United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Steel Workers of America v. Webber Brief for Respondents, 1979. 86bf07ec-c79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5a4ca0f-5a46-4ecf-838a-8a306091624a/united-steel-workers-of-america-v-webber-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

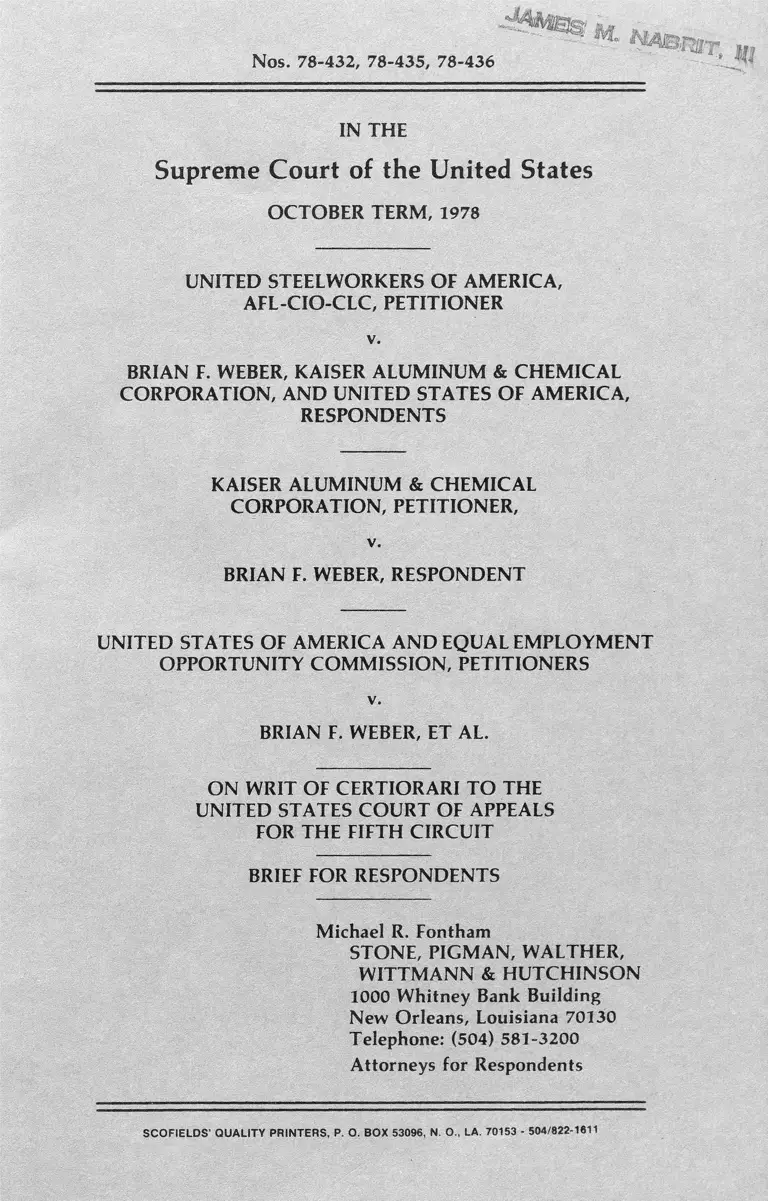

Nos. 78-432, 78-435, 78-436

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO-CLC, PETITIONER

BRIAN F. WEBER, KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

RESPONDENTS

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, PETITIONER,

BRIAN F. WEBER, RESPONDENT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND EQUAL EMPLOYMENT

OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION, PETITIONERS

BRIAN F. WEBER, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Michael R. Fontham

STONE, PIGMAN, WALTHER,

WITTMANN & HUTCHINSON

1000 Whitney Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Telephone: (504) 581-3200

Attorneys for Respondents

SCOFIELDS’ QUALITY PRINTERS, P. O. BOX 53096, N O., LA. 70153 - 504/822-1611

INDEX

Index ................................................................................... i

Table of Authorities ..................................................... iv

Question Presented............................. 2

Statement of the Case ....................... 2

1 . Application of the Agreement

between Kaiser and U SW A .......................... 3

2 . Desirability of the craft positions ................. 6

3. Impact on the white workers ...................... 9

4. Reasons for the adoption of the racial

quota ................................................... 12

5. Availability of minority craftsmen . . . . . 16

6 . Absence of prior discrimination...................18

7. Procedural background............. 22

8 . Published posture of the Government........ 25

Argument ...................................................................... 29

Summary of Argument ......................... 29

I. THE RACIAL QUOTA IMPOSED BY

KAISER AND USWA IS ILLEGAL

UNDER TITLE VII BECAUSE IT

DISCRIMINATES AGAINST NON-

MINORITY EMPLOYEES........................ 33

A. Race Discrimination Against Any

Employee Is Prohibited Under Ti

tle VII, Whether or Not the

Page

11

Employee Is a Member of a

G o v e r n m e n t - R e c o g n i z e d

Minority Group ....................................34

B. The Analogous Constitutional

Decisions of the Court Establish

That the 50 Per Cent Racial

Quota Would Not Be Upheld if It

Were Imposed By the Govern

ment ........................................................46

II. THE PURPORTED JUSTIFICA

TIONS OFFERED BY KAISER,

USWA AND THE GOVERNMENT

FOR THE 50 PERCENT QUOTA

ARE INSUFFICIENT TO VALI

DATE THE POLICY OF OPEN DIS

CRIMINATION AGAINST WHITE

WORKERS ...................................................53

A. The 50 Per Cent Quota Was Not a

Remedial Measure and Could Not

Be Upheld in Any Event Because

It Was Not Restricted to In

INDEX (Continued)

Page

dividual Victims of Past Dis

crimination ............................................54

1. The reasons for the racial

quota are fully established in

the record....................................... 56

I l l

2 . Persuasive evidence of past

discrimination by Kaiser

could not have been present

ed at the trial because it does

not exist ...................................... .. 58

3. The 50 per cent quota is not

legal as a remedy because

none of the persons pre

ferred under the quota were

v i c t i ms of pas t di s

crimination by Kaiser .....................70

B. The Legislative History of Title

VII Does Not Support the In

ference of USWA that Racial

Preferences for Minorities Are

Allowed, Though Not Required,

Under the Statute ...................................76

C. The Discrimination Against

White Workers Is Not Validated

By Executive Order 11276 or the

Affirmative Action Guidelines of

the EEOC ............................... 79

D. A Policy Permitting the Advance

ment of Minority Workers at the

Expense of Whites Could Have

Adverse and Unmanageable Con

INDEX (Continued)

Page

sequences .......................................... 83

Conclusion ..................................................................... 89

IV

Cases:

City of Los Angeles, Department of Water & Power v.

Manhart, 435 U.S. 702, 98 S.Ct, 1370 (1978) . . . 37

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O'Neil, 5 EPD f

7974 (3d Cir., 1972), affirmed in part and re

versed in part on rehearing en banc, 473 F.2d

1029 (3d Cir., 1973) .............................................. 82

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 311 F.Supp. 1002 (E.D. Pa.,

1970) .......................................................................... 64

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir., 1975),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ........................ 80,81

Franks v. Bowman Construction Corp., 424 U.S. 747 ,

96 S.Ct. 1251 (1976) ....................... .....................73

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, ____ U.S.

------, 98 S.Ct. 2943 (1978) ....................... .. 37

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125, 97

S.Ct. 401 (1976) ............................. 47,81,82

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct.

849 (1971) ........... 36,41,42,77,82

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S.

299, 97 S.Ct. 2736 (1977) .................................... 70

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 97 S.Ct. 1843 (1977) . . 44,72,

73,75

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

rage

V

Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v. Local 32 7 ,1BEW,

508 F.2d 687 (3d Cir., 1975) ................................ 41

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351, 94 S.Ct. 1734

(1974) ....................... 49,52

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 65 S.Ct.

193 (1944) .......................... 48

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-C10, CLC v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir., 1969) . ................................................... 38,42

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 87 S.Ct. 1817

(1967) ............. 48

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427

U.S. 273, 96 S.Ct. 2574 (1976) ................ .. 35,38,

39,77

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, _ _

U.S. ___ , 98 S.Ct. 2733 (1978) ..................... 28,46,

47,48,49,50,51,73,84

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 89 S.Ct. 1322

(1968) ................... 49

Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 65 S.Ct.

161 (1944) ............................... 81

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 471

F.2d 680 (7th Cir., 1972) ................... 80,81

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144,

97 S.Ct. 996 (1977) ....................... 85,86

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir., 1974) ___41

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

V I

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

579, 72 S.Ct. 863 (1952) ...................................... 79

Constitutional Provisions,

Statutes and Regulations:

U. S. Const. Amend V ................................................ 46

U. S. Const. Amend XIV ........................ 46,47

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §2000d et seq. (1976) .46

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. (1976) .34

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a)

(1976) .................................................................34,82

Section 703(a)(1), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (a)(l)

(1976) ................................................................ 76,77

Section 703(d), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (d)

(1976) ................................................... 34,75,77,82

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (h)

(1976) .................................................................... 48

Section 703(j), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (j) (1976) . . 39,78

Section 713(b), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-12 (b)

(1976) ................................................................... 26

Section 713(b)(1), 42 U.S.C. §20G0e-

12(b)(1) (1976) .................................................... 26

42 U.S.C. §1981 (1976) ................................... 2,23,46

29 C.F.R. Part 1608 (1979) ........................................ 25

29 C.F.R. §1608,1 (1979) ........................................... 25

29 C.F.R. §1608.2 (1979) ........................................... 25

29 C.F.R. §1608.3 (1979) ........................................... 26

29 C.F.R. §1608.4 (1979) .................... 84

29 C.F.R. §1608.4(a) (1979) ........................................27

29 C.F.R. §1608.4(b) (1979) ............................... 26,59

29 C.F.R. §1608.4(c) (1979)........................................28

29 C.F.R. §1608.5 (1979) ....... 28

41 C.F.R. Part 60.2 (1978) ......... ................ 27,84

41 C.F.R. §60-2.11 (1978) ..........................................80

41 C.F.R. §60.2.11(b) (1978) ......................................27

41 C.F.R. §60-2.12 (1978) ..........................................27

Miscellaneous:

110 Cong. Rec. (1964):

P- 6549 ................................................................ 40,74

p. 7213 ............................................................ 78

p. 7218 ....................................................... .39

p. 8921 ................................................................. 40,78

p. 11847 ......................................................................40

p. 12723 ...................................................................... 78

117 Cong. Rec. (1971):

p. 31963 ................ ................................ . 42,43

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

vm

p. 31964 .......................................................................

p. 31965 ................................................................... 43

124 Cong. Rec. (daily ed„ June 13, 1978):

p. H5371 .....................................................................

p. H5379 ................. 45

The Challenge Ahead, Equal Opportunity in

Referral Unions (U.S. Comm'n. on Civ.

Rts„ May, 1 976 )........... 65

EEOC Decision No. 74-106 (1974), CCH

Employment Practices Guide 1 6427 .............. 82

EEOC Decision No. 75-268 (1975), CCH

Employment Practices Guide U 6452 (1975)___82

Executive Order 11246, Subpart D, §209 . . 27,59,79

The National Apprenticeship Program (U.S.

Dept, of Labor, Employment and Training

Admin., Rev., 1976) ............. .7,67

Note, Developments in the Law — Employment Dis

crimination and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964r 84 Harv.L.Rev. 1109 (1971)...................... 86

Report No. 95-1746, 95th Cong., 2d Sess., 25

(Oct. 6 , 1978) ................................... 45

Supplementary Information, Guidelines on

Affirmative Action, CCH Employment

Practices Guide H 4011.11 ............................... 28,83

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

IX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970 Census of

Population; Vol. 1 : Characteristics of the

Population:

Part 20 , Louisiana, Appendix B, App. 4 0 ............62

Part 20 , Louisiana, Table 172 .......................... 62,66

Part 40, Philadelphia, Pa.-N.J., SMSA, Table

1 7 2 ........................... .............................................6 4

Nos. 78-432, 78-435, 78-436

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

UNITED STEELWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO-CLC, PETITIONER

BRIAN F. WEBER, KAISER ALUMINUM &

CHEMICAL CORPORATION, AND UNITED

STATES OF AMERICA, RESPONDENTS

KAISER ALUMINUM & CHEMICAL

CORPORATION, PETITIONER,

BRIAN F. WEBER, RESPONDENT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND EQUAL

EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

PETITIONERS

BRIAN F. WEBER, ET AL.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

2

QUESTION PRESENTED

May an employer and labor union, solely in order to

achieve a desired ratio of minority workers in craft

positions at a manufacturing plant and in the absence

of any prior discrimination against the minority

workers at that plant, institute a racial quota for admis

sion to craft training programs that is preferential to

members of minority groups and discriminates against

whites, where job seniority would ordinarily determine

entry into the training programs?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In order to achieve a desired ratio of minority

workers in craft jobs at a manufacturing plant in

Gramercy, Louisiana, petitioners, Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corporation ("Kaiser") and United Steel

workers of America ("USWA"), instituted a racial

quota requiring that at least 50 per cent of all applicants

selected into craft training programs be members of

minority groups. Brian F. Weber and the class of

similarly situated white workers at the Gramercy plant

brought an action under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. §1981, alleging that the 50

per cent racial quota discriminated against them un

lawfully. An injunction was granted in favor of the

plaintiffs by the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Louisiana1 and this decision was af-

1 Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 415 F.Supp. 761 (E.D.

La., 1976).

firmed by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit.2

1. Application of the agreement between

Kaiser and USWA.

The racial quota of Kaiser and USWA was instituted

as part of the 1974 Labor Agreement executed by the

parties. The agreement provided in part that "certain

goals and time tables" would be established by a joint

committee to facilitate the achievement of a "desired

minority ratio" in existing trade, craft and assigned

maintenance classifications at various Kaiser plants,

including the Gramercy Plant.3 The percentage "goal"

established by the joint committee for the Gramercy

Plant was 39 per cent, based on the percentage of

minority workers in the available work force in the

area.4 5 The agreement stated;

[A]t a minimum, not less than one minority

employee will enter for every non-minority

employee entering until the goal is reached

unless at a particular time there are insuf

ficient available qualified minority candidates

5

3

2 Weber v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 563 F.2d 216 (5th Cir.,

1977).

3 App., 137.

4 App., 60.

5 App., 137.

4

Kaiser estimates that the 50 per cent quota must ex

ist for at least 30 years in order to reach the 39 per cent

goal,6 If and when the goal is reached, a percentage

quota reflecting the percentage of minority workers in

the overall labor force will be established for the train

ing programs.7 This quota is expected to be used indef

initely to assure perpetual "minority representation in

the plant that is equal to that representation in the

community work force population."8

Apart from the racial quota imposed by Kaiser and

USWA, the sole qualification for entry into the train

ing programs is the seniority of applicants.9 This

seniority is determined on the basis of "length of

employment at the plant and is not affected by

departmental or job seniority. All workers at the plant

are included in this seniority line."10

6 Brief for Petitioner, Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corpora

tion in No. 78-435 (hereinafter cited as "Brief of Kaiser") at 52-53

n.135, Exhibit A.

7 App., 69.

8 App., 69. This statement was made by Dennis E. English, in

dustrial relations superintendent at the Gramercy plant. He also

said:

Once the goal is reached of 39 percent, or whatever the

figure will be down the road, 1 think it's subject to change,

once the goal is reached in each of the craft families, at

that time, we will then revert to a ratio of what that

percentage is, if it remains at 39 percent and we attain 39

percent someday, we will then continue placing trainees

in the program at that percentage. ^ ^

9 App., 73-74, 127.

10 App., 128.

Respondent, Brian F. Weber, was employed as a lab

analyst at the Gramercy works of Kaiser. In April,

1974, company bids for the on-the-job training

programs in the instrument repair, general repairman

and electrician craft categories were posted by Kaiser.11

Pursuant to the standard procedure of Kaiser and

USWA, applicants were to be selected for those

programs on the basis of seniority.12 Howrever, a condi

tion of the bid was that at least half of the persons

selected as prospective trainees would be applicants

who were members of minority groups.13 Thus,

applicants for the training programs were selected

from racially separated seniority lines. Selection was

made one-for-one "on the basis of their seniority,

within respective groups of bidders from their race."14

Mr. Weber and other white members of the plaintiff

class applied for the training programs. However,

members of minority groups with less seniority than

white employees were selected preferentially by Kaiser

for these programs to meet the established quota of at

least 50 per cent minority representation.15 In each in

stance of selection of a minority applicant, one or more

11 App., 127.

12 App., 73-74, 127.

13 App., 127.

14 App., 127.

15 App., 127-28. One black trainee and one white trainee were

selected for the instrument repair training program, one black

trainee and one white trainee were selected for the electrician

training program, and three black trainees and two white trainees

were selected for the general repairman training program. App.,

127-28.

5

6

white workers with greater seniority than members of

minority groups selected for the training programs

were denied entry into the training programs solely on

the basis of the racial criterion.16

Subsequently, company bids were posted for ad

ditional craft training openings in the air conditioning

mechanic, 17 insulator and carpenter categories.18 The

selections for these openings were made on the basis of

the 50 per cent minority requirement. One of the bids

barred applications by any white employee, as the bid

was specifically limited to minority employees only.19

In all, in the period April through October, 1974, seven

minority employees were selected for positions in

training programs in preference to white employees

pursuant to the 50 per cent quota.20

2 . Desirability of the craft positions.

The craft training programs offered by Kaiser

presented significant opportunities to the unskilled

workers at the plant. For years, USWA had negotiated

16 App., 127-28.

17 App., 127. This bid was posted on May 7,1974. A white bidder

with senior status was selected for this training program; this

selection re-established a 50-50 racial balance in the training

programs.

18 App., 127. One black trainee and one white trainee were

selected for the carpenter training program and one black trainee

was selected for the insulator training program. App., 127-28.

19 App., 46, 128.

20 App., 128.

to obtain the opportunity for its members to obtain

craft training.21 Entry into the training programs

would provide the opportunity for a worker to "better

[himself] financially"22 by obtaining better hourly pay

and overtime wages.23 In addition, the benefits

associated with being a craftsman are greater than for

unskilled jobs, including the opportunity primarily to

work the day shift.24 Mr. Weber and other workers also

perceived the craft positions to be desirable to provide

job security.25 Mr. Weber said there is "much more job

security as a craftsman than any other job."26

The craft jobs available at the Gramercy plant re

quired heavy industrial skills that are acquired only

after substantial training and schooling.27 In the crafts

generally in the United States, the necessary skills are

acquired only after apprenticeship programs lasting up

to five years.28 Many apprenticeship programs are

registered with state apprenticeship councils or the

Bureau of Apprenticeship and Training of the Depart

ment of Labor.29 These programs must identify certain

21 App., 64, 85.

22 App., 33.

23 App., 33.

24 App., 33.

25 App., 33, 129.

26 App., 33. The parties stipulated that craft jobs “are considered

desirable and advantageous for financial, job security and other

reasons." App., 129.

27 App., 67.

28 See, e.g., The National Apprenticeship Program (U.S. Dept,

of Labor, Employment and Training Admin., Rev. 1976).

29 Id. at 4.

7

8

minimum standards to be met, including a guarantee of

equal opportunity, work processes to be used in on-

the-job training, planned related instruction, proper

evaluation and supervision, and a "term of apprentice

ship that is consistent with training requirements as

established by industry practice . . . ,"30

The craft positions at the Gramercy plant required

special skills necessary for the performance of duties in

the heavy industrial setting.31 The electrical circuitry

carrying high voltages, potentially dangerous in

dustrial chemicals, large and complex industrial equip

ment and machinery, and sensitive meters and in

dicators require specialized knowledge and training to

adequately and safely perform the necessary tasks.32 In

the training programs at issue in this case, Kaiser

provides two and one-half to three and one-half years

of on-the-job heavy industrial training and about "four

hours of schooling per week by a training super

visor."33 In addition, the company requires each trainee

to take and pass from 40 to 66 home courses provided

30 Id. at 5.

31 As a result, Kaiser required prior heavy industrial experience

for new hires. App., 70.

32 Kaiser maintains job descriptions for each of its craft

positions. A sample "primary function" is that of the instrument

repairer:

To layout wiring, inspect, install, test, repair, service,

maintain, and wire plant indicating and recording, in

struments, meters, high voltage protective devices,

gauges, relays, thermometers and pyrometric equip

ment.

33 App., 67.

by the International Correspondence School.34 Thus,

the training programs provide a concentrated course of

study and training for employment in the industrial

crafts.

3. Impact on the white workers.

The effect of the racial quota instituted by Kaiser and

USWA was to create separate black and white seniority

lines for entry into the training programs. As stated by

Dennis E. English, industrial relations superintendent

at the Gramercy plant, "in effect [separate seniority

lines are created] because you skip the whites to get the

blacks, if necessary."35 In many cases, black bidders

were selected despite substantially greater seniority

held by white bidders. One white employee who testi

fied that he was denied entry into the training

programs, Fortune H. Maurin,36 possessed more than

16 years seniority at the time of the trial.37

The effect of the 50 per cent quota was to alter the

traditional criterion, seniority, for entry into the craft

training programs.38 Because proportionately more

white workers than minority workers are employed at

the Gramercy plant and have obtained senior status, a

34 App., 67.

35 App., 75.

36 Mr. Maurin's name is incorrectly spelled "Moran" in the trial

transcript, but appears correctly as F. H. Maurin in the exhibits.

App., 54-59, 156-64.

37 App., 54.

38 App., 101.

9

10

50-50 racial quota deprives whites of their seniority

rights.39 Thomas M. Bowdle,40 director of equal oppor

tunity affairs of Kaiser, conceded this point. He said:

Q. So, you recognized that when you

waive the number one requirement, the

seniority requirement, and you take a black

with less seniority than a white, you're

thereby favoring the black on grounds of race,

is that right?

A. He's getting preferential treatment,

that's correct.41

Mr. Bowdle also conceded that “the black is being

selected for a program primarily on the basis of his

race."42

The racial quota instituted by Kaiser and USWA, and

the perceived effect of race discrimination, had a sub

stantial impact on the white workers of the plant. A

“sacred"43 and objective criterion for advancement and

opportunity, seniority, was devalued by the factor of

race.44 Mr. Bowdle stated that there is “no question"

that the racial quota “gives . . . minorities, special

seniority rights, at the expense of white workers hired

39 App., 75, 101-02.

40 Mr. Bowdle's name is incorrectly spelled "Bouble" in the

transcript.

41 App., 101-02.

42 App., 102.

43 App., 99.

44 App., 99, 102.

11

earlier."45 In addition, Mr. Weber indicated that the

racial quota had a significant impact on white workers

and resulted in adverse consequences.415 Mr. Weber had

"been involved with the Union for several years as a

trustee [and] as a grievance committee man"47 and was

"presently chairman of the grievance committee."45

His responsibilities included dealing "with all the hour

ly people on the plant site . . . with their problems in

regard to any contractual violations or other problems

they might have."49 His familiarity with the attitudes

of the hourly employees was not challenged.

Mr. Weber stated that "the quota system used by the

company has had a very bad effect on the white

workers at the plant."50 One negative impact of the 50

per cent quota was a deterioration in racial harmony.

Mr. Weber stated:

[T]he racial relations of the white workers

tow ard their black counterparts, black

employees at Kaiser, have progressively

gotten worse because of the fact that they

realize that the company and the Union have a

program in effect which uses race to promote

employees ahead of themselves.51

45 App., 105

46 App„ 36.

47 App., 35.

48 App., 35.

49 App., 35.

50 App., 36.

51 App., 36.

12

Mr. Weber also stated that "the [white] employees feel

that the company and the Union are working against

them, not for them, in advancement and promotions to

jobs that they might better themselves. They feel that

they're being held back."52 He indicated that the racial

quota substantially diminishes the loyalty of white

workers to Kaiser and USWA and their desire to be

productive. He said:

[I]t takes away from the initiative of the in

dividual employee to do more, to do one step

further, to do all of his job in the best way he

knows how, because he knows that even no

matter how well he does it, he won't be able to

be promoted, because of this 50 percent

minority requirement of the company.53

4. Reasons for the adoption of the racial

quota.

The primary reason for the adoption of the 50 per

cent quota for selection into the craft training

programs was the small percentage of minority

workers in craft jobs as compared with the minority

labor force as a whole.54 Prior to the institution of the

training programs under the 1974 agreement, only

about two per cent of the craftsmen at the Gramercy

plant were minority employees.55 According to Mr.

52 App., 36.

53 App., 37-38.

54 App., 62-64, 137.

55 App., 62, 167.

13

English, Kaiser and USWA were "striving to obtain . . .

a 39 per cent minority population in each of the craft

families . . . ."56 The one-for-one hiring program was

the means adopted to achieve this goal.

Kaiser was motivated to adopt the 50 per cent quota

in part because of its perception of the wishes of federal

contract compliance officers.57 However, Kaiser was

not ordered to implement this action.58 Kaiser had a

substantial economic reason to comply with federal

contract compliance suggestions.59 In addition, Kaiser

believed that it was furthering a national social policy

by the adoption of the racial quota.60

USWA appears to have concurred in the adoption of

the racial quota as an affirmative action measure.61

However, USWA had negotiated for years for the in

stitution of training programs to provide its members

with access to craft jobs.62 In the words of the attorney

for USWA, "the Union's efforts were directed towards

obtaining additional opportunities for their members,

56 App., 60.

57 App., 83, 92-93.

58 App., 84.

59 App., 77.

60 App., 95. The district court indicated that the racial quota was

also adopted to avoid "vexatious litigation," but there was no

evidence that any black employees had threatened suit based on

the makeup of craft positions at the Gramercy plant. 415 F.Supp.

at 765. The agreement was adopted for a number of plants, some

of which may or may not have been potential litigation targets.

61 See Petition for a Writ of Certiorari filed on behalf of USWA

in this Court, No. 78-432.

62 App., 73.

14

who were also Kaiser employees, as opposed to creat

ing opportunities for people from the street."63 Thus,

the training programs were instituted to benefit union

members, and were not solely an affirmative action

measure having incidental benefits for white as well as

black workers.

The racial quota was not implemented by Kaiser and

USWA to remedy past discrimination, but instead was

designed to help uplift the employment status of

minority workers as a class.64 65 The program was part of

a national plan to compensate for the unavailability of

minority craftsmen of the type employed by Kaiser.66

As stated by USWA in its brief,66 "[t]he program was

negotiated without regard to specific conditions at any

one plant, and certainly was not based on an assess

ment of the particulars of the situation at the Gramer-

cy plant."67 Kaiser believed that it had not discrim

inated against minority workers at the Gramercy

plant.68 Instead, Mr. Bowdle indicated that the racial

quota was necessitated by the adverse impact on

minorities of general societal discrimination.69 Mr.

Bowdle stated that "past discrimination in the field of

education, job training, et cetera, has created the condi

tion that we have to deal with in terms of minority

63 App., 85.

64 Opinion of the district court, 415 F.Supp. at 765.

65 App., 92-94, 99-100.

66 Brief for Petitioner, United Steelworkers of America, AFC-

CIO-CLC (hereinafter cited as "Brief of USWA").

67 Id. at 5.

68 App., 108, 99.

69 App., 99-100.

15

craftsm en."70 These factors, according to Mr. Bowdle,

have also led to low minority ratios "for lawyers, for

doctors, for engineers."71

While Kaiser believed on the basis of the "sum total

of our experience"72 that the class of blacks generally

has suffered societal discrimination, no effort was

made to identify any individual subjected to societal

discrimination.73 To the extent that the racial quota

was designed to rectify past discrimination as well as

to achieve a desired statistical ratio, it was based on an

assumption concerning minority classes rather than

any evidence as to individuals.74 75 Indeed, Mr. Bowdle

indicated that some blacks may not have suffered

societal discrimination, while some whites may have

endured this hardship.73 In this case, the whites whose

seniority rights were diluted under the racial quota

were no better off than the preferred blacks in terms of

craft-preparedness because "all of the whites who were

passed over lacked the skills that the blacks lacked."76

Kaiser did not believe that any of the individuals

preferred under the racial quota were ever subjected to

employment discrimination by Kaiser.77 The 50 per

70 App., 99-100.

71 App., 100.

72 App., 100.

73 App., 100.

74 App., 100.

75 App., 101.

76 App., 101.

77 App., 99.

16

cent quota was implemented "to increase the repre

sentation of minorities [in the crafts] that will ap

proximate the participation in the labor market. . . ,"78

5. Availability of minority craftsmen.

Although the percentage of minority craftsmen at

the Gramercy plant was smaller than the minority

representation in the labor force overall, it was not

smaller than the percentage of skilled heavy industrial

craftsmen in the Gramercy area. The evidence estab

lished that "[t]he available supply of trained craft and

trade personnel available for hire by the company as

new employees has been, and remains to the present

time, almost entirely made up of white males."79 Mr.

English said that craftsmen with heavy industrial skills

were not available: "Once again, we can advertise all we

want, and look as hard as we can look, and they just

aren't available."80 He agreed that there might be "as

little as one or two per cent minority craftsmen in St.

James and St. John's parrishes (sic)."81 Mr. Bowdle

stated that the availability of skilled craftsmen was

"minimal" and, with ordinary minority recruitment

measures, Kaiser would "end up baying at the moon, as

it were."82

78 App., 105

79 App., 126

80 App., 63.

81 App., 76.

82 App., 93.

17

The means adopted by Kaiser to increase the percen

tage of minority craftsmen at the Gramercy plant were

expensive. The minimum cost of the program of on-

the-job training, classroom instruction and home study

was $15,000 to $20,000 per trainee per year.83 Had

minority craftsmen been available in the work force at

large, Kaiser could have increased the ratio of minority

craftsmen at the plant without this cost. Mr. Bowdle

stated:

Q. Now, sir, on a pure economic basis,

what would be the cheapest procedure, on the

pure cost approach, for obtaining qualified

craft employees at the various Kaiser plants?

A. Hire them off the street. If we had ade

quate supply of craftsmen, candidates coming

off the street, that would be the logical way

for us to fill our craft jobs, rather than train,

because training costs money.84

Prior to the institution of the racial quota, Kaiser

tried a number of affirmative action methods to attract

minority craftsmen. The company set goals and

timetables to increase the percentage of minorities in

the crafts.85 In addition, it advertised "in minority-only

newspapers" and maintained separate craft application

f ile s .86 According to the industrial relations

83 App., 67-68.

84 App., 95.

85 App., 62.

86 App., 62.

18

superintendent, "any time the craft vacancies comes

up, our first thing, we will go to that craft file and we

will try to locate qualified black craftsmen, and we

always look for the blacks before the whites. . . ,"87

However, the few minority craftsmen in the area were

already employed "because companies like Kaiser

anywhere are hiring blacks first, or they're attempting

to get blacks on the payroll."88 The quota was insti

tuted because "the officials of both Kaiser and the

Steelworkers realized that something other than the

ordinary, look until you find them, had to be done to get

blacks into the crafts."89

6. Absence of prior discrimination.

The seniority criterion for entry into training

programs is based on the date of hire at the plant and is

applicable to all employees.90 Promotional decisions at

the Gramercy plant were never based on race.91 Deter

minations of seniority for selection into training

programs are based on "length of employment at the

plant."92 The Gramercy plant of Kaiser was opened in

1957 or 1958 and discrimination against blacks in hir

ing has never occurred at this plant.93 Some "very

senior black employees that were hired in and started

87 App., 62-63.

88 App., 63.

89 App., 64.

90 App., 72.

91 App., 72-73.

92 App., 128.

93 App., 77-78.

19

the plant in 1957-58" have obtained "pretty highly paid

top jobs in the plant. . . ,"94

The district court found that the quota adopted by

Kaiser and USWA was not implemented "with a view

tow ard correctin g the effects of prior dis

crimination."95 In addition, it found:

The evidence further established that Kaiser

had a no-discrimination hiring policy from the

time its Gramercy plant opened in 1958, and

that none of its black employees who were

offered on the job training opportunities over

more senior white employees pursuant to the

1974 Labor Agreement had been the subject

of any prior employment discrimination by

Kaiser.96

In the district court USWA contended that the

statistical showing of a low ratio of minority workers in

craft jobs was sufficient to make out a case of past dis

crimination.97 This contention was rejected by the dis

trict court on the basis of all the evidence.98 The court

of appeals upheld this decision, specifically quoting and

approving the finding of the district court that the low

percentage of minority craftsmen did not establish past

94 App., 71.

95 415 F.Supp. at 765.

96 415 F.Supp. at 764.

97 Post-Trial Brief of Defendant, United Steelworkers of

America AFL-CIO.

98 415 F.Supp. at 764.

20

discrimination." In the court of appeals, USWA argued

that certain training programs of Kaiser existing prior

to 1974 that required prior experience may have been

discriminatory because minorities lacked this ex

perience.99 100 However, a disparate impact of the re

99 415 F.Supp. at 764; 563 F.2d at 224.

100 Prior to the institution of the training programs involving

no prior experience requirement in 1974, Kaiser filled its craft

positions primarily by hiring fully trained craftsmen from outside

the plant. App., 65. However, pursuant to the efforts of USWA to

open craft jobs to union members within the plant, Kaiser institut

ed two partial training programs prior to 1974 in which persons

with previous experience were accepted and trained. App., 64-65,

126. The training programs involved acceptance of persons with

experience of one year in the carpenter-painter craft from 1964

until 1971, acceptance of applicants with three years experience in

the general repairman category from 1968 until 1971, and selec

tion of persons with two years experience in the general repair

man craft from 1971 until 1974. App., 126.

In these training programs involving selection of employees

with prior experience, it was necessary only for Kaiser to provide

training to the employee for the balance of training he did not

have. App., 64-65. Thus, the general repairman training program

into which employees with three years experience were selected

lasted two years; when this program was modified for selection of

applicants with two years experience, the training program was

lengthened to three years. App., 126. The minimum cost to Kaiser

of each year of training, for each trainee, was $15,000 to $20,000.

App., 68.

Of 292 craft employees at Kaiser in 1975, only 28 entered

through the prior experience training programs. App., 126. These

training programs were open to members of minority groups as

well as whites with the requisite experience. App., 126. Of the 28

persons who completed the prior experience training programs

during their 10 year existence, seven per cent were black. App.,

126. This percentage is identical to the ratio of black bidders with

no prior experience in the top 28 positions of seniority at the time

of the institution of the training programs at issue in this case.

App., 156.

21

quirement could not be shown101 and the district court

implicitly found the prior experience requirement to be

business related.102 In addition, the court of appeals

held these programs "so limited in scope that the prior

craft experience requirement cannot be characterized

as an unlawful employment practice, especially when

Kaiser was actively recruiting blacks to its craft families

during the same period."103 Thus, both courts found

that Kaiser had not discriminated against blacks at the

Gramercy plant.

The dissenting judge in the court of appeals, the Hon.

John Minor Wisdom, contended that "arguable

violations" of Title VII existed, but indicated that

"Kaiser did act in good faith [and] made admirable

attempts to recruit black craftsmen."104 In addition, he

conceded that "the three potential violations discussed

above may not make the district court's finding [of no

discrimination] 'clearly erroneous' in the sense con

templated by Rule 52(a), F.R.C.P. . . ,"105

No party contends that the minority workers

preferred under the racial quota are identifiable victims

of any past discrimination.

101 See n. 100 supra.

102 See 563 F.2d at 232 (Wisdom, dissenting).

103 Id. at 224 n. 13.

104 Id. at 232.

105 Id. at 232.

22

7. Procedural background.

This case was filed December 31, 1974 after the

issuance of a righ t-to-sue letter by the New Orleans of

fice of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion ("EEOC")-106 The national office of the EEOC

became aware of the case almost immediately and,

prior to the filing of answers by Kaiser and USWA, a re

quest was made by an EEOC staff attorney for copies of

the pleadings filed by Mr. W eber.107 Every important

pleading filed by the plaintiffs was sent to this at

torney.108 Copies of the stipulation and six of the seven

exhibits were also provided to the EEOC.109 The EEOC

staff attorney discussed the case with counsel for each

party.110 Despite its knowledge of and interest in the

case, the EEOC determined not to intervene at the dis

trict court level.

The suit of Mr. Weber was filed and certified as a

class action.111 Pursuant to the order of the district

court, the Approved Form of Notice was required to be

106 The right-to-sue letter was filed in the district court.

Counsel was asked by the district court to investigate the charge

and institute suit if appropriate. Thereafter, counsel was formally

appointed by the district court to represent Mr. Weber. See App.,

107 See Brief for Respondents in Opposition to the Petition for

Writs of Certiorari at 5.

108 Id. at 5-6.

109 Id. The relevant portion of the seventh trial exhibit was con

tained in the stipulation.

110 App. 30-31.

111 App., 24.

23

posted "on all employee bulletin boards at the Gramer-

cy, Louisiana works . . . and at the Union Hall [of

USWA]."112 The Approved Form of Notice stated in

part that the suit "alleges that the selection policies of

the defendants for [on-the-job] training programs,

which require the selection of minority applicants to fill

at least fifty percent of the available vacancies in the

training programs, constitute race discrimination [in

violation of Title VII and 42 U.S.C. §1981],"113

Although the trial lasted only one day, a large

amount of statistical data submitted by Kaiser was

stipulated into evidence by the plaintiffs and other facts

were also stipulated.114 A substantial portion of the

trial was devoted to reviewing the past employment

practices of Kaiser and the reasons for the low percen

tage of minority craftsmen.115 The case was under ad

visement in the district court for more than 14

months.116 The district court ruled in favor of the

plaintiffs, holding that the racial quota violated the

112 App., 25.

113 R., Equal Employment Opportunity in Selection for On-the-

Job Training Programs, Approved Form of Notice. Fifth Cir. App.,

35. This notice was omitted from the Appendix in this Court.

114 App., 124 et seq.

115 See text at nn, 90-105 supra.

116 The opinion of the district court was issued June 17,1976.

24

rights of white employees under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964.117

The court of appeals affirmed,118 holding that "[i]t is

undeniable that the 1974 Labor Agreement's one-for-

one ratio for training eligibility discriminates on the

basis of race."119 The court held that while remedial ac

tion designed to correct past discrimination by the

employer and restore employees to their "rightful

place" is permissible under Title VII, racial preferences

are not.120 The court of appeals concluded:

Where admissions to the craft on-the-job

training programs are admittedly and purely

functions of seniority and that seniority is un

tainted by prior discriminatory acts, the one-

for-one ratio, whether designed by agreement

between Kaiser and USWA or by order of

court, has no foundation in restorative justice,

117 415 F.Supp. at 769-70.

118 563 F.2d 216. The Hon. John Minor Wisdom dissented from

the decision.

119 563 F.2d at 223.

120 Id. at 225.

25

and its preference for training minority

workers thus violates Title VII.121

8. Published posture of the Government.

The United States and the EEOC (collectively

referred to as "the Government"), petitioners, support

Kaiser and USWA in this case and contend that the

racial quota is valid as a "remedy" for "apparent"

violations of Title VIE122 This position is asserted to be

consistent with the current posture of the EEOC under

its affirmative action guidelines.123 In light of this con

tention, a brief review of the published affirmative ac

tion posture of the Government is appropriate.

The affirmative action guidelines124 were published

by the EEOC in an effort to insulate employers from

liability to white employees for preferences enacted in

favor of minority workers under affirmative action

programs.125 The guidelines were assertedly

121 Id. at 226. After the decision of the court of appeals, the

United States and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

which had participated at the appellate level as amici curiae, moved

for and were granted permission to intervene as parties. The

appellants petitioned for rehearing and suggested rehearing en

banc. These petitions were under consideration for more than

three months, but were denied on April 17, 1978. 571 F.2d 337.

122 Brief for the United States and The Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission (hereinafter cited as "Brief of the Govern

ment") at 35-42.

123 Brief of the Government at 40-41.

124 29 C.F.R. Part 1608 (1979).

125 29 C.F.R. §§1608.1, 1608.2 (1979).

26

promulgated pursuant to Section 713(b) of Title VII,126

which provides that no person shall be subject to liabili

ty in "any action or proceeding based on any alleged un

lawful employment practice . . . if he pleads and proves

that [he acted] in good faith, in conformity with, and in

reliance on any written interpretation or opinion of the

Commission. . . ."127

The guidelines require a "reasonable basis" for the

preferences granted under the affirmative action

plan.128 However, a reasonable basis does not require

an apparent or even arguable violation of Title VII.129

Indeed, "[i]t is not necessary that the self-analysis es

tablish a violation of Title VII, This reasonable basis ex

ists without any admission or formal finding that the

person has violated Title VII, and without regard to

whether there exist arguable defenses to a Title VII ac

tion."130 The affirmative action is "appropriate"

whenever there has been an actual or potential adverse

impact on minorities of business practices, when there

is a disparity in the minority ratio between the

"employer's work force, or a part thereof, and an ap

propriate segment of the labor force," or when there is

limited availability of minority workers in the labor

pool.131

126 42 U.S.C. §2000e-12(b) (1976).

127 Id. §2000e-12(b)(l).

128 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(b).

129 Id.

130 Id.

131 29 C.F.R. §1608.3 (1979).

The employer is specifically authorized to find a

reasonable basis for instituting preferences under the

technique set forth in Revised Order No. 4 of the Of

fice of Federal Contract Compliance ("OFCC").132 This

order requires affirmative action whenever

"underutilization" is found in any job group.133

Underutilization means "having fewer minorities or

women in a particular job group than would reasonably

be expected by their availability."134 In its utilization

analysis, the contractor must consider not only the

availability of minorities having the requisite skills in

the work force, but also the minority population in the

labor area, the size of the minority unemployment

force in the labor area, the percentage of the minority

work force as compared with the total work force, and

other factors.135

If underutilization exists, the employer must estab-

lishs "goals" that are "specific for planned results" and

must meet the goals within designated timetables.136 A

contractor that fails to comply with OFCC re

quirements may be subjected to loss of its federal con

tracts, debarment from future federal contracts and

other penalties.137

The "reasonable action" deemed appropriate under

the affirmative action guidelines includes "goals and

132 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(a) (1979); 41 C.F.R. Part 60-2 (1978).

133 41 C.F.R. §60-2.11(b) (1978).

134 Id.

135 Id.

136 41 C.F.R, §60-2.12.

137 Executive Order 11246, Subpart D, §209.

27

28

timetables or other appropriate employment tools

which recognize the race, sex or national origin of

applicants or employees."138 Actions adopted in com

pliance with Revised Order No. 4 will receive the ap

proval and protection of the EEOC guidelines.139

Preferences may be provided to minority workers or

women "regardless of whether the persons benefitted

were themselves the victims of prior policies or

procedures which produced the adverse impact or dis

parate treatment or which perpetuated past dis

crimination."140 141

The affirmative action guidelines were issued on

December 11, 1978, the same day that certiorari was

granted in this case. The EEOC denied any conflict

between the guidelines and the decision of this Court in

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, b e c a u s e in

Bakke "the university did not assert reliance on any

detailed guidance and procedures for crafting an affir

mative action plan."142 The EEOC recognized the con

flict between the decision of the Fifth Circuit in this

case and the guidelines. Rather than deterring the

EEOC from issuing the guidelines, however, the deci

sion of the Fifth Circuit was deemed to make them all

138 29 C.F.R. §1608.4(c).

139 29 C.F.R. §1608.5.

140 29 C.F.R, §1608.4(c).

141 ------U.S---------, 98 S.Ct. 2733 (1978).

142 Supplementary Information, Guidelines on Affirmative Ac

tion, CCH Employment Practices Guide II 4011.11. The implica

tion of this statement, of course, is that reliance on these or similar

guidelines could have changed the decision of the Court in Bakke.

29

the more necessary: "[T]he clarification provided by

these Guidelines is necessary because the Weber deci

sion may be interpreted to unduly interfere with the

range of affirmative action which Congress intended to

permit under Title VII."143

ARGUMENT

Summary of Argument

1. Regardless of the benign and appealing phrases

used by the Government, Kaiser and USWA to describe

the 50 per cent racial quota,144 the operation of the

quota presents a classic case of race discrimination

against whites. The white workers at the Gramercy

plant were denied valuable employment opportunities

solely on the ground of race. The 50 per cent quota re

quired the selection of minority applicants over white

applicants with greater seniority. This selection system

in effect created two separate lines of seniority based

on race, artificially diluted the seniority rights of white

workers, and required the selection of a greater percen

tage of minority workers for training programs than

the percentage of minority workers employed at the

plant. Therefore, the 50 per cent quota is an open and

intentional policy of discrimination against white

workers.

143 Id.

144 E.g., Kaiser describes the racial quota as "voluntary race

conscious action." Brief of Kaiser at 30. The Government

describes the training programs as "race-conscious training

programs." Brief of the Government at 36.

30

2. Employment discrimination against white

workers is just as illegal under Title VII as discrimina

tion against minority employees. Title VII was passed

by Congress to prohibit all forms of racial bias in

employment. The decisions of this Court and the

legislative history of the statute establish that racial

quotas of any kind are illegal. These authorities are

consistent with the constitutional decisions of this

Court, which establish that the reverse racial quota im

plemented by Kaiser and USWA would be un

constitutional if imposed by the Government.

3. The contentions raised in support of the dis

criminatory racial quota have no merit. No "apparent"

past discrimination existed in this case. No effort was

made by Kaiser or USWA to identify any past dis

crimination. The sole purpose of the 50 per cent quota

was to achieve the same ratio of minority workers in

the crafts at the Gramercy plant as the ratio of minority

employees in the local labor force. A racial preference

imposed to achieve a ratio of minority workers in

designated jobs, even if this ratio is deemed socially

desirable by corporate or union executives or govern

ment officials, is a violation of Title VII.

4. The claims that Kaiser had a reasonable basis to

believe that past discrimination had occurred are

without merit. Kaiser did not enact the racial quota as a

remedy" for past discrimination. Moreover, the low

percentage of minority craftsmen at the Gramercy

plant was not due to discrimination by Kaiser, but to

31

the unavailability of minority craftsmen with the req

uisite skills in the labor force. Kaiser tried a number of

affirmative action measures to increase the ratio of

minority craftsmen at the plant, but these craftsmen

were not available. Furthermore, the speculation as to

an arguable or potential discriminatory effect of the

prior experience requirement for craftsmen at the

Gramercy plant is invalid. The prior experience re

quirement was neutral on its face and business related.

No suggestion has been made of any basis for question

ing the business necessity of the prior experience re

quirement. Kaiser did not believe that the prior ex

perience requirement was invalid in any way, and this

requirement was not a justification for the institution

of the racial quota.

5. To the extent that Kaiser and USWA believed

the 50 per cent quota to be remedial, the "remedy" was

for discrimination believed to have been practiced by

society at large against the various classes of

minorities, not against individuals. No attempt was

made to provide a "remedy" to any individual victim of

discrimination by Kaiser. None of the individuals

preferred under the racial quota was ever subjected to

employment discrimination by Kaiser. No attempt was

ever made to determine whether any of the preferred

minority employees had suffered discrimination at the

hands of society. The racial quota embodied a policy of

race discrimination against white individuals to achieve

the general advancement of minority classes. This

policy is unlawful under Title VII.

32

6. The legislative history of Title VII does not

demonstrate an intent to permit the voluntary enact

ment of racial quotas by private parties to achieve the

advancement of minority groups. This interpretation

of USWA is drawn from a strained reading of the

repeated and vigorous denials of the sponsors of Title

VII that the statute would require quotas. The negative

inference of USWA is inconsistent with the express

prohibition of any race discrimination in the statute,

the decisions of this Court, and other statements of the

sponsors of Title VII.

7. The discrimination against white employees can

not be validated by the executive orders requiring affir

mative action by government contractors. To the ex

tent that the executive orders and the affirmative ac

tion regulations of the OFCC conflict with Title VII,

the statute prevails. An affirmative action practice that

overtly discriminates against non-minority employees

is neither reasonable nor legal. In addition, a training

program that discriminates on the basis of race is not

valid simply because it provides opportunities to the

disadvantaged class as well as the preferred class.

8. The racial quota of Kaiser and USWA carries

significant adverse consequences. Advancement of

minorities solely on the basis of race injures innocent

non-minority workers and may lead to increased racial

animosity. Moreover, this policy could enhance

stereotyped beliefs about minority employees held in

the society at large. Furthermore, policies of advance-

33

merit of employees that are unrelated to qualifications

or ability may undermine the incentive of employees to

be productive. In addition, the "zone of reasonable

ness" rule proposed by Kaiser and the Government

may have uncontrollable and undesirable conse

quences. judicial approval of a rule permitting dis

criminatory treatment of white workers could lead to

resentment among whites of the entire equal rights

movement. In addition, if the rule were applied even-

handedly, it could require the judicial approval in the

future of programs that discriminate against minority

workers, when the discriminatory programs are alleg

ed to be "remedies" for past disparate treatment of

white employees under affirmative action programs.

The long term objective of racial equality will not be

served by a program that spurs the advancement of

minorities only by denying opportunities to whites.

I. The Racial Quota Imposed By Kaiser And

USWA Is Illegal Under Title VII Because

It Discriminates Against Non-Minority

Employees.

The 50 per cent minority quota of Kaiser and USWA

is an openly discriminatory system of selection of

applicants for on-the-job training programs. The selec

tion quota requires that minority employees be favored

over more senior white employees solely on the basis of

race. Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

the authorities interpreting this statute, the reverse

racial quota is illegal.

34

A. Race Discrimination Against Any Employee Is

Prohibited Under Title VII, Whether or Not the

Employee Is a Member of a Government-

Recognized Minority Group.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 specifically

prohibits discrimination in employment against anyone

on the basis of race.145 Section 703(a) of Title VII

prohibits an employer from discriminating "against

any individual with respect to his compensation, terms,

conditions, or privileges of employment, because of

such individual's race, color, religion, sex or national

origin."146 Moreover, Section 703(d) prohibits dis

crimination on grounds of race in the selection of

applicants for training programs. It states:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for any employer, labor organization, or joint

labor-management committee controlling ap

prenticeship or other training or retraining,

including on-the-job training programs to dis

criminate against any individual because of his

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in

admission to, or employment in, any program

established to provide apprenticeship or other

training.147

Section 703 makes no exception for discrimination

145 42 U.S.C. §2000(e) et seq.

146 Id. §2000(e)-2(a).

147 Id. §2000(e)-2(d).

35

against white employees. In fact, the categorical

prohibition of any racial discrimination establishes that

Title VII prohibits discrimination against white

workers as well as minority employees. Thus, the racial

quota of Kaiser and USWA violates the provisions of

Title VII.

Our reading of Title VII is consistent with the

decisions of this Court. In McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transportation Co.,148 the Court ruled that white persons

may assert claims under Title VII and the same stan

dards that are used in cases brought by minority

employees are applicable to the claims of whites.149 The

Court stated:

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

prohibits the discharge of "any individual"

because of "such individual's race." Its terms

are not limited to discrimination against

members of any particular race. . . .

This conclusion is in accord with uncon

tradicted legislative history to the effect that

Title VII was intended to "cover all white men

and white women and all Americans," and

create an "obligation not to discriminate

against whites." We therefore hold today that

Title VII prohibits racial discrimination

against the white petitioners in this case upon

148 427 U.S. 273, 96 S.Ct. 2574 (1976).

149 427 U.S. at 278-80, 96 S.Ct. at 2578-79.

36

the same standards as would be applicable

were they Negroes and Jackson white.

(Citations omitted).150

The conclusion that whites are protected by Title VII

is also supported by the decision of the Court in Griggs

v. Duke Power Co.151 In Griggs, the Court held that tests

administered to determine selection for employment

that have a disproportionate adverse impact on minori

ty applicants must be job related. In reviewing the pur

pose and intent of Congress in adopting Title VII, the

Court stated:

Congress did not intend by Title VII, however,

to guarantee a job to every person regardless

of qualifications. In short, the Act does not

command that any person be hired simply

because he was formerly the subject of dis

crimination, or because he is a member of a

minority group. Discriminatory preference

for any group, minority or majority, is precise

ly and only what Congress has proscribed.

What is required by Congress is the removal

of artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary

barriers to employment when the barriers

operate invidiously to discriminate on the

ba sis of racial or other impermissible

classification.152

150 Id.

151 401 U.S. 424. 91 S.Ct. 849 (1971).

152 401 U.S. at 430-31, 91 S.Ct. at 853.

37

Thus, the Court's holding establishes that Title VII

outlaws preferences in favor of minority as well as non

minority employees.

In the decision last term in City of Los Angeles, Depart

ment of Water and Power v. Manhart,153 the Court in a sex

discrimination case stated that Title VII was "designed

to make race irrelevant in the employment market."154

The Court held that the policy of the statute requires a

focus on fairness to individuals, not fairness to

classes.155 In addition, the Court stated:

The statute makes it unlawful "to dis

criminate against any individual with respect to

his compensation, terms, conditions or

privileges of employment, because of such in

dividual's race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin." (emphasis added). The statute's focus

on the individual is unambiguous. It precludes

treatment of individuals as simply com

ponents of a racial, religious, sexual, or

national class. . . . (Citation omitted).156

In another decision rendered last term, Furnco Construc

tion Corp. v. Waters,157 the Court reiterated this principle.

It said: "It is clear beyond cavil that the obligation im

153 435 U.S. 702, 98 S.Ct. 1370 (1978).

154 Id. at 709, 98 S.Ct. at 1376.

155 Id.

156 Id. at 708, 98 S.Ct. at 1375.

157 _____ U.S. ___ , 98 S.Ct. 2943 (1978).

38

posed by Title VII is to provide an equal opportunity for

each applicant regardless of race, without regard to

whether members of the applicant's race are already

proportionately represented in the work force."158

The decisions of this Court establish the illegality of

the racial selection criterion used for the craft training

programs. The application of the racial quota creates a

preference in favor of a minority worker, to the detri

ment of a white, each time a selection is made of a

minority worker without the highest seniority status.

The 50 per cent quota creates two lines of seniority,

one for the preferred minority workers and one for

whites. For each person selected from the plant-wide

seniority line for the training programs, a person must

be selected from the seniority line of minority

employees. Applying the "same standards as would be

applicable"159 160 if separate seniority lines favoring whites

had been created, the racial quota is illegal under Title

Y U . 160

Our interpretation of Title VII is also supported by

the legislative history of the statute. This legislative

history is reviewed exhaustively in the Brief of USWA

and it is not necessary to present it in full in this brief.

As USWA suggests, the legislative history

demonstrates that the sponsors intended to prohibit

158 Id. at _ _ _ , 98 S.Ct. at 2951.

159 McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. at 280, 96

S.Ct. at 2579.

160 See, e.g., Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-

CIO, CLC v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969).

39

any requirement of a preference to achieve a racial

balance.161 In addition, this history establishes that

Congress intended to prohibit preferences in favor of

any race.162

The intent of Congress concerning Title VII is

demonstrated in the "Objections and Answers" sub

mitted by Senator Joseph S. Clark, a floor manager of

the bill. It states:

Objection: The bill would require

employers to establish quotas for nonwhites

in proportion to the percentage of nonwhites

in the labor market area.

Answer: Quotas are themselves dis

criminatory.163

The statement that "[q]uotas are themselves dis

criminatory"164 is supported by the observations of

other sponsors of Title VII. In response to the claim

that Title VII would allow the Commission to impose

quotas, Senator Hubert S. Humphrey stated:

[T]he very opposite is true. Title VII prohibits

discrimination. In effect, it says that race,

161 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(j); Brief of USWA at 25, 70-74.

162 McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transport Co., 427 U.S. 273, 280, 96

S.Ct. 2574, 2578-79 (1976).

163 110 Cong. Rec. 7218 (1964).

164 Id.

40

religion and national origin are not to be used

as the basis for hiring and firing. . . ,165

Senator Harrison A. Williams, Jr., another supporter of

the bill, stated that "[t]hose opposed . . . should realize

that to hire a Negro solely because he is a Negro is racial

discrimination, just as much as a 'white only' employ

ment policy."166 He added: "There is an absolute

absence of discrimination for anyone; and there is an

absolute prohibition against discrimination against

anyone."167

If any doubt as to the "color blind" meaning of Title

VII could have existed, it should have been erased by

the explanation of the bill submitted by Senator

Humphrey, which had been approved by the bipartisan

floor managers of the bill in both houses of Con

gress.168 It said:

The title does not provide that any

preferential treatment in employment shall be

given to Negroes or any other persons or

groups. It does not provide that any quota

systems may be established to maintain racial

balance in employment. In fact, the title would

prohibit preferential treatment to any par

ticular group, and any person, whether or not

165 Id. at 6549.

166 Id. at 8921.

167 Id.

168 Id. at 11846-48.

41

a member of any minority group, would be

permitted to file a complaint of discriminatory

employment practices. . . ,169

Thus, no hidden meaning exists in the statute. The ap

parent intent to prohibit any race discrimination is sup

ported by the legislative history.170

Contrary to the claims of Kaiser171 and the

Government,172 the rejection of proposed amendments

to Title VII in 1972 did not change the meaning or in

tent of the statute. Amendments proposed by Senator

Sam Ervin to prohibit quotas and goals were rejected in

the Senate, but this action does not suggest that the

Senate wished to approve preferential quotas. Based on

the language and legislative history of the statute,

Congress had every reason to believe that racial quotas

were already prohibited by Title VII. Although some

courts in special circumstances may have approved

numerical ratios in an effort to correct for past dis

crimination under Title VII,173 this Court had an

nounced in Griggs v. Duke Power Co, that "[dis

criminatory preference for any group, minority or ma

jority, is precisely and only what Congress has

169 Id . at 11848.

170 The legislative history is also reviewed exhaustively in Jersey

C en tra l P ow er & L ight C o. v. L ocal 3 2 7 , 1B E W , 508 F,2d 687 (3d Cir.,

1975) and W aters v. W iscon sin S teel W o rk s o f In te rn a tion a l H a rv es te r C o.,

502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir., 1974). Both courts drew the same con

clusions.

171 Brief of Kaiser at 34-35.

172 Brief of the Government at 31-35.

173 See Brief of the Government at 33.

proscribed."174 Thus, a system of racial quotas to

achieve numerical ratios was not believed to be

authorized under the statute.175 Moreover, the Senate

may have believed the Ervin amendments could under

mine the power of the courts to grant remedies to in

dividuals victimized by race discrimination. Further

more, the failure to take a proposed action in 1972 can

not provide a basis for interpretation of a bill passed in

1964.

42

In the House, Rep. John H. Dent proposed an anti

quota amendment to H.R. 1746, a bill designed to ex

pand the enforcement powers of the EEOC. Neither

the enforcement portion of the original H.R. 1746 nor

the Dent amendment ever was put to a vote.176 The

debate on the amendment, however, establishes the

understanding of the members of the House that

quotas and preferences were already prohibited under

Title VIE177 The amendment offered by Rep. Dent was

not intended to make any change in the substance of

Title VII, but only to make emphatic the prohibition of

174 401 U.S. 424, 431, 91 S.Ct. 849, 853 (1971).

175 See the discussion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit in Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO, CLC v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 995 (5th Cir., 1969):

"[Cheating fictional employment time for newly-fired Negroes

would comprise preferential rather than remedial treatment. The

clear thrust of the Senate debate is against such preferential treat

ment on the basis of race

176 A substitute for the enforcement provisions of H. R. 1746

was offered by Rep. John N. Erlenborn and was eventually passed

by the House.

177 See, e.g., 117 Cong. Rec. 31963.

43

preferences imposed by the government and quell the

fears of some House members concerning the potential

results of expanded EEOC enforcement authority.178

Rep. Augustus F. Hawkins, who spoke in favor of the

amendment, stated repeatedly that Title VII already

prohibited the use of quotas.179 He said:

Again some say that this bill seeks to es

tablish quotas and stop discrimination in

reverse. Not only does title 7 prohibit this, but

it establishes beyond any doubt a prohibition

against any individual white as well as black

being discriminated against in employment. It

only seeks to insure that persons will be

treated on their individual merits and in accor

dance with their qualifications. . . ,180

In addition, Rep. Gerald R. Ford, who supported the

substitute bill, indicated a belief that there was no

necessity to amend the law to prohibit quotas. He said:

The Philadelphia plan, which is what we are

really talking about, does not have anything to

do with quotas. I honestly think that the

gentleman from Pennsylvania is drawing a

false issue by the kind of language that he is

employing in his proposed amendment. I just

do not think that we ought to interfere with

178 117 Cong. Rec. 31964, 31965.

179 Id. at 31963, 31964.

180 Id. at 31963.

44

thi s pr o g r a m with this kind of

amendment. . . .181

Thus, the members of the House who spoke on the