Court Calendar

Public Court Documents

May 27, 1977

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Court Calendar, 1977. 7c6404ae-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d3f4ee40-c5d0-4a62-ada8-954eb3bcf071/court-calendar. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

a ———

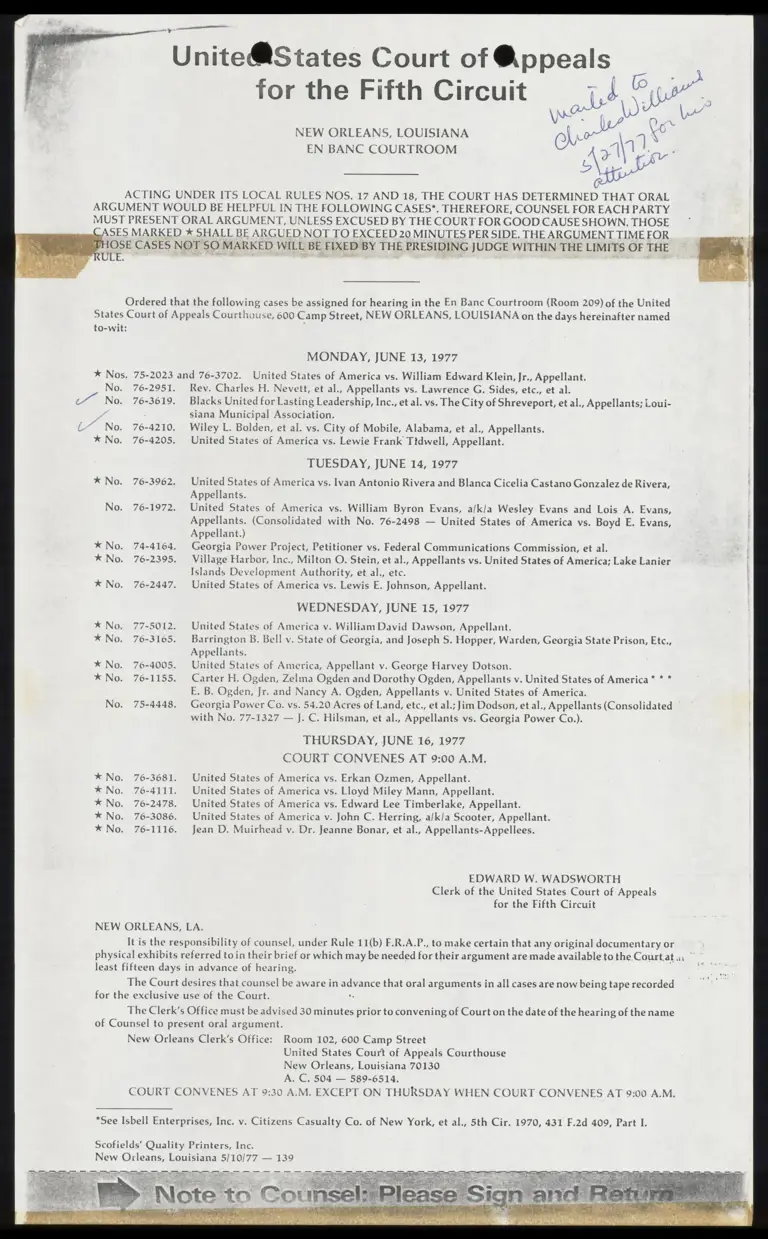

Unite@States Court of @ppeals

for the Fifth Circuit Ld Cie

dan

WW ~ fi 8) <\

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA et 1 X*

EN BANC COURTROOM >I hs

— 447

[hi

ACTING UNDER ITS LOCAL RULES NOS. 17 AND 18, THE COURT HAS DETERMINED THAT ORAL

ARGUMENT WOULD BE HELPFUL IN THE FOLLOWING CASES*. THEREFORE, COUNSEL FOR EACH PARTY

MUST PRESENT ORAL ARGUMENT, UNLESS EXCUSED BY THE COURT FOR GOOD CAUSE SHOWN. THOSE

ASES MARKED * SHALL BE ARGUED NOT TO EXCEED 20 MINUTES PER SIDE. THE ARGUMENT TIME FOR

OSE CASES NOT SO MARKED WILL BE FIXED BY THE PRESIDING JUDGE WITHIN THE LIMITS OF THE

Ordered that the following cases be assigned for hearing in the En Banc Courtroom (Room 209) of the United

States Court of Appeals Courthouse, 600 Camp Street, NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA on the days hereinafter named

to-wit: :

MONDAY, JUNE 13, 1977

* Nos. 75-2023 and 76-3702. United States of America vs. William Edward Klein, Jr., Appellant.

No. 76-2951. Rev. Charles H. Nevett, et al., Appellants vs. Lawrence G. Sides, etc., et al.

¢”~ No. 76-3619. Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc., et al. vs. The City of Shreveport, et al., Appellants; Loui-

siana Municipal Association.

(~~ No. 76-4210. Wiley L. Bolden, et al. vs. City of Mobile, Alabama, et al., Appellants.

* No. 76-4205. United States of America vs. Lewie Frank Tidwell, Appellant.

TUESDAY, JUNE 14, 1977

* No. 76-3962. United States of America vs. Ivan Antonio Rivera and Blanca Cicelia Castano Gonzalez de Rivera,

Appellants.

No. 76-1972. United States of America vs. William Byron Evans, a/k/a Wesley Evans and Lois A. Evans,

Appellants. (Consolidated with No. 76-2498 — United States of America vs. Boyd E. Evans,

Appellant.)

* No. 74-4164. Georgia Power Project, Petitioner vs. Federal Communications Commission, et al.

* No. 76-2395. Village Harbor, Inc., Milton O. Stein, et al., Appellants vs. United States of America; Lake Lanier

Islands Development Authority, et al., etc.

* No. 76-2447. United States of America vs. Lewis E. Johnson, Appellant.

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15, 1977

* No. 77-5012. United States of America v. William David Dawson, Appellant.

* No. 76-3165. Barrington B. Bell v. State of Georgia, and Joseph S. Hopper, Warden, Georgia State Prison, Etc.,

Appellants.

* No. 76-4005. United States of America, Appellant v. George Harvey Dotson.

* No. 76-1155. Carter H. Ogden, Zelma Ogden and Dorothy Ogden, Appellants v. United States of America® * *

E. B. Ogden, Jr. and Nancy A. Ogden, Appellants v. United States of America.

No. 75-4448. Georgia Power Co. vs. 54.20 Acres of Land, etc., etal.; Jim Dodson, et al., Appellants (Consolidated

with No. 77-1327 — J. C. Hilsman, et al., Appellants vs. Georgia Power Co.).

THURSDAY, JUNE 16, 1977

COURT CONVENES AT 9:00 A.M.

* No. 76-3681. United States of America vs. Erkan Ozmen, Appellant.

* No. 76-4111. United States of America vs. Lloyd Miley Mann, Appellant.

* No. 76-2478. United States of America vs. Edward Lee Timberlake, Appellant.

* No. 76-3086. United States of America v. John C. Herring, a/k/a Scooter, Appellant.

* No. 76-1116. Jean D. Muirhead v. Dr. Jeanne Bonar, et al., Appellants-Appellees.

EDWARD W. WADSWORTH

Clerk of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

NEW ORLEANS, LA.

It is the responsibility of counsel, under Rule 11(b) F.R.A.P., to make certain that any original documentary or

physical exhibits referred to in their brief or which may be needed for their argument are made available to the Courtat..

least fifteen days in advance of hearing.

The Court desires that counsel be aware in advance that oral arguments in all cases are now being tape recorded

for the exclusive use of the Court.

The Clerk’s Office must be advised 30 minutes prior to convening of Court on the date of the hearing of the name

of Counsel to present oral argument.

New Orleans Clerk's Office: Room 102, 600 Camp Street

United States Court of Appeals Courthouse

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

A. C. 504 — 589-6514.

COURT CONVENES AT 9:30 A.M. EXCEPT ON THURSDAY WHEN COURT CONVENES AT 9:00 A.M.

*See Isbell Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizens Casualty Co. of New York, et al., 5th Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 409, Part I.

Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc.

New Orleans, Louisiana 5/10/77 — 139

_.

Ordered that the following cases be assigned for hearing in the En Banc Courtroom (Room 209) of the United

States Court of Appeals Courthouse, 600 Camp Street, NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA on the days hereinafter named

to-wit:

MONDAY, JUNE 13, 1977

* Nos. 75-2023 and 76-3702. United States of America vs. William Edward Klein, Jr., Appellant.

No. 76-2951. Rev. Charles H. Nevett, et al., Appellants vs. Lawrence G. Sides, etc., et al.

No. 76-3619. Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc., et al. vs. The City of Shreveport, et al., Appellants; Loui-

siana Municipal Association.

No. 76-4210. Wiley L. Bolden, et al. vs. City of Mobile, Alabama, et al., Appellants.

* No. 76-4205. United States of America vs. Lewie Frank Tidwell, Appellant.

TUESDAY, JUNE 14, 1977

* No. 76-3962. United States of America vs. Ivan Antonio Rivera and Blanca Cicelia Castano Gonzalez de Rivera,

Appellants.

No. 76-1972. United States of America vs. William Byron Evans, a/k/a Wesley Evans and Lois A. Evans,

Appellants. (Consolidated with No. 76-2498 — United States of America vs. Boyd E. Evans,

Appellant.)

* No. 74-4164. Georgia Power Project, Petitioner vs. Federal Communications Commission, et al.

* No. 76-2395. Village Harbor, Inc., Milton O. Stein, et al., Appellants vs. United States of America; Lake Lanier

Islands Development Authority, et al., etc.

* No. 76-2447. United States of America vs. Lewis E. Johnson, Appellant.

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15, 1977

* No. 77-5012. United States of America v. William David Dawson, Appellant.

* No. 76-3165. Barrington B. Bell v. State of Georgia, and Joseph S. Hopper, Warden, Georgia State Prison, Etc.,

Appellants.

* No. 76-4005. United States of America, Appellant v. George Harvey Dotson.

* No. 76-1155. Carter H. Ogden, Zelma Ogden and Dorothy Ogden, Appellants v. United States of America™ * *

E. B. Ogden, Jr. and Nancy A. Ogden, Appellants v. United States of America.

No. 75-4448. Georgia Power Co. vs. 54.20 Acres of Land, etc., et al.; Jim Dodson, et al., Appellants (Consolidated

with No. 77-1327 — J. C. Hilsman, et al., Appellants vs. Georgia Power Co.).

THURSDAY, JUNE 16, 1977

COURT CONVENES AT 9:00 A.M.

* No. 76-3681. United States of America vs. Erkan Ozmen, Appellant.

* No. 76-4111. United States of America vs. Lloyd Miley Mann, Appellant.

* No. 76-2478. United States of America vs. Edward Lee Timberlake, Appellant.

* No. 76-3086. United States of America v. John C. Herring, a/k/a Scooter, Appellant.

* No. 76-1116. Jean D. Muirhead v. Dr. Jeanne Bonar, et al., Appellants-Appellees.

EDWARD W. WADSWORTH

Clerk of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

NEW ORLEANS, LA.

It is the responsibility of counsel, under Rule 11(b) F.R.A.P., to make certain that any original documentary or

physical exhibits referred to in their brief or which may be needed for their argument are made available to the Court at

least fifteen days in advance of hearing.

The Court desires that counsel be aware in advance that oral arguments in all cases are now being tape recorded

for the exclusive use of the Court.

The Clerk's Office must be advised 30 minutes prior to convening of Court on the date of the hearing of the name

of Counsel to present oral argument.

New Orleans Clerk's Office: Room 102, 600 Camp Street

United States Court of Appeals Courthouse

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

A. C. 504 — 589-6514.

COURT CONVENES AT 9:30 A.M. EXCEPT ON THURSDAY WHEN COURT CONVENES AT 9:00 A.M.

*See Isbell Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizens Casualty Co. of New York, et al., 5th Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 409, Part I.

Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc.

New Orleans, Louisiana 5/10/77 — 139

” Cr AL we rt O A peals.

New Orleans, Louisiana

1

+ 1977

Dear Sir: 7

I hereby acknowledge receipt of copy of your printed calendar showing my case in re:

NO. ’ i Vs. ’

assigned for hearingat ______ A.M.on ,1977 in the En Banc Courtroom (Room 209) of

the United States Court of Appeals Courthouse, 600 Camp St., New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Clerk’s Office must be advised 30 minutes prior to convening ot Court on the date of the hearing of the name

of Counsel to present oral argument.

139-5 Attorney for