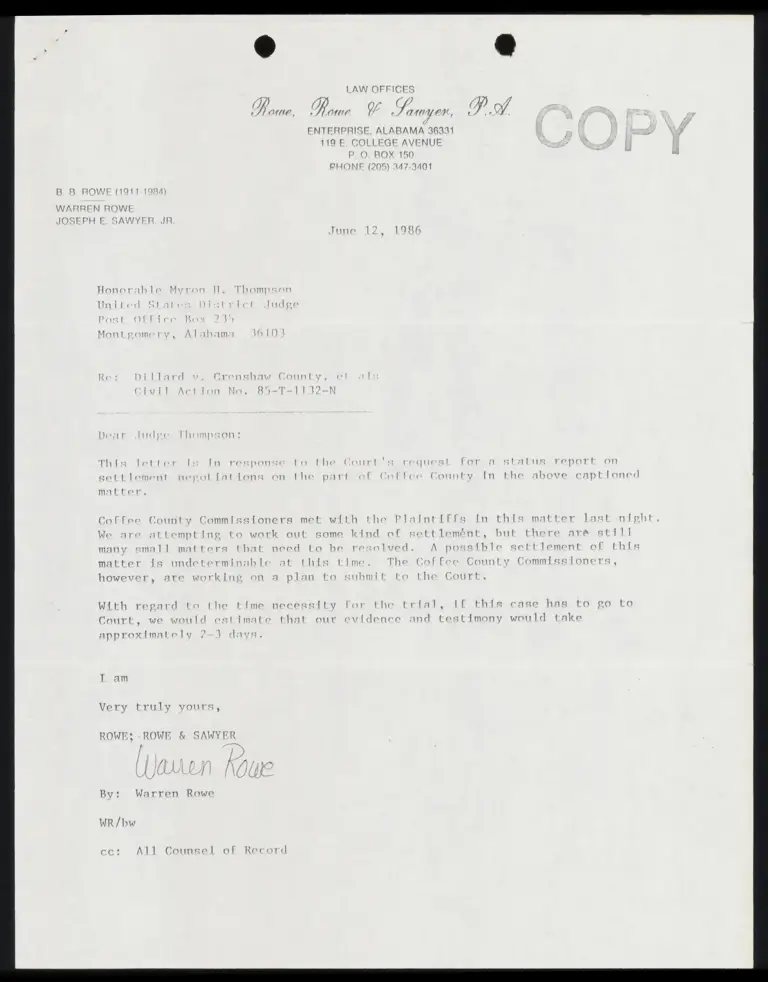

Letter from Warren Rowe to Judge Thompson RE: Settlement Negotiations

Correspondence

June 12, 1986

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Letter from Warren Rowe to Judge Thompson RE: Settlement Negotiations, 1986. 707debf0-b9d8-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5b87e40-40e8-4d19-8cac-4aa996979ca4/letter-from-warren-rowe-to-judge-thompson-re-settlement-negotiations. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

LAW OFFICES

A { A E 7) /

(0 0 vor: ZL a

‘ 2 ine. . Po Gy ¢ £7 rey en, et C ;

ENTERPRISE, ALABAMA 36331

119 E. COLLEGE AVENUE

P.O. BOX 150

PHONE (205) 347-3401

B. B. ROWE (1911-1984)

WARREN ROW!

JOSEPH E. SAWYER, JR

Jane 12. 1986

Honorable Mvron 1, Thomnaon

Hnited Stat iatrict ludee

Post Office Bo Je on

Montsomery, Alabama 1 0)

RY Di lIliard vv. Crenshaw County

J il Act Yorn No 35 | 31 ] N

11 f11 { I'l D2 ON

This letter | in response to the Court's request for a status report on

got tlement negotiations on the part of Coffee County In the above captioned

Mmattel

Coffee County Commissioners met with the Plaintiffs In this matter last night

We are attempting to work out some kind of settlemént, but there are still

many small matters that need to be resolved. A possible settlement of this

matter is undeterminable at this time. The Coffee County Commissioners,

however, are working on a plan to submil ro the Court

With regard to the time necessity for the trial, If this case has to go to

Court, we would eat imate that ou ovidence and testimony would take

approximately 23 dava,

Lam

Very truly yours,

ROWE ROWE & SAWYER

Bvt Warren Rowe

WR /bw

CC! All Counsel of Recor

LAW OFFICES

Rowe, Rowe & ower

P. O. BOX 150

119 E. COLLEGE AVENUE

ENTERPRISE, ALABAMA 36331

DEBORAH FINS

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

99 HUDSON STREET

16TH FLOOR

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10013