East Hartford Education Association v. East Hartford Board of Education Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

August 26, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. East Hartford Education Association v. East Hartford Board of Education Court Opinion, 1977. e6f9a75b-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d4ff048a-2cd0-48cf-89ec-845c2872fc4c/east-hartford-education-association-v-east-hartford-board-of-education-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-jv j 1 • b - i- C it e d *

Raw '< sxkr •'1- ■ - 1*3J®

&.> 8 B A B 5f

AUG 26 19TT

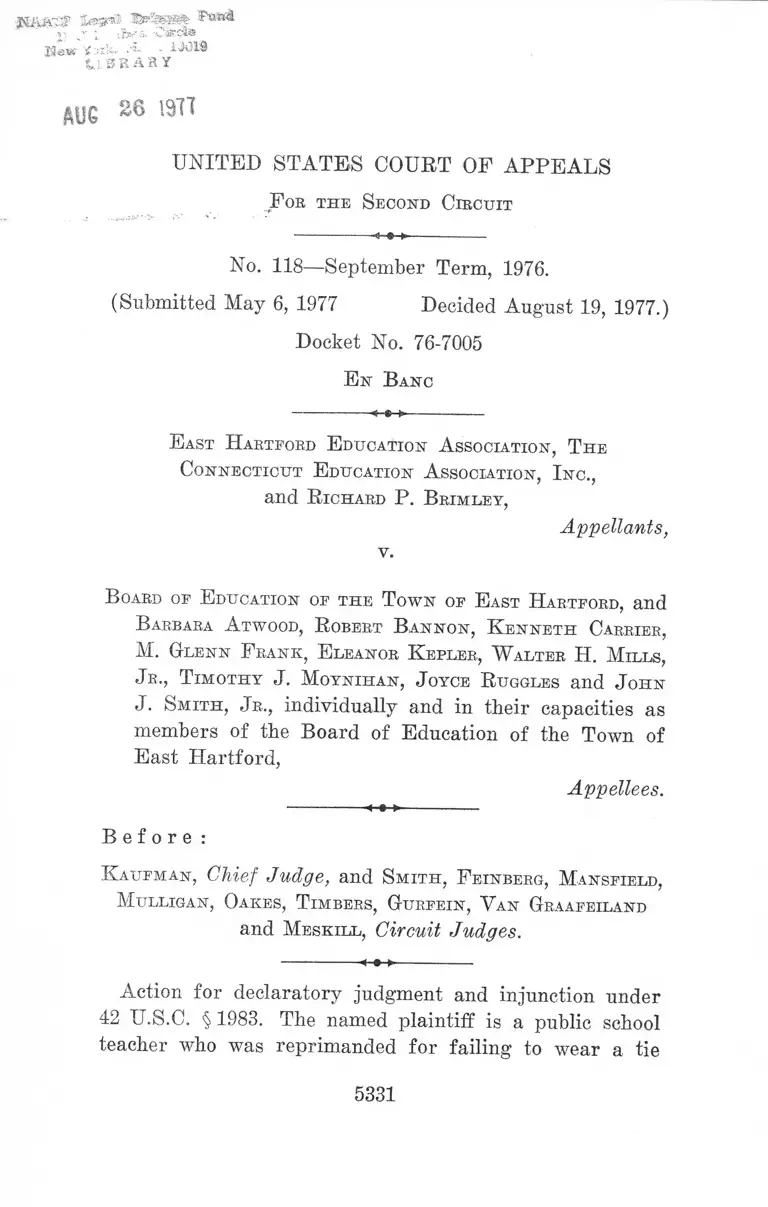

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or t h e S e c o n d C ir c u it

No. 118—September Term, 1976.

(Submitted May 6, 1977 Decided August 19, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-7005

E n B anc

E a s t H a r t f o r d E d u c a t io n A s s o c ia t io n , T h e

C o n n e c t ic u t E d u c a t io n A s s o c ia t io n , I n c .,

and R ic h a r d P. B r i m l e y ,

Appellants,

v.

B oard o f E d u c a t io n o f t h e T o w n o f E a s t H a r t f o r d , and

B a r b a r a A t w o o d , R o b e r t B a n n o n , K e n n e t h C a r r ie r ,

M . G l e n n F r a n k , E l e a n o r K e p l e r , W a l t e r H. M i l l s ,

J r ., T i m o t h y J . M o y n i h a n , J o y c e R u g g l e s and J o h n

J. S m i t h , J r ., individually and in their capacities as

members of the Board of Education of the Town of

East Hartford,

Appellees.

B e f o r e :

K a u f m a n , C h i e f Judge, and S m i t h , F e in b e r g , M a n s f ie l d ,

M u l l i g a n , O a k e s , T im b e r s , G u r f e i n , V a n G r a a f e il a n d

and M e s k i l l , Circuit Judges.

Action for declaratory judgment and injunction under

42 U.S.C. § 1983. The named plaintiff is a public school

teacher who was reprimanded for failing to wear a tie

5331

while teaching. After exhausting his administrative reme

dies, plaintiff began this action in the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Connecticut. Clarie, C.J.,

granted defendant’s motion for summary judgment on the

ground that plaintiff asserted no cognizable constitutional

interest.

Affirmed.

M a r t in A. G o u l d (Gould, Killian & Krechevsky,

of counsel), Hartford, Connecticut, for Ap

pellants.

B r ia n C l e m o w (Coleman H. Casey, Shipman &

Goodwin, of counsel), Hartford, Connecti

cut, for Appellees.

M e s k i l l , Circuit Judge:

Although this case may at first appear too trivial to

command the attention of a busy court, it raises important

issues concerning the proper scope of judicial oversight

of local affairs. The appellant here, Richard Brimley, is

a public school teacher reprimanded for failing to wear

a necktie while teaching his English class. Joined by the

teachers’ union, he sued the East Hartford Board of Edu

cation, claiming that the reprimand for violating the dress

code deprived him of his rights of free speech and pri

vacy. Chief Judge Clarie granted summary judgment for

the defendants. 405 F.Supp. 94 (D. Conn. 1975). A divided

panel of this Court reversed and remanded for trial. ------

F.2d —— , ------ (1976). At the request of a member of the

Court, a poll of the judges in regular active service was

taken to determine if the case should be reheard en banc.

A majority voted for rehearing. We now vacate the judg

ment of the panel majority and affirm the judgment of the

district court.

\ 5332

The facts are not in dispute. In February, 1972, the East

Hartford Board of Education adopted “Regulations For

Teacher Dress.” 1 At that time, Mr. Brimley, a teacher

of high school English and filmmaking, customarily wore

a jacket and sportshirt, without a tie. His failure to wear

a tie constituted a violation of the regulations, and he was

reprimanded for his delict. Mr. Brimley appealed to the

school principal and was told that he was to wear a tie

while teaching English, but that his informal attire was

proper during filmmaking classes. He then appealed to

the superintendent and the board without success, after

which he began formal arbitration proceedings, which

ended in a decision that the dispute was not arbitrable.

This lawsuit followed. Although Mr. Brimley initially

complied with the code while pursuing his remedies,2 he

has apparently returned to his former mode of dress.3

1 The entire dress code reads as follows:

The attire of professional employees during the hours when school

is in session must he judged in light of the following:

1. Dress should reflect the professional position of the employee.

2. Attire should he that which is commonly accepted in the com

munity.

3. It should be exemplary of the students with whom the pro

fessional employee works.

4. Clothing should he appropriate to the assignment of the em

ployee, such as slacks, and jersey for gym teachers.

In most circumstances the application of the above criteria to class

room teachers would call for jacket, shirt and tie for men and

dress, skirts, blouse and pantsuits for women.

I f an individual teacher feels that informal clothing such as sports

wear, would be appropriate to his or her teaching assignment, or

would enable him or her to carry out assigned duties more effec

tively, such requests may be brought to the attention of the Prin

cipal or Superintendent. An attempt should be made on all levels

to insure that the above principles are applied equitably and con

sistently throughout the school system.

2 See Arbitrator’s Opinion at 7.

3 Interview with Bichard Brimley, Hartford Courant, Feb. 28, 1977.

5333

The record does not disclose any disciplinary action against

him other than the original reprimand.

I.

In the vast majority of communities, the control of pub

lic schools is vested in locally-elected bodies.4 This com

mitment to local political bodies requires significant public

control over what is said and done in school. See Eisner

v. Stamford Board of Education, 440 F.2d 803, 807-08 (2d

Cir. 1971); Developments in the Law—Academic Free

dom, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 1045, 1052-54 (1968). It is not the

federal courts, but local democratic processes that are pri

marily responsible for the many routine decisions that are

made in public school systems. Accordingly, it is settled

that “ [cjourts do not and cannot intervene in the resolu

tion of conflicts which arise in the daily operation of school

systems and which do not directly and sharply impli

cate constitutional values.” Epperson v. Arkansas, 393

U.S. 97, 104 (1968) (footnote omitted).

Federal courts must refrain, in most instances, from

interfering with the decisions of school authorities. Even

though decisions may appear foolish or unwise, a federal

court may not overturn them unless the standard set forth

in Epperson is met. The Supreme Court recently empha

sized this point in Wood v. Strickland, 420 U.S. 308 (1975),

in which a high school’s summary disciplinary proceed

ings were challenged on due process grounds:

It is not the role of the federal courts to set aside

decisions of school administrators which the court may

view as lacking a basis in wisdom or compassion. . . .

The system of public education that has evolved in

this Nation relies necessarily upon the discretion and

4 See R. Campbell, L. Cunningham and R. McPhee, The Organization

and Control of American Schools, 164-70 (1965).

5334

judgment of school administrators and school board

members, and § 1983 was not intended to be a vehicle

for federal-court corrections of errors in the exercise

of that discretion which do not rise to the level of

violations of specific constitutional guarantees.

Id. at 326 (citations omitted).

Because the appellant’s clash with his employer has

failed to “directly and sharply implicate constitutional

values,” we refuse to upset the policies established by the

school board.

II.

Mr. Brim ley claims that by refusing to wear a necktie

he makes a statement on current affairs which assists him

in his teaching. In his brief, he argues that the following

benefits flow from his tielessness:

(a) He wishes to present himself to his students as

a person who is not tied to “ establishment conformity.”

(b) He wishes to symbolically indicate to his stu

dents his association with the ideas of the generation

to which those students belong, including the rejection

of many of the customs and values, and of the social

outlook, of the older generation.

(c) He feels that dress of this type enables him to

achieve closer rapport with his students, and thus

enhances his ability to teach.5 6

5 This final claim does not implicate the First Amendment. It is merely

an assertion that one teaching technique is to be preferred over another.

It has no more to do with a constitutional interest than would a claim

that closer "rapport” could be achieved by arranging students’ desks

in a circle rather than in rows.

5333

Appellant s claim, therefore, is that his refusal to wear a

tie is “symbolic speech,” and, as such, is protected against

governmental interference by the First Amendment.

We are required here to balance the alleged interest in

free expression against the goals of the school board in

requiring its teachers to dress somewhat more formally

than they might like. United States v. Miller, 367 F.2d 72,

80 (2d Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 386 U.S. 911 (1967). Com

pare Karst, Legislative Facts in Constitutional Litigation,

1960 Supreme Court Review 75, 77-81 with Emerson’

Towards a General Theory of the First Amendment, 72

Tale L. J. 877, 912-14 (1963). When this test is applied,

the school board’s position must prevail.

Obviously, a great range of conduct has the symbolic,

“speech-like” aspect claimed by Mr. Brimley. To state

that activity is “symbolic” is only the beginning, and not

the end, of constitutional inquiry. United States v. Miller,

supra, 367 F.2d at 78-79; see Note, Desecration of National

Symbols as Protected Political Expression, 66 Mich. L.

Rev. 1040, 1046 (1968); cf. People v. Cow gill, 274 Cal.App.

2d Supp. 923, 78 Cal. Rptr. 853, appeal dismissed, 396 U.S.

371 (1970) (Harlan, J., dissenting from dismissal). Even

though intended as expression, symbolic speech remains

conduct, subject to regulation by the state. As the Su

preme Court has stated in discussing the difference be

tween conduct and “speech in its pristine form” :

We emphatically reject the notion urged by appel

lant that the First and Fourteenth Amendments afford

the same kind of freedom to those who would communi

cate ideas by conduct such as patrolling, marching,

and picketing on streets and highways, as these amend

ments afford to those who communicate ideas by pure

speech. . . . We reaffirm the statement of the Court

in Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co. [336 U.S.

5336

490, 502 (1949)], that “it has never been deemed an

abridgement of freedom of speech or press to make a>

course of conduct illegal merely because the conduct

was in part initiated, evidenced, or carried out by

means of language, either spoken, written, or printed.”

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 555-56 (1965). The rule of

Cox, which involved a mixture of activity and speech, ap

plies with even greater force in a ease such as this one,

where only conduct is involved. See United States v.

O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 376 (1968) (burning of draft card

as political protest not protected).

As conduct becomes less and less like “pure speech” the

showing of governmental interest required for its regula

tion is progressively lessened. See Alfange, Jr., Free

Speech and Symbolic Conduct: The Draft Card Burning

Case, 1968 Supreme Court Review 1, 22-27; Note, Sym

bolic Speech, 43 Fordham L. Rev. 590, 592-93 (1975); Note,

Symbolic Conduct, 68 Colum. L. Rev. 1091, 1121-25 (1968).

In those cases where governmental regulation of expres

sive conduct has been struck down, the communicative in

tent of the actor was clear and “closely akin to ‘pure

speech,’ ” Tinker v. Des Moines School District, 393 U.S.

503, 505 (1969). Thus, the First Amendment has been

held to protect wearing a black armband to protest the

Vietnam War, Tinker v. Des Moines School District, su

pra/ burning an American Flag to highlight a speech de

nouncing the government’s failure to protect a civil rights

leader, Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576 (1969), or quietly

6 The Tirilcer court was careful to distinguish a prohibition on the

wearing of an armband from a dress code:

The problem posed by the present case does not relate to regula

tion of the length of skirts or the type of clothing, to hair style,

or deportment. . . . Our problem involves direct, primary First

Amendment rights akin to "pure speech.”

393 U.S. at 507-08.

5337

refusing to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, Iiusso v. Cen

tral School District, 469 F.2d 623 (2d Cir. 1972), cert, de

nied, 411 U.S. 932 (1973).

In contrast, the claims of symbolic speech made here are

vague and unfocused. Through the simple refusal to wear

a tie, Mr. Brimley claims that he communicates a compre

hensive view of life and society. It may well be, in an age

increasingly conscious of fashion, that a significant portion

of the population seeks to make a statement of some kind

through its clothes. See Q. Bell, On Human Finery (2d ed.

1976). However, Mr. Brimley’s message is sufficiently

vague to place it close to the “conduct” end of the “ speech-

conduct” continuum described above. Cf. Henkin, The

Supreme Court 1967 Term—Foreword: On Drawing Lines,

82 Harv. L. Rev. 63, 76-81 (1968). While the regulation of

the school board must still pass constitutional muster, the

showing required to uphold it is significantly less than if

Mr. Brimley had been punished, for example, for publicly

speaking out on an issue concerning school administration.

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 (1968); see

Richards v. Thurston, 424 F.2d 1281 (1st Cir. 1970).

III.

At the outset, Mr. Brimley had other, more effective

means of communicating his social views to his students.

He could, for example, simply have told them his views on

contemporary America; if he had done this in a temperate

way, without interfering with his teaching duties, we would

be confronted with a very different First Amendment case.

See Van Alstyne, The Constitutional Rights of Teachers

and Professors, 1970 Duke L. ,T. 841, 856. The existence of

alternative, effective means of communication, while not

conclusive, is a factor to be considered in assessing the

validity of a regulation of expressive conduct. Connecticut

5338

State Fed’n of Teachers v. Board of Education, 538 F.2d

471, 481-82 (2d Cir. 1976).

Balanced against appellant’s claim of free expression

is the school board’s interest in promoting respect for au

thority and traditional values, as well as discipline in the

classroom, by requiring teachers to dress in a professional

manner. A dress code is a rational means of promoting

these goals.7 As to the legitimacy of the goals themselves,

there can be no doubt. In James v. Board of Education,

Chief Judge Kaufman stated:

The interest of the state in promoting the efficient

operation of its schools extends beyond merely secur

ing an orderly classroom. Although the pros and cons

of progressive education are debated heatedly, a prin

cipal function of all elementary and secondary edu

cation is indoctrinative—whether it be to teach the

ABC’s or multiplication tables or to transmit the basic

values of the community.

461 F.2d 566, 573 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1042

(1972). See also Miller v. School District, 495 F.2d 658,

664 (7th Cir.) (Stevens, J .)8

7 The school board made an effort to limit the reach of the dress code

to classes in which the values it promoted were believed to be sig

nificant. Thus, Mr. Brimley was required to wear a tie while teaching

a conventional English class, but not while giving an "alternative” class

in filmmaking. Whatever the merits of this distinction, it demonstrates

that the board's action was taken in good faith, and was not merely

an attempt to make teachers conform.

8 Appellant’s position on this point is somewhat inconsistent. He claims

that his tielessness carries a message of importance to his students, but

belittles the board’s belief that ties have any impact on classroom

atmosphere. Professor Archibald Cox, the arbitrator in the earlier pro

ceedings, was far more sympathetic to the board’s position. In his

opinion, he stated:

The School Board feels no less deeply and strongly that the atmo

sphere of the classroom and attitude of the students are sufficiently

5339

This balancing test is primarily a matter for the school

board. Were we local officials, and not appellate judges,

we might find Mr. Brimley’s arguments persuasive. How

ever, our role is not to choose the better educational policy.

We may intervene in the decisions of school authorities

only when it has been shown that they have strayed outside

the area committed to their discretion. I f Mr. Brimley’s

argument were to prevail, this policy would be completely

eroded. Because teaching is by definition an expressive

activity, virtually every decision made by school authori

ties would raise First Amendment issues calling for federal

court intervention.

The very notion of public education implies substantial

public control. Educational decisions must be made by

someone; there is no reason to create a constitutional pref

erence for the views of individual teachers over those of

their employers.* 9 As Judge Mulligan wrote for a unani-

affected by teacher’s clothing for it to require a necktie and

jacket.

Arbitrator’s Opinion at 7.

9 Specifically, there is no reason to prefer Mr. Brimley’s notion of

what constitutes a "professional image” over that of the school board,

even if the style he has chosen is acceptable in most schools. In Tardif

v. Quinn, 545 I\2d 761 (1st Cir. 1976), a school teacher was fired for

wearing short skirts. The court stated:

The [district] court, having taken a view, found that plaintiff’s

dresses, which came "half-way down [her] thigh,” were "comparable

in style to dresses worn by young, respectable professional women

during the years when the plaintiff was teaching.” It further found

that her dresses in fact "had no startling or adverse effect on her

students or on her effectiveness as a teacher.”

We will assume that by this finding the court meant that plain

tiff's dress length was within reasonable limits, and we further

assume that this finding was warranted. On the other hand, the

court’s independent judgment as to the impact and propriety of

plaintiff’s dress does not amount to a finding that defendants’

objections to the length were irrational in the context of school

administration concerns.

Id. at 763.

5340

mous panel in Presidents Council v. Community School

Board, 457 F.2d 289 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 998

(1972):

Academic freedom is scarcely fostered by the intrusion

of three or even nine federal jurists making curricu

lum or library choices for the community of scholars.

When the court has intervened, the circumstances have

been rare and extreme and the issues presented totally

distinct from those we have here.

Id. at 292.

In that case, we upheld the action of a school board

in limiting library access and forbidding further pur

chase of a book it found objectionable. First Amend

ment rights were implicated far more clearly there than in

the instant ease. President’s Council clearly indicates the

wide scope of school board discretion. When First Amend

ment rights are truly in jeopardy as a result of school

board actions, this Court has not hesitated to grant relief.

See James v. Board of Education, supra; Russo v. Central

School District, supra. In contrast to Janies and Russo,

the First Amendment claim made here is so insubstantial

as to border on the frivolous.10 We are unwilling to expand

First Amendment protection to include a teacher’s sar

torial choice.

IV.

Mr. Brimley also claims that the “liberty” interest

grounded in the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment protects his choice of attire. Cf. Griswold v.

10 At least three Circuits have rejected the claim that long hair is ex

pressive conduct entitled to First Amendment protection. Richards v.

Thurston, supra; Freeman v. Flake, 448 F.2d 258 (10th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 405 TJ.S. 1032 (1972); Karr v. Schmidt, 460 F.2d 609

(5th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied, 409 TJ.S. 989 (1972).

5341

Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). This claim will not with

stand analysis.

The Supreme Court dealt with a similar claim in Kelley

v. Johnson, 425 U.S. 238 (1976). That case involved a chal

lenge to the hair-grooming regulations of a police depart

ment. The Court was careful to distinguish privacy claims

made by government employees from those made by mem

bers of the public:

Respondent has sought the protection of the Four

teenth Amendment, not as a member of the citizenry

at large, but on the contrary as an employee of the

police force of Suffolk County, a subdivision of the

State of New York. While the Court of Appeals made

passing reference to this distinction, it was thereafter

apparently ignored. We think, however, it is highly

significant. In Pickering v. Board of Education, 391

U.S. 563, 568 (1968), after noting that state employ

ment may not be conditioned on the relinquishment of

First Amendment rights, the Court stated that “ [a]t

the same time it cannot be gainsaid that the State has

interests as an employer in regulating the speech of its

employees that differ significantly from those it pos

sesses in connection with regulation of the speech of

the citizenry in general.” More recently, we have sus

tained comprehensive and substantial restrictions upon

activities of both federal and state employees lying at

the core of the First Amendment. Civil Service Comm’n

v. Letter Carriers, 413 U.S. 548 (1973); Broadrick

v. Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 601 (1973). If such state regu

lations may survive challenges based on the explicit

language of the First Amendment, there is surely even

more room for restrictive regulations of state em

ployees where the claim implicates only the more gen-

5342

eral contours of the substantive liberty interest

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Id. at 244-45.

The same distinction applies here. The regulation in

volved in this case affects Mr. Brimley in his capacity as a

public school teacher.11 Of course, as he points out, the

functions of policemen and teachers differ widely. Regula

tions well within constitutional bounds for one occupation

might prove invalid for another. Nonetheless, we can see

no reason why the same constitutional test should not

apply, no matter how different the results of their con

stitutional challenges. See Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S.

493, 499-500 (1967).1S

Kelley goes on to set forth the standard to be applied in

such cases:

We think the answer here is so clear that the District

Court was quite right in the first instance to have dis

missed respondent’s complaint. Neither this Court, the

Court of Appeals, nor the District Court is in a posi

tion to weigh the policy arguments in favor of and

against a rule regulating hairstyles as a part of regu

lations. governing a uniformed civilian service. The

constitutional issue to be decided by these courts is

whether petitioner’s determination that such regula-

11 It is not only appellant’s status as a public employee, but the special

needs of the school environment that serve to justify the board’s action.

See Grayned v. City of Boclcford, 408 U.S. 104 (1972).

12 In Quinn v. Muscare, 425 U.S. 560 (1976), the Supreme Court, in

considering the validity of the Chicago Fire Department’s "personal

appearance regulation” stated: "Kelley v. Johnson renders immaterial

the District Court’s factual determination regarding the safety justifi

cation for the Department’s hair regulation about which the Court of

Appeals expressed doubt.” Id. at 562-63. Although firemen are, like

policemen, a uniformed service, Quinn points towards a general appli

cation of Kelley to all public employees.

5343

tions should he enacted is so irrational that it may he

branded “ arbitrary,” and therefore a deprivation of

respondent’s “ liberty” interest in freedom to choose

his own hairstyle. Williamson v. Lee Optical Co., 348

U.S. 483, 487-88 (1955).

425 U.S. at 247-48. If Mr. Brimley has any protected inter

est in his neckwear, it does not weigh very heavily on the

constitutional scales. As with most legislative choices, the

hoard’s dress code is presumptively constitutional.13 It is

justified by the same concerns for respect, discipline and

traditional values described in our discussion of the First

Amendment claim. Accordingly, appellant has failed to

carry the burden set out in Kelley of demonstrating that

the dress code is “ so irrational that it may be branded

‘arbitrary,’ ” and the regulation must stand.

The rights of privacy and liberty in which appellant

seeks refuge are important and evolving constitutional

doctrines. To date, however, the Supreme Court has ex

tended their protection only to the most basic personal

decisions. See Carey v. Population Services Int’l., 45

U.S.L.W. 4601, 4602-03 (U.S. June 9, 1977). Nor has the

Supreme Court been quick to expand these rights to new

fields. See Doe v. Commonwealth’s Attorney for the City

of Richmond, 425 U.S. 901 (1976), aff’g mem., 403 F.Supp.

13 The exceptions to this ordinary test in constitutional litigation remain

those of Justice Stone’s celebrated Garolene Products footnote; the state

must carry the burden of proof when it discriminates against an insular

minority or burdens the exercise of a "fundamental” right. United

States v. Carolene Products, 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4 (1938); Massachu

setts Board of Retirement v. Murgia, 427 U.S. 307, 312-14 (1976);

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 634 (1969) ; compare id. at. 658-

663 (Harlan, J. dissenting); see Gunther, The Supreme Court, 197]

Term— Foreword: In Search of Evolving Doctrine on a Changing Court:

A Model For a Newer Equal Protection, 86 Harv. L. Eev. 1 (1972).

As Kelley makes clear, appellant’s right to dress as he pleases, if it

exists at all, is far from "fundamental” in the constitutional sense.

5344

1199 (E.D. Ya. 1975) (three judge court) (sodomy statute

is constitutional as applied to private, consensual homo

sexual behavior). As with any other constitutional pro

vision, we are not given a “roving commission” to right

wrongs and impose our notions of sound policy upon

society. There is substantial danger in expanding the

reach of due process to cover cases such as this. By bring

ing trivial activities under the constitutional umbrella, we

trivialize the constitutional provision itself. If we are to

maintain the vitality of this new doctrine, we must be

careful not to “cry wolf” at every minor restraint on a

citizen’s liberty. See Whelan v. Roe, 45 U.S.L.W. 4166,

4168 (U.S. Feb. 22, 1977).

The two other Courts of Appeals which have considered

this issue have reached similar conclusions. In Miller v.

School District, 495 F.2d 658 (7th Cir. 1974), the Seventh

Circuit upheld a grooming regulation for teachers. Mr.

Justice Stevens, then a member of the Court of Appeals,

wrote:

Even if we assume for purposes of decision that

an individual’s interest in selecting his own style

of dress or appearance is an interest in liberty, it is

nevertheless perfectly clear that every restriction on

that interest is not an unconstitutional deprivation.

From the earliest days of organized society, no

absolute right to an unfettered choice of appearance

has ever been recognized; matters of appearance and

dress have always been subjected to control and reg

ulation, sometimes by custom and social pressure,

sometimes by legal rules. A variety of reasons justify

limitations on this interest. They include a concern

for public health or safety, a desire to avoid specific

forms of antisocial conduct, and an interest in pro

tecting the beholder from unsightly displays. Nothing

5345

more than a desire to encourage respect for tradition,

or for those who are moved hy traditional ceremonies,

may be sufficient in some situations. Indeed, even an

interest in teaching respect for (though not neces

sarily agreement with) traditional manners, may lend

support to some public grooming requirements. There

fore, just as the individual has an interest in a choice

among different styles of appearance and behavior,

and a democratic society has an interest in fostering

diverse choices, so also does society have a legitimate

interest in placing limits on the exercise of that choice.

495 F.2d at 684 (footnotes omitted). The First Circuit

reached the same result in Tardif v. Quinn, 545 F.2d 761

(1st Cir. 1976), where a school teacher was dismissed for

wearing short skirts. In upholding the action of the school

district, the Court stated:

[W ]e are not dealing with personal appearance in

what might he termed an individual sense, hut in a

bilateral sense—a contractual relationship. Whatever

constitutional aspect there may be to one’s choice of

apparel generally, it is hardly a matter which falls

totally beyond the scope of the demands which an

employer, public or private, can legitimately make

upon its employees. We are unwilling to think that

every dispute on such issues raises questions of con

stitutional proportions which must stand or fall, de

pending upon a court’s view of who was right.

545 F.2d at 763 (citations omitted).

Both Miller and Tardif are stronger cases for the plain-

tiff’s position than the instant case.14 Both involved dis-

14 The claim that such regulations violate the Constitution has fared

equally badly in the state courts. See, e.g., Morrison v. Hamilton County

5346

missals rather than, as here, a reprimand. Moreover,

Miller involved a regulation of hair and beards, as well

as dress. Thus, Miller was forced to appear as his em

ployers wished both on and off the job. In contrast, Mr.

Brimley can remove his tie as soon as the school day ends.

If the plaintiffs in Miller and Tardif could not prevail,

neither can Mr. Brimley.

Each claim of substantive liberty must be judged in

the light of that case’s special circumstances. In view of

the uniquely influential role of the public school teacher

in the classroom, the board is justified in imposing this

regulation. As public servants in a special position of

trust, teachers may properly be subjected to many restric

tions in their professional lives which would be invalid if

generally applied. See James v. Board of Education, 461

F.2d 566, 573 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1042 (1972).

We join the sound views of the First and Seventh Cir

cuits, and follow Kelley by holding that a school board

may, if it wishes, impose reasonable regulations govern

ing the appearance of the teachers it employs. There being

no material factual issue to be decided, the grant of sum

mary judgment is affirmed.

O a k e s , Circuit Judge (with whom Judge Smith concurs)

(dissenting):

In an area as fraught with uncertainty as constitutional

law, it is particularly incumbent upon judges to explain

carefully each analytical step they are making toward a

particular conclusion and to evaluate searchingly each con-

Board of Education, 494 S.W.2d 770 (Tenn.), cert, denied, 414 U.S.

1044 (1973) ; Blanchet v. Vermilion Parish School Board, 220 So.2d

534 (La.App.), writ denied, 254 La. 17, 220 So.2d 68 (1969); hut

see Finot v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 250 Cal.App.2d 189,

58 Cal. Bptr. 520 (1967).

5347

tention put forward by the parties. Reasoned analysis is

particularly critical in a case of this nature, in which a

school board, carrying the legitimacy of popular election,

is claimed to infringe upon the liberty and expression in

terests of an individual employee who after exhausting

mediation remedies seeks redress, in the time-tested con

stitutional framework, from the institution that has histori

cally been charged with the task of guarding the individ

ual’s most precious freedoms against undue infringement

by the majority. The en banc opinion, by downplaying the

individual’s interests here as “ trivial” and giving weight

to a school board interest not advanced as such, adds, it

seems to me, an unfortunate chapter to this history. I dis

sent, with regret, not so much at the difference in value

judgments that evidently underlies the majority’s opinion

but because the case apparently involves so little in the

majority’s view.

The panel majority opinion sought to follow a rather

straightforward analysis: (1) appellant Brimley has a

Fourteenth Amendment liberty interest in his personal

appearance; (2) appellant also has a First Amendment

interest, involving the right to teach; (3) the school board

asserts three interests, two of which are invalid because

ultra vires and the third of which (discipline) is not ra

tionally furthered by this teacher dress code; (4) balanc

ing these interests, appellant prevails. This dissent will

discuss in the above order the treatment of each of these

points in the en banc majority opinion.

First, since the en banc majority purports to follow Kel

ley v. Johnson, 425 U.S. 238 (1976), it presumably assumes,

as did the Court in Kelley, id. at 244, that appellant does

have a Fourteenth Amendment liberty interest in his per

sonal appearance, even if not a “fundamental” one. If the

school board cannot put a proper purpose that is ration-

5348

ally related to its regulation on the other side of the scales,

this liberty interest alone, however “trivial,” will carry the

day for appellant. See Tardif v. Quinn-, 545 F.2d 761, 764

(1st Cir. 1976), quoted in panel majority op., ante, ------

F.2d at ------ n.9; Perry, Substantive Due Process Revis

ited: Re-flections On (And Beyond) Recent Cases, 71 Nw.

IT. L. Rev. 417, 427-30 (1976).

Second, the en banc majority baldly states in a footnote,

without citation of authority, that appellant’s asserted

First Amendment right to teach is not a constitutionally

cognizable interest. A n te,------F.2d a t ------- n.5. But this

established constitutional right will not disappear because

the en banc majority simply chooses to ignore it. It exists

in full-blown form at the college level. See, e.g., Keyishian

v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 603 (1967); Barenblatt

v. United States, 360 TT.S. 109, 129 (1959); Sweezy v. Neiv

Hampshire, 354 IT.S. 234, 250 (1957) (plurality opinion).

Teaching methods in public high schools are in many in

stances protectible under the First Amendment, as the

authorities cited by the panel majority demonstrate, ante,

------F.2d a t ------- , slip op. at 1864, and as more recent au

thorities continue to affirm, see Minarcini v. Strongsville

City School District, 541 F.2d 577, 582 (6th Cir. 1976);

Cary v. Board of Education, 427 F. Supp. 945 (D. Colo.

1977). While serious questions arise in measuring the

parameters of the right in the context of public high school

teaching, as the panel majority fully recognized, ante, ——-

F.2d a t ------ , slip op. at 1865, answers to those questions

are not aided by the ostrich-like presumption that they do

not exist.

To be sure, the en banc majority does discuss at length

symbolic speech, a concept quite separate from the right to

teach. I do not disagree with the majority’s conclusion

that, to the limited extent that appellant is making a. sym

bolic speech claim, it is close to the conduct end of the

5349

speech-conduct continuum. But even this conclusion still

leaves appellant with a First Amendment constitutional

interest that can be overcome only by a state regulation

rationally related to a valid purpose.

Third, the en banc majority abandons two of the inter

ests asserted by the school board,1 presumably agreeing

with the panel majority that they are outside the scope of

the board’s statutory powers, panel majority op., ante,

—— F.2d at ------ , slip op. at 1867-68; concurs with the

panel in identifying a third interest; and makes up a fourth

of its own. I agree fully with the en banc majority that

the third and last interest asserted by the board—involving

discipline, respect, and decorum in the classroom—is a

proper one. The point made by the panel majority was

that this interest did not seem furthered in any rational

way by the teacher dress code at issue here. The en banc

majority opinion makes no attempt whatever to address

this critical analytical point.2 Instead, its logic appears to

be: “The interest is furthered by the dress code because

These were establishing "a professional image for teachers” and pro

moting "good grooming among students.” Ante, ------- F.2d at ____ ,

slip op. at 1866.

The panel majority opinion dealt with this interest as follows:

It is far from clear . . . that a tie code like that in issue here

has any connection with respect or discipline. Indeed, appellant

puts forward the seemingly more reasonable proposition, which we

must accept at this stage, that being tieless helps him to maintain

his students’ respect. Teenagers, who are so often rebellious against

authority, may find a tieless teacher to be a less remote, more

contemporary individual with whom they can more easily interact

and hence to whom they are better prepared to listen with care

and attention. It is highly questionable, and certainly not estab

lished on this motion for summary judgment, that the Board's

valid end of promoting discipline is substantially, or even incre

mentally, furthered by its tie regulation.

Ante, F.2d at , slip op. at 1868-69 (footnotes omitted). I

see no reason to alter this view at this stage, which is still one of

summary judgment.

5350

the school board says that it is.” Whatever argument

might he made that the school board’s ends are furthered

by its means, the en banc majority does not make it, and

certainly the essential connection between means and ends

is not here self-evident.8 The majority’s less than rigorous

inquiry is well short of the least demanding formulation of

the inquiry necessary to determine the rationality of a

state regulation. See, e.g., Maher v. Roe, 45 U.S.L.W. 4787,

4791 (U.S. June 20, 1977).

The en banc majority also makes up an interest, respect

for traditional values,3 4 that is not put forward by the

school board. I understand it to be settled constitutional

doctrine that only objectives articulated by the State are

to be used in considering whether a regulation is rational.

See, e.g., Massachusetts Board of Retirement v. Murgia,

427 U.S. 307, 314-15 & n.6 (1976) (per curiam) (“ the pur

pose identified by the State” ) ; Johnson v. Robison, 415

U.S. 361, 376 (1974) (“whether there is . . . a fair and sub

stantial relation to at least one of the stated purposes” ) ;

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1,17 (1973); McGinnis v. Royster, 410 U.S. 263, 276-77

3 By contrast, in Kelley v. Johnson, 425 U.S. 238 (1976), the connec

tion was explicitly made between the hair regulation at issue and the

state interests of discipline, esprit de corps, and uniformity in the

police force.

The majority’s statement, ante, ------- F.2d at ------- n.12, that Quinn

v. Muscare, 425 U.S. 560 (1976) (per curiam), "points toward a gen

eral application of Kelley to all public employees” is simply not correct.

Quinn involved a fire department appearance regulation, and the same

state interests detailed in Kelley were involved, as the Court in Quinn

recognized, id. at 562. Even the en bane majority does not assert that

the state has any interest in the discipline, esprit de corps, or uni

formity of its teachers. Different state interests are involved here, and

they must be balanced against appellant’s asserted rights on their own

merits. See Perry, Substantive Due Process Revisited: Reflections On

(And Beyond) Recent Cases, 71 Nw. U. L. Rev. 417, 427-30 (1976).

4 Respect for "authority” is also mentioned, but I assume that this

refers either to the maintenance of discipline or to the inculcation of

a traditional value.

5351

(1973). See also Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 U.S. 498, 520-

21 & n .ll (1975) (Brennan, J dissenting); Gunther, The

Supreme Court, 1971 Term — Foreword: In Search of

Evolving Doctrine on a Changing Court: A Model for a

Newer Equal Protection, 86 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1972). I had

imagined that the day when courts supplied imaginary

purposes for state regulations had passed.

The reason that the school board never asserted this

interest, of course, is clear: the tie requirement is not

related in any rational way to the admitted responsibility

of a school board to inculcate traditional values in its stu

dents. The en banc majority does not enlighten us as to

which value it has in mind, hut in any event a necktie is a

mere conventional fashion, with no connection of which I

am aware to any traditional value. I fear that the major

ity simply confuses traditional values with mindless ortho

doxy. The inculcation of the latter, of course, as the panel

majority pointed out, is constitutionally forbidden. Ante,

------ F.2d at ------n.8, slip op. at 1869 n.8.

Finally, the process by which the en banc majority bal

ances the interests involved is defective. As Professor

Gunther has pointed out, “ responsible” balancing requires

careful identification and separate evaluation of “each

analytically distinct ingredient of the contending inter

ests.” Gunther, supra, 86 Harv. L. Rev. at 7. This the

en banc majority fails to do. Rather, at the end of the

majority’s discussion of each of appellant’s two interests,

it simply states that a teacher dress code rationally pro

motes the two interests identified as those of the school

board and hence overcomes the interests of appellant.

Even if a rational connection between the tie regulation

and board interests did exist, as to which see text at notes

2-3 supra, the majority’s assumption that both of appel

lant’s interests can be disposed of separately under a ra-

5352

tional relationship test is in my view not well-founded. If

only a Fourteenth Amendment liberty interest were at

stake, such a test might be the proper one to apply. See

Kelley v. Johnson, supra; Tardif v. Quinn, supra; Miller v.

School District No. 167, 495 F.2d 658 (7th Cir. 1974) (Ste

vens, J .).5 When, instead, a First Amendment interest is as

serted, there must in addition be some inquiry by the court

into whether the state had available “ ‘less drastic means

for achieving the same basic purpose.’ ” Wooley v. May

nard, 45 U.S.L.W. 4379, 4382 (U.S. Apr. 20, 1977), ([noting

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488 (1960); see James v.

Board of Education, 461 F.2d 566, 574, 575 n.22 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1042 (1972), quoted in panel major

ity op., ante,------F.2d a t------- , slip op. at 1871. The neces

sary implication of James is that a less drastic means test

must be applied even when it is a public employee who is

asserting the First Amendment claim. See 461 F.2d at

571-72 & n.13.

When an individual has more than one constitutional

interest at stake, at least when one involves the First

Amendment, a higher degree of scrutiny is required.6 In

Police Department of the City of Chicago v. Mosley, 408

U.S. 92, 98-99 (1972), for example, the Supreme Court

“carefully scrutinized” justifications for selective prohi

bitions against picketing near schools under the equal

5 The en banc majority’s claim that Miller and Tardif were stronger

cases than the instant one for appellant’s position, because "[b]oth

involved dismissals rather than, as here, a reprimand,” ante, ------ F.2d

at ------ , is groundless. The only reason that appellant was not dis

missed is because, rather than defy the tie code, he chose to comply

with it and make his challenge through the proper legal channels. See

panel majority op., ante, ------ F.2d at -------, slip op. at 1858.

6 This is a common technique in the equal protection area, where "strict

scrutiny” is mandated when a claim of unequal treatment is combined

with a claim that a fundamental interest is implicated. This is not

to say, however, that appellant’s interest here is "fundamental” in the

equal-protection-analysis sense or that "strict scrutiny” is required.

5353

protection clause because expressive conduct within the

protection of the First Amendment was involved; the gov

ernmental interest served by the regulation was therefore

required to be “substantial.” Only in this way, with the

interests on each side aggregated rather than viewed sep

arately, can any meaningful balancing take place. If, in

stead, the en banc majority’s pro forma, sequential “bal

ancing” is all that is required, a new and dimmer day is

dawning, at least for public employees, and perhaps more

broadly for all forms of constitutional adjudication involv

ing individual rights.

I think the en banc majority gives away the real basis

for its simple bow in the direction of balancing when it

suggests that to hold otherwise is to give federal judges

“ a ‘roving commission’ to right wrongs and impose our

notions of sound policy upon society.” Ante, -------F.2d at

—— . I had always thought that the federal courts were

given by Article III of the Constitution and the doctrine

of judicial review not a “roving commission” but a sworn

duty to interpret and uphold that document equally for

all who come before them. Constitutional doctrines have

evolved that we may be aided in this awesome task, and,

in my view, we must strive with as much intellectual clar

ity as possible to apply those doctrines to the case at hand.

It is when we do not do this that we are truly imposing

our own notions of sound policy on society, for our con

clusions are then rooted in the shifting sands of our own

prejudices and not in the rich, well-furrowed soil of the

Document we are sworn to interpret. An individual’s rights

in this sense can never be “trivial.” They are constitu

tionally based or they are not; they are opposed by rational

state interests or they are not; they prevail in the balanc

ing process or they do not. Here, they should prevail.

I dissent.

5354

480— 8-22-77 . USCA— 4221

MEILEN PRESS INC., 445 GREENWICH ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013, (212) 966-4177