Background on School Integration Cases in Supreme Court - Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg and Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County

Press Release

October 6, 1970

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Background on School Integration Cases in Supreme Court - Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg and Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 1970. 4c329b40-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4b2b711-4e39-4696-89e5-d960d1418d44/background-on-school-integration-cases-in-supreme-court-swann-v-charlotte-mecklenburg-and-davis-v-board-of-school-commissioners-of-mobile-county. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

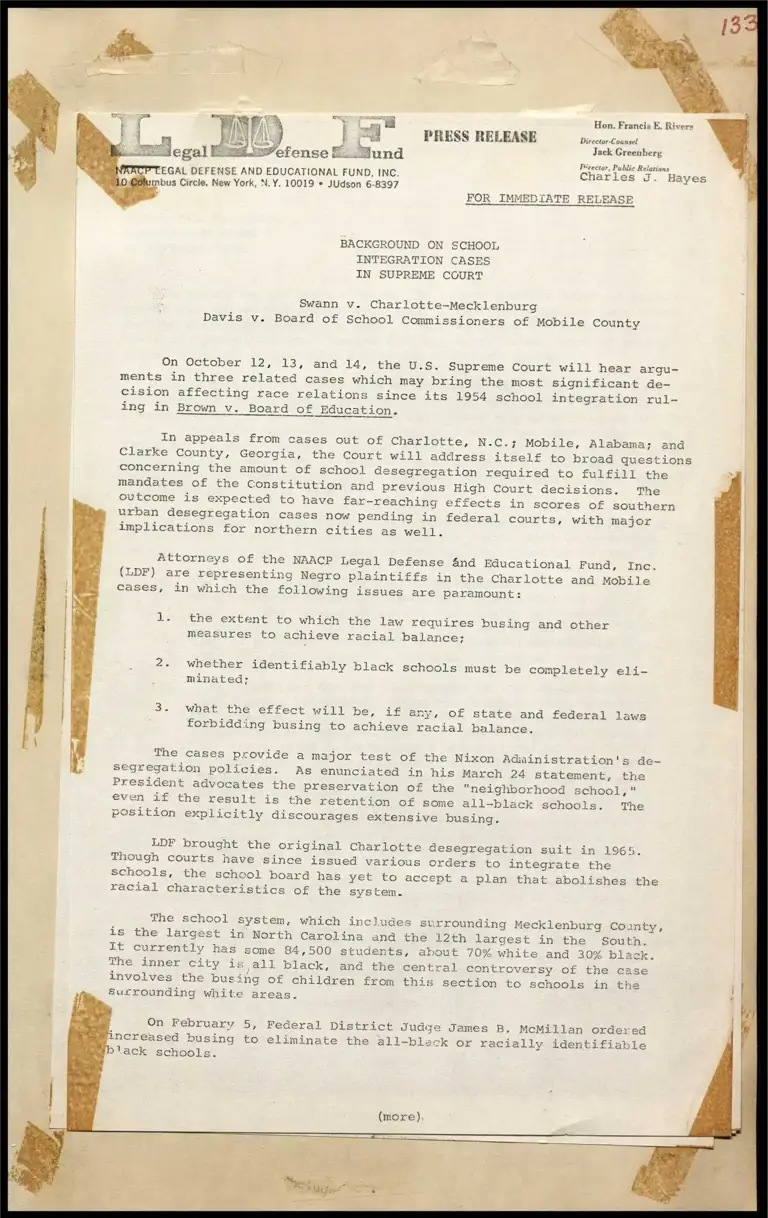

i Hon. Francis E. Rivers

ppt PRESS RELEASE Director Counsel

‘efense H.Sund p ——

rector, Public Relations EGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. Charles J. Hayes

nbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 © JUdson 6-8397

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

BACKGROUND ON SCHOOL

INTEGRATION CASES

IN SUPREME COURT

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County

On October 12, 13, and 14, the u.s. Supreme Court will hear argu-

ments in three related cases which may bring the most significant de-

cision affecting race relations since its 1954 school integration rul-

ing in Brown v. Board of Education.

In appeals from cases out of Charlotte, N.C.7 Mobile, Alabama; and

Clarke County, Georgia, the Court will address itself to broad questions

concerning the amount of school desegregation required to fulfill the

mandates of the Constitution and previous High Court decisions. The outcome is expected to have far-reaching effects in scores of southern urban desegregation cases now pending in federal courts, with major implications for northern cities as well.

Attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense 4nd Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) are representing Negro plaintiffs in the Charlotte and Mobile cases, in which the following issues are paramount:

1. the extent to which the law requires busing and other

measures to achieve racial balance;

whether identifiably black schools must be completely eli-

minated;

what the effect will be, if any, Of state and federal laws

forbidding busing to achieve racial balance.

The cases provide a major test of the Nixon Adiainistration's de- segregation policies. As enunciated in his March 24 statement, the President advocates the preservation of the "neighborhood school," even if the result is the retention of some all-black schools. The position explicitly discourages extensive busing.

LDF brought the original Charlotte desegregation suit in 1965. Though courts have since issued various orders to integrate the

schools, the school board has yet to accept a plan that abolishes the racial characteristics of the system.

The school system, which includ surrounding Mecklenburg Coa ty, is the larg in North Carolina and the 12th largest in the South. It currently has some 84,500 students, about 70% white and 30% black.

The inner city is all black, and the central controversy of the case

involves the bus ng of children from this section to schools in the

Surrounding white areas.

On February 5, Federal District Judge James B. McMillan ordered increased busing to eliminate the all-black or racially identifiable

black schools.

(more)

BACKGROUND ON SCHOOL

INTEGRATION CASES

IN SUPREME COURT -2- October 6, 1970

On appeal by the school board, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

upheld the junior and senior high portions of the order but sent that

portion governing elementary schools back to Judge McMillan to apply a

“rule of reasonableness," saying that not every school must be inte-

grated in order to meet the demand for a unitary system.

Judge McMillan answered this challenge by asserting that “it is

the constitutional rights that should prevail against the cry of un-

reasonableness." The Supreme Court reinstated his order pending its re-

view. (This plan has been implemented with relative success and calm

since the delayed opening of schools three weeks ago, despite prior

school .board claims that it lacked buses or money for transporting stu-

dents. The average length of bus ride has actually decreased by more ue

than half that of last year.)

LDF cooperating attorney Julius LeVonne Chambers of Charlotte, one

of the foremost civil rights lawyers in the South, will include the

following points in his argument before the High Court on October 12:

I. The school system is racially segregated as the result

of government action in school and residential segre-

gation. The "neighborhood school" policy is untenable

in that official action has created segregated resi-

dential patterns and school boards have traditionally

drawn attendance zones to maintain segregated schools.

II. Judge McMillan d not (as charged by the school board

and Justice Department) abuse his discretionary authority

~by ordering the plan chosen; it is in conformity with re-

quirements of previous High Court decisions: (a) the plan

set the goal of establishing a unitary system, and (b) it

offered substantial evidence (not challenged by the Court

of Appeals) supporting the feasibility and effectiveness

of the plan in achieving that goal.

III. in its vagueness and ambiguity, the Fourth Circuit's

"reasonableness" rule threatens to become a device to

reduce the extent and slow the pace of desegregation.

The National Education Association has submitted an amicus brief

to the Supreme Court in support of the LDF position in this case.

A col eral case growing out cf Charlotte's school controversy

arose from tempts by the school beard to block integration by invok-

ing North Carolina's anti-busing law, which forbids busing of school

children w ut explicit consent from tt parents. The 1001 board

is asking the Supreme Court to reverse a district court decision de-

claring the law to be unconstitutional.

sc

(more)

BACKGROUND ON SCHOOL

INTEGRATION CASES

IN SUPREME COURT =3- October 6, 1970

James M. Nabrit III, LDF associate counsel, will present arguments

on October 12 supporting the lower court's opinion. (In New York State,

a three-judge federal district court recently sustained LDF's attack

on the constitutionality of that state's anti-busing law. -Although LDF

attorneys believe the decision will be persuasive in southern courts,

only a Supreme Court order to that effect would be binding and relieve

the LDF of protracted litigation in those states that have similar laws.)

For seven years the case of Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County has been in the federal courts. On October 12 the

Supreme Court will be asked by LDF attorneys for Birdie Mae Davis to deter-

mine once and for all that the dual school system is unconstitutional.

A decision such as this could well mean the end to all the lengthy and

unnecessary school litigation since Brown v. Board of Education 1954.

Mobile has a combined rural and metropolitan school system serving

the whole of Mobile County. It is the largest school system in Alabama.

During the 1969-70 school year, 91 schools served 73,504 students, of

whom 42,620, or 58%, were white and 30,884 or 42% were black.

Within the metropolitan area, 65 schools served 54,913 students

during 1969-70, of whom .27,769 or 50.5% were white and 27,144, or

49.5% were black.

The Davis case is important because for 5 years the school board

has used racially defined attendance zones, increasing or decreasing

the capacity of schools or the grades served by schools to commensu—

rately increase or decrease the areas served by schools in accordance

with the racial character of residential patterns, and closing or con-

structing schools to serve predetermined racial groups to maintain

the dual school system. With the Federal government's entrance into

the case the board was forced to prepare plans for desegregation and

have them approved by H.E.W. and the District Court. But the school

board never developed a workable plan and never fully cooperated with

H.E.W., the District Court, or the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit.

The LDF obtained Supreme Court review of this case complaining

that the desegregation plan now in effect in Mobile leaves about half

of the black elementary school children in metropolitan Mobile in

schools which are all black. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit ordered the plan into effect on the recommendation of the

U.S. Department of Justice, which has participated in the case since

1968. The suit was begun on behalf of ro pupils and parents in 1963

by the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

(more)

~

BACKGROUND ON SCHOOL

INTEGRATION CASES

IN SUPREME COURT -4- October 6, 1970

The LDF argues that its proposed principle requiring the elimi-

nation of all identifiable "black" schools in dual systems is simple

enough to bring an end to protracted litigation, will promote unifor-

mity of desegregation efforts and nevertheless allows some flexibility

for local problems and extreme cases. The brief underlines the impor-

tance of the cases saying:

"The decision of the Court in these cases

may decide whether the promise of Bro

(the 1954 desegregation decision) will be

kept for thousands upon thousands of black

children. That promise is broken by the

current approach of the Fifth Circuit which

leaves segregation intact in the main insti-

tutions of dual system -- the all black

schools."

The brief argues that the only excuse.from this requirement is

cases of “absolute unworkability" of desegregation plans, as for ex-

ample where blacks are a very high percent of the total school popu-

lation and perhaps in other extreme circumstances of geographical and

demographic flukes.

In the Clarke County, Georgia case, which includes the city of

Athens, lawyers for black parents students will ask the High Court

erse the Georgia State Supreme Court's ruling that prohibits

busing of children to achieve racial balance in the schools.