(AFSCME) v. Washington Brief Amicus Curiae of LDF; The National Association of Black Women Attorneys, et. al

Public Court Documents

November 16, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. (AFSCME) v. Washington Brief Amicus Curiae of LDF; The National Association of Black Women Attorneys, et. al, 1984. 22c550f6-ab9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3816184-9a75-44d7-8541-6717907213eb/afscme-v-washington-brief-amicus-curiae-of-ldf-the-national-association-of-black-women-attorneys-et-al. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/

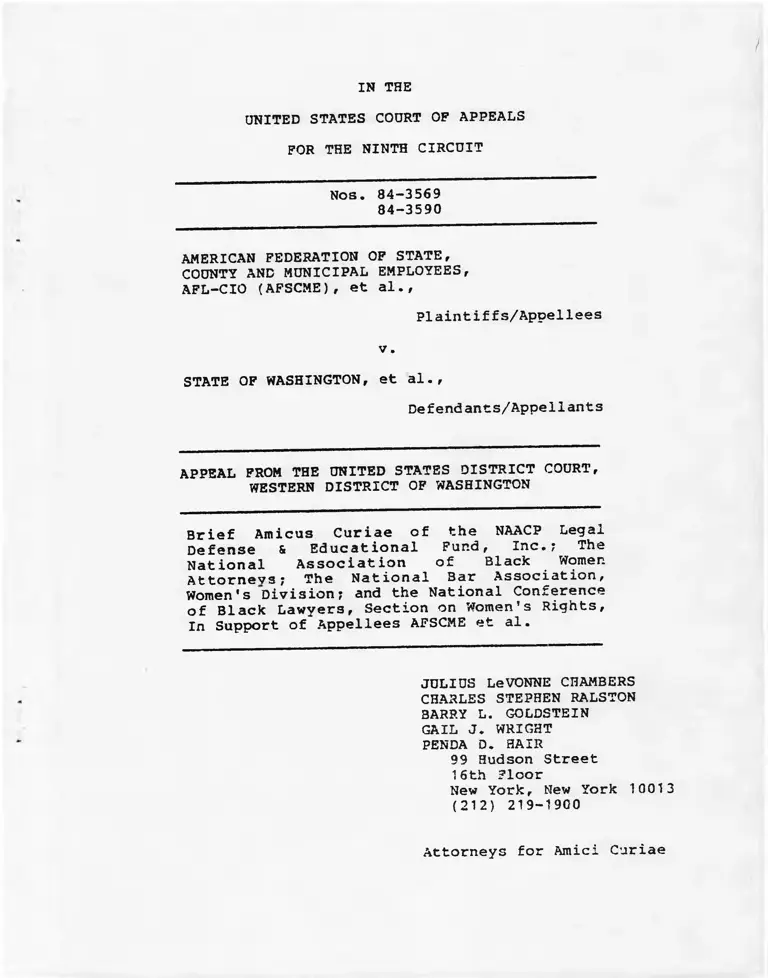

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 84-3569

84-3590

AMERICAN FEDERATION OP STATE,

COUNTY AND MUNICIPAL EMPLOYEES,

AFL-CIO (AFSCME), et al.,

Plaintiffs/Appellees

v.

STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al.,

Defend ants/Appel1ants

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT,

WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON

Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.; The

National Association of Black Women

Attorneys; The National Bar Association,

Women's Division; and the National Conference

of Black Lawyers, Section on Women’s Rights,

In Support of Appellees AFSCME et al.

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

GAIL J. WRIGHT

PENDA D. HAIR

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page

TTTable of Authorities ..................................

Interests of Amici Curiae .............................

Summary of Arqument ...................................

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court's Finding of Intentional

Discrimination Is Supported by the Appli

cable Legal Principles ......................

A. The District Court's Finding of Inten

tional Discrimination Is Entitled to

Deference ..............................

B. The Decision Below Is Consistent with

Precedents Establishing Methods of

Proof of Intentional Discrimination ....

1. The federal courts have fre

quently found intentional race

discrimination in wages on the

basis of evidence similar to

that in the record ...............

2. The race-based wage discri

mination precedents are con

sistent with the analysis

applied in hiring and promo

tion cases ........................

3. Other indicia of discrimina

tion exist in this case .........

II. The District Court's Finding that Defen

dant Illegally Perpetuated the Effects of

Prior Discrimination Is Supported by the

Applicable Legal Principles ...............

III. The Decision in Pouncv v. Prudential

Insurance Company Is Incorrect and

Should Not be Followed .....................

2

6

8

6

10

1 1

1 1

14

22

24

27

CONCLUSION 33

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Case Page

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972).......... . 24

Alston v. School Bd . , 112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 311 U.S. 693 ( 1 940) ........................ 8

Arkansas Educ. Ass'n v. Bd. of Educ., 446 F.2d 763

(8th Cir. 1971) .................................... 8

Bonilla v. Oakland Scavenger Co., 697 F.2d 1297 (9th

Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 52 U.S.L.W. 3906 (June

1 8, 1984) .......................................... 1 1

Briags v. City of Madison, 536 F.Supp. 436 (D. Wise.

1982) 1 7, 1 9

Carpenter v. Stephen F. Austin State Univ., 706

F. 2d 608 ( 5th Cir. 1983) .................. 8,9,1 3,1 6,21,29

Carroll v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 708 F.2d 183 (5th

Cir. 1983) ......................................... 29

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) 30

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan, 417 U.S. 188 (1974) ....17,18

County of Washinaton v. Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981) ... 9,16

Crawford v. Western Elec. Co., Inc., 614 F.2d 1300

(5th Cir. 1980) .................................... 28

Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957, 964 (D.C. Cir. 1979) . 15

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Auth., 704 F.2d 613,

(11th Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 52 U.S.L.W. 3631

(Feb. 28, 1 984) 28

EEOC v. Inland Marine Indust., 729 F.2d 1229 (9th

Cir.), cert, denied, 53 U.S.L.W. 3239 (Oct. 2,

1984) .......................................... 8,1 4, 1 8,24

- ii -

Case Page

EEOC v. Sandia Savings 4 Loan Ass'n, 24 Empl. Prac.

Dec. (CCH) 1131,200 (D.N.M. 1980) ................. 1 3

Gilbert v. City of Little Rock, 722 F.2d 1390 (8th

Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 52 U.S.L.W. 3828 (May

1 5, 1 984) .......................................... 28,32

Griffin v. County School Bd., 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .... 26

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ........ 27,28

Hamed v. I.A.B.S.0.I., 637 F.2d 506 (8th Cir. 1980) ... 28

Harrell v. Northern Elec. Co., 672 F.2d 44 (5th

Cir.), reaffirmed in relevant part, 679 F.2d

31 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1037

( 1982) ............................................. 29

Harris v. Ford Motor Co., 651 F.2d 609 (8th Cir. 1981).. 28

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1 977) .................................... 1 4, 1 5

Heaaney v. Univ. of Washington, 642 F.2d 1157

(9th Cir. 1981) .................................... 16,29

Hishon v. King & Spaulding, 52 U.S.L.W. 4627

(May 22, 1984) ..................................... 20

International Union of Electrical Workers v.

Westinghouse Electric Corp., 631 F.2d 1094

(1980), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 967 (1981) ......... 25

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

1 034 ( 1 978) ........................................ 8

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc., 628 F.2d 419 (5th

Cir. 1980), remanded for further consideration,

451 U.S. 902 (1981), reaffirmed in relevant

Dart, 657 F.2d 750 (1981), cert, denied, 459

U.S. 1 67 ( 1982) ..................................... 28

Liberies v. County of Cook, 709 F.2d 1122 (7th Cir.

1983) 25,26

- i i i -

Case

Lynn v. Regents of University of California, 656

F.2d 1337 (9th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S.

823 ( 1 982) ........................................ 9

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ............................................. 9,20

Moore v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., 708 F.2d 475

(9th Cir. 1 983) .................................... 29

Mortensen v. Callaway, 672 F.2d 822 (10th Cir. 1982) .. 28

Morris v. Williams, 149 F.2d 703 (8th Cir. 1945) ..... 8

O'Brien v. Sky Chefs Inc., 670 F.2d 864 (1982) ....... 23

Pace v. U.S. Indust., Inc., 726 F.2d 1038 (5th Cir.

1984) 29

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc. 673 F.2d 798

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982) .... 23

Peters v. Lieuallen, 693 F.2d 966 (9th Cir. 1982) .... 29

Pittman v. Hattiesburg Municipal Separate School

District, 644 F.2d 1071 (5th Cir. 1981) 11,17,18

Pope v. City of Hickory, 679 F.2d 20 (4th Cir.

1 982) 28

Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Co., 668 F.2d 795

(5th Cir. 1 982) ................................ 7,27,28,32

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ....... 10,31

Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505

(E.D. Va. 1968) ....................... 8,11,12,13,16,21,24

Rowe v. Cleveland Pheumatic Co., 690 F.2d 88 (6th

Cir. 1982) 28

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1 972) ......................................... 23,28

IV

Case Page

R u l e v . I . A . B . S . 0 . I . , L o c a l U n ion No. 3 9 6 , 568

F.2d 558 (8th Cir. 1977) .......................

Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F.Supp. 690 (D.D.C. 1981),

aff'd in relevant part, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir.

1 984) ........................................ 8,9, 1 3, 16,

Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984) ....... 28,

Spaulding v. Univ. of Washington, 740 F.2d 686

(9th Cir. 1984) ....................................

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ...... 14,

23,26,

Thompson v. Gibbes, 60 F.Supp. 872 (E.D.S.C. 1945) ....

United Papermakers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)...

Village of Arlinaton Feiqhts v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp. , 429 U.S. 252 ( 1977) ............ 22,

Vuyanich v. Republic Nat'l Bank, 505 F.Supp. 224 (N.D.

Tex. 1980), vacated on other qrounds, 723 F.2d

1195 (5th Cir. 1984) ....... .............. 8,9, 1 3, 1 9,20,

Wade v. Mississippi Coop. Extension Serv., 528 F.2d

508 (5th Cir. 1 976) .......................... 8,9, 13,21 ,

Wang v. Hoffman, 694 F.2d 1146 (9th Cir. 1982) .......

Wells v. Hutchinson, 499 F.Supp. 174 (E.D. Tex.

1980) .............................................. 8,

28

21

31

29

15

31

8

24

23

21

23

29

1 3

v

REGULATIONS Page

29 CFR $1 607 .......................................... 32

LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Conq., 1st Sess................... 9,31

H. R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess............... 8,9,31

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Petition for Certiorari, Anderson v. City of

Bessemer, No. 83-1623, cert, granted, 52

U.S.L.W. 3906 (June 1 8, 1 984) ..................... 1 1

H. Hill, Black Labor and the American Legal System

(1977) .............................................. 8

H. Northrup, R. Rowan, D. Barnum & J. Howard, Negro

Employment in Southern Industry (1970) 8

Wachtel, The Negro and Discrimination in Employment

(1965) ..... 8

vi

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 84-3569 84-3590

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF STATE,

COUNTY AND MUNICIPAL EMPLOYEES,

AFL-CIO (AFSCME), et al. ,

Plaintiffs/Appellees

v.

STATE OF WASHINGTON , et al.,

Defendants/Appellants

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT,

WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON

Brief Amicus Curiae of the NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.; The

National Association of Black Women

Attorneys; The National Bar Association,

Women's Division; and the National Conference

of Black Lawyers, Section on Women's Rights,

In Support of Appellees AFSCME et al.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.; The

National Association of Black Women Attorneys; The National Bar

Association, Women's Division; and the National Conference of

Black Lawyers, Section on Women's Rights, submit this brief as

amicus curiae in support of plaint iffs/appellees with the consent

of all the parties.

INTERESTS OF AMICI CORIAE

1 The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

("The Legal Defense Fund" or "LDF") is a non-profit corporation,

which was established for the purpose of assisting black citizens

in securing their constitutional and civil rights. LDF, which is

independent of the other orqanizations, is supported by contribu

tions from the public. For many years its attorneys have

represented parties and participated as amicus curiae in numerous

cases before the federal appellate and district courts throughout

the nation, and the United States Supreme Court. The Legal

Defense Fund has appeared as amicus curiae in actions challenging

employment discrimination against blacks and women under the

Constitution and federal statutes; and has also urged the full

enforcement of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to

remedy the causes and effects of such prohibited and invidious

discrimination.

2. The National Association of Black Women Attorneys

("ABWA" ) is a non-profit legal corporation organized in 1 972 to

advance the practice of law for black women, and to improve the

administration of justice by increasing the opportunities of

black women in all spectrums of American society. The organiza

tion is comprised of 550 members from around the country whose

purpose it is to advance causes of civil and human rights. In

2

furtherance, of this goal, ABWA has participated in lawsuits

brought to eliminate vestiges of racial and sexual discrimina

tion .

3. The National Bar Association, Women's Division, is a

non-profit bar association founded in 1972 as a division within

the National Bar Association, itself a non-profit corporation

established in 1925, and currently comprised of 1 1 , 0 0 0 members.

The organization, which has a membership of 110, aims to promote

the fair administration of justice to all and improvement in the

community at-large. The Women's Division focuses on issues and

concerns that are unique to black women. Hence, it is dedicated

to promoting and protecting the rights of black women, and

gaining access to opportunities from which they have so long been

excluded. The NBA, Women's Division, has particpated in lawsuits

designed to secure full enforcement of laws prohibiting employ

ment discrimination.

4. The National Conference of Black Lawyers, Section On

Women's Rights, (formerly known as the Women's Rights Task

Force), was established in 1980 as a section of the National

Conference of Black Lawyers. The National Conference of Black

Lawyers ("NCBL") is a non-profit corporation comprised of

lawyers, scholars, judges, legal workers, law students and legal

activists. NCBL has approximately 1,000 members and the Section

On Women's Rights has a membership of 100. The organization was

established to assist the black community in its struggle for

3

full economic, social and political rights. As an organizational

advocate against racism and sexism, NCBL has filed cases in the

various courts throughout the country to assist black citizens in

attaining the goals to which they are rightly entitled by law,

morality, and -justice. Toward that objective NCBL has partici

pated in lawsuits challenging unlawful employment practices and

procedures affecting blacks and women. The Women's Rights

Division has been particularly concerned with race and gender

eauality in the labor market since economic equality is of

paramount importance if women are to achieve equality in other

aspects of society.

5. All of amici have a particular interest and concern

with black women whos have suffered a double burden of discrimi

nation because of their race and sex. Across this nation, women

of all ages and from all races and ethnic background encounter a

common problem — sex discrimination. Women as a group suffer

from underemployment, or employment in sex segregated jobs which

offer low wages, few hiring benefits and limited opportunities to

advance. As severe as these problems are for all women, they are

even more severe for black women.

Black women have traditionally participated in the nation s

work force. As early as 1 890 forty percent of all black women

over the age of 10 were employed in non-farm occupations. By

1950 black female participation in the labor market had increased

4

to 46%, and this figure rose steadily to 49.5% in 1967, and to

53% in 1978. By 1983 more than seventy percent of black women

between the aoes of 25 and 44 were workers.

Despite the fact that millions of black women do work, they

continue to endure economic hardship, due to waqe discrimination

and job segregation. As early as 1919 black women, who were

compelled to work in inferior positions and perform the least

desirable tasks, were paid from ten to sixty percent less than

white women who themselves were poorly compensated. This was

true although black women wee oft-times more highly qualified

than whites. While all women experience an earning disadvantage

when compared to men, black women working full time earn less

then half of white men's earnings.

Much of this dilemma results from the fact that black women

were and still are concentrated or segregated in "occupational

shelters." Nearly sixty percent of all black women are employed

in only two major occupations, clerical and secretarial work.

Blacks ar over represented in jobs paying below minimum wages and

which in several instances pay below the poverty level. These

include jobs as laundry and dry cleaning; sewers/stichers;

dressmakers; produce handlers; welfare services aids; school

monitors; child care workers; and food counter workers.

Even in those occupations which hire large numbers of women,

black women tend to be relegated to the menial and lowest paying

positions. This phenomenon is not new. In the 1920's in the

5

tobacco industry black women were assigned to strip the tobacco

and received the lowest wages. This trend continues to persist.

For instance, the health industry, a primary employer of women,

employs 15% of white women, who generally work in physician's

offices and in specialized positions in hospitals, and 2 0% of

black women. Black women typically are concentrated in positions

outside of hospitals, such as nursing homes and home-based care

and receive poverty level earnings.

To the extent that black women have obtained an education or

skill, they are still denied employment opportunities which are

commensurate with their abilities and qualifications. Approxi-

matey twenty-five percent of black women are over-educated for

their jobs.

In order to rectify these inequities and to

equality in our society as required by the laws of

aimici urges this Court to affirm the opinion of the

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Amici adopt the Statement of the Case set forth

of plaintiffs/appellees AFSCME.

achieve full

this nation,

court below.

in the brief

6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The court below made a finding of fact of intentional

discrimination. This finding must be affirmed unless it is

clearly erroneous.

The courts dealing with claims of race discrimination in

wages have concluded that statistical proof of significant

disparities between salaries of black and white employees,

similar to that in the record below, establishes a prima facie

case. Moreover, these courts have rejected the market as a

defense where it represents the weak bargaining power of black

employees.

The authorities establishing methods of proof of intentional

discrimination in hiring and promotion also support the decision

below. Statistical proof of disparities in the treatment of

similarly situated black and white employees is sufficient to

shift the burden of proof to the employer to explain the dispari

ties .

Finally, on

the decision in

(5th Cir. 1982),

the issue of disparate impact, amici submit that

Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Co., 668 F.2d 795

is incorrect and should not be followed.

7

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court's Finding of Intentional Discrimination

Is Supported by the Applicable Legal Principles

Although pay equity has recently become a highly publicized

sex discrimination issue, it is important to note that invidious

wage discrimination and job segregation have long been practiced

against blacks and other disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups.

This discrimination has been documented in court decisions,

9 • 3Title VII's legislative history and the scholarly literature.

p . a . . EEOC v. Inland Marine Indust., 729 F.2d 1229 (9th

§rr;>,Hkt. denied, bi U.S.L.M. (bet. 2, 1984), Carpenter

V. SteoFerTF. Austin State Univ., 706 F. 2d 608, 625, $25-26 (5th

r-ir. 1 9 8 3 1 : James v. Stockhai Valves & F^t^inqs. n - p )3 1 0, 327 (5th Cir. 1 977), cert, denied, 434'U._5. iu34 (19 ),

Wade v. Mississippi Coop. Extension Serv.,528 F.2d 508, 514 16

Cir. 1976); Arkansas Educ. Ass’n v . of Educ., 446 F.2

763 (8th Cir. 1971); Morris v. Williams, 149 F.2d 703, 708 (8

Cir. 1945); Alston v. School Bd. , 1 12 F. 2d 992 (4th Cir.), cert._

denied, 9 n n .q. ft 9 “if 1941)) : Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp.

690, ~7l2 (D.D.C. 1981), aff'd in relevant part sub nom. Segar v.

Smith, 738 F.2d 1249 rn.C. Cir. 19»4); Vuyanich v. Republic N^ .J:

Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex. 1 9 8 0), vacated on othc~Sank, 505 F. Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex. nouj, on ot^ I

grounds, 723 F.2d 1195 (5th Cir. 1984); Wells v. Hutchinson, 499

F.' Supp. 174, 190-96 (E.D. Tex. 1980); Quarles v. Phillip nori;\sL.

Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Thompson v. Gibbes, 60 F.

Supp'. 872, 8 78 (E.D.S.C. 194 5).

See, e.g, S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong, 1st Sess. 6-7 ("Negroes are

"concentrated in the lower paying, less prestigous positions in

industry"); id. at 9-14; H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Conn. , 1st Sess.

4 ; id. at 17-19 (noting perpetuation of segregated 3 0b ladders by

sta~te and local governments); id̂ . at 23-24.

See, e.g., H. Northrup, R. Rowan, D. Barnum & J. Howard, Negro

Employment in Southern Industry, Part I at 33 (paper industry),

Part II at 36, 40, 55 (lumber industry), Part III at 25, 29-33,

39. 88 (tobacco industry), Part IV at 54-58 (coal mining

industry), Part Vat 60-68 (textile industry) ( 1970); 1 H. Hill,

Black Labor and the American Legal System, 98-99, 335-38, 352,

357-358 ( 1977); wachtel, The Negro and Discrimination in Employ

8

Because race-based and sex-based wage discrimination cases often

involve similar facts and legal theories, resolution of this case

will directly affect the effort to eradicate wage discrimination

against blacks.4 However, the issue raised by this case is not

whether Title VII requires equal pay for jobs of comparable

worth; the issue is whether defendants engaged in intentional

. . . . 5 discrimination.

In their effort to paint this case as depending on some

novel "comparable worth" theory, defendants ignore the crucial

issue of what types of evidence may be used to prove that a

defendant acted with intent to discriminate. On this issue, the

ment (1965).

Waae discrimination against blacks has been found in many cases

on the basis of evidence very similar to that Presentted in the

court below. See, ê g_., Carpenter, supra, 706 F 2d at 625 26

(5th Cir. 1983); Wade, supra, 528 F.2d at 514-16 (5th Cir. 1976),

Segar, supra, at 712, Vuyanich, supra .

The logical result of the arguments advanced by defendants is

that intentional racial discrimination in wages

Title VII only when black and white employees are being paid

differently for doinq exactly the same job. This narrow view of

intentional discrimination ignores the many complex and subtle

wavs in which employers can effectuate their invidious intent,

- m t is abundantly clear that Title VII tolerates no racial

discrimination, subtle or otherwise." McDonnell Pouqla|

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 801 (1973).. See“also Lynn v Regents_ot

Un iv. of California, 656 F.2d 1 337, 1 343 n.5 (9th Cir. 1 r

cert, denied, 459 oT s. 823 (1982); H.R. Rep. No. 238, supra, at

23-'24 (" [Discrimination of any kind based on factors no re

to job performance must be eradicated."). The Supreme Court has

already rejected the argument that Title VII prohibits wage

discrimination only when employees doing the same 3 0b are paid

unequally. County of Washington v. Guntner, 452 U.S. 161, 178

( 1981) .

9

race-discrimination jurisprudence provides substantial guidance.

In the discussion below, amici will focus on three sources of

such guidance: 1 ) cases considering claims of race-based wage

discrimination; 2 ) cases involving claims of race discrimination

in hiring and promotion; and 3) cases analyzing proof of inten

tional discrimination under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The District Court's Finding of Intentional Discrimina-

tion Is Entitled to Deference_____________________ ______

The court below made a finding of fact that.

"Implementation and perpetuation of the

present wage system in the State of Washington

results in intentional, unfavorable treatment

of employees in predominantly female job

classifications."

578 F. Supp. at 863. At the outset, we note that a trial court's

finding of the existence of discriminatory intent is entitled to

considerable deference. In Pullman-Standard v._Swint, 456 U.S.

273, 290-91 1982), the Supreme Court emphasized that "factfind

ing is the basic responsibility of district courts," in holding

that "a court of appeals may only reverse a district court's

finding on discriminatory intent if it concludes that the finding

is clearly erroneous under Rule 52(a)" of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure. Althouqh Swint involved a district court's

finding that the employer had not engaged in intentional discri-

10

mination, the clearly erroneous standard of review applies

equally to findings that the employer has discriminated. Id. at

289-90.6

B. The Decision Below Is Consistent with Precedents

Establishing Methods of Proof of Intentional

Discrimination__________ _________ _______________ ______

1 . The federal courts have frequently found inten

tional race discrimination in wages on the basis

of evidence similar to that in the record

The federal courts have for many years been adjudicating

claims of intentional race-based wage discrimination. The courts

in these cases have not found it necessary to invoke the "compar

able worth" label or to devise a separate "comparable worth"

theory. Instead, the courts have applied the same theories and

methods of proving wage discrimination that are used in cases

dealing with hiring, promotions, job assignments, discipline and

a host of other employment practices. See, e .g., Bonilla_v_.

Oakland Scavenger Co., 697 F. 2d 1 297, 1 301 (9th Cir. 1982), cert_._

denied, 52 U.S.L.W. 3906 (June 1 8 , 1 984) (prima facie case of

race—based wage discrimination can be established oy statistical

proof).

6 The Supreme Court has granted review in a case where the peti

tioner challenged "the Fourth Circuit practice in Title VII cases

of finding 'clear error' in all lower court findings of employ

ment discrimination." Petition for certiorari at 12, Anderson v.

City of Bessemer, No. 83-1623, cert. qr anted, 52 U.S.L.W. 3906

(June 19, 1984).

For example, in Pittman v. Hattiesburg Municipal Separate

School District, 644 F . 2d 1071 (5th Cir. 1981), a black printer

was paid substantially less than the white he had replaced. The

Court of Appeals held:

"To establish a prima facie case of racial

discrimination with respect to compensation,

the plaintiff must show that he was paid less

than a member of a different race was paid for

work requiring substantially the same respon

sibility."

644 F. 2d at 1 072. The court in Pittman also rejected the

employer’s argument that it had merely paid the wage set by the

market, stating "if the difference in labor value of a white

printer and black printer stems from the market place putting a

different value on race, Title VII is violated." Id_.

The courts have also found intentional discrimination in

situations where black employees performed different types of

work from the white employees to which they were compared. The

courts have typically based the findings of discrimination in

this factual situation on a showing that the jobs performed by

the black employees involved equal skill levels, education,

experience, responsibility and degree of supervision. For

example, in Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505,

509 (E.D. Va. 1968), the court compared the training, experience,

level of supervision and responsibility involved in the job of

casing attendant, always filled by a black, and the job of basic

12

machine operator, traditionally filled by a white, and concluded

that the lower salary for the casing attendant position resulted

from discrimination.

Although Quarles involved an individual determination of

discrimination, based on a one-on-one comparison between a black

and a white employee, statistical comparisons are generally used

to prove classwide disparate treatment in compensation. For

example, in Segar v. Civiletti, supra note 1, the court concluded

that plaintiffs established a prima facie case of discrimination

through the introduction of regression analyses that showed

"gross disparaties between the salaries of comparably qualified

black and white agents at DEA." Id . 8 Segar involved the

compensation of black and white agents of the Drug Enforcement

7 The caselaw includes numerous examples of the use of statistical

evidence to prove intentional classwide wage discrimination. In

Carpenter, supra, 706 F.2d at 626, the court implicitly recog

nized that a statistical disparity between the wages of black and

white employees constitutes proof of discriminatory intent where

the statistical study controls for the level of skill, education

and training. In Wade, supra, 528 F.2d at 514, 515-17, the court

approved of the use of! sophisticated multi—variate regression

analysis of salaries that showed "race to be a significant factor

in setting salaries." See also Wells v. Hutchinson, supra ̂ 499

F. Supp. at 190-96; EEOC v. Sandia Savings & Loan Ass'n, 24 Empl.

Prac. Dec. (CCH) H31.200 (D.N.M. 1980); Vuyanich, supra, 505 F.

Supp. at 285-87, 305 (plaintiffs established a prima facie case

of wage discrimination through introduction of statistical

studies that controlled for productivity factors, such as

education and experience, as well as Hay points).

8 Because the defendants did not adequately rebut this^ statistical

showing, the court concluded that "defendants have discriminated

against black agents as a class with respect to salary." 508 F.

Supp. at 712.

13

Agency. A wide variety of jobs are performed by agents, ranqing

"from administrative and supervisory duties to ... conducting

surveillance of suspected narcotics dealers and doing related

undercover work." Id. at 694. The evidence showed that blacks

were concentrated in undercover work, which involved greater

exposure to danger and hardship and less use of administrative

and supervisory skills. I<3. 705, 713.

In EEOC v. Inland Marine Industries, supra note 1, the Court

of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that plaintiffs had

established a prima facie case of wage discrimination "based on

statistical evidence that during the period in question no black

ever earned more than any white."

2 . The race—based wage discrimination precedents are

consistent with the analysis applied in hiring and

promotion cases

In Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 ( 1977) and

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977),

the Supreme Court established a method of proof of classwide

disparate treatment in hiring or promotion. Although Teamsters

and Hazelwood have been most frequently applied in the context of

hiring and promotion decisions, the race-based wage discrimina

tion cases easily fit into this method of proof. These cases

recoqnize that direct evidence of discriminatory motive rareiy

14

will be available and that is necessary and appropriate for

courts to draw inferences of discrimination from circumstantial

evidence. Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 416-18.

Teamsters held that statistical evidence is highly relevant

proof of employment discrimination, and in some cases may

standing alone establish a prima facie case. 431 U.S. at 339-40.

Once a prima facie case is established through use of statistical

evidence, "[t]he burden then shifts to the employer to ...

demonstrat [e] that the [plaintiffs'] proof is either inaccurate

or insignificant." 431 U.S. at 360. This is because "absent

explanation" statistical disparities are "a telltale sign of

purposeful discrimination." 431 U.S. at 339 n.20; see id_. at

360, n.4 6 .

Under Teamsters and Hazelwood, the plaintiff's initial

burden is to raise an inference of discrimination by ruling out

the most common nond i scr iminatory reason for the employer s

actions. Thus, in a hiring or promotion case, plaintiffs'

statistical evidence ordinarily must control for minimum objec

tive qualification. E. g . , Davis v. C3lifano, 613 F.2d 957, 964

(D.C. Cir. 1979).

The first question in applying Teamsters to wage discrimina

tion claims is what type of evidence olaintiffs must produce in

order to establish a prima facie case. Based on the case autho-

scholarly comment and the record and briefs in this case,

it appears that the two most commonly discussed explanations for

15

classwide wage differentials are differences in level of train

ing, education, skills, supervision and responsibility, ordina

rily measured by a job evaluation, and differences in market

value, purportedly measured by supply and demand. In appropriate

cases plaintiffs may establish a prima facie case by eliminating

differences in levels of training, skills and responsibility, as

a possible explanation of pay disparities . 9 Plaintiffs may

address this issue through a relatively simple one-on-one

comparison, as in Quarles, or through more sophisticated statis

tical analyses, such as those presented in Segar. This Court in

Heagney v. University of Washington, 642 P. 2d 1 157, 1 164-65 n . 6

(9th Cir. 1981), has explicitly concluded that job evaluation

studies establish "a standardized basis for comparing job content

with pay even though the job may be unigue" and thus "provide

some basis for making a meaningful comparison of male and female

jobs."

Where the employer has itself adopted a particular job

evaluation system, plaintiffs ordinarily should be permitted to

rely on that system in establishing their prima facie case. See

Gunther, 452 U.S. at 1 80-8 1 ( 1 98 1); Heagney, 642 F.2d at 1160,

1165-66. It is reasonable to rely on the employer's system in

9 In some situations, plaintiffs may establish a prima facie case

without controlling for all of these variables. See Segar,

supra, 508 F.2d Supp. at 696 & n.2; 712; Carpenter, supra, 706

F .2d at 625-26 (concluding that evidence supported finding of

discrimination in wages even though statistical study did not

control for level of skill, education and training) .

16

drawina the initial inference of discrimination. The employer

will then have the opportunity to explain why use of its system

is inappropriate.

The possibility of the labor market as an explanation for

wage disparities raises a more complex question. The labor

market can be analyzed as consisting of at least two components

-- the market for skills and the market for race or sex. On the

one hand, the market for skills reflects the supply and demand

for individuals qualified to perform the particular jobs to be

filled.^ On the other hand, courts have recognized that labor

markets have and continue to put a price on race and sex. As the

Fifth Circuit has stated, "... paying the going 'open market

rate can still violate Title VII if the market places different

values on black and white labor." Pittman, supra, 644 F.2d at

1 075 n.2. 1 1

In cases in which the black and white employees are doing

the same job, there can be no plausible argument that any market

rate differential is based on supply and demand of the particular

10 See, e.g., Briags v. City of Madison, 536 F. Supp. 435, 445 (W.

D. Wise. 1982).

11 See also Corning Glass Works v. Brennan, 417 U.S. 188, 205 ( 1 974)

TflndTng discriminatory a pay disparity that "arose simply

because men would not work at the low rates paid women inspec

tors, and ... reflected a job market in which Corning could pay

women less than men").

17

skills and courts have had no difficulty in attributing the pay

disparity to race. E.g. , Pittman, supra, 644 F.2d at 1 075; cf^

Cornina Glass, supra note 11, at 203-05 (sex discrimination).

In cases where the claim involves a comparison of employees

performing different types of jobs, a claim that the market for

skills explains a pay disparity between jobs using the same level

of skills, training, etc., has more plausibility. Nonetheless

amici suggest that the burden should be on the employer to raise

this explanation in its rebuttal. Placing this limited burden on

the employer is appropriate for several reasons.

First, none of the race—based wage discrimination cases has

required plaintiffs to prove that the pay disparity was not the

result of the market for skills in order to establish a prima

facie case. See pages 11 to 14 supra. Moreover, this court

in EEOC v. Inland Marine held that plaintiffs had established a

prima facie case by introducing statistical evidence of dispari

ties, without requiring plaintiffs to prove that the disparities

were not caused by legitimate market factors. 729 F.2d at 1234.

Second, the likelihood that race-based pay disparities are

caused by bona fide shortages of skills in the particular jobs

held by whites is not so great that plaintiffs should be required

to neaate this possible explanation in their prima facie case.

Pa j» t i c u 1 a r 1 y where plaintiffs have introduced statistical

evidence of a systemic race—based disparity across joos with the

same level of skills, education, training and responsibility, it

18

is unlikely that legitimate market shortage will explain the

disparity. There is simply no reason to believe that the bona

fide shortages of skilled individuals will more often occurr in

1 2jobs predominantly held by whites.

Third, the employer is in a better position to produce

evidence on the particular skills for which shortages exist and

the particular market it utilized in its search for workers with

those skills. As stated by the court in Briggs v. City of

Madison, supra, 536 F. Supp. at 446: "[i]f there is another,

nondiscriminatory reason for the wage disparity, such as the

employer's need to compete in the marketplace for employees with

particular qualifications, the employer is in the best position

to produce this information at trial."

Regardless of what the Court decides about which party bears

the burden of proof, certain types of evidence will be probative

on the question whether the market for skills explains a pay

disparity. Obviously, frequent deviations from the market rate

12 as stated by the court in Vuyanich, supra:

"[T]here is no reason to suppose that if an

employer has 100 jobs, and the same points

were assigned to 50 pairs of jobs (one job

predominantly white and the other predomi

nantly black), that it is always the 'black'

job of each pair that is valued lower in the

marketplace."

505 F. Supp. at 284, n.77.

19

or inconsistent application of such rate should be viewed as

strong evidence that the market for skills is not the real

, a. ... 13explanation for the disparity.

Another highly relevant factor is whether actual labor

shortages existed for hiahly paid positions. The existence of an

adequate supply of workers to fill highly paid, predominantly

white, jobs strongly suggests that the market for skills does not

explain the pay disparities. This is particularly true if blacks

were being turned down for such positions while incumbent whites

were being paid inflated wages.

Even if there were shortages of skilled individuals in some

predominantly white jobs, the court should still evaluate how

much of the overall disparity is explained in such shortages. See

Vuyanich, 505 F. Supp. at 284, 285 n.78, 306 n.96. Moreover, the

court should look at whether similar skills shortages existed for

jobs filled predominantly by blacks. A strong inference of

discrimination should be drawn where an employer pays high wages

when shortages exist in predominantly white fields but not when

shortages exist in predominantly black fields. Cf. McDonnell

Douglas, supra note 6 , 441 U.S. at 804 ; Hishon v. King^jS.

Spaulding, 52 U.S.L.W. 4627, 4629 (May 22, 1984).

13 As discussed in the brief for Plaint iffs/Appellees, it is clear

that defendants in this case used market data only in a minimal,

inconsistent, and arbitrary fashion.

20

Past or present workforce segregation or discrimination in

assignment of employees is a feature of many of the race-based

wage discrimination cases. The courts have found these practices

to be relevant even when the discriminatory assignments had

ceased and complaints based on these actions were time-barred.

Amici suggest that proof of past or current intentional segrega

tion or discriminatory assignment of employees tends to disprove

the skills' market explanation. In the absence of segregation or

discrimination in assignment, one might assume that employees

voluntarily chose their positions and that any disparities in the

compensation of black and white employees is the result either of

pure coincidence or of intangible features of certain jobs that

make them more desirable. However, where the employer has

previously or currently segregated its workforce or engaged in

intentional discrimination in placement, the individual choice

14 jn Quarles the employer had previously racially segregated its

workforce into all-white and all-black departments and paid flower

wages to black employees. 279 F. Supp. at 508-09. In 5e<^ar,

black agents were concentrated in undercover work. 508 F. Supp.

at 705, 713. In Vuvanich the court found that the employer has

engaged in racial discrimination in the placement of employees.

505 F. Supp. at 344. See also Carpenter, supra, 706 F.2d 608,

623-25 ( 5th Cir. 1983); Wade, supra, 528 F. 2d at 512-13 (5th Cir.

1975) .

21

explanation is negated. Moreover, such intentional segregation

itself affects the labor market, particularly when practiced by a

. 15large employer.

3 . Other indicia of discrimination exist in this

case

Although statistical evidence and the employer's explanation

of the disparities is usually the primary focus in disparate

treatment cases under Title VII, other factors may also tend to

prove the existence of discriminatory motive. In Village^of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Cor^., 429

U.S. 252 (1977), the Supreme Court outlined "without purporting

to be exhaustive, subjects of proper inquiry in determining

whether racially discriminatory intent existed," ^d. at 268.

Among the factors identified by the Court are the extent of any

disproportionate adverse impact upon black individuals and the

historic background of the action. 429 U.S. at 266-68.

15 we note that the evidence clearly shows that defendants in this

case created and maintained a sex segregated workforce and that

they relied on sex stereotypes in deciding how to index jobs.

15 Arlington Heights involved a challenge under the Equal Protection

Clause of: the fourteenth amendment to application of a local

zoning ordinance. Because a showing of discriminatory intent is

necessary to establish a violation of the Equal Protection

Clause, the Arlington Heights analysis is relevant to adjudica

tion of the issue of motive under Title VII.

22

Other courts have also elaborated upon this list of factors

that serve as indicia of discriminatory intent. Ind ividual

examples of discriminatory decision making serve to "bolster

[the] statistical evidence." Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 338;

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d 798, 817 (5th

Cir), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 1038 (1982); Wade, supra note 1, 528

F . 2d at 516-17.17 Similarly a history of discrimination is

probative of current discriminatory intent. Arlington Heights,

429 U.S. at 267; Payne, 673 F.2d at 817.

Moreover, subjective decisionmaking provides opportunities

to discriminate and therefore must be scrutinized very closely.

The Ninth Circuit has recently ruled that the greater the

subjective and discretionary element in an employer's decision,

the greater the possibility of racial bias, and therefore the

stronger the inference of intent in plaintiffs' prima facie case.

O'Brien v. Sky Chefs Inc., 670 F.2d 864, 867 (1982). Bee alsg

1 8Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972).

17 The record below includes numerous examples of reliance on

sex-based stereotypes in setting the compensation for particular

jobs. For example, defendants chose to index the Campus Police

Assistant (female job classification) to the predominantly female

clerical benchmark, rather than to the predominantly male

security guard benchmark. These examples of discriminatory

manipulation of the wage scales serve to "[bring] the cold

numbers convincingly to life," Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 339.

18 Subjective decisionmaking is particularly useful in reinforcing

statistical evidence. In the jury selection area the Supreme

Court has concluded that a prima facie case of intentional

discrimination is established where there is a statistically

significant disparity and there has been an opportunity to

discriminate at the point in the process where minorities were

23

A strong inference of intent can also be drawn from an

employer's failure to take remedial action upon becoming aware of

the racial impact of its practices. This Court stated in EEOC v^

Inland Marine, supra, 729 F. 2d at 1 235: "By refusing to change

his subjective wage-setting policies or to bring black wages in

line with those of whites [the foreman] ratified the existing

disparities. His ratification constituted all the intent the

court needed to find Inland Marine guilty on a disparate treat-

1 9ment theory."

The District Court's Finding that Defendants Illegally

Perpetuated the Effects of Prior Discrimination Is Supported

by the Applicable Legal Principles

The law is clear that a violation of Title VII exists where

defendant's employment practices perpetuate the effects of the

defendant's prior discriminatory conduct. In Quarles, supra, the

court found that the current low wages of certain jobs tradi

tionally performed by blacks represented an illegal "vestige of

the old policy under which Negroes were paid less for jobs

recruiring substantially equal responsibility." 279 F. Supp. at

adversely affected. The mere opportunity is sufficient, even

though "there is no evience that the commissioners consciously

selected by race." Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972).

19 gee also United Papermakers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 997

T5th~~cTF. 1Q69) , cert, denied "397 U.S. 919 ("70) ("The requisite

intent may be inferred from the fact that the defendants per

sisted in the conduct after its racial implications had become

known to them.").

24

509. A violation of Title VII occurred because, even though the

employer stopped discriminating in assignments, the pay disparity

between traditionally "black" and "white" jobs had not been cor

rected. Id.

The Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit applied the

perpetuation theory in International Union of Electrical Workers

v. Westinghouse Electric Corp., 631 F. 2d 1 094 (1980), cert^

denied, 452 U.S. 967 (1981). In that case plaintiffs alleged

that Westinghouse's present wage structure was derived from a

wage structure established in the 1930's, when the workforce was

segregated on the basis of sex and "female" jobs were paid less

than "male" jobs. 631 F . 2d at 1 097. The court concluded that

these facts, if proved, would establish a violation of Title VII.

Id. at 1098, 1107.

Finally, a recent race-discrimination case applying the

perpetuation theory is Liberies v. County of Cook, 709 F.2d 1122

(7th Cir. 1983). The defendant in that case had previously used

a college degree requirement and performance on a test to assign

employees to job categories, resulting in a predominantly black,

low-paid group of case aides and a predominantly white, high-paid

group of caseworkers. Even though the defendant had discontinued

use of the examination and degree requirement prior to the

effective date of Title VII,^ it had failed to equalize the

20 Title VII did not apply to public employers until March, 1972.

25

Id. at 1131. The court foundsalaries of the job categories,

that the defendants current compensation policy violated Title

VII. Id. at 1132-33.“1

The State of Washington deliberately perpetuated the effects

of its prior discrimination. Prior to 1972, sex segregation of

job categories was routine and "female" jobs were assigned less

pay then "male" jobs. The pre-existing pay disparities were

maintained after the State discontinued routine sex-based

segregation. For example, when a conflict existed between the

so-called market rate and maintaining the historic internal

relationship among jobs, defendants chose to maintain historic

relationships. In addition, defendants repeatedly chose to index

predominantly female jobs to predominantly female benchmarks,

even though the jobs being indexed were more similar to male

benchmarks.

21 The Court in Liberies treated plaintiffs' claiin under the

disparate impact theory. 709 F. 2d at 1 130-32. Amici recognize

that perpetuation of the effects of prior discrimination may be

illegal under the disparate impact theory. See Teamsters, supra,

431 U.S. at 349. ("One kind of practice fairin form, but

discriminatory in operation, is that which perpetuates the

effects of prior discrimination."). However, we note that

intentional perpetuation is also actionable under the disparate

treatment theory. See. Griffin v. County School Bd., 377 U.S.

218, 232 (1964).

Moreover, perpetuation of the effects of tne employer s own

prior discrimination should be actionable under the disparate

impact theory even if broader aspects of the impact theory do not

apply to compensation systems.

26

III. The Decision in Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Company Is

Incorrect and Should Not Be Followed

In the discussion below, amici do not address the ultimate

Question of whether and how the disparate impact theory of

liability should apply to a claim that a compensation system

violates Title VII solely because it has a disparate impact on

black or female employees. Rather, we suggest that however the

Court decides this guestion, the Court should reject the narrow

and unsupported interpretation of the disparate impact rule

enunciated in Pouncy v. Prudential Insurance Co., 668 F.2d 795

(5th Cir. 1 982 ). Adoption of Pouncy would affect not only wage

discrimination claims; it would also severely handicap attempts

to prove race discrimination in hiring, promotions and other

areas. Amici urge that Pouncy is wrongly decided and should not

be followed.

Po un cy involved a claim that an employer's promotion

practices were discriminatory under the disparate impact model of

proof.22 The court held that the disparate impact model may not

be used to challenge the cumulative results of an employer's

22 m Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 ( 1 971), the Court held

that Title VII "proscribes not only overt discrimination but also

practices that are fair in form but discriminatory in operation."

"What is reguired is the removal of artificial, arbitrary, and

unnecessary barriers to employment" that "operate as built-in

headwinds' for minority groups." Id. at 431 , 432. Under Griggs,

once the plaintiff establishes a disparate impact, the burden

shifts to the defendant to prove that its practices or procedures

are job-related. Id. at 431.

27

selection process, where that process includes two or more

components or stages. 668 F. 2d at 800. Second, the disparate

impact model is inapplicable to any subjective component of a

23selection process. Id_. at 801.

Defendants attempt to paint Pouncy as a well-established,

non-controversial doctrine. This is simply not true. Pouncy

represented a rejection of a long line of consistent Fifth

Circuit authority24 and since Pouncy a majority of the courts that

have considered the issue have rejected Pouncy.25 Moreover,

23 For example, if the results of the subjective interview stage of

a selection system can be shown to result in the rejection of a

significantly disproportionate number of black candidates, and

even if the interview is not job-related, plaintiffs must show

intent to discriminate in order to prevail.

24 Prior to the decision in Pouncy, the Fifth Circuit had consis

tently interpreted Griggs to apply to all hiring and promotion

devices and systems that produced a racially disproportionate

impact. See Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc_., 528 F.2d 419, 426-27

(5th Cir. 1980), remanded for further consideration, 451 U.S. 9U2

(1981), reaffirmed in relevant part, 657 F. 2 cl750 ( 1 981), £e_rt.

denied, 459 U.S~. 167 (1982); Crawford v. Western Elec. Co., Inc.,

6 14 T. 2d 1 300, 1 3 1 6-1 8 ( 5th Cir. 1 9 80 ); Rowe v. Gen. Motors

Coro., 457 F.2d 348, 354-59 (5th Cir. 1972), and by the Eighth

Circuit, Rule v. I.A.B.S.O.I., Local Union No. 396, 568 F.2d 558,

566 (8th Cir. 197 7)“.

v. Cleveland

Gilbert

25 The Sixth, Rowe

(1982), Eighth, ___

1 395-96; cert, denied ,

Hamed v. I.A.B.S.O.I.,

note TT; but see Harris, but see Harris v

(1981), Eleventh, Eastland

6 13, 6 1 9-20 (1 983) , cert

1984), and District of

1270-72 (1984), circuits have

Tenth Circuits have reached

Pouncy. See Pope v. City of

1982);

u Pheumatic Co., 690 F.2d 88, 93-95

v. City of Little Rock, 722 F.2d 1390,

55 U.S.L.W. 3828 (May 15, 1984); accord,

637 F.2d 506, 511-14 (1980); Rule, supra

Ford Motor Co., 6 51 F. 2<5 6"0 9 ~ 61 1

Tennessee Valley Auth., 704 F.2d,

d enied, 5"2 U.S.L.W. 36^1 (Feb. 28,

Columbia, Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249,

The Fourth and

consistent with

22 (4th Cir.

1982).

rejected ___

results that

Hickory, 679 F

Pouncy.

Mortensen v. Callaway, 672 F. 2d

are

2d 20,

822, 824 (10th Cir.

28

Pouncy has had an unstable existence even in the Fifth Circuit.

The disparate impact model of discrimination was articu

lated in Griggs v. Duke Power Co./ 401 U.S. 424 (1971). The

overriding concern of the Court in Griggs was the use of barriers

to employment that were not related to ability to do the job m

question. The Court did not differentiate between objective and

subjective barriers, but rather concluded that "Congress has made

[job] qualifications the controlling factor, so that race,

religion, nationality and sex become irrelevant." 401 U.S. at

436.^ Nowhere in the Griggs opinion does the Court even suggest

28that the rule is limited to objective practices.

Panels of the Ninth Circuit have reached conflicting

decisions on the issues raised by Pouncy. Compare Wane? v.

694 F.2d 1146, 1147-48 (1982) and Peters v. Lieuall

~F. 2d 966, 968-69 (1 982) with Spaulding v,

Washington, 740 F.2d 686, 707 (1984) and Heagney___________

Washington ̂ 642 F.2d 1 157, 1 163 (9th C i r . _ ^ 9 8 T T T ” See also Moore

v. Hughes Helicopters, Inc., 708 F.2d 4 7 5 , 481 82 & n.4 ( 1 9 8 3 )

Hoffman,

6TT Un iv .

en,

oF

~v~. Un iv. o?

26 Harrell

reaffirmed in

Compare

1982),

cert. denied" 459 U .S

Roebuck & Co., 708 F. 2d

Page v . U.S. Indust.,

1984).

Northern Elec

relevant part,

In Carpenter, supra,

the court stated its view "that

apply to subjective practices,

to follow Pouncy.

1 037 (1 982 )

183, 188-89 (5th

Inc., 726 F.2d

706

Co., 672 F.2d 444 (5th Cir.

679 F.2d 31 (5th Cir. 1982),

with Carroll v. Sears,

Cir. 1983). See also

1038, 1045-46 (5tE Cir.

F.2d at 620-21 (5th Cir. 1983),

the disparate impact theory should

However, the court felt compelled

27 jn fact, the Griggs opinion is replete with references to

"practices" and "procedures," terms that clearly encompass more

than isolated, objective components of the overall process.

E.a., 401 U.S. at 430 ("practices, procedures, or tests"); id. at

43” ("practice" ) ; id. at 432 ("employment procedures or testing

mechanisms"); id.T" any given requirement").

28 The Court in Pouncy apparently construed a reference in Griggs^to

facially neutral practices to exclude subjective practices. The

29

The broad reach of the disparate impact model of proof is

confirmed by the Court's decision in Connecticut v. Teal, 457

U.S. 440 (1982). The Court repeatedly emphasized that any

"barrier to employment opportunities," 457 U.S. at 447, 448, 449,

450, 45 1 , 453, can be challenged under the disparate impact

29model.

Subjective practices that are not job-related, such as

interviews and supervisory recommendations, are as capable as

written tests of operating as "barriers" or "built-in headwinds"

to minority advancement.^ Moreover, exclusion of subjective

phrase was used in connection with the Court's rejection of the

argument that Title VII proscribes only intentional discrimi-

nat ion:

"Under the Act, practices, procedures, or tests neutral

on their face, and even neutral in terms of intent,

cannot be maintained if they operate to freeze the

status guo of prior discriminatory employment prac

tices ."

401 U.S. at 430. When viewed in context it is clear that the

Court used the phrase "neutral on their face" to refer to

policies or practices that are not discriminatory on their face.

por example, a policy that blacks need not apply is facially

discriminatory, while a policy of using a review panel to make

selections is facially neutral.

29 Moreover, the dissenting Justices in Teal agreed that the process

is subject to the disparate impact model. [0]ur disparate

impact cases consistently have considered whether the results of

the employer's total selection process have an adverse impact

upon the protected groupT" 457 U.S. at 458 (Powell, Burger,

Rehnquist, O'Connor, J.J., dissenting).

30 ^ supervisor may give a good faith evaluation of an employee s

performance of a particular task. However, it is possible that

the ability to perform the task evaluated is not related to

performance of the job for which the candidate is applying.

Similarly, an interviewer may attempt to select the best appli-

30

practices from the reach of the disparate impact model of proof

is likely to encourage employers to use subjective, rather than

objective, selection criteria.

Limiting the disparate impact rule to isolated components of

a selection process also is inconsistent with Supreme Court

authority. The Court in Griggs and Teal repeatedly described the

disparate impact model as applying to "practices and procedures,"

31which clearly encompass the entire selection process or system.

Moreover, the legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title

VII leaves no doubt as to Congress' intent on his issue. The

1972 Senate Report noted:

Employment discrimination ... today is a ...

complex and pervasive phenomenon. Experts

familiar with the subject now generally

describe the problem in terms of 1 system' and

'effects' rather than simply intentional

wrongs."32

In Segar v. Smith, 738 F.2d 1249, 1270-72 (1984), the Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit concluded that it

cant, but because of lack of training and guidance, be incapable

of making a valid decision. Such practices serve as "artitifi-

cial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers to employment,

condemned in Gr iggs.

31 Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 349 and Pullman-Standard_Co.^ v_j_

Swint, ~s~upra, 4 56 U.S. at 276-77 (1 982), hold that a seniority

system would be subject to the disparate impact test but for §

703(h) of Title VII.

3 2 g. Rep. No. 415, supra note 2, at 5 (1971)

also H.R. Rep. No. 238, supra note 2, at

(emphasis added); see

8 (1971).

31

makes sense to apply the disparate impact theory to the bottom-

line results of multi-component selection process, articulating

3 3several reasons for rejecting the Pouncy approach. Other courts

have also articulated strong reasons for rejection of the

isolated component approach adopted in Pouncy. The Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit noted that an arbitrary disparate

impact might be caused by the interaction of two or more compo

nents of a selection process. Gilbert v. City of Little Rock,

supra note 25 , at 1 397-98 (1983). The rulings in Pouncy also

are inconsistent with the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selec

tion Procedures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607. The four federal agencies

charged with enforcing Title VII have interpreted the disparate

impact model to apply to the results of a multi-component

selection process and to all selection procedures, whether

. . .. 34objective or subjective.

33 7 3 8 f . 2d at 1 270-72. The court stated: "The employer will

possess knowledge far superior to that of the plaintiff as to

orecisely how its employment practices affect employees. This

fact ... justifies the lesser burden of requiring the employer to

articulate which of its employment practices adversely affect

minorities. ... [A] requirement that the plaintiff in every case

pinpoint at the outset the employment practices that cause an

observed disparity between those who appear to be comparably

qualified ... in effect permits challenges only to readily

perceptible barriers; it allows subtle bariers to continue to

work their discriminatory effects, and thereby thwarts the

crucial natinal purpose that Congress sought to effectuate in

Title VII. 738 F.2d at 1271-72.

34 29 C.F.R. § 1607.76.

32

CONCLUSION

Foe the reasons stated, amici respectfully urge that the

decision below be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIOS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

GAIL J. WRIGHT

PENDA D. HAIR

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

November 1984

33

Certificate of Service

I, Penda D. Hair, do hereby certify that copies of the fore

going Brief Amicus Curiae on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.; the National Association of Black

Women Attorneys; the National Bar Association, Women's Division;

and the National Conference of Black Lawyers, Section on Women s

Rights, were, this 16th day of November, 1984, served by first

class mail, postage prepaid, upon the following persons:

Winn Newman, Esq.

Winn Newman and Associates

1619 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20009

Christine 0. Gregoire

Deputy Attorney General

Temple of Justice, AV-21

Olympia, Washington 98504

Penda D. Hair

I

1

I