Rosado v Wyman Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1968

47 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rosado v Wyman Brief Amici Curiae, 1968. 7a6cf242-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d542ecac-a299-4d25-bc27-43fd7117a9ab/rosado-v-wyman-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 18, 2026.

Copied!

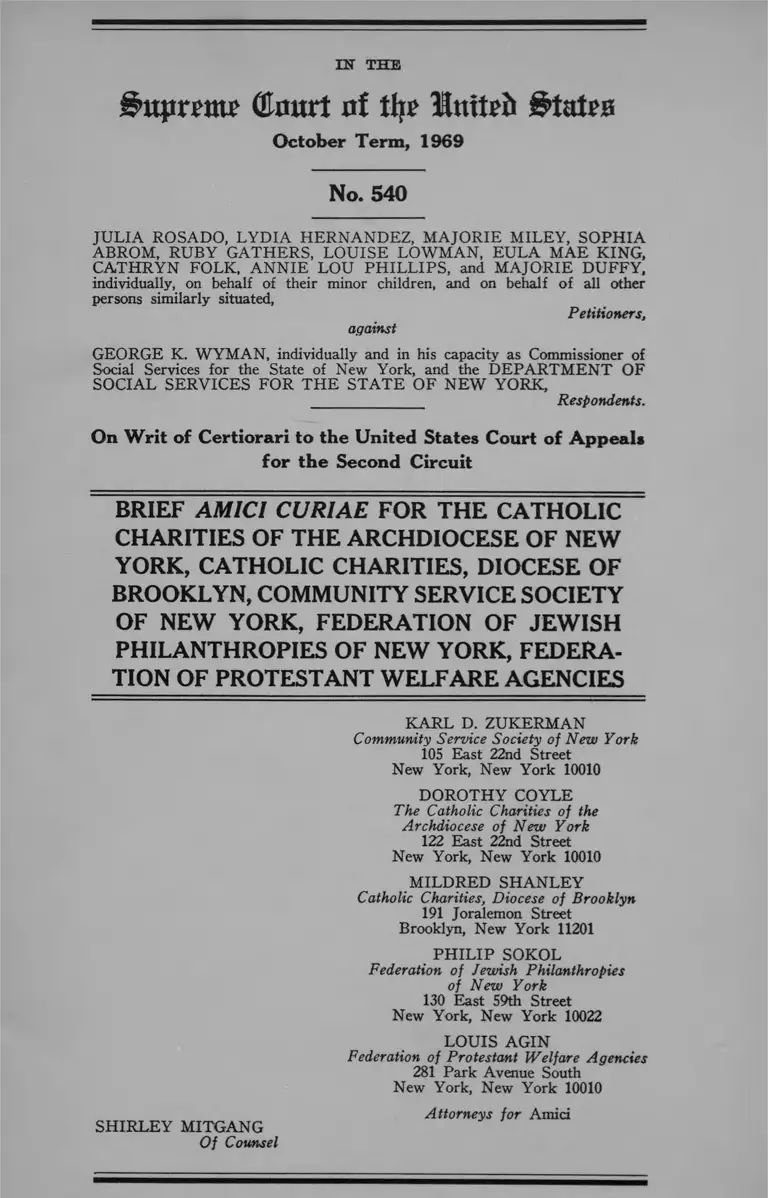

IN THE

Supreme Court of % luttrfc ^tatro

October Term, 1969

No. 540

JU LIA ROSADO, L Y D IA H ERN AN DEZ, M AJO RIE M ILEY, SO PH IA

ABROM , R U B Y GATH ERS, LOU ISE LO W M A N , E U LA M AE KING,

C A T H R Y N FOLK, A N N IE LOU PH ILLIPS, and M AJORIE DUFFY,

individually, on behalf of their minor children, and on behalf o f all other

persons similarly situated,

Petitioners,

against

GEORGE K. W Y M A N , individually and in his capacity as Commissioner of

Social Services for the State of New York, and the D E P A R T M E N T OF

SOCIAL SERVICES FO R T H E S T A T E O F N E W YORK,

________________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR THE CATHOLIC

CHARITIES OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF NEW

YORK, CATHOLIC CHARITIES, DIOCESE OF

BROOKLYN, COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY

OF NEW YORK, FEDERATION OF JEWISH

PHILANTHROPIES OF NEW YORK, FEDERA

TION OF PROTESTANT WELFARE AGENCIES

SH IR LE Y M ITGAN G

Of Counsel

K A R L D. ZU K ERM AN

Community Service Society of New York

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

D O R O T H Y COYLE

The Catholic Charities of the

Archdiocese of N ew York

122 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

M ILDR ED SH A N LE Y

Catholic Charities, Diocese of Brooklyn

191 Joralemon Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

P H IL IP SOKOL

Federation of Jewish Philanthropies

of N ew York

130 East 59th Street

New York, New York 10022

LOU IS AG IN

Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies

281 Park Avenue South

New York, New York 10010

Attorneys for A m id

T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S

page

I nterest of the Amici ........................................................... 2

S ummary of the A rgument ................................................ 4

P oint I—Aware of the well-documented body of em

pirical and theoretical evidence that a real con

nection exists between poverty and individual,

familial and societal pathology, Congress initi

ated the Aid to Dependent Children (now known

as Aid to Families with Dependent Children)

program in 1935 and amended it in 1967 to render

it more effective ...................................................... 6

A. Relationship of Poverty to Pathology ........ 6

1. Physical Health ......................................... 7

2. Mental Health .......................................... 9

3. Child Development ..................................... 15

4. Family Life ................................................ 18

5. Social Alienation ....................................... 22

B. Congressional Purpose and Intent ................ 23

C. Congressional Knowledge of Relationship

Between Poverty and Social Ills .................. 27

P oint II—The passage of Section 131-a of the New

York Social Services Law rendered the New York

state plan for AFDC non-compliant with Sec

tion 602(a) (23) of Title 42 of the United States

Code, part of the Social Security Act

P oint III—Levels of AFDC grants had been grossly

insufficient to meet the needs of the recipients and

the effects of the reductions caused by Section

131-a of the New York Social Services Law have

incalculably worsened the plight of the recipients

Conclusion ...................................................

30

32

39

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Statutes:

PAGE

P.L. 89-239 ....................................................................... 37

P.L. 89-749 ....................................................................... 37

42 U.S.C. 601 ................................................................... 24

42 U.S.C. 602(a) (23) ...................................................passim

42 U.S.C. 1314 ................................................................. 32

N.Y. S ess. L aws 1969, ('ll. 184, §1 ............................... 30

N.Y. Soc. S erv. L aw §131-a ......................................passim

N.Y. Soc. Serv. L aw §358 ................................................... 24

Other Authorities:

Address by Herbert Bienstock, Conference on the Di

mensions of Poverty, American Statistical Asso

ciation, New York Chapter, March 11, 1965 ...... 17

Address by William Glazier, New York State Welfare

Conference, November 1968 ................................... 37

Address by Jack R. Goldberg, “ Witness for Sur

vival” Meeting, Sept. 11, 1969 ............................. 31

Address by Lawrence Goodman, American Associa

tion on Mental Deficiency Conference, May 16,

1969 ........................................................................................ 10

Address by Eunice L. Minton, National Conference

on Social Welfare, May 11-16, 1958 ..............14,21,22

Address by George K. Wyman, New York State Wel

fare Conference, Nov. 1968 ..................................... 23

A dvisory C ouncil, on P ublic W elfare, “ H aving th e

P ower, W e H ave the D u t y ” (1966) ..................... 33

A. P h ilip R andolph I nstitute, A F reedom B udget

for A ll A mericans (1966) ......................................... 28

Bronfenbrenner, Socialization and Social Class

Through Time and Space, in R e ad in g s i n Social

P sychology (3d ed. Maccoby, Newcomb and Hart

ley eds. 1958) ............................................................ 19

I l l

Brown, Organ Weight in Malnutrition with Special

Reference to Brain Weight, 8 D evelop. M ed.

Child Neubol. 512 (1966) ........................................... 11

Caplovitz, T he H igh C ost op P ovebty (1963) ............ 28

Ch ilm an , C rowing U p P oob (1966) ......................... 13 ,16 ,20

Claiborne, “ Even a Food Expert Can Stretch a Wel

fare Budget Only So Far’ ’, New York Times,

July 31, 1969, p. 30 ......................................................... 38

Cohen and Sullivan, Poverty in the United States,

Health, Education and Welfare Indicators, Feb.

1964 ........................................................................................ 28

Coll, Deprivation in Childhood: Its Relation to the

Cycle of Poverty, Welfare in Review, Mar. 1965.. 9 ,17

Com m unity Council op Gbeateb New Y ork , B udget

S tandabd Sebvice, A F am ily B udget S tandabd

(1963) ................................................................................... 33

Com m unity Council of Gbeateb New Y obk, B udget

S tandabd Sebvice, A nnual P bice S ubvey— F am

ily B udget Costs, O ctobeb 1967 (1969) ................ 33

Com m unity S ebvice S ociety op New Y obk, W hat

M akes fob S tbong F am ily L ife (1958) .............. 19

Downs, Who Are the Urban Poor?, Committee for

Economic Development Supplementary Paper

No. 26 (Oct. 1968) ........................................................... 29

Epstein, Some Effects of Low Income on Children

and Their Families, 24 S ocial S ecubity B ulletin

12 (Feb. 1961) .................................................................... 18

F eldman , T he F am ily in a M oney W obld (1957) .... 21

Fernandez, et ah, Nutritional Status of People in Iso

lated Areas of Puerto Rico, 12 A mebican J. Cl in

ic a l N u t k it io n 305 (1965) ..................................... 11

PAGE

1 V

Goode, Economic Factors and, Marital Stability, 16

A merican S ociological R eview 802 (Dec. 1951) 18

H arrington, T he O ther A m erica : P overty in the

U nited S tates (1962) ............................................ 11,22

“ Harvest of Shame’ ’, CBS Reports, CBS News, Nov.

1960 ........................................................................... 29

Hearings on H.R. 12080 before the Senate Commit

tee on Finance, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) ...... 26

H erzog, A bout the P oor— S ome F acts and S ome F ic

tions (Children’s Bureau Pub. No. 451, 1967) .... 15

Hillman and Smith, Hemoglobin in Low-Income Fam

ilies, 83 P ublic H ealth R eports 61 (1967) ...... 9

H qllingshead & R edlich, S ocial Class and M ental

I llness (1958) .......................................................... 12

Irelan, Health Practices of the Poor, Welfare in Re

view, October 1965 .................................................. 8

Keyserling, et al., Poverty and Deprivation in the

United States, The Plight of Two-Fifths of a

Nation, Conference O n E conomic P rogress

(1962) ....................................................................... 28

Kohn, Social Class and the Exercise of Parental Au

thority, 24 A merican S ociological R eview 352

(June 1959) .............................................................. 19

Lampman, The Low Income Population and Economic

Growth, Study Paper No. 12. Joint Economic

Committee, 86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959) ............. 28

Lerner, The Level of Physical Health of the Poverty

Population: A Conceptual Reappraisal of Struc

tural Factors, 6 M edical Care 355 (1969) ............ 7

Lewis, The Culture of Poverty, National Conference

on Social Work (1961) ........................................... 28

Lutz, Marital Incompatibility, S ocial W ork and S o

cial P roblems (Cohen ed. 1964) ....................18, 21, 22

PAGE

V

M acD onald, Our Invisible P oor, The New Y orker,

Jan. 19, 1963 .......................................................... 28

M cCabe, Re: Forty Forgotten Families, 24 P ublic

W elfare 159 (1966) .......................................................14,17

M eier, Child Neglect, S ocial W ork and S ocial P rob

lems (Cohen ed. 1964) ................................................... 16

M iller, R ich Max . P oor Max (1964) .............................. 29

Moles, Training Children in Low-Income Families

for School, W elfare in R eview June, 1965 ............ 17

M organ et al., I ncome and W elfare in the U nited

S tates (1962) .................................................................... 28

N ational Tuberculosis and R esp ira tory Disease A s

soc., Poverty and Health, P arts 1 and 2, Jan. and

Feb. 1969 ............................................................................... 29

New Y ork Tim es, June 12, 1966, §1, p. 56 ................... 39

Orshansky, Recounting the Poor—A Five-Year Re

view, 29 S ocial Security B ulletin 20 (A p ril

1966) ..................................................................................... 18

Orshansky, The Shape of Poverty in 1966, 31 S ocial

S ecurity B ulletin 3 (1968) .................................... 34

Perlm an, Unmarried Mothers, S ocial W ork and S o

cial P roblems (Cohen ed. 1964) .............................. 14

P resident ’ s Commission on L aw E nforcement and

A dministration of J ustice, the Challenge of

Crime in a F ree S ociety (1967) ................................ 28

P resident J ohnson ’s S tate of the U nion M essage

(1964) ................................................................................... 28

R eport of the F irst Conference on M ental R etar

dation, M ild M ental R etardation in I nfancy

and E arly C hildhood (Sim m ons ed. 1966) .......... 11

R eport of the National A dvisory Commission on

C ivil D isorders (1968) .................................................. 28

PAGE

V I

R eport of the P resident ’s A ppalachian R egional

Commission, A ppalachia (1964) .............................. 28

R eport of the P resident ’s C ommittee on M ental

R etardation, MR-68 — T he E dge of Change

(1968) ................................................................................... 10

R eport of the P resident ’s P anel on M ental R etar

dation, a P roposed P rogram for National A ction

to Combat M ental R etardation (1962) .............. 10,11

S chorr, Slum s and S ocial I nsecurity (1963) ............ 8

S tate of New Y ork, E xecutive B udget for the F is

cal Y ear A pril 1, 1969 to M arch 31, 1970 ............ 30

T owle, Common H um an Needs (rev. ed. 1965) ..........

15 ,16 ,17 , 20

U nited S tates B ureau of the Census, E xtent of

P overty in the U nited S tates : 1959-1966 (Se

ries P-20, No. 54, 1968) ................................................ 28

U nited S tates D epartment of A griculture, P overty

in R ural A reas of the U nited S tates, Agricul

tural Economic Rep. No. 63 (1964) .................... 28

U nited S tates D epartment of L abor, B ureau of L a

bor S tatistics, Consumer Price Index ................... 32

U nited S tates D epartment of L abor, B ureau of L a

bor S tatistics, T hree S tandards of L iving for

an U rban F am ily of F our P ersons— S pring 1967 33

U nited S tates D epartment of H ealth , E ducation

and W elfare, D elivery of H ealth Services for

the P oor (1967) ............................................................. 8 ,37

U nited S tates D epartment of H ealth , E ducation

and W elfare, F am ily I ncome and R elated Char

acteristics A mong L ow- I ncome Counties and

S tates (1964) .................................................................... 28

Warkany and Wilson, Prenatal Effects of Nutrition

on the Development of the Nervous System, Ge

netics and the I nheritance of I ntegrated Neu

rological and P sychiatric P roblems (Hooker

and Have eds. 1954) ...................................................... H

PAGE

IN' THE

Qlmtrt of tin? Staffs

October Term, 1989

No. 540

J ulia R osado, L ydia H ebnandez, M ajobie M idey, S ophia

A bbom, R uby Gathebs, L ouise L owman , E ula M ae K ing ,

Catheyn F olk , A nnie L ou P hillips , and M ajobie D uffy ,

individually, on behalf o f their m inor children, and on

behalf o f all other persons sim ilarly situated,

against

Petitioners,

Geobge K. W ym an , individually and in his capacity as Com

missioner of Social Services for the State of New York,

and the D epabtment of S ocial S ebvices fob the S tate of

N ew Y obk,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE FOR THE CATHOLIC

CHARITIES OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF NEW

YORK, CATHOLIC CHARITIES, DIOCESE OF

BROOKLYN, COMMUNITY SERVICE SOCIETY

OF NEW YORK, FEDERATION OF JEWISH

PHILANTHROPIES OF NEW YORK, FEDERA

TION OF PROTESTANT WELFARE AGENCIES

2

Interest of the Amici

The Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York

was incorporated in 1917 as a charitable federation for

the broad purpose of serving the poor and aiding and

coordinating the varied health and welfare programs of

the Archdiocese which had their beginnings as early as

1817. This federation, together with its 203 affiliated

agencies expended in 1968 over $180,000,000 in services for

needy families, children and youth, the sick, aged and

handicapped. It operates a comprehensive range of health

and welfare programs including personal and family coun

selling, homemaker and community services, general and

special hospitals, nursing homes and homes for the aged,

institutional, foster home and adoption programs for

children, special services for the handicapped, residences,

day care centers, children’s camps and programs for citi

zenship training and character development of youth.

Catholic Charities, Diocese of Brooklyn was incorpo

rated in 1931, but its predecessor agency dates from 1889.

It, and its 31 member agencies spent about $54 million in

1968 serving the poor, blind, deaf, retarded, handicapped,

aged, troubled, and sick. These services were provided

through counseling centers, child care agencies, hospitals,

homes for the aged, etc.

Community Service Society of New York is the product

of a merger in 1939 of the Association for Improving the

Conditions of The Poor and the Charity Organization

Society, both of which organizations were created in the

1840’s. Spending almost $5 million annually, its 500 em

ployees provide casework services, group therapy, home

3

maker services, a residence for older persons, research in

family life and social action in the fields of family and

child welfare, housing and urban development, health,

aging, youth and correction and family life education.

The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York

was organized in 1917 and is the coordinating agency in

New York City for Jewish social work. Together with its

more than 130 affiliated agencies, more than $250,000,000 is

spent annually in providing a complete range of health

and welfare services through institutions such as general

hospitals, an orthopedic hospital, a hospital for the men

tally ill, a hospital for the physically handicapped children,

family service agencies, vocational rehabilitation agencies,

child care agencies, foster homes and treatment facilities

for dependent, emotionally disturbed and mentally retarded

children, homes for the aged, community centers, camps,

etc.

Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies was or

ganized in 1921 and now has 235 member agencies. To

gether, they spend more than $100,000,000 each year for

child welfare agencies, nursery schools, day care centers,

camps, treatment centers for disturbed children and for

delinquents, neighborhood youth centers, vocational guid

ance, mental health clinics, narcotics treatment facilities,

maternity shelters, homemaker services, family counsel

ing, neighborhood, social recreational and social activities,

homes for the aged, etc.

Amici and their affiliates combined, serve more than

three million New Yorkers each year. They have had a

long-standing concern for and familiarity with the prob

4

lems for the poor in New York City and State, especially

those in receipt of Aid to Families with Dependent Chil

dren. The citizen members and professional staffs include

physicians, psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, social work

ers, clergy, attorneys, and others familiar with the prob

lems of the poor. As the representatives of the major

portion of the voluntary health and welfare groups in the

City of New York, amici respectfully present their views

on behalf of the AFDC recipients upon the case before

the Court.

Amici have limited their argument to a documentation

of the conditions of which Congress was aware in passing

42 U.S.C. §602(a) (23) and the nature of the damage result

ing from New York’s non-compliance therewith. They are

however, in complete agreement with and subscribe to the

other points raised by petitioners in their brief.

The parties have consented to the filing of this amicus

curiae brief and copies of their letters of consent will be

submitted to the Clerk with the brief.

Summary of the Argument

Congress’ enactment in 1935 of what is now known as

the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program and

42 U.S.C. 602(a) (23), a 1968 amendment to that program,

were both intended to minimize or eliminate what the Con

gress knew to be the incalculable and permanent conse

quences of long-term poverty on children, families and

society in general.

In enacting §131-a of the New York Social Services Law,

the New York State Legislature ignored, in fact violated

5

the requirement of said 42 U.S.C. 602(a) (23) to increase

grants to AFDC recipients to reflect fully increases in the

cost-of-living to July 1, 1969. As a result, the hardships,

suffering and injury which Congress sought to forestall

have been compounded in New York State.

The higher mortality and morbidity rates of the poor,

the greater frequency of illness, disability, chronic condi

tions and malnutrition among them, attest to the close

relationship between poverty and physical health. The

larger presence among the poor of mental retardation and

serious emotional disorders speaks to the consequences of

poverty for mental health. The absence of conditions con

ducive to sound child development among the poor results

in significantly lower levels of educational achievement and

significantly higher numbers of persons unable to function

productively as adults. The pressures of severe economic

deprivation on all family members reduces appreciably the

chances of sound family life and relationships. And the

gap between the poor and the highly-visible rest of society

serves to perpetuate the cycle of poverty by deepening the

despair and hopelessness felt by the poor. All these cir

cumstances not only have a visible effect upon the poor,

but also on the well-being of the entire society.

Desiring to help AFDC recipients to catch up to the

increased cost-of-living by increasing their grants accord

ingly, the Congress, as of early 1968, enacted 42 U.S.C. 602

(a) (23). It sought, by this device, to minimize the effects

of severe deprivation on present and future generations,

at least until major revisions in public income maintenance

programs were undertaken.

6

The evidence is clear that the intent of the New York

State Legislature in enacting §131-a was anything but con

sistent with that of the Congress. They sought merely to

reduce welfare costs without considering the consequences

of such reductions upon the poor.

The effect of these cutbacks is demonstrated over and

over again in the files and records of amici and their affil

iated agencies. That already inadequate AFDC grants

have been further reduced, with the predictable, but none

theless deplorable, results is also apparent. That other

public programs upon which the poor depend are inade

quate to fill the vacuum further intensifies the hardships.

P O I N T I

Aware of the well-documented body of empirical

and theoretical evidence that a real connection exists

between poverty and individual, familial and societal

pathology, Congress initiated the Aid to Dependent

Children (now known as Aid to Families with Depend

ent Children) program in 1935 and amended it in 1967

to render it more effective.

A . Relationship of Poverty to Pathology

Poverty, especially persistent poverty, affects every

aspect of a person’s life: his physical and mental health,

his development as a child, his family relationships and his

relationship to the society around him. And the conse

quences of poverty in turn intensify each other so that once

the chain reaction has begun it is extremely difficult to

avoid the irremedial harm which follows and the incal

culable toll it takes in human life and suffering.

7

1. Physical Health

The symbiotic relationship between poverty and ill

health clearly exists in the slums of large cities in the

United States.

Mortality rates, especially during infancy, childhood,

and even the younger adult ages, are higher here

than for the rest of the population again, and this most

important, especially mortality rates from the com

municable diseases.1

* * * the prevalence of morbidity, impairments, and

disability is probably highest * * * among the poverty

population for the relatively severe conditions, partic

ularly chronic conditions causing activity restriction

for long periods of time. This follows from the higher

prevalence of severe communicable diseases as causes

of death in the poverty population. However, unlike

the situation as regards mortality, where poverty pop

ulation death rates are higher during the younger

years, the prevalence of morbidity, impairment, and

disability is likely to be higher for the poverty popula

tion especially during the later years of mid-life and

old age.2

Twenty-nine percent of persons with family incomes

less than $2,000 have chronic conditions which limit their

activity as compared to about 7.5 percent in families with

incomes above $7,000. Even in the age 17-44 group, the

poor are affected at twice the rate of the non-poor; in the

age 45-64 year old males, the lower income group has three

and one-half times as many disability days. A higher per

1. Lerner, The Level of Physical Health of the Poverty Popula

tion: A Conceptual Reappraisal of Structural Factors, 6 M edical

Care 361 (1968).

2. Id. at 363.

8

cent of persons in poor families have “ multiple hospital

episodes” and they stay in the hospital longer (10.2 days

as compared to 7.3 days). They are more often hospital

ized for non-surgical conditions than the non-poor, though

they are much less likely to have hospital insurance. Poor

children under 15 visit physicians twice a year as compared

to 4.4 times for the non-poor; 22 percent have never seen

a dentist as compared to 7.2 percent in families with in

comes over $10,000.3

Many of the illnesses which the urban poor sutler relate

directly to their living conditions. Acute respiratory in

fections (colds, bronchitis, grippe), infectious diseases of

childhood (measles, chicken-pox, whooping cough), minor

digestive diseases and enteritis (typhoid, dysentery, diar

rhea), injuries from home accidents, skin diseases, lead

poisoning in children from eating scaling paint, pneumonia

and tuberculosis are typical of the physical illness of the

poor.4

Furthermore, other diseases and disabilities not appar

ently related to the physical environment are more common

among the poor: degenerative diseases, particularly cardio

vascular disorders, chronic diseases such as heart disease

and diabetus mellitus, cancer, premature births.5

* # * the more easily recognizable and more serious

types of chronic illness, including paralysis and ortho

3. U nited States D epartm en t of H e a l t h , E ducation and

W elfare, D elivery of H ealth Services for th e P oor at 3-4

(1967).

4. S chorr, S lum s and S ocial I nsecurity 13-14 (1963).

5. Irelan, Health Practices of the Poor, Welfare in Review, Oct.

1965, p. 3.

9

pedic impairments, accounted for 13.8 percent of re

ported chronic conditions for the lowest income group

as compared with 9.7 for those at the top of the income

scale. Even more striking are the differences between

the poor and the rich when it comes to visual and hear

ing impairments. Such handicaps accounted for 12.4

percent of the chronic conditions reported for the

$2,000 group, but only 6.4 percent of such conditions

in the group with an income of $7,000 and over.6

The role of nutrition in the health of the poor is well

understood. Low hemoglobin levels and anemia occur with

greater frequency among the poor.7 Caloric (quantitative)

or nutritive (qualitative) deficiencies or both can cause

malnutrition. Carbohydrates can, relatively cheaply and

quickly, provide calories and energy, but they cannot pro

vide the proteins necessary for proper nutrition.8 Obesity

is a more frequent condition among the poor than among

the non-poor.

2. Mental Health

There is a striking correlation between poverty and

mental retardation.

The majority of the mentally retarded are the chil

dren of the more disadvantaged classes of our society.

This extraordinarily heavy prevalence in certain de

prived population groups suggests a major causative

role, in some way not yet fully delineated, for adverse

social, economic and cultural factors. These conditions

6. Coll, Deprivation in Childhood: Its Relation to the Cycle of

Poverty, Welfare in Review, Mar. 1965, p. 4.

7. Hillman & Smith, Hemoglobin Patterns in Low-Income Fam

ilies, 83 P ublic H ealth R eports 65 (1967).

8. Id. at 3.

10

may not only mean absence of the physical necessities

of life, but the lack of opportunity and motivation. A

number of experiments with the education of pre

sumably retarded children from slum neighborhoods

strongly suggest that a predominant cause of mental

retardation may be the lack of learning opportunities

or absence of “ intellectual vitamins” under these ad

verse environmental conditions. Deprivation in child

hood of opportunities for learning intellectual skills,

childhood emotional disorders which interfere with

learning, or obscure motivational factors appear some

how to stunt young people intellectually during their

developmental period. Whether the causes of retarda,-

tion in a specific individual may turn out to be bio

medical or environmental in character, there is highly

suggestive evidence that the root causes of a great

part of the problem of mental retardation are to be

found in bad social and economic conditions as they

affect individuals and families * * #.9

A variety of circumstances, all typical of the lives of

the poor have been found to lead to mental retardation.

There is a close relationship between inadequate prenatal

care, typical for the poor, premature births, likewise typ

ical,10 and consequent mental retardation.11

In both whites and Negroes, the incidence of pre

maturity became extremely high the lower the socio

economic class * * * this [the higher rates for Negroes]

9. R eport of t h e P resident ' s P a n e l on M en tal R etarda

tio n , A P roposed P rogram for N a tio n al A ction to Combat

M e n ta l R etardation , at 8-9 (1 9 6 2 ) ; see R eport of th e P resi

dent ' s Co m m ittee on M en tal R etardation , MR-68— t h e E dge

of C h ang e , at 19 (1968).

10. R eport of P resident ’s Co m m ittee , supra note 9.

11. Address by Lawrence Goodman, American Association on

Mental Deficiency Conference, May 16, 1969.

11

was not a function so much of the Negro as a somewhat

racially distinct group, but was more the heritage of

prolonged disadvantage in the areas of general health,

medical care, education, and nutrition.12

Various studies point to the relationship between nutri

tion and brain growth,13 maternal malnutrition and toxe

mia and prematurity,14 and to the functional integrity of

the offspring’s nervous system.15

Given the environmental causes of much mental retar

dation, one final fact bears noting:

Unlike other major afflictions, such as cancer or heart

disease, which often come relatively late in life, men

tal retardation typically appears in childhood and

always before adulthood. And once incurred, it is

essentially a permanent handicap, at least at the

present stage of biomedical knowledge.16

But mental retardation is not the only mental health

consequence of poverty.

# * emotional upset is one of the main forms of the

vicious circle of impoverishment. The structure of the

12. R eport of th e F irst Conference on M e n ta l R etarda

tion , M ild M en tal R etardation in I n f a n c y an d E arly C h ild

hood, at 28 (Sim m ons ed. 1966).

13. Fernandez, et al., Nutritional Status of People in Isolated

Areas of Puerto Rico, 12 A m erican J. Cl in ic a l N utrition (1965) ;

Brown, Organ Weight in Malnutrition With Special Reference to

Brain Weight, 8 D evelop. M ed. C h ild N eurol. (1 9 6 6 ).

14. R eport of th e F irst Conference on M en tal R etarda

tio n , supra note 12, at 30.

15. Warkany & Wilson, Prenatal Effects of Nutrition on the

Development of the Nervous System, in Genetics a n d th e I n h e r

itan ce of I ntegrated N eurological an d P sych iatric P roblems

(H ooker & Have eds. 1954).

16. R eport of th e P resident ’ s P a n e l , supra note 9, at 10.

12

society is hostile to these people * * * the poor tend

to become pessimistic and depressed; they seek imme

diate gratification instead of saving; they act out.17

The classic study Social Class and Mental Illness by

Hollingshead and Redlich18 discloses that the poor’s rate

of “ treated psychiatric illness” is about three times as

high as the average for the other social classes. Further

more, of those who had received some psychiatric treat

ment, 65 percent in the top four classes (out of five) had

been treated for neurotic problems, the rest for psychotic

disturbances. Among the poor, 90 percent of those treated

had psychotic problems.

W hat happens to the psyche o f the im poverished indi

vidual that accounts fo r the large am ount o f em otional

disturbance that appears to exist?

It is hypothesized that emotional depression may

be the prevalent life style of many lower-lower-class

members and that this depression (if such it is) has

its origins in overwhelming anxiety associated with

the almost constant powerful frustrations and threats

which surround the slum-dweller from infancy to old

age. While both research and theory point to the

positive contribution of mild frustration and asso

ciated mild anxiety to achievement and to ego-strength,

constant and overpowering frustrations make achieve

ment an untenable goal and seriously weaken the ego—•

or self-esteem * * *

With generally less ego strength (lower self-

esteem), the very poor individual is apt to have

17. H arrin gton , T h e O th er A m e r ic a : P overty in t h e

U n ited States 138 (19 62 ).

18. (19 58 ).

.13

greater need than his middle-class counterpart for

security-giving psychological defenses. But defenses

such as sublimation, rationalization, identification with

the larger community and its leaders, compensation,

idealization, and substitution of generally accepted

gratifications are not so readily available to him in

his impoverished, constricted environment and with

his own lack of economic and intellectual resources.

* * * for instance, the lower-class adolescent tends to

use defense mechanisms in handling aggressive drives

and failure fears which require little previous expe

rience, involve maximum distortion, and create social

difficulties, whereas middle-class children are more apt

to use defense mechanisms which require many skills

involve a minimum of distortion and are socially

acceptable. * * *

Since the pressures on the lower-lower-class male

for unobtainable, occupational success are greater than

on the female, it is hypothesized that depressive reac

tions, confusion over identity, and recourse to the

various mechanisms for self-expressive escape would

probably occur in a higher proportion of men and to

a more pervasive degree. The higher rates among

males (especially in the lower-lower-class) of mental

illness, alcoholism, drug addiction, crime and delin

quency are, perhaps, associated, at least in part, with

factors such as these.19

For the most part, in AFDC families the mother is the

only parent in the home. Even if she had been legally

married to the father a severe burden falls upon her. She

must fulfill both parental roles with their heavy demands.

These demands are overcast and suffered by the emo

tional impact of the loss or absence of the father

on the mother and children. Shifting of roles com

19. Chilman, Growing U p Poor 31-33 (1966).

34

bined with the immediacy of inadequate income can

play into dependency needs and can be used to feed

neurotic tendencies in mothers and their children.20

These difficulties are further intensified when the parent

is an unmarried mother. The public image of such AFDC

mothers, manifested by periodic attacks in the press, as

irresponsible and immoral, has its effects psychologically:

an apathy or resignation, which is the end product

of hopelessness, a lowered sense of self-esteem and

worth, the product of being held in small account by

others, and a heightened sense of being an outsider

to the larger society. Sometimes the outcast manages

her feelings by indifference, clowning, self-deprecia

tion. Sometimes she strikes out blindly against those

who, to her, represent the “ ins” . * * *

Other social and psychological stresses accompany

economic stress. The unmarried mother who keeps her

baby finds few avenues of self-expression and pleasure

open to her. She is homebound with the care of her

baby or she is neglectful of him. She has no husband

to whom to express her aggravation or boredom. The

baby more often than not pauses her to lose a man who

might have been a husband someday, if her pregnancy

and its consequences had not scared him off, or to

lose a man who gave her some sense that she was

wanted. So the baby often represents the fruit of

her badness or foolishness as well as the betrayal by

the man who got her into trouble. Mothering rarely

flows warmly and dependably toward the baby thus

ruefully or angrily borne.21

20. Address by Eunice L. Minton, National Conference on So

cial Welfare, May 11-16, 1958.

21. Perlman, Unmarried Mothers, in S ocial W ork and Social

P roblems 275-276 (Cohen ed. 1964) ; see McCabe, Re: Forty For

gotten Families, 24 P ublic W elfare 161-163 (1966).

15

3. Child Development

It is in children that some of the most damaging con

sequences of poverty can be found. Whether it be from

malnutrition, other disease, marital tensions, emotional

upset in the home or any other of the common occurrences

in the poverty-stricken home, the children of that home

suffer deeply.

The infant * * * has three sources of security that

enable him to feel safe and, therefore, to experience

a satisfying relationship with others: (1) consistent

physical care and conditions conducive to good health

requisite to a feeling of well-being, (2) uninterrupted

opportunity to learn and reassuring encouragement to

persist in learning through sympathetic attention to

his hurts when his first learning efforts endanger his

safety, (3) relationships in which he is loved.22

But the malnourished infant is restless, irritable, hyper

active or apathetic. His crying and whining provokes his

mother to show her annoyance by a scolding or a slap,

“ thus reinforcing the infant’s feeling of being unloved.” 23

The attention he thus receives prompts him to persist and,

unless his mother changes her reaction, the child may

become an aggressive, demanding person.

Economic security is important also from the stand

point that the mother, if anxious and harrassed, trans

mits her disturbed feelings to the infant, perhaps to

an even greater extent than when the child is older.24

22. T ow le , Com m on H u m a n N eeds 50 (rev. ed. 1965).

23. Id. at 6.

24. Id. at 54; see H erzog, A bout t h e P oor— Some F acts and

S ome F ictions 15 (Children’s Bureau Pub. N o. 451, 1967).

16

Because the children receiving AFDC are most often

in one-parent homes where the full burden of child-rearing

falls on the mother usually, and where the father’s absence

is itself a loss to the child, the children are “ exposed to a

greater hazard of having less than average opportunities

for development,25 26 The consequences of this deprivation

may be either destructive activities or clinging to infantile

behavior. Either course prevents the child from learning

how to master his environment, so necessary to his stability

in adult life.20

The parental patterns more characteristic of the

very poor, in reference to educational achievement,

seem to be oriented towards an anticipation of failure,

and a distrust of middle-class institutions, such as the

schools. Constriction in experience, reliance on a

physical rather than a verbal style, a rigid rather than

flexible approach, preference for concrete rather than

abstract thinking, reliance on personal attributes rath

er than training or skills, a tendency toward magical

rather than scientific thinking: these values and atti

tudes provide poor preparation and support for many

of the children of the very poor as they struggle to

meet the demands of the middle-class oriented school.27

This theory is borne out by the evidence. Although

AFDC children start out on the same level as others, they

fall behind so that at about 15 years of age they are a

semester or more behind. At each age, a greater propor

tion of such children were “ overage” for their grade,

having failed a semester or more. Children who have failed

25. Meier, Child Neglect, in Social W ork an d Social P rob

lem s , supra note 21, at 192.

26. T ow le , supra note 22, at 55-56.

27. C h il m a n , supra note 19, at 45.

17

are more likely to drop out.28 That this has implications

for their future independence as adults can be seen by the

low level of educational achievement of AFDC mothers,29

and the reduced chances for children’s achievement if their

parents’ education level was low.30

The adolescents in economically precarious families are

subject to stresses in addition to those normally faced. At

a time when they are experiencing a tension between their

past dependency and their wish to be independent, the finan

cial uncertainty of the family may cause them to

cling more tenaciously to the parents,, or, in the inter

ests of survival, be compelled to escape the uncertain

ties of their family life through an abrupt and prema

ture “ cutting off.” They may needfully assert their

right to keep their own earnings and out of a tragic

necessity pursue their own paths unhampered by the

burden of the past.31

While having to confront the harsh realities of the adult

world is not per se a destructive experience, having to do

so all at once without adequate past preparation can be

quite damaging.32

Of crucial importance is the way in which the at

tenuation of values, confusion of identity, and depre

28. Moles, Training Children in Low-Income Families for School,

Welfare in Review, June 1965, pp. 1-2; see McCabe, supra note 21,

at 166-167.

29. Coll, supra note 6, at 6-7.

30. Address by Herbert Bienstock, Conference on the Dimensions

of Poverty, American Statistical Association, New York Chapter,

March 11, 1965.

31. T ow le , supra note 22, at 63.

32. Id. at 67-68.

18

ciation of self-esteem are transmitted from one genera

tion to another. The sense of anonymity, of being the

helpless instrument of irresistible and inaccessible

social and economic forces, of injustice and anger, of

apathy, of despair that conformity to any value system

will make life more rewarding, all may have been

experienced reactively by adults, as the cultural, polit

ical, economic, and social causes began to exert their

influence. As these adults become parents, however,

their helplessness, blurred sense of identity, and norm-

lessness are presented to their children as models for

identification. As the children identify with these

aspects of the parents, confusion and normlessness are

built into the personality structure of the children.

The resulting damage will continue from generation

to generation unless changes in the external society

and culture intervene to break the cycle and afford new

generations more effective models of identification.33

4. Family Life

There is considerable evidence that the family structure

and life of the poor is different from that of the non-poor.

Separation, desertion and divorce appear to vary in fre

quency in inverse proportion to income; the same seems to

be true for family size.34 Further, families headed by

women are far more frequent among the poor, as are out-

of-wedlock births. Differences appear in child rearing

33. Lutz, Marital Incompatibility, in S ocial W ork a n d S ocial

P roblems, supra note 21, at 104.

34. Epstein, Some Effects of Low Income on Children and Their

Families, 24 Social Security B u lletin (Feb. 1961); Goode, Eco

nomic Factors and Marital Stability, 16 A m erican S ociological

R eview (Dec. 1951); Orshansky, Recounting The Poor—A Five-

Year Review, 29 S ocial Security B u lle tin (April 1966).

19

practices, with physical punishment and ridicule used more

often by the poor.35

To start with, we must keep in mind that above all

else, people have minimum basic material needs—suf

ficient food and clothing, adequate living accommoda

tions and medical care. These must be met. If people

are in serious danger of losing the fight for survival

they will be unable to use their energy and intellect

for the things that enhance life, make it human and

rich in heart, mind and spirit. With its basic material

needs met, a family can devote its strength to efforts

aimed at making itself as sound as possible.36

The past and present circumstances of poor persons

work against their chances for successful marital and fam

ily relationships.

Husbands and wives on the lowest socioeconomic level

tend to have a poorer start in marriage than other

couples and the same is true for their children. Many

are high school dropouts (over half or more). One

result of this is that they are likely to be forced into

adult roles earlier than other adolescents. A young

person out of school is not given the sanctions for

adolescent behavior and the security of protection that

students are given. This may be one reason that more

of the very poor drift into marriage in their middle

or late teens, often following a premarital pregnancy.

Added to their youth, lack of education and poor

preparation for marriage and parenthood, there is the

35. Bronfenbrenner, Socialisation and Social Class Through Time

and Space, in R eadings in Social P sychology (3d ed. Maccoby,

Newcomb and Hartley eds. 1958) ; Kohn, Social Class and the Exer

cise of Parental Authority, 24 A m erican S ociological R eview

(June 1959).

36. Co m m u n it y Service S ociety of N ew Y ork , W h a t M akes

for Strong F a m il y L ife (1958).

20

likelihood that the young husband will find either a

very inadequate job or no job at all. The life experi

ences that such young couples have had growing up

in their own homes and in the poverty environment

offer seriously reduced opportunities for a satisfying,

stable marriage and family life of their own.37

What happens, psycho-socially, to families with inade

quate funds has been considered by many experts in the

field. There is general agreement that while inadequate

funds will not alone destroy family life, it will tend to

enlarge family difficulties. From the psychological per

spective,

One may expect more regressive responses on the

part of parents in families where there is economic

strain. When regression occurs in the adult, it is not

as normal an aspect of the growth process as it is in

the adolescent. Because the demands of adult life are

likely to be more consistently inescapable than those

in adolescence and because the personality is more

rigidly formed, retreats to more satisfying life periods

of the past may bring a more lasting fixation.38

Desertion is a not uncommon phenomenon in the families

of the poor. While financial hardship may not be the most

important cause of family breakdown, it is an effective

fertilizer for the seeds of disruption.

If the partners are incompatible and do not have

the same ideals and goals, the tension between them

is likely to mount when they live in a cold or over

crowded home and when they do not have enough to

eat or to wear. Worry about the future for themselves

37. C h il m a n , supra note 19, at 71.

38. T ow le , supra note 22, at 85.

21

and their children adds to the strain. Desertion,

therefore, may represent a desperate attempt on the

part of the father to escape responsibilities he cannot

meet and to find a means of personal survival.39

For the families receiving public assistance, financial

hardship is not significantly alleviated.

The grants support life and physical health if the

recipient families manage them well. Indigent families

are required to manage their funds more efficiently

than everyone else in the population. The oppor

tunity for some margin, some cushion, in the use of

money is a powerful antidote to strain in inter

personal relations and intrapersonal conflict. The

starkness and monotony of poverty contribute to de

spair and help to break down whatever abilities mar

ried people possess to perform the various functions of

marriage, including the rendering of reciprocal emo

tional support and recognition.40

The large amounts of extreme disability — of all kinds

— in the public assistance caseload further complicate the

family life of the recipients. Even though the effect is

significant enough if it is a child who is disabled, the

situation is even worse when it is a parent. Considering

the inadequacy of the grant normally, having to balance

the regular needs of the family and the special needs of

the disabled person heightens the difficulty. “ It is small

wonder that frustration, hopelessness and family discord

often accompany prolonged disability.’ ’41

39. F e ldm an , T he F a m il y in a M oney W orld 67 (1957).

Desertion among A FD C families is also caused by many States’ ,

though not New Y ork ’s, refusal to provide such aid where the father

is in the home.

40. Lutz, supra note 33, at 83-84.

41. Minton, supra note 20.

22

In sum, then

Marital incompatibility may be exacerbated * # *

when grants are kept so low that they impair the

health of the marital partners or precipitate disagree

ments between them over the ways in which the inade

quate funds should be used * * *42

5. Social Alienation

Because the poor have very little or no money they

are placed at the bottom of society’s classification scheme.

Since the society tends to measure a person’s worth and

status by his money, the shortage of money implies a

lower value-level for the poor. And since they do not have

the content of living of most, the poor tend to be set apart;

but they remain affected by the standards of living set

by society.

It is an ironical socio-economic fact that the higher

our standards of living go, the more the groups with

low and fairly static income status becomes disad

vantaged and isolated. The effects, therefore, are

often a greater sense of personal inadequacy and

failure.43

For example, the poor do not participate in the social,

charitable and fraternal organizations of the American

society. And because we consider our society to be a

classless one, few organizations are created along class

lines. The result is that the poor person, feeling less able

to participate, stays away.44

42. Lutz, supra note 33, at 101.

43. Minton, supra note 20.

44. H arrin gton , supra note 17, at 133-134.

23

The poor have the least voice in government. They

lack the vocabulary, the clothes, the carfare, the knowl

edge, the self-confidence to move institutions to get

things done. They lack the skills of knowing how to

telephone the authorities, write letters, get up peti

tions, address public hearings, of whom to call or

whom to ask for improvement in their services: better

garbage collection, building code enforcement, police

protection. * * *

The point is, the economically deprived are so far

removed from the American standard of life that they

no longer feel part of the larger society — they feel

excluded, isolated, and alienated. The poor believe

that they are unable to take advantage of the better

things in life, some costing money, but others, like

education, free. The best they can foresee is imperma

nent jobs, bad housing, inferior schools, and few of

the conventional pleasures they continually see on

television. Forced to live with others like themselves,

they learn to accept standard services from police,

clinics, schools, sanitation departments, landlords and

merchants.45

B. Congressional Purpose and Intent

Congress, in its initial passage of Aid to Families with

Dependent Children legislation (Title 42 U.S.C. §§601-610),

and later, in its amendment §602(a) (23) expressed a clear

purpose. In its initiation of a program of comprehensive

Federal grants to states who, in setting up state-wide pro

grams of aid to dependent children complied with the

requirements laid down in Title 42 of the United States

Code §§601-610, Congress explicitly reveals its concern and

intent.

45. Address by George K. Wyman, New York State Welfare

Conference, Nov. 1968.

24

For the purpose of encouraging the care of depend

ent children in their own homes or in the homes of

relatives by enabling each State to furnish financial

assistance and rehabilitation and other services, as far

as practicable under the conditions in such State, to

needy dependent children and the parents or relatives

with whom they are living to help maintain and

strengthen family life and to help such parents or rela

tives to attain or retain capability for the maximum

self-support and personal independence consistent with

the maintenance of continuing parental care and pro

tection, there is authorized to be appropriated for each

fiscal year a sum sufficient to carry out the purposes

of this subchapter. The sums made available under

this section shall be used for making payments to

States which have submitted, and had approved by the

Secretary, State plans for aid and services to needy

families with children. 42 U.S.C. 601.

It entered into this program with full recognition that

while programs of public assistance were, in the first in

stance a state responsibility, the magnitude of the problems

and their national impact required a federally-based scheme

supported by federal monies. So that from 1935 on, and

with regular and careful reviews up to 1968, Congress has

been deeply involved and concerned with a program of aid

for dependent children.

The State of New York instituted a program of aid to

dependent children in 1937, expressing at all times an ex

plicit purpose to comply with the Federal requirements.

According to the New York State Social Services Law,

§358 Federal aid to dependent children.

The department shall submit the plan for aid to

dependent children to the federal security agency or

25

other federal agency established by or for the purpose

of administering the federal social security act for ap

proval pursuant to the provisions of such federal act.

The department shall act for the state in any negotia

tions relative to the submission and approval of such

plan and make any arrangement which may be neces

sary to obtain and retain such approval and to secure

for the state the benefits of the provisions of such fed

eral act relating to aid to dependent children. The

board shall make such rules not inconsistent with law

as may be necessary to make such plan conform to the

provisions of such federal act and any rules and regula

tions adopted pursuant thereto. The department shall

make reports to such federal agency in the form and

nature required by it and in all respects comply with

any request or direction of such federal agency which

may be necessary to assure the correctness and verifi

cation of such reports. * * *

And an examination of the development of the New York

State laws setting up a program for dependent children

and the history of their amendments reveals a consistent

and systematic course of changes following on the heels of

Federal statutory or administrative changes. The New

York State Legislature has passed a body of legislation

designed for tandem action and conformity with Federal

law in this area.

In 1968, mindful as always of the economic changes con

tinuing to sweep the country and the continuing and ever-

pressing needs of those desperately dependent for their

well-being on government money, Congress set about to

review what changes, if any, were to be made in the Social

Security Act. As a result of extensive hearings and tes

timony, Congress passed, inter alia, subdivision (23) of

42 U.S.C. §602(a) effective January 2, 1968 as an amend-

26

ment to Title IV of the Social Security Act (Grants to

States for Aid and Services to Needy Families with Chil

dren) as follows:

§602; State plans for aid and services to needy families

with children; contents; approval by Secretary

(a) A State plan for aid and services to needy

families with children must * * *

(23) provide that by July 1, 1969, the amounts used

by the State to determine the needs of individuals will

have been adjusted to reflect fully changes in living

costs since such amounts were established, and any

maximums that the State imposes on the amount of aid

paid to families will have been proportionately ad

justed.

Testimony given at hearings before the Congressional

Committees drafting this amendment concentrated on the

need for improvement of methods calculated to bring pay

ments made to those eligible under the program closer to

the cost of the basic needs sought to be covered.46 There

46. Under Secretary of U. S. Dep’t of Health, Education and

Welfare Wilbur Cohen testified, in part, as follows:

But, it is not enough only to require the States to meet need

standards. They must assure that these standards reflect current

prices. There is no requirement in present Federal law that

State standards be kept up to date. In Colorado, the standards

for aid to the permanently and totally disabled have not changed

since 1956. Those for the blind have not been changed in Mas

sachusetts since 1956. Wisconsin standards used today for all

assistance programs were set in 1958, and Ohio’s were set in

1959. Only 25 States have standards that have been brought up

to date in terms of recent pricing within the last 2 years.

W e propose that States be required to update on July 1, 1968,

the assistance standards they are now using. From that date on

they would have to review these standards annually and modify

them with significant changes occurring in the cost of living.

Hearings on H.R. 12080 before the Senate Committee on Fi

nance, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. 259 (1967).

27

was extensive evidence that the rapid and significant rise,

nationwide, in the cost of living raised serious question of

the adequacy of grants being made to the needy families.

Apart from consideration of the knotty problem of basic

and sweeping revision of the delivery of welfare aid to the

poor in general, it was quickly apparent that in the interim,

at least, the states should he required to raise the level of

their grants, i.e. monies actually paid out, by a proportion

fully reflecting the rise in living costs since the schedules

were last established.

There is no doubt, in view of the discussions which took

place at the time, that it was the clear intent of Congress,

fully mindful of the complexity of the welfare crisis then

confronting the states, to effect, at the very least, a real

raise in the dollar amount each eligible family would begin

to receive. Any state legislative change which followed

was not intended by Congress, under any circumstances,

to result in a downward revision of dollars actually paid out

to any family eligible for such aid.

C. Congressional Knowledge of Relationship

Between Poverty and Social Ills

Congress, which has been actively legislating in the

field of social legislation for more than thirty years, is

probably the best-educated institution existent in the nation

with respect to the connection between poverty and those

community conditions undesirable and detrimental to life

in the United States. As the chief appropriating arm of

the government, it also is acutely aware of the changes in

cost of living which are, of course, intimately bound up

28

with the effectiveness of any program aimed at helping

people sustain themselves. The governmental agencies

charged with administering programs relevant to welfare

aid turn out for their own and Congressional use highly

developed and detailed information and studies. These are

designed to keep Congress accurately informed of the na

ture of the problems and the effectiveness of programs, in

cluding proposals for reform.47

Professional writers, sociologists, social workers have

also written books and articles which make up an extensive

and widely publicized literature on the subject.48

47. In addition to those official reports cited elsewhere in this

brief, such studies, statements and reports include: P resident Jo h n

son ' s S tate of t h e U n io n M essage (1 9 6 4 ); Annual Economic

Reports to the Congress by the President’s Council of Economic A d

visors of which the Congress’ Joint Economic Committee makes con

tinuing studies; Lampman, The Low Income Population and Eco

nomic Growth, Study Paper No. 12, Joint Economic Committee,

86th Cong., 1st Sess. (1959) ;. U . S. D e par tm e n t of A griculture,

P overty in R u ral A reas of t h e U n ited States, Agricultural

Economics Rep'. No. 63 (1 9 6 4 ) ; R eport of t h e P resident ’ s A p

p a l a c h ia n R egional Co m m issio n , A p p a l a c h ia (1 9 6 4 ); U. S.

B ureau of th e Census, E xt e n t of P overty in t h e U nited

S tates : 1959-1966 (Series P-20, No. 54, 1968 ) ; U . S. D epartm en t

of H e a l t h , E ducation a n d W elfare, F a m il y I ncome an d R e

lated C haracteristics A mong L o w - I ncome Counties and

States (1 9 6 4 ) ; P resident ’s Co m m ission on L a w E nforcem ent

a n d A d m in istra tio n of Justice , t h e C h allenge of Cr im e in

a F ree S ociety (1967) ; R eport of t h e N a tio n al A dvisory Co m

m issio n on C iv il D isorders (1 9 6 8 ); Cohen & Sullivan, Poverty

in the United States, Health, Education and Welfare Indicators, Feb.

1964.

48. In addition to those books and articles cited elsewhere in this

brief are: Lewis, The Citlticre of Poverty, National Conference on

Social Welfare (1961) ; C aplovitz, T he H igh Cost of P overty

(1963) ; MacDonald, Our Invisible Poor, The New Yorker, Jan. 19,

1963 ; M organ et ah, I ncome and W elfare in t h e U nited States

(1962) ; Keyserling et ah, Poverty and Deprivation in the United

States, The Plight of Two-Fifths of a Nation, Conference on E co

n om ic P rogress (1962); A . P h il ip R andolph I n stitu te , a F ree

29

In addition, the newspapers and other news media, ful

filling their public requirements have given wide and

graphic publicity to social and economic conditions in the

poverty-stricken part of our national community.49

Finally, the Poor Peoples’ March literally took the poor

and their problems to the steps of Congress.

All this is cited to emphasize what it perhaps all too

obvious, namely, that Congress in legislating a requirement

for adjustment in the level of payments to reflect the change

in cost of living had as its sole and overriding purpose

ameliorating the desperate need of people who could not

wait for deeper and more far-reaching reform. It was the

intention of Congress that any adjustment which a state

made to satisfy the Federal requirement of §602(a)(23)

would result in a net dollar increase in the amount paid to

each eligible family on its AFDC rolls.

dom B udget for A ll A m ericans (1966 ); National Tuberculosis

and Respiratory Disease Assoc., Poverty and Health, Parts 1 and 2,

Jan. and Feb. 1969; M iller, R ic h M a n , P oor M a n (1964 );

Downs, Who Are the Urban Poor?, Committee for Economic De

velopment Supplementary Paper No. 26 (Oct. 1968).

49. E.g., “ Harvest of Shame” , CBS Reports, CBS News, Nov.

1960.

30

P O I N T II

The passage of Section 131-a of the New York So

cial Services Law rendered the New York state-plan

for AFDC non-compliant with Section 602(a) (23) of

Title 42 of the United States Code, part of the Social

Security Act.

Section 131-a of the Social Services Law purports to be

merely an administrative streamlining of the state’s wel

fare system to counteract “ the spiraling rise of public as

sistance rolls and the expenditures therefore.” N.Y. Sess.

Laws 1969, Ch. 184, §1. In fact, it has been proven to be

a systematic reduction of AFDC grants.

While Respondent Commissioner’s original proposals

to the Governor regarding welfare reform spelled out a

system of flat grants, the bases and schedules upon which

the standards of assistance were to be determined were

higher than those now called for by § 131-a and included

items theretofore included as special grants. The Governor,

however, “ to keep expenditures within available income” 50

recommended a reduction by approximately 5% across-the-

board. While the Legislature modified the Governor’s pro

posed budget by granting greater aid than requested for

some items, it reduced public assistance categories, Aid to

Families with Dependent Children among them, even fur

ther.

This legislative history is recited here to bear out Pe

titioners’ contention that passage of §131-a had as its prime

50. State of N ew Y ork , E xecutive B udget for t h e F iscal

Y ear A pril 1, 1969 to M arch 31, 1970, at p. 739.

31

motivation a trimming of costs, with, the AFDC program to

bear a greater portion of the cost-saving than other state

programs.

This is further evidenced by subsequent action of Re

spondent Commissioner, when on September 24, 1969, he

authorized a statewide “ special necessity grant” for re

cipients of aid in the adult categories (Aid to the Aged,

Blind and Disabled) in response to severe hardships suf

fered by them in the welfare cutbacks of that spring. But

nothing for children and their parents.

The greatest proportion of the public assistance case

load in New York State is the AFDC roll—approximately

75%. Most beneficiaries of the AFDC program in the

State of New York live in New York City: 657,000 out of a

statewide total of 887,000 was the 1968 monthly average.

The Commissioner of the New York City Department

of Social Services of the City of New York stated unequiv

ocally and publicly, that claims that more than 50% of

welfare recipients were receiving more money under the

new State schedule of payments were false. He said, “ At

least 75% of the persons in the City of New York are, in

fact, receiving less money now than they were before the

new grant system went into effect. ’ ’51

So that in the State of New York, a cut-back affecting

AFDC payments rather than other forms of aid, results in

the greatest possible budgetary gain. It was this fact

rather than any other which motivated the designers of the

51. Address by Jack R. Goldberg, “ Witness for Survival” Meet

ing, Sept. 11, 1969.

32

new system of granting AFDC in New York in the Legis

lature 1968-1969.

It was common knowledge that since the last re-pricing

of the assistance grants as of May 1968, the cost-of-living

had increased. From that time until July 1, 1969 the Con

sumer Price Index in New York City for all items increased

7.08%.52

Clearly then, the effect of §131-a was directly contrary

to the effects intended by the Congress in its enactment of

42 U.S.C. 602(a) (23). Even if what was intended by the

Congress was a single adjustment made before July 1, 1969

and current only to the date of the adjustment, New York’s

single adjustment in May 1968 has more than been wiped

out by the provisions of §131-a. The fact is that most re

cipients in New York City (75%)—and therefore in the

State—are receiving grants appreciably lower than those

they received under the May 1968 adjustment.

P O I N T I I I

Levels of AFDC grants had been grossly insuffi

cient to meet the needs of the recipents and the effects

of the reductions caused by Section 131-a of the New

York Social Services Law have incalculably worsened

the plight of the recipients.

According to the Advisory Council on Public Welfare

(appointed by the Secretary of Health, Education and Wel

fare pursuant to the provisions of 42 U.S.C. 1314),

Public assistance payments to needy families and

individuals fall seriously below what this Nation has

proclaimed to be the “ poverty level.” Federal par-

52. U n ited States D epar tm e n t of L abor, B ureau of L abor

Statistics , Consumer Price Index.

33

ticipation in a nationwide program of public assistance

payments that are grossly inadequate and widely vari

able not only perpetuates destitution and intensities

poverty-related problems but also contradicts the Na

tion’s commitments to its poor. * * #

The national average provides little more than half

the amount admittedly required by a family for sub

sistence; in some low-income States, it is less than a

quarter of that amount. The low public assistance pay

ments contribute to the perpetuation of poverty and

deprivation that extends to future generations.53

This was descriptive of the situation in New York before

the enactment of §131-a. Patently, therefore, that section

reduced grants already at subsistence to levels of desper

ation.

A comparison54 of the current grants under AFDC in

New York City with other relevant standards is revealing

in this respect. Using the family of four as a basis for

comparison and accounting for increases in the consumer

53. T h e A dvisory Cou n cil on P ublic W elfare , “ H avin g

t h e P ower, W e H ave t h e D u t y ” 15-16 (1966).

54. Based on the following memorandum prepared by Miss Edith

Taittonen, Director of Home Economics Service of Community Serv

ice Society of New Y ork :

Com parative D a t a on Cost of L iving—-Ju ly 1969

I. Three Standards of Living for cm Urban Family of Four Per

sons, Spring 1967, U. S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Statistics.

Family of four— man, 38, employed, woman, housewife,

boy 13, girl 8

Lower cost standard, metropolitan New York, annual cost

of goods and services (excluding tax)

Spring 1967 $4,919

July 1969 5,488*

II. A Family Budget Standard, 1963 and Annual Price Survey—

Family Budget Costs— October 1968, Community Council of

Greater New York.

34

prices index until July 1, 1969 the following figures are

disclosed:

Family of four— man, 38, employed, woman, housewife,

boy 13, girl 8.

Annual cost of goods and services (excluding tax)

October 1968 $6,629.48

July 1969 6,922.50*

Family of four— woman, 34, housewife, boy 12, girl 9,

girl 6.

Annual cost of goods and services

October 1968 $5,473.00

July 1969 5,714.91*

Family of four— woman, 34, housewife, children 5, 3

and 1.

Annual cost of goods and services

October 1968 $4,635.80

July 1969 4,840.70*

III. “ The Shape of Poverty in 1966” , Social Security Bulletin,

March 1968, p. 4.

Family of four— criteria used by the Federal government

as a measure of poverty

March 1967 $3,335.00

July 1969 3,717.52**

IV. Department of Social Services, New York City.

Family of four, one adult, three children, projecting semi

monthly grants and monthly rent of $93 into annual income.

Oldest child:

Grants effective*** Grant effective

prior to July 1,1969 from July 1, 1969

16 to 21 4180. )

14 and 15 4060. )

12 and 13 3940. )

10 and 11 3820. )

8 and 9 3652. )

6 and 7 3508. )

under 5 3340. )

3612.00

* Consumer Price Index (base 1957-59), New York, New York, used

to estimate the increase in the cost.

** Consumer Price Index (base 1957-59), U. S. City Average, used

to estimate the increase in cost.

*** Includes cyclical grant of $100 per person, per year for clothing and

house furnishings.

35

AFDC grant

(including rent of $93 per month) $3,612.00

Social Security Administration Index

(poverty level) 3,717.50

Bureau of Labor Statistics

(New York-Northeastern New Jersey area,

lower standard, exclusive of taxes) 5,488.00

Community Council of Greater New York

(Family Budget Standard,

exclusive of taxes) 6,922.50

It is apparent that the AFDC grant specified by §131-a

of the Social Services Law falls below what is generally

thought to be a minimum acceptable standard of living. A

more refined comparison55 confirms this contention. Using

two typical AFDC families—a mother with three children

under five, and a mother with three children of 6, 9, and 12

—and using July 1969, New York City prices for the goods

and services required by such families the following annual

figures are obtained:

AFDC grant (including rent) $3,612.00

AFDC need (mother, three children

of 5, 3, and 1) 4,840.70

AFDC need (mother, three children

of 6, 9, and 12) 5,714.91

Families receiving AFDC are also dependent on other

publicly-supported, though non-public assistance, programs

such as day-care, health services, and supplementary food

programs. There is general agreement that these pro

grams do not provide adequately for AFDC families, or

other poor persons for that matter.

55. Ibid.

36

According to a survey of the day care population by the

Division of Day Care of the New York City Department of

Social Services as of May 1969, only 22% of the families

and 30% of the children who were receiving day care serv

ices were also receiving public assistance. The problem is

further compounded by the shortage of facilities for both