Plaintiffs' and Defendants Revised Stipulations of Fact

Public Court Documents

June 6, 1995

50 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' and Defendants Revised Stipulations of Fact, 1995. 0e1dd0ef-a146-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d587881e-35fe-40a8-918f-c1313112ae30/plaintiffs-and-defendants-revised-stipulations-of-fact. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

@ SN

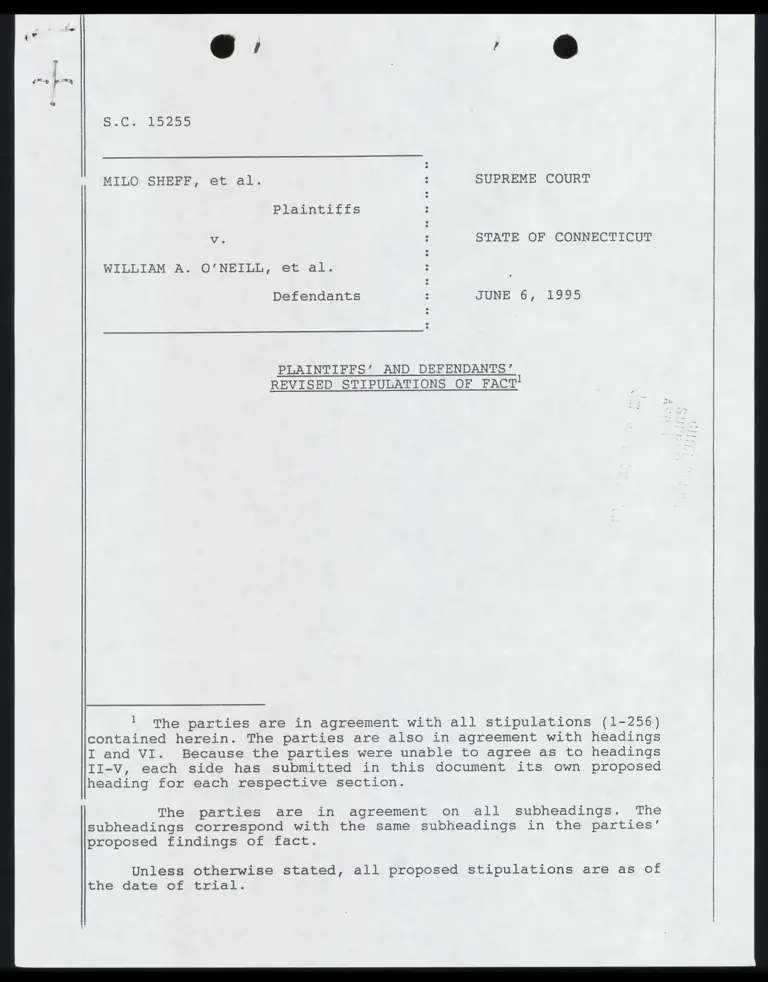

5.C..15255

‘MILO SHEFF, et al. : SUPREME COURT

Plaintiffs

Vv. - STATE OF CONNECTICUT

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.

Defendants $ JUNE 6, 1995

PLAINTIFFS’ AND DEFENDANTS’

REVISED STIPULATIONS OF FACT!

] The parties are in agreement with all stipulations (1-256)

contained herein. The parties are also in agreement with headings

I and VI. Because the parties were unable to agree as to headings

II-V, each side has submitted in this document its own proposed

heading for each respective section.

The parties are in agreement on all subheadings. The

subheadings correspond with the same subheadings in the parties’

proposed findings of fact.

Unless otherwise stated, all proposed stipulations are as of

the date of trial.

ORDER

2%, 1995

foregoing, Stipulation is hereby

For good cause shown J aged

-

Plaintiffs’ and Defendants’ Revised Stipulations of Fact

NOTICE SENT: June 28, 1995

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

MARTHA STONE

PHILIP D. TEGELER

JOHN BRITTAIN

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, ATTORNEY GENERAL

BERNARD F. MCGOVERN, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARTHA WATTS PRESTLEY, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

GREGORY T. D’/AURIA, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

CAROLYN K. QUERIJERO, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

THEODORE SHAW

DENNIS D. PARKER

SANDRA DEL VALLE

CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN

SO A5285

MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPREME COURT

vs. STATE OF CONNECTICUT

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al. JUNE 27, 1885

EI. NDING

Pursuant to:this Court's Order of May 1%, 1995 that the

trial court review any filings relating to factual issues

other than the parties’ stipulation of facts and proposed

findings of fact that it may find helpful, the court

incorporates herein by way of introduction to its findings

certain amendments to the complaint that were made by the

plaintiffs prior to trial for the purpose of narrowing the

gcope of their offer of proof, as well as a representation

made by counsel for the plaintiffs at the time of final

argument relating to the defendants’ claim that the court

lacks jurisdiction because of the plaintiffs’ failure to

join the Hartford area towns and school districts as

necessary parties in this action.

I.

On July 21, 1992, the plaintiffs filed a request to

amend paragraphs 47 and 50 of their original complaint, and

to delete paragraph 71 in its entirety, because "the state’s

“yoke in segregated housing patterns 1s not a necessary part

or

of Their affirmative case . . . and they wish to eliminate

LZ Mir

any ambiguity in the pleadings that may be relied on by the

~

—

ethnic and socioeconomic balance in the school districts of

the Hartford metropolitan area. (Trent, 7/134; Gordon,

13/149-151)

158. Mandatory student reassignment plans to achieve

racial balance, whether intradistrict or interdistrict, are

ineffective methods of achieving integration, whether they

are mandated by racial imbalance laws or by court order.

(Rossell, 26B/34)

159. Proposed solutions to the problems of racial,

ethnic and economic isolation which rely on coercion and

which fail to offer choices and options either do not work

or have unacceptable consequences. (PX. -398, Pp. 8; Tirozzi,

PX 494, pp. 82-93)

160. Moreover, reliance on coercive measures alone,

without providing quality education and maintaining it at

the appropriate levels throughout the region, do not seem to

work and fail to produce the outcomes that are educationally

desirable. (Foster, 21/158-61)

161. Integration in its fullest and most meaningful

sense can only be achieved by building affordable housing in

suburban areas in order to break up the inner city ghettos,

and by making urban schools more attractive for those who

live outside the city. {Tirozzi, PX 494, p. 34; Mannix,

PY 495, po. 22-23)

/ 7 /

A / vd

4 7

Z- 7 yt Cg

: /

Harry Hammer

Trial Judge

\V.

28

Substituted pg. 28 for Findings dated June 27, 1995

NOTICE SENT: June 28, 1995

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

MARTHA STONE

PHILIP D. TEGELER

JOHN BRITTAIN

WILFRED RODRIGUEZ

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, ATTORNEY GENERAL

BERNARD F. MCGOVERN, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARTHA WATTS PRESTLEY, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

GREGORY T. D’/AURIA, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

CAROLYN K. QUERIJERO, ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

MARIANNE ENGELMAN LADO

THEODORE SHAW

DENNIS D. PARKER

SANDRA DEL VALLE

CHRISTOPHER A. HANSEN

07/05/95 13:00 T203 241 7666 U OF CT LAW SCHL @oo3

VE rT!

Judge Calls

Poverty Root

Of School Ills

By GEORGE JUDSON

HARTFORD, June 27 — Expand-

ing on a ruling he issued in April, a

state judge sald today that poverty,

not segregation, was the cause of the

poor performance of students in the

Hartford schools.

The finding came in a lawsuit

seeking to integrate the city's .

schools with those of its suburhs — a

case that has already been appealed

- to the State Supreme Court,

The fact that Hartford's school- Re

children, the poorest and most ra-

cially segregated in Connecticut,

achieve the state's lowest scores on

standardized tests reflects the disad- +

vantages of family poverty rather

than the quality of their schools,

wrote the Superior Court judge, Har-

ry Hammer.

“Hartford should not be consid-

ered a negative setting for education

in that the state is still meeting its

primary responsibility of educating

its schoolchildren, and there is some

outstanding education going on its

schools,” Judge Hammer wrote.

The judge had already ruled

against the plaintifls in the case, of

known as Sheft vs. O'Neill, declaring - |

that they had failed to prove that the

state was responsible for the segre-

gated conditions in Hartford's

schools,

Since the state had not caused the

conditions, he wrote, he had no rea-

son to consider the plaintiffs’ const-

tutional argument that segregation

by race and class, regardless of how

it came about, denied children an

equal educational opportunity.

Black and Puerto Rican children

make up 92 percent of Hartford's

24,000 students, two-thirds of whom

live in poverty.. Their scores on

standardized tests are the lowest in

the state,

Today, in ndditionat findings re-

quested by the Supreme Court, .

Judge Hammer not only repeated

his concligion that the state was not

at fault, but suggested that Hart.

ford's schools were doing as well as

any schools could, considering the

Sativa background of their stu-

ents.

He rejected the arguments uf civil

rights lawyers for the plaintiffs that

Hartford's last-place rank on Con-

necticut’s standardized tests, far be-

luw average scores in nearby sub-

orbs, proved the failure of its

schools.

“The disparity in test scores does

: not indicate that Hartford is doing an

inudequate or a poor job in educating

its students or that its schools are

failing,” Judge Hammer wrote, Yhe-

cause the predicted scores based

upon the relevant socioeconomic fac-

ors are about at the levels that one

would expect.”

The judge alsa appeared to reject

the civil rights lawyers’ proposed

solution to the concentration of poor

children in Hartford: combining the

city's schools with those in 2} sur-

rounding communities. He agreed

with lawyers for the state that court-

ordered schoo) integration is either

“ineffective” or has “unacceptable

consequences.”

The only way to achieve meaning-

ful integration, he wrote, was fo

break up segregated housing pat-

terns by building affordable housing

in suburbs, which is beyond his

scope, and by making Hartford

schools more attractive to people

who live outside the city.

The state, he said, was already

pursuing policies intended to im-

prove schools in Hartford and other

cities and to promote voluntary inte-

gration measures between school

districts.

Lawyers for both sides will now

prepare briefs for the Supreme

Court; oral arguments before the

court are expected in September or

October,

Today Attorney General Richard

Biumenthal said Judge Hammer's

new findings “very significantly

srrengthen and support the state's

argument that Connecticut has met

and continues to meel its obliga-

tions."

07/05/95 13:00 T203 241 7666

: Har7 ford Courant”

Phainiises in“the landmark Sheff vs. O'Neill

sschool desegregation case being reviewed by the

istate Supreme Court appear to be backtracking

=0h a promise to attack de facto segregated hous-

“ing next.

* - Their reluctance is understandable; they may

“rit want to divert focus from the Sheff case.

-~ Eyentually, however, the issue of housing

oriust receive similar attention. Where children

“live determines where they go to school. Inte-

-grate the neighborhood, and you integrate the

rgchools.

£ If only it were that simple. Zoning restric-

rtions, such as large lot sizes and preference for

¢smgle-family dwellings, have kept suburbs pri-

marily the province of the prosperous, Mortgage

lending practices, though improving, tend to fa-

vor traditional middle-class families.

2” Affordable housing initiatives have helped a

Fstnall number of low-income people own or rent

' thomes in the suburbs. More often than not,

though, affordable housing proposals draw pro-

test. Mention multifamily development especial-

«Ij; and you're likely to hear the same rhetoric:

B=

Ld

Housing linked to schoo

U OF CT LAW SCHL

7// g§5° A/c

l diversity

“We don’t want low-income projects (read: urban

problems and minorities) in our town.” :

In Connecticut, where a wide chasm sepa-

rates the rich from the poor, the route out of the

impoverished cities is strewn with roadblocks

‘that must be removed. As long as there are large

pockets of poverty, the well-to-do will continue to

flee the cities. tr

Although falling real-estate prices have

opened the suburbs to economic and racial diver-

sity somewhat, the public mood shows signs of

swinging away from advances of the past few

decades. :

Towns had the opportunity to fashion volun-

tary strategies for integrating schools. Most re-

fuged to adopt them. The state’s school racial

balance law hag now been put on hold for two

years. A fast-track zoning appeals process de-

signed to facilitate affordable housing was nar-

rowed in the past session of the Legislature.

Affirmative action is under attack.

This is no time to backtrack on civil rights.

Sheff II would keep the critical issue of housing

diversity on the front burner.

[dood

07/05/95 13:01

T203 241 76686 U OF CT LAW SCHL

Pump House Gallery

hey came, Lhey saw, they

WOre pum

Tt was the 10th anniversary

of Lhe Pump House Gallery, the

owned art gallery in Bushnell

and about 100 people came to cele-

brate Thursday night.

It was a crystal-clear night, with

jazz, plenty of wine, and big cocktail

shrimp while they ivi B oy

They're a 2 {

pe who oe the arte and

love the A d they appreciate

Pa alle y they Ja they

ve t to i

The dl igh dg! when

United Technologies Corp, award.

td a grant of $100,000 to the pus

nell Park Foundation. It nade ca

tal improvements and then h d

it over to the city to run.

“This gallery is a ugh urban

gallery, the lilecs of which we don't

see in other cities,” said Tony Bre-

scia, Pump House board member.

“Cities don't typically own art

ene.

“We have almost lost it.” he said.

“As soon as the budget is discussed,

the gallery is [endangered]. We've

done fund-raising in recent years ro

add money tn what the yay ys."

Earlicr in the day, Hartford poet

Lonnie Black had just read his poel-

ry in the Pump House co .He

was backed up by African

“Hey, Lonuie, did you see The

Advocate today?” asked Judy

Green, director of the ArtWorks

Gallery. "Tt said you were the major

force behind Northeast magazine, It

#7 J are it, baby. May I touch

What would Northeast Editor

Lary Rloom say ahout that?

Brescia, who is also senior re:

glonal manager for the Hartford re-

gion of the state Department of Eco-

nomic Developmenl, was

conunenting on the di of

ple wha were at the gallery party.

Black responicdled that iA wighed

there were morc.

"Geez, Lonnie, give it a rest.

We've got everything but Klin-

gong," Brescia paid. “Take tha

whole diversity less seriously und

write more limericks,”

Vivisn Zoe, director of the Lutz

Children’s Museum in Manchester,

was once a director of lhe Pump

House and said that the gallery “has

been in jeopas every year,

“People art is a fill, al-

though the city and state are g getting

beyond that,” she said, “It hos the

potential to attract people to the

au

oy tion Councilwoman Varomi.

ca Airey-Wilson was there — May-

or Mika was on vacation in SL

Maarten — and she intends to pro-

mata the gallery.

Phnom lunch functions have

acked,” she said, 1) says that

igen who work downtown utilize

it. R: There ought to be events here

several times a week."

Ajrey=Wilson said she plans to

tall to the department of parks nnd

recreation about getting more

groups to use it for fund-raisers.

Ag for the upcoming council race,

5 Sourani,

“Wilson, a Republican, 150

jus er party is “taking a wait-and-

see amirude and letting the Demo-

cratx fight it out.

“The Democrats are falling all

over each other, su many wanting to

run,” she said. “I'm impressed.”

As for whe may challenge the

wiayor, Airey-Wilson said: “I'll be

rE best Mike. He's brottght up

the energy level in the B= The

Republicans will

ra were there to suppo gallery

and to spread the good word on

Keney Park, specifically irs 10th an

pd and Family Day, Aug. 10

Se ya a show people huw

beautiful io Nise said

“A lptof Aid kh of Weaver High

School have such fond memories.”

She tokl how as a boy, Hartford

lawyer Gerry Roisman went to the

Keney Park stable with a friend and

Took TWO Bama which they rode

through the park.

“And on Sunday afternoons, it

had the best J ickup basketball

games,” she said. "We want to bring

people back to that memory.”

Christie, who is vents coording-

profess wy musics ofthe

‘Friends of Rant Park, was galling

pins prumoling Keney, He also had

kind words about the Pump House

Gallery.

“Art is what Hartford is made of,”

he said, “This is an experience peo-

ple ghould try ta have. [ think the

Pump House needs to be marketed

mare. Ld

Christie said that instead of trying

to get suburbanites to come into the

city, “the community frst has to

embrace it."

“No one talks about the people

here,” he said, "Let them take

ownership, 5

» He would like to see the Pump

yi Est i yous people and

Hhars m 5 my gut i! feeling,” he said.

“They do a better job when they're

volved.”

: Varsha — a satya) wurke!

as gtate Department of Men

LIsalth, lives in Windsor and is an

&Vid Supporter of te city.

“People from the suburbs think

Lhat entertainment i= going to the

"Enfield mall * Mason said. I

tel) them what [ go to in the city —

much less that Tlet my children take

the bus here — they look at me like

I'm half out of my gourd.”

Mason works with the Windsor

Youth Theater and plans to bring

members of that group into Hart-

ford this summer for Shakespeare

in the park

She plans to wear a pre-Raphael-

ite costume, put some niedieval cov-

€r an a cahbla, lemonade and

biscuits and put on a tea party.

Jeff Stewart, economic develops’

ment agent at the state Depaiimnbhe

of Tranzportation, described Rus

nell Park as Sion, Sonera Rast

of Harford." He noted that it was

designed by Frederick Law Olm-

stead, who is from Hartford and

who designed many famous parks

including New York's Central {Park

and Boston's park a, known

as the Emerald Ne

Two weeks ago, ot and oth-

er park advocates like Sandy Par-

isky started a group called the Hart-

ford Olmstead Park Alliance. He

marks milestone

TY he Jus ihe get) + wh

suid that Olmstead is buried in Hart-

ford,

“Yeah, he's buried in Carrie Sax-

on Perry's hat,” Brescia qui

Actually, Stewart said, Olmstead

ix butied in the old north cemetery

on Main Srreer, the alliance

ng friends ph the gallery

hat he has _— interne working

for him ul ecunumiv fevelopment

ou ae TE BY to contact Bette

Midler to see if she's interested in

sponsoring it," he said. “She loved

Sophie Tucker most.”

Brescia came v with tha ides

when he was ul QVC vendor

show, the air co! was Off,

and he said ha “was crazed.”

“The interns asked, ‘What do we

do next?” he =aid. “And I said:

Sophie"

Parisky thinks the tributes to

Olmstead and Tucker are long

av

“Hartford often neglects its

own," he said, “Often, people don’t

get discovered until they move

“Laiishy Is viee president of 3 president uf tie

Parisky 1 a Hariford public

policy on firm, He is also a

atfous] udviser For the National

de Seale that the failure

Jeni 8 could nut be blamed on

segregated schools, Poverty was the

cause,

“The Jade alg | that poor kids

cannot a good edics-

tion," B AME “Twill build in a

or: $e sw

bs Dead hen I sir

nell Park, I sé8 the multiracial, il

tiethnic, multi-income S poopie Bit-

afl

time, that's Sh Ba having.

sodiety.”

nity all on the i, was

ati gall is loging its

vonne Wars. She is leaving vol.

.y, but after wat she da-

thers were too many g

votes. Said aan “] knew I

couldn't work with them.

“They said I'm a militant snd

have a with ‘white malcs,”

she "Harris will sll be workin

in cultural affair in the parks an

recreation departmeit.

Palvicia Seremet 1s a business writer

Jor The Courant,

doos

07/05/95 13:02 ©'203 241 76686 U OF CT LAW SCHL : 008

H ap 1 Lord Ueur ant

ER

Education:

Does it lift

the poor?

Sheff findings challenge

belief in schools’ impact:

By ROBERT A. FRAHM A

Courant Staff Writer

For America’s poor, its immigrants, its

downtrodden, public schools always have

seemed a ticket out of pavers.

But a Connecticut judge challenged that

pular belief last week when he outlined

#5 findings in a landmark school desegre-

gation cage known as Sheff vs, O'Neill

Judge Harry Hammer said that because of

the stubborn effects of poverty, the children

in ‘Hartford's troubled public schools —

where academic performance is the worst in

the state — are doing about as well as can be

expected. ;

The judge, elaborating on a ruling he

issued two months ago, said there are no

educational strategies that can fully ovér-

come problems such as hunger, drug abuse

or parental neglect and that court-ordered

desegregation could produce more harm

than good.

Hammer, a Superior Court Jude from

Vernon, found, in effect, that children fail

not hecause they attend unequal or segre-

gated schools, but because they are poor.

His interpretation not only outraged

plaintiffs, it struck a nerve among some

educators.

“It's about as strikingly negative a set of

findings as I have ever seen in school deseg-

regation,” said Harvard University Profes-

sor Gary Orfield, who was a witness for the

plaintifts.

"Eddie Davis, superintendent of Hartford's

24,000-student system, said; “We have al-

ways believed education could bring you

out of poverty, If we ever lose that as'a

fundamental bellef, we will never change

anything in this country.”

Most students in Hartford public schools

are black or Hispanic, and many are poor. In

Connecticut and across the nation, test re-

sults show a close correlation with family

income. Usually, the lower the income, the

lower the score. :

The judge’s findings rekindled a debate

that has been simmering for years in aca-

demic circles and even among teachers in

Hartford’s own classrooms. The debate

dates at least from 1966, when sociologist

James 5S. Coleman issued a controversial

national study saying that a child's home

background has a greater effect on achieve-

meni than the quality of his school.

07/05/95 13:02 T203 241 7666

Sheff findings ch

vy

‘Continued from Page 1

~.It i§ possibly the most vexing

' question in American education to-

ga Can schools overcome the ¢rip-

pling effects of poverty?

Hammer's bleak answer to that

question came as a serious blow to

plaintiffs, who have ed that

only a court desegregation order

can reduce the disparity between

schools in Hartford and those in its

Jowre affluent, mostly white sub-

BFbs.

Civil .rights advocates found

Hammer's findings discouraging,

jugt as they did recent U.S. Supreme

Court rulings attacking school de-

Yégregation in Kansas City, Mo., af-

ffffative action and racially drawn

voting districts, said Theodore M.

"Sithw, associate" director of the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which

Aas provided counsel in the Sheff

e.

“The troubling thing about where

.are in the Sheff case,” he said,

“is that it comes in the broader con-

text of a national failure of will to do

anything . . . about the problems of

race and poverty."

The right facts

The case, now under review by

the state Supreme Court, has been

watched closely nationwide and

could alter the shape of Connecti-

cut’s cily and suburban school

boundaries.

Some of the key testimony on

which Hammer based his findings

came from David J. Armor, a re-

searcher who says it is poverty, not

racial segregation, that is the root of

the achievement gap.

“I'm pleased [the judge] sees the

facts the way I do,” said Armor, a

professor at George Mason Univer-

sity in Virginia and a well-known

critic of court-ordercd desegrega-

tion.

Armor, who once was elected to

the Los Angeles school board on an

anti-busing platform and held gov-

ernment research jobs as an ap-

pointee of President Reagan, esti-

mates he has testified in at least 30

school desegregation cases.

Armor contends that many courts

have issued desegregation orders

on the theory “that school segrega-

tion of any type causes harm to

minority children, especially black

children [and] harms their self-es-

teem, their educational processes.”

That theory, he said, is wrong,

“The thesis in the Sheff case is

that any segregation — even if it

comes by private choices of individ-

uals in housing patterns -- also pro-

duces the same harm. . .. There is

absolutely no evidence for that.”

As for the cause of poor achieve-

ment, he said, “we come back to

poverty, cducational differences

and other family differences,” in-

cluding child-rearing practices. The

achievement gap already exists by

the time a child reaches kinder-

garten, he said.

Armor's views, however, are at

odds with those of a number of ex-

perts who testified on behalf of the

plaintiffs. Among them is Otfield,

U OF CT LAW SCHL

the Harvard professor who has writ-

ten numerous reports on desegre-

gation,

Most research, Orfield said,

rally, on average, there

Although Armor and others have

said that court o cause whites

to flee from schoo icts, Orfield

disagrees.

He concedes there is some white

flight under mandalury busing

plans but says

est city-subur

also

some of the larg-

ordered

search methods

conclusions.

“He tends to look at effects and

gay they're too small to count. Oth-

ers look at it and say they're big,”

Orfield said. “That's what the de-

bate is like."

urin fhe tal in 1993, ale

t “preposterous an

deeply offensive” to s that

public education has ad sot on a

[@ooT

07/05/95 13:03

ing most of the arguments made by

Orfield and others on behalf of the

plaintiffs.

Education as a vehicle

Among his findings, Hammer

cites a 1990 report by a state com-

mission, which said schools alone

cannot fully overcome problems

such as drug abuse, hunger, poor

housing or unemployment.

‘That report, however, should not

be interpretéd to suggest that

schools have no role to play in ad-

dressing poverty, said David G.

Carter, president of Eastern Con-

necticut State University and the

ep ghainaan of the Sanson,

which was appomted by former

Gov. William A. O'Neill.

“If we have learned

from Brown vs. Board of Education,

it is that education provides a vehi-

cle for individuals to move beyond

where they are,” Carter said, refer-

ring to the 1954 U.S, Supreme Court

ruling that struck down state-sanc-

tioned school tion.

According to studies done by the

U.S. rmment, the achievement

gap between black and white stu-

dents narrowed somewhat during

the 1970s and 1980s. In part, that

may be the result of more maney

and effort targeted loward poor

children, some experts believe,

Although poverty remains a

strong influence on achievement,

“there are a number of examples of

schools that have been successful in

helping [poor] children reach stan-

dards meny have assumed poor

T203 241 76686 U OF CT LAW SCHL

THE HARTFORD COURANT: Tuesday, July 4, 195 AD

in schools’ effect 0

children are not capable of meet-

ing," said Thomas W. Payzant, as-

sistant secretary for elementary and

secondary education with the U.S.

Department of Education.

“The problem is, they are here

and there and few in number,” he

said.

Payzant said, however, there is

compe evidence to suggest that

poor children are likely to perform

better in middle-class schools than

in mostly low-income schools.

The damaging effect of high con-

centrations of poor children in

_ schools is a central argument in the

Sheff case, and it is acknowledged

7 Hammer in one of his findings.

gvertheless, (he judge agreed with

Armor and other witnesses who

said that court-ordered desegrega-

tion does not work.

That view is also held by Diane

Ravitch, a former U.S. assistant gec-

of education in the Bush ad-

ministration. If suburban parents

were asked to send their children to

city schools they perceived as infe-

rior, “they would all leave the public

school system and go to private

schools,” she said.

The only school system that has

significantly closed the achieve-

ment gap between students of dif-

ferent races and social classes is the

Catholic school system, said Ra-

vitch, now a researcher at New York

University. In that system, she said,

adults, including parents, create

schools with specific expectations,

rules of behavior and academic

standards for all students. :

But, she said, “I can’t think of a

strategy a court could order that

would make public schools operate

like Catholic schools.”

Ap ruled this year that the

state has no obligation to integra

schools. He issued last week's find-

ings at the request of the state Su-

preme Court. The high court is ex-

pected to hear arguments in the fall.

The plaintiffs will try to counter

Hammer by ing that many of

his findings are Conflicting Or erTd-

neous. or

For example, Hammer's fin :

Artord are ac

finding showing that Hartford

spenss much less than the state av-

erage on oks, lib books

and equipment, said John C. Brit-

tain, a lawyer for the plaintiffs.

Even Attorney General Richar

Blumenthal, who ig defending th

findings, conceds

tent problems o

worrisome.

“There is absolutely no question

the state needs to do more to imn-

prove the quality and diversity o

education,” he said last week.

“There is nothing in these find-

ings that minimizes that moral apd

social obligation. It Shun says the

ation.”

FX]

city chools are

stale has met its legal o

S.C. 15255

‘MILO SHEFF, et al. SUPREME COURT

Plaintiffs

v. | STATE OF CONNECTICUT

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.

Defendants JUNE 6, 1995

PLAINTIFFS’ AND DEFENDANTS’

REVISED STIPULATIONS OF FACT!

1 Tne parties are in agreement with all stipulations (1-256)

contained herein. The parties are also in agreement with headings

I and VI. Because the parties were unable to agree as to headings

II-V, each side has submitted in this document its own proposed

heading for each respective section.

The parties are in agreement on all subheadings. The

subheadings correspond with the same subheadings in the parties’

proposed findings of fact.

Unless otherwise stated, all proposed stipulations are as of

the date of trial.

wile

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DESCRIPTION OF PARTIES (Stipulations 1-25)

PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DOES RACIAL AND ETHNIC ISOLATION IN THE HARTFORD

SCHOOL SYSTEM VIOLATE ARTICLE EIGHTH, SECTION 1 AND

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THE STATE HAS

VIOLATED THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSES, THE DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE OR THE EDUCATION ARTICLE OF THE STATE

A. THE CURRENT DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENTS BY RACE

AND ETHNICITY (Stipulations 26-38)

TRENDS IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENTS BY RACE

AND ETHNICITY (Stipulations 39-62)

PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DO THE INADEQUACIES OF THE HARTFORD SCHOOL SYSTEM

DENY PLAINTIFFS A MINIMALLY ADEQUATE EDUCATION UNDER

ARTICLE EIGHTH, SECTION 1 AND ARTICLE FIRST,

SECTIONS 1 AND 20? (Stipulations 63-112)

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THEY HAVE BEEN

DENIED THEIR RIGHTS TO A FREE PUBLIC EDUCATION

UNDER THE EDUCATION ARTICLE OF THE STATE

CONSTITUTION? (Stipulations 63-112)

PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DOES THE RACIAL, ETHNIC, AND ECONOMIC ISOLATION

AND POVERTY CONCENTRATION COUPLED WITH DISPARITIES

IN RESOURCES AND OUTCOMES VIOLATE PLAINTIFFS’ RIGHT

TO EQUAL EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES UNDER ARTICLE

EIGHTH, SECTION 1 AND ARTICLE FIRST, SECTIONS 1 AND

207 vein sebswessesens

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THE STATE HAS

VIOLATED THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSES, THE DUE

PROCESS CLAUSE OR THE EDUCATION ARTICLE OF THE STATE

VI.

- 3%

A. STUDENTS’ SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS IN HARTFORD

METROPOLITAN AREA SCHOOLS (Stipulations 113-

ER A TERR ER EINER VR ISR STU She TO NI ESS Ea

Ce INTEGRATION AND ITS EFFECTS (Stipulations

UR TR TE RE WRG PR PE CMa ioe SE

FP. DISPARITIES IN EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES

(SEIDUIALIONS 154-202) cits nina vianvoneseonsnsesse

PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

HAS THE STATE BEEN INVOLVED IN MAINTAINING RACIAL,

ETHNIC, ECONOMIC SEGREGATION UNEQUAL EDUCATIONAL

OPPORTUNITIES, AND LACK OF A MINIMALLY ADEQUATE

EDUCATION, DOES THE STATE HAVE AN AFFIRMATIVE DUTY

TO ADDRESS SUCH ISSUES AND HAS THE STATE FAILED TO

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAS THE STATE BEEN TAKING APPROPRIATE ACTION TO

ADDRESS RACIAL, ETHIC, AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC ISOLATION

AND EDUCATIONAL UNDERACHIEVEMENT OF URBAN CHILDREN

A. STATE INVOLVEMENT IN EDUCATION HISTORICALLY

(SLIpUIatIons 203-220) vviiviviesersnseenisaseens

B. STATE INVOLVEMENT IN EDUCATION TODAY

(SripR1ALIOoNS 220-251). sect nind onan ssine sin

STEPS TOWARD INTEGRATION (Stipulations 252-256).....

13

16

17

28

28

30

30

34

DESCRIPTION OF PARTIES

l. Plaintiff Milo Sheff is a fourteen-year old black child.

He resides in the city of Hartford with his mother, Elizabeth Sheff,

who brings this action as his next friend. He is enrolled in the

eighth grade at Quirk Middle School.

2. Plaintiff Wildalize Bermudez is a ten-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She reside in the City of Hartford with her parents,

Pedro and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is enrolled in the fifth grade at Kennelly School.

3. Plaintiff Pedro Bermudez is an eight-year-old Puerto

Rican child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents,

Pedro and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as his next

friend. He is enrolled in the third grade at Kennelly School.

4. Plaintiff Eva Bermudez is a six-year-old Puerto Rican

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents,

Pedro and Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is enrolled in kindergarten at Kennelly School.

5. Plaintiff Oskar M. Melendez is a ten-year-old Puerto

Rican child. He resides in the Town of Glastonbury with his

parents, Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as his next

friend. He is enrolled in the fifth grade at Naubuc School.

6. Plaintiff Waleska Melendez is a fourteen-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She resides in the Town of Glastonbury with her

parents Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is a freshman at Glastonbury High School.

7 Plaintiff Martin Hamilton is a thirteen-year-old black

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his mother, Virginia

Pertillar, who brings this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School.

8. Plaintiff Janelle Hughley is a 2 year-old black child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Jewell Hughley,

who brings this action as her next friend.

9. Plaintiff Neiima Best is a fifteen-year old black child.

. She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Denise Best,

who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled as a

sophomore at Northwest Catholic High School in West Hartford.

10. Plaintiff Lisa Laboy is an eleven-year-old Puerto Rican

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Adria

Laboy, who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled

in the fifth grade at Burr School.

11. Plaintiff David William Harrington is a thirteen-year-old

white child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents

Karen and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend.

‘He is enrolled in the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School.

12. Plaintiff Michael Joseph Harrington is a ten-year-old

white child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents

Karen and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next friend.

He is enrolled in the fifth grade at Noah Webster Elementary School.

13. Plaintiff Rachel Leach is a ten-year-old white child.

She resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents Eugene

Leach and Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as her next

friend. She is enrolled in the fifth grade at Whiting Lane School.

14. Plaintiff Joseph Leach is a nine-year-old white child.

He resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents Eugene

Leach and Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as his next

friend. He is enrolled in the third grade at Whiting Lane School.

15. Plaintiff Erica Connolly is a nine-year-old white child.

She resides in the City Hartford with her parents Carol Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the fourth grade at Dwight School.

16. Plaintiff Tasha Connolly is a six-year-old white child.

She resides in the City Hartford with her parents Carol Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the first grade at Dwight School.

17. Michael Perez is a fifteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. He

resides in the City Hartford with his father, Danny Perez, who bring

this action as his next friend. He is enrolled as a sophomore at

Hartford Public High School.

18. Dawn Perez is a thirteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. She

resides in the City Hartford with her father, Danny Perez, who bring

this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in the eighth grade

at Quirk Middle School.

18. Among the plaintiffs are five black children, seven

Puerto Rican children and six white children. At least one of the

children lives in families whose income falls below the official

poverty line; five are limited English proficient; six live in

single-parent families.

20. Defendant William O’Neill or his successor is the

Governor of the State of Connecticut.

21. Defendant State Board of Education of the State of

Connecticut (hereafter "the State Board" or the State Board of

Education") is charged with the overall supervision and control

of the educational interest of the State, including elementary and

‘secondary education, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4.

22. Defendants Abraham Glassman, A. Walter Esdaile, Warren

J. Foley, Rita Hendel, John Mannix, and Julia Rankin were, at one

time, the members of the State Board of Education and these

individuals have been succeeded by others as members of the State

Board of Education.

23, Defendant Gerald N. Tirozzi or his successor is the

Commissioner of Education for the State of Connecticut.

24. Defendant Francis L. Borges or his successor is the

Treasurer of the State of Connecticut.

25: Defendant J. Edward Caldwell or his successor is the

Comptroller of the State of Connecticut.

II. PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DOES RACIAL AND ETHNIC ISOLATION IN THE HARTFORD SCHOOL SYSTEM

VIOLATE ARTICLE EIGHTH, SECTION 1 AND ARTICLE FIRST, SECTIONS

1 AND 207?

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THE STATE HAS VIOLATED THE

EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSES, THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OR THE

EDUCATION ARTICLE OF THE STATE CONSTITUTION?

A. THE CURRENT DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENTS BY RACE AND

ETHNICITY

26. Ninety-two percent of the students in the Hartford schools

are members of minority groups. (Tables 1 and 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at

31, 38; Natriello p. B82; Pls’ Ex. 85 p. vii)

27. African Americans and Latinos together constitute more

than 90%, or 23,283, of the 25,716 students in the Hartford public

schools (Pls’ Ex. 219 at 2).

28. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 21.6 will

be members of minority groups. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

29. Hartford has the highest percentage of minority students

in the state. (Natriello p. 82; Table 1, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 31)

30. In 1991-92, fourteen of Hartford's twenty-five elementary

schools had less than 2% white enrollment. (Defs’ Exs. 23.1-23.25)

31. As of 1990, eighteen of the surrounding suburbs had less

‘than 10% minority population, ten of the surrounding suburbs have

less than 5% minority population, 18 out of the 21 suburbs have less

than 4% Black population, and 12 towns have less than 2% Black

population. (Pls’ Ex. 137 at 1, 7; Pls’ Bx. 138; Steahr pp. 99-101)

32. In 1991, sixteen suburbs had less than 3% Latino

enrollment. (Pls’ Ex. 85 pp. 18-21)

33. Some of Conmnecticut’s school districts, including

Hartford, serve higher percentages of African American and Latino

students than others.

34. In 1986, 12.1% of Connecticut’s school age population was

black and 8.5% was Hispanic.

35. 1987-88 figures for total school population and percent

minority for the towns listed below are:

Total School Pop.% Minority

Hartford 20,058 90.5

Bloomfield 2.555 69.0

Avon 2,068 3.8

Canton 1,189 3.2

East Granby 666 2.3

East Hartford 5,905 20.6

East Windsor 1,267 8.5

Ellington 1,855 2.3

Farmington 2,608 Pe?

Glastonbury 4,463 5.4

Granby 1,528 3.5

Manchester 7,084 it.1

Newington 3,801 6.4

Rocky Hill 1,807 5.9

Simsbury 4,039 6.5

South Windsor 3,648 9.3

Suffield 1,772 4.0

Vernon 4,457 6.4

West Hartford 7,424 15.7

Wethersfield 2:997 3.3

Windsor 4,235 30.8

Windsor Locks 1,642 4.0

36. As of 1991-92, two districts, Hartford and Bloomfield, had

more than five percent African Americans and Latinos on their

professional staffs. (Defs’ Exs. 14.1-14.22)

37. As of 1990, fourteen of the state’s 166 school districts

are home to 30 percent of the state’s total student population, 77

percent of the minority student population and 81 percent of the

children receiving AFDC benefits. (Pls’ Ex. 77 at 8)

38. In 1992, there were seven suburban school districts with

a minority enrollment in excess of 10%, namely:

%$ minority enrollment %_increase between 1980 & 1990

l. Bloomfield 83.5% 32.4%

2. East Hartford 38.1% 27.3%

3. Windsor 36.9% 15.7%

4. Manchester 19% 12.8%

5. West Hartford 17.2% 10.7%

6. Vernon 11.6% 7.8%

7. East Windsor 10.3% 4.1%

(Calvert pp. 33-35; Defs’ Ex. 2.6 Rev., 2.7 Rev.).

B. TRENDS IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF STUDENTS BY RACE AND

ETHNICITY

39. In 1963, 36.3% of the students in the Hartford public

schools were African-American. (Pls’ Ex. 19, p. 30 (Table 4.1.14))

40. In 1992, African-American students in the Hartford public

schools made up 43.1% of the total student population, an increase

of 6.8% from 1963. (Defs’ Ex. 2.6 and 2.12))

41. In 1963, there were 599 Latino students in the Hartford

public schools. (Pls’ Ex. 19, p. 30 (Table 4.1.14)

42. By 1992, there were 12,564 Latino students in the

Hartford public schools -- an increase of 1,997.5%. (Defs’ Ex. 2.15)

43. From 1963 to 1992, the African-American student population

in the Hartford public schools increased from 9,061 to 11,201, an

increase over that period of 23.6%. (Defs’ Ex. 2.12)

44. From 1980 to 1992, the African-American student population

in the Hartford public schools decreased from 12,393: t0.11,201, a

decrease of 9.6% over that period. (Defs’ Ex. 2.12)

45. According to a 1965 study commissioned by the Hartford

Board of Education and the Hartford City Council and prepared by

consultants affiliated with the Harvard School of Education (the

"Harvard Study"), the rapid increase of non-white student population

in Hartford in the 1950’s and early 1960's would not continue.

(Defs’ Ex. 13.2, p. 2; Defs’ Rev. Answer 152)

46. The Harvard Study correctly projected the decline in

Hartford's African-American student population, the only significant

minority group in Hartford in 1965, but failed to predict the

massive influx of Latino students, primarily of Puerto Rican

ancestry. (Defs’ Ex. 13.2, p. 2; Gordon pp. 98-99)

47. From 1980 to 1992, African-American student population in

the 21 suburban towns increased by 62.5% from 3,925 to 6,380. (Defs’

Bx.:2.12)

48. During the 1980s, Hartford experienced the greatest out

migration of white residents, with a net out migration of 18,176.

(Defs’ Bx. 1.3)

49. During the 1980s, Hartford experienced the largest

increase of the non-white population -- an increase of 21,499

persons -- of all the towns in the Hartford metropolitan area.

{Defs’ Ex. 1.3)

50. According to a study prepared for the Governor's

Commission between 1985 and 1990, there was a "significant increase

in the percentage of minority students in the five major

metropolitan areas studied: Bridgeport, New Haven,

Bloomfield/Hartford, Norwalk/Stamford, New London, and the towns

nearby." (Pls’' Ex. 73 at 4)

51. In 1991, the State Board of Education predicted that

enrollment of minority students is projected to increase from 24.3

percent in 1989 to 30.9 percent of the public school population by

2005. Hispanic students are expected to be the predominant minority

group (13.7 percent of the total school enrollment) by 2004. (Pls’

Ex, 77: at. 7)

52. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 138, based on U.S. Census data, is an

accurate summary of African-American population in Hartford and

surrounding towns, from 1940 to 1990.

53. At the start of this century, the African-American

population was approximately 3% of the state’s total population and

remained at or below that level for the first half of this century.

(Steahr pp. 78-79)

54. By 1940, African-Americans had declined to 1.2% of the

state’s population. (Collier p. 41; Steahr pp. 78-80.)

55. The greatest percentage increase in Hartford’s African-

American population was between 1950-1960. (Steahr p. 79)

56. There was no significant Latino population of primarily

Puerto Rican ancestry in Connecticut until the late 1960's. (Morales

pp. 29-30)

57. Since 1970, the African-American population has been

increasing in many towns around Hartford, particularly in

Bloomfield, Manchester, Windsor and West Hartford. (Steahr p. 38)

58. Each town in the 21 town area surrounding Hartford, as

described by the plaintiffs in their amended complaint has

experienced an increase in non-white population since 1980. (Steahr

Pp. 29)

59. Since 1980, total student enrollment in the combined 21

suburban school districts has declined. (Defs’ Ex. 2.4)

60. In Hartford, there has been a numerical increase in the

African-American population, which is due to an increase in births

over deaths and not to in-migration. (Steahr p. 61)

51. State officials have, for some time, been aware of a

trend by which the percentage of Latino students in the Hartford

public schools has been increasing while the percentage of white and

African American students has been decreasing. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 50)

62. In 1969, the General Assembly passed a Racial Imbalance

Law, requiring racial balance within, but not between, school

districts. Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-226a et seq. The General

Assembly authorized the State Department of Education to promulgate

implementing regulations. Conn. Gen. Stat. §10-226e. The General

Assembly approved regulations to implement the statute in 1980.

III. PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DO THE INADEQUACIES OF THE HARTFORD SCHOOL SYSTEM DENY

PLAINTIFFS A MINIMALLY ADEQUATE EDUCATION UNDER ARTICLE EIGHTH,

SECTION 1 AND ARTICLE FIRST, SECTIONS 1 AND 20? (Stipulations

63-112)

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THEY HAVE BEEN DENIED THEIR

RIGHTS TO A FREE PUBLIC EDUCATION UNDER THE EDUCATION ARTICLE

OF THE STATE CONSTITUTION? (Stipulations 63-112)

63. The purpose and effect of the state’s principal formula

for distributing state aid to local school districts (the Education

Cost Sharing formula ("ECS") embodied in Conn. Gen. Stat. §§10-

262f, 10-262g, 10-262h) is to provide the most state aid to the

neediest school districts. (Brewer pp. 37, 85, 157-162; Defs’ Ex.

+1, DPD. t36=78; 7.2), p. 83A; 7.18, 7.19::7.20)

64. Under the ECS formula, the Hartford public schools

received for the 1990-91 school year $3,497-per pupil in state

funds; the average per pupil grant to the 21 suburban school

districts was only $1,392 in state funds. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-83A)

65. Under the ECS formula, the Hartford public schools

received for the 1991-92 school year $3,804 per pupil in state

funds; the average per pupil grant to the 21 suburban school

districts was only $1,321 in state funds. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-83A)

66. The increase 1in state aid to Hartford under the ECS

formula from 1990-91 to 1991-92 was $307 per pupil; the decrease in

the average ECS formula grant to the 21 suburban school districts

from 1990-91 to 1991-92 was $71 per pupil. (Brewer p. 85; Defs’ Ex.

7.21, pp. 83-83A)

67. In terms of total state aid for the 1990-91 school year

(the sum of all state education aid including the ECS formula aid),

Hartford received $4,514 per pupil; the average amount of total

state aid to the 21 suburban school districts was $1,878 per pupil.

{Brewer p. 37; Defs’ Ex. 7.21, pp. 11-113)

68. In terms of total state aid for the 1991-92 school year,

Hartford received $4,915 per pupil; the average amount of total

state aid to the 21 suburban school districts was $1,758 per pupil.

(Brewer .p.37; Defs’ Ex. 7.21, p. 11-113)

69. The increase in Hartford’s total state aid from 1990-91 to

1991-92 was $401 per pupil; the decrease in average total state aid

to the 21 suburban school districts was $120 per pupil (Brewer p.

37; Defs’ Ex. 7.21, pp. 11-11lA)

70. Hartford received 2.4 times as much total state aid per

pupil as the 21 suburban school districts in 1990-91 and 2.8 times

as much total state aid per pupil in 1851-92, (Defs’ Ex. 7.1, p.1l1;

Defs’ Bx. .7.21, Pp. 113)

71. In 1990-91, the Hartford school district received 57.6% of

its total funding from state aid and 60.49% thereof in 1991-92.

{Brewer p. 37; Defs’' Bx. 7.1, pp..11-11A)

72. In 1990-91, the 21 suburban school districts received an

average of 25.8% of their total funding from state aid and 23.99%

thereof in 1991-92. (Brewer p. 37; Defs’ Ex. 7.1, pp. 11-11A)

73. In 1990-91, overall per pupil expenditure in Hartford were

:$7,837 and $7,282 per pupil in the 21 combined suburban school

districts. (Defs’ Ex. 7.1, pp. 3A, 11)

74. In 1991-92, the overall per pupil expenditure in Hartford

was $8,126 compared to an average of $7,331 per pupil in the 21

combined suburbs. (Defs’ Bx. 7.1, pp. 34, 11)

75. Under the category of "net current expenditures per need

student," a calculation in which the Hartford public school student

count is increased by an artificial multiplier of one-quarter

student for each Hartford public school student on Aid to Families

with Dependent Children (AFDC) and by one-quarter student for each

Hartford public school student who in the preceding school year

tested below the remedial standard on the CMT, i.e., each AFDC

student and CMT remedial student is counted as 1.25 students and

each student who is both on AFDC and a CMT remedial student is

counted as 1.5 students, Hartford's per pupil spending for the 1990-

1991 school year was fifteenth among the school districts in the

twenty-two town area. (Natriello, Vol. 93-94; PX 163, pp. 158-162)

74. During the 1990-91 school year, the total professional

staff per 1,000 students was 89.4 in Hartford and 88.8 in the

combined 21 suburban school districts. (Defs’ Ex. 8.5)

17. During the 1991-92 school year, the total professional

staff per 1,000 students in Hartford was 86.5 and 85.1 in the 21

combined suburb school districts. (Defs’ Ex. 8.5)

78. In 1992, 88.5% of Hartford teachers had at least masters

degrees or their equivalents, i.e., bachelors degrees plus 30

graduate school credits. (Keaveny pp. 7-8, 12)

79. Hartford’s teacher-student ratio improved from the 1988-

1989 school year to 1989-1990 by 2.2 teachers per thousand students

while the suburban town’s combined increase was 0.9 teachers per

thousand students. (Natriello pp. 46-48)

80. During that period, the state’s overall teacher-student

ratio declined. (Pls’ Ex. 163, Table 5, Panel B, p. 56; Natriello

p. 54)

81. During the 1990-91 school year, Hartford had 77 classroom

teachers per 1,000 students and the 21 combined suburban school

districts had 75.9. (Defs’' Ex. 8.6)

82. Class sizes in Hartford are comparable to class sizes in

the 21 suburban school districts and throughout the state. (Pls’

Ex. 163, Table 6, Panel B, p. 59; Defs’ Ex. 2.38; Calvert pp. 124-

125; Natriello pp. 56-57)

=10 =

83. The Hartford public schools have high quality classroom

teachers and administrators. (Pls’ Ex. 163 [table 4]; Keaveny p. 15;

LaFontaine p. 131; Wilson pp. 9, 28-29; Negron p. 7; Pitocco p. 70;

Natriello p. 35)

84. Hartford teachers are dedicated to their work. (Haig pp.

113-114; Neumann-Johnson p. 18)

85. Hartford has 1.26% fewer general elementary teachers and

has 4% fewer contact specialist teachers than the statewide average,

and 6.1% more special education teachers than the statewide average.

{(Natriello at 103; Table 3, Pls’ Ex. 183 at 49)

86. In 1991, 94% of Hartford administrators had at least

thirty credits of education beyond their masters degrees. (Keaveny

Pp. 14)

87. Hartford teachers have been specially trained in

educational strategies designed to be effective with African-

American, Latino, inner city and poor children. (Haig p. 94;

LaFontaine p. 132; Wilson p. 10)

88. Hartford’s elementary schools have a curriculum that is

standardized from school to school designed to ameliorate the

effects of family mobility, which affects Hartford children to a

much greater extent than suburban children. (LaFontaine p. 162)

89. Hartford schools have some special programs for enhancing

the education of poor and urban children. (Haig p. 63; LaFontaine

pp. 134-135)

90. Hartford has an all-day kindergarten program in some of

its elementary schools for children who may be at risk of poor

educational performance. (Calvert pp. 10-13; Negron p. 68; Montanez-

Pitre pp. 34, 48; Cloud pp. 79, 88, 113)

91. Hartford has a school breakfast program in each of its

elementary schools. (Senteio p. 50; Negron p. 66; Montanez-Pitre p.

4-2; Morris p. 158; Neumann-Johnson p. 24)

92. Hartford offers eligible needy students in all its schools

a free and reduced-price lunch program. (Senteio p. 22)

93. Hartford’s school breakfast and school lunch programs are

paid for entirely by state and federal funds. (Senteio p. 22)

94. The Hartford school district has several special programs

such as the Classical Magnet program, which the first named

plaintiff attends, and the West Indian Student Reception Center at

Weaver High School. (E. Sheff p. 194; Pitocco pp. 88-89)

<ll.-

95. The number of Spanish-dominant children eligible for

‘bilingual education in Hartford from 1985 to 1990 has been as

follows:

1985-86 4,225

1986-87 4,517

1987-88 4,622

1988-89 4,773

1989-90 4.696

(Defs’ Ex. 12.26 at 2)

96. In 1990-91 school year, Hartford’s bilingual education

program served approximately 6,000 students per year. (Marichal p.

11)

97. 92% of the students served by Hartford’s bilingual

education program in 1990-91 were Hispanic. (Defs’ Ex. 13.6 at 5)

98. In 1988-89 school year, 42.5% of the state’s bilingual

education students were in Hartford. (Defs’ Ex. 12.24 at 5)

99. In 1989-90, Connecticut’s bilingual education programs

served 12,795 students, a 5.1% increase over 1988-89; 94% of the

program participants were dominant in Spanish. (Defs’ Ex. 13.6 at

>)

100. Hartford's school buildings do not meet some requirements

regarding handicapped accessibility, but no buildings are in

violation of health, safety, or fire codes. (Senteio p. 44)

101. Eight of Hartford’s 31 school buildings were found in a

space utilization study to require "significant attention." (Pls’

Ex. 153 pp. 5-10 -~ 5-11)

102. Hartford's reimbursement rate for school building or

renovation projects has been considerably higher than the

reimbursement rate for the 21 suburban districts. (Defs’ Ex. 7.21

pp. 3A-3D; Defs’ Ex. 12.27; Lemega p. 18)

103. In 1992, Hartford voters approved the issuance of

$204,000,000 in bonds for school building expansion and improvement.

{Senteioc p. 37)

104. Under 1991-92 state reimbursement rates, the state will

reimburse Hartford for more than 70% of the cost of its school

building expansion and improvement project. (Defs’ Ex. 7.21, p. 3A)

105. From the 1989-90 school year to the 1990-91 school year,

the Hartford Board of Education increased its per pupil expenditures

-3

for library books by 2.67 times and its library books per school

building by 2.73 times." (Defs’ Bx. 7.12)

106. From 1980 to 1992, Hartford spent approximately $2,000

less per pupil on (a) pupil and instructional services, (b)

textbooks and instructional supplies, (c¢) library books and

periodicals, and (d) equipment and plant operations than the state

average for these items. (Defs’ Ex. 7.9; Brewer p. 142)

107. From 1980 to 1992, the Hartford school district paid its

employees $2,361 more per pupil in employee benefits than the state

average. (Defs’ Ex. 7.9; Brewer p. 143)

108. From 1988-91, Hartford spent $240 more per pupil than New

Haven and $300 more per pupil than Bridgeport on employee fringe

benefits. (Brewer p. 143)

109. There has been no known independent study to determine

whether it has been necessary for the Hartford school district to

pay higher employee fringe benefits to attract and to retain

qualified teachers and administrators. (Natriello p. 63)

110. Resources are applied somewhat differently in the

Hartford public schools than in many of the 21 suburban school

districts because of the different needs of Hartford students.

(Pls’ Ex. 493; Ferrandino Deposition pp. 133-134)

111. Because of fiscal constraints, the West Hartford school

district has eliminated over the past three years its gifted and

talented students program, its foreign language program in its

elementary schools and its home economics program in its middle

schools. (Lemega pp. 13-15)

112. The West Hartford school district, which in 1992 received

6.7% of its financing from the state, had its state funding reduced

by 50% ($5,200,000) over the prior three years. (Lemega p. 11)

=13 -

IV. PLAINTIFFS’ HEADING:

DOES THE RACIAL AND ETHNIC AND ECONOMIC ISOLATION AND POVERTY

CONCENTRATION COUPLED WITH DISPARITIES IN RESOURCES AND

OUTCOMES VIOLATE PLAINTIFFS’ RIGHT TO EQUAL EDUCATIONAL

OPPORTUNITIES UNDER ARTICLE EIGHTH, SECTION 1 AND ARTICLE

FIRST, SECTIONS 1 AND 20?

DEFENDANTS’ HEADING:

HAVE THE PLAINTIFFS PROVEN THAT THE STATE HAS VIOLATED THE

EQUAL. PROTECTION CLAUSES, THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OR THE

EDUCATION ARTICLE OF THE STATE CONSTITUTION?

A. STUDENTS’ SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS IN HARTFORD METROPOLITAN

AREA SCHOOLS (Stipulations 113-149)

113. Sixty-three percent of the students in the Hartford

school system participate in the free and reduced lunch program.

(Pls’ Bx, 219; Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

114. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 14.8 will

be participating in the free and reduced lunch program. (Table 2,

Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

115, Thirteen percent of all children born in the city of

Hartford are at low birth weight, 13% are born to drug-addicted

mothers, and 23% are born to mothers who are teenagers. (Table. 2,

Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

116. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 3 will

have been born at a low birthweight, 3 will have been born to drug

addicted mothers, and 5.4 will have been born to teen mothers.

{Table 2, Pls’ Ex.:183 at 38)

117. 35.6 percent of the housing units in Hartford require the

occupants to spend 30% or more of their household income on housing

costs. {Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 263 at 33)

118. Forty percent of the children in Hartford are living with

parent(s) with no labor force participation. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163

at 38)

119. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 9.4 will

be from a family in which the parent(s) do not participate in the

labor force. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

120. More than sixty-four percent of the parents of Hartford

school age children with children under eighteen are single parent

households. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

«14d -

121. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 15.1 will

.come from single parent households. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

122. A single parent home is an indicator of a disadvantage

for students. (Natriello p. 71)

123. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 9.5 will

come from families where the parents have less than a high school

education... (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

124. Fifty-one percent of Hartford students are from a home in

which a language other than English is spoken. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex.

163 at 38)

125. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 12 will

come from a home in which a language other than English is spoken.

{Taple 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 318)

126. Students with limited English proficiency have more

difficulty succeeding in school. (Natriello p. 84)

127. Economic status of parents is a predictor of schooling

difficulty. (Natriello p. 653)

128. Fifteen percent of the Hartford population and 41.3% of

the parents with school age children have experienced crime within

the year. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at 38)

129. In an average Hartford class of 23.4 students, 3.6 will

have been a victim of crime and 9.7 will live in a household that

has experienced crime within the year. (Table 2, Pls’ Ex. 163 at

38)

130. Twenty-eight percent of Hartford elementary students do

not return to the same school the next year. (Natriello p. 78; Pls’

Ex. 183 at 27)

131. Hartford has the lowest stability rate (percentage of

students who return to the same school as the prior year) at the

elementary level in comparison to other districts. (Natriello II p.

6)

132. It is more difficult for students who come from a

community with a high crime rate to do well in school. (Natriello

pp. 85-86)

133. A high proportion of Hartford students live in housing

with high crime rates. (Morris p. 140; Griffin p. 84)

~15"~

134. Over thirty-five percent of the Hartford households

reside in dwellings which the United States Commerce Department

would characterize as inadequate housing. (Natriello p. 77; Pls’

Ex. 163 at 26)

135. Fifteen of the 21 surrounding districts have less than

10% of their students on the free and reduced lunch program. (Pls’

Ex. 163 p. 153)

136. Hartford's rate of poverty is greater than the rate among

students in any of the twenty-one surrounding districts. (Pls’ Ex.

163 at 152 and Figure 33, at 153; Rindone p. 121)

137. Hartford found itself last in comparison to the twenty-

one surrounding communities in 1980 on every single socio-economic

indicator, and it remained in last place ten years later in 1990.

{(Rindone p. 110; Defs’ Ex. 8.1.and 8.2)

138. The median family income of every suburb of the combined

suburban area, except East Hartford and Windsor Locks, has more than

doubled during that ten year period from 1980-1990 and the median

income of a Hartford family increased 42% during that period.

(Defs’ Pxs. 8.1 5 8.2)

139. The percentage of students in Hartford who live in homes

where a language other than English is spoken is higher than in any

surrounding community. (Figure 34 (as modified, see Natriello, p.

177), Pls’ Fx. 163 at 154)

140. Some of the indicia of "at risk" students include (i)

whether a child’s family receives benefits under the Federal Aid to

Families with Dependent Children program, (a measure closely

correlated with family poverty); (ii) whether a child has limited

english proficiency (hereafter "LEP"); or (iii) whether a child is

from a single-parent family. (Defs’ Revised Answer 137)

141. The Hartford Public Schools serve a greater proportion of

students from backgrounds that put them "at risk" of lower

educational achievement than the identified suburban towns and, as

a result, the Hartford Public Schools have a comparatively larger

burden to bear in addressing the needs of "at risk" students.

(Def’s Revised Answer 35)

142. "At risk" children have the capacity to learn and "at

risk" children may impose some special challenges to whichever

school system is responsible for providing these children with an

education.

S16 -

143. The negative impact of poverty on student achievement is

acknowledged and controlled for by social-scientists in their

studies on student achievement. (Crain pp. 102-103, Vol. 35, p. 76)

144. Social problems more common to students in Hartford than

to students in the suburbs, which have been shown to have a direct

negative impact on student development, are children with low

birthweight, children born to mothers on drugs, children born to

teenage mothers, children living in poverty, children from single

parent households, children with parents with limited formal

education, children living in substandard housing, children from

homes where little English is spoken, children exposed to crime and

children without an employed parent. (Pls’ Ex. #163, Table 2, p. 28)

145. When Hartford children who are afflicted by poverty enter

kindergarten, many of them are already delayed one and one-half to

two years in educational development. (LaFontaine p. 132; Cloud p.

86; Montanez-Pitre pp. 11, 41; Negron p. 81)

146. Socio-economic status (SES) encompasses many factors

relating to a student’s background and family influences that affect

a child’s orientation toward and skill in learning. (Armor I pp.

138-140; Armor II pp. 11-12)

147. The gap between the SES of children who live in Hartford

and the SES of children who live in the 21 suburbs has been

increasing. (Natriello, pp. 114-116; Defs’ Ex. 8.1, 8.2)

148. There are some differences between Hartford Public School

students taken as a whole and suburban students as a whole in some

of the surrounding communities in terms of the number who drop out

before graduation, who enter four year colleges and other programs

of higher education, and the number of others who obtain full-time

employment within nine months of graduation.

149. The drop out rate for Hartford schools is greater than

for Connecticut public schools in general. (Pls’ Ex. 163 at 142-

145)

C. INTEGRATION AND ITS EFFECTS (Stipulations 150-153)

150. Improved integration of children by race, ethnicity and

economic status is likely to have positive social benefits. (Defs'’

Revised Answer 49)

151. Integration in the schools is not likely to have a

negative effect on the students in those schools. (Defs’ Revised

Answer 149)

152. The defendants have recognized that society benefits from

‘racial, ethnic, and economic integration and that racial, ethnic,

and economic isolation has some harmful effects.

153. Poor and minority children have the potential to become

well-educated. (Defs’ Revised Answer 13)

F. DISPARITIES IN EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES

(Stipulations 154-204)

154. At the direction of the General Assembly, Connecticut has

developed a statewide testing program, the Connecticut Mastery Test

("CMT"), and a statewide system of school evaluation, the Strategic

School Profiles ("SSP"). (Rindone pp. 80-81; Nearine p. 65; Conn.

Gen. Stat. §10-14n and §10-220(c))

155. The present mastery testing system is better than the

previous one because it was created by Connecticut teachers based on

this state’s own educational goals. It was the consensus of the

state board of education that it is a valuable tool in judging the

outputs of the school system. (Mannix::5Pls’/. Bx.i495 p. 17;

Memorandum of Decision 46)

1556. After Vincent Ferrandino became Commissioner of the

Department of Education, as part of his reorganization of the

department, he established an office of urban and priority school

districts in order to concentrate the resources of the department on

the problems of the cities, and more specifically, to improve the

achievement of the students in the three largest urban districts.

(Ferrandino, Pls’ Ex. 493 p. 25; Memorandum of Decision 36-37)

157. The CMT was first administered in the fall of 1985. (Pls’

Ex. 290)

158. The State Board of Education has stated that the goals of

the CMT are:

a. earlier identification of students needing remedial

education;

b. continuous monitoring of students in grades 4, 6, and 8;

C. testing of a more comprehensive range of academic skills;

d. higher expectations and standards for student achievement;

e. more useful achievement data about students, schools, and

districts;

£. improved assessment of suitable equal educational

opportunities.

(Defs’ Ex. 12.13)

13 =

159. The CMT measures mathematics, reading and writing skills

in the 4th, 6th, and 8th grades. (Pls’ Ex. 290-309)

160. The CMT is one measure of student achievement in

Connecticut.

161. Standardized test scores alone do not reflect the quality

of an education program. (Natriello pp. 11, 189; LaFontaine p. 140;

Nearine p. 16; Negron pp. 15-16; Shea p. 140)

162. The differences in the performance between two groups of

students cannot solely be attributed to differences in the quality

of education provided to those groups without taking in account

differences in performance that are the product of differences in

the socioeconomic status of the students in the two groups. (Defs’

Ex. 10.12 Plynn pp. 151-153, 183; Armor p. 21; Crain pp. 78-79;

Natriello pp. 22-23)

163. In addition to poverty, among other reasons, Hartford

students may score lower on the CMT than the state average (1)

because many Hartford students move among Hartford schools and/or

move in and out of the Hartford school district, and (2) because

many Hartford students are still learning the English language.

(Shea p. 140; Nearine pp. 68-69; Negron pp. 15-16)

164. Hartford public schools attempt to administer the CMT to

every eligible student in the school system. (Nearine p. 73)

1565, Hartford Public Schools students as a whole do not

perform as well on the Connecticut Mastery Test ("CMT) as do the

students as a whole in some surrounding communities. (Defs’ Rev.

Answer 13)

166. The following figures concerning reading scores on the

1988 CMT are admitted to the extent that they are identical to

figures found in Pls’ Ex. 297, 298 and 299:

$ Below 4th Gr. $ Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk

Hartford : 57

*khkkhkkkkkhkkikk

Avon

Bloomfield

Canton

East Granby

East Hartford

East Windsor

Ellington

Farmington

Glastonbury

Granby

Manchester

Newington

Rocky Hill

Simsbury

South Windsor

Suffield

Vernon

West Hartford

Wethersfield

Windsor

Windsor Locks

167. The following figures concerning mathematics scores on

the 1988 CMT are admitted to the extent that they are identical as

figures found in Pls’ Ex. 297, 298 and 299:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk Remedial Bnchmk

Hartford 41 42 57

Avon

Bloomfield

Canton

East Granby

East Hartford

East Windsor

Ellington

Farmington

Glastonbury

Granby

Manchester

Newington

Rocky Hill

Simsbury

South Windsor

Suffield

Vernon

West Hartford

Wethersfield

Windsor

Windsor Locks

ND

_

-

f

t

[a

]

N

N

O

O

H

F

H

F

O

U

I

M

N

W

O

D

W

R

A

W

O

N

S

E

O

W

O

BH

be

te

s

yy

-

N

W

O

W

O

V

W

W

O

V

W

O

U

I

E

U

I

N

0

U

W

I

H

N

=

12

6

26

14

=

=

168. Public school students in Bloomfield, a middle class

town with an 85.5% minority population, produced CMT test scores

that were higher than several other suburban towns. (Crain pp. 90-

91; Pls’ Ex. 237-298)

169. Levels of performance on the Mastery Test are accurately

described in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 290-308. (Defs’ Revised Answer

141)

170. In addition to the mastery and remedial standards

required to be established by law, the State Board of Education has

established for the CMT in the areas of Mathematics, of reading

(Degrees of Reading Power [DRP]) and of writing statewide

achievement goals. (Defs’ Ex. 12.16 p. 4, Grade Four Test Results

Booklet)

17}. These statewide achievement goals represent high

expectations and high levels of achievement for Connecticut

students. (Defs’ Ex. 12.16 p. 4)

172. The statewide achievement goals as set by the State Board

‘of Education are:

a. In mathematics, all students must master 22 out of 25

objectives tested.

b. In reading, a student must achieve a score of 50 with 70%

comprehension in a Degree of Reading Power Unit.

c. In writing, a student must score a total holistic score of

7 ona _scale of 2 to 8. (Defs’' Bx, 12.16 p. 4)

» »

=23 =»

1991-92

Percentage of Students Failing to Meet State Goals and Remedial

Standards

for Math on the CMT

4th Grade 6th Grade 8th Grade

State Remed. | State Remed. | State Remed

Goals Stand. | Goals Stand. | Goals Stand

Hartford 80 41 94 42 89 41