Miller-El v. Cockrell Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

May 28, 2002

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller-El v. Cockrell Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 2002. 2db211ac-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5ecbd91-1801-4899-9313-0847df6d4e21/miller-el-v-cockrell-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

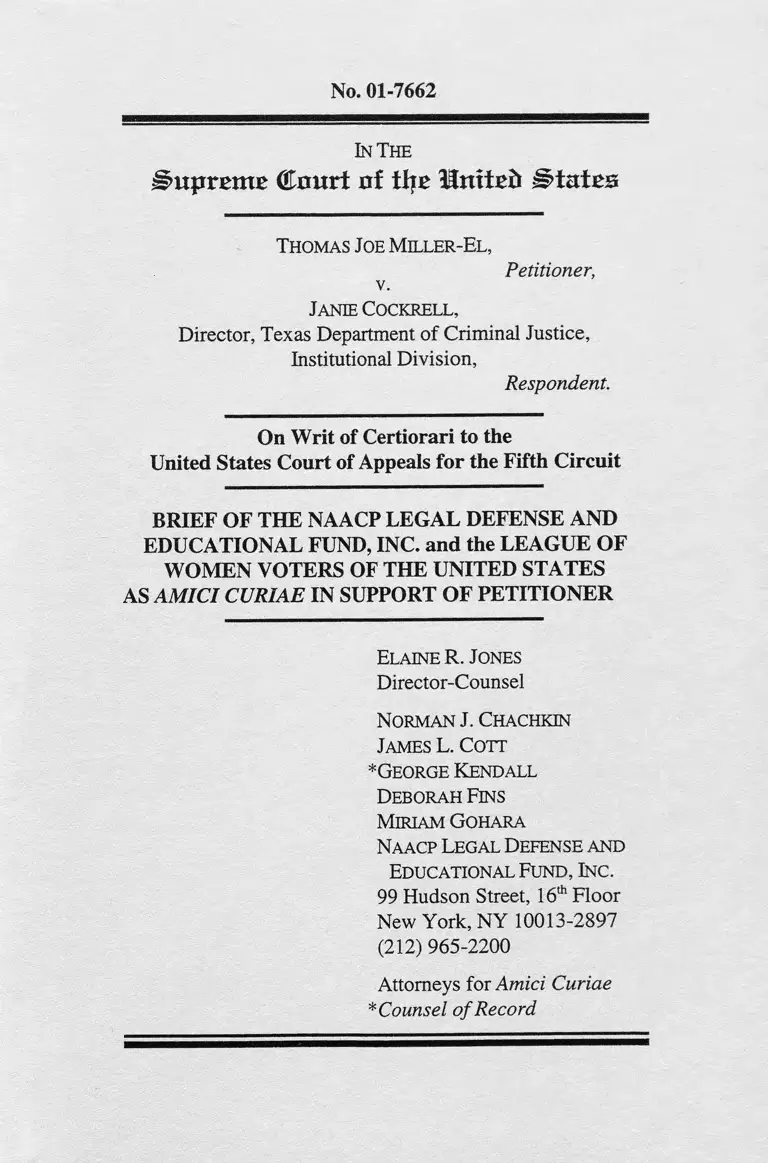

No. 01-7662

In The

Supreme Court of the Unfteh states

Thomas Joe Miller-El ,

v.

Petitioner,

Janie Cockrell,

Director, Texas Department of Criminal Justice,

Institutional Division,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. and the LEAGUE OF

WOMEN VOTERS OF THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

James L. Cott

*George Kendall

Deborah Fins

Miriam Gohara

Naacp Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, In c .

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel o f Record

-1-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities .................................................................ii

Interest of Amici Curiae ........................................................ 1

Summary o f the A rgum ent.................................. 3

ARGUM ENT............................................. 4

I. The Practice of Excluding African-

Americans from Juries Undermines

Justice and the Appearance of Ju s tic e .........4

A. The Crucial Role of Juries in a

Democratic Society ............................ 4

B. Race-Based Exclusions Harm

Jurors as Well as Defendants ........... 5

C. Racial Discrimination in Jury

Selection Discredits the Entire

Judicial System ...................................7

II. The Lower Courts’ Refusal to Recognize

Discrimination in This Case Flouts

This Court’s Mandate to End Race

Discrimination in Jury Selection ............... 11

A. From Strauder to Batson: The

Struggle to End Governmental

Exclusion of African-Americans

from Jury Service .......................... 11

Page

- i i -

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

B. The Evidence of Purposeful

Discrimination in this Case is

O verwhelm ing .............. 14

C. The Lower Courts’ Patently

Inadequate Review .............................17

1. The State Court D ecisions.........18

2. The Federal Court Decisions . . . 21

D. Batson Requires Consideration of

All Relevant Evidence of

D iscrim ination...................................23

III. The Importance of Fulfilling Batson’s

Promise ............ 24

C onclusion................................. ......................................... 28

Table of Authorities

Federal Cases:

Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 U.S. 625 (1972)................................................1

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)

Page

24

- l i i -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Federal Cases (continued)

Avery v. Georgia,

345 U.S. 559 (1953).................... ......... 12, 14, 23

Batson v. Kentucky,

476 U.S. 7 9 (1 9 8 6 )......................

Balzac v. Porto Rico,

258 U.S. 298 (1922)............................................. 6

Carter v. Jury Commission,

396 U.S. 320(1970).......................................... 1,6

Coulter v. Gilmore,

155 F.3d 912 (7th Cir. 1998) ...... ...................... 26

Duncan v. Louisiana,

391 U.S. 145 (1968)............................................. 4

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co.,

500 U.S. 614(1991)..................... ....................1,6

Georgia v. McCollum,

505 U.S. 42 (1992).................... . .......1,5, 11,23

Glasser v. United States,

315 U.S. 60 (1 9 4 2 )...... ................

Ham v. South Carolina,

409 U.S. 524 (1973).....................

........................ 4

....................... 11

-IV-

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Federal Cases (continued)

Hernandez v. New York,

500 U.S. 352(1991)............................................ 13

Horton v. Zant,

941 F.2d 1449 (11th Cir. 1991) ...... ................. 13

J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B.,

511 U.S. 127(1994).......................................... 2 ,7

Jones v. Davis,

835 F.2d 835 (11th Cir. 1988) ..................... . 13

McCleskey v. Kemp,

481 U.S. 279(1987)................................................5

Miller-el v. Johnson,

261 F.3d 445 (5th Cir. 2001) ............................. 21

Miller v. Lockhart,

65 F.3d 676 (8th Cir. 1995) ............................... 13

Neal v. Delaware,

103 U.S. 370(1880)........................... 12

Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587(1935)................................. 12

Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. 400 (1991) 6, 24, 28

-V-

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Federal Cases (continued)

Purkett v. Elem,

514 U.S. 765 (1995)............................... 14, 26, 27

Reeves v. Sanderson Plumbing Products, Inc.,

530 U.S. 133 (2000)..............................................24

Riley v. Taylor,

211 F.3d 261 (3rd Cir. 2001) ............................. 26

Rose v. Mitchell,

443 U.S. 545 (1979).......................................... 5, 8

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880)................................. 4, 11, 12

Swain v. Alabama,

380 U.S. 202 (1965)..................................... passim

Taylor v. Louisiana,

419 U.S. 522(1975).......................................... 4 ,5

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co.,

328 U.S. 217 (1946)................................................5

Turner v. Fouche,

396 U.S. 346 (1970)................................................1

Turner v. Murray,

476 U.S. 28 (1986)..................................................5

-VI-

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Federal Cases (continued)

Washington v. Davis,

462U.S. 229 (1976)............................................. 24

Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 545 (1967)................................. .......... 12

Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968)........................... ...................5

State Cases:

Burnett v. State,

27 S.W.3d 454 (Ark. App. 2 0 0 0 )........................26

Chambers v. State,

784 S.W.2d 29 (Tex. Crim. App. 1989) ........... 16

Ex parte Haliburton,

755 S.W.2d 131 (Tex. Crim. App. 1988) ......... 15

Miller-El v. State,

748 S.W.2d 459 (1992)....................................... 19

Miller-el v. State,

790 S.W.2d 351 (Tex. App. - Dallas 1990,

pet. refd) ............................................................... 16

People v. Morales,

719N.E.2d261 (111. App. 1999) 26

- V l l -

Robinson v. State,

773 So.2d 943 (Miss. App. June 27 ,2000).............27

State v. Antwine,

743 S.W.2d 51 (Mo. 1987) ................................ 19

State v. Givens,

776 So. 2d 443 (La. 2001).................................. 26

Docketed Cases:

Miller-el v. Johnson,

No. 3:96-CV- 1992-H (N.D. Tex. June 5,

2000) ..................................... 17

Miller-el v. State,

No. 69-677 (Tex. Crim. App.

Sept. 16, 1992) ......................................................20

Other Authorities:

After 30 Years, Conviction in Medgar Evers' Murder

Case (ABC NEWS, Feb. 5, 1994) ................... 10

Ken Armstrong & Steve Mills, Death Row Justice

Derailed, Chi. Trib.,Nov. 14, 1999, Sec. 1,

p. 1 6 ................................................................

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

State Cases (continued)

8

- V l l l -

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued)

David C. Baldus, et al., The Use o f Peremptory

Challenges in Capital Murder Trials: A

Legal and Empirical Analysis, 3 U. Pa. J.

Const. L. 3 (2001) ............................................... 25

Belated Justice in Mississippi, The Baltimore Sun, Feb.

8, 1994, at 14A .....................................................9

Bill Berlow, Beckwith's Old Story Sheds Light On

Today's Racial Mistrust, The Tallahassee

Democrat, Jan. 26, 2001 ...................................... 9

Leonard Cavise, The Batson Doctrine: The Supreme

Court's Utter Failure to Meet the Challenges o f

Discrimination in Jury Selection, 1999 Wis. L.

Rev. 501 (1999) ..... .............. ........... ........... 24,25

Patrick Chura, Prolepsis and Anachronism: Emmett

Till and the Historicity o f To Kill A Mockingbird,

Southern Literary Journal (Spring 2000) ... 8

Christina Cheaklos, Mississippi's 30-Year Murder

Mystery, The Atlanta Journal and Constitution,

Feb.5, 1994...........................................................10

Tanya E. Coke, Lady Justice May Be Blind, But Is She

A Soul Sister? Race-Neutrality and the Ideal o f

Representative Juries, 69 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 327

(May,1994).................................. ...................... . 10

Tim Dare, Lawyers, Ethics, and To Kill a Mockingbird,

25 Philosophy and Literature 131 (2001)............8

Bob Dylan & Jacques Levy, Hurricane (1975) .................... 9

Paul Finkelman & Stephen E. Gottlieb, eds., Toward

A Usable Past (1991) ........................................... 26

The Hurricane (Paramount Pictures 1999).............................. 9

Sheri Lynn Johnson, Batson Ethics fo r Prosecutors

and Trial Court Judges, 73 Chi.-Kent L. Rev.

475 (1998) ...................................................................25

Stephen King, The Green Mile (1997).....................................8

Harper Lee, To Kill A Mockingbird (1960)............................ 8

Steve McGonigle, Race Bias Pervades Jury Selection:

Prosecutors Routinely Bar Blacks, Study

Finds, Dallas Morning News, March 9,

1986.........................................................................7,16

Charles J. Ogletree, Just Say No!: A Proposal to

Eliminate Racially Discriminatory Uses o f

Peremptory Challenges, 31 Am. Crim. L.

Rev. 1099 (1994) ........................................................26

Robert Reinhold, After the Riots: After Police Beating

Verdict, Another Trial fo r the Jurors, N.Y. Times,

May 9, 1992 ............................................................... 10

-ix-

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued)

-X-

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued)

Richard A. Serrano & Carlos V. Lozano, Jury Picked fo r

King Trial; No Blacks Chosen, L.A.Times, Mar. 3,

1992 .................................... ............. .......................... 10

Mildred Taylor, Let the Circle Be Unbroken (1981) ......... 8

Ed Timms & Steve McGonigle, A Pattern o f Exclusion:

Blacks Rejected from Juries in Capital Cases,

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1986 ........ ............ 16

Carroll Van West, Perpetuating the Myth o f America:

Scottsboro and its Interpreters, South Atlantic

Quarterly, 36-48 (Winterl981) ........... ......................8

1

INTEREST OF AM ICI CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

(LDF) is a non-profit corporation formed to assist African-

Americans in securing their rights by the prosecution of

lawsuits. Its purpose includes rendering legal aid without cost

to African-Americans suffering injustice by reason of race who

are unable, on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on

their own. For many years, its attorneys have represented parties

and it has participated as amicus curiae in this Court, in the

lower federal courts, and in state courts.

The LDF has a long-standing concern with the influence

of racial discrimination on the criminal justice system in

general, and on jury selection in particular. We represented the

defendants in, inter alia, Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965), Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) and Ham

v. South Carolina, 409 U.S. 524 (1973); pioneered in the

affirmative use of civil actions to end jury discrimination,

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970), Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970); and appeared as amicus curiae in

Batson v. Kentucky, 416 U.S. 79 (1986), Edmonson v. Leesville

Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614 (1991), and Georgia v. McCollum,

505 U.S. 42 (1992).

The League of Women Voters of the United States is a

nonpartisan, community-based political organization that

encourages the informed and active participation of citizens in

government and influences public policy through education and

1 Letters of consent by the parties to the filing of this brief have been lodged

with the Clerk of this Court. No counsel for any party authored this brief in

whole or in part, and no person or entity other than amici made any

monetary contribution to the preparation or submission of this brief.

2

advocacy. The League is organized in one thousand

communities and in every state, with more than 120,000

members and supporters nationwide.

Founded in 1920 as an outgrowth of the 72-year struggle

to win voting rights for women in the United States, the League

has always worked to promote the values and processes of

representative government. Working for open, accountable, and

responsive government at every level; assuring citizen

participation; and protecting individual liberties established by

the Constitution - all reflect the deeply held convictions of the

League of Women Voters.

The League of Women Voters believes that democratic

government depends upon the informed and active participation

of its citizens. Racial discrimination to block citizen

participation in government offends the core values of the

League and the American system of representative government.

We believe that no person should suffer the effects of legal or

administrative discrimination. The League participated as

amicus curiae in J.E.B. v. Alabama ex. rel. T.B., 511 U.S. 127

(1994), the case that prohibited the exercise of peremptory

challenges based on the gender of the juror.

The question before this Court - whether the lower

courts erred in failing to find a violation of Batson when

presented with overwhelming evidence that prosecutors had

used race-based peremptory challenges systematically to

exclude African-Americans from the jury which convicted and

sentenced the African-American petitioner to death - presents

an important issue concerning the administration of criminal

justice. Amici believe their experience with the issue of racial

discrimination in jury selection has yielded lessons that could

be useful to the Court in resolving this appeal.

3

Justice and the perception of justice in the criminal

justice system are essential to the maintenance of order in a

democratic society. Functionally and symbolically, juries stand

as a safeguard against the State’s misuse of its powers to

confine or execute its citizens. Racial discrimination in the

selection of juries injures not only the defendant and the

African-American citizenry who are excluded from service, but

the entire community. Cynicism and disrespect for the law are

the predictable results when courts condone blatant

discrimination in the courtroom.

The facts of this case present an egregious example of

just the type of government manipulation of the jury that denies

justice and breeds disrespect for the law. The Dallas County

District Attorney’s office routinely and deliberately excluded

African-Americans from jury service through peremptory

strikes at the time this case was tried and in preceding years.

The prosecutors followed this practice in choosing the jury in

this capital case. State courts found that the same prosecutors

who systematically struck African-Americans from the jury in

this case had discriminated in the same way in other trials both

before and after petitioner’s trial. Yet instead of putting the

prosecutors’ strikes in context and weighing their assertions of

racial neutrality against evidence that bespeaks discrimination,

the courts below refused to consider such evidence.

The record here makes clear that this Court’s

determination to end invidious racial discrimination in the

selection of juries remains unfulfilled in some jurisdictions. To

assure that there is an adequate and certain check on the biased

use of peremptory challenges to exclude African-Americans

from juries, the Court needs to restate what would seem a self-

evident proposition: — that in determining whether invidious

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

4

racial discrimination has occurred, judges must consider all of

the facts and circumstances that might shed light on the issue.

ARGUMENT

I.

The Practice of Excluding African-Americans from

Juries Undermines Justice and the Appearance of

Justice

A. The Crucial Role of Juries in a Democratic

Society

This case is of great significance because juries are both

a real and symbolic bulwark against the State’s misuse of its

powers to confine or execute its citizens. “The petit jury has

occupied a central position in our system of justice by

safeguarding a person accused of crime against the arbitrary

exercise of power by prosecutor or judge.” Batson, 476 U.S. at

86. It is “an inestimable safeguard against the corrupt or

overzealous prosecutor and against the compliant, biased, or

eccentric judge,” Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145, 156

(1968), “a prized shield against oppression,” Glasser v. United

States, 315 U.S. 60, 84 (1942), that “fence[s] round and

interpose[s] barriers on every side against the approaches of

arbitrary power,” id. at 84-85.

The jury also serves as the defendant’s primary

protection against the invidious influence of race in the decision

whether he lives or dies. “[I]t is the jury that is a criminal

defendant's fundamental ‘protection of life and liberty against

race or color prejudice.’ Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S.

303, 309 (1880). Specifically, a capital sentencing jury

representative of a criminal defendant's community assures a

‘"diffused impartiality,"’ Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522,

5

530 (1975) (quoting Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S.

217, 227 (1946) (Frankfurter, J„ dissenting)), in the jury's task

of ‘expressing] the conscience of the community on the

ultimate question of life or death,’ Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391

U.S. 510, 519 (1968)." McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 310

(1987) (footnotes omitted); see also Turner v. Murray, 476 U.S.

28, 35 (1986) (“Because of the range of discretion entrusted to

a jury in a capital sentencing hearing, there is a unique

opportunity for racial prejudice to operate but remain

undetected. . . .The risk of racial prejudice infecting a capital

sentencing proceeding is especially serious in light of the

complete finality of the death sentence.”).

The risk of error in capital cases is not theoretical.

Racial prejudice can influence jurors’ determinations not only

on the ultimate question of life and death, but on the issue of

guilt itself. “It is by now clear that conscious and unconscious

racism can affect the way white jurors perceive minority

defendants and the facts presented at their trials, perhaps

determining the verdict of guilt or innocence.” Georgia v.

McCollum, 505 U.S. at 69 (O’Connor, J., dissenting). “[R]acial

discrimination in the selection of jurors ‘casts doubt on the

integrity of the judicial process,’ Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545,

556 (1979), and places the fairness of a criminal proceeding in

doubt.” Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400, 411 (1991).

B. Race-Based Exclusions Harm Jurors as

Well as Defendants

As this Court has made abundantly clear, the harm from

discriminatory exclusions of African-American jurors is not to

the defendant alone. When particular segments of the

community are excluded from serving on juries, they are

excluded from participating in an institution that stands at the

heart of our democracy. To be told that you are unfit because

6

of your race to judge your fellow citizens is to be told

unequivocally that you are a second-class citizen. Your voice is

not considered to be a voice of common sense to be interposed

between the government and the accused. Your intelligence,

your ability to be fair, your life experiences, your understanding

of your society, and your integrity are all denigrated. “People

excluded from juries because of their race are as much

aggrieved as those indicted and tried by juries chosen under a

system of racial exclusion.” Carter v. Jury Commission, 396

U.S. 320, 329 (1970).

‘“The jury system postulates a conscious duty of

participation in the machinery of justice.. . . One of its greatest

benefits is in the security it gives the people that they, as jurors

actual or possible, being part of the judicial system of the

country can prevent its arbitrary use or abuse.’” Powers v. Ohio,

499 U.S. at 406 (quoting Balzac v. Porto Rico, 258 U.S. 298,

310 (1922)). For people who are excluded from jury

participation, there is no such security, but doubt and mistrust

that the system is functioning in a fair and impartial manner.

The fact that prosecutors have long used peremptory

challenges to purge juries of African-Americans is not news in

the African-American community. When an African-American

is struck from a jury, he or she is aware that the strike may be

racially motivated. “[T]he injury caused by the discrimination

is made more severe because the government permits it to occur

within the courthouse itself,” Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete

Co., 500 U.S. at 628, the place where even-handed justice is

supposed to reign. When the exclusion comes not just in a

governmental forum, but at the instance of the government’s

representative himself, the injury is further compounded.

7

Such exclusions have led to the belief that what occurs

in the courthouse is not justice, but “white man’s justice.”2

Indeed, African-American citizens interviewed by the Dallas

Morning News at the time of Petitioner’s trial spoke of the

injury such discrimination causes. “Blacks called for jury

service say the absence of blacks on juries causes them to

question whether the judicial system is color-blind.” Id. One

such potential juror said she felt “intimidated” after she and

five other African-American jurors were eliminated by the

State, resulting in an all-white jury. Id. A former prosecutor and

Dallas county’s first African-American judge said, “[A]s

honest, law-abiding citizens who believe in God and the

American way and pay our taxes to send our children to school,

we’re still told we’re not anything of value.” Id.

C. Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection

Discredits the Entire Judicial System

Society has a paramount interest in maintaining

confidence in its criminal justice system. A democratic society

depends on the shared belief of its members that the system is

fair and impartial, that verdicts are objective and reliable, and

that punishments meted out are punishments deserved. “Wise

observers have long understood that the appearance of justice is

as important as its reality.” J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., 511

U.S. at 155 (Scalia, J., dissenting).

2 See, e.g., Steve McGonigle, Race Bias Pervades Jury Selection:

Prosecutors Routinely Bar Blacks, Study Finds DALLAS MORNING NEWS,

March 9, 1986 at A l, Cert. App. 11, at 8 (“Many families of defendants

leave the courtroom believing they have witnessed ‘white man’s justice,’

said Peter Lesser, a defense attorney and a Democratic candidate for district

attorney.”) [Citations to items in the Appendices to Petition for Writ of

Certiorari appear in the form, “Cert. App. [number of appendix], at [page

number.]”

8

It is not only African-Americans who equate racial

discrimination in the courtroom with a denial of justice. This

Court has repeatedly observed that “[r]ace discrimination within

the courtroom raises serious questions as to the fairness of the

proceedings conducted there. Racial bias mars the integrity of

the judicial system, and prevents the idea of democratic

government from becoming a reality.” Rose v. Mitchell, 443

U.S. at 556.

Indeed, one of the strongest and most enduring symbols

of injustice in this country is the trial of an African-American

defendant by an all-white jury. “To Kill a Mockingbird,”3

although a work of fiction,4 seared into the American

consciousness the grim reality of inequity in racially

exclusionary tribunals. Although that story took place in 1930s

America, the all-white jury is, unfortunately, not a relic of an

unenlightened past,5 nor is it perceived to be. Rubin

3 H a r per L e e , T o K il l A M o c k in g b ir d 233 (1960); see also Tim Dare,

Lawyers, Ethics, and To Kill a Mockingbird, 25 PHILOSOPHY AND

L it e r a t u r e 131 (2001) (“These courts were governed not by presumptions

of equality and innocence, but by prejudice and bigotry. Atticus’s plea to

the jury had been ignored and Tom had been convicted and killed as a

result.”). More recent works of fiction that have included the theme of the

biased all-white jury include Steph en K in g , T h e G r e e n M il e (1997).

4 Although fiction, the book in fact was influenced by historical events. See

Carroll Van West, Perpetuating the Myth o f America: Scottsboro and its

Interpreters, SOUTH ATLANTIC QUARTERLY, 36-48 (Winter 1981) (indicating

To Kill A Mockingbird was strongly influenced by the Scottsboro case and

the Emmett Till murder); see also Patrick Chura, Prolepsis and

Anachronism: Emmett Till and the Historicity o f To Kill A Mockingbird,

So u t h e r n L iter a r y Jo u r n a l , 1-26 (Spring 2000).

5 For example, a recent study by the Chicago Tribune found that 22% of all

African-Americans sentenced to death in Illinois between 1977 and the time

of the survey in November, 1999 were condemned by all-white juries. Ken

Armstrong & SteveMiUs, Death Row Justice Derailed, Chi.Trib., N ov. 14,

1999, Sec. l,p . 16.

9

“Hurricane” Carter’s conviction by an all-white jury was the

subject of both a popular song (Hurricane, co-written and

performed by Bob Dylan),6 and a recent movie (T h e

H u r r ic a n e (Paramount Pictures 1999)).

There continues to be widespread public suspicion about

the fairness and accuracy of verdicts in criminal cases where

all-or nearly all-white juries are impaneled in communities with

significant minority populations.7 As Justice Thomas noted

6 Here comes the story of the Hurricane,

The man the authorities came to blame

For somethin' that he never done.

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a been

The champion of the world.

* * *

And though they could not produce the gun,

The D.A. said he was the one who did the deed

And the all-white jury agreed.

* * *

To see him obviously framed

Couldn't help but make me feel ashamed to live in a land

Where justice is a game.

(.Hurricane, by Bob Dylan and Jacques Levy Copyright

© 1975 Ram's Horn Music).

7 The insidious history of white juries sitting in judgment of black

defendants represents only part of the basis for the pervasive distrust of

unrepresentative juries. On the other side of the coin are cases in which

white juries have acquitted white defendants accused of crime against

African-Americans, like the famous murders of Emmett Till and Medgar

Evers, and many others whose names never became known beyond their

own small towns. When Byron De La Beckwith was re-indicted and, in

1994, finally convicted of murdering Medgar Evers, news reports and

editorials concerning the conviction highlighted the fact that the verdict was

returned by a mixed jury, a sign of social progress. See, e.g., Belated Justice

in Mississippi, Th e BALTIMORE SUN, Feb. 8, 1994, at 14A (“De La

Beckwith was tried twice by all-white juries during the 1960s, with both

10

recently, “the public, in general, continues to believe that the

makeup of juries can matter in certain instances. Consider, for

example, how the press reports criminal trials. Major

newspapers regularly note the number of whites and blacks that

cases ending in hung juries. This time, eight of the 12 jurors were black- a

direct result of the civil rights movement Mr. Evers gave his life for- and

their decision carried a measure of credibility that all previous proceedings

lacked.”); After 30 Years, Conviction in Medgar Evers ’ Murder Case (ABC

NEWS, Feb. 5, 1994) (“A racially mixed jury did today what two all-white

juries refused to do more than a generation ago: they convicted a white man,

a segregationist. . . Byron De La Beckwith, of the crime.”); Bill Berlow,

Beckwith’s Old Story Sheds Light On Today’s Racial Mistrust, Th e

T a l l a h a s s e e D e m o c r a t , Jan. 26, 2001, at A l; Christina Cheaklos,

Mississippi’s 30-Year Murder Mystery, THE ATLANTA JOURNAL AND

C o n s t it u t io n , Feb. 5,1994, at A l (“Today, the jury deciding Beckwith’s

fate is made up of eight blacks and four whites, testament to the change

since two all-white juries failed to reach verdicts in 1964.”). Despite the

progress signaled by the Evers case, juries that excluded African-Americans

were, at the same time, prominent in the news. The Rodney King case is a

prime example. The jury which presided over the trial of the officers was

composed of ten whites, one Asian-American, and one Latina. See Richard

A. Serrano & Carlos V. Lozano, Jury Picked for King Trial; No Blacks

Chosen, L.A. TIMES, Mar. 3, 1992, at A l, A19. On April 29,1992, the jury

acquitted police officers charged with beating King of all charges. The

outcome shocked people throughout the nation, who had viewed a videotape

of the beating on television. Riots erupted all over Los Angeles in large

measure because the public perceived the jury, devoid of African

Americans, as lacking legitimacy. See Robert Reinhold, After the Riots:

After Police Beating Verdict, Another Trial fo r the Jurors, N.Y. TIMES, May

9, 1992, at A l ; see also Tanya E. Coke, Lady Justice May Be Blind, But Is

She A Soul Sister? Race-Neutrality and the Ideal o f Representative Juries,

69 N.Y.U. L. Re v . 327 (May, 1994) (“Conventional wisdom has it that Los

Angeles burned in the spring of 1992 because of a damning videotape and

a verdict of not guilty. The more precise source of public rage, however,

was that the jury which acquitted four white police officers of beating black

motorist Rodney King included no African Americans.”). The King verdict

cemented in the minds of many the idea that even at the end of the

Twentieth Century, jury exclusion and racially-biased verdicts were a

reality.

11

sit on juries in important cases. Their editors and readers

apparently recognize that conscious and unconscious prejudice

persists in our society, and that it may influence some juries.

Common experience and common sense confirm this

understanding.” Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. at 61

(Thomas, J., dissenting).8

For all these reasons, state conduct that unlawfully

manipulates a jury in a capital case so that minority juror

participation is either token or non-existent raises profoundly

important issues.

II.

The Lower Courts’ Refusal to Recognize

Discrimination in This Case Flouts This Court’s

Mandate to End Race Discrimination in Jury

Selection

This case presents not only strong proof that intentional

discrimination marred the selection of petitioner’s jury but also

a disturbing scenario of the lower courts’ ignoring both this

evidence and controlling law in concluding that no Equal

Protection violation occurred.

A. From Strauder to Batson: The Struggle to

End Governmental Exclusion of African-

Americans from Jury Service

o

In the five years after this Court’s decision in McCollum, (from June 1,

1992 to June 1, 1997) a computer search found virtually the same number

of references to “all-white” jury (192) in the New York Times, the Chicago

Tribune and the Los Angeles Times as Justice Thomas did at the time of

Batson. In the succeeding five years (June 1, 1997 to April 8, 2002) that

number was reduced, but remained substantial (114).

12

Since the adoption of the post-Civil War amendments

promising equal protection of the laws to the newly-freed

slaves, race-based exclusion from juries has been used to

eviscerate that promise. It has undermined both justice and the

perception of justice. As old, more direct methods of racial

discrimination were held unlawful, new, more subtle ones took

their place. Explicit laws forbidding African-Americans to sit

on juries, see, e.g., Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303,

were replaced with a variety of discretionary systems that

enabled officials to exclude African-Americans simply by

refusing to select them for venires. After the Court repeatedly

made clear that exclusion from venires by any means — whether

by statute or practice — would not be tolerated, see, e.g., Avery

v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S.

545 (1967), officials determined to prevent African-Americans

from actually serving on juries turned to the peremptory

challenge. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986).

At each step along this path, officials have continually

asserted that the absence of African-Americans from juries was

not the result of purposeful discrimination, but was based on

lawful reasons: there were no qualified African-Americans,

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1880); none who qualified

were known to State officials charged with composing venire

lists, Norris v. Alabama 294 U.S. 587 (1935); their views and

beliefs made them less impartial, and thus legitimately subject

to peremptory strikes, Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965).

With regard to exclusion from jury lists and venires,

this Court rejected such views and held repeatedly that

assertions that African-Americans were universally unfit for

jury service — or nearly so — were nothing more than

expressions of racial prejudice. See, e.g., Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587. Even in the face of sworn testimony from state

trial judges, jury commissioners and other officials found

“credible” by state court judges, the Court made clear that it

would not turn a blind eye to the truth of racial prejudice and

13

discrimination that permeated American life and the American

court system. “[A] finding of no discrimination was simply too

incredible to be accepted by this Court.” Hernandez v. New

York, 500 U.S. 352, 369 (1991).

In the course of these “unceasing efforts to eradicate

racial discrimination,” Batson, 476 U.S. at 85, however, the

Court stumbled. When it held in Swain that only proof of

systematic and complete exclusion of African-Americans from

juries over an extended period of time would suffice to prove

intent to discriminate in the use of peremptory challenges, it

erected what proved to be an insurmountable burden of proof.

For the next twenty years, racial discrimination remained a

notorious feature of jury selection in many American

courtrooms.9 The fact that African-Americans were virtually

openly excluded from participation in a system of justice

purporting to promise equality and fairness bred cynicism and

distrust.

When this Court decided Batson, its manifest intent was

to bring to an end - once and for all - these practices and to

restore integrity to the system. Those harmed by discriminatory

peremptory striking could now prove their cause without need

to conduct an exhaustive investigation into numerous other

9 This is demonstrated by successful Swain challenges in the late 1980's and

the 1990's. See, e.g., Horton v. Zant, 941 F.2d 1449, 1455-60 (11th Cir.

1991 )(Swain test satisfied where evidence showed prosecution struck 90%

of African American jurors in capital cases in addition to other evidence

showing prosecutor took steps to lessen minority participation in jury

system); Miller v. Lockhart, 65 F.3d 676, 680-82 (8th Cir. 1995)(Swam test

satisfied where prosecutor used ten strikes against African American jurors

in instant case and other evidence showed African Americans excluded

peremptorily in large numbers in five year period preceding Miller’s trial);

Jones v. Davis, 835 F.2d 835, 838-40 (11th Cir. 1988)(testimony of six

practicing attorneys showed black jurors routinely struck by prosecutors in

jurisdiction; Swain standard satisfied).

14

cases. The pervasive exclusion of African-Americans from

juries — known to all but not “provable” in the courts — was

to cease.

But cases like petitioner’s show why it has not ended

and will not end without this Court’s decisive intervention.

“Those of a mind to discriminate”10 found the Achilles heel in

Batson, the mask behind which continued discrimination could

hide — the “facially neutral” explanation for a peremptory

strike. In too many cases, African American jurors continued to

be excluded in large numbers, and some trial and appellate

courts not only credited nearly any reason given by the

prosecution as a purportedly race-neutral justification but also

held that it trumped all other proof suggesting racial

discrimination.11 It is clear to us that the trial bench and

reviewing courts need a clear admonition from this Court that

a facially neutral explanation for a strike may be a necessary but

is not a sufficient defense in the face of strong evidence of

purposeful racial discrimination.12

B . The Evidence of Purposeful Discrimination

in this Case is Overwhelming

10Batson, 476 U.S. at 96 (quoting Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. at 562).

11 See infra pp. 21 - 23.

12 This case is distinguishable from Purkett v. Elem, 514 U.S. 765

(1995)(per curiam), wherein the Court addressed the prosecutor’s burden of

production at stage two of the three-step Batson inquiry, as well as the issue

of the deference a federal habeas court must extend to state court fact

finding on the credibility of such offerings. This case does not concern those

questions but rather presents only the question of the scope of evidence the

court must consider at stage three after the prosecution has met its stage two

burden of production.

15

In our view, it is hard to imagine a ease with stronger

proof that a prosecutor intended to discriminate, absent an

explicit confession from the prosecutor. Without rehashing in

detail all of the evidence produced below7, which will be

presented in petitioner’s brief, it is important to summarize the

evidence:

1. The office of the prosecutor made it an explicit policy

to exclude African-Americans from juries, evidenced in its

training manual, memos used in training, and the testimony of

former prosecutors.13

2. The office had a history of vastly disproportionate

exclusion of African-Americans from both felony and capital

juries. Uncontroverted evidence showed that in a study of 100

randomly selected felony trials between 1983 and 1984 (shortly

before petitioner’s trial), 405 of 467 (87%) of African-

Americans qualified to serve were excluded by prosecutors

using peremptories. African-Americans were excluded from

juries at almost five times the rate of whites. Eighty percent of

African-American felony defendants were tried by all-white

juries. Although African-Americans comprised 18% of the

county, they were less than 4% of jurors. 72% of juries had no 13

13 Although written in the late 1960s, the memo which was incorporated

into the manual is known to have remained in the manual at least as late as

the early 1980s. Ex parte Haliburton, 755 S.W. 2d 131, 133 n. 4 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1988). The manual stated: “Who you select, and what you

qualify the panel on will depend on the type of crime, the age, the color and

sex of the Defendant. . . ” Cert. App. 8, at 301 (emphasis added). “You are

not looking for any member of a minority group which may subject him to

oppression.” Id. at 303. An earlier version used more straightforward and

offensive language, calling for the exclusion of “Jews, Negroes, Dagos,

Mexicans, or a member of any minority race.” Cert. App. 11, at 100. That

the policy was still in effect at the time of petitioner’s trial was shown by the

contemporaneous testimony of judges and lawyers who said it was widely

known in the local legal community that the Dallas County district attorneys

used peremptory strikes to exclude African-Americans.

16

African-Americans. A qualified African-American had only a

one in ten chance of serving on a jury, while a white had a one

in two chance.14

In a study of capital trials in Dallas County from 1980 -

1986, the evidence, again uncontroverted, showed that of 180

jurors in 15 trials, only 5 (3%) were African-American. Of the

remaining 57 African-Americans qualified to serve, 56 (98%)

were excluded by prosecutors using peremptory challenges.

Four of the five African-Americans sentenced to death were

sentenced by all-white juries. Qualified African-Americans had

a one in twelve chance of being selected for a jury, while whites

had a one in three chance.15

3. The prosecutors used 10 of 14 peremptory challenges

to exclude 91% of qualified African-Americans from

petitioner’s jury. Cert. App. 5, at 6.

4. The specific prosecutors who exercised the

challenges at issue in petitioner’s case were found to have

intentionally discriminated in other trials preceding and

following this case. Chambers v. State, 784 S.W.2d 29 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1989); (Dorothy Jean) Miller-el v. State, 790

S.W.2d 351 (Tex. App. - Dallas 1990, pet. ref’d).16

14 See Steve McGonigle, Race Bias Pervades Jury Selection: Prosecutors

Routinely Bar Blacks, Study Finds DALLAS MORNING N e w s , March 9,1986

at A l, Cert. App. 11, at 1.

15 See Ed Timms & Steve McGonigle, A Pattern o f Exclusion: Blacks

Rejected from Juries in Capital Cases, DALLAS MORNING NEWS, Dec. 21,

1986 at A l, Cert. App. 13, at 36.

16 The prosecutor in charge of jury selection had joined the District

Attorney’s office in 1973. He testified in Chambers that he had “never”

stricken a potential juror solely on the basis of race. Chambers v. State, 184

S.W.2d at 31. The state court refused to credit this testimony.

17

5. The prosecutors acted to exclude African-Americans

from petitioner’s jury before they knew anything about them.

Before a word of voir dire was uttered in this case, before juror

questionnaires were even completed, the prosecutors attempted

to reduce the number of African-Americans on the panel by

“shuffling” the panels. When the permitted number of shuffles

failed to achieve their goal, they requested an additional one,

citing violation of a rule the trial judge had never seen cited, let

alone enforced, in twenty-five years in the county. See V.D.

Vol. IV 1792-93.

6. The prosecutors coded the jury cards in petitioner’s

case by race. See Supplemental Briefing on Batson/Swain

Claim Based on Previously Unavailable Evidence (filed

December8,1977), Miller-El v. Johnson, No. 3:96-CV-1992-H

(N.D. Tex.), Exhibit 1, at 1-56.

7. The prosecutors questioned African-American jurors

differently than white jurors in petitioner’s case. See

Petitioner’s Brief.

8. The reasons that the prosecutors proffered for

striking African-American jurors from petitioner’s jury applied

to white jurors who were not struck.17

C. The Lower Courts’ Patently Inadequate

Review

There is simply no way to accept as “reasonable” — as

did the lower courts — the trial court’s holding that there was no

discrimination in this case. In early 1986, it was widely known

that Dallas County prosecuting attorneys used peremptory

challenges to keep African-Americans off juries, but the courts

17 Only these last two categories of evidence were contested by the State.

See Petitioner’s Brief for a detailed analysis of the voir dire.

18

apparently believed that Swain immunized their actions. Once

Batson lifted that immunity, it was plain the courts could now

provide relief to petitioner. But relief was not granted because

the courts failed to apply the clearly established law requiring

consideration of the compelling pattern and practice evidence

in the record as bearing on the question whether petitioner had

shown that the strikes constituted racially-biased conduct.

1. The State Court Decisions

The decision in Batson “requires] trial courts to be

sensitive to the racially discriminatory use of peremptory

challenges.” Batson, 476 U.S. at 99. But sensitivity requires an

open mind and an unflinching eye. Regrettably, in our view the

trial court here displayed neither.

It is difficult to tell whether the trial judge simply

misunderstood Batson, or was so unreceptive to a claim of

racial discrimination that he refused to consider compelling

facts in support of the claim.18 Whatever the reason, the trial

judge went so far as to hold, at the conclusion of the Batson

remand hearing, that petitioner had failed to make out a prima

facie case, even after the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals had

At the conclusion of the original Swain hearing, after being presented

with the training manual, the testimony of former prosecutors, the statistical

evidence of exclusion, and testimony from judges and defense lawyers in

support of the claim, the trial judge stated there was “no evidence presented

to me that indicated any systematic exclusion of blacks as a matter of policy

by the District Attorney’s office.” (Def. Exh. 1 at 146) (emphasis added).

19

explicitly held as a matter of law that one had been proven.19

Miller-El v. State, 748 S.W.2d 459, 460 (1992).

At the Batson hearing, petitioner asked the trial judge to

admit all of the evidence adduced at the pre-trial Swain hearing

for consideration of the Batson claim. The State objected,

arguing that all of the evidence of systematic exclusion should

be excluded because it was now irrelevant: under Batson, the

only evidence that was admissible was evidence about the

individual trial in which the claim was raised. See

Respondent’s Opposition to Writ o f Certiorari App. A, at 8-10.

Neither office policy nor a pattern of behavior in prior or

subsequent cases could be considered. Essentially, what this

Court had intended as a relaxing of the Swain standard was

turned on its head: although Batson held that difficult-to-obtain

proof of complete and systematic discrimination was no longer

19 The last section of the trial judge’s opinion (“Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law on Disputed Issues”) is divided into two sections: “A.

Prima Facie Case” and “B. Reasonableness of the State’s Explanations.”

Under the “Prima Facie Case” section, the trial judge held: “The evidence

did not even raise an inference of racial motivation in the use of the State’s

peremptory challenges.” Reply to Respondent's Brief In Opposition, App.

1, at 4. In an introduction to the “Reasonableness of the State’s

Explanations” section, the trial judge wrote, “Because this court does not

wish to unduly delay the progress of the appeal of this case, it required the

State to produce explanations for the exercise of all of her [sic?] peremptory

challenges, notwithstanding the court’s belief in the correctness of its ruling

on the prima facie showing issue.” Id., at 6. It also appears that the trial

judge collapsed the first and second steps in Batson, allowing the

prosecutor’s “race neutral” explanations to negate a finding of a prima facie

case. The trial judge cited a 1987 opinion from the Supreme Court of

Missouri which seemed to endorse such a procedure, directing trial judges

“to consider the prosecutor’s explanations as part of the process of

determining whether a defendant has established a prima facie case of

racially discriminatory use of peremptory challenges.” Id. at 5 {citing State

v. Antwine, 743 S.W.2d 51, 64 (Mo. 1987) (en banc)).

20

required to prove discrimination in an individual case, the State

contended that Batson barred the petitioner from using evidence

of systematic discrimination as proof of discrimination in an

individual case involving the same actors.

The state trial judge admitted the evidence “in an

abundance of caution” but made clear that he was not required

to give it any weight whatsoever in his decision See

Respondent’s Opposition to Writ o f Certiorari App. A, at 11.

His written decision recites the evidence he considered — the

“raw numbers” of strikes used (which he believed were

counterbalanced by the fact that one African-American was

allowed to sit); the “entire voir dire process” and “the

explanations for the [strikes] . . . offered at trial and at the

retrospective Batson hearing.” Reply to Respondent's Brief In

Opposition, App. 1, at 5. The pattern and practice evidence is

omitted from the list, and not mentioned anywhere else. Thus,

all the information about who the actors were, what they had

been doing, and the impact of those actions vanished. Viewing

the case in total isolation, the trial judge concluded that no

discrimination had occurred.

On appeal, the Court of Criminal Appeals looked at the

record to determine whether the prosecutor had, as the trial

court found, proffered facially race-neutral explanations for the

strikes of African-Americans. Since it found that he had, and

there was support in the record for those explanations, the

Court of Criminal Appeals went no further. The reality of what

everyone knew had occurred in Dallas County in the 1980s

simply dropped out of the case. The Court of Criminal Appeals

did not even acknowledge that the trial judge had completely

ignored its own finding that petitioner had proven a prima facie

case of discrimination. Miller-el v. State, No. 69-677 (Tex.

Crim. App. Sept. 16, 1992).

21

2. The Federal Court Decisions

The federal district court and the Fifth Circuit both

relied on the Findings and Recommendation of the United

States Magistrate Judge. Miller-el v. Johnson, No. 3:96-CV-

1992-H (N.D. Tex. June 5, 2000); Miller-el v. Johnson, 261

F.3d 445 (5th Cir. 2001). In that report, the Magistrate Judge

began by noting that it would be “an understatement” to

characterize the evidence supporting the Batson claim as

“copious and multifaceted.” Cert. App. 5, at 12. Elsewhere, he

concluded that “Petitioner has adduced a considerable amount

of evidence showing that the Dallas County District Attorney’s

office had an unofficial policy of excluding African-Americans

from jury service in years past. There is no other explanation

for the appalling statistics brought to light by the Dallas

Morning News in March 1986.” Cert. App. 5, at 20 (emphasis

supplied). Nonetheless, because of his mistaken view of a

proper Batson analysis, he recommended that relief be denied

in this case.

The Magistrate Judge held that 1) evidence that the

prosecutors were found to have discriminated in other cases is

not relevant to whether they might be offering pretextual

reasons for strikes in this case, but “is only relevant to

determining whether petitioner has established a prima facie

case under Batsonf20 2) evidence that the prosecutor

systematically questioned African-American jurors differently

than white jurors is irrelevant unless the specific line of 20

20 The fact that the specific prosecutors whose intentions were being

assessed had been found by other courts to have intentionally discriminated

was not relevant, in his view, in determining whether their reasons for

striking 10 African-Americans in petitioner’s case were sincere or

pretextual. Cert. App. 5, at 13.

22

questioning led to the exclusion of African-Americans;21 and 3)

in a disparate treatment analysis, if review of the voir dire of

each struck African-American juror revealed some difference,

no matter how minor, from comparable white jurors who were

seated, the court need not look further to see whether the overall

pattern of excluding many African-Americans who varied in

only minor ways from white jurors supported a finding of

discrimination.22

Under the Magistrate Judge’s analysis, evidence one

normally considers to be determinative in discerning the intent

of an actor — evidence of an explicit policy governing the

actions at issue, prior and subsequent behavior in similar

circumstances by the specific actors involved, behavior in the

case at hand that reveals the presence of intent — is

“irrelevant” to an evaluation of intent. Evidence of a pattern

21 The Magistrate Judge did not dispute that all African-American jurors

(and anti-death penalty white jurors) were questioned so as to make them

vulnerable to exclusion on the issue of minimum punishment. The fact that

the prosecutor was able to exclude 10 African-Americans without resort to

the minimum punishment issue does not negate this fact. Although it may

not be dispositive of the issue, the evidence certainly casts light on the

prosecutors’ determination to exclude African-Americans by whatever

means necessary.

22 The Magistrate Judge deferred to the “credibility determinationjs]” of the

state trial judge on the disparate treatment issue. Cert. App. 5, at 16. But as

we have seen, the trial judge did not consider, when making those

determinations, that the District Attorney’s office had a policy of

discrimination nor that there were “appalling” statistics proving widespread

discrimination by the office. He made the determinations in the context of

his own disinclination to believe that discrimination had occurred.

Moreover, the Magistrate Judge simply ignored the fact that the prosecutor

often gave multiple explanations for a strike, some of which were

demonstrably pretextual, i.e., they depended not on “demeanor” issues like

“hesitancy” but on simple facts (e.g., whether a juror was Catholic) which

applied equally to African-American jurors who were struck and white

jurors who were not.

23

and practice of discrimination is confined to consideration of

whether a prima facie case has been proven. The Magistrate

Judge replaced the “crippling burden of p roof’ denounced by

this Court in Batson, 476 U.S. at 92, with another one that

purports to come from Batson itself.

D. Batson Requires Consideration of All

Relevant Evidence of Discrimination

Although Batson set out a three-part procedure for

analyzing claims of discriminatory use of peremptory

challenges, it is clear that the Court did not intend those “steps”

to be isolated and unrelated inquiries, with evidence confined to

one step or another. Nor did it envision the piecemeal

examination of individual voir dires, each in isolation from the

other, as a sufficient evaluation of the presence of

discrimination.

The Court recognized that the exercise of peremptory

challenges provides the opportunity to carry out the “conscious

and unconscious prejudice [that] persists in our society,”

Georgia v. McCollum, 505 U.S. at 61 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

“[T]he defendant is entitled to rely on the fact, as to which there

can be no dispute, that peremptory challenges constitute a jury

selection practice that permits ‘those to discriminate who are of

a mind to discriminate.’” Batson, 476U.S. at 96 (quoting Aver}’

v. Georgia, 345 U.S. at 562).

Although the Court’s discussion in Batson of the kind

of evidence that would be relevant to proof of discrimination

came in the portion of the opinion discussing proof of a prima

facie case, it in no way hinted, implied, insinuated, or suggested

-- let alone stated — that such proof of discrimination should not

be considered when deciding the ultimate question of w'hether

discrimination occurred.

24

The Court has long observed that proof of purposeful

discrimination can come from many sources. “In deciding if the

defendant has carried his burden of persuasion, a court must

undertake a ‘sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and

direct evidence of intent as may be available.’ Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S.

252, 266 (1977). Circumstantial evidence of invidious intent

may include proof of disproportionate impact. Washington v.

Davis, 462 U.S.[229] at 242 [(1976)].” Batson, 476 U.S. at 93.

A defendant may rely on “any . . . relevant circumstances” and

“a combination of factors” in establishing a claim of jury

discrimination. Courts should consider “all relevant

circumstances” in deciding whether the defendant has made the

requisite showing. Batson, 476 U.S. at 96-97.23

It is clear this settled rule was not applied in this case;

if it had been, the only reasonable conclusion would be that

Petitioner met his burden of showing that racial bias motivated

the striking of the excluded African American jurors.

III.

The Importance of Fulfilling Batson’s Promise

Our final point is that the Court has more work to do to

ensure the realization of Batson’s promise. As the Court

recognized six years after Batson was decided, “[d]espite the

clarity of . . . [our] commands to eliminate the taint of racial

discrimination in the administration of justice, allegations of

bias in the jury selection process persist.” Powers v. Ohio, 499

U.S. at 402. Commentators have attributed the persistence of

23Indeed, in a different context, the Court recently confirmed the application

of this approach in age discrimination cases. See Reeves v. Sanderson

Plumbing Products, Inc., 530 U.S. 133 (2000).

25

such claims to the “toothlessness” of Batson.24 But amici

believe that the fault lies not with the decision itself, but with

the misapprehension by the lower courts of its commands.

Despite Batson’s goal of eradicating racial

discrimination in jury selection, some lower courts have

accepted questionable “race-neutral” reasons for the exclusion

of African-American prospective jurors;25 they have atomized

their analyses in a juror-by-juror discussion, refusing to look at

the voir dire as a whole, thus allowing “race-neutral” reasons to

24 See, e.g., Leonard Cavise, The Batson Doctrine: The Supreme Court’s

Utter Failure to Meet the Challenges of Discrimination in Jury Selection,

1999 Wis. L. Rev . 501 (1999) (“Only the most overtly discriminatory or

impolitic lawyer can be caught in Batson’s toothless bite and, even then, the

wound will be only superficial.”); Charles J. Ogletree, Just Say No!: A

Proposal to Eliminate Racially Discriminatory Uses o f Peremptory

Challenges, 31 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1099, 1104 (1994) (arguing that the

Batson line of cases “was misguided from the outset because it failed to

appreciate the ‘interest litigants have in continuing to discriminate by race

and gender if they can get away with it[]’”); See, e.g., David C. Baldus, et

al., The Use o f Peremptory Challenges in Capital Murder Trials: A Legal

and Empirical Analysis, 3 U. Pa. J. CONST. L. 3, 81 (2001) (noting Supreme

Court decisions prohibiting race or gender-based peremptory strikes have

had “at best [] only a marginal impact on the peremptory strike strategies of

each side” in Philadelphia, possibly because counsel for both sides “have

little expectation that the courts will sustain a claim of discrimination even

if it is based on solid evidence”); see id. (presenting statistical data reporting

the prosecutorial strike rates pre- and post-Batson against black and non

black venire members, and concluding that a sharp upswing in the use of

peremptory strikes against black venire members post-Batson may reflect

the perception that the decision would have little actual clout).

25 For a compilation of examples, see Sheri Lynn Johnson, Batson Ethics for

Prosecutors and Trial Court Judges, 73 C h i .-Ke n t L. Re v . 475, 489-90,

493-49 (1998) and Cavise, supra, n. 24, at 531-35, 553.

26

justify patterns of striking virtually all black veniremembers;26

and, in cases like petitioner’s, they have refused to consider

extensive evidence bearing on the issue of the prosecutor’s

intent.27

But other courts have found in Batson ample tools to

hold prosecutors accountable for their race-based exclusions.

For example, the Seventh Circuit had no trouble recognizing

that Batson required the consideration of all evidence in a case.

Coulter v. Gilmore, 155 F.3d 912, 921 (7th Cir. 1998) (“The

Batson decision makes it clear that, one way or another, a trial

court must consider all relevant circumstances before it issues

a final ruling on a defendant’s motion.”).28 The Third Circuit

has recognized that a history of discrimination by the

prosecutor’s office is probative. Riley v. Taylor, 277 F.3d at

283-84. Other courts have found disparate treatment despite a

lack of total identity in juror responses.29 Still others have

“6 See Charles J. Ogletree, Supreme Court Jury Discrimination Cases and

State Court Compliance, Resistance and Innovation, in TOWARD A USABLE

PAST 339, 349 (Paul Finkelman & Stephen E. Gottlieb eds., 1991) at 352

(“State trial courts frequently accept prosecutorial explanations that,

although somewhat plausible, have a disparate effect on minorities and

therefore may become convenient excuses for rationalizing challenges

against minorities.”).

27 See e.g., Riley v. Taylor, 277 F.3d 261, 283-84 (3rd Cir. 2001)(en banc).

28 See also, e.g., State v. Givens, 776 So. 2d 443, 449 (La. 2001) (holding

that a defendant “may offer any facts relevant to the question of the

prosecutor's discriminatory intent.. .[which] include, but are not limited to,

a pattern of strikes . . . against members of a suspect class, . . . the

composition of the venire and of the jury finally empaneled, and any other

disparate impact upon the suspect class”).

29 See, e.g., Burnett v. State, 27 S.W.3d 454 (Ark. App. 2000); People v.

Morales, 719 N.E.2d 261 (111. App. 1999).

27

refused to credit reasons as “race-neutral” because of the pattern

of strikes in a particular case.30

Given the overwhelming and unrebutted evidence in this

record of purposeful exclusion of African American jurors in

Dallas over a significant period of time, as well as the Court’s

unbroken line of cases dating back more than 100 years prior to

the trial in this case that clearly condemns such behavior, we

can only conclude that the judges who made the findings in this

case — both the state trial judge and the Magistrate Judge —

could not bring themselves to apply the law that plainly required

that this evidence be considered at Batson’s stage three. They

acted as if the history of jury discrimination documented in

scores of opinions from this Court, did not exist, as if behavior

was not evidence of intent, as if no action had any relationship

to any other — as if they had walked into what was plainly a

30 Robinson v. State, 773 So.2d 943, 949 (Miss. App., June 27, 2000)

(“[B]ased on our review of this record, we find the reasons offered by the

State to be so contrived, so strained, and so improbable, that we are

persuaded that they unquestionably fall within the range of those

‘implausible or fantastic justifications’ mentioned in Purkett v. Elem that

ought to ‘be found to be pretexts for purposeful discrimination.’ Purkett v.

Elem, 514 U.S. 765, 768 (1995).”). In Robinson, the state used 7 of 10

peremptory challenges to exclude prospective African-American jurors.

Reasons proffered by the prosecution were 1) perceived hostility to the

prosecution; 2) possible irresponsibility evidenced by the fact that the

questionnaires showed the jurors had children but were not married,

although the prosecutor did not know whether the jurors were divorced or

had children out of wedlock; 3) juror lived in a high crime area; 4) sleeping

during voir dire; 5) not providing answers on the questionnaire that created

uncertainty about ties to the community; 6) serving on a jury that acquitted.

The Court found that although some of the proffered reasons for striking

some of the jurors had been found to be race-neutral by prior case law,

“there is no requirement that every challenge be clearly objectionable in

order to conclude that the State was impermissibly making a calculated

effort to exclude as many African-Americans as could reasonably be done

from the jury.” Robinson, 773 So.2d at 950. Viewing the totality of the

circumstances, the Court concluded that Batson was violated. Id.

28

forest and saw only leaves. Like others throughout the sordid

history of race-based exclusions of African-American citizens

from jury service, they were apparently incapable of looking

behind the mask of racial neutrality worn by those of a mind to

discriminate. Their blindness invites cynicism and anger from

those who saw — and see — the reality of Dallas County in the

1980s: the defendants who watched African-Americans being

struck, one after another, from their juries; the African-

American citizens who arrived for jury duty only to be sent

home humiliated and intimidated; the reporters who watched

and gathered evidence of the system at work; and all the readers

of the articles that so graphically portrayed the nefarious

behavior of the prosecutors.

The decisions below are thus seriously flawed. They

failed to heed this Court’s declaration in Batson that

“[ejxclusion of black citizens from service as jurors constitutes

a primary example of the evil the Fourteenth Amendment was

designed to cure.” Batson, 476 U.S. at 85. Vigorous and

faithful application of the Court’s teaching is the least that can

be expected of state and federal judges who take the oath of

office and swear to uphold the Constitution of the United States.

The Court must make clear in this case that it shares that

expectation.

CONCLUSION

“Notwithstanding history, precedent, and the significant

benefits of the peremptory challenge system, it is intolerably

offensive for the State to imprison a person on the basis of a

conviction rendered by a jury from which members of that

person’s minority race were carefully excluded.” Powers v.

Ohio,499U .S.at430(Rehnquist,C.J.,dissenting). Petitioner’s

was just such a jury.

29

Despite clear and emphatic statements condemning race

discrimination in the selection of juries in this Court’s decisions

since 1879, prosecutors in Dallas County in 1986 openly

followed a policy of excluding African-Americans through the

use of peremptory challenges.

As our nation’s history aptly demonstrates,

discrimination injury selection will continue unless this Court

reaffirms in clear and emphatic language that review of a

Batson claim is not a shell game, but the exercise of steadfast

and resolute judicial commitment to ending race-based

exclusions of African-American citizens from participation in

the American judicial process.

Petitioner’s conviction and sentence of death should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

James L. Cott

*George H. Kendall

Deborah Fins

Mir ia m s . Gohara

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc .

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Dated: May 28, 2002

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel o f Record