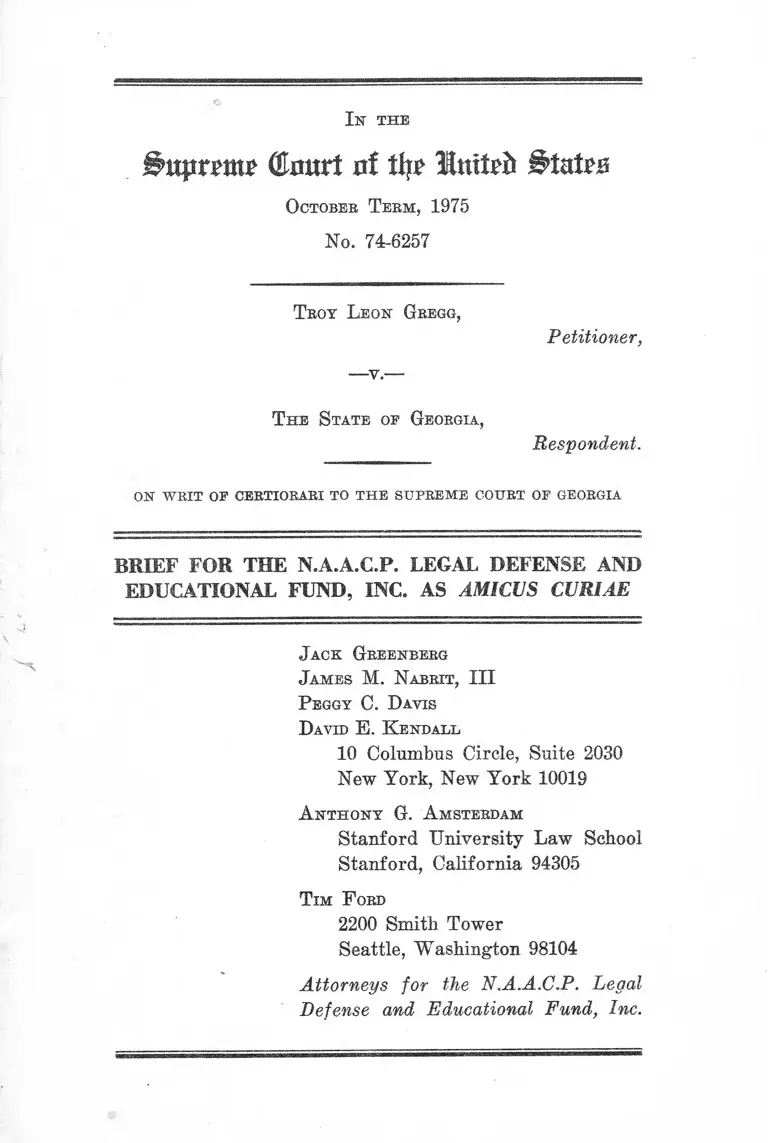

Gregg v. Georgia Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gregg v. Georgia Brief Amicus Curiae, 1975. 0272e7a0-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4286b61-0b4b-4548-a069-f65bf1d677f8/gregg-v-georgia-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(tart 0! tip ^tat^

October T erm, 1975

No. 74-6257

Troy L eon Gregg,

Petitioner,

—v.—

T he S tate oe Georgia,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU PR EM E COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL. DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

P eggy C. Davis

David E. K endall

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

T im F ord

2200 Smith Tower

Seattle, Washington 98104

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

I N D E X

Statement of Interest of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc........-.......... ............. .... . 1

Question Presented .................. ............. ...... ................. 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Statement of the Case ..................................— ...... — 14

How the Federal Question Was Raised and Decided

Below...... - .......-....... ..............................—...... —......... 21

Summary of Argument .................. —-.......-......— - 22

I. Introduction ............................ -.................... 24

II. The Arbitrary Infliction of Death ............... — 29

A. At the Pre-sentence Hearing .......... .......— 29

1. Georgia's 1973 Death Penalty Legislation

Is Explicitly Discretionary .........................29

2. The Consideration of Aggravating and

Mitigating Circumstances Does Not Con

trol Arbitrariness in the Georgia Capital

Sentencing Process .................................. 30

3. Appellate Reconsideration of Death Sen

tences Merely Ratifies the Arbitrariness

of the Georgia Capital Sentencing Proc

ess ................................. 40

4. The Results of the Georgia Sentencing

Process: Caprice and Arbitrariness ___ 49

B. Before and After the Pre-Sentencing Hear

ing ......... 53

PAGE

11

1. Prosecutorial Charging Discretion ........ 54

2. Plea Bargaining ........... 55

3. Jury Discretion.......................................... 58

4. Executive Clemency ................................. 65

III. The Excessive Cruelty of Death .......................... 67

Conclusion ..................................... 68

A ppendix .................................................................................... l a

T able op A uthorities

Cases:

Alford v. Eyman, 408 U.S. 939 (1972) .....-................... 40

Allen v. State, 233 Ga. 200, 210 S.E.2d 680 (1974).... . 51

Alvarez v. Nebrasxa, 408 U.S. 937 (1972) ................. 40,52

Arkwright v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) ............... 24

Atkins v. State, 228 Ga. 578,187 S.E.2d 132 (1972)...... 46

Ballard v. State, 131 Ga. App. 847, 207 S.E.2d 246

(1974) ........................................................................... 56

Banks v. State, 227 Ga. 578, 182 S.E.2d 106 (1971) .... 59

Barker v. State, 233 Ga. 781, 213 S.E.2d 624 (1975)..... 47

Barrow v. State, Ga. Sup. Ct., No. 30322 ................. 51

Billingsley v. New Jersey, 408 U.S. 934 (1972).......... 52

Bowen v. State, 225 Ga. 423, 169 S.E.2d 322 (1969).... 59

Brannen v. State, -----Ga.------ , 220 S.E.2d 264 (1975) 51

Brooks v. Sturdivant, 177 Ga. 514, 170 S.E. 369 (1933) 41

Brown v. State, Ga. Sup. Ct., No. 30362, Dec. 2, 1975

37, 38, 49

Brown v. State, 228 Ga. 215, 184 S.E.2d 655 (1971)..... 64

PAGE

PAGE

Caldwell v. Paige, 230 Ga. 456, 197 S.E.2d 692 (1973) 57

Callahan v. State, 229 Ga. 737, 194 S.E.2d 431 (1972) 25

Chenault v. State, 234 Ga. 216, 215 S.E.2d 223 (1975)

38, 49, 51, 64

Coker v. Georgia, No. 75-544-4 ...... .............................. . 2

Coker v. State, 234 Ga. 555, 216 S.E.2d 782 (1975)

38, 39, 45, 49, 51

Coley v. State, 231 Ga. 829, 204 S.E.2d 612 (1974)

22, 29, 33-34, 41, 45, 49, 51, 53

Collier v. State, 115 Ga. 803, 42 S.E. 226 (1902) ....... 41

Commonwealth v. Edwards, 380 Pa. 52, 110 A.2d 216

(1955) ......... ............. ...... ........................ .............. ..... 40

Commonwealth v. Green, 396 Pa. 137, 151 A.2d 241

(1959) ............................................................... ........... 41

Commonwealth v. Hough, 358 Pa. 247, 56 A.2d 84

(1948) ................ ...................................... ................... 40

Commonwealth v. Phelan, 427 Pa. 265, 234 A.2d 540

(1967) ........... ............ .................................................. 40

Cummings v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) ................. 24

Davis v. Connecticut, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) ................... 52

Duling v. Ohio, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) ....... ........... .......... 52

Dutton v. State, 228 Ga. 850, 188 S.E.2d 794 (1972) 46

Eberheart v. Georgia, No. 74-5174 ..... ..... ................ .... 2

Eberheart v. State, 232 Ga. 247, 206 S.E.2d 12 (1974)

22, 45, 49, 51

Echols v. State, 46 Ga. App. 668, 168 S.E. 790 (1933) 59

Edwards v. State, 121 Ga. 590, 49 S.E. 674 (1905) ..... 55

Fesmire v. Oklahoma, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) ........... . 40

Fesmire v. State, 456 P.2d 573 (Okla. Ct. Cr. App.

(1969) ........ .......................................................... ...... 40

Floyd v. State, 233 Ga. 280, 210 S.E.2d 810 (1974)

33, 45, 49

IV

Fowler v. North Carolina, No. 73-7031 ..................... 23, 53

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) ....2, 6, 23, 24, 34, 43,

48, 50, 51, 52, 53

Gaines v. State, 232 Ga. 727, 208 S.E.2d 798 (1974).... 39

Gaither v. State, 234 Ga. 465, 216 S.E.2d 324 (1975)

40, 51

Grant v. State, 120 Ga. App. 244, 170 S.E.2d 55 (1969) 64

Grantling v. State, 229 Ga. 746, 194 S.E.2d 405 (1972) 25

Gregg v. State, 233 Ga. 117, 210 S.E.2d 659 (1974) ....22,31,

44, 48, 49, 51, 59

Griffin v. State, 12 Ga. App. 615, 77 S.E. 1080 (1913)

55, 56, 57

Henderson v. State, 227 Ga. 68, 179 S.E.2d 76 (1970)

48, 59

Henderson v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 938 (1972)................ 24

Henderson v. State, 234 Ga. 827, 218 S.E.2d 612 (1975) 59

Herron v. Tennessee, 408 U.S. 937 (1972) ...... ............ 52

Hicks v. Brantley, 102 Ga. 264, 29 S.E. 459 (1897) ......54,55

Hill v. State, 232 Ga. 800, 209 S.E.2d 153 (1974) .......... 46

Holcomb v. State, 230 Ga. 525, 198 S.E.2d 179 (1973) 62

Holston v. State, 103 Ga. App. 373, 119 S.E.2d 302

(1961) .................. ....... .... .....................-.............. -....56,57

Hooks v. Georgia, No. 74-5954 .......................... ........... 2

Hooks v. State, 233 Ga. 149, 210 S.E.2d 668 (1974) .... 45,

49, 51,56

House v. Georgia, No. 74-5196 .................................... — 2

House v. State, 232 Ga. 140, 205 S.E.2d 217 (1974) .... 22,

34, 48, 49

Hurst v. Illinois, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) ........... ............. ... 40

PAGE

Jackson v. Georgia, 230 Ga. 181, 195 S.E.2d 921 (1973) 25

Jackson v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) ...................... 24

V

Jackson v. Georgia, 409 U.S. 1172 (1972) ..................... 24

Jackson v. State, 234 Ga. 549, 216 S.E.2J 834 (1975) . . 46

Jarrell v. State, 234 Ga. 410, 216 S.E.2d 258 (1975)

31, 46, 49

PAGE

Jarrard v. State, 206 Ga. 112, 55 S.E.2d 706 (1949) .. . 63

Jessen v. State, 234 Ga. 791, 218 S.E.2d 52 (1975) 39

Jones v. Smith, 228 Ga. 648, 187 S.E.2d 298 (1972) ...... 61

Jones v. State, 233 Ga. 662, 212 S.E.2d 832 (1975) ...... 39, 51

Jordan v. State, 233 Ga. 929, 214 S.E.2d 365 (1975) 49

Jurek v. Texas, No. 75-5394 .......................................23,53

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1938) .........................29,48

Leach v. State, 234 Ga. 467, 216 S.E.2d 326 (1975) ....46, 51

Lee v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) ............................ 24

Lee v. State, 74 Ga. App. 212, 39 S.E.2d 426 (1946) 59

Leonard v. State, 113 Ga. 435, 66 S.E.2d 251 (1909) 59

Lereh v. State, 234 Ga. 857, 218 S.E.2d 571 (1975) ....46,51

Lewis v. State, 451 P.2d 399 (Okla. Ct. Grim. App.

1969) ..................................... ............. ................ ........ 41

Linder v. State, 132 Ga. App. 624, 208 S.E.2d 630

(1974) ............................ 59,61

Lundy v. State, 119 Ga. App. 585, 168 S.E.2d 199

(1969) ..................................... 63

Manor v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) .................... . 24

Mason v. State, Ga. Sup. Ct., No. 30338, decided Jan.

7, 1976 .... 38,48,49

Massey v. State, 220 Ga. 883, 142 S.E.2d 832 (1965) 56

Massey v. State, 229 Ga. 846, 195 S.E.2d 28 (1972) ....25, 56

McCorquodale v. Georgia, No. 74-6557 ............ 2

McCorquodale v. State, 233 Ga. 369, 211 S.E.2d 577

(1974) ........................................ 45,49,56

McCrary v. State, 229 Ga. 733, 194 S.E.2d 480 (1972) 25

McGabee v. State, 133 Ga. App. 964, 213 S.E.2d 91

(1975) 55

VI

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971) .............. 52

Miller v. Georgia, 408 U.S, 938 (1972) ......................... 24

Miller v. State, 226 Ga. 730, 177 S.E.2d 253 (1970) .... 38

Mitchell v. State, 234 Ga. 160, 214 S.E.2d 900 (1975)

32, 45, 49

Mitchell v. State, 229 Ga. 781, 194 S.E.2d 414 (1972) .... 24

Moore v. Illinois, 408 U.S. 786 (1972) ____________ 52

Moore v. State, 233 Ga. 861, 213 S.E.2d 829 (1975)

33, 40, 42, 44, 45, 46,

47, 49, 55, 56

Morris v. State, 228 Ga. 39, 184 S,E.2d 82 (1971) ___ 46

Myers v. State, 97 Ga. 76, 25 S.E. 252 (1895) .............. 41

Nichols v. State, 17 Ga. App. 593, 87 S.E. 817 (1916) 54

Park v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972) ......................... 24

Park v. State, 206 Ga. 675, 58 S.E.2d 142 (1950) ...... 66

Pass v. State, 227 Ga. 730, 182 S.E.2d 779 (1971) ....46, 56

Patterson v. State, 124 Ga. 408, 52 S.E. 534 (1905).... 38

Payne v. State, 231 Ga. 755, 204 S.E.2d 128 (1974)..... 62

People v. Black, 367 111. 209, 10 N.E.2d 801 (1937).... 52

People v. Crews, 42 I11.2d 60, 244 N.E.2d 593 (1969).... 41

People v. Hurst, 42 I11.2d 217, 247 N.E.2d 614 (1969).... 40

People v. Sullivan, 245 111. 87, 177 N.E. 733 (1933)...... 52

Perry v. State, 78 Ga. App. 273, 50 S.E.2d 709 (1948) 59

Phelan v. Brierly, 408 U.S. 939 (1972)......................... 40

Prevatte v. State, 233 Ga. 929, 214 S.E.2d 365 (1975)

36, 37, 51

Ramsey v. State, 232 Ga. 15, 205 S.E.2d 286 (1974).... 38

Reeves v. State, 22 Ga. App. 628, 97 S.E. 115 (1918).... 59

Revill v. State, 235 Ga. 71, 218 S.E.2d 816 (1975)........ 64

Roberts v. Louisiana, No. 75-5844 ........................... ..... 53

Robinson v. State, 6 Ga. App. 696, 651 S.E. 792 (1909) 41

PAGE

Y ll

Robinson v. State, 109 Ga. 506, 34 S.E. 1017 (1900)..,. 61

Ross v. Georgia, No. 74-6207 ........ ................................ 2

Ross v. State, 233 Ga. 361, 211 S.E.2d 356 (1974)...... 47, 49

Ross v. State, 135 Ga. App. 169, 217 S.E.2d 170 (1975) 64

Rowland v. State, 72 Ga. App. 793, 35 S.E.2d 372 (1945) 57

Scott v. State, 53 Ga. App. 61, 185 S.E. 131 (1936).... 55

Shearer v. State, 128 Ga. App. 809, 198 S.E.2d 369

(1973) ............................................-........-................... 56

Sims v. State, 234 Ga. 177, 214 S.E.2d 902 (1975) ...... 51

Sims v. State, 203 Ga. 665, 47 S.E.2d 862 (1948) ...... . 58

Sirmans v. State, 229 Ga. 743, 194 S.E.2d 476 (1972) 25

Smith v. Embry, 103 Ga. App. 375,119 S.E.2d 45 (1961) 55

Smith v. Strozier, 226 Ga. 283, 174 S.E.2d 417 (1970) 54

Smithwick v. State, 199 Ga. 292, 34 S.E.2d 28 (1945) .... 41

Stapleton v. State,----- Ga. ——, 220 S.E.2d 269 (1975) 47,

51

State v. Alford, 98 Ariz. 124, 402 P.2d 551 (1965) ...... 40

State v. Floyd Allen, Gwinnett County Superior Court,

Indictment No. 9475 ............................. ..... .............—. 19

State v. Alvarez, 182 Neb. 358, 154 N.W.2d 746 (1967) 40

State v. Eaton, 19 Ohio St. 145, 249 N.E.2d 897 (1969) 52

State v. Hall, 176 Neb. 295, 125 N.W.2d 918 (1964) .. 41

State v. Maloney, 105 Ariz. 348, 464, P.2d 793 (1970) 41

State v. Reynolds, 41 N.J. 163, 195 A.2d 449 (1963)...... 52

State v. Tudor, 154 Ohio St. 249, 95 N.E.2d 285 (1950) 52

Stein v. New York, 346 TJ.S. 156 (1953) ....................... 65

Stevens v. State, 228 Ga. 621, 187 S.E,2d 281 (1972) .... 46

Sullivan v. Georgia, 408 TJ.S. 935 (1972) ........... .......... 24

Sullivan v. State, 229 Ga. 731, 194 S,E.2d 411 (1972) 25

Sundahl v. State, 154 Neb. 550, 48 N.W.2d 689 (1951) 52

Tamplin v. State, 235 Ga. 20, 218 S.E.2d 779 (1975)

37,46-47, 49, 51

Thacker v. Georgia, 408 TJ.S. 936 (1972) ..................... 24

PAGE

V lll

Thomas v. State, 233 Ga. 237, 210 S.E.2d 675 (1974) 51

Thomason v. Caldwell, 229 Ga. 637, 194 S.E.2d 112

(1972) ...... ................. -........................................... -.... 57

Underhill v. State, 129 Ga, App. 65, 198 S.E.2d 703

(1973) .......................................................................... 55

Walker v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) ..................... 24

Walker v. State, 5 Ga. App. 606, 63 S.E. 605 (1909) .... 38

Walker v. State, 132 Ga, App. 476, 208 S.E.2d 350

(1974) ............................................... - ........................ 41

Waller v. State, 107 Ga. App. 609, 131 S.E.2d 111

(1963) .............................. ................................ - .....-- 59

Ward v. State, 231 Ga. 484, 202 S.E.2d 421 (1973) ....61, 62

Waters v, Walkover Shoe Shop, 142 Ga. 137, 82 S.E.

537 (1914) .................................................................- 55

Watson v. State, 229 Ga. 787, 194 S.E,2d 407 (1972) 25

Webb v. Henlery, 209 Ga. 447, 74 S.E.2d 7 (1953) .... 54

Wilburn v. State, 230 Ga. 675, 198 S.E.2d 857 (1973) 25

Williams v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) .............. . 24

Williams v. State, 126 Ga. 454, 191 S.E.2d 100 (1972) 63

Williams v. State, 232 Ga. 203, 206 S.E.2d 37 (1974)....63, 64

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ........... . 53

Wood v. State, 234 Ga, 758, 218 S.E.2d 47 (1975) ..... 51

Woodruff v. State, 164 Tenn. 530, 51 S.W.2d 843 (1932) 52

Woolfolk v. State, 81 Ga. 558, 8 S.E. 724 (1889) . 41

York v. State, 226 Ga. 281, 174 S.E.2d 418 (1970) .... 63

Ga. ------, 219 S.E.2d 389 (1975)

46, 47, 51

PAGE

Zirkle v. State,

IX

Statutes:

United States Constitution, Eighth Amendment ........ 3

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment .... 3

Ariz. Rev. Stat. §13-1717 (1956) .................................. 40

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §53-10 (1967) .................... ...... 52

Ga. Const. Ann. §2-3011 (1972) ..................... .............. 65, 66

Ga. Code Ann. §24-2908(2), (1971) ........................... 54

Ga. Code Ann. §26-505 (1972) .................................... 58

Ga. Code Ann. §26-901 (a) (1972) ...... 62

Ga. Code Ann. §26-901 (f) (1972) ............................... 63

Ga. Code Ann. §26-902 (1972) .................................. 62-63

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1004 (1972) .......................... 61

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1101 (1972) ..............................3, 59-60

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1102 (1972) ..................................... 60

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1303 (1972) ..................................... 61

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1305 (1972) ..................................... 32

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1311 (1972) ..................... 3,32

Ga. Code Ann. §26-1902 (1972) ..................................... 4

Ga. Code Ann. §26-2001 (1972) ................... 4

Ga. Code Ann. §26-2201 (1972) .................................... 5

Ga. Code Ann. §26-2401 (1972) ..................................... 26

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3102 (1975 Supp.) ........ 5,25,28,33,35

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3301 (1972) ......... 5

Ga. Code Ann. §27-1801 (1973) ..................................... 55

PAGE

X

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 (1975 Snpp.) ....................... 6

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2508 (1972) ............. 61

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2512 (1972) .................................... 7

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2514 (1975 Supp,) ...... 7

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2527(c) (3) ... 44

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2528 (1975 Supp.) ......... 14,25,55,56

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (1975 Snpp.) .............. 8,25,26

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(b) (1975 Supp.) ....25,26,31,36

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(b) (1) (1975 Supp.) .29,35

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2554.1(b) (2) (1975 Supp.) .........31,35

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(b) (3) (1975 Supp.) .......... 35

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(b) (4) (1975 Supp.) ........ 31

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(b) (5) (1975 Supp.) ........ 31

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (b) (6) (1975 Supp.) .......... 31

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (b) (7) (1975 Supp.) ........32,33,

35

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534,1(e) (1975 Supp.) ...... 28,33,36

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537 (1975 Supp.) .............. 10,25,28

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537(c) (1975 Supp.) ......... .28,43,44,

47, 48

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537(e) (1975 Supp.) ................. 28

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537(f) (1975 Supp.) ................. 48

Ga. Code Ann. §77-501 (1973) ..... 65

Ga. Code Ann. §77-511 (1972) .................................... 65

PAGE

X I

Ga. Code Ann. §77-513 (1975 Supp.) .........................65-66

Ga. Laws 1973, Act. No. 74 ..................... .12, 25, 28, 33, 38

Ga. Laws 1974, Act. No. 854 ....................................... 6,12

111. Eev. Stat. c. 38, §1-7(c)(1) .................................... 52

Neb. Eev. Stat. §29-2308 (1943) .................................... 40

N.J. Stat. Ann. §2A: 113-4 (1969) ................................ 52

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-2406 (1955) ............ .......... ......... 52

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Black, Capital P unishm ent; T he I nevitability op

Caprice and Mistake (1974) .............................23, 35, 50, 57

Brewster, The Georgia Death Penalty Statute—Is It

Constitutional, Even After Revision? 3 Ga. J. Corr,

(No. 1) 14 (1974) ............................................................ 43,47

Browning, The New Death Penalty Statutes: Per

petuating a Costly Myth, 9 Gonzaga L. E ev. 651

(1974) ..................................................................................... 31

Cardozo, L aw and L iterature (1931) ............................... 58

Comment, Constitutional Law—Capital Punishment—

Furman v. Georgia and Georgia’s Statutory Re

sponse, 24 Mercer L. R ev. 891 (1973) ........................36, 39

Note, Discretion and the New Death Penalty Statutes,

87 H arv. L. Rev. 1690 (1974) ......................................... 31

Note, Executive Clemency in Capital Cases, 39 N.Y.U.

L. R ev. (1969) ................................................

Goldstein : The Insanity Defense (1967)

66

64

K alvin & Zeisel : T he A merican J ury (1966) ..... ....62, 64

P resident’s Commission on L aw E nforcement and

the A dministration of J ustice, T ask F orce Re

port :The Courts 9 (G.P.O. 1967) ........................... 57

R oyal, Commission on Capital P unishment 1949-1953,

R eport 174 (H.M.S.O. 1973) ...................................... 52

X l l

PAGE

I n t h e

Court of % Inttrtu Stairs

October T erm, 1975

No. 74-6257

Troy Leon Gregg,

Petitioner,

—v.—

T he State of Georgia,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E SU PR EM E COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

Statement o f Interest of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

(1) The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation formed to assist

black citizens in securing their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits.

(2) The experience of Legal Defense Fund attorneys in

handling capital cases over a period of many years con

vinced us that the death penalty is customarily applied in

a discriminatory manner against racial minorities and the

economically underprivileged. Further study and reflec

tion led us to the conclusion that the evil of discrimination

was not merely adventitious, but was rooted in the very

2

nature of capital punishment. Accordingly, in 1967, the

Legal Defense Fund undertook to represent all condemned

men in the United States, regardless of race, for whom ade

quate representation could not otherwise he found. Addi

tionally, the Fund provided consultative assistance to at

torneys representing a large number of other condemned

defendants.

(3) Since this Court’s decision in Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972), the Legal Defense Fund has continued

to provide legal assistance to indigent condemned prisoners

of all races. Fund attorneys now represent on appeal more

than one hundred death-sentenced defendants. Among these

are a number of prisoners condemned under Georgia’s 1973

death penalty statutes; and we have filed certiorari peti

tions in this Court on behalf of six such prisoners. Eber-

heart v. Georgia, No. 74-5174; House v. Georgia, No.

74-5196; Hoolcs v. Georgia, No. 74-5954; Ross v. Georgia,

No. 74-6207; McCorquodale v. Georgia, No. 74-6557; Coker

v. Georgia, No. 75-5444.

(4) The Court’s decision in the instant case may resolve

the constitutional issues upon which the lives of these six

men and our other Georgia clients depend.

(5) Consent has been given by petitioner and respondent

for the filing of this brief amicus curiae.

Question Presented

Whether the imposition and carrying out of the sen

tence of death for the crime of murder under the law of

Georgia violates the Eighth or Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the Eighth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, which provides:

“Excessive hail shall not he required nor excessive fines

imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted.”

It also involves the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

2. This case further involves the following provisions

of the Code of Georgia:

Ga. Code Ann. %26-UOl (1972)

“Murder, (a) A person commits murder when he

unlawfully and with malice aforethought, either ex

press or implied, causes the death of another human

being. Express malice is that deliberate intention

unlawfully to take away the life of a fellow creature,

which is manifested by external circumstances cap

able of proof. Malice shall be implied where no con

siderable provocation appears, and where all the cir

cumstances of the killing show an abandoned and

malignant heart.

(b) A person also commits the crime of murder

when in the commission of a felony he causes the

death of another human being, irrespective of malice.

(c) A person convicted of murder shall be punished

by death or by imprisonment for life.”

Ga. Code Ann. %26-13U (1972)

“Kidnapping, (a) A person commits kidnapping

when he abducts or steals away any person without

4

lawful authority or warrant and holds such person

against his will.

(b) A person over the age of 17 commits kidnap

ping when he forcibly, maliciously, or fraudently leads,

takes, or carries away, or decoys or entices away, any

child under the age of 16 years against the will of

the child’s parents or other person having lawful

custody.

A person convicted of kidnapping shall be punished

by imprisonment for not less than one nor more than

20 years: provided that a person convicted of kid

napping for ransom shall be punished by life im

prisonment or by death.”

Ga. Code Ann. %26-1902 (1972)

“Armed robbery. A person commits armed robbery

when, with intent to commit theft, he takes property

of another from the person or the immediate presence

of another by use of an offensive weapon. The offense

robbery by intimidation shall be a lesser included

offense in the offense of armed robbery. A person

convicted of armed robbery shall be punished by death

or imprisonment for life, or by imprisonment for

not less than one nor more than 20 years.”

Ga. Code Ann. %26-2001 (1972)

“Rape. A person commits rape when he has carnal

knowledge of a female, forcibly and against her will.

Carnal knowledge in rape occurs when there is any

penetration of the female sex organ by the male sex

organ. A person convicted of rape shall he punished

by death or by imprisonment for not less than one

nor more than 20 years. No conviction shall be had

for rape on the unsupported testimony of the female.”

5

Ga. Code Ann. %26-2201 (1972)

“Treason. A person owing allegiance to the State

commits treason when he knowingly levies war against

the State, adheres to her enemies, or gives them aid

and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason

except on the testimony of two witnesses to the same

overt act, or on confession in open court. When the

overt act of treason is committed outside this State,

the person charged therewith may be tried in any

county in this State. A person convicted of treason

shall be punished by death, or by imprisonment for

life or for not less than 15 years.”

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3301 (1972)

“Definition: punishment; continuing offense; juris

diction.

A person commits hijacking of an aircraft when he

(1) by use of force; or (2) by intimidation, by use

of threats or coercion, places the pilot of an aircraft

in fear of immediate serious bodily injury to himself

or to another, causes the diverting of an aircraft

from its intended destination to a destination dic

tated by such person. A person convicted of hijacking

an aircraft shall be punished by death or life im

prisonment. The offense of hijacking is declared to

be a continuing offense from the point of beginning

and jurisdiction to try a person accused of the offense

of hijacking shall be in any county of Georgia over

which the aircraft is being operated.

Ga. Code Ann. §26-3102 (1975 Supp.)

“Capital offenses; jury verdict and sentence. Where,

upon a trial by jury, a person is convicted of an of

fense which may be punishable by death, a sentence

6

of death shall not be imposed unless the jury verdict

includes a finding of at least one statutory aggravat

ing circumstance and a recommendation that such sen

tence be imposed. Where a statutory aggravating

circumstance is found and a recommendation of death

is made, the court shall sentence the defendant to im

prisonment as provided by law. Unless the jury try

ing the case makes a finding of at least one statutory

aggravating circumstance and recommends the death

sentence in its verdict, the court shall not sentence

the defendant to death, provided that no such finding

of statutory aggravating circumstance shall he neces

sary in offenses of treason or aircraft hijacking. The

provisions of this section shall not affect a sentence

when the case is tried without a jury or when the

judge accepts a plea of guilty.”

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 (1975 Supp.)1

“Recommendation to mercy. In all capital cases,

other than those of homicide, when the verdict is

1 At the time of petitioner’s trial, Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 pro

vided :

“In all capital cases, other than those of homicide, when the

verdict is guilty, with a recommendation to mercy, it shall be

legal and shall mean imprisonment for life.”

“When the verdict is guilty without a recommendation to

mercy it shall be legal and shall mean that the convicted per

son shall be sentenced to death. However, when it is shown

that a person convicted of a capital offense without a recom

mendation to mercy had not reached his seventeenth birthday

at the time of the commission of the offense the punishment

of such person shall not be death but shall be imprisonment

for life.”

Sec. 27-2302 was part of Georgia’s capital-sentencing laws before

Furman v. Georgia, and was not amended by the 1973 statute,

whose provisions (Ga. Code Ann. §§26-3102, 27-2534.1 (c)) were

consistent with it. The present language is the result of a 1974

amendment. Ga. Laws, 1974, p. 353, Act. No. 854. See Editorial

Comment to Ga. Code Ann. §27-2302 (1975 Supp.).

7

guilty, with a recommendation to mercy, it shall be

a recommendation to the judge of imprisonment for

life. Such recommendation shall be binding upon the

judge.”

Ga. Code Ann. %27-2512 (1972)

“Electrocution substituted for hanging; place of exe

cution. All persons who shall be convicted of a capital

crime and who shall have imposed upon them the sen

tence of death shall suffer such punishment by electro

cution instead of hanging.”

Ga. Code Ann. %27-25M (1975 Supp.)

“Sentence of death; copy for penitentiary superin

tendent. Time and mode of conveying prisoner to peni

tentiary. Expenses. Upon a verdict or judgment of

death made by a jury or a judge, it shall be the duty

of the presiding judge to sentence such convicted per

son to death and to make such sentence in writing,

which shall be filed with the papers in the case against

such convicted person, and a certified copy thereof

shall be sent by the clerk of the court in which said

sentence is pronounced to the superintendent of the

State penitentiary, not less than 10 days prior to the

time fixed in the sentence of the court for the execu

tion of the same; and in all cases it shall be the duty

of the sheriff of the county in which such convicted

person is so sentenced, together with one deputy or

more, if in his judgment, it is necessary, and provided

that in all cases the number of guards shall be ap

proved by the trial judge, or if he is not available, by

the ordinary of said county in which such prisoner is

sentenced, to convey such convicted person to said

penitentiary, not more than 20 days nor less than two

8

days prior to the time fixed in the judgment for the

execution of such condemned person, unless otherwise

directed by the Governor, or unless a stay of execu

tion has been caused by appeal, granting of a new trial

or other order of a court of competent jurisdiction,

and the expense for transporting of said person to

the penitentiary for the purpose of electrocution shall

be paid by the ordinary of the county wherein the

conviction was had, or the board of county commis

sioners, the county commissioner, or other person or

persons having charge of the county funds, out of any

fines on hand in the treasury of such county.”

Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (1975 Supp.)

“Mitigating and aggravating circumstances; death

penalty, (a) The death penalty may be imposed for

the offenses of aircraft hijacking or treason, in any

case.

(b) In all cases of other offenses for which the death

penalty may be authorized, the judge shall consider,

or he shall include in his instructions to the jury for

it to consider, any mitigating circumstances or aggra

vating circumstances otherwise authorized by law and

any of the following statutory aggravating circum

stances which may be supported by the evidence:

(1) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

kidnapping was committed by a person with a prior

record of conviction for a capital felony, or the of

fense of murder was committed by a person who has

a substantial history of serious assaultive criminal

convictions.

(2) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

^ kidnapping was committed while the offender was en-

9

gaged in the commission of another capital felony, or

aggravated battery, or the offense of murder was

committed while the offender was engaged in the com

mission of burglary or arson in the first degree.

(3) The offender by his act of murder, armed rob

bery, or kidnapping knowingly created a great risk

of death to more than one person in a public place by

means of a weapon or device which would normally

be hazardous to the lives of more than one person.

(4) The offender committed the offense of murder

for himself or another, for the purpose of receiving

money or any other thing of monetary value.

(5) The murder of a judicial officer, former judicial

officer, district attorney or solicitor or former district

attorney or solicitor during or because of the exercise

of his official duty.

(6) The offender caused or directed another to com

mit murder or committed murder as an agent or em

ployee of another person.

(7) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

kidnapping was outrageously or wantonly vile, hor

rible or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity

of the mind, or an aggravated battery to the victim.

(8) The offense of murder was committed against „__

any peace officer, corrections employee or fireman while

engaged in the performance of his official duties.

(9) The offense of murder was committed by a per

son in, or who has escaped from, the lawful custody of

a peace officer or place of lawful confinement.

(10) The murder was committed for the purpose of

avoiding, interfering with, or preventing a lawful ar-

1 0

rest or custody in a place of lawful confinement, of

himself or another.

(c) The statutory instructions as determined by the

trial judge to be warranted by the evidence shall be

given in charge and in writing to the jury for its de

liberation. The jury, if its verdict be a recommenda

tion of death, shall designate in writing, signed by the

foreman of the jury, the aggravating circumstance or

circumstances which it found beyond a reasonable

doubt. In non-jury cases the judge shall make such

designation. Except in cases of treason or aircraft

hijacking, unless at least one of the statutory aggra

vating circumstances enumerated in section 27-2534.1

(b) is so found, the death penalty shall not be imposed.”

Ga. Code Ann, §27-2537 (1975 Supp.)

“Review of death sentences, (a) Whenever the death

penalty is imposed, and upon the judgment becoming

final in the trial court, the sentence shall be reviewed

on the record by the Supreme Court of Georgia. The

clerk of the trial court, within ten days after receiving

the transcript, shall transmit the entire record and

transcript to the Supreme Court of Georgia together

with a notice prepared, by the clerk and a report pre

pared by the trial judge. The notice shall set forth

the title and docket number of the case, the name of

the defendant and the name and address of his attor

ney, a narrative statement of the judgment, the of

fense, and the punishment prescribed. The report shall

be in the form of a standard questionnaire prepared

and supplied by the Supreme Court of Georgia.

(b) The Supreme Court of Georgia shall consider

the punishment as well as any errors enumerated by

way of appeal.

11

(c) With regard to the sentence, the court shall

determine:

(1) Whether the sentence of death was imposed un

der the influence of passion, prejudice, or any oilier

arbitrary factor, and

(2) Whether, in cases other than treason or aircraft

hijacking, the evidence supports the jury’s or judge’s

finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance as

enumerated in Code section 27-2534.1 (b), and

(3) Whether the sentence of death is excessive or

disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar

cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.

(d) Both the defendant and the State shall have the

right to submit briefs within the time provided by the

court, and to present oral argument to the court.

(e) The court shall include in its decision a refer

ence to those similar cases which it took into consider

ation. In addition to its authority regarding correc

tion of errors, the court, with regard to review of

death sentences, shall be authorized to :

(1) Affirm the sentence of death; or

(2) Set the sentence aside and remand the case for

resentencing by the trial judge based on the record

and argument of counsel. The records of those similar

cases referred to by the Supreme Court of Georgia in

its decision, and the extracts prepared as hereinafter

provided for, shall be provided to the resentencing

judge for his consideration.

(f) There shall be an Assistant to the Supreme

Court, who shall be an attorney appointed by the Chief

-Justice of Georgia and who shall serve at the pleasure

12

of the court. The court shall accumulate the records

of all capital felony cases in which sentence was im

posed after January 1, 1970, or such earlier date as

the court may deem appropriate. The Assistant shall

provide the court with whatever extracted information

it desires with respect thereto, including but not lim

ited to a synopsis or brief of the facts in the record

concerning the crime and the defendant.

(g) The court shall be authorized to employ an ap

propriate staff and such methods to compile such data

as are deemed by the Chief Justice to be appropriate

and relevant to the statutory questions concerning the

validity of the sentence.

(h) The office of the Assistant shall be attached to

the office of the Clerk of the Supreme Court of Georgia

for administrative purposes.

(i) The sentence review shall be in addition to direct

appeal, if taken, and the review and appeal shall be

consolidated for consideration. The court shall ren

der its decision on legal errors enumerated, the fac

tual substantiation of the verdict, and the validity of

the sentence.”

Ga. Laws, 1973, p. 159, 162, Act. No. 74?

“At the conclusion of all felony cases heard by a

jury, and after argument of counsel and proper charge

from the court, the jury shall retire to consider a ver

dict of guilty or not guilty without any consideration

of punishment. Where the jury or judge returns a 2

2 This section was modified in certain respects by Ga. Laws, 1974,

pp. 355-358, Act No. 854, which also provided that the section

would he designated Ga. Code Ann. §27-2503. These modifications

were insubstantial with respect to the trial of capital felonies.

13

verdict or finding of guilty, the court shall resume the

trial and conduct a pre-sentence hearing before the

jury or judge at which time the only issue shall be

the determination of punishment to be imposed. In

such hearing, subject to the laws of evidence, the jury

or judge shall hear additional evidence in extenuation,

mitigation, and aggravation of punishment, including

the record of any prior criminal convictions and pleas

of guilty or pleas of nolo contendere of the defendant,

or the absence of any such prior criminal convictions

and pleas; provided, however, that only such evidence

in aggravation as the State has made known to the

defendant prior to his trial shall be admissible. The

jury or judge shall also hear argument by the defen

dant or his counsel and the prosecuting attorney, as

provided by law, regarding the punishment to be im

posed. The prosecuting attorney shall open and the

defendant shall conclude the argument to the jury or

judge. Upon the conclusion of the evidence and argu

ments, the judge shall give the jury appropriate in

structions and the jury shall retire to determine the

punishment to be imposed. In cases in which the death

penalty may be imposed by a jury or judge sitting

without a jury, the additional procedure provided in

Code section 27-2534.1 shall be followed. The jury, or

the judge in cases tried by a judge, shall fix a sentence

within the limits prescribed by law. The judge shall

impose the sentence fixed by the jury or judge, as pro

vided by law. If the jury cannot, within a reasonable

time, agree to the punishment, the judge shall impose

sentence within the limits of the law ; provided, how

ever, that the judge shall in no instance impose the

death penalty when, in cases tried by a jury, the jury

cannot agree upon the punishment. If the trial court

14

is reversed on appeal because of error only in the pre

sentence hearing, the new trial which may be ordered

shall apply only to the issue of punishment.”

Ga. Code Ann, %27-2528 (1975 Supp.)

“Sentence to life imprisonment or lesser punishment

hy judge on plea of guilty to an offense punishable by

death. Any person who has been indicted for an of

fense punishable by death may enter a plea of guilty

at any time after his indictment, and the judge of the

superior court having jurisdiction may, in his discre

tion, during term time or vacation, sentence such per

son to life imprisonment, or to any punishment au

thorized by law for the offense named in the indict

ment. Provided, however, that the judge of the supe

rior court must find one of the statutory aggravating

circumstances provided in Code section 27-2534.1 be

fore imposing the death penalty except in cases of

treason or aircraft hijacking.”

Statem ent o f the Case

Petitioner Troy Leon Gregg was indicted by a Gwinnett

County, Georgia, grand jury, upon two counts of murder

and two counts of armed robbery for the November 21,

1973 killings of Fred Edward Simmons and Bob Dur-

wood (“Tex”) Moore. The indictments alleged that Gregg

“unlawfully with malice aforethought” killed each of the

victims “by shooting [him] . . . with a certain pistol”

(T. 424, 425), and that “with the intent to commit theft”

he did “take from the person” of the two victims “A red

and white 1960 Pontiac, Florida Tag Number 7W85381”

and “Four hundred dollars” “hy the use of a certain

pistol, . . . an offensive weapon . . . (T. 424, 425).

15

On November 21, 1973, petitioner was hitchhiking from

St. Cloud, Florida to his home in Ashville, North Caro

lina, accompanied by one Floyd Ralford “Sam” Allen.

(T. 122, 309-311). They were picked up just outside of

St. Cloud by two men, Fred Simmons and Bob Moore,

in a 1960 Ford. (T. 312.) Though it was early morning,

Moore and Simmons had been drinking, and after a few

miles asked petitioner Gregg to drive. (T. 313.)

Gregg complied, but after some distance, the Ford broke

down. (T. 313.) A passing Florida Highway Patrolman,

Daniel James Cobb, saw the disabled vehicle and called

a wrecker. Leaving Gregg and Allen at the site of the

breakdown, the patrolman then took Simmons and Moore

to a used ear dealer in nearby Winter Garden, where

Simmons purchased another car, a 1960 red and white

Pontiac. (T. 209-210.) Trooper Cobb noticed that Moore

had what “looked like a considerable amount of money”

at the time of the purchase. (T. 212.)

Simmons and Moore returned to pick up Gregg and

Allen, and the four continued north, again with Gregg

driving. (T. 314.) In northern Florida they encountered

another hitchhiker, Dennis Weaver, who rode with them

until they reached his destination, Atlanta, at approx

imately eleven o’clock that evening. (T. 120-130.) WTeaver

testified that during this time there was no evidence of

hostility among the men in the car, though Moore and

Simmons were drinking heavily (T. 125-126), and though

he was frightened by Simmons’ and Moore’s talk about

their jail experiences and by “the situation” (T. 146-147),

After letting Weaver out, the four men continued north

ward into Gwinnett county to the intersection of 1-85

and Georgia Highway 20, where Moore and Simmons asked

Gregg to stop the car so they could relieve themselves.

16

(T. 319.) Their bodies were found there early the next

morning. (T. 221.) Autopsies showed that both men had

died of gunshot wounds to the head from a small caliber

pistol. (T. 92, 96.) Moore had been shot once in the

right cheek and once in the back of the head (T. 92),

Simmons once near the right temple (T. 97). Both men

had several bruises and abrasions of unknown origin

about the face and head (T. 95, 107-110),3 and both bodies

had blood alcohol contents indicating that the two men

were heavily intoxicated at the time of death (T. 101).

On November 23, Dennis Weaver read in an Atlanta

newspaper about the discovery of the dead men and con

tacted the Gwinnett County Police Department. (T. 131-

133.) He told the police of his contact with the four men

two days before, gave them a description of Gregg and

Allen and of Simmons’ Pontiac, and gave them his im

pression that their destination was Ashville, North Caro

lina. (T. 134, 239.) Based on this information the police

broadcast a description of the car and suspects (T. 239),

which resulted in petitioner’s arrest at three o’clock the

3 Dr. James Bryan Dawson, who performed the autopsies, was

unable to determine whether these minor injuries were incurred

before or after the gunshot wounds, though as to Simmons he _was

able to say they were inflicted “not earlier than two to three hours

before” death. (T. 104-105, 109-110.) He noted that the wounds

were all “consistent with the face of the subject having been

dragged or pushed along . . . a surface” similar to the embank

ment next to which the bodies were found. (T. 112.) He agreed

that some of the injuries, to Simmons, at least, could have resulted

from a fight (T. 102, 105), but concluded that they “were prob

ably sustained from a fall into this ditch.” (T. 105.) Dr. Dawson

also testified that he found dried blood on Moore’s right hand that

“was not like the remainder of the dried blood that was found on

the face . . . or around the body” (T. 106), but which he did not

analyze (ibid.), though he “particularly looked for signs of in

juries to the hands which might have suggested that there was

some sort of altercation or . . . defense . . . and found nothing on

either one of the subject’s hands, which suggested that this might

have taken place” (T. 110).

17

next afternoon. (T. 164-165.)4 At the time of his arrest

Gregg was driving the 1960 Pontiac which Simmons had

purchased (T. 165, 169), and had in his pocket $107.00

in cash and a pistol later shown to be that which killed

Moore and Simmons (ibid.). A search of the car inci

dent to this arrest produced Simmons’ bill of sale for

the car. (T. 168.)

Gregg was given Miranda warnings about five minutes

after he was stopped (T. 170-171), and signed a written

waiver of his rights at 3:17 p.m. (T. 516). He was not in

terrogated until eleven o’clock that evening, when he told

Detective Bert H. Blannott of the Gwinnett County Police

that “he understood his rights” (T. 281),5 and made a

partially exculpatory statement. He admitted shooting

Simmons and Moore, but claimed to have done it in self-

defense. (T. 282-283.) In the statement, which he read

and signed (T. 322), Gregg said that Moore and Sim

mons were “going to put me and Sam out” and “wouldn’t

give us our clothes and stuff and we got in a fight.”

(T. 518.)

“Fred smacked me down, a bank and then him and Tex

both jumped on Sam. Fred had some kind of pipe

and I backed up and fell in the ditch again. One of

them had a knife and I wasn’t about to let either one

of them cut me. . . . I shot Fred to keep him off of me

and I shot Tex twice. Then we took about four or five

hundred dollars off them and left in their car.”

4 The constitutionality of this warrantless arrest for “investiga

tion” (T. 183), and the admissibility of its fruits, was the subject

of considerable dispute at trial (T. 183-203), and a ground of

Gregg’s appeal.

5 The Miranda warnings that had been given prior to 3 :17 p.m.

were not repeated before the 11:00 p.m. interrogation. (T. 297.)

1 8

(Ibid.) Shortly after the conclusion of his statement, how

ever, when Ashville police officer William Gibson asked

Gregg “why he shot these people,” Gregg answered “by

God I wanted them dead” (T. 379).

At approximately one o’clock on November 25, Gregg

(together with Allen) was removed from Ashville to Law-

renceville, Georgia, by the Gwinnett County Police and Dis

trict Attorney. (T. 284.) At approximately 5:00 they

stopped at the scene of the killings “to establish in our own

minds with the help of the defendants just exactly [what]

had taken place.” (T. 290.) All of the parties got out of

the cars, and Detective Blannott asked Allen, in Gregg’s

presence, what had happened. (T. 286.) According to Blan-

nott’s testimony:

“Sam [Allen] told us as soon as [Simmons and Moore]

. . . got out, Troy [Gregg] turned around and told him,

he said, get out, we’re going to rob them. Sam told us

that he got out and walked toward the back of the car

and looked around and could see Troy at the car, with

a gun in his hand, laying up on the car, so he could

get a good aim, the two men had gone down the bank

and had relieved themselves and as they were coming

back up the bank, according to Say [sic], Troy fired

three shots, one of the men fell, the other staggered,

Troy then circled back around the back, or rear of the

car and approached the two men, both of which were

now laying in the ditch. He placed the gun to ones [sic]

head and pulled the trigger then went quickly to the

other one and placed the gun to his head and pulled

the trigger again, he then took the money, whatever

contents were in their pockets, he told Sam, to get

in the car and they drove away.”

(T. 287.) Blannott testified that Gregg was then asked “if

that was how it happened” and said “yes, it was.” (Ibid.)

19

“Chief Crcmkleton then asked him . . . ‘yon mean yon

shot these men down in cold blooded murder just to

rob them’ and Troy replied, ‘yes,’ and Chief asked him

why and he said he didn’t know.”

(T. 288.)

Petitioner’s trial began February 4, 1974. A jury was

selected,6 and four days of proceedings were held. The

State’s evidence is summarized above.7 Petitioner was the

sole witness in his own behalf. He testified at trial, as he

had claimed when first interrogated following his arrest,

that he had shot Moore and Allen in self-defense and de

fense of Allen. (T. 320.)8 On cross-examination the State

produced a letter written by Gregg to Allen asking Allen

to renounce his previous statements and provide a “State

ment for you” containing a version of the killings consistent

with Gregg’s trial testimony. (T. 350-354, 521-528.) Gregg

6 Three veniremen were challenged by the state and excused by

the court without objection because of their affirmative answer’s

when asked if they would “vote against imposition of the death

penalty without regard to any evidence that might be developed

at the trial of the case.” (T. 2, 3, 31.)

7 “Sam” Allen did not testify at Gregg’s trial, but his statement

in Gregg’s presence was recounted (T. 286), and he appeared in

court to be identified (T. 138). The murder charges pending

against him at the time were “nol pressed” when he pled guilty

to the robbery counts, receiving concurrent twenty-year sentences,

six weeks later. See State v. Floyd Allen, Gwinnett County Supe

rior Court, Indictment #9475.

8 Petitioner admitted making the signed statement containing his

earlier claim of self-defense (T. 322), but denied agreeing with

Allen’s version of the facts at the scene of the killings. (T. 323,

350). He also denied Officer Gibson’s testimony that he had said

he shot Moore and Simmons because “I wanted them dead.” (T.

381.) He said that he had not taken any money from the dead

men (T. 346), hut suggested that Alien may have done so. He

testified that Allen had paid for everything that the two men had

purchased after the killings (T. 329-330), and that Gregg had been

given the money found on him at the time of his arrest as repay

ment of a loan after his return to Ashville. (T. 331-336.)

20

admitted writing parts of the letter hut denied writing

others. {Ibid.) In rebuttal the State called a document

examiner who testified that the whole letter was written

by Gregg. (T. 361.)

The trial judge submitted the murder charge to the jury

on both felony-murder and non-felony-murder theories.

(T. 428-429.) It instructed on the issue of self-defense

raised by petitioner’s testimony (T. 430-431) but declined

to instruct on manslaughter (T. 451). On the murder

counts, it therefore authorized the jury to return verdicts

of guilty or not guilty (T. 441); and on the robbery counts

it authorized verdicts of guilty of armed robbery, guilty of

robbery by intimidation, or not guilty (Ibid.). The jury

returned verdicts of guilty on all four counts. (T. 453.)

A pre-sentence hearing was conducted the same day. No

evidence was offered at that hearing (T. 459), but counsel

for both sides made lengthy arguments, dealing generally

with the propriety of capital punishment under the cir

cumstances and with the weight of the evidence of guilt.

(T. 459-477.)

The court charged the jury that it could recommend

either a death sentence or a prison sentence upon each

count. (T. 478.) It further charged that, in order to rec

ommend a death sentence upon any count, the jury first

had to find true beyond a reasonable doubt one of three

aggravating circumstances:

“One—That the offense . . . was committed while the

offender was engaged in the commission of two other

eapitol [sic] felonies, to wit [the armed robbery or

murder of Simmons and Moore], . . .

Two—That the offender committed the offense . . . for

the purpose of receiving money and the automobile

described in the indictment.

21

Three—The offense .. , was outrageously and wantonly

vile, horrible and inhuman, in that [it] . . . involved

the depravity of the mind of the defendant.”

(T. 478, 479.) The jury was told that it could consider

“the facts and circumstances in mitigation and aggrava

tion.” (T. 480.) “Mitigating circumstances” were defined

as

“those which do not constitute a justification of [sic]

excuse for the offense in question, but which, in fair

ness and mercy maybe [sic] considered as a extenuat

ing [sic] or reducing the degree of moral culpability

of punishment [sic].”

(T. 480.) “Aggravating circumstances” were defined as

“those which increase the guilt or innormity [sic] of

the offense or add to its injurious consequences.”

(Ibid.)

The jury recommended a death sentence on each count.

(T. 483-485.) It found true, as to each count, all but the

third “aggravating circumstance.” (Ibid.) The court ac

cordingly imposed four death sentences upon petitioner.

How the Federal Q uestion Was Raised and

D ecided Below

In the Supreme Court of Georgia, petitioner’s Enumera

tion of Error No. 3 asserted that:

“The lower Court erred in submitting to the jury the

issue of punishment by death in that punishment by

death constitutes cruel and inhumane punishment con

trary to the provisions of the Eighth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.”

2 2

On the authority of Coley v. State, 231 Ga. 829, 204 S.E.

2d 612 (1974); House v. State, 232 Ga. 140, 205 S.E.2d 217

(1974) and Eberheart v. State, 232 Ga. 247, 206 S.E.2d 12

(1974), a majority of the Supreme Court of Georgia af

firmed petitioner’s sentences of death for the crime of mur

der, Gregg v. State, 233 Ga. 117, 210 S.E.2d 659 (1974),

one judge dissenting on the ground that the Georgia death

penalty statutes are unconstitutional, id. at 668 (opinion

of Mr. Justice Gunter, concurring and dissenting). The

death sentences imposed for the crime or armed robbery

were vacated on the grounds that the penalty was rarely

imposed for that offense and that the jury improperly

considered the murders as aggravating circumstances for

the robberies after having considered the armed robberies

as aggravating circumstances for the murders. Id. at 667.

An application for rehearing, in which petitioner again

challenged the constitutionality of his death sentences, was

denied. Order dated October 29, 1974.

Summary of Argument

I

Georgia’s 1973 capital punishment statute provides a

bifurcated trial procedure for selecting some convicted

capital offenders to be killed while others live. The statute

has been upheld by the Supreme Court of Georgia over

the objection that it “permits the exercise of a discretion

that extinguishes one man’s life and permits another man

to live, both of whom have committed exactly the same

crime.” Coley v. State, 231 Ga. 829, 204 S.E.2d 612, 620

(opinion of Mr. Justice Gunter, concurring and dissenting).

Experience to date in the administration of the statute

confirms that life sentences and death sentences may be

and are imposed “with no meaningful basis for distinguish-

23

mg” the people who get them. Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S.

238, 313 (1972) (concurring opinion of Mr. Justice White).

Detailed examination of the new statute and its use demon

strates that, far from assuring regularity, it merely per

petuates the arbitrariness condemned in Furman.

The explicit capital sentencing discretion is itself only

one of several mechanisms by which an arbitrary fraction

of death-eligible offenders is selected to be actually put to

death. Prosecutorial charging and plea-bargaining discre

tion, jury discretion to convict of one or another amor

phously distinguished “capital” or non-capital crime, and

gubernatorial discretion to grant or withhold clemency are

all equally uncontrolled and uncontrollable. In its parts and

as a whole, the process is inveterately capricious. To in

flict death through such a process is to inflict unconstitu

tional cruel and unusual punishment within the funda

mental historical concerns of the Eighth Amendment.9

II10

The continuation of arbitrariness in -post-Furman capital

punishment schemes is not mere happenstance. The death

penalty is too cruelly intolerable for our society to apply

it regularly and even-handedly; and it is inherently too

purposeless and irrational to be applied selectively on any

reasoned, non-indivious basis. None of the justifications

advanced to support the cruelty of killing a random smat

tering of prisoners annually survives examination in the

light of the realities of this insensate lottery; and none

9 These concerns are documented in the Brief for Petitioner in

Fowler v. North Carolina, No. 73-7031, at pp. 26-45, and we do not

repeat that documentation in the present brief.

10 This point incorporates by reference the Submissions made in

petitioners’ briefs in Fowler v. North Carolina, No. 73-7031 and

Jurek v. Texas, No. 75-5394.

24

begins, of course, to justify the killing of any particular

human being while his indistinguishable counterparts are

spared in numbers that attest to our collective abhorrence

of what we are doing to an outcast few.

I

Introduction

In 1972, this Court held “that the imposition and carry

ing out of the death penalty” in two Georgia cases “consti

tute [d] cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.” Furman v. Georgia,

supra, 408 U.S. at 239.11 Contemporaneously with that de

cision, the Court summarily vacated death sentences in a

number of other Georgia cases on the authority of Furman

—sentences imposed under the pre-1969 sentencing system

involved in the Furman ease itself,12 under the slightly

different system created by the 1968 Criminal Code of

Georgia,13 and under a bifurcated trial procedure enacted

in 1970.14 The Georgia Supreme Court subsequently rec

ognized that Furman had invalidated all of the State’s

death penalty laws.15 16

11 The companion Georgia case of Jackson v. Georgia was decided

by the same order.

12 Arkwright v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972) ; Miller v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 938 (1972); Walker v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972);

Cummings v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972); Lee v. Georgia, 408

U.S. 936 (1972); Manor v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972); Park v.

Georgia, 408 U.S. 935 (1972); Sullivan v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 935

(1972) ; Thacker v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 936 (1972).

13 Henderson v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 938 (1972).

14 Jackson v. Georgia, 409 U.S. 1122 (1972); Williams v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 936 (1972).

16 See, e.g., Sullivan, et al. v. State, 229 Ga. 731, 194 S.E.2d 411

(1972) ; Mitchell v. Smith, 229 Ga. 781, 194 S.E.2d 414 (1972);

25

The Georgia Legislature reacted in 1973 by enacting a

capital sentencing scheme which requires that one or more

specified “aggravating circumstances” be found as a pre

condition to the imposition of a death sentence.16 Georgia

Laws 1973, p. 159, No. 74 (effective March 28, 1973). Af

ter a jury or a judge renders a verdict or finding of guilty * 16

Massey v. State, 229 Ga. 846, 195 S.E.2d 28 (1972); Grantling v.

State, 229 Ga. 746, 194 S.E.2d 405 (1972); Callahan v. State, 229

Ga. 737, 194 S,E.2d 431 (1972); Sirmans v. State, 229 Ga. 743,

194 S.E.2d 476 (1972) ; McCrary v. State, 229 Ga. 733, 194 S.E.2d

480 (1972) ; Jackson v. State, 230 Ga. 181, 195 S.E.2d 921 (1973) ;

Wilburn v. State, 230 Ga. 675, 198 S.E.2d 857 (1973). In Watson

v. State, 229 Ga. 787,194 S.E.2d 407 (1972), the Court stated flatly

that “the imposition of the death penalty under present Georgia

statutes is unconstitutional.” 194 S.E.2d at 407.

16 No “aggravating circumstances” are required, however, to

support a death sentence for the crimes of treason and aircraft hi

jacking. The death penalty law's enacted in 1973 are set forth at

pages 5-14 supra. Section 26-3102 was modified by the addition of

the italicized passages:

“Capital offenses; jury verdict and sentence. Where, upon

a trial by jury, a person is convicted of an offense which may

be punishable by death, a sentence of death shall not be im

posed unless the jury verdiet includes a finding of at least one

statutory aggravating circumstance and a recommendation

that such sentence be imposed. Where a statutory aggravating

circumstance is found and a recommendation of death is

made, the court shall sentence the defendant to death. Where

a sentence of death is not recommended by the jury, the court

shall sentence the defendant to imprisonment as provided by

law. Unless the jury trying the ease makes a finding of at

least one statutory aggravating circumstance and recommends

the death sentence in its verdict, the court shall not sentence

the defendant to death, provided that no such finding of statu

tory aggravating circumstance shall be necessary in offenses of

treason or aircraft hijacking. The provision of this section

shall not affect a sentence when the case is tried without a jury

or when the judge accepts a plea of guilty.”

Section 26-3102 and 27-2534.1 provided for consideration of aggra

vating and mitigating circumstances, and §27-2534.1 (b) set forth

some of the aggravating circumstances to be considered. Section

27-2537 provided for appellate review of sentences of death. Sec

tion 27-2528 dealt with sentencing following a plea of guilty to an

offense punishable by death. *

26

or after a plea of guilty to the offenses of murder, armed

robbery, rape, kidnapping, treason or aircraft hijacking,17

a pre-sentence hearing is to be conducted before the jury

or judge. At this hearing, “the jury or judge shall hear

additional evidence in extenuation, mitigation and aggra

vation of punishment, including the record of any prior

criminal convictions and pleas of guilty or pleas of nolo

contendere of the defendant, or the absence of such prior

convictions and pleas.” Ga. Laws 1973, p. 162, Act. No, 74.18

The State may present only such evidence in aggravation

as it has made known in advance to the defendant. Ga.

Laws 1973, p. 162, Act. No. 74.

The judge is to consider or to include in his instructions

to the jury “any mitigating circumstances or aggravating

circumstances otherwise authorized by law and . . . statu

tory aggravating circumstances which may he supported

by the evidence.” Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (b). The “stat

utory aggravating circumstances” a re :

“(1) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

kidnapping was committed by a person with a prior

record of conviction for a capital felony, or the of

fense of murder was committed by a person who has

a substantial history of serious assaultive criminal

convictions.

(2) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

kidnapping was committed while the offender was en

gaged in the commission of another capital felony, or

17 These crimes—and the crime of capital perjury, see former Ga.

Code Ann. §26-2401 (1972)—carried a possible death penalty prior

to the 1973 legislation; their definitions were not changed in 1973.

18 The statutory language governing proof of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances at pre-sentence hearings in capital trials

was not changed in 1973. Compare former Ga. Code. Ann. §27-

2534 (1972).

27

aggravated battery, or the offense of murder was

committed while the offender was engaged in the com

mission of burglary or arson in the first degree.

(3) The offender by his act of murder, armed rob

bery, or kidnapping knowingly created a great risk of

death to more than one person in a public place by

means of a weapon or device which would normally

be hazardous to the lives of more than one person.

(4) The offender committed the offense of murder

for himself or another, for the purpose of receiving

money or any other thing of monetary value.

(5) The murder of a judicial officer, former judicial

officer, district attorney or solicitor or former district

attorney or solicitor during or because of the exercise

of his official duty.

(6) The offender caused or directed another to com

mit or committed murder as an agent or employee of

another person.

(7) The offense of murder, rape, armed robbery, or

kidnapping was outrageously or wantonly vile, hor

rible or inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity

of mind, or an aggravated battery to the victim.

(8) The offense of murder was committed against

any peace officer, corrections employee or fireman

while engaged in the performance of his official duties.

(9) The offense of murder was committed by a per

son in, or who has escaped from, the lawful custody of

a peace officer or place of lawful confinement.

(10 The murder was committed for the purpose of

avoiding, interfering with, or preventing a lawful

arrest or custody in a place of lawful confinement, of

himself or another.”

28

Ibid. Additional “aggravating circumstances otherwise au

thorized by law” are not identified. “Mitigating circum

stances” are not enumerated or defined.19

The jury m ay—but need not—impose a death sentence

when it finds beyond a reasonable doubt one “statutory

aggravating circumstance.” Ga. Laws 1973, p. 162, Act. No.

74. For to condemn a defendant, it must also make a “rec

ommendation of death.” 20 Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1(e).

See Ga. Code Ann. §26-3102.21

Provision is made for the filing of a standardized form

“report” by the trial judge in capital cases where the death

penalty is imposed and for direct automatic appeal to the

Georgia Supreme Court. Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537. General

guidelines for review by that court are provided,22 and the

court is empowered to affirm the death sentence or to set it

19 The Act does, however, provide that evidence of the absence

of prior criminal convictions or pleas may be heard at the penalty

trial. Ga. Laws 1973, p. 162, Act No. 74.

20 See pages 33-34, infra.

21 See note 16, supra.

22 The Court is directed to consider “the punishment as well as

any errors enumerated by way of appeal” in a case where a death

sentence has been imposed, and to determine:

“ (1) Whether the sentence of death was imposed under the

influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor,

and

(2) Whether, in cases other than treason or aircraft hijack

ing, the evidence supports the jury’s or judge’s finding of a

statutory aggravating circumstance as enumerated in Code sec

tion 27-2534.1 (b), and

(3) Whether the sentence of death is excessive or dispro

portionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering

both the crime and the defendant.”

Ga. Code Ann, §27-2537 (c). If the court affirms a death sentence,

it “shall include in its decision a reference to those similar cases

which it took into consideration.” Ga. Code Ann. §27-2537{e).

29

aside and remand the case for resentencing. Ibid. Execu

tive discretion to grant or deny clemency in cases where a

death sentence has been imposed remains unregulated.

In the following Part II we will establish, through an

analysis of the unquestionably discretionary procedures

by which Georgia capital defendants are still prosecuted

and sentenced, that the constitutional infirmities condemned

in Furman v. Georgia remain. Cf. Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S.

268, 275 (1938). In Part III we will address the question

whether the execution of a human being who has been con

demned through such procedures can be thought consistent

with Eighth Amendment standards of decency.

II

The Arbitrary Infliction of Death

A. At the Pre-Sentence Hearing.

1. Georgia’s 1973 Death Penalty Legislation Is Explicitly

Discretionary.

We start with the observation that Georgia’s post-Fur

man capital sentencing procedure remains avowedly dis

cretionary. In Coley v. State, 231 Ga. 829, 204 S.E.2d 612

(1974), the Supreme Court of Georgia addressed the consti

tutionality of the 1973 death penalty laws, and said:

“The essential question is not whether our new death

statute permits the use of some discretion, because ad

mittedly it does, but, rather, whether the discretion to

be exercised is controlled by clear and objective stan

dards so as to produce non-discriminatory application.

After all, some discretion is inherent in any system of

justice, from arrest to final review.”

Id. at 615. The Court concluded that “the system of dis

pensation of the death penalty provided by the statute does

30

not offend the principles of decision of the U.S. Supreme

Court in Furman and Ja ckso n id . at 616, because:

“ [f]irst, the new statute substantially narrows and

guides the discretion of the sentencing authority to

impose the death penalty and allows it only for the

most outrageous crimes and those offenses against

persons who place themselves in great danger as pub

lic servants. In addition, the new statute provides

for automatic and swift appellate review to insure

that the death penalty will not be carried out unless

the evidence supports the finding of one of the ser

ious crimes specified in the statute. The statute also

requires comparative sentencing so that if the death

penalty is only rarely imposed for an act or it is

substantially out of line with sentences imposed for

other acts it will be set aside as excessive. And,

finally, the statute requires this court to make cer

tain the record does not indicate that arbitrariness

or discrimination was used in the imposition of the

death sentence.”

The following sections demonstrate, however, that sen

tencing discretion is neither confined by the provisions of

the new statute nor regularized by the process of appel

late re-evaluation.

2. The Consideration of Aggravating and Mitigating Cir

cumstances Does Not Control Arbitrariness in the

Georgia Capital Sentencing Process.

The process of considering “aggravating” and “mitigat

ing” circumstances does not—and was not intended to—

confine the unfettered power of the sentencer to condemn

or spare any capital defendant. This is clear for several

reasons.

31

a. The failure to identify circumstances under which a

death penalty is precluded.

The statute does not preclude a death sentence in any

potentially capital case. True, a statutory “aggravating

circumstance” is legally required to be found before a

defendant can be sentenced to die; and it is doubtless

also true that most of the enumerated aggravating cir

cumstances—despite their multiplication,23 imprecision24

and breadth25—have some limits. But the reach of sub

23 B.g. Ga. Code Ann. §27-2534.1 (b) (1) (the defendant had “a

prior record of conviction for a capital felony . . . or a substantial

history of serious assaultive criminal convictions”) ; (2) (“the of

fender was engaged in the commission of another capital felony,

or aggravated battery, or . . . burglary or arson in the first de

gree”) ; (3) (“The offender . . . knowingly created a great risk of

death to more than one person in a public place by means of a

weapon or device which would normally be hazardous to the lives

of more than one person.”) ; (4) (the murder was committed “for

the purpose of receiving . . . any . . . thing of monetary value.”) ;

(6) (“The offender caused or directed another to commit murder

or committed murder as an agent or employee of another person.”).

24 See pages 35-36, infra.

25 Consider, for example, Ga. Code Ann. §27,2534.1(b) (4) which

makes it an aggravating circumstance that murder is committed