Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Brief Amicus Curiae, 1970. bc253e3e-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5a7f6e3-9eed-4ecd-807e-4cdc215dceb7/phillips-v-martin-marietta-corporation-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

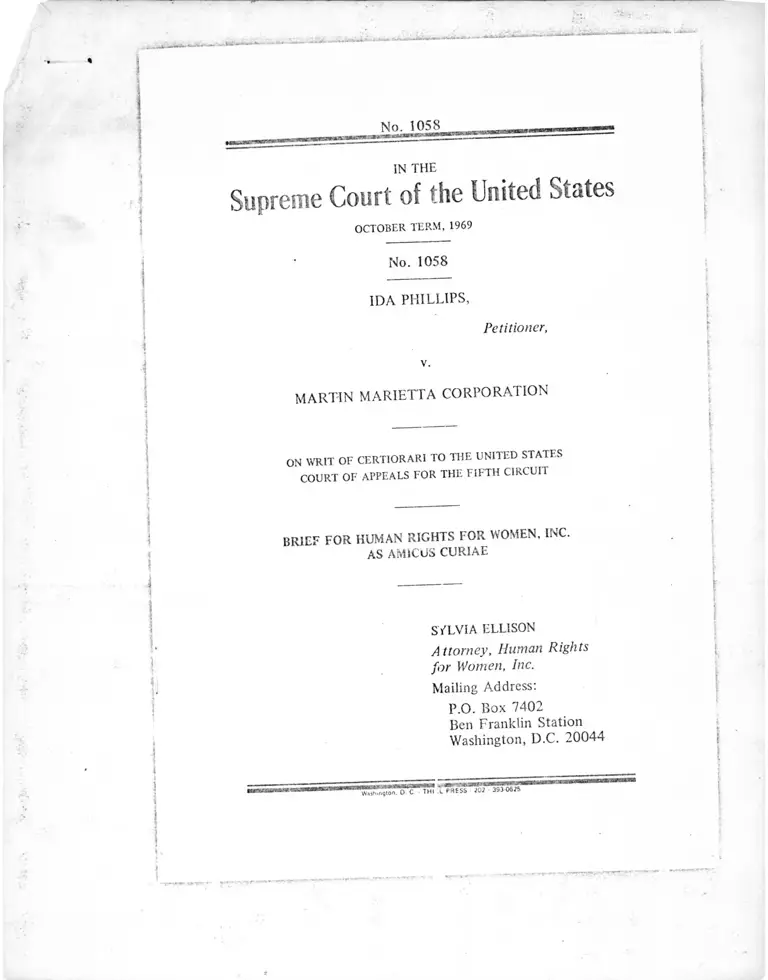

No. 1058

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

No. 1058

IDA PHILLIPS,

Petitioner,

v.

MARTIN MARIETTA CORPORATION

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

b r ie f f o r hum an r ig h t s f o r w om en , INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE

SYLVIA ELLISON

Attorney, Human Rights

for Women, Inc.

Mailing Address:

P.O. Box 7402

Ben Franklin Station

Washington, D.C. 20044

\

s

(i)

1

\

INDEX \

Question presented . .«

Interest of Human Rights for Women

J Statement ..........

Argument:

1. If sex is even one'element considered in hiring an

individual, no matter how it coalesces with other job

criteria (relevant or irrelevant), the proscriptions of

Title VII are violated

j

i44

2. Title VII prohibits pre-judging an individual on the

basis of sex by making a generalized assumption about

women . . . .

J

3. Employer policies as to job requirements may not

differentiate on the basis of sex, nor discriminate

against women . . .

4. The Court of Appeals interpretation of Title VII •

would nullify the protection of the law for the per

sons who are in greatest need of its protection 10

Conclusion . . 1 1

i

j CITATIONS

CASES:

1 Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (C.A. 7, 1969)

Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Tel. & Tel. Co 103 F Sunn

754 (N.D. Ala., 1969) . " PP'

6

7

I

Local 53, Int. Ass’n of Meat & Frost I.&A. Wkrs. v Voeler

407 F.2d 1047 (C.A. 5) Q

Local 189, Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United States,

416 F.2d 980 (C.A. 5), cert, denied, 38 L.W. 3320

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va.)

Richards v. Griffith Rubber Mills, 300 F. Supp 338 (D Ore

1969) v •’

8,9

8

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Co., 292 F. Supp. 219 (C.D.

Calif.', appeal pending, C.A 9

/

7

t7 m” d: r r " T % ,)c" Tcl:'p',onc Co: 2 FEP

lV'(CAV 5S°U969)n Bdl Td- 4 Co.. 408 F.2d 228 '

( ii)

ST A TUTE:

a 4 2 ^ . ^ “ leV'F78S- - . - ^

Sec. 703(a)

See. 703(e) . . . . ............... ' ' ‘ '

MIS CELLANEOUS:

29 C.F.R. 1604.1(a)(1)

° f Commerce, Bureau of the Census

No. 66, Table 41 CPR-60,

U SLahoPtF °f La5°r’ M°nth,y St3tistics on Woman Labor Force, data for May 1968

4

4

5,6, 7

11

1 1

10

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1969 v .

No. 1058

IDA PHILLIPS,

Petitioner,

v.

MARTIN MARIETTA CORPORATION

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OE APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR HUMAN RIGHTS FOR WOMEN, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

an employer may refuse to hire women with pre-school age

children while hiring men with pre-school age children.

INTEREST OF HUMAN RIGHTS FOR WOMEN, INC.

Hunan Rights for Women, Inc. is a non-profit tax exempt

organization, which was incorporated in the District of

Columbia in December 1968. One of its purposes is to pro

2

vide legal assistance without charge to women seeking to

invoke their rights under the Constitution and statutes of

the United States, particularly Title VI; of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, relating to equal employment opportunity. A

major portion ol IIRW's efforts and financial resources have

been devoted to furnishing free legal counsel for women in

Title VI1 cases.

Human Rights for Women is deeply concerned with a

clear and proper interpretation of Title VI1 as it applies to

sex dsicrimination and with equal protection of the law for

women. The decision of the Fifth Circuit in this case

endangers the protection of nondiscrimination legislation for

women and for all discriminated-against classes. HRW be

lieves that the Fifth Circuit has confused and misinterpreted

Title VII by holding that it permits the refusal to hire an

individual who possesses the characteristics of being (a) a

female and (b) a parent of pre-school age children. This

case presents a unique opportunity to clarify and define

what prejudice and discrimination really mean and the scope

of the proscriptions of the Federal statute prohibiting dis

crimination in employment.

STATEMENT

Martin Marietta Corporation refused to hire Ida Phillips

for the position of assembly trainee, advising her that the

company does not consider female applicants with pre

school age children for such position, although male appli

cants with such children are considered. (Pet. App. 2a) Mrs.

Phillips complained that her rights under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been violated. (78 Stat. 241,

253, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.)

The District Court struck the portion of the complaint

alleging discrimination against women with pre-school age

children and then granted the company’s motion for sum

mary judgment based on an uncontroi’erted showing that a

3

larger percentage of women applicants than men applicants

were hired tor the position of assembly trainee. (Pet App.

5a-6a)

The Court of Appeals affirmed, reasoning that a violation

of Title VII —

can only be discrimination based solely on one of

the categories i.e. in the case of sex; women vis-a-

vis men. When another criterion of employment is

added to one of the classifications listed in the Act,

there is no longer apparent discrimination based

solely on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

(Pet. App. 8a-9a)

The Court of Appeals further explained its theory of Title

VII as follows:

1 he discrimination was based on a two-pronged

qualification, i.e., a woman with pre-school age

children. Ida Phillips was not refused employment

because she was a woman nor because she had pre

school age children. It is the coalescence of these

two elements that denied her the position she

desired. (Pet. App. 9a-10a)

A petition for rehearing was denied, with Chief Judge Brown,

joined by Judges Ainsworth and Simpson, dissenting from

the denial. (Pet. App. 12a-13a)

ARGUMENT

We agree with dissenting Chief Judge Brown of the Fifth

Grcuit that if the above quoted “sex plus” interpretation

of Title VI1 is permitted to stand, “ the Act is dead.” (Pet.

App. 18a) We submit that the Court of Appeals interpre

tation of Title VII is wrong for the following reasons:

4

i ' S v S z

The very essence of fair employment legislation is to

require the exclusion from consideration of the character

(a)CoVthe8?ateidRn ,the StatUtC’ e‘g- S6X’ race‘ Section 703 (a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C 4000e-b(a»

makes ,t an unlawful employment practice for an employed

(1} or l1 L Z 7 lUStn H° hlrC ° r t0 dlSCharge ai^ dividual,or otherwise to discriminate against any individual

or privileged of e ^ "0mpensation> terms, conditions,

pi 8 employment, because of such indi-

* * * raCe> color’ relig>on, sex, or national origin;

Race color, religion, sex, and national origin are thereby

Z J t t aS permisslble j ° b qualifications. The employer7

each^f ^ empl0yment policies must in effect be blind to

employee dlaraCtenStics of ^ individual applicant or

theAlaw ° \hA V n tHH v tati°? SUbVCrtS the Ver̂ purpose of

tect dC aL ° n ° f a SCCOlld qualification to a pro-

tected class can exempt an employer policy or practice from

the prohibitions against nondiscrimination, then Catholic

r ,W° T ™ be dis“ mii>ated against, blacks can be required to pass a special stringent test to

qualify for a job, and Spanish-surnamed Americans can be

required to have PhD’s in English. Any emptov" r “ uW

tT a favored clP 7 ^ conti" u,; t0 8™ job preference o a favored class (e.g. white males) by adding a iob mnli

ft cation, relevant or irrelevant, for applicants of the protected

classes he wishes to exclude. Protected

mav^noTh qUam^ tion to the ru,e of Title VII that sex

7°3(e) of the Ac. (42 U.S.C. 2000e-2(e)), which provide!

1

5

that it is not unlawful to hire or employ employees on the

basis cf the employee’s sex (or religion or national origin)—

in those certain instances where religion, sex, or

national origin is a bona fide occupational qualifi

cation reasonably necessary to the normal operation

of that particular business or enterprise.

Under this provision, if maleness is necessary to the per

formance of particular work, a woman need not be con

sidered. Martin Marietta did not claim that sex (maleness)

was a BFOQ and it is obvious that being male could not

possibly be a BFOQ since “75 to 80 percent of those hold

ing the positions [of assembly trainee] were women." (em

phasis supplied). (Pet. App. 6a)

2. Title VII prohibits pre-judging an individual on

the basis of sex by making a generalized assump

tion about women.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s “Guide

lines on Discrimination Because of Sex” specifically state

that the following is a violation of Title VII (i.e. is not a

BFOQ):

The refusal to hire a woman because of her sex,

based on assumptions of the comparative employ

ment characteristics of women in general. For

example, the assumption that the turnover rate

among women is higher than among men. 29 CFR

1604.1 (a)( I )(i)

Under this rule, which we submit is correct, even if it could

be proved (and it has been neither claimed nor proved) that

women who are parents of pre-school age children are

absent from work more often than men who are parents of

such children, an assumption that an individual woman

would likely follow that pattern is a forbidden basis for

refusing to hire her. Fair employment legislation prohibits

making a generalization about a protected class. Women,

blacks, Jews, etc. must be treated as individuals and not be

saddled with presumed generalized characteristics.

6

The EEOC guidelines also describe as unlawful-

The refusal to hire an individual based on stereo

typed characterizations of the sexes. Such stereo

types include, for example, that men are less capable

of assembling intricate equipment, that women are

less capable of aggressive salesmanship. The principle

of non-discrimination requires that individuals be

considered on the basis of individual capacities and

not on the basis ol any characteristics generally

attributed to the group. 29 CFR 1604.1(a)(1)

(ii).

Employer policies that presume inabilities of women as a

class to perform certain work have been held violative of

Title VII. Thus the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh

Circuit reversed a District Court ruling that approved (as a

BFOQ) an employer practice of allowing only men to work

on jobs requiring the lifting of 35 pounds or more. Bowe

v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (C.A. 7, 1969). In

that case the court stated that Colgate-

must notify all of its workers that each of them

who desires to do so will be afforded a reasonable

opportunity to demonstrate his or her ability to per

form more strenuous jobs on a regular basis. Each

employee who is able to so demonstrate must be

permitted to bid on and fill any position to which

his or her seniority may entitle him or her 416

F.2d at 718.

The Fifth Circuit held in Weeks r. Southern Bell Tel.

& Tel. Co., 408 F.2d 228 (C.A. 5, 1969), that a 30-pound

weight lifting limitation on women workers does not make

being a male a BFOQ, nor does the desire to “protect”

women from having to work at night. The court pointed

out—

Title VII rejects just this type ol romantic paternal

ism as unduly Victorian and instead vests individual

women with the power to decide whether or not to

take on unromantic tasks. Men have always had the

right to determine whether the incremental increase

7

in remuneration for strenuous, dangerous, obnoxious,

boring or unromantic tasks is worth the candle

The promise of Title VII is that women are now '

to be on an equal footing. We cannot conclude

hat by including the bona fide occupational qualifi

cation exception Congress intended to renege on

that promise (408 F.2d at 236).

Similarly, in ruling that an Oregon weight lifting limitation

on women workers violates Title VII, the court in Richards

■ Griffith Rubber Mills, 300 F. Supp. 338 (D Ore 1969)

stated: ’

fcxcept in rare and justifiable circumstances, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e), the law no longer permits either

employers or the states to deal with women as a class

in relation to employment to their disadvantage 29

CFR § 1604.1(a). Individuals must be judged as

individuals and not on the basis of characteristics

generally attributed to racial, religious, or sexual

groups. 300 F. Supp at 340.

See also, Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Tel & Tel Cn

303 F. Supp. 754 (N.D. Ala., 1969); RosenfeU , S o u .L ,

racific Company, 292 F. Supp. 1219 (C.D. Calif.) appeal

pending in Ninth Circuit; Tuten v. Southern Bell Telephone

Co., 2 FEP Cases 299 (M.D. Fla. 1969).

TJ m p r rtS ° f aPPCalS and d'Strict courts have approved the EEOC Guidelines on Sex Discrimination and interpreted

he prohibitions against sex discrimination in Title VII as

prohibiting general assumptions about the inabilities of

women to meet certain job qualifications. 29 CFR 1604.1

(a)(n). Certainly, general assumptions about employment

characteristics (ibid., subparagraph (i)) are likewise prohib

ited. Indeed, unlike job qualifications, where there are

(though very few) instances in which sex itself is a BFOQ,1

The EEOC Guidelines state: “Where it is necessary for the nur-

fexSeto heU hntlC'rya 0r gem,ineness’ tll£ Commission will consider sex to be a bona fide occupational qualification, e.g an actor or

actress.” 29 CFR 1604.1(a)(2).

(continued)

8

there is no comparable qualification in the law that an

employer could use as a defense for a discriminatory gener

alization based on presumed employment characteristics of

women. Any assumption that a female applicant who is a

parent of pre-school age children would have less desirable

employment characteristics than a male applicant who is a

parent of such children is absolutely forbidden by Title VII.

Such pre-judging of an individual is what prejudice is.

3. Employer policies as to job requirements may not

differentiate on the basis of sex, nor discriminate

against women.

Employers are of course free to adopt any employment

policy, practice or rule consistent with law. To be consist

ent with Title VII any employment policy or practice—such

as a policy of excluding persons who are parents of pre

school children—must be applied without regard to race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin. Martin Marietta’s

policy in this case was applied only to female parents and

not to male parents. It obviously differentiates on its face,

on the basis of sex, and thereby violates the rights of

women under Title VII. The Fifth Circuit has held that

even where an employer rule or policy is neutral on its face,

if it operates to discriminate against a protected class under

Title VII (e . g women) the rule or policy must be changed

unless there is an overriding legitimate non-racial (non-sex

The BFOQ provision is not an exception in the normal sense of

the term. It was not meant to undermine the basic prohibition of

the Act and permit sex discrimination in employment. It is a mere

clarification, which points out that sex may be relevant to employ

ment in an extremely limited number of instances where “maleness”

or “femaleness” is a job requirement. Where an employment classi

fication or system is discriminatory, it is not “bona fide.” See Local

189 v. U.S., 416 F.2d 980, 988, and Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc.,

279 F. Supp. 505, 517 (E.D. Va. 1968). Therefore the BFOQ pro

vision creates no exception to Title VII and cannot be used as a

defense to a system of sex discrimination in employment as such sys

tem is not “bona fide.”

/

9

based) business purpose. See Luccl 189, Papermakers and

Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 989 (C.A. 5),

cert, denied, 38 L.W. 3320; Local 53, Int. Ass’n o f Ileat &

Frost I.&A. Wkrs. v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047, 1054 (C.A. 5).

For instance, in Local 189, it was pointed out that under

the business necessity principle an employer could require

that employees placed in secretarial positions be able to

type even though the requirement might mean the exclu

sion of disadvantaged black persons who had not had train

ing in this field. (416 F.2d at 988-989).

In Local 53, supra, the court held that a nepotism sys

tem, neutral on its face, but used to exclude black employ

ees from jobs, was a discriminatory system which could not

be defended on the ground of “business necessity” even

though there might be some incidental business advantages

in using the system.

The “business necessity” argument thus comes into play

only where a neutral rule, nondiscriminatory on its face,

incidentally operates against a protected class (blacks or

women) but for overriding business reasons rationally related

to the duties involved in the job the rule is shown to be non

discriminatory and thus not violative of the Act. Under no

circumstances has any court held that business necessity can

justify a discriminatory effect of an employment practice —

and the whole issue cannot arise where the employment

practice discriminates on its face, as in the instant case.

It is not even relevant here.

To recapitulate, for an employer practice to be valid as

a “ business necessity’Tmder Title VII, it would have to be

all of the following;

(1) Neutral on its face. E.g , if the policy applied with

respect to single (divorced, widowed) parents of pre-school

age children rather than to mothers, it would be neutral on

its face. 2

(2) Not discriminatory against women (or blacks) in its

operation. E.g., if it is shown that more women than men

10

without spouses had the custody and care of pre-school age

children, such neutral policy would operate to discriminate

against women and would be violative of Title VII.

(3) The policy itself must be relevant to the requirements

o f the job. Parenthood obviously could not be. But a cer

tain rate of absenteeism could be. Therefore, instead of

assuming that parents will have a high rate of absenteeism,

the policy must be tailored to the job requirement, i.e.,

employees must comply with certain attendance rate require

ments.

(4) The policy must be applied on an individual basis and

not on the basis o f sex (or race, etc.) Assuming, arguendo,

that it could be shown that blacks or women as a class had a

poorer attendance record, no such class presumption can be

made with respect to an individual black or woman. This

is the very kind of class pre-judging that Title VII forbids.

4. The Court of Appeals interpretation of Title VII

would nullify the protection of the law for the

persons who are in greatest need of its protection.

The purpose of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

is to protect women and other classes from employment

discrimination. Statistics on employment and earnings of

women as compared to men show that discrimination on

the basis of sex inflicts the most severe economic damage

on its victims and that, as a group, women heads of house

hold with children to support suffer most.

Nearly half of all women 18 to 64 years of age are in

the labor force. (Monthly Statistics on the Woman Labor

Force, data for May 1968, U.S. Dept, of Labor.) Women

with 1 to 3 years college earn less ($3714 for white women,

$3706 for nonwhite women) than men with an eighth

grade education (white men: $5184; nonwhite men: $4261).

White women with 4 or more years of college earn less

($5301) than nonwhite men with only a high school educa

tion ($5721). Nonwhite women with 4 or more years of

/

college are better off ($6275) than white women ($5301),

but nonwhite women are at the bottom in all lesser educa

tional categories. The white male earns the most of all

at all educational levels, a long standing privileged position

with sex and race discrimination shielding him from fair

competition. (Statistics for 1968, from U.S. Dept, of Com

merce, Bureau of the Census; CPR-60, No. 66, Table 41).

Eleven percent of American families are headed by

women; 35% of these families live in poverty; 61% of the

Nation’s poor children live in families headed by women.

(U.S. Dept, of Labor, “Fact Sheet on the American Family

in Poverty” , April 1968).

Women as a class, and especially women who are respon

sible for the support of children are in the greatest need of

protection against discrimination afforded by Title VII.

The ruling of the Fifth Circuit in this case judicially approves

a discriminatory policy of a private employer and places

women in the eyes of the law in a worse position than

before the enactment of Title VII. Prior to Title VII, such

private discrimination at least did not have the sanction of

Federal law. Such a construction of Title VII cannot be

permitted to stand.

CONCLUSION

The decision below should be reversed and remanded

witli instructions that judgment be entered for the plaintiff.

Respect 'ully submitted

SYLVIA ELLISON

Attorney, Human Rights for

Women, Inc., as Amicus Curiae

v

/ •

S . i '

• ■

?

r

r* •

a.. ,

v-

R

1

1;

jt-

!

. ■ . m • •• -

L)

. .

- 'I

..l-'

4 ' :

•sOSOc '»>•(/ ■uoiOtuysDM

‘uojfstvnuoo fttyuHiJoiMo tv-iwtRoidwj ivnl>;j

'latuiio.') iiu.tu >!)

•'iaasan -«i A aiw xs

U?C03 'O'(I ‘uotfjMt{gi>M

(o lujuiuodjfr

‘aHoon 'i m aaoa

’ivjawf) Journos .>!/< ro .'■vS‘V

‘aovaTViw 'o aoNaaAvva

‘liut&uao Haiuoti V tnotapsr

‘aaTKC.n aiaaar

‘liujiiou jouonos

‘GIO M SISO 'K IJXA\H3

3V13H3 sao m v SV S3LVIS uSIIKft 3HX SOI 53IU2

imoaio Bid ia 'dux no a s'jvA'ijr no in no.) sa iv is

unnxn au-i o i juvnoimno jo un.w v «oa xouiinn xo

xoixvuojaoo vxiarfvpj xiiavj.j

•a

aaxoixu/jj Sm it h f j vaj

6961 !-ra;c JKiaoiop

' - a

s m g f w ue m l a w d m a t i n g ’ « £

8 2 0 1 'O N

its - -«•*

• • - *:

■

. . .

• :

___ _____________________ _______ ___________________

gti the dfeurt of the Sailed states

October Term, 1969

No. 1058

I da P h il l ips , petitioner

v.

M artin M arietta Corporation

on PETITION FOU A IWHT OP CERTIORARI'TO THE V m T E D

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR I R E H U H CIRCVI

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

O PINIO NS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (Pet. App.

4 a -lla ) is reported at 411 F.2d 1. That court’s denial

of rehearing and rehearing en banc, with three ju ges

dissenting (Pet. App. 12a-21a), is reported at 416 F.2d

1257. The opinion of the district court (Pet App. la

3a) is not reported.

JURISD IC TIO N

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered

on May 26, 1969. A timely petition for rehearing was

denied on October 13, 1969. The petition for certi

orari was filed on January 10, 1970. The jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

(i)

2

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, under Title Y II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, ail employer may, in the absence of business

necessity, refuse to hire women with pre-school age

chi*'Ire while hiring men with such children.

STATU TE INVOLVED

Title Y II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provides

in pertinent paid:

42 U.S.C. 2000e-2

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge

any individual, or otherwise to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his com

pensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment, because of such individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin * * *•

(e) Notwithstanding any other provision of

this title (1) it shall not be an unlawful em

ployment practice for any employer to hire and

employ employees, * * * on the basis of his

religion, sex, or national origin in those certain

instances where religion, sex, or national origin

is a bona fide occupational qualification reason-

ablv necessary to the normal operation of that

particular business or enterprise * * *•

IN T E R E ST OF TH E U N IT E D STATES

Title Y II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits

discrimination in employment based on sex. Under the

Act, Congress has entrusted the United States Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and the At-

3

to rn e y G en e ra l w ith im p o r ta n t re sp o n s ib ilitie s f « r

o b ta in in g com pliance w ith th e re q u ire m e n ts o f T i tle

Y I I T h e c o u r t o f a p p e a ls ’ r e s tr ic te d in te rp r e ta t io n

o f th is im p o r ta n t s ta tu to ry m a n d a te , i f p e im it te

s ta n d w ill eause u n w a r ra n te d h a rd s h ip to a m i le s in

w , " h th e m o th e r is th e o n ly av a ilab le b re a d —

M o reo v er th e ra t io n a le o f th e decision below , i f ap -

pU ed to th e o th e r p ro h ib itio n s o f T i t le V I I a g a in s t

lo y m en t d is c r im in a tio n b ased on ia c e , ,

re g t a o r n a tio n a l o r ig in , w ou ld co m p reh en siv e ly

b i p ed th e g o v e rn m e n t’s e ffo rts to in su re e q u a lity o f

em p lo y m en t^ o p p o r tu n itie s fo r a ll re s id e n ts o f th e

United States. statem ent

S ole ly because she w as a w om an w ith p re -sch o o l

! c h ild ren th e p e t i t io n e r w as d en ied em p lo y m en t

I s a n a ssem b ly -tra in e e b y tlie re sp o n d e n t c o rp o ra tio n ,

• z — r ” : * s

t in n e r ’s co m p la in t by s tiiK in & u t

d is c r im in a tio n based on th e f a c t th a t * - I

school age c h ild re n , on th e g ro u n d -t h a t J ' 5

not prohibit such discrimination, flic

S t ’

Lewis v. Martin, No. 829, this Term.

4

granted respondent’s motion for summary judgment,

based on an uncontroverted showing that a larger per

centage of the women, as compared with the men, who

applied for the job of assembly-trainee were hired.

The court of appeals affirmed, stating (Pet.

App. 9a-10a) :

* * * The evidence presented in the trial court

is quite convincing that no discrimination against

women as a whole or the appellant individually

was practiced by Martin Marietta. The dis

crimination was based on a two-pronged quali

fication, i.e., a woman with pre-school age

children. Ida Phillips was not refused employ

ment because she was a woman nor because she

had pre-school age children. It is the coales

cence of these two elements that denied her the

position she desired.

A petition for rehearing was denied, with three

judges dissenting from the denial of rehearing en

banc.

REASONS FOR GR A NTIN G T H E W R IT

The decision below directly affects a substantial

number of women in the labor market2 and condones

discrimination against them in contravention of the

federal policy of encouraging unemployed women with

pre-school age children to seek gainful employment

as an alternative to welfare payments.3

2 In March 1967, there were 10.6 million working women

witli children under 18 years of age. Of this number, 38.9 per

cent, or 4.1 million, were mothers with children under 6 years

of age. “Who Are The Working Mothers?” U.S. Dept, of

Labor, Wage and Hour Adm. (Leaflet 37, 1968).

8 See, e.g., President Nixon’s Address to the Nation on Domestic

5

Moreover, application of the reasoning of the court

of appeals to the Title V II prohibitions against em

ployment discrimination based on race, color, religion

or national origin would have a severely limiting ef

fect. For example, a practice of refusing to hire

Negroes with pre-school children while hiring whites

with such children would apparently come within the

rationale of the decision below that:

[w]hen another criterion of employment is

added to one of the classifications listed in the

Act, there is no longer apparent discrimination

based solely on race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin [411 F.2d at 3-4].

Nothing in the record of the present case indicates

that the respondent’s policy of excluding women with

pre-school age children from employment was based

on any legitimate business interest related to the

ability of such women'to perform the work, or to the

safety or efficiency of the "respondent’s busines¥ opera

tions. Specifically, there was no showing that such

Programs, Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, Vol. 5,

No. 3*2, August 11,19G9,p. 1108: .

As I mentioned previously, greatly expanded day-care cen

ter facilities wo \d be provided for the children of welfare

mothers who choose to work. However, these would be day

care centers with a difference. There is no single idea to

which this administration is more firmly committed than

to the enriching of a child s first 5 years of life, and

thus helping lift the poor out of misery, at a time when a

lift can help the most. Therefore, these day-care centers

would offer more than custodial care; they would also be

devoted to the development of vigorous young minds and

■bodies. As r fu rther dividend, the day-care centers would

offer employment to many welfare mothers themselves.

6

women had a higher than average absentee rate, that

they could not work necessary.overtime, or that they

had any other attribute which limited their utility

to the respondent. Much less was there a showing

that all women with pre-school age children were

unable to perform adequately.

The courts below, therefore, did not rely on any

overriding “business necessity,” 4 nor on the stat

utory exception for a “ bona fide occupational quali

fication,” 8 in holding that the respondent’s policy did

not violate Title V II. Instead, the court of appeals’

holding is explicitly based on a construction of the

statute which condones discrimination based on sex

so long as there is an additional, apparently neutral,

reason^ for the otherwise unlawful employment

practice. 1 . „

This holding contravenes the plain language ot

Section 703, which makes it an “ unlawful employ-

ment practice for an employer .*_ ! A ta discriimiiate

against any individual with respect to lus •

terms [or] conditions * * * of employment, because of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin * * To require of i prospective women em-

D.scc q $ i ^ ( e ) ( l ) , supra, p. 2.

■vudns ‘f -u ui pa;io sosud ‘ospi ‘aog 'STOOI T t09I d d ^

7 re T r A o n r i S lip U 3 U ia [ (T llU S U O U l![llS o .I S.IIOISSUUUXOO £ % v m

toddo ^uoui^oiduia I«uba 0tp aas P"V '(8 '.V.V)

‘8J9M.oa\ m v w m s ’A v n ^ a -986 S H S6S S9̂ S

i - 4 - J S > i « 'S'A « * “r " o % AZ

mno'j =896 'ST1 Z08 ‘«^7bll ’A VUVT- 'JD ' (I!lBp,

IdaS ',1 86c '-OQ ofrooj M ^noS 'A Vl9t™*°H ; (9 _^0> ^ 3

>r q0f. ‘-0 9 9um[d9px IPS u j^tinos 'A S'-7‘̂ JI • ^ _V p ' TU

£ 5 89Xf 4 Z io r a p j-^ O p j -a wwff ‘.CuiuoiiaSJeeS^

•u o ip o jo .id jo q j jo poou

■n |SOut 8SotU Suouiu 9.ra oipw sjtre o n d d u juaraX opI

-rao JO A.xoSojyo o OJ uo ijoapx td s,9 jn ji3 js a q j poraop

suq Auqoq uotsiaap m ‘̂ P umxl joqj uio.tj Siupnxlopuj

•oiupinnu [imoiss9.1.0uoo oi[j jo oouesso oqj si siqx , d s

-S900U ssamsnq .10 ^uoipjopiimib jmioijBdnooo opq rnioq,,

t> STJ UOIJTmtUIUOSip HOtlS ^JIJSIlC uuo .loA qdraa 91U

swim. W » ‘xos 9U0 10 f " 9" * 1*

no atoios p asod im s i uo ip io p ip n ib « ‘o.ioq so o.ioqAV

•I19UI JO paaiubojc jou si qaiqAV uoijtjoq

_,pmb S[l[) )38iu 1011 op oqa\ uouioai 8S0i|) Aq pOAiooo.1

iuounBO.il oiMBdsip oit) opmuuiio )ou saop a iioi)ip

-uoo,. .10 „UH0)„ Sim *>... “ “ I 1 » » n » W « 8!

oq) )[ UOAO ‘UOlUOiV OUIOS )BII) 1->BJ 0'IX 'poAopluio

on m k .toll) i p t q * .rapm> „ s u o m p u o o „ ,io „ s u u o ) „

- m xos .non) J ° < W 8II* u0 U8U,0‘" ^

-u u u o s ip 0) s i ‘Irani jo ouros o .|) S u u in b o i )» u o,p[Ai

‘uo.ippqo oiic [ooqos-o.ul oabi( ) ou to n ) p in ) sooAo[d

L

8

CONCLUSION

It is therefore respectfully submitted that the peti

tion for a writ of certiorari should he granted.

E rw in N . Griswold,

Solicitor General.

J erris L eonard,

Assistant Attorney General.

L awrence G. W allace,

Assistant to the Solicitor General.

R obert T . M oore,

Attorney.

S tanley P . H ebert,

General Counsel,

Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission.

F ebruary 1970.

U.S . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFPICE: l » 7 0