Brief for Plaintiffs (Draft)

Working File

January 1, 1965

30 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Brief for Plaintiffs (Draft), 1965. d19417f4-6c31-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3bc3a24-fe15-4567-af37-f9bfb392d77e/brief-for-plaintiffs-draft. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

”

8

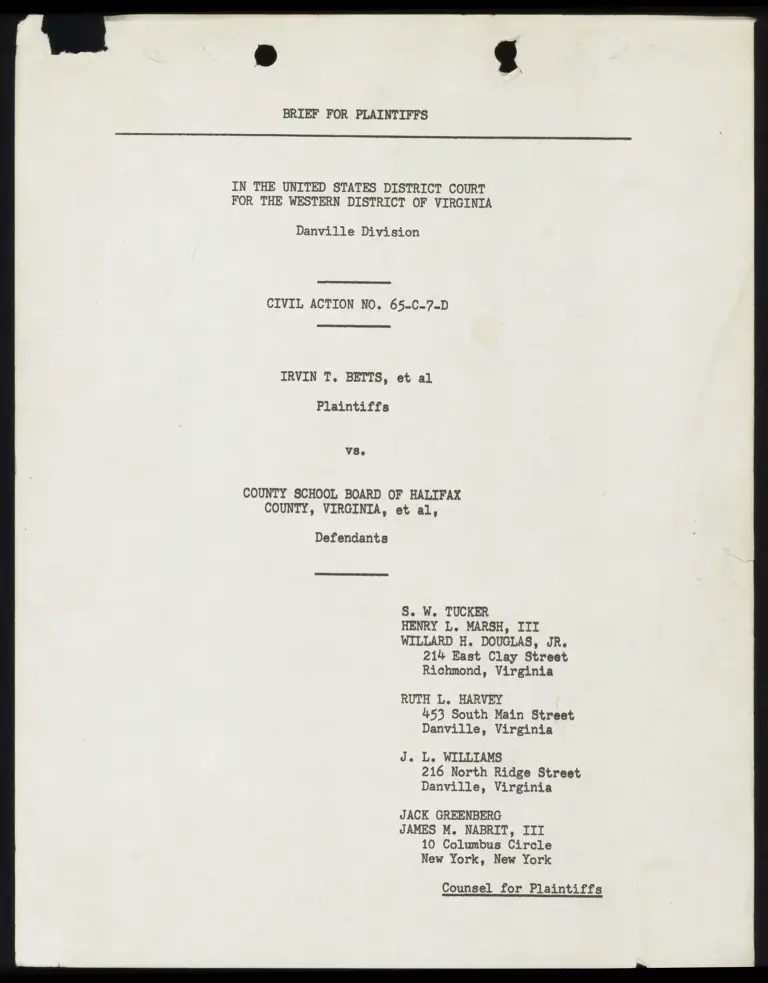

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Danville Division

CIVIL ACTION NO. 65-C-7-D

IRVIN T. BETTS, et al

Plaintiffs

VS

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF HALIFAX

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al,

Defendants

S. W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

WILLARD H. DOUGLAS, JR.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

RUTH L. HARVEY

453 South Main Street

Danville, Virginia

Jo. L. WILLIAMS

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M, NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Counsel for Plaintiffs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE PACTS. cee sore ior wom ouite arse sess arin or ow io vio i es os ps ae veri

THE ISSUES crow ieio ori rms orm me omnes mo me eo sei ero ee oh om so

I. The Defendants Should Be Required To Desegregate

The Faculty And Staff At Each School Prior To The

Beginning Of The 1966-67 School Term —-ee-ecececeeeccee=

ITI. The Halifax County School Board Has A Clear

Constitutional Duty To Establish Unitary Non-

racial School Attendance Areas eewecceccaccccccccame=

A. The Doctrine Of Briggs v. Elliott Must Be

JRO TO RBEL om mommies soineice wi irons so uond io om mo v's ov sn ie aeien

1. The Briggs Doctrine Is Inconsistent

LET BOIL caer sons wooo so eas do sv i mr es avr mo mr eke

2. The Basic Factual and Legal of Briggs

WETS DNSONNA" wore ori wm ime mom so bionims sais ii oi ose aio aioe

3. The Briggs Doctrine Stands Repudiated

By The Fourth Ciroult weecevwmoemwammmmmmmmaes

B. Neither The Doctrine Of Carson Nor The

Dictum In Jeffers Permits Avoidance Of

Decision With Respect To The Defendants' Duty a--

C. The True Meaning Of "All Deliberate Speed"

LB TOW 100 av cement ours ce ra cm i so rw i

Page

10

12

22

TABLE OF CASES

Bell v. School Board of City of Staunton, + . Fo SUuppe coe

( 1966) E50 0) 0 CD CC CC C0 Gh AD GR) A) DD ED CD GR Gh C0 (LC 1 SG Ca VO CS a 0 CD a CB GD 3 G0 LS

Bolling v. Sharpe, M7 U,8, 407 (1954) ewcwecvemsnnosssnonnwcc

Bradley v. School Beard of the City of Righrend,

317 Fold 429 {i001} cnnrdnmrnssn scenic aewmnm esac

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

U5. F228 30 {I088) | wcnmwuunsumncaswsmmmmnmmiscos ese eames

Bradley v. School Board; see UsSe soo (Noo, 415,

November is, 1965) 0 GR DE ee GR OR GED eG GO EE DO LE EB EE A Ch) da

Brewer v. The School Board of the City of Norfolk,

349 F.2d 414 (4th Cir, 1965) FI BE ES OF 0 0 CAD 0 150 GN SN OED GR ID GI ONS BND ORO GE CD SE AE In am ce BS EE)

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (EeDe 8.Co 1955) ecacce=a=

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S.

UBS (101) | ee amencoscrecevinrmeunessesiorcs vrs armen cance

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S.

29M. (1088) | cuumawmsmnascsuncerimrmmse vrs sTe een ——

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

332 Fo2d 452 (1964) cenvnmmmamm EOE) SR Ga a EE LAD SR UE mE Ha 1) I) OR TE OD £30 BE GE = ee ES a

Carson v., Board of Education of McDowell County,

227 Fall 789 {kh Cire 19558) cewmswsmwmenwoasess OS E00 50 ol 6 Gl

Carson ve. Warlick, 238 F, 2d 724 (1956)

Cooper v, Aaron, 388 US: 1 (i958) acuusmmsnwmwessssscccsenmns

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

308 F.2d 920. (1962) PED ED 0 20 ca CD TD GD i BED BR 0 Gl 30 69) GHD £30 OD GR RD) GD G0 GHD GD CN CD RRR GRD ER GD nn ND Cut Ga La

Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

289 P20 439 {Ith Cire 1981) sumwwmmimevonmmammsmmimsmes

“il =

11,18,19

22,23

5,10,22,

24

19

6,7,8,10,

12,13,17,

18,22

7:8,9,12

508,10,

12,23

18,21

Farley v. Turner, 281 F.2d 131 (1960) «cucacceo== cam a woe nn

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) scacccccme=

Green v., School Board of the City of Roanoke,

30H FolBi 118 (108) wuecrxdmmwmsvmmsmancseensmmmamavess

Gilliam v, School Board of the City of Hopewell,

000 U.S, ec 0Qy i5 FI ed 187 (1965) ERR EEE EE Er Sy) EE EE

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 (1964) wD RGD OD SRD CD oR 0 ED ORO OR SOR eR

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 cecucrusmuwnammmccns

Hill v. School Board of the CLty of Jorfelen 282

Hoed v. Board of Trustees, 232 F.2d i (4th Cir.

1956) ED GER OR OD ODE GOR GR OO OO GD OSS Be OR GR OF OD GOD OGD aS Ga OR ED OR OD 6B Go OD a G0 GR ae an

Hood v. Beard of Trustees, 286 F.2d 236 (1961) ccaum=ssms=zse=

Jeffers Vo Whitley, 309 F.2d 621 (1962) CREE CRAnER ES CHW EN EN REN EE ES SS SR ER

Jones ve. The School Board of the City of Alexandria,

278 Te VA 72 (1960) £5 ED ED FDO) GN 60 60 CN) 63 0 £0 60 03 50 6) GR 6) A 0 63 65 0 0 6 65 650 G0) 60 6 60 £0 1 CR SR 6 6)

Kier v. County School Beard of Augusta County,

0660 Fo, Supp. e006 (W, PD. Va. 1966) £5 53 OF 6 GN E068 0 ES SH EH ER GH ERS ER SRR ES EER ER SR ER

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) cescczccmses

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education,

283 Fe. 2d 667 (1960) E20 om 00 SR G3 6 ET OF ON BD a 0 SSO SN 00 60 a 0 EE GD a0 SR SR ED SD 50 me E10 G0 6 60 6D ER

Marsh v, County School Board of Roanoke County,

305 Fr, 2d 94 (1962) SE ERED ER ED) 6 ED ER ER 05 A GR 60 S006 50 6 0 FD 6) 0 a 6) a0 (0 1 Ga AD OR OR ON S06 69) 6 Oe A)

Price v. Denison Independent School District Board

of Education, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir, 1965) cexccccesc=e

Yogezs Vo Paul, 259 9.8, eee li 53% 1 December

School Board of City of Sharlotiesvilie Ve Alen,

- iii ~

20,21

13,16

5,622

19

15

16,20

19

5,6,10,

23,24

i3

Charlottesv:

ERT g

Oo 1 Viam hi cs

LCE 1p 11D g 7

n

l

C

S

DN

)

DD

=

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Danville Division

IRVIN T. BETTS, et al.,

C

c

0

0

o

e

Plaintiffs,

0

CIVIL ACTION

VSe 8

0

NOe 652Ca?-D e

o

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF HALIFAX

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al.,

9

0

o

C

e

o

Defendants, [ 1

]

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Two infant plaintiffs (James Barksdale and Walter D. Carter) and

two infant plaintiff-intervenors (Annie Green and Cynthia Green), all

being Negroes, seek an order to compel the prompt and efficient elimination

of racial segregation from the public school system of Halifax County, "ina

cluding the elimination of any and all forms of racial discrimination with

respect to administrative personnel, teachers, clerical, custodial and

other employees, transportation and other facilities, and the assignment

of pupils to schools and classrooms",

The defendants aver that the infant plaintiffs and all others

eligible to enroll in the public schools "are permitted, under existing

policy, to attend the school of their choice without regard to race sub-

ject only to limitations of space" (Answer, Paragraph 11), that there is

no racial segregation in the schools (Answer, Paragraph 12), that long

before the institution of this suit it had been the policy of the defend-

ants to operate the school system under a "freedom of choice" principle,

and that the school system is being operated in compliance with the re-

quirements of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The evidence shows that of more than 2,000 Negro children of

elementary school classification, only five attend or have ever attended

schools with white children, although elementary school children of both

races are about equal in number and are evenly distributed throughout the

county.

Halifax County has no high schools or junior high athoole its

entire system consists of but nine elementary schools which white children

attend and seventeen elementary schools which none but Negro children attend.

Fourteen of these Negro schools are of primitive, rudimentary construction

(the nineteenth century type of two to five room rural schools) and are to

be abandoned as of September 1966, giving way to modern consolidated schools,

The school authorities anticipate that the children from these schools will

be housed in a 22 room school (Clay's Mill) or in a 17 room school (Mead-

ville) or in a four room addition to Sinai Elementary School, all of which

are scheduled for completion in time for the 1966.67 session,

Prior to May 19, 1965, the school board formally defined the ate

tendance areas for each school, The minutes of the December 7, 1964

meeting spell out meticulously the 1965-66 attendance areas for the newly

constructed South.of-Dan Elementary School and the 1966-67 revisions of the

attendance areas for Sydnor-Jennings Elementary School, for Clay's Mill

1/ A joint board of control operates two high schools which serve separately

the white and Negro students of Halifax County and the Town of South Boston.

Elementary School and for Meadville Elementary School. It was then clearly

the intent of the school board that these schools, together with Sinai ele-

mentary School, would accommodate the Negro children of the county.

Every Negro school child, except five, presently attends the school

serving his area of residence as previously established by the school board

for Negro children. Every white school child presently attends the school

serving his area of residence as previously established by the school board

for white children. All 1965-66 transfer privileges were expressly withheld

from children in the second and higher grades residing in the attendance

areas of twelve of the Negro schools which are scheduled for abandonment.

Some 95 white teachers are employed at schools which white

children attend. Approximately 103 Negro teachers are employed at schools

which Negro children attend, Negro bus drivers canvass the county trans-

porting Negre children to Negro schools, White bus drivers cover the same

territory transporting white children (and presumptively five Negro children)

to white schools.

Several months prior to the commencement of this action on May

18, 1965, the school board received, but took no action upon, a petition of

Negro citizens of the county that it adopt and publish a plan by which all

aspects of racial discrimination would be promptly terminated. On and after

May 19, 1965, the school board has attempted to satisfy the requirements of

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as implemented by the regulations

of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The board has formally

adopted and publicly announced what it here refers to as a freedom of choice

policy. However, the school authorities do not contemplate or expect that

any white parent will voluntarily enrcll his child in any of the schools

which have been set apart for Negroes; neither do they plan to assign Negro

teachers to the schools attended by white children or white teachers to

schools presently characterized as Negro schools.

THE ISSUES

The issues are squarely posed by those of the infant plaintiffs

whose parents failed to make application for the infant®s enrollment in a

school attended by white children, viz

I. Does the Constitution require an immediate distribution of

all teachers among the various schools for the effectuation of nonracial

assignment of personnel?

II. Does the Constitution require a revision of school districts

and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of determining

admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis?

ARGUMENT

The Defendants Should Be Required To Desegregate The

Faculty And Staff At Each School Prior To The

Beginning Of The 1966-67 School Term

The requirement of total faculty desegregation in public schools,

whatever may be the plan of pupil assignment, has recently been underscored

by the Supreme Court in Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

Virginia and in Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Virginia,

soe UeSe seoy 15 L ed 2d 187 (November 15, 1965) and also in Rogers v. Paul,

ooo Us Ss soey 15 L ed 2d 265 (December 6, 1965).

The guidelines for faculty desegregation stated in this Court's

January 5, 1966 opinion in Kier vs. County School Board of Augusta County,

veo Fo Suppe eee (WeD., Va, 1966) are applicable here, The parity in num-

bers of white and Negro teachers in the Halifax County school system makes

imperative the simultaneous desegregation of the faculty and staff at each

school; otherwise there will be an exodus of pupils from the schools with

desegregated faculties to the schools with segregated faculties. Nothing

has been suggested, indeed no valid reason can be suggested, as justifying

any delay in accomplishing total faculty desegregation.

il

The Halifax County School Board Has A Clear

Constitutional Duty To Bstablish Unitary

Nonracial School Attendance Areas

This branch of the argument stems from the directive of Brown II

(Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 29% (1955)) that when enter

taining a school board®s request for postponement of the personal right of

the Negro child, the courts may consider "problems related to « « « re-

vision of school districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a system of determining admission to the public schools on a nonraciai

basis". It does not clash with the statement in Rogers v. Paul, supra,

that "racial allocation of faculty . » renders inadequate an otherwise

constitutional [freedom of choice/ pupil desegregation plan", inasmuch as

the Court expressly stated in the footnote that the constitutional adequacy

of the assignment method chosen for the lower grades was not before the Court

and the method contemplated for the high schools was not a part of the record.

Neither does this argument conflict with the dictum in Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 603, 687 (1963) which suggest that transfers from

established zones or attendance areas might be validly permitted, if they

are entirely free from any imposed racial restrictions. This argument does

attack the doctrine of Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F, Supp. 776 (E.DeS.C., 1955)

upon which this Court’s recent approval of "freedom of choice" in Kier v.

County School Board of Augusta County, supra, admittedly rests.

We here argue the case of the infant plaintiffs whose parents

failed and refuse to exercise the initiative of enroliing the child in a

school attended by white children, Such infants seek the aid of this Court

that they be not denied the equal protection of the laws which is their con-

stitutional legacy. If by virtue of the Equal Protection Clause those in-

fants are entitled to racially non-discriminatory school assignments, then

the remedial order of this Court must run to the defendant state officials,

there being no power in this Court to compel the parents to make the appli-

cation upon which the defendants condition the effectuation of the infant

plaintiffs? rights,

A. The Doctrine of Briggs v. Ellicott Must Be Laid To Rest

1. The Briggs Doctrine Is Inconsistent With Brown

The several arguments for the constitutional validity of "free-

dom of choice" are based upon an unrealistic distinction between the word

"discriminate" (which school boards now concede they may not do) and the

generically included word "segregate" (which school boards yet contend they

may do). Briggs v. Elliott, supra, to the contrary notwithstanding, the sub-

ject of Brown I (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

was racial segregation in public schools.

"In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race * * *

have been denied admission to schools attended by

white children under laws requiring or permitting

segregation according to race,"

The word "segregation" or a word of the same derivation appears in the text

of the opinion at least fifteen times and in the footnotes at least ten

times. The broader term "discrimination" appears but once in the text and

three times in the footnotes (footnote 5), and in this context:

"In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth

Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court

interpreted it as proseribing all state-imposed discrimi-

nations against the Negro race, * * * "The words of the

amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they contain a

necessary implication of a positive immunity, or right,

most valuable to the colored race, - the right to exemption

from unfriendly legislation against them distinctively as

colored, - exemption from legal discriminations, implying

inferiority in civil society, lessening the security of

their enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy, and dis-

criminations which are steps towards reducing them to the

condition of a subject race, * * xw

In Brown I, the Court was considering one form of discrimination, i.e.,

separation of children by race in the public schools "under laws requiring

or permitting segregation according to race" (347 U.S. at 488) and held

articular form of discrimination to be violative of the Equal Pro-

\ avd 3 yrs £71 aye

BCT10Nn LidusSe,

In the companion case of Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954),

wherein racial segregation in the public school system of the District of

£

\ 2 . + Ol 2 YO i ~ ml 2 { 1 rl Spe ruvvamsd 2 con ’ - Rie 2 Columbia was unde: attack, the Court viewed ion as an unjusti-

02 ot Le OEY ART BS. HE, Wy FS rey gall arom mt Phe Hem labile discrimination and, hence, violative of the Due Process Clause of the

Fifth Amendment. No semantic analysis of the 1954 school segregation opine

uggest the Court's unawareness of the obvious fact that racial 0

segregation in the public schools is an invidious discrimination.

In Brown II, the Court was dealing with the cases which came from

the states and the case which came from the District of Columbia and hence

it employed the broader term in its reference to its earlier declarations

of "the fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education

is unconstitutional" and in its conclusion that "/a/11 provisions of federal,

state, or local law requiring or permitting such discrimination must yield

to this prineiple.", The Court's use of the word "discrimination" was not

at "segregation" (viola- intended to, and could not, alter the simple fact th

ting the Equal Protection Clauss) was the sul The term

employed was studledly selected in order that the implementing opinion would

also redress the deprivation of liberty which vitiated racial segregation

in the public schools of the District of Columbia.

Forty-five days later, when "convened to hear any concrete sug-

gestions" of counsel for its decree on the mandate of the Supreme Court, the

three-judge district court in the Eastern District of South Carolina deliver.

Ye | #4 ES PO YY PY AY ATV TIS AY ss kr t k = 8 PO #3 be We ee agg de €d a per curiam opinion (Bri Z8S Ve LLLIOTL, supra) & 111 of which was but

er A I TU or : vow Ym ” = 3 un IRD. apm EAT a I od Bs & 2 re dicta, entirely overlooking the all too significant circumstance that the

Supreme Court had purposefully based its decision in that case (and in the

cases from the other states) on its finding that racial segregation in

public education deprived Negro children of the equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. In Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, the

Court had unmistakably stated the reason for its choice of the Equal Pro-

tection Clause in deciding Brown I, viz:

"The ‘equal protection of the laws’ is a more explicit

safeguard of prohibited unfairness than due process of

law' and, therefore, we do not imply that the two are

always interchangeable phrases." (347 U.S. at 499.)

Nevertheless, the three-judge district court read the Brown cases as if

Brown I had struck down racial segregation merely as a deprivation of liberty

without due process of law; and thus that Court reached the conclusion that

if the schools which the state maintains are "open to children of all races,

no violation of the Constitution is involved even though the children of

different races voluntarily attend different schools; as they attend differ-

ent churches." Continuing in that vein, that district court laid the ground-

work for the concept of Freedom of Choice and its subsequent acceptance by

legislators and some judges.

The Supreme Court might well have disposed of all of the school

segregation cases under the due process concept it found necessary to employ

in Bolling v. Sharpe. Later; in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S, 1 (1958), it

expressly characterized racial segregation of Negro children as a depriva=

tion of their liberty, But in Brown I, it deliberately selected the "more

explicit safeguard of prohibited unfairness" in order to underscore the duty

of state officials to refrain from denying any child the equal protection

of the laws. The Amendment®’s prohibition against such denial clearly casts

upon state officials the burden of full implementation "at the earliest

»

10

practicable date" (Brown II). Denial of the equal protection which the

Constitution guarantees Negro children (the Court avoided the use of the

word "parents" in all opinions) would be tolerated only so long as the

school authorities could prove it to be necessary in the public interest

in the systematic elimination of administrative obstacles, (Brown II)

No opinion of the Supreme Court supports the view that the duty

of state authorities is merely to avoid future discrimination in consider-

ing applications for the attendance of individual children at schools of

their parent®s choice. Bradley v. School Board, coo UsSe oo. (November 15,

1965) vacated the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

and expressed the Court's impatience with delays in desegregation of school

systems, citing three cases containing similar expressions. Again, on

December 6, 1965, that impatience was expressed in Rogers v. Paul, supra.

In Bradley, the Supreme Court reminds us that "more than a decade

has passed since we directed desegregation of public school facilities" P

(emphasis supplied), If the Court had perceived that the Constitution re-

quires no more than that public authority make available to the parents of

Negro children a choice between racially segregated schools and schools

attended by children of both races, it would not have so clearly left the

door open for further judicial review of Richmond's freedom of choice reso-

lution in the light of the present urgency.

2. The Basic Factual And Legal Assumptions Of Briggs

Were Unsound

Where the Briggs opinion says: "Nothing in the Constitution or in

the decision of the Supreme Court takes away from the people freedom to

choose the [public] school they attend," it ignores the fact that prior to

1954, and even when it was being penned, people had no such freedom to

11

choose -- certainly not with respect to the racial composition of the

schools and, as a general rule, not with respect to the location of the

schools,

Prior to the 1954 Brown decision, school authorities promulgated

rules by which parents knew where their children would attend public schools.

In Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (1956) Judge Parker (Judges Sobeloff and

Bryan concurring) wrote:

"Somebody must enroll the pupils in the public schools.

They cannot enroll themselves; and we can think of no one

better qualified to undertake the task than the officials

of the schools and the school boards having the schools in

charge,"

Seven years later; in Bradley I (Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 317 F. 2d 429 (1964)), Judge Boreman (Judges Bryan and Bell con-

curring) again recognized the traditional function of school authorities in

promulgating the rules governing the assignment of students to schools,

sayings

"That there must be a responsibility devolving upon some

agency for proper administration is unquestioned."

The General Assembly of Virginia yet requires that public authority

tell the individual what public school, if any, his child will attend. The

Pupil Placement Act divests certain local schocl boards of authority "to

determine the school /to/ which any child shall be admitted" (Code of

Virginia, 1950, as amended, §22-232.1) and directs the Pupil Placement

Board to "enroll each pupil in a school district so as to provide for the

orderly administration of such public schools, the competent instruction

of the pupils enrolled and the health, safety and general welfare of such

pupils” (Id., 822-232.5)., Where the Pupil Placement Act is not effective,

local school boards make "placements of individual pupils in particular

12

schools so as to provide for the orderly administration of such schools, the

competent instruction of the pupils enrolled and the health, safety, best

interest and general welfare of such pupils" (Id., 822-232.18). "The place-

ment of pupils . » . shall be made by school boards which are hereby author-

ized to fix attendance areas and adopt such other additional rules and regu-

lations . « relating to the placement of pupils as may be to the best

interest of their respective school districts and the pupils therein" (Id.,

§22-232,19)

Where the Briggs opinion says that the Constitution "merely for-

bids the use of governmental power to enforce segregation," it ignores the

equal protection basis of Brown I and the plain directive of Brown II that

the school board, under the supervision of the District Court, "effectuate

a transition to a racially non-discriminatory school system." As Judge

Wisdom has recently observed (Singleton vo Jackson: Municipal Separate School

District, 348 F. 2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965)), Briggs "is inconsistent with Brown

and the later development of decisional and statutory law in the area of

civil rights."

In retrospect, it can now be clearly seen that the doctrine (based

on a misstatement of historical fact and a misconstruction of constitutional

law) has thrived only on official disagreement with and hostility to the

Brown decisions.

3, The Briggs Doctrine Stands Repudiated By The

Fourth Circuit

In the Fourth Circuit, and particularly in Virginia, North Carolina

and South Carolina, much deliberation and little speed attended the first

four years! efforts to implement the constitutional principles enunciated

13

in the Brown decisions. The doctrine of Briggs v. Elliott, supra, justified

school boards? inaction; and the doctrine of Carson v. Warlick, supra, en-

couraged the states to contrive and interpose cumbersome administrative pro.

cedures insulating school boards from effective judicial prodding. The

following and similar procedural guidelines dictated the pace of judicial

supervision of the implementing process:

"All that [federal courts] have the power to do in the

premises is to enjoin violation of constitutional rights

in the operation of schools by state suthorities.”

Carson v. rd of yo, 227 F. 2d

789 (4th Cir, 1955).

"There 1s no question as to the right of these school

children to be admitted to the schools of North Carolina

without discrimination on the ground of race. They are

admitted, however, as individuals, not as a ¢lass or group;

and 1t 1s as individuals that their rights under the Con-

stitution are asserted. Henderson v., United States, 339

U.S, 816, 824," Carson v. Warlick, supra.

"/IJt is for the state to prescribe the administrative

procedure to be followed." Ibid, See, also, H Vo

Board of Trustees, 232 F, 247626 (4th Cir. 195

"/K/dministrative remedies for admission to schools must

be exhausted before application is made to the court for

relief on the ground that its injunction is being vielated,"

School Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F, 2d

(4th Cir. 1956).

Not until September 29, 1958, did the Supreme Court have occasion

io )

to elucidate the meaning of the Brown decisions. (Cooper v. Aaron, si

The portended change in the Fourth Circuit’s opinions came through (after

the January 1959 fall of Virginia®s school closing statutes) in the April

20, 1960 opinion of the Court (Judges Sobeloff, Soper and Haynsworth) in

Jones v. The School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, viz:

"Obviously the maintenance of a dual system of attendance

areas based on race offends the constitutional rights of the

plaintiffs and others similarly situated and cannot be toler

ated. It is not mentioned in the plan of the Alexandria

14

School Board, and we may assume, in the absence of more evidence

than the activation of the plan in the present record affords

us, that the continuance of the dual system is not contemplated.

In order that there may be no doubt about the matter, the

enforced maintenance of such a dual system is here specifically

condemned, However, it does not follow that there must be an

immediate and complete reassignment of all the pupils in the

unite schools of Alexandria. On the other hand, the admonition

in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S, 1, must be borne in mind in deline-

ating the affirmative duty resting upon the school authorities.

The Court said, at page 7:

Under such circumstances, the District Courts were

directed to require "'a prompt and reasonable start

toward full compliance,'" and to take such action as

was necessary to bring about the end of racial segre-

gation in the public schools "'with all deliberate

speed.'" Ibid. Of course, in many locations, obedience

to the duty of desegregation would require the immedi.

ate general admission of Negro children, otherwise

qualified as students for their appropriate classes,

at particular schools. On the other hand, a District

Court, after analysis of the relevant factors (which

of course, excludes hostility to racial segregation),

might conclude that justification existed for not re.

quiring the present non-segregated admission of all

qualified Negro children. In such circumstances,

however, the courts should scrutinize the program of

the school authorities to make sure that they had

developed arrangements pointed toward the earliest

practicable completion of desegregation, and had

taken appropriate steps to put their program into

effective operation. It was made plain that only a

prompt start, diligently and earnestly pursued, to

eliminate racial segregation from the public schools

could constitute good faith compliance. State

authorities were thus duty bound to devote every effort

toward initiating desegregation and bringing about

the elimination of racial discrimination in the public

school system, ?®

"The two criteria of residence and academic preparedness,

applied to pupils seeking enrollment and transfers, could be

properly used as a plan to bring about racial desegregation

in accordance with the Supreme Court'’s directive, The record

in this case is insufficient in demonstrating that the criteria

were so applied. On the other hand, these criteria could be

used in such a way as to be a vehicle for frustrating the con-

stitutional requirement laid down by the Supreme Court. If

this is later shown to be the case, then the action of the

School Board would not escape the condemnation of the courts.

If the criteria should be applied only to Negroes seeking

15

transfer or enrollment in particular schools and not to white

children, then the use of the criteria could not be sustained.

Or, if the criteria are, in the future, applied only to appli-

cations for transfer and not to applications for initial en-

rollment by children not previously attending the city's

school system, then such action would also be subject to attack

on constitutional grounds, fo by reason of the existing

segregation Pattern it will be Negro children, primarily, who

seek transfers."

The opinion in Jones ushered in a new era. School authorities

were on notice that inaction on their part would not suffice. The school

board was told clearly and distinctly that it had an "affirmative duty . . »

to bring about the end of racial segregation in the public schools"; al-

though the immediate accomplishment of a "complete reassignment of all the

pupils in the public schools" was not then required, inasmuch as the Court

perceived that nondiscriminatory execution of the school board's plan would

accomplish desegregation of the pupils within a time which the Court then

deemed reasonable, The September 9, 1960 opinion in Hill v. School Board

of the City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473, added the suggestion that the

"District Judge should from time to time be informed more specifically about

the time table contemplated by the Board, and such a time table would aid

he the the Judge in determining whether to give approval tc the Board's subsequent

plans and conduct."

The Court began to take a realistic view of the "administrative oo

remedies" which loctrine had spawned.

ettled that administrative remedies need not

be sought if they are inherently inadequate or are applied

in such a way as in effect to deny the petitioners their

rights." Ney v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283

F, 2d 667 (1960), See, also, Farley vs Turner, 281 F, 2d

131 (1960), Dodson v. School Board of the City of Charlottes-

ville, 289 F. 2d 439 (1961), Hood v. Board of Trustees, 286

D

Jal 2d 236 (1 961),

16

"As the defendants have disavowed any purpose of using their

assignment system as a wehicle to desegregate the schools

and have stated that there was no plan aimed at ending the

present practices which we have found to be discriminatory,

this case is quite unlike Hill v. School Board of the City

of Norfolk, Virginia, 282 F, 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960), and

Dodson v, School Board of City of Charlottesville, Virginia,

289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961). In those cases, the assign-

ment practices were defended as interim measures only and

the district courts, recognizing the infirmities in the

existing practices, made it clear that progress toward a

completely non-discriminatory school system would be in-

sisted upon." Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke,

304 F, 2d 118 (1962), See also Marsh v. County School

Board of Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (1982).

The new departure represented by Jones and Hill met its test in

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 308 F. 2d 920 (1962).

The majority (Judges Sobeloff, Boreman and Bell), adopting an opinion pre-

pared by Senior Judge Soper, adhered to the Cooper v, Aaron interpretation

of Brown and the Jones v. School Board of Alexandria approach to its imple-

mentation. In striking down Charlottesville's "racial minority" transfer

exception to its geographical assignment plan, the Court stated its position,

viz

"In our view the Charlottesville plan in respect to the

pupils in the elementary schools is clearly invalid despite

the defense that the rules for the assignment and transfer

of pupils are literally applied to both races alike, It is

of no significance that all children, regardless of race,

are first assigned to the schools in their residential zone

and all are permitted to transfer if the assignment requires

the child to attend the school where his race is in the

minority, if the purpose and effect of the arrangement is to

retard integration and retain the segregation of the races

(emphasis supplied). That this purpose and this effect are

inherent in the plan can hardly be denied. The School Board

is well aware that most of the Negro pupils in Charlottes-

ville reside in the Jefferson zone and that under the operation

of the plan white children resident therein will be trans-

ferred as a matter of course to the schools in the other zones

while the colored children in the Jefferson zone will be denied

this privilege. The seeming equality of the language is

delusive, the actual effect of the rule is unequal and dis-

criminatory., It may well be as the evidence in this case

17

indicates that some Negroes as well as whites prefer the

schools in which their race predominates; but the wishes

of both races can be given effect so far as is practicable

not by restricting the right of transfer but by a system

which eliminates restrictions on the right, such as has

been conspicuously successful in Baltimore and in Louis-

ville."

Judge Bryan (Judge Haynsworth concurring in his dissent) took issue with

two premises (material here) on which the Court's holding was necessarily

based, viz: that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees integrated schools

and that the segregation in Charlottesville resulted from the racial

minority transfer provision. Citing Briggs v., Elliott, supra, and other

opinions which antedated Cooper ve. Aaron, supra, he harks back to Judge

Parker's assertion that the Supreme Court was explicit in not requiring

integration but in merely striking down denial of rights through segrega-

tion (308 F. 2d 920). Furthermore, Judge Haynsworth (Judge Bryan concurring

in his dissent) thought that the District Court was justified in permitting

racial minority transfers out of consideration for the problems likely to

be incurred by children "compelled to attend a school or classes in which

all others are of the opposite race."

However, the decision of the Supreme Court in Goss v. Board of

Education; 373 U.S. 683 (1963), and the denial of certiorari in School Board

of Charlottesville, Virginia vs. Dillard, 374 U.S. 827 (1963) clearly vindi-

cated the position of the Fourth Circuit that the Fourteenth Amendment does

require racial integration of public school systems and that any plan or

arrangements "the purpose and effect of which is to retain the segregation

of the races" should meet judicial condemnation.

The law of the Fourth Circuit as firmly established by the judgment

in Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, supra, clearly

18

repudiates the Briggs dictum that the Constitution does not require integra-

tion, In Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County, 332 F, 2d 452

(1964), the District Court had refused an injunction and entered order of

dismissal, "believing the case to be moot because all of the individual

infant plaintiffs were in schools chosen by their parents or legal guardians

The opinion reviews the many earlier decisions pointing to "the obligation

of local school authorities to take affirmative action." Following its ob-

servation that Cooper v. Aaron, supra, interpreted the Brown decisions as

requiring state authorities "to devote every effort toward initiating deseg-

regation and bringing about the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public school system," the Court made this significant and compelling

observation:

"It is these school officials, not the infant plaintiffs

or their parents, who are familiar with the operation of

the school system and know the administrative problems

which may constitute the only legitimate ground for with-

holding the immediate realization of constitutionally

guaranteed rights."

Today, the judgment of Fourth Circuit in Bradley II (Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310 (1965)) having been

vacated, we think it unquestionable that the repudiation of the Briggs

doctrine stands as the law of the Circuit. In footnote 5 of the opinion in

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, supra, a panel con-

sisting of Judges Hutcheson, Brown and Wisdom, speaking through the latter,

made this long overdue statement:

"In retrospect, the second Brown opinion clearly imposes

on public school authorities the duty to provide an inte-

grated school system. Judge Parker's well-known dictum

(‘The Constitution, in other words, does not require

integration. It merely forbids discrimination.') in re

Briggs v. Elliott, E.D%8.C. 1955, 132 F, Supp. 776, 777,

should be laid to rest. It is inconsistent with Brown

19

and the later development of decisional and statutory

law in the area of civil rights."

(The footnote accents the Courts! observation that the concept of "all de-

liberate speed" was not based onthe degree of community hostility but "on

the administrative problems im making a transition from a segregated to an

integrated system",)

When, on July 30, 1965, the Fourth Circuit remanded Brewer v.

The School Board of the City of Norfolk, 349 F. 2d 414, it admonished recon-

sideration "in light of the more recent decisions in this and other courts."

Singleton v. Jackson, supra, and Price v. Dennison, 348 F, 2d 1010 (5th Cir.

1965) were the latest opinions. It is clearly apparent that the foregoing

quotation from Singleton is consistent (and that the Briggs dootrine is in-

consistent) with the view of the Supreme Court expressed in Louigiana v.

United States, 380 U.8. 145, 154 (1965) (quoted by Judges Sobeloff and Bell

conditionally concurring in Bradley II) that "the court has not merely the

power but the duty to render a decree which will so far as possible elimi

nate the disoriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like disorimiy |

nation in the future" and that district courts are completely justified in

taking steps "to eradicate past evil effects and to prevent the eentinuatien

or repetition in the future of the diseriminatory practices," shewn to be

80 deeply engrained in the laws, policies and traditions of the state.

Be

If, as stated in Briggs, the Constitution merely gives the indie

vidual Negro school child the right (but only upon application) to attend

public school with white children similarly situated, then the Carson cases

20

properly require that state administrative procedures realistically enforc-

ing such right to exhausted. But if the basic position of the plaintiffs,

particularly those for whom no individual applications have been made, be

sound -- that is, if the Equal Protection Clause requires the school authori-

ties to provide a school system from which racial segregation and all other

state imposed forms of racial discrimination have been extirpated -- then

there is no state administrative procedure through which the resulting right

of each and all of the infant plaintiffs to be educated in such a system can

be enforced, In this case, assuming the duty and the correlative right,

there has been a demand and a refusal and an action seeking enforcement of

the right by an injunction commanding performance of the duty.

We are confronted with a dictum in Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F, 2d

621 (1962), that "the plaintiffs are not entitled to an order requiring the

general intermixture of the races in the schools." In that case, as well,

as in the other cases where variations on the same theme are stated, there

was no one before the court representative of the class of Negro children

by whom or on whose behalf no application had been made to attend a particu-

lar school. Either voluntarily or under pressure from the Distriet Court,

each infant litigant had accepted the Briggs doctrine and assumed the posture

of one whose application had been wrongly refused, The decision of the

Court of Appeals in Jeffers, supra, (comparable to its earlier decisions in

Green v. School Beard of City of Roancke, supra, and Marsh v. County School

Board of Roanoke County, supra, and its decisions in other cases) was that

Negro pupils could not be required to exhaust their administrative remedies

under the North Carolina Pupil Placement Act, because as administered by the

defendants, this remedy had been employed as a means of perpetuating

21

segregation and denying constitutionally protected rights, and was there-

fore inadequate and discriminatory; that each of the Negro pupils who had

applied for admission to a white school should be admitted to such school;

that the seven appellants, including the two who had been admitted to the

white school by the District Court were, on behalf of others similarly

ituated, entitled to an order enjoining the school board from refusing ad-

mission to any school of any pupil because of the pupil?s race, such in-

Junction to remain in effect until the school board might adopt and the

istrict Court might approve some other plan for the elimination of racial

segregation. The Court did not there hold that adoption of the suggested

freedom of choice would constitute full compliance with the Constitution.

The only case which has been before the Fourth Circuit in which

there were litigants who had not made application to attend a particular

school is Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County, supra. There

the Court unequivocally stated and restated the duty of the school board

to "formulate plans for desegregation.” The case was remanded for early

proceedings upon the prayer for an injunction against the operation of a

bi-racial school system, with strong indication that there seemed to be no

obstacle to the abandonment of racial segregation with the beginning of the

next school term,

The notion that "the Constitution does not require integration"

or, as expressed in Jeffers, that "the plaintiffs are not entitled to an

order requiring the general intermixture of the races in the schools," may

have been related to the reluctance of federal courts to enter mandatory

injunctions to protect constitutional rights. The propriety of and the

necessity for the entry of such injunction to compel compliance with the

»

: ®

22

Equal Protection Clause are now manifest in Griffin v. County School Board

of Prince Edward, 377 U.S. 218 (1964).

Coe The True Meaning Of "All Deliberate Speed"

Is NOW

In its several opinions in this area of litigation, this Court has

labered to reconcile the varying and inconsistent decisions and judicial ex-

pressions which the Briggs doctrine has spawned. Although the Augusta County

opinion properly requires the schocl board to "overcome the discrimination

of the past" with respect to the assignment of school teachers (manuscript

p. 16), it recognizes that "freedom of choice" with respect to students

imposes upon Negro parents "the burden of desegregating" (p. 15) a burden

which the federal judiciary is powerless to compel any parent to shoulder.

The impotent stance necessarily follows if following Briggs v. Elliott, we

permit the school authorities now to become "color blind" (p. 6) when

dealing with children whom they have heretofore racially segregated. If

Briggs v. Elliott is competent to overcome the factual basis for Brown I

(the damage which racial separation inflicts upon minority children), then

(and only then) we may rightly reach for Pilate’s bowl,

If; on the other hand, the Equal Protection Clause as elucidated

in the Brown decisions requires the "more explicit safeguard of prohibited

unfairness" (Bolling v. Sharpe, supra), then the duty of the school board

"to overcome the discrimination of the past" (Kier v. County School Board

of Augusta County, supra) applies with primary emphasis to the assignment

of children to schools. In Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

supra, the Supreme Court did vacate the Fourth Circuit's (majority) accept-

ance of freedom choice as a legal desegregation of the public schools and

23

thils made possible future appellate review of freedom of choice unfettered

by segregated faculties. In Rogers v., Paul, supra, the Supreme Court ex-

pressly refrained from passing on the constitutional adequacy of freedom

of choice. Today, the District Court writes on a clean slate with respect

to the constitutional adequacy or inadequacy of freedom of choice as a

means of desegregating the children in the public schools of a particular

locality.

The test of the constitutional adequacy of any plan, whether free-

dom of choice or zoning, with or without restricted or unrestricted trans-

fer privileges; is the speed and efficiency with which students will be re-

lieved of racial separation in the public schools. Brown II directs a

balancing between (1) the immediate right of each child and (2) the system-

atic and effective removal of obstacles to the effectuation of the immediate

rights of all children. No other consideration is valid.

In the Augusta County case and in Bell v. School Board of the City

of Staunton (W.D, Va, January 5, 1966), this Court has recognized that in v

rural areas and in other communities where people of both races are generally

scattered, integration can be brought about immediately and with a minimum

of administrative difficulties though geographic assignment. This Court

recognizes, as did Judges Sobeloff and Bell concurring separately in Bradley

II, that the adoption of freedom of choice is, at best, hardly a step toward

school desegregation, There is testimony in this case (the truth of which

all will concede) that it is considered unlikely that any white parent will

voluntarily enroll his child in the schools which have been set apart for

Negro children, The showing is that only five Negrec children are now en-

rolled in schools which have been set aside for white children. Since the

»

: pM

2k

commencement of this action, the defendants have selected and retained free-

dom of choice because they appraise it as being the means least likely to

accomplish desegregation, A similar appraisal by the Court would require

judicial condemnation of the plan for Halifax County.

Again and again the Supreme Court has warned that the true meaning

of "all deliberate speed" is NOW. (Watson wv. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526

(1963), Griffin v. County School Beard of Prince Edward, supra., Bradley V.

School Board, ees UeSs ose, supra., and Rogers v, Paul, supra.)

"Given the extended time which has elapsed, it is far

from clear that the mandate of the second Brown de-

cision requiring that desegregation proceed with ‘all

deliberate speed’ would today be fully satisfied by

types of plans or programs for desegregation of public

educational facilities which eight years ago might have

been deemed sufficient. * * * Basic to the remand was

the concept that desegregation must proceed with all

deliberate speed’, and the problems which might be con-

sidered and which might justify a decree requiring eome-

thing less than immediate and total desegregation were

severely delimited." Watson v., City of Memphis, supra.

Respectfully submitted,

Se, \ Eat i

or r Plaintiffs Of Counsel fo

S, W, TUCKER

HENRY L, MARSH, III

WILLARD H. DOUGLAS, JR,

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

RUTH L. HARVEY

453 South Main Street

Danville, Virginia

Jo. Lo WILLIAMS

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M, NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York: . 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE

I certify that on the day of January, 1966,

b)

rs

I mailed a copy

of the foregoing Brief for Plaintiffs to counsel for defendants, viz

Frederick T. Gray, Esquire, Williams, Mullen and Christian, 1309 State-

Planters Bank Building, Richmond, Virginia, and Don P. Bagwell, Esquire,

Halifax, Virginia.