Attorney General of Texas v. Entz Memorandum in Response to Cross-Petition for Writ of Certiorari of Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Attorney General of Texas v. Entz Memorandum in Response to Cross-Petition for Writ of Certiorari of Respondents, 1993. 6d3072ec-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d56d9208-2e74-4b4c-a428-bd89a393f7d9/attorney-general-of-texas-v-entz-memorandum-in-response-to-cross-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-of-respondents. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

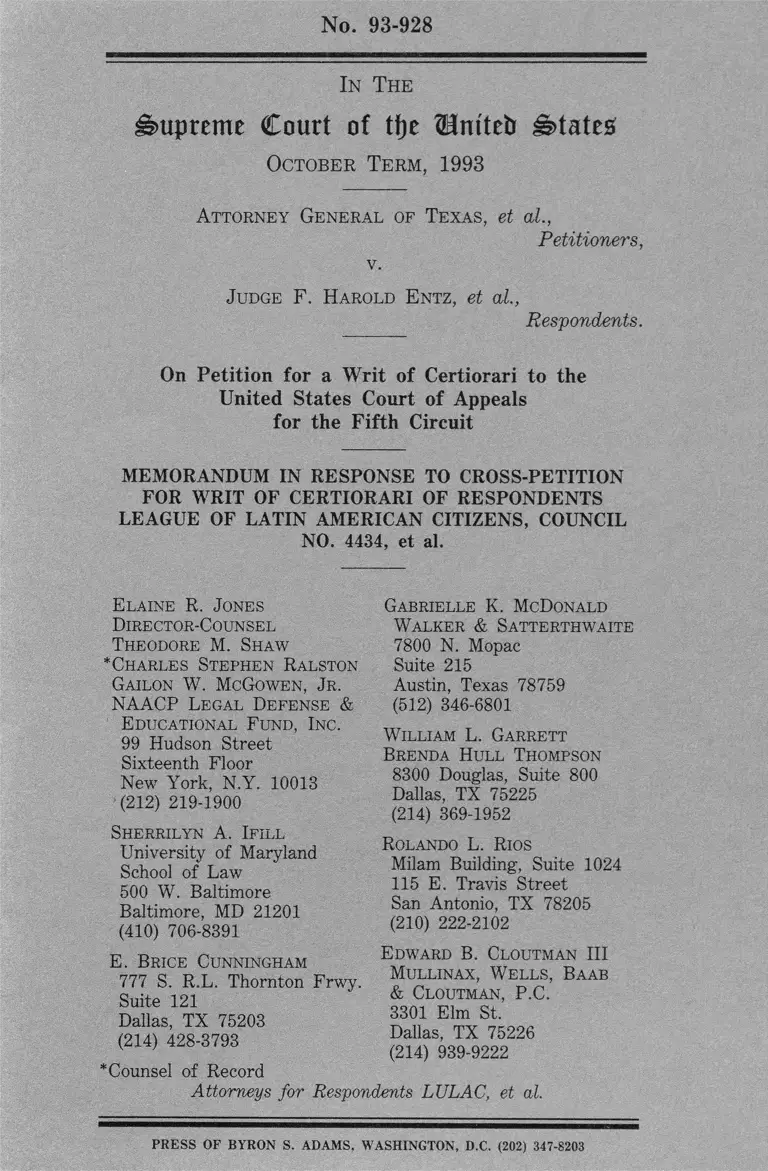

No. 93-928

In The

Suprem e Court of tf)e Mm'tetr s t a t e s

October Term, 1993

Attorney General of Texas, et al,

Petitioners,

v.

J udge F. Harold E ntz, et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MEMORANDUM IN RESPONSE TO CROSS-PETITION

FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI OF RESPONDENTS

LEAGUE OF LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS, COUNCIL

NO. 4434, et al.

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

*Charles Stephen Ralston

Gailon W. McGowen, J r.

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

University of Maryland

School of Law

500 W. Baltimore

Baltimore, MD 21201

(410) 706-8391

E. Brice Cunningham

777 S. R.L. Thornton Frwy.

Suite 121

Dallas, TX 75203

(214) 428-3793

Gabrielle K. McDonald

Walker & Satterthwaite

7800 N. Mopac

Suite 215

Austin, Texas 78759

(512) 346-6801

William L. Garrett

Brenda Hull Thompson

8300 Douglas, Suite 800

Dallas, TX 75225

(214) 369-1952

Rolando L. Rios

Milam Building, Suite 1024

115 E. Travis Street

San Antonio, TX 78205

(210) 222-2102

Edward B. Cloutman III

Mullinax, Wells, Baab

& Cloutman. P.C.

3301 Elm St.

Dallas, TX 75226

(214) 939-9222

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Respondents LULAC, et al.

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-S203

No. 93-928

In The

Suprem e Court of ti)e ® m teb S t a t e s

October Term, 1993

Attorney General of Texas, et al.,

Petitioners

v.

Judge F. Harold Entz, et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

MEMORANDUM IN RESPONSE TO CROSS-PETITION

FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI OF RESPONDENTS

LEAGUE OF LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS, COUNCIL

NO. 4434, et al.

Respondents League of Latin American Citizens,

Council No. 4434, et al., the petitioners in No. 93-630, League

of Latin American Citizens, Council No. 4434, et al. v. Attorney

General of the State of Texas, et al., support the grant of

certiorari in the present case. The question presented is the

same as Question 3 presented in No. 93-630. For the reasons

set out in their Reply to Briefs in Opposition and

Supplemental Brief in Support of the Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari filed in No. 93-630, the Court should grant certiorari

in both cases and should grant certiorari on all of the questions

presented in No. 630.

2

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the cross-petition for a writ

of certiorari of the Attorney General of Texas, et al, should be

granted, along with the petition for a writ of certiorari in No.

93-630.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

* Charles Stephen Ralston

Gailon w . McGowen, Jr.

NAACP Legal defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

University of Maryland

School of Law

500 W. Baltimore

Baltimore, MD 21201

(410) 706-8391

E. Brice Cunningham

777 S. R.L. Thornton Frwy.

Suite 121

Dallas, TX 75203

(214) 428-3793

Gabrielle K. McDonald

Walker & Satterthwaite

7800 N. Mopac

Suite 215

Austin, Texas 78759

(512) 346-6801

William L. Garrett

Brenda Hull Thompson

8300 Douglas, Suite 800

Dallas, TX 75225

(214) 369-1952

Rolando L. Rios

Milam Building, Suite 1024

115 E. Travis Street

San Antonio, TX 78205

(512) 222-2102

Edward B. Cloutman III

Mullinax, Wells, Baab

& Cloutman, P.C.

3301 Elm St.

Dallas, TX 75226

(214) 939-9222

*Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Respondents LULAC, et al.