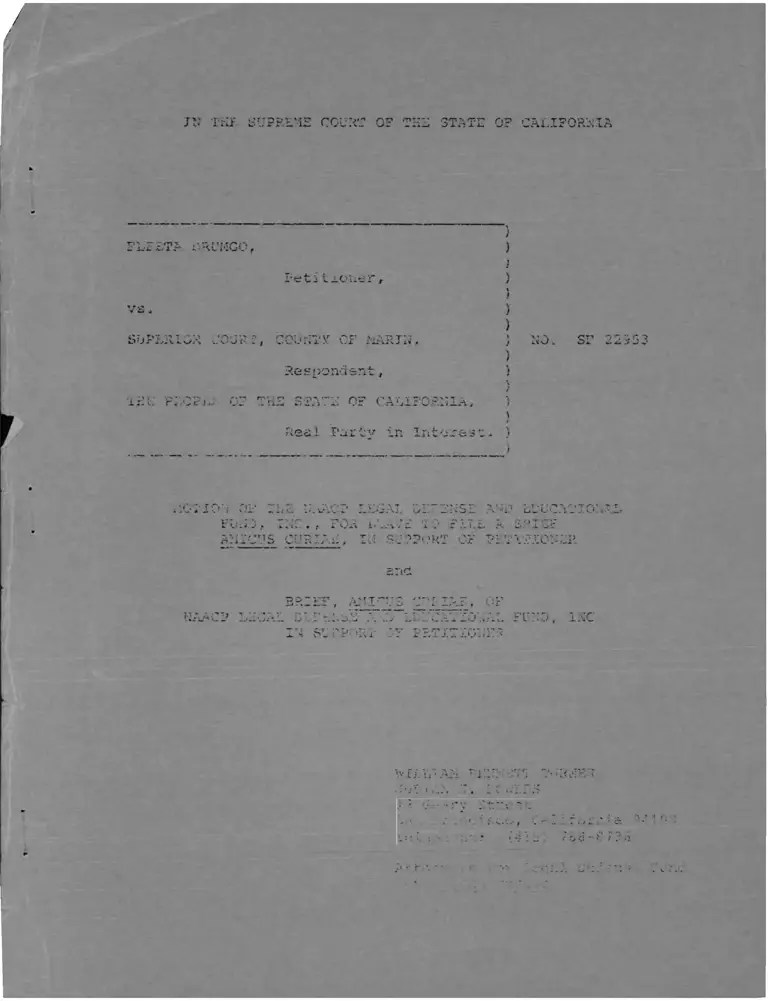

Drumgo v. Marin County Superior Court Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 13, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Drumgo v. Marin County Superior Court Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1972. f6597a43-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d35dfe3e-7263-481c-8278-01b9298a4863/drumgo-v-marin-county-superior-court-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JV THE SUPRE'lE COURT OF THU STATE OF CALIFORNIA

'LLFTA LRUMGO,

VS,

Tetitiouer,

SuFLilLOM. COURT, COUnTT CF LlARTF.

Respondent,

iHL FFOPj,.. OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Real Fartv in Interest.

NO. SF 22953

toe co 1LA.C? LEGAL -IF COST A'-a LUOCATIORAL

t Oi< L • . i . FILL A ELITEAlICTS currah, hi support of peavticlcr

and

BRIEF, ANITVS C'TIAF. OF

UAACP LEGAL ELFoLtCI L .L lLt;CACIOH.-VL FULL, ICC

I'4 ALCPORL IF petittollt

a CRT

... * ..v ;.. . .• ci

/ ?, 8 *• >• ?? 0

■ O' :

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

)

FLEETA DRUMGO, )

)

Petitioner, )

)

vs. ))

SUPERIOR COURT, COUNTY OF MARIN, ) NO. SF 22953

)Respondent, )

)

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, )

)

Real Party in Interest.)

)

MOTION OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF,

AMICUS CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER_____

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(the "Legal Defense Fund") hereby requests leave to file the

annexed brief amicus curiae in support of petitioner Drumgo.

The interest of the Legal Defense Fund as amicus

is fully set forth in the annexed brief. The Legal Defense

Fund seeks leave to file a brief amicus curiae in this

case to emphasize the peculiar and serious problems of

representation of indigent defendants from racial minorities.

-1-

Richard Breiner, Esq., attorney for petitioner,

and Herbert F. Wilkinson, Deputy Attorney General, attorney

for the Real Party in Interest, have consented to the filing

of a brief by amicus.

DATED: October 13, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

JULIAN J. FOWLES

Attorneys for Legal Defense Fund

as amicus curiae

-2-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen

v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1 (1964) 7

Brown v. Craven, 424 F.2d 1166

(9th Cir. 1970) 8

Carmical v. Craven, 457 F.2d 582

(9th Cir. 1971) 6

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964) 6

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) 7

People v. Butcher, 275 Cal.App.2d 63 (1969) 9

People v. Byoune, 65 Cal.2d 345 (1966) 9

People v. Croveda, 65 Cal.2d 199 (1966) 8

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) 7

United States ex rel Davis v. McMann,

386 F .2d 611 (2d Cir. 1967) 8

United States ex rel Goldsby v. Haroole,

263 F.2d 71 (5th Cir. 1959) ‘ 6

United States ex rel Seals v. Wiman,

304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962) 6

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 379 U.S. 931 (1964) 6

OTHER AUTHORITIES

The Defense of Indigents in Criminal

Proceedings, California Assembly Interim

Committee on Criminal Procedure (Jan. 1965) 4

Directory of Judges, Lawyers and Bar

Associations, National Bar Association (Jan. 1972) 4

li

Page

Mexican Americans and the Administration

of Justice in the Southwest, United States

Commission on Civil Rights (March 1970) 3, 4, 5

Report of the National Advisory Commission

on Civil Disorders (Bantam ed. 1968) 3

Report on the San Francisco Public Defender's

Office, San Francisco Committee on Crime

(Oct. 22, 1970) 3, 4, 5

Silver, The Imminent Failure of Legal

Services for the Poor, 46 J. of Urban

Law 217 (1969) 5, 6

ill

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

)FLEETA DRUMGO, )

)Petitioner, )

)vs. )

)SUPERIOR COURT, COUNTY OF MARIN, )

)Respondent, )

)THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, )

)Real Party in Interest. )

)

NO. SF 22953

BRIEF OF

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICUS CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

is a non-profit corporation formed in 1939 under the laws of

the State of New York. It was founded to assist black people

who suffer injustice by reason of race or color to secure

their basic rights through the legal process and to challenge

in the courts practices in our society that bear with

discriminatory harshness on racial minorities and the poor.

-1-

The Western office of the Legal Defense Fund,

located in San Francisco, receives a very large volume of

pleas for assistance from persons in California accused or

convicted of crime in California courts. The Fund is able

to handle only a few cases involving important issues of

reform in the administration of criminal justice. One of

the Fund's concerns, therefore, is assuring that criminal

defendants are afforded effective assistance of counsel.

The Fund believes that the decision of the Court of Appeal

in this case is sound as a matter of law and policy in

recognizing that indigent criminal defendants may in

appropriate circumstances be entitled to appointed counsel

of their choice.

ARGUMENT

In resolving the question presented in this case,

the Court should take account of serious problems of

representation of defendants from racial minorities and the

need for creating confidence in appointed counsel and the

courts.

In investigating the causes of the civil

disturbances of the 1960's, the Kerner Commission found

that "The belief is pervasive among ghetto residents that

lower courts in our urban communities dispense 'assembly-line'

justice" and that "the apparatus of justice in some areas has

-2-

itself become a focus for distrust and hostility." Rep

of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders,

p. 337 (Bantam ed. 1968). In California, the San Francisco

Committee on Crime found that:

"Many residents of minority communities, not

only in San Francisco but in most American

cities as well, distrust the criminal justice

system as a manifestation of a white-dominated

power structure having little interest in

protecting minority rights or interest."

Report on the San Francisco Public Defender's

Office, p. 14 (Oct. 22, 1970).

The United States Commission on Civil Rights did an exhaustive

study of the experience of Mexican Americans with the

administration of justice in California and other states and

found that:

"Mexican Americans are distrustful of the

courts and believe them to be insensitive to

Mexican American background and culture."

Mexican Americans and the Administration of

Justice in the Southwest, p. 62 (March, 1970).

Part of this minority disaffection with the courts

is a widespread mistrust of lawyers assigned to represent

minority defendants in the lower criminal courts. Specifically,

the San Francisco Crime Committee found that:

"There is a deep-seated antagonism toward

the San Francisco Public Defender's Office

among minority groups, particularly in the

Black communities of Hunter's Point and the

Western Addition. . ." Report on the San

Francisco Public Defender's Office, p̂

(Oct. 22, 1970).

The United States Commission on Civil Rights similarly found

that one of the principal sources of Mexican American distrust

-3-

of the legal system is the quality of representation by

assigned counsel. Mexican Americans and the Administration

of Justice in the Southwest, pp. 54-55, 69 (March, 1970).

The disaffection with counsel appointed to

represent indigent defendants from racial minorities is

due not simply to the indifference of public defenders or

the inadequate resources furnished to such offices for

representation of the poor — factors that affect all

1/indigent defendants regardless of race. The confidence

of racial minorities in assigned counsel has also been

impaired by insensitivity to their special needs and the

legal issues peculiarly relating to them. Practically all

2/

the lawyers assigned to represent them are white; one of

the major deficiencies the San Francisco Committee on Crime

1/ The San Francisco Crime Committee's report, which was

highly critical of the San Francisco Public Defender,

found that the Defender conceives of "the function of

his office as 'processing' so many 'head' at a minimum

cost to the city per head; he takes pride in clearing

the calendar at a small per capita cost and is unaware

of the moral problems involved. The minority communities

of the City feel this and resent it." Report on the San

Francisco Public Defender's Office, p. 12 (Oct. 22, 1970).

Concerning the inadequate resources devoted to the

criminal defense of indigents, see generally California

Assembly Interim Committee on Criminal Procedure, The

Defense of Indigents in Criminal Proceedings (January,

1965) .

2/ There is a severe shortage of black lawyers in California.

The National Bar Association estimates that of more than

22,000 lawyers in the state, only 300 are black. National

Bar Association, Directory of Judges, Lawyers and Bar

Associations, p. 140 (January, 1972).

-4-

found in the Public Defender's office was the small

representation of minority groups on the Defender's staff

and the failure of the office to be closer to the localities

from which its clients come. Report on the San Francisco

Public Defender's Office, p. 4 (Oct. 22, 1970).

A special problem faced by Mexican Americans is

that most Anglo lawyers do not speak or understand Spanish,

and the United States Commission on Civil Rights found

evidence that "many Mexican American defendants were not

being adequately represented by the public defender's office

because of the language barrier." Mexican Americans and the

Administration of Justice in the Southwest, p. 69 (March, 1970).

Of course, communication between any middle-class lawyer and

3/a ghetto defendant will be strained.

Apart from communication difficulties, there have

been instances of the failure of white attorneys to raise

legal issues peculiar to defendants from racial minorities.

Thus, one federal Court of Appeals took judicial notice of

the fact that white lawyers virtually never challenged the

3/ The difficulties of communication between lawyers and

poorly educated ghetto residents creates substantial

problems in providing effective legal representation.

See Silver, The Imminent Failure of Legal Services for

the Poor, 46 J. of Urban Law 217, 220 (1969).

-5-

The£/

systematic exclusion of blacks from criminal juries,

indigent's fear that appointed counsel has "sold out" must

be reckoned with in providing representation for the poor.

In summary, racial minorities face special

problems, apart from their poverty, in gaining effective

representation when they are charged with crime. Their

confidence in appointed counsel has been impaired by lack

of minority lawyers, significant communication barriers,

indifference of institutional public defenders, inadequate

resources devoted to indigent representation and failures

of appointed counsel to provide a vigorous and resourceful

defense.

The resulting mistrust of appointed counsel

manifests itself inevitably in the increasingly common

attempts by indigent defendants to disavow the assigned

lawyer, to proceed Ln propria persona, to disrupt courtroom

5/

£/ United States ex rel Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71, 8

(5th Cir. 1959); see also Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 4

507 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 379 U.S. 931 (1964);

United States ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53, 68-69

(5th Cir. 1962) . In Cobb~v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th

Cir. 1964), the appointed white lawyer stated that he was

aware of the constitutional basis for challenging exclusion

of blacks from juries, but chose not to raise the issue

because he_ was satisfied that the all-white jury would

be "fair"T The illegal exclusion of blacks from juries

is not unique to the South and has been documented in

California. See Carmical v. Craven, 457 F.2d 582 (9th

Cir. 1971).

5/ See Silver, The Imminent Failure of Legal Services for

the Poor, 46 J. of Urban Law 217, 220 (1969).

-6-

kO

N)

proceedings and to challenge, in never-ending postconviction

proceedings, the effective assistance of counsel. In short,

where the defendant lacks confidence in appointed counsel,

serious problems in the administration of justice are sure

to be created.

Given the background of distrust and the consequent

problems for the criminal justice system, foisting an unwanted

attorney on a defendant when an attorney in whom he has

confidence is available makes little sense. To the extent

possible, the courts should seek to minimize the lack of

confidence in assigned counsel. We recognize that as a

general proposition indigents are not entitled to choose the

attorney to be appointed by the court, but no valid purpose

is served by making this proposition absolute and inflexible.

We submit that in the exceptional case where a defendant has

managed to obtain a competent attorney willing to serve if

appointed, and private counsel must be appointed in any

event, only a compelling state interest could justify denial

£/

of such appointment. Certainly no strong state interest

6/ In other contexts it has been established that state

regulations regarding legal representation must yield

to the paramount constitutional right, guaranteed by the

First and Fourteenth Amendments, to be represented by

counsel of choice. See Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen

v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1, 8 (1964); NAACP v. Button, 371

U.S. 415, 444 (1963); Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241,

245-47 (5th Cir. 1968) . The courts have reviewed the

reasonableness of the state rules and struck them down

where they unduly or arbitrarily interfered with the right to counsel of choice.

-7-

has been shown in the present case, and the refusal to

appoint the lawyer sought by petitioner Drumgo was purely

arbitrary.

We do not contend that a minority defendant is7/

entitled to a minority lawyer, or to reject a public

defender in favor of private counsel, or to a specific

attorney who may not be immediately available. But in the

exceptional circumstances of this case the holding that

petitioner has the right to an available lawyer whom he

knows and in whom he has confidence follows from well-settled

principles:

Where a defendant is dissatisfied with appointed

counsel and makes good faith efforts to retain his own

attorney, forcing him to trial with unwanted appointed

counsel violates due process of lav;. See United States

ex rel Davis v. McMann, 386 F .2d 611 (2d Cir. 1967); cf.

Brown v. Craven, 424 F .2d 1166 (9th Cir. 1970). This Court

has recognized that the criminal courts "should make all

reasonable efforts to ensure that a defendant financially

able to retain an attorney of his own choosing can be

represented by that attorney," and where the defendant is

denied the opportunity to be represented by his counsel of

choice, he is denied due process. People v. Crovedi, 65

7/ This is obviously impossible, given the small number of

minority lawyers in California. See note 2, supra.

-8-

Cal.2d 199, 207 (1966); People v. Byoune, 65 Cal.2d 345

(1966); see also People v. Butcher, 275 Cal.App.2d 63 (1969).

The result should be no different where, even though an

indigent is financially unable to pay an attorney, he is

able to persuade an attorney in whom he has confidence to

represent him if appointed by the court. That is, in a case

like the instant one where private counsel must be appointed

in any event, and the indigent defendant takes the initiative

in finding a private attorney who is competent, ready,

willing and able to represent him, denial of such appointment

cannot be sanctioned.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

JULIAN J. FONT.ES

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

-9-