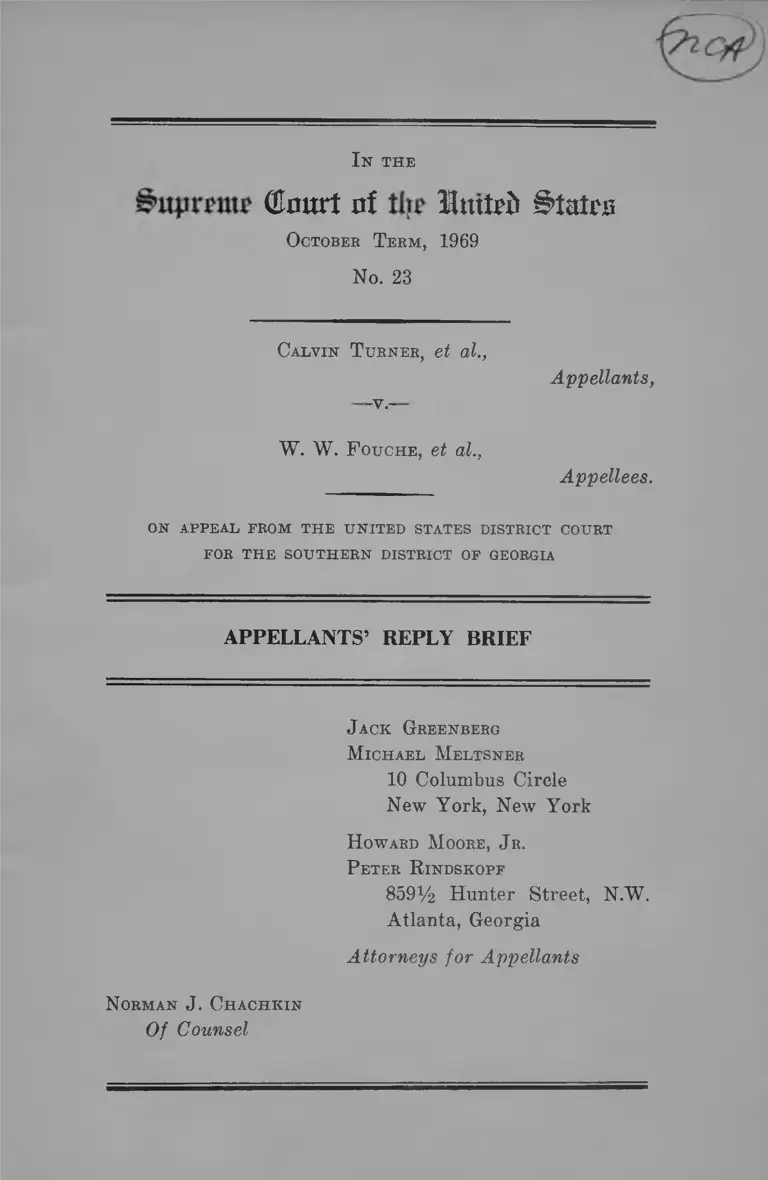

Turner v. Fouche Appellants' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Turner v. Fouche Appellants' Reply Brief, 1969. 64d9e702-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4ef0eb1-53e2-4a5c-9dcf-badb0ae92068/turner-v-fouche-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

Qlourt of MnxUh §>tatro

OcTOBEE Term, 1969

No. 23

Calvin T urner, et al.,

Appellants,

-V.-

W. W. F ouche, et al.,

Appellees.

ON appeal from the united states district court

FOR the southern DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

H oward Moore, J r.

P eter R indskopf

8591/4 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Norman J . Chachkin

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Tabi^ of Cases

PAGE

Anderson (and Hinton) v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206

(1968) ............................................................................ 5

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ......................... 6

Avery v. Midland County Texas, 390 U.S. 474, 484

(1968) ............................................................................ 10

Bell V. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967) ........ 8

Broadway v. Culpepper, —— F. S upp.----- (No. 904

M.D. Ga. 1969) ................. 6

Brown v. AUen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953) ............................. 3

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, 395

U.S. 225 (1969) ........................................................... 9

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S. 701 (1969) ....10,11,12

Cobb V. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964) .......... 6

Cobb V. Georgia, 389 U.S. 12 (1967) ............................. 5

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963) ........ 2

Gamble v. Grimes, XIA Race Eel. L. Rep. 2028 (N.D.

Ga. 1966) ...................................................................... 6

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) .................................................................... 10

GrifSn v. School Board of Prince Edward County,

Virginia, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ..................................... 10

Hague V. CIO, 307 U.S. 406 (1939) ............................. 4

Jones V. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967) ......................... 5

11

PAGE

Kramer v. Union Free School District No. 15, 395 U.S.

621 (1969) ..........................................................9,10,11,12

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, (1965) —.4, 6, 7,8

Moore v. Dutton, 396 F.2d 783 (5th Cir. 1968) ........ 6

Powell V. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486 (1969) ................ 10

Pullum V. Greene, 396 F.2d 251 (5th Cir. 1968) ........ 6

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1956) ........................... 6

Schnell v. Davis, 336 U.S. 933, affirming 81 F. Supp.

872 (D.C. S.D., Ala.) .................................................... 4

Sims V . Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) ......................... 5

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) .... 4

Stokes V . Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964) .... 9

Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 410 (1968) ...................... 5

Sullivan v. State, ----- Ga. ----- , 168 S.E.2d 133

(1969) ............................................................................ 1,3

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga. 1965) .... 9

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 LT.S. 81 .... 4

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965) ....... 6

Vanleeward v. Rutledge, 369 F.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1966) 6

Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1965) 6

Whippier v. Dutton, 391 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1968) .... 6

Wliitus V. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 ( 5th Cir. 1964) ....... 6

Whitus (and Davis) v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) __ 6

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1955) ...................... 6

Williams v. Rhodes. 393 U.S. 23 (1968) ...................... 10

Ill

Table of Constitutional and

S tatutoey P rovisions

PAGE

Ala. Code Tit. 30 §21 (1966) ....................................... 3

Ga. Code Aim.—

§2-6801 .................................................................. 6,8,10

§2-3802 ...................................................................... 9

§24-2501 .................................................................... 9

§32-902 ...................................................................... 10

§32-902.1 .................................................................... 10

§59-106 .....................................................................1,2,3

Ga. Constitution, Art. VII, §V, Par. 1 ....................... 10

North Carolina Gen. Stat. §9-3 (1967) ............................ 3

28 U.S.C. §1861 ................................................................. 7

28 U.S.C. §1865 ................................................................. 7

42 U.S.C. §1971 ................................................................. 5

Other A uthorities

Carter, Scottsboro (Louisiana State University Press

(1969)) .......................................................................... 6

Franklin, Eeconstruction After the Civil War (Uni

versity of Chi. (1961)) ................................................ 6

United States Code Congressional and Administrative

News, 90th Congress, 2nd Sess.................................... 7

I n’ the

ûprrm]? Olourt nf

October Term, 1969

No. 23

Calvin T urner, et al.,

— V . —

W. W. F ouche, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITE D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E SO U TH ER N DISTRICT OP GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

I.

In its Brief, the State of Georgia expresses the view that

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106, which authorizes jury commis

sioners to select for jury service only persons whom the

commissioners believe are “intelligent and upright”, pro

vides sufficiently precise guidance as to which “citizens of

the County” are to be included and which excluded from

the jury list. In support of this conclusion the state quotes

a decision of the Supreme Court of Georgia (“An intelli

gent person is one possessed of ordinary information and

reasoning facilities,” Sullivan v. S ta te ,----- Ga. ----- , 168

S.E.2d 133 (1969)) and the chairman of the jury commis

sion who testified that an “upright” citizen is one who

enjoys a good reputation in the community (Brief p. 16).

It is also urged that the English language always contains

room for varying interpretations, and that the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment contain language more indefinite than Gla. Code Ann.

§59-106.

Appellants have no quarrel with the general notion that

some uncertainty as to meaning is inevitable in the drafting

of legislative enactments. It is quite another matter, how

ever, to conclude that officials such as jury commissioners

can non-arbitrarily distinguish between adults on the basis

of whether they are “intelligent and upright”—statutory

tests which are nowhere given content or objectively de

fined. Assuming good faith on the part of the commis

sioners—an assumption which this record refutes—neither

the statute, the practice of the commissioners under it,

nor decisions of the Georgia courts, adopt standards for

exclusion or inclusion which do more than reiterate the

open-ended, subjective, discretion conferred by the words,

“intelligent and upright.” Cf. Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U.S. 229 (1963). The statute simply does not offer

guidance to assist one determining whether any particular

individual is qualified for jury service. Guidance to assist

one determining whether particular individuals are quali

fied for jury service is not given by replacing one set of

vague and overbroad terms with another.^ 'WTiat, for ex

ample, is one to make of the notion that a Georgia juror

is “intelligent” if possessed of “ordinary information”

' Even the dictionary definition of “intelligence” reflects some of

the confusion encountered by any definition which does not rely

on an objective standard: “Psychologists still debate the question

whether intelligence is a unitary characteristic of the individiial

or a sum of his abilities to deal with various types of situation.”

Webster's New International Dictionary (2d Ed.).

The word “upright” is defined by Webster’s as being “morally

correct.” A standard more likely to reflect the prejudices of the

person making the selection is difficult to imagine.

and “upright” if “honorable, honest and will do right as

he sees it” ? ̂ Sullivan v. State, supra at 137. The Georgia

Supreme Court opinion in Sullivan v. State also states

that “No particular degree of intelligence is required hy

this statute. Idiots, morons, and insane persons are not

intelligent and would not qualify.” There is no sugges

tion, however, that §59-106 excludes only the classes of

mentally disabled persons enumerated. And the statute

betrays no such intent, although it would he an easy mat

ter to write a statute which confined the discretion of

the commissioners to excluding such classes of persons

from service, see e.g.. North Carolina Gen. Stat. §9-3

(1967); Ala. Code Tit. 30 §21 (1966). Perhaps, the failure

of the Georgia Legislature to define those characteristics

which amount to a disqualification might pass constitu

tional muster if the commissioners themselves, or the

Georgia courts, construed Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 in a more

definite manner—as, for example, this Court construes the

Fourteenth Amendment. But nothing of this sort has oc

curred and Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 remains as vague and

over-broad as when it was written. (See A. 36).

Another branch of the State’s argument is that a statute

may not be invalidated because of a capacity for wrongful

administration attributable to its vagueness or overbreadth.

2 The Georgia Supreme Court in Sullivan also relies on a passage

in this Court’s opinion in Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443, 474 (1953)

to the effect that to satisfy federal constitutional requirements a

jury sleection statute need only reflect “the cross-section of the

population suitable in character and intelligence for that civic

duty.” The court takes this to mean that a statute which uses the

words “intelligent” and “upright” is thereby constitutional. In

doing so it confuses the constitutionally acceptable goal of seeking

jurors of intelligence and character (as stated in Brown v. Allen)

with the means of reaching that goal which, to satisfy Fourteenth

Amendment requirements, must contain a sufficiently definite test

of eligibility not to invite capricious distinction between individuals

or to serve as a mask for racial discrimination.

It is said that all statutes are capable of wrongful adminis

tration, and, therefore, that the only remedy for the use of

language such as “intelligent and upright” to exclude Ne

groes in Georgia from jury service is to obtain injunctive

relief in every case against particular jury commissioners

who discriminate racially. We will not here repeat our dis

cussion of the reasons why the language of Ga. Code Ann.

§59-106 provides a particular and severe threat to non-

racial selection of jurors in Georgia, or the reasons why a

general injunction against racial selection is of minimal

value as long as excessive discretion vested in the commis

sioners provides an easy justification for what is actually

racial exclusion. These matters are set forth in some detail

in Appellants’ Brief, pp. 30-37. We point out, however, that

the rule that a statute violates the Fourteenth Amendment

when it confers standardless discretion upon public officials

to make up the “law” in every case has been consistently

applied by this Court, See South Carolina v. Katzenhach,

383 U.S. 301, 313 (1966); Hague v. CIO, 307 U.S. 406

(1939). Indeed, the State’s contention was rejected by the

Court in Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 153

(1965):

The cherished right of people in a country like ours to

vote cannot be obliterated by the use of laws like this,

which leave the voting fate of a citizen to the passing

whim or impulse of an individual registrar. Many

of our cases have pointed out the invalidity of laws

so completely devoid of standards and restraints.

See, e.g.. United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255

U.S. 81, 65 L.ed. 516 41 S Ct 298, 14 ALE 1045.

Squarely in point is Schnell v. Davis, 336 U.S. 933, 93

L.ed 1093, 69 S Ct 749, affirming 81 P. Supp. 872 (D.C.

S.D. Ala.), in which we affirmed a district court judg

ment striking down as a violation of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments an Alabama constitutional pro

vision restricting the right to vote in that State to per

sons who could “understand and explain any article of

the Constitution of the United States” to the satisfac

tion of voting registrars. We likewise affirm here the

District Court’s holding that the provisions of the

Louisiana Constitution and statutes which require

voters to satisfy registrars of their ability to “under

stand and give a reasonable interpretation to any sec

tion” of the Federal or Louisiana Constitution violate

the Constitution. And we agree with the District Court

that it specifically conflicts with the prohibitions

against discrimination in voting because of race found

both in the Fifteenth Amendment and 42 USC <§.1971

(a) to subject citizens to such an arbitrary power as

Louisiana has given its registrars under these laws.

As with voting registrars in Louisiana, use by the com

missioners of indefinite eligibility tests to exclude Negroes

from jury service is not merely an abstract possibility.

Georgia jury commissioners in Taliaferro County and

elsewhere have consistently misapplied their authority for

the forbidden purpose of excluding Negroes.® Cobb v.

Georgia, 389 U.S. 12 (1967) (per curiam) (Bibb County);

Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 410 (1968) (per curiam)

(Lamar County); Anderson (and Hinton) v. Georgia, 390

U.S. 206 (1968) (per curiam) (Crisp County); Jones v.

Georgia, 389 U.S. 24 (1967) (per cnriam) (Bibb County);

Sims V. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) (per curiam) (Charl-

® Of course, use of the “intelligent and upright” qualification

is not the only manner by which Georgia jury commissioners

have discriminated against blacks in jury selection. Until recently,

commissioners also employed racially separate tax books to dis

criminate in selection. The point is that the “intelligent and up

right” qualification provided a ready opportunity for discrimi

nation which Georgia jury commissioners are inclined to take

advantage of by custom and practice.

ton County); WMtus (and Davis) v. Georgia, 385 U.S.

545 (1967) (Mitchell County); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S.

85 (1956) (Cobb County); Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S.

375 (1955) (Fulton County); Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S.

559 (1953) (Pulton County); Vanleeward v. Rutledge,

369 P.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1966) (Muscogee County); Whippier

V. Dutton, 391 F.2d 425 (5th Cir. 1968) (Bibb County); Cohb

V. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964) (Jasper County);

Pullum V. Greene, 396 F.2d 251 (5th Cir. 1968) (Terrell

County); Moore v. Dutton, 396 F.2d 783 (5th Cir. 1968)

(per curiam) (Camden County); Whippier v. Balhcom, 342

P.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1965) (Bibb County); Whitus v. Balkcom,

333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) (Mitchell County); Gamble v.

Grimes, XIA Eace Eel. L. Eep. 2028, (N.D. Ga. 1966)

(Pulton County); Broadway v. Culpepper, ----- P. Supp.

----- (No. 904, M.D. Ga. 1969) (Baker County).^

* The requirement that Georgia jurors be intelligent and up

right apparently dates from the Georgia Constitution of 1868

which authorized the General Assembly to “provide by law for

the selection of upright and intelligent persons to serve as jurors.”

One year after adoption of the Constitution of 1877 (which au

thorized “the selection of the most experienced, intelligent and

upright men to serve as grand jurors, and intelligent and upright

men to serve as traverse jurors”.) Georgia adopted “An Act to

carry into elfect Paragraph 2, Section 18, Article 6 of the Consti

tution of 1877 so as to provide for the selection of the most ex

perienced, intelligent and upright men to serve as grand jurors,

and of intelligent and upright men to serve as traverse jurors

and for the drawing of juries.” (Acts 1878-79, pp. 34-35)

It is of course significant that the intelligent and upright re

quirement came into Georgia law at a time when southern states

freely adopted vague and overbroad laws as “nothing more than

a mask for excluding the names of an}̂ and all Negroes.” See

Carter, Seottsboro (Louisiana State University Press (1969)) pp.

196-97; Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965); United

States V. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965). Of the political situa

tion in Georgia, in 1868, a distinguished historian has written

“In September, 1868, the Georgia Legislature formally declared

all Negro members ineligible to sit in that body . . . No other

former confederate state put on such a display of incorrigibility.”

Franklin, J. II., Keconstruction After the Civil War (University

of Chi. Press (1961)) pp. 131-133.

The general injunction against racial discrimination

which the district court granted, and which appellees con

tend is sufficient, cannot eliminate persistent discrimination

on such a scale. As the Court recognized in Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. at 152, a vague and overbroad

statute “practically places . . . [the commissioners] deci

sion beyond the pale of judicial review.” Nor are proper

jury selection standards difficult to ascertain and ad

minister. See 1968 Jury Selection and Service Act, Public

Law No. 90-273, 28 IJ.S.C. §§1861 et seq. The suggestion

in the State’s Brief (p. 13) that 28 U.S.C. §1865 gives a

federal judge similar power to a Georgia jury commis

sioner is unpersuasive. Under the Jury Selection and

Service Act, the requirement that one must “read, write

and understand the English language with a degree of

proficiency sufficient to fill out satisfactorily the juror

qualification form”, 28 U.S.C. §1865 (b) (2), is a deter

mination made on the objective basis of “information pro

vided on the juror qualification form and other compe

tent evidence” 28 U.S.C. §1865 (a).^ Appellees further con

tention that somehow Georgia’s subjective eligibility stan

dards are required by the Sixth and Seventh Amendment

falls of its own weight. Appellants do not contend that a

state cannot ensure that its jurors are qualified for the

work at hand, but rather that the standard used to select

eligible jurors must be sufficiently clear to provide for

minimum regularity and accountability. The adoption of

words such as “intelligent and upright”, as to which each

person may have a different view, does not satisfy the Four

teenth Amendment for it leaves a citizen’s eligibility to the

̂Appellees overlook that the Federal Jury Selection and Ser

vice Act requires that each circuit adopt a plan of selection which

will ensure objective random selection rather than the subjective

character and intelligence judgments which were permitted by

prior law. See United States Code Congressional and Adminis

trative News, 90th Congress, 2nd Sess., pp. 748-763.

8

“passing whim or impulse” of a jury commissioner, Louisi

ana V. United States, supra at 380 U.S. 153.

II.

Neither the State of Georgia, nor remaining appellees,

make an attempt to deny that racial discrimination infected

the process of selection of Taliaferro County school hoard

members prior to the institution of this litigation. Appel

lees appear to contend, however, that appellants are not

entitled to relief because a Negro was appointed to fill one

of two vacancies on the five-man school board and his ap

pointment was later ratified, as required by Ga. Code Ann.

§2-6801, by a recomposed grand jury.

The short answer to appellees’ contention is that Negroes

were excluded in the selection of the new grand jury which

filled the two vacancies. (See Appellants’ Brief pp. 25-38).

But even if the two vacancies had been filled by a constitu

tionally selected body, this would not have remedied the

undoubted unconstitutional selection of the remaining three

school board members for they were selected by the pre

vious grand jury—from which Negroes were excluded in

even more gross fashion than on the recomposed grand

jury. At a minimum, then, the district court should have

declared that the school board was selected in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment, ordered its membership va

cant, and required the entire board selected on a non-racial

basis. Bell v. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967).

Nor were striking down the offensive system of selection

or vacating the membership of the board the only rem

edies available to the district court. Given the situation

in Taliaferro County where an all-white board adminis

tered an all-Negro school system, the district court could

have—if it found such relief temporarily warranted to

remove the past etfects of discrimination—“appropriately

restricted control of the school to Negro parents until

whites demonstrated the kind of good faith which would

render their participation no longer a danger to Negroes,

say by reversing the withdrawal of their children from

the system.” (Appellants’ Brief pp. 45-48); cf. Carr v.

Montgomery County Board of Education, 395 U.S. 225

(1969). Or the district court could have reappointed a

receiver to operate the public schools, a step which it

had found necessary in earlier litigation between mem

bers of the Negro community and public officials in this

county. Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D., Ga.,

1965). The district court failed to select one, or several, of

these courses because it concluded—erroneously, appellants

contend—that the addition of one Negro member to the

school board was sufficient to reform an unconstitutional

system of selection which enables whites to control a

school system that no white children attend.

It should be noted the county school board appointment

process begins when a superior court judge appoints the

six jury commissioners responsible for selection of the

jury lists. Candidates for superior court judgeships are

nominated and elected by the voters of Taliaferro County

in addition to the voters of five other counties, Ga. Code

Ann. §24-2501, 2-3802. (Prior to 1966 the superior court

judges were elected by all the voters of the State, see

Stokes V. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964). The

result is that at no point in the system do Taliaferro

Negroes have an “effective voice” in the process of school

board selection, for the official (the superior court judge)

whose appointments (of jury commissioners) determine

who will select the school board is only remotely responsi

ble to Taliaferro county black voters. Cf. Kramer v.

Union Free School District No. 15, 395 U.S. 621, 627 n. 7,

10

628-29; Avery v. Midland County Texas, 390 U.S. 474,

484 (1968).

Appellees also appear to dispute that the district court

should initially fashion the particular relief appropriate to

remedy the effects of past discrimination in selection of the

school board. The general practice, however, has been to

leave matters of this sort to the discretion of the district

court in the first instance. Green v. School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Griffin v. School Board of

Prince Edivard County, Virginia, 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

Powell V. McCormack, 395 U.S. 486, 550 (1969). Given

the district court’s familiarity with the operation of the

school system in the county, there is no reason why a

different practice should apply here.

III.

This Court’s decisions last term in Cipriano v. City of

Houma, 395 U.S. 701 (1969) and Kramer v. Union Free

School District No. 15, 395 U.S. 621 (1969), make perfectly

plain that Article VII, §V, Par. 1 of the Georgia Constitu

tion and Ga. Code Ann., §'5i2-6801; 32-902, 902.1 violate the

Fourteenth Amendment by excluding from membership on

a Georgia school board persons who do not own real prop

erty. Cf. Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968).

In Kramer, a New York statute denied the right to vote

in a school hoard election only to those who were not owners

or lessees of real property within the district or parents

and guardians of school children. Nevertheless, the statute

violated the Equal Protection Clause because there \vas no

proof that it was necessary to promote a compelling state

interest, and no showing that the persons permitted to vote

had any greater interest in school affairs than those who

were not permitted to vote. In Cipriano, the city main-

11

tained that real property owners had a special interest in

an election held to approve the issuance of a municipality’s

utility revenue bonds (because property values were af

fected by the outcome) and that this interest was sufficient

to warrant exclusion of others. In striking down the Louisi

ana constitutional provision involved, this Court held that

all utility users—not only property owners—were affected

by the character of utility service.

As appellants read the State’s Brief, Georgia has declined

to state a specific justification for the exclusion of non-free

holders from school hoard membership such as that free

holders are “directly affected”, Kramer, supra 395 U.S.

at 631, or that they have a “special pecuniary interest”

in the operation of the schools which others do not have,

Cipriano, supra, 395 U.S. 704. The state concedes that

“the desirability and wisdom of the ‘freeholders’ require

ments for state or county political office may be indeed open

to question” (p. 26) and merely asserts the right of a legis

lature to impose property qualifications if it wishes. In

deed, because the Georgia law reflects no attempt to non-

arbitrarily restrict service to those affected, such an at

tempt to justify the exclusion would fail. While it might,

at most, be argued that a property owner has an infinitesi

mally greater financial interest in the costs of the school

system than a non-property owner, any parent plainly has

a far greater concern in board membership than any non

parent, regardless of whether he is a freeholder. Georgia

law, however, makes eligible only those parents who own

real property.

The state also argues that the constitutionality of the

freeholder restriction is not justiciable. The district court,

however, granted the petition for intervention, without ob

jection from appellees, of a non-freeholder and father of

six school children who was barred from selection to the

12

school board expressly in order to resolve the constitu

tionality of the freeholder requirement (A. 370-71; 72, 73).

The remaining appellees argue that property owners have

the capacity to deal with the duties of school board office

which non-property owners do not possess:

“a person having such fiscal responsibilities should have

the qualification of having acquired some property

himself.” (Brief p. 11)

This argument simply does not stand examination in light

of the facts of contemporary life, for “some property” need

not mean real property. Men and women exercise consider

able fiscal responsibilities, both in public and private life,

without ownership of real property. Similar to the non

property owners disfranchised in Cipriano and Kramer,

non-property owners in Georgia feel the impact of the opera

tion of the public schools and are entitled to a voice in their

operation, regardless of whether they are real property

owners. Moreover, the state’s Brief exposes the fact that

the freeholder qualification does not even serve the limited

purpose the remaining appellees seek to employ as its

justification:

. . . it would still seem that an individual who was a

serious aspirant for the office of county school board

member would be able to obtain a conveyance of the

single square inch of land he would require to become

a “freeholder.” (Brief p. 26)

The notion the freeholder requirement should be upheld

because one could become a freeholder by acquiring a

“single square inch” of land demonstrates that the require

ment need not serve the purpose of ensuring qualified pub

lic school board members which remaining appellees claim

for it. Rather it prohibits those non-property owmers

13

who do not wish to submit to such chicanery from being

selected as school board members. As the freeholder re

quirement plainly discriminates against the poor without

satisfying a compelling state interest, it violates the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Kespectfully submitted,

J ack Gkeekbeeg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

H oward Moore, J r.

P eter E indskopf

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Norman J . Chachkin

Of Counsel

M EIIEN PRESS INC. — N. t. C. 219