were not members of a minor

ity group of benefits which they would otherwise have

enjoyed” (ibid.). When race is used to assign a stu-

19

dent to one school rather than to another to eradicate

the effects of previous discrimination, all students

still receive an education, and whites and minority

students alike share the burden of transportation {id.

at 13a-14a) ; the consequences of the use of race are

quite different, the court reasoned, where there is com

petition for a limited number of places and race is

used as a criterion of exclusion. The fact that the use

of race therefore might treat minorities “benignly”

did not obviate the need for exacting judicial scru

tiny.23

The court characterized the central issue of the

case as “whether the rejection of better qualified

applicants on racial grounds is constitutional” (Pet.

App. 16a). Applying the “strict scrutiny” test for

racial classifications that “result in detriment to a

person because of his race” {id. at 17a, footnote

omitted), the court examined petitioner’s justifica

tions for the special admissions program at Davis.24

23 Quoting from DeFuni-s v. Odegaard, 82 Wash. 2d 11,32,507 P.

2d 1169, 1182, vacated as moot, 416 U.S. 312, the court observed

that “ ‘the minority admissions policy is certainly not benign

with respect to nonminority students who are displaced by it’ ”

(Pet. App. 17a n. 12).

24 The court rejected (Pet. App. 18a-19a) the argument that

less exacting scrutiny should be applied because the use of race

cut in favor of traditionally disadvantaged groups. The court

stated {id. at 19a n. 16) that no discernible majority was dis

criminating against itself, and it reasoned that the Equal Protec

tion Clause protects persons as persons, not only as members of

racial groups {id. at 20a). Thus, the court concluded, respondent

had a personal right not to suffer loss because of his race, and

it did not matter whether he was a member of a minority racial

or ethnic group.

20

I t summarized four justifications that had been

offered in support of the special admissions program

(Pet. App. 21a-22a) : the desire to increase the racial

diversity of the medical profession and the student

body; the need to train minority physicians who would

serve as role models for other members of minority

groups; the need to increase the number of physicians

serving minority communities; and the belief that

minority physicians would have greater rapport with

minority patients and consequently be more effective.

I t rejected (Pet. App. 23a) arguments about rap

port and the need for minority physicians to serve

minority patients, on the grounds that they were

unsupported, parochial and relied on racial stereo

types. Although the court stated that the remain

ing objectives were legitimate and important, it con

cluded that the Medical School had not demonstrated

that these objectives could not be achieved by other

mean (ibid.). The court suggested (id. at 24a-26a)

that the Medical School might increase the size of

its classes, reduce its reliance on grades in selecting

from among disadvantaged students of all races, and

increase its efforts to recruit disadvantaged students.

The court also suggested (id. at 28a) that the Medical

School could give a preference to applicants of any |

race who expressed willingness to practice in disad

vantaged communities, and that it could institute

clinical courses to induce students to do so. Because,

“■[s]o far as the record discloses, the University has

not considered the adoption of these or other nonracial

21

alternatives to the special admission program” {id. at

26a), the court concluded that the Medical School had

not established a compelling need for the special ad

missions program.

The court distinguished a line of eases that had

upheld race-conscious relief for employment discrim

ination (Pet. App. 29a-32a). I t found no evidence

that the Medical School had engaged in discrimina

tion, and it declined to consider the argument of

several amici that reliance on grade point averages

and MCAT scores was discriminatory.25

The court also stated that, as a practical matter,

preferences are difficult to abolish even after they have

served their purpose (Pet. App. 36a). I t concluded

that “ [w]hile a program can be damned by semantics,

it is difficult to avoid considering the University

scheme as a form of an education quota system,

benevolent in concept perhaps, but a revival of quotas

nevertheless. * * * To uphold the University would

call for the sacrifice of principle for the sake of dubi

ous expediency and would represent a retreat in the

struggle to assure that each man and woman shall be

judged on the basis of individual merit alone, a strug

gle which has only lately achieved success in removing

legal barriers to racial equality” {id. at 36a-37a).

25 That argument had not been raised in the trial court, and

nothing in the record either supports or refutes the argument that

grades and MCAT scores are insufficiently related to performance

in medical school or in the profession, or that the MCAT is cul

turally biased (Pet. App. 31a-32a).

22

Turning to respondent’s appeal from the decision

denying him admission to the Medical School, the

court concluded that the Medical School, not respond

ent, should bear the burden of proof (Pet. App. 37a-

39a). I t therefore remanded the case for further pro

ceedings at which the Medical School would be re

quired to establish, if it could, that even in the absence

of the unconstitutional program respondent would

have been denied admission.26 After the Medical School

conceded that it would be unable to meet that burden

of proof, the court modified its opinion and judgment

to provide that respondent must be admitted (id. at

80 a).

Justice Tobriner dissented (Pet. App. 39a-78a).

He stated that (id. at 60a-61a; footnote omitted) :

“ [heightened judicial scrutiny is * * * appropriate

when reviewing laws embodying invidious racial

classifications, because the political process affords an

inadequate check on discrimination against ‘discrete

and insular minorities.’ * * * By the same token,

however, such stringent judicial review is not appro

priate when, as here, racial classifications are utilized

remedially to benefit such minorities, for under such

circumstances the normal political process can be

relied on to protect the majority who may be incident

ally injured by the classification scheme.” Applying

that standard, he would have held that the special

admissions program did not offend the Constitution.

26 The court indicated that its decision would apply retroactively

only to applicants who had filed suit before the date of its opinion

(Pet. App. 38a n. 34).

23

IN TRO DU CTION AND SUM M ARY OF ARGUM ENT

This case involves a special admissions program

that takes race into account. The parties have por

trayed the case as an appropriate vehicle for definitive

resolution of numerous constitutional questions that

may arise with respect to minority-sensitive programs.

But deficiencies in the record of this case make it

inappropriate for the Court to anticipate these ques

tions. In our view, only one question should be finally

resolved in the present posture of this case: whether

a state university admissions program may take race

into account to remedy the effects of societal discrim

ination. We submit that it may.

The record does not afford an adequate basis for

the exploration of other questions (cf. Morales v.

New York, 396 U.S. 102). I t is enough to say that

the opinion of the Supreme Court of California ap

plied an erroneous legal standard. At all events the

present record is plainly insufficient to permit the

formulation of detailed principles that would deter

mine the constitutionality of the many other federal

and state programs that take race into account in

various ways and for various purposes. We believe

that the Court’s decision should leave for consider

ation in cases dealing with other specific programs, on

a proper record, specific questions that may arise

concerning those programs. Cf. Wheeler v. Barrera,

417 U.S. 402, 426-427.

24

I

Within the confines of this ease, we examine the

justification for minority-sensitive programs and the

constitutionality of taking race into account in mak

ing decisions concerning admissions to professional

school. The most important principle involved here is

that because the effects of racial discrimination are

not easily eliminated, mere neutrality toward race

often is inadequate to rectify what has gone before.

The Court therefore has upheld on many occasions

remedial orders that require the government to use

race to assist in the remedial process. As the Court

explained in North Carolina State Board of Education

v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43, 46, “ [jjust as the race of stu

dents must be considered in determining whether a

constitutional violation has occurred, so also must it

be considered in formulating a remedy.”

This principle extends beyond public rectification

of public wrongs. Race may be considered in devising

remedies for private discrimination. Franks v. Bow

man Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747. Race may be

considered in carrying out a prophylactic program to

prevent racially disadvantageous outcomes, whether

or not they would violate the Constitution. United

Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144. And race may be taken into

account in avoiding racially disproportionate effects

of employment testing practices. Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405.

25

Congress, which has a special responsibility to in

terpret and to enforce the Civil War Amendments,

has determined that minority-sensitive programs are

necessary to rectify the continuing consequences of

discrimination. Many federal programs make explicit

use of race, and the Executive Branch has joined

Congress in endorsing voluntary efforts by States

and private parties to do likewise when necessary

to break down the barriers that have separated the

races for so long.

I I

States and their subdivisions are not limited to ad

dressing only the effects of their own discrimina

tion. Racial discrimination in society as a whole may

make it difficult for a professional school fairly to

evaluate the abilities and promise of minority ap

plicants without taking race into account. Moreover,

this Court has recognized that “substantial benefits

flow to both whites and blacks from interracial as

sociation” (Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of

Willingboro, No. 76-357, decided May 2, 1977, slip op.

10), and those benefits cannot be achieved unless each

institution in society may consider the consequences

of racial discrimination by others. There is no need

for a professional school to await a judicial decision

that it has itself violated principles of equality be

fore it may begin to redress inequality created by

others.

If, as we argue, a professional school may take

into account the likely effects of societal discrimi-

245- 950— 77--------- 3

26

nation in making admissions decisions, it, follows that

the school may employ minority-sensitive admissions

procedures. This Court has witnessed a history of

discrimination against minority groups that does not

require repetition here. That discrimination has af

fected the medical profession no less than other pro

fessions.

I l l

When a State considers race in distributing bene

fits, its program must be examined carefully for two

reasons. First, a racial classification that purports to

be benign—that is, to assist the victims of discrimina

tion-m ay in fact be invidious in purpose or effect.

Second, the State may not take account of race un

less that is necessary to achieve an important govern

mental objective. Race ordinarily ‘‘bears no relation

to the individual’s ability to participate in and con

tribute to society.” Mathews v. Lucas, 427 U.S. 495,

505. The United States has undertaken to foster the

principle that race is unrelated to merit or qualifica

tion and is not generally a legitimate basis for dis

tributing opportunities. To do otherwise would be to

risk reverting to the very thinking that has in the

past resulted in invidious discrimination. The Four

teenth Amendment protects all persons without regard

to their race, and that protection can be assured only

by careful examination of minority-sensitive state

action.

Such an inquiry, however, does not call for the re

jection of minority-sensitive programs that are de-

27

signed to serve remedial purposes and that are tai

lored to that end. The courts’ central concern should

he whether the program is designed and applied to

remedy the effects of past discrimination. Such a de

sign often will require use of race rather than case-

by-case determinations of discrimination.

Societal discrimination may have left minority ap

plicants to professional schools with credentials less,

impressive than they otherwise would have had. Be

cause competition for admission is keen, even small

differences in such credentials may determine whether

applicants will be admitted or rejected. I t is appro

priate to take race into account to adjust for differ

ences in credentials that may have been caused by

discrimination but do not reflect differences in ability

to succeed or in ability to contribute to the medical

profession and the health of the general population..

The admissions process involves many difficult and

subjective decisions. For example, admissions com

mittees often must consider whether grades from

one college are comparable to those from another, or

whether an applicant with higher grades should be*

admitted before one with greater self-discipline. Other

pertinent considerations are no less subjective. Be

cause admissions decisions involve comparisons of in

tangible qualifications, educational institutions require

wide latitude in making these decisions.

Moreover, there is no adequate alternative to the

use of minority-sensitive admissions criteria. The

Supreme Court of California suggested increasing the

28

size of the Medical School’s classes. But whether the

Medical School admits 100, 200, or 500 students, mi

nority applicants still will be handicapped by the con

sequences of prior discrimination. The court also sug

gested replacing consideration of race with special

consideration for disadvantage. At any level of per

sonal or parental income, however, applicants who are

from minority groups face an extra hurdle—-the lin

gering effects of pervasive racial discrimination—that

other applicants do not. Cf. Califano v. Webster, No.

76-457, decided March 21, 1977.

IV

Under the principles we have discussed above, the

judgment of the Supreme Court of California should

be reversed to the extent that it forbids the Medical

School to operate any minority-sensitive admissions

program.

The remaining question is whether respondent is

entitled to admission to the Medical School. We have

argued that it is constitutional in making admissions

decisions to take race into account in order fairly to

compare minority and non-minority applicants, but

it is not clear from the record whether the Medical

School’s program, as applied to respondent in 1973

and 1974, operated in this manner.

The trial court found, and the University does

not contest, that 16 places in the class were reserved

for special admittees. The record does not establish,

however, how this number was chosen, whether the

29

number was inflexible or was used simply as a meas

ure for assessing the program’s operation, and how

the number pertains to the objectives of the special

admissions program.

It also is unclear whether there was any compari

son of minority with non-minority applicants. The

regular admissions committee played some role in the

selection of all 100 students, but the record does not

reveal what that role was. If there was a fair com

parison of regular and special applicants by the reg

ular admissions committee, this would indicate that

race had not been used improperly.

The deficiencies in the evidence and findings—which

pertain to both the details of the program and the

justifications that support it—may have been caused

by the approach both parties, and both courts below,

took to this case. They asked only whether it was

permissible for the Medical School to use race at

all. We believe that it is permissible to make minor

ity-sensitive decisions, but that it is necessary to

address, as well, questions concerning how race was

used, and for what reasons. The findings with respect

to these latter, critical questions are insufficient to

allow the Court to address them.

Accordingly, the judgment of the Supreme Court

of California should be vacated to the extent that,

it orders respondent’s admission, and the case should

be remanded for further appropriate proceedings

to address the questions that remain open. In all other-

respects the judgment should be reversed.

30

A RG UM EN T

I

RACE M AY BE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT TO COUNTERACT

TH E EFFECTS OF PRIOR DISCRIMINATION

A. T H IS COURT HAS HELD TH A T M IN O R ITY -SEN SITIV E DECISION'S ARE

ESSENTIAL TO E LIM IN A TE T H E EFFECTS OF DISCRIM INATIO N IN

T H IS COUNTRY

The effects of racial discrimination are not easily

eliminated. Because discrimination breeds other in

equalities, the Court has recognized that simple elim

ination of future discrimination may well be insuffi

cient to rectify what has gone before. Mere neutral

ity often is inadequate (Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438).27

In United States v. Montgomery County Board of

.‘Education, 395 U.S. 225, the Court upheld an order

that teachers be dispersed on a racial basis throughout

a desegregating school system. In Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 19-25,

the Court explained that the race of students and

.teachers could be taken into account in devising a

remedy for racial discrimination. And in North Caro-

27 See Boston Chapter, N.A.A.C.P., Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F. 2d

1017, 1027 (C.A. 1), certiorari denied, 421 U.S. 910 (“The goal of

color blindness, so important to our society in the long run, does not

mean looking at the world through glasses that see no color; it

means only that all colors are moral equivalents, to be treated

on an equal basis”). Unlike the situation in which the State need

lessly injects race into what might otherwise be a racially-neutral

undertaking (see Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399), once racial

discrimination has taken place it is often necessary to use race

a second time to bring about a neutral result.

31

Una State Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43,

the Court held, that a statute forbidding the assignment

of students on the basis of race was unconstitutional,

because it would hinder the implementation of neces

sary remedies. The Court explained (402 U.S. at 46) :

“Just as the race of students must be considered in

determining whether a constitutional violation has

occurred, so also must race be considered in formu

lating a remedy.” 28

Consideration of race also is necessary in devising

remedies for private discrimination. Franks v. Bow

man Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, held that sen

iority credits could be awarded on a racial basis, and

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, No. 75-636, decided May 31, 1977, amplified

that principle. Both cases, moreover, recognized that

although remedial measures inevitably would upset

the expectations of other persons, most of whom

would be white, this was not a sufficient objection to

the implementation of effective remedies.

Moreover, the remedial use of race has not been

confined to the elimination of discrimination that has

been proven by traditional means. For example, Con

gress concluded that, in order to protect the voting

rights of certain minority groups against subtle dilu-

28 See also Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, No.

76-539, decided June 27, 1977, which indicated once more that

race could be taken into account both in ascertaining the degree

of racial separation caused by the discrimination and in devising

a remedy that would eliminate only that increment, and no more.

Such a procedure necessarily requires extensive use of racial

criteria.

32

tion, it was necessary to consider tlie race of the per

sons who would be affected by legislative reappor

tionments. The prophylactic statute Congress en

acted—the Voting Rights Act of 1965—is about race,

and its administration is perfused with the require

ment of color-consciousness. Race must be taken into

account to prevent racially disadvantageous outcomes,

not simply to rectify past discrimination. This Court

has upheld this use of race. United Jewish Organiza

tions of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 IT.S. 144;

see Georgia v. United States, 411 IT.S. 526, 531 (de

scribing the Act as “concerned with * * * the reality

of changed practices as they affect Negro voters”).

Finally, color-conscious decisions are made regu

larly to implement the Civil Rights Act of 1964. For

example, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 IT.S. 424,

held that Title V II of that Act prohibits the use of

employment tests that have a substantial racially dis

parate effect, unless the employer can prove that

the tests are job related. Even then “it remains open

to the complaining party to show that other tests or

selection devices, without a similarly undesirable ra

cial effect, would also serve the employer’s legitimate

interest in ‘efficient and trustworthy workmanship.’ ’’

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 IT.S. 405, 425.

And in Albemarle Paper, in dealing with a test that

appeared to screen out black applicants for employ

ment at a disproportionately high rate, the Court con

cluded that, in validating such a test as job re

lated, employers could be required to counteract its

racially disparate effects by resorting to racial cri

33

teria. They could, in other words, be required in ap

propriate circumstances to “differentially validate”

their employment tests—to use one passing score

for blacks and another for whites, so that the test

would predict success on the job equally well for both

racial groups. The conscious use of race in making

such employment decisions can help prevent subtle

discrimination and help the employer to achieve a

result that ultimately will not be racially biased.

B. BOTH T H E LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE BRANCHES OP T H E FEDERAL

GOVERNMENT HAVE ADOPTED M IN O RITY -SEN SITIV E PROGRAMS FOR

T H E PURPOSE OF ELIM IN A TIN G T H E EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIM INATION

The use of race is supported by many programs es

tablished by Congress, which has a special responsi

bility for interpreting and enforcing the Civil War

amendments to the Constitution (see South Carolina v.

Katzenhach, 383 U.S. 301, 327). See, e.g., Appendix

A to this brief. Congress has authorized expenditures

for many of these measures, most recently in the Pub

lic Works Employment Act of 1977, Pub. L. 95-28, 91

Stat. 116,117, which requires the dedication of part of

public works grants for minority business enterprises.

Congress adopted this program in order to promote

and strengthen minority-owned businesses. See 123

Cong. Rec. H1436-H1437 (daily ed., February 24,

1977).

Perhaps the most prominent minority-sensitive pro

gram of the federal government is the enforcement of

Executive Order 11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 12319, as

amended, 32 Fed. Reg. 14303. The Executive Order

34

requires federal contractors to take affirmative action

to prevent disproportionately low employment of

women and minorities in their work forces, starting

from the assumption that most disproportionately low

employment is the result of discrimination—if not of

the contractor involved, then of someone else.29 The

constitutionality and legality of this program has

been repeatedly upheld.30

The Executive Branch has devoted extensive efforts

over the past several years to developing minority-

sensitive programs that will address the consequences

of past discrimination. Eor example, Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, as amended, 42

TJ.S.C. 2000d el seq., prohibits racial discrimination in

the operation of federally assisted programs. The Me

dical School, as the receipient of federal assistance

29 Department of Labor regulations require that if there ai’e

disparities between the proportion of available minority workers

and their employment, the employer must establish goals and

timetables for correcting the disparity. 41 C.F.R. 60-2.10,

30 See, e.g., Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F. 2d 159 (C.A. 3), certiorari denied,

404 U.S. 854; Rossetti Contracting Co. v. Brennan, 508 F. 2d 1039

(C.A. 7); Northeast Construction Co. v. Romney, 485 F. 2d 752

(C.A. D.C.). For a history of the Executive Order and the re

sponse to it in Congress and the courts, see Comment, The Phila

delphia Plan: A Study on the Dynamics of Executive Power,

39 U. Chi. L. Rev. 732 (1972).

Moreover, in enacting the 1972 amendments to Title Y II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress considered and rejected the

option of altering Executive Order 11246. The history of this

consideration is recounted in Comment, supra, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev.

at 747-760. The present Congress is again considering the question.

See, e.g., 123 Cong. Rec. I46099-H6106 (daily ed., June 17,1977).

35

(A. 8), is bound by Title VI. The Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, with the approval of

the President, has promulgated regulations that inter

pret the requirements of Title VI.81

These regulations, which are codified at 45 C.F.R.

Part 80, provide that “ [e]ven in the absence of

* * * prior discrimination [by the recipient of fed

eral funds], a recipient in administering a program

may take affirmative action to overcome the effects of

conditions which [result] in limiting participation by

persons of a particular race, color, or national origin”

(45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (ii)). The regulations offer the

following illustration (45 C.F.R. 80.5 ( j) ) :

Even though an applicant or recipient has

never used discriminatory policies, the services

and benefits of the program or activity it ad

ministers may not in fact be equally available?

to some racial or nationality groups. In such

circumstances, an applicant or recipient may

properly give special consideration to race,

color, or national origin to make the benefits of

its program more widely available to such

groups, not then being adequately served. For

example, where a university is not adequately

serving members of a particular racial or

nationality group, it may establish special re

cruitment policies to make its program better

known and more readily available to such

group, and take other steps to provide that

group with more adequate service.

51 Regulations adopted to enforce Title VI require the approval

of the President. 42 TJ.S.C. 2000d-l.

36

The Equal Employment Opportunity Coordinating

Council, a joint body of several federal agencies,’2

lias issued a Statement on Affirmative Action Pro

grams for State and Local Governmental Agencies.33

The Statement encourages state and local govern

ments to adopt affirmative action programs as neces

sary complements of vigorous enforcement of anti-

discrimination laws. The Council concluded that prop

erly-designed minority-sensitive programs are instru

mental in ensuring “that positions * * * are genu

inely and equally accessible to qualified persons, with

out regard to their race * * The Council en

dorsed the establishment of goals that would reduce

“substantial disparities” between the number of quali

fied persons and their acceptance for employment.

I t also concluded that it would be necessary and ap

propriate to take race into account in recruiting,

training programs, and the evaluation of selection

methods.

32 The Council was established by statute to develop and im

plement “agreements, policies and practices designed to * * *

eliminate conflict * * * and inconsistency among' the * * * agen

cies * * * of the Federal Government responsible for the * * *

enforcement of equal employment opportunity * * * policies.”