Revised Complaint

Public Court Documents

November 23, 1994

33 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Revised Complaint, 1994. 91d7bbec-a246-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4bec03e-539e-4e37-879d-1e90a1e2abac/revised-complaint. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

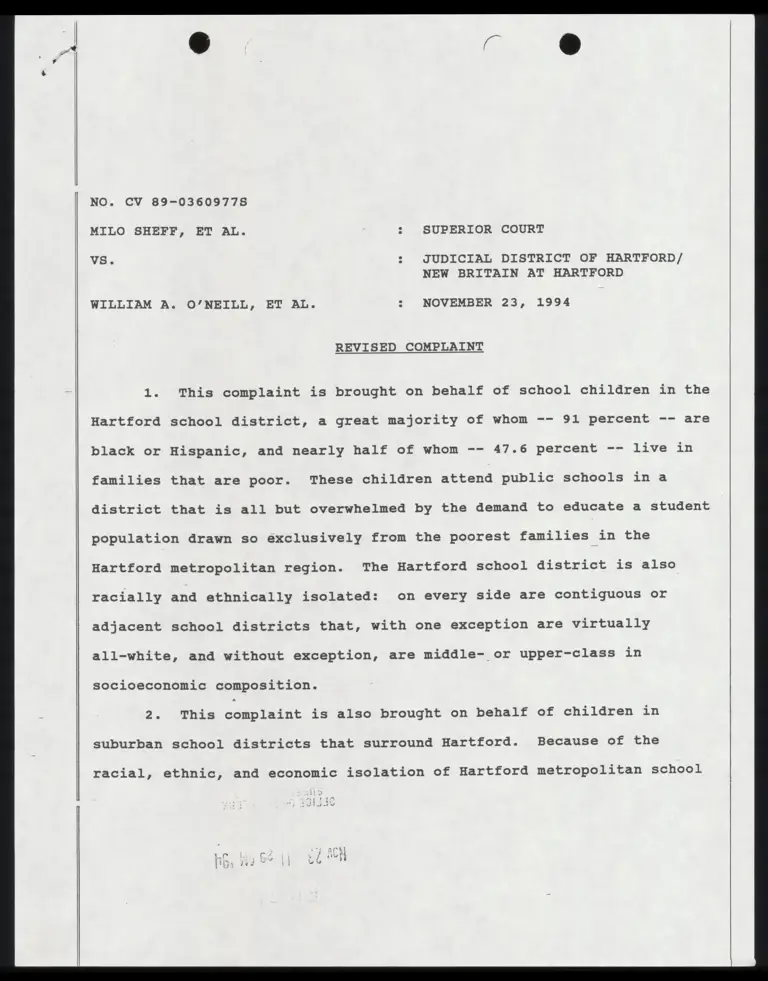

NO. CV 89-03609778

MILO SHEFF, ET AL. SUPERIOR COURT

VS.

JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF HARTFORD/

NEW BRITAIN AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O’/NEILL, ET AL. NOVEMBER 23, 1994

REVISED COMPLAINT

1. This complaint is brought on behalf of school children in the

Hartford school district, a great majority of whom -- 91 percent -- are

black or Hispanic, and nearly half of whom -- 47.6 percent -- live in

families that are poor. These children attend public schools in a

district that is all but overwhelmed by the demand to educate a student

population drawn so exclusively from the poorest families in the

Hartford metropolitan region. The Hartford school district is also

racially and ethnically isolated: on every side are contiguous or

adjacent school districts that, with one exception are virtually

all-white, and without exception, are middle- or upper-class in

socioeconomic composition.

2. This complaint is also brought on behalf of children in

suburban school districts that surround Hartford. Because of the

racial, ethnic, and economic isolation of Hartford metropolitan school

districts, these plaintiffs are deprived of the opportunity to

associate with, and learn from, the minority children attending school

with the Hartford school district. 3. The educational achievement of school children educated in

‘lthe Hartford school district is not, as a whole, nearly as Feat as

that of students educated in the surrounding communities. These

disparities in achievement are not the result of native inability:

poor and minority children have the potential to become well-educated,

as do any other children. Yet the State of Connecticut, by tolerating

school aimtvicts sharply separated along racial, ethnic, and economic

lines, has deprived the plaintiffs and other Hartford children of their

rights to an equal educational opportunity, and to a minimally adequate

education -- rights to which they are entitled under the Connecticut

cohshi bution and Connecticut statutes.

4. The defendants and their predecessors have long been aware of

the educational necessity for racial, ethnic, and economic integration

in the public schools. The defendants have recognized the lasting harm

inflicted on poor and rion ty students by Lhe maintenance of isolated

urban school districts. Yet, despite their knowledge, despite their

constitutional and statutory obligations, despite sufficient legal

tools to remedy the problem, the defendants have failed to act

effectively to provide equal educational opportunity to plaintiffs and

other Hartford schoolchildren.

5. Equal educational opportunity, however, is not a matter of

sovereign grace, to be given or withheld at the discretion of the

Legislative or the Executive branch. Under Connecticut’/s constitution,

ijt is a solemn pledge, 2 covenant renewed in every generation between

he people of the State and their children. The Connecticut

Constitution assures to every Connecticut child, in every city and

town, an equal Sppertinliy to education as the surest means by which to

shape his or her own future. This lawsuit is brought to secure this

basic constitutional right for plaintiffs and all Connecticut

schoolchildren.

II. PARTIES

A. PLAINTIFFS

6. ©Plaintiff Milo Sheff is a fourteen-year-old black child, Ee

resides in the city of Hartford with his mother, Elizabeth Sheff, who

brings this action as his next friend. Ee 1s enrolled in the eighth

grade at Quirk Middle School.

7. Plaintiff wildaliz Bermudez is a ten-year-old Puerto Rican

child. she resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Pedro and

carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next friend. She

is enrolled in the fifth grade at Kennelly School.

8. Plaintiff Pedro Bermudez is an eight-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents, Pedro and

Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the third grade at Kennelly School.

9. Plaintiff Eva Bermudez is a six-year-old Puerto Rican child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Pedro and Carmen

Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in Kindergarten at Kennelly School.

10. Plaintiff Oskar M. veleudeZ is a ten-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the Town of Glastonbury with his parents, Oscar

and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the fifth grade at Naubuc School.

11. Plaintiff Waleska Melendez is a fourteen-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She resides in the Town of Glastonbury with her parents,

Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as her next friend.

She is a freshman at Glastonbury High School.

12. Plaintiff Martin Hamilton is a thirteen-year-old black

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his mother, Virginia

Pertillar, who brings this action as his next friend. He is enrolled

in the seventh grade at Quick Middle School.

13. [Withdrawn.]

14. Plaintiff Janelle Hughley is a 2-year-old black child. She

resides in the city of Hartford with her mother, Jewell Hughley, who

brings this action as her next friend.

15. Plaintiff Neiima Best is a fifteen-year-old black child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Denise Best, who

brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled as a Scotus

at Northwest Catholic High School in West Hartford.

16. Plaintiff Lisa Laboy is an eleven—year—-old Puerto Rican

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Adria

Laboy, who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in

the fifth grade at Burr School. z

17. Plaintiff David William Harrington is a thirteen-year-old

white child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents,

|Raren and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend. He

is enrolled in the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School.

18. Plaintiff Michael Joseph Harrington is a ten-year-old white

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents, Karen and

Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the fifth grade at Noah Webster Elementary School.

19. Plaintiff Rachel Leach is a ten-year-old white child. She

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents, Eugene Leach and

Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the fifth grade at the Whiting Lane School.

20. Plaintiff Joseph Leach is a nine-year-old white child. He

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents, Eugene Leach and

Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the third grade at the Whiting Lane School.

21. Plaintiff Erica Connolly is a nine-year-old white child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Carol Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the fourth grade at Dwight School.

22. Plaintiff Tasha Connolly is a six-year-old white child. She

resides in the city of Hartford with her parents, Carol Vinick and Tom

Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in

the first grade at Dwight School.

22a. Michael Perez is a fifteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. He

resides in the city of Hartford with his father, Danny Perez, who

brings this action as his next friend. He is enzoliad as a sophomore

at Hartford public High School.

22b. Dawn Perez is a thirteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. She

resides in the City of Hartford with her father, Danny Perez, who

brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in the eighth

grade at Quirk Middle School.

23. Among the plaintiffs are five black children, seven Puerto

bican children and six white children. At least one of the children

lives in families whose jncome falls below the ofzlcial poverty line;

Five have limited proficiency in English; six live in single-parent

families. B. DEFENDANTS

24. Defendant William 0/Neill or his successor is the Governor

~f the State of Connecticut. pursuant to C.G.S. §10-1 and 10-2, with

the advice and consent of the General Assembly, he is responsible for

hopolnbing the members of the State Board of Education and, pursuant to

C.G.S. §10-4(b), is responsible for receiving a detailed statement of

the activities of the board and an account of the condition of the

public schools and such other information as will assess the true

condition, progress and needs of public education.

25. Defendant State Board of Education of the state of

Connecticut (hereafter nthe State Board!" or nthe State Board of

Education’) is charged with the overall supervision and control of

educational interest of the State, jncluding ‘elementary and secondary

education, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4.

26. Defendants Abraham Glassman, A. Walter Esdaile, Warren J.

Foley, Rita Eendel, John Mannix, and Julia Rankin, or their succesSOrLS

‘are members of the State Board of Education of the state of

‘connecticut. Pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4, they have general supervision

and control of the educational interest of the State.

=

-T -

27. Defendant Gerald N. Tirozzi or his successor is the

Commissioner of the Education of the State of Connecticut and a member

of the State Board of Education. Pursuant to C.G:S. §§10-2 and 10-3a,

he is responsible for carrying out the mandates of the Board, and is

also director of the Department of Education (hereafter '"the state

Department of Education' or "the State Department").

28. Defendant Francisco L. Borges or his successor is Treasurer

of the State of Connecticut. Pursuant to Article Fourth, §22 of the

Connecticut constitution, he is responsible for the disbursements of

all monies by the State. He is also the custodian of certain

leducational funds of the Connecticut State Board of Education, pursuant

ko CuGeS. §10-11l.

29. Defendant J. Edward Caldwell or his successor is the

Comptroller of the State of Connecticut. Pursuant to Article Fourth,

§24 of the Connecticut Constitution and C.G.S. §3-112, he is

responsible for adjusting and settling all public accounts and demands.

11x

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. 2A SEPARATE EDUCATION

30. School children in public schools throughout the State of

Connecticut, including the city of Hartford and its adjacent suburban

communities, are largely segregated by race and ethnic origin.

31. Although blacks comprise only 12.1% of Connecticut’s

school-age population, Hispanics only 8.5%, and children in families

below the United States Department of Agriculture’s official "poverty

line" only 9.7% in 1986, these groups comprised, as of 1987-88, 44.9%,

44.9%, and 51.4% respectively of the school-age population of the

Hartford school district. The percentage of black and Hispanic

(hereafter '"minority") students enrolled in the Hartford City schools

has been jrcrsasing since 1981 at an average annual rate of 1.5%.

32. The only other school district in the Hartford metropolitan

larea with a significant proportion of minority students is Bloomfield,

which has a minority student population of 69.9%.

33. The school-age populations in all other suburban school

districts immediately adjacent and contiguous to the Hartford school

district, (hereafter "the suburban districts"), by contrast, are

overwhelmingly white. 2An analysis of the 1987-88 figures for Hartford,

Bloomfield, and each of the suburban districts (excluding Burlington,

which has a joint school program with districts outside the Hartford

metropolitan area) (reveals the following comparisons by race and ethnic

origin:

Total School Pop. % Minority

Hartford 25,058 90.5

Bloomfield 2,555 69.9

J Je Je de Jo Je Jk Je de de dk ke kk kk

Avon 2,068 3.8

Canton 1,189 3.2

East Granby 666 2.3

East Hartford 5,905 20.6

East Windsor 3,267 8.5

Ellington 1,855 2.3

Farmington 2,608 7.7

Glastonbury 4,463 - 5.4

Granby 1,528 3.5

Manchester . 7,084 11.1

Newington 3,801 6.4

Rocky Hill 1,807 5.9

Simsbury 4,039 3 6.5

South Windsor 3,648 9.3

Suffield di 2,772 4.0

Vernon : 4,457 6.4

West Hartford : 7,424 . 15.7

Wethersfield 2,997 3.3

Windsor 4,235 : 30.8

4.0

Windsor Locks 1,642

34. Similar significant racial and ethnic disparities

characterize the professional teaching and administrative staffs of

Hartford and the suburban districts, as the following 1986-87

comparisons reveal:

Staff % Minority

Hartford 2,044 33.2%

Bloomfield 264 : 13.6%

de Je Je Je Je dk de de dk J de Kk Kk de de ok

Avon 179 1.31%

Canton 108 0.0%

East Granby 57 1.8%

Fast Hartford 517 0.6%

Fast Windsor 102 4.9%

Ellington 164 0.6%

Farmington 201 1.0%

Glastonbury 344 2.0%

Granby 131 0.8%

Manchester 537 1.7%

Newington 310 1.0%

Rocky Hill . 154 0.6%

Simsbury 317 oe 1.9%

South Windsor 294 1.4% 5

Suffield 143 0.7%

Vernon 366 0.5%

West Hartford 605 3.5%

Wethersfield 263 2.1%

Windsor 331 5.4%

Windsor Locks 140 0.0%

B. AN UNEQUAL EDUCATION

35. Hartford schools contain a far greater proportion of

students, at all levels, from backgrounds that put them nat risk of

lower educational achievement. The cumulative responsibility for

educating this high proportion of at-risk students places the Hartford

public schools at a severe educational disadvantage in comparison with

the suburban schools.

36. All children, including those deemed at risk of lower

education achievement, have the capacity to learn if given a suitable

education. Yet because the Hartford public schools have an

extraordinary proportion of at-risk students among their student

populations, they operate at a severe educational disadvantage in

addressing the educational needs of all students -- not only those who

are at risk, but those who are not. The sheer proportion of at-risk

students imposes enormous educational burdens on the individual

students, teachers, classrooms, and on the schools within the City of

Hartford. These burdens have deprived both the at-risk children and

all other Hartford schoolchildren of their right to an equal

educational opportunity.

37. An analysis of 1987-88 data from the Hartford and suburban

districts, employing widely accepted indices for identifying at-risk

students =-- including: (i) whether a child’s family receives benefits

under the Federal Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, (a

measure closely correlated with family poverty): (ii) whether a child

has limited english proficiency (hereafter NLEPY) ; or (iii) whether a

child is from a single-parent family, reveals the following overall

comparisons:

% on AFDC LEP Sql. Par. Fam.¥*

Hartford 47.6 40.9 51.0

Avon 0.1 1.9 6.8

Bloomfield 4.1 3.1 12.0

Canton : 1.2 1.6 8.8

East Granby 1.1 0.2 10.1

East Hartford 7.2 9.8 19.7

o\

° 0 ol

55

d Q o\

° on

) = d

o\

? 0n

0 j=

rd

ol H : *

Ww

.

N un

Fast Windsor

Ellington

Farmington

Glastonbury

Granby

Manchester

Newington

Rocky Hill

Simsbury

South Windsor

suffield

Vernon

west Hartford

wethersfield

windsor

windsor Locks

Oo

.

N

W

®

:

:

6

&

4

n

N

u

o

L]

LJ S

W

H

P

N

u

n

O

¢«

©

0

°

[-

LJ

A

N

O

A

V

U

R

E

B

E

O

O

R

U

O

L

O

O

O

N

W

O

N

O

®

O

N

pa

P

P

W

W

M

O

W

W

E

R

E

R

A

E

U

L

N

W

L

O

_"

2,

N

N

O

N

O

N

K

P

»

W

N

W

N

O

a

n

O

O

O

O

K

H

W

O

K

H

O

o

¢

W

U

L

H

E

O

N

O

®

N

O

G

O

N

»

O

R

a

V

O

o

O

W

o

m

n

o

n

N

W

w

w

®

»

4

P

P

* (Community-wide Data)

38. Faced with these severe education burdens, schools in the

Hartford school district have been unable to provide educational

opportunities that are substantially equal to those received by

schoolchildren in the suburban districts.

39. As a result, the overall achievement of schoolchildren in

the Hartford school district -- assessed by virtually any measure of

educational performance —-— is substantially below that of

schoolchildren in the suburban districts.

-13-

40. One principal measure of student achievement in Connecticut

is the Statewide Mastery Test program. Mastery tests, administered to

every fourth, sixth, and eighth grade student, are devised by the State

Department of Education to measure whether children have learned those

skills deemed essential by Connecticut educators at each grade level. 41. The State Department of Education has designated both a

"mastery Benchmark" —-— which indicates a level of performance

reflecting mastery of all grade-level skills -- and a "remedial

benchmark!" —- which indicates mastery of nessential grade-level

skills.n See C.G.S. §10-14n (b)=-(c) .

42. Hartford schoolchildren, on average, perform at levels

significantly below suburban schoolchildren on statewide Mastery

Tests. For example, in 1988, 34% (or 1-in-3) of all suburban sixth

graders scored at or above the mESEeTY benchmark" for reading, yet

only 4% (or 1-in-25) of Hartford schoolchildren met that standard.

While 74% of all suburban sixth graders exceed the remedial benchmark

on the test of reading skill, no more than 41% of Hartford

schoolchildren meet this test of "essential grade-level skills." In

other words, fifty-nine percent of Hartford sixth graders are reading

below the State remedial level.

-14- *)

43. An analysis of student reading scores on the 1988 Mastery

Test reveal the following comparisons:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk.

RBartford 70 59 57

| de J Je de de de de de de :

Avon 9 6 : 3

"Bloomfield 25 24 16

Canton 8 10 2

East Granby 12 4 5

East Hartford 38 30 36

East Windsor 17 10 15

(Ellington 25 14 13

Farmington 12 3 10

Glastonbury 15 13 11

‘Granby 19 14 17

Manchester 22 15 17

Newington 8 15 32

Rocky Hill 13 - 10 24

Simsbury 9 5 3

South Windsor a 13 16

Suffield 20 10 15

Vernon 15 18 20

West Hartford 19 1s 11

Wethersfield 18 32 14

Windsor 26 17 23

Windsor Locks 25 16 17

44. An analysis of student mathematics scores on the 1988 Mastery

Test reveals the following comparisons:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk.

Hartford 41 42 57

J J J J J Kk Kk Kk Jk k

Avon 4 - 3

Bloomfield 6 21 18

Canton 3 8 5

East Granby 10 7 6

East Hartford 14 19 19

East Windsor J 2 S 19

Ellington 10 8 4

Farmington 3 5 3

Glastonbury 6 8 2

Granby 3 12 11

Manchester 8 1s 11

Newington 3 6 7

Rocky Hill 3 4 14

Simsbury 5 5 3

South Windsor . 8 10 8

Suffield pK 33 8

Vernon 8 9 i2

west Hartford 8 9 7

Wethersfield 6 8 6

Windsor - 12 33 26

Windsor Locks 2 7 14

45. Measured by the State’s own educational standards, then, a

majority of Hartford schoolchildren are not currently receiving even a

"minimally adequate education."

46. Other measures of education achievement reveal the same

pattern of disparities. The suburban schools rank far ahead of the

Hartford schools when measured by: the percentage of students who

remain in school to receive a high school diploma versus the percentage

i

\

-16- :

lof students who drop out; the percentage of high school graduates who

enter four-year colleges; the percentage of graduates who enter any

program of higher education; or the percentage of graduates who obtain

full-time employment within nine months of completing their schooling.

47 These disparities in educational achievement between the

Hartford and suburban school districts are the result of the

education-related policies pursued and/or accepted by the defendants,

including the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic isolation of the

Hartford and suburban school districts. These factors have already

adversely affected many of the plaintiffs in this action, and will, in

the future, inevitably and adversely affect the education of others.

48. The racial, ethnic, and economic Sesragaiiion of the Hartford

and suburban districts necessarily limits, not only the equal

educational opportunities of the plaintiffs, but their potential

employment contacts as well, since a large percentage of all employment

growth in the Hartford metropolitan region is occurring in the suburban

districts, and suburban students have a statistically higher rate of

success in obtaining employment with many Hartford-area businesses.

49. Public school integration of children in the Hartford

metropolitan region by race, ethnicity, and ptononic status would

significantly improve the educational achievement of poor and minority

ee -17-

children, without diminution of the education afforded their majority

schoolmates. Indeed, white students WOuld be provided thereby with the

positive benefits of close associations during their formative years

with blacks, Hispanics and poor children who will make up over 30% of

Connecticut’s population by the year 2000.

C. THE STATE’S LONGSTANDING KNOWLEDGE OF THESE INEQUITIES

50. For well over two decades, the tate of Connecticut, through

its defendant O’Neill, defendant State Board of Education, defendant

Tirozzi, and their predecessors and Successors, have been aware of:

(i) the separate and unequal pattern of public school districts in the

State of Connecticut and the greater Hartford metropolitan region; (ii)

the strong governmental forces that have created and maintained

racially and economically isolated residential communities in the

Hartford region and (iii) the consequent need for substantial

educational changes, within and across school district lines, to end

this pattern of 1sotation and inequality.

51. In 1965, the United states Civil Rights commission presented

a report to connenticut’s Commissioner of Education which documented

the widespread existence of racially segregated schools, both between .

urban and suburban districts and within individual urban school

districts. The report urged the defendant State Board to take

corrective action. None of the defendants or their predecessors took

‘appropriate action to implement the full recommendations of the report.

-

52. In 1965, the Hartford Board of Education and the City Council

hired educational consultants from the Harvard School of Education who

concluded: (i) that low educational achievement in the Hartford

‘schools was closely correlated with a high level of poverty among the

student population; (ii) that racial and ethnic segregation caused

educational damages to minority children; and (iii) that a plan should

be adopted, with substantial redistricting and interdistrict transfers

funded by the State, to place poor and minority children in suburban

schools.

53. In 1966, the Civil Rights Commission presented a formal

request to the governor, seeking legislation that would invest the

State Board of Education with the authority to direct full integration

of local sohbols. Neither the defendants nor their predecessors acted

to implement the request.

54. In 1966, the Committee of Greater Hartford Superintendents

proposed to seek a federal grant to fund a regional educational

advisory board and various regional programs, one of whose chief aims

would be the elimination of school segregation within the metropolitan

region.

55. In 1968, legislation supported by the Civil Rights Commission

was introduced in the Connecticut Legislature which would have

authorized the use of state bonds to fund the construction of racially

integrated, urban/suburban "educational parks," which would have been

located at the edge of metropolitan school districts, have had superior

academic facilities, have employed the resources of local universities,

and have been designed to attract school children Erem urban and

suburban districts. The Legislature did not enact the legislation.

56. In 1968, the defendant State Board of Education proposed

legislation that would have authorized the board to cut off State

funding for sanval districts that sailed to develope acceptable plans

for correcting racial imbalance in local schools. The proposal offered

state funding for assistance in the preparation of the local plans.

The Legislature did not enact the legislation.

57. Tn 1969, the Superintendent of the Hartford School District

called for a massive expansion of "Project Concerm,™ a pilot program

begun in 1967 which pused several hundred black and Hispanic children

from Hartford to adjacent suburban schools. The superintendent argued

that without a program involving some 5000 students -- one quarter of

.Hartford’s minority student population == the city of Hartford could

‘neither stop white citizens from fleeing Hartford to suburban schools

nor provide quality education for those students who remained. Project

Concern was Sever expanded beyond an enrollment of approximately 1,500

students. In 1988-89, the total enrollment jn Project Concern Was no

more than 747 students, less than 3 percent of the total enrollment in

the Hartford school system.

-20-

58. In 1969, the State Legislature passed a Racial Imbalance Law,

requiring racial balance within, but not between, school districts.

C.G.S. §10-226a et seg. The Legislature authorized the state

Department of Education to promulgate implementing regulations. C.G.S.

§10-226e. For over ten years, however, from 1969 until 1980, the

Legislature failed to approve any regulations to implement the statute.

59. From 1970 to 1982, - effective efforts were made by

Qefendants Tully to remedy the racial isolation and educational

inequities already previously identified by the defendants, which were.

‘growing in severity during this period.

60. In 1983, the State Department of Education established a

committee to address the problem of "equal educational opportunity" in

the State of Connecticut. The defendant board adopted draft guidelines

in December of 1984, which culminated in the adoption in May of 1986,

of a formal Education Policy statement and Guidelines by the State

‘Board. The Guidelines called for a state system of public schools

‘under which "no group of students will demonstrate systematically

different achievement based upon the differences -- such as residence

or race or sex ie that its members brought with them when they entered

school." The Guidelines explicitly recognized "the benefits of

residential and ecdnomic integration in [Connecticut] as important to

the quality of education and personal growth for all students in

Connecticut.m

61. In 1985, the State Department of Edcuation established an

Advisory Committee to Study Connecticut’s Racial Imbalance Law. In an

interim report completed in February of 1986, the Committee noted the

"strong inverse relationship between racial imbalance and quality

education in Conféntioutss public schools.' The Committee concluded

that this was true "because racial imbalance is coincident with

poverty, limited resources, low academic achievement and a high

incidence of students with special needs.' The report recommended that

the State Board consider voluntary interdistrict collaboration,

expansion of magnet school programs, metropolitan districting, or other

"programs tHat ensure students the highest quality instruction

possible."

82. In January, 1988, a report prepared by the Department of

Education’s Committee on Racial Equity, under the supervision of

defendant Tirozzi, was presented to the State Board. Entitled "A

Report on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Desegregation in Connecticut’s

Public Schools," the report informed the defendant Board that

Many minority children are forced by factors related to economic

development; housing, zoning and transportation to live in poor

urban communities where resources are limited. They often have

available to them fewer educational opportunities. Of equal

significance is the fact that separation means that neither they

nor their counterparts in the more affluent suburban school

districts have the chance to learn to interact with each other, as

they will inevitably have to do 2s adults living and working in a

multi-cultural society. Such interaction is 2a most important

element of quality education.

Report at 7.

dl ¥

63. In 1988, after an extensive analysis of Connecticut’s Mastery

Test results, the State Department of Education reported that "poverty,

as assessed by one indicator, participation in the free and reduded:

lunch program . . . [is an] important correlate[] of low achievement,

and the low achievement outcomes associated with these factors are

intensified by geographic concentration.’ Many other documents

available to, or prepared by, defendant State Board of Education and

the State Department of Education reflect full awareness both of these

educational realities and of their applicability to the Hartford-area

schools.

64. In April of 1989, the state Department of Education issued a

report, "Quality and Integrated Education: Options for Connecticut,”

in which it concluded that

[r]acial and economic isolation have profound academic and

affective consequences. Children who live in poverty —-- a burden

which impacts disproportionately on minorities —-- are more likely

to be educationally at risk of school failure and dropping out

before graduation than children from less impoverished homes.

Poverty is the most important correlate of low achievement. This

belief was borne out by an analysis- of the 1988 Connecticut

Mastery Test data that focused on poverty . . . . The analysis

also revealed that the low achievement outcomes associated with

poverty are “intensified by geographic and racial concentrations.

Report, at 1.

65. Turning to the issue of racial and ethnic integration, the

report put forward the findings of an educational expert who had been

commissioned by the Department to study the effects of integration:

es indicate improved achievement for

tegrated settings and at the same time

the fear that integrated classrooms

[T]he majority of studi

minority students in in

offer no substantiation to

impede the progress of more advantaged white students.

Furthermore, integrated education has long-term positive effects

on interracial attitudes and behavior . . . .

66. Despite recognition of the "alarming degree of isolation" of

poor and minority schoolchildren in the City of Hartford and other urban school systems, Report at 3, and the gravely adverse impact this

isolation has on the educational opportunities afforded to plaintiffs

and other urban schoolchildren, the Report recommended, and the

defendants have announced, that they intend 50 pursue an approach that

would be "voluntary and incremental." Report, at 34.

66a. In January of 1993, in response to this lawsuit, defendant

Governor Lowell Weicker, in nis annual state of the state address,

called on the Ledislabure to address "[t]he racial and economic

| isolation in Connecticut’s school system," and the related educational

inequities in Connecticut’s schools.

66b. As in the past, the legislature failed to act effectively

in response to the Governor’s call for school desegregation

initiatives. Instead, a voluntary desegregation planning bill was

—- 4

passed, P.A. 93-263, which contains no racial or poverty concentration

goals, no guaranteed funding, no provisions for educational

enhancements for city schools, and no mandates for local compliance.

E. THE STATE’S FAILURE TO TAKE EFFECTIVE ACTION

67. The duty of providing for the education of Connecticut

school children, through the support and maintenance of public schools,

has always been deemed a governmental duty resting upon the sovereign

State.

/

68. The defendants, who have knowledge that Hartford

schoolchildren face educational inequities, have the legal obligation

under Article First, gs and 20, and Article Eighth, §1 of the

Connecticut Constitution to correct those inequities.

69. Moreover, the defendants have full power under Connecticut

statutes and the Connecticut constitution to carry out their : :

constitutional obligations and to provide the relief to which

plaintiffs are entitled. C.G.S. §10-4, which addresses the powers and

duties of the state Board of Education and the State Department of

Education, continues with §10-4a, which expresses ''the concern of the

state (1) that each child shall have . . . equal opportunity to receive

- 5

a suitable program of educational experiences.' Other provisions of

state law give the Board the power to order local or regional remedial

planning, to order local or regional boards to take reasonable steps to

comply with state directives, and even to seek judicial enforcement of

its orders. See §10-4b. The Advisory Committee on Educational Equity,

‘established by §10-4d, is also expressly empowered to make appropriate

recommendations to the Connecticut State Board of Education in order

"to ensure equal educational opportunity in the public schools.”

70. Despite these clear mandates, defendants have failed to take

corrective measures to insure that its Hartford public schoolchildren

receive an equal educational opportunity. Neither the Hartford school

district, which is burdened both with severe educational disadvantages

and with racial and ethnic isolation, nor the nearby suburban yi

districts, which are also racially isolated but do not share the

educational burdens of a large, poverty-level school population, have

been directed by defendants to address these inequities jointly, to

reconfigure district lines, or to take other steps sufficient to

eliminate these educational inequities.

-26=

71. [Withdrawn.]

72. Deprived of more effective remedies, the Hartford school

district has likewise not been given sufficient money and other

‘resources by the defendants, pursuant to §10-1l40 or other statutory and

constitutional Fraviglons, adequately to address many of the worst

impacts of the educational deprivations set forth in 4423-27 supra.

The reform of the State’s school finance law, ordered in 1977 pursuant

to litigation in the Horton V. Meskill case, has not worked in practice

adequately to redress these inequities. Many compensatory or remedial

services that might have mitigated the full adverse effect of the

constitutional violations set forth above either have been denied to

the Hartford school district or have been funded by the state at levels

‘that are insufficient to ensure their effectiveness to plaintiffs and

.other Hartford schoolchildren. |

IV. LEGAL CLATIMS

FIRST COUNT

73. varagraphe 1 through 34 are incorporated herein by reference.

74. Separate educational systems for minority and non-minority

students are inherently unequal.

75. Because of the de facto racial and ethnic segregation between

lEartford and the suburban districts, the defendants have failed to

provide the plaintiffs with an equal opportunity to a free public

«37 ~

leducation as required by Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth,

§1, of the Connecticut Constitution, to the grave injury of the

plaintiffs,

SECOND COUNT

76. Paragraphs 1 through 72 are incorporated herein by reference.

77. . Separate educational systems for minority and non-minority

students in fact provide to all students, and have provided to

plaintiffs, unequal educational opportunities.

78. Because of the racial and ethnic segregation that exists

between Hartford and the exbREbaY districts, perpetuated by the

defendants and resulting in serious harm to the plaintiffs, the

defendants have discriminated against the plaintiffs and have failed to

provide them with an equal opportunity to a free public education as

required by Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, §1 of the

Connecticut Constitution.

THIRD COUNT

79. Paragraph 1 through 72 are incorporated herein by reference.

80. The maintenance by the defendants of a public school district

in the City of Hartford: (1) that is severely educationally

disadvantaged in comparison to nearby suburban school districts: (ii)

that fails to provide Hartford schoolchildren with educational

opportunities equal to those in suburban districts; and (iii) that

. -28-

fails to provide a majority of Hartford schoolchildren with a minimally

adequate education measured by the state of Connecticut’s own standards

-- all to the great detriment of the plaintiffs and other Hartford

schoolchildren -- violates Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article

Bighth, §1 of the connecticut Constitution. FOURTH COUNT

81. Paragraphs 1 through 72 are incorporated herein by reference.

82. The failure of the defendants to provide to plaintiffs and

other Hartford schoolchildren the equal educational opportunities to

which they are entitled under connecticut law, including §10-4a, and

which the defendants are obligated to ensure have been provided,

violates the Due Process Clause, Article First, §§8 and 10, of the

Connecticut Constitution. 5

RELIEF

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs respectfully

request this Court to: |

1. Enter a declaratory judgment

a. that public schools in the greater Hartford metropolitan

region, which ol segregated de facto by race and ethnicity, are

inherently unequal, to the injury of the plaintiffs, in violation of

Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, §1 of the Connecticut

Constitution;

gO

Db. that the public schools in the greater Hartford

metropolitan region, which are segregated by race and ethnicity, do not

provide plaintiffs with an equal educational opportunity, in violation

of Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, §1, of the

Connecticut Constitution;

c. that the maintenance of public schools in the greater

Hartford metropolitan region that are segregated by economic statutes

severely disadvantages plaintiffs, deprives plaintiffs of an equal

educational opportunity, and fails to provide plaintiffs with a

minimally adequate education =-- all in violation of Article First, §§1

and 20 and Article Eighth §1, and C.G.S. §10-4a2; and

d. that the failure of the defendants to provide the

schoolchildren plaintiffs with the equal educational opportunities to

which they are entitled under Connecticut law, including §l0-4a2,

violates the Due Process clause, Article First, §§8 and 10, of the

Connecticut Constitution.

2. Issue a temporary, preliminary .and permanent injunction,

enjoining defendants, their agents, employees, and successors in office

A

~

from failing to provide, and ordering them to provide:

a. plaintiffs and those similarly situated with an

integrated education;

30

b. plaintiffs and those similarly situated with equal

educational opportunities;

c. plaintiffs and those similary situated with a minimally:

adequate education;

3. Assume and maintain jurisdiction over this action until such

time as full relief has been afforded plaintiffs;

4. Award plaintiffs reasonable costs and attorneys’ fees; and

5. Award such other and further relief as this Court deems

necessary and proper.

PLAINTIFFS, MILO SHEFF, ET AL.

—

Wesle . Hortdn

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06105

(20 22-8338

Ph Brittaiw -

IVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT

School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06103

Mor Hee Sha

Martha Stone

CCLU

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

HY Ceres

Philip D. Tegeler

CCLU

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Ao bcos

Helen Hershkoff

Adam S. Cohen

ACLU

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

Marianne £ngelman Lado

Theodore Shaw

Dennis D. Parker

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

: WN

Vsandra Del Valle

Puerto Rican Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Cons Sins edn ns in

Wilfred Rodriguez (J ( )

NEIGHBORHOOD LEGAL S ICES

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06102

CERTIFICATION

I hereby certify that a copy of the foregoing was mailed or hand-

delivered to the following counsel of record on November 23, 1994:

Bernard McGovern, Esq.

Martha Watts Prestley, Esq.

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

110 Sherman Street

Hartford, CT 06105

RTS —

“Wesley W. Horton