Cromwell v. Maryland Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cromwell v. Maryland Brief of Appellants, 1963. 242b30a9-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5f57ecc-0052-4cb6-a7ad-58d144069d7e/cromwell-v-maryland-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

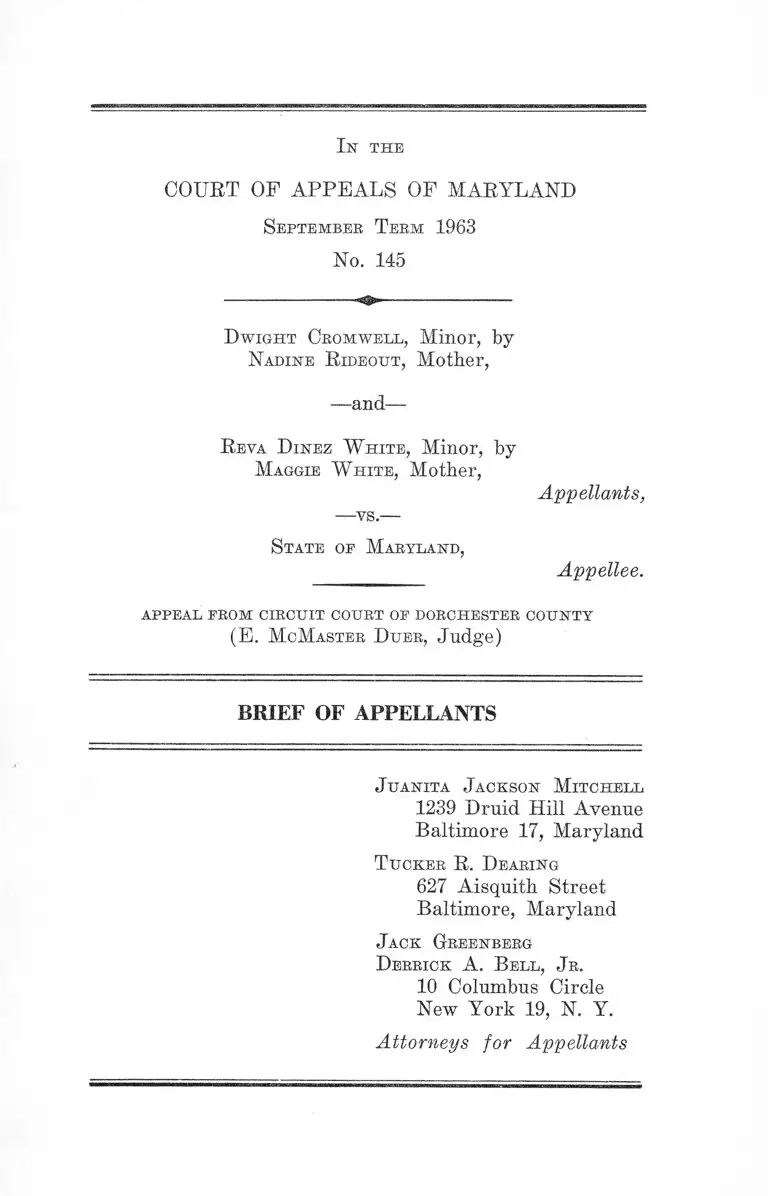

In t h e

COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

S eptem ber T eem 1963

No. 145

D w ig h t Cro m w ell , Minor, by

N adine R ideout, Mother,

—and—

R eva D in e z W h it e , Minor, by

M aggie W h it e , Mother,

—vs.—

S tate of M aryland ,

Appellants,

Appellee.

A P PE A L E E O M C IR C U IT COURT OF D O RCH ESTER C O U N T Y

(E. M cM aster D u er , Judge)

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J u an ita J ackson M itch ell

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore 17, Maryland

T u cker R . D earing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B e ll , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement of Case___ ___ _________ ____ _____________ 1

Questions Presented ............ .... .................. ...... ..... ..... . 2

Stipulated Statement of Facts ..................................... 3

A rgu m en t

PAGE

I. Freedom From, and Freedom to Protest

Against, State Imposed Restrictions Based

Upon Race and Color, and Freedom to En

gage in Group Activity for the Advancement

and Dissemination of Ideas and Beliefs in Exer

cise of These Rights Are Indispensable Aspects

of the Individual Liberty Assured Under the

Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment .......................... . 9

II. The Adjudication of Delinquency by the Ju

venile Court Was a Denial of Due Process and

Equal Protection of the Laws in That It Was

Based Upon No Evidence and the Charge Was

Too Vague to Be Defended Against .............. 14

III. The Adjudication of Delinquency by the Ju

venile Court Constituted a Denial of Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection of the Laws in That

the Decree Constituted a Punishment and

Therefore Abused the Authority and Jurisdic

tion of the Juvenile Court ............ .................. . 18

IV. The Juvenile Court Process Violated Appel

lants’ Constitutional Eights Under the Four

teenth Amendment by Its Finding of Guilt of

a Criminal Charge for Which They Could Be

Imprisoned for a Cruel and Inhuman Period

Without Providing Them With the Basic Pro

cedural Safeguards to Which Adults Charged

With Similar Crimes Would Be Entitled ......... 21

C o n c l u s io n ..................................................................................................... 24

A p p e n d ix ......... 25

T a b l e o p C a s e s :

Akers v. State, App. 51 N. E. 2d 91 .......................... 15

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U. S. 31 ................................... 9

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516................................. 10

Beauchamp v. United States, 154 F. 2d 413.................. 17

Bergen v. United States, 145 F. 2d 181.......................... 17

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ................................. 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .................. 9

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ......................... 11

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 .................................................................................. 9

Canter v. State (Tex. Civ. App.) 207 S. W. 2d 901 .... 17

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 .................10,11,13

Carmean v. People, 110 Colo. 399, 134 P. 2d 1056 .... 15

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 ..................................... 17

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569 ............................. 13

11

PAGE

m

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353 ................................. 10

Eastern R.R. Presidents Conference v. Noer Motor

Freezer, Inc., 365 IT. S. 127 ........... .......... .............. 10

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229 ............—10,11,12

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157 _____ ___________13,16

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ............................ ........ 9

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigations Commit

tee, 372 IT. S. 539 ........... -............................................... 10

Gomilion v. Lightfoot, 364 IT. S. 339 ........................... 9

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 IT. S. 683,

31 L. W. 4559 ............................................................... 9

Hambell v. Levine, 243 App. Div. 530, 275 N. Y. S.

702 ................................................... ............................... 15

Hague v. State, 87 Tex. Crim. 170, 220 S. W. 96 ....... 17

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 .............. 9

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 4 2 ....................................... 10

Hollis v. Brownell, 129 Kan. 818, 284 Pac. 388 ........... 15

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 IT. S. 460 .................. 11

In Re James, 185 Va. 335, 38 S. E. 2d 444 .............. 20, 21

In Re Madik, 233 App. Div. 12, 251 N. Y. S. 765 ....... 15

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 ............................. 9

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252 .... 23

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 ..................................... 9

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ................................. 10

Leonard v. United States, 231 F. 2d 588 ...................... 17

Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U. S. 293 ............................. 10

PAGE

IV

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141 ............................. 10

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 .............. 9

Milk Wagon Drivers v. Meadow Moor Dairies, 321 U. S.

287 .............. ...... ....................................... ..................... 11

Mill v. Brown, 31 Utah 473, 88 Pac. 609 .......................... 19

Moqnin v. State, 216 Md. 524, 140 A. 2d 914 ............ .. 19

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ............................. 10

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415................................ 10,11

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ................................. 10

N.L.R.B. v. Bradley Washfountain Co., 192 F. 2d

144 ............ ..................................................................... 17

People ex rel. Bradley v. Illinois State Reformatory,

148 111. 413, 36 N. E. 76 ................................................. 23

People ex rel. O’Connel v. Turner, 55 111. 280 ........ 23

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 .............. 9

Plumbers Union v. Graham, 345 U. S. 192 .................. 11

Purvis v. State, 133 Tex. Cr. 441, 112 S. W. 2d 186 .. 15

Re Green, 123 Ind. App. 81, 108 N. E. 2d 647 ............... 17

Re Holmes, 379 Pa. 599, 109 A. 2d 523 .......................... 17

Re Roth, 158 Neb. 789, 64 N. W. 2d 799 ...................... 17

Re Saunders, 53 Kan. 191, 36 Pac. 348 .......................... 23

Re Smith, (Okla. Crim.), 326 F. 2d 835 .......................... 23

Salinas v. United States, 277 F. 2d 588 ...................... 17

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U. S. 232 ....... 23

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................. 9

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ........................... ..... 10,13

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 ................................. 11

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 ................................. 10

State ex rel. Berry v. Superior Ct., 139 Wash. 1, 245

Pac. 409 .......................................................................... 19

PAGE

V

State ex rel. Cummingham v. Eay, 63 N. H. 406 ......... 23

State v. Freeman, 81 Mont. 132, 262 Pae. 168.............. 15

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 ........... .......... ............... 13

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R.R., 323 IJ. S. 192 .. 9

Strauder v. Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ................................. 9

Stromberg v. Carlson, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 10

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 639 ..................................... 9

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154................................. 16

Teamsters Union v. Vogt, 354 U. S. 284 ...................... 11

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ................................. 10

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ........... 15

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............. .....10,11,12,13

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U. S.

144 ............................................................................ ..... 10

United States v. National Dairy Products Corp., 372

U. S. 29 ........... ............................................................. 11

Watchtower and Bible Tract Society v. Dougherty,

337 Pa. 286, 11 A. 2d 147 ........ ..... .......................... '... 11

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 .................. 9

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................. 11

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ..................................... 11

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 536 ........................... . 13

S t a t u t e s :

U. S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment .......2, 9,16, 21

Ann. Code of Maryland (1957)

Art. 26, $52 .. .........................................................14,17

Art. 26, $54 ............................................................. 19

Art. 26, $61 .............................................................. 19

Art. 26, $66 .............................................. 19

PAGE

Y1

M iscellaneous :

PAGE

31 Am. Jur., Juvenile Courts, §53 (1958) ...................... 21

23 Harv. L. Rev. 109 ...................................................... 21

2 Wigmore on Evidence, §665 (3rd ed. 1940) .............. 23

I n t h e

COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

S eptem ber T erm 1963

No. 145

D w ig h t Cro m w ell , Minor, by

N adine R ideout, Mother,

—and—

11 e v a D in e z W h it e , Minor, by

M aggie W h it e , Mother,

— vs.—

Appellants,

S tate oe M aryland ,

Appellee.

A P PE A L FR O M C IR C U IT COURT o e D ORCH ESTER C O U N T Y

(E. M cM aster D uer , Judge)

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement of Case

This is an appeal from a decree of the Circuit Court of

Dorchester County, acting as a Juvenile Court, committing

Reva Dinez White, minor, and Dwight Cromwell, minor,

respectively to the Montrose School for Girls and the Mary

land District School for Boys after finding them to be de

linquent. The Court found that the minors were disorderly

because of their participation in civil rights demonstra

tions, and as such denied Reva Dinez White and Dwight

2

Cromwell liberty without due process and the equal pro

tection of the laws as required by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

I.

Participation in peaceful civil rights demonstrations is

constitutionally protected activity and cannot be made vio

lative of any law or ordinance without denying the appel

lants their liberty without due process and the equal

protection of the law as required by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

II.

The adjudication of delinquency by the Juvenile Court

was a denial of due process and equal protection of the

laws in that it was based upon no evidence and the charge

was too vague to be defended against.

III.

The adjudication of delinquency by the Juvenile Court

constituted a denial of due process and the equal protec

tion of the laws in that the decree of the Court constituted

a punishment and therefore abused the authority and

jurisdiction of the Court.

IV.

The Juvenile Court process violated appellants’ consti

tutional rights under the Fourteenth Amendment by its

finding of guilt of a criminal charge for which they could

be imprisoned for a cruel and inhuman period without

3

providing them with basic procedural safeguards to which

adults charged with similar crimes would be entitled.

Stipulated Statement of Facts

Reva Dinez White and Dwight Cromwell are both minor

Negro citizens of the United States. They are residents of

the State of Maryland residing in Cambridge, Maryland in

Dorchester County. They are both fifteen years of age.

Maggie White is the mother of Reva Dinez White and

has had the care and custody of Reva all her life.

Nadine Rideout is the mother of Dwight Cromwell but

Dwight Cromwell has for two or three years resided with

his grandmother, Brownie Cromwell, who resides next door

to the mother.

On April 6, May 11, May 13, May 14, May 27 and May 31,

1963, Reva Dinez White was arrested by the Cambridge

City Police Department and charged with disorderly con

duct. On May 15, 1963 following the first four arrests, a

Juvenile Petition alleging delinquency was filed in the

Circuit Court for Dorchester County, Maryland by the

State’s Attorney for Dorchester County and designated as

number 824 in said Court.

On April 6, May 11, May 13 and May 27, 1963, Dwight

Cromwell was arrested by the Cambridge City Police De

partment and charged with disorderly conduct. On May 15,

1963 following the first three arrests, a Juvenile Petition

was filed by the State’s Attorney for Dorchester County,

Maryland and the case designated as number 825 therein.

A hearing in these cases before Judge E. McMaster Duer

was set and begun on June 6, 1963. The Defendants were

represented by Tucker R. Dearing, Esq. By agreement be

tween the Court and Counsel no reporter was present, none

having been requested by the juveniles or their Counsel.

4

The hearing recessed on June 6 and resumed on June 10

with all parties present. On June 10, 1963 the Court found

Eeva Dinez White and Dwight Cromwell delinquent and

committed Eeva Dinez White to the care and custody of

Montrose School for Girls and Dwight Cromwell to the

Maryland Training School for Boys. On June 13, 1963

an Order for their appeal to the Court of Appeals for Mary

land was filed.

The first witness was Officer Eandolph Jews, a Negro

member of the Cambridge Police Department for more than

thirty years. Over objection by Defense Counsel, he tes

tified that he had known Eeva Dinez White since 1960.

He testified that she failed to attend school regularly and

that during the year 1961 he had frequently observed her

in automobiles with young men and boys as late as 3 A.M.;

he testified that he had on occasion taken her home. He

further testified that he had taken her to Police Head

quarters in 1961 where she had explained her failure to

go to school by stating she did not have proper clothing.

On one occasion the police bought her a pair of shoes.

Officer Jews testified as to profanity used by Eeva Dinez

White. Officer Jews further stated that he had had no ex

perience with and knew little about Dwight Cromwell.

Superintendent of Schools, James Busick, testified that

during the afternoon of May 27, 1963, Dwight Cromwell

and Dinez White were among the leaders of a group of

juveniles picketing the Board of Education office in Cam

bridge, Maryland; that they were singing and disturbing

employees of the office. He further testified that they ap

parently were protesting racial segregation of public

schools of Dorchester County. He stated that any of those

in the line of march could have entered the Board of

Education building and been transferred to any school in

Dorchester County they wished. He testified that Dinez

5

White and Dwight Cromwell refused an order of the Chief

of Police to stop singing and that they were subsequently

arrested by members of the Cambridge Police Department.

Over objection by Defense Counsel, Mr. Busick read from

the records of the Board of Education reports of the Prin

cipal and various teachers of Dinez White and Dwight

Cromwell. These reports, he testified, were prepared by

the teachers at his request. They were offered and, over

objection, were admitted. Photostat copies of said reports

are attached to this statement of facts. (See Appendix.)

It is conceded that none of the teachers making the reports

were present at the hearing.

Otto Cheesman, the Juvenile Probation Officer for Dor

chester County testified, over objection by Defense Counsel,

that Maggie White, mother of Dinez White, had been con

victed in Dorchester County, Maryland of assault and bat

tery and sentenced to six months in the Maryland Re

formatory for Women and the sentence suspended. Mr.

Cheesman testified that earlier in 1963 Brownie Cromwell,

the grandmother and custodian of Dwight Cromwell had

telephoned him and requested his assistance in helping to

straighten out Dwight who had gotten into bad company

and for whose future she was apprehensive. Mr. Cheesman

testified that Mrs. Cromwell had also telephoned Judge

Henry. These calls were later verified by Brownie Crom

well when she took the witness stand.

Sheriff Calvert Creighton testified that Dinez White

and Dwight Cromwell had been in his jail on many occasions

and that Dinez White had used profanity while there.

Trial Magistrate Allan M. Baird testified that he had

been present at the time of three arrests of Dinez White

and Dwight Cromwell; that Dinez White used profanity

and that her mother did not come to get her from the jail

until 3 A.M. on April 7; that he in Court dismissed Dinez

6

White and Dwight Cromwell and advised them and their

parents, Maggie White and Brownie Cromwell, that these

children should stay out of racial demonstrations.

Deputy Sheriffs Ira Johnson, Charles Frey and George

Kline testified that Dinez White was disorderly and used

profanity while in the jail, and Deputy Kline testified that

Dinez White used profanity to him and his wife on the pub

lic streets of Cambridge when he passed her.

Assistant Chief of Police James Leonard and Officer

Wallace Brooks testified that on April 6, 1963 Dinez White

and Dwight Cromwell were in the forefront of a group of

demonstrators who walked down the streets of Cambridge

four abreast; refused to obey the police officers’ order to

disperse and who assaulted the police officers by pushing

them off the sidewalk. This resulted in the arrest of the

two children on that date. They were released to the

custody of their parents without charge.

Officer William Thomas testified that on May 11, 1963

Dinez White and Dwight Cromwell entered the Recreation

Center, a pool room and bowling alley, in Cambridge and

refused to leave when requested to do so by the proprietor

and by the police. They were arrested and charged with

disorderly conduct but were again released from jail and

sent home.

Officer Philip McKelvey testified that on May 13, 1963

Dinez White and Dwight Cromwell were inside the Dizzy-

land Restaurant in Cambridge, Maryland; that they refused

to leave and the manager physically put them, and several

others, out on the sidewalk. When the two children per

sisted in sitting on the sidewalk in front of the restaurant

they were arrested. The manager of the restaurant testi

fied that he did not tell the police to arrest them, that so far

as he was concerned they could sit on the sidewalk until

doomsday, but that he would not serve them and did not

7

want them in his place of business. The two juveniles were

taken to the jail on the 13th where they remained until

8 :30 P.M. May 14. The Sheriff testified that all parents of

the juveniles were notified to come and get their children

but refused to do so. On instructions of the State’s At

torney, the Sheriff put the children out of the jail and in

structed them to go home. Instead of going home they

went to the Dorset Theater on Race Street in Cambridge,

together with several other juveniles who had also been in

jail with them. They entered the inner lobby of the theater

where a show was in progress and laid on the floor, refus

ing to get up or leave when ordered to do so by the man

ager and by Police Officers Bramble and Petrowski al

though a show was in progress and the officers testified the

group on the floor constituted a fire hazard. The children

admitted they did not attempt to purchase tickets at the

ticket office on the outside of the theater but they did state

that there was no one in the ticket window at the time.

After the children were released from jail following an

arrest on May 27 they were arrested again on May 31, 1963

by Officer Wallace Brooks of the Cambridge Police Depart

ment who testified that they entered the aforesaid Recre

ation Center, laid down and refused to leave.

Over objection by Defense Counsel, a letter from the

State Health Department was introduced relating to

Dwight Cromwell; the original letter is hereto attached.

Dinez White and Dwight Cromwell testified that on each

occasion when they were arrested they were protesting

racial segregation in the restaurant and theater. They

each testified that between May 14 and May 27 Judge W.

Laird Henry had released them, together with a group of

adults, from Dorchester County Jail and the children tes

tified that they understood Judge Henry had dismissed all

charges up to and including May 14. Judge Henry was

8

not available for the hearing. The juveniles testified that

they were singing songs but that they were not disorderly

on any occasion and, in general, they denied the testimony

of the police officers. They both admitted that on May 27

they left school without permission after lunch and went

to picket the School Board office. They were suspended for

three days for leaving school without permission. Dinez

White testified that on the occasion of the Dorset Theater

arrest, they were on their knees saying the Lord’s Prayer

and that race segregation was a cancer in the breast of

America. She testified that on most of the occasions the

arrests were made by the Cambridge City Police Depart

ment and not on formal charges instituted by the owners of

the property, except in the case of the Superintendent of

Schools and manager of Dorset Theater.

Muriel Ennals, a juvenile, testified that she was with

Dwight Cromwell and Dinez White on several of the occa

sions and that they were not disorderly.

Reverend Charles N. Bourne testified on behalf of the

children; that Dwight Cromwell went to his church and at

tended his Sunday School, but that Dinez White did not.

Reginald Robinson, Gloria Richardson, Dwight Camp

bell, Barbara Burris and Gloria Anderson testified that in

their opinion the children were not disorderly on any oc

casion when they saw them.

Nadine Rideout and Maggie White testified that the two

children were good children.

T h e a f o r e g o in g represents a true statement of facts and

is approved. Exhibits “A ” and “B” are attached hereto

and made a part hereof. (See Appendix.)

9

A R G U M E N T

I.

Freedom From, and Freedom to Protest Against, State

Imposed Restrictions Based Upon Race and Color, and

Freedom to Engage in Group Activity for the Advance

ment and Dissemination of Ideas and Beliefs in Exercise

of These Rights Are Indispensable Aspects of the Indi

vidual Liberty Assured Under the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Racial discrimination enforced, sustained or supported

by any manifestation of state authority is clearly pro

scribed by the Fourteenth Amendment barring distinctions

and classifications based upon race or color. The constitu

tional validity of this issue is foreclosed as a litigable

question.1

1 See Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 TJ. S. 683,

decided June 3, 1963, (transfers between public schools); Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, decided May 27, 1963, (public

parks and playgrounds); Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 IJ. S.

244, decided May 20, 1963 (trespass convictions where local segre

gation ordinances preempt private choice) ; Johnson v. Virginia,

373 U. S. 61, (seating in courtrooms); Burton v. Wilmington Park

ing Authority, 365 XT. S. 715, (restaurants in public buildings) ;

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 (bus terminal serving passen

gers in interstate commerce) ; Henderson v. United States, 339 IJ. S.

816, (dining ears on interstate railroad) ; Bailey v. Patterson, 369

U. S. 31 (facilities in interstate commerce); Gayle v. Browder,

352 U. S. 903 (facilities in intrastate commerce) ; Strauder v. Vir

ginia, 100 IJ. S. 303 (discrimination in jury selection) ; Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, (state enforcement of restrictive covenants);

Steele v. Louisville <& Nashville B E ., 323 U. S. 192, (discrimina

tion practiced by statutory collective bargaining agent designation

pursuant to federal statute) ; Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483, (public schools) ; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 639,

(professional schools) ; McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S.

637, (graduate schools) ; Gomilion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339,

(geographical redistricting).

10

Equally settled is the primacy in our society accorded

the unfettered exercise of the right of freedom of speech

and association. See United States v. Carotene Products

Co., 304 U. S. 144, 152, note 4; Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S.

77, 95. Included in this constitutionally privileged area

is the advancement of beliefs and ideas through group

activity, in recognition of the enhancement of effective

advocacy by group association.2

Free Trade in ideas means freedom of opportunity to

persuade to action, not merely to describe facts, Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 537. Thus protected as a part of

these guaranteed freedoms are lawful activities designed

to further one’s views.3

Broad prophylactic rules in the area of free expression

are suspect.4 And where the line drawn between per

mitted and prohibited conduct is ambiguous, it will not be

presumed that the statute curtails constitutionally pro

tected activities as little as possible. In sum, standards of

2 See NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449; Bates v. Little Bock,

361 U. S. 516; Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U. S. 293; NAACP v.

Button, 371 U. S. 415; Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation

Committee, 372 U. S. 539.

3 NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415; the dissemination of hand

bills, Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141; solicitation of political

allies; Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 42; proselytism, Cantwell v.

Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296; silent display of convictions, Strom-

berg v. Carlson, 283 U. S. 359; peaceful picketing, Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 U. S. 88; protection against prior censorship, Near

v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697; petition state legislature to redress

grievances against enforced racial discrimination, Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229; solicitation of governmental action,

Cf. Eastern B.B. Presidents Conference v. Noer Motor Freezer,

Inc., 365 U. S. 127, 138.

4 See Near v. Minnesota, supra; Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S.

479; Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U. S. 293; Speiser v. Randall, 357

U. S. 513, Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290; DeJonge v. Oregon,

299 U. S. 353.

11

permissible vagueness are strict where freedom of speech

and association rights are involved.5 What was being es

poused here was clearly lawful. Edwards v. South Carolina,

supra, and cannot be suppressed under the guise of main

taining public peace. See Buchanan v. Warley, 245, IJ. S.

60; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 810 U. S. 296.

The picketing which took place was peaceful, attempts

to secure service from downtown stores was orderly, the

protestants did not interfere with lawful use of streets by

others. Picketing, of course, is more than speech, and thus

may under certain circumstances be subject to restraints

not usually applicable to the exercise of rights of freedom

of expression. But here the picketing and demonstrations

were not connected with violence, see Milk Wagon Drivers

v. Meadow Moor Dairies, 321 U. S. 287; Plumbers Union v.

Graham, 345 U. S. 192; nor was it undertaken to achieve

goals contrary to a valid state policy, Hughes v. Superior

Court, 339 U. S. 460; Teamsters Union v. Vogt, 354 U. 8.

284. What is involved here was a lawful attempt to vindi

cate a valid social goal, Watchtower and Bible Tract Society

v. Dougherty, 337 Pa. 286, 11 A. 2d 147, and the basic self-

interest of the pickets in the controversy is clearly evident.

In viewing the facts in this case, it must be remembered

what is at stake. A group of citizens joined together to show

the public, and the officials of Cambridge, Maryland, their

concerted dissatisfaction with and opposition to racial

discrimination. They did not control any of the great

modern media of communications such as newspapers, radio

or television stations, or public office. But they could carry

5 See United States v. National Dairy Products Corp., 372 U. S.

29; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284; NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S.

415; Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147; Winters v. New York,

333 U. S. 507, 509-510, 517-518; Thornhill v. Alabama, supra.

12

placards, sing, pray, request the use of facilities, and walk

upon the streets of Cambridge evidencing their objections

to the status quo. Among these citizens were minor children

who because of their race were unemancipated in more ways

than other minors. Appellants were among this group of

minors seeking equality, and an end to racial segregation.

In the present case we must apply these principles to

the following five demonstrations in which the appellants

participated:

(1) They picketed the Board of Education to protest

segregated schooling;

(2) They walked down the streets of Cambridge, with

others, protesting segregation;

(3) They entered a Recreation Center, and refused to

leave when asked by the proprietor;

(4) They “ sat-in” in a segregated restaurant, and when

physically ejected they remained in front protesting

the refusal of service;

(5) They “ sat-in” in a segregated movie theater, and

refused to leave until they were arrested.

The picketing of the Board of Education was peaceful

and orderly. The pickets were arrested when they started

to sing, which singing allegedly disturbed the Board of

Education personnel. The demonstrators were exercising

their constitutional right to free speech and the advocacy

of ideas. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra; Edwards v.

South Carolina, supra. Their singing was merely a method

of drawing attention to their presence. It was not con

tinuous or prolonged, and can hardly be deemed enough of

a disturbance to allow the police to suppress the demon

strators’ right to advocate ideas. In Edwards v. South

13

Carolina, supra, the demonstrators sang and their activity

was held to be a constitutionally protected exercise of their

rights of speech, assembly, and to petition the government

for the redress of grievances.

The walk down the streets of Cambridge was an exercise

of the right of free speech and assembly. Since it did not

interfere with the free movement of the city it was per

fectly legal activity. Like picketing, it was an exercise of

free speech and advocacy of ideas. The power to control or

regulate the orderly use of the streets by local police au

thorities cannot be misused to deprive persons of funda

mental liberty. See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 536;

cf. Cox v. Neiv Hampshire, 312 IT. S. 569, and see Staub v.

Baxley, 355 IT. S. 313. Any ordinance which is so broadly

construed and applied as to condemn lawful as well as un

lawful activity, cannot be sustained. See Thornhill v. Ala

bama, supra; Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra; Shelton v.

Tucker, supra.

Three of the demonstrations consisted of “ sit-ins” in

privately operated places of public accommodation. These

protests are to be distinguished from the activity which

this Court has deemed an unlawful trespass which decision,

along with similar decisions from two other jurisdictions, is

to be reargued before the United States Supreme Court.

Here, appellants are not charged with trespass but with

distui'bing the peace. Protests of racial discrimination do

not constitute disturbances of the peace. Garner v. Louisi

ana, 368 U. S. 157.

For these reasons we believe the demonstrations were

exercises of protected activity, and the participation of

these appellants could not be a constitutionally valid vio

lation of any law or ordinance.

14

II.

The Adjudication of Delinquency by the Juvenile

Court Was a Denial of Due Process and Equal Protec

tion of the Laws in That It Was Based Upon No Evidence

and the Charge Was Too Vague to Be Defended Against.

The Annotated Code of Maryland, Art. 26, §52 (1957),

defines the term delinquent child as follows:

(1) Violates any law or ordinance or who commits any

act which would be a crime not punishable by death

or life imprisonment;

(2) is incorrigible, ungovernable, habitually disobedient

or who is beyond control of parents . . . or other law

ful authority;

(3) habitual truant;

(4) repeatedly runs away without just cause;

(5) engage in any occupation in violation of law or who

associates with immoral or vicious persons;

(6) so deports himself as to endanger himself and others.

When we apply this statute to these children we see that

the findings of the Juvenile Court were clearly erroneous.

The minors were wrongfully arrested for participating in

anti-segregation demonstrations during April and May of

1963. After these wrongful arrests in violation of their

constitutional rights, they were brought before the Juve

nile Court where they were charged with being delinquents.

The evidence brought forth dealt with all aspects of their

prior conduct as well as their conduct in the racial demon

strations which resulted in their arrests and subsequent

adjudication of delinquency. The ultimate finding of de

linquency was based upon the minors alleged disorderly

15

conduct [in the demonstrations] to the disturbance of the

public peace. [See petitions 824 and 825 in the Circuit

Court of Dorchester County sitting as a Juvenile Court.]

These minors were adjudged delinquent solely upon section

(1) of the above quoted statute. They had violated a law or

ordinance and committed an act that would be a crime; that

being disorderly conduct to the disturbance of the public

peace. Yet, their conduct constituted no such crime since

their conduct was constitutionally protected and their ar

rests were illegal.

The Courts of most states with similar Juvenile Court

statutes have said that the evidence presented must show

that the child sought to be committed is in such a condition

or such circumstances as to be within the purview of the

statute, and the burden is on the party instituting the pro

ceedings to prove such fact by competent evidence. See

Carmean v. People, 110 Colo. 399, 134 P. 2d 1056; Hollis

v. Brownell, 129 Kan. 818, 284 Pac. 388; Akers v. State,

App., 51 N. E. 2d 91; State v. Freeman, 81 Mont. 132, 262

Pac. 168; Hambell v. Levine, 243 App. Div. 530, 275 N. Y. S.

702; In Re Madik, 233 App. Div. 12, 251 N. Y. S. 765;

Purvis v. State, 133 Tex. Cr. 441, 112 S. W. 2d 186.

There was no competent evidence in this case and the

findings constituted a denial of liberty without due process

of law. This case falls within the doctrine of Thompson v.

City of Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960), where the Supreme

Court of the United States said that a conviction based

upon no evidentiary support is invalid under the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In that case

the Court invalidated a conviction for “ loitering” and “dis

orderly conduct.” The defendant was arrested for loitering

because he was in a cafe for a half hour, not having bought

anything. The owner did not ask him to leave or ask to have

him arrested. The defendant claimed to be waiting for a

16

bus. The “ disorderly conduct” conviction rested upon the

testimony of the police that defendant was very argumenta

tive when he was arrested. The Court held that these con

victions were so totally devoid of evidentiary support as to

be in valid under the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Court followed this doctrine in Garner

v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961), where Negroes “ sitting-

in” at a lunch counter in a white section were convicted of

disturbing the peace. The statute defined the same as the

doing of specific violent, boisterous or disruptive acts, and

any other act in such a manner as to unreasonably disturb

or alarm the public. Upon their failure to leave they were

arrested by the police. The Court reversed the convictions

saying peacefully sitting in places where racial custom

decreed that petitioners should not sit was not evidence of

any crime. In Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154, the Court

reversed a breach of the peace conviction of Negroes sitting

in a white waiting room in a bus depot. The only evidence

of the crime was that they were breaking a custom that

could lead to violence.

These cases clearly establish that a conviction based

upon no evidence of crime is a denial of due process of law.

The activities engaged in by the appellants were not crimi

nal in nature, and merely participating could not constitute

disorderly conduct or any other crime. Without an affirma

tive showing of instances of disorderly conduct aside from

those actions necessarily included in participation in these

demonstrations a criminal finding of disorderly conduct

cannot stand. Here there was no proof of instances of dis

orderly conduct apart from participation in the demonstra

tions, and therefore the finding of disorderly conduct by the

Juvenile Court violated due process of law.

Although, procedural requirements are partially relaxed

in a Juvenile Court, the rudiments of due process and fair

17

play must be followed. See, Re Holmes, 175 Pa. Super.

137, 103 A. 2d 454, aff’d 379 Pa. 599, 109 A. 2d 523, cert,

den. 348 U. S. 973. The procedures adopted must guarantee

the minor a fair and impartial hearing. See Re Roth, 158

Neb. 789, 64 N. W. 2d 799. Most important the minor must

be appraised of the charge against him, and the facts upon

which the charge is based must be set forth. See Re Green,

123 Ind. App. 81, 108 N. E. 2d 647; Canter v. State (Tex.

Civ. App.), 207 S. W. 2d 901; Hague v. State, 87 Tex. Crim.

170, 220 S. W. 96.

In the present case these appellants were found to be

delinquent because they were disorderly. Presumably this

meant the crime of disorderly conduct, since the statutory

definition of delinquency does not include disorderly con

duct. Therefore these minors were found to have violated

a law or ordinance. See Ann. Code of Maryland, Art. 26

§52(1) (1957). The essence of the proceeding was to deter

mine, among other things, if the appellants had violated

this criminal law. Such a proceeding is criminal in nature

and as such the rudiments of due process require that the

one accused of a crime be fully apprised of the nature and

facts of the charge against him. See Cole v. Arhansas, 333

U. S. 196 (1948); Salinas v. United States, 277 F. 2d 588

(9 Cir. 1960); Leonard v. United States, 231 F. 2d 588

(5 Cir. 1956); N.L.R.B. v. Bradley Washfountain Co., 192

F. 2d 144 (7 Cir. 1951); Beauchamp v. United States, 154

F. 2d 413 (7 Cir. 1946); Bergen v. United States, 145 F. 2d

181 (8 Cir. 1944). Yet, appellants were merely charged with

being delinquent because they were disorderly. The evi

dence brought forth at the hearing indicates that the dis

orderly conduct charge came from the various demonstra

tions. However, no one demonstration, or day, or even

event was specified. At best this charge amounts to an

assertion that appellants were disorderly during a period

18

covering over a week. Such a charge is violative of due

process. The appellants were not apprised of the specific

act or acts of disorderly conduct with which they were

charged and the facts upon which such charge or charges

rest. They were provided with no reasonable means to meet

these charges or the evidence introduced. The proceedings

amounted to a complete surprise, for which the appellants

could not reasonably be expected to prepare. Therefore,

the vagueness of the charge as to the specific facts of the

crime made the complaint deficient and violative of due

process.

III.

The Adjudication of Delinquency by the Juvenile

Court Constituted a Denial of Due Process and Equal

Protection of the Laws in That the Decree Constituted

a Punishment and Therefore Abused the Authority and

Jurisdiction of the Juvenile Court.

The Juvenile Court had no jurisdiction over the appel

lants because the Act requires a finding that the minors

need treatment available at the state training school even

if the minor does fit into the category of delinquent. This

is the justification for relaxing the ordinary criminal rules

of procedure and evidence in Juvenile Courts. The pro

ceeding is not criminal, but corrective, and it is not the

function of the Court to punish.

“ The Juvenile Act does not contemplate the punishment

of children where they are found to be delinquent. The

Act contemplates an attempt to correct and rehabili

tate. Emphasis is placed in the Act upon the desirabil

ity of providing the necessary care and guidance in

the child’s own home and while the Act recognizes that

there will be cases where hospital care or commitment

19

to a juvenile training school or other institution may

be necessary, this is all directed to the rehabilitation

of the. child concerned rather than punishment for any

delinquent conduct.” See Moquin v. State, 216 Md. 524,

528,140 A. 2d 914, 918.

Pertinent sections of the Statute read as follows:

u . . . s, child . . . shall not be charged with the commis

sion of any crime. The Judge shall then determine

whether or not such child comes within any aforesaid

terms and is, by reason thereof, in need of care or

treatment within the provision and intent of this sub

title.” [Ann. Code of Maryland, Art. 26, §54 (1957).]

“ . . . if the Judge determines that the child is not within

the jurisdiction of the Court or that the child is not

in need of care or treatment within the provisions or

intent of this sub-title, the Judge shall dismiss the

case.” [Ann. Code of Maryland, Art. 26, §61 (1957).]

“ . . . this sub-title shall be liberally construed to the end

thta such child coming within the jurisdiction of the

Judges shall receive such care, guidance and control,

preferably in his own home as will be conducive to the

child’s welfare and the best interest of the State.”

[Ann. Code of Maryland, Art. 26, §66 (1957).]

Therefore it is necessary for the Court to determine that

the minor is in need of care and treatment available at the

training school before the minor can be so committed.

Whenever possible, such minor should receive this neces

sary care in his own home. See, Mill v. Brown, 31 Utah

473, 88 Pac. 609; State ex rel. Berry v. Superior Ct., 139

Wash. 1, 245 Pac. 409. The Virginia Court, interpreting a

similar statute said,

20

“ the provisions of Chapter 28, Virginia Code 1942

(Michie), Sections 1905-1922, are protective, not penal,

and proceedings thereunder are of a civil nature, not

criminal, and are intended for the protection of the

child and society to save the child from evil tendencies

and bad surroundings, and to give the child more

efficient care and training that it may become a useful

member of society.” [See In Re James, 185 Va. 335,

338, 38 S. E. 2d 444, 447.]

The Court then went on to say:

“ The statute section 1922, provides that it shall be

liberally construed in order to accomplish the benefi

cial purposes herein set forth. There is nothing in the

record to suggest that the accused were inherently

vicious or incorrigible. To classify an infant as delin

quent because of a youthful prank, or for a mere single

violation of a misdemeanor statute or municipal ordi

nance, not immoral per se, in this day of numberless

laws and ordinances is offensive to our sense of justice

and to the intendment of the law. We cannot reconcile

ourselves to the thought that the incautious violation

of a motor vehicle law, a single act of truancy or a

departure from an established rule of similar slight

gravely is sufficient to justify the classification of the

offender as delinquent . . . ” [In Ee James, supra, 338,

447.]

In the present case the Juvenile Court made no finding

as to the needs of these minors for treatment and care, not

available at home. The sole purpose in sending these minors

to a training school was to remove them from the demon

strations. Since these demonstrations were constitutionally

protected activities they could not possibly constitute an

evil or bad surrounding from which the child should be

21

removed., Neither were these minors so incorrigible as to

require a commitment to the state training school. Their

participation in the demonstrations did not amount to crim

inal activity. Furthermore, their conduct was orderly.

Even if they had been disorderly on one occasion, this is

not enough to qualify them, for admission, to state training

school. See In Re James, supra. The decree of the Juvenile

Court amounted to a punishment for participation in pro

tected activity and was clearly beyond the jurisdiction and

power of the Juvenile Court. As such it amounts to a denial

of . due process, and equal protection of the laws.

IV.

The Juvenile Court Process Violated Appellants’

Constitutional Rights Under the Fourteenth Amendment

by its Finding of Guilt of a Criminal Charge for Which

They Could Be Imprisoned for a Cruel and Inhuman

Period Without Providing Them With the Basic Pro

cedural Safeguards to Which Adults Charged With Sim

ilar Crimes Would Be Entitled.

Superficially the Juvenile Court proceeding seems to be

a civil adjudication of the- status of the appellants. If it

were merely a finding of the needs of the appellants in light

of their conduct and environment, and for the purpose of

what is best for these juveniles, it would be a civil adjudi

cation. However, this was not the case. These minors were

adjudged delinquent because they were found to have vio

lated a law or ordinance. An adjudication resting on a

finding of criminality is inherently criminal in nature. This

view is followed in jurisdiction with similar Juvenile Court

Acts where the proceedings against the juvenile are related

to a charge of some specific criminal offense. The proceed

ings are said to retain their criminal character. See, 23

Harv. L. Rev. 109, 31 Am. Jur., Juvenile Courts, §53 (1958).

22

Where a finding of juvenile delinquency is based upon crimi

nal acts, the Juvenile Court is called upon to do more than

determine the status of the child. The Juvenile Court is

really called upon to decide the guilt or innocence of the

juvenile concerning the crime charged. It is not reasonable

to say that this determination is not a criminal proceeding

because it is done with the best interest of the juvenile in

mind. The reliabilitory nature of the proceeding is depend

ent upon the need for rehabilitation. The need for rehabili

tation and treatment is dependent upon the guilt or inno

cence of the child in regard to the criminal acts alleged.

To label a child a juvenile delinquent and treat him may

be civil in nature, but to base this adjudication upon the

doing of a criminal act colors the proceeding with criminal

overtones. A finding of delinquency based upon habitually

disobedient or ungovernable conduct, or habitual truancy,

or repeatedly running away from home, or so deporting

oneself as to endanger self or others, does not carry the

stigma of criminality. On the other hand, a finding of

delinquency based upon the violation of a law constitutes

a finding of criminality and changes the nature of the pro

ceedings from civil to criminal.

The view has generally been taken that the juvenile

statutes are not unconstitutional by reason of dispensing

with certain procedural steps and safeguards which are

usually regarded as essential in criminal prosecutions, such

as trial by jury, arraignment, plea, notice to the person,

warrant of arrest, or because of a provision requiring the

child to be a witness against himself. This generalization

applies only when the proceedings are civil in nature.

Other jurisdictions have regarded some proceedings

under these statutes to be criminal in nature, and in such

a case the absence of the usual safeguards for the protec

tion of the rights of the accused has been held to render

23

them invalid. See People ex rel. Bradley v. Illinois State

Reformatory, 148 111. 413, 36 N. E. 76; People ex rel.

O’Connel v. Turner, 55 111. 280; Re Saunders, 53 Kan. 191,

36 Pac. 348; State ex rel. Cummingham v. Ray, 63 N. H. 406.

In proceedings where the life and liberty of a juvenile delin

quent is at stake, the rules of procedure should be measured

by the gravity of the situation and the exigencies of the

case may impel, that every safeguard be given the child.

See Re Smith (Okla. Crim.), 326 P. 2d 835.

In this proceeding there was a complete disregard for

both procedural and substantive due process. There was

no provision made for a jury. There was no provision made

for a record for purposes of appeal. [The waiver of a

court reporter by counsel was made before counsel fully

realized the criminal nature of the proceeding as devel

oped.] There was no provision made for arraignment.

There was no adequate notice to the defendant of the crimi

nal charge. Most important, there was no attempt made

to adhere to the rules of evidence. Irrelevant and immate

rial evidence dealing with all aspects of the appellants prior

behavior was admitted over objection. This evidence does

not suport an inference that appellants are delinquent or

in need of treatment now. See, Schware v. Board of Bar

Examiners, 353 IT. S. 232; Konigsherg v. State Bar of

California, 353 IT. S. 252. Alleged official school records

were allowed to be read in evidence in disregard of the

hearsay rule. These records were made prior to the hearing

and strictly for the purposes of the hearing. See, 2 Wig-

more on Evidence, §665 (3rd ed. 1940).

The whole character of the hearing was so informal as

to amount to a conviction of crime ultimately leading to

an indeterminant internment in a state training school

without regard to basic procedural safeguards afforded

adults charged with similar crimes.

24

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated it is respectfully requested that

the delinquency findings of the court below be set aside,

and apjiellants, Reva Dinez White, and Dwight Cromwell,

minors, be released from the Montrose School for Girls

and the Maryland District School for Boys and returned to

the custody of their parents.

Respectfully submitted,

J u a n ita J ackson M itch ell

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore 17, Maryland

T u ck eb R. D earing

627 Aisquith Street

Baltimore, Maryland

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants

No. Petitions

IN THE

CIRCUIT COURT OF DORCHESTER COUNTY

SITTING AS A JUVENILE COURT

T@ The Honorable, The Judge of Said Court;

C. Burrnw At.tffinejr ............................................................................................ in the

C o u n ty of Dorchester, Slate of Maryland, respectfully shows that the following named child under the age of

Delinquent

eighteen years is fj'ependent

Neglected

Feeble-minded

Name Sex Race Age Living With: Parent Guardian Custodian

l i t t s Rera White ¥ . i 15 . 9«W ««. CtmUfc. .......................

03® 7 » 11®47 V b v k i Whit* ................

Address 47©. High S t a * CawlsrlSg®*. M,

For the reason that on *^prr] <?, ‘ t « r 11» Is* 13. htajr.14, IVfeJ in the County aforesaid ,

th® s a id Dine® Ret® S M t e a c t « d i » a d i■ • rS atri* w u m w t o th e d is tu r b a n c e o f t i i« p u b l i c

IN THE MATTER OF

HIMXZ RffH WHITS.

t Ex Parte.

Your petitioner, therefore, prays said Court to pass an order directing summons to be served upon said G e @ rg ® C e r w i s h e n d

White

and requiting ^aid «.hiid^ P ia ® g S U l l . ------

to be brought before said Court at some certain time and place, to be named in said order, »<• show chum d anv there he. whv the matter of

said petition may not be determined as herein prayed.

Respectfully submitted,

PKTITIONKR ...........

(">) C. Sum aa Mac®

AriD̂ F.'ss Court Lane Caaferidg®, I f c i y l l i i

Stale of Maryland, Dorchester County, To-wit:

I hereby tf-rtifv that before the undersigned, Clerk of the Circuit Court for Dorchester County, personally appeared the aboved named

petitioner, C . H u m * * M&Ce .this / J ^ V f" day of t f c y , 19§J ,

and made oath in due form of law that the matters and facts se? forth in the aforegoing petition are true as therein stated to the best

of M * information, knowledge and belief. ̂ / J

' SJ l l ............ .

J

Upon the aforegoing petition and affidavit, it is by the Court, this . ...... I J N H s . . ................. day o f................... t f c g . .....................

19 ordered that a summon* issue directed to and requiring the Sheriff of Dorchester County to serve upon ...

f e s s l . ? ........................ ...... ................................................a copy of this petition ®nd ord«?r hikS a summon® to be nftd ®pptm lie fora

said Court on the 3 ® f # ..................day of ...... , . • , at m m ........... .... o'clock. A M,

at , ,. * , In aald County; and l« Is forth*? sedated thj| tald IWier iff bring nr eauae itrt be brought. Ilia aald

H i m m JUnra W lAfc« ........................ ........... ........................................ ..before this Court at the time end p h w above designated (or (ha

heating o( ilia matter of said (Million. |r'

True C

T«tt

CT : / ' /

LLi**- L jtli’, iXl u

* 1*2. It h* J L m/ v v Q..a..............

" Judge of the Circuit Court oMlorchestrr County,

•tttlng se% Juvenile Court.

■ Ckrk

25

APPENDIX I

26

APPENDIX II

(See opposite) EiT3

IN THE MATTER OF

w m r r emmmuu

Ex Parte.

To The Honorable, The Judge of Said Court;

No..... 8 2 5 ......Petitions

IN THE

CIRCUIT COURT OF DORCHESTER COUNTY

SITTING AS A JUVENILE COURT

G. Bum*® S t*te*8 A tt© ra «f in the

County o f Dorchester, State nf Maryland, respectfully shows that the following named child under the age of

eighteen years is Dependent

Neglected

Feeble-minded

Name

DvJght Crosawell

Sex Race Age

M 1 15

4 -1 8 -4 1

Living Wilh: .uardian Custodian

J m m »mkM

WmM» 9 WMmmt

Address 1 £r®@® i t . t C**kride«, NA«

For the reason that on. ^ m the County aforesaid $

the **id Dwight Cromroll aei«d in a dinorsierljr BMsannr t® ffa@ disturteae® of the p tttie

pmc9«

Your petitioner. th#*r* f»>re pr *v% «sani Court to oas« ar crrlor n . m e r e :• b~ •« jSS6S!3 •*«*»**(&

Sadirte Hi<Awut

and requiring the said child p © w i g h t C r ^ » ® l l

to be brought before said Court a? some certain time and place, to be named in said order, to show au- • there be. why the matter *

said petition may not be determined as herein praved.

Respectfully submitted

mijioNER „ ^

( u ) j c. ©urn&K Ifece

a d d r e s s C « w r t L o s e B l d g . » C a a & r i d g e , S i , .

Slate ©f Maryland, Dorchester County, To-wit:

I hereby certify that !>efore the undersigned. Clerk of the Circuit Court for Dorchester ( n»mtv personaliv appeared the aboved named

petitioner. C . B u n i M >fece , hls / ( ' CC dav ... ^ F i9 &$

and made oath in due farm of law that th*' matters and facta set forth in the aforegoing petition are frur as therein stated to the hear

of b i .8 information, knowledge and belief.

{ » ) P h i l i p L » C an n on

I 'pon the aforegoing petition and affidavit, it is by the Court, this .. X 3 3 t a day of

19 . ordered that a summons issue directed to and requiring the Sheriff of Dorchester County to serve upon

Hftdlft* ItldMut

C lerk.

*>F

3 * rd••id Court on the ,

•< .. C*wtMrldj<»*

Crwnr«ll

hearing of the matter of said petition.

True Copy!

I -HI . 1 '

a copy of tfiii petition and older and • tiimmom to be and appear tie fort

d#y of ............ .Ilf si o'clock, A t M,

In asld County; am! it 1* further ordered that laid Sheriff bring or cause to be brought, the laid

before this Court at the time and place above designated for the

(• ) W. L a ird H «n ry , J r .

judge of the Circuit Conti of !».»*< healrt t nunty

•{fling as a Juvenile Court

27

28

APPENDIX III

STATE OF MARYLAND

D epartm en t of H ealth

D orchester C ou nty

S tate B oard of H ealth

D epu ty S tate H ealth O fficer and

C ou nty H ealth O fficer

Maurice C. Pincoffs, M. D.

Ralph J. Young, M. D.

A. Austin Pearre, M. D.

Lloyd N. Richardson, Phar. D.

George M. Anderson, D. D. S.

A. L. Penninian, Jr., P. E.

Huntington Williams, M. D., Dr. P. H.

Perry F. Prather, M. D., C h a irm a n

C ambridge, M aryland

May 17,1963.

Judge Laird Henry, Jr.,

Court House,

Cambridge, Maryland.

Dear S ir:

Dwight Cromwell was referred to the Dorchester County

Mental Health Clinic on February 27, 1962 by Mr. Cornish,

the V. D. Investigator, after being suspected of being a

passive homosexual. He kept his appointments irregularly

until April 16, 1963 and has not been seen in the clinic

since then.

29

Very truly yours,

dlb

Eleanora Yates, R.N.

Public Health Nurse

30

E d yth e M. J olley , P rin cipal

E leanor K e n y , S ecretary

J . W arren B ald w in , V ic P r in .

N orma Green , T reasurer

MACE’S LANE HIGH SCHOOL

Cambridge, M aryland

June 3, 1963

Dinez White

No. I

In grade 7, teachers reported her as belligerent. Had to

be sent out of rooms frequently for curt remarks.

In grade 8, same behavior patterns were followed—failure

to conform to acceptable behavior patterns in classrooms,

had to be sent from rooms frequently for not doing work,

curt remarks, sarcasm to teachers— During a study period,

drew a diagram on board, labelling Mace’s Lane High

School as a jail—with principal as jailer, vice principal as

assistant jailer and all teachers as sheriffs. Stopped coming

to school before school year ended. Was not promoted that

year.

In grade 8 second year, behavior patterns exhibited were

the same—belligerent, sarcastic, stubborn, and did not apply

herself in classrooms. Stopped coming to school before

the end of the year.

In grade 9, I was informed by the guidance counselor

that she had declared her intentions to enter school this

year, to go straight in school in order to make some good

grades so that she would have a good record to take to

Cambridge High School next year, 1963-64.

31

See reports from the following teachers:

Miss Dorothy Smith

Mr. Philip Rollinson

Mr. Charles Stewart

In the second semester, has had to be sent from classes

frequently.

Edythe M. Jolley, Principal

* See individual teachers, accounts on attached sheets

32

MACE’S LANE HIGH SCHOOL

Cambridge, M aryland

June 3, 1963

Dinez was excused from class because of continued

insubo rdination.

Teacher, Charles Stewart

9th Grade Civics

An Account of Poor Conduct on the

Part of Dinez White

On Tuesday, February 5 while the 9A English class was

in order, talking occurred. I asked the class to stop all

talking. I spoke to two persons in particular. Dinez made

a reply to the statement that I had just made. I spoke to

her calmly, reminding her that she had nothing to do with

the matter. Immediately, she exploded emotionally by

jumping up and telling me the following: “You are stupid

and ignorant. You make me sick.”

Calmly, I asked her to leave the room. She did, but

before leaving she raced to the back of the room to get

her books, then back to the front of the room. Here she

threw them down and grabbed her coat and again grabbed

her books to leave the room. I asked her to report to the

office. I gave instructions to the class to continue working

and then went to the office to report the incident concerning

Dinez. Here I tried to explain to her that the affairs of

others should not upset her to the point that she must

downgrade or call others names without reason.

I asked her if she was sick, didn’t feel well, or had been

upset by something earlier. From the conversation with

her I found her to be disturbed about something. She began

to cry. I said to her that she should remain out of class at

33

least two weeks to understand her poor behavior exhibited

in class. Also, she was to apologize to the class and me for

having caused the disturbance.

Miss Dorothy A. Smith

Teacher of English 9A

Statement of Discipline

Student: Dinez White

This student had to be sent:to the office from my art class

for disciplinary action. This became necessary upon her

refusal to put away a yearbook when I requested her to do

so. In her refusal to do this she made derogatory state

ments which included the use of profanity.

Teacher: Philip Rollinson

34

Dinez White

During the current school year (1962-63) Dinez White

has been a pleasant, cooperative and helpful student in her

homeroom. She has often stayed after school to help pre

pare the room for the next day. She has listened courte

ously to advice given her by her homeroom teachers. Dinez

has, however, been tardy almost every morning.

As one of Dinez’s homeroom teachers, I have received

many unfavorable reports from other teachers concerning

her classroom activities. In her English class she became

angry because the teacher sent a student out of the room

for disorder. She said loudly before the class that the

teacher was ignorant. In her art class she cursed loud

enough to be heard by the entire class when the teacher

insisted that she stop looking at a yearbook. In her algebra

class, Dinez did no work after the first semester because

she felt it was futile. Some other teachers have stated that

Dinez’s attitude was undesirable when corrected.

In a conference with Miss Jolley, Mrs. White (Dinez’s

mother), her classroom teachers and homeroom teachers,

Dinez sulked, rolled her eyes at her mother, apologized

perfunctorily and showed little remorse for her activities.

Dinez was also involved in the organization of a group

in the school to express disapproval of a teacher. She

worked with Dwight Cromwell to organize a walk-out from

the school during a school day without permission. The

walk-out was conducted on a limited scale.

Dinez has shown little inclination to seriously take advice

given by the principal or by her homeroom teachers, even

though she listens attentively and courteously.

David Townsend

35

E d yth e M . J olley , P rin cipal

E leanor K en t , S ecretary

J. W arren B ald w in , V ic Pein.

N orma Green , T reasurer

COPY

MACE’S LANE HIGH SCHOOL

Cambridge, M aryland

(.Dwight Cromwell)

No. II

June 3, 1963

In grade 7, was a good citizen in school. Was emotionally

disturbed at home. At home took an overdose of sleeping

tablets. This had some ill effects on his school work. But

he remained an obedient student.

In grade 8, was a good citizen in school. Hid not apply

himself in classes very well. Still quite emotionally dis

turbed at home. Reported to Health Clinic weekly. Re

ported to be under psychiatric treatment. Mind didn’t seem

to be on school, but was an obedient student in school.

In grade 9, still quite emotionally disturbed. Has not

applied himself in school this year. Came in school in

September apparently against most teachers and against

the school. Tried to form a student group during school

hours to work for Civil Rights in school as he turned it.

Secured permission under false pretenses from librarian

to use work room in library for student meeting.

Continued to try to use student group in school to work

for Civil Rights for students in school and in community

project.

36

Walked halls 'unnecessarily. Was sent from teacher’s

class for incessant talk. Did no work in algebra class.

Called superintendent from school on two occasions.

Still awfully disturbed emotionally.

Edythe M. Jolley, Principal

#See individual teachers accounts on attached sheets

Oi

An Account of Poor Conduct on the Part of

Dwight Cromwell

The information which I wish to portray in your minds

concerning Dwight is merely intended to make know his

poor adjustment to school like mainly during the first semes

ter and part of the second semester.

On several occasions Dwight refused to do any assigned

work given in class. This refusal led to continual pestering

of other students throughout the class period. This pester

ing included throwing orange seeds across the room, pull

ing girls’ hair, using improper words for the classroom such

as (dam, hell, shit), jumping up whenever he felt like it,

refusing to govern himself according to school regulations

when stressed by the teacher.

In January his behavior became so disturbing that stu

dents began to complain to me that he was keeping them

from getting their work.

His conduct in class, mainly his word-for-word refusal

to do as I asked, led to a nimble between the both of us.

He was asked to report to the office. His refusal again led

to an outburst of yells by the other class members. Some

asked Dwight to obey his teacher. I pushed him toward

the door to leave and called the vice principal to let him

know that Dwight was on his way to the office.

A follow-up of his conduct was made by his mother, the

principal, and me. This was only a part of the work and

time spent by me to understand and direct his behavior.

Several home visitations had been made, conferences with

Dwight had been held, and a friendly rapport had been

established between the both of us. None of these things

seemed to help when he was under my supervision in class.

38

At the present time I am happy to say that he has im

proved in his conduct, therefore adjusting better to school

life. He has a good chance now to achieve the better things

in life. The rapport once established between us is grow

ing and I understand more of his physical, mental, home,

and social problems. Some of these problems, I think, were

the cause of his poor behavior for a continued period of

time.

(Miss) Dorothy A. Smith

39

Dwight Cromwell

In the years before the present school year Dwight

Cromwell appeared to be poorly adjusted, but he exhibited

good citizenship.

In the school year 1962-63 Dwight developed a contempt

and disregard for teachers, and their advice. He seemed

to have difficulty in conforming to any set rules, and

thought up ways to either break them or make teachers

believe that he would. He was dropped from one club be

cause of non-conformity.

Dwight became very confused as to teacher and student

status, and seemingly felt that some teachers had no right

to direct him. He became angry when he was corrected in

classes, especially if the teachers were young. Often he

ignored directions completely.

Dwight organized a student group in the school to try to

discredit one of the teachers. He misinterpreted rules, and

twisted their meanings to suit his argument. He also led

a group of students from the school grounds without per

mission, during a school day. Announcements were made

by Dwight in his homeroom concerning meetings for his

group under the guise of an English group meeting, until

his homeroom teachers discovered the nature of the meet

ings and stopped the announcements.

Dwight has been constantly counseled by his homeroom

teachers, Miss Jolley and other teachers, but he seems to

neither listen closely or heed any sound advice given.

When angered Dwight threatens to quit school, and

make disparaging remarks about the school system, and the

teachers, unless restrained.

40

Dwight often does not react rationally, and usually

blames others for any misfortune. He is often tardy in

coming to school, but feels it should he overlooked.

Dwight has not been a problem in his homeroom proper

except for tardiness and the expected playing. On a few

occasions, he has tried unsuccessfully to keep small bits

of disorder going along. He seems to love chaos, and to

hate orderly proceedings.

David Townsend