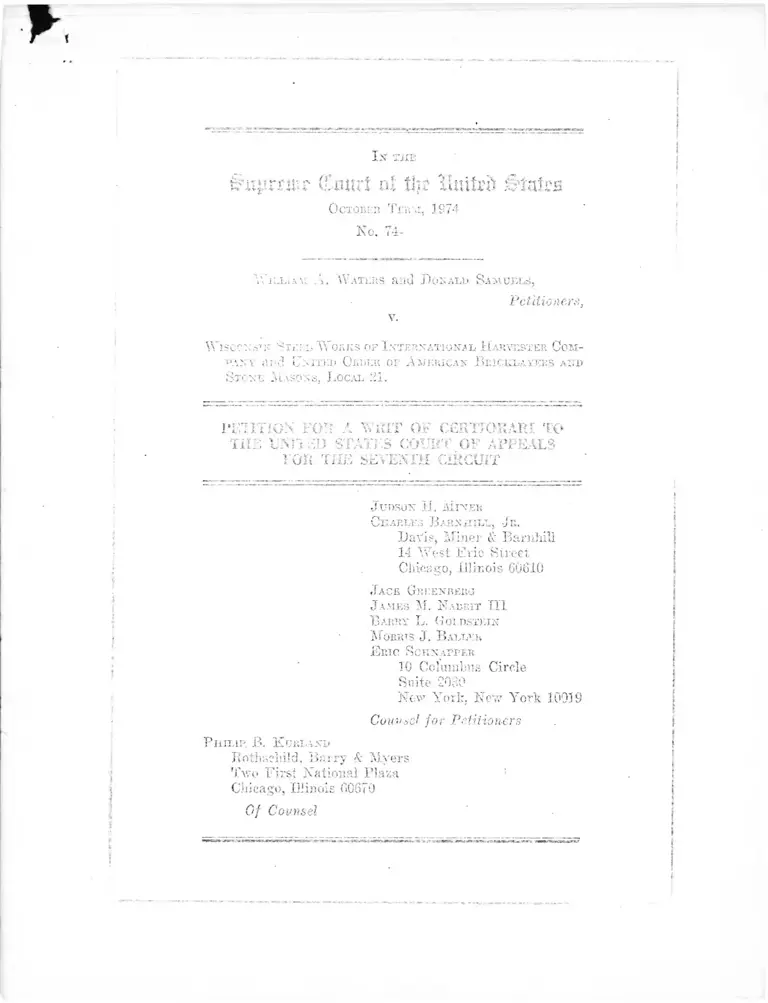

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvester Company Opinion

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvester Company Opinion, 1974. ac5765a9-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5a3e339-2315-4555-8f8e-170622962049/waters-v-wisconsin-steel-works-of-international-harvester-company-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I s 111 E

$?u*!rrutr (Emir! at the- llniin'i &tatisB

O ctokkb T er

No. 74-

1974

YvTluam A. 'Waters and D ojsalc Samuels,

Petitioners,

v.

Wiscem-urr Steel W orks of I nternational- H arvester Com

pany and U nited Order of A merican B ricklayers and

S tone Masons, Local 21.

PETITION FOB A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

i

f

i

1!

:ai

i

}

i

S

.Judson H. Miner

Ceakles B arnhill, Jr..

Davis, Miner & Barnhill

14 West Eric Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. F7acf.it III

B arry L. Goldstein

Morris J. B alleh

E ric S cknappf.r

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York. New York 10019

Counsel for Petitioners

Philip. B. FIuri.axd

Rothschild, Barry k Myers

Two First National Plaza

Chicago, Illinois 60670

Of Counsel

3 n tfje

V 'U U tU J 1 4 < w ,w $ * 4«’■>* *'tw

V ci» A*£ *-v %>**

Jfer tfje ê'ucnff; Circuit

Nos. 73-1822, 73-1823, and 73-1824 ^

W illiam A. Watlrs and D onald

S amuels,

PI a int iffs-A p pclla »Is,

v.

V. iscoxsix S ti lt, W orks of Inter

national H arvester Company, a

corporation, and U nited Order

of A merican B ricklayers and

S tone Masons, Local 21, an un

incorporated association, A p p e a l s from the

Defendants-Appellees. United States Dis-

-----------1 tricl Court for the

U nited Order or A merican B rick- I Northern District

layers and S t o n k Masoxs, f of Illinois, Eastern

No. 68 C 2483

. W illiam J.

Campbell, J v d o e .

Local 21,

Defendant-A ppcllant,

v.

W illiam A. Waters and D onald

S amuels,

PI ai nti ff s-A ppellees.

I nternational H arvester Com

pa n y ,

Def c. ndan t-A ppell a n t,

v.

W illiam A. W aters and D onald

S amuels,

Plain tiffs-Appellees.

A rgued A pril 22, 1974 — Decided A ugust 26, 1974

Before S wygert, Chief Judge, H astings, Senior Circuit

Judge, and S precher, Circuit Judge.

f

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

Swygf.rt, Chief .hidpc. Plaintiffs William A. Waters

and Donald Samuels, both black journeymen bricklayers,

appeal from a judgment of the district court, entered

after a bench trial finding that the defendants had violated

both Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 10(>4, 42

U.S.C. i 2000e ct sci/., and Section I of the Civil Rights

Act of 18(i(i, 12 U.S.C. ̂ 1981. The plaintiffs’ appeals

center solely on the district court’s

latiMir the plaintiffs’ back-pay award

approach to calcu-

and attornevs’ fees

under Title VII. Defendants International Harvester

Company (International), Wisconsin Steel Works of

International Harvester Company (Wisconsin Steel), and

Local 21. United Order of American Bricklayers and

Stone Masons (Local 21), cross-appeal from the district

court’s finding1 that they violated 1981 and Title VII.

1 nteniational

known as the

small force of

furnaces. Loea’

operates a large steel plant in Chicago,

Wisconsin Steel Works. Tt employs a

bricklayers to maintain and repair blast

21 is the exclusive bargaining representa

tive for the bricklayers employed by International.

Waters and Samuels Initiated an action in the district

court on December 27, 19687claiming lllht~certain em

ployment" practices and policies .of International and

joined in bv Local 21 denrived them of rights secured

hv: Section I of the Civil Rights Act of 18(i(i, 42 U.S.C.

V 1981: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. 42

U.S.C. § 2000 et. seq.\ the Labor Management Relations

Act. 29 U.S.C. § 185(a); and the National Labor Rela

tions Act, 29 U.S.C. $ 151 ct see/. Before filing their

suit, plaintiffs in Maw 1966 had .registered commands

with tioth the Illinois Pair Employment Practices Com

mission and the United States Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charging Wisconsin

Steel with racial discrimination due to Wisconsin Steel’s

.lpy_,-oT »f wm.nv and its subsequent refusal to rehire

lim and its failure to hire Samuels. The State Com -

'mission dismissed the charges as unsubstantiated; likewise

the EEOC concluded in a February, 1967 decision that

no probable cause, existed to believe that "Wisconsin Steel

had violated Title VIT. But as a result of new evidence

that white bricklayers had been hired after Waters sought

reinstatement and Samuels had requested initial employ-

i

3

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

limit. 1110 KFIOC reassutned jurisdiction and, on recon

sideration, it determined that the plaintiffs had cause, to

sue.

Shortly thereafter the plaintiffs initiated their action

as a class action against both International and Local

21. On defendants* motions, the district court dismissed

plaintiffs* claims. On appeal we reversed and remanded

the cause for a trial. H’n/ms v, ]]riwnnsin Sled 1 Vorl's,

427_F.2d 470 (7th Oir. 1070). vert, dewed. 400 U.S. Oil

(1070). On remand the plaintiffs abandoned their class

allegations and proceeded to trial on claims of individual

discrimination against the two plaintiffs.

At trial Waters challenged the existence of "Wisconsin

Stools “last hired, first tired” seniority system for brick

layers. Waters claimed the system violated section 1981

and Title All m that it perpetuated alleged prior dis

criminatory policies and hiring practices of the defen

dants. In addition, both plaintiffs condemned as violative

ol Section 1981 and Title A") 1 two amendatory agree

ments to the collective bargaining contract entered between

Wisconsin Stool and Local 21 which affected employee

recall rights and seniority status.

AA ith respect to the seniority system as it relates to

Waters, it was established at trial that the collective bar

gaining agreements between Wisconsin Steel and Local 21

have since 194fi provided for a “last hired, first fired”

seniority system for bricklayers employed at Wisconsin

Steel. The seniority system gives full credit to all brick

layers for their actual length of service or earned seniority

as bricklayers. Seniority vests after a 90-day probationary

period and may be broken by various events, including

lay-offs in excess of two years. The system governs the

order of lay-offs and recalls of bricklayers.

Waters first inquired about employment at Wisconsin

Steel in the fall of 1957. lie was told that no bricklayers

were being hired. Approximately seven years later Waters

inquired a second time for employment and was hired in

JjiiJy 1%» Two months later, in September 1934, Waters

was laid off according to his length of service and before

completing his 90-day probationary period and achieving

contractual seniority status. Waters’ lay-off was one of

'several lay-offs during late 1961 and 1965 which oecurred

as a result of an anticipated deerease in the steel plant’s

bricklaying needs because of a fundamental change in the

steelmaking process. (Paring this period, Wisconsin Stool

was converting from twelve open-hearth brick-lined fur

naces to two basic oxygen furnaces, and, consequently, it

bad been anticipated that tbo volume of brick maintenance

work would be correspondingly reduced.) By March 1905,

over thirty bricklayers with up to ten years seniority had

been laid oil. Wisconsin Steel had expected that over half

of the laid-oll bricklayers, including eight bricklayers with

five to six years seniority, would not In* recalled within the

two-year period and that pursuant to the terms of the

collective bargain ini: contract these bricklayers’ contrac

tual seniority rights would lie lost. T ------ -

During the course of the next year, however, Wisconsin

Steel became aware that it had underestimated its brick

layer requirements for tin* basic oxygen steelmaking pro

cess. The company therefore began recalling bricklayers

in the order of their length of prior service.

Besides the contractual right of recall for those em

ployees with contractual rights, Wisconsin Steel had a

policy that former employees, including bricklayers who

did not have contractual seniority rights would nonetheless

he recalled according to their length of service. Tn March

1967, pursuant to this policy and not because of contrae-

tiiaT right of recall, Waters was recalled. Waters accepted

reinstatement and continued to work until May 19, 1967

when lie was once again laid off because oT a "temporary

reduction in plant operations. Waters was recalled on

August 30, 1967, but refused this third offer of employment

because he had another job and also, because he believed

that his return to Wisconsin Steel might prejudice his

then pending EEOC charges against Wisconsin Steel which

he had filed in May 1966.

With respect to the amendatory agreements to the col

lective bargaining contract which plaintiffs challenge as dis

criminatory, the following evidence was adduced at trial.

Prior to 1965, Wisconsin Steel, unlike other steel plants,

had no provision for severance pay in its collective bar

gaining agreement with Local 21. However, in March

1965, after the decision had been made to lay off eight

white bricklayers having five to six years seniority, the

4

73-1822, 73-1823. 73-1824

73-1822, 73-1323, 73-1324

company negotiated a

21, dealing exclusively

“severance agreement” with Local

( ........................ with these eight employees. The

a^reeineiir provided that al ter being laid off the eight

bricklayers could elect to retain their contractual seniority

rights or receive $966.00 in severance pav. An elec I «' to

retain contractual seniority rights earned with it th< risk

that these bricklayers would lose then soniont) .'gut

alivwav after two vears on lay-off; this risk was lichee od

to ‘be substantial in view of Wisconsin Steels anticipated

decline in bricklaying needs. Consequently, the eight >i(>-

lavers. subsequent to their involuntary lay-off puisuant t

seniority. elected to receive severance pay, thereby foi-

feiting their contractual seniority rights to recall.

As noted earlier, it became apparent to Wisconsin

in I960 that it had underestimated its predicted Imu

laving requirement for the basic oxygen piocess.

of its new felt demand for brick avers and its asscided

belief that an injustice had been done to tlm cig

lavers who had exchanged their cont ract ua sc mo ib : c ;;

for 8066 00 the company proposed to Local -1 t « _

J to i l1 % 5 sov.-rn.u-i W bo.pai'OaUv mi11. .<■<!

bv an m m dm m * restoring the cfeM

tnal seniority rights lor purposes of iccall. Aceoictingi>,

arT a men da tor v agreement was mitered nto in June, 1906

Three of the'eight white bricklayers who had previous!)

?.h.V,Li tl!0 ‘•ev‘,ranco pav also accepted the recall and

renrned to 'worlg two hi Jlily 1906 and the third in Janu

ary 1967. In each instance the man was relnrcd without

reapplying with the company for employment.

\ t trial plaintiffs contended that the June I960 amonda-

torv agreement was. in effect, discriminatory or it re-

hruMayers wouU,

S=g»=S«2S£f!S

suant to their length of prior service.

After submission of the evidence the trial judge made

certain findings of fact. He also made the following con

clusions of law:

6

“4. Prior !o April, 1964, "Wisconsin olool diserimi-

rmtod in the hiring of bricklayers in violation of

42 U.S.C. $ 1381.

5. The seniority system negotiated between defen

dants Wisconsin Steel and Local 21 had its genesis

in a period of racial discrimination and is thus viola

tive of 42 U.S.C. ̂1381 and is not a bona fide senior

ity system under Title VII.

6. By laying off plaintiff "Waters in September, 1964,

pursuant to the terms of the seniority system of the

collective bargaining agreement, defendants violated

both § 1981 and Title VII. Defendants also violated

§ 1981 and Title VII when, in reliance on the scnior-

(ity system, Wisconsin Steel failed to recall plaintiff

(Waters in March, 1965, and when it again laid off

plaintiff Waters in May, 1967.

7. Defendants June 15, 1966 agreement to amend the

earlier severance pay agreement and thereby restore

recall rights to an all white group of bricklayers who

otherwise possessed no recall rights under the prior

severance pay agreement, thereby placing those white

bricklavers ahead of black bricklayers, constituted a

violation of both ̂1981 and Title VII. This viola

tion discriminated against the rights of both plaintiff

Waters and plaintiff Samuels.”

. Pursuant to its decision the district court directed Wis

consin Steel to offer employment to Waters and Samuels

and ordered both defendants to share in a back-pay award

of $5000 to Waters and $5000 to Samuels. In addition,

the court awarded the sum of $5000 as attorneys’ fee for

plaintiffs’ counsel and as a joint liability of the defen

dants.

We address the following issues in these appeals: (1)

Whether the district court properly asserted jurisdiction

over either defendant under 42 TJ.S.C. § 1981; (2) whether

an aggrieved plaintiff must exhaust grievance procedures

under a collective bargaining agreement before he can

initiate a lawsuit under section 1981; (3) whether the

trial court’s conclusion that defendant Wisconsin Steel

discriminated in the hiring of bricklayers prior to April

1964 is clearly erroneous; (4) whether the trial court erred

73-1822, 73-1828, 73-1824

7

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

in concluding that Wisconsin Stool’s “last hired, first, fired"

seniority system is violative of 42 1J.S.C. $ 1981 and is

not a bona fide seniority system under Title VH; (5)

whether there was error in holding that defendants’ June

15, I960 agreement to amend the prior severance pay

agreement thereby restoring contractual recall rights to

an all-white group of bricklayers constituted a violation

of section 1981 and Title VII; (6) whether the. participa

tion of defendant Local 21 as signatory to the collective

bargaining agreement as well as to the two challenged

agreements to amend the collective bargaining agreement

is sufficient to hold the union liable under section 1981;

(7) whether the district court erred in its calculation of

the hack-pay award; and (8) whether the district court

erred in its making the award of attorneys’ fees to counsel

for the plaint ill’s. We affirm in part the district, court’s

finding on liability, but reverse and remand with respect

to the questions of back-pay damages and attorney fees.

I

Local 21 opposes the district court’s assumption of juris

diction over it on two grounds: The union contends that

the plaintiffs did not justify their failure to file charges

against Local 21 with the EEOC under Title VII. In addi

tion, it challenges the standing of Waters to sue the union

under section 1981 on the basis that he was not at any

relevant time a member of the union.

With respect to the argument of Local 21 that the plain

tiffs have failed to prove a reasonable excuse for by

passing the. administrative procedures of Title VII, wc

previously addressed that issue, in Waters v. Wisconsin

StceJ, 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970) where we stated:

“We hold, therefore, that an aggrieved person may

sue directly under section 1981 if he pleads a reason

able excuse for his failure to exhaust EEOC remedies.

We need not define the full scope of this exception

here. Nevertheless, wc believe that plaintiffs in the

case at bar have presented allegations sufficient to

justify their failure to charge Local 21 before the

Commission.

We rely particularly on the following allegations.

The primary charge of racial discrimination made by

/

plaintiffs is hast'd on an amendment of flip colloctivo

bargaining agropniont between llarvostor and Loeal

21. That airn'mltnont occurred in dune 19GG after

plaintiffs filed their charge before the EEOC. Until

this amendment plaintiffs were, at least arguably,

unaware of the participation of Local 21 in Harvester’s

alleged policy of racial discrimination.’’ 427 F.2d at

487.'

The evidence adduced at trial supports plaintiffs’ allega

tion that tin' collective bargaining agreement amendment

occurred after the EEOC charge was filed thereby justify

ing the by-pass of the EEOC. Moreover, we note and are

somewhat inclined to agree, with the recent decisions which

hold that exhaustion of Title VII remedies, or reasonable

excuse for failing to do so, is not a jurisdictional prerequi

site to an action under section 1981. See, e.g., Long v.

Ford Motor Co., 42 U.S.L.W. 2599 (Gth Cir. April 30,

1974).

As to the contention that Waters lacks standing to sue

under section 1981, Local 21 premises its argument on the

assertion that jurisdiction under section 1981 is dependent

on a contractual relationship between Waters and the

union (which did not exist here for V. aters was not a

member of the union). Section 1981 assures that “all per

sons within the jurisdiction oi the United States shall have

the same right in every State and Territory to make and

enforce contracts . . . as is enjoyed by white citizens.” The

subject matter of this suit is cognizable under section 1981

for Waiters complains that his right to enter into an em

ployment contract with the company on the same basis as

whites was impaired by the joint action of the union and

company. It follows that his nonmeinbership in the

union has no bearing on his section 1981 claim against

Local 21.'

II

Local 21 contends that plaintiffs should be barred from

proceeding against the union under section 1981 because

they failed to exhaust their contractual remedies under

the'collective bargaining agreement. The nature of plain-

1 In addition, jurisdiction over Wisconsin Steel was properly enter

tained under both Title VII and section 1981.

8

73-1822. 73-1823. 73-1824

9

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

tiffs' claims however is that of a complaint against racial

discrimination in employment and not a labor law action,

asserting rights under a collective bargaining contract.

Indeed, the focus of this civil rights suit is an attack by

plaintiffs on the contract itself as embodying racially dis

criminatory practices.

Title VII and section 198,1 arc “parallel or overlapping

remedies against discrimination.” Alexander v. Gardner-

1 loner Co., No. 72-f)S47, at p. 10 (U.S. 1974). Conse

quently. in fashioning a substantive body of law under

section 1981 the courts should, in an effort to avoid unde

sirable substantive law conflicts, look to the principles of

law created under Title VII for direction. It is well-estab

lished that under Title VII there is no exhaustion of con

tractual remedies requirement. Alexander v. Gardner-

Deni er Co., supra, at p. 12; Rios v. Reynolds Metal Co.,

4G7 F.2d 54, 57 (5th Cir. 1972); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive

Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969). Moreover, an exhaus

tion of remedies requirement does not. appear to apply to

claims for relief brought under any of the civil rights acts.

See Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1960); McNeese v.

Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963); D’Amico v. Cali

fornia, 389 U.S. 416 (1967); and King v. Smith, 392 U.S.

309 (1968)2 We are of the view, therefore, that plain

tiffs could properly proceed against the union under section

1981 without first exhausting any contractual remedies

under the collective bargaining agreement.

m

Wisconsin Steel contends that the evidence does not.

support the district court’s holding that “ [p]rior to April,

1964, Wisconsin Steel discriminated in the hiring of brick

layers in violation of 42 U.S.C. §1981.” We believe the

record supports the conclusion that Wisconsin Steel en

gaged in racially discriminatory hiring policies with respect

to the position of brieklaver prior to the enactment of

Title VI t.

Wisconsin Steel did not hire its first black bricklayer

until April 1964.although blacks had made inquiries seek

ing employment as early as 1947. In addition, the evi- 2

2 Although these cases treated the exhaustion of remedy requirement

with respect to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 of the Civil Rights Act, we think the

Court's analysis is applicable to actions brought under 42 UJ3.C. § 1931.

7.1-1822. 7.1-182.1. 7.1-182-1

10

• li'iici' rHli'cfs :\ discriminnfnrv depnrtmontfil Irnnsfor

poliry whereby Macks hired by Wisconsin Steel as labor

ers were denied the opportunity available to white labor

ers to transfer to the bricklayers’ apprenticeship program.

it is urged by the company that the “single statistic”

oi no black bricklayers prior to lSHil is not sufficient to

make a showing of discrimination. Although we doubt the

validity of this contention (see Jones v. Lee Way Motor

Freight, Inc.. 4,11 R2d 245, 247 (10th Cir. 1070); Parham

v. Southwest cm Bell Tel, Co., 4.1.1 F.2d 421, 42(> (8th Cir.

1970)), we think that the statistical data joined by the

evidence indicating repeated attempts by blacks to obtain

employment as bricklayers substantiates the trial court’s

finding of discrimination.

Wisconsin Steel further contends that plaintiffs did not

make a showing of past racial discrimination because they

tailed to prove that black applicants were denied actual

job openings. Relying on McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 IJ.S. 792 (1973), the defendant in effect urges

that discrimination can only he shown if there is a precise

matching of job openings and job applicants. While a

showing of matching might be required where the focus

ot inquiry is on an “individualized hiring decision,” such

as in McDonnell Douglas,3 we do not believe such a show

ing is required, where, as hero, the inquiry centers on

whether the employer engaged in discriminatory hiring

procedures or practices in the past unrelated to ’the sub

sequent employment applications. Accordingly, we do not

find McDonnell Douglas controlling on this issue.

IV

With respect to the validity of Wisconsin Steel’s em

ployment seniority system which embodies the “last, hired,

-’ In McDonnell Douglcus v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1373), the Court

stated that a plaintiff in a Title VII case establishes a prinia facie case

of discrimination by showing:

"(i) that he belongs to a racial minority; (ii) that he applied

and was qualified for a job for which the employer was seeking

applicants; (iii) that, despite his qualifications, he was rejected;

and (iv) that, after his rejection, tire position remained open and

the employer continued to seek applicants from persons of com

plainant’s qualifications.” 411 U.S. at 802.

In referring to the foregoing elements, the Court stated in a footnote:

‘‘The facts necessarily will vary in Title VII cases, and the

specification above of the prima facie proof required from respondent

is not necessarily applicable in every respect to differing factual

situations.” 411 U.S. at 802, fn. 13.

i—

11

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

first fired" principle* of seniority for job recalls and lay

offs, the district court held:

;>. I ho seniority system negotiated between defen

dants 'Wisconsin Stool and Local 21 had its genesis

in a period of racial discrimination and is thus viola-

t i\o ot 42 b.S.t . 1 !)S! and is not a bona tide seniority

system under Title VIl.

6. By laying off plaintifT Waiters in September, 19(14,

pursuant to the terms of the seniority system of the

collective bargaining agreement, defendants violated

both ̂ 1981 and Title VII. Defendants also violated

̂ 1981 and title' \ !l when, in reliance on the senior

ity system, Wisconsin Steel failed to recall plaintifT

Waters in March, 1965, and when it again laid off

plaintiff Waters in May, 1967.”

The plaintiffs contend that Wisconsin Steel’s employ

ment seniority system perpetuates the effects of past dis

crimination in view of the facts that blacks will he laid

oil before and recalled alter certain whites who might not

otherwise have had seniority had Wisconsin Steel not dis

criminated in hi rimw prior to 1964. They argue that such

a system facilitates a return to the status quo of the era

when Wisconsin Steel hired no black bricklayers. Wiscon

sin Steel argues, however, that an employment seniority

system which accords workers credit for the full period

of their employment is racially neutral and as such is a

bona fide seniority svstem within the contemplation of

$ 703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-2(h). The defen

dant says that to strike down its employment seniority

system would be to countenance reverse discrimination.

It is asserted that, here there is an employment senior

ity system (unlike the departmental or job seniority sys

tems which courts have modified under Title VLI) which

grants workers equal credit for actual length of service

with the employer. Under a departmental seniority system,

seniority is measured by length of service in a department

while a jolt seniority system accords seniority on the

basis of length of service on a job. The decisions modify

ing these two forms of seniority systems have routinely

involved situations where the employer previously main

tained segregated work forces, prohibiting transfers by

blacks into various jobs or departments which offered

improved employment conditions. With the. advent of

Title VII tin' employer would facially lift the restric

tions on transfers hut would effectively prohibit transfers

through a department or job seniority policy whereby

blacks would be given no credit for their previous years

of employment with the employer and would be placed

at the bottom of the employee roster in the. formerly all-

white job or department to which they transferred. Often

in modifying these discriminatory forms of seniority sys

tems thi' courts have deployed an employment seniority

system as a racially neutral and adequate remedy to the

discriminatory impact of the prior seniority systems.

We are of the view that Wisconsin Steel’s employment

seniority system embodying the “last hired, first fired”

principle of seniority is not of itself racially discrimina

tory or does it have the effect of perpetuating prior racial

discrimination in violation of the strictures of Title VII.

To that end we find the legislative history of Title VII

supportive of the claim that an employment seniority sys

tem is a “bona fide” seniority system under the Act. The

history points out that:

“Title. VI1 would have no effect on established se

niority rights. Its effect is; prospective and not retro

spective. Thus, for example, if a business has been

discriminating in the past and as a result has an all-

white working force, when the title conies into effect

the employer’s obligation would be simply to fill future

vacancies on a nondiscriminatory basis. He would

not be obliged—or indeed, permitted—to fire whites

in order to hire Negroes, or to prefer Negroes for

future vacancies, or, once Negroes are hired, to give

them special seniority rights at the expense of the

ichite workers hired earlier. (However, where waiting

lists for employment or training are, prior to the

effective date of the title, maintained on a discrimi

natory basis, the use of such lists after the title takes

effect may be held an unlawful subterfuge to accom

plish discrimination.)” Interpretative Memorandum

of Senators Clark and Case, 110 Cong. Roc. 7213

(April. 8, 1964). (Emphasis added).

In response to written questions by Senator Dirksen, one

of the Senate floor managers for the bill, Senator Clark,

12

72-1822, 73-1822, 72 -1824

/

emphasized (hat the “last hired, first fired" principle of

seniority would he preserved under Title. VII:

“Question. Would (he same situation prevail in

respect to promotions, when that management func

tion is governed by a labor contract calling for pro

motions on the basis of seniority! What of dismiss

als? Normally, labor contracts call for ‘last hired,,

first fired.' If the last hired are Negroes, is the em

ployer discriminating if his contract requires that

they be first fired and the remaining employees are

white""

“Answer. Seniority rights are in no way affected

by the bill. If under a ‘last hired, first, fired’ agree

ment a Negro happens to be the ‘last hired,’ he can

still be ‘first fired’ as long as it is done because of his

status as ‘last hired’ and not because ol his race.’'

11(1 t\>ng. dec. 7217 (April S, 1!)(i4).

Moreover, to alleviate any further doubt as to the mean

ing of Title VII, Senator Clark obtained an interpretative

memorandum from the Department of Justice which indi

cated that “last hired, first fired” seniority rules would

be valid under Title VII :

“Title VII would have no effect-on seniority rights

existing at the time, it takes effect. If, for example,

a collective bargaining contract provides that in the

event of layoffs, those who were hired last must be

•laid off first, such a provision would not be affected

in the least by title VIT. This would be true even

in (he case where owing to discrimination prior to the

effective date of the title, white workers had more

seniority than Negroes. Title VII is directed at dis

crimination based on race, color, religion, sex or

national origin. It is perfectly clear that when a

w ork er is laid off or denied a chance for promotion

because under established seniority rules lie is low

man on the totem pole lie is not being discriminated

against because of his race.” 110 Cong. Rec. 7207

(April 8, 1964).

In Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D.

Va. 1968), the district court was faced with a proposal by

the plaintiffs, akin to that presented here, in derogation

13

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

I

of the employment seniority

after a thorough anahsis ot tut

Title YLT, Judge Butzner wrote:

“ IT I he plaintiffs’ proposal, while not ousting whit*.

|£ S

result was intciuM.” 2711 I'hSupp. at 519.

Similnrlv. the Fifth Circuit in l>assinK upon the legislative

history of Title VII stated: _

' “No doubt, Congress, to prevent Reverse ^ c r im i

nation’ meant to protect certain senumt> rifehts that

could not have existed but for V™™™ i «

crimination, For example a Negro ppforP

reieeted by an employer on racial grounds tieiom

p is a -e of the Act could not, after henig hired, chuin

to outrank whites who had been hired before lum but

after ds oV'inal rejection, even though the Negro

m'mbt have* had senior status but for the past disernm-

nation As the court pointed out in Quarles, ih* treat

ment of ‘job’ or ‘department seniority laises pro

lems different from those _ discussed in the 8u

debates • ‘a department seniority system that has its

genesis in racial discrimination .8 not a bona fide

seniority system.5 ” 2iv r.oupp. a, on .

“ It is one thing for legislation to require the crea-

requiring employers to coirect th e . 1 V .

-

b fn rg u a ra n tv lth a tT e new employees had actually

suffered exclusion at the hands of the emploxei m

C o w iiS ’^ e S iT ttv being

hired Negroes would, comprise preferential rather

14

73-1822. 73-1823.73-1824

15

75-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

than remedial treatment. The clear thrust, of the

Senate debate is directed against such preferential

treatment on the basis of race.

“We conclude, in agreement with Quarles, that Con

gress exempted from the anti discrimination require

ments only those seniority rights that gave white

workers preference over junior Negroes.” Local 189,

United Paper male <fi Paperwork v. United States,

41(> F.2d 9S0, 8!) 1-95 (5th (hr. 19(59), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 919 (1970). [Emphasis in original and

added].

Title VII mandates that workers of every race, be

treated equally according to their earned seniority. It

does not require as the Fifth Circuit said, that a worker

be granted fictional seniority or special privileges be

cause of his race.

Moreover, an employment seniority system is properly

distinguished from job or department seniority systems

for purposes of Title VII. Under the. latter, continuing

restrictions on transfer and promotion create unearned

or artificial expectations of preference in favor of white

workers when compared with black incumbents having

an equal or greater length of service. Under the employ

ment seniority system there is equal recognition of em

ployment seniority which preserves only the earned ex

pectations of long-service employees.

Title VII speaks only to the future. Its backward gaze

is found only on a present practice which may perpetuate

past discrimination. An employment seniority system

embodying the “last hired, first tired” principle does not

of itself perpetuate past discrimination. To hold other

wise would be tantamount to shackling white employees

with a 'burden of a past discrimination created not by

them but by their employer. Title VII was not designed

to nurture such reverse discriminatory preferences.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430-31 (1971).

We are not, however, insensitive to the plaintiffs’ argu

ment, and think employers should be discrete in devising

an employment seniority system. We recognize that it is

a fine line we draw between plaintiffs’ claim of discrimi

nation and defendants’ countercharge of reverse discrimi-

nation. On balance, we think Wisconsin Steel’s seniority

system is racially neutral and does not perpetuate the

discrimination of the past/

16

73-1S22, 73-1823, 73-1S24

Y

We come finally to the pivotal issue in determining

liability: whether'the dune If), 1000 agreement between

Local 21 and Wisconsin Steel to amend an earlier

severance pay agreement and thereby recall three white

bricklayers who had accepted severance pay under the

initial agreement discriminated against the plaintiffs in

violation of Title Yll and section 1981. In light of

Wisconsin Steel's past history ol racially discriminatory

hiring practices and the racially neutral yet potentially

discriminatory impact of the employment seniority system

utilized by the company, we hold that the June 19u6

agreement reinstating contract recall rights to three

white bricklayers was racially discriminatory with respect

to Waters, but not discriminatory with respect to

Samuels.

The defendants contend that the restoration of con

tractual seniority rights to the white bricklayers who

had previously accepted severance pay did not discrimi

nate against the plaintiifs for it is claimed that the white

bricklayers would have been entitled to prior recall m

any event in accordance with company policy. As we

noted earlier, that policy, pursuant to which plaintiff

Waters was himself recalled, provided that lormer em

ployees without contractual rights of recall would

nonetheless he recalled in order of their length of prior

service. We do not doubt that a policy favoring recall

of a former employee with experience even though white

before considering a new black applicant without ex

perience comports with the requirements of Title VII

and section 1981. To that end, we do not perceive any

discriminatory impact with respect to Samuels who was

a new applicant.

With respect to Waters, however, the company policy

occupies a different posture. At the outset we note that

it is not entirely clear what the company policy was with

4 Having passed scrutiny under the substantive requirements of title

VII, the employment seniority system utilized by Wisconsin Steel is not

violative ol 42 U.S.C. § 1931.

17

w lT ln /? <!l°< 1Jriority Sfi,,us of tl,(- "lute bricklayers

’ W , ■ SPVl’rar o |,av vis ;Vvis «»Ployoos lu-h" ' atois wlio possessed no contractual seniority. Even

a.snnm - that the priority of the white bricklayers ac-

(iptm - severance pay emanated from a long-standin^

company policy and not from an ad hoc determination"

we are inclined to find that aspect of the company policy

to lie wolafno ot Title MI and section 1981. We reach

73-1822, 73-1823, 73-1824

such a conclusion due to the tact that .Wisconsin Steel

ofr°nngh„mSi lirior discrimination and its implementation

1 an imphnmoid seniority system occupied a racially

precarious position—indeed, at the brink of present dis-

ennnna.ion A company policy of according priority to

Mute bricklayers who bad accepted the benefits of sever

ance pay would, m our view, project the company into

iiitinn‘a ? m° presently perpetuating the racial diserimi-

ation ol the past. J be company policy is no defense to

tiie del aidants action m entering the June 1968 agrcc-

m e n t^ to rm g contractual seniority to three white brick-

We find the June I960 agreement, therefore, to be

discriminatory with respect to Waters. Moreover, it can

not be urged that tiie agreement was justified by “busi

ness necessity.” The practice of restoring contractual

senionty to white bricklayers who elected to receive

severance pay must be justified, if at all, by a showing

U v- Duke Poi^ r p o., 401U. S. 4-1, lo l (19/1). Jn that respect an employment

practice ‘ can be justified only by a showing that it is

necessary to the safe and efiicicnl operation of the busi-

m p n R° h - ^ )l V- Loril,ard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 797

i t h .Vor; quoting, Jones v. Lee Way Molar Freight,

*■ - b--d -4o, _49 (10th Cir. 1970). Defendants’ claim of

employee-employer goodwill and alleged concern for fear

oi potential labor strife does not rise to the level of

urgency required for a demonstration of business necessity.

VI

Local 21 contends that there is insufficient evidence to

support a claim against the union under section 1981 It

is enough, however, that the union was an integral party

to the June 1966 amendment which discriminated against

'Water?. Johnson v. Goaducar Tire <£ Rubber Co., 7 EPB,

U9233 (T)111 (*jr. 1974). Local 21 therefore shares jointly

in the liability of Wisconsin Steel.

18

73-1822. 73-1823, 73-1824

Both Waters ami defendants join in the contention

that the district court erred in calculating the back-pay

award to which Waters is entitled. We agree that the

trial judge abused his discretion in fashioning the hack-

pay award. The award was the product of an arbitrary

calculation entirely devoid of any reasoned approach to

the proper measure of damages. Moreover, the district

court’s consideration of the absence of a racially discrimi

natory motive on the part of the defendants was improper.

The absence of a discriminatory motive is not a proper

basis for denying or limiting relief. Robinson v. Loriliard

Corp., 444 E.2d 791, 804 (4th Cir. 1971).

It would appear from the record that but for the dune

I960 agreement, Waters would have been recalled on

January 17, 1967 and that he would not have been laid

off on May 19, 1967, Waters was tendered reemployment

on September 5, 1967, which he declined to accept. In our

judgment the discriminatory impact of defendants’ June

1966 agreement, ended with the tender made to Waters

in September. The relevant period for computing damages

therefore ranges from January 17, 1967 to September

f>, 1967.

Plaintiff Waters’ damages for the relevant period are

to be determined by measuring the difference between

plaintiff’s actual earnings for the period and those which

he would have earned absent the discrimination of de

fendants. Jn determining the amount of Waters’ likely

earnings but for the discrimination, we reject the notion

advanced by Waters that since he could have held two

jobs while employed at Wisconsin Steel, defendants are

therefore liable not only for his lost earnings with

Wisconsin Steel but also for his probable lost earnings

from a second job. Recompense for economic loss result

ing from racially discriminatory practices does not

require that we entertain claims of such a speculative and

remote nature.

.

I

19

Accordingly, wo remand to the district court for find

ings with regard to Waters’ actual and probable earnings

for the relevant period.6

79-1822, 73-1823, 73-1324

VIII

All parties condemn the district court’s method of

computing the award of attorney fees to the plaintiffs’

counsel pursuant to section 700K of Title VI1, 42 U.S.O.

§ 2000e-f)(K). Although the determination of reasonable,

attorney fees is left to the sound discretion of the trial

judge, \VrcLs v. Southern. Bell Tele. <(': Tele. Co., 467 F.2d

95, 97 (5th (_'ir. 1972), we are convinced that the method

whereby the judge computed the award of attorney’s fee

was so lacking of analysis that it constituted an” abuse

of discretion.

In fashioning a method of analysis to assist in determin

ing the amount of attorney fees properly to be awarded

in a Title Vi I action, we cannot subscribe to the view

that attorney fees are to be determined solely on the

basis of a formula applying “hours spent times billing

late.” We recognize however that such a factor is a con

sideration in making the ultimate award and indeed it

is a convenient starting point from which adjustments

can be made for various other elements. Other elements

to be considered are set out in the Code of Professional

Responsibility as adopted by the American Bar Associa

tion : .

Factors to be considered as guides in determining the

reasonableness of a fee include the following:

(1) The time and labor required, the novelty

and difficulty of the questions involved, and

the skill requisite to perform the legal

service properly.

(2) The likelihood, if apparent to the elient,

that the acceptance of the particular eim

ployment. will preclude other employment by

the lawyer.

5 It would appear that Wisconsin Steel concedes in its brief that

Waters would not have been laid off on May 19, 1967 had he been

recalled on January 17, 1967. (Defendant's Brief, n. 44.) The rc-cotd is

not clear on this matter. Therefore we direct that there be findings

thereon if defendant does not concede the point. It should be noted

however that the outer most parameters of defendants’ liability extend

from January 17, 1907 to September 5, 1807.

73-1822, 73-1823. 73-1824

20

(3) Tiio fee customarily charged in the locality

for similar legal services.

(4) The amount involved and the results ob

tained.

(5) The time limitations imposed by the client

or by the circumstances.

(0) The nature and length of the professional

relationship with the client.

(7) The experience, reputation, and ability of

the lawyer or lawyers performing the ser

vices.

(8) Whether the fee is fixed or contingent.

Disciplinary Rule 2-106.

The Code of Professional Responsibility clearly reflects

that an award of attorney fees involves the coalescence

of many considerations including the reasonableness of

the time spent hv counsel, the extent of counsel’s success,

and the complexity of the case. An analysis by the district

court which encompasses the foregoing considerations is

most assuredly an analysis well within the bounds of

trial court discretion. Accordingly, we remand to the

district court for reconsideration of attorneys’ fees in

light of the aforementioned factors.

The judgment of liability is affirmed in part as to plain

tiff Waters and reversed as to plaintiff Samuels. In ac

cordance with Circuit Rule 23 we remand for further

consideration on the question of damages and award of

attorney fees to plaintiff Waters, consistent with the

views expressed herein.

A true Copy:

Teste:

Clerk of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.

USCA 4031—The Scheffer Press, Inc., Chicago, Illinois—8-26-74—225