Johnson v. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1973. 457ffb34-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d5fafc40-6d12-402d-9282-373c260f2c0c/johnson-v-the-goodyear-tire-rubber-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

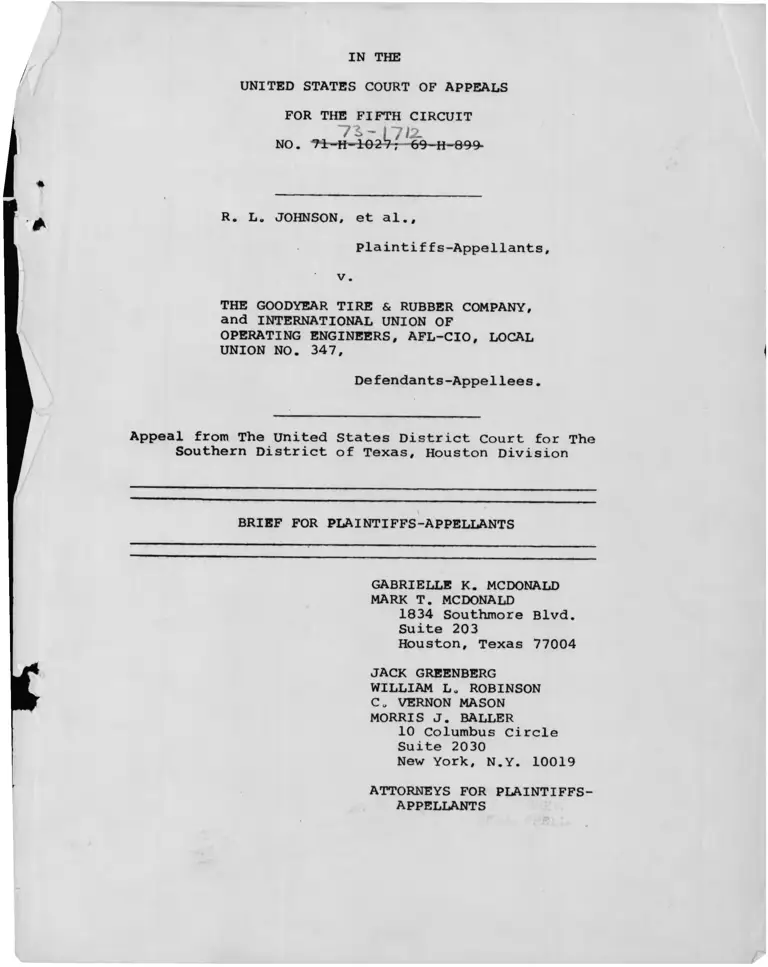

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

"73.- L 7 12-NO. ft-K>2V7 -60 -11-899-

R. L. JOHNSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY,

and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF

OPERATING ENGINEERS, AFL-CIO, LOCAL UNION NO. 347,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from The United States District court for The

Southern District of Texas, Houston Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

GABRIELLE K. MCDONALD

MARK T. MCDONALD

1834 Southmore Blvd. Suite 203

Houston, Texas 77004

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM La ROBINSON

Ca VERNON MASON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, N.Y. 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-

APPELLANTS

f

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1712

R. L. JOHNSON, et al.,

plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY,

and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF OPERATING ENGINEERS, AFL-CIO, LOCAL

UNION NO. 347,

Defendants-Appellees.

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants

R. L. Johnson, et al. in conformance with Local Rule 13 (a)

certifies that the following listed parties have an

interest in the outcome of this case. These representations

are made in order that judges of this Court may evaluate

possible disqualification or recusal:.

1. R. L. Johnson, Appellant.

2. Class of black employees and prospective em

ployees of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company whom appellant

represents.

3. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, appellee.

4. international Union of Operating Engineers,

AFL-CIO, Local Union No. 347, appellee.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iv

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW ............... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. 2

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS ................................. 5

A. Background Information ........... ........... 5

B. The Defendants' Discriminatory Practice ....... 6

1. Hiring and Job Assignment Policies ...... 6

2. Educational and Testing Requirements .... 8

3. Seniority and Transfer .................. 12

C. Plaintiff's Individual Claim ................... 13

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT THE

DEFENDANT COMPANY'S TESTING REQUIREMENTS DID

NOT DISCRIMINATE AGAINST BLACK EMPLOYEESHIRED AFTER 1957 .............................. 14

A. Plaintiff's Statistical Evidence Over

whelmingly Indicates That The Defendant

Company's Testing Requirements Had a

Severely Disproportionate Impact On

Blacks Hired After 1957 ................. 15

B. Since The Defendant Company's TestingRequirements Were Not Validated, The

District Court Erred In Finding That These

Requirements Did Not Discriminate Against

Blacks Hired After 1957 ................. 16

C. The District Court Applied ImproperStandards of Law In Reaching Its Erroneous Conclusion .............................. 17

D. This Court Should Direct The Entry Of

Appropriate Relief From The Effects Of The

Defendant Company's Unlawful Testing And

Educational Requirements ................ 19

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Page

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT THE

DEFENDANT COMPANY'S DISCRIMINATORY HIRING

PRACTICES DID NOT EXTEND BEYOND JULY 2, 1965 ___ 21

A. The District Court Erred In Finding

That The Plaintiff's Statistics Did

Not Make Out A Prima Facie Case Of

Hiring Discrimination Subsequent ToJuly 2, 1965 ............................. 21

B. The District Court Erred In Finding

That The Defendant Company's Statistics Constituted A Defense To Plaintiff's

Claim of Discrimination In HiringBeyond July 2, 1965 .... .................. 26

C. The District Court Erred In Finding That

The Defendant Company Had Not Discriminated

In Hiring Subsequent To July 2, 1965 In

Light Of Its Own Findings That The Defendant

Company Maintained Until April 22, 1971,Unvalidated Educational And Testing

Requirements That Excluded Blacks ........ 28

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO AWARD

CLASS-WIDE BACK PAY ............................ 30

A. Since The District Court Found That Members Of The Class Suffered And Are

Continually Suffering An Economic Loss

As A Result Of The Defendant Company's

Discriminatory Employment Practices, It

Erred In Failing To Award Class-Wide

Back P a y ................................. 30

B. The District Court Failed To Enunciate Any

Reason Why It Awarded The Named Plaintiff

Back Pay, And Refused To Award Back Pay To

Fourteen Other Black Labor Department

Employees Hired Prior To 1957 ............. 32

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN LIMITING THE PERIOD

FOR WHICH THE NAMED PLAINTIFF'S BACK PAY CAN BE

AWARDED TO NINETY DAYS PRIOR TO THE FILING OF

THE EEOC CHARGE ............................... 33

A. The Statute Of Limitations For Plaintiff's

§1981 Action ............................. 34

B. The 90 Day Filing Requirement Of 42 U.S.C.

2000e-5(d) Is Not A Limitation On The

Appropriate Relief 35

Page

CONCLUSION.............................................. 36

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE .................................. 38

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 444 F.2d 687

(5th Cir. 1971).................................. . 25

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co.,

437 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971).................... . 34

Brown v. Gaston Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972) cert, denied 41 U.S.

Law Week 32 53 ( 1 9 7 2 ) ............................ . 28,34

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal, 421 F.2d 888

(5th Cir. 1970) ............................ . 34

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . . . .. 15,17,29

Harkless v. Sweeny, 427 F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . .. 31

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.

1968)............................................ .. 33

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 349

F. Supp. 3 (S.D. Texas 1972) .................... . 4

Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight Co., 431 F.2d 245

(10th Cir. 1970), cert, denied 401 U.S. 954 (1971). . 28

Local 53, Int'l. Ass'n of Heat & Frost Insulators and

Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969) ...................................... . 21

Moody v. Albermarle Paper Company, F.2d___(4th Cir.

No. 72-1267, Feb. 20, 1973) ...................... . 15,17

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................ . 28

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . 18

United States v. Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d 800

(4th Cir. 1970) .................................. . 25

united States v. Georgia Power Company, ___F.2d___ (5th Cir

No• 71-3447, Feb. 14* 1972) « • • • • • • • • • • • . 9,17,19,20,25,29,31,34,35

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Contd.) Page

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456

F. 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) .................... 25,27

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F .2d 418 (5th Cir. 1972) cert, denied

4 EPD f7774 ................................. 9,17,25

Statutes and Regulations

28 U.S.C. §1291 .................................. 2

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981 ........ 3

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII .............. 3

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq........................... 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(d) 34,35

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) ............................ 31

42 U.S.C. §2000e-6(a) ............................ 31

29 C.F.R. §§1607.3 - 1607.14 ..................... 9,18

v

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether the District Court erred in ruling that

the defendant Company's testing requirements did

not discriminate against black employees hired

after 1957?

2. Whether the District Court erred in ruling that

the defendant Company's discriminatory hiring

practices did not extend beyond July 2, 1965?

3. Whether the District Court erred in failing to

award class-wide back pay?

4. Whether the District Court erred in limiting back

pay to a period of ninety days prior to the filing

of the charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case of racial discrimination in employment comes

here on appeal from a final judgment of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Texas, Houston Division entered

1/November 10, 1972.(70a) This appeal presents issues arising

from the failure of the Court below to follow the settled law of

the Supreme Court and of this Circuit and from its failure to grant

relief from the effects of defendant's racially discriminatory

hiring, placement transfer and promotion policies. This Court

has jurisdiction of the appeal under 28 U.S.C. §1291.

On May 4, 1967, plaintiff-appellant (hereinafter plaintiff

or R.L. Johnson) filed a charge of employment discrimination against

the defendant-appellee Good year Tire & Rubber Co. (hereinafter the

"Company" or "Goodyear") and against defendant-appellee Local 347

of the International Union of Operating Engineers (hereinafter

"Local 347") with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

pursuant to §706(a) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

(51a-52a). On October 23, 1968 the Commission found reasonable

cause to believe that Goodyear's testing requirements discriminated

against blacks and therefore violated the Act. (51a). After con

ciliation efforts had failed, plaintiff received his right to sue

letter on August 8 1969.(723a)

1/ This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

2

Plaintiff timely filed this suit as a 23(b)(2) class

action on behalf of himself and all other similarly situated black

employees under the 1866 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1981, and

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seg.

on September 17, 1969. (44a). Plaintiff sought injunctive relief

and back pay due to the Company's discriminatory employment

practices. (Ibid) In June 1971 present counsel filed a motion

to be substituted for prior counsel retained by the plaintiff.

(14a-15a). This motion was granted in an order of July 1971.

On September 15, 1971 plaintiff moved to amend his complaint and

join as defendant, Local 347 of the International Union of Operating

Engineers. (18a-22a). This motion was granted in October 1971 (26a),

and subsequently plaintiff filed his first amended complaint.(27a-33a).

In October 1971 defendant Local 347 filed a complaint and

sought to enjoin defendant Goodyear from amending the seniority

provision in the collective bargaining agreement by instituting a

policy that would have allowed black employees to transfer out of

the labor department and retain whatever seniority they had previously

acquired.(46a-47a). The actions were consolidated and on November

19, 1971 the District Court preliminarily enjoined the Company's

proposed changes in the seniority system pending trial on the merits

of the two causes of action. (47a).

Trial was held before the Honorable Carl 0. Bue, Jr. on

December 15, 16, 17 and 20, 1971. (82a-716a). Following submission

of post-trial pleadings, the District Court on August 10, 1972

3

handed down its memorandum opinion and findings of fact and con-27

elusions of law. (43a-69a). The Court found that black employees

hired before 1957 were the victims of discrimination in that they

were discriminatorily assigned to the labor department, and then

kept there by the Company's testing and educational requirements.

(51a). The Court also found that as to the pre-1957 black employees,

the seniority policies discriminated against them by "locking them"

into the labor department since to transfer would have resulted in

a forfeit of accrued seniority. (Ibid.) The Court permanently

enjoined the use of any testing or educational requirements as to

the pre-1957 black employees; granted them remedial seniority equal

to their plant seniority through their first transfer; and granted

back pay to R.L. Johnson - the named plaintiff - from ninety days

prior to the filing of his complaint with the EEOC until the entry

of judgment. (66a-68a).

The Court also found that black employees hired into the

labor department from 1957 up to July 2, 1955 were victims of hiring

discrimination and that the educational requirement for transfer to

or initial employment in the previously all-white departments dis

criminated against blacks. (62a). The Court granted these employees

remedial seniority and permanently enjoined any educational require

ments as to any blacks unless such requirements had received EEOC

validation. (66a-68a).

2/ The opinion is reported as Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber

Company, 349 F.Supp.3 (S.D. Texas 1972).

4

The Court found that hiring discrimination did not extend

beyond July 2, 1965 and that Goodyear's testing requirements did

not discriminate against blacks hired after 1957. (59a). The Court

also found that the statute of limitations had expired for any dis

criminatory hiring practice occuring prior to July 2, 1965.(Ibid.)

Judgment was entered November 10, 1972 and the plaintiff filed his

Notice of Appeal the same day. (70a-76a).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A . Background Information

The District Court found that Goodyear hired the named

plaintiff, R.L. Johnson, a black man, in the job classification

of laborer on September 18, 1944.(51a). For his entire employment

he has worked in the Labor Department, has never transferred to a

department other than Labor, and has never taken any of the dis

criminatory tests utilized by the defendant Company. Plaintiff

has completed 11 years of school, and has a diploma of completion

that is accepted by the defendant Company to be the equivalent of

a high school degree. (515a).

Goodyear's Houston plant is devoted exclusively to the

production of synthetic rubber. (48a). The plant is divided into

eight divisions or departments: Production, Utilities, Shipping and

Traffic, Receiving and Stores, the Laboratory or Process Control

Chemists, Oiler Group, Fire Department, and the Labor Department.(Ibid.)

_ 5 _

I

The defendant Company as of the trial date employed 405

whites and 124 blacks. Twelve of the white employees worked in

the Labor Department whereas thirty-two of the black employees

XOSworked in Labor. -(822*-; 8I-9a)-> The District Court found and it was

undisputed, that the employment positions in the Labor Department

were composed of the least skilled and lowest paid positions in

this plant. (48a). The average wage for white employees is $4.68

an hour, and $4.32 an hour for blacks, resulting in an annual

average pay difference between white and black employees of $748.80.

(805a-806a) .

B . The Defendants' Discriminatory Practices.

1. Hiring and Job Assignment Policies

Prior to 1962 it was the admitted practice of the defendant

to hire only black employees for the Labor Department and to hire

only white employees for any non-Labor Department positions. (48a;

599a; 639a). The first black was hired into a non-Labor Department

job in 1962 and the first white was hired into a Labor Department

job in 1965. (514a; 515a; 540a); 549a). The defendant Company did

not place more than six whites into the Labor Department until 1971.

(514a).

This policy of placing blacks into the Labor Department

and whites into the other departments has continued. Of the 109

blacks employed from 1957 through December 10, 1971, 53 were initially

placed in the Labor Department whereas of the 274 whites hired during

the same period only 19 were assigned to the Labor Department. (84r9«;

832*) . In 1971 the defendant Company instituted a policy of

- 6 -

placing all new employees in the Labor Department. (92a).

From 1965 through 1̂ 7|>, 42% or (5̂ ) of all the new black

employees were assigned to Labor, whereas for the same six year

period only 19 or 4% of all the new white employees were placed in

Labor. (817a-818a; 821a-822a). The following chart illustrates

that from the period 1965 through 1970, 35 or 84% of the new

employees hired into the Labor Department were black:

Employees Hired Into Labor Initially

Year 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 Total %

Whites 0 .0 0, 1 4 1 6 16

Blacks 9 2 5 4 & 9 35 84

(819a; 822a)

Mr. F.L. Vanosdall, personnel manager for the defendant

Company, testified that prior to April 1971, new employees were

assigned to departments in the following percentages:

Production ................... 75%

Shipping and Traffic ......... 10%

Laboratory ................... 8%

Labor ........................ 5%

Receiving and Stores ......... 1 - 5 %

Oiler ........................ less than 3%

Utilities .................... less than 1% (89a-91a)

This chart indicates that prior to April 1971 only 5% of all new

employees were initially placed in Labor, but as illustrated above

over 40% of the new black employees were assigned to the Labor

Department.

7

Black people constitute 24% of the total Houston Labor

Force (402a) and from 1966 through 1970 blacks constituted res

pectively 8%, 11%, 12%, 14%, and 13% of the defendants' total work

force. (817a-819a; 821a-841a).

At all times relevant to this lawsuit the defendant Company

has been a government contractor subject to Executive Order 11246

which mandates an affirmative action program to recruit minorities.

Nevertheless, the defendant Company never contacted an agency

designed to refer minority applicants until it contacted the Urban

League in July, 1971. (511a; 494a-495a).

The District Court found that the defendant Company dis

criminated in hiring prior to 1965 but found that it did not dis

criminate in hiring after July 2, 1965. (58a; 60a-61a). The Court

made this finding in total disregard of testimony from Mr. Vanosdall,

that it was the Company's practice not to employ whites in the Labor

Department until September 7, 1965.(539a).

2. Educational and Testing Requirements

The District Court found that in 1957 the defendant imposed

a high school degree requirement as a prerequisite to initial

employment or transfer into all non-Labor Department positions.

(61a). The Court also found that this educational requirement

has never been validated according to the requirements of the EEOC

8

guidelines set forth in 29 C.P.R. §§1607.3-1607.14. (Ibid.)

This high school degree requirement remained in effect

until April 22, 1971, when it was deleted at the insistence of the

Atomic Energy Commission and the Office of Federal Contract Compliance.

(92a; 444a). On two earlier occasions, the requirement was relaxed

at the insistence of the AEC and OFCC. (106a). First, in 1968 all

employees hired in the Labor Department prior to 1957 were given the

opportunity to transfer to other departments if they had a seventh

grade education and could pass the defendant Company's discrimina

tory tests. (48a). The Court found that this was a useless gesture

since no minority group employee could pass the tests. (Ibid.) Then

in 1969 the defendant Company dropped the testing requirement for

employees hired prior to 1957. (48a-49a). Finally, in 1971

following the repeated demands of the OFCC and AEC that the de

fendant change its discriminatory educational and testing policies,

the Company abolished the educational and testing requirements,

and permitted labor department employees hired prior to September

7, 1965, to transfer and retain their Labor Department seniority.

(49a) .

3/ These requirements of course were adopted as the legalstandards in this Circuit in United States v. Georgia Power,

___F.2d____, (No. 71-3447, Feb. 14, 1973); United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1972),

cert, denied 4 EPD f7774, and therefore the non-validation

of this requirement means ipso facto that the requirement

was unlawful, in light of the requirement’s disproportionate

impact on blacks.

3/

9

The adverse impact of the defendant Company's educational

requirements is clearly illustrated by a comparison of educational

attainments of black and white Texas residents. In 1960 the median

number of years of school completed by whites, 14 years of age or

over, was 10.7 years and for non-whites, 8.7 years. (757a-759a).

And in 1966, 49% of the black males in Texas between the ages of

25 to 29 years old had completed 4 years of high school as compared

with 73% of the whites (760a-761a).

Trial testimony indicated that not only did the educational

requirements have a disproportionate impact on blacks, but also

those requirements were applied unevenly and irregularly. (243a;

249a-250a; 366a-367a; 394a-395a). The District Court found that

the educational requirement precluded black employees from ever

attaining the equivalent seniority status and commensurate employ

ment advantages that white employees who were hired at the same

time could attain. (60a). Accordingly, the court permanently

enjoined the use of educational requirements as a condition of ;

transfer to non-labor jobs. (66a-67a).

Along with the requirement of a high school degree, the

District Court found that in 1957 the defendant Company adopted

the requirement of achieving satisfactory test scores.(47a). This

requirement applied to any applicant for employment to any non

labor (i.e. white) department and to any employee seeking a transfer

to any non-labor department. (Ibid.) The defendant Company

stipulated in a pre-trial order, and the District Court also found,

- 10 -

that this testing requirement has never been validated within the

terms of the EEOC guidelines. (60a; 522a). One of the principal

tests employed by the defendant Company was the Wonderlic personnel

test, which as will be discussed infra (p.15),is patently dis

criminatory against blacks. As with the educational requirement,

the District Court found that the testing requirement was applied

to pre-1957 Black Labor Department employees seeking to transfer,

but has never been applied to white employees hired prior to 1957.

(60a).

The adverse impact of the defendant Company's discrimina

tory tests is vividly illustrated by the comparative failure rates

of blacks and whites. 52% (132 of 274) of the blacks failed the

tests but only 15% (126 of the 848) whites failed. (807a-816a).

Moreover, whereas only 25% of the whites not hired during this

period were rejected for failing the test requirements, 62% of the

blacks not hired were rejected for failing the tests. (Ibid.) As

with the educational requirement, testimony at trial indicated that

the test requirements were applied irregularly to the detriment of

black applicants and employees. (534a-536a).

The District Court found that the effect of the defendant

Company's use of these discriminatory testing and educational re

quirements was to lock into the Labor Department those black

employees who were segregated initially into that department as

a result of the defendant Company's racially discriminatory hiring

practices. (60a) .

11

3. Seniority and Transfer.

The defendant Company employed a divisional seniority

system at its Houston Plant. Mr. F.L. Vanosdall, the defendant

Company's personnel manager testified at the trial that the

employees' seniority within a division determines promotions,

layoffs, rate of pay, and vacation time. (96a). Mr. Vanosdall

also testified that prior to the July 24, 1970 Labor Agreement

there was no contract provision to encourage Labour Department

employees to transfer to a more skilled, better paying job in

another department. (97a) .

The District Court found that the transfer system employed

by the defendant Company and acquiesced in by the defendant Local

347 had the effect of locking into the Labor Department the black

employees initially segregated on a racially discriminatory basis,

and that to transfer to a non-Labor Department job, a black employee

had to forfeit his previously earned seniority rights in the Labor

Department. (62a). The Court also found that the defendant Company

offered no proof of a substantial business necessity for this system.

(Ibid.) As a result of this discriminatory seniority system, white

applicants hired in non-Labor Department positions at the same time

black applicants were segregated into the Labor Department maintained

a distinct advantage over fellow black employees, an advantage

predicated solely on past racial discrimination.

The District Court fashioned a decree granting remedial

seniority to all Labor Department employees hired prior to

12

September 7, 1965. The decree gives these employees plant wide

seniority equivalent to their Labor Department seniority through

their first transfer, but only through their first transfer (64a-67a).

It is clear that the defendant Company's seniority system

had a deterrent effect on the plaintiff and the class he represents,

as evidenced by the District Court's holding and also by the fact

that the first member of the "affected class" (pre-1957 Labor

Department employees) to transfer out of the Labor Department did

so on July 21, 1969 (529a-530a).

The cost of defendant's discriminatory seniority and

transfer system to black employees was considerable. As the

District Court found, the jobs in the Labor Department are the

least skilled and lowest paying jobs in the defendant Company’s

plant. (48a). Black employees, the majority of whom are employed

in the Labor Department, earn an average of $700 less than white

employees (805a-806a). The earning disparity between blacks hired

prior to 1957 and whites hired prior to 1957 is even greater; and

as the District Court found, white employees who were hired at

about the same time as Plaintiff and the class of black employees

he represents have earned more money since the effective date of

Title VII simply because the whites were placed inititally in the

departments containing the higher paying jobs. (60a).

C. Plaintiffs Individual Claim

Plaintiff R.L. Johnson, a black employee of the defendant

13

Company seeks on behalf of himself and other black employees

similarly situated injunctive relief and back pay as a result

of the discriminatory employment practices of the defendant

Company and Local 347. (44a). Plaintiff's claim is that as a

consequence of the employment practices and collective bargaining

agreement entered into by the defendants, black employees have

been in the past and continue to be segregated by assignment to

the Labor Department. (Ibid.) As a lifelong employee in the

Labor Department, he fully typifies this claim. Finally, plaintiff

contends that the defendant Company's testing and high school educa

tional requirements as well as the seniority provision in the appli

cable collective bargaining agreement serve to perpetuate this

hiring discrimination. (Ibid.)

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING

THAT THE DEFENDANT COMPANY'S TESTING

REQUIREMENTS DID NOT DISCRIMINATE

AGAINST BLACK EMPLOYEES HIRED AFTER 1957

A. Plaintiff's Statistical Evidence Overwhelmingly

Indicates That The Defendant Company's Testing Re

quirement Had A Severely Disproportionate Impact On

Blacks Hired After 1957.

The District Court found that plaintiff's evidence failed

to indicate that the testing requirement disqualified black employees

hired after 1957 at a substantially higher rate than whites. (60a).

14

This finding is plainly incorrect. The only data available on

the defendant Company's tests shows that from January 1, 1969,

through October 30, 1971 of the 274 blacks taking the tests,

132(49%) failed; whereas during this same period of the 848 whites

taking the tests only 126 (15%) failed. (807a-816a). This showing

of discriminatory impact is supported by the fact that whites

failing the test constituted 25% of the whites rejected for em

ployment, whereas blacks failing the test constituted 62% of the

blacks rejected for employment. (805a-816a).

One of the principal tests employed by the defendant was

the Wonderlie test, a test that has been found to be patently dis

criminatory against blacks. (See Griggs v. Duke Power Company,

401 U.S. 424 (1971); Moody v. Albermarle Paper Company, ___F.2d___

(4th Cir. No. 72-1267, Feb. 20, 1973)).

It is critical to note at this juncture that, as the

District Court found, in the Defendant Company's plant a success

ful score on the tests was an abosolute prerequisite to entry into

the formerly white lines of progression. (47a). This require

ment was instituted in 1957 and until 1969 any black employee who

sought to transfer out of Labor or sought initial employment in a

non-Labor Division had to pass these tests. (47a-49a).

The District Court found that the Defendant Company's

"first offer" to the members of the "affected class" (pre-1957

Labor Department hirees), allowing them to transfer to other

15

departments if they had a seventh grade education and passed the

tests, produced no affirmative results since no member of the

"affected class" could pass the tests. (48a). The District Court

further found that the "second offer" in 1969 that allowed the same

group to transfer without taking the tests attained little success

since the transferring employee would have forfeited his Labor

Department seniority. (49a). Not until April 22, 1971 after

repeated demands by the OFCC and the AEC did the defendant Company

abolish its discriminatory educational and testing requirements

and allow members of the "affected class" to transfer and retain1/their Labor Department seniority. (Ibid.)

B. Since the Defendant Company's Testing Require

ments Were Not Validated, The District Court Erred

In Finding That These Requirements Did Not Discri

minate Against Blacks Hired After 1957.

There was no evidence adduced at the trial that the tests

were job related and the District Court ;found as a matter of law

that the defendant Company did not show a legitimate business

necessity for the tests. (51a). The Court also found that testing

requirements were never validated. (61a). Notwithstanding its own

findings the District Court concluded that the defendant Company's

testing requirements did not discriminate against blacks hired

4/ It should be reiterated at this point that the District Court

found that on three different occasions the Office of Federal

Contract Compliance required the defendant Company to relax

its testing requirements. (48a). Defendant's three "offers'

were therefore anything but voluntary.

16

after 1957. We submit that contrary to the ruling of the District

Court, facts like these enumerated in part I.A of this brief and

the lack of proper validation of the tests, proves conclusively

that the tests were unlawful as to blacks hired prior to and after

1957 and the District Court should have so held. Griggs v. Duke

Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971); United States v. Georgia Power

Company, ____F.2d____(5th Cir. No.71-3447, Feb. 14, 1973) ; Moody

v. Albermarle Paper Company,____F.2d____(4th Cir. No.72-1267,

Feb. 20, 1973); United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451

F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 4 EPD f7774.

C. The District Court Applied Improper Standards

Of Law In Reaching Its Erroneous Conclusion.

The District Court's analysis of the evidence relating to

the tests ignores the applicable principles of law.

The District Court concluded that the defendant Company's

tests did not discriminate against blacks hired after 1957 because

132 blacks failed the tests compared to 126 whites - a difference

of less than 6% (51a; 69a). This methodology is totally inapposite

and does not take into account the fact that the rate of failure

for blacks was approximately 50% (132 of 274) compared to a less

than 15% failure rate for whites (126 of 848). These grossly

disproportinate failure rates clearly indicate that the District

Court applied an erroneous standard of law in interpreting plain

tiff's data.

17

The District Court also applied an erroneous standard of

law in holding that the defendant Company's testing requirement

did not disqualify blacks at a "substantially" higher rate than

whites. (51a; 61a). Plaintiff's data certainly shows a large

statistical variance between white and black failure rates. More

over, neither Title VII nor the EEOC guidelines use or employ the*

term "substantial” in defining employment discrimination. The

EEOC guidelines state in pertinent part:

. . . the use of any test which adversely affects

hiring, promotion, transfer or any other employment

or membership opportunity of classes protected by

Title VII constitutes discrimination unless the

test is validated and evidences a high degree of utility.

29 C.P.R. §1607.3

To attach a requirement of "substantiality" to prove dis

crimination would allow employers to discriminate with impunity.

As Chief Judge Brown, writing for a unanimous Court, stated in

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972):

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act prohibits all

forms of racial discrimination in all aspects of

employment. Local 189, United Paper-makers and Paperworkers, A .F.L.-C.1.0.,C,L.C . v. United States

5th Cir. 196$, 416 F.2d $80, 982, cert. denied,1$70

397 U.S. 919, 90 S.Ct. 926, 25 L.Ed.2 100. The

degree of discrimination practiced by an employer

is unimportant under Title VII. Discrimination

comes in all sizes and all such discriminations are prohibited by the Act (457 F. 2 at 354) .

Thus, it is clear that the District Court's analysis of the testing

data was improper and ignores the applicable principles of law.

18

D. This Court Should Direct The Entry Of

Appropriate Relief From The Effects Of The

Defendant Company's Unlawful Testing and

Educational Requirements.

Plaintiff urges this Court to issue a declaratory judgment

that the defendant Company’s testing requirements discriminated

vagainst all black employees, including those hired after 1957.

This Court should require the defendant Company to submit an

annual report to the Court to assure defendant's continued com

pliance. Plaintiffs are not seeking an injunction in this case

solely because these discriminatory tests have been discontinued

for over two years at the insistence of the OFCC and AEC, and

these agencies are not likely to allow these tests to be resumed.

This Court should also provide affirmative relief for

members of the class from the continuing effects of the defendant

Company's unlawful testing and educational requirements. The

District Court enjoined the use of the testing requirements only

as to blacks hired in the Labor Department prior to 1957, (67a).

This order would deny plaintiffs the full and adequate relief to

which they are entitled. Plaintiffs and members of the class are

suffering continuing injury due to the defendant Company's testing

and educational requirements. The use of these unlawful screening

5/ There is no necessity to remand for a determination of

validity, cf. United States v. Georgia Power, supra? since as

set forth above the District Court found that the defendant

Company did not attempt to show or contend that the tests were

valid (51a).

-19-

devices has precluded or retarded their advancement from the menial,

traditionally black laboring-type jobs to the better and higher

paying jobs held almost exclusively by whites. This Court should

redress the District Court’s error in failing totally to provide

relief from these continuing effects of past discrimination.

This Court recently adopted plaintiffs' position in its

thoughtful decision in United States v. Georgia Power Company. 3Upra,

where it noted with approval the District Court's extension of

affirmative seniority relief to victims of a discriminatory high

school education requirement. (Slip Op. at 43-44). At the same

time, m reversing the district court’s finding of no testing dis

crimination, this Court held that, unless the tests could be shown

lawful, test-discriminatees would also be entitled to affirmative

relief, according to the "rightful place" theory (Id.). in that

case the restriction of black employees to jobs of laborer, porter,

janitor, or maid by testing and educational requirements is analagous

to the class members' restriction to Labor Department jobs in this

case. Thus, here as in Georgia Power.

Should company test invalidity be the trial

court's ultimate conclusion, the seniority would thereby be extended to all blacks wrongfully de

prived of the opportunity to advance beyond the

[predominantly back] positions by either the

testing or the educational requirements. (Slip Op. at 45). [Emphasis added]

Since this Court must on these facts, under established law

render the "ultimate conclusion" that the defendant's testing was

unlawful, this case now stands for entry of appropriate affirmative

20

relief "to eliminate the present effects of past discrimination"

to the extent possible, Local 53, Int'l Ass'n of Heat & Frost

Insulators and Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2 1047, 1052-1053

(5th Cir. 1969). Since all victims must have their seniority

remedy, the District Court's seniority relief must be extended

to post-1965 hirees whose assignment or advancement to non-Labor

Department jobs was precluded or retarded by the unlawful require

ments. Such relief should include an affirmative provision for

training and advancement as well as class-wide back pay (see part

III, infra), for discrimatees whenever hired.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FINDING THAT THE DEFENDANT COMPANY'S DIS

CRIMINATORY HIRING PRACTICES DID

NOT EXTEND BEYOND JULY 2, 1965.

A. The District Court Erred in Finding That

The Plaintiff's Statistics Did Not Make Out A

Prima Facie Case Of Hiring DiscriminationSubsequent To July 2, 1965.

The Court below found as an "undisputed fact" that black

employees were segregated into the Labor Department until July 14,

1962 and that white employees were channeled away from the Labor

Department until September 7, 1965. (48a). The Court further

found that the positions in the Labor Department were composed of

the least skilled and lowest paid positions in the plant. (Ibid.)

The defendant Company maintained, and the District Court

agreed, that with the hiring of a few blacks into non-Labor posi

tions in 1962 and the hiring of one white into the Labor Department

21

in 1965, discrimination ended. (47a-48a). The District Court's

conclusion that the defendant Company's hiring discrimination

ended suddenly on July 1, 1965 (the effective date of Title VII)

is at best anomalous in light of the fact that no white was ever

employed in the Labor Department until September 7, 1965.(51a).

A cursory look at plaintiff's statistical data demonstrates

unequivocally that the District Court erred. (734a; 817a-818a; 821a

822a). Excluding the year 1971 (in which all new employees were

placed in the Labor Department), from 1965 through 1970, 35 of 80

(43%) new black employees were assigned to the Labor Department

compared to 6 of 149 (4%) new white employees assigned to the

Labor Department during the same period. (Ibid.)

The following chart illustrates that the defendant Company's

discriminatory hiring practices continued unabated in the two years

after July 2, 1965;

No. & % of New Total No. & % of New

Black Employees New White Employees

Total New Black Assigned White Assigned

Year Employees to Labor Employees to Labor

1965 13 9(69%) 17 1/(^6%)

1966-67 22 7 (32%) 28 0 (0%T

(Ibid.)

This chart clearly illustrates that while the defendant Company

might have been hiring more black employees, the same old discri

mination ruled: blacks went to the lowest paying jobs in the plant

and whites to the higher paying jobs. The chart also indicates

22

that subsequent to the time when the District Court found hiring

discrimination had ended, the defendant Company assigned 46% (16 of 35)

of the new black employees to Labor whereas only 2.2% (1 of 45)

of the new white employees were assigned to Labor.

Moreover, the defendant Company's discriminatory hiring

practices did not cease in 19 fef. The following chart shows that

the defendant Company continued in the following three years to

assign blacks to the lowest paying jobs where they were locked

in as a consequence of the defendant company's discriminatory

educational and testing requirements:

Year

Total New Black

Employees

No.& % of New Black Employees Total New

Assigned White

To Labor Employees

No. & % of New White Employees

Assigned

To Labor

1968 14 4 (28%) 25 1 (4%)

1969 14 6 (42%) 48 4 (8%)

1970 17 9 (52%) 31 1 (3%)

(Ibid.)

The fact that the defendant Company continued its dis

criminatory hiring practices well beyond July 2, 1965, by placing

blacks only in Labor and placing whites in non-Labor jobs is most

clearly shown when focusing on black employees as a percentage of

Labor Department employees from September 7, 1965, through 1970:

23

% of Blacks In LaborYear Departme;

9/7/65 100.0

1966 96.5

1967 97.0

1968 94.5

1969 87.0

1970 88.0

(Ibid.) This chart shows that from total segregation in 1965,

the Department had only moved by 1970 to token integration.

The data set forth above establish a strong presumption

that the defendant Company continued its hiring discrimination

beyond July 2, 1965. Plaintiffs, however, are not contending

that the defendant Company should cease hiring blacks into the

Labor Department, but rather that the defendant Company should

begin to assign a substantial number of blacks to the higher

paying non-Labor jobs.

Notwithstanding this data, the District Court found as a

matter of law that the "plaintiff has failed to make out a prima

facie case, since for all practical purposes there is not significant

or persuasive evidence that the discriminatory hiring practice ex

tended beyond July 2, 1965."(48a). This ruling was clearly in

correct in that the District Court improperly analyzed plaintiff's

data and failed to apply the proper standards of law as enunciated

by this Court.

24

This Court has long held that statistical evidence can

be used to substantiate claims of racial discrimination. Most

recently, this Court stated, in language fully applicable to

the case at bar:

These lopsided ratios are not conclusive proof

of past or present discriminatory practices;

however, they do present a prima facie case.

The onus of going forward with the evidence and

the burden of persuasion is thus on [the employer]. . .

. . . the inference arises from the statistics

themselves and no other evidence is required to

support the inference.

United States v. Hayes International Corp. 456 F.2

112, 120 (5th Cir. 1972. Cf. Bing v. Roadway

Express. Inc. 444 F.2 687, 689 (5th Cir. 1971);United States v. Georgia Power Company, supra.

This Court has also held that "there can be no reasonable justi

fication for the absence of blacks from all but the most menial

caraft and class seniority rosters." United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co.. supra, at 449. Accord: United States v. Dillon

Supply Co.. 429 F.2d 800 (4th Cir. 1970)

The statistics in this case clearly established that

plaintiff and the class he represents were continuously and dis

proportionately assigned to the lowest paying jobs in the plant

and in failing to find that the plaintiffs had made out a prima facie

case the District Court erred as a matter of law.

25

B. The District Court Erred In Finding That

The Defendant Company's Statistics Constituted

A Defense To Plaintiff's Claim Of Discrimination

In Hiring Beyond July 2, 1965.

The defendant Company presented evidence to the District

Court "that from January 1, 1962 to December 12, 1971, over 32

percent of all employees transferred or hired into non-Labor

department jobs have been black employees." (57a). Relying on

this data the District Court found as a matter of law that such

evidence "convincingly rebutted the statistical evidence" presented

by the plaintiff. (58a). As outlined in part 11(A), supra, the

District Court erred in failing to accord plaintiffs' statistics

their proper weight. The District Court was also confused with

respect to the factual record and as a result it committed errors

of law.

The District Court specifically relied on the defendant

Company's transfer data for 1962, 1963 and 1964 in concluding that

6/there was no hiring discrimination after 1965. (1094a). In the

years 1962 through 1964 the defendant Company hired 24 new employees,

9 of whom were black, constituting 37.4% of total new employees.

(803a-806a). To include these figures as the District Court did

in deciding the issue of discrimination post-1964 not only camouflages

the defendant Company's real figures but also inflates the post-1964

6/ It could not have been relying on the defendant Company's

hiring data for Blacks into non-Libor jobs because as the

District Court found prior to 19p5yno Black was ever hired

into a non-Labor job. (48a) . vsf

Va.

- 26 -

figures. This type of misinterpretation of data would allow the

defendant Company to discriminate with impunity in 1965-1970 and

then by aggregating all of the figures from 1962 through 1970

appear to be engaging in practices of equal employment opportunity.

This type of methodology employed by the District Court

is totally unacceptable in Title VII suits. As shown in part

11(A) of this brief the evidence is overwhelming that the defendant

Company discriminated in the hiring and placement of blacks from

1965 through 1970. To aggregate the figures as the District Court

has done would mean that if no blacks were hired from 1965 through

1970, and in 1971 as trial approached a defendant hired 100 blacks

a court could conclude by averaging this figure that there had

been no discrimination in hiring from 1965 through 1970. More

over such an error of aggregation is exacerbated if, as the

District Court concluded, that because of what a defendant did

in 1962, 1963, 1964 or 1971, there was necessarily no discrimina

tion in any particular intervening year. Plaintiff maintains

that if the District Court had properly analyzed the annual figures

from 1965 through 1970 it would have been compelled to conclude

that the defendant Company has consistently maintained its policy

of placing only blacks in Labor and only whites in non-Labor

positions. Cf. United States v. Hayes International Corp., supra;

27

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2 1377 (4th Cir.

1971), cert, denied 41 U.S. Law Week 3253 (1972); Parham v.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433, F.2d 421, 426 (8th Cir.

1970); Jones v. Lee Way Motor Freight Co., 431 F.2d 245, 247

(10th Cir. 1970), cert, denied 401 U.S. 954 (1971).

One of numerous examples will illustrate that the plaintiffs

in this case were continually disadvantaged by the defendant Com

pany's discriminatory hiring practices far beyond July 2, 1965.

Mr. N. Bean was hired into the Labor Department under admittedly

discriminatory placement and was subsequently locked into that

department by the defendant Company's institution of degree and

testing requirements. Nevertheless, since Mr. Bean transferred

out of Labor in 1970 the defendant Company has attempted to use

this figure to show that it did not discriminate in hiring after

July 2, 1965. The District Court's faulty logic accepts the

Company's contention.

C. The District Court Erred In Finding

That The Defendant Company Had Not Dis

criminated In Hiring Subsequent To July 2,

1965, In Light Of Its Own Findings That

The Defendant Company Maintained Until

April 22, 1971, Unvalidated Educational

And Testing Requirements That Excluded Blacks.

Until April 22, 1971, the defendant Company required a

28

high school degree or its equivalent and satisfactory test scores

as prerequisites to employment in non-Labor Department positions.

The District Court found as a matter of law that the defendant

Company's educational requirement "disqualifies black applicants

at a substantially higher rate than white applicants." (61a).

Thus, the District Court found the educational standard unlawful;

and as we have argued in parts 1(A) & (B) of this brief the

defendant Company's testing requirements is also unlawful. The

Court found that these requirements were never validated within

the guidelines of the EEOC and that the defendant Company had not

shown any business necessity for the maintenance of the requirement.

(61a-62a).

It is crystal clear that a non-validated requirement that

is not job-related and that has a disproportionate impact on blacks

is a violation of Title VII. Griggs v. Duke Power Company, supra;

United States v. Georgia Power Company, supra; slip op. p.21.

Thus, confining itself solely to the findings enumerated

above, the District Court was compelled to hold, as a matter of

law, that the defendant Company had discriminated in hiring beyond

July 2, 1965. Its failure to reach this conclusion was error.

29

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO AWARD CLASS-WIDE BACK PAY.

A. Since The District Court Found That

Members Of The Class Suffered And Are Continuously Suffering An Economic Loss As A

Result Of The Defendant Company's Discrimi

natory Employment Practices It Erred In Fail

ing To Award Classwide Back Pay.

As a direct consequence of the defendant's discriminatory

employment practices, set forth in parts I and II of this brief

plaintiff and members of the class he represents have suffered

acute economic losses. This is most dramatically illustrated

by the fact that the present average annual pay difference between

white and black employees is $748.80 (805a - 806a).

Plaintiff R.L. Johnson sought in his prayer for relief

back pay for himself and other black employees similarly situated.

(27a - 33a). This issue was squarely presented to the Court

below. (44a). However, the District Court apparently viewed an

award of back pay as purely discretionary, (69a) and therefore

without any discussion limited back pay to the named plaintiff.

(67a - 68a). The District Court failed to award back pay to

all class members notwithstanding its own finding that twenty-six

class members hired from 1943 to 1965 suffered economic loss due

to the defendant Company's discriminatory employment practices

(47a - 48a), and notwithstanding its finding that from 1943 to

30

to 1962 blacks wee e hired only in the Labor Department which

was composed of the lowest paid positions in the plant. (48a).

This Court has long held that the award of back pay in Title VII

suits is not solely a matter of a district court's discretion but

rather "is an inextricable part of the restoration to prior status."

Harkless v. Sweeny, 427 F.2d 319, 324 (5th Cir. 1971); cf. United

States v. Georgia Power, supra, where this Court said:

Back pay is viewed as an integral part

of the whole of relief which seeks not

to punish the respondent but to compensate

the victims of discrimination. Slip Opinion at 30.2/ Accord: Moody v.Albermarle

Paper Company, supra.

The District Court found that the defendant Company discrimi

nated up to July 2, 1965 (58a). Confining ourselves solely to the

District Court's findings and reasoning, the 10 persons hired from

1957 through 1965 were discriminatorily assigned to the Labor

Department. (803a) and as a result of the defendant Company's post

- 1965 discrimination, to wit: educational and testing requirements

and divisional seniority system, these employees have been locked

in the lowest paying least skilled jobs in the plant. Moreover,

these same employees have labored under a disincentive to tramsfer

since a transfer would have required them to forfeit their seniority.

7/ In Georgia Power, this Court held that on award of classwide

back pay is proper in a pattern or practice suit brought by the

Attorney General pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §2000e-6 (a) even though this section does not explicitly provide for back pay. A Fortiori, an

award of back pay to the class is proper in am action brought by

private plaintiffs, pursuamt to 42 U.S.C. §2000e - 5(g), which

expressly privides for back pay.

31

(61a).

Therefore, for all of the reasons given in part III A. of

this brief this subclass of plaintiffs is entitled to the remedy

of back pay.

As clearly demonstrated in parts I, II, and IIIA. of this

brief the defendant Company's discriminatory practices continued

unabated after 1965 by its assignment of blacks into the Labor

Department (48a); by imposing discriminatory, nonvalidated

tests and educational requirements as prerequisites into the

white lines of progression (47a) and by maintaining a discrimina

tory seniority policy that "locked in" blacks (48a).

Accordingly this subclass of plaintiffs, 26 black employees,

is also entitled to back pay for the economic losses they have

suffered due to the defendant Company's discriminatory employ

ment practices.

B. The District Court Did Not Enunciate

Any Reason Why It Awarded The Named

Plaintiff Back Pay, And Refused To

Award Back Pay To Fourteen Other Black

Labor Department Employees Hired Prior

To 1957.

The named plaintiff, R.L. Johnson, and 14 other blacks

were all hired into the Labor Department prior to 1957 (801a).

Therefore, for the purposes of this class all 15 employees were

identically situated. They were hired into what was intention

ally and admittedly a segregated department (48a). They ware

32

then "locked in" this department by the defendant Company's

discriminatory testing and educational requirements (60a).

They were all equally the victims of the defendant Company's

discriminatory seniority system that deterred transfer even if

they could satisfy the testing and educational requirements

(62a). Finally, as a direct result of the defendant Company's

discriminatory practices all 15 of these employees have been at

a continuous wage disadvantage to white employees (805a-806a).

This Court has long held that Courts have:

"the duty and ample powers both in the

conduct of the trial and the relief

granted to treat common things in

common . . . "

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 35 (5th Cir. 1968).

The District Court clearly failed to treat common things in

common or to state why it was treating identical situations

differently. Finally, the District Court gave absolutely no

reason to justify its denial of back pay.

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN LIMITING

THE PERIOD FOR WHICH THE NAMED PLAINTIFF'S

BACK PAY CAN BE AWARDED TO NINETY DAYS

PRIOR TO THE FILING OF THE EEOC CHARGE

The District Court limited plaintiff's recovery of back

wages to the ninety days period prior to the filing of the EEOC

charge until the date of judgment, February 4, 1967 to November

10,1972 (68a-69a).

33

Plaintiff submits that the District Court committed

two errors in computing back pay: (1) it incorrectly applied

the applicable statute of limitations for plaintiff's §1981

cause of action; (2) it erroneously applied 42 U.S.C. §2000e

- 5 (d) , a statute on limitations on filing as a statute of

limitations on relief.

A. The Statute of Limitations for

Plaintiff's § 1981 action.

The statute of limitations on a §1981 cause of action

is the most closely analogous state statute of limitations.

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co., 437 F.2d 1011

(5th Cir. 1971); United States v. Georgia Power, supra. It

is settled law that the filing of a charge with the EEOC tolls

the statute of limitations for the purposes of §1981.

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co., supra n.16;

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Company, 421 F.2d 888, (5th Cir.1970)

The District Court found that in this case the most closely

analogous state statute is §5529 of the Tex Rev. Civ. Stat. Annot.,

with a limitations period of four years. Therefore under the

1866 Civil Rights Act plaintiff is entitled to back pay measured

from four years prior to the filing of their EEOC charge.

Accordingly for §1981 the proper period of computing back pay

is May 4, 1963 until the date of entry of judgment, November 10,

1972. Compare Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Co., supra, where

back pay was allowed as far back as 1960.

34

B. The 90 Day Filing Requirement of

42 U.S.C. §2000e - 5(d) Is Not A Limit

ation On The Appropriate Relief.

In United States v. Georgia Power, supra, the defendant

attempted to argue that back pay should be limited to the ninety

day period prior to the filing of the EEOC charge through the

date of judgment. This Court in no uncertain terms dismissed

the argument, stating that 42 U.S.C. 2000e - 5(d) "is in no

sense a limitation on the period for which one may receive back

pay relief." United States v. Georgia Power, Slip op. p.33.

This Court went on to say that the "remedial purposes of the

Act would be frustrated were financial redress to be always

limited to the 90-day period preceding the filing of a complaint."

(Ibid).

This Court then declared that the applicable state

statute of limitations would govern the computation of class

back pay. United States v. Georgia Power, slip op. p. 35.

The lower court, as previously noted, determined this to be

the four-year Statute of limitations under §5529 of Tex. Rev.

Civ. Stat. Annot; and plaintiff does not dispute that

determination. Accordingly the computation period for back

pay in this case is from May 4, 1963 through November 10, 1972.

Moreover, plaintiff submits that even under the 1972 Amendment

to Title VII (Section 706(g)) that establishes a two year

limitation on relief, plaintiff would be entitled to recover

back pay from July 2, 1965.

35

CONCLUSION

We respectfully urge this Court to hold that the decision

below was in error in each of the respects set forth herein, and

in reversing to enter am appropriate order correcting each of the

District Court's enumerated errors. This Court's Order should

hold that : (1) the defendamt Company's testing requirement dis

criminated against all black employees including those hired after

1957; and (2) the defendant Compamy discriminated in hiring in

each and every year until April 22, 1971; (3) plaintiff and

members of the class he represents are entitled to back pay to

compensate them for the losses they have suffered as a result of

the defendant Company's discriminatory employment practices.

This Court should also remand with instructions to enter

a decree providing full and effective relief for such discrimination.

Such relief should specifically include (1) an order requiring the

defendant Company to submit an annual Report to the Court to assure

the defendant continued compliance; (2) the extension of plant

wide seniority to all members of the class wrongfully deprived of

the opportunity to advance beyond the Labor Department by either

the defendant Company's discriminatory testing or educational

requirements; (3) a provision for training and advancement, for all

members of the class wrongfully deprived of the opportunity to

advance beyond the Labor department by either the defendant

Company's discriminatory testing or educational requirements;

36

(4) an award of back pay to all class members; (5) an

award of back pay to the plaintiff from May 4, 1963, to

November 10, 1972; (6) an award of counsel fees to

plaintiffs.

This Court should further instruct the District

Court to hold further proceedings to determine the amounts

and distribution of back pay.

Respectfully submitted,

C [y ______JACK GREENBERG WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

C. VERNON MASON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

GABRIELLE K. MCDONALD

MARK T. MCDONALD

1834 Southmore Blvd.

Suite 203

Houston, Texas 77004

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appe Hants.

37

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

R.L. Johnson, et al., hereby certifies that on the 30th day of

April, 1973, he served copies of the foregoing brief for

Plaintiffs-Appellants upon counsel of record for the other

parties as listed below, by placing said copies in the United

States Mail, airmail, postage prepaid:

V.A. Burch, Jr., Esq.

3000 One Shell Plaza

Houston, Texas 77002

William N. Wheat, Esq.

600 Cullen Center Bank BuildingHouston, Texas 77002

/

O'- O' / > tod&r<____________

C. Vernon Mason

Attorney For Plaintif ̂-Appellants

38

#»*

4

5#