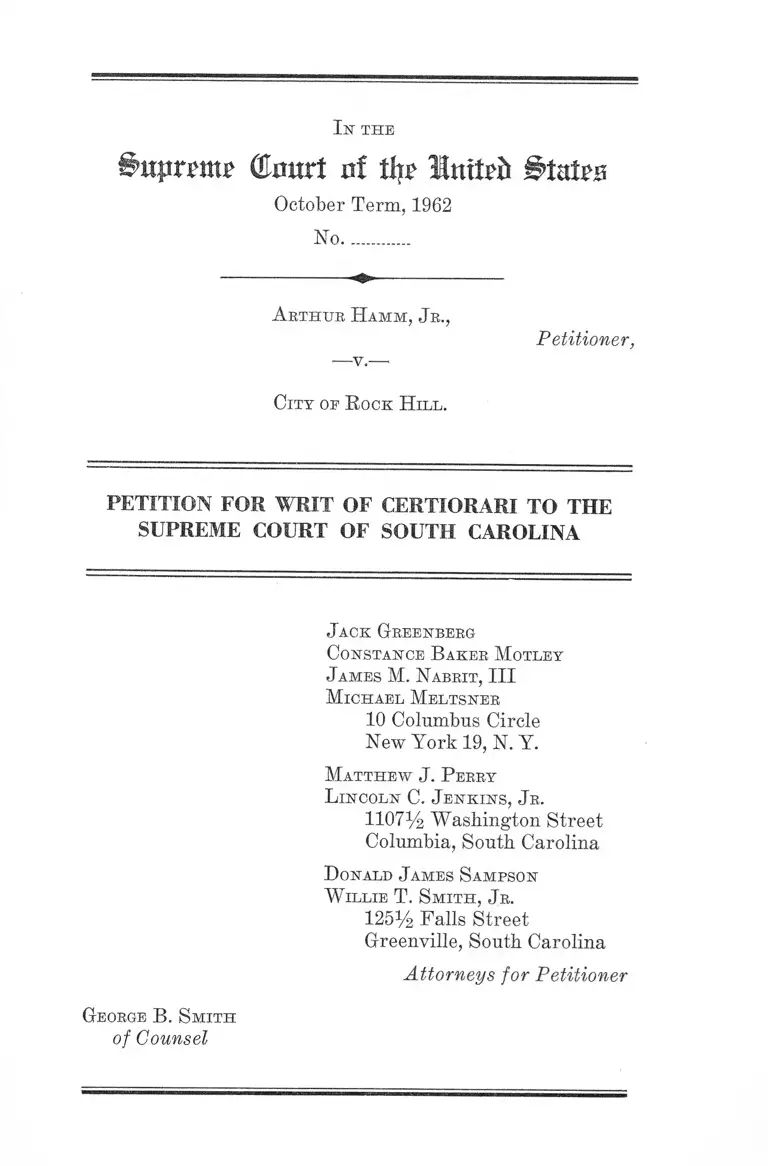

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamm v. City of Rock Hill Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1962. 1772d346-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3b461f2-3190-45f5-b6de-ac9a40de12e7/hamm-v-city-of-rock-hill-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I s r t h e

(E m tr t n f % £>ttxUs

October Term, 1962

No............

A r th u r H am m , J r .,

Petitioner,

—v.—

C ity oe R ock H il l .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack Greenberg

Constance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

M a tth ew J . P erry

L inco ln C. J e n k in s , J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

D onald J ames S ampson

W il l ie T. S m it h , J r .

1251/2 Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

George B . S m it h

of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below ........................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................... 1

Questions Presented ................................................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement ........................................................................ 4

How the Federal Questions Were Raised..................... 6

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................................... 7

I. The State of South Carolina Has Enforced

Racial Discrimination In Violation of the Equal

Protection and Due Process Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution .......................................................... 7

II. The City of Rock Hill Was Permitted to Prose

cute Petitioner Hamm for Violation of All the

“Available” South Carolina Law Including, But

Not Limited to, Three Vague Statutes with Dis

similar Provisions; He Was Sentenced and Con

victed for the General Offense of “Trespass”

Without Ever Being Informed of Which Stat

ute He Had Breached; All of Which Violated

His Rights Under the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment ...................................... 10

C o n c l u s io n ...................................................................... 17

A ppen d ix

Order of the York County Court ............................. la

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina 5a

Denial of Petition for Rehearing............ 11a

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Avent v. North Carolina, 253 N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47,

certiorari granted 370 U. S. 934 (1962) (No. 11,

October Term, 1962) .................................................. 9

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) ....... 8

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 II. S. 497 .................................... 8

Boman y. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1960) .............. 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ................. 7

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ................................ 7

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ................................................................................8,15

Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. 2d 512

(No. 89, October Term, 1962) ...........................6, 7, 9,13

City of Columbia v. Barr, 239 S. C. 395, 123 S. E. 2d

54 (No. 90, October Term, 1962) ............................ 7, 9

City of Columbia v. Bouie, 239 S. C. 570, 124 S. E. 2d

332 (No. 159, October Term, 1962) ............................ 7, 9

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ....................................... 8

Corson v. U. S., 147 F. 2d 437 (9th Cir. 1945) .............. 11

Edwards v. South Carolina,----- U. S .------ , 9 L. ed. 2d

697 .......... ...................................................................10,11

Fields v. South Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week 3297 .......... 10

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157................................ 8

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 .................................... 8

Greenville v. Peterson, 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d

826, certiorari granted 370 U. S. 935 (No. 71, October

Term, 1962) ............................................................. 6, 7, 9

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................. 8

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ......... ............... 12

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167..................................... 8

Pierce v. U. S., 314 U. S. 306 ............ ........................... 14

Screws v. United States, 325 U. S. 91 ............................. 8

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ...... ....................... .....8,10

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 16

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 - .......................... 8

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ................................ 15

Trustees of Monroe Avenue Church of Christ v. Per

kins, 334 U. S. 813 ...................... ............................... 10

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949) .............. 8

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 387 ..................... 16

I l l

PAGE

I n t h e

Supreme (Erwrt nt tkt

October Term, 1962

No............

A r t h u r H am m , J r.,

— v . —

C ity oe R ock H il l .

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

entered in the above entitled case on December 6, 1962,

rehearing of which was denied January 11, 1963.

Citation to O pinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

is reported at 128 S. E. 2d 907. It is set forth in the

Appendix hereto, infra p. 5a. The order of the York

County Court is unreported and is set forth in the Ap

pendix hereto, infra p. la.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered on December 6, 1962, infra p. 5a. Petition

for rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on January 11, 1963, infra p. 11a.

2

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257 (3), petitioner

having asserted below, and claiming here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner, a Negro, was denied due process

and equal protection of the law under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States by the

use of the state executive and judicial machinery to arrest

and convict him of trespass where he had attempted to

obtain service at a lunch counter previously reserved for

whites in a store entirely open to the public?

2. Whether petitioner was denied due process of law

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment in that the city was

not required to elect a statute under which to prosecute

but was permitted to rely on all the “available” law, in

cluding, but not limited to, three statutes which overlapped

but were not coextensive, and in that petitioner was con

victed and sentenced for the general offense of “trespass”

without ever being informed of which statute—or common

law rule—he had allegedly breached?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case also involves Section 16-386, Code of Laws

of South Carolina, 1952, as amended 1954:

3

Entry on another’s pasture or other lands after notice;

posting notice

Every entry upon the lands of another where any horse,

mule, cow, hog or any other livestock is pastured, or any

other lands of another, after notice from the owner or

tenant prohibiting such entry, shall be a misdemeanor and

be punished by a fine not to exceed one hundred dollars,

or by imprisonment with hard labor on the public works

of the county for not exceeding thirty days. When any

owner or tenant of any lands shall post a notice in four

conspicuous places on the borders of such land prohibiting

entry thereon, a proof of the posting shall be deemed and

taken as notice conclusive against the person making entry,

as aforesaid, for the purpose of trespassing.

3. This case also involves Section 16-388 (2), Code of

Laws of South Carolina, 1952, as amended 1960:

Any person:

(1) Who without legal cause or good excuse enters into

the dwelling house, place of business or on the

premises of another person, after having been

warned, within six months preceding, not to do so or

(2) Who, having entered into the dwelling house, place

of business or on the premises of another person

without having been warned within six months not

to do so, and fails and refuses, without good cause

or excuse, to leave immediately upon being ordered

or requested to do so by the person in possession, or

his agent or representative, shall on conviction, be

fined not more than one hundred dollars, or be im

prisoned for not more than thirty days.

4. This case also involves Section 19-12, Code of Laws

of City of Rock Hill:

4

Entry on lands of another after notice prohibiting

the same

Every entry upon the lands of another, after notice

from the owner or tenant prohibiting the same, shall

be a misdemeanor. Whenever any owner or tenant

of any lands shall post a notice in four conspicuous

places on the border of any land prohibiting entry

thereon, and shall publish once a week for four

consecutive weeks such notice in any newspaper

circulating in the county where such lands situate, a

proof of the posting and publishing of such notice

within twelve months prior to the entry shall be

deemed and taken as notice conclusive against the

person making entry as aforesaid for hunting and

fishing.

Statement

Petitioner Hamm, a Negro student, was arrested for a

sit-in demonstration at the lunch counter of McCrory’s

dime store in Rock Hill, South Carolina on June 7, 1960

(R. 14). He was convicted of trespass and sentenced to

pay a fine of $100.00 or spend thirty days in jail (R. 116).

Hamm, along with Reverend C. A. Ivory, a Negro, now

deceased, entered McCrory’s dime store on June 7, 1960 in

order to buy notebook paper and a trash can (R. 92). After

the purchases were made, Reverend Ivory suggested to the

petitioner that they eat at the lunch counter in the store

(R. 84, 85). Reverend Ivory testified that he had heard of

“one or two” Negroes who had “gotten some type of ser

vice” at the lunch counter (R. 94). Asked on cross-

examination whether he believed he could obtain service, he

replied, “yes” (R. 93, 94). Hamm seated himself on a stool

at the lunch counter and Reverend Ivory, a cripple, re

mained in his wheel chair at the counter (R. 15).

5

The Manager of the store, H. C. Whiteaker, saw Hamm

occupy a seat at the lunch counter and sent for a police

officer (E. 76). Two policemen arrived and in their presence

the manager asked Hamm and Reverend Ivory to leave

(R. 77). There is a conflict in the record as to whether or

not the police officer requested the manager to ask the two

to leave (R. 16, 26, 95). It is clear, however, that the man

ager asked them to leave because they were Negroes (R.

77, 78). Hamm and Ivory were peaceful and orderly at all

times and there was no question of offensive conduct

(R. 24, 79). The manager testified that it was the policy

of the store not to serve Negroes at the counter (R. 72).

However, he did not ask that the two Negroes be arrested

(R. 29).

McCrory’s is a nationwide chain store which has no

national policy with regard to segregation (R. 72). The

store in question is admittedly open to all people, including

Negroes (R. 71, 74). Thus, Negroes are free to purchase

items at any counter in the store other than the lunch

counter.

Petitioner Hamm, along with Reverend Ivory, was tried

and convicted of “trespass” in the Recorder’s Court of

the City of Rock Hill on June 29, 1960 and sentenced to pay

a fine of one hundred dollars ($100.00) or serve thirty (30)

days in prison (R. 1, 116). On December 29, 1961 the con

victions were affirmed by the York County Court, which

noted the death of Reverend Ivory.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina affirmed the con

viction of Hamm on December 6, 1962. Rehearing was de

nied on January 11, 1963.

6

H ow th e F e d e ra l Q u estio n s W ere R aised

At the commencement of the trial in the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Rock Hill, petitioner Hamm moved to

require the City of Rock Hill to elect one statute under

which to prosecute petitioner on the ground that pros

ecuting him under three separate statutes and all other

“available” South Carolina law without an election violated

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (R.

6). The motion was denied by the court (R. 13).

At the close of the prosecution’s case petitioner Hamm

moved for judgment of acquittal on the ground that the

State of South Carolina by supporting a private policy of

discrimination, violated the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 58, 59).

The motion was overruled (R. 64). This issue was raised

again and rejected at the conclusion of defendant’s case

by motion for a directed verdict (R. 98, 99); and after

judgment, by motion for arrest of judgment or, in the

alternative, for a new trial (R. 114).

On the appeal of petitioner Hamm and Reverend Ivory

to the York County Court, the court stated that the offense

of trespass had been stated with “reasonable and sufficient

particularity.” It stated that all other legal objections

had been properly overruled and, relying on City of Green

ville v. Peterson, 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d 826, certiorari

granted 370 U. S. 935 (No. 71, October Term, 1962), and

City of Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. 2d

512, certiorari filed April 7, 1962 (No. 89, October Term,

1962), affirmed the conviction of Hamm. The court also

noted the death of Reverend Ivory.

On appeal the Supreme Court of South Carolina re

jected Hamm’s contention that an election should have

been required, stating that no prejudice had resulted to the

7

appellant. It also rejected Hamm’s argument that his

arrest and conviction by state officials violated the Four

teenth Amendment, stating that “identical contention was

made, considered and rejected” in the cases of City of

Greenville v. Peterson, 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d 826,

certiorari granted 370 IT. S. 935 (No. 71, October Term,

1962); City of Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123

S. E. 2d 512, certiorari filed April 7, 1962 (No. 89, October

Term, 1962); City of Columbia v. Barr, 239 S. C. 395,

123 S. E. 2d 54, certiorari filed April 7, 1962 (No. 90,

October Term, 1962); City of Columbia v. Bouie, 239 S. C.

570, 124 S. E. 2d 332, certiorari filed June 5, 1962 (No. 159,

October Term, 1962).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I

The State of South Carolina has enforced racial dis

crimination in violation of the equal protection and

due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution.

Petitioner seeks a writ of certiorari to the Supreme

Court of South Carolina on the ground that his arrest and

conviction constitute state enforcement of racial discrim

ination contrary to the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The South Caro

lina Supreme Court rejected this contention stating that

“an identical contention was made, considered and re

jected” in similar sit-in cases, infra, p. 10a.

State action enforcing racial discrimination and segre

gation is condemned by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Shelley

8

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903.

Moreover, state supported racial discrimination which

bears no rational relation to a permissible governmental

purpose offends the concept of due process. Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1.

Action by judicial officers is included within the Four

teenth Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

Similarly, the amendment covers action by police officials.

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154; Garner v. Louisiana,

368 U. S. 157; Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167; Screws v.

United States, 325 U. S. 91. See also Baldivin v. Morgan,

287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961); Boman v. Birmingham

Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960); Valle v. Stengel,

176 F. 2d 697 (3d Cir. 1949).

Petitioner was arrested by a police officer of the City

of Rock Hill (R. 28) even though the manager of the store

did not request the arrest (R. 29). Indeed there is some

testimony that the manager of the store was asked by the

police to request petitioner to leave (R. 95). Even if the

police did not initiate the request it is at least clear that

they were enforcing a racially discriminatory policy of

the store which was itself the reflection of community cus

tom (R. 28). The manager testified, “I asked them to leave

because we do not serve Negroes at the lunch counter”

(R. 78). Such racial distinctions “are by their very nature

odious to a free people whose institutions are founded

upon the doctrine of equality.” Hirabayashi v. United

States, 320 U. S. 81, 100. “For the state to place its

authority behind discriminatory treatment based solely

on color is indubitably a denial by a state of the equal

protection of the laws, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment.” Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 U. S. 715, 727 (dissenting opinion).

9

Any contention that preservation of the institution of

private property requires the state to aid in the exclusion

of Negroes in a situation such as this is ill-conceived.

McCrory’s is a national chain store with no national policy

in regard to segregation (E. 72, 80). The manager testified

that the store itself was open to all members of the general

public including Negroes (E. 74). The lunch counter in

question was an integral part of McCrory’s operation.

The state involvement in the maintenance of segregation

in McCrory’s store is vividly brought out by reading the

arrest warrant. There the City of Bock Hill emphasized

that the lunch counter was “customarily operated upon a

segregated basis,” and that “racial tension was high due to

numerous recent prior demonstrations against segregated

lunch counters refusing service to members of the Negro

race of the defendant, both within the city and throughout

the south generally.” It is clear from the warrant that

state officials arrested Hamm not for any offensive conduct

on his part, but simply because he was a Negro.

Factual and legal issues like those raised in this case

are now before this Court in a number of cases, some of

which have been argued, Avent v. North Carolina, 253

N. C. 580, 118 S. E. 2d 47, certiorari granted 370 U. S. 934

(1962) (No. 11, October Term, 1962); Greenville v. Peter

son, 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. 2d 826, certiorari granted

370 U. S. 935 (No. 71, October Term, 1962), and some of

which are pending decision on petition for writ of certiorari,

City of Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. 2d

512 (No. 89, October Term, 1962) ; City of Columbia v.

Barr, 239 S. C. 395, 123 S. E. 2d 54 (No. 90, October Term,

1962); City of Columbia v. Bouie, 239 S. C. 570, 124 S. E.

2d 332 (No. 159, October Term, 1962). The last four cases

were relied on by the Supreme Court of South Carolina

in rejecting the constitutional objections raised by peti

tioner in this case.

10

When questions presented in a petition for writ of

certiorari are identical or similar to questions in another

case in which the court has already granted certiorari,

the issues involved in the petition are appropriate for re

view by certiorari. Compare Trustees of Monroe Avenue

Church of Christ v. Perkins, 334 U. S. 813, with Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

Compare Edwards v. South Carolina, ----- U. S. ----- ,

9 L. ed. 2d 697 and the disposition of Fields v. South

Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week 3297.

II

The City of Rock Hill was permitted to prosecute

petitioner Hamm for violation of all the “available”

South Carolina law including, but not limited, to, three

vague statutes with dissimilar provisions; he was sen

tenced and convicted for the general offense of “tres

pass” without ever being informed of which statute he

had breached; all of which violated his rights under

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Before the commencement of the trial in the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Rock Hill, petitioner Hamm asked the

prosecutor to inform him under which statute the warrant

had been drawn and on which statute the prosecution was

relying for a conviction. The prosecutor declined to do so

stating that the city “relies upon all the available law that

has a proper bearing upon a relationship to the offense

charged” (R. 6). The most he would reveal was that the

city, ‘‘amongst other things,” was relying on Section 16-386,

Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, as amended 1954;

Section 16-388 (2), Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

as amended 1960; and Section 19-12, Code of Laws of City

of Rock Hill (R. 8). He mentioned those “without waiving

11

the right to rely upon any other sections” and he stated

that Hamm could be found guilty of trespass “without

reference necessarily to what particular statute or ordi

nances he is charged under” (E. 11, 12). The Eecorder’s

Court supported the city in its refusal to be specific,

stating, “The warrant informs the defendant of what he is

charged . . . ” (R. 13).

Thus the city was allowed to prosecute Hamm for the

generic offense of trespass, bringing to bear the whole

body of “available” (R. 6) or “applicable” (R. 11) South

Carolina law including three specific statutes which, as

will be showm below, covered conduct which was in some

respects the same, in some respects different. Despite the

fact that “good pleading would unmistakenly inform the

accused as to the law he is alleged to have violated . . . ”

Corson v. U. 8., 147 F. 2d 437, 438 (9th Cir. 1945), Hamm

was forced to defend himself against an amorphous mass

of South Carolina law.

This mass of law may have included South Carolina’s

vague crime of breach of peace. See Edwards v. South

Carolina,----- - U. S .----- -, 9 L. ed. 2d 697, or even common

law trespass, for the warrant alleged a general state of

facts which could relate to any of the named statutes and

which appeared to include other elements. As the warrant

was phrased, it included not only elements of trespass, but

also elements of breach of peace. When it referred to high

racial tension, numerous anti-segregation demonstrations,

and recent trials of demonstrators on charges of breach

of peace, and when it implied that petitioner Hamm and

his companion were helping to create this tension, it in

troduced elements which could only confuse Hamm in his

defense. This confusion was compounded in the judge’s

charge to the jury. Here again it seemed that breach of

peace was made an essential element of Hamm’s crime.

12

The judge charged “trespass to property is a crime at

common law when it is accompanied by or tends to create

a breach of the peace. When a trespass is attended by

circumstances constituting breach of the peace, it becomes

a public offense, subject to criminal prosecution” (R. 103).

Both from the warrant and the charge to the jury, peti

tioner Hamm was justified in believing that if the state

could not prove that public disorder had been an element

in this situation, it had not proved its case.

Without specific knowledge of the statute he was charged

with violating, petitioner Hamm could not prepare an ade

quate defense for “It is the statute, not the accusation

under it, that prescribes the rule to govern conduct and

warns against transgression.” Lametta v. New Jersey, 306

U. 8. 451, 453. Certainly it is basic to due process that a

defendant should not be forced to guess what laws he is

charged with violating.

Petitioner Hamm’s rights were further denied because

he was not informed of what statute he had been convicted.

The jury simply found him guilty of the generalized of

fense of trespass (R. 112). The sentence of thirty days

in jail or one hundred dollars fine could be imposed under

Section 16-386, Section 16-388 (2), Section 19-12 of the

City Code, or some other “applicable” statute. The stat

utes mentioned by the prosecutor prohibited dissimilar

conduct. Hamm had no way of knowing how the prose

cution met its burden of proving violation of a statute.

Nor did he know whether he was convicted of violating

an unconstitutional statute. This defect of not knowing

the statute he allegedly breached was not cured by the

fact that Section 16-388 (2) was one of the things read

when the Recorder attempted to define trespass for the

members of the jury (R. 102). Petitioner was neither

found guilty of any particular statute or statutes nor was

he acquitted of any others.

13

Petitioner’s difficulties were enhanced because those

statutes which were mentioned as outlawing his conduct,

on their face, outlawed dissimilar conduct, so that trespass

under the one might not be trespass under the other.

While Section 16-386, Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1952 and Section 19-12, Code of Laws of City of Rock Hill

are similar, Section 16-388 (2), Code of Laws of South

Carolina, 1952, as amended 1960, is substantially different.

Section 16-386 and Section 19-12 prohibit entry on lands

of another only “after notice from the owner or tenant

prohibiting such entry.” The notice can be given by post

ing notices on the borders of land. Section 16-386 on its

face applied only to farm land and, at the time of the trial

in this case it had never been construed as requiring a per

son who entered a business at the invitation of the owner

to leave when asked.1

Section 16-388 (2) on its face prohibits conduct com

pletely unlike that prohibited by Section 16-386. It re

quires :

(1) That a person enter a place of business. (2) That

he be requested by the person in possession or his agent

or representative to leave. (3) That he refuse to leave.

(4) That he have no good cause or excuse for his refusal

to leave.

Thus Section 16-386 and Section 19-12 on the one hand,

and Section 16-388 (2) are different in at least four re

spects. First of all the conduct prohibited by Section 16-

386 and Section 19-12 is entry after notice, not as in Sec

tion 16-388 (2) remaining after notice. Secondly, while

1 City of Charleston v. Mitchell, 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. 2d 512,

certiorari filed April 7, 1962 (No. 89, October Term, 1962), which

expanded Section 16-386 to include conduct like that of this peti

tioner, had not yet been decided by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina when this case was tried.

14

all three statutes make provision for actual notice, both

Section 16-386 and Section 19-12 provide for constructive

notice. Thirdly, when actual notice is given under Section

16-386 or Section 19-12 it must be given by the “owner or

tenant,” not by “the person in possession, or his agent or

representative” as in Section 16-388 (2). Finally, there

is no “good cause or excuse” requirement in Section 16-386

and Section 19-12 as there is in Section 16-388 (2). Hamm

was therefore placed in the unfair position of defending

against the whole body of “available” South Carolina law

including specified statutes which prohibited dissimilar

conduct.

In addition to being forced to defend himself without

knowing under which statute or ordinance he was charged,

the particular statutes and ordinances mentioned by the

prosecutor as possibly providing a basis of conviction all

contain vague and ambiguous provisions.

Both Section 16-386 and Section 19-12 of the Code of

Laws of City of Bock Hill prohibit “entry” on another’s

land “after notice” from the owner or tenant. However,

Negroes, including Hamm, were welcome to enter the store.

Hamm was convicted only by expanding the words “entry

after notice” to “remain after notice.” 2 But it is well

settled that “judicial enlargement of a criminal act by

interpretation is at war with the fundamental concept of

the common law that crimes must be defined with appropri

ate definiteness.” Pierce v. U. 8., 314 U. S. 306, 311.

Section 16-388 (2) is also unconstitutionally vague when

applied in this situation. It states that a person must leave

the premises when asked unless he has good cause or excuse

not to leave. Nowhere in Section 16-388 (2) are the words

“good cause or excuse” defined. No standards are set out

2 See footnote 1.

15

by which Hamm and others similarly situated could know

what amounts to “good cause or excuse.” Certainly, in a

store open to the public, including Negroes, where Hamm

has purchased items and where he is orderly in every way,

he should expect that he has “good cause or excuse” not

to leave. In his instructions to the jury, the City Recorder

stated that “good cause or excuse” meant “one valid in

the eyes of the law, and under existing circumstances, not

merely a personal cause or excuse of insufficient stature

to have any legal force” (R. 104), but he refused to charge

that race could not be the basis of a violation of the stat

utes (R. 105, 106). But if as a matter of law a Negro has

no “good cause” to request service at a “whites only coun

ter” the statute runs afoul of Mr. Justice Stewart’s con

demnation of legislative enactments “authorizing discrim

inatory classification based exclusively on color.” Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715, 727 (con

curring opinion). The vice in this section lies not only in

the fact that the legislature has set no guidelines to deter

mine the breach, but also in the fact that it has given such

power to the manager of a store, permitting him to use the

arbitrary classification of race as a basis for violation.

“That the terms of a penal statute creating a new offense

must be sufficiently explicit to inform those who are subject

to it what conduct on their part will render them liable to

its penalties, is a well-recognized requirement, consonant

with ordinary notions of fair play and the settled rules of

law. And a statute which either forbids or requires the

doing of an act in terms so vague that men of common

intelligence must necessarily guess at its meaning and

differ as to its application violates the first essential of

due process of law.” Connally v. General Construction Co.,

269 IT. S. 385, 391.

In the case of Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, a pro

vision similar to this one was held to be too vague to

16

warrant a conviction of the accused. In that case a state

statute said that any person who “without a just cause or

legal excuse therefor” loitered about or picketed the place

of business of another person could be imprisoned. The

Court condemned the use of the words “without a just cause

or legal excuse” saying that they did “not in any effective

manner restrict the breadth of the regulation” ; and that

“the words themselves have no ascertainable meaning either

inherent or historical” (310 U. S. at 100). Under this rea

soning Section 16-388 (2) must also be held too vague to

meet the requirements of fair notice.

Moreover, if it cannot be known from the record whether

or not a defendant was convicted under an unconstitution

ally vague statute, the conviction cannot stand because of

the indeterminate possibility that it was premised on

another provision of law not subject to the same infirmity.

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 368. In Stromberg

the court, noting that the defendant had been convicted

under a general jury verdict which did not specify which

of three statutory clauses it rested on, concluded that “if

any of the clauses is invalid under the Federal Constitu

tion, the conviction cannot be upheld.” The principle was

followed in Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 387, 392,

when the court said:

“To say that a general verdict of guilty should be up

held though we cannot know that it did not rest on the

invalid constitutional ground on which the case was

submitted to the jury would be to countenance a

procedure which would cause a serious impairment of

constitutional rights.”

Certiorari should be granted for the additional reason

that the City of Rock Hill, by burdening defendant with

the whole body of “available” South Carolina law, by speci-

17

fying only statutes which were dissimilar and too vague

to give Hamm notice that they prohibited his conduct, and

by convicting him of the generalized offense of trespass

without reference to a particular statute, violated Hamm’s

rights under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted that the petition for writ of eertiorari should

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

J ames M. N abrit, III

M ich a el M eltsnbr

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

M a tth ew J. P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

D onald J ames S ampson

W il l ie T. S m it h , J r .

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

George B . S m it h

of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

IN THE YORK COUNTY COURT

C ity of R ock H il l ,

A r th u r H am m , J r.

appeal from t h e recorder’s court of t h e

CITY OF ROCK HILL

Order

This Court now has before it for consideration a total of

seventy-one cases which were heard by the Recorder’s

Court for the City of Rock Hill. The convictions of all

defendants were in due time appealed to this Court and

heard together by this Court on an agreed Transcript of

Record. By occurrence and charge the cases are grouped

as follows:

1. Sixty-five breach of peace charges, upon the public

streets at City Hall, on March 15, 1960.

2., Three breach of peace charges, upon the public

streets at Tollison-Neal Drug Store, on February 23,

1961.

3. One Trespass charge within McCrory’s variety

1 store, on April 1, 1960, before enactment of the 1960

Trespass Act (No. 743).

4. Two Trespass charges, within McCrory’s variety

store, on June 7, 1960, after enactment of the 1960

Trespass Act.

2a

An examination of the Transcript of Record on Appeal

discloses no real distinction between the first sixty breach

of peace cases at City Hall, the next five on the same day

at the same place only a short time later, and the three

breach of peace cases on the public streets at Tollison-Neal

Drug Store. In all of these cases it appears from the record

that the public peace was endangered, that the defendants

were properly forewarned by a police officer to cease and

desist from further demonstrations at that time and place,

and move on, which they failed and refused to do, despite

allowance of ample time within which to have complied

with the order, and that thereafter they were arrested and

charged with breach of peace as continuance of their activi

ties under the circumstances then existing, as shown by the

record, constituted open defiance of proper and reasonable

orders of a police officer and tended with sufficient direct

ness to breach the public peace.

The offense charged in each of the sixty-eight breach of

peace cases is clearly made out under the facts shown by

the Transcript of Record and the law of force in this state,

particularly as the law is shown by the recent decision of

the South Carolina Supreme Court in the case of State

v. Edwards et al., Opinion No. 17853, filed December 5,

1961.

In like manner this Court finds no distinguishing features

between the one trespass case, which occurred at one time

and place and the two later trespass cases at the same

place. In all three cases each defendant was asked to leave

the premises by the Manager of the store, this occurred in

the presence of a city police officer, who then himself re

quested each defendant to leave and explained that arrest

would follow upon failure to leave. After each defendant

Order

Order

failed to leave the private premises involved, following

allowance of a reasonable opportunity after request so to

do, first by the Manager and then by the police officer, each

defendant was arrested and charged with trespass. Here

again, under the facts disclosed in the record and the law

of force in this state, the charge of trespass is properly

made out as to each defendant. See City of Greenville v.

Peterson et al, S. C. Supreme Court Opinion No. 17845,

filed November 10, 1961, and City of Charleston v. Mitchell

et al, S. C. Supreme Court Opinion No. 17856, filed Decem

ber 13,1961.

A number of specific legal questions were raised by the

Defendants, including particularly a question as to ade

quacy and sufficiency of the warrants and whether or not

the Defendants were properly advised of the charges pend-

ing against them. An examination of the warrants dis

closes that in each case the facts constituting the offense

charged were stated with reasonable and sufficient par

ticularity. It is the opinion of this Court that the various

legal objections raised in the court below, which are not

set forth in detail herein, were properly overruled. See

State v. Randolph et al, 239 S. C. 79, 121 S. E. (2d) 349,

filed August 23, 1961, other authorities cited herein, and

other applicable decisions of our Courts referred to in the

cited authorities.

Accordingly, it is hereby ordered and decreed that the

convictions by the Recorder’s Court of the City of Rock

Hill in all of the seventy-one cases under appeal are hereby

affirmed, and each of the cases is remanded for execution of

sentence as originally imposed.

This Court takes note, from published reports, of the

untimely death of the Defendant, Rev. C. A. Ivory, since

4a

hearing of the appeals herein and before rendering judg

ment thereon.

All of which is duly ordered.

G eorge T. Gregory, J r.,

Residing Judge, Sixth Judicial Circuit.

Chester, S. C.,

December 29,1961.

Order

5a

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

I n t h e S u pr em e Court

Opinion by Moss, A.J.

City oe R ock H il l ,

Respondent,

—v.—

A r th u r H am m , J r .,

Petitioner.

APPEAL PROM YORK COUNTY, GEORGE T. GREGORY, JR., JUDGE

Moss, A.J . :

Arthur Hamm, Jr., the appellant herein, was convicted

in the Recorder’s Court of the City of Rock Hill on June

29, 1960, of the charge of trespass, in violation of Section

16-388 (2) as is contained in the 1960 Cumulative Supple

ment to the 1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina. The

judgment of conviction was affirmed on December 29, 1961,

by the Honorable George T. Gregory, Jr., Resident Judge

of the Sixth Circuit. This appeal followed.

The evidence shows that on June 7, 1960, the appellant,

along with Rev. C. A. Ivory, now deceased, entered the

premises of McCrory’s Five and Ten Cent Store in the

City of Rock Hill, South Carolina. Ivory was a cripple and

confined to a wheelchair. He was pushed into the store by

the appellant. Ivory and the appellant proceeded down the

aisles of the store and made one or two purchases. There

after, they proceeded to the lunch counter operated by

6a

McCrory’s. Ivory, still in his wheelchair, came to a stop

between the stools at the said counter. The appellant took

a seat on a stool at the lunch counter. The appellant and

Ivory sought to be served. They were not served and were

asked to leave the lunch counter. Upon their refusal to

leave at the request of the manager of McCrory’s store,

they were placed under arrest by police officers of the City

of Rock Hill.

The first question for determination is whether the City

Recorder committed error in refusing to require the City

of Rock Hill to elect whether the prosecution was under

Section 16-386 or Section 16-388, Code of Laws of South

Carolina, or Section 19-12, Code of Laws of the City of

Rock Hill.

It should be borne in mind that the warrant charged the

appellant with committing a trespass on June 7, 1960, and

that he,

“did willfully and unlawfully trespass upon privately

owned property by remaining along with one Rev. C. A.

Ivory at the lunch counter in McCrory’s variety store,

which is customarily operated upon a segregated basis,

and refusing to leave said counter, after the manager

of said store, in the presence of City Police Capt. John

M. Hunsucker, Jr., advised him he would not be served

and specifically requested him to leave said lunch coun

ter, and after the aforesaid police officer thereupon

advised him that he would be arrested for trespass

unless he left said premises as directed, which he never

theless failed and refused to do, * * * .”

The appellant asserts that under Section 15-902 of the

1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina that whenever a per

son is accused of committing an act which is susceptible of

Opinion by Moss, A.J.

Opinion by Moss, A.J.

being designated as several different offenses that the

Municipal Court upon a trial of such person shall be re

quired to elect which charge to prefer and a conviction of

an offense upon such an elected charge shall be a complete

bar to further prosecution for the alleged offense. An

examination of the warrant here shows that the only offense

charged against the appellant was that of a trespass and

the warrant above quoted, in our opinion, charges a viola

tion of Section 16-388 of the 1960 Cumulative Supplement

to the Code, which provides tha t:

“Any person:

“ (2) Who, having entered into the dwelling house, place

of business or on the premises of another person * * *

and fails and refuses, without good cause or excuse,

to leave immediately upon being ordered or requested

to do so by the person in possession, or his agent or

representative,

“Shall, on conviction, be fined not more than one hun

dred dollars, or be imprisoned for not more than thirty

days.”

The warrant under which the appellant was prosecuted

plainly and substantially sets forth the acts of the appel

lant and thus informed him of the nature of the offense

against him, in accordance with Section 43-111 of the 1952

Code. City of Charleston v, Mitchell, et al., 239 S. C. 376,

123 S. E. (2d) 512, and City of Greenville v. Peterson, et al.,

239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. (2d) 826.

This case was tried by the Recorder of the Municipal

Court of Rock Hill, with a jury. The Recorder, in deliver

ing his charge to the jury, gave the following instructions:

8a

“Now, this defendant is charged under a warrant issued

by the city of Kock Hill with the offense of trespass.

I am not going to read this warrant to yon. It has

been read to you and it has been discussed, and you

know what is in the warrant. If you want to know

then what is meant by trespass, what does trespass

mean, I am going to read to you a portion of an Act

of the General Assembly which became law on the 16th

day of May, 1960, reading you only a portion of it,

and that portion which applies in this particular case.

“Any person who, having entered into a place of busi

ness or on the premises of another person, firm, or

corporation, and fails and refuses without good cause

or good excuse to leave immediately upon being ordered

or requested to do so by the person in possession, or

his agents or representatives, shall on conviction be

fined not more than $100.00 or be imprisoned for not

more than thirty days.”

It is readily apparent that the Recorder submitted to

the jury only the question of whether the appellant was

guilty of the offense of trespass as is defined by an Act of

the General Assembly, approved May 16, 1960, 51 Stats.

1729, now incorporated in the 1960 Supplement to the Code

as Section 16-388 (2).

Should the City Recorder have required an election by

naming the statute under which the prosecution was

brought? We think not. The warrant here charged a single

offense of trespass upon facts which are not in dispute.

In 27 Am. Jur., indictments and informations, Section 133,

at page 691, we find the following:

“ * * * There need, of course, be no election where the

indictment or information charges only one offense

Opinion by Moss, A .J.

Opinion by Moss, A.J.

and the several different counts are merely variations

or modifications of the same charge. This rule has

been applied to an indictment where an unlawful act-

relied on by the state as the basis for the charge was

made unlawful by more than one statute, it being held

that in such case it is error to compel the state to elect

upon which statute it relies for a conviction. * * *

State v. Schaeffer, 96 Ohio St. 215, 117 N. E. 220.

In 42 C.J.S., Indictments and Informations, Section

185, at page 1149, we find the following:

“ * *'* No election is necessary where the indictment,

properly construed, charges but one offense although

several acts comprising the offense are included, or

several methods by which the offense may have been

committed are stated. The prosecuting attorney is not

required to state at the trial the particular section of

the code under which accused is being tried where the

offenses or acts with which accused is charged are

fully set out, nor is he required to elect where the

offenses defined by the various statutes are included

within the crime charged, * # #

And again:

“ * * * Although no express statement of election is

made by the prosecution, accused is not prejudiced

where the trial in fact proceeds on only one charge, or

appropriate instructions are given to the jury. * * *

There is nothing substantial in the objection that the

City Recorder refused to require the city of Rock Hill to

elect the particular statute upon which the prosecution was

based. The warrant charged a single offense of trespass

10a

and the Eecorder submitted to the jury only the question

of whether the appellant was guilty of trespass as such

was defined in the statute heretofore cited. There was no

prejudice to the appellant.

The record shows that the appellant and the Eev. C. A.

Ivory are Negroes. It was the policy of McCrory’s store

not to serve Negroes at its lunch counter. The appellant

asserts by exceptions 3, 4 and 5 that his arrest by the police

officers of the city of Eock Hill and his conviction of tres

pass that followed was in furtherance of an unlawful policy

of racial discrimination and constituted State action in

violation of his rights to due process and equal protection

of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

State Constitution. Identical contention was made, con

sidered and rejected in the cases of City of Greenville v.

Peterson, et al., 239 S. C. 298, 122 S. E. (2d) 826; City of

Charleston v. Mitchell, et al., 239 S. C. 376, 123 S. E. (2d)

512; City of Columbia v. Barr, et al., 239 S. C. 395, 123

S. E. (2d) 521; and City of Columbia v. Bouie, et al., 239

S. C. 570, 124 S. E. (2d) 332, in each of which was involved

a sit-down demonstration similar to that disclosed by the

uncontradicted evidence here, at a lunch counter in a place

of business privately owned and operated, as was McCrory’s

in the case at bar.

All exceptions of the appellant are overruled and the

judgment appealed from is affirmed.

Affirmed.

T aylor, C.J., L ew is a n d B railsford, JJ., concur. B ussey ,

A.J. d id n o t p a r tic ip a te .

Opinion by Moss, A.J.

11a

Petition for Rehearing and Petition for

Stay o f Remittur

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

I n t h e S u pr em e C ourt

Case No. 4912

C ity oe R ock H ill ,

Respondent,

A r t h u r H am m , J r .,

Appellant.

Supreme Court of South Carolina

Clerk’s Office, Columbia, S. C.

Filed December 17,1963

Frances H. Smith, Clerk

Petition denied.

Supreme Court of South Carolina

Clerk’s Office, Columbia, S. C.

Filed January 11,1963

Frances H. Smith, Clerk

C. A. T aylor, C. J .

J oseph R . M oss, A .J .

J . W oodrow L ew is , A .J .

J . M. B railsford, A .J .

38