County of Los Angeles v. Davis Hiring Quota Case Dismissed

Press Release

March 27, 1979

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 7. County of Los Angeles v. Davis Hiring Quota Case Dismissed, 1979. 7759c69a-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4a46e39-6ab5-47b4-9879-fd0ec38d6b12/county-of-los-angeles-v-davis-hiring-quota-case-dismissed. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

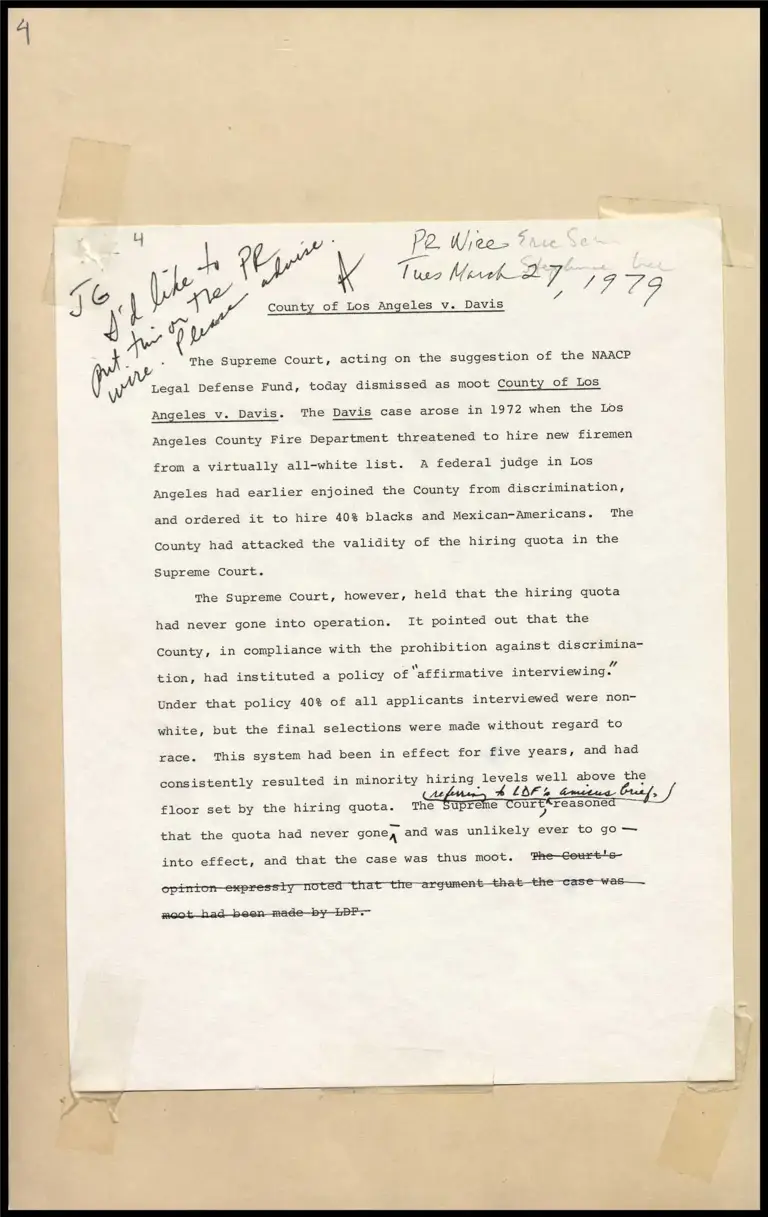

County of Los Angeles v. Davis

=, 9-79

ack Supreme Court, acting on the suggestion of the NAACP

ig Defense Fund, today dismissed as moot County of Los

Angeles v. Davis. The Davis case arose in 1972 when the Los

Angeles County Fire Department threatened to hire new firemen

from a virtually all-white list. A federal judge in Los

Angeles had earlier enjoined the County from discrimination,

and ordered it to hire 40% blacks and Mexican-Americans. The

County had attacked the validity of the hiring quota in the

Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court, however, held that the hiring quota

had never gone into operation. It pointed out that the

County, in compliance with the prohibition against discrimina-

tion, had instituted a policy of “affirmative interviewing.”

Under that policy 40% of all applicants interviewed were non-

white, but the final selections were made without regard to

race. This system had been in effect for five years, and had

consistently resulted in minority hiring | levels well above the

a 4 LaF % dmetwa Curl, f

floor set by the hiring quota. The Supreme OuEe, reasone =

that the quota had never gone, and was unlikely ever to go —

into effect, and that the case was thus moot. Pke—Courtts—

opirion—expressiy mmoted that the argument thatthe case was——

moot—hadbeen-—made—by_bBF.-

Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal De-

fense Fund, expressed satisfaction with the Court's decision.

"The lower courts have generally recognized the need to impose

hiring quotas to remedy employment discrimination, and today's

decision leaves that body of law intact." In addition,

Mr. Greenberg noted that the majority of the Court assumed

Los Angeles would continue its “affirmative interviewing policy

even in the absence of a court order, and that no member of

the Court expressed any reservations about the legality of

such a voluntary program. "The Supreme Court appears to have

given a green light for affirmative interviewing, which as a

result may increase in importance as a method of ending the

effects of past discrimination."

"There has been no suggestion by any of the parties, nor

is there any reason to believe, that petitioners would signifi-

cantly alter their present hiring practices if the injunction

were disSolved. See also Brief Amicus Curiae for the N.A.A.C.P.

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., at 7. A fortiori,

there is no reason to believe that petitioners would replace

their present hiring procedures with procedures that they re-

garded as unsatisfactory even before the commencement of this

litigation. Under these circumstances we believe that this

aspect of the case has ‘lost its character as a present, live

controversy of the kind that must exist if (Ene Court is]

to avoid advisory opinions on abstract propositions of law.'

Hall v. Beals, 396 U.S. 45, 48 (1969)."

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES ET AL. v. DAVIS ET AL.

Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit

No. 77-1553. Argued December 5, 1978 -- Decided March 27, 1979