Sattler v NYC Commission of Human Rights Notice of Motion for Leave as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 8, 1989

47 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sattler v NYC Commission of Human Rights Notice of Motion for Leave as Amicus Curiae, 1989. 098579aa-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3e84863-0275-4d35-a3f6-10d36f58c119/sattler-v-nyc-commission-of-human-rights-notice-of-motion-for-leave-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

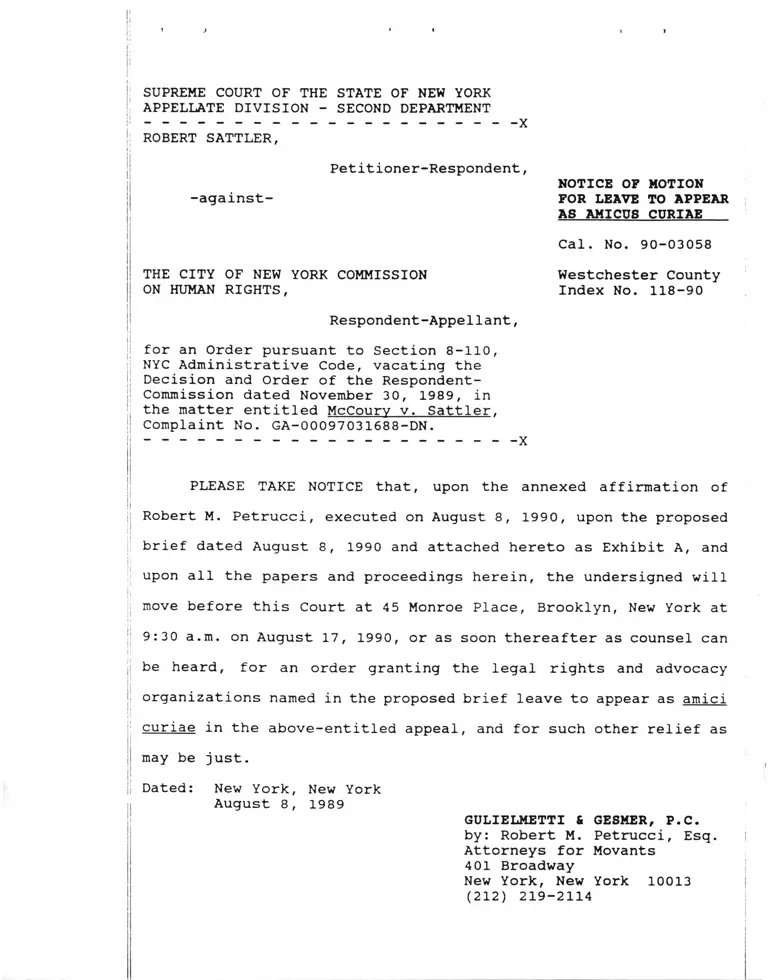

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION - SECOND DEPARTMENT

ROBERT SATTLER,

X

Petitioner-Respondent,

NOTICE OF MOTION

-against- FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Cal. No. 90-03058

THE CITY OF NEW YORK COMMISSION Westchester County

ON HUMAN RIGHTS, Index No. 118-90

Respondent-Appellant,

for an Order pursuant to Section 8-110,

NYC Administrative Code, vacating the

Decision and Order of the Respondent-

Commission dated November 30, 1989, in

the matter entitled McCourv v. Sattler.

Complaint No. GA-00097031688-DN.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ x

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that, upon the annexed affirmation of

Robert M. Petrucci, executed on August 8, 1990, upon the proposed

brief dated August 8, 1990 and attached hereto as Exhibit A, and

upon all the papers and proceedings herein, the undersigned will

move before this Court at 45 Monroe Place, Brooklyn, New York at

9:30 a.m. on August 17, 1990, or as soon thereafter as counsel can

be heard, for an order granting the legal rights and advocacy

organizations named in the proposed brief leave to appear as amici

curiae in the above-entitled appeal, and for such other relief as

may be just.

Dated: New York, New York

August 8, 1989

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

by: Robert M. Petrucci, Esg.

Attorneys for Movants

401 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-2114

TO: HASHMALL, SHEER, BANK & GEIST

Attorneys for Petitioner-Respondent

Attn: Jay Hashmall, Esq.

235 Mamaroneck Avenue

White Plains, New York 10605

(914) 319-4000

VICTOR A. KOVNER, Corporation Counsel

Attorneys for Respondent-Appellant

Attn: Tim O 'Shaughnessy, Esq.

Attorneys for Respondent-Appellant

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

(212) 566-6040

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION - SECOND DEPARTMENT

ROBERT SATTLER,

X

Petitioner-Respondent,

-against-

AFFIRMATION IN

SUPPORT OF MOTION

FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Cal. No. 90-03058

THE CITY OF NEW YORK COMMISSION

ON HUMAN RIGHTS,

Westchester County

Index No. 118-90

Respondent-Appellant,

for an Order pursuant to Section 8-110,

NYC Administrative Code, vacating the

Decision and Order of the Respondent-

Commission dated November 30, 1989, in

the matter entitled McCourv v. Sattler.

Complaint No. GA-00097031688-DN. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ x

ROBERT M. PETRUCCI, an attorney duly authorized to practice

in the courts of the State of New York, affirms that the following

is true under penalties of perjury pursuant to CPLR §2106:

1. I am associated with Gulielmetti & Gesmer, P.C.,

attorneys for the movants who are the legal rights and advocacy

organizations named on the cover of the proposed brief which is

attached as Exhibit A and I am fully familiar with the facts and

circumstances set forth in this affirmation.

2. I submit this affirmation in support of the instant

application by movants for leave to appear as amici curiae in the

above entitled matter.

3. This is an appeal from a decision and judgment of the

Supreme Court, Westchester County (Rosato, J-), granting

1

i l i

I!

respondent 's petition and vacating appellant's decision and order

which had determined that respondent had committed a

||

I discriminatory act in violation of the New York City Human Rights

Law. (A true copy of the lower court's decision and judgment !

entered on or about March 21, 1990 is attached hereto as Exhibit

B.)

4. Appellants served respondent with a Notice of Appeal

from each and every part of the March 21 Judgment on or about

April 6, 1990. (A true copy of the Notice of Appeal is attached

i j hereto as Exhibit C.)

5. Movants seek leave to appear as amici in this appeal

because it raises two questions of law which are of great

importance to the members of their organizations and/or to the

I

clientele whom they serve.

6. The first is whether, as a matter of law, a dentist'sj

office may never be a public accommodation as that term is defined

in the New York City Human Rights Law.

7. The second is whether the dental office of petitioner-

respondent, who accepts clients by referral, is "distinctly

.I private" as the phrase is defined in the law and, therefore,

exempt from the prohibitions against certain forms of

;

'j discrimination.

8. The movant organizations are state and nationwide legal ;

j rights and advocacy groups which have long histories of protecting

! and furthering the rights of individuals specifically covered by

the Human Rights Law. Collectively, they represent all classes of

I!

2

individuals which the New York City Council has explicitly

determined require special legal protection because blatant and

subtle discrimination has historically prevented these individuals

from gaining equal access to public accommodations.

9. It is movants' desire to ensure that the Human Rights

Law be given the full effect intended by the City Council. The

Court below held that a dentist's office is not a public

| accommodation under the city law. This position and the court's

reasoning in arriving at that conclusion will severely restrict

the number and type of establishments which are subject to the

anti-discrimination requirements.

i

10. Additionally, a finding that petitioner-respondent's

office is "distinctly private" and, therefore, exempt from

regulation will severely broaden the number and type of

establishments which are exempt from the law.

11. The construction which this Court gives to the statute

in this appeal will be critical to movants' ability to secure

equal access to public accommodations for all citizens.

12. Because this Court's decision can have such a

significant impact on their ability to carry out their work,

movants seek an opportunity to present to the Court arguments in

support of respondent-appellant why the judgment below should be

reversed.

13. Given the nature of movants' work, they have a

particular familiarity with the Human Rights Law and its history

and an expertise gained from direct participation in hundreds of

3

individual cases over decades concerning the application of laws

banning discrimination in public accommodations.

14. Movants have recently been granted leave to appear as

arcici curiae in cases involving similar issues by the Appellate

Division, First Department, in Hurwitz v. N.Y.C. Commission on

Human Rights, ___ A.D.2d ___, 553 N.Y.S.2d 323 (1990) and by the

Appellate Division, Third Department, in Elstein v. State Division

of Human Rights. ___ A.D.2d ___, 555 N.Y.S.2d 516 (1990).

15. Appellant's counsel stated to me that he would agree to

any reasonable extension of respondent's time to file his brief

which may be necessary as a result of granting this motion, so as

not to cause respondent any prejudice.

WHEREFORE, I believe that the attached brief to be submitted

will be of special assistance to this Court and I respectfully

request that the groups named and described in the brief be

granted leave to appear as amici curiae in this appeal.

Dated: New York, New York

August 8, 1990

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION - SECOND DEPARTMENT

ROBERT BATTLER,

X

Petitioner-Respondent,

-against- Cal. No. 90-03058

THE CITY OF NEW YORK COMMISSION Westchester County

ON HUMAN RIGHTS, Index No. 118-90

Respondent-Appellant,

for an Order pursuant to Section 8-110,

NYC Administrative Code, vacating the

Decision and Order of the Respondent-

Commission dated November 30, 1989, in

the matter entitled McCourv v. Sattler.

Complaint No. GA-00097031688-DN.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ x

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS, THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL

RIGHTS, DISABILITY ADVOCATES, INC., THE LAMBDA LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, THE LEGAL ACTION CENTER OF

THE CITY OF NEW YORK, INC., LEGAL SERVICES FOR THE

ELDERLY, NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.,

THE NATIONAL EMERGENCY CIVIL LIBERTIES COMMITTEE, THE

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD, THE NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, THE PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC. AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

APPELLANT

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

401 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-2114

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION

AIDS PROJECT

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD

55 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10013

(212) 966-5000

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................. 1

INTRODUCTION .......................................... 8

ARGUMENT

THE NEW YORK CITY HUMAN RIGHTS LAW

PROHIBITS RESPONDENT FROM REFUSING TO

TREAT A PATIENT SOLELY BECAUSE THE

PATIENT HAS A I D S ................................. 11

A. A DENTIST'S OFFICE IS A PUBLIC

ACCOMMODATION UNDER THE HUMAN RIGHTS LAW. . 12

1. A dentist's office is an "establishment

dealing in...services" within the

meaning of the phrase as used in the

statute................................. 15

2. A dentist's office is a "clinic" within

the meaning of the term as used in the

statute......................... 19

3. A statutory interpretation which holds

that a dentist's office is a public

accommodation furthers the purpose

underlying the Human Rights Law. . . . 21

4. Courts and agencies, both in and outside

of New York have held that dentist's

offices are public accommodations. . . . 23

B. RESPONDENT'S DENTAL OFFICE, WHICH ROUTINELY

ACCEPTS AS NEW PATIENTS MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL

PUBLIC ON AN INDIVIDUALIZED FEE-PAYING BASIS,

IS NOT EXEMPT AS DISTINCTLY

PRIVATE........................................ 2 5

CONCLUSION 37

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici are legal rights and advocacy organizations committed to

protecting and furthering the rights of individuals specifically

covered by the New York City and New York State Human Rights Laws.

Collectively, amici represent all of the classes of individuals

whom the New York City Council and the New York State Legislature

have determined require special statutory protection from

discrimination because they have suffered and continue to suffer

both blatant and subtle discrimination which has prevented them

from participating fully in the social life and economic

opportunities of this City and State.

The AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION is a nonprofit corporation

founded in 1920 for the purpose of maintaining and advancing civil

liberties in the United States without regard to political

partisanship. It is composed of more than 200,000 members across

the country. The New York Civil Liberties Union is its New York

affiliate. The American Civil Liberties Union has been involved in

numerous federal and state cases concerning the right of privacy,

due process of law, the right to equal treatment under the law,

freedom of speech and expression, equal access to public

accommodations, and other issues of civil rights and liberties.

The AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS has sought to combat all forms of

invidious discrimination ever since its founding in 1918. In 1946

and again in the late 1960's, it participated in the drafting and

1

enactment of New York's anti-discrimination law and brought some of

the first cases under that law.

The ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND (AALDEF)

is a fifteen year old civil rights organization committed to equal

opportunity. AALDEF's program priorities include voting rights,

immigration rights, elimination of anti-Asian violence, labor and

employment rights, housing, health care and land use. In its view,

this case presents issues critical to providing fair and equal

access to dental care for thousands of Asian Americans.

The CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS (CCR) was founded in 1966

as a not-for-profit tax exempt legal and educational organization.

Since that time, it has provided representation and assistance free

of charge to individuals and organizations who seek to bring major

constitutional cases. CCR has been actively involved in the

defense of the rights of minorities, women, gay men and lesbians,

political dissenters, and others who have been denied their rights

under the federal and state constitutions and other laws.

DISABILITY ADVOCATES, INC. was founded in 1987 as a not-for-

profit tax exempt organization for the purpose of providing

advocacy services for people with disabilities. It receives a

grant from the New York State Commission on Quality of Care for the

Mentally Disabled to protect and advocate for the rights of persons

diagnosed as mentally ill and provides protection and advocacy

services in the Hudson Valley Region pursuant to the Protection and

2

Advocacy for the Mentally 111 Individuals Act of 1986, 42 U.S.C.

Section 10801.

The LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. ("Lambda"),

was founded in 1973 as a New York not-for-profit corporation to

protect the civil rights of homosexuals and to initiate or join in

judicial and administrative proceedings whenever legal rights and

interests of significant number of homosexuals may be affected.

Lambda has participated as counsel or amicus curiae in numerous

cases involving the legal rights of lesbians, gay men, and people

with AIDS or HIV-related conditions in state and federal courts

across the country, including several leading cases in New York

concerning HIV- and AIDS- related discrimination.

As an organization representing the lesbian and gay

community's belief in broad and rigorous enforcement of human

rights laws, Lambda has a strong interest in the outcome of this

particular case and in the development of legal precedents that

eliminate discriminatory denials of dental care to people with

AIDS, lesbians and gay men.

The LEGAL ACTION CENTER OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK, INC. is a

public interest organization, one of whose primary purposes is to

make effective the protections against discrimination based on

disability - especially AIDS - that are conferred by the Human

Rights Law. Litigation by the Center has helped to clarify the

scope of the Human Rights Law and ensured that its broad remedial

purposes are given practical effect.

3

The Center has a special commitment, supported by a grant from

the State AIDS Institute, to ensure that persons with AIDS have

access to essential services and overcome barriers to health care

caused by discrimination. Thus, the Center is vitally interested

in ensuring that this case is resolved in a manner that properly

reflects and advances the State's commitment to eradicating

disability-based discrimination, and to ensuring equal access to

dental care for those with the particular disability of AIDS.

LEGAL SERVICES FOR THE ELDERLY (LSE) is the oldest legal

services program for the elderly in the United States. LSE

represents the elderly poor throughout the New York City area and

has as its special focus the frail and disabled elderly. LSE was

instrumental in drafting the "Patients' Bill of Rights," and has

litigated on behalf of the elderly in both state and federal courts

to protect their rights to medicare and medicaid benefits and to

secure adequate health care for homebound patients.

LSE' s clients have a deep and continuing interest in this

case. The disabled elderly are particularly dependent on the

services provided by dentists in their neighborhoods as they are

often unable to travel and are often in need of frequent dental

attention. The result in this case will directly affect the

ability of LSE1s clients to obtain access to necessary dental care

for its clients.

The NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. is a non

profit corporation organized under the laws of the State of New

4

York in 1939. It was formed to enable Black Americans to secure

their constitutional and civil rights through the prosecution of

lawsuits. For many years, the Legal Defense Fund's attorneys have

represented parties and participated as amicus in federal and state

courts nationwide. The Fund has a long-standing interest in the

scope of statutes that ban discrimination in public accommodations.

One of the most severe and demeaning practices inflicted on Black

citizens for many years was their exclusion from facilities open to

members of the public who were white. In addition, discrimination

against Blacks in the furnishing of medical care has been a long

standing and persistent problem. Therefore, the question of

whether a private dental office is a place of public accommodation

under New York state law is of importance to the Fund's ability to

vindicate the rights of its clients.

The NATIONAL EMERGENCY CIVIL LIBERTIES COMMITTEE is a not-for-

profit organization dedicated to the preservation and extension of

civil liberties and civil rights. Founded in 1951, it has brought

numerous actions in the federal courts to vindicate constitutional

rights. From time to time, the National Emergency Civil Liberties

Committee submits amicus curiae briefs to the courts when it

believes issues of particular import to civil liberties are at

stake, as they are in this case.

The NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD, founded in 1937, is an

organization of 7,000 legal practitioners in 200 chapters

throughout the United States, more than a dozen of which are in New

5

York State. The Guild and its members have provided legal support

to virtually every struggle in the country for economic, social and

political justice. The Guild has a National AIDS Network which

coordinates representation of people with AIDS or related

conditions and publishes a comprehensive practice manual. It is

involved in educational efforts directed at the general public to

eliminate discrimination against those who are infected and iecure

adequate health care for those in need.

The NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND is a national

nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to the elimination of sex

discrimination. Since its inception in 1970, the NOW Legal Defense

and Education Fund has been involved in numerous federal and state

cases concerning the issues of women's health and broader and more

progressive application of public accommodations laws.

NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund is especially concerned

with the issues raised in this case since AIDS is the leading cause

of death of women between the ages of 25-34 in the New York City

metropolitan area. Women currently make up at least 10% of all the

people with AIDS and over 80% of these women are women of color.

Ensuring non-discriminatory access for these and all women to

adequate health care is part of NOW LDEF's mission.

The PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. was

established in 1972 as a national, not-for-profit organization to

protect and promote the civil rights of Puerto Ricans and other

Latinos. The Fund's advocacy and litigation efforts focus on

6

education, employment, health care issues, and housing, as well as

political access and representation.

7

INTRODUCTION

A broad coalition of state and national civil rights and civil

liberties organizations appears as amicus curiae in this case to

urge this Court to reject the lower court's conclusion that, as a

matter of law, dentists' offices may never be public accommodations

subject to the Human Rights Law and to reverse the lower court's

more specific holding that petitioner-respondent Sattler's office

is exempt from the law because he takes patients on a referral-only

basis and implicitly falls within the statutory exception created

for "distinctly private" accommodations.

These determinations by the court below are contrary to the

plain language of the Human Rights Law and its interpretation by

the New York Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court. If this

Court adopted the lower court's position, it would severely and

unjustly limit the reach of New York's anti-discrimination laws.

It would also deny all members of protected classes egual access to

dental services provided by individual dentists, even though dental

services are often inadequate and/or unavailable at public

institutions and the public relies on individual dentists to meet

its dental care needs. The City Council intended that individual

dentists provide these services without regard to real or perceived

race, creed, color, national origin, alienage, citizenship, gender,

marital status, sexual orientation or disability.

Particularly dangerous is the lower court's holding that the

professional nature of Sattler's services and his referral-only

8

policy deprives his patients of the protections against

discrimination provided by the Human Rights Law. If accepted, the

reasoning in support of this holding would permit invidious

discrimination by those whose services are most necessary. Not

just dentists, but virtually all professionals would be able to

avoid the proscriptions of the Human Rights Law with impunity. The

City Council did not intend that a vital group of service providers

be beyond the statute's reach. Professional businesses are not

exempt from the obligation to serve equally and with dignity all

members of our communities.

When state legislatures began to adopt public accommodation

laws after the civil war, they recognized that governmental

intervention to bar discrimination by privately-owned businesses

was necessary to protect the public welfare. Society as a whole is

enriched when each individual has an equal opportunity to enjoy a

full and productive life. State legislatures and city governments

around the country, including New York's, have progressively

broadened the law both with respect to the facilities covered and

the groups protected.

In response, the courts of all jurisdictions, including the

New York Court of Appeals and the U. S. Supreme Court, have

consistently interpreted the phrase "public accommodation" in a

manner which gives the fullest reach to policies underlying the

statutes. They have recognized that laws prohibiting

9

discrimination in public accommodations serve compelling state

interests of the highest order.

The lower court's restrictive, ungrounded analysis of the

Human Rights Law not only ignores the language and purpose of the

particular statute, but also flies in the face of the goals which

this nation has long expressed through anti-discrimination

legislation. It is this tradition which amici civil rights

organizations seek to protect.

10

ARGUMENT

THE NEW YORK CITY HUMAN RIGHTS LAW PROHIBITS

RESPONDENT FROM REFUSING TO TREAT A PATIENT

SOLELY BECAUSE THE PATIENT HAS AIDS

New York City Administrative Code (the "Code") bans

discrimination in public accommodations. Title 8 of the Code

("Human Rights Law") states:

It shall be an unlawful discriminatory practice for any

person, being the owner, lessee, proprietor, manager,

superintendent, agent or employee of any place of public

accommodation, resort or amusement, because of the race,

creed, color, national origin, or sex, any person,

directly or indirectly, to refuse, withhold from or deny

to such person any of the accommodations, advantages,

facilities or privileges thereof....

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(2). Section 8-108 of the Code makes

these prohibitions applicable to persons who are physically or

mentally handicapped.

Although the court below implicitly acknowledged that the

complainant before the New York City Commission on Human Rights

("Commission") , as an HIV seropositive individual, was disabled and

covered by the statute, it erroneously held that respondent Sattler

may escape liability for discriminatory conduct. In support of its

holding, the lower court found that dental offices are not public

accommodations covered by the Human Rights Law and that, even if

they were, Sattler's particular office is exempt from regulation

because he accepts patients on a referral-only basis which

presumably means it falls within the "distinctly private" exception

11

contained in the law. See N.Y.C. Admin. Code §8-102(9). This

analysis must be rejected.1

A. A DENTIST'S OFFICE IS A PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION UNDER THE

HUMAN RIGHTS LAW

Statutes prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations

were adopted because governmental bodies determined that certain

forms of discrimination are so invidious that they threaten the

general welfare of a democratic state and of its inhabitants by

undermining individual dignity and inhibiting wide participation in

political, social, economic and cultural life. Heckler v. Mathews.

465 U.S. 728, 744-745, 104 S.Ct. 1387, 1397-1398 (1984); People v.

King, 110 N.Y. 418, 426, 18 N.E. 245, 248 (1888). This is an

extension of the common law rule, most often associated with common

carriers and innkeepers, that the proprietor of a private

enterprise who provides a necessary service has a duty to

accommodate all in a fair and just manner. See Jacobson v. N.Y.

Racing Association. Inc.. 33 N.Y.2d 144, 150, 350 N.Y.S.2d 639, 642

(1973); In Re Cox. 474 P.2d 992, 996 (Ca. 1970); Tobriner & Grodin,

The Individual and the Public Service Enterprise in the New

Industrial State. 55 Cal.L.Rev. 1247, 1250 (1967). Public

accommodations statutes assure that each individual's need for

goods and services is met; they serve "compelling state interests

1 The court below also vacated the Commission's order based

on its finding that the agency's determination of actual discrimi

nation was not supported by substantial evidence. Amici take no

position on this issue.

12

Roberts v. United States Javcees. 468 U.S.of the highest order."

609, 624, 104 S .Ct. 3244, 3253 (1984).

"Public accommodations," as defined in modern statutes, refer

to those businesses or associations which, though privately

operated, serve or are open to the general population; as such,

they are to some extent public because they affect the "safety,

health. morals and welfare of the community" and are subject to the

state's interest in ensuring that each citizen has equal access to

them. Ness v. Pan American World Airways. 142 A.D.2d 233, 238, 535

N .Y .S .2d 371, 374 (2nd Dept. 1988) (emphasis added) ; see generallv

Note, Discrimination in Access to Public Places: A Survey of State

and Federal Accommodations Laws. 7 N.Y.U. Rev.L. & Soc. Change 215

(1978) .

The court below ignores this modern concept and application

when it holds that a dentist's office, or for that matter any

professional office, falls outside of the definition of a public

accommodation. Any establishment which offers goods or services of

any kind is covered by the Human Rights Law. Id. at 218. Public

accommodation is a "term of convenience, not limitation" which even

covers those establishments which have "no fixed place of

operation." U.S. Power Squadrons v. State Human Rights Appeal

Board. 59 N.Y.2d 401, 411, 452 N.E.2d 1199, 1207, 465 N.Y.S.2d 871,

875-876 (1983). For example, New York State abandoned limiting the

reach of its Human Rights Law to specific places in 1960 in favor

13

of a non-exclusive, descriptive list. See L. 1960, c. 779 (eff.

April 25, 1960) .

The definition of public accommodation in the New York City

Human Rights Law is also very broad. Mirroring the definition

under State law, it comprises both a long, non-exclusive list of

examples, such as "clinics, hospitals, dispensaries" and a

functional definition, "establishments dealing with goods or

services of any kind." N.Y.C. Admin. Code §8-102(a) (emphasis

added) ; see also Exec. Law §292 (2). By both using the more

functional phrase, "establishments dealing with...services of any

kind" and listing the specific terms "clinics, hospitals [and]

dispensaries," the City Council manifested its intent that all

places where medical and dental services are provided, including

individual dentists' offices, be subject to the ban on unlawful

discriminatory practices.

This is consistent with its purpose in enacting the statute,

and the agencies charged with implementing the Human Rights Law

have correctly so interpreted it. Courts of other jurisdictions

have reached similar conclusions in examining similar laws. Given

that individual dentists provide a large percentage of necessary

dental care services, any other conclusion would undercut the

purposes to be served by state regulation of private enterprises

which are affected with a public interest.

14

1. A dentist's office is an "establishment

dealing in... services" within the meaning of

the phrase as used in the statute.

Contrary to the lower court's reasoning (R. 17-21), dentists'

offices come within the statute's functional definition of public

accommodations, that is, "all places included in the meaning of

such terms as: ... establishments dealing with goods or services

of any kind ...." N.Y.C. Admin. Code §8-102(a). The inclusion of

a functional definition in addition to the specific list of covered

facilities offers a clear indication that the definition of place

of accommodation should be interpreted broadly. See U.S. Power

Squadrons. 59 N.Y.2d at 410, 452 N.E.2d at 1203, 465 N.Y.S.2d at

875 (interpreting identical provision of State Human Rights Law).

Consequently, the list in the statute is intended to be viewed

"inclusively and illustratively" and does not limit the statute to

those facilities specifically mentioned. Id. at 409, 452 N.E.2d at

1202-1203, 465 N.Y.S.2d at 874-875.

The breadth of the functional definition is so great that the

courts have found a wide array of enterprises not specifically

listed to be included within the phrase "establishments dealing

with goods or services of any kind." See. e .g .. Power Squadrons.

59 N . Y . 2d at 411, 452 N.E.2d at 1204, 465 N.Y.S.2d at 876 (non

profit corporation which promotes safety and skill in boating);

N.Y. Roadrunners Club v. State Division of Human Rights. 81 A.D.2d

681, 437 N.Y.S.2d 519 (1st Dept. 1981), aff'd on other grounds. 55

N.Y.2d 122, 432 N.E.2d 780, 447 N.Y.S.2d 908 (marathon race);

15

Walston & Co.. Inc, v. N.Y.C. Commission on Human Rights. 41 A.D.2d

238, 342 N .Y .S .2d 459 (1st Dept. 1973) (brokerage firm); Dimiceli

& Sons Funeral Home v. N.Y.C. Commission on Human Rights. N.Y.L.J.,

Jan. 14, 1987, p. 7, col. 3 (Sup. Ct. N.Y.Co.) (funeral home). The

court below ignores these appellate precedents when it relies on

two lower court cases (Elstein and Rochester) to assert that the

City Council intended that the coverage be limited to services

provided by wholesale and retail stores and not by other

establishments. See R. 18-20.2

The lower court further implies that the functional definition

in the Human Rights Law does not include dental offices because the

"type of care and services" provided by a dentist's office are

"dissimilar" to those establishments which are covered. See R.21.

However, both the type of care and the nature of the service are

expressly and implicitly within the intent of the law.

Medical and dental care are provided in dispensaries, clinics

and hospitals which are establishments included in the illustrative

statutory definition. By specifically listing these terms, the

City Council indicated that the confidential, personal nature of

Both in Elstein and in Rochester. the court based its

determination that the Human Rights Law only applies to retail

establishments on the absence of a comma. This reasoning, adopted

by the court below, is wrong. Statutory punctuation is subordinate

to the text and is never allowed to subvert the intention of the

lawmakers or to interfere with a reasonable statutory construction.

Traveler's Indemnity Insurance Co. v. State of New York. 57 Misc,2d

565, 293 N .Y .S .2d 181 (Ct. Cl. 1968), affirmed 33 A.D.2d 127, 305

N .Y .S .2d 689 (3rd Dept. 1969), affirmed 28 N.Y.2d 561, 168 N.E.2d

323, 319 N .Y .S .2d 609; N.Y. Statutes §§251, 253.

16

the service in a dentist-patient relationship is not a basis for

exclusion from the reach of the anti-discrimination laws. Whether

a dentist is on staff at a large dental care establishment or

practices in a small office does not affect the degree of trust and

reliance that a patient has in the dentist's judgment or the degree

to which the services provided are professional, personal and

confidential. See Matter of a Grand Jury Investigation of Onondaga

County. 59 N.Y.2d 130, 134, 450 N.E.2d 678, 680, 463 N.Y.S.2d 758,

759 (1983) (hospital can assert physician-patient privilege for

protection of patient); CPLR §4504(a). Health care providers who

offer medical and dental services in these settings are no less

professional than doctors and dentists who work out of individual

practices. Barber shops and beauty parlors which, like dentists'

offices, provide personal services involving physical contact on an

appointment basis are specifically listed as other examples of

covered accommodations.

In any case, as noted above, the examples listed are

illustrative, not exclusive, and, even though not specifically

listed, the courts have held other establishments which provide

personal and/or confidential services to be covered. For example,

in Dimiceli. the court refused to exclude the personal services

provided by a funeral parlor; in Walston. this Court held that the

confidential services of a commodities broker fall within the scope

of the statute. Indeed, all providers of professional services are

covered under the broad functional definition, just as certain

17

providers of professional services are listed among the statute's

specific examples.

Even if dental services were dissimilar to those provided at

the places listed in the law, the court below erred by relying on

a distinction concerning type of care and services as dispositive

in this case. For the purposes of the Human Rights Law, there is

no relevant difference and, therefore, no rational reason to

distinguish professional services from businesses which provide

other types of services. Even a single practitioner can form a

professional business corporation and receive the same tax benefits

and limitations on individual liability for ordinary business debts

as do other corporations. We're Associates Co. v. Cohen. Stracher

& Bloom. P. C. . 65 N.Y.2d 148, 153 , 490 N.Y.S.2d 743 , 746-747

(1985); see also Bus.Corp.Law §1503. By specifically extending to

professionals an entitlement to these business benefits, the

legislature recognized that providing professional services is

fundamentally a business enterprise.

The City Council made no exception for professional offices in

its definition of public accommodation as it did for libraries and

educational institutions. The special regulation of professionals

under the State Education Law does not pre-empt the authority of

the Commission to act on complaints of discrimination. Hurwitz v.

N.Y.C. Commission on Human Rights. ___ A.D.2d ___, ___, 553

N.Y.S.2d 323, 324 (1st Dept. 1990). Accordingly, for-profit

18

professional establishments, like other businesses, must also be

subject to the obligations of the Human Rights Law.

2. A dentist's office is a "clinic" within the meaning of

the term as used in the statute.

While the court below quoted the full definition of a "public

accommodation" contained in the law (R. 11-13), it failed to

examine whether the accepted definition of the statutory term

"clinic" includes a dentist's office. Had it done so, the court

could only have concluded that the City Council intended that a

dentist's office be subject to the law's reach.

Although contained in the list of examples of public

accommodations, a clinic is not defined in the law itself.

Steadman's Medical Dictionary defines "clinic" as "an institution,

building or part of a building where ambulatory patients are cared

for." The term encompasses "the office of a group practice or even

the office of a single practitioner." People v. Dobbs Ferry

Medical Pavilion. Inc. 40 A.D.2d 324, 327, 340 N.Y.S.2d 108, 112

(2nd Dept. 1973). In affirming Dobbs Ferry, the Court of Appeals

noted that the term "clinic" is "inclusive of many kinds of

individual, partnership and group medical practice." 33 N.Y.2d

584, 301 N.E.2d 435, 347 N.Y.S.2d 452 (1973) (emphasis added).

Thus, the standard definition of the term "clinic", accepted by the

Court of Appeals, explicitly encompasses respondent's office.

For compelling reasons, this definition should similarly

attach to the term as used in the Human Rights Law. When

19

interpreting a statute, the court should attempt to effectuate the

intent of the legislature, which should be inferred, if possible,

from the words chosen. Patrolmen's Benevolent Association v. City

of New York. 41 N.Y.2d 205, 208, 359 N.E.2d 1338, 1340, 391

N.Y.S.2d 544, 546 (1976). Undefined statutory terms should be

construed according to their ordinary and accepted meaning. People

v. Eulo. 63 N .Y .2d 341, 354, 472 N.E.2d 286, 294, 482 N.Y.S.2d 436,

444 (1984). If a word has more than one meaning, the Court of

Appeals has recently instructed that Courts should consider the

consequences of the different interpretations and should choose the

definition which advances the general purpose of the statute and

prevents hardship and injustice; it is not the courts' role to

"delve into the minds of the legislators" for a meaning of a

particular term. Braschi v. Stahl Associates Co.. 74 N.Y.2d 201,

208, 543 N .E .2d 49, 52, 544 N.Y.S.2d 784, 787 (1989).

These rules of construction have particular force in

interpreting remedial legislation, such as the Human Rights Law,

where the statute's terms should be interpreted broadly to

accomplish its purpose. U.S. Power Squadrons. 59 N.Y.2d at 401,

411, 452 N.E.2d at 1207, 465 N.Y.S.2d at 876 (interpreting State

Human Rights Law); see also New York Life Insurance Co. v. State

Tax Commissioner. 80 A.D.2d 675, 677, 436 N.Y.S.2d 380,383 (3rd

Dept. 1981) affirmed. 55 N.Y.2d 758, 431 N.E.2d 970, 447 N.Y.S.2d

245 (remedial statute to be construed in manner which will

"suppress the evil and advance the remedy"). The Human Rights Law

20

itself mandates that the statute be liberally construed. N.Y.C.

Admin. Code §8-112.

Defining clinic to exclude the offices of individual dentists

would thwart the purpose and remedial nature of the Human Rights

Law, invoke hardship on vulnerable protected classes, and permit

unjust discrimination by a large group of service providers to go

unchecked. Even if the term "clinic” may have other meanings,

looking to the more restrictive definition would be inconsistent

with the recent instructions from the Court of Appeals. Therefore,

a dentist's office must be included within the types of

accommodations listed and respondent's business is directly covered

by the statute.

3. A statutory interpretation which holds that a

dentist's office is a public accommodation

furthers the purpose underlying the Human

Rights Law.

In addition to the reasons based on rules of statutory

construction already discussed, the professional nature of the

dental services cannot be a basis for evading the Human Rights Law

for reasons of public policy. The purpose of human rights laws is

the elimination of discrimination in the provision of basic

opportunities. See Koerner v. State. 62 N.Y.2d 442, 448, 467

N .E .2d 232, 234, 478 N.Y.S.2d 584, 586-587 (1984) (purpose of State

Human Rights Law). This is consistent with the explicit policy of

New York State that every individual in the state be afforded an

21

"equal opportunity to enjoy a full and productive life," and that

such equal opportunity should not be inhibited by inadequate health

care. Exec. Law §290(3). Failing to assure equal access to

services offered by independent professionals would permit

invidious discrimination in the provision of this basic necessity.

This fact alone further supports the coverage of dental offices

under the Human Rights Law.

The rationale that dentists' offices must be excluded because

dentists are professionals is more onerous because of its

ramifications. Allowing dentists to discriminate on grounds

forbidden by the statute solely because their services are

professional, because the dentist-patient relationship is based on

reliance, trust and confidence, or because dental services are

unique would in effect permit members of all 21 professions named

in Title VIII of the Education Law to discriminate without adverse

consequences under the Human Rights Law. Thus, not only dentists,

but also doctors, nurses, engineers, architects, accountants, court

reporters, psychologists and social workers would be able to refuse

their services to any person simply because that person is, for

instance, black, Jewish, Hispanic, female, deaf or gay. The City

Council, which recognized that "there is no greater danger" to the

City's general welfare than discrimination based on specified

arbitrary characteristics (N.Y.C. Admin. Code §8-101), could not

have intended to imply an exclusion which would so undermine its

policy to remedy discrimination.

22

This does not mean that every professional must accept any

person who presents himself or herself for services. However, it

does mean that dentists may not refuse care to a potential patient

simply because of that person's membership in a protected class.

To hold otherwise, as the court below did, would deny equal access

to adequate dental care and subvert the Human Rights Law.

4. Courts and agencies, both in and outside of

New York, have held that professional offices

are public accommodations.

The agencies charged with enforcing the human rights laws in

New York have agreed with the view that the Human Rights Law

applies to professional offices. The Commission's determination

with regard to respondent's office accords with its decision in

similiar cases. See Campanella v. Hurwitz. No. GA-00021030487-DN

(Feb. 22, 1988) (private dentist's office covered by Human Rights

Law) ;3 Rolanti v. Dental Associates of New York. No. GA-

00052070687-DN (Oct. 20, 1988) (group dental practice covered by

Human Rights Law) . The New York State Division on Human Rights has

determined that doctors' offices are covered under its public

accommodations statute, as the Commission did in this case with

regard to dentists' offices. See Derby v. Elstein. No. 9K-P-D-87-

117654 (March 10, 1988) (preliminary finding that professional

offices are encompassed by State Human Rights Law which covers

The Appellate Division, First Department, declined to

prevent the Commission from exercising jurisdiction over the

dentist in Campanella. Hurwitz v. N.Y.C. Commission on Human

Rights, ___ A .D .2d ___, 553 N.Y.S.2d 323 (1990).

23

"establishments dealing with goods or services" and that the

Division has jurisdiction in the matter).4

Every other jurisdiction which in the last 35 years has ruled

directly on the regulation of health care offices has held private

medical offices are covered under laws prohibiting discrimination

in public accommodations. In the oldest such case, Washington v.

Blampin. 226 Cal. App.2d 604, 38 Cal. Rptr. 235 (2d Dist. 1964), an

action was brought against a private physician who refused to treat

a child because she was black. The lower court dismissed on the

grounds that a professional office was not covered by the

California public accommodations law. But the District Court of

Appeal reversed, holding that a physician's office was embraced by

the statutory phrase "business establishment of every kind

whatsoever." See also Leach v. Drummond Medical Group. 144 Cal.

App.3rd 362, 192 Cal. Rptr. 650 (5th Dist. 1983) (private

The Supreme Court, Onondaga County, had overturned the

Division's ruling. Elstein v. State Division of Human Rights.

N.Y.L.J., Aug. 18, 1988, p. 2, col. 3. The Appellate Division,

Fourth Department, reversed and dismissed the petition holding that

the agency should be permitted to make a final determination in the

matter which would then be subject to judicial review. _A.D.2d

___, 555 N.Y.S.2d 516 (1990). In any case, the lower court's

reasoning is incorrect and should not be followed. The lower court

in Elstein based its determination on three grounds: 1) the office

of an individual practitioner is not specifically listed in the

statute; 2) the office is not an establishment dealing with goods

or services of any kind because the statute only covers retail

establishments; and 3) the confidential nature of the doctor-

patient relationship takes it outside the realm of the Human Rights

Law. As discussed above, all three grounds are wrong.

24

professional medical association constitutes business establishment

subject to public accommodations law) .

Similarly, in Lyon v. Grether. 239 S.E.2d 103 (Va. 1977), a

blind woman sued a physician for damages after he refused to treat

her unless she removed her seeing-eye dog from the waiting room.

The lower court dismissed the complaint, finding that a private

physician was not covered by the state's "White Cane Act" which

entitles blind people to equal access in places of public

accommodation. The Virginia Supreme Court reversed and held that

"[the physician's] office was a place to which certain members of

the general public were invited by prior appointment to receive

CGrtain treatment at certain scheduled hours" and, therefore, was

covered by the Act. Id. at 106. The Illinois Human Rights

Commission concurs. See G.S. v. Baksh. ALS No. 2810 (Sept. 26,

1988) (dentist's office covered by Illinois Human Rights Act).

With the exception of Elstein (discussed at footnote 3 above), the

court below cites no cases which directly support its holding that

dentists' offices are not covered by the Human Rights Law.

B. RESPONDENT'S DENTAL OFFICE, WHICH ROUTINELY ACCEPTS AS

NEW PATIENTS MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL PUBLIC ON AN

INDIVIDUALIZED, FEE-PAYING BASIS, IS NOT EXEMPT AS

DISTINCTLY PRIVATE.

The City Human Rights Law exempts from coverage an

"institution, club or place of accommodation which proves that it

is in its nature distinctly private." N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-

102(9). The State Human Rights Law's definition of public

25

accommodation contains a similar exemption. Executive Law §

292(a). In creating an exemption for those accommodations which

are in their nature distinctly private, the City Council and the

State Legislature sought to distinguish between those entities in

which the public has an interest in promoting the safety, health,

morals and welfare of the community and those entities which are so

characterized by selectivity and exclusivity that they are outside

the reach of the public's interest. The party seeking the

exemption bears the burden of showing that it is not covered by the

anti-discrimination statutes; exemptions are not granted lightly.

Power Squadrons. 59 N.Y.2d at 412, 452 N.E.2d at 1204, 465 N.Y.S.2d

at 876.

The court below failed to grasp the statutory distinction

between public and distinctly private accommodations. As a result,

it held, as one basis for granting the petition, that the

Administrative Law Judge, whose opinion was modified and adopted by

the Commission, inappropriately applied a distinctly private

analysis to this case. To achieve this result, the court engaged in

a tortured reading of Section 8-102(9) of the Code which limited

the application of the distinctly private exemption, contrary to

the Code's plain meaning. The lower court reasoned that the

exemption for distinctly private accommodations did not arise in

this instance because it concluded that the term "distinctly

private" modifies only "institutions, clubs and places of

accommodation" and not "retail stores and establishments dealing

26

with goods or services of any kind." R. at 16-17. Such a

construction is illogical since retail stores and establishments

dealing with goods or services of any kind, as well as many other

entities, are subsumed within the Code's definition of "place of

public accommodation, resort or amusement." If, as the court below

says, "distinctly private" modifies the broad "place of

accommodation," it must by necessity define those entities included

as illustrative examples of places of public accommodation. In

fact, the sentence containing the distinctly private exemption

begins with a reference to the definitional phrase: "Such term

[i.e. place of public accommodation, resort or amusement] shall not

include ... any institution, club or place of accommodation which

proves that it is in its nature distinctly private."

Since respondent operates an establishment which is covered by

the law (see Point I.A, above), the Commission correctly considered

any jurisdictional questions with respect to respondent's dental

practice by analyzing whether it is distinctly private in nature.

Contrary to the lower court's determination, the Commission was

also correct in finding that respondent had not met his burden of

demonstrating that his practice falls within the exemption for

distinctly private accommodations. Amici urge that this Court also

reverse the court below on this point.

The term "distinctly private" as used in an identical

provision of the State Human Rights Law was first given

authoritative interpretation in Matter of U.S. Power Squadrons v.

27

State Human Rights Appeal Board. 59 N.Y.2d 401, 452 N.E.2d 1199,

465 N.Y.S.2d 871 (1983). The Court of Appeals held that the key to

the inquiry is "selectivity" and "exclusiveness." Id. at 412, 452

N.E.2d at 1204, 465 N.Y.S.2d at 876. The touchstone is whether the

entity is a membership organization established and run by and for

the benefit of the members. It is not enough that an entity be

able to show that some or all aspects of its business are private;

rather the court must find that the entity has met a more exacting

burden of demonstrating that its business is distinctly private in

nature. Id. ; N.Y.S. Club Association v. City of New York. 69

N .Y .2d 211, 220, 505 N.E.2d 915, 919, 513 N.Y.S.2d 349, 353 (1987),

aff'd. 487 U.S. 1, 108 S.Ct. 2225 (1988).

The New York courts have never held a business to be

distinctly private under either the State or City Human Rights

laws; the only institution exempted under New York law has been a

private club. See Kiwanis Club of Great Neck, Inc, v. Board of

Trustees of Kiwanas International. 52 A.D.2d 906, 383 N.U.S.2d 383

(2nd Dept. 1976), aff'd. 41 N.Y.2d 1034, 363 N.E.2d 1378, 395

N.Y.S.2d 633, cert, denied. 434 U.S. 859, 98 S.Ct. 183.

So strong is this policy against discrimination and so narrow

is the "distinctly private" exemption, that an otherwise-exempt

establishment, when it opens itself to the public for a particular

event, may not discriminate in violation of the statute during that

period. See Batavia Lodge No. 196, Loval Order of Moose v. N.Y.S.

Division of Human Rights. 43 A.D.2d 807, 350 N.Y.S.2d 273 (4th

28

>

Dept. 1973), rev'd on other grounds. 35 N.Y.2d 143, 316 N.E.2d 318,

359 N.Y.S.2d 25 (private club could not discriminate in providing

services at separate, members-only bar during period when open to

general public for fashion show.) Similarly, an apparently private

club is not distinctly private if it charges a fee and is operated

for a profit. See Daniel v. Paul. 395 U.S. 28, 301, 89 S.Ct. 1697,

1699 (1968) (sports club that charge fee and operated for profit

not exempt from Title II of the Civil Rights Act as a private club

or establishment.)

In Power Squadrons, the Court of Appeals set out five criteria

for determining whether a provider of accommodations has shown that

it is distinctly private. Specifically, the Court may consider

whether the establishment:

(1) has permanent machinery established to

carefully screen applicants on any basis at

all, i.e., membership is determined by

subjective, not objective factors; (2) limits

the use of its facilities and the services of

the organization to members and bona fide

guests of members; (3) is controlled by the

membership; (4) is nonprofit and operated for

the benefit and pleasure of the members; and

(5) directs its publicity exclusively and only

to members for their information and guidance.

59 N .Y .2d at 412-413, 452 N.E.2d at 1204, 465 N.Y.S.2d at 876.

A dentist's office, such as respondent's, is not distinctly

private under this standard. Generally, a dentist defines the

patients to whom he or she will provide services based upon such

factors as the patient's treatment needs, the dentist's

availability and the patient's ability to pay a fee for the

29

dentist's services. Most dentists constantly take on new patients.

Office policies are determined not by the patients, but by the

dentist, with an eye towards the profit-making function of a

business enterprise. The dentist may solicit the public through

referrals from other health care providers or from pleased

patients, or by other means.

Moreover, subsequent to Power Squadrons the New York City

Council amended the Human Rights Law to further limit the term

"distinctly private." In 1984, the City Council enacted Local Law

63, which set forth that an institution, club or place of

accommodation

shall not be considered in its nature

distinctly private if it has more than four

hundred members, provides regular meal

service, and regularly receives payment for

dues, fees, use of space, facilities,

services, meals or beverages directly or

indirectly from or on behalf of nonmembers for

the furtherance of trade or business.

In upholding Local Law 63 as a constitutional exercise of the

City Council's power to regulate discriminatory conduct where there

is sufficient public interest, the Supreme Court balanced the

rights of club members to associate against the City's interest in

proscribing discrimination in establishments which are commercial

in nature. It stated that:

it is conceivable, of course, that an

association might be able to show that it is

organized for specific expressive purposes and

that it will not be able to advocate its

desired viewpoints nearly as effectively if it

cannot confine its membership to those who

30

share the same sex, for example, or the same

religion.

N.Y.S. Club Assn.. 487 U.S. at 13, 108 S.Ct. at 2234.

The language chosen by the City Council as well as the

reasoning of the Supreme Court shows that the purpose of this

amendment to the Code was to delineate those accommodations which

were not distinctly private in nature, "because of the kind of role

that strangers play in their ordinary existence ... " N.Y.S. Club

Assn. . 487 U.S. at 12, 108 S.Ct. at 2233.5 The distinctly private

exemption contained in the Human Rights Law does not encompass

dental practices in general, and respondent's practice

specifically, since these practices are composed of "strangers" who

can pay the dental fee, appear on time for appointments, and desire

good dental care. Rather, distinctly private accommodations are

those that limit access to those who share a common bond— be it

their religion, their country of origin, or particular political

beliefs. Business establishments, like that of a dentist office,

were not the types of accommodations which the City Council sought

to exclude from the scope of the law.

Despite the purpose behind the distinctly private exemption,

the court below concluded that the respondent's adherence to a

The Supreme Court observed in N.Y.S. Club Assn, that

neither the three factors set out in Local Law 63, nor the five

prong test enunciated in Power Squadrons were the exclusive ways in

which an accommodation could be found to have lost the essential

characteristics of selectivity and exclusivity which would render

it distinctly private. N.Y.S. Club Assn. . 487 U.S. at 15, 108

S.Ct. at 2235, n. 6.

31

referral-only format was sufficient to remove his practice from the

jurisdiction of the Human Rights Commission. However, significant

precedent, as well as the uncontroverted facts adjudged at the

hearing, do not support Justice Rosato's conclusion that where a

proprietor or establishment conducts a business on a referral only

basis, it has cloaked itself with "the essential characteristic of

privateness — i.e., selectivity," N.Y.S. Club Assn.. 69 N.Y.2d at

221, 505 N .E .2d at 920, 513 N.Y.S.2d at 354 (1987).

The testimony at the hearing revealed that respondent's

referral mechanism was a very effective means of acquiring

patients, not of screening them out. In fact, as a result of

respondent's reliance upon referrals his practice increased by

hundreds of patients each year. His testimony at the hearing with

respect to his use of referrals revealed the following: When he

began his dental practice in 1985 he solicited patients by telling

his friends, colleagues and relatives the had opened an office. At

the end of his first year of practice, he had only ten patients

(Tr. at 346-350, 352). However, using this "word of mouth" method

of gaining business, he had hundreds of patients, possibly one

thousand, by his second year of practice and in 1986 received

between two and four new patients a week (Tr. at 356). Respondent

further testified that in 1987 he had several hundred more patients

than he had had the year before and that he received three to five

new patients every week (Tr. at 363-364).

32

Respondent's testimony only revealed what is in many ways

common knowledge — that dental and medical professionals let their

good work speak for itself in the expectation that satisfied

patients will refer their friends to the practitioner. These facts

do not support the conclusion of the court below that the use of

referrals served to confine his practice to an exclusive set of

patients. Rather, reliance upon referrals made good business

sense. Simply because it is the custom in many of the professions

to obtain new business through referrals is not enough, as a matter

of law, to hold that these businesses have gained an essential

characteristic of selectivity.

Further, the Court below erred in adopting an uncritical

deference to the use of referrals without inquiring whether the

respondent's reliance upon referrals amounted to an exacting and

subjective standard imbued with selectivity that removed his

practice from the public interest. Respondent's own testimony

showed that he had no "plan or purpose" for excluding new patients,

nor did he place any limit on the number of new patients he would

accept. When asked to describe his use of referrals, respondent

testified that a referral meant that "someone who knew me told them

about me" (Tr. at 360) and that the majority of referrals were from

other patients (Tr. at 394). Other than the incident contained in

Mr. McCoury's complaint, respondent testified that the only person

to whom he refused treatment was a woman who had such bad arthritis

33

that he judged treatment would be potentially injurious to her (Tr.

at 363).

Most telling, however, was respondent's testimony with respect

to the purpose behind his reliance upon referrals. Besides acting

as an effective method of obtaining new patients, the respondent

viewed referrals as a means of gaining good patients, that is,

patients who "follow my rules" (Tr. at 360). The only criteria

that respondent uses in screening new patients is that they be able

to pay his fee, that they appear for appointments on time, and that

they desire good dental care (Tr. at 360, 410-411). In fact,

respondent has never called a referral source to verify if a new

patient was actually referred by that person (Tr. at 395).

Instead, he routinely sends out thank-you cards to those who refer

patients to him, presumably to encourage further referrals (Tr. at

427) .

On these facts, the jurisdictional significance of referrals

is identical to the sponsorship and membership application used by

a private beach club that sought to exclude black members in Castle

Hill Beach Club v. Arburv. 2 N.Y.2d 598, 142 N.E.2d 186, 162

N.Y.S.2d 1 (1957). There the Court of Appeals found that the

membership criteria utilized by the club served only to screen out

applicants who might be disorderly:

As a matter of fact and procedure, however,

applicants were taken in on their face value,

without interview, investigation or

sponsorship, upon the recommendation of either

34

two members or the members' governing

committee ...

2 N . Y . 2d at 5-6, 142 N.E.2d at 189, 162 N.Y.S.2d at 5 (emphasis

supplied).

Here, as in Castle Hill Beach Club, the respondent's criteria

for screening new patients does not demonstrate exclusivity or

selectivity. That he limits his practice to patients who can pay

a fee for his services, show up on time for appointments and expect

good dental care does not demonstrate the use of subjective

criteria designed to assure exclusivity as set forth by the Court

of Appeals in Power Squadrons. They are the type of requirements

any person in business would expect of his or her customers or

clients. They further commercial purposes, not distinctly private

ones. For example, these three "rules" would apply in equal force

to many of the establishments which the City Council explicitly

listed in Section 8-109(2) of the Code as illustrations of places

of public accommodations, e . q . . restaurants, beauty parlors,

medical and dental clinics and other establishments, which often

provide services on a reservation-only or appointment-only basis.

This is not to say that there may not be some circumstances

under which a dental practice might fall outside the definition of

public accommodation. Where, for instance, an employer or union

employed a dentist for the benefit of its employees or union

members, the dentist providing those services could limit his or

her practice only to employees or union members. See. e.g.. Ness

35

CONCLUSION

Individual providers of dental services are subject to the

anti-discriminatory provisions of the Human Rights Law as a matter

of law. Failure to include these dental offices as public

accommodations would permit individual dentists to discriminate

with impunity and thereby deprive any member of a protected class

an equal opportunity to obtain adequate dental care; or perhaps,

given the scarcity of publicly-provided dental care, deprive them

of an opportunity to obtain dental care at all. Following the

lower court's reasoning would also exclude from the statute's

regulatory reach all professionals, many of whom provide some of

the most basic human services. Therefore, amici civil rights

organizations request that this Court reverse the judgment of the

court below and hold that the office of a single dentist is

included in the definition of public accommodations under the Human

Rights Law and that respondent's office is not distinctly private.

Dated: New York, New York

August 8, 1990

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

401 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-2114

Of Counsel:

Robert M. Petrucci, Esq.

Ellen Gesmer, Esq.

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD

55 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10013

(212) 966-5000

Of Counsel:

Katherine Franke, Esq.

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION AIDS PROJECT

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 944-9800

Of Counsel:

Nan D. Hunter, Esq.

Judith Levin, Esq.

William B. Rubenstein, Esq.

37

401 BROADWAY

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10013-3005

(212) 219-2114 / FAX (212) 966-2162

Ellen Gesmer

Paul M. Gulielmetti

Maura N. Gregory

Robert M. Petrucci

August 13, 1990

Steve Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Re: Sattler v. City of New York

Commission on Human Rights

Dear Mr. Ralston:

Enclosed please find a copy of the motion papers which

were filed on your behalf, seeking leave to appear as an

amicus curiae in this case. This packet does not include

Exhibit B, Justice Rosato's decision at the Supreme Court

level (which I sent to you in my letter dated July 24) , or

Exhibit C, the Commission's Notice of Appeal.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to

contact me. I will let you know when we receive a

determination from the Appellate Division.

Very truly yours,

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

"Robert M. Petrucci

RMP:pnr

Enc.

cc: Mitchell Karp, Esq.

N.Y.C. Commission on

Human Rights

C

h

e

ck

A

p

p

lic

a

b

le

»

WES^Ctf^S^ER COUNTY a *

Index No. 118-90 Year 19

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION - SECOND DEPARTMENT

ROBERT SATTLER,

Petitioner-Respondent,

-against-

THE CITY OF NEW YORK COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS,

Respondent-Appellant,

for an Order pursuant to Section 8-110, NYC Administrative Code,

vacating the Decision and Order of the Respondent-Commission dated

November 30, 1989, in the matter entitled McCoury v. Sattler,

Complaint No. GA-00097031688-DN.

NOTICE OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAR

AS AMICUS CURIAE

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

Attorneys for Mo va n t s

401 BROADWAY

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013

(212)219-2114

To: Hashmall, Sheer, Bank & Geist Victor A. Kovner

Corporation Counsel

Attomey(s) for Re sponden t-Appe 1 lan t

Service of a copy of the within is hereby admitted.

Dated:

Attorney (s) for

PLEASE TAKE NOTICE

□ that the within is a (certified) true copy of a

j n o t ic e o f entered in the office of the clerk of the within named Court on 19

ENTRY

□

NOTICE OF

SETTLEMENT

that an Order of which the within is a true copy will be presented for settlement to the Hon.

one of the judges of the within named Court,

at

on 19 , at M.

Dated:

GULIELMETTI & GESMER, P.C.

Attorneys for

To:

401 BROADWAY

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013

Attomey(s) for N 91 2 CL

Copyright 1973 © by ALL-STATE LEGAL SUPPLY CO

* i One Commerce Drive,iCranford, «N.J. 07016 < t

4 - *■ 4 4 *

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF ss:

I, the undersigned, am an attorney admitted to practice in the courts of New York State, and

certify that the annexed

Attorney1* has been compared by me with the original and found to be a true and complete copy thereof.

Certification

say that: I am the attorney of record, or of counsel with the attorney(s) of record, for

. I have read the annexed

know the contents thereof and the same are true to my knowledge, except those matters therein which are stated to be alleged on

information and belief, and as to those matters I believe them to be true. My belief, as to those matters therein not stated upon

knowledge, is based upon the following:

1 □

a Attorney's

< Verification

* by

-c Affirmation

The reason I make this affirmation instead of

I affirm that the foregoing statements are true under penalties of perjury.

Dated:

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF

(P rin t signer’s nam e below signatu re)

□

being sworn says: I am

in the action herein: I have read the annexed

j individual know the contents thereof and the same are true to my knowledge, except those matters therein which are stated to be alleged on

| *" ,c°"on information and belief, and as to those matters I believe them to be true.

| □ the of

1 fT T ° a corPoration, one of the parties to the action; I have read the annexed

know the contents thereof and the same are true to my knowledge, except those matters therein which are stated to be alleged on

information and belief, and as to those matters I believe them to be true.

My belief, as to those matters therein not stated upon knowledge, is based upon the following:

Sworn to before me on ,19

(P rin t s igner’s nam e below signatu re)

STATE OF NEW YORK, COUNTY OF

being sworn says: I am not a party to the action, am over 18 years of

age and reside at

On ,1 9 , I served a true copy of the annexed

in the following manner:

J □ by mailing the same in a sealed envelope, with postage prepaid thereon, in a post-office or official depository of the U.S. Postal Service

s Se,,,c' within the State of New York, addressed to the last known address of the addressee(s) as indicated below:

S By Mail ' '

"a

! □ by delivering the same personally to the persons and at the addresses indicated below:

J? Personal

Service

Sworn to before me on ,19

(Print signer’s name below signature)