NAACP Legal Defense Fund Charges Louisiana, Mississippi School Boards Delay Supreme Court Ruling

Press Release

August 6, 1968

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 5. NAACP Legal Defense Fund Charges Louisiana, Mississippi School Boards Delay Supreme Court Ruling, 1968. 615dcade-b892-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4cc78dd-4819-471f-84b3-2c44c555bcc2/naacp-legal-defense-fund-charges-louisiana-mississippi-school-boards-delay-supreme-court-ruling. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

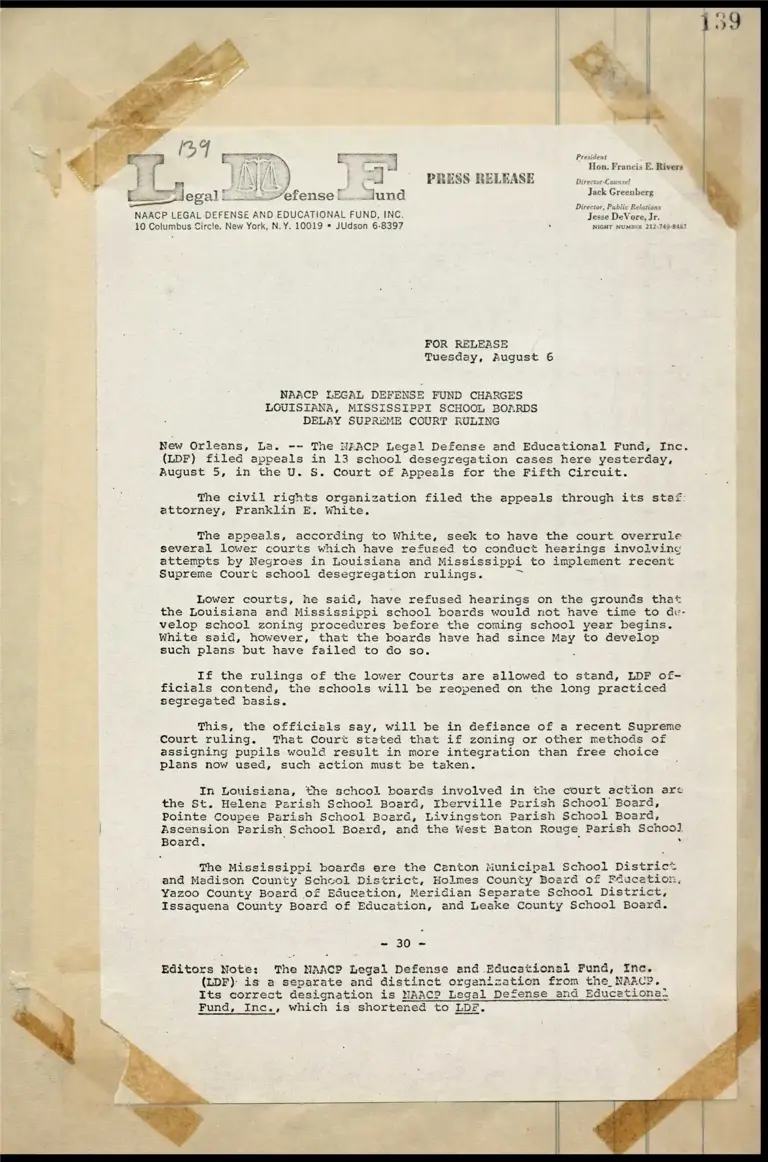

PRESS RELE. bs] ees | J a 5

Jegal Defense [lund

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. Tease DoVica ae)

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 * JUdson 6-8397 . NIGHT NUMBER 212-749-8487

FOR RELEASE

Tuesday, August 6

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND CHARGES

LOUISIANA, MISSISSIPPI SCHOOL BOARDS

DELAY SUPREME COURT RULING

New Orleans, La. -- The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF) filed appeals in 13 school desegregation cases here yesterday,

August 5, in the U. S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

The civil rights organization filed the appeals through its staf

attorney, Franklin E. White.

The appeals, according to White, seek to have the court overrule

several lower courts which have refused to conduct hearings involvin¢e

attempts by Negroes in Louisiana and Mississippi to implement recent

Supreme Court school desegregation rulings.

Lower courts, he said, have refused hearings on the grounds that

the Louisiana and Mississippi school boards would not have time to de-

velop school zoning procedures before the coming school year begins.

White said, however, that the boards have had since a to develop

such plans but have failed to do so.

If the rulings of the lower Courts are allowed to stand, LDF of-

ficials contend, the schools will be reopened on the long practiced

segregated basis.

This, the officials say, will be in defiance of a recent Supreme

Court ruling. That Court stated that if zoning or other methods of i

assigning pupils would result in more integration than free choice

plans now used, such action must be taken.

In Louisiana, the school boards involved in the court action are

the St. Helena Parish School Board, Iberville Parish School Board,

Pointe Coupee Parish School Board, Livingston Parish School Board,

Ascension Parish School Board, and the West Baton Rouge Parish School

Board. : s .

The Mississippi boards are the Canton Municipal School District

and Madison County Schcol District, Holmes County Board of Fducation

Yazoo County Board of Education, Meridian Separate School District,

Issaquena County Board of Education, and Leake County School Board.

=530%—

3 - Editors } Note: The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

“ake (LDF): is a separate and distinct organization from the_NAAC?.

Its correct designation is NAACP Legal Defense and Educationa2

Fund, Inc., which is shortened to LDF.