Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Nemours Brief for Appellant Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Public Court Documents

May 22, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Nemours Brief for Appellant Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1980. 39e1f6a4-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d659e746-0d13-4a2a-a65c-36828a075314/equal-employment-opportunity-commission-v-nemours-brief-for-appellant-equal-employment-opportunity-commission. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

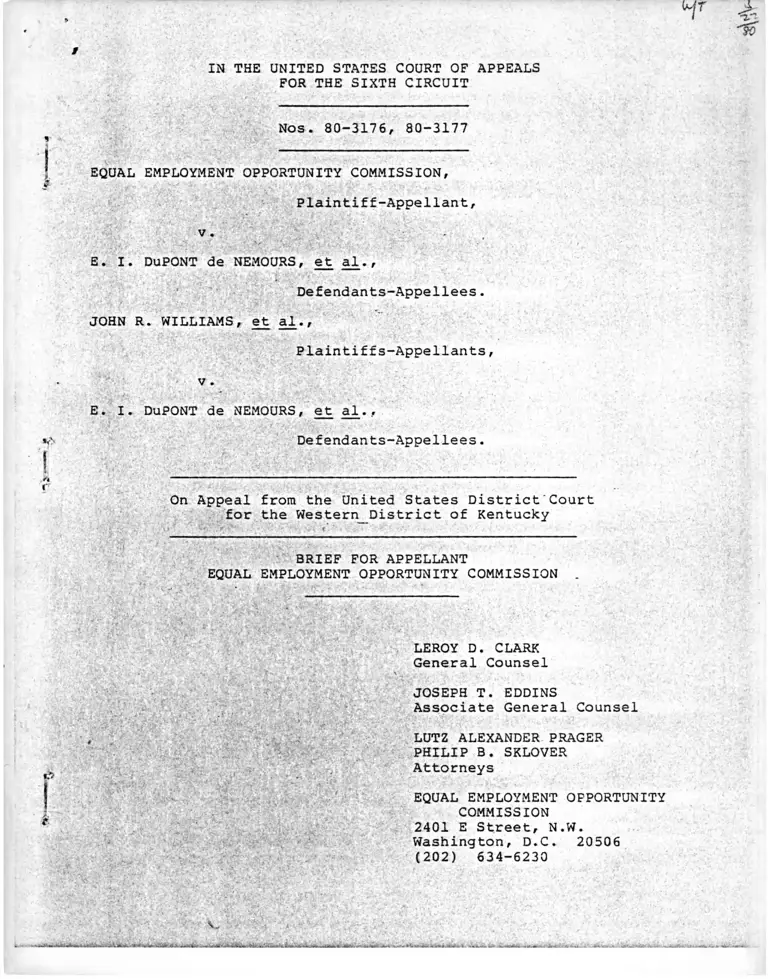

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 80-3176, 80-3177

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v . -

e . i. dupont de Nemo urs, et ai.,

Defendants-Appellees.

JOHN R. WILLIAMS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

e . i. dupont de Nemo urs, et ai.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District'Court

for the Western District of Kentucky

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

LEROY D. CLARK General Counsel

JOSEPH T. EDDINS

Associate General Counsel

LUTZ ALEXANDER PRAGER

PHILIP B. SKLOVER

Attorneys

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

2401 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20506

(202) 634-6230

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ISSUES PRESENTED.................................... 1

STATEMENT........................................... 2

1. Proceedings Below........................ 3

2. Record On Motion For Summary Judgment..... 6

3. The District Court Decision.............. 9

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............. 10

ARGUMENT............................................ 13

I. DEFENDANTS' INTENT IN ADOPTING AND

MAINTAINING THE SENIORITY SYSTEM CANNOT BE RESOLVED ON SUMMARY JUDGMENT

IN THIS CASE........................... 13

II. THE DECISION IN UNITED AIR LINES v.

EVANS, 431 U.S. 553 (1977), DOES

NOT SUPPORT SUMMARY JUDGMENT........... 2 0

III. THE ALLEGATIONS IN THE EEOC COMPLAINT

ARE PROPERLY BEFORE THE COURT.......... 2 2

CONCLUSION.......................................... 24

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Acha v. Beame, 570 F. 2d 57 (2nd Cir. 1978).......... 15, 19, 21

CASES PAGE(S )

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144

(1970) ............................................... 14' 17

Bohn Aluminum & Brass Corp. v . Storm King

Corp., 303 F. 2d 425 (6th Cir. 1962)................. 15

California Brewers Association v .

Bryant, U.S. , 63 L.Ed 2d 55

100 S.Ct. 814 (1980)......... 20

Cedillo v. Ironworkers Local 1, 603 F.2d 7

(7th Cir. 1979)..................................... 16

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal, F.Supp.___, 15 FEP

Cases 822 (N.D.Ind. 1977)............................. 18

Croker v. Boeing Co. Vertol Div., 437 F. Supp.

1138 (E.D.Pa. 1977)................................. 19

EEOC v. Bailey Co., 563 F.2d 439 (6th Cir. 1977).... 10, 12, 23,---- --------- 2 4

EEOC v. General Electric Corp., 532 F.2d 359

(4th Cir. 1976)............. 23

EEOC v. Huttig Sash & Door, 511 F.2d 453

(5th Cir. 1975).................................... 23

EEOC v. Kimberly Clark Corp., 511 F.2d 1352

(6th Cir.), cert. denied, 423 U.S. 994 (1975)....... 11, 23, 24

EEOC v. Local 189, United Association of

Journeymen and Apprentices of Plumbing a~nd

Pipe Fitting Industry, 427 F.2d 1091 (6th Cir.

1970)............................................... 34

EEOC v. Occidental Life Insurance Co., 535

F.2d 533 (9th Cir. 1976), aff'd on other grounds,

432 U.S . 355 (1977)................................. 23

Evans v. Delta Air Lin_es, 551 F. 2d 113

(6th Cir. 1977)..................................... 23

Fisher v. Proctor & Gamble Mfq. Co. ,

613 F.2d 527 (5th Cir. 1980)..................... 13 , 19

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (cont'd)

CASES PAGE(S )

Fitzsimmons v. Best, 528 F.2d 692

(7th Cir . 1976)...................................... 15

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747 (1976)...................................... 11/ 19 , 20

General Tel. Co. v. EEOC, 48 U.S.L.W. 4513

(May 12, 1980)....................................... 11/ 23

Hart v. Johnston, 389 F.2d 239 (6th Cir. 1968)....... 15

Hospital Bldq. Co. v. Rex Hospital Trustees,

425 U.S. 738 (1976).......... ........................ 16

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)................... 9, 10, 11,13, 18, 19

20, 21

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Co.,

559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied

434 U.S. 1034 (1978).............................. 13 , 18 , 19

Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mutual Hospital, 538

F. 2d 164 (7th Cir. ,1976), cert. denied, 429

U.S. 986 (1976)..................................... 23

Morelock v. NCR Corp., 586 F.2d 1096 (6th Cir.

1978)........................ 22

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 586 F.2d 300

(4th Cir. 1978).................................... . . 18, 19, 20

Rogers v. Peabody Coal Co., 342 F.2d 749

(6th Cir. 1965)...................................... 15

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, 431 F.2d 455

(5th Cir. 1970)...................................... 23

Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad

Co. , 454 F. Supp. 158 (D.Kan. 1978)................. 18

S.J. Groves & Sons, Co. v . Ohio Turnpike

Commission, 315 F.2d 235 (6th Cir. 1963), cert.

denied, 375 U.S. 824 (1963).......................... 15

Smith v. Hudson, 600 F.2d 60 (6th Cir. 1979),cert. dismissed, ___ U.S. ___, 100 S.Ct. 495 (1979)... 15

Tipler v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co.,

443 F. 2d 125 (6th Cir. 1971)......................... 23 , 24

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (cont'd)

Toebelman v. Missouri Kansas Pipe Line Co.,

130 F. 2d 1016 (3d Cir. 1942)........................ 16

United Air Lines v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977)...... 2, 9, 10,

-------------------- 11, 20, 21,

22

United States v. Diebold, 369 U.S. 654 (1962)....... 14

STATUTES AND RULE

28 U.S.C. §1291..................................... 2

Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C.

§621, e_t seq........................................ 22

§1, Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981....... 2

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq (1976)...................... passim

§703 (h) , 42 U.S.C. 2G00e-2(h).................... 1, 2, 13

Rule 56, Fed.R.Civ.P................................ 14

OTHER AUTHORITY

Executive Order 11246 (Sept. 24, 1965)............... 9

CASES PAGE(S )

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 80-3176, 80-3177

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v .

e . i. Dupont de Ne m o urs, et ai.,

Defendants-Appellees.

JOHN R. WILLIAMS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

e . i. Dupont de Nemo urs, et. ai.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Kentucky

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY COMMISSION

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether in an employment discrimination suit, the

trial court correctly considered all of the facts of record

when it held, on motion for summary judgment, that the

seniority system was bona fide within the meaning of §703(h)

of Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-2(h)?

2. Whether United Air Lines v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977)

bars the Commission and private plaintiffs from challenging

discriminatory testing practices, established prior to the

effective date of Title VII but still in effect?

3. Whether the trial court erred, as a matter of law and

fact, in dismissing allegations in the government's complaint

pertaining to discriminatory hiring, job assignments, and

testing, on the grounds that they were beyond the scope of the

underlying administrative charges?

STATEMENT

These are consolidated appeals from summary judgment in favor

of E. I. DuPont de Nemours and the Neoprene Craftsmen Union in

consolidated actions, one brought as a private class action under

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., and

§1, Civil Rights Act of 1866, ~42 U.S.C. §1981, and the other brought

under Title VII by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1291.

In granting summary judgment, the district court held that

as a matter of law (1) the seniority provisions of the collective

bargaining agreement were "bona fide" within the meaning of §703(h)

of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h), and thus could produce no un

lawful consequences; (2) Williams' allegation that DuPont uses

unlawful testing procedures was not timely filed with the EEOC;

and (3) the EEOC's allegations of racial discrimination in

hiring, job assignments, and other terms and conditions of

employment, including testing, were unrelated to the allegations

2

in the administrative charges on which the Commission's suit was

1/based. [Memorandum Opinion].

1. Proceedings below

In January 1971, John R. Williams filed a charge of racial

discrimination against DuPont and the union with the EEOC; in

the next six months, seventeen other black employees at the

Louisville plant filed similar charges. [EEOC charge of discri

mination]. The eighteen charges were consolidated by the Commission

for investigation, decision making, and conciliation. These

charges contained broad allegations that blacks were denied job

opportunities due to past discriminatory policies. Several of

the charges contained specific allegations of discriminatory

hiring policies, the maintenance of segregated seniority lists

and jobs, the use of tests and educational standards which

denied transfer opportunities -to blacks, the maintenance of

seniority provisions which resulted in the loss of job 2/

seniority upon transfer, and the payment of discriminatory wages.

[See EEOC charges of W. Green, J. Williams and I. Arnold].

1/ The Court has granted permission to use a deferred appendix. The bracketed material refers to documents in the record which

will become part of the deferred appendix.

2/ As to the issue of discriminatory testing and other selection

standards, Mr. Williams alleged:

I am certain that whites hired before me and after me have transferred to both the Operations and Engineering

Divisions even though they scored less than I on one or

both tests and did not possess a high school diploma.

Furthermore, I do not believe it fair or lawful that

(footnote continued)

3

In its administrative determination on the eighteen charges,

the EEOC found that DuPont had discriminated against incumbent

black employees in a number of ways. The Commission found that

DuPont had hired blacks exclusively into the "classification"

seniority division until November, 1971. [EEOC Determination

at 1-2]. While job segregation had been total as to blacks

throughout the company's history, DuPont had allowed whites after

1956 to be hired into "black" seniority divisions. [Id.]. The

Commission's determination substantiated allegations that,

contemporaneous with DuPont's allowance O'f transfers between

seniority divisions, it had imposed new testing and educational

2/(footnote continued)

the company would seek to apply higher standards for

transfer from the classification division after they

ceased an overt policy of racial separation in 1956 than

they applied to whites at the time I was first employed.

I believe the company did,,in 1956 create new standards

for entrance into the Operations and Engineering

divisions. The purpose and effect of these standards

of a high school diploma and a test score of 160 on the

Operators test or a score of 48 on the Mechanicals aptitude test was to prevent Negroes hired prior to 1956 from being

able to transfer into the better paying white jobs. These

standards have kept me and a class of Negroes from obtain

ing these previously all white jobs. These few Negroes who met the standards have continued to suffer the effects

of past discrimination by virtue of losing accrued seniority. These high standards and the requirement to

forfeit seniority constitutes present acts of discrimi

nation against me and other Negro employees. . . .

Similarly, on the issue of discriminatory hiring, Mr. I. Arnold in his EEOC charge alleged that "as a class, blacks were not hired

into higher paying jobs." [Charge of I. Arnold].

4

attainment standards. [Id. at 2]. The EEOC found that the tests

given black employees "were not the same and were not of equal

difficulty", as those given to whites. [Id.] . The Commission

also found that white incumbents— the beneficiaries of DuPont's

prior racial hiring policies— were exempt from this testing

requirement. [ Id.] . Finally, the Commission found that the

seniority system, by providing for forfeiture of previously

accrued unit and division seniority, adversely affected transfer

opportunities for blacks who had been assigned to the classifi

cation seniority division on the basis of race. [Id. at 2-3].

After the Commission issued its reasonable cause

determination, Mr. Williams filed a private Title VII and

§1981 action on behalf of a class of 134 black incumbent

employees hired prior to July, 1965. [Williams complaint at

\\ 2 ] . The Williams suit alleged that DuPont's seniority

system and its high school diploma and testing requirements

discriminated against blacks by locking them into

segregated and less desirable job classifications.

After unsuccessful attempts to eliminate the unlawful

practices it had found in its determination, the Commission

brought suit under Title VII alleging that DuPont and the

union unlawfully discriminated on the basis of race at the

Louisville facility. The complaint alleged that DuPont

maintains racially segregated departments and jobs, imposes

other barriers to blacks because of their race, and fails

to hire blacks on the same basis as whites. [EEOC complaint

5

1110] . The complaint alleged that the union violated Title

VII by entering into successive collective bargaining

agreements containing provisions governing seniority, layoff

and recall,and wage rates, all of which perpetuated past

discrimination against blacks. [Id. 1(11].

In 1975, the Williams and EEOC actions were consoli

dated. DuPont and the union resisted discovery into the

establishment of their seniority system or its operation

prior to July 1965. For example, they refused to provide

copies of the early collective bargaining agreements or

documents concerning negotiations of the agreement. [DuPont

answers to EEOC first interrogatories; union response to EEOC

request for production of documents; DuPont answers to EEOC

second interrogatories; DuPont answers to Williams 1976 inter

rogatories; and 1979 interrogatories]. The EEOC in July 1978

moved to compel. [Motion of EEOC for Order Compelling Discovery].

While the EEOC's discovery motion was pending, DuPont and

the union moved for summary judgment. Without ruling on the

EEOC's motion, the court entered summary judgment. None of the

parties filed affidavits in support of or in opposition to the

motions for summary judgment.

2. Record On Motion For Summary Judgment

In addition to the eighteen charges of discrimination and

the Commission's determination, the following facts appear in the

record:

DuPont's Louisville plant began operations in 1942. [Response

to request for admissions, no. 14]. Since 1954, DuPont and the

6

Neoprene Craftsmen Union have entered into collective

bargaining agreements which have affected the seniority

rights of employees. [Response to request for admissions,

no . 7 ] .

Between 1954 and the present time, the Louisville

plant had four "master" seniority divisions: engineering,

3/

operations, utility and classified; prior to April 1956,

the collective bargaining agreement prohibited all transfer

between seniority divisions. [Response to EEOC request for

admissions, no.22].

Blacks have been historically hired into and assigned

to the classified seniority division. [McConnell dep. 60-61;

Cressey Dep. at 30; EEOC Determination at 1-2; Appendix A to response

to EEOC's second interrogatories]. As of December 31, 1973, the

engineering seniority division was composed of 306 employees,

none of whom were black (0%); the operations seniority division

was composed of 307 employees,_11 of whom were black (2.8%);

the utility seniority division contained 49 employees, 14 of

whom were black (28.6%); and the classified seniority division

was composed of 166 employees, 123 of whom were black (74%).

[Response to EEOC request for admissions, nos. 33-36]. Prior

to 1972, only one black employee had transferred into the engi

neering seniority division and no black employee had been hired into

3/ [Response to EEOC request for admissions]. Defendants

in the early 1970's established the seniority division of

"firemen." This seniority division, as of December 31, 1975,

had only 6 employees. [Answer to EEOC's first interrogatories,

no. 25] .

7

that division. [Response to EEOC request for admissions,

nos . 31-32] .

Contemporaneous with the 1956 collective bargaining

agreement, which for the first time allowed for transfers

between master seniority divisions, the company established

a high school diploma requirement and the achievement of

a passing score on a written test as preconditions for

transferring to the engineering seniority division.

[Response to EEOC request for admissions, no. 25]. Several

of the white persons employed in the engineering seniority

division prior to 1956 and who were still employed as of

the time of suit did not have a high school education or

its equivalent. [Responses to EEOC request for admissions,

nos. 6, 28]. Many of the white employees employed in

the engineering seniority division in 1956, and some of

the white employees employed i-n that division in 1972,

had not been given a written test. [Response to EEOC

request for admissions, nos. 27, 29]. There are several

white employees in the engineering division who have less

than a seventh grade education. [Response to request for

admissions, no. 33].

After May 1956 the collective bargaining agreement allowed

employees to transfer between the other three master seniority

divisions, except that any employee so transferring would forfeit

his prior unit and division seniority. [Response to request for

admissions, no. 24]. Unit and division seniority provided pro

tection against layoffs and "bumping," and gave priority rights

for recall. [Id., nos. 43, 50].

-8-

In 1973, as a result of a compliance review by the

Atomic Energy Commission, which found that DuPont had

violated Executive Order 11246, DuPont and the union altered

the seniority provisions of the collective bargaining

agreement to provide "master division seniority and

unit seniority and unit seniority equal to plant seniority

for 134 black employees hired prior to August 27, 1962 for

purposes of promotion to, demotion from, and layoff from jobs

in Wage Grades 9 and 10 (but not for other purposes)." [Response

to request for admission, no. 50]. This provision was incor

porated into the 1974 and subsequent collective bargaining

agreements. [ Id . ] .

3. The District Court Decision

The district court made no findings of fact as to the

seniority system. It simply concluded after quoting copiously

from Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), that

In the case at bar there has been no

showing that the seniority system

set up in the collective bargaining

agreement which was reached after

adoption of Title VII was drafted

with an intent to discriminate and

the Court agrees with defendants that the holding in Teamsters, supra

dictates their motion for summary

judgment be granted.

[Memorandum at 5].

As to Williams' claim that Dupont's current testing program

unlawfully discriminates against blacks, the court quoted from

United Air Lines v. Evans, supra, and without further analysis

- 9-

stated that "the only conclusion which the Court can draw

from this language is that Evans dealt a fatal blow to the

concept of 'continuing violation.'" [Id. at 7].

Finally, concerning the scope of the EEOC suit, the court

said that "all claims against defendant [sic] by the individual

employees attacked only the seniority system and its appli

cation." [Id. at 7]. After quoting EEOC v. Bailey Co., 563 F.2d

439, 448 (6th Cir. 1977), the court, without additional analysis,

concluded that "[t]he language compels the conclusion that

the only matter over which this court has jurisdiction is the

complaint dealing with the seniority system." [Id. at 8].

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The trial court did not correctly apply long-estab

lished standards for granting summary judgment under Rule

56, Fed.R.Civ.P., and misconceived the decision of the Supreme

Court in Teamsters v. United Spates, supra, 431 U.S. at 356.

The court acted without giving the parties opposing the motion

the opportunity to conduct relevant discovery and ignored the

facts on the record. Those facts imply that the seniority system

is not "bona fide" because it is irrational and therefore not

"neutral"; "had its genesis in racial discrimination"; and has

not been "negotiated [or] maintained free from illegal purpose."

[Id. at 356]. Insofar as the suit challenges instances of racial

discrimination occurring after the effective date of Title VII

- 10-

which has denied blacks "rightful place" seniority, Teamsters re

inforces rather than undermines the holding in Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

2. The trial court misread the holding in United Air Lines

v. Evans, supra, 431 U.S. at 558, in dismissing the allegations

pertaining to defendants' discriminatory testing procedures.

Evans only dealt with situations, not present in this appeal,

where an instance of unlawful conduct, which was not the sub

ject of a timely EEOC charge of discrimination, is alleged to

be illegal merely because a neutral and otherwise lawful sen

iority system gives present effect to that prior conduct. Here,

both the EEOC and private plaintiffs are challenging the main

tenance of an on-going discriminatory practice of using written

tests. This is a continuing and recurring policy, having an

adverse effect on the employment rights of blacks each time

an employment decision is made on the basis of these invalid

and discriminatory selection procedures.

3. The lower court did not apply the correct legal prin

ciple in denying the Commission the right to litigate claims

aside from the bona fides of the seniority system. The correct

rule, adopted by this Court and approved by the Supreme Court

in General Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 48 U.S.L.W. 4513, 4516 (May

12, 1980), is that the Commission and private litigants may seek

relief for any conduct which was the subject of reasonable

Commission investigation. EEOC v. Kimberly Clark Corp., 511

- 11-

F.2d 1352(6th Cir. 1975); EEOC v. Bailey Company, 563 F .2d 439

(6th Cir. 1977). Allegations concerning discriminatory hiring,

job assignments, and testing, had all been addressed in the EEOC

determination. The Commission investigation which led to that

determination was reasonable because several of the charges

alleged discriminatory hiring, job assignments, and testing

policies.

- 12-

ARGUMENT

I. DEFENDANTS' INTENT IN ADOPTING

AND MAINTAINING THE SENIORITY SYSTEM

CANNOT BE RESOLVED ON SUMMARY JUDGMENT

IN THIS CASE.

In Teamsters v. United States, supra, 431 U.S. at 356, the

Supreme Court held that a seniority system, adopted prior to

Title VII, is bona fide within the meaning of §703(n) if it is

neutral on its face, did not have its "genesis" in racial discrimi

nation, and "was negotiated and has been maintained free from any

illegal purpose." As an affirmative defense to a Title VII action

the burden of proof as to the bona fide nature of the seniority

system rests on the parties asserting the defense.

Whether a seniority system is truly neutral requires more

than an examination of the collective bargaining agreement; it

requires, at the very least, an examination into whether the

seniority system is rational, conforming in some rational manner

to the structure of the plant in which it operates or to industry

practices. See James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310, 352 ( 5th Cir. 1977),- cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034 ( 1978).

Whether the system had its genesis in racial discrimination

or was negotiated and maintained free of discriminatory purpose

requires examination of the origins of the system and the

motivations of the parties to the agreement as reflected in

their actual negotiations and in the surrounding circumstances.

Teamsters v. U.S., supra, 431 U.S. at 356; Fisher v. Proctor

& Gamble Mfg. Co., 613 F.2d 527, 542 (5th Cir. 1980).

- 13-

The district court conducted no such inquiries; worse, it

prevented the plaintiffs from engaging in the discovery

necessary to make them. Even so, the sparse record before the

court demonstrates that the relevant facts and inferences to

be drawn from them are in dispute and that summary judgment

is inappropriate.

(a). The Supreme Court in Adickes v. S ■ H. Kress & Co. ,

398 U.S. 144, 157 (1970), stated the governing principle for

summary judgment:

[T]he moving party. . .ha[s] the burden of

showing the absence of a genuine issue

as to any material fact, and for [the purposes of summary judgment,] the

material. . .must be viewed in the light

most favorable to the opposing party.

In applying this standard, the Court noted that it is the burden

of the party seeking summary judgment to show "conclusively that

a fact alleged. . .was not susceptible of an interpretation that

might give rise to an inference" that a violation cognizable by

the court existed. Id. at 160, n.22. Accord: United States v.

Diebold, 369 U.S. 654, 655 (1962); EEOC v. Local 189, United

Association of Journeymen and Apprentices of Plumbing and Pipe

Fitting Industry, 427 F.2d 1091, 1093 (6th Cir. 1970) ; S.J .

4/ In applying Rule 56, Fed. R. Civ. P., to proceedings under

Title VII, this Court in EEOC v. Local 189, Plumbers and

Pipefitters, supra, 427 F.2d at 1093 noted:

We have disapproved the use of summary

judgment where, although the basic facts were not in dispute, the parties neverthe

less in good faith disagreed concerning the

inferences to be drawn therefrom.

- 14-

Groves & Sons, Co. v. Ohio Turnpike Commission/ 315 F.2d 235, 237

233 (6 th Cir. 1963), cert. denied, 375 U.S. 824 (1963); Hart v.

Johnston, 389 F.2d 239 (6th Cir. 1968); 3ohn Aluminum and Brass

Corp♦ v. Storm King Corp., 303 F.2d 425 (6th Cir. 1962); Rogers

v. Peabody Coal Co., 342 F.2d 749, 751 (6th Cir. 1965).

It is self-evident that employers' and unions' motivations

behind the adoption of one seniority system rather than another

cannot be determined by summary judgment: "Questions of intent

are particularly inappropriate for summary judgment." Fitz

simmons v. Best, 528 F.2d 692, 694 (7th Cir. 1976); Accord,

Smith v. Hudson, 600 F.2d 60, 66 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, dismissed

___ U.S.___, 100 S.Ct. 495 (1979). For that reason, in Acha v.

Beame, 570 F.2d 57, 63 (2nd Cir. 1978), the court of appeals,

in a post-Teamsters seniority system case, vacated a partial

summary judgment, noting that there necessarily existed important

issues of fact concerning the post-Title VII occurrence of

discriminatory behavior, the bona fides of the seniority system,

and the existence of discriminatory intent at the adoption of

the seniority system.

Summary judgment is particularly inappropriate when,

as here, the court had been made aware that DuPont and the

union were impeding discovery covering anything that went

on at the Louisville plant prior to the effective date of

Title VII: "where the need for discovery in order to. . .

substantiate the claims asserted is clear, and where

plaintiff was effectively denied the opportunity to engage

in that discovery," summary judgment must be denied.

- 15-

Cedillo v. Ironworkers Local 1, 603 F.2d 7, 12 (7th Cir.

1979), citing Toebelman v. Missouri Kansas Pipe Line Co.,

130 F . 2d 1016 (3rd Cir. 1942). Cf_. Hospital Bldg. Co.

v. Rex Hospital Trustees, 425 U.S. 738, 746 (1976)

(dismissals prior to "ample opportunity for discovery" are

disfavored.)

(b). Although the evidence in the record is incomplete

because of DuPont's resistance to relevant discovery, the

inference is strong that its seniority system had its genesis

in racial discrimination; had been adopted and maintained for

discriminatory purposes; and is not "neutral" on its face, in the

sense that it is irrational and has a harsher impact on blacks

than whites.

When the seniority system was adopted all blacks were segre

gated into the classification master seniority division and all

whites were in the other threê 'd ivisions. Such racial segregation

is inherently suspect. DuPont and the union did not seek to rebut

the inference of prior job segregation during the formulation of

the seniority system, as by a demonstration that few or no blacks

possessed the skill or educational levels necessary to perform

the work in the other three divisions. In fact, an inference

can be justifiably made that many of the white jobs were un

skilled based on DuPont's admission that whites with minimal

education (less than 7th grade) had been hired into jobs from

which blacks had historically been excluded. Moreover, the 1956

system was irrational, being unrelated to the plant's functional

divisions. See Williams' brief at 32-33. In fact, the sole

justification for the classification division, it seems, was to

- 16-

ensure that in an area where racial segregation was common, blacks

would not be able to move into white jobs.

That an avowed purpose of the original seniority system

was to "keep blacks in their place" may also be inferred from the

subsequent acts of DuPont and the union. When blacks were

finally permitted to seek transfer to jobs in other seniority •

divisions as a result of the 1956 agreement, DuPont con

temporaneously imposed the requirements that to be eligible

for transfer applicants must have a high school education and

must achieve specified score levels on written tests. White em

ployees already in these jobs were exempted from the requirement

that they demonstrate their "ability" and were excluded from

the requirement that they possess a minimum educational attain

ment level. The obvious and foreseeable effect of these policies

was the continued segregation of blacks.

When a seniority system which is irrational is superimposed

on racially segregated jobs and serves to ensure continued segre

gation, the inference that the system is not truly neutral, that

it had its genesis in racial discrimination, and that it has been

maintained with an illegal purpose becomes inescapable. When viewed

under the standards of Adickes v. S.H♦ Kress & Co., supra, 398

U.S. at 157, the undisputed facts in the record and necessary

inferences which they evoke leave no doubt that summary judgment

was inappropriate, and that the EEOC and private plaintiffs must

be permitted a trial on their claims that the seniority system

is not bona fide and the use of that system is unlawful.

- 17-

(c) . The trial court was also incorrect when, applying

Teamsters, it exclusively referred to the collective bargaining--------- _ 5/

agreements effective after the enactment of Title VII.

By its very terms Teamsters requires inquiry into the

genesis of the system, not its most recent readoption.

Thus, every court to have considered whether a seniority system

was "bona fide" under Teamsters looked into the facts and cir

cumstances surrounding the adoption of the system. For example,

the Fourth and Fifth Circuits in Patterson v. American Tobacco

Co. , 586 F.2d 300 , 304 ( 4th Cir. 1978 ), and James v. Stockham

Valves, supra, 559 F.2d at 353, directed their respective

district courts in applying Teamsters to inquire into the

circumstances surrounding the pre-Act adoption of the

seniority system. See also Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Sante

Fe Railroad Co., 454 F.Supp. 158,174 (D.Kan. 1978) (creation

of seniority system in 1890's); Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal,

5/ In its memorandum opinion, the trial court stated:

In the case at bar, there has been no

showing that the seniority system set

up in the collective bargaining agree

ment, which was reached after the adoption

of Title VII, was drafted with an intent

to discriminate and the court agrees with

the defendants that the holding in Teamsters

supra, dictates their motion for summary

judgment be granted.

[Memorandum Opinion, at 5].

- 18-

___F.Supp.___, 15 FEP Cases 822, 826 (N.D.Ind. 1977) (seniority

system developed in 1950's); Croker v. Boeing Co. Vertol Div.,

437 F.Supp. 1138, 1187 (E.D. Pa. 1977) (development of seniority

system in 1950's). By not looking to collective bargaining

agreements which predated the adoption of Title VII, the trial

court clearly misapplied Teamsters.

(d). Finally, the trial court's grant of summary judgment

cannot be sustained on the basis of Teamsters with regard to

the allegations of discriminatory hiring, job assignments, trans

fer policies, and other discriminatory terms and conditions of

employment, occurring after the effective date of Title VII.

In fact, the Teamsters decision mandates a reversal on these

aspects. In Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 347, the Court noted:

Post-Act discriminatees, however, may

obtain full 'make whole' relief, including

retroactive seniority under Franks v .

Bowman, supra, [424 U.S. 747 (1976)]

without attacking the legality of the

seniority system as applied to them.

Franks made clear. . .that retroactive

seniority may be awarded as relief from an employer's discriminatory hiring and

assignment policies even if the seniority

system agreement itself makes no pro

vision for such relief.

See Acha v. Beame, supra, 570 F.2d at 64; Patterson v. American

Tobacco Co., supra, 586 F.2d at 303; James v. Stockham Valves,

supra, 559 F.2d at 351; Fisher v. Proctor & Gamble Mfg. Co.,

supra, 613 F.2d at 542-43.

In the present case, the Commission is clearly challenging

DuPont's post-Act discriminatory hiring policies, its job

assignment policies, and its testing and other qualification

- 19-

standards, which have continuously restricted blacks to their

jobs in the classification seniority division. Failure to

give post-Act rightful place seniority is a violation of

Title VII, whether or not the seniority system is bona fide.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, 424 U.S. at 757-762.

As the Supreme Court has recently made clear, discriminatory

testing and other job qualification standards as those here at

issue are not part of a seniority system within the meaning

of Teamsters. California Brewers Association v . 3ryant, ___U .S.

___, 63 L.Ed. 2d 55, 65-66 , 100 S.Ct. 814, 825 (1980). See also,

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., supra, 586 F.2d at 303.

II. THE DECISION IN UNITED AIR LINES

v. EVANS, 431 U.S. 553 (1977), DOES

NOT SUPPORT SUMMARY JUDGMENT.

On the basis of the Supreme Court's decision in United

Air Lines v. Evans, supra, the trial court also held that

plaintiff Williams, and presumably the EEOC, could not

challenge DuPont's testing requirements and other qualification

standards for transfer and promotion. [Memorandum Opinion at 6].

Evans has no bearing on this case. The allegedly illegal

testing is a present violation of Title VII. As the court of

appeals stated in Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., supra,

586 F.2d at 304, in Evans,

[the Supreme Court] did not deal with a

continuing violation such as a dis

criminatory promotional system where

the discrimination continues from day

to day and a specific violation occurs

whenever a promotion is made.

- 20-

See Acha v. rieame, supra, 570 F.2d at 65.

The record reveals that DuPont, from 1956 to the present,

administered tests as a condition for hire and for transfer into

jobs outside the classification seniority division. Maintenance

of a discriminatory testing policy, unlike the discharge in

Evans, continues to affect adversely the promotional and hiring

opportunities of blacks who have either applied for employ

ment or transfer or who have been deterred from doing so by

reason of this policy. International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, supra, 431 U.S. at 356.

We submit that the trial court did not properly examine the

nature of the allegation that blacks are subjected to a discrimi

natory testing policy. Such a policy, still in effect, has a

continuing and recurring adverse impact on the employment rights

6/of blacks.

This Court has recognized the concept that certain employment

policies are continuing violations and may be challenged at any

time when the policy adversely affects employment rights. In

6/ The continuing nature of the policy was perceived by

Mr. Williams in his EEOC charge.

I am certain that whites hired before me and after me have transferred to both the Engineering

and Operations Divisions even though they scored

less than I on one or both tests and did not

possess a high school diploma. (Emphasis supplied).

[Charge of J. Williams].

- 21-

Morelock v. dCR Corp., 536 F.2d 1096, 1103 (6th Cir. 1978), a case

arising under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C.

S621, et sea-, this Court held that discrimination resulting from

the application o£ seniority provisions constituted a continuous

violation of the statute "as long as that system is maintained

by the employer." DuPont's testing policies are clearly of the

same nature and, as in dorelock, are subject to challenge as

long as they exist.

Evans dealt with a completed act of discrimination several

years in the past; that decision manifestly does not affect

the ability of EEOC or private plaintiffs to challenge the

maintenance of a continuing, recurring policy which, by its own

terms, currently affects present employment and promotional

opportunities .

III. THE ALLEGATIONS IN THE EEOCCOMPLAINT ARE PROPERLY BEFORE

THE COURTT

in granting summary judgment on the "non-seniority" allegations

of discriminatory hiring and transfer policies, the trial court held

that the Commission incorrectly expanded the scope of the claims.

The court felt that all claims against the defendant by the in

dividual employees attacked only the seniority system and its

application. [Memorandum Opinion at 7]. We submit tnat tne trial

court misread the nature of the applicable EEOC administrative

charges and did not apply the proper legal standard governing

litigation under Title VII.

The district court's approach that litigation under Title VII,

- 22-

whether by the Commission or a private party, is tied to the

precise allegations in the EEOC administrative charge of dis

crimination has been universally rejected. Rather, this and other

courts have adopted the principle that a suit under Title VII

is limited to the scope of the EEOC investigation which would

reasonably be expected to grow out of the charge of discrimi

nation; the Supreme Court has approved that principle. See

General Tel. Co. v. EEOC, 48 U.S.L.W. 4513 , 4515. (May 12, 1980);

EEOC v. Kimberly Clark Corp., 511 F.2d 1352, 1353 (6th Cir.),

cert. denied, 423 U.S. 994 (1975); EEOC v . Bailey Co.,

supra; Tipler v. E.I. DuPont, 443 F.2d 125, 131 (6th Cir.

1971); Evans v. Delta Air Lines, 551 F.2d 113, 115 (6th Cir.

1977) . Accord: EEOC v. Occidental Life Insurance Co., 535

F.2d 533, 541 (9th Cir. 1976), aff'd on other grounds, 432 U.S.

355 (1977); Jenkins v. Blue Cross Mutual Hospital, 538 F.2d

164, 167 (7 th Cir. 1976), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 986 (1976);

EEOC v. riuttig Sash & Door, 511 F.2d 453, 455 (5th Cir.

1975); Sanchez v. Standard Brands, 431 F.2d 455, 466 (5th

Cir. 1970); EEOC v. General Electric Corp., 532 F.2d 359, 364

(4th Cir." 1976) .

In applying this principle to this appeal, there can be no

doubt that all of the allegations of the complaint were the subject

of an EEOC investigation. In its determination, the Commission

specifically found that DuPont discriminatorily hires blacks by

assigning them to positions in the classification seniority

division, and that discriminatory testing restricts the transfer

opportunities of blacks. The Commission found that these policies,

although imposed prior to the effective date of Title VII, are

- 23-

presently used to deny employment opportunities to blacks.

[EEOC Determination at 2-3].

The trial court was factually incorrect in finding that

the EEOC investigation was based on administrative charges which

related solely to seniority issues. Rather, the EEOC deter

mination was based on charges which explicitly alleged the

existence of a prior practice of hiring discrimination and the

imposition of employment testing and education standards which

adversely affected the transfer opportunities of blacks. [See

charges of J. Williams and I. Arnold]. It is certainly rea

sonable for the Commission to have investigated whether such

allegations of unlawful policies were currently extant. Upon

such a finding it is certainly within the scope of this Court's

decisions in Kimberly Clark, Bailey, and DuPont, that the

Commission be entitled to bring suit to end such practices.

The lower court's reliance on EEOC v. Bailey Co., supra,

563 F.2d at 446, is misplaced. In Bailey, this Court reaffirmed

its rule that the scope of a Commission law suit relates, not to

the allegations of the charge, but to the issues which were

the subject of a reasonable investigation of the charge. On

the specific facts present in Bailey, the Court held that a

"reasonable investigation" of a charge, alleging sex discrimination,

would not reasonably encompass a finding of discrimination based

on religion against Seventh Day Adventists. Clearly, this is

not the situation here, where all of the findings by the

Commission in its determination have direct antecedents in

the allegations of the administrative charges.

- 24-

CONCLUSION

Summary judgment should be vacated.

Respectfully submitted,

LEROY D. CLARK

General Counsel

JOSEPH T. EDDINS

Associate General Counsel

LUTZ ALEXANDER PRAGER

Attorneys

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

2401 E Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20506

(202) 634-6150

May 22, 1980

- 25-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that copies of the foregoing brief

have today been mailed postage prepaid, to the following

counsel of record.

Edgar A. Zingman Esq.Sheryl G. Snyder, Esq.

Robert B. Vice, Esq.Wyatt, Grafton & Sloss

2800 Citizens Plaza Louisville, Kentucky 40202

Charles W. Brooks, Jr.,

Borowitz & Goldsmith

310 West Liberty Louisville, Kentucky 40202

Patrick O. Patterson

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

Daniel HallJones, Rawlings, Keith & Northern

504 Portland Federal Building

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

James C. HickeyEwen, Mackenzie & Peden, P.S.C.

2100 Commonwealth Building

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION

2401 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506

May 22, 1980

11 >. . WL ■ »•». ’ % a-'..