Marino v New York City Police Department Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Proposed Brief in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

August 22, 1987

39 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marino v New York City Police Department Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Proposed Brief in Support of Respondents, 1987. 5bb86b08-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d55df429-3991-4a16-9a93-2733cef01840/marino-v-new-york-city-police-department-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-and-proposed-brief-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

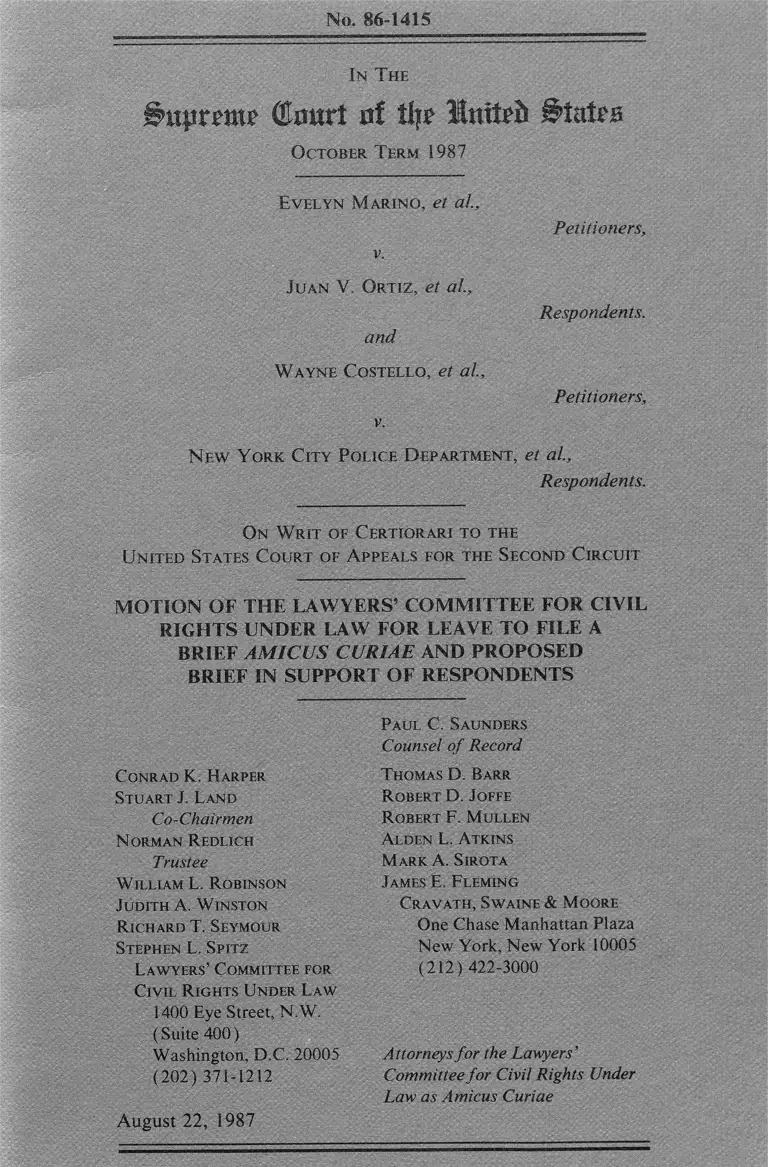

No. 86-1415

In T he

Ipuyrme (Hmtrl nf tlj? IHnittb States

O ctober T erm 1987

Evelyn M arino, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

Juan V. Ortiz, et aL,

Respondents.

and

W ayne Costello, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

N ew Y ork C ity P olice D epartment, et al.,

Respondents.

O n W rit of Certiorari to the

United States Court of A ppeals for the Second C ircuit

MOTION OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW FOR LEAVE TO FILE A

BRIEF AM ICUS CURIAE AND PROPOSED

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

N orman Redijch

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Judith A. Winston

Richard T. Seymour

Stephen L. Spitz

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

(Suite 400)

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

August 22, 1987

Paul C. Saunders

Counsel of Record

Thomas D. Barr

Robert D. Joffe

Robert F. Mullen

Alden L. Atkins

Mark A. Sirota

James E. Fleming

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

(212) 422-3000

Attorneys for the Lawyers’

Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law as Amicus Curiae

No. 86-1415

In The

Supreme <£mtrt of tl|T l&nxtib B M bb

October T erm 1987

Evelyn M arino, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Juan V. O rtiz, et al,

Respondents.

and

W ayne Costello, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

N ew Y ork C ity P olice D epartment, et al,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the

U nited States Court of Appeals for the Second C ircuit

MOTION OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW FOR LEAVE TO FILE A

BRIEF AM ICUS CURIAE

Pursuant to Rule 36.3 of the Rules of this Court, the

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law (the “Law

yers’ Committee” ) respectfully moves for leave to file a brief

amicus curiae in support of respondents in the above-captioned

proceeding. In support of this motion, the Lawyers’ Committee

states:

1. Although respondents have consented to the filing

of the attached brief amicus curiae, the Lawyers’ Com

mittee has been unable to contact counsel for petitioners,

despite diligent efforts, to obtain their consent.

2

2. The Lawyers’ Committee has represented minor

ities and women in employment discrimination actions

nationwide. Many of these actions have concluded with

litigated or consensual orders providing remedial race

conscious relief. The position advocated by petitioners and

the Solicitor General as amicus curiae, if adopted by this

Court, could subject the decrees to which the Lawyers’

Committee’s clients—and many others—are parties to

endless, and we believe improper, attack. The Lawyers’

Committee has an essential interest in the vitality and

integrity of those decrees and believes that they should not

be undermined, or even threatened, by a change in the law

that would permit collateral attacks by persons who de

clined an opportunity to intervene.

3. In addition, the Lawyers’ Committee has special

expertise in the area of employment discrimination litiga

tion that may not be shared by all of the parties.

For the foregoing reasons, the Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law hereby respectfully requests that the

Court grant this motion for leave to file a brief amicus curiae in

support of respondents.

August 22, 1987

Respectfully submitted,

Paul C. Saunders

Counsel of Record

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

Conrad K. Harper

William L. Robinson

Judith A. Winston

Richard T. Seymour

Stephen L. Spitz

N orman Redlich

Trustee

Lawyers’ Committee for

Thomas D. Barr

Robert D. Joffe

Robert F. Mullen

Alden L. Atkins

Mark A. Sirota

James E. Fleming

Cravath, Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

(212) 422-3000

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

(Suite 400)

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for the Lawyers’

Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law as Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

T able of Authorities............................................................ ii

P roposed Brief of the Lawyers’ Committee for

C ivil R ights U nder Law as Am icus Curiae.......... 1

Interest of Am icus Cu r ia e ........................................... 1

Statement of the Ca se ......................................................... 3

Summary of the Argument........................ 5

A rgument.................................................................................. 6

I. P ersons W ho H ad N otice of A P roposed Con

sent D ecree and the O pportunity to Be H eard

Should N ot Be Allowed to Attack T hat D e

cree C ollaterally...................... 6

A. Public Policy Requires That Persons Who

Had the Opportunity to Be Heard Should Not

Be Allowed to Attack a Decree Collaterally.... 10

B. Settled Principles of Comity Between Federal

Courts Bar Attempts to Appeal the Ruling of

One District Court to Another Through

Collateral Proceedings....................................... 14

C. Petitioners’ Decision to Bypass Intervention in

the Hispanic Society Action Precludes Them

from Relitigating the Merits of the Consent

Decree................ ... ....................... ..................... 17

D. Rule 19 Does Not Require Parties to a Con

sent Decree to Join All Persons Who May Be

Affected by the Decree..................................... 21

E. Persons Who Had Notice of a Proposed De

cree and the Opportunity to Be Heard Have

No Due Process Right to Bring a Collateral

Action.................................................................. 24

II. In A ny Event, P etitioners’ Interests in the

H ispanic Society A ction W ere A dequately

R epresented by the P arties W ho W ere Present . 25

Conclusion ............................................................................... 28

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Adams v. Morton, 581 F.2d 1314 (9th Cir. 1978), cert,

denied, 440 U.S. 958 (1979) ........................................ 20

Aerojet-General Corp. v. Askew, 511 F.2d 710 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 908 (1975) ..................... 26

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) .. 12

American Civil Liberties Union v. Board of Educ. of

Maryland, 357 F. Supp. 877 (D. Md. 1972) ............... 22

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 ( 1965) ..................... 24

Ashley v. City of Jackson, 464 U.S. 900 (1983) ............... 10, 11

In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Employment

Litigation, 39 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1431

(N.D. Ala. 1985) .......................................................... 2

Bell v. Board of Educ., 683 F.2d 963 (6th Cir. 1982) .... 26

Black and White Children of the Pontiac School Sys. v.

School Dist., 464 F.2d 1030 (6th Cir. 1972) (per

curiam ).......................................................................... 14, 15

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972) ............ 23

Bolden v. Pennsylvania State Police, 578 F.2d 912 (3d

Cir. 1978) ...................................................................... 19-21,26

Brumfield v. Dodd, 425 F. Supp. 528 (E.D. La. 1976) .... 22

Chicago Rock Island & Pac. Ry. v. Schendel, 270 U.S.

611 (1926) .................................................................... 25

Common Cause v. Judicial Ethics Comm., 473 F. Supp.

1251 (D.D.C. 1979) ..................................................... 14

Construction Indus. Combined Comm. v. International

Union of Operating Eng’rs, Local 513, 67 F.R.D. 664

(E.D. Mo. 1975) ........................................................... 14-15

Corley v. Jackson Police Dep’t, 755 F.2d 1207 (5th Cir.

1985) ............................................................................. 11

Culbreath v. Dukakis, 630 F.2d 15 (1st Cir. 1980) ........ 10, 12

Cummins Diesel Michigan, Inc. v. The Falcon, 305 F.2d

721 (7th Cir. 1962) ....................................................... 20

Delaware Valley Citizens’ Council for Clean Air v.

Pennsylvania, 755 F.2d 38 (3d. Cir.), cert, denied,

106S.Ct. 67 (1985) ...................................................... 15

ii

Page

Page

Dennison v. City o f Los Angeles Dep’t o f Water &

Power, 658 F.2d 694 (9th Cir. 1981) ................. ......... 10-12

Deposit Bank v. Frankfort, 191 U.S. 499 (1903) .... . 15

EEOC v. American Tel. cfe Tel, 556 F.2d 167 (3d Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 ( 1978) ................ 14

Expert Elec., Inc. v. Levine, 554 F.2d 1227 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 903 ( 1977) ......... ...................... 25

Exxon Corp. v. Department o f Energy, 594 F. Supp. 84

(D. Del. 1984) ....... ............................................... ....... 16

Feller v. Brock, 802 F.2d 722 (4th Cir. 1986) ................ 14, 16

General Foods v. Department o f Public Health, 648 F.2d

784 ( 1st Cir. 1981) .... ................................................... 25-26

Goins v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 657 F.2d 62 (4th Cir.

1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 940 (1982) ................... 10,14-16

Grann v. City of Madison, 738 F.2d 786 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied, 469 U.S. 918 ( 1984) ........................................ 20

Gregory-Portland Indep. School Dist. v. Texas Educ.

Agency, 576 F.2d 81 ( 5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 440

U.S. 947 (1979) ............................................................ 14-16

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) .............................. 25, 26

Heckman v. United States, 224 U.S. 413 ( 1912) ........... 25

Hispanic Society v. New York City Police Dep’t, 40

Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) ff 36,385 (S.D.N.Y. 1986),

ajf’d, 806 F.2d 1147 (2d Cir. 1986), cert, granted,

107 S. Ct. 2177, amended, 107 S. Ct. 3182 ( 1987) ..... 13,27

Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956 (1 1th Cir. 1986) ..... 11,18

Kerrison v. Stewart, 93 U.S. 155 ( 1876)................. ....... 25

Kirkland v. Department o f Correctional Servs., 711 F.2d

1117 (2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 465 U.S. 1005

(1984) ........................................................................... 17

Kremer v. Chemical Constr. Co., 456 U.S. 461 (1982) ... 7-8, 24

LaRouche v. FBI, 677 F.2d 256 (2d Cir. 1982) ............ 17

Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers ’ In t’l Ass’n v. EEOC,

106S. Ct. 3019 (1986) ................................................. 9-10

IV

Local 93. In t’l Ass’n o f Firefighters v. City o f Cleveland,

106 S. Ct. 3063 (1986) ................................................. 10-12

Marine Power & Equip. Co. v. United States, 594 F.

Supp. 997 (D.D.C. 1984) ............................................. 20

Matthews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 ( 1976) .................... 24

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S.

306 (1950) ..................................................... ............... 24

Nash County Bd. o f Educ. v. Biltmore Co., 640 F.2d 484

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 878 ( 1981) ............. 25

National Wildlife Fed’n v. Gorsuch, 744 F.2d 963 (3d

Cir. 1984) ...................................................................... 20,21

O’Burn v. Shapp. 70 F.R.D. 549 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d mem.,

546 F.2d 418 (3d Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 430 U.S.

968 (1977).................................................................... 10-12

Penn-Central Merger and N&W Inclusion Cases, 389

U.S. 486 (1968) ............................................................ 19

Phillips v. Carborundum Co., 361 F. Supp. 1016

( W.D.N.Y. 1973) ......................................................... 23

Prate v. Freedman, 430 F. Supp. 1373 (W.D.N.Y.),

aff’d mem., 573 F.2d 1294 (2d Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 436 U.S. 922 (1978) ........................................ 8, 10, 12, 17

Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978) ............. 8, 17

Provident Tradesmens Bank & Trust Co. v. Patterson,

390 U.S. 102 (1968) ..................................................... 19

Safir v. Dole, 718 F.2d 475 (D.C. Cir. 1983), cert,

denied, 467 U.S. 1206 ( 1984) ...................................... 19

Schmieder v. Hall, 545 F.2d 768 (2d Cir. 1976), cert,

denied, 430 U.S. 955 ( 1977) ........................................ 12

Southwest Airlines Co. v. Texas In t’l Airlines, 546 F.2d

84 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 832 ( 1977) ........ 26

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257 (5th Cir.

1977) ............................................................................. 18

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dep’t, 679 F.2d 541 (6th Cir.

1982), rev d sub nom. Firefighters Local Union No.

1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 ( 1984) ............................ 10

Page

V

Page

System Fed’n v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (1961) ................ 15

Telephone Workers Union, Local 827 v. New Jersey Bell

Tel, 584 F.2d 31 (3d Cir. 1978) .................................. 25-26

Thaggard v. City of Jackson, 687 F.2d 66 (5th Cir.

1982), cert, denied sub nom. Ashley v. City o f Jackson,

464 U.S. 900 (1983) ..................................................... 10-12

Treadway v. Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences,

783 F.2d 1438 (9th Cir. 1986) ................................ . 16

Treasure Salvors, Inc. v. Unidentified Wreck, 459 F.

Supp. 507 (S.D. Fla. 1978), aff’d sub nom. Florida

Dep’t o f State v. Treasure Salvors, Inc., 621 F.2d

1340 (5th Cir. 1980), ajf’d in part and rev’d in part,

458 U.S. 670 (1982) .......................... .......................... 20

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Indus., 517 F.2d 826

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1975) ............. 14

United States v. Geophysical Corp., 732 F.2d 693 (9th

Cir. 1984) .............. ....................................................... 25

United States v. Jefferson County, 720 F.2d 1511 (11th

Cir. 1983) ...................................................................... 10

United States v. Hooker Chem. & Plastics Co., 540 F.

Supp. 1067 (W.D.N.Y. 1982) ....................................... 17-18

United Airlines v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 ( 1977) ....... 27

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932) ........ 15

United States v. Texas, 330 F. Supp. 235, a ff’d and

modified, 447 F. 2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 1016 (1972) ................................................... 15

United States v. Yonkers Bd. o f Educ., 801 F.2d 593 (2d

Cir. 1986) ...................................................................... 18

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 ( 1977) ....................... 18

Western Coal Traffic League v. ICC, 735 F.2d 1408

(D.C. Cir. 1984) ........................................................... 25

VI

Statutes, R ules and R egulations:

28 U.S.C. § 112(c) ......................................................... 14

28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) ......................................................... 16

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) .................................................... 12

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(l) ............................................... 7

FedR. Civ. P. 19.................... .......................................... 5,9,21-23

Fed R. Civ. P. 4 2 ............................................................... 16

Rule 15, Rules for the Division of Business Among

District Judges, Southern District of New York ....... 4

29 C.F.R. § 1608.1(b) (1986) ......................................... 12

Other Authorities:

F. James & G. Hazard, Civil Procedure § 11.31 (2d ed.

1977) ..................... ....................................................... 20

New York Times, August 13, 1986 at B8 ....................... 10

Note, Preclusion of Absent Disputants to Compel Inter

vention, 79 Colum. L. Rev. 1551 (1979) .................... 20

Schwarzschild, Public Law by Private Bargain: Title VII

Consent Decrees and the Fairness of Negotiated In

stitutional Reform, 1984 Duke L. J. 887 ..................... 13

Page

No. 86-1415

In The

(Eourt n! tljr llniteft States

O ctober Term 1987

Evelyn M arino, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

Juan V. Ortiz, et al.,

Respondents.

and

W ayne Costello, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

N ew Y ork City P olice D epartment, et al.,

Respondents.

On W rit of C ertiorari to the

U nited States Court of A ppeals for the Second C ircuit

PROPOSED BRIEF OF THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AM ICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AM ICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law (the

“Lawyers’ Committee” ) is a nationwide civil rights organiza

tion that was formed in 1963 at the request of President

Kennedy to provide legal representation to blacks who were

2

being deprived of their civil rights. The national and local

offices of the Lawyers’ Committee have represented the inter

ests of blacks, Hispanics and women in hundreds of class

actions relating to employment discrimination, voting rights,

equalization of municipal services and school desegregation.

Many of those lawsuits have led to remedial orders contained in

consent decrees or in court orders entered after fully litigated

trials.

Some of those consent decrees and orders are being

challenged in collateral proceedings. For example, in Birming

ham, Alabama, the Lawyers’ Committee, on behalf of blacks,

and the Department of Justice sued the City of Birmingham

and the Jefferson County Personnel Board for employment

discrimination. After seven years of litigation, including two

trials and one appeal, the parties entered into consent decrees

containing race-conscious relief. Nonminorities have chal

lenged those decrees in collateral lawsuits, subjecting the

parties to those decrees thus far to six additional years of

litigation. The Department of Justice, although a party to the

original decrees, has brought its own “reverse discrimination”

suits and has supported the collateral attacks. See generally In

re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination Employment Litigation,

39 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1431 (N.D. Ala. 1985).

The position asserted here by petitioners and the Solicitor

General, if accepted, may lead to collateral challenges of other

decrees to which our clients—and many others—are parties. As

has proven true in the Birmingham litigation, the litigation

would be endless. The result could be catastrophic.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE^

In 1984, the Hispanic Society and the Guardians Associa

tion sued the New York City Police Department and other

municipal defendants, alleging that the promotional exam

ination for the position of Police Sergeant was racially dis

criminatory (these actions will be referred to collectively as the

“Hispanic Society action” ). Three groups intervened in the

Hispanic Society action: the Sergeants’ Benevolent Association,

on behalf of officers who had been provisionally appointed to

Sergeant from the list of eligible persons who had passed the

examination; the Sergeants Eligibles Association, on behalf of

officers who were on the eligible list but who had not yet been

promoted; and the “Schneider Intervenors”, on behalf of other

nonminority officers.

After extensive discovery, the municipal defendants con

cluded that the examination had an adverse impact on minor

ities and that they might not be able to prove that the

examination was job related, and settlement negotiations en

sued. All of the parties except the Schneider Intervenors

entered into an interim settlement that provided (1) that

persons on the eligible list would be promoted and (2) that

additional minority officers would be promoted until the per

centage of minorities promoted equalled the percentage of

minorities who took the examination. The district court

approved the interim settlement in an order dated November

27, 1985. J.A. 45-48.1 2 The parties entered into a consent decree

that had the effect of continuing and formalizing the interim

1 We summarize only so much of the factual and procedural

history of the case as is relevant to the argument made in this brief.

We respectfully refer the Court to the statements of the case of the

respondents in their respective briefs and to the decisions of the courts

below for a comprehensive review of the facts.

2 The form of citations is as follows: the Brief of Petitioners is

cited as “Petitioners’ Br.”; the Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae is cited as “Gov’t Br.”; the Joint Appendix is cited as “J.A.”;

the appendix to the petition for certiorari is cited as “Pet. App.”; and

the Record on Appeal in Marino is cited as “R.”.

4

order, and the district court ordered that notice of the proposed

consent decree be given to members of the plaintiff and

intervenor classes and posted in every police precinct in New

York City. J.A. 84. Persons who objected to the proposed

consent decree were invited to participate in a settlement

hearing. J.A. 50.

After the interim order but before the settlement hearing,

Evelyn Marino, et al., (the “Marino petitioners” ), sued New

York City, alleging that the promotion of minorities with

examination scores below their own scores violated their rights

under Title VII and the Equal Protection Clause of the United

States Constitution (the “Marino action” ). Over the opposition

of the Marino plaintiffs (R. 49-50), the Marino action was

transferred to Judge Carter, who was presiding over the

Hispanic Society action, pursuant to a local rule providing that

the same judge should hear related cases.3 For unknown

reasons, although the municipal defendants explicitly invited

the Marino petitioners to intervene in the Hispanic Society

action rather than to maintain a separate lawsuit, they did not

do so. R. 15; Pet. App. 37. Judge Carter therefore dismissed

the Marino action as an impermissible collateral attack on the

interim order and the proposed consent decree, and the court of

appeals affirmed.

At the settlement hearing, the same lawyer who represent

ed the plaintiffs in Marino objected to the proposed decree on

behalf of Wayne Costello, et al., (the “Costello petitioners” ),

who apparently include the Marino petitioners and all others

similarly situated. Petitioners’ Br. at 11. Those petitioners also

elected not to intervene in the Hispanic Society action. Judge

Carter approved the consent decree over their objections. Pet.

App. 80-99. The Costello petitioners sought to appeal, but

since they were, by their own choosing, not parties, the court of

appeals dismissed the appeal.

3 See Rule 15, Rules for the Division of Business Among District

Judges, Southern District of New York.

5

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The well-established rule prohibiting collateral attacks by

persons who received notice of a proposed consent decree and

had an opportunity to intervene should be applied here to

affirm the decisions below. The petitioners had actual notice of

the proposed consent decree and were heard in opposition to

that decree. They were given the opportunity—indeed, were

invited—to intervene, but they deliberately chose not to do so.

Having been given notice and the opportunity to be heard,

petitioners should not be allowed to maintain a collateral

lawsuit challenging that decree.

The policies supporting the rule are well known: collateral

attacks create the possibility that the parties to a decree could

be subjected to inconsistent court orders; they allow persons to

relitigate issues that were or could have been litigated before;

they undermine the authority of federal courts to issue orders

and judgments; and they discourage parties from settling Title

VII cases. In addition, a collateral attack necessarily calls upon

a court to reconsider a judgment in another lawsuit that may

have been entered by another judge or even by another court.

This violates settled rules of comity, a principle that the rule

prohibiting collateral attacks is designed to protect.

The Solicitor General argues for a broad—and, we believe,

an unnecessary and dangerous—change in the law'. Five years

ago, the Solicitor General argued that collateral attacks should

not be allowed and articulated sound policy reasons for that

position. Now, he argues that they should always be permitted.

The Solicitor General’s current position would jeopardize all

Title VII consent decrees, rendering them uncertain and throw

ing them open to endless collateral attacks. There is no valid

reason, either in law or logic, for that position.

Both the Solicitor General and petitioners also now argue

that the parties to the consent decree should have joined

petitioners pursuant to Rule 19. Petitioners did not raise that

argument below; in fact, they did everything they could in the

district court to avoid becoming parties. Nor is there any

6

reason why they should have been joined. Rule 19 does not

require joinder of all persons who may eventually come to

believe that they have been affected by the outcome of litiga

tion. Obviously, the parties cannot join persons whose interests

are inchoate or persons, like petitioners, who have no legitimate

interest in the decree at all. Moreover, joining everyone who

might conceivably be interested would be unwieldy at best,

because the number of potentially interested persons may be

quite large, and impossible at worst, because those being joined

(or their class representative) may not want to be bound by the

decree.

Requiring persons with notice of the decree to intervene,

rather than requiring them to be joined, does not deny them

any due process rights. The Due Process Clause only requires

that persons be given notice and the opportunity to be heard.

Petitioners had both.

Finally, this Court has long recognized that the parties to a

lawsuit can virtually represent the interests of others who are

absent, thus binding them. Here, the vague interests of

petitioners, who would not have been promoted with or without

the consent decree, were well represented by persons with far

more substantial interests.

ARGUMENT

I. PERSONS WHO HAD NOTICE OF A PROPOSED

CONSENT DECREE AND THE OPPORTUNITY TO BE

HEARD SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED TO ATTACK

THAT DECREE COLLATERALLY.

At issue is whether persons who claim to be affected by a

consent decree, had notice of the decree, participated in the

settlement hearing and had an opportunity to intervene but

declined to do so, may attack that decree in a collateral lawsuit.

We urge that they may not.

The general rule in this country has been that collateral

attacks are, if not always impermissible, at least highly dis-

7

favored. Until recently, that rule had the vigorous support of

the Department of Justice. Those few courts that have per

mitted collateral attacks have made it clear that if they are to be

permitted at all, they should be a procedure of last resort,

available only to those who did not have an opportunity—or

were unfairly refused an opportunity—to intervene in the first

case. It is obvious in this case that the petitioners deliberately

chose not to intervene in the first case, but instead to launch a

collateral attack as a tactic of first, rather than last, resort. That

should not be permitted.

But what is of even more concern to us is that the Solicitor

General is arguing here for a rule of broad applicability that

would permit collateral attacks by nonparties under all circum

stances. Such a rule might have far-reaching and potentially

disastrous consequences for women and minorities who have

received the benefit of consent and litigated decrees redressing

the effects of years of racial and gender-based discrimination.

We agree that persons who are affected by and wish to

challenge the relief contained in a proposed consent decree

should be given reasonable notice and the opportunity to

intervene before the court considers the lawfulness of the

proposed decree. But if they deliberately forego that oppor

tunity, they should not be allowed to attack the decree

collaterally.

There is nothing inherently unfair in a rule that precludes

collateral attack by those who did not first seek to intervene,

absent, of course, extraordinary circumstances. The fact that

the would-be attackers may lose their day in court by deliber

ately choosing not to intervene ought to be of no concern. It

often happens that persons who sit on their rights, or who elect

the wrong forum in which to assert them, lose them. For

example, employment discrimination plaintiffs who do not sue

within 90 days after receiving a “ right to sue” letter forever lose

their right to a day in court. See Title VII § 5(f)( 1), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(f)( 1). In fact, a person may lose the opportunity for

a day in court by making an election with consequences that

were not foreseen. See Kremer v. Chemical Constr. Corp., 456

8

U.S. 461, 485 (1982) (plaintiff’s decision to appeal a state

agency’s rejection of his employment discrimination claim to a

state court, rather than to press his claim before the EEOC,

barred a subsequent Title VII suit).

Here, unlike the situation in Kremer, the petitioners should

have known full well that the consequence of their failure to

intervene was that their collateral attack would be precluded.

The law in the Second Circuit has been clear and unambiguous

on that point for years. See Prate v. Freedman, 573 F.2d 1294

(2d Cir. 1977), aff’g mem., 430 F. Supp. 1373 (W.D.N.Y.),

cert, denied, 436 U.S. 922 ( 1978); see also Prate v. Freedman,

583 F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978) (awarding attorneys fees against

plaintiffs who collaterally attacked a consent decree). Petition

ers knew, or should have known, that by failing to intervene,

they would lose their day in court, it is the opportunity to be

heard, not an actual hearing, to which petitioners were entitled.

Having foregone the former, petitioners had no right to the

latter.

The facts of this case are somewhat peculiar. It is hard to

understand why petitioners deliberately elected not to intervene

in the face of controlling Second Circuit precedent. The Marino

petitioners can hardly argue that because their separate lawsuit

was transferred to Judge Carter, they had effectively intervened,

since they actively opposed that transfer. See R. 49-50. This

case is also unusual in that the collateral attack was made six

months before the decree under attack became final, giving

petitioners more than ample opportunity to make their voices

heard in the proper way. We do not know why they did not do

so. Equally perplexing is the fact that the petitioners did not

actually lose anything by the consent decree to which they

objected. The merits of their collateral attack border on the

frivolous.

Because of those and other peculiarities, this case could

well be decided on a basis that would limit the decision to the

unusual facts of the case. Our concern, however, is that if for

any reason this case is reversed and remanded, it may be seen

as opening the doors wide to permit collateral attacks on all

consent decrees or final orders by disgruntled white employees.

9

Our fear is heightened by the unnecessarily broad sweep of the

position taken by the Solicitor General.

The Solicitor General now argues that collateral attacks

should be permitted by anyone who was not a party to the

original decree. Moreover, he argues that the parties ought to

have an affirmative obligation under Rule 19 to join anyone

who might later seek to attack a decree. See Gov’t Br. at 17-19.

That argument turns procedure and common sense on its head

and is dangerous. The Solicitor General argues that petitioners’

deliberate decision not to intervene should not preclude their

collateral attack and that the real problem was created by

respondents’ failure to join petitioners as parties. There can be

no rational explanation for such a backwards argument. In

deed, the Solicitor General took a flatly contrary position just

five years ago before this very Court:

“To permit independent lawsuits challenging the

validity of consent decrees over which a court has retained

jurisdiction would foster an unnecessary proliferation of

lawsuits, create a needless danger of inconsistent or con

tradictory adjudications, and create uncertainty as to a

decree’s validity and finality. The rule against collateral

attacks is necessary and appropriate to enable the court,

which has approved the entry of the decree and is thus in

the best position to judge whether changed circumstances

warrant its modification, to ensure the decree’s just and

orderly implementation.” Brief for the United States in

Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Ashley v. City

of Jackson, No. 82-1390 ( 1982) at 4 (citations omitted).

One can speculate as to why the Solicitor General has

changed his position. The Department of Justice is a party to at

least fifty employment discrimination decrees containing race

conscious relief. It is no secret that the Department of Justice is

unhappy with those decrees and has sought to reopen many of

them. It was only after this Court rejected the Solicitor

General’s argument that race-conscious relief for nonvictims of

discrimination is always improper {see Local 28, Sheet Metal

10

Workers’ In t’l Ass’n v. EEOC, 106 S. Ct. 3019, 3035, 3054,

3062-63 (1986); Local 93, In t’l Ass’n of Firefighters v. City of

Cleveland, 106 S. Ct. 3063, 3073 ( 1986) (“Local 93’’)), that

the Department of Justice has taken the position that non

minorities should be allowed to attack collaterally consent

decrees that contain race-conscious relief and has encouraged

attacks on decrees to which it is a party. See New York Times,

August 13, 1986 at B8 (attached hereto as Appendix A).

Permitting unlimited collateral attacks would threaten each of

those decrees, thus rendering them tentative and uncertain. In

sum, the Department of Justice is seeking to do indirectly what

it has so far failed to do directly.

A. Public Policy Requires That Persons Who Had

the Opportunity to Be Heard Should Not Be Allowed

to Attack a Decree Collaterally.

The overwhelming majority of lower federal courts have

held that a Title VII consent decree cannot be collaterally

attacked by a person who had notice and the opportunity to be

heard in opposition to its entry. See Thaggard v. City of

Jackson, 687 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1982), cert, denied sub nom.

Ashley v. City o f Jackson, 464 U.S. 900 (1983); Stotts v.

Memphis Fire Dep’t, 679 F.2d 541, 558 (6th Cir. 1982), rev’d

on other grounds sub nom. Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v.

Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984); Goins v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.,

657 F.2d 62 (4th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 940 ( 1982);

Dennison v. City o f Los Angeles Dep’t o f Water & Power, 658

F.2d 694, 696 (9th Cir. 1981); Culbreath v. Dukakis, 630 F.2d

15, 22-23 ( 1st Cir. 1980); Prate v. Freedman, 430 F. Supp. 1373

(W.D.N.Y.), aff’d mem., 573 F.2d 1294 (2d Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 436 U.S. 922 ( 1978); O’Burn v. Shapp, 70 F.R.D. 549,

552-53 (E.D. Pa.), aff’d mem., 546 F.2d 418 (3d Cir. 1976),

cert, denied, 430 U.S. 968 (1977).4 Compelling policy justifica

tions support that rule.

4 The Eleventh Circuit’s position is unclear. In United States v.

Jefferson County, 720 F.2d 1511, 1518 (11th Cir. 1983), the court

suggested that it disagreed with the doctrine that a collateral attack is

not permissible “to the extent that it deprives a nonparty to the decree

of his day in court”. In a later case, the same court said that the

lawfulness of a consent decree would be “foreclosed in a separate

11

First, permitting collateral attacks on a decree, especially

one containing mandatory injunctive relief, would create the

risk of imposing inconsistent obligations on the employer. This

Court has previously recognized that allowing a court other

than the one that entered the decree to interpret or modify it

would create a “risk of inconsistent or conflicting obligations”.

Local 93, 106 S. Ct. at 3076 n.13; accord Thaggard, 687 F.2d at

68; O’Burn, 70 F.R.D. at 552; Dennison, 658 F,2d at 695; see

also pp. 15-16, infra. The relief that the Marino petitioners

seek illustrates this danger. The consent decree provides for

additional minorities to be promoted in order to overcome the

adverse impact of the examination, yet the relief that petitioners

seek—the promotion of additional nonminorities—would nec

essarily undo the decree’s remedy and recreate the exam

ination’s adverse impact.

The Solicitor General recognizes those policies but argues

that “the concern for correctness of judicial decision making is

as important as the concern for consistency among judgments

and, accordingly, some inconsistent or contradictory judgments

must be accepted”. Gov’t Br. at 20. This is not, however, a

case in which the decree amounts to “little more than a contract

between parties, formalized by the signature of a judge”.

Ashley v. City o f Jackson, 464 U.S. at 902 ( Rehnquist, J.,

dissenting from the denial of certiorari). The district court

allowed interested parties—including three groups representing

white employees whose interests were concrete—to be heard,

considered their arguments and held that the decree was lawful.

If a collateral challenge is allowed under such circumstances,

there is no reason to believe that a second decision would be

any more likely to be “correct” than the first.

reverse discrimination suit”. Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956, 960

(11th Cir. 1986).

Similarly, although the Fifth Circuit has suggested that the

Thaggard line of cases should be reexamined if under the facts of a

particular case a party is denied its day in court, that court remains

“firmly bound” to the Thaggard rule where an opportunity to be

heard was available. Corley v. Jackson Police Dep’t, 755 F.2d 1207,

1210 (5th Cir. 1985).

12

Second, collateral attacks on decrees where objectors had

the right to intervene would permit relitigation of issues that

already had been, or could have been, litigated. Judicial

resources are an increasingly scarce commodity (see Schmieder

v. Hall, 545 F.2d 768, 771 (2d Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 430 U.S.

955 (1977)), and allowing collateral lawsuits by persons who

could have intervened earlier unnecessarily wastes those pre

cious resources. In this case, the district court considered and

rejected petitioners’ arguments, and there is no reason why

another court should have to consider those arguments again.

Third, allowing collateral attacks would undermine the

authority of the federal courts to issue judgments. If collateral

attacks were permitted, “courts could never enter a judgment in

a lawsuit with the assurance that the judgment was a final and

conclusive determination of the underlying dispute”. O’Burn,

70 F.R.D. at 552; see also Thaggard, 687 F.2d at 69; Prate, 430

F. Supp. at 1375. Indeed, because a consent decree is a court

order ( Local 93, 106 S. Ct. at 3074), it stands to reason that

allowing consent orders to be attacked would also subject final

litigated orders and judgments to collateral attack.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, permitting collat

eral attacks would have the perverse effect of discouraging the

settlement of meritorious Title VII claims. Prate, 430 F. Supp.

at 1375; Dennison, 658 F.2d at 696; Thaggard, 687 F.2d at 69.

This Court has previously recognized that when Congress

passed Title VII, “ [cjooperation and voluntary compliance

were selected as the preferred means for achieving” equal

employment opportunity. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974); see also Local 93, 106 S. Ct. at 3072; 29

C.F.R. § 1608.1(b) (1986) (EEOC Affirmative Action Guide

lines). Settlement serves the policy of encouraging employers

to end discriminatory employment practices as quickly as pos

sible. See Title VII § 705(b), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) (1982)

(providing for the expedited consideration of Title VII suits);

Culbreath, 630 F.2d at 22. In addition, because it is negotiated

rather than imposed unilaterally by a court, a settlement that

resolves the lawfulness of employment practices once and for

13

all dispels uncertainties and may be accepted by employees

more readily. See Schwarzschild, Public Law by Private

Bargain: Title VII Consent Decrees and the Fairness o f Nego

tiated Institutional Reform, 1984 Duke L.J. 887, 899; see also

Hispanic Society v. New York City Police Dep’t, 40 Empl. Prac.

Dec. (CCH) H 36,385 (S.D.N.Y.), aff’d, 806 F.2d 1147 (2d

Cir. 1986), cert, granted, 107 S. Ct. 2177, amended, 107 S. Ct.

3182 (1987).

Permitting all Title VII decrees to be collaterally attacked,

whatever the circumstances, would vitiate that powerful legal

tool. If the benefits that the parties obtain by settling—relief

(for plaintiffs) and repose (for defendants)—can be collat

erally challenged, parties would have little to gain by settling

and giving up their claims or defenses.

The Solicitor General argues that allowing collateral at

tacks would not diminish the employer’s incentive to settle any

more than does allowing nonminorities to intervene in the

original action. See Gov’t Br. at 23. The Solicitor General goes

so far as to say that the “parties’ incentive to settle would be

increased, if at all, only if the Marino petitioners had no means

of challenging any settlement”. Id. at 23 n. 13. That is simply

not true. Intervenors have the right to challenge a proposed

decree—by opposing the decree at the settlement hearing and

by appealing an adverse decision. The disincentive to settle if

collateral attacks were allowed would come not from the fact

that a proposed consent decree could be challenged, but rather

from the fact that even if the decree were challenged, approved

and affirmed on appeal, the employer might still have to defend

any number of collateral lawsuits.

14

B. Settled Principles of Comity Between Federal

Courts Bar Attempts to Appeal the Ruling of One

District Court to Another Through Collateral Pro

ceedings.

Collateral attacks, if allowed, necessarily call upon a court

to reconsider an earlier judicial decision in an earlier case,

perhaps by a different judge or even by a different court. That

violates firmly settled rules of comity.

Although in this case the collateral challenge was consid

ered by the same judge who approved the consent decree, that

was purely fortuitous.5 There are many consent decrees that

cover an employer’s practices nationwide. See, e.g., United

States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Indus., 517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir.

1975) ( consent decree covering nationwide practices in the

steel industry), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 944 (1976); EEOC v.

American Tel. & Tel., 556 F.2d 167 (3d Cir. 1977) (consent

decree covering nationwide employment practices of the Bell

companies), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 ( 1978). If the Solicitor

General’s argument were to prevail, those consent decrees

would be exposed to collateral attacks in every district court in

the country. Indeed, collateral attacks on consent decrees are

often brought in a different court than the one that entered the

original order. See, e.g., Gregory-Portland Indep. School Dist. v.

Texas Educ. Agency, 576 F.2d 81 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

440 U.S. 947 (1979); Goins, 657 F.2d 62; Black and White

Children of the Pontiac School Sys. v. School Dist., 464 F.2d

1030 (6th Cir. 1972) (per curiam) (“Black and White School

Children”)-, Feller v. Brock, 802 F.2d 722, 727-28, (4th Cir.

1986); Common Cause v. Judicial Ethics Comm., 473 F. Supp.

1251, 1253-54 (D.D.C. 1979); Construction Indus. Combined

5 Because three of the five boroughs of New York City are in the

Eastern District of New York (28 U.S.C. § 112(c)), the Marino

action could have been brought in another district. In addition, even

though the Marino action was brought in the same court in which the

Hispanic Society action was pending, the Marino action was trans

ferred to Judge Carter only by virtue of local practice. See p. 4, supra;

accord Gov’t Br. at 15 n.6. The same result would not necessarily

obtain in other districts with other local practices.

15

Comm. v. International Union of Operating Eng’rs, Local 513.

67 F.R.D, 664, 665-66 (E.D. Mo. 1975).6

A collateral attack on the decree of a court of competent

jurisdiction in another forum has long been held improper

because a court of equity retains continuing jurisdiction over the

enforcement of its orders ( System Fed’n v. Wright, 364 U.S.

642, 646-48 (1961 ); United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106,

114-15 ( 1932)) and the power to modify its decree based on

changed circumstances of law or fact (see Swift, 286 U.S. at

114-15). See Deposit Bank v. Frankfort, 191 U.S. 499, 510-15

( 1903); Delaware Valley Citizens’ Council for Clean Air v.

Pennsylvania, 755 F.2d 38, 43-44 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 106 S.

Ct. 67 ( 1985). The specter of different district courts wrestling

over the fate of school children in a busing controversy,

reviewing a school district’s efforts to desegregate or issuing

orders concerning an employer’s promotion policies are pre

cisely the types of dilemmas that comity is designed to avoid.

See, e.g., Goins, 657 F.2d 62; Gregory-Portland, 516 F.2d 81;

Black and White School Children, 464 F.2d 1030. Courts today

deal with such problems daily under existing rules. To adopt

the Solicitor General’s proposal would open a Pandora’s Box

with unknown, but certainly undesirable, consequences.

The rule that collateral attacks generally should not be

permitted is the tool used by courts to enforce comity. By

avoiding relitigation of issues already examined in another 6

6 For example, in Gregory-Portland, the United States brought a

school desegregation action in the Eastern District of Texas against

the Texas Education Agency (“TEA”). The district court enjoined

the TEA from funding or accrediting school districts that dis

criminated on the basis of race. See United States v. Texas, 330 F.

Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex.), aff’d and modified, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 1016 ( 1972). Gregory-Portland sued

the TEA in the Southern District of Texas alleging that the threatened

termination violated its due process. The Southern District agreed,

and permanently enjoined the TEA from suspending Gregory Port

land’s accreditation or funding. The Fifth Circuit reversed on the

ground that comity required that any challenge to the Eastern

District’s order be brought in that court, which had continuing

jurisdiction. See Gregory-Portland, 576 F.2d at 83.

16

forum, the rule avoids waste of judicial time and effort. It

serves litigants as well, by channelling their disputes to a court

that is aware of the background of the litigation and has

already exercised its powers in the matter. Finally, it engenders

respect for the orders of federal courts.

Comity applies regardless of whether the plaintiff in the

collateral suit was a party or privy to the initial action. See

Treadway v. Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, 783

F.2d 1418, 1421-22 (9th Cir. 1986); Goins, 657 F.2d at 64;

Gregory-Portland, 576 F.2d at 82-83; Feller, 802 F.2d at 728.

For example, in Feller, the NAACP brought an action in the

District of Columbia challenging the Department of Labor’s

(“DOL”) administration of the Temporary Foreign Worker

Program. Under that program, the DOL could certify that an

employer could hire alien workers, provided that the employer

paid them the Adverse Effect Rate (“AER”). The NAACP

alleged that the DOL had certified employers who paid aliens

less than the AER. The district court enjoined the DOL from

certifying noncomplying employers, and, pursuant to that or

der, the DOL refused to certify two West Virginia apple

growers. Those two growers sued the DOL in West Virginia

and obtained an order that they be certified, and the DOL

complied. The NAACP then sought to hold the DOL in

contempt in the District of Columbia action. The Fourth

Circuit reversed the West Virginia court’s injunction, noting

that comity “has been expanded . . . to cases in which the

plaintiff in the second action was neither a party nor the

successor-in-interest of a party in the first action”. Id. at 728;

see also Goins, 657 F.2d at 64; Exxon Corp. v. Department of

Energy, 594 F. Supp. 84, 89-90 (D. Del. 1984).

The Solicitor General’s response to these threats to comity

is twofold. First, the Solicitor General argues that a collateral

attack could be transferred to the district court in which the

decree was entered (see 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a)) and transferred

to the same judge (see Fed. R. Civ. P. 42). See Gov’t Br. at 14.

But requiring the plaintiff to litigate in the consent decree forum

imposes no greater burden than requiring him or her to

17

intervene in the consent decree action in the first place. Second,

the Solicitor General argues that “principles of stare decisis and

comity will inform the second court”. Gov’t Br. at 20 ( empha

sis added). Saying that the second court will be “informed”

begs the question. The second court is either bound by the first

decision or free to reconsider it. To the extent that it must

follow the earlier decision, the collateral attack is a hollow

procedural device. To the extent that it can reconsider the

initial order de novo, comity is meaningless.

C. Petitioners’ Decision to Bypass Intervention in

the HISPANIC S o c ie ty Action Precludes Them from

Relitigating the Merits of the Consent Decree.

Petitioners are decidedly not persons who have been

denied their day in court. They were heard at the settlement

hearing. They were invited to intervene. They knew, or should

have known, that they would be barred from challenging the

decree unless they intervened. The Second Circuit had pre

viously ruled that consent decrees cannot be collaterally at

tacked (see Prate v. Freedman, 573 F.2d 1294 (2d Cir. 1977),

ajf’g mem., 430 F. Supp. 1373 (W.D.N.Y.)), and had consid

ered its rule so clear that it awarded attorneys fees against

plaintiffs seeking to attack a consent decree collaterally. See

Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d at 46.

Had the Marino petitioners sought to intervene in the

Hispanic Society action, their application would have been

granted under the law of the Second Circuit. See Kirkland v.

Department of Correctional Servs., 711 F.2d 1117, 1128 (2d

Cir. 1983) (nonminority employees may intervene after a

consent decree is proposed because their interest in a promotion

“entitles [them] to be heard on the reasonableness and legal

ity” of the decree), cert, denied, 465 U.S. 1005 ( 1984).7 The

7 See also LaRouche v. FBI, 677 F.2d 256, 257 (2d Cir. 1982)

(allowing intervention two years after entry of a decree where

intervenor had been unaware of the litigation and delay would not

prejudice the other parties); United States v. Hooker Chem. & Plastic

Corp., 540 F. Supp. 1067, 1082 (W.D.N.Y. 1982) (approving

18

Solicitor General’s reliance on United States v. Yonkers Bd. of

Educ., 801 F.2d 593 (2d Cir. 1986), for the proposition that

intervention would have been denied (see Gov’t Br. at 24-25) is

nothing short of remarkable. Yonkers involved an attempt by

homeowners to intervene in a desegregation action to oppose

the construction of public housing near their homes several

years after they were on notice that their neighborhoods were

proposed sites for the construction, after months of inquiry and

after six days of extensive hearings. Id. at 595. The Second

Circuit affirmed the denial of intervention because the home-

owners’ decision not to participate in those proceedings ren

dered their motion to intervene untimely. The court suggested

that intervention would have been granted if the homeowners

had sought to enter the action after the filing of the proposed

decree but prior to the hearing. Id. at 596. To argue that

because intervention was denied as untimely in one case, it

would have been denied in this case—before the decree was

signed and before the settlement hearing was held—is simply to

misstate the law of the Second Circuit.

To be sure, the time when a party raises a claim has always

been important. In considering collateral attacks on state court

criminal judgments through habeas corpus, courts have been

particularly unsympathetic to defendants who save their con

stitutional claims until after their state court trials. See

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 (1977). In Wainwright, this

Court established the “cause and prejudice” rule, stating that a

more lenient rule “may encourage ‘sandbagging’ on the part of

defense lawyers, who may take their chances on a verdict of not

guilty in a state trial court with the intent to raise their

constitutional claims in a federal habeas court if their initial

gamble does not pay off”. Id. at 89 ( Rehnquist, J.).

Petitioners’ refusal to intervene was not, as the Solicitor

General would have it, a free choice. This Court has long

intervention after the proposed decree was filed); Howard, 782 F.2d

956 (same); Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d 257, 266-68 (5th

Cir. 1977) (allowing intervention one month after entry of the

consent decree).

19

recognized that parties with actual notice of a lawsuit affecting

their interests may be bound by its results if they do not

intervene to defend those interests. For example, in Penn-

Central Merger and N&W Inclusion Cases, 389 U.S. 486

(1968), the Borough of Moosic brought an action in the Middle

District of Pennsylvania seeking to enjoin the Penn-Central

merger, one of several such actions filed in various district

courts nationwide. All of the actions were stayed pending

disposition of the common issues by a three judge panel in the

Southern District of New York. The Southern District app

roved the merger, and this Court affirmed that judgment. This

Court then held that the Borough of Moosic was precluded

from relitigating the merits of the approval of the merger in its

Pennsylvania action because it “had an adequate opportunity to

join in the [New York] litigation”. Id. at 505. The Court

stated:

“All parties with standing to challenge the Commission’s

action might have joined in the New York proceedings. In

these circumstances, it necessarily follows that the decision

of the New York court. . . precludes further judicial review

or adjudication of the issues upon which it passes.” Id. at

505-06 (footnote omitted).

Similarly, in Provident Tradesmens Bank & Trust Co. v.

Patterson, 390 U.S. 102 ( 1968), the Court rejected the argu

ment that indispensable parties have a “substantive right” to be

joined or to have the suit dismissed in their absence. Id. at 107.

The Court suggested that in a subsequent suit, the allegedly

indispensable party “should be bound by the previous decision

because, although technically a nonparty, he had purposely

bypassed an adequate opportunity to intervene.” Id. at 114.

The doctrine established in Penn-Central and Provident

Tradesmens Bank has been widely employed by the lower

federal courts.8 In Bolden v. Pennsylvania State Police, 578

8 See, e.g., Safir v. Dole, 718 F.2d 475, 482-83 (D.C. Cir. 1983)

(Scalia, J.) (nonparties are collaterally estopped by litigation of issue

in earlier suit where, despite the court’s invitations, they “sedulously

abstained” from intervening), cert, denied, 467 U.S. 1206 ( 1984);

20

F.2d 912 (3d Cir. 1978), for example, the district court was

confronted by white police officers who engaged in a strategic

ploy almost identical to that employed by petitioners here.

There, the Fraternal Order of Police (“FOP”) participated, but

did not intervene, in an action against the police department

that led to the entry of an affirmative action consent decree.

Four years after entry of the decree, the FOP moved to

intervene for the purpose of seeking to modify the decree. The

Third Circuit denied that request:

“The FOP was seeking on behalf of its members the

best of all possible worlds. Its counsel . . . could supplant,

or at least supplement, the Assistant Attorney General

assigned to the case in negotiating the most favorable

consent decree, while it preserved the option of subse

National Wildlife Fed’n v. Gorsuch, 744 F.2d 963, 967 (3d Cir. 1984)

(where nonparties’ attempted intervention was untimely and their

interests adequately represented, they were precluded from reliti

gating an environmental consent decree); Grann v. City of Madison,

738 F.2d 786, 794-96 (7th Cir.) (failure to intervene in state agency

gender discrimination hearing barred male detectives’ subsequent

attack on the relief accorded), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 918 (1984);

Adams v. Morton, 581 F.2d 1314 (9th Cir. 1978) (failure to intervene

coupled with participation in the original suit is enough to bind a

nonparty), cert, denied, 440 U.S. 958 ( 1979); Cummins Diesel

Michigan, Inc. v. The Falcon, 305 F.2d 721 (7th Cir. 1962) (failure to

intervene in admiralty actions binds a nonparty); Marine Power &

Equip. Co. v. United States, 594 F. Supp. 997, 1003 (D.D.C. 1984)

(“a party that fails to intervene in an action directly challenging its

interests may be barred from bringing a later collateral attack”;

citations omitted); Treasure Salvors, Inc. v. Unidentified Wreck, 459

F. Supp. 507, 514 (S.D. Fla. 1978) (“A party who purposely fails to

intervene is bound under the law of this Circuit”), aff’d on other

grounds sub nom. Florida Dep’t of State v. Treasure Salvors, Inc., 621

F.2d 1340 (5th Cir. 1980), aff’d in part and rev’d in part on other

grounds, 458 U.S. 670 (1982); accord F. James & G. Hazard, Civil

Procedure § 11.31 at 599 (2d ed. 1977) (“The process of settling legal

rights through adjudication is simply another form o f . . . investment,

whose value a bystander with knowledge should not be allowed to

destroy by his silence and inaction”). See also Note, Preclusion of

Absent Disputants to Compel Intervention, 79 Colum. L. Rev. 1551

( 1979).

21

quently mounting collateral attacks upon the same

decree.” Id. at 916.9

The Third Circuit held that the FOP was a de facto party to the

first case and bound by its results. Id. at 918.

Similarly, in Gorsuch, 744 F.2d 963, the district court

dismissed the National Wildlife Federation’s suit against offi

cers of the Environmental Protection Agency and various state

defendants as a collateral attack on a consent decree entered in

a related case in which the Federation had objected to the

decree but had not timely intervened. The Third Circuit

affirmed the dismissal, stating:

“Clearly, plaintiffs were not outsiders unaware of

litigation in progress that would ultimately affect their

interests. In a deliberate choice of litigation strategy, they

chose to stand on the sidelines, wary but not active, deeply

interested, but of their own volition not participants.

Although plaintiffs may not have had their day in court as

litigants, they had the opportunity and for reasons of their

own adopted a different approach. Plaintiffs cannot, at this

stage, assert persuasively that the interest of finality should

not prevail.” Id. at 971-72.

So too here.

D. Rule 19 Does Not Require Parties to a Consent

Decree to Join All Persons Who May Be Affected by

the Decree.

Petitioners and the Solicitor General argue that Rule 19 of

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure required the parties to the

consent decree to join petitioners in the Hispanic Society action.

9 In rejecting the collateral attack, the Third Circuit quoted the

FOP attorney’s statement to a gathering of its members that showed

that the FOP, just like many nonparties, chose not to be a party for

strategic reasons: “I’m not going to let the court let me in—if he wants

me in now in that capacity, I’m not going to let him bring me in. I’m

going to withdraw so that you are not parties to it.” Bolden, 578 F.2d

at 916.

22

See Gov’t Br. at 17-19; Petitioners’ Br. at 54.10 Their position is

that the burden should always rest on the parties to a proposed

decree to join the nonminorities as parties rather than on the

nonminorities to seek to intervene. See Gov’t Br. at 18. We

disagree.

Nothing in Rule 19 requires parties to join everyone who

may be affected by the outcome of litigation. It may not even

be possible to identify all of the nonparties who might be

affected by a decree. For example, a consent decree in a school

desegregation case will undoubtedly affect the lives of thou

sands of school children who are yet unborn. Similarly, a Title

VII consent decree might affect unknown future applicants for

entry level positions or promotions. Rule 19 does not demand

the joinder of all these inchoate interests in the original action.

See Brumfield v. Dodd, 425 F. Supp. 528, 530 (E.D. La. 1976);

American Civil Liberties Union v. Board of Public Works, 357

F. Supp. 877, 884 (D. Md. 1972); cfi Fed. R. Civ. P. 19(c)

(requiring that a pleading state only the names of persons

“known to the pleader” who may be affected by the outcome of

litigation).

Even if all interested nonminorities could be identified,

requiring them to be joined is simply not feasible. Because

there may be hundreds or thousands of potentially interested

nonminorities, they certainly could not all be joined individ

ually. Although in theory a class could be joined, it may not be

possible to find an adequate class representative who is willing

to bear the burden and expense of litigation, particularly if

neither the representative nor class members want to be bound.

This case illustrates the difficulty of joining an involuntary class

as a party. The municipal defendants expressly invited the

Marino petitioners to intervene, yet they deliberately avoided

doing so. They never even argued to the district court, which

10 It is ironic that the Solicitor General would take such a

position. The Department of Justice is a party to many consent

decrees, and we are not aware of any decree in which it joined all

third parties who might be affected by the decree. See pp. 9-10, supra.

23

could have joined them at the settlement hearing, that they

should have been joined. Nor did they press their joinder

argument to the court of appeals. That they do so here offers

vivid evidence of the “sandbag” potential that is inherent in

collateral attacks.

Moreover, petitioners clearly were not necessary parties to

this litigation at the outset. No liability was asserted against

them and they had no legally cognizable expectancy of promo

tion. Cf Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 577 ( 1972)

( for due process guarantees to attach to a benefit, “a person

must clearly have more than an abstract need or desire for it.

He must have more than a unilateral expectation of it. He must

have a legitimate claim of entitlement to it.” ). Even outright

abrogation of the promotional examination would not “as a

practical matter [have] impair[ed] or impedefd]” any legally-

protected interest of petitioners, because they did not pass the

examination. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 19(a)(1).11

Finally, the Solicitor General’s joinder argument is not

logically limited to consent decrees. If nonminorities’ interest in

the race-conscious relief in a proposed consent decree is

sufficient to require them to be joined, they would also have to

be joined in every Title VII action that could lead to a race

conscious order. Indeed, other minorities would have to be

11 In Phillips v. Carborundum Co., 361 F. Supp. 1016

(W.D.N.Y. 1973), the employer defendant moved pursuant to Rule

19 to join local and national unions in an equal pay action brought by

female employees. The district court rejected the employer’s con

tention that the unions were indispensable parties because:

“an order to pay women at an increased rate will not in any way

affect its obligation to the male employees. . . . Perhaps an order

of the court directing the payment of additional wages to certain

women employees will be upsetting to some of the male workers

and precipitate additional collective bargaining problems. Nev

ertheless, these reasons are not sufficient to require an order

pursuant to Rule 19 adding the National Union and the Local

Union as parties.” Id. at 1020 (citation omitted).

24

joined in any case resulting in the hiring of a particular plaintiff,

because they would be as foreclosed as white applicants.

E. Persons Who Had Notice of a Proposed Decree

and the Opportunity to Be Heard Have No Due Process

Right to Bring a Collateral Action.

We are puzzled by the Solicitor General’s argument that

petitioners were caught in a “pincers movement” and were

denied “all possible recourse against consent decrees to which

they object”, thus “depriving them of their rights under the Due

Process Clause”. See Gov’t Br. at 25. The Solicitor General is

wrong. There was no “pincers movement”. There might have

been if petitioners were denied the opportunity to intervene, but

they were not. They deliberately chose not to intervene. As in

Kremer, where the Court considered due process rights under

New York law, the “fact that [petitioner] failed to avail

himself of the full procedures provided by state law does not

constitute a sign of their inadequacy”. 456 U.S. at 485 ( citation

omitted). This was a “pincers movement” with only one

pincer.

Furthermore, this Court has held that the “elementary and

fundamental requirement of due process in any proceeding

which is to be accorded finality is notice, reasonably calculated,

under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the

pendency of the action and to afford them an opportunity to

present their objections.” Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank &

Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306, 314-15 (1950); see also Matthews v.

Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319, 333 (1976) (the “fundamental require

ment of due process is the opportunity to be heard ‘at a

meaningful time and in a meaningful manner’ ”, quoting

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965)).

Petitioners had that here. They were given notice and the

opportunity to present their objections. Notice of the proposed

Hispanic Society consent decree was posted in every police

precinct in New York City more than two months before the

settlement hearing and four months before the consent decree

25

was entered, inviting interested persons to participate in the

settlement hearing. J.A. 84. Petitioners had actual notice and

were heard in opposition to the consent decree. That they could

not appeal the entry of the decree was their own doing because

they chose not to intervene; it is not evidence of a procedural

error.

II. IN ANY EVENT, PETITIONERS’ INTERESTS IN

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY ACTION WERE ADE

QUATELY REPRESENTED BY THE PARTIES WHO

WERE PRESENT.

This Court has long recognized that nominal nonparties to

an action may be bound by its result if their interests are

adequately represented by parties of record. See Hansberry v.

Lee, 311 U.S. 32, 42-43 (1940); Chicago Rock Island & Pac.

Ry. v. Schendel, 270 U.S. 611, 618-19 ( 1926); Heckman v.

United States, 224 U.S. 413, 444-45 (1912); Kerrison v.

Stewart, 93 U.S. 155, 160-63 (1876). The party defendants in

the Hispanic Society action represented the interests of petition

ers sufficiently to bind them to the result.

The lower courts have applied this rule to bar the relitiga

tion of claims and issues that have been settled between parties

with similar incentives to litigate.12 For example, in Telephone

12 See Western Coal Traffic League v. ICC, 735 F.2d 1408, 1411

(D.C. Cir. 1984) (trade association adequately represented power

company’s interest in earlier challenge to ICC rate-setting rules);

United States v. Geophysical Corp., 732 F.2d 693, 697 (9th Cir. 1984)

(a “person technically not a party to the prior action may be bound by

the prior decision if his interests are so similar to a party’s that that

party was his ‘virtual representative’ in the prior action”); Nash

County Bd. of Educ. v. Biltmore Co., 640 F.2d 484, 493-97 (4th Cir.)

(school board’s federal antitrust suit was barred where the state

attorney general represented interests of county school board in state

antitrust proceeding which ended in consent decree), cert, denied, 454

U.S. 878 ( 1981 ); Expert Elec., Inc. v. Levine, 554 F.2d 1227, 1235-36

(2d Cir.) (trade association represented its members in state court

action, thereby precluding them from raising similar claims in federal

court), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 903 (1977); General Foods v. Depart

ment of Public Health, 648 F.2d 784 ( 1st Cir. 1981) (plaintiff who

26

Workers Union, Local 827 v. New Jersey Bell Tel., 584 F.2d 31

(3d Cir. 1978), the Third Circuit held that a union’s participa

tion in a prior affirmative action consent decree precluded a

later action challenging the appointment of a man to a position

previously dominated by women. The Court said, “a labor

organization is an adequate representative of the interests of the

majority of its members; . . . its participation satisfies the due

process requirements of Hansberry v. Lee”. Id. at 33, quoting

Bolden, 578 F.2d at 918.

Similarly, in Bell v. Board of Educ., 683 F.2d 963 (6th Cir.

1982), an individual brought a school desegregation action that

mirrored the complaint in an earlier action brought by the

NAACP in which the defendant school board had prevailed.

The court found that the NAACP’s interests in the prior suit

and the interests of the current plaintiffs were the same, and

that the NAACP had adequately represented those interests.

Id. at 966. The court affirmed the dismissal of the second action

and added:

“We note that were we to apply a contrary principle

rejecting collateral estoppel in school desegregation cases,

we would open up for relitigation all school desegregation

judgments in de facto school cases. A plaintiff who

disagrees with a prior final determination of liability—for

example in Columbus or Dayton—would be entitled to

relitigate the finding of liability. Rights and duties in

desegregation cases previously litigated and established

would never become final. They would always be subject

to collateral attack. Desegregation judgments, like tickets

to the theater, would be good for today’s show only.” Id. at

966.

declined to participate in a lawsuit by two trade associations challeng

ing a state regulation could not subsequently challenge that same

regulation in a later lawsuit); accord Aerojet-General Corp. v. Askew,

511 F.2d 710, 719-20 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 908 (1975);

Southwest Airlines Co. v. Texas Int’l Airlines, 546 F.2d 84, 94-102

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 832 ( 1977).

27

Title VII actions should be no different when nonminor

ities’ interests are adequately represented. Nonminorities

should not be encouraged to splinter their challenges to a

consent decree into innumerable separate actions. Moreover, if

this Court were to hold that the interests of absent non

minorities can be adequately represented by those who partici

pate in the settlement hearing, the difficult problem of persons

with inchoate interests would be resolved; if their interests are

adequately represented, they cannot subsequently challenge the

consent decree.

This is such a case. There were three defendant-

intervenors—the SBA, the SEA and the Schneider Intervenors.

All three groups had interests in the litigation that were more

concrete than petitioners’ interests. The Schneider Intervenors

challenged the proposed decree, and the district court consid

ered those objections. See Hispanic Society, 40 Empl. Prac.

Dec. at 43,655. Petitioners’ interests were well represented, and

even after the Schneider Intervenors decided not to appeal,

petitioners could have intervened at that point. See United

Airlines v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385, 396 ( 1977). They did not.

28

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law as amicus curiae respectfully requests

this Court to affirm the decisions below.

August 22, 1987

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

N orman R edlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

R ichard T. Seymour