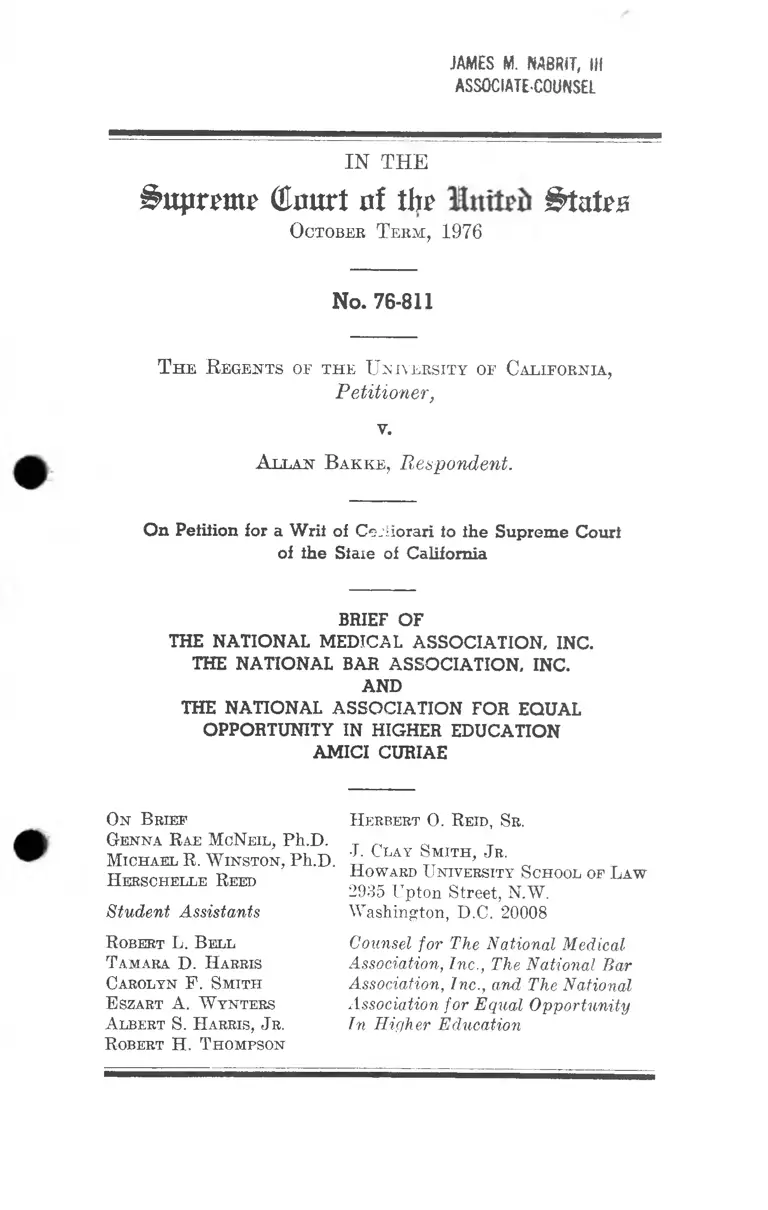

Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Medical Association, The National Bar Association, and The National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 6, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Medical Association, The National Bar Association, and The National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education Amici Curiae, 1977. b08fb83b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d66df181-a855-4a37-aa76-4fa1ad16a108/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-the-national-medical-association-the-national-bar-association-and-the-national-association-for-equal-opportunity-in-higher-education-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. fWBRIT, III

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

IN THE

Supreme (Emtrt n! Hit States

October T erm, 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of the U niversity of California,

Petitioner,

v.

A l l a n B a k k e , Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ of Ce.'iiorari to the Supreme Court

of the Staie of California

BRIEF OF

THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, INC,

THE NATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION, INC.

AND

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR EQUAL

OPPORTUNITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION

AMICI CURIAE

On Brief

Genna Rae McNeil, P h .D .

Michael R . Winston, P h .D .

Herschelle Reed

Student Assistants

Herbert 0. Reid, Sr.

•I. Clay Smith, J r.

Howard University School of Law

2935 Upton Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008

Robert L. Bell

Tamara D . Harris

Carolyn F . Smith

Eszart A. Wynters

Albert S. Harris, J r.

Robert H. Thompson

Counsel for The National Medical

Association, Inc., The National Bar

Association, Inc., and The National

Association for Equal Opportunity

In Higher Education

INDEX

Page

Opinions B elow ....................................................................... 1

J urisdiction ............................................................................. 2

Questions P resented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional P rovision ............................................. • • • 2

Consent to F iling ................................................................ 2

I nterest of the A mici Curiae ........................................... 2

S tatement op the Ca s e ........................................................ 2

Argument ................................................................................. 9

I. T he State of California's “ A ffirmative A c

tion” P rogram in E ducation and I ts Constitu

ent Admissions at the Davis Medical S chool

A re P ermissible U nder the F ourteenth

A mendment .................................................................. 9

II. T he U se of R acial Classification to P romote

I ntegration or to Overcome the E ffects of

P ast D iscrimination I s N either “ S uspect”

N or P resumptively U nconstitutional ............. 33

III. T he R ation ale of B rown Commands the R e

versal of the California S upreme Court . . . . 56

Conclusion ............................................................................... 75

A ppendix A ................... l a

A ppendix B ................. 12a

A ppendix C 13a

11 TABLE OF AUTHORITY

Table oe Cases: Page

Allen v. Superior Court In and For San Diego County,

340 P.2d 1030, 171 C.A. 2d 444 (1959) ................. 23

American Communications Association v. Douds, 339

U.S. 382 (1950) .......... ....................................... 50

BaJcke v. Regents of University of California, 553 P.2d

1152 (1976) ............ 32,34,41,70

Banks v. Housing Authority of the City and County of

San Francisco, 260 P.2d 668, 120 Cal. App. 2d 1

(1953) ........................................................ 12

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908) ......... 40

Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971). 44,45, 56

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ................... 40,41

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960) .................. 24

Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 U.S. 277 (1937) .................... 38

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, (1954) 349

U.S. 294 (1955) ....................... 19, 24, 40, 41, 46, 52, 71

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ...................... 38

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), cert.

denied 406 U.S. 950, 32 L.Ed. 2d 338 (1972) ......... 44

Castro y . California, 466 P.2d 244, 85 Cal. Rptr. 20

(1970) ................................................................... 10

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ......................... 34

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323 (1926) .................. 38

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 551 P.2d 28, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724 (1976) . . 21

Gumming v. Richmond, County Board of Education,

175 'U.S. 528 (1899) . . . . ! .................................... 36,40

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 1038 (1974) ................ 48

Dennis y . United, States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951) ............ 50

Dred Scott v. Sanford, 19 How. 393 (1856) ....... 10,58, 73

F. S. Royster Guano Co. v. Virginia, 253 U.S. 412

(1920) ................................................................... 47

Fairchild v. Raines, 151 P.2d 260, 24 Adv. Cal. 812

(1944) .................................................................... 12

Firth v. Marowick, 116 P. 729 (1911) ......................... 12

Fletcher v. Peck, 6 Cranch 87 (1870) ........................... 50

Forest Laivn Association v. de Jarnette, 250 P. 581, 79

Cal. A pn. 601 (1926) .............................................. 12

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903 (1956) .................... 39,41

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78 (1927)_....................... 40

Grovery v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45 (1936) ................ 38

Guinn v. 77.,S’., 238 U.S. 347 (1915) .......................... 38

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U.S. 609 (1927) ....................... 38

Hill y . Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) ................................ 38

Table of Authority Continued m

Page

Hodges v. United States, 203 TJ.S. 1 (1906) ............ 39, 50

Home Teleph. and Teleg. Co. Los Angeles, 227 U.S.

278 (1913) ............................................................ 12

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 TJ.S. 388 (1969) ................... 41

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 382 P.2d 878,

31 Cal. Rptr. 606 (1963) ....................... ........... 15

Jones y. Mayer Co., 392 TJ.S. 409 (1968)....... 38, 41, 42, 59

Korematsu v. United States, 323 TJ.S. 214 (1944)....... 46

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) .......................... 38

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ............................ 18

Lee v. Johnson, 404 U.S. 1215 (1971) ................ 18,19

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963) ................ 39

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186

P. 596 (1919) ...................................................... 11

Mayor of Baltimore v. Dawson, 350 U.S. 879 (1955).. 39

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad,

235 U.S. 151 (1914) ............................................ 39

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 13 L.Ed. 2d 222

(1964) ............................................................... 46,47

McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U.S. 639 (1950)............ 41, 50

Mendez v. Westminister School District of Orange

County, 64 F. Supp. 554 (1946), affirmed 161 F. 2d

724 ( ) ............................................................ 14

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1937) 41

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923) ....................... 39

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ..................... 67

Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502 (1934)_ . ; ............ . 47

New Orleans Park Improvement Association v. De-

tiege, 358 U.S. 54 (1955) ..................................... 39

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) ....................... 38

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1933) ..................... 50

Norwalk Core v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395

F.2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968) ..................................... 48

Pearson v. Murray, 182 A. 590 (1936) ....................... 41

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P.2d 17 (1948).... 10

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ................ 35, 56

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970)............. 40

Reitman v. Mulkey, 413 P.2d 825 (1964), affirmed 387

U.S. 369 (1967) ................................................... 13

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

411 TJ.S. 1 (1973) ................. ....................... 19

San Francisco Unified School District v. Johnson, 3

Cal. 3d. 934, 479 P.2d 669 (1971) ......................... 21

Serrano v. Priest, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601 (1971) ........ 18

iv Table of Authority Continued

Page

Shelly v. Kramer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .................... 12, 38, 50

Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) .................... 41

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36 (1873) . . . . 35,41,73

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ............................. 38

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966).. 33

Steele y . Louisville and Nashville Railroad Company,

323 U.S. 192 (1944) ........................................... 39, 50

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) . . . . 46, 50

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ......................................... 44,45,46

Sweatt y . Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ....................... 41

United Jewish Organization v. Carey, — U.S. —, 97

_ S.Ct. 996 (1977) .................................................... 32

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876)....... 35

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F. 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966); cert, denied 389 U.S.

840, 19 L.Ed. 2d. 103 (1967) ................................ 44

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36,17 Am. Rep. 405 (1874) . . . . 16

Wayt v. Patee, 205 Cal. 46, 269 P.660 (1928)............ 12

Wong Him v. Callahan, 119 F. 381 (1902) ................ 17

Constitution :

U.S. Constitution Amendment X I I I ....... . 32, 35, 74

U.S. Constitution Amendment XIV ................... passim

U.S. Constitution Amendment X V ................ ........... 33

S tatutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI, 42 U.S.C. 2000d. .18, 32

12 Stat. 796 (1863) .................................................... 62

13 Stat. 507 (1865) .................................................... 62

14 Stat. 176 (1866) ........................................... 64

15 Stat. 20 (1867) ...................................................... 65

45 Stat. 1021 (1928) ................................................... 68

71 Congressional Globe 918 .............. ......................... 63

74 Congressional Globe 3838 ................................ . 63

California Civil Code, § 53 ......................................... 14

Table of Authority Continued v

Page

California Civil Code, § 782 ....................................... 14

California Election Code, § 201, (West Supp., 1974).. 11

California Election Code § 1611 (West Supp. 1974).. 11

California Election Code § 14201.5 (West Supp. 1974) 11

Concurrent Resolution 151 (ACR 151) (1974)

24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Hawkins Act (Formerly Health & Safety Code, §§

35700-35741) ...................................... 14

Rumford Fair Housing Act (Health and Safety Cal.

Code, §§ 35700-35744) ........................................... 14

School Law, California, April 4, 1870 (LAWS 1869-70,

Pg. 838) .............. 16

The TTnruh Civil Rights Act (Cal. Civil Code, (A 51-52) 14

West Annotated California Codes, Evidence Code,

#451 ........................... 23

R eports :

California Commission Report, “ Equal Educational

Opportunity in California Post Secondary Educa

tion,” Part I (April, 1976) .................................. 24

Commerce Department, Bureau of the Census, “ Popu

lation . . .” (1970) ................................................ 51

Hefferlin, et al, “ California’s Educational Needs: A

Feasibility Study,” Part I (September, 1975).... 23

“ The Bakke Decision: Disadvantaged Graduate Stu

dents” Assembly Education Subcommittee On

Post Secondary Education, California Legisla

ture, Transcript and Statement, Sacramento, Cali

fornia (March 2, 1977) ................................ 24, 42, 43

“ Unequal Access to College: Postsecondary Oppor

tunities and Choices of High School Graduates”,

Assembly Permanent Subcommittee on Postsec

ondary Education, Staff Report, Sacramento,

California (November, 1975) .................. 27, 28, 29, 30

United States Commission on Civil Rights, A Genera

tion Deprived: Los Angeles School Desegregation

(May, 1977) ................................................... 17,18,21

vi Table of Authority Continued

Page

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Desegrega

tion of the Nation’s Public Schools (August, 1976) 18

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Fulfilling

the Letter and Spirit of the Law: Desegregation of

the Nation’s Public Schools (August, 1976)......... 22

United States Commission on Civil Rights, State Poli

cies Against Racial Imbalance (1963) ................ 20

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Iso

lation in the Public Schools (1967) ..................... 19

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Fed

eral Civil Rights Enforcement Effort: To Ensure

Equal Educational Opportunity (January, 1975) .31, 32

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Fifty

States Report, State Advisory Committees (1961) 17

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting

Rights Act: Ten Years After, (January, 1975)... 10

Other A uthokity :

Abramowitz, E. “ Black Enrollment in Medical

Schools: More Promise than Progress.” Howard

Univ., Washington, D.C. (unpublished study 1977) 54

Address by Senator Edward Brooke, “ Crisis in A f

firmative Action” Washington, D.C. (May 25,

1977) ....... ....................................................... 42,72

Address by President Lyndon B. Johnson, Civil Rights

Symposium: Dedication of the Lyndon Baines

Johnson Library, Austin, Texas (December, 1972) 72

Bardolph, The Civil Rights Record. (New York, 1970) 38

Bently, History of the Freedmen’s Bureau. (1974) . . . 65

Berry, Black Resistance/White Law. (New York, 1971) 39

Blackwell, Access of Black Students to Graduate and

Professional Schools, 5 Southern Educational

Foundation (1975) ......................................... 33

Blaustein and Ferguson, Desegregation and the Law

(Knoff, 1962) ............ 56

Dorsen, The Rights of Americans. (New York, 1970) 50

Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Discrimi

nation, 41 IT. Chi. L. R. 723 (1974) ..................... 46

Fleming, J., The Lengthening Shadow of Slavery.

(Washington, D.C., 1976) ................................... 39

Griffin, Admissions: A Time for Change, 20 How. L.J.

128 (1977) .............. 52

Table of Authority Continued vii

Page

Gnnther, Foreword: In Search of Evolving Doctrine

on a Changing Court: A Model for a Newer Equal

Protection, 86 Harv. L.R. (1972) .............. ......... 47

Hansen, The Immigrant in American History. (1940) 71

Hastie, W., Toward An Equalitarian Legal Order, 407

Annals of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science, (1973) .......................................... 38

Houston, “ The Need for Negro Lawyers,” 4 Journal

of Negro Educat-ion, 49 (1935) ........................... 51, 52

House Report No. 121 (July 15, 1870) ....................... 65

Karst, Affirmative Action and Equal Protection, 60

Ya. L.R. 955 (1974) .............................................. 60

Kluger, Simple Justice. (New York, 1977) ................ 39

Kongsgaard, Thomas, Judicial Notice and the Califor

nia Evidence Code (1966) ................................... 24

Logan, Betrayal of the Negro (New York, 1965)....... 38

Logan, Howard University The First Hundred Tears

1867-1967 (New Yorkj 1969) ............................ _. . 65

Mangum, The Legal Status of the Negro. (Chapel Hill,

1940} ................ ..., .............................................. 38

McNeil, Charles Hamilton Houston 3 Black L.J. 123

(1974) ................................................................... 40

Miller, The Petitioners. (New York, 1956) .................. 39

Ming, Racial Restrictions and the Fourteenth Amend

ment: The Restrictive Covenant Cases, 16 U. Chi.

L. Rev. 203 (1949) .................. ....................... 12

Morse, Bakke, v. Regents of the University of Califor

nia: Preferential Racial Admissions, An Uncon

stitutional Approach Paved with Good Intentions

12 New England Law Rev. 719 (1977) ................ 9

Murray, State’s Laws On Race & Color, (Cincinnati

Supp. 1955) .......................................................... 10

National Bar Association, “ Survey of the Black Law-

■ yer” , Washington, D'.C. (1972) ........................... 51

Note, “ Developments in the Law of Equal Protec

tion”, 82 Harvard L. Rev. 1065 (1969) .............. 47

Raper, The Tragedy of Lynching (Chapel Hill, 1933) 39

Rudd, Memorandum to the Executive Committee, As

sociation of American Law Schools, Washington,

D.C. (April 1, 1977) ............................................ 50

Shuman, A Black Lawyers Study, 16 Hoiv.L.J. 225

(1971) ....................... ........................................... 53

viii Table of Authority Continued

Page

Slocum, “ Statistical Information of The Black Law

yer”, Council on Legal Education Opportunity,

Washington, D.C. (April 7, 1977) ...................... 51

Smith, Towards a Houstonian School of Jurispru

dence and the Study of Pure Legal Existence. 18

How.L.J. (1973) ..........................................48,57,60

Spero and Harris, The Black Worker (Reprint ed.,

New York, 1968) ................................................. 39

Styles, Negroes and the Law, (1937) ....................... .. 52

Tollett, Black Lawyers, Their Education and the Black

Community, 17 How. L.J. 326 (1972) ................ 49, 53

Tollett, “ Present Context of Graduate Education and

the Potential Impact on Minority Participation”

(Spring, 1975) (Unpublished paper at the How

ard Univ. Institute for The Study of Educational

Policy, 1975) ......................................................... 70

U. S. President, Lyndon B. Johnson, “ Message Rela

tive To The Right To Vote”, Washington, D.C.

(March 15, 1965) .................................................. 61

Watson, “ The Future of Graduate and Professional

Schools, Conference on Advancing Equality of

Opportunity: A Matter of Justice” (Washington,

D.C., May 15, 1977) ............................................ 52

Weaver, Negro Labor (New York, 1946) .................... 39

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, (New

York, 1866) .............................................. ............ 38

IN THE0tsprm£ (Emxrt nf t e Inttefc l&ates

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

T he R egents of the U niversity of California,

Petitioner,

v.

A llan Bakke, Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

of the State of California

BRIEF OF

THE NATIONAL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE NATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION, INC.

AND

THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR EQUAL

OPPORTUNITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION

AMICI CURIAE

OPNIONS BELOW

The opinion of the California Court is reported at 18

Cal.3d 34, 132 Cal. Rptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152 (1976). The

order denying the University’s petition for rehearing is

not reported. The modification to the California Supreme

Court’s opinion prompted by7 the University’s rehearing

petition is reported at 18 Cal.3d 252b. The opinion of the

state trial court, the trial court’s “ addendum to notice of

intended decision,” its findings of fact and conclusions of

law and its judgment are not reported. These several

opinions and actions of the California Courts are reprinted

2

as Appendices A through Cf to the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari filed herein. The ease proceeded directly from

the trial court to the highest state court. Accordingly,

there is no intermediate appellate court opinion.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1257

(3). Certiorari was granted on 22 February 1977.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Is it constitutionally permissible for a state medical

school to utilize as criteria for selection, among qualified

applicants to study medicine, factors such as the appli

cant’s race, sex, work experience, prior military experi

ence and other background for the purpose of increasing

the access of minority students to medical education, im

proving the quality of the medical education of all its

students, and producing graduates best calculated to im

prove and extend medical care to the State’s inhabitants?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States provides:

. . nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.”

CONSENT TO FILING

This Amici Curiae brief is being filed with the consent

of all parties to the proceeding.

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The National Medical Association is a professional or

ganization which represents the 8,000 American Physi

cians who are Black. The objectives of the National

3

Medical Association are to raise the standards of the

medical profession and of medical education; to stimulate

favorable relationships among all physicians; to nurture

the growth and diffusion of medical knowledge; to sponsor

the education of the public concerning all matters affecting

the public health; to sponsor the enactment of just medical

laws; and to eliminate religious and racial discrimination

and segregation from American medical institutions.

The Association was formed in 1895 in Atlanta, Georgia,

and incorporated in St. Louis, Missouri, August 31, 1923,

under the laws of the State of New Jersey.

The Association maintains national headquarters at 1720

Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. (20036).

It publishes a monthly scientific journal entitled The Jour

nal of the National Medical Association and an all-member

ship news and features publication entitled NMA News. Its

president is Dr. Arthur H. Coleman, San Francisco, Cali

fornia.

The National Bar Association is a professional member

ship organization which represents the more than 7,000

Black attorneys in the United States.

The National Bar Association was incorporated under

the laws of the State of Iowa in 1925, over two decades

before Black attorneys were allowed membership in the

American Bar Association, and at a time when very few

law schools in the United States admitted Black enrollees.

The Articles of Incorporation of the NBA state the objec

tives of the Association as being, in part, to :

“ [A]dvanee the science of jurisprudence, uphold the

honor of the legal profession, . . . and protect the civil

and political rights of all citizens of the several states

and of the United States.”

One of the primary reasons for the birth of the Associa

tion in 1925, was to achieve equalization of opportunities

4

for minorities in the legal profession in order to further

the goal of equal justice for all. In its fifty-two years, the

Association has seen the number of Black attorneys in the

United States grow from a fraction of a percentage point

of the total to almost 2% today. However, Blacks (as well

as other minorities and women), are still grossly under

represented in the legal profession—and, for that matter,

in the medical and other professions, as the text of the

BakJce case indicates.

Thus far, the most effective methods proven to ameliorate

that condition, and certainly the most critical factors in

the doubling of the number of Black attorneys in America

in the past decade, have been the affirmative action pro

grams initiated by a number of law schools since around

1968. This was also the year that the National Bar Associa

tion, in partnership with the ABA, the American Associa

tion of Law Schools and the Law School Admissions Coun

cil, founded the Council on Legal Educational Opportunity,

whose stated goal was to increase the enrollment of minor

ity students in American law schools.

The legal profession has perhaps been more significant

than any other in shaping the fortunes and destinies of the

American people, majority and minority alike. It is common

knowledge that until a few’ years ago, all but a minuscule

number of Blacks were excluded from the profession. In

fact, as recently as 1950, Blacks were forced to invoke the

powers of the U.S. Supreme Court in order to gain admis

sion to tax-supported law schools in parts of this country.

Although the situation is somewhat better today, it would

not be inaccurate to state that, at our present rate of prog

ress, we are still many years away from true equality in

our justice system and proportionate representation of

Blacks in the legal profession.

The Association maintains a National Headquarters at

1900 L Street, NAT., Washington, D.C. (20036). Its presi

dent is Carl J. Character, Cleveland, Ohio.

5

The National Association for Equal Opportunity in

Higher Education, 2001 S Street, NW., Washington, D.C.

(20009), organized October 7, 1969, is a voluntarily inde

pendent association of Presidents of 107 predominantly

Negro Colleges and Universities.

Its Board of Directors and officers are as follows:

President—Dr. Charles A. Lyons, Jr., Fayetteville State

University, North Carolina.

Vice President—Dr. Luther H. Poster, Tuskegee Institute,

Alabama.

Vice President—Dr. Samuel L. Myers, Bowie State College,

Maryland.

Vice President—Dr. J. Louis Stokes, Utica Junior College,

Mississippi.

Secretary—Dr. Milton K. Curry, Jr., Bishop College, Texas.

Treasurer—Dr. M. Maceo Nance, Jr., South Carolina State

College, South Carolina.

Immediate Past President—Dr. Herman B. Branson, Lin

coln University, Pennsylvania

Dr. Ernest A. Boykins, Mississippi Valley State University,

Mississippi.

Dr. Oswald P. Bronson, Bethune-Cookman College, Florida.

Dr. Samuel D. Cook, Dillard University, Louisiana.

Dr. Norman Francis, Xavier University, Louisiana

Dr. Charles L. Hayes, Albany State College, Georgia.

Dr. Frederick S. Humphries, Tennessee State University,

Tennessee.

Dr. Allix B. James, Virginia Union University, Virginia.

Dr. Luna I. Mishoe, Delaware State College, Delaware.

6

Dr. Lionel H. Newsom, Central State University, Ohio.

Dr. John A. Peoples, Jr, Jackson State University, Missis

sippi.

Dr. Henry Ponder, Benedict College, South Carolina.

Dr. Prezell R. Robinson, Saint Augustine’s College, North

Carolina.

Dr. James A. Russell, Jr., Saint Paul’s College, Virginia.

Dr. Julius S. Scott, Jr., Paine College, Georgia.

Executive Secretary—Miles Mark Fisher, IV.1

This Association was organized to articulate the need

for higher education systems not limited as to quantity or

quality by race, income, or previous educational limitations

nor other determinants not based on abiilty.

This is an association of those Colleges and Universities

which are not only committed to this ultimate goal, but are

now fully committed in terms of their resources, human

and financial, to achieving this goal. The Association pro

posed, through the collective efforts of its membership, to

promote the widest possible sensitivity to the complex fac

tors involved and the institutional commitment required to

create successful higher education programs for students

from groups buffered by the racism, exploitation, and neg

lect of the economic, educational and social institutions of

America.

Thus, this Association has a unique interest in this

litigation.

These historically Black institutions without exception

have, from the very beginning of their existence, been open

1 See Appendix A, which list the Presidents of the traditionally

Black Institutions of Higher Education, which constitute the mem

bership of the National Association for Equal Opportunity in

Higher Education.

7

to all races, sex, colors, creeds, and they have always col

lectively offered employment and other incidental privileges

to all who passed through their doors, except where State

law prohibited the same. They have been menders, healers

for wounded minds and restless souls. They have produced

sterling talent which has benefited this Republic beyond

measure of calculation—not only in material contribution,

but intellectual, cultural, moral and spiritual offerings. In

a number of instances, Black institutions have been more

profoundly representative of the American Ethic than the

larger, more affluent, schools of Higher Education in this

country. Indeed, they were founded and remain today as

“ Affirmative Action” programs committed to a public offer

ing of education attainment.

These historically Black Institutions of Higher Educa

tion have welcomed, nurtured and developed the progeny

of the slave system.

The institutions whose views are presented in this Amici

Brief, have backgrounds of perpetual service to all people,

with missions and goals to make educational opportunities

a reality rather than an empty expectation. These institu

tions believe that other institutions with ignominious his

tories of selective exclusion of Blacks, and other minorities

ought to be permitted, and even more so commanded to

adapt and promote “ affirmative action” programs to

achieve minority access to higher education in enrollment,

employment and over all participation where these institu

tions have labored so long in the vineyards alone desper

ately seeking to overcome the disablements visited upon the

principal victims of a racist society.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Allan Bakke, a Caucasian, was denied admission to the

medical school of the Hniversity of California at Davis, a

publicly financed institution, for the academic years com

mencing September 1973 and 1974. In neither year was he

8

accepted by any other medical school. Bakke believed his

rejections were due to the acceptance of less qualified mi

nority applicants admitted under the University’s special

admissions program. This program separately considered

the admissions credentials of disadvantaged applicants

from particular racial groups.

A. The Lower Court Decision

Bakke brought suit against the Board of Begents in Yolo

County Superior Court. He argued that the minority pref

erence program racially discriminated against Mm as a

white applicant, and, therefore was violative of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the

U.S. Constitution, the privileges and immunities clause of

the California constitution, and Title VI of the Civil Bights

Act of 1964. He sought a mandatory injunction and declara

tory relief ordering his admission.

The University contended that Bakke would have been

rejected whether or not it operated a special admissions

program. It filed a cross-complaint for declaratory relief,

however, to enable the trial court to rule independently on

the constitutionality of its minority admissions policy, irre

spective of Bakke’s particular claim.

Begarding this cross-complaint, the court held that the

special admissions program violated the Fourteenth

Amendment of the U. S. Constitution, the California con

stitution, and the Civil Bights Act of 1964. It rejected, how

ever, Bakke’s request for an injunction, finding that he had

not proven he would have secured admission in either year

despite the special program. Although both parties appealed

to the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court of California

assumed control of the case due to the important questions

presented.

B. The California Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s conclusion

that the minority special admissions program was unconsti-

9

tutional. It reasoned that the racial classifications used by

the program denied non-minority applicants admission to a

program they would have enjoyed but for their race. Ac

cordingly, these racial classifications were considered “ sus

pect,” and, therefore, subject to a “ strict scrutiny” equal

protection standard of review. In applying this standard,

the court assumed, arguendo, that most of the program’s

goals established a “ compelling” state interest. Neverthe

less, the court held the program invalid because the Univer

sity had failed to prove that its objectives could not be by

means less burdensome to the majority’s rights.

Concerning Bakke’s prayer for injunctive relief, the

Supreme Court remanded the question to the trial court.

Since Bakke established that the University had discrimi

nated against him, the University, on remand, had the

burden of proving that he would have been denied admis

sion without the operation of the constitutional impermis

sible special minority admissions program. Amici has

adopted the statement of the case from Comment on Bakke

at 12 New England Law Rev. 719 (1977).

A R G U M E N T

I. THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA'S "AFFIRMATIVE ACTION"

PROGRAM IN EDUCATION AND ITS CONSTITUENT AD

MISSIONS PROGRAM AT THE DAVIS MEDICAL SCHOOL

ARE PERMISSIBLE UNDER THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT.

State policy in California, as reflected in (a) judicial

opinions and (b) legislative action, found racial discrimi

nation and exclusion rampant in the state’s experience and

directed and mandated programmatic activity for the pur

pose of bringing about greater access and educational op

portunities for racial minorities in the state.

California, taking its cue from the other states in the

Union perpetuated its badges of slavery. This is illustrated

by an examination of the following areas:

10

A. Miscegenation

California’s miscegenation statute was not declared un

constitutional until 1948. Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal., 2d 711, 198

P.2d 17 (1948), (Miscegenation was a badge listed by Jus

tice Taney, in Bred Scott v. Sanford, 19 How. 393, 403, 407,

(1856), as evidence of the inability of the people of African

descent to become members of the body politic). California

Civil Code, 1949 provided: Section 60. [Marriage of white

and other persons.] All marriage of white persons with

Negroes, Mongolians, members of the Malay race, or mulat-

toes are illegal and void. [Enacted 1872; Amended by Stats.

1905, p. 554; Stats. 1933, p. 561.]

In Perez v. Sharp, supra, it was held that Sections 60 and

69 of the Civil Code were unconstitutional, contrary to the

First and Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of

the United States. See Murray, States Laws on Race and

Color, p. 47 (1955) (Supp.).

B. Voting

In a report by the United States Commission on Civil

Eights; The Voting Rights Act: Ten Years After, January,

1975, substantial racial discrimination against Blacks and

other minorities, in voting in California was documented.

For example, two (2) counties in California—Monterey

and Yuba—-have been brought under the special coverage

of the Voting Eights Act Amendments of 1970. This was a

result of Congress amending the trigger provisions of this

Act to refer to the 1967 election and the 1968 election.

Also, in Castro v. California, 466 P.2d 244, 258, 85 Cal.

Eptr. 20 (1970). The California Supreme Court found that

the state’s English-language literacy requirements to be a

violation of the equal protect! n cl mse of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The court, howere’, did not eliminate the

requirement of literacy altogether, or order the development

of a “ bilingual electoral apparatus”.

11

Subsequently, the California State Legislature enacted

legislation which required county officials to make reason

able efforts to recruit bilingual registrars and election offi

cials in precincts with three (3) percent or more Non-Eng

lish speaking voting age population. Cal. Election Code

§§201,1611 (West Supp. 1974).

In addition, California now requires the posting of a

Spanish-language ballot, with instructions, that also must

be provided to voters on request for their use as they vote.

Cal. Election Code §14201.5 (West Supp. 1974). See Ten

Years After, supra, at 24-25.

Although the impact of the Voting Rights Act has been

the greatest in the southern states, discrimination in voting

is not limited to the south. The Commission on Civil Rights

has emphasized:

“ [T]he problems encountered by Spanish speaking

persons and native Americans in covered jurisdictions

are not dissimilar from those encountered by Southern

blacks. . . . ” Id. at 16.

California law now requires county officials to recruit

bilingual poll watchers. Cal. Election Code § 1611 (West

Supp. 1974). Also, California has recently passed legisla

tion that allows Spanish to be spoken at the polls. Id. at 165.

C. Housing

Racial segregation and discrimination in the area of land

use and occupation, has a shameful history in the State of

California, sanctioned by the legislature and protected by

the judiciary.

The judicial protection is evidenced in Los Angeles Invest

ment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186 P.596 (1919), where the

California Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amend

ment proscription of discrimination against Blacks did not

apply to contracts between individuals. The court concluded

that a provision in a deed which prohibits the occupation

12

of property by anyone not of the white race, is a valid con

dition and not a restraint upon alienation. The proposition

that racially discriminatory covenants restraining the use

or occupancy of land was continuously upheld by the Cali

fornia courts in Wayt v. Patee, 205 Cal. 46, 269 P.660

(1928); Forest Lawn Association v. de Jarnette, 250 P.581,

79 Cal. App. 601 (1926); Fairchild v. Raines, 151 P.2d 260;

24 Adv. Cal. 812 (1944).

A condition in a deed forbidding the renting or sale of

the land to persons other than of the Caucasian race, and

occupation by persons other than of that race was held not

to violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, Home Teleph. and Teleg. Co. v. Los Angeles,

227 U.S. 278, (1913) • Firth v. Marowick, 116 P.729 (1911),

rev’d. 227 TJ.S. 278 (1913).

The aforementioned cases indicate a pattern of de jure

segregation in housing in the early 1900’s.

In Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), the United

States Supreme Court held that it was in violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for

a state court to enforce private agreements to exclude per

sons of a designated race or color from the use or occupancy

of real estate for residential purposes. See Ming, “ Racial

Restrictions and the Fourteenth Amendment: The Restric

tive Covenant Cases,” 16 77. Chi. L. Rev. 203 (1949). De

spite the mandate in Shelly, supra, outlawing state action

in maintaining discriminatory housing patterns, the state

of California failed to act affirmatively to cure its shameful

past history. For, in Ranks v. Housing Authority of the

City and County of San Francisco, 260 P.2d 668, 120 Cal.

App. 2d 1 (1953) at issue was policy implemented by the

housing authority, that allocated dwelling units to racial

groups based on their proportional needs and neighbor

hood racial patterns. The state appellate court found that

the policy was tantamount to the executive branch of the

government enforcing restrictive covenants which the ju-

13

dicial branch is prohibited from doing by the Fourteenth

Amendment. The decision further noted that the housing

authority was exercising state action by preservation, per

petuation and enforcement of a neighborhood racial pat

tern whenever a formal decision was made to locate and

construct a housing project.

In Reitman v. Mulkey, 413 P.2d 825 (1964) affirmed 387

U.S. 369 (1967), the Supreme Court of California consid

ered discrimination practiced by defendant who refused to

rent unoccupied apartments to plaintiffs solely on the

ground that they were Negroes. United States Supreme

Court held that the article of the California constitution

prohibiting the state from denying rights of any person to

decline to sell, lease or rent his real property to such per

son as based on his absolute discretion, constituted affirm

ative action on the part of the state to change its existing

law from a situation where discrimination was legally re

stricted, to one in which it was not. Such discrimination

denied plaintiffs and those similarly situated equal protec

tion of laws as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Federal Constitution. The article was held uncon

stitutional.

The article referred to was Proposition Fourteen [For

merly ART. I § 26] which was incorporated into the Cali

fornia Constitution provided as follows:

“ Neither the State nor any subdivision or agency

thereof shall deny, limit or abridge, directly or indi

rectly, the right of any person, who is willing or de

sires to sell, lease or rent any part or all of his real

property, to decline to sell, lease or rent such proper

ty to such person or persons as he, in his absolute

discretion chooses.”

It was not until 1959 that the State Legislature took the

first steps toward eliminating racial discrimination in

housing. The Unruh Civil Rights Act (Civ. Code, §§ 51-52)

prohibited discrimination on grounds of “ race, color, re

ligion, ancestry, or natural origin” by “ business estab

lishments of every kind”. During the same session the

Legislature passed the Hawkins Act (formerly Health &

Safety Code, §§35700-35741) that prohibited racial dis

crimination in public assisted housing accommodations.

In 1961, Civ. Code, § 53 and Civ Code, § 782 vTere passed

to discourage segregated housing by enacting proscrip

tions aginst discriminatory restrictive covenants effecting

real property interests and racially restrictive conditions

in deeds of real property, respectively.

Finally in 1963 the State Legislature superseded the

Hawkins Act by passing the Rumford Fair Housing Act

(Health & Safety Code, §§35700-35744).

The spirit of the recent affirmative legislation (supra)

to eliminate racial segregation in California was curtailed

with the enactment of Proposition Fourteen. In short,

Proposition Fourteen generally nullified both the Rumford

and Unruh Acts as they applied to the housing market and

was a form of de jure discrimination.

The existence of discrimination in the State of Califor

nia has also been found to exist in studies and reports

conducted by various commissions. For example, in The

Fifty States Report, submitted to the Commission on Civil

Rights by the State Advisory Committees, 1961, pp. 43-44,

the California State Advisory Committee found that

“ [t]he State of California has a large and increasing

Negro population. These people live mainly in segre

gated pattern, in the major urban center of the state.

In most cases, Negro housing areas are considerably

less attractive than housing in other areas. . . . There

still exists the deep fear that property value will ex

perience a severe drop when \Tegro families enter a

previously all-white neighbo uood. In addition, this

fear seems to be shared by businessmen in the real

estate industry who reflect in business attitudes and

15

practices this premise of falling values when integra

tion occurs.” Id. at 44.

The Committee found that the reasons for segregation

are twofold: (1) The real estate industry in California

whose leaders still continue to support and advance the

concept of segregation in their business and (2) that the

concentration of Negro families into certain specified

areas within California cities which is augmented, rather

than alleviated, by urban renewal projects. Ibid.

It is the unanimous view of the Committee that in Cali

fornia, minority housing is largely a Negro problem.

However, Oriental-American and Mexican-Ameriean also

populate ethnic areas within California cities; moreover,

there is a far greater degree of housing mobility for

Oriental and Mexican-Americans in California than exists

for Negroes. Id at 48.

This committee finally found that the Negro housing

problem is widespread. Negroes encounter discrimination

not only where houses in subdivision and in white neigh

borhoods are concerned, but also in regard to trailer

parks and motels. Ibid.

All of the authorities assess racial segregation and dis

crimination in land use as a direct and summary factor

in producing segregation and racial isolation in education.

See Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 382 P.2d

878, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606 (1963).

D. Education

All of the authorities assess racial segregation and dis

crimination in land use as a direct and summary factor in

producing segregation and racial isolation in education.

Ibid.

In Jackson, supra, the State Supreme Court found that

school zones were racially segregated on a fixed neighbor

hood basis and thereby ordered the School Board to allow

the plaintiff to transfer to another school. The court held

that:

“ So long as large numbers of Negroes live in segre

gated areas, school authorities will he confronted with

difficult problems in providing Negro children with

the kind of education they are entitled to have.”

That court further noted that:

“ The right to an equal opportunity for education and

the harmful consequences of segregation require that

school hoards take steps, insofar as reasonably feasi

ble, to alleviate racial imbalance in schools regardless

of its cause.” Id at 609-610.

School authorities were directed to consider the degree

of racial imbalance and “ define the extent to which it

affects the opportunity for education”.

Careful reading of this case provides the impetus for

school authorities to accept the responsibility for affirma

tively eradicating prolonged segregation in schools re

gardless of its cause.

Having viewed Jackson, supra, it is necessary to reflect

and determine whether prior to 1963, Blacks and other

racial minorities living in the state of California had ex

perienced prior racial prejudice that would justify pres

ent affirmative action as a remedy to segregated educa

tional systems.

Supporting the proposition of preserving racially sepa

rate schools was Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36, 17 Am. Rep.

405 (1874). Here the state Supreme Court refused to com

pel the admission of a black child to a school established

for white children because there was provided by statute

a school for colored children. The pertinent part of that

statute entitled, School Law of California, April 4, 1870

(Laws 1869-70, p. 838), provided:

17

“ Section 53. Every school, unless otherwise provided

by special law, shall be open for the admission of all

white children between five and twenty-one years of

age residing in that school district, and the Board of

Education shall have power to admit adults and chil

dren not residing in the district, whenever good rea

sons exist for such exceptions.

Section 56. The education of children of African

descent, and Indian children, shall be provided for in

separate schools. Upon the written application of at

least ten such children to any Board of Trustees, or

Board of Education, a separate school shall be estab

lished for the education of such children; and the

education of a less number may be provided for by

the Trustees, in separate schools, or in any other

manner. ’ ’

The foregoing statute evidences a history of de jure

school segregation in California.

Racial school segregation had a further legislative basis

in California, as affecting other minorities. These laws

were not declared unconstitutional until as late as the

1940’s. Mendez v. Westminister School District of Orange

County, 64 F. Supp. 554 (1946), affirmed 161 F.2d 724;

see also, A Generation Deprived: Los Angeles School De

segregation, A Report of the United States Commission

On Civil Rights, May 1977.

In another case decided at the federal level, Wong Him

v. Callahan, 119 F. 381 (1902), the constitutionality of

separate schools was affirmed. Involved was Political Code

of the State of California § 1662, which provided school

authorities the power to establish separate schools for

children of Chinese descent. The statute further provided

“ when such separate schools are established, Chinese or

Mongolian children must not be admitted into any other

schools”. The court here held that where Chinese schools

are offered the same advantages as other schools, the

operation of the law is not violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Racial segregation and discrimination in public school

education in California is largely uncorrected today. See,

A Generation Deprived: Los Angeles School Desegrega

tion, A Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, May 1977 and Fulfilling the Letter and Spirit of

the Law: Desegregation of the Nation’s Public Schools, A

Report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights,

August 1976.

In Lau v. Nichols, 414 TJ.S. 563 (1974), the court held

that the failure of the San Francisco school system to

provide English language instruction to approximately

1,800 students of Chinese ancestry, who do not speak

English, or to provide them with other adequate instruc

tional procedures, denies them a meaningful opportunity

to participate in the public educational program, and thus

violated § 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans

discrimination based “ on the ground of race, color, or

national origin”, in any program or activity receiving

Federal Financial Assistance, and implementing the reg

ulations of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare.

The San Francisco, California, school system began to

integrate in 1971 as a result of a federal court decree,

[339 F.Supp. 1315 (1971)], Lee v. Johnson, 404 TJ.S. 1215

(1971), but a report adopted by the Human Rights Com

mission of San Francisco, and submitted to the court by

respondents after oral argument, shows that, as of April,

1973, there still existed patterns of discrimination.

In Serrano v. Priest, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601 (1971), the Su

preme Court of Los Angeles County, held that public

school financing systems which rely heavily on local

property taxes and cause substantial disparities among

individual school districts in the amount of revenue avail-

19

able per pupil for the district’s educational grants, visit

invidously discriminate against the poor and violate the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The judgment was reversed and the case remanded. The

right to an education in public schools is a fundamental

interest which cannot be conditioned on wealth. But see,

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411

TT.S. 1 (1973).

In Lee v. Johnson, supra, the District Court found that

a desegregation plan offered by the School Board was

within the established legal bounds. But this Court stated:

“ Historically, California statutorily provided for the

establishment of separate schools for children of Chi

nese ancestry. That was the classic case of de jure seg

regation involved in Broum v. Board of Education, 347

TT.S. 483, relief ordered, 349 IT.S. 294. Schools once seg

regated by state action must be desegregated by state

action, at least until the force of the earlier segregation

policy has been dissipated. ‘The objective today remains

to eliminate from the public schools all vestiges of state-

imposed segregation.’ Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 TT.S. 115.’’

Applicants request for stay of District Court’s order

wTas denied on reassigning pupils of Chinese ancestry to

other San Francisco public schools. By refusing to stay, the

court, allowed the school board’s plan to desegregate.

The 1967 report of the United States Commission On

Civil Bights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools,2 found

that the impact of segregation in educational institutions

is reflected in the difference in educational achievement

scores accomplished in segregated and integrated schools.

The report further notes that blacks are greatly af

fected by racial isolation in their respective school svs-

2 See Appendix B.

terns. It creates a lasting stigma, which influences future

isolation throughout their lives.

The Commission offered the following explanation:

“ The environment of schools with a substantial ma

jority of Negro students offers serious obstacles to

learning. The schools are stigmatized as inferior in

the community. The academic performance of their

classmates is usually characterized by continuing dif-

culty. The children often have doubts about their

chances of succeeding in a predominately white so

ciety and they typically are in school with other stu

dents who have similar doubts .. .” Id. at 106.

The Commission went on to note that “ racial isolation

fosters attitudes and behavior that perpetuate isolation in

other important areas of American life”.

The 1963 Report of the United States Commission on

Civil Rights, State Policies Against Racial Imbalance, noted

the fact that California, in 1962, took a similar position like

that of most states toward affirmative action and decentral

ization of its segregated school systems.

The California State Board of Education adopted a pol

icy that segregation in the schools “ even where physical

facilities and other tangible factors are equal, inevitably

results in lawful discrimination”.

The 1963 report further noted that:

“ We fully realize that there are many social and eco

nomic forces at play which tend to facilitate de facto

racial segregation, over which no control, but in all

areas under our control or subject to our influence, the

policy of elimination of existing segregation and curb

ing any tendency toward its growth must be given

serious and thoughtful consideration by all persons

involved at all levels.

Wherever and whenever feasible, preference shall be

given to those programs which will tend toward con

formity with the view herein expressed.” Id. at 60.

21

The Board amended its original policy statement in 1962

by adopting an amendment which provided that it would

refrain from establishing specific school areas for its stu

dents to attend, because this process facilitated segregated

schools.

In Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 551 P. 2d 28, 35, 130 Cal. Eptr. 724 (1976) the

California Supreme Court emphatically clarified two fun

damental principles in the school desegregation process:

(1) the state law authorizes the local California school

boards to accept the ‘‘affirmative duty” to alleviate school

segregation, whether de facto or de jure; and (2) the prop

er role of the Court in a court-ordered desegregation proc

ess is to ensure that the school board “ initiates and im

plements ’ ’ reasonable measures to effectuate progress in

alleviating segregation and its offensive consequences. The

Court also made reference to its holding in San Francisco

Unified School District v. Johnson, 3 Cal. 3d. 937, 479

P.2d 669 (1971) in noting the serious harm inflicted on

minority children by segregated school systems and

stated: “ [I]t is the presence of racial isolation, not its legal

underpinnings, that creates unequal education”.

A Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights entitled “A Generation Deprived: Los Angeles

School Desegregation”, (May, 1977), p. 216 concluded that

today the mandate of Crawford, supra, to remedy school de

segregation and its harmful effects has not been achieved.

That Report examined the desegregation plan submitted

to Judge Egly of the Superior Court of the County of

Los Angeles on March 18, 1977, and found the plan “con

stitutionally deficient under California constitutional

standards. The plan neither eliminates nor begins to

eliminate segregated schools or the harm which has re

sulted from the segregated school system.” (Emphasis

in original)

22

In reflecting on the past history of segregated schools

in Los Angeles, the Report further states:

“ Where, as in this case, a school board has built a

record of dilatory conduct, resistance to its constitu

tional duty, and apparent bad faith, that board has

the additional burden of demonstrating its commit

ment to fulfill both the letter and spirit of the law.

The school board plan presented to the court in March

1977 gives no indication of any such commitment.” Id.

at 217.

In 1976, the Commission on Civil Rights examined the

desegregation effort of Berkeley, California in its report,

“Fulfilling the Letter and Spirit of the Law” (August,

1976) pp. 50-54. The Report cites the city of Berkeley as 0

one of the first Northern school districts to desegregate

voluntarily and commended the total community effort in

the successful implementation of the 1964 and 1968 de

segregation plans. Berkeley is currently implementing its

1972 plan for desegregation. The fact that the city of

Berkeley has had three desegregation plans within an

eight-year period, evidences the existence of segregated

schools in the past and the continued lingering effects.

The 1976 Report, in addition, makes reference to the

existence of segregated schools in Santa Barbara, Califor

nia. The result of such and by state recommendations,

the Santa Barbara School District developed and began

to implement a three phase desegregation plan in 1972.

As of the date of the Report, only two schools had been

involved in the desegregation process and only the first §

phase of the plan had been implemented.

The focal issue presented here is whether the State of

California with a system of education from the public

elementary schools through postsecondary education,

after finding past racial segregation and discrimination in

the total system, may institute affirmative action pro

grams, including the one in issue at the Davis Medical

School, to remedy the past effects of both de jure and

23

de facto racial segregation and discrimination by pro

moting and developing equal access of racial minorities to

the benefits and rewards of the California educational

system. Hefferlin and others have stated:

“ Commentators about America have noted that the

genius of our society and of our educational system

can be summarized in one word: emancipation—

emancipation from ignorance, emancipation from

limitations, emancipation from the chance restrictions

of environment and fortune. In many ways, Califor

nia as a state has exemplified this goal. Its develop

ment of its system of University, State University and

College, community college, and adult school resources

has been the envy of the nation if not the world. It

ranks among the leading states in educating its youth

and young people.”

Hefferlin, Peterson and Roelfs, Prepared for the Cali

fornia Legislature, September 1975, Postsecondary Alter

natives Meeting, California’s Educational Needs A Feasi

bility Study, First Technical Report Part One, California’s

Need For Postsecondary Alternatives.

The University of California, Davis, Medical School, is

a part of the state supported system of education in Cal

ifornia. The state of California through its legislature and

courts, found the California system of public education to

be racially and other-wise discriminatory. The state directed

its constituents to evolve plans and to work toward the

elimination of racial exclusion in the educational system by

providing for greater access to state afforded and supported

educational opportunities.

Though the record and arguments by the parties in this

case do not refer to certain public documents and reports

by the state of California and the United States Civil

Rights Commission, the California State Courts could

have taken judicial notice of these several reports, (West

Annotated California Codes, Evidence Code, § 451; Allen

24

v. Superior Court In and For San Diego County, 340 P.2d

1030, 171 C.A.2d 444 (1959) ; Thomas Kongsgaard, Judicial

Notice and the California Evidence Code (1966), and like

wise this Court may take judicial notice of these reports.

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454, 467, n.5 (1960); Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 494 n .ll (1954); 349 U.S.

294 (1955).

Ironically, John Vascancellos, Chairman, Assembly Ed

ucation Subcommittee On Postsecondary Education, Cali

fornia Legislature, The Bakke Decision, Disadvantaged

Graduate Students, Transcript and Statements, Sacra

mento, California, March 2, 1977, pp. 94-95 has observed:

“ For example, ACR 150 and 151 were passed by

us three years ago. They urged you to adopt flexible

admissions and then they indicated a state policy for

the Legislature about not enough minorities in the

schools, and asked you to address that affirmatively.

I could tell you that your counsel didn’t use that as

evidence in the case, to convince the court that there

was a compelling interest of the State Legislature.

To me, that is unconscionable, not to help use that for

your own case, and there are a dozen more that I have

written down here that leaves me utterly unconvinced

that the people who have handled the case so far rec

ognized the subtleties of the case, or have their hearts

in the right place.”

Equal Educational Opportunity In California Post

secondary Education: Part I, A Report Prepared by the

California Post-secondary Education Commission, Com

mission Report 76-6, April 1976, pp. 1-3 states:

“ I. B ackground and Summary

Equal educational opportunity for all California citi

zens has been a goal of our public institutions since

at least 1965. In the past ten years, considerable prog

ress has been made toward this goal, as minority en

rollments have approximately doubled as a percentage

of the total student body.

25

During the same period, the financial commitment to

achieving equality of educational opportunity also has

increased. The Board of Regents, for example, has

contributed $40 million from its own resources for

the University of California’s Educational Opportu

nity Program. The California State University and

Colleges will expend over $6 million in State Funds

in the current year for its Educational Opportunity

Program. The California Community Colleges have

an Extended Opportunity Programs and Services

program (EOPS) of equivalent size. Despite these

significant efforts, however, equal educational oppor

tunity remains a goal and not a reality in California

post-secondary education.

Recognizing the need for increased efforts by public

institutions to overcome the underrepresentation of

women, ethnic minorities, and low-income persons in

their student bodies, the Legislature adopted Assem

bly Concurrent Resolution 151 (1974). This resolution

requested the Regents of the University of California,

the Trustees of the California State University and

Colleges, and the Governors of the California Com

munity Colleges:

To prepare a plan that will provide for address

ing and overcoming, by 1980, ethnic, economic,

and sexual underrepresentation in the make-up of

the student bodies of institutions of public higher

education as compared to the general ethnic, eco

nomic, and sexual composition of recent Califor

nia high school graduates.

These plans were to be submitted to the California

Postsecondary Education Commission by July 1, 1975,

and the Commission in turn was to ‘integrate and

transmit the plans to the Legislature with its com

ments ’.

In addition, ACR 151 requested the three public seg

ments to report annually to the Commission on their

progress toward the 1980 goal, with specific discus

sion of obstacles to the implementation of a statewide

plan. These reports are to be integrated and trans

mitted to the Legislature by the Commission, together

with its evaluations and recommendations.

The Legislature also identified four methods for re

sponding to the problem of underrepresentation:

(a) affirmative efforts to search out and contact

qualified students;

(b) experimentation to discover alternative means

of evaluating student potential;

(c) augmented student financial assistance pro

grams; and

(d) improve counseling for disadvantaged stu

dents.

An analysis of the segmental reports submitted to the

Commission m response to ACR 151 leads to the fol

lowing conclusions:

The reports are not adequate in meeting the Leg

islative request that the segment develop a co

herent plan to address and overcome the problem

of underrepresentation. While the reports vary

considerably in the degree of specific and com-

prehensive analysis presented, none reveals a

thoroughly developed, detailed plan for student

affirmative action.

Compared to the composition of recent California

high school graduates, Black and Spanish-sur-

named students are under-represented in public

postsecondary education. Moreover, during the

past two years, the degree of underrepresentation

apparently has increased rather than decreased

While women are also under-represented, this oc

curs more frequently in the graduate programs.

While increased financial assistance through the

several student aid programs is probably needed

greater emphasis must be placed on (1) recruit

ment programs to increase the eligibility pool of

the underrepresented groups, and (2) on student

support services to promote successful educa

tional experiences for those who gain access to

public postsecondary education.

Efforts by the segments to achieve the goal of

equal educational opportunity would be enhanced

27

by a clearer long-range commitment on the part

of the Legislature and the Governor to support

a coherent financial program requisite for an ef

fective student affirmative action plan. While ACE

151 states ‘it is the intent of the Legislature to

commit the resources to implement this policy.’

State government as a whole has done demon

strated this intent.”

Given these conclusions, it is clear that the institutions

of public postsecondary education are only in the begin

ning stage of developing a student affirmative action pro

gram. Accordingly, this Eeport should be considered the

first of two dealing with equal educational opportunity in

post secondary education. This First Eeport describes the

current situation in the student affirmative action pro

grams of the public segments and presents initial recom

mendations and guidelines for the development of a com

prehensive statewide plan for student affirmative action.

The Second Eeport, to be developed through cooperative

efforts by the Commission and the three public segments,

will present this statewide plan and will include a de

tailed discussion of the activities and costs of current and

proposed programs. The Commission will play a leadership

role in developing a statewide plan coordinating segmental

activities. The Second Eeport was submitted to the Legis

lature in January 1977.

The significance of the college degree is strongly felt and

adamantly expressed by most Californians; so much so, that

its attainment is believed to provide an upward social and

economic mobility resulting in personal growth and cogni

tive development. This persuasion is now being challenged

due to the changing of time, the development of numerous

critiques of higher education, and the growing number of

unemployed college graduates. Notwithstanding this some

what recent attack, college attendance yields very real, per

sonal and social benefits for many, particularly minorities

28

and poor persons. However, college is not an option open

for many high school graduates. In other words, it is need

less to say that access to college, for many persons, remains

unequal. “ Nationally, if your family’s annual income is

$15,000 you are four times more likely to attend college

than if your family’s income is $3,000. If you are very

poor and black, your chances of entering college are one-

seventh that of students from high income white families.

Underrepresentation of ethnic minorities continues, par

ticularly at four-colleges and universities.” Unequal Ac

cess to College, Post Secondary Opportunities and Choices

of High School Graduates, Staff Report, Assembly Per

manent Subcommittee on Post Secondary Education, Cali

fornia Legislature 1, 1975.

The Legislature, in adopting Assembly Concurrent

Resolution 151 (1974), took cognizance of the fact that addi

tional efforts by colleges and universities would be neces

sary to overcome the large degree of underrepresentation of

ethnic minorities and poor, alike.

In effect, ACR 151 sets forth the requirement that the

three public segments of higher education, i.e., the com

munity colleges, the State University and Colleges, and

the University of California, must develop certain stra

tegy in order to alleviate the present situation of under

representation of minority students and students from

low income families by 1980.

In analyzing the data considered, the findings are as

follows:

“ Substantial inequality of post-high school opportuni

ties exists between graduates of high schools serving

low income areas and graduates of high schools serv

ing high income areas. The rates of eligibility to enter

the University of California and the State University

and Colleges are three times greater for graduates

of high income schools than for graduates of low in

come schools (Table_9 and 12). IIC and CSUC eligi

bility rates for Spanish surname and black graduates

29

are one-third the eligibility rates for whites (Tables 10

and 13). (This finding is compounded by dropout rates

in sampled low income high schools averaging 39 per

cent, compared to 13 percent in high income schools—

Table 7.)

Actual post-high school choices of graduates reveal

similar inequalities. Graduates of high schools in

high income areas are four times as likely to enter

the University of California and twice as likely to

attend the State University and Colleges as are low

income graduates (Table 15). Rates of entrance to

community colleges and independent colleges and uni

versities are very similar, regardless of differences in

family incomes: Only two and four percent of all

Spanish surname and black graduates, respectively,

entered UC, compared to an entrance rate of 14 per

cent for white graduates (Table 16).

Specific inequities emerge after combining informa

tion about opportunities and choices: Significantly

greater numbers of UC' and CSUC—eligible low in

come graduates are not entering college, than eligible

high income graduates. And many high achieving low

income graduates are ineligible to attend UC and/or

CSUC due only to minor course or scholarship defi-

ciences. The substantial number of TJC and/or CSUC

eligible, low income graduates entering community

colleges provides a potentially larger number of stu

dents eligible to later transfer to UC and/or CSUC

(Tables 17 through 20).

Given unmet financial need remains substantial, in

creasing only student aid appropriations will not

significantly increase the numbers of low income and

minority college students. Governmental and institu

tional strategies for overcoming access inequalities

must also focus on:

—improving instructional programs in low income

high schools to increase achievement levels;

—improving information available to high school

students about postsecondary opportunities and

student aid;

—increasing flexibility of admission requirements;

30

—expan [ding] student support services (e.g., tutor

ing and counseling) for low income and minority

students who enter college.. . .

Four times as many graduates of high income

schools actually enter the University of California as

graduates from low income schools. Seventeen per

cent of high income graduates choose to enter the

State University and Colleges, compared to only eight

percent of graduates from low income schools. While

just under one-half of graduates from high income

schools enter a four-year college, only 21 percent of

low income graduates do so. There seems to he sur

prising equality of opportunity for graduates choos