Shelby County v. Holder Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 1, 2013

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shelby County v. Holder Brief Amici Curiae, 2013. 9e7acf1d-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d37dc0ac-590c-438c-ab4a-58dcbd78a84a/shelby-county-v-holder-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

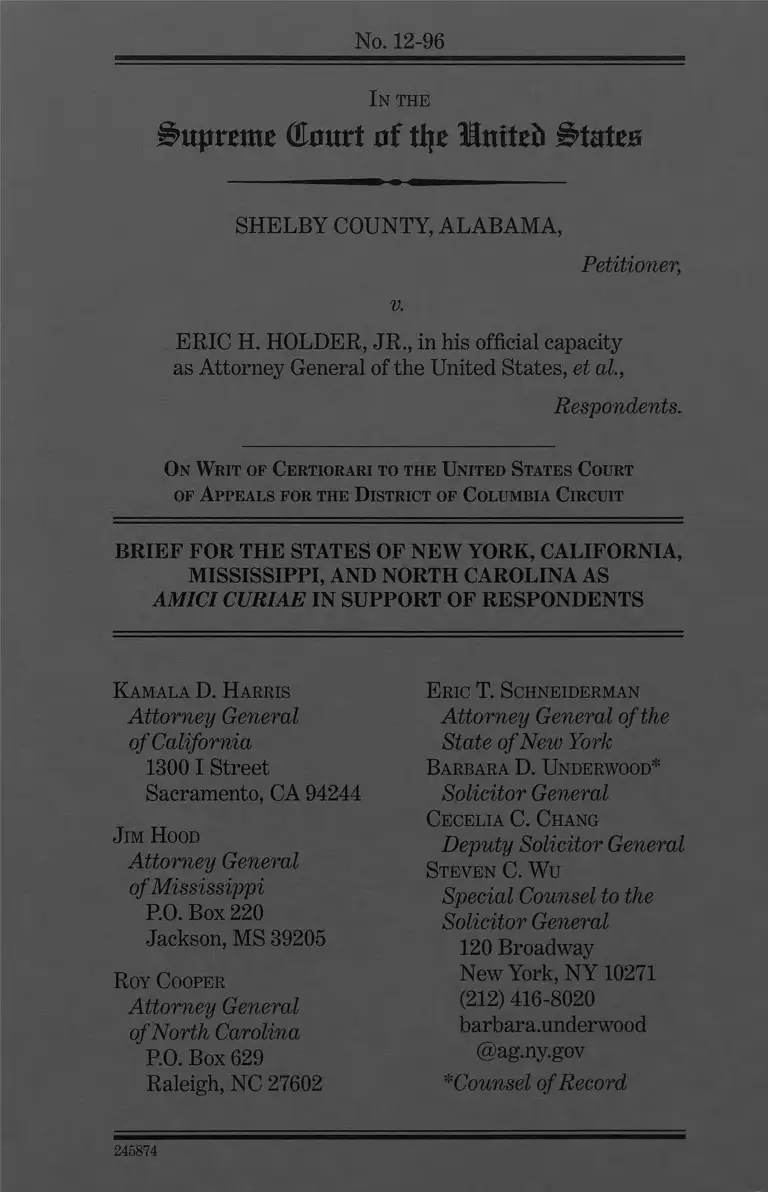

No. 12-96

In the

Supreme Court o f tlie Bnitrft States

SHELBY COUNTY, ALAB AM A,

Petitioner,

v.

ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., in his official capacity

as Attorney General of the United States, et al,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States Court

of A ppeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE STATES OF NEW YORK, CALIFORNIA,

MISSISSIPPI, AND NORTH CAROLINA AS

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

K amala D. Harris

Attorney General

of California

1300 I Street

Sacramento, CA 94244

Jim Hood

Attorney General

of Mississippi

P.O. Box 220

Jackson, MS 39205

Roy Cooper

Attorney General

of North Carolina

RO. Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

E ric T. Schneiderman

Attorney General of the

State o f New York

Barbara D. Underwood*

Solicitor General

Cecelia C. Chang

Deputy Solicitor General

Steven C. W u

Special Counsel to the

Solicitor General

120 Broadway

New York, N Y 10271

(212)416-8020

barbara.underwood

@ag.ny.gov

*Counsel of Record

245874

QUESTION PRESENTED

W hether Congress’s decision in 2006 to reauthorize

Section 5 o f the Voting Rights Act under the pre-existing

coverage formula of Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act

exceeded its authority under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments and thus violated the Tenth Amendment and

Article IV o f the United States Constitution.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amici Curiae..................................................... 1

Summary of Argument......................................................... 2

Argum ent.................................................................................4

I. Preclearance of Voting Changes Continues

to Be a Proper Means of Enforcing the

Voting Rights Guaranteed by the Fifteenth

Am endm ent................................................................4

A. The preclearance process does not

im pose undue burdens on covered

jurisdictions....................................................... 4

B. Preclearance is a critical complement

to case-by-case litigation.............................. 10

II. The Bailout and Bail-in Procedures o f

the Voting Rights Act Provide a Tailored

Response to Changing Local Conditions

and Thereby Defeat This Facial Challenge

to the Act’s Geographic Coverage...... ................. 16

Conclusion.............................................................................. 24

Page

in

TABLE OF CITED AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Allen v. State Board of Elections,

393 U.S. 544 (1969)..........................................................13

Alta Irrigation District v. Holder, No. ll-cv-758

(D.D.C. July 15,2011).....................................................20

Arizona v. United States, 132 S. Ct. 2492 (2012)...........23

Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of Northern New

England, 546 U.S. 320 (2006)...................................... 23

Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1 (2009 )....................... 12

Branch v. Smith, 538 U.S. 254 (2003) ............................11

City ofBoerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1 9 9 7 )...............18

City of Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 125 (1983). .11

EEC v. National Right to Work Committee,

459 U.S. 197(1982)..........................................................19

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976)....................... 18

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973).........11,12

Holder v. Hall, 512 U.S. 874 (1994)..................................10

Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474 (1990)......................... 14

Jeffers v. Clinton, 740 F. Supp. 585

(E.D. Ark. 1 99 0 )............................................................. 21

McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93 (2003)........................... 13

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981)...............10,13

NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp.,

301 U.S. 1 (1937)..............................................................19

Nevada Department of Human Resources v.

Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721 (2003)......................................17,18

Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400 (1991)................................ 14

Page

IV

Presley v. Etowah County Commission,

502 U.S. 491 (1992)......................................................... 17

Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board,

520 U.S. 471 (1997)......................................................... 10

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964)..................... 13,16

Sanchez v. King, No. 82-0067-M

(D.N.M. Aug. 8 ,1984 )..................................................... 21

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966).. .19

Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509 (2004 )................... 18,23

United States v. Georgia, 546 U.S. 151 (2006)...............22

Washington State Grange v. Washington State

Republican Party, 552 U.S. 442 (2008)........................9

Laws:

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973a............................................................................... 17

§ 1973b..................................................................... passim

§ 197 3c.................................................................................8

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982,

Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 1 3 1 .................................. 20

28 C.F.R.

§§ 51.26-.28.........................................................................11

§§ 51.32-.33........................................................................ 12

Miscellaneous Authorities:

152 Cong. Rec. H5054 (2006)...............................................6

152 Cong. Rec. S7969 (2 0 0 6 )............................................. 15

Cited Authorities

Page

Cited Authorities

Page

Civil R ights Div., DOJ, Notices o f Section 5

Submission A ctivity, h ttp ://w w w .ju stice .

gov/crt/about/vot/sec_5/notices.php........................... 12

Civil Rights Div., DOJ, Section k of the Voting

Rights Act, http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/

vot/misc/sec_4.php#bailout_list.................................. 20

Civil Rights Div., DOJ, Section 5 Resource Guide,

http ://w w w .justice .gov /crt/about/vot/sec_5 /

about.php.......................................................................... 11

Crum, Travis, Note, The Voting Rights A ct’s

Secret Weapon: Pocket Trigger Litigation and

Dynamic Preclearance, 119 Yale L.J. 1992

(2010) .....................................................................................21

Extension of the Voting Rights Act: Hearings before

the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong. 2122 (1981)............................................................. 23

Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta

Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization

and Amendments Act of2006 (Parti): Hearing

before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the

H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 65 (2006).. 14

H.R. Rep. No. 109-478 (2006)..................................8,15,21

VI

Lee, Jessica, The Effects o f Section 5 o f the

Voting R ights A ct: A C aliforn ia Case

Study (M ay 20, 2009) (unpublished honors

thesis, Stanford Univ.), available at http://

Cited Authorities

Page

publicpolicy.stanford.edu/node/349.............................. 16

Modern Enforcement of the Voting Rights Act:

Hearing before the S. Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong. 96 (2006)..................................................... 9

R eauthorization o f the A c t ’s Tem porary

Provisions: Policy Perspectives and Views

from the Field: Hearing Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Property

Rights of the S. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th

Cong. 13 (2 0 0 6 )......................................................... 5, 6, 7

S. Rep. No. 109-295 (2006)...................................................8

Understanding the Benefits and Costs of Section

5 Pre-Clearance: Hearing Before the S. Comm,

on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 10 (2 0 0 6 ).............5, 7, 9

Voting Rights Act: An Examination of the Scope

and Criteria for Coverage Under the Special

Provisions o f the Act: Hearing before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm,

on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 90 (2005 )................... 20

Voting Rights Act: Section 5 of the Act—History,

Scope, and Purpose: Hearing before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm,

on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 84 (2005 )...................15

1

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Shelby County, Alabama, challenges the preclearance

process contained in Section 5 o f the Voting Rights

A ct on the ground that the extraordinary problem s

of discrimination that led to its enactment in 1965 no

longer exist, and that the burdens it imposes on States

and localities are no longer justifiable. Amici States New

York, California, Mississippi, and North Carolina are for

several reasons particularly well qualified to provide the

Court with a perspective that should inform any effort to

resolve that claim.

Mississippi, North Carolina, New York, and California

are among the sixteen States covered in whole or in part by

Section 5’s preclearance process, and thus have extensive

first-hand experience with the costs and benefits o f its

operation. Moreover, Amici States contain a substantial

number of minority voters affected by the enforcement

of Section 5: Mississippi has the largest proportion of

African-Am erican voters o f any State in the country,

North Carolina has the seventh largest proportion of

such voters, and New York and California contain some of

the largest and most diverse counties among the covered

jurisdictions.

In the experience of Amici States, claims that the

preclearance process imposes substantial burdens on the

covered jurisdictions or unreasonably intrudes on state

sovereignty are mistaken. Rather, for Amici States, “ ‘[t]he

benefits o f Section 5 greatly exceed the minimal burdens

that Section 5 may impose on States and their political

subdivisions.” ’ Pet. App. 276a-277a (quoting Amicus

Br. for North Carolina, Arizona, California, Louisiana,

2

Mississippi and New York at 17, Nw. Austin Mun. Util.

Dist. No. One v. Holder, 557 U.S. 193 (2009) (No. OS-

322), 2009 W L 815239, at *2). Moreover, those claims

wrongly minimize the significant and measurable benefits

Section 5 has produced in helping Amici States move

toward their goal o f eliminating racial discrimination

and inequities in voting. The Section 5 preclearance

process has helped bring about tremendous progress

in the covered jurisdictions and continues to be a vital

mechanism to assist Amici States in working to achieve

the equality in opportunities for political participation that

is a foundational principle of our democracy.

Amici States share the commitment to eliminating

racial discrim ination in voting rights that animates

the federal Voting Rights Act. The record assembled

by Congress to support the reauthorization of Section

5 in 2006 shows what Amici States know to be true:

that Section 5 continues to play an important role in

Mississippi, North Carolina, New York, and California,

as well as in the other covered jurisdictions.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

W ith overw helm ing bipartisan support in 2006,

Congress reauthorized the preclearance process contained

in Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Preclearance has

historically been a vital safeguard, and it remains today

an essential tool for preventing voting discrimination.

Tremendous progress has been made in Amici States

and other covered jurisdictions in protecting the rights of

minority voters. Congress reasonably determined in 2006

that the protections of the preclearance process are still

necessary to preserve, secure, and extend these historic

3

accomplishments in eliminating voting discrimination, a

goal that Amici States share.

In Amici States’ experience, the substantial benefits

of the preclearance process have outweighed its burdens

on covered jurisdictions. Preclearance is a streamlined

administrative process that has been refined over the

years to reduce the burden on covered jurisdictions.

Moreover, preclearance provides substantial benefits to

covered States and localities by serving as a critical means

to identify and deter retrogressive and discriminatory

voting-related changes. To the extent that Section

5 im poses federalism costs, its com pliance burdens

are minimal in light o f the unique and irreplaceable

protections preclearance ensures.

I f p reclearan ce w ere elim inated, case -by -case

litigation— principally under Section 2 o f the Voting

Rights A ct— would be the sole means for protecting

minority voters in covered jurisdictions. But Congress

never intended such a result, and practical experience

has confirmed that Section 2 is no substitute for Section

5 ’s p reclearance protections. P reclearan ce fosters

governmental transparency and generates the information

necessary to assess the impact o f voting changes; it

suspends enforcement o f proposed voting laws before

discriminatory changes are implemented; and, by imposing

those safeguards, it serves a powerful deterrent function

that case-by-case litigation would not provide. Moreover,

increased Section 2 litigation would impose federalism

costs o f its own— replacing the minimal administrative

obligations of making preclearance submissions to the

U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) with the prospect of

costly and time-consuming litigation every time a voting

change is proposed.

4

In light o f its prophylactic benefits, the geographic

coverage of Section 5 is also reasonable. In reauthorizing

Section 5, Congress was entitled to look not only to the

specific coverage formula contained in Section 4(b) of

the Voting Rights Act, but also to the A ct’s bail-in and

bailout provisions, which provide alternative avenues for

adjusting preclearance requirements to reflect current

conditions. Through bail-in, a noncovered jurisdiction

that engages in voting discrimination can be ordered to

comply with Section 5’s preclearance procedures; and

through bailout, a covered jurisdiction that demonstrates

a clean record can terminate its preclearance obligations.

These tailoring mechanisms are rarely, if ever, included

in remedial legislation, and their presence in the Voting

Rights Act is sufficient to sustain the Act against facial

invalidation of its coverage and preclearance provisions.

ARGUMENT

I. Preclearance of Voting Changes Continues to Be

a Proper Means of Enforcing the Voting Rights

Guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment

A. The preclearance process does not impose

undue burdens on covered jurisdictions.

Both the practical experience of Amici States and

the evidence in the congressional record confirm that

the administrative obligations associated with Section

5 compliance are not substantial. At every stage— data

compilation, submission of materials to DOJ, and review of

the materials by DOJ— the process has been streamlined

to minimize the burden on covered jurisdictions.

5

The materials necessary for DOJ’s limited Section

5 review are ordinarily both readily accessible and easy

to assemble. In general, covered jurisdictions need only

com pile enough inform ation to help DOJ determ ine

w hether a voting-related change was adopted with

a d iscrim inatory purpose or w ill have the effect o f

worsening the position of minority voters. The information

relevant to that analysis is often part o f the legislative

record compiled in the period preceding adoption of the

new law or change.

Congress heard testimony that preparing Section

5 preclearance submissions is “a task that is typically a

tiny reflection of the work, thought, planning, and effort

that had to go into making the [election] change to begin

with.” Understanding the Benefits and Costs of Section

5 Pre-Clearance: Hearing Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 10 (2006) (“Benefits and Costs”)

(testimony of Armand Derfner). As one election official

testified, “preclearance requirements are routine and

do not occupy an exorbitant amount of time, energy or

resources.” Reauthorization o f the A ct’s Temporary

Provisions: Policy Perspectives and Views from the

Field: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution,

Civil Rights and Property Rights of the S. Comm, on

the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 13 (2006) (quotation marks

omitted) (“Policy Perspectives” ) (testimony o f Donald

Wright).

N or is the actual subm ission o f the Section 5

preclearance materials a costly undertaking. Although, in

the past, covered jurisdictions could make administrative

submissions only on paper by postal or other physical

delivery service, they can now also submit materials

6

by fax or electronic transmission. Moreover, increasing

numbers of jurisdictions maintain the relevant records

electronically, facilitating the process of collecting and

submitting the necessary m aterials. State and local

officials are also generally able to prepare Section

5 submissions easily using tem plates from previous

submissions. Congress heard evidence from one official

that “ [t]he ease and cost of such submissions also improves

with the use o f previous submissions in an electronic

format to prepare new submissions. In my experience,

most submissions are routine matters that take only a few

minutes to prepare using electronic submission formats

readily available to me.” Policy Perspectives, supra, at 313

(emphasis omitted) (testimony o f Donald Wright).

Nor has Section 5 review of voting changes proven

significantly burdensome or intrusive on the time of those

officials who prepare materials for submission to DOJ.

Generally, counsel and staff personnel familiar with the

Section 5 preclearance process prepare administrative

submissions. Thus, the Section 5 preclearance process is

often both routine and familiar to the relevant submitting

officials. See 152 Cong. Rec. H5054 (2006) (“Pre-clearance

requirements are routine, and do not occupy exorbitant

amounts of time, energy or re-sources.” (quotation marks

omitted)). These officials, given their fam iliarity and

experience with the process, help ensure that the initial

submission is complete and contains all of the relevant

information that DOJ needs to make its preclearance

determination. The evidence before Congress showed

that covered jurisdictions often “have staff counsel that

prepare submissions as part o f their ongoing duties, so

additional costs are not incurred in those situations. The

costs of submissions are significantly reduced by ensuring

that they are promptly and correctly submitted the first

7

tim e.” Policy Perspectives, supra, at 313. Moreover,

Congress also received evidence confirming that election

officials in covered jurisdictions “viewed Section 5 as a

manageable burden providing benefits in excess of costs

and time needed for submissions.” Id.

In addition, DOJ has administered the Section 5 review

process with a significant degree of flexibility and latitude,

taking into account the unique circumstances and crises

that sometimes emerge within the covered jurisdictions.

As some of Amici States have experienced, DOJ has

expedited its review of voting changes, where possible,

recognizing the crises and challenges that sometimes

befall covered jurisdictions. For example, after Hurricane

Katrina, DOJ issued a letter to Mississippi acknowledging

that DOJ would be ready to expedite its review of any last-

minute voting changes that may have resulted from the

hurricane. Id. at 141-42. In other instances, DOJ has made

swift preclearance determinations— well before the end of

its statutorily required sixty-day review period. Benefits

and Costs, supra, at 10-11 (noting if there is a sudden need

for a new polling place, that can be precleared very swiftly

if there is an election coming up) (testimony of Armand

Derfner); Policy Perspectives, supra, at 312 (election

official noting that he “ never had a situation where the

USDOJ has failed to cooperate with our agency or local

government to ensure that a preclearance issue did not

delay an election”) (testimony of Donald Wright). Amici

States have found that DOJ has administered Section 5

in a manner that neither obstructs nor infringes upon the

dignity and sovereignty of the States.

Shelby County argues that “ Section 5 will foreclose

the im plem entation o f m ore than 100,000 electora l

changes unless and until they are precleared.” Pet.

8

Br. 25. But this number vastly exaggerates the actual

time and expense associated with Section 5 compliance.

A lthough the preclea ra n ce p rocess applies to any

changes to voting practices, as a historical matter DOJ

has generally review ed those changes expeditiously

and raised objections to only the few voting changes

that it found to have a discriminatory purpose or effect.

Moreover, submissions o f multiple voting changes are

often made in a single filing, and this neither slows nor

impairs DOJ’s ability to conduct a speedy review. DOJ’s

careful and targeted exercise o f its Section 5 review has

been a hallmark of its enforcement o f preclearance for

decades: the objection rate has always been only a fraction

of the thousands of voting changes for which it receives

notice. See H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 22 (2006); S. Rep.

No. 109-295, at 13 (2006). Thus, as a practical matter, the

preclearance process permits the vast majority of voting

changes to be implemented as originally enacted, with

only minimal delay. See 42 U.S.C. § 1973c(a) (permitting

voting change if no objection is raised within sixty days).

Finally, there is no basis to conclude that Section 5 as

it is implemented today is more burdensome for covered

jurisdictions than the alternative proposed by Shelby

County and endorsed by the dissent below (Pet. App. 77a):

a world in which the preclearance process is replaced by a

dramatic increase in the amount of case-by-case litigation.

I f every DOJ objection were to be replaced by Section

2 litigation, the burden on covered jurisdictions would

arguably be more severe. I f a voting change is found to

be discriminatory, a court injunction blocking the change

under Section 2 is at least as intrusive as a DOJ objection

under Section 5 because, as this Court has recognized,

9

a judicial injunction against an election procedure is

an “extraordinary and precipitous nullification o f the

will o f the people.” Wash. State Grange v. Wash. State

Republican Party, 552 U.S. 442, 458 (2008). And the

streamlined administrative review of Section 5 is far less

onerous than the ‘“ intensely com plex. . . costly and time-

consuming’” nature of Section 2 litigation, Pet. App. 45a

(quoting Modern Enforcement of the Voting Rights Act:

Hearing before the S. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th

Cong. 96 (2006) (“Modern Enforcement”)), which can

cost millions of dollars and hundreds of hours for States

or localities to defend, see Benefits and Costs, supra, at

80. Indeed, one of the most significant benefits o f the

preclearance process to covered jurisdictions is that a

Section 5 objection will prevent a problematic voting

change from taking effect, thereby reducing the likelihood

that a jurisdiction will face costly and protracted Section

2 litigation.

_ Because Section 2 litigation is so costly and burdensome,

reliance on case-by-case litigation alone would reduce

the overall burdens on covered jurisdictions only if such

litigation failed to reach some of the discriminatory voting

changes currently caught by the preclearance process.

But such a result would reduce the burden on States and

localities only by degrading the overall level of protection

currently afforded to minority voters— raising the risk that

citizens will be denied the right to vote on the basis of their

racial or language-minority status, and undermining the

States own interest in preventing discriminatory voting

changes. For the reasons given below, the preclearance

process provides valuable and irreplaceable protections

for minority voters in covered jurisdictions, and Congress

reasonably determined in 2006 that preclearance should

10

continue to complement case-by-case litigation in the areas

where the two remedies have worked effectively together

for decades.

B. Preclearance is a critical complement to case-

by-case litigation.

For nearly fifty years, preclearance has operated

as an essential complement to case-by-case litigation,

serving “ to forestall the danger that local decisions to

modify voting practices will impair minority access to the

electoral process.” McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130,149

(1981). Shelby County does not contend that remedies for

voting discrimination are no longer needed; it contends

rather that preclearance is no longer necessary because

Section 2 is a sufficient remedy. See Pet. Br. 20, 33. But

Congress has repeatedly determined that Section 2 is

not a sufficient remedy in jurisdictions with a substantial

history of voting discrimination, and that determination

was amply supported by the record before Congress in

2006.1

As this Court has recognized, Sections 2 and 5 “differ

in structure, purpose, and application,” Holder v. Hall,

512 U.S. 874, 883 (1994) (opinion of Kennedy, J.), and

they have long been understood “ to combat different

evils,” Reno v. Bossier Parish Sch. Bd., 520 U.S. 471,

476 (1997). Section 5’s importance as “a prophylactic tool

in the important war against discrimination in voting,”

id. at 491 (Thomas, J., concurring), depends on a set of

features unique to the preclearance process. As important

1 We do not here separately survey the record before Congress

of continuing voting discrimination, which others have amply

described. See U.S. Br. 20-39; Pet. App. 22a-48a, 256a-270a.

11

and effective as Section 2 may be standing alone, it

simply does not duplicate the crucial attributes that have

made preclearance “ [t]he most important . . . remedial

measure [] in the Voting Rights Act, City o f Lockhart

v. United States, 460 U.S. 125, 139 (1983) (Marshall, J.,

concurring in part and dissenting in part).

As explained above, if the Section 5 preclearance

process were replaced by vastly increased litigation activity

under Section 2, the result would not significantly reduce

the burdens imposed on covered jurisdictions. Moreover,

it would greatly reduce the effectiveness o f the Voting

Rights Act in combating voting discrimination because

o f at least three important features o f preclearance that

would be lost without Section 5.

F irst, the preclearance process makes available

information that would otherwise be difficult to obtain,

by requiring covered jurisdictions to provide, for every

voting change, enough documentation to demonstrate

that the proposed change has neither a discriminatory

purpose nor effect. See Branch v. Smith, 538 U.S. 254,

263 (2003); Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526, 540

(1973). That docum entation includes not only copies

of the new voting rule and its predecessor, but also,

inter alia, an explanation o f the differences between

the two, an estimate of the voting change’s impact on

racial or language minorities, and certain demographic

information. See 28 C.F.R. §§ 51.26-.28. The amount of

information generated by preclearance is significant. “ In

a typical year, [DOJ] receives between 4,500 and 5,500

Section 5 submissions, and reviews between 14,000 and

20,000 voting changes.” Civil Rights Div., DOJ, Section

5 Resource Guide, http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/vot/

http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/vot/

12

sec_5/about.php (last visited Jan. 31,2013). DOJ provides

public notice o f all Section 5 submissions and solicits

comments and information on all proposed voting changes.

See 28 C.F.R. §§ 51.32-.33; Civil Rights Div., DOJ, Notices

of Section 5 Submission Activity, http://www.justice.gov/

crt/about/vot/sec_5/notices.php (last visited Jan. 31,2013).

Absent Section 5, it would be difficult or in some

cases impossible for interested parties to obtain the

information needed to determine whether and where to

bring a Section 2 lawsuit, or even to learn that a voting

change is contemplated. This is particularly true in the

case o f smaller governmental entities that may attract

less scrutiny. And although Section 5’s information-forcing

function imposes some costs on covered jurisdictions,

the costs o f gathering and submitting the information

are relatively small because m ost o f the information

submitted for preclearance is readily available to covered

jurisdictions. See supra Point I. A. By contrast, litigation

under Section 2 imposes much more substantial costs

on both the jurisdiction and those who would challenge

voting changes.

Second, Section 5 temporarily suspends enforcement

of proposed voting changes until either DOJ or a three-

judge district court determines that the change is not

discrim inatory. See Georgia, 411 U.S. at 538. This

provisional remedy addresses the significant, irreparable

harms caused by the implementation of a discriminatory

voting rule. The right to vote is “ one o f the m ost

fundamental rights of our citizens.” Bartlett v. Strickland,

556 U.S. 1,10 (2009) (Kennedy, J., plurality op.). Elections

held under unlawful voting rules are often impossible to

unwind, making the loss of a vote permanent even if a

http://www.justice.gov/

13

court subsequently recognizes the election’s illegitimacy.

See, e.g., McDaniel, 452 U.S. at 133 n.5 (noting that

district court permitted primary election to occur under

challenged change); Allen v. State Bd. of Elections, 393

U.S. 544, 571-72 (1969) (declining to set aside already-

conducted elections); see also Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S.

533, 585 (1964) (noting that “equitable considerations”

might prevent court from interfering with imminent

election “even though the existing apportionment scheme

was found invalid” ). And the results of such elections can

alter the distribution of power in far-reaching ways that

cannot be remedied by the correction of future voting

rules: for example, incumbents incur powerful “ [n]ame

recognition and other advantages” that often persist so

long as they seek reelection, McConnell v. EEC, 540 U.S.

93, 307 (2003) (Kennedy, J., concurring in the judgment

in part and dissenting in part). The preclearance process

avoids these irreparable injuries by ensuring that new

voting rules in the covered jurisdictions do not come into

effect until an expedited review determines that a change

has neither a discriminatory purpose nor a discriminatory

effect.

C ase-by-case litigation can provide this kind of

interim relief only in the limited situations where there

are plaintiffs who are sufficiently knowledgeable and

aggrieved about a discriminatory voting change to bring

suit in the first place— and who are then willing and able

to spend the significant time and resources necessary

to “satisfy the heavy burden required for preliminary

injunctive relief.” Pet. App. 47a. To be sure, individual

litigants are sometimes in a position to bring Section 2

cases and obtain preliminary relief. But the obstacles

are so grea t— and the harm from even tem porary

14

im plem entation o f a d iscrim in atory votin g change

so high— that case-by-case litigation is, as Congress

recognized, inadequate to protect against that harm.

P riva te litigan ts are u n lik ely to m arshal the

information, resources, and evidence necessary to obtain

preliminary relief from discriminatory voting changes.

A s with other examples o f discrim inatory exclusion

from the “opportunity to participate in the democratic

process,” Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400,406-408,414-415

(1991) (identifying voting and jury service as the “most

significant” such opportunities), individual citizens often

“possessG little incentive or resources to set in motion the

arduous process needed to vindicate [their] own rights,”

Holland v. Illinois, 493 U.S. 474,489 (1990) (Kennedy, J.,

concurring). That is particularly true in the voting rights

context, since Section 2 cases are usually “very, very

costly” and complex. Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and

Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization

and Amendments Act o f2006 (Part I): Hearing before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 65 (2006) (testimony of J. Gerald

Hebert).

Although DOJ and private litigants may be able

to muster the resources in particular cases to obtain

preliminary relief, they cannot do so for all of the tens of

thousands of voting changes that the preclearance process

currently covers. The dissent below suggested that DOJ

could simply transfer “whatever resources it stopped

spending on § 5” not only to fund its own Section 2 cases,

but also to assume the costs o f private litigation. Pet.

App. 77a. But the costs of litigation are so much greater

than the costs of preclearance that it blinks reality to

15

suppose that such a transfer of resources would result

in funding litigation on the scale needed to substitute for

preclearance.

Third, the prospect that every voting change will

be review ed produces Section 5’s “ m ost significant

impact”: its deterrent effect. 152 Cong. Rec. S7969 (2006)

(testimony o f Sen. Dianne Feinstein). Officials within the

covered jurisdictions know that every voting change will

be reviewed by DOJ for the potential effect on minority

voters. That review makes officials more mindful, leading

them to exercise a greater degree o f due diligence in

considering the potential impacts o f new voting laws.

As Congress found, “ the existence of Section 5 deterred

covered jurisdictions from even attempting to enact

discriminatory voting changes.” H.R. Rep. No. 109-478,

supra, at 24.

Case-by-case litigation lacks a comparable deterrent

effect. Individual plaintiffs will be able to review and

challenge a voting change only if they receive notice of that

change and then muster sufficient resources to initiate

an action. While certain large voting changes (such as

redistricting) may regularly attract individual lawsuits,

see Pet. Br. 20, smaller and more local voting changes will

often and predictably escape any genuine scrutiny— even

though such changes often have the most significant effect

on individual voters’ lives. See Voting Rights Act: Section 5

of the Act— History, Scope, and Purpose: Hearing before

the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 84 (2005). Case-by-case litigation

thus does not replicate the same powerful deterrent effect

that currently prevents discriminatory voting changes

from being implemented in the first instance.

16

For these reasons, case-by-case litigation has not

since 1965 stood by itself as the sole remedy for voting

discrimination in the covered States. Shelby County and its

amici do not dispute that the preclearance requirements

in covered jurisdictions have been responsible for much

of the progress that the Voting Rights Act has achieved

during the last fifty years. See Pet. Br. 22 (“ The Voting

Rights Act of 1965 changed the course of history in the

covered jurisdictions.” ); Br. for Amici Curiae Arizona et

al. 4 (“ Section 5 was an important and necessary part of

the effort to end voter discrimination in this country.. . .” ).2

Eliminating the preclearance process altogether would

fundamentally change the legal landscape in the covered

States, creating a regu la tory vacuum in the space

that preclearance once occupied to protect the m ost

fundamental political right. See Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 567

(“ To the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he

is that much less a citizen.” ).

II. The Bailout and Bail-in Procedures of the Voting

Rights Act Provide a Tailored Response to

Changing Local Conditions and Thereby Defeat

This Facial Challenge to the Act’s Geographic

Coverage

1. When Congress enacted Section 5, it limited the

application of preclearance through a unique tailoring

m echanism . R ather than applying nationw ide, the

2 For example, one researcher has found a positive statistical

correlation between Section 5 and voter registration and turnout

in California. See Jessica Lee, The Effects of Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act: A California Case Study (May 20, 2009)

(unpublished honors thesis, Stanford University), available at

http://publicpolicy.stanford.edu/node/349.

http://publicpolicy.stanford.edu/node/349

17

preclearance process was lim ited to only a discrete

number of covered jurisdictions identified by the coverage

formula of Section 4(b). 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(b). And rather

than being static, Section 5’s geographic range has always

been subject to revision under two procedures that

Congress has periodically liberalized to more accurately

reflect current conditions. The bailout procedure, Section

4(a), permits a covered jurisdiction to terminate its Section

5 obligations upon a showing that it no longer suffers from

voting discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(a). The bail-in

procedure, Section 3(c), addresses the opposite concern:

it permits noncovered jurisdictions to be brought within

the ambit of Section 5 upon a showing that they do suffer

from voting discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 1973a(c).

Like the preclearance process, the Voting Rights Act’s

tailoring mechanism is itself an “extraordinary departure”

from Congress’s ordinary way of applying legislation. Cf.

Presley v. Etowah County Comm’n, 502 U.S. 491, 500

(1992). Congress’s other remedial legislation rarely, if ever,

goes to such lengths to tailor the burdens of a federal law.

Outside the voting rights area, when Congress determines

that remedial legislation is needed, it generally enacts

laws that interfere with state sovereignty nationwide,

even when the evidence of constitutional violations comes

from only a handful of States. See Nevada Dep’t of Human

Res. v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721, 730-32 (2003) (explaining the

record underlying the Family and Medical Leave Act);

see also id. at 753 (Kennedy, J., dissenting) (criticizing

the legislative record for focusing on only three States).

And Congress’s enactments are usually permanent,

with no opportun ity— other than the possib ility o f

legislative amendment— for the States to contend that

18

they no longer fall within the original justification for

a law. Thus, this C ourt has upheld several statutes

abrogating state sovereign immunity for civil rights laws

on the basis o f evidence of state discrimination preceding

each enactment. See Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509,

524-26 (2004) (disability); Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 730 (gender);

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976) (race). But this

Court has never suggested that these statutes must be

reevaluated to determine whether current conditions

continue to justify these laws.

The Voting Rights A ct’s tailoring mechanism departs

from both of these ordinary characteristics of federal

rem edial legislation, and in each case it does so in

order to reduce the intrusion on state sovereignty. The

targeted rather than nationwide scope of the preclearance

process prevents Section 5 from applying more broadly

than necessary, confining it to those regions o f the

country where Congress had specific evidence of voting

discrimination. See City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S.

507, 532-33 (1997) (discussing Voting Rights Act). And

the bailout and bail-in procedures perm it Section 5’s

coverage to be adjusted to more accurately reflect current

conditions. 2

2. Shelby County seeks to invalidate here only one part

of this integrated scheme, Section 4(b), on the argument

that the coverage formula is “outdated.” Pet. Br. 13,57. But

the baseline established by Section 4(b) was imperfectly

tailored almost from the beginning, and has nonetheless

repeatedly been sustained against that challenge. As this

Court acknowledged in upholding Section 4(b) in 1966,

even at the outset the coverage formula did not include

every jurisdiction that engaged in voting discrimination,

19

and evidence of voting discrimination was much stronger

for some covered jurisdictions than for others. South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 329-30 (1966).

But Congress never intended Section 4(b) to operate

alone to identify covered jurisd ictions. Rather, the

coverage formula has always been part o f a dynamic

process of both exempting and including jurisdictions from

the preclearance process based on changing conditions and

experience. The baseline established by Section 4(b) thus

reflected historical experience without giving that history

controlling weight. And the bailout and bail-in provisions

were enacted and later amended precisely to adapt the

actual coverage o f Section 5 to current conditions.

Today, the statutory triggers of Section 4(b) no longer

accurately describe the areas of the country covered by

Section 5 because successful bailouts and bail-ins have

updated the list of jurisdictions to which the preclearance

process applies. See U.S. Br. App. la -lla . The progress

of this tailoring process may not be as swift as Shelby

County and its amici prefer. But Congress is permitted

to proceed by incremental steps in addressing national

problems; it need not “embrace all the evils within its

reach” when it legislates, NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin

Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1,46 (1937), and its decision to do so

“warrants considerable deference,” FEC v. Nat’l Right to

Work Comm., 459 U.S. 197, 209 (1982). With the Voting

Rights Act, Congress built into the statute itself a process

to incrementally alter the reach of Section 5. That tailoring

mechanism is a virtue of the Act because it is so solicitous

of the sovereignty of the covered States; it is not, as Shelby

County would have it, a flaw that requires invalidating the

preclearance process altogether.

20

3. The amici states opposing the 2006 reauthorization

contend that bailout and bail-in are not practically

available remedies. See Br. for Amici Curiae Arizona

et al. 27; Br. for Amicus Curiae Alaska 29. But Amici

States’ experience demonstrates otherwise. The 1982

amendments to the A ct “ made bailout substantially

more perm issive” in two ways: it “allowed bailout by

any jurisdiction with a ‘clean’ voting rights record over

the previous ten years” ; and it permitted any political

subdivision within a covered State to seek bailout. Pet.

App. 9a; see Voting Rights A ct Amendments o f 1982,

Pub. L. No. 97-205 § 2(b)(2), 96 Stat. 131, 131 (codified,

as amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(a)(l)). As a result of

those amendments, every covered jurisdiction that has

requested a bailout since 1984 has received it. Civil Rights

Div., DOJ, Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act, http://www.

justice.gOv/crt/about/vot/misc/sec_4.php#bailout_list (last

visited Jan. 31,2013).

C o n g ress h eard testim on y that th ese bailou t

applications were neither costly nor time-consuming.

“ Legal expenses for the entire process of obtaining a

bailout are on average about $5000.” Voting Rights Act:

An Examination of the Scope and Criteria for Coverage

Under the Special Provisions of the Act: Hearing before

the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 90 (2005) (statement of J. Gerald

Hebert). And generally it takes less than five months to

obtain a court order terminating a political subdivision’s

Section 5 responsibilities— indeed, one political subdivision

in California was bailed out within ninety days of filing

its petition, see Alta Irrigation District v. Holder, No.

ll-cv-758 (D.D.C. July 15, 2011) (consent judgment and

decree), available at http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/

http://www

http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/

21

vot/misc/alta_cd.pdf, although the process has sometimes

been more prolonged, see Br. for Amicus Curiae Merced

County, California, in Support o f No Party 30-35. This

experience demonstrates that the bailout procedure is

a workable mechanism that allows eligible jurisdictions

to exempt themselves from the requirements of Section

5. See H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, supra, at 61 (bailout “has

proven to be achievable to those jurisdictions that can

demonstrate an end to their discriminatory histories”).

The bail-in provision has likewise been used to

extend preclearance to a number of formerly noncovered

jurisdictions, on the basis o f specific findings that those

jurisdictions suffer from voting discrim ination. See

generally Travis Crum, Note, The Voting Rights Act’s

Secret Weapon: Pocket Trigger Litigation and Dynamic

Preclearance, 119 Yale L.J. 1992,2010 (2010) (discussing

bail-in examples). For example, in Jeffers v. Clinton,

Arkansas was bailed in after the district court found

that “ [t]he State ha[d] systematically and deliberately

enacted” certain voting laws “ in an effort to frustrate

black political success in elections traditionally requiring

only a plurality to win.” 740 F. Supp. 585, 586 (E.D. Ark.

1990). New Mexico was likewise brought within the scope

of Section 5 after a district court found that the State’s

1982 redistricting plan constituted “a racially-motivated

gerrymander.” See Sanchez v. King, No. 82-0067-M, slip

op. at 129 (D.N.M. Aug. 8,1984). Finally, several political

subdivisions have been required to submit voting changes

for preclearance, again after specific findings that they

engaged in voting discrimination. See U.S. Br. App. la-3a. 4

4. Shelby County concedes that the bail-in procedure

is a “ targeted” and “ appropriate means o f imposing

22

preclearance” based on a contemporaneous finding that a

noncovered jurisdiction has engaged in “unconstitutional

voting discrimination.” Pet. Br. 57. But it contends that

“bailout is incapable of saving Section 4(b),” in essence

because there is not a one-to-one correspondence between

the reasons for a jurisdiction’s original inclusion, and the

criteria for its bailout. Pet. Br. 54-55.

This argum ent in correctly assum es that state

sovereignty not only mandates a bailout procedure, but

also requires that procedure to take a particular form.

This Court has never so limited Congress’s power. As

noted earlier, outside the voting rights area, none of

the laws that Congress has recently enacted pursuant

to its enforcem ent powers under the Reconstruction

Amendments offer an exemption procedure to the States.

As a result, the mere existence of bailout and bail-in makes

Section 5 more respectful of state sovereignty than other

federal legislation enforcing those amendments.

In any event, whatever objections covered jurisdictions

may have to the current administration of the bailout

procedure, that procedure is more suited than this facial

challenge as a mechanism for responding to changing

conditions in this country. By providing a specialized

process for adjusting the coverage of Section 5, the bailout

procedure, along with the bail-in procedure, permits

individual jurisdictions to “ create a factual record ”

supporting their claims about the proper reach of the

preclearance process. United States v. Georgia, 546 U.S.

151,160 (2006) (Stevens, J., concurring).

Some other state amici have also raised objections

to DOJ’s particular interpretation or enforcement of the

Voting Rights Act. See, e.g., Br. for Amici Curiae Arizona

23

et al. 25-27; Br. for Amicus Curiae Texas 3-4; Br. for

Amicus Curiae Alabama 14-20. But complaints about

individual enforcement efforts— on which this group of

Amici States takes no position— do not undermine the

facial validity of Sections 4(b) and 5. This Court has

recently made clear that the mere fact that a statute

might “ in practice” be unconstitutionally enforced does

not require its facial invalidation when the statute “could

be read” and enforced in a manner that “avoid[s] these

concerns.” Arizona v. United States, 132 S. Ct. 2492,2509

(2012). As a result, the other state amici’s complaints

about specific, allegedly improper enforcement efforts are

best left to individual litigation, where courts can examine

the “ specific facts” necessary to determ ine whether

DOJ’s actions were reasonable. Extension of the Voting

Rights Act: Hearings before the Subcomm. on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary,

97th Cong. 2122 (1981) (statement of Drew Days).

R ejecting Shelby County’s facial challenge here

would not foreclose future bailout petitions or individual

proceedings challenging DOJ’s enforcement decisions. In

some of those proceedings, individual jurisdictions may

be able to prove that preclearance is no longer necessary

due to their unique facts, or that DOJ’s application of the

Voting Rights Act is unreasonable. But that possibility

is not a proper basis to forbid the application of Section

5 “ wholesale” to any jurisdiction, Ayotte v. Planned

Parenthood ofN. New England, 546 U.S. 320,331 (2006);

see Lane, 541 U.S. at 530 (limiting review of Title II of

the Americans with Disabilities Act to the particular

application at issue, access to the courts, rather than

“ its wide variety of applications” ). In the meantime,

sustaining Sections 4(b) and 5 on their face would permit

24

the unique remedy of preclearance to continue in the

covered States— preserving and extending the historic

accomplishments that the Voting Rights Act has already

achieved.

CONCLUSION

The judgm ent o f the court o f appeals should be

affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

K amala D. Harris

Attorney General

of California

13001 Street

Sacramento, CA 94244

Jim Hood

Attorney General

of Mississippi

RO. Box 220

Jackson, MS 39205

Roy Cooper

Attorney General

of North Carolina

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

E ric T. Schneiderman

Attorney General of the

State of New York

Barbara D. Underwood*

Solicitor General

Cecelia C. Chang

Deputy Solicitor General

Steven C. W u

Special Counsel to the

Solicitor General

120 Broadway

New York, NY 10271

(212) 416-8020

barbara.underwood

@ag.ny.gov

*Counsel of Record

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 12-96

------------------------ ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- x

SH ELBY COUNTY, ALABAM A,

Petitioner,

v.

E R IC HOLDER, JR., IN HIS O FFICIAL CAPACITY

AS ATTORN EY G EN ERAL OF THE UN ITED STATES, ET AL.,

Respondents.

■X

STATE OF NEW YORK )

COUNTY OF NEW YORK )

I, Maria Piperis, being duly sworn according to law and being over the age o f 18,

upon my oath depose and say that:

I am retained by Counsel o f Record for Amici Curiae.

That on the 1st day o f February, 2013, I served the within Brieffor The States o f New

York, California, Mississippi, and North Carolina as Amici Curiae in Support o f

Respondents in the above-captioned matter upon:

Bert W. Rein

Wiley Rein LLP

Attorneys for Petitioner

M l 6 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20006

(202)719-7000

Brein@wilevrein.com

Debo P. Adegbile

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

Attorneys for Respondents

99 Hudson Street, 16'1' Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212)965-2249

Dadegbile@naacpldf.org

mailto:Brein@wilevrein.com

mailto:Dadegbile@naacpldf.org

Jon M. Greenbaum

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

1401 New York Avenue, NW, Suite 400

Washington, DC 20005

(202)662-8315

igreenbaum@lawyerscomrnittee.org

Laughlin McDonald

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

230 Peachtree Street NW

Atlanta, GA 30303-1504

(404)523-2721

imcdonald@, aclu.org

Donald B. Verrilli, JR.

Solicitor General

United States Department o f Justice

950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20530-0001

(202)514-2217

supremectbriefs@usdoi.gov

by depositing three copies o f same, addressed to each individual respectively, and

enclosed in a post-paid, properly addressed wrapper, in an official depository maintained

by the United States Postal Service, via Priority Mail.

That on the same date as above, I sent to this Court forty copies o f the within

Brief for The States o f New' York, California, Mississippi, and North Carolina as Amici

Curiae in Support o f Respondents through the United States Postal Service by Express

Mail, postage prepaid.

All parties required to be served have been served.

1 declare under penalty o f perjury that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed on this 1st day o f February, 2013.

0

C O U N S E L PRESS

( 800) 274-3321 * ( 800) 359-6859

www.counselpress.com

mailto:igreenbaum@lawyerscomrnittee.org

mailto:supremectbriefs@usdoi.gov

http://www.counselpress.com

Sworn to and subscribed before me this 1st day o f February, 2013.

NotMy PuMc State af NM Vbrt>

N0.24-4799M1

QuaMM «n Ktap County .

Commission *05. 31, K l j

# 245874

0

C O U N S E L PRESS

(800) 274-3321 * ( 800) 359-6859

www.counselpress.com

http://www.counselpress.com

SUPREM E COURT OF THE U N ITED STATES

No. 12-96

SH ELBY COUNTY, ALABAM A,

Petitioner,

v.

ER IC HOLDER, JR., IN HIS O FFICIAL CAPACITY

AS ATTO RN EY G EN ER AL OF THE UN ITED STATES, ET AL.,

Respondents

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------x

C E R T IF IC A T E O F C O M P L IA N C E

As requ ired by S uprem e C ourt R u le 33 .1(h ),

I ce r tify that the docum ent contains 6,090 w ords,

exclud ing the parts o f the docum ent that are exem pted

by Suprem e C ourt R u le 33 .1 (d ).

I declare under p en a lty o f p er ju ry that the fo re g o in g

is true and correct.

Executed on February 1, 2013.

Y ? U

M aria P ip eris

Sworn to and subscribed before me

this 1st day o f February, 2013.

Elias Melendez

ctlasivManda*

Notary PubMe, State efNewYorV

No. 24-47996*1

Qualified In Kings County /

#2&ftS»slon fetpira? Aug. 31,2«_/2/