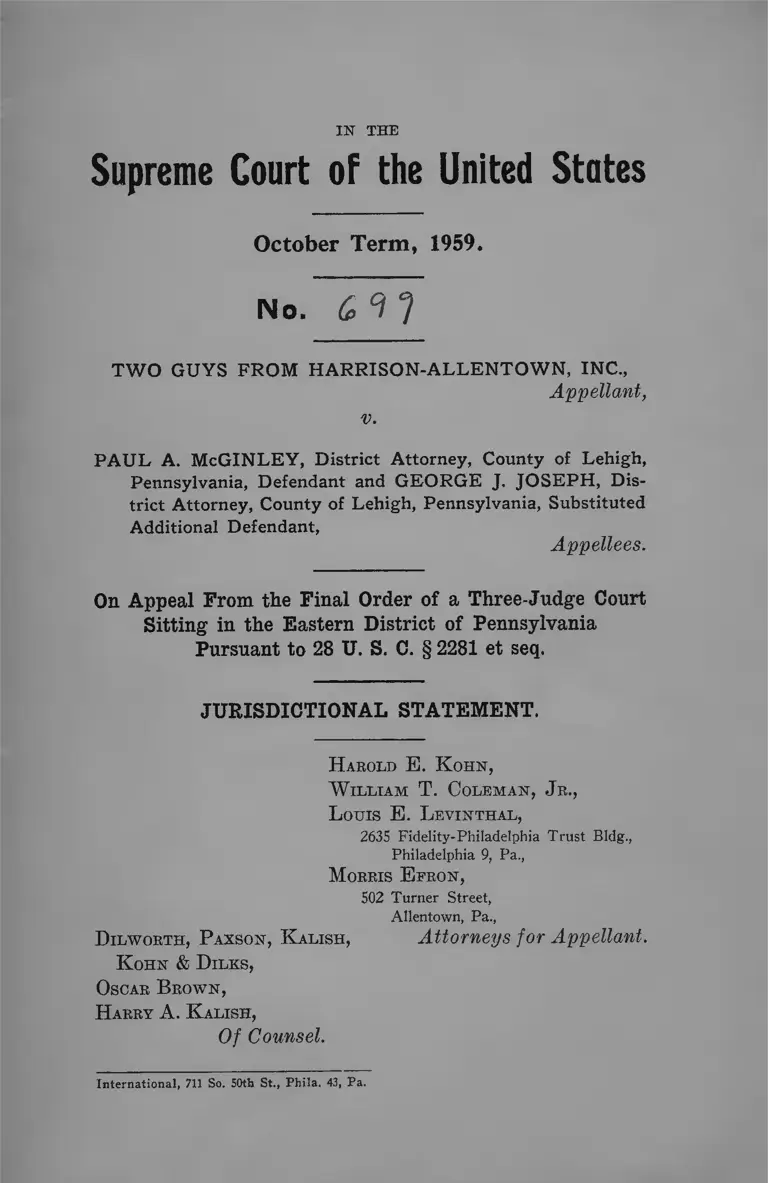

Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

February 11, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley Jurisdictional Statement, 1960. 74cd1515-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3b928f0-efba-4188-9ec6-f5c224c1ea1e/two-guys-from-harrison-allentown-inc-v-mcginley-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1959.

No. 6 ^ 7

TWO GUYS FROM HARRISON-ALLENTOWN, INC.,

Appellant,

V.

PAUL A. McGINLEY, District Attorney, County of Lehigh,

Pennsylvania, Defendant and GEORGE J. JOSEPH, Dis

trict Attorney, County of Lehigh, Pennsylvania, Substituted

Additional Defendant,

Appellees.

On Appeal From the Final Order of a Three-Judge Court

Sitting in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

Pursuant to 28 U. S. 0. § 2281 et seq.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT.

H arold E . K o h n ,

W il l ia m T. C o l e m a n , J r.,

L o u is E . L e v in t h a l ,

2635 Fidelity-Philadelphia Trust Bldg.,

Philadelphia 9, Pa.,

M orris E f r o n ,

S02 Turner Street,

Allentown, Pa.,

D il w o r t h , P a x s o n , K a l is h , Attorneys for Appellant.

K o h n & D il k s ,

O scar B r o w n ,

H arry A. K a l is h ,

Of Counsel.

International, 711 So. SOtii St., Phila. 43, Pa.

INDEX.

Page

A. Opinions Delivered in the Court B e lo w .................................. 1

B. Statement of the Grounds on Which Jurisdiction Is Invoked ; 2

C. Statutes Involved ......................................................................... 3

D. Questions Presented ..................................................................... 4

E. Statement of the C a se .................................................................. 7

F. The Federal Questions Are Substantial, Were Wrongly De

cided Below, and Are of Great Public Importance........... 14

Conclusion ............................................................................................ 23

Appendix A—Opinion, Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown,

Inc. V. McGinley, U. S. D. C., E. D. Pa., Civil Action

No. 25626 ................................................................................... la

Appendix B— Supplementary Findings of Fact in the Same Case 20a

Appendix C—Opinion, Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown,

Inc. V. McGinley, U. S. C. A .(3 ) No. 13,096 ................... 23a

Appendix D— Final Order, Two Guys from Harrison-Allen

town, Inc. V. McGinley, U. S. D. C., E. D. Pa., Civil Action

No. 25626 ................................................................................... 24a

TABLE OF CASES CITED.

Page

19

19

Allen V. Colorado Springs, 101 Colo. 498, 75 P. 2d 141 (1938)

Arrigo v. City of Lincoln, 154 Neb. 537, 48 N. W. 2d 643

(1951) ..........................................................................................

Bargaintown, U. S. A., Inc. v. Whitman, United States District

Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, Civil Action

No. 6760 .......................................................................................15,23

Braunfeld v. Gibbons, U. S. D. Ct. for the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania, Civil Action No. 26,945 ................................. 23

Broadbent v. Gibson, 105 Utah 53, 140 P. 2d 939 (1943) . . . . 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 394 U. S. 483 ( 1 9 5 4 ) ............... 17

Chicago V. Atchison T. & S. F. R. Co., 357 U. S. 77 (1958) . . 22

City of Mt. Vernon v. Julian, 369 111. 447, 17 N. E. 2d 52

(1938) .......................................................................................... 19

Commonwealth ex rel. v. American Baseball Club of Philadel

phia, 290 Pa. 136 (1927) ......................................................... 4

Commonwealth v. Bander, 188 Pa. Super. Ct. 424, 145 A. 2d

915 (1958), allocatur refused, 188 Pa. Super. Ct. xxviii . .

County of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda Co., 360 U. S. 185

(1959) ..........................................................................................

Crown Kosher Super Market of Massachusetts v. Gallagher,

176 F. Supp. 466 (D. Mass., 1959) ................................ 15,17,20

Cumberland Coal Co. v. Board of Revision, 284 U. S. 23 (1931) 22

Deese v. City of Lodi, 21 Cal. App. 2d 631, 69 P. 2d 1005

(1937) .......................................................................................... 19

Doud V. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 (1956) ........................................... 22

E x parte Hodges, 65 Okla. Crim. 69, 83 P. 2d 201 (1938) . . . . 19

Friedman v. New York, 341 U. S. 907 (1951) ................... 12,16,17

Gaetano Bocci & Sons Co. v. Town of Lawndale, 208 CaHf.

720, 284 Pac. 654 (1930) ........................................................ 19

Gronlund v. Salt Lake City, 194 P. 2d 464 (Utah, 1 9 4 8 ) ......... 19

13

22

TABLE OF CASES CITED (Continued).

Page

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167 (1959) ................................ 22

Henderson v. Antonacci, 62 So. 2d 5 (Fla., 1952) ................... 19

Hennington v. Georgia, 163 U. S. 299 ......................................... 18

Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U. S. 203

(1948) .......................................................................................... 14

International Brotherhood of Teamsters, A. F. L. v. Vogt, Inc.,

354 U. S. 284 (1957) ................................................................ 23

Lee V. Roseberry, 200 F. 2d 155 (C. A. 6th, 1952) ................... 2

Mackey Telegraph & Cable Co. v. Little Rock, 250 U. S. 94

(1919) .......................................................................................... 21

McGowan v. Maryland, 151 A. 2d 156 (Md., 1959), appeal

docketed in this Court at October Term, 1959, No. 438 . . 23

Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457 (1957) ...........................................18,20

Murdock V. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943) ........................ 18

People’s Appliance & Furniture, Inc. v. City of Flint, 99 N. W.

2d 522 (1959) ............................................................................. 20

Plessey v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ............................................. 18

Public Utilities Commission v. United States, 355 U. S. 534

(1958) .......................................................................................... 22

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 277

U. S. 389 (1928) ...................................................................... 18

Query v. United States, 316 U. S. 486 (1942) ....................... ;.. 2, 23

Radio Corp. of America v. United States, 341 U. S. 412 (1951) 2, 23

Sarner v. Township of Union, Superior Ct. of N. J., Law Revi

sion, Docket No. L-13061-57 P. W. (May 7, 1 9 5 9 ) ........... 23

Smith V. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 (1931) ........................................... 18

Sparhawk v. The Union Passenger Railway Co., 54 Pa. 401

(1867) .......................................................................................... 4

Sunday Lake Iron Co. v. Wakefield, 247 U. S. 350 (1918) . . . . 22

Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. Paul A. McGinley,

266 F. 2d 427 (C. A. 3rd, 1959) ............................................ 8

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S.

624 (1943) ................................................................................... 16

Yick Wo V. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) .............................. 22

STATUTES AND AUTHORITIES CITED.

Page

Act of April 22, 1794, 3 Sm. L. 177, § 1, 18 Purd. Stat. § 4699.4

3, et seq.

Amendatory Act of August 10, 1959, P. L. No. 212, 18 Purd.

Stat. §4699.10 ......................................... ............................ 3, et seq.

IV Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (9th Ed.

1783), Chapter 4, pp. 63-64 ..................................................... 14

Fisher, History of the Institution of the Sabbath Day, pp. 63-66 14

Mark, The Faith of Our Fathers, p. 286 .................................... 14

18 Purd. Stat. § 4302 ......................................................................... 8

III Stokes, Church and State in the United States, pp. 154-56,

157-58, 168-69 ............................................................................. 14

28 U. S. C. § 1253 ................................................................................ 2

28 U. S. C. § 1 2 9 1 ................................................................................ 2

28 U. S. C. § 1 3 3 1 ................................................................................ 8

28 U. S. C. § 1343 ................................................................................ 8

28 U. S. C. §2281 ................................................................................2 ,7 ,8

28 U. S. C. § 2284 ................................................................................ 8

42 U. S. C. § 1 9 8 1 ................................................................................ 8

42 U. S. C. § 1983 ................................................................................ 8

U. S. Constitution:

First Amendment ...................................................................... 14, 18

Fourteenth Amendment ............................................................14, 18

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States.

October Term, 1959.

No.

TWO GUYS FROM HARRISON-ALLENTOWN, INC.,

Appellant,

PAUL A. McGINLEY, DISTRICT ATTORNEY,

COUNTY OF LEHIGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DE

PENDANT AND GEORGE J. JOSEPH, DISTRICT

ATTORNEY, COUNTY OF LEHIGH, PENNSYL

VANIA, SUBSTITUTED ADDITIONAL DEPEND

ANT,

Appellees.

On A ppeal P rom the P inal Order of a T hree-Judge

Court S itting in the E astern D istrict op P ennsylvania

P ursuant to 28 U. S. C. § 2281 et seq.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT.

A.

Opinions Delivered in the Court Below.

The majority opinion of the three-judge court, filed on

December 1, 1959 but not yet reported, is annexed hereto

as Appendix A, infra. Appendix A also contains Senior

District Judge Welsh’s dissenting opinion beginning on

2 Jurisdictional Statement

p. 16a, et seq., infra. On December 7, 1959 the three-judge

court denied a timely petition for rehearing, but simul

taneously filed supplemental findings of fact which are an

nexed hereto as Appendix B, infra, p. 20a, et seq.

An appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Third Cir

cuit, solely with respect to the claim of discriminatory en

forcement was filed and was dismissed for lack of juris

diction on December 9, 1959. An opinion thereon was filed

on December 23, 1959, a copy of which is annexed hereto as

Appendix C, infra, p. 23a. Appellant is simultaneously

hereudth filing a petition for a writ of certiorari to review

said dismissal.

An appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Third Cir

cuit on an earlier phase of this case is reported at 266 F. 2d

427 (C. A. 3rd, 1959).

B.

Statement of the Grounds on Which Jurisdiction

Is Invoked.

The final order from which appeal is taken is from the

decision of the three-judge court entered on December 7,

1959, on which day rehearing was also denied. See Ap

pendix D. The notice of appeal was filed December 18,

1959 in the District Court.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28

U. S. C. §§ 1253, 1291 and 2281 et seq., the appeal being

from a final order of a three-judge court which refused a

permanent injunction and dissolved the temporary injunc

tion on the ground that the state statutes attacked by appel

lant did not conflict with the Federal Constitution. Query

V. United States, 316 U. S. 486, 490-91 (1942); Two Guys

from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, No. 13,096

(C. A. 3rd, December 23, 1959) (Appendix C ); see also

Lee V. Roseberry, 200 F. 2d 155, 156 (C. A. 6th, 1952); cf.

Radio Corp. of America v. United States, 341 U. S. 412

(1951).

Jurisdictional Statement

0.

Statutes Involved.

The Pennsylvania statutes whose validity are involved

are the basic Pennsylvania Sunday law which provides;

“ Whoever does or performs any worldly employ

ment or business whatsoever on the Lord’s Day, com

monly called Sunday (works of necessity and charity

only excepted), or uses or practices any game, hunting,

shooting, sport or diversion whatsoever on the same day

not authorized by law, shall, upon conviction thereof

in a summary proceeding, be sentenced to pay a fine

of four dollars ($4), for the use of the Commonwealth,

or, in default of the payment thereof, shall suffer six

(6) days’ imprisonment.

“ Nothing herein contained shall be construed to

prohibit the dressing of victuals in private families,

bake-houses, lodging-houses, inns and other houses of

entertainment for the use of sojourners, travellers or

strangers, or to hinder waterman from landing their

passengers, or ferrymen from carrying over the water

travellers, or persons removing with their families on

the Lord’s Day, commonly called Sunday, nor to the

delivery of milk or the necessaries of life, before nine

of the clock in the forenoon, nor after five of the clock

in the afternoon of the same day.’’ Act of April 22,

1794, 3 8m. L. 177, § 1, 18 Purd. Stat. § 4699.4 (bold

face type supplied),

and the Amendatory Act of August 10, 1959 which pro

vides:

“Whoever engages on Sunday in the business of

selling, or sells or offers for sale, on such day at retail,

clothing and wearing apparel, clothing accessories,

furniture, housewares, home, business or office fur

nishings, household, business or office appliances, hard-

4 Jurisdictional Statement

ware, tools, paints, building and lumber supply ma

terials, jewelry, silverware, watches, clocks, luggage,

musical instruments and recordings, or toys, excluding

novelties and souvenirs, shall, upon conviction thereof

in a summary proceeding for the first offense, be sen

tenced to pay a fine of not exceeding one hundred dol

lars ($100), and for the second or any subsequent

offense committed within one year after conviction for

the first offense, be sentenced to pay a fine of not

exceeding two hundred dollars ($200) or undergo im

prisonment not exceeding thirty days in default

thereof.

“ Each separate sale or offer to sell shall constitute

a separate offense . . . ” P. L. No. 212, 18 Purd. Stat.

§ 4699.10. (bold face type supplied)

The Federal Constitutional provisions involved are the

F irst and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States including the equal protection and due

process clauses of the latter Amendment.

D.

Questions Presented.

The basic Pennsylvania Sunday Blue Law, the Act of

April 22,1794,18 Purd. Stat. § 4699.4, prohibits all “worldly

employment” except acts of necessity on the “ Lord’s Day

(commonly called Sunday)” so that the citizens of Penn

sylvania can “ read the Scriptures” and attend “ religious

worship.” Sparhawk v. The Union Passenger Railway Co.,

54 Pa. 401, 408-09, 423 (1867); Commonwealth ex rel. v.

American Baseball Club of Philadelphia, 290 Pa. 136, 143

(1927). This Act was amended on August 10,1959 so as to

impose additional and heavier penalties on those who sold

or offered to sell at retail certain enumerated merchandise

on the Lord’s Day. The court below made the following

findings of fact:

Jurisdictional Statement

(1) the Amendatory Act of August 10, 1959 was to

force the cessation of work on Sunday in order to com

memorate weekly the sectarian religious event and doctrine

of the Eesurrection of Jesus Christ, the same event and

doctrine as are commemorated by the Christian Easter

(4a, 20a);

(2) that such practice was offensive to those persons

whose religious teachings were contrary to those which gave

such religious significance to Sunday, including Seventh

Day Adventists, Seventh Day Baptists, Jews and atheists

(4a);

(3) that work on Sunday had no different effect on the

health or welfare of appellant’s employees or customers

from work on any other day (20a);

(4) Pennsylvania has a separate and distinct pattern

of economic laws regulating hours of work which operate

completely independently of the Sunday Laws (22a);

(5) by legislative acts and court decisions many sub

stantially similar activities are exempt from the Sunday

Blue Law (20a), and

(6) many activities substantially similar to those en

gaged in by the appellant have been and will be permitted

by law enforcement officers in Pennsylvania even though

nominally prohibited by statutes and^^ourt decisions (14a).

The record also shows that for pe'rsonal profit reasons

appellee. District Attorney Paul A. McGinley, wilfully and

discriminatorily enforced the law only against appellant and

not against other similar businesses even though such dis

crimination was called to his attention and protested. The

court below refrained from making requested findings on

the issue of discrimination in administration on the ground

that McGinley’s term of office would shortly expire, but

many prosecutions instituted by him still are pending.

Jurisdictional Statement

The questions therefore presented a re :

1. Does the Pennsylvania Act of August 10,1959, in the

light of the court findings referred to above, violate the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution be

cause :

(a) it is a law respecting the establishment of

religion;

(b) it discriminates against certain religions and

prefers one religion over other religious beliefs;

(c) there is no reasonable basis for the classifica

tion of prohibited and permitted activities contained in

the Pennsylvania Act of August 10, 1959 and other

Pennsylvania statutes and court decisions dealing with

worldly activities in Pennsylvania on the Lord’s Day;

(d) it imposes oppressive and discriminatory

fines?

2. Did the wilful, arbitrary and discriminatory enforce

ment of the Pennsylvania Sunday Blue Law against appel

lant by appellee. District Attorney Paul A. McGinley,

deprive appellant of rights guaranteed it by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution?

3. Did the court below err in refusing to pass upon the

constitutionality of the Act of April 22,1794,18 Purd. Stat.

§ 4699.4, and dismissing that part of the complaint on the

ground that a subsequent Pennsylvania court decision might

make said statute inapplicable to appellant’s employees,

despite the fact that (a) there was a state court decision

that said Act did apply to appellant’s employees and (b)

appellant sold many items not covered by the Act of

August 10, 1959 but covered by the Act of April 22, 1794?

Jurisdictional Statement

E.

Statement of the Case.

This appeal is from the final order of a three-judge

court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania which denied

a permanent injunction and dissolved the Temporary In

junction, after upholding by a two to one vote the con

stitutionality of the Pennsylvania Sunday Blue Laws, in

cluding the Amendatory Act of August 10, 1959, P. L. 212,

18 Purd. Stat. § 4699.10.

Said court was convened pursuant to Sections 2281, et

seq. of Title 28 V. S. C.

The court below expressly held that its decision was

“ contrary to the view of the majority of the three-judge

district court which recently decided Crown Kosher Super

Market v. Gallagher, 176 F. Supp. 466 (D. Mass. 1959),”

p. 10a, infra, which case is now on direct appeal to this

Court at Docket No. 532, October Term, 1959.

Appellant herein. Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown,

Inc., operates a retail store in Whitehall Township, Lehigh

County, Pennsylvania, employing 300 persons. The store

is along the highway outside the City of Allentown, with a

parking lot for several thousand cars and caters to the

family shopping group out for a Sunday drive and in

terested in economy as against “ fancy and expensive down

town store” services.

Appellant opened its store in Lehigh County at a cost

of over $1,000,000 only after it had been told that no one

ever had been prosecuted for selling on Sunday and being

assured by the township officials that its operation was

permissible (N. T. 91, 96-97).^ After appellant was open

for six months the appellee, Paul A. McGinley, then the

District Attorney of Lehigh County, began to arrest ap

pellant’s employees for violations of the Act of April 22,

1794,18 Purd. Stat. § 4699.4, the basic Pennsylvania Sunday

Blue Law. These arrests and prosecutions continued every

1. The “N. T.” references are to notes of testimony taken in the

court below.

8 Jurisdictional Statement

Sunday although other business activities were permitted

by appellee McGinley without arrest.^ A year later, in

November, 1958, said appellee threatened to arrest appel

lan t’s employees for conspiracy, the penalty for which is

a two year jail sentence and a $500 fine. 18 Purd. Stat.

§ 4302.

The appellant thereupon bro-ught a bill in equity in

the Federal Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §§ 1331 and 1343, 42 U. S. C. 1981

and 1983 and to 28 U. S. C. §§ 2281 and 2284. The biU in

equity alleged that the Pennsylvania Sunday Law—the Act

of April 22, 1794—was unconstitutional because: (a) it was

a law respecting the establishment of religion; or (b) a law

which prefers or places at an advantage one religion over

others; (c) it denies equal protection sincn it was discrim

inatory; and (d) the appellee, Paul A. McGinley. was apply

ing the law to appellant in a wiLfuUy discriminatory manner,

thi complaint and affidavits the Court issued a temporary

restraining order.

Since appellant was making an attack on the consti

tutionality of a state statute the matter was heand before

a specially constituted three-ittdge court. See Guys

from Harnson-AUrntou'K. Inc

F. 2d 427 tO. A. 3rd. 1959t.

luutuvuatcly prior to the

the Cou.ip’air.t. the

F^'y.1 A. ilc ir ifiiz 'J . 2fi6

ilHug of

passed an ameimatory act

which si’tgled out tor mo

' 1 ev.r.sy.varaa ijcgtslsture

;e Ae: of August lA —

■s. ' t, , t. ~

sales of par'ieu lar utereh.ar.dise seie. hy t ie aroehlant. The

bill in eqr.ity w.as ;uuor.d< \̂i to ittoitme at. s ttsck csu the oon-

siinuionalily of th.is .\ct on the SAme grounds^

The court after hoarittg grante\i a prelintinary injiunc-

tion against enforcomoi\i of tlie Sunday Blue Laws against

appellant after finding that "sttbstanti.al and irreparable in-

2. 'fho Ktvord shows that ap>p>e]lee, Paul A. McGinlej-, dis-

criininatol against plaiutitTs employees because he was improperly

induced to do so hy Max Hess, the President and owner of Hess’

Departtnent Store, ap;x'llant's principal business competitor (N . T.

178-79, 2.h):i-41, 19.S, 254-.S.S).

Jurisdictional Statement

jury will be suffered by plaiutilT [if the statutes are applied

to it] because plaintiff will be required to discontinue the

operation of its store on Sunday, the day of its largest

sales volume.” (Order dated September 11, 1959.)

The case was tried on the merits in October, 1959. The

court found that appellee, Paul A. McGinley, had threatened

to enforce the Act of August 10, 1959, P. L. 212, 18 Purd.

Stat. § 4699.10, against appellant’s employees, that he had

in the past enforced the Act of April 22,1794,18 Purd. Stat.

§ 4699.4, against appellant’s employees, that appellant had

no adequate remedy at law and that appellant would ‘ ‘ suffer

irreparable harm.” See Appendix A, infra, p. 2a and

Appendix B, infra, p. 22a.

Certain findings also are relevant to the merits of the

question of the constitutionality of the Act of August 10,

1959.

The court below found that the origin, purpose and

effect of the Pennsylvania Sunday Laws, including the Act

of August 10, 1959, were to force observation of the

Christian Lord’s Day and that there were many persons in

Pennsylvania who were offended in their religious beliefs

by the required cessation of business on Sunday since it

is “ an enforced expression of respect for and acknowledg

ment of the sacred character and religious symbolism of the

Christian Sabbath, a religious institution commemorating

the resurrection of Christ.” Appendix A, infra, p. 4a.

The Court also made the following additional findings

of fac t:

“ 1. Sunday is a day designated for religious serv

ices and observances of Christians, with the exception

of certain Seventh Day Adventists and Baptists. The

Christian Sabbath commemorates and honors the Ees-

urrection of Christ. I t is marked by a weekly cele

bration of the same religious event basic to Christianity

as is celebrated by Easter.

“ 2. Sunday work at plaintiff’s store has no differ

ent effect upon the health or welfare of either the em-

10 Jurisdictional Statement

ployees or customers of the store than does work on

any other day.

“ 3. Various Pennsylvania statutes create excep

tions to the general statutory prohibition of worldly

activity on Sunday, or increase the penalties for con

ducting activities prohibited thereby. These statutes

now make it lawful, despite the general prohibition, to

operate a motion picture house after 2:00 P. M. on

Sunday if the voters of the municipality so vote by

referendum. Act of July 2, 1935, P. L. 599, 4 Purd.

Stat. §§ 59-65; to play professional baseball and foot

ball after 2 :00 P. M. and before 6 :00 P. M. on Sunday

if the voters of the municipality so vote by referendum.

Act of April 25, 1933, P. L. 74, 4 Purd. Stat. §§ 81-77;

to stage musical concerts after 12:00 noon on Sunday

when authorized to do so by the Commonwealth’s De

partment of Public Instruction and to compensate

musicians participating in such concerts. Act of June 2,

1933, P. L. 1423, No. 308, 4 Purd. Stat. §§ 121-127; to

play polo after 1 :00 P. M. and before 7 :00 P. M. on

Sunday unless the voters of the municipality have voted

to the contrary by referendum. Act of June 22, 1935,

P. L. 446, 4 Purd. Stat. §§ 151-157; to play tennis after

1 :00 P. M. and before 7 :00 P. M. on Sunday, Act of

June 22, 1935, P. L. 449, 4 Purd. Stat. §§ 181-185, pro

vided that the conduct of other sports on Sunday after

noon has been approved by municipal referendum; to

fish on Sunday, Act of April 14, 1937, P. L. 312, 1, as

amended, 30 Ptrrd. Stat. § 265; to remove raccoons and

fur-bearing animals caught in hunting traps or dead

falls on Sunday, Act of June 3, 1937, P. L. 1225, Art.

VII, § 702, as amended, 34 Purd. Stat. § 1311.702; and

for a private chib, but not a restaurant or hotel, to sell

liquor to its members on Sunday, xVct of April 12,1951,

P. L. IX\ A ll. IV, 406, as amended, 47 Purd. Stat.

4-4lX> (pp. 71-72).

Jurisdictional Statement 11

“ 4. The fine for the generality of offenses, includ

ing the conduct of some games and amusements is $4.00,

plus costs that run from two to four times the fine. But

for howling, baseball and football during prohibited

hours, it is $10.00, 18 Purd. Stat. § 4651, 4 Purd. 8 tat.

§ 82; for polo $100, for motion pictures $50.00, for

musical concerts $100 to $1,000, 4 Purd. Stat. §§ 152,

65, 127. For persons selling motor vehicles at retail

or wholesale, the fine is $100 for engaging in business

the first Sunday and $200 thereafter, 4 Purd Stat.

% 4699.9. For selling motor boats, it is $4.00. For

selling an automobile air-conditioner, it is $4.00. For

selling a home air-conditioner it is $100 for each sale

at retail, hut only $4.00 at wholesale. Sale of slip

covers for automobile seats all day Sunday entails a

$4.00 fine; the sale of a slip cover for a living room

chair at retail entails a $100 fine for the first sale and

$200 for each and every sale thereafter, and for each

unsuccessful offer to sell. To sell or offer to sell toys

after the first offer is subject to a $200 fine, whereas

novelties and souvenirs can be sold for the entire day

for the payment of one $4.00 fine. Certain sports equip

ment is in the $4.00 category, including shoes used in

forbidden sports. On the other hand, the sale of a

pair of shoes for business wear is in the $100 category.

“5. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, has en

acted a pattern of economic laws under the police power

regulating hours of work, which operate completely

independently of the Sunday laws. They include such

statutes as Act of July 25, 1913, P. L. 1024, § 3, as

amended, 43 Purd. Stat. § 103(a) (women cannot work

more than six days in any one week); Act of May 13,

1915, P. L. 286, § 4, as amended, 43 Purd. Stat. § 46

(persons under the age of 18 cannot work more than

six consecutive days in any one week); Act of May 27,

1897, P. L. 112, § 1,43 Purd. Stat. § 361 (bakery workers

12 Jurisdictional Statement

cannot work more than six days in any one week); Act

of March 31, 1937, P. L. 159, § 1, 43 Purd. Stat. % 481

(employees of motion picture theaters must be given

one day of rest per week).” Appendix B, infra, pp.

20a-22a.

The majority of the court, however, refused to declare

the two Pennsylvania statutes under attack unconstitu

tional. With respect to the Act of August 10, 1959, it held

that despite the clear proof of the religious origin, purpose

and effect thereof, this Court’s action in Friedman v. New

York, 341 U. S. 907 (1951), wherein this Court dismissed

an appeal with respect to a New York Sunday statute for

“ want of a substantial federal question,” precluded an in

dependent consideration of the constitutionality of such

statute, since that decision had to be construed as a holding

that any Sunday Blue Law even though religious in origin,

purpose and effect, nevertheless does not violate the

Fourteenth Amendment. With respect to the argument on

the equal protection clause due to the unreasonable and

discriminatory classification contained in the 1959 Act,

the court, ignoring religious overtones of the statute,

held that where the statute deals with economic matters

this Court permits “ even near whimsical classifications

when made by state logislat^lres in the selection of schemes

or areas or subject matter for economic regulations.” Ap

pendix .V, infra, p. 12a.

’Phe court below refrained fi*om passing upon the claim

(hat the appellee Bistriet .Vltonioy. Paiil A. McGinley. had

wilfully atul discriminatorily enfonnxl Sunday Laws

against the appellant. It coiuHHle<l and found as a fact that

there ha»l been no enfon*ement prior to actions against the

appellant. But it held that it Ŷvn̂ ld run make “ an anticipa

tory tindiiig” with res^Hn't to the fuutro because the term of

I'aul .V. MoOinley as Bistrict -Vttornev wvntld expire, ac-

vanxliiig to the t\n irt. on IXwmK'r c l. But it did

admit that ou the prx'sent txxvrvi even after appellee's term

Jurisdictional Statement 13

would end “ we have the threat of the enforcement of the

1959 act against retail selling while many other kinds of

worldly activity proscribed by the 1939 laws have continued

and are likely to continue without any interference by the

public authorities.” Appendix A, infra, p. 14a.

I t disposed of the constitutional problem thus pre

sented, however, by the novel theory that any discrimination

that could be carried out by the Legislature through a

statute would be equally valid if carried out by the indi

vidual law enforcement officer by applying the statute

against only certain businesses regardless of the motive for

the discrimination on the part of the official. Appendix A,

infra, p. 14a.

On the theory that a Pennsylvania court might hold

that activities covered by the Act of August 10, 1959 were

now exempt from the broader provisions of the Act of 1794,

it refused to pass upon the constitutionality of the Act of

1794. I t did this despite the fact that less than a year be

fore the highest Pennsylvania court had held that appel

lan t’s employees were covered by the Act of 1794, Common

wealth V. Bander, 188 Pa. Super. Ct. 424, 145 A. 2d 915

(1958), allocatur refused, 188 Pa. Super. Ct. xxviii, and ap

pellee himself was still contending that he could arrest

under the Act of 1794 (Appendix A, infra, p. 3a), and

appellant sold many items covered only by the Act of 1794.

As stated above, the court entered a final order deny

ing the prayer for final relief and dissolving the temporary

restraining order previously in effect. On rehearing, the

court, inter alia, refused to retain jurisdiction of the part

of the case dealing with the Act of 1794 pending a state

court determination.

Appellant attempted to appeal to the Court of Appeals

solely from the part of the court’s order that dealt with the

question of discriminatory enforcement by appellee, Paul

A. McGinley, but the Court of Appeals held that an appeal

from any action of a three-judge court would have to be

to this Court, even with respeci to the part of the case which

could have been heard originally by a single judge.

14 Jurisdictional Statement

This Court on December 11, 1959, refused to reinstate

the restraining order pending the Appeal.

After the expiration of the term of office of Paul A.

McGinley, an order was entered permitting appellant to

substitute George J. Joseph, the new District Attorney, as

an additional defendant.

F.

The Federal Questions Are Substantial, Were Wrongly

Decided Below, and Are of Great Public Importance.

I.

This is the first case where a court has made an explicit

finding of fact that a particular state law complained of is

religious in origin, purpose and effect and yet sustained the

statute against a claim of unconstitutionality.® Such a

result clearly conflicts with the decisions of this Court hold

ing the F irst Amendment to the Federal Constitution is

made applicable to states by the Fourteenth Amendment.

See Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333

U. S. 203, 210-11 (1948), which set up the test of prohibited

state action in the religious field as follows:

“ Neither a state nor the federal Government can

set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one

religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over

another. Neither can force or influence a person to go

to or to remain away from church against his will or

force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.

3. Recognized scholars from Blackstone to Chief Judge

Magruder have recognized the religious nature and effect of Sunday

Blue Laws. IV B lackstone, Com m enta ries on t h e L aws of

E ngland (9th Ed. 1783), Chapter 4, pp. 63-64; M ark , T h e F a it h

of O ur F ath ers , p. 286; F is h e r , H istory of t h e I n stitu tio n of

THE S abbath D ay, pp. 63-66; I I I S tokes, C h u r c h and S tate in

t h e U nited States, pp. 154-56, 157-58, 168-69; see also plaintiff’s

Brief in the court below, copies of which were filed with this Court on

December 9, 1959 in support of its petition for an interim restraining

order.

Jurisdictional Statement 15

No person can be punished for entertaining or pro

fessing religions beliefs or disbeliefs, for church at

tendance or nonattendance . . . In the words of

Jefferson, the clause against establishment of religion

by law was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation be

tween church and state.’ ”

The decision in the case at bar also conflicts with the

decision of the three-judge court of the District of Massa

chusetts which held unconstitutional the Massachusetts

Sunday Law. Crown Kosher Super Market of Massachu

setts V. Gallagher, 176 F. Supp. 466 (D. Mass., 1959), now

on appeal to this Court at Docket No. 532, October Term,

1959. In that case the court said;

“ What Massachusetts has done in this statute is to

furnish special protection to the dominant Christian

sects which celebrate Sunday as the Lord’s day, with

out furnishing such protection, in their religious ob

servances, to those Christian sects and to Orthodox

and Conservative Jews who observe Saturday as the

Sabbath, and to the prejudice of the latter group.

“ For reasons closely related to those just set

forth, the objection is well taken that, in furtherance

of no legitimate interest which Massachusetts is en

titled to safeguard, the statute arbitrarily requires

Crown Market to be closed on Sunday, thereby causing

the corporate plaintiff to lose potential sales and to be

denied the right to use its property on Sunday, with

the result of depriving the corporate plaintiff of liberty

and property and the other plaintiffs of liberty, without

due process of law, contrary to the Fourteenth Amend

ment.” p. 475.

Also, Judges Goodrich and Hastie in Bargaintown,

U.S.A., Inc. V. Whitman, United States District Court for

the Middle District of Pennsylvania, Civil Action No. 6760,

16 Jurisdictional Statement

a case dealing with the Pennsylvania Act of August 10,

1959, said:

“ If the question involved in this case came to us

as one of first impression we would find great difficulty

in upholding the constitutionality of the legislation in

question. ’ ’

Judge Hastie was also one of the majority below in this

case.

Such doubt as to constitutionality certainly is not

disposed of by a simple reference to this Court’s single line

order in Friedman v. New Yorlc, 341 U. S. 907 (1951).

The compulsory abstention from work on Sunday is a

compulsory form of religious observance, like kneeling,

eevering or uncovering the head and other ceremonies or

symbols. As this Court said in the flag salute ease, TTest

Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U. S.

624, 632-33, 642 (1943):

“ There is no doubt that, in connection with the

pledges, the flag salute is a form of utterance. Sym

bolism is a primitive but effiective way of communicat

ing ideas. The use of an emblem or flag to symbolize

some system, idea, institution, or personality, is a short

cut from mind to mind. Causes and nations, political

parties, lodges and ecclesiastical groups seek to knit

the loyalty of their followings to a flag or banner, a

color or design. The State announces rank, function,

and authority through crowns and maces, unite runs and

black roises: the church speaks through the Cress, the

Cracihx. the altar and shrine, and dkrieal raiment.

Symbols of State often convey politieal ideas just as

religious symbols come to convey theological ones. As

sociated with many of these symbols are appropriate

gestures of acceptance or respect: a salute, a bowed

or bared head, a bended knee. A person gets from a

symbol the meaning he puts into it, and what is one

Jurisdictional Statement 17

man’s comfort and inspiration is another’s jest and

scorn.

“ If there is any fixed star in our constitutional

constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can

prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, national

ism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force

citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.

I f there are any circumstances which permit an ex

ception, they do not now occur to us.

“ We think the action of the local authorities in

compelling the flag salute and pledge transcends con

stitutional limitations on their power and invades the

sphere of intellect and spirit which it is the purpose

of the F irst Amendment to our Constitution to reserve

from all official control.”

The findings of the court below with respect to a sepa

rate statutory scheme for hours of work and the effect of

Sunday work on the employees and customers, as well as

Chief Judge M agruder’s clear analysis of the day-of-rest

argument in the Crown Kosher case, supra make it crystal

clear that the question of Sunday Laws must he squarely

met and disposed of by this Court. In Friedman v. New

York, supra, there was no finding by the court below that

the statute involved was religious in nature, purpose or

effect. The same thing is true of the other Sunday Law

cases which this Court has refused to hear since 1950.

I t would seem, in accordance with the proeednre fol

lowed in Brown v. Board of Education, 394 IT. S. 4S3 (1954),

that this new finding of fact requires a reconsideration of

the Friedman rule, just as the new finding of fact by the

lower court in the Brown case required a reconsideration of

the separate-but-equal doctrine. More basic in fact is that

Friedman, supra is not here controlling. Crmcn Kosher v.

Gallagher, supra.

18 Jurisdictional Statement

The last full opinion by this Court on Sunday laws was

in 1896 {Bennington v. Georgia, 163 U. S. 299, 304), the

same year as Plessey v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, and was a

half century prior to the decision in Murdock v. Pennsyl

vania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943), which for the first time held

that the religious protections of the F irst Amendment apply

to state action, under the Fourteenth Amendment.

n.

As set out in findings of facts Nos. 3 and 4 of the court

below. Appendix B, infra, pp. 20a-21a, the business and com

mercial activities permitted on Sunday and the varying

fines for those prohibited afford no rational basis for dis

tinction between those prohibited and those subject to

stringent penalty. And the penalties are in some cases

200 times the amount collected on the sale.

In what manner does a sale at retail differ from a sale

at wholesale justifying different Sunday treatment? If

these are day-of-rest statutes, do not employees of whole

sale establishments, factories and service establishments

need a day of rest too? What is the distinction between

commodities not listed in the Act of August 10, 1959 as

against those contained therein?

Certainly such willy-nilly statutory distinctions do not

comply with the constitutional requirement that “ a statu

tory discrimination must be based on differences that are

reasonably related to the purpose of the Act in which it is

found.” Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457, 465 (1957); Smith

V. Gaboon, 283 U. S. 553, 567 (1931); see also Quaker City

Cab Co. V. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389,

406 (1928), wherein this Court said:

“ . . . classification must rest upon a difference

which is real, as distinguished from one which is

seeming, specious, or fanciful, so that all actually situ-

Jurisdictional Statement 19

ated similarly will be treated alike; that the object of

the classification must be the accomplishment of a

purpose or the promotion of a policy, which is within

the permissible functions of the state; and that the

difference must bear a relation to the object of the

legislation which is substantial, as distinguished from

one which is speculative, remote or negligible.”

If it be argued that the reason for the classifications

and exemptions in the present Pennsylvania Sunday sta

tutes is to keep pace with changing mores of proper deport

ment on Sunday, to permit those recreational activities

which modern religion tolerates and to ban or condemn

commercial and business activities which it disapproves of,

—the sohcalled “ continental Sunday”—such legislation

would be seeking to achieve an unconstitutional purpose,

namely to establish religion, albeit a more relaxed t5rpe of

religion than the Puritan principles which the original Sun

day laws were enacted to serve. I t would be unconstitu

tional because of this end purpose. No other tenable or

rational basis for the classification and discriminatory ex

emptions can be advanced.

Many State cases faced with statutory classification

schemes less discriminatory than the Pennsylvania situa

tion have held their Sunday laws unconstitutional as denial

of equal protection of laws. See e.g., City of Mt. Vernon

V. Julian, 369 111. 447, 17 N. E. 2d 52 (1938) ; Arrigo v. City

of Lincoln, 154 Neb. 537, 48 N. W. 2d 643 (1951); Gronlund

V. Salt Lake City, 194 P. 2d 464 (Utah, 1948); Allen v.

Colorado Springs, 101 Colo. 498, 75 P. 2d 141 (1938);

Gaetano Bocci S Sons Go. v. Town of Lawndale, 208 Calif.

720, 284 Pac. 654 (1930); Deese v. City of Lodi, 21 Cal. App.

2d 631, 69 P. 2d 1005 (1937); Broadbent v. Gibson, 105

Utah 53, 140 P. 2d 939 (1943); E x parte Hodges, 65 Okla.

Crim. 69, 83 P. 2d 201 (1938); Henderson v. Antonacci, 62

So. 2d 5 (Fla. 1952).

20 Jurisdictional Statement

Once again the F irst Circnit’s decision in Crown

Kosher Super Market of Massachusetts v. Gallagher, 176

F. Supp. 466 (D. Mass., 1959), is directly opposite that of

the decision in the case at bar. Moreover, even if the law

were economic rather than religious, this Court has never

held that merely because a law is economic in purpose a

Legislature can engage in “ whimsical classifications.” In

fact, this Court has repeatedly held that even with respect

to economic legislation the classification must be reasonable

and be based upon a difference between those activities in

cluded and those excluded. Morey v. Doud, 354 U. S. 457

(1957).

Appellant is engaged in a new type of merchandising

which the public is very much in favor of. Obviously the

existing downtown stores are using every method to throttle

this unwelcome competition. As Senior Judge Welsh ob

served in his dissent, the downtown department stores seek

to stifle the competition by reviving the religious laws

which had fallen into disuse (18a-19a). Since this law

affects the economic life of a large segment of a particular

industry certainly this matter should be resolved by this

Court.

III.

The decision of the court below affects adversely all

those who do not believe in the resurrection of Christ on

Sunday, including Jews, who are 3.04% of the population

and Seventh Day Adventists and Baptists who are 1% of

the population. I t also affects adversely the 4% of the

population that has no religious traditional affiliation or

belief. The decision unfortunately represents the type of

judicial approach to Sunday Law questions so ably de

scribed by Judge Voelker in People’s Appliance <& Furni

ture, Inc. V. City of Flint, Supreme Court of Michigan, Nov.

24, 1959, 99 N. W. 2d 522, 530 (1959):

“ . . . there exists a curious and rather wide

spread judicial reticence when our courts are dealing

Jurisdictional Statement 21

with so-called Sunday ordinances. The judicial ap

proach then often seems to become gingerly to the point

of timidity, as though the fact that, however invalid

such ordinances may be when judged by ordinary

standards, after all most Sunday ordinances are

plainly on the side of morality and all right-thinking

people and, if they should err, they do so on the side of

the angels. If such a tendency exists (and we trust we

are wrong), we can only observe that an unreasonably

discriminatory or otherwise invalid ordinance is no

less bad because it happens also to please the pious.

I t is bad enough that Sunday ordinances should ever

unreasonably discriminate between our people; it is

doubly bad should there ever be any hint of judicial

discrimination in their interpretation as against the

accepted rules of interpretation applying to ordinary

ordinances. Yet this apparent double standard is par

ticularly evident in Michigan, as I shall presently un

dertake to demonstrate. One had not heretofore been

sufficiently aware of the fact that in Michigan there

are evidently Sunday standards for judging Sunday

ordinances. I am now aware and I do not like what

I see.”

IV.

The court’s decision, unless reversed, will establish the

rule of law that wilful and purposeful discrimination in the

enforcement of a statute by a state officer only violates the

Fourteenth Amendment if the victim can show that the

classification which results from the officials’ wrongful ac

tions is one which the state Legislature could not have

brought about. This obviously is not the law. I t would be

a complete abandonment of the fundamental concept that

ours is a government of law, not of men. Such a rule, more

over, is in conflict with the decisions of this Court: Mackay

Telegraph <& Cable Co. v. Little Rock, 250 U. S. 94, 100

22 Jurisdictional Statement

(1919); Cumberland Coal Co. v. Board of Revision, 284

U. S. 23 (1931). There is a difference—a constitutional

difference—between a classification made by a Legisla

ture and one made by a law enforcement officer, par

ticularly where he makes the discrimination for improper

motives. Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374 (1886);

Sunday Lake Iron Co. v. Wakefield, 247 U. S. 350, 352

(1918).

The refusal to pass upon the Act of 1794 raises a

serious question of appropriate Federal procedure. Here

the state court had less than a year before held that the

Act of 1794 applied to appellant’s employees and the ap

pellee conceded that said Act still applied. Appendix A,

infra, p. 3a. Moreover, appellant sells many items not

covered by the Act of 1959 but covered by the broad lan

guage (“ all worldly employment” ) of the Act of 1794. See

Chicago v. Atchison T. S S. F. R. Co., 357 U. S. 77 (1958);

Public Utilities Commission v. United States, 355 U. S. 534

(1958); County of Allegheny v. Frank Mashuda Co., 360

U. S. 185 (1959), particularly with respect to whether juris

diction should have been maintained pending a state court

determination and what protective relief by way of an in

junction or a stipulation by a responsible state officer of no

enforcement pending decision appellant was entitled to in

the interim. Cf. Doud v. Hodge, 350 U. S. 485 (1956); Har

rison V. NAACP, 360 V. S. 167, 178-79 (1959).

VI.

The questions presented by the instant case and by the

decision of the court below are substantial and important.

Since the decision was by a specially constituted three-judge

court it would seem that appellant has a statutory right to

Jurisdictional Statement 23

present its views and argument before this Court. Query

V. United States, 316 U. S. 486, 490-91 (1942); cf. Radio

Corp. of America v. United States, 341 U. S. 412 (1951).

Moreover, the decision is not an isolated decision of an

inferior court which, though in error, does not present that

recurring type of situation which this Court will review.

Since 1950 there have been repeated petitions to this Court

seeking a final determination on the constitutionality of

the Sunday laws of various states. Cf. International Broth

erhood of Teamsters, A. F. L. v. Vogt, Inc., 354 U. S. 284

(1957). In addition, this is a recurring problem presently

before the Supreme Courts of many states as well as lower

federal courts. See e.g. Bargaintown, U. S. A., Inc. v. Whit-

;man, TJ. S. D. Ct. for the Middle District of Pennsylvania,

Civil Action No. 6760; Braunfeld v. Gibbons, U. S. D. Ct. for

the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, Civil Action No.

26,945; McGowan v. Maryland, 151 A. 2d 156 (Md., 1959),

appeal docketed in this Court at October Term, 1959, No.

438; Sarner v. Township of Union, Superior Ct. of N. J.,

Law Revision, Docket No. L-13061-57 P. W. (May 7, 1959).

Since the problem is fundamental, touching on a contro

versial religious question, the legal controversy will be re

solved only by a determinative decision of this Court after

full argument aided by comprehensive briefs on the merits.

CONCLUSION.

The Pennsylvania Sunday Laws here in question were

found by the court below to be religious in purpose and

effect. I t is apparent that the court refrained from invali

dating them only because of the order of this Court in the

Friedman case, which, if it be a decision on the merits, was

predicated upon an entirely different fact finding. The

arbitrary classifications and exemptions in these laws could

be sustained in no context other than a religious one. Ap

pendix A, 19a.

24 Jurisdictional Statement

The questions herein presented are substantial and of

great public and inunediate importance. Appellants re

quest that jurisdiction be noted and this case be set for

argument a t the same time as No. 532, October Term, 1959.

Respectfully submitted,

H aeold E. K ohn ,

W illiam T. Coleman, J e.,

L ouis E. L evinthal,

2635 Pidelity-Philadelphia

Trust Building,

Philadelphia 9, Pa.,

Moeeis E eeon,

502 Turner Street,

Allentown, Pa.,

Attorneys for Appellant.

D ilwoeth, P axson, K alish,

K o h n & B il k s ,

H aeey a . K alish,

OscAE B eown,

Of Counsel.

Dated: February 11, 1960.

APPENDIX A.

I n the U nited S tates D istrict Court for the

E astern D istrict of P ennsylvania.

Civil A ction N o. 25626.

TWO GUYS FBOM HARRISON-ALLENTOWN, INC.,

Plaintiff,

V.

PAUL A. McGINLEY, DISTRICT ATTORNEY,

COUNTY OF LEHIGH, PENNSYLVANIA,

Defendant.

Before: H astie, Circuit Judge; W elsh, Senior District

Judge; and L ord, District Judge.

OPINION.

[Piled December 1, 1959]

By H astie, Circuit Judge.

This case has been tried to a statutory three-judge

court constituted as provided in Sections 2281 and 2284 of

Title 28, United States Code. The plaintiff. Two Guys From

Harrison-Allentown, Inc., seeks an injunction to prevent

the District Attorney of Lehigh County from enforcing

against its employees, and thus against its retail selling

business, the criminal sanctions of the Pennsylvania Sun

day closing laws, sometimes called the Sunday ‘ ‘ blue laws ’ ’.

Continuously since 1957 plaintiff has operated a large de

partment store, employing some 300 persons, in a suburban

( la )

2a Appendix A

area near the City of Allentown in Lehigh County. This

store opens for business on Sunday as well as on the other

six days of the week. About one-third of its business is

done on Sunday.

The pleadings allege and the evidence establishes as a

fact that, prior to a 1959 amendment of the ' ‘blue laws” ,

the defendant had undertaken to enforce against the plain

tiff’s business and its employees the general provision of

the Act of June 24, 1939, P. L. 872, § 699.4, 18 P. S. § 4699.4

that ‘ ‘ whoever does or performs any wordly employment or

business whatsoever on the Lord’s day, commonly called

Sunday (works of necessity and charity only excepted) . . .

shall, upon conviction thereof in a summary proceeding, be

sentenced to pay a fine of four dollars . . . . ” I t is also

alleged and appears as a fact that the defendant is now

threatening to enforce against the plaintiff’s business and

employees Section 699.10 as added to the Sunday closing

law by the Act of August 10, 1959, P. L. 212, 18 P. S.

§ 4699.10, which reads as follows:

‘‘Whoever engages on Sunday in the business of

selling, or sells, or offers for sale on such day at retail,

clothing and wearing apparel, clothing accessories, fur

niture, housewares, home, business, or office furnish

ings, household, business, or office appliances, hard

ware, tools, paints, building and lumber supply ma

terials, jewelry, silverware, watches, clocks, luggage,

musical instruments and recordings, or toys, excluding

novelties and souvenirs, shall upon conviction thereof

in a summary proceeding for the first offense be sen

tenced to pay a fine of not exceeding one hundred dol

lars ($100), and for the second or any subsequent

offense committed within one year after conviction for

the first offense be sentenced to pay a fine of not ex

ceeding two hundred dollars ($200) or undergo im

prisonment not exceeding thirty days in default thereof.

‘‘Each separate sale or offer to sell shall consti

tute a separate offense . . .

Appendix A 3a

The evidence does not show and the court does not find

any present or continuing threat to enforce against plain

tiff’s retail selling the above quoted provision of the 1939

statute, although the defendant has expressed tbe legal

view that both the old Section 699.4 and the new Section

699.10 apply to the situation of the plaintiff.

In these circumstances a question arises at the outset

which affects the scope of proper present inquiry. Since

the 1959 amendment has made the retail sale of specific

categories of merchandise on Sunday a wrong punishable

by a fine of one hundred dollars, does the sale of such mer

chandise continue to be punishable by a fine of four doUars

under the older general prohibition of “ worldly employ

ment or business on Sunday” ?

The 1959 enactment says nothing about the earlier

general prohibition although it was enacted as an amenda

tory addition to Section 699 of the Penal Code in which the

earlier prohibition appears. We think it can reasonably be

argued that the new section supersedes the older one insofar

as the latter covered in generality activities now specifically

dealt with and more severly punished in the amendatory

enactment. Cf. Commonwealth v. Brown, 1943, 346 Pa.

192, 29 A. 2d 793; Commowwealth v. Gross, 1941, 145 Pa.

Sup. 92, 21 A. 2d 238. In any event, here is a substantial

unsettled question concerning the construction of the ques

tioned state legislation. When the Pennsylvania courts de

cide this question they may well resolve it by an interpreta

tion which will relieve the plaintiff and those associated

with it of any punitive action under the 1939 statute.

In such a situation it is our duty to refrain from pass

ing upon the constitutionality of the 1939 statute until the

state courts have made clear whether it applies at all to

the plaintiff -since the 1959 amendment. Harrison v.

N. A. A. C. P., 1959, 360 U. S. 167; Spector Motor Service

V. McLaughlin, 1944, 323 U. S. 101; Railroad Commission v.

Pullman Co., 1941, 312 U. S. 496. Even if the statute were

clear, a court of the United States should, as a matter of

4a Appendix A

policy to minimize interference with state action, refuse

gratuitously to pass on the constitutionality of a provision

of a state law when the plaintiff cannot show present urgent

need for federal intervention to prevent actual or im

minently threatened deprivation of constitutional right.

Plaintiff is in no such jeopardy now under the 1939 statute.

In these circumstances we think it inappropriate to pass

upon the constitutionality of the 1939 statute at this time or

even, as was done in the cases cited above, to hold the case

sub judice pending an interpretative state ruling. I t is

enough to say that our disposition of the present case shall

not bar future resort to this court by the plaintiff if and

when the state courts shall authoritatively decide that the

1939 statute still applies to selling which is covered by the

1959 amendment, and if and when plaintiff’s business shall

be jeopardized by a present threat of prosecution under the

1939 statute. The present adjudication wiU concern the

1959 amendment only.

Plaintiff attacks the Pennsylvania legislation com

manding the cessation of certain worldly activity on Sunday

as state action promoting “ an establishment of religion”

contrary to the prohibition of the F irst Amendment, as

made applicable to the states by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The argument is that this required cessation of busi

ness on Sunday is an enforced expression of respect for

and acknowledgment of the sacred character and religious

symbolism of the Christian Sabbath, a religious institution

commemorating the resurrection of Christ. There is testi

mony which establishes as a fact in this record that this

view of the religious significance of enforced Sunday work

stoppage is sincerely held by many persons whose religion

not does not recognize the divinity or resurrection of Jesus

of Nazareth or the sacredness of Sunday as the “ Lord’s

day” .

At the outset we consider a contention that this F irst

Amendment argument has been foreclosed by authoritative

determinations of the constitutiomdity of Smiday laws es-

Appendix A 5a

sentially similar to the Penasylvania statute. At the turn

of the century, before the Supreme Court had ruled that the

F irst Amendment guarantees are enforceable through the

Fourteenth Amendment against the states,^ Sunday “ blue

laws” were upheld in two familiar decisions of the Court.

Hennington v. Georgia, 1896, 163 U. S. 299; Petit v. Minne

sota, 1900,177 U. S. 164. ̂ If these stood alone their present

authority would be questionable in the light of the develop

ment of constitutional concepts during this century. But

more recently a new test of the constitutionality of Sunday

legislation was sought in an appeal to the Supreme Court

from a conviction under the New York Sunday laws.

Friedman v. New York, 1951, 341 U. S. 907. In the juris

dictional statement filed in the Supreme Court in support

of that appeal the appeUant said: “ The question to be re

solved is an important one: Are Hennington v. Georgia and

Petit V. Minnesota stiU law in view of the Everson and

McCollum decisions” ! Accordingly, it is appropriate that

we examine that case carefully.

The defendants in the Friedman ease, who were Ortho

dox Jews, had been convicted of the retail selling of kosher

meat on Sunday in violation of the New York prohibition

against “ all manner of public selling [except for many

miscellaneous exemptions] . . . upon Sunday . . . . ”

39 N. Y. Consol. Laws, McKinney, 1944, § 2147. The de

fense was carefully planned and organized under the direc

tion of Leo Pfeffer, Esquire, a distinguished advocate and

legal writer who had specialized in the field of religious

1. The ruling as to freedom of religion was first made in 1940

in C a n tw e ll v . C on n ec ticu t, 310 U. S. 296, 303, although first fore

shadowed fifteen years earlier. G itlo w v . N e w Y o rk , 1925, 268 U. S.

652.

2. See also the earlier dictum in S o o n H in g v . C ro w le y , 1885,

113 U. S. 703, 710: “Laws setting aside Sunday as a day of rest are

upheld, not from any right of the government to legislate for the

promotion of religious observances, but from its right to protect all

persons from the physical and moral debasement which comes from

uninterrupted labor.”

6a Appendix A

liberty.® Before the Supreme Court the appellant’s very

explicit statement of “ Questions Presented” read in part

as follows:

“ 1. Whether the New York Sabbath Law (Article

192 of the New York Penal Law) is a law respecting

an establishment of religion and is, therefore, invalid

in its entirety imder the F irst Amendment to the United

States Constitution which is made applicable to the

States by the Fourteenth Amendment.

“ 2. Whether the New York Sabbath Law is con

stitutionally invalid as violative of the freedom of

religion provision of the United States Constitution,

because it fails to exempt from its operations persons

whose religious convictions compel them to observe a

day other than Sunday as their holy day of rest.

‘ ‘ 3. Whether the New York Sabbath Law by reason

of its ‘crazy quilt’ pattern of inclusions and exclusions

is arbitrary and discriminatory and therefore violative

of the ‘equal protection of the law’ and ‘due process’

provisions of the United States Constitution.”

Of course these points were appropriately elaborated.

Moreover, they had been raised at trial and had been con

sidered and decided against the defendants by the highest

court of New York. People v. Friedman, 1950, 302 N. Y.

75, 96 N. E. 2d 184. Indeed, Mr. Pfeffer points out in his

book, and his submission must have made it plain to the

Supreme Court, that this was essentially a test case to

determine the vitality of the doctrine of the Hennington

and Petit cases in the light of contemporary understanding

of the reach of the F irst and Fourteenth Amendments.

There can be no question but that the Supreme Court was

plivinly urged to find in the New York law the very consti-

3. Pfeifer’s CuuRcn, State, anu IhjKKUOM, 1953. discusses

Sunday laws in sjetieral and the F ried m a n case in dehiil at pages

227-241.

Appendix A 7a

tutional infirmities we are now asked to find in the Penn

sylvania law. Yet, without permitting oral argument the

Court disposed of the case in a per curiam opinion dis

missing the appeal and saying merely: “ The motion to dis

miss is granted and the appeal is dismissed for the want of

a substantial federal question.” 341 U. S. 907. In these

circumstances the Friedman case seems to mean that in

the Supreme Court’s view such legislation as the New York

law is so clearly invulnerable to F irst and Fourteenth

Amendment attack that it would not even be useful to permit

further argument of the matter.*

In effect, the Court was content to leave as the law

of the land its old reasoning that “ the legislaure having

. . . power to enact laws to promote the order and to

secure the comfort, happiness and health of the people, it

was within its discretion to fix the day when all labor,

within the limits of the State, works of necessity and charity

excepted, should cease. I t is not for the judiciary to say

4. As early as 1902 the Supreme Court recognized the stare

decisis effect of its per curiam disposition of cases properly appealed

to it. F id e l ity & D e p o s it Co. v . U n ite d S ta te s , 1902, 187 U. S. 315,

319. In more recent times this point has become important in the

administration of the Court’s rules and procedure which require that

an appeal of right from a state court be supported by a jurisdictional

statement, stating “the reasons why the questions presented are so

substantial as to require plenary consideration . . . . ” Rule 15,

par. 1 (e ), 346 U. S. 962. If that showing is insufficient or unper

suasive a per curiam dismissal for want of a substantial federal

question or a summary affirmance of the judgment below follows.

Unless such a dismissal is grounded in some procedural or technical

insufficiency of appellant’s presentation, its meaning seems to be that

the disfwsition of the federal question by the state court was clearly

right. In essence, such a per curiam is likely to be a particularly

emphatic ruling on the merits of the question. The Court itself haa

explicitly recognized such summary rulings as authoritative prece

dents. B a sk in v . In d u s tr ia l A c c id e n t C o m m iss io n , 1949, 338 U. S.

854; N o r th C o a s t T ra n sp o r ta tio n C o. v . U n ite d S ta te s , 1944, 323

U. S. 668. See also the statement of Mr. Justice Brennan, concurring

in E a so n v . P r ic e , 1959, 360 U. S. 246, 247, that, “votes to affirm

summarily and to dismiss ffm want of a substantial federal questkm,

it hardly needs comment, are votes on the merits of a case

8a Appendix A

See Hennington v.that the wrong day was fixed. . .

Georgia, supra, at 304.

As an inferior court asked to hold unconstitutional the

Pennsylvania laws prohibiting certain Sunday retail selling,

we can escape from the obligation to apply the ruling in

the Friedman case only if the Pennsylvania law is so sig

nificantly difiFerent from the New York law that a different

result can be reached and justified without departing from

the legal view for which the Friedman case stands.

I t has been suggested that the New York law differs

significantly from the Pennsylvania law in two respects.

First, the aim to protect the Christian Sabbath from pro

fanation is said to be much plainer in Pennsylvania than in

New York. In this connection, the text of the laws, their

history and their judicial interpretation all are relevant.

The basic Sunday “ blue laws” of Pennsylvania, New York

and many other states today are derived from colonial and

early state statutes which, in turn, had been derived from

British laws designed to require observance and to prevent

profanation of the Christian Sabbath. A hundred years

before the American revolution an English statute pro

hibited any person from engaging in “ worldly labor or

business or work of the ordinary calling on the Lord’s Day,

works of necessity and charity excepted” . 1676, 29 Car.

II, C. 7. The colonial theocracies, among them both New

York and Pennsylvania, adopted markedly similar legisla

tion which they reenacted after they became states of the

United States of xVmerica.® The basic Pensylvania statute

as it has come down to us in Section 699.4 of the codification

of 1939, with its prohibition of “ worldly employment or

business . . . on the Lord’s Day” , has already been set

out. The Now York statute, 39 N. Y. Consol. Laws, McKin

ney, 1944, §2140 begins with this declaration:

5. See the sunmiarv of the evolution of legislation against "Sab-

kUh breaking" in New York frvnn ix>loinaI times in the dissenting

opinioti of jtulge McCarthy in Owc« Koshrr Super Market v. Gal

lagher, n. Mass., 195 )̂, l7o h'. Snpp. 4<ki, 477, 484.

Appendix A 9a

‘ ‘ The first day of the week being by general consent

set apart for rest and religions uses, the law prohibits

the doing on that day of certain acts hereinafter speci

fied, which are serious interruptions of the repose and

religious liberty of the community. ’ ’

Pursuant to this declaration the statute prohibits, among

other things, “ all manner of public selling” except for

miscellaneous exemptions. § 2147. We thing it cannot be

seriously questioned that in their relation to the first day

Sabbath as an institution of Christianity the New York

and Pennsylvania statutes have a common background and

were in original conception designed to the same end. More

over, the involvement of religious considerations appears

clearly on the face of the basic statute in both states.

Local judicial interpretation of the two statutes tells

the same story. In the ease of People v. Dunford, 1912, 207

N. Y. 17, 20, 100 N. E. 433, the Court of Appeals declared:

“ That the legislature has the authority to enact

laws regulating the observance of the Sabbath day and

to prevent its desecration is not, and cannot well be,

disputed. The day is set apart by the statute for

repose and for religious observance; objects which per

tain to the physical and moral well being of the com

munity. As to the acts which should be prohibited, as

disturbances, or profanations, of the Sabbath day, the

legislature is the sole judge.”

Similarly in People v. Moses, 1893, 140 N. Y. 214, 215, this

language appears:

“ The Christian Sabbath is one of the civil insti

tutions of the state, and that the legislature for the

purpose of promoting the moral and physical well

being of the people, and the peace, quiet and good order

of society, has authority to regulate its observance,

and i>revent its desecration by any appropriate legis

lation is unquestioned.”

10a Appendix A

See also People v. Zimmerman, 1905, 95 N. Y. S. 136.

Finally, in the Friedman case itself, the opinion of the New

York Court of Appeals, which was submitted to the Su

preme Court for review, explicitly recognized the religious

origin of the New York statute. 302 N. Y. at 79, 96 N. E.

2d at 186.

We find nothing in the cases discussing the Pennsyl

vania legislation and its background which makes any

plainer the religious considerations which underlie the

adoption of the “ blue laws” of that state and from time to

time have been utilized to justify them. The historical

religious connection is so clear in both state statutes as to

be obvious and indisputable. I t has been stressed that the

Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in upholding the local stat

ute had gone so far as to say that “ Christianity is part of

the common law of Pennsylvania” . Commonwealth v.

American Baseball Club of Philadelphia, 1927, 290 Pa. 136,

138 Atl. 497, 499. But a New York case. People v. Buggies,

1811, 8 Johns 290, went just as far.

Thus, the Supreme Court in the Friedman case was

faced with very substantial indicia of the statute’s relation

to religion, strikingly similar to those appellant urges upon

us now. We can see no basis for reasoning that the Penn

sylvania statute is unconstitutionally related to an estab

lishment of religion without bringing the New York statute

under the same interdiction. Yet, the Supreme Court sus

tained the New York statute summarily. If the view of the

establishment of religion question thus authoritatively

established by the Supreme Court is to be changed it is for

that Court, not an inferior court, to do so. Our conclusion

that the Friedman case has broad and controlling signif

icance on the issue of establishment of religion is contrary

to the view of the majority of the three-judge district court

which recently decided Crown Kosher Super Market v.

Gallagher, D. Mass. 1959, 176 P. Supp. 466. That opinion

disposes of this problem of controlling authority in a brief

footnote which is not elaborate enough to make the court’s

Appendix A 11a

reasoning clear to ns. I t affords no useful critique of our

own analysis wMch indicates that the Friedman precedent

is controlling.

As a separate point the plaintiff urges that the 1959