School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Brief on Behalf of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

31 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v. Allen Brief on Behalf of Appellants, 1956. e629694f-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5d9942e-dfad-43ae-a174-a90df33fa85d/school-board-of-the-city-of-charlottesville-virginia-v-allen-brief-on-behalf-of-appellants. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

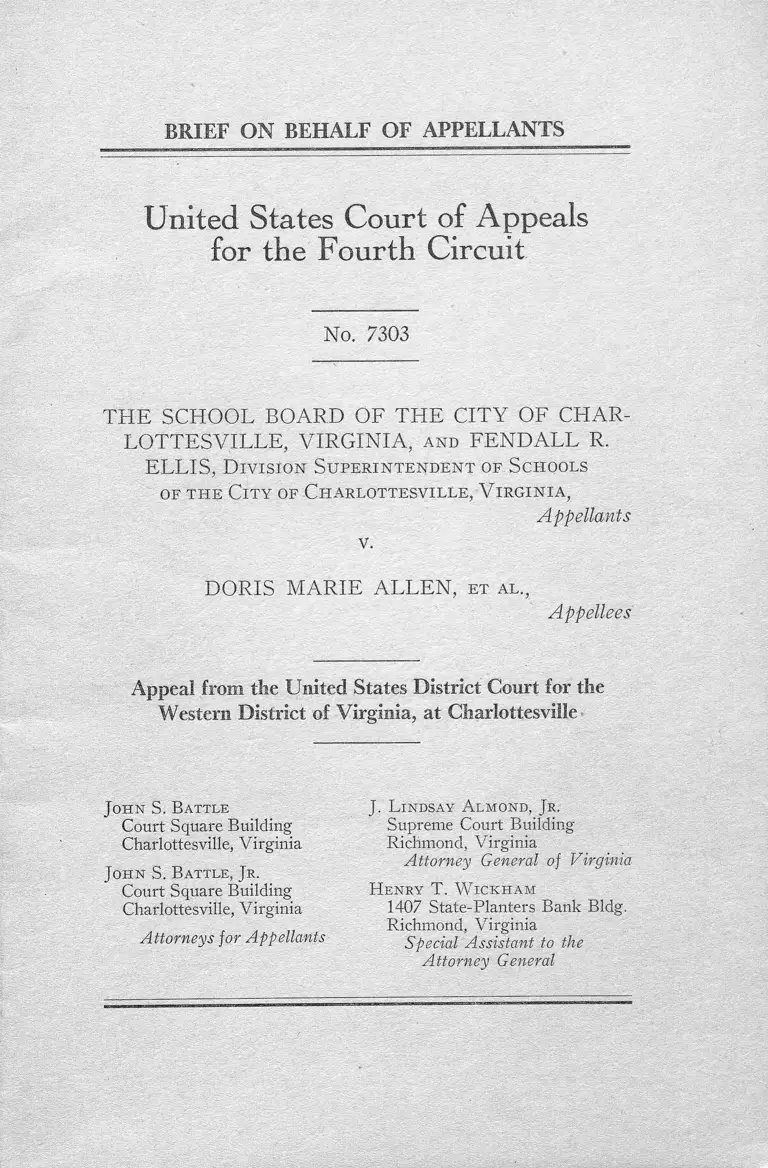

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

T H E SCH OOL BO ARD OF TH E C ITY OF C H A R

LO TTE SV ILLE , V IR G IN IA , an d F E N D A L L R.

ELLIS, D iv is io n S u p e r in t e n d e n t of S chools

of t h e C it y of C h a r lo tte sv ill e , V ir g in ia ,

Appellants

v.

DORIS M A R IE ALLEN , et a l .,

Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Virginia, at Charlottesville

Jo h n S. B a t t l e

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Jo h n S. B a t t l e , Jr .

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

J. L in d s a y A l m o n d , Jr .

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Attorney General of Virginia

H e n r y T. W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

... 1S t a t e m e n t of t h e C ase

T h e Q u estio n s I n v o l v e d ...................... 2

S t a t e m e n t of t h e F a c t s ............................................................... 3

A r g u m e n t ................................................................................. 6

I. The Appellees Are Prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment

from Maintaining This Action .................................................... 6

A. This Action Is a Suit Against the State............................... 6

B. The State Has Not Given Its Consent to Be Sued in a

Federal C ourt................................... 9

II. Appellees Have Failed to Prove a Case Upon Which the

District Court Could Have Granted Injunctive R elief............ 12

III. The Appellees Have Not Exhausted Their Administrative

Remedies ....................................................................................... 20

IV. The District Court Has Abused Its Discretion by Entering

an Order Effective September, 1956 .......................................... 25

C o n c lu sio n .................................................... 27

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Board of Supervisors v. County School Board, 182 Va. 266 (1944 ) 7

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 ..................... .......................... 17, 25

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (May 17, 1954), 347

U. S. 483, and (M ay 31, 1955) 349 U. S. 294 ................ ....12, 13

14, 15, 19

Bush v. Orleans Parrish School Board, 138 F. Supp. 337 (U. S.

D. C., ED, La., 1956) ................... ................ .................... ........... 25

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County, 227 F. (2d)

789 (4th Cir., 1955) ................................................. 21, 22, 23, 24

Page

Duhne v. New Jersey, 251 U. S. 311 (1920) ..... 6

Ex Parte New York, 256 U. S. 490 (1921) ..................................... 6

E x Parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908) ........... 6

Fitts v. McGhee, 172 U. S. 516 (1899) ........ 6

Ford Motor Co. v. Department of Treasury, 323 U. S. 459 (1945) 11

Georgia R. R. & Banking Co. v. Redwine, 342 U. S. 300 (1952) 7

Great Northern Life Ins. Co. v. Read, 322 U. S. 47 (1944) ............ 10

Plans v. Louisiana, 134 U. S. 1 (1890) ............................................ . 6

Hood v. Board of Trustees, 232 F. (2d) 626 (4th Cir., 1956) 23, 24

Kennecott Copper Corporation v. State Tax Comm’r., 327 U. S.

573 (1946) ..................................................... 11

Maia v. Eastern State Hospital, 97 Va. 507 (1899) ........................ 12

Matthews v. Launius, 134 F. Supp. 684 (U . S. D. C., W . D. A r k ,

1955) ............................ 25

Missouri v. Fiske, 290 U. S. 18 (1933) ...... .................................... 8

O ’Neill v. Early, 208 F. (2d) 286 (4th Cir., 1953) ...... ......... 7, 12

Osborn v. Bank of United States, 9 Wheat. 738 ............................... 6

Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s C ounty.................. 24

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378 (1932) ..................................... 7

Other Authorities

Code of Virginia (1950) :

Section 22-63 ............................................................................ . 9, 10

Section 22-94 ...................................................................................... 10

Section 22-57 ............... ................. ............................................ 20, 21

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 7303

T H E SCHOOL BO ARD OF T H E C ITY OF C H A R

LO TTE SV ILLE , V IR G IN IA , and FE N D A LL R.

ELLIS, D iv is io n S u p e r in t e n d e n t of S chools

of t h e C it y of C h a r lo tte sv ill e , V ir g in ia ,

Appellants

v.

DORIS M AR IE ALLEN , :et a l .,

Appellees

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Virginia, at Charlottesville

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLANTS

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

This class action came on to be heard on July 12, 1956

upon the complaint of the appellees, the answer of the appel

lants and evidence offered by both parties, including ex

hibits, depositions and testimony.

The appellees prayed that a preliminary and permanent

injunction be granted restraining and enjoining the appel

lants from enforcing and pursuing against appellees the

policy and custom of precluding, on the basis o f race or

2

color, their admission to the public schools of the City of

Charlottesville.

The appellants, in answer, asserted that they were not

required to integrate the public schools o f the City of Char

lottesville and moved the District Court to dismiss the com

plaint on the grounds, among others, that the action involved

no case or controversy upon which relief should be granted

and that the State had not given its consent to be sued in this

action.

On August 6, 1956, the District Court entered its order,

effective at the commencement of the school term beginning

in September, 1956, restraining and enjoining the appellants

from any action that would regulate or affect, on the basis

o f race or color, the admission, enrollment or education of

the appellees, or other Negro children similarly situated,

to or in any public school operated by the appellants.

T H E Q U E S T IO N S IN V O L V E D

Point I

May a federal district court enjoin a local school board,

which is admittedly an agency of the Commonwealth of

Virginia, and a State officer in his official capacity when the

Commonwealth has not given its consent to be sued ?

Point II

Is there any case or controversy presented by this action

over which a federal district court has jurisdiction?

Point III

Have the appellees exhausted their administrative rem

edies so as to entitle them to relief in a federal district court ?

3

Point IV

Under the facts of this case and the law applicable thereto,

has not the federal district court abused its discretion by

entering its order which had the effect o f compelling inte

gration by the commencement of the September, 1956, school

term?

STATEM ENT OF THE FACTS

The appellees stated in their bill of complaint that the

appellant school board is an administrative department of

the Commonwealth of Virginia. The appellants agree. The

appellees further alleged that appellant Fendall R. Ellis,

Division Superintendent of Schools for the City of Char

lottesville, is an administrative officer o f the Commonwealth

o f Virginia. To this allegation, the appellants also agree.

The complaint also alleged that the appellees made a

formal demand that the appellants conform to the school

segregation decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States and discontinue the policy and custom of operating a

segregated school system. It was further alleged that the

appellees “ possess all qualifications and satisfy all require

ments” for admission to the public schools o f the City o f

Charlottesville.

In order to sustain the aforesaid allegations, the appellees

introduced certain exhibits and presented two witnesses, one

of which was the appellant Fendall R. Ellis. The substance

of the appellees’ evidence is as follows:

1. A petition, marked Plaintiffs’ Exhibit “ A ” , was mailed

to the appellants by certain attorneys on October 6, 1955,

on behalf of some forty-four children. It was stated that

these children were eligible to attend the public schools o f

the City of Charlottesville. The petition also demanded that

4

the appellants “ take immediate steps to reorganize the public

schools” and pointed out that the appellants were “ duty-

bound to take immediate concrete steps leading to early elim

ination of segregation in the public schools.”

2. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit “ B” represents the reply of the

appellants to the appellees’ petition and is in the form of a

resolution adopted by the appellant school board. The reso

lution stated that a solution to the problem presented by the

school segregation decisions could be found only “ after sober

reflection over a period of time.” Reference was also made

to a former resolution o f the appellants school board, adopt

ed July 8, 1955, wherein it was resolved “ to begin promptly

a study of the future operation o f the City’s public school

system in the light of the Supreme Court decrees of May 31,

1955.”

3. George R. Ferguson was called as a witness for the

appellees and stated that he was a Negro and that his child,

one of the appellees, attended Burley High School which was

operated jointly by the City of Charlottesville and the County

of Albemarle for members o f the Negro race. It was then

conceded by counsel for the appellants that all o f the appel

lees were Negroes who resided in the City of Charlottesville

and were eligible to attend the public schools.

4. Appellant Fendall R. Ellis was called as an adverse

witness. He testified that there were six elementary schools

in the City of Charlottesville, five of which were attended

by white children and one o f which was attended by Negro

children. There is one white high school and one Negro

high school, which is jointly owned and operated by the

City and County. Mr. Ellis also testified that the school

budget for the school year, 1956-57, had been adopted and

submitted to the City Council prior to April 1, 1956, and that

5

the appellant school board had approved no plan “ to deseg

regate the city school for the school term 1956-1957.” Upon

questioning by the Court, Mr. Ellis stated that there were

2,436 white children in the elementary schools and 761

Negro children. There were 897 white children and 281

Negro children enrolled in the high schools.

As their principal evidence, the appellants introduced the

depositions of Fendall R. Ellis and o f James H. Michael,

Jr., a member of the appellant school board. Mr. Ellis stated

that preparations for the operations of the schools for the

year, 1956-1957, had been completed and that a change at

such a late date “ would not only occasion great difficulty, but

would also be most disruptive and impractical.” He further

stated that any change of plans involving the transfer of

school children “ would be most disruptive of orderly pro

cedure and prove of harmful effect in the administration of

the public school system.”

Mr. Michael, in his deposition, agreed with Mr. Ellis and

stated that since the essential administrative steps relative

to the opening of the public schools had been taken, any

disruption “ would seriously militate against orderly and

efficient administration of the educational process to the

lasting detriment of the school children of the City of Char

lottesville.” He went on to state that many months of care

ful consideration would be necessary to determine shifts o f

pupil population from one school to another since such shifts

raised questions of distribution o f teachers, and the number

required, of available space in the various schools and of

curriculum adjustments.

Cross-examination of the witnesses, Ellis and Michaels,

did not reveal any significant facts not already set forth

above and there was no further material evidence presented

to the Court below.

6

ARGU M EN T

I.

The Appellees Are Prohibited by the Eleventh Amendment

From Maintaining This Action

The Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States reads as follows:

“ The judicial power of the United States shall not be

construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, com

menced or prosecuted against one of the United States

by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects of

any foreign state.”

Although the Eleventh Amendment only expressly covers

suits by citizens of another state or citizens or subjects of

a foreign state, it has been interpreted as prohibiting suits

against a state by its own citizens. Hans v. Louisiana, 134

U. S. 1 (1890) ; Fitts v. McGhee, 172 U. S. 516 (1899);

Duhne v. Nezv Jersey, 251 U. S. 311 (1920 ); Ex parte A ew

York, 256 U. S. 490 (1921).

A.

T h is A ction I s a Su it A g a in st t h e Sta te

As early as 1824 the United States Supreme Court in

Osborn v. Bank of United States, 9 Wheat. 738, held that

a state official possesses no official capacity when acting

illegally and hence can derive no protection from an uncon

stitutional state statute.

In the case of Ex parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908), the

Attorney General of Minnesota had been found guilty of

contempt of a federal court in that he had refused to dismiss

mandamus proceedings brought to compel compliance with a

7

state statute governing the rates of certain railroads. The

Supreme Court held that the action in the federal court was

not a suit against the state in that it sought only to enjoin

a state officer from enforcing an unconstitutional statute.

In Georgia R. R. & Banking Co. v. Redzvine, 342 U. S.

300, 304 (1952), a case to enjoin a state officer o f Georgia

from enforcing an allegedly unconstitutional tax, the late

Chief Justice Vinson, speaking for the Court, said:

“ * * * This Court has long held that a suit to restrain

unconstitutional action threatened by an individual who

is a state officer is not a suit against the State. These

decisions were reexamined and reaffirmed in E x Parte

Young, 209 U. S. 123, 52 L. Ed. 714, 28 S. Ct. 441,

13 L. R. A. NS 932, 14 Ann. Cas. 764 (1908), and have

been consistently followed to the present day. * * *”

For the purposes of this argument, the appellants accept

the principles enunciated in the foregoing cases, namely, that

when there is a showing that the exertion of state power

overrides rights secured by the Constitution, an appropri

ate proceeding may be brought against the individuals

charged with the transgression. See, Sterling v. Constantin,

287 U .S . 378, 397 (1932).

However, the instant case has been brought against a local

school board which is concededly an agency of the Common

wealth of Virginia. The action of the appellants is the action

of the state, since local school boards and division superin

tendents are the means through which the state performs its

function of maintaining a public school system. See, Board

of Supervisors v. County School Board, 182 Va. 266 (1944)

and O’Neill v. Early, 208 F. (2d) 286 (4th Cir., 1953).

Accordingly, it is the contention o f the appellants that the

appellees, in absence o f state consent, cannot maintain this

action because of the prohibitions of the Eleventh Amend

ment. It has been urged, however, that if such be the hold

ing o f the Court, the appellees would be unable to enforce

rights secured by the Constitution. This, of course, is not

true, since it is conceded by the appellants that the appellees

may, in an appropriate proceeding, sue individuals who may

be charged with violating their rights under color o f an

unconstitutional statute.

It has also been suggested that the school board is suable

because if acting as charged in the complaint, it is not acting

as an agency of the state. A state may act only through its

officers and agencies. Therefore, an agency of the state is

the state itself. The question immediately arises, then, as to

when is a state not a state. If it be held that a state is not a

state when it acts in an unconstitutional manner, the prohibi

tions contained in the Eleventh Amendment would be dras

tically limited, contrary to their plain meaning, and to the

decisions rendered thereunder.

The proper interpretation of the Eleventh Amendment,

in so far as its applicability to particular types of suits, is

found in the following language of Missouri v. Fiske, 290

U. S. 18,25-27 (1933):

“ The Eleventh Amendment is an explicit limitation

o f the judicial power of the United States. . . . However

important that power, it cannot extend into the forbid

den sphere. Considerations of convenience open no

avenue of escape from the restriction. The ‘entire ju

dicial power granted by the Constitution does not em

brace authority to entertain a suit brought by private

parties against a State without consent given.’ Ex

parte Nezv York, 256 U. S. 490, 497. Such a suit can

not be entertained upon the ground that the controversy

arises under the Constitution or laws of the United

States. Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U. S. 1, 10 ; Palmer v.

Ohio, 248 U. S. 32, 34; Duhne v. New Jersey, 251 U. S.

311,313,314.”

9

. . Expressly applying to suits in equity as well as

at law, the Amendment necessarily embraces demands

for the enforcement of equitable rights and the prose

cution o f equitable remedies when these are asserted

and prosecuted by an individual against a State. This

conception of the Amendment has had abundant illus

tration. Louisiana v. Jutnel, 107 U. S. 711, 720; Ha-

good v. Southern, 117 U. S. 52, 67; In re Ayers, 123

U. S. 443, 497; Fitts v. McGhee, 172 U. S. 516, 529.”

Therefore, it must be concluded that the Eleventh Amend

ment prohibits a suit against a state whether the nature of

the suit involves interest in property or civil rights o f indi

viduals.

In conclusion, the appellants repeat that they do not con

tend that the Eleventh Amendment prohibits a suit against

individual members of a local school board or against a divi

sion superintendent as an individual acting under an uncon

stitutional statute. Individuals have not been named in the

instant case nor have they been served with process. This

action is a suit against the state in name and in fact, and as

such, should be dismissed, unless it can be successfully con

tended that the state has consented to be sued.

B.

T h e S ta te H as N ot G iv e n I ts C o n sen t

T o B e S ued in a F ederal C ourt

The school board is created by statute as a body corporate,

and among its enumerated powers is the power to sue and

be sued. Section 22-63, Code o f Virginia (1950) deals with

the county school board in the following language:

“ §22-63. School board constitutes body corporate;

powers generally.— The members so appointed shall

10

constitute the county school board, and every such

board is declared a body corporate, under the style of

the County School Board o f ............. ....... County, and

may, in its corporate capacity, sue or be sued, contract,

or be contracted with and, in general, is vested with all

the powers, and charged with ail the duties, obligations

and responsibilities imposed upon such board as such

by law.”

The provision relating to the city school board, as contained

in Section 22-94, Code of Virginia (1950), is as follows:

“'§22-94. Constitutes a corporation: powers and duties

generally.— The school trustees of each city shall be a

body corporate under the name and style of ‘The School

Board of the City o f __________’, by which name it may

sue and be sued, contract and be contracted with, and

purchase, take, hold, lease, and convey school property,

both real and personal. The title to all school property

both real and personal, within the city shall vest in the

board, except by mutual consent of the council and

school board the title to property may vest in the city.

The trustees of the several districts, where there are

more than one, shall have no organization or duties

except such as may be assigned to them by the consoli

dated body.”

The question to be decided is whether or not the above

quoted statutory provisions apply only to suits in state

courts. Three decisions of the United States Supreme Court

hold that consent to suit in the federal courts will not be

implied, but must be expressly stated by statute.

In Great Northern Life Ins. Co. v. Read, 322 U. S. 47

(1944), a foreign insurance company brought suit in a

federal district court to recover the tax paid under protest

on premiums written in the state. Although the statutory

provision for appeal o f such taxes provided that “ all such

11

suits shall be brought in the court having jurisdiction there

o f,” the Supreme Court held that the clear implication of

the statute as a whole was that the state consented only to

suit in its own courts. The Supreme Court stated at page 54:

“ . . . When a state authorizes a suit against itself to do

justice to taxpayers who deem themselves injured by

any exaction, it is not consonant with our dual system

for the Federal courts to be astute to read the consent

to embrace Federal as well as state courts. Federal

courts, sitting within states, are for many purposes

courts of that state, Madisonville Traction Co. v. St.

Bernard Min. Co., 196 U. S. 239, 255, 49 L. Ed. 462,

468, 25 S. Ct. 251, but when we are dealing with the

sovereign exemption from judicial interference in the

vital field of financial administration a clear declaration

of the state’s intention to submit its fiscal problems to

other courts than those of its own creation must be

found.”

In Ford Motor Co. v. Department of Treasury, 323 U. S.

459 (1945), the Supreme Court reaffirmed its position in the

Read case under similar facts. Although the state statute

authorized action in “ any court of competent jurisdiction,”

the Supreme Court, on considering the whole statute, failed

to find the requisite clear indication of consent to suit in a

federal court.

The case of Kennecott Copper Corp. v. State Tax Comm’r,

327 U. S. 573 (1946), again illustrates the position taken by

the Supreme Court on this question. There, the applicable

state statute also provided only that one “ may bring an

action in any court o f competent jurisdiction.” The Supreme

Court nevertheless held that the suit could not be brought in

a federal court and concluded at pages 579-580:

12

“ W e conclude that the Utah statutes fall short of the

clear declaration by a state of its consent to be sued in

the federal courts which we think is required before

federal courts should undertake adjudication of the

claims of taxpayers against a state.”

This Court has also concluded that the statutes now under

consideration do not authorize a suit against a local school

board in a federal court. In O’Neill v. Early, supra, at page

288, Chief Judge Parker, speaking for the Court, said:

“ The fact that the state has authorized the defendant

school board to sue and be sued is immaterial, since it

has not consented to suit in the federal court. * * *”

Compare, Mala v. Eastern State Hospital, 97 Va. 507

(1899), wherein it was held by the Supreme Court o f Ap

peals of Virginia that simply because a public corporation

was authorized by statute to sue and be sued, it did not

follow that it could be sued in all cases in which a private

corporation may be sued.

It must be concluded, therefore, that since this action is a

suit against the state for which consent has not been given,

it must be dismissed as violating the Eleventh Amendment.

II.

Appellees Have Failed to Prove a Case Upon Which the

District Court Could Have Granted Injunctive Relief

This court is now hearing upon appeal one of its first

cases against a school board which was not a party in

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (M ay 17, 1954),

347 U. S. 483, and (M ay 31, 1955) 349 U. S. 294. There

fore, it is to be assumed that the decision in this case must

create the original and fundamental precedents relating not

13

only to procedural requirements in federal district courts

but relating also to the requirements of proving whatever

specific facts as are necessary, as a matter o f substantive

law, to support the specific relief thought to be afforded by

the doctrine of the Brown case. Hence, it is felt with good

reason that the point presented here is of great importance

both to the final determination of this case and to the sub

sequent consideration o f similar cases by other district

courts.

To present the point clearly it is necessary to show the

theory upon which the appellees proceeded in the court

below. Some idea of that theory can be gathered from the

so-called “ petition” sent to the local school board by

N A A C P attorneys purporting to represent a certain group

of Negroes. This “ petition” merely called the school board’s

attention to the Supreme Court decision in the Brown case,

construed it to require the early elimination of segregation

in the public schools and demanded that immediate steps be

taken “ to reorganize the public schools under your juris

diction so that children may attend them without regard to

their race or color.” Subsequently, the same attorneys, pur

porting to represent substantially the same persons as listed

in the “ petition” filed their complaint alleging, among other

things, that the appellants maintain and operate separate

public schools for Negro and white children, respectively,

and deny the infant appellees, because of their race and

color, admission to and education in public schools operated

for white children, pursuant to a policy, practice, custom

and usage of segregating, on the basis of race or color, all

the children attending the public schools; and further that

the appellants will continue to pursue against the appellees,

and all other children similarly situated, the same policy,

practice custom and usage unless restrained and enjoined

from so doing.

14

The appellants assert that even assuming this properly

to be a class action, the only persons coming within said

class are citizens of the United States residing in the Com

monwealth of Virginia who are otherwise duly qualified for

admission to the public schools, and who have applied for

and been denied such admission.

The onlv issue then, squarely presented by the pleadings,

amounts to this: Is the local school board specifically deny

ing any one of the appellees the right, which he or she

should properly have, to attend a particular school?

Whatever the policy, practice, custom and usage may be,

they are not directly relevant to the issues in this case. If

the} ̂result in segregation in the public schools solely because

of race and not because of any other factors it may be

assumed, for the purpose of this argument, that they must

be abandoned under the doctrine of the Brown case. But,

and this is the important point, neither in the Brown case,

nor in any of its companion cases, did any court decide

that any particular Negro child, or particular group of

Negro children under the jurisdiction of the appellants

were being denied the rights now guaranteed to them. In

short, it would seem obvious, that it is no longer necessary

for a trial court to reaffirm the doctrine of the Brown case

but it is necessary, and we would think mandatory, in the

interests of fairness and orderly procedure, for the trial

court to apply the doctrine of the Brown case to the facts

presented, and to decide specifically whether any apnellee

has carried the burden of showing that he or she is being

unlawfully denied admission to a particular school.

In the instant case, the court below merely reaffirmed the

doctrine of the Brozvn case and ordered the appellants to

cease the practice of segregation commencing on a specified

date. It is admitted, of course, that in any suit seeking

injunctive relief it is necessary for the trial court to fix a

15

time from which the injunction is to operate, if granted.

But it is certainly to be assumed that the basic requirements

o f civil procedure demand that each appellee prove both a

specific right and the denial of that right before he or she

obtains a decree enjoining the denial of the right.

The position here taken suggests no more than an adher-

ance to basic and well-established principles o f civil pro

cedure and it is thoroughly consistent with that part of the

implementing decision in the Brozvn case (349 U. S. 294)

which had the efifect of remanding the cases then pending to

the respective trial courts for final determination in accord

ance with the principal decision. The Supreme Court was

careful to make these provisions for the guidance of the

trial courts to which the cases were being remanded, saying

at pages 299-300:

“'Full implementation of these constitutional princi

ples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsibility

for elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems;

courts will have to consider whether the action o f school

authorities constitutes good faith implementation of the

governing constitutional principles. Because of their

proximity to local conditions and the possible need for

further hearings, the courts which originally heard

these cases can best perform this judicial appraisal.

Accordingly, we believe it appropriate to remand the

cases to those courts.

“ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees the courts

will be guided by equitable principles. Traditionally,

equity has been characterized by a practical flexibility

in shaping its remedies and by a facility for adjusting

and reconciling public and private needs. These cases

call for the exercise of these traditional attributes of

equity power. At stake is the personal interest of the

plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as

practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectu

16

ate this interest may call for elimination of a variety

o f obstacles in making the transition to school systems

operated in accordance with the constitutional princi

ples set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision. Courts

of equity may properly take into account the public

interest in the elimination of such obstacles in a system

atic and effective manner. But it should go without

saying that the vitality of these constitutional princi

ples cannot be allowed to yield simply because of dis

agreement with them.

“While giving weight to these public and private

considerations, the courts will require that the defend

ants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such

a start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defend

ants to establish that such time is necessary in the pub

lic interest and is consistent with good faith compliance

at the earliest practicable date. To that end, the courts

may consider problems related to administration, aris

ing from the physical condition of the school plant, the

school transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the

public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local

laws and regulations which may be necessary in solving

the foregoing problems. They will also consider the

adequacy of any plans the defendants may propose to

meet these problems and to effectuate a transition to a

racially nondiscriminatory school system. During this

period of transition, the courts will retain jurisdiction

of these cases.”

It must be remembered that although the Supreme Court

had established a general constitutional doctrine applicable

to all jurisdictions, procedurally its decisions were directed

to the parties in the cases before it. Previously, each case

17

had been tried in its respective trial court; abundant evidence

had been taken in each case and presumably the plaintiffs

had successfully carried the burden of proving by sufficient

facts, a right to enter a white school and a denial of that

right. Therefore, the Supreme Court, having reached its

decision, only had to direct the respective trial courts to

carry out the mandate, taking into account the various

considerations hereinabove quoted.

Now let us examine the evidence produced in the instant

case and inquire whether any one of these appellees has

proved a specific right, and that he or she is being denied

that right. Obviously, the only specific right which could

be proved in this case is the right to transfer from one public

school to another. It was suggested in Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776, that the right of any qualified individual,

regardless of race, to attend any public school of his choice

was not necessarily a general right permitting every Negro

child to attend a heretofore all-white public school. The

clear language of the decision affords no different interpre

tation for, speaking of the Supreme Court decision, the

court stated at page 777:

“ * * * It; has not decided that the federal courts are

to take over or regulate the public schools of the states.

It has not decided that the states must mix persons of

different races in the schools or must require them to

attend schools or must deprive them of the right of

choosing the schools they attend. What it has decided,

and all that it has decided, is that the state may not deny

any person on account of race the right to attend any

school that it maintains. * * * The Constitution, in

other words, does not require integration. It merely

forbids discrimination. It does not forbid such segre

gation as occurs as the result of voluntary action. It

merely forbids the use of governmental power to en

force segregation. * * *”

18

Specifically, the right exists and must be recognized when

an individual Negro child shows that he is fully qualified and

desires to attend a particular school. He must show his

qualification and right to transfer from one school to another

by making known the particular school he seeks to attend;

by showing that both the school and his residence are so

located geographically as to make his attendance there prac

ticable; by showing that the physical facilities in the par

ticular school will accommodate him; and by showing that

he is at least as well suited to attend as those already in

attendance. These factors should be easy to prove in any

particular case, if they exist, but upon the failure to prove

them, there could be no finding of specific discrimination on

the basis of race, and such a finding is essential to the

relief here sought. Therefore, to complete the requirement,

it would appear that any plaintiff or group of plaintiffs,

having affirmatively established the right to be admitted to

or to transfer to another school, must prove the denial of

that right, solely because of race.

W e believe these conclusions to be logical, well supported

by the authorities and eminently sound. If they be, then

what have the appellees proved in the instant case? Only

these facts: that they are Negroes, living within the juris

diction of the appellant school board; that the infants of the

class attend and are entitled to attend public schools; that

the school board operates elementary and high schools, here

tofore attended by white students, and elementary and high

schools heretofore attended by Negro students; and that

apparently no change in the program was contemplated as

of the date of the trial below. Not one of the appellees has

attempted to show that he is as well situated to attend an

other school as the one he is now attending. There is no evi

dence in this record giving the exact location of the various

19

schools or o f the residence of the appellees, or a description

of the public school transportation facilities now available,

or the ages and grade levels of the appellees, or the present

enrollment and maximum capacities of the various schools,

or the identity of the school into which the appellees may

wish to be transferred. None of them have even applied for

admission in another school, and as far as the record will

disclose they may all voluntarily choose to stay in the schools

they are now attending. The fact that opposing counsel,

openly and obviously representing the N A A C P through the

individuals here named as appellees, may contend otherwise

makes no difference because not one of these appellees has

testified that he seeks or will seek admission to another

school.

It is therefore perfectly clear that, unless all of the under

lying principles of civil procedure are disregarded, the con

clusion is inescapable that not one of these appellees are

entitled to any specific relief for the simple reason that they

have thoroughly and completely failed to carry the burden

o f proof.

In conclusion, it is respectively submitted that the order

from which this appeal is taken can leave these appellees

in no different posture than that in which they found them

selves immediately after the Supreme Court decision in the

Brown case. If any o f them should claim an abridgment of

the right to transfer from one school to another, the Brown

case will supply the trial court with the constitutional prin

ciple which must be applied. However, relief in the very

nature of the case must be specific and accorded only after

affirmative proof of the essential facts and circumstances

giving rise to an individual right and the denial of that right

on account of race.

20

III.

The Appellees Have Not Exhausted

Their Administrative Remedies

As already pointed out, these appellees have not applied

for admission to any particular school. They have made

only general requests that the school system be reorganized.

Thus, in fact, the appellees have not even resorted to their

administrative remedies, though the law requires that they

be exhausted before seeking injunctive relief.

Section 22-57 of the Code of Virginia (1950) provides

for appeals from the actions of school boards and reads as

follows:

“ Any five interested heads of families, residents of

the county, or city, who may feel themselves aggrieved

by the action of the county or city school board, may,

within thirty days after such action, state their com

plaint, in writing, to the division superintendent of

schools who, if he cannot within ten days after the

receipt o f the complaint, satisfactorily adjust the same,

shall, within five days thereafter, at the request of any

party in interest, grant an appeal to the circuit court

of the county or corporation court of the city or the

judge thereof in vacation who shall decide finally all

questions at issue, but the action of the school board on

questions of discretion shall be final unless the board

has exceeded its authority or has acted corruptly. The

proceedings on such an appeal shall be informal, and

no pleading shall be required, other than the complaint

hereinabove provided for. A copy of the order shall

also be entered by the clerk of the board in the minute

book of the county or city board.

“When a school is owned or operated jointly by two

or more counties, all questions arising with reference to

the school, shall be voted on by the county school boards

21

of the counties jointly, and the majority vote of the

combined boards shall be final, unless appealed from as

provided in this section. In the event o f an appeal from

the joint action of such boards, the complaint shall be

made to the division superintendents of both counties

affected, and if they cannot adjust the same as pro

vided in this section, an appeal shall be allowed to the

circuit court of the county or the corporation court of

the city or the judge thereof in vacation.”

The appellees have alleged in their complaint that they

have no remedy other than injunctive relief. The plain

language of the above quoted statute is thus ignored. This is

a class action. Therefore, all of the appellees, or any five

of them, who may have felt themselves aggrieved by any

action of the school board, could have appealed such action

to the division superintendent of schools. If their complaint

was not then adjusted, any one of them would have the

right to appeal to a court o f record. Such an appeal would

require no further pleading and the court would not be

bound by any illegal action of the local school board, or the

division superintendent.

This Court is familiar with the case of Carson v. Board

of Education of McDowell County, 227 F. (2d) 789 (4th

Cir., 1955), wherein it was held that federal courts would

not intervene until state administrative remedies had been

exhausted. The complaint in this case was filed before the

Supreme Court’s decision in the school segregation cases

and the plaintiffs requested, among other things, equal edu

cational facilities for Negro children. The district court

dismissed the action on the ground that the decisions o f the

Supreme Court had made inappropriate the relief prayed

for in the complaint. However, this Court vacated the order

on the ground that the plaintiffs were entitled to a declara

tory judgment of their right to attend school without dis

22

crimination and remanded the case to the district court.'

The district court was directed to consider state admin

istrative remedies for persons aggrieved by actions of local

school boards.

The language of this Court in the Carson case is applica

ble to the instant case. Accordingly, it is quoted fully,

beginning at pag'e 790, as follows:

“ In further consideration of the case, however, the

District Judge should give consideration not merely to

the decision of the Supreme Court but also to subse

quent legislation of the State of North Carolina pro

viding an administrative remedy for persons who feel

aggrieved with respect to their enrollment in the public

schools of the state. The Act of March 30, 1955, en

titled ‘An Act to Provide for the Enrollment of Pupils

in Public Schools,’ being chapter 366 o f the Public

Laws of North Carolina of the Session of 1955, pro

vides for enrollment by the county and city boards of

education of school children applying for admission to

schools, and authorizes the boards to adopt rules and

regulations with regard thereto. It further provides for

application to and prompt hearing by the board in the

case of any child whose admission to any public school

within the county or city administrative unit has been

denied, with right of appeal therefrom to the Superior

Court o f the county and thence to the Supreme Court

of the state. An administrative remedy is thus pro

vided by state law for persons who feel that they have

not been assigned to the schools that they are entitled to

attend; and it is well settled that the courts of the

United States will not grant injunctive relief until

administrative remedies have been exhausted. Meyers

v. Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp., 303 U. S. 41, 51,

58 S. Ct. 459, 82 L. Ed. 638; Natural Gas Pipeline Co.

of America v. Slattery, 302 U. S. 300, 310, 311, 58

S Ct 199, 82 L. Ed. 276; Hegeman Farms Corp. v.

Baldwin, 293 U. S. 163, 172, 55 S. Ct. 7, 79 L. Ed. 259;

23

United States v. Illinois Central R. Co., 291 U. S. 457,

463, 54 S. Ct. 471, 78 L. Ed. 909 ;P. F. Petersen Baking

Co. v. Bryan, 290 U. S. 570, 575, 54 S. Ct. 277, 78 L.

Ed. 505 ; Porter v. Investors’ Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461,

52 S. Ct. 617, 76 L. Ed. 1226; Matthews v. Rodgers,

284 U. S. 521, 525-526, 52 S. Ct. 217, 76 L. Ed. 447;

Prentis v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 211 U. S. 210,

29 S. Ct. 67, 53 L. Ed. 150.

“ This rule is especially applicable to a case such as

this, where injunction is asked against state or county

officers with respect to the control of schools main

tained and supported by the state. The federal courts

manifestly cannot operate the schools. All that they

have the power to do in the premises is to enjoin viola

tion of constitutional rig’hts in the operation of schools

by state authorities. Where the state law provides ade

quate administrative procedure for the protection of

such rights, the federal courts manifestly should not

interfere with the operation of the schools until such

administrative procedure has been exhausted and the

intervention of the federal courts is shown to be neces

sary. As said by Mr. Justice Stone in Matthews v.

Rodgers, supra (284 U. S. 525): T h e scrupulous

regard for the rightful independence of state govern

ments which should at all times actuate the federal

courts, and a proper reluctance to interfere by injunc

tion with their fiscal operations, require that such relief

should be denied in every case where the asserted fed

eral right may be preserved without it.’ Interference

by injunction with the schools of a state is as grave a

matters as interfering with its fiscal operations and

should not be resorted to 'where the asserted federal

right may be preserved without it.’ ”

The more recent case of Hood v. Board of Trustees, 232

F. (2d) 626 ( 4th Cir., 1956), reaffirmed the principle

ennunciated in the Carson case in the following language:

24

“ This is an appeal from the denial of a motion for

summary judgment in an action by school children for

an injunction to prevent discrimination on the ground

o f race. As the denial of motion for summary judgment

is not a final judgment in the case, we can entertain

the appeal only by considering the denial of the motion

as a denial of injunctive relief. So considered, the

order denying such relief must be affirmed, as the ad

ministrative remedies prescribed by the recent South

Carolina statute1 have not been exhausted. Carson v.

Board of Education of McDowell County, 4 Cir., 227

F. 2d 789. As plaintiffs were not entitled to injunctive

relief for this reason, we affirm the order in so far as it

denies an injunction, without passing upon other ques

tions raised in the case or approving the reasoning of

the court below in denying the motion for summary

judgment.”

On July 9, 1956, Chief Judge Thomsen of the United

States District Court for the District of Maryland in Rob

inson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s County followed

the decisions in the Carson and Hood cases, and denied

injunctive relief to the plaintiffs since they had not ex

hausted their administrative remedies. It was pointed out

that an injunction should not issue against the county school

board or the county superintendent until the plaintiffs had

appealed to the county superintendent for admission to the

school of their choice, and appealing to the State Board of

Education from an adverse decision, all in accordance with

Maryland law.

Since the appellees have merely filed a “ formal” petition

demanding the reorganization of the school system in light

of the school segregation decisions, it is perfectly obvious

that they have not exhausted their state administrative

JAn Act to amend sections 21-103 and 21-46 of the Code of Laws

of South Carolina, 1952, Approved March 8, 1956.

25

remedies. The appellees may feel aggrieved by the action

of the local school board, or many, or all of them, may have

no legal or justifiable grounds for feeling aggrieved. It is,

therefore, submitted that the instant case should be re

manded to the court below with directions that the complaint

be dismissed.

IV .

The District Court Has Abused Its Discretion by

Entering an Order Effective September, 1956

Since the decision in the school segregation cases of

May 17, 1954, approximately sixty-five cases have been

brought seeking an end to segregation in the public schools

and colleges. At least one case has been filed in each of the

seventeen states traditionally practicing some form of school

segregation except in the State of Mississippi.

The decrees entered by the three-judge district courts in

the original South Carolina and Virginia cases enjoined the

school officials from denying Negroes admission, on account

of race or color, to the schools under their jurisdiction, but

refused to set a time limit for the ending of segregation. See

particularly, Briggs v. Elliott, supra. With these cases as a

precedent, the courts in those states having large Negro

populations, although holding that segregation must cease,

have likewise declined to set any time limits.

For example, the district court in Bush v. Orleans Parrish

School Board, 138 F. Supp. 337 (U.S. D.C., E.D., La.,

1956), entered a decree in language almost identical to the

decree entered in Briggs v. Elliott, supra, and in the case

of Matthews v. Launius, 134 F. Supp. 684 (U .S. D.C. W .D.

Ark. 1955) , the district court said at pages 686-687:

26

“ In determining the question the court may and

should consider all problems related to administration

arising from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, and revi

sion of school districts and attendance areas into com

pact units to achieve a system of determining admission

to the public schools on a non-racial basis.

>fc ij«

“ This court fully realizes the immensity of the task

confronting the defendants and that because of the lack

of school finances, the crowded conditions of the present

facilities and the necessity to readjust the system that

has been followed for decades, that additional time is

necessary and the court feels that better progress may

be made at this time without the issuance of an injunc

tion, but all parties in interest should realize that the

court in the administration of the law must, within a

reasonable period of time and as soon as practicable,

require the school authorities to conduct the public

schools in the district on a racially non-discriminatory

basis.”

The court below departed from the trend of decisions

found in those states with heavy Negro populations by or

dering immediate desegregation, and in so doing, imposed

an almost impossible task on the appellants.

The evidence presented in this case conclusively showed

that the appellants could not desegregate the public schools

o f the City of Charlottesville within the time required by the

court below without disrupting the school sysem to the detri

ment of all the school children. Under such circumstances,

the court below abused its discretion by entering a “ forth

with” decree. At worst, the appellants should have been

given a reasonable time to solve local problems and make

necessary arrangements to cbpe with the decision of the

Supreme Court in the school segregation cases.

27

C O N C L U S IO N

For the reasons herein stated, it is respectfully submitted

that this case should be reversed and remanded to the court

below with the directions that it be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

J. L in d s a y A l m o n d , Jr .

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia

Attorney General of Virginia

H e n r y T. W ic k h a m

1407 State-Planters Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia

Special Assistant to the

Attorney General

Jo h n S. B a ttle

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Jo h n S. B a t t l e , Jr .

Court Square Building

Charlottesville, Virginia

Attorneys for the Appellants

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y • R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N I A