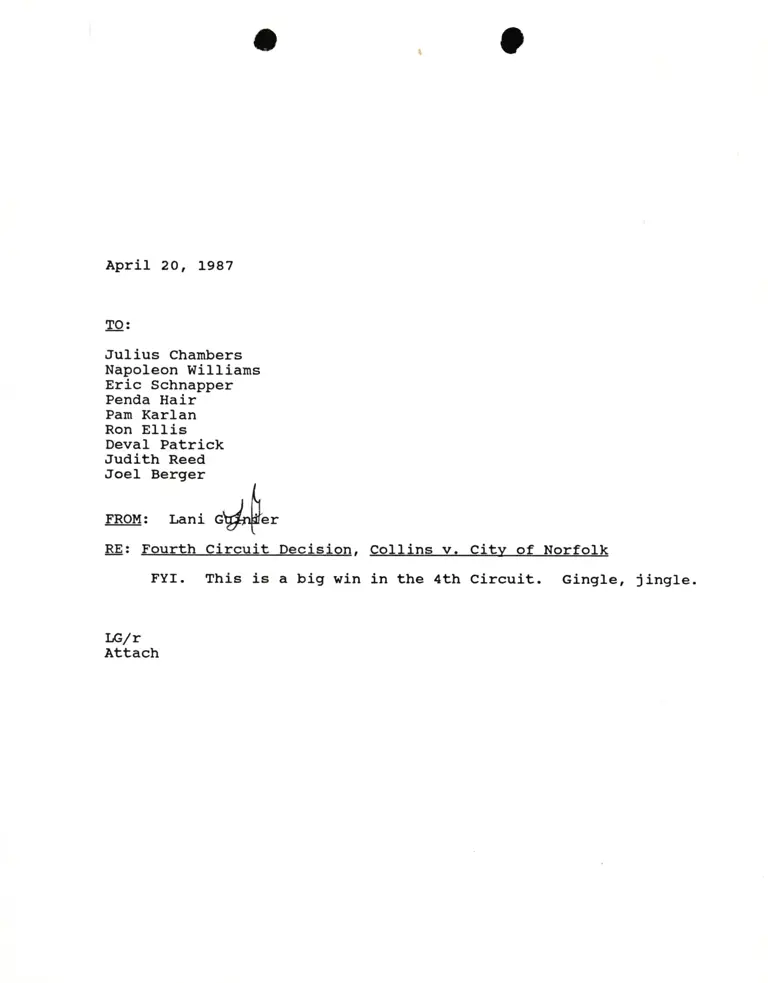

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Chambers, Williams, Schnapper, Hair, Karlan, Ellis, Patrick, Reed, and Berger Re Fourth Circuit Decision, Collins v. City of Norfolk

Correspondence

April 20, 1987

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Chambers, Williams, Schnapper, Hair, Karlan, Ellis, Patrick, Reed, and Berger Re Fourth Circuit Decision, Collins v. City of Norfolk, 1987. 96c7cd86-ea92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d53782a7-8e98-4673-b50d-50e5e6d29507/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-chambers-williams-schnapper-hair-karlan-ellis-patrick-reed-and-berger-re-fourth-circuit-decision-collins-v-city-of-norfolk. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Aprll 20, 1987

TQ:

JulLus Chanbers

Napoleon Wi}lians

Eric Schnapper

Penda Hair

Pam Karlan

Ron Ellie

Deval Patrick

iludtth Reed

iloe1 Berger

EBeu: r,ani #"'

BE: Fourth Circul-t DecisLon, CollLne v. Citv of Norfolk

FYI. Thla ie a blg wln ln the 4th circuLt. Glngle, Jlngle.

w/r

Attach