Darden v. Wainwright Brief of the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Darden v. Wainwright Brief of the Petitioner, 1985. c211f1f7-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5652d83-ceb5-4f25-819e-462211a991e9/darden-v-wainwright-brief-of-the-petitioner. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

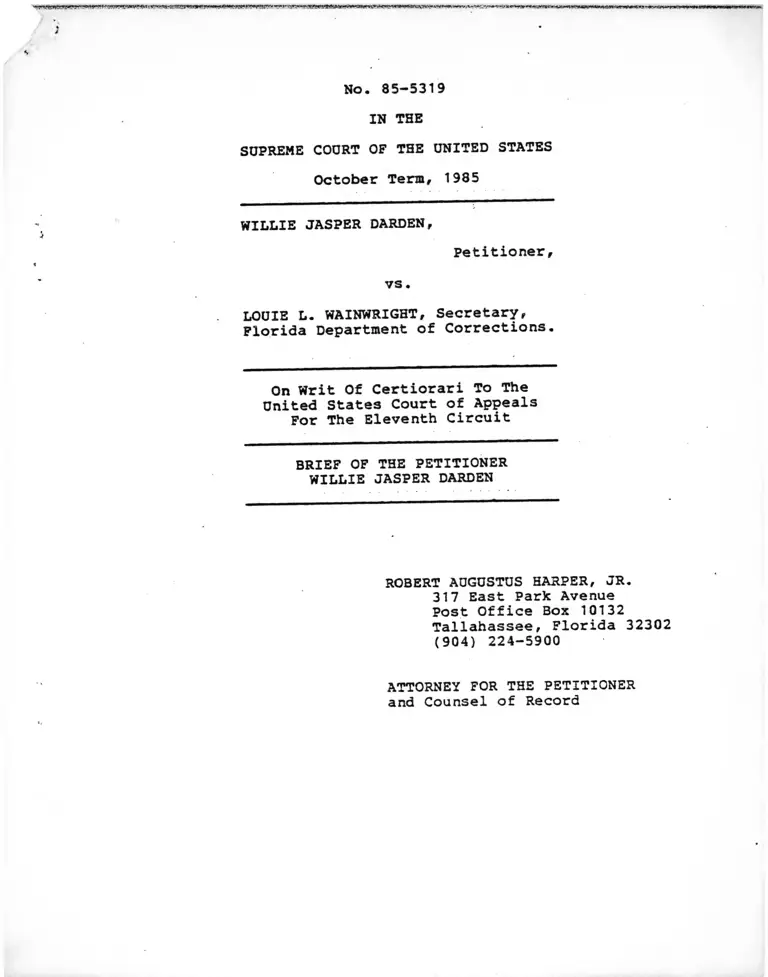

No. 85-5319

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

WILLIE JASPER DARDEN,

Petitioner,

vs.

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary,

Florida Department of Corrections.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court of Appeals

For The Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE PETITIONER

WILLIE JASPER DARDEN

ROBERT AUGUSTUS HARPER, JR.317 East Park Avenue

Post Office Box 10132

Tallahassee, Florida 32302

(904) 224-5900

ATTORNEY FOR THE PETITIONER

and Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1 . Did the prosecution's calculated, unprofessional and inflam

matory closing argument rob the determination of petitioner s guilt

of the fundamental fairness required by due process and deprive the

determination of his sentence of the reliability required by the

eighth amendment?

2. Whether the exclusion for cause of a potential juror solely on

the basis of his scruples against capital punishment can be reconciled

with the decision of the Court in Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. ---,

83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985)?

3. Whether petitioner was denied the effective assistance of counsel

at the sentencing phase of his trial, depriving him of a full, fair,

and individualized determination of whether he should live or die?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

JURISDICTION

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. The Crime and the Evidence at Trial

B. Exclusion of Death-Scrupled Jurors

C. The Interjection of Race at the Voir Dire

D. The Closing Arguments

E. The Performance of Defense

Counsel at Sentencing

II. COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

ARGUMENT

I. [■HE PROSECUTION'S CALCULATED, UNPROFESSIONAL AND CNFLAMMATORY CLOSING ARGUMENT ROBBED THE DETERMINATION

3F PETITIONER'S GUILT OF THE FUNDAMENTAL FAIRNESS

REQUIRED BY DUE PROCESS AND DEPRIVED THE DETERMINATION

DF SENTENCE OF THE RELIABILITY REQUIRED BY THE EIGHTH

AMENDMENT

Mr. Darden Was Denied Fundamental Fairness in tn

Determinations of his Guilt or Innocence

Mr. Darden Was Denied Reliability in the Deter

mination of his Sentence

Althouoh Mr. Darden Is Entitled to Relief under

the Harmless Error Doctrine, He Suffered Actual

and Substantial Prejudice

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PaaeCases t "

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38 (1980)

Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 (1947)

Baldwin v. New York, 399 U.S. 66 (1970)

Barclay v. State, 343 So.2d 1266 (Fla. 1977)

Beck- v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 ( 1980)

Berger v. United States, 295 U.S. 78 (1935)

Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1969)

Brooks v. Kemp, 762 F,2d 1383 (11th Cir. 1985)

Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. ---, 86 L.Ed.2d

231 (1985)

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992 (1983)

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1976)

Coleman v. State, 215 So.2d 96 (Fla. 4th DCA 1968)

Cooper v.

cert.

State, 336 So.2d 1133 (Fla. 1976),

denied, 431 U.S. 925 (1977)

Darden v. State, 218 So.2d 485 (Fla. 2d DCA 1969)

Darden v. State, 329 So.2d 287 (Fla. 1976)

Darden v. Wainwright, 513 F. Supp. 947 (M.D. Fla. 1981)

Darden v. Wainwright, 699 F.2d 1031 (11th Cir. 1983)

Darden v. Wainwright, 725 F.2d 1516 (11th Cir. 1984)

Darden v. Wainwright, 767 F.2d 752 (11th Cir. 1985)

Darden v. Wainwright, No. 79-566 Civ. T-H (M.D. Fla.

April 15, 1981)

Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122 (1976)

Donnelly v. De Christoforo, 416 U.S. 637 (1974)

Drake v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1449 (11th Cir. 1985)

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 D.S. 145 (1968)

Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982)

Estelle v. Williams, 425 U.S. 501 (1976)

Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532 (1965)

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349 (1978)

Gibson v. State, 351 So.2d 948 (Fla. 1977)

Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (1979)

Harris v. State, 414 So.2d 557 (Fla. 3d DCA 1982)

Johnson v. Louisiana, 406 U.S. 356 (1972)

Kampshoff v. Smith, 698 F.2d 581 (2d Cir. 1983)

Kyle v. United States, 297 F.2d 507 (2d Cir. 1961)

Lisenba v. California, 314 U.S. 219 (1941)

Lockett v . Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978)

People v. Savvides, 1 N.Y. 2d 554, 154 N.Y.S.2d

885, 136 N.E.2d 853 (1956)

Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976)

Roundtree v. State, 229 So.2d 281 (1st DCA 1969),

app. dismissed, 242 So.2d 136 (Fla. 1970)

Smith v. Wainwright, 741 F.2d 1248 (11th Cir. 1984)

Songer v. State, 322 So.2d 481 (Fla. 1975)

Stanley v. Zant, 697 F.2d 955 (11th Cir. 1983)

Stone v. Powell, 428U.S. 465 (1976)

Strickland v. Washington, ___ U.S. 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984)

Taylor v. Kentucky, 436 U.S. 478 (1978)

Tucker v. Kemp, 762 F.2d 1480 (11th Cir. 1985)

United States v. Ash, 413 U.S. 300 (1973)

United States v. Cronic, ____ U.S. ____, 80 L.

657 (1984)

United States v. Young, 470 U.S. ____, 84 L.Ed.2d

1 (1985)

United States ex rel. Williams v. Twomey, 510 F.2d

634 (7th Cir. 1974)

Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. ___, 83 L.Ed.2d 841

(1985)

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S.

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S

Zant v. Stephens, ____ U.S. ____,

510 (1968)

. 280 (1976)

77 L.Ed.2d 235 (1983)

Statutes:

Fla. Stat. § 921.141(2)(a)(b)(c)

S 921.141(3)

1979 Fla. Laws ch. 79-353

28 U.S.C. 5 1 254( 1 )

§ 2241

Other Authorities

ABA Code of Professional Responsibility

Preamble and Preliminary Statement

EC 7-24

EC 7-25 DR 7-106(0

ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct (1983)

Rule 3.4(e)

A3A Standards for Criminal Justice (2d ed. 1980)

§ 3-5.8(c)

S 4-7.8

Annotation, 88 A.L.R.3d 449 (1978)

Barkowitz and Brigham, Recognition of Faces;— OwnRace Bias, Incentive, and Time Delay, 12 Journal

of. Applied Social Psychology, 4:255 ( 1982)

Brigham and Maass, Accuracy of Eyewitness'identifications in a Field Setting, 42 Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology 673 (1982)

Consideration of Mitigating circumstances, 69 Cal. L.

Rev. 317 (iyaiF

Y. Kamisar, W. LaFave & J. Israel, MODERN CRIMINAL

PROCEDURE (5th ed. 1980)

Note, Did Your Eves Deceive You? Expert Psychological

^ J S s S S n S y - j the Unreliability 5t B Y ~ i*b5 PIdentification, 29 Stan. L. Rev. 969 (1977)

Vance, The Death Penalty After Furman, 48 Notre Dame

Lawyer 850 (1973)

Vess, Walking a Tiahtropet A Survey o£ £the Prosecutor's Closing Argument, 64 J. Cnm. L. &

C. 22 (19?3l

PSYCHOLOGY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY (1970).Yarmey, THE

No. 85-5319

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

WILLIE JASPER DARDEN,

Petitioner,

vs.

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court of Appeals

For The Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF OF THE PETITIONER

WILLIE JASPER DARDEN

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida on direct appeal

is reported as Darden v. State, 329 So.2d 287 (Fla. 1976). The

opinion of the federal district court denying habeas corpus

relief is reported as Darden v. Wainwright, 513 F.Supp. 947

(M.D.Fla. 1981). The decisions of the court of appeals are

reported as Darden v. Wainwright, 699 F. 2d 1031 (11th Cir. 1 983)

(panel opinion), on rehearing, 708 F. 2d 646 ( 1 1th Cir. 1983) (en

banc court affirming by egually divided vote), on rehearing, 725

F. 2d 1 526 ( 1 1 th Cir. 1984) (en banc court reversing and granting

the writ). The opinion of the court of appeals on remand from

this court is reported as Darden v. Wainwright, 767 F. 2d 752

(flW W srvi K*r5»> '>rrv»r

(11th Cir. 1 985) (en banc court affirming denial of writ by the

district court).

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§§ 1254(1) and 2241.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the sixth amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, which provides in relevant part: "In all

criminal proceedings, the accused shall enjoy the right ... to

have the assistance of counsel for his defense"; the eighth

amendment, which provides: "Excessive bail shall not be required,

nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments

inflicted"; and the fourteenth amendment, which provides in

relevant part: "(N]or shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law...."

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

A. The Crime and the Evidence at Trial

Carl's Furniture Store in Lakeland, Florida, was held up

early in the evening of September 3, 1973. One of its owners,

Carl Turman, was shot and killed as he entered through a back

door. Phillip Arnold, a sixteen-year-old who lived nearby, was

shot and wounded as he sought to give aid to Mr. Turman. The

gunman also attempted a sexual assault on Mrs. Turman.

Just a few moments after these events, Willie Jasper Darden,

a black man, lost control of his car and struck a telephone pole

2

■w w n w r

a little over three miles from the furniture store. At the time*

he was on weekend furlough from a Florida prison and was return

ing to his girlfriend's house in Tampa. A few hours later, Mr.

Darden was arrested at the home of his girlfriend for leaving the

scene of an accident. Later the same night, he was charged with

the murder of Mr. Turman, the attempted murder of Mr. Arnold, and

the robbery that accompanied these shootings. R. 586.

The state's case rested primarily on identifications of

their black assailant by the white victims, Mrs. Turman and Mr.

Arnold, and limited forensic evidence. The latter consisted of

testimony by a deputy sheriff that, a day and one-half after the

crime, he found a .38 caliber pistol in^a ditch under four inches

of water thirty-nine feet from the highway and about an equal

distance from the place of petitioner's automobile accident. R.

503-04, 511. It was shown at trial that the pistol was the same

caliber as the murder weapon and that four bullets had been fired

from it in a sequence that matched the shooting during the crime.

The prosecution was unable to connect the pistol to the crime by

ballistic or other forensic evidence. R. 357-58, 514, 517-22.

Mr. Darden testified at length. R. 571-659. He told how

his automobile had skidded from the highway in wet weather as he

hastened back to Tampa from Lakeland to meet his girlfriend and

Citations to the transcript of the trial record are designated as

r . . Citations to the record on appeal to the Florida

Supreme Court are designated as A.R. ____. Citations to the

hearing before the federal magistrate on habeas corpus are

designated as H.C. ____.

3

attend a wedding later on that evening. R. 574-76. He explained

that, with the aid of a passing motorist, he had sought unsucces

sfully to locate a wrecker to take the disabled auto in tow.

Failing in this effort, he had obtained a ride to Tampa.* This

was corroborated by the state's witnesses, who also noted Mr.

Darden's calm and poise during this episode. R. 577-579, 330-31,

334-35, 340-41 . Mr. Darden denied that he had been at the

furniture store or had had anything to do with the crimes with

which he was charged. R. 592-93, 598-99.

Mr. Darden's testimony concerning the events of the evening

of September 8, 1973, was both plausible and partially corrobora

ted by the state's evidence. Apart from the identification

testimony of Mrs. Turman and Mr. Arnold, it was not in direct

conflict with the state's evidence. Thus, to a large degree, the

state's case rested on the "jury's determination of the credibi

lity of Darden's alibi testimony as against the eye-witness

testimony of the victims." Darden v. Wainwright, No. 79-566 Civ.

f Slip op. at 22 (M.D. Fla. April 15, 1981) (Magistrate s

Recommendation and Report).

This eyewitness testimony was not without substantial

problems. Immediately after the offense, Mrs. Turman told

officers that she could not remember what the subject looked like

or what he was wearing. This was, she explained, because she was

scared to look while the crime was in progress, and at one point,

covered her face with her hands so she would not have to see. R.

4

240, 280. See also R. 232, 236. She later described the man as

the same height as herself, 5'6", R. 238 , heavy-set, very

clean-shaven, black, approximately 200 pounds, with a fat face.

R. 237, 239 . At trial, she was sure the shirt was a pullover,

with a stripe around the neck and waist. R. 226-27. Mr. Arnold

confirmed part of her identification, remembering a heavy set man

wearing a knit shirt of dull, light color with a ring around the

neck, R. 443, and that the assailant was clean shaven. R. 476,

2498 . But he testified that the gunman was almost his height,

about 6 feet two inches tall. R. 496-97.-

In contrast to these descriptions, petitioner was five feet,

ten or eleven inches tall and weighed approximately 170 to 175

pounds. R. 596. Moreover, one of the state’s witnesses a

.motorist who had stopped at the scene of the auto accident that,

according to the prosecution's theory, occurred when petitioner

was fleeing the scene of the crime —— testified that petitioner

was wearing a white shirt that buttoned down the front and that

he had a gray moustache. R. 311, 313, 318-20.

The substantial discrepancies between Mr. Darden's actual

apoearance and Mrs. Turman's and Mr. Arnold's descriptions of

their assailant are not surprising in light of the conditions

that surrounded their initial identifications of Mr. Darden.

Three days after the incident, two sheriff's deputies visited Mr.

^ In fact,in excluding one of the photographs in the photo

show-up, described below, Mr. Arnold eliminated one photo because

the person had a moustache. R. 464.

5

Arnold in the hospital, where he was recovering from his ballet

wounds. R. 446 , 460-61 . According to Mr. Arnold's testimony,

elicited out of the presence of the jury, he had by this time

already read newspaper stories about the crime, R. 457-58, and he

probably knew of the arrest of a suspect. R. 462.

The deputies, Mr. Arnold recalled, had shown him six

photographs and asked whether he could identify his assailant

from among them. R. 446, 459-60. He immediately rejected four

out of hand; "they didn’t look anything-at all like him." R. 449,

461-64. He then wrote on a piece of paper the following informa

tion:

"Both of these two look a little like him!

DID HE HAVE A MUSTACHE?

"I don't think so!"WHAT TYPE SHIRT WAS HE WEARING?"It was short sleeve. It was something like

a red or orange and I think it was a a knit

material, pale."

R. 455, 475. Mr. Arnold then picked out of the two remaining

photographs the one that looked "a little like him." This

picture bore the name "Darden" and the date of arrest, "9-9-73."

The circumstances surrounding Mrs. Turman's identification

were as follows. The day following her husband's funeral, she

was asked by the prosecutor to attend Mr. Darden's preliminary

hearing. She was taken to a tiny courtroom with one black male

sitting at defense table and no other blacks in the room. R.

221—22. The prosecutor walked over to Mr. Darden, pointed at

him, and asked: "Is this the man that did it?" A.R. 50. She

6

said yes. Id. Asked by the court whether she was sure that the

man at the defense table was the assailant, she replied that

"even with his back to me while I sat [at the rear of the

courtroom] I reached over and touched my sister's hand and said,

'That's him.'" A.R. 53.

The only physical characteristic which every witness who saw

both men could agree on was race: they were both . "colored." The

testimony of Officer Neill, who arrested Mr. Darden in Tampa, is

particularly telling. Neill was asked if the man he arrested,

Mr. Darden, fit the physical description given by Mrs. Turman.

Neill replied: "Yes. The dark-colored automobile, the time

element, the car crash ... just lead me to believe this possibly

—was him." Pretrial hearing of 1/9/73 at 82. This "physical

desription" would have fit almost any black man near the scene of

the crime that day. Indeed, the reliance on race as substantiat

ing the identifications was something the prosecutor would return

to in his summation.

B. Exclusion of Death-Scrupled Jurors

At voir dire, several jurors with scruples against the death

penalty were excluded for cause upon the motion of the prosecu

tor. One of those excluded was potential juror Murphy. He was

excluded solely upon the following question and answer:

THE COURT: Do you have any moral or reli

gious, conscientious moral or religious

principles in opposition to the death penalty

so strong that you would be unable without

violating your own principles to vote to

recommend a death penalty regardless of the

facts?

7

MR. MURPHY: Yes, I have.

R. 165. This was the only question asked Mr. Murphy.

C. The Interjection of Race at the Voir Dire

During the voir dire, the prosecutor addressed the potential

jurors as follows:

The testimony is going to show I think very

shortly when the trial starts the victims in

this case were white and, of course, Mr.

Darden, the defendant, is black. Can each of

you tell me that you can try Mr. Darden as if

he was white? Can you look at this defendant

and assure me that you can try him as if he is

white? Because the victims will be white.

Can you look at the defendant and even though

he is black, can you try him as. if he was

white?

R. 57, 115 (emphasis added).

Apart from the effect of reenforcing for the jury the

different racial status of the defendant and the victims, the

question presupposes disparate treatment for blacks and suggests

that it requires a particular effort to treat a black defendant

within the same standards of due process and impartiality due a

white person. Even this would not be so disturbing had the

prosecutor stopped there. But, as we shall see, his closing

argument served forcefully to underline the negative implications

of this voir dire questioning.

D. The Closing Arguments

Petitioner's counsel opened and closed the arguments prior

to deliberation on guilt or innocence. Mr. Maloney, the less

8

experienced of the two, began. He conceded that the perpetrator

of the murder and assaults was "a vicious animal." R. 717. He

also expressed his personal opinion regarding the strength of the

circumstantial evidence regarding the pistol: "It's not good

enough for me. I wouldn't do what you're being asked to do on

that, really I wouldn't___" R. 734. Finally, he expressed his

personal opinion regarding the state's failure to prove guilt

beyond a reasonable doubt, R. 736, and concluded: "The question

is, do they have enough evidence to kill that man, enough

evidence? And X honestly do not think think they do. R.

737-38.

Apart from these isolated errors committed by a fledgling

lawyer, the defense summation was unexceptionable. Mr. Maloney

recounted the state's evidence, stressed the virtual absence of

£rjy forensic evidence tying to the crime either Mr. Darden, his

car, or even the weapon found a day and one—half later near the

site of the wreck. He stressed the lack of any evidence tying

4

the gun, despite its unique marking and non-standard characte-

5 .ristics to Mr. Darden. Finally, he noted the discrepancies

between the descriptions of the assailant given by Mrs. Turman

and Mr. Arnold, on one hand, and that given by the passer-by who

3

3 At the time, Mr. Maloney had been licensed as an attorney for

only four months.

4 The gun was marked "United States Property, Massachusetts,

December 29, .38 special BRD." R. 809.

3 The gun had been rebored. See R. 778.

9

assisted Mr. Darden after the wreck: The victims agreed that

their assailant was clean-shaven and wore a dark or dull—colored

pullover with a band or ring at the neck; the passer-by described

Mr. Darden as having a moustache and wearing a white shirt with

buttons down the front.

The prosecution's argument was split between Mr. White and

Mr. McDaniel. Mr. White argued first, marshalling the state's

evidence, enumerating the elements of the offenses, and discuss

ing the reliability of the identifications. R. 738-747. He

concluded:

I am convinced, as convinced as I know I

am standing before you today, that Willie

Jasper Darden is a murderer, that he murdered

Mr. Turman, that he robbed Mrs. Turman and

that he shot to kill Phillip Arnold. I will

be convinced of that the rest of my life.

R. 748.

At that point, the senior prosecutor, Mr. McDaniel, rose to

complete the summation. It is only possible to understand the

nature and effect of that argument by viewing it as a whole,

rather than a disaggregated series of individually improper

comments. Following on the heels of trial and arguments focusing

on the reliability of the eyewitness identifications in the light

of the weakness of the balance of the prosecution's case,

McDaniel's argument was carefully crafted to make up for any

deficiencies in the state's proof by distracting the jury from

10

the evidence. From start to finish, McDaniel interjected and

emphasized the emotional, the irrelevant, and the impermissible.

First, he disclaimed emotional involvement in the case. R.

749.- Then he took credit for the tactical choice of defense

counsel in focusing on the failures of the Polk County Sheriff in

investigating the case: "he has notes I gave him many years ago."

Id. Having thus established his authority and credibility, he

launched on his first theme:

But let me tell you something. As far as

I am concerned, there should be another

defendant in this courtroom, one more, and

that is the division of corrections, the

prisons. As far as I am concerned... this

animal was on the public for one reason.

Because the division of corrections turned him

loose, lets him out, lets him out on the

public. Can we expect him to stay in a prison

when they go there? Can't we expect them to

stay locked up once they go there? Do we know

that they're going to be out on the public

with guns, drinking?

* * *

He shouldn't be out of his cell unless he has

a leash on him and a prison guard at the other

end of that leash....

No, I wish that person or persons responsible

for him being on the public was in the doorway

instead of Mr. Turner. I pray that the person

responsible for it would have been in that

doorway and any other person responsible for

it, I wish that he had been the one shot in

the mouth. I wish that he had been the one

shot in the neck, instead of the boy [Phillip

Arnold].

Yes, there is another Defendant, but I

regret that I know of no charges to place upon

him, except the public condemnation of them,

condemn them. Turn them loose to visit his

family ... that turns out his family is a girl

friend in Tampa, ... his sponsor.

R. 749-51.

Having sounded his theme — "Mr. Turman is dead because that

unknown defendant we don't have in the courtroom allowed it. He

is criminally negligent for allowing it." R. 752 McDaniel

turned to his main point.

The Court will tell you at the . end of the

argument in the -jury instructions at this

point, you are merely to determine his

innocence or guilt, nothing else whether he is

guilty or innocent. And after you return that verdict of guilty of first degree murder ...

then you will be asked at that time to go back

and retire and advise the Court whether or not

he gets the death sentence or whether he

should get life.

That is an advisory opinion on your part,

and it has nothing to do with this trial, and

Mr. Maloney knows that. But ... I will

guarantee you I will ask for the death. There

is no question about it.

The second part of the trial I will

request that you impose the death penalty. I

will ask you to advise the Court to give him

death. That’s the only way that I know that

he is not going to get out on the public. It's

the only way I know. It's the only way I can be sure of it. It's the only way that anybody

can be sure of it now, because the people that

turned him loose — this man served his time

and if this man served his time as the Court

has sentenced him, that's fine. If he's

rehabilitated, fine. But let him go home on

furloughs, weekend passes — not home, strike

that, excuse me -- go over with his girl

friend for the weekend, go shoot pool for the

weekend, go sell his guns, or gun, for the

weekend, go consume drink in the bars over the

weekend.

12

R. 7 5 2 - 5 4 .

McDaniel then sounded his second theme:

Mr. Maloney said, well, sure he had an

accident, ... but do you think he would admit

that accident if he- wouldn't have had that

fancy fingerprint [ ] to prove it? No, he

wouldn't have admitted nothing.

I don't know, he [Darden] said on final

argument I wouldn't lie, as God is my witness,

as God is my witness, I wouldn't lie. Well

let me tell you something: If I am ever over

in that chair over there, facing life or

death, life imprisonment or death, I guarantee

you I will lie until my teeth fall out.

R. 754.

McDaniel turned briefly

witness testimony. R. 756-57.

the crime, R. 757, which he

observations:

to the reliability of the eye-

He then focused on the events of

punctuated with the following

I wish [Mr. Turman] had had a shotgun in his

hand when he walked in the back door and blown

his face off. I wish that I could see him

[Darden] sitting here with no face, blown away

by a shotgun, but he didn't.... I wish

someone had walked in the back door and blown

his head off at that point. But he is lucky,

the public unlucky, people are unlucky, it

didn't happen.

R. 758-59.

But he [Darden] heard every word everybody

said, and I assure you, if we hadn't been able

to prove the accident, they would never have

admitted it.

® There was no fingerprint evidence introduced in this case,

whatsoever.

13

R. 7 6 4 .

There is one person on trial, not the

Polk County Sheriff’s Office, not the Hills

borough Sheriff's Office, but he and his

fcegpers, the Division of Corrections.

R. 764-65.

But sometimes, it emotionally gets to me. For

four days I saw that man sitting there ——

calm, cool, calculating, smiling at the right

time, until it came up time for his parole was

in question, and then he goes to the stand

with his handkerchief in his hand....

I don't cry for him ...

R. 765.

He's even got a driver's license. Why in

the world does — what in the world is a State

prisoner doing with driver's license? I

wonder if the public is paying for it.

R. 766.

Lie detector test. That's the red herring

they would like to throw in. I don't believe

anything he says....

R. 769-70.

McDaniel returned to the evidence, discussing the accident

and eyewitness testimony again. R. 770—75. He then discussed

the gun and the shooting, noting that four shots were fired. R.

7 7 3 -7 5 . "And Mr. Darden saved one. Again, I wish he had used it

on himself." R. 775. Of the accident: "I wish he had been killed

in the accident, but he wasn't. Again, we are unlucky that time.

Id.

McDaniel's peroration did not let up.

14

He stopped at one service station, he says, to

get a wrecker in Plant City. That’s what he

says, I don’t know that he stopped at any.

What was he going to do with the wrecker when

he got it? I guarantee you he was not going

back to the scene of the accident until he had

gotten home.

R. 777-78.

[D] on't forget what he has done according to

those witnesses, to make every attempt to

change his appearance from September the 8th,

1973. The hair, the goatee, even the mous

tache and the weight. The only thing he

hasn't done that I know of is cut his throat.

R. 779.

And then he closed:

I'm going to ask you, in closing, that

you consider the direct evidence, and as Mr.

Maloney said, its good evidence, the best

evidence, the direct evidence, the eyewitness

considered as circumstantial evidence,

surrounding that wreck, the time, the place,

his color, clothes, the gun, where he went,

leaving the scene of an accident and don't

turn this man loose. I cannot help but wish

that the Division of Corrections was sitting

in the chair with him. Thank you.

R. 780-81.

There were two objections during the course of McDaniel's

summation. The first occurred immediately after McDaniel

referred to the defendant as "a criminal" and alleged that he

had carried a gun when he returned home on furlough. R. 751.

This was objected to as not based on the evidence. The judge

merely deflected the issue, reminding the jury that they "are the

judges of the evidence." Id.

15

«■>*

The second occurred later in the argument, "that's about the

fifth time that he has commented he wished someone would shoot

this man or that he would kill himself." R. 779. This degener

ated into an exchange between Mr. Maloney and Mr. McDaniel about

which side had less evidence. R. 779-80. The court's response

was to overrule the objection and order counsel to proceed. R.

780.

The judge's instructions to the jury prior to the summations

tended to make matters worse. He told the jurors that:

I am sure that none of the attorneys would

intentionally misquote any evidence or mislead

you in any way. They are all respected

attorneys back in Polk County; they are all

oersonal friends, I think, of mine; and I know

each of them well. . ..[T]hey are permitted to

argue the law to you. They are certainly permitted to argue the facts to you; so both

will be involved. But they are not binding

upon you.

Now, let me tell you what they are. They

are a big help to you, or can be, These ^te

men who are trained in the law or trained in

trials, and their analysis of the testimony,

their analysis of the issues, their comments

upon the pertinence and the weight of the

particular items of testimony can be extremely

helpful to you....

Faced with this, Mr. Darden’s senior counsel, Mr. Goodwill,

did the best he could to respond. Referring to White's and

McDaniel's improper arguments, he noted particularly and "more

importantly, the way they were said, the manner in which they

were expressed...," R. 782, "the yelling and screaming and

16

r rrtEr r ar*

righteous indignation and get up and blow your face off," R. 801;

"the yelling and screaming and the pushing and the shoving and

the hitting with the stick, and the whole works." R. 802. And

he admonished the jury: "He tries to win you or embarass you into

a decision based on his argument, but not based on what came from

that stand...." Id. See also R. 786, 787, 791, 794, and 804.

Instead, he discussed the evidence and testimony at great length,

R. 782-820, concluding: "You can’t prove him guilty on what Mr.

McDaniel says, and by the same token, you can't find him innocent

on what I say." R. 818.

2 . The Performance of Defense Counsel at Sentencing

The senior of the two assistant public defenders to repre

sent petitioner, Raymond A. Goodwill, Esq., served as a public

defender only part-time, two days per week. H.C. 273. Although he

had tried three or four capital cases, H.C. 278-79, he had no

experience in preparing a case for the separate, post-verdict

sentencing trial provided by Florida's 1972 death sentencing

statute. Co-counsel, Maloney, was just recently licensed to

practice. See H.C. 132, 143. Ironically, the responsibilities of

lead counsel fell largely upon him.

Counsel's preparation for the sentencing hearing consisted

solely of "twenty or twenty-five minutes" of talking with the

victim's widow during a "thirty or forty minute recess" between

the announcement of the guilt verdict and the commencement of the

sentencing proceeding. H.C. 373. Counsel waived opening argument

to the jury, R. 893, offered no evidence, R. 892, and made only a

17

-rrr*«&v r s rw

brief, three or four-minute summation. R. 895-97. Maloney, the

less experienced counsel did the summation; he began by telling

the jury that he was "sure that you will find that Mr. Darden

falls into just about every one of the aggravating circum

stances___ " R. 895 (emphasis added).

Once counsel had completed this "presentation," the court,

in the presence of the jury, invited Mr. Darden to speak.

Speaking from counsel table, Mr. Darden said:

Ladies and gentlemen of the Jury, I was

on the stand yesterday for some period of time

giving my testimony[,] the best of my know

ledge of what happened on that Saturday. I

stand firm before you again today after being

convicted, that what I told you on that stand

was the truth. You have found an innocent man

guilty of murder, something I has no knowledge

about. You not only damaged me, you damaged

my family, seven kids and a wife. That's all,

Your Honor.

^ 3 9 7_9 8> The jury returned a recommendation of death, but only

by a divided vote. See Darden v. Wainwright, 699 F.2d 1031, 1041

(11th Cir. 1983) (Clark, C.J., dissenting). The trial court

imposed the death sentence, finding only two mitigating circum

stances: that petitioner "is the father of seven children" and

that he "repeatedly professed his complete innocence of the

charge." A. R. 208.

Defense counsel knew at trial of information relevant to Mr.

Darden's character and background. H.C. 885. For example,

counsel received psychiatric and psychological evaluations

18

r.7*?jc r ^ r «* w w »w w w ►rjHrfST' ww<

containing mitigating material. The psychiatric report stated

that petitioner

could be called a [Schizoid-] personality, a

man who has been socio- and economically

deprived throughout his life. He had never

known as a child, any mothering, as his Mother

died at an early age and he was cared for by

whatever relatives were available.

A .r . 27. A second psychiatric report contained a fuller treat

ment of the circumstances of Mr. Darden's life from childhood.

It indicated that he ran several businesses successfully, was

well liked in the community, and was considered non-violent by

his acquaintances. His intellectual functioning was evaluated as

dull normal, with an I.Q. of 88. Report to Judge Dewell from H.

Goldsmith, Ph.D. (January 14, 1974); see A.R. 151. In addition,

petitioner's girlfriend would have testified that he was good,

kind, and non-violent to her and others. ^

Preparation by counsel would have yielded more. Mr. Darden

was born in Greene County, North Carolina in 1933. His mother,

the daughter of tenant farmers, was fifteen-years-old. His father

was an auto mechanic with a third grade education. His mother

died in childbirth, two years later, along with his infant

brother. Both of his parents, like most black residents of that

jjoj were but two generations removed from slavery.

The i nf ormat ion that follows is contained in the record of

oetitioner's second habeas corpus proceeding, which is or will be

before the Court on a petition for a writ of certiorari and a

motion to consolidate.

19

Greene County is in an impoverished rural area of Eastern

North Carolina with a 50% black population. It is primarily an

agricultural community; tobacco is the basis of the local

economy. When Mr. Darden was born, the local tobacco farmers

still depended exclusively on the labor of their black tenants.

These blacks were free only of the legal status of slavery; their

lives were entirely dependent on the marginal existence available

through seasonal labor in the tobacco fields. More than 70% of

the farms in the county were worked by black tenants (affidavit

' of William C. Harris) yet by the 1930's, blacks owned only 4% of

the taxable wealth in the state. The average black family earned

less than $1,000 annually^ The schools available to blacks held

classes only during those brief respites from the seasonal

tobacco industry. The high-school graduation rate for blacks

during that period was four times less than that for whites. The

average formal education for black adults in rural areas like

Greene County was 2 1/2 years. The infant mortality rate in

Wilson, North Carolina, the closest city to the rural area in

which Mr. Darden was raised, was 136 per 1,000, fourth highest of

any city in the United States. The rate among the black popula

tion was twice that of the white population.

As recounted by historian William C. Harris, the black

residents of Greene County were "commonly referred too as

'niggers'. When they were brought to court, they usually found

themselves at the mercy of a hostile or indifferent white judge

and jury ... black offenders were more severely penalized than

20

the crimes warranted___ Most of their crimes were minor theft,

frequently committed in order to survive." Mr. Darden's earlier

experience with the criminal justice system consisted of a series

of economic crimes committed in an attempt to Support himself and

his family in an environment totally lacking in economic opportu

nity for the average black. One early episode resulted in a four

year prison sentence for forging a check for forty—eight dollars

in order to buy food for his pregnant wife and himself.

Life in Greene County was an ordeal for blacks from which

few escaped unscathed. "Willie, along with his contemporaries

born in the 1 930's, faced a life of marginal existence in which

there was little w.ork for much of the year, no hope that he could

improve his social standing, and almost non-existent opportunity

to acquire a high school education and advance into a career.

(Harris affidavit).

Mr. Darden's early life was spent in several different

homes. After his mother died when he was two, he was sent to

live with his maternal grandparents. He returned home when his

father remarried in 1 938 , but he was sent to a foster home when

his stepmother abandoned the family. These tenant farmers

orevented him from attending school, made him perform excessive

farm chores, and failed to provide him clothing. He eventually

stole in order to dress properly.

After several months with the foster family, Willie Darden

was involved in several episodes of petty theivery. He was

eventually caught attempting to pilfer a mailbox, for which he

21

was sent to the National School for Boys at the age of sixteen.

Once there, he adamantly refused to return to this foster family.

The authorities at the School for BOys described him at the

time as a simple, well-intentioned and cooperative youth who

seemed inordinately obsessed with his father and extremely

concerned that he had not heard from him since he was abandoned

to the foster home. An evaluation conducted at the time states

that Willie was very "anxious to reestablish the relationship ...

between himself and his father," and that he constantly "des

cribes his father in glowing terms and actually embroidered on

fact when giving his history in order to present the father in

the most favorable light." It is clear that the unexplained

abandonment by his father crushed Willie emotionally and was a

radical turning point in his transition from adolescence to

adulthood.

Those who knew Willie Darden describe him as a kind, wise,

and non—violent man, and express a unanimous disbelief that he

could be capable of committing the crime with which he was

charged. His former wife recalls him as a good man who never

argued or fought with anyone. His son remembers their loving

relationship and describes him as "the most amazing and inspira

tional man I have ever met."

Counsel were aware of none of this. The reason is clear:

They believed they "were fairly limited statutorily by what

things were in the statutes as far as mitigation." H.C. 372. As

Maloney testified:

22

... after a perusal of the mitigating

circumstances in the Florida Statute

9 21.141 [/] ... we reached the conclusionthat Mr. Darden did not qualify for any

of the mitigating circumstances.

We were operating on the premise at

that time that we were limited to those mitigating circumstances. At least I was

completely unaware that any mitigating circumstance/ if relevant/ is admissible.

Something should have been offered

in mitigation. In any capital case such

as this, something can be offered m

mitigation...

q . Would it be fair to say that you and

co—counsel were using 921.141 —— I

believe it's subsection B, Mitigating

Circumstances — as being a closed shop?

That that.was all you could consider in

the way of mitigating circumstances and

nothing outside the four corners of the

statute?

A. Until the Supreme Court ruled in Gardner

v. Florida, that was my opinion. _ And Gardner v.'"Florida considerably postdated

this trial.

Q. Okay. But that was what you were all

thinking on the day —

A. Yes, sir.

Q. — on January 19th, 1974.

A. Yes. sir.

* * * *

A. We certainly went through the mitigating circumstances in 921.141, and I believe

we came to the conclusion that there were

no mitigating circumstances and no

evidence was presented.

23

w ' r r ^ w w w w w i ' w?x *w *tv • B W 'w w w b *1

H.C. 154-55; see also H.C. 245-46. Maloney later learned he was

wrong: "Lockett is the first time that I found out from the

United States Supreme Court that mitigating circumstances were

not limited to the enumerated mitigating circumstances." H.C.

278.

II. COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS

The history of this case is tortuous. On direct appeal, the

Florida Supreme Court treated the prosecutorial argument issue on

the merits. It conceded the argument was improper but neverth

eless affirmed because "[t]he law requires a new trial only in

those cases in which it is reasonably evident that the remarks

might have influenced the jury to reach a more severe verdict of

g u i l t__or in which the comment is unfair." Darden v. State,

329 So.2d 287, 289 (Fla. 1976). It found no unfairness here for

three reasons: (1) in light of the defense argument, the

statements of prosecuting counsel ...do not seem unduly inflamma

tory...," 329 So.2d at 290; (2) in light of the "heinous set of

crimes..." the arguments were "fair comment ... reasonably

describing what happened and what should be done to the guilty

party...," id. at 290-91 ; and (3) in light of "overwhelming

eyewitness and circumstantial evidence" and "absolutely no

mitigating circumstances," the remarks, "were not sufficient to

^ The court of appeals concluded that the "suggestion the Florida

Supreme Court did not dispose of the issue on the merits is

untenable." Darden, 699 F.2d at 1 034, a f f1 g, 513 F. Supp. at

951-52.

24

deprive Appellant of a fair trial...." Id_. at 291. Two justices

dissented.

In his brief before the Florida Supreme Court (pp. 28-35),

Mr. Darden challenged the exclusion for cause of venireman

Murphy. The argument was rejected by that court without discus

sion. Id. at 289.

This Court granted certiorari, heard argument, and dismissed

the writ as improvidently granted. Darden v. Florida, cert.

granted, 429 U.S. 917 (1976), cert, dismissed, 430 O.S. 704

(1977). On federal habeas corpus, the Magistrate recommended

that the writ be granted on the grounds of prosecutorial miscon

duct. The Magistrate also recommended that relief be granted due

to the unconstitutional exclusion for cause of venireman Murphy.

The district court disagreed on both issues and denied relief.

Darden v. Wainwright, 513 F.Supp. 947 (M.D. Fla. 1981). A panel

of the Eleventh Circuit affirmed, one judge dissenting. Darden,

699 F.2d 1031 (11th Cir. 1983). Rehearing en banc was granted,

and the district court was affirmed by an equally divided court.

Darden, 708 F.2d 646 ( 11th Cir. 1983). On second rehearing, the

en banc court reversed, granting relief on the Witherspoon claim.

725 F.2d 1526 (11th Cir. 1985).

9 <rhe Court initially granted certiorari upon a petition that

included the Witherspoon claim, see Darden v. Florida, 45

U.S.L.W. 3356 (Nov. 9, 1976) , but subsequently limited the grant

of certiorari to the issue of prejudicial prosecutorial summa

tion. 429 U.S. 1036 ( 1977) .

25

This Court vacated and remanded for reconsideration in light

of Wainwright v. Witt* _____ O.S. / 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985) . On

remand, the en banc court denied relief, two judges dissenting.

Darden, 767 F.2d 752 (11th Cir. 1985).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The closing arguments made by the prosecutors in this case

have been condemned by virtually every judge who has looked at

them. They have never been defended by the state as proper. These

arguments flouted every rule of professional conduct recognized

by the organized Bar. They were calculated to divert the jury's

attention from the central factual issues in the case, especially

the issue whether the prosecution's problematic identification

evidence was sufficiently persausive to convict Mr. Darden.

Crafted to evoke passion and inflame prejudice, these arguments

violated Mr. Darden's most basic rights: to a fundamentally fair

and reliable determination of his guilt or innocence and of the

appropriate sentence.

"The actual impact of a particular practice on the judgment

of jurors cannot always be fully determined. But this Court has

left no doubt that the probability of deleterious effects on

fundamental rights calls for close scrutiny." Estelle v.

Williams, 425 U.S. 501, 504 (1976). Because the prosecution's

improper arguments were designed and likely to affect the

reliability of the factfinding process, they introduced more than

a probability of actual prejudice. In such a case, the state

26

should be required to demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that

the arguments were harmless, Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18

(1967), — if if asserts that they were. Here, the state has

shown nothing of the sort. To the contrary, it appears only too

likely that the prosecutor's arguments achieved the result they

plainly sought: to tip the scales in favor of a verdict of

guilt. Nor, on this record, can the arguments that strove

improperly to emotionalize the determination to impose the death

sentence be said to have had no effect. Caldwell v. Mississippi^

4 7 2 o.S. ___, 8'6 L:Ed. 2d 231 , 247 ( 1985). Accordingly, both the

conviction and the sentence must be reversed.

Reversal of the death sentence is required on two .other

grounds: First, prospective juror Murphy was excluded solely on

the basis of a single question and answer that disclosed strong

scruples against the death penalty. This question, however,

faj_]_ecj to inquire — and the answer, therefore, failed to

establish — whether those scruples were so strong that they

would substantially impair Mr. Murphy's performance as a fair and

impartial juror or whether Mr. Murphy would be able to subordi

nate those scruples to the law. Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S.

, 83 L.Ed.2d 841 (1985). Because his exclusion for cause was

the result of a purely legal error, reversal is required on the

face of the record.

Second, Mr. Darden was deprived of the effective assistance

of counsel at the sentencing stage. In effect, he was left to

face the jury alone: He made a short statement in mitigation at

27

the urging of the trial judge, but no other mitigating evidence

was presented. This was because counsel failed entirely to

investigate or prepare for the sentencing hearing until twenty

minutes before it began. Had they done so, they could have

presented relevant, available information concerning Mr. Darden's

background and character. This mitigating information would have

counteracted much of the prosecutor's improper and unsupported

assertions and arguments. Because of counsel's failure, Mr.

Darden's sentencing hearing was less an adversary proceeding than

the sacrifice of an unaided and unshielded prisoner to the

prosecutorial gladiator.

ARGUMENT

I THE PROSECUTION'S CALCULATED, UNPROFESSIONAL AND INFLAMMA

TORY CLOSING ARGUMENT ROBBED THE DETERMINATION OF PETITION

ER'S GUILT OF THE FUNDAMENTAL FAIRNESS REQUIRED BY DUE

PROCESS AND DEPRIVED THE DETERMINATION OF SENTENCE OF THE

RELIABILITY REQUIRED BY THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT________________

There is no dispute about the nature of the prosecution's

conduct; it has received universal condemnation. The federal

district court observed that: "Anyone attempting a text-book

illustration of a violation of the Code of Professional Respon

sibility, Canon 7, EC 7-24, and DR 7—106(c)(4) could not possibly

improve upon th[is] example." 513 F.Supp. at 955. The Florida

Supreme Court acknowledged that "under ordinary circumstances

[it] would constitute a violation of the Code of Professional

Responsibility." 329 So.2d at 290. The majority of the court of

appeals acknowledged that the argument "can only be described as

28

tasteless and unprofessional.../" 669 F.2d at 1036/ noting that

it "contained personal opinions" in violation of the Code and

that "the prosecutor's comments would have been reversible error

in an appeal from a federal case." Id. at 1035-36. The district

court described the argument as "a series of utterly tasteless

and repulsive remarks...," "pointless," 513 F.Supp. at 955, and a

"tirade." Id_. at 953. The dissenting justices in the Florida

Supreme Court noted that the "remarks of the prosecutor in the

case at bar can only be characterized as vituperative personal

attacks upon the appellant and as appeals to passion and preju

dice." 329 So.2d at 293. The federal magistrate referred to the

"numerous instances of prejudicial prosecutorial argument as

"improper, repeated, prejudicial." Magistrate-^ Report at 22.,

Even the state concedes: "No one has ever even weakly suggested

that McDaniel's closing remarks were anything but improper...."

513 F.Supp. at 952.

We show below that this extreme misconduct deprived peti

tioner of fundamental fairness in the determination of his guilt

or innocence and of reliability in the determination of his

sentence. That being so, the ensuing prejudice is palpable. If

a defendant is convicted and sentenced to death as a result of

oroceed i ngs that are fundamentally unfair and unreliable,

prejudice is presumed; the burden is properly cast on the state

to show that there was none. But even if petitioner bore the

burden, the circumstances and extent of this misconduct in the

context of this case demonstrate prejudice.

29

In the sections that follow, we first discuss the standards

that control analysis under the due process clause. We then

consider the claim as to sentence in light of the eighth amen

dment standards repeatedly reaffirmed by this Court. Finally, we

assess the prejudice to Mr. Darden on the unique facts of this

case.

A. Mr. Darden Was Denied Fundamental Fairness in the

Determination of his Guilt or Innocence

" [N]ot every trial error or infirmity which might call for

application of supervisory powers correspondingly constitutes a

•failure to observe the fundamental fairness essential to the

very concept of justice.’" Donnelly v. De Christoforo,•416 U.S.

637, 642 (1974) (quoting Lisenba v. California, 314 U.S. 219, 236

(1941)). But some do.

The relevant question ... inescapably imposes

upon this Court an exercise of judgment upon

the whole course of the proceedings in order

to ascertain whether they offend those canons

of decency and fairness which express the

notions of justice of English-speaking peoples

even toward those charged with the most

heinous offenses.

Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46, 67-68 (1947) (Frankfurter,

J., concurring).

The Court is not left at large in this inquiry.

[S]tate criminal processes are not imaginary

and theoretical schemes but actual systems

bearing virtually every characteristic of the

common—law system that has been developing

contemporaneously in England and this country.

30

The question thus is whether given this kind

of system a particular [rule] is fundamental

— whether, that is, [it] is necessary to an

Anglo-American regime of ordered liberty."

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 149-50 (1968); accord Johnson

v. Louisiana, 406 O.S. 356, 372 n. 9 (1972) (Powell, J., concur

ring) ("the focus is, as it should be, on the fundamentality of

that element viewed in the context of the basic Anglo-American

jurisprudential system common to the States."). The "better guide

... is disclosed by 'the existing laws and practices in the

Nation.'" Baldwin v. New York, 399 U.S. 66, 70 (1970) (quoting

Duncan, 391 U.S. at 161).

On this score, there is no doubt. The calculated, inflam

matory argument of the prosecution in this case did more than

draw the universal condemnation of the courts below. It violated

the specific prohibitions embodied in the law of every state and

the District of Columbia, for each state has adopted either the

Code of Professional Responsibility or the new ABA Model Rules of

Professional Conduct (1983). The Code provides that:

In appearing in his professional capacity

before a tribunal, a lawyer shall not:

(1) State or allude to any matter that he

has no reasonable basis to believe is

relevant to the case....

(2) Assert his personal knowledge of the

facts in issue, except when testifying

as a witness.

(3) Assert his personal opinion as to the

justness of a cause, as to the credibi

lity of a witness, ... or as to the

guilt or innocence of an accused....

31

DR 7-106(C). These prohibitions have been carried forward

without change in the Model Rules, Rule 3.4(e). The ABA Stan

dards for Criminal Justice (2d ed. 1980) provide:

(a) The prosecutor may argue all

reasonable inferences from evidence in the

record. It is unprofessional conduct for the

prosecutor intentionally to misstate the

evidence or mislead the jury as to the

inferences it might draw.

(b) It is unprofessional conduct for the

prosecutor to express his or her personal

belief or opinion as to the truth or falsity

of any testimony or evidence or the guilt of

the defendant.

v (c) The prosecutor should not use

arguments calculated to inflame the passions

or prejudices of the jury.

(d) The prosecutor should refrain from

argument which would divert the jury from its

duty to decide the case on the evidence, by

injecting issues broader than the guilt or

innocence of the accused under the controlling

law, or by making predictions of the conse

quences of the jury's verdict.

(e) It is the responsibility of the

court to ensure that final argument to the

jury is kept within proper, accepted bounds.

10

Id. § 3-5.8.

The prosecutor in this case flouted each and every one of

these proscriptions: He interjected irrelevant issues such as the

culpability of the prison system; he asserted personal opinions

^ Identical restrictions apply on the conduct of the defense. Id_. ,

§ 4-7.8.

32

and beliefs regarding the veracity of facts stated by Mr. Darden

in his sworn testimony and not rebutted by any evidence in the

case; he expressed a personal opinion of Mr. Darden's guilt and

repeatedly asserted his personal opinion that Mr.-Darden was

lying. Moreover, his entire argument was calculated to inject

into the trial issues broader than guilt or innocence: the

appropriateness of the death penalty (which he argued extensively

at the guilt/innocence stage after expressly acknowledgeing that

it was not an issue at that stage) ; the public misfortune that

Mr. Darden had not yet been killed by a shotgun, automobile

accident, or suicide; the culpability of the prison system; Mr.

Darden's culpability for having a driver's license and a girl

friend; and the need to execute Mr. Darden to insure that he did

not get out and commit other crimes. McDaniel repeatedly and

shrewdly appealed to the passions and prejudices of the jury.

All of this served only to divert the jury from what it should

have focused on at the guilt/innocence stage: the evidence, and

whether Mr. Darden was in fact the guilty man.

The Code, the Model Rules, and the A3A Standards are not,

even by dint of the universality of the consensus they express,

ipso facto incorporated into the due process clause. But, as has

been expressed elsewhere at greater length, neither are they the

expression of a mere ethical nicety. Rather, as explained in the

11 Brief of a Group of American Law School Teachers of Professional Responsibility Amici Curiae in Support of the Petition for

Certiorari in Tucker v^ Kemp, No. 85-5496, filed October 28,

1984.

33

12

ethical considerations accompanying the rule, they serve as a

necessary concomraitant to the principle that: "In order to bring

about just and informed decisions, evidentiary and procedural

• rules have been established by tribunals to permit the inclusion

of relevant evidence and argument and the exclusion of all other

considerations." EC 7-24. "Rules of evidence and procedure are

designed to lead to just decisions and are part of the framework

of the law...; and a lawyer should not by subterfuge put before

a jury matters which it cannot properly consider." EC 7-25.

These concerns mirror directly the concerns of the due

process clause. "Court proceedings are held for the solemn

purposes o.f endeavoring to ascertain the truth which is the sine

qua non of a fair trial." Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532, 540

( 1965) . "This Court has declared that one accused of crime is

entitled to have his guilt or innocence determined solely on the

basis of the evidence introduced at trial, and not on grounds of

... other circumstances not addressed as proof at trail." Taylor

v. Kentucky, 436 U.S. 478 , 487 ( 1 978); accord Estelle v.

Williams, 425 U.S. 501, 503 (1976).

The constitutional vice of the arguments exhibited here is

orecisely the same as the ethical one: "the focus of the trial,

and the attention for the participants therein, are diverted from

the ultimate question of guilt or innocence that should be the

12 Although"[t]he ethical considerations are aspirational in

character...," Code of Professional Responsibility, Preamble and

Preliminary Statement at 1, they also express "the reasons

underlying these standards." Id. at n. 7.

34

central concern of a criminal proceeding." Stone v. PoweU, 428

U.S. 465, 489-90 (1976). • Arguments that inject passion and

prejudice, inflame the jury, invoke prosecutorial position and

expertise to preempt determination of the credibility of wit

nesses and the truthfulness of evidence "deflect [] the truthfind

ing process...." Id̂ _ at 490. Similarly, arguments about the

mistakes of the prison system or the parole board, the appropri

ateness of the death penalty, and the defendant’s purported

future dangerousness have no place at the guilt/innocence stage;

"it interjects irrelevant considerations into the factfinding

process, diverting the jury’s attention from the central issue of

whether the State has satisfied its burden of proving beyond a

reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty--- " Beck v^

Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 642 (1980).

The universal consensus of the organized Bar, adopted as the

law of each of the fifty states and the District of Columbia,

shows that prosecutorial misconduct of these kinds threatens the

"just and informed decisions" necessary to our system of truth-

13 In Karris v. State, 414 So. 2d 557 (Fla. 3d DCA 1982), a case much like tms o n e T an eyewitness identified tbe^fendantas

twice having robbed a laundromat. The defendant testified that

he had not been in the laundromat on either date. The prosecutor

made referrences to the rampage of crime m the community and

expressed his personal belief in the defendant s guilt. The

District Court of Appeals reversed the conviction. It is the

responsibility of the prosecutor to seek justice, not merely to

convict. That responsibility will be more nearly met when the

iurv is permitted to reach a verdict on the merits without

counsel indulging in appeals to sympathy, bias, passion, or

prejudice." Id_. at 558.

35

That consensus is persuasive evidence offinding. See EC 7-24.

the meaning of due process in our system.

This conclusion is buttressed by the decisions of this

Court. In Donnelly v. De Christoforo, the Court phrased the

inquiry as whether "a prosecutor's remark ... so infected the

trial with unfairness as to make the resulting conviction a

denial of due process." 416 O.S. at 643. On the basis of "an

examination of the entire proceedings...," id., the Court conclu

ded that it did not. It premised, that conclusion on three

factors.14 First, the remark in Donnelly was "an ambiguous

one___ - id. at 645. Second, it "was but one moment in an

. extended trial--- " Id. Third, it "was followed by specific

disapproving instructions." Id.

"Here, in contrast, the prosecutor's remarks were quite

focused, unambiguous, and strong." Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472

U.S. , 86 L.Ed.2d 231, 246 (1985). They were woven throughout

the whole fabric of the prosecutor's summation. Unlike Donnelly,

there was no curative instruction. Although the trial judge in

Mr. Darden's case did not go quite as far in endorsing the

1 4 "which the

... as toThe Donnelly Court first distinguished the^case in

prosecutor' s remarks so prejudiced a specific right amount to a denial of that right...,'" 416 U.S. at 643 , m

determining to apply the more general standard of due process.

Id .

>jhere were instructions to the jury that it should consider only

the evidence. See R. 824, 862, & 864. And there had been a warninq before the“summation that arguments are not evidence. But

there was no curative instruction. There were no instructions

after the summations either that the prosecutors had erred or

that arguments are not evidence.

36

improper comment as did the judge in Caldwell, 86 L.Ed.2d at

243/ he came close. He both endorsed the lawyers' summations

16generally beforehand and brushed aside or overruled the objecti

ons to the prosecutor's argument, thus effectively indicating

"to the jury that the remarks were proper---" See Caldwell, 86

L.Ed.2d at 243.

In Donnelly, the Court also noted that "closing arguments

... are seldom carefully constructed in toto before the event;

improvisation frequently results in syntax left imperfect and

meaning less than crystal clear." 416 U.S. at 646-47. Here, m

contrast, the meaning was crystal clear. The offending comments

were not limited to a single, isolated remark but rang out

recurrrent themes central to the summation.

Indeed, the very nature of these improper comments invok

ing irrelevant issues designed to inflame the jury and motivate

it to convict the defendant — point unerringly to the conclusion

that the prosecutor employed "improper methods calculated to

produce a wrongful conviction...." Berger v. United States, 295

U.S. 78 , 88 ( 1935). There is no other explanation for the fact

16 The trial judge had admonished the jury before closing argument

that it could rely on the expertise and experience of counsel and

that, therefore, their views on the evidence would be very

helpful. R. 713-14. The prosecutors took advantage of this and

asked the jury to accept their personal beliefs of Mr. Darden's

untruthful ness and guilt.

17 The Donnelly Court acknowledged that "these general observations

in no way justify prosecutorial misconduct," id. at 647 , but

instead merely served to show that it was not necessarily true

that the jury had drawn the impermissible inference from the

prosecutor's ambiguous remark. Id.

that McDaniel focused on the need for the death sentence in his

arguments at the guilt/innocence stage of the trial. As the

district court found: "It is apparent in reading the arguments in

their entirety ... that the prosecutor had a dual purpose in mind

when he attacked the Division of Corrections..., he was also

making, in effect, his principal argument in support of the death

penalty." Darden, 513 F. Supp. at 953. "This conclusion is

buttressed by the fact that, at the conclusion of the penalty

phase of the trial, the prosecutor's argument to the jury is

contained on a single page of transcript." ld_. at 953 n. 10.

Yet, at the guilt/innocence stage, "the central issue" was

whether Mr. Darden was the guilty man, "whether the State ha[d]

satisfied its burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that

the defendant [wa]s guilty of a capital crime." Beck, 447 U.S.

at 642 (emphasis added) .

Given that, the prosecutorial arguments prohibited by the

Code, the Model Rules, and the ABA Standards — and exhibited in

case — — serve only to pervert and distort the truthfinding

process, it is wholly inappropriate to require the defendant to

prove that he was prejudiced by them. "Prejudice in these

circumstances is so likely that case by case inquiry into

orejudice is not worth the cost. ... Moreover, such circum

stances involve impairments ... that are easy to identify and,

for that reason and because the prosecution is directly respon

sible, easy for the government to prevent." Strickland v.

Washington, ___ U.S. ___, 80 L.Ed.2d 674, 696 (1984). "When the

38

prosecutor's conduct is considered to have transgressed the basic

principles of fair play embodied in the due process clause... the

standard is strict indeed." Kyle v. United States, 297 F.2d 507,

18

513 (2d Cir. 1961) (per Friendly, C.J.). Such "constitutional

error, in illegally admitting highly prejudicial evidence or

comments, casts on someone other than the person prejudiced by it

the burden to show that it was harmless." Chapman v. California^

386 U.S. 18, 24 (1967).

This conclusion is corroborated by the Court's recent

decision in Caldwell. The Court found that the specific comments

at issue in that case "so affect[ed] the fundamental fairness of

ti\e sentencing proceeding as to violate the Eighth Amendment." 86

L . Ed. 2d at 246 . In reaching that conclusion, it observed:

"Because we cannot say that this effort had no effect on the

sentencing decision, that decision does not meet the standard of

reliability that the Eighth Amendment requires." Id_. at 247

18 Judge Friendly noted that:

The conclusion we draw... is that the standard of

how serious the probable effect of an act or

omission at a criminal trial must be in order to

obtain the reversal... is in some degree a

function of the gravity of the act or omisssion;

the strictness of the application of the harmless

error standard seems somewhat to vary, and its

reciprocal, the required showing of prejudice, to

vary inversely, with the degree to which the

conduct of the trial has violated basic concepts

of fair play.

297 F.2d at 514. On this basis, Judge Friendly concluded that for deliberate prosecutorial misconduct, as is true in Mr.

Darden's case, the showing of prejudice required should be at its

nadir and the harmless error rule should apply. Id_. at 514-15

39

convictions obtained by(emphasis added). By the same token,

such fundamentally unfair proceedings must be reversed: "To

insure that the death penalty is indeed imposed on the basis of

•reason rather than caprice or emotion,' we have invalidated

procedural rules that tended to diminish the reliability of the

sentencing determination. The same reasoning must apply to rules

that diminish the reliability of the guilt determination." Beck,

447 U.S. at 638 (quoting Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349, 358

(1978)) (footnote omitted).

3 . Mr. Darden Was Denied Reliability in the Determination

his oi Sentence

The effect of McDaniel's impermissible arguments on sentenc

ing must also be considered. For as the district court found,

this was his argument on sentencing; the prosecutor made no other

argument to speak of. 513 F.Supp. at 953 and n. 10.

The effect of his argument was to inflame the jury, to evoke

its passions and invoke its prejudices, and to lead it to impose

the death penalty for impermissible reasons. McDaniel repeated

ly wished that Mr. Daraden had killed himself, slit his own

throat, shot himself, or wrapped himself around the pole in the

automobile accident. He referred to him as an animal and as

needing "a leash on him and a guard at the other end of that

leash." R. 750. He asked the jury to strike a blow at the

correctional system responsible for Mr. Darden's furlough and

urged his personal opinion that its irresponsibility required the

40

death sentence: "That’s the only way that I know that he is not

going to get out on the public. It’s the only way I know. It's

the only way I can be sure of it." R. 753. He did not fail to

invoke race, noting the description of the assailant as "the

colored male..., R. 762, and closing with the "circumstantial

evidence, surrounding that wreck, the time, the place, his

— color...." R. 780.

In making these arguments, McDaniel violated each relevant

provision of the Code and the ABA Standards. He argued matters

that he had "no reasonable basis to believe ... relevant and

that were "not... supported by admissible evidence." DR 7-106(C)

(1). He asserted his personal knowledge of these "facts", which

he had thus improperly put in issue. Id_., subsection (3). He

asserted his personal opinion oji the justness of the death

sentence in this case. Id., subsection (4). He used argument

"calculated to inflame the passions or prejudices of the jury."

ABA Standards S 3-5.8(c). And he "ma[de] predictions of the

consequences of the jury's verdict" when that question was not

open to consideration under the applicable sentencing law. See

id., subsection (d).

In violating these ethical proscriptions and in making these

impermissible arguments, McDaniel deprived Mr. Darden of a trial

that satisfied the "heightened 'need for reliability in the

determination that death is the appropriate punishment in a

specific case...,'" Caldwell, 86 L.Ed.2d at 246 (quoting Woodson

v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280, 305 (1976) (plurality opinion)),

41

See , e .g. ,which has been a repeated concern of this Court

ral ifornia v » Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 998-99 (1983). A sentence of

death obtained in this manner cannot be countenanced without

disregarding the "vital importance to the defendant and the

community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and

appear to be, based on reason rather than caprice or emotion."

Gardner, 430 U.S. at 358. The arguments used in this case were

(to invert Justice O ’Connor's observation) "extraordinary

measures to ensure that the prisoner to be executed is afforded

process that will guarantee, as much as is humanly possible, that

the sentence was ... imposed out of whim, passion, prejudice, or

mistake." Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 118 (1982)(O’Connor,

j., concurring).

Under these decisions, an exacting scrutiny is demanded of

the process by which death is imposed. As Judge Friendly noted in

K^le:

[T]he pans contain weights and counterweights

other than the interest in a perfect trial.

Sometimes only a small showing of preducice,

or none, is demanded because that interest is

reinforced by the necessity that "The adminis

tration of justice must not only be above

reproach, it must also be beyond the suspicion

of reproach," ... and by the teaching of experience that mere admonitions are insuffi

cient to prevent repetition of abuse.

297 F.2d at 514 (quoting People v. Savvides, 1 N.Y. 2d 554, 154

N.Y.S. 2d 885, 136 N.E. 2d 853 (1956) (per Fuld, J.)). The Court

recognized this point in its decision in Caldwell just last

42

Term, and demanded that we be able to say that the improper

argument "had no effect on the sentencing decision--- " 86 L.Ed.

2d at 247. Especially in light of the persistence of unchecked

prosecutorial misconduct of this sort, see Brief of a Group of

American Law Teachers of Professional Responsibility as Amici

Curiae in Tucker v. Kemp, No. 85-5496, at 10-12, it is clear that

Caldwell struck the correct balance. Accordingly, this death

sentence must be reversed.

C. * Although Mr. Darden Is Entitled to Relief under the-

Harmless Error Doctrine, He Suffered Actual__a n?_

Substantial prejudice

The magistrate's asessment of the effect of McDaniel s

argument is difficult to fault.

The case against Darden was not a weak case,

but it did depend on the jury's determination