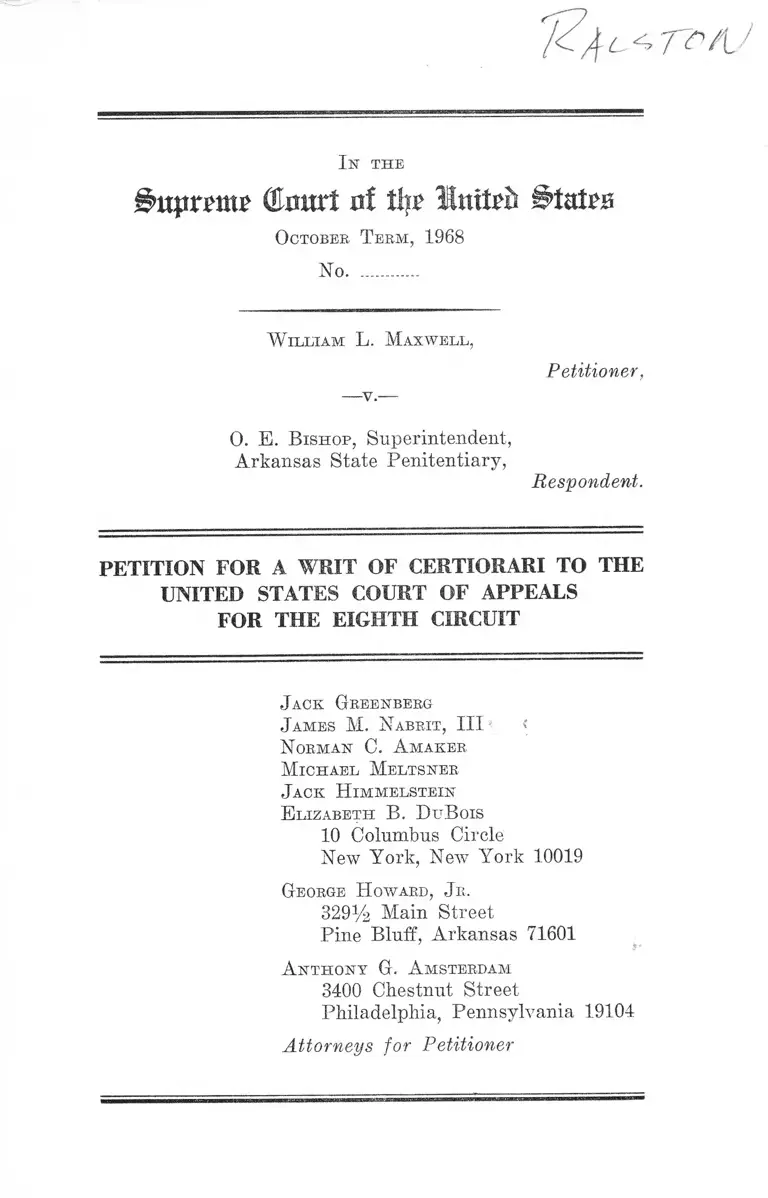

Maxwell v. Bishop Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Bishop Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, 1968. bfedde50-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d6b3f564-b545-4ff5-89c8-976c64bb8b13/maxwell-v-bishop-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-eighth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IZa

In th e

(Emtrt 0! tty llnitsii States

O ctober T ee m , 1968

No..............

W illiam L. M axw ell ,

Petitioner,

—v.—

0. E. B ishop , Superintendent,

Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J am es M . N abr.it , III '

N orman C. A m aker

M ich ael M eltsner

J ack H im m elstein

E lizabeth B. DttB ois

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

George H oward, J r .

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 716017 $■

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions Below .......................-...................... 1

Jurisdiction .........~.............. -.................. —-........ -.............. 2

Questions Presented .......................- ............. ...... —- ....... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 4

Statement ....... ................ -.......................................... -......... 4

A. The History of the Case ..................... - ..... — 4

1. Trial and Appeal ...................................-...... 4

2. First Federal Habeas Corpus Proceeding .... 5

3. Second Federal Habeas Corpus Proceeding 7

B. The District Court Proceedings Below ........... 9

1. Identification of the Cases to Be Studied .... 15

2. Data Concerning the Critical Variables

(Race and Sentence) and Statistical Analy

sis of the Relationship Between Them ....... 17

3. Data Concerning “ Control” Variables ....... 19

4. Results and Conclusions ............................ - 22

C. The Opinions Below .......... ...... .......... ..... — 28

1. The Issue of Racial Discrimination in Capi

tal Sentencing for Rape ...... ........... —-.....— 28

2. The Issues of Unfettered Jury Discretion

and of Simultaneous Trial on Guilt and

Punishment ............................................ - 33

PAGE

11

3. The Issue of Racially Discriminatory Jury

PAGE

Selection Procedures .............. ........................ 34

Reasons for Granting the W r it ........................................ 35

I. Petitioner’s Uncontradicted Proof of Racially

Discriminatory Imposition of the Death Penalty

on Negroes Convicted of Raping White Women,

Together with the Needless Encouragement of

Discriminatory Sentencing Occasioned by the

Arkansas Procedure of Simultaneously Sub

mitting the Issues of Guilt and Punishment to

a Jury Without Standards to Guide its Dis

cretion in Fixing Punishment, Requires Re

versal of the Judgment Below ...........-.............. 35

Introduction ....................................................... ...... 35

A. The Courts Below Erred in Holding That

Petitioner’s Proof of the Racially Discrim

inatory Death-Sentencing Practices of Ar

kansas Juries in Rape Cases Did Not Entitle

Him to Relief From the Death Sentence .... 45

B. The Courts Below Erred in Holding That Ar

kansas’ Procedure of Allowing Capital Juries

Absolute, Uncontrolled and Arbitrary Dis

cretion to Choose Between Punishments of

Life or Death, Does Not Violate the Rule of

Law Basic to the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment ....... ..... .............. ...... 58

C. The Courts Below Erred in Rejecting Peti

tioner’s Constitutional Attacks Upon the

Arkansas Single-Verdict Procedure for the

Trial of Capital Cases ................. ................. 65

I l l

II. The Courts Below Erred in Rejecting Peti

tioner’s Attack Upon the Arkansas Scheme of

Juror Selection, Which Provides the Oppor

tunity for Racial Discrimination Proscribed by

PAGE

Whitus v. Georgia .................................................. 75

Conclusion ..................... .................................-......................... 79

A ppendix A—

Memorandum Opinion of the District Court ....... la

Order of the District Court ............... ................ -..... 23a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ................. ......... 24a

Judgment of the Court of Appeals .... .................. 56a

A ppendix B —

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved 57a

T able of C ases

Adderly v. Wainwright, M.D. Fla., No. 67-298-Civ.-J—. 41

Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1962),

aff’d, 371 U.S. 37 (1962) ................................. ....... . 56

Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 206 (1968) ....................... 78

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) .....................-46, 78

Andrews v. United States, 373 U.S. 334 (1963) ..........— 68

Application of Anderson, Cal.S.C., Crim. No. 11572 .... 41

Application of Saterfield, Cal.S.C., Crim. No. 11573 .... 41

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ......... ................. 77

Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co., 259 U.S. 20 (1922) ..... 48

Behrens v. United States, 312 F.2d 223 (7th Cir. 1962),

aff’d, 375 U.S. 162 (1963) .................... ............... ......68,69

IV

Bostwick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1967) ......... 78

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966) ................... 48

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..... 46

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936) ...... .............. 42

Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123 (1968) ........... 71

Bumper v. North Carolina, O.T. 1967, No. 1016 ..... 41

Burgett v. Texas, 389 U.S. 109 (1967) .... 72

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961) ..................................... ..................... .................... 58

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 (1882) ........... ...... ........ 47

Chambers v. Hendersonville Board of Education, 364

F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966) ........... ............. ........ .............. 51

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 247 U.S. 445 (1927) ............... 59

Cobb v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 12 (1967) ...................... 78

Coleman v. United States, 334 F.2d 558 (D.C. Cir.

1964) ........................ ................... ..................................... 69

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385

(1926) ....... ................... ...... ........... ...... ......... ........ ........ 59

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .......................... ..... 46

Couch v. United States, 335 F.2d 519 (D.C. Cir. 1956) 69

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ............................ 60

Cypress v. Newport News Hospital Association, 375

F.2d 648 (4th Cir. 1967) ................................ ............... 51

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) ............... 60

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) .................... 50

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 (1966) .................. .... 58

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) .................................... 59, 73

Ferguson v. Georgia, 365 U.S. 570 (1961) ....................... 69

Forcella v. New Jersey, O.T. 1968, Misc. No. 947 ......... 41

PAGE

V

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 (1953) ....-.... ........ 46

Frady v. United States, 348 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1965).... 74

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965) ....... ......... 59

Gadsden v. United States, 223 F.2d 627 (D.C. Cir. 1955) 69

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399 (1966) ....33, 40, 61, 62

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ................ 51,56

Green v. United States, 365 U.S. 301 (1961) ................ 69

Green v. United States, 313 F.2d 6 (1st Cir. 1963), cert.

denied, 372 U.S. 951 (1963) ....................................... . 68

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965) ....................... 69

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) ...... ............. 63

Hamilton v. Alabma, 376 U.S. 650 (1964) ....... ........... 46

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443 (1965) ...................... . 59

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) ..................... 47, 50

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937) .......... ........ „ ..... 59

Higgins v. Peters, U.S. Dist. Ct. No. LR-68-C-176, E.D.

Ark., Sept. 25, 1968 ................................ ..... ........... ..... 36

Hill v. United States, 368 U.S. 424 (1962) ___ _______68, 69

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961) ....... .......... .......... — 63

PAGE

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964) ............................ 71

Jenkins v. United States, 249 F.2d 105 (D.C. Cir. 1957) 69

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4th Cir. 1966) ...... . 51

Johnson v. Virginia, O.T. 1968, Misc. No. 307 ....... ....... 41

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 268 (1939) .............................. 56

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966) .......42,43

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ....... 60,63

Lovely v. United States, 169 F.2d 386 (4th Cir. 1948) 70

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) .....•.......................... 36

V I

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964) ................................ 69

Marshall v. United States, 360 U.S. 310 (1959) ....... ..... 70

Matter of Sims and Abrams, 389 F.2d 148 (5th Cir.

1967) ....... ........ .........................................-.............. -..... 13,44

Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967) .................... .... 9

Maxwell v. State, 236 Ark. 694, 370 S.W.2d 113

(1963) ............... ................................................... 2,5,15,48

Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F. Supp. 205 (E.D. Ark.

1964), aff’d, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), cert, denied,

382 U.S. 944 (1965) ...........................................2, 6, 7, 48, 75

McCants v. Alabama, O.T. 1968, Misc. No. 937 ............. 41

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) .............. . 50

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) ..... ...... ................ 60,68

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 103 (1935) ............ .......... 42

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923) ........................... 42

Moorer v. South Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (4th Cir.

1966) ................................. ..............................................13,44

PAGE

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958) ................... 46

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ........ .......... 59

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881) ........................ 47

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (1951) ...............46,63

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) ..................... ..50, 56

Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928) ........... 42

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ..........— ..... 51

People v. Hines, 390 P.2d 398, 37 Cal.Rptr. 622 (1964) 69

People v. Love, 53 Cal.2d 843, 350 P.2d 705 (1960) ...... 63

Pope v. United States, 372 F.2d 710 (8th Cir. 1967) ....33-34

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) ............................ 50

Rochin v. California, 342 U.S. 165 (1952) ..................... 42

vii

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963) ................ 8

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ....................... 46

Shepherd v. Floi’ida, 341 U.S. 50 (1951) ----------- ------- 42

Simmons v. United States, 390 U.S. 377 (1968) ------ 70,72

Sims v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 998 (1966) ............... 8,9,35

Sims v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 404 (1967) .....................8,35,78

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 538 (1967) ........ 8,35,72

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942) .....-63, 65, 68, 72

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 (1931) ........ ............... . 59

Specht v. Patterson, 386 U.S. 605 (1967) .... ........ 61,68,72

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554 (1967) ____33, 34, 71, 72, 73

Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U.S. 410 (1968) ...................... 78

Tigner v. Texas, 310 U.S. 141 (1940) ........................... 62

Townsend v. Burke, 334 U.S. 736 (1948) ............. — .... 73

United States v. Beno, 324 F.2d 582 (2d Cir. 1963) — 70

United States v. Curry, 358 F.2d 904 (2d Cir. 1965) .... 74

United States v. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir. 1964) .... 51

United States v. Jackson, 390 U.S. 570 (1968) .......... 69, 73

United States v. Johnson, 315 F.2d 714 (2d Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 375 U.S. 971 (1964) __________________ 68

United States v. National Dairy Prods. Corp., 372 U.S.

29 (1963) ...................... ............ .................. ............... . 62

United States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F.2d 311

(3d Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 844 (1963) ..... 71

United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Banmiller, 310 F.2d

720 (3d Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 828

(1963) ........................................ ............ .......... ............. 70-71

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ------ 46

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) .....73, 78

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) .......4,8,34,56,75,

76, 77, 78, 79

PAGE

V l l l

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 (1953) ................... 78

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 (1949) ................... 67

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 (1959) ....... ......... . 67

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948) ................ . 59

Witherspoon v. Illinois, O.T. 1967, No. 1015................... 41

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) .......39,60,62,

67, 74

Yiek Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) .......46, 56, 57, 63

S tatutes

Federal:

Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866, eh. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27 45

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18,

16 Stat. 140, 144 ............................... ................... .......... 45

Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875), 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964) ........... 45

10 U.S.C. §920 (1964) ...... .................... ........................... 37

18 U.S.C. §2031 (1964) .................................................... 37

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................. 2

State:

Ala. Code §§14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (Recomp. Vol. 1958) 36

Ark. Stat. Ann., §3-118 (1956) ......... .......... ............. ........ 4

Ark. Stat. Ann., §3-227 (1956) ........... ......... ................. . . 4

Ark. Stat. Ann., §39-208 (1962) .................... ................. . 4

Ark. Stat. Ann., §41-3403 (1962) ........ ..... ............. .......4,36

Ark. Stat. Ann., §§41-3405, 3411 ---- ------------------- ------ 36

Ark. Stat. Ann., §43-2153 (1962) ................................ 4, 5, 36

D.C. Code Ann. §22-2801 (1961) ............................ ......... 37

Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 (1964 Cum. Supp.)

PAGE

36

IX

Ga. Code Ann. §§26-1302, 26-1304 (1963 Cum. Supp.).~. 36

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963) ......................... 36

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. §14:42 (1950) _______________ 36

Md. Ann. Code §§27-463, 27-12 (1967 Cum. Supp.) ....... 36

Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (Recomp. Vol. 1956) ................ 36

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.260 (.1953) ................. . 36

Nev. Rev. Stat. §§200.363, 200.400 (1967) ..................... 36, 63

N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (Recomp. Vol. 1953) ............. ..... 36

Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 21, §§1111, 1114, 1115 (1958) ____ 36

S.C. Code Ann. §§16-72, 16-18 (1962) .......................... 36

Tenn. Code Ann. §§39-3702, 39-3703, 39-3704, 39-3706

(1955) ................. ............ ....... ............... .......................... 36

Tex. Pen. Code Ann., arts. 1183, 1189 (1961) ............... 37

Va. Code Ann. §§18.1-44, 18.1-16 (Repl. Vol. 1960) ..... 37

Oth er A uthorities

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code §210.6

(P.O.D. May 4, 1962) ................................ ................. 64, 71

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Tent.

Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959) .......... ........ ............. - ....... 67

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 475 (1/29/1866);

1759 (4/4/1866) .................................................... -....... 47

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1758 (4/4/1866) .... 47

9 Crime and Delinquency 225 (1963) ---- -------------- ------ 39

Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate

the Bill of Rights, 2 Stan. L. Rev. 5 (1949) ............. 45

PAGE

X

PAGE

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory to the Jury Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv.

L. Bev. 338 (1966) ........ ............................... ................ . 56

Handler, Background Evidence in Murder Cases, 51 J.

Grim. L., Crim. & Pol. Sci. 317 (1960) ....................... 67

H. L. A. Hart, Murder and the Principles of Punish

ment: England and the United States, 52 Nw. U.L.

Rev. 433 (1957) ____________ ____ ___ ______________ 67

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment,

284 A nn als 8 (1952) .......... ..... ..... ..................... .......... 39

H ouse oe Com m ons S elect C om m ittee on Capital

P u n is h m e n t , R eport (H.M.S.O. 1930) ..................... 67

Knowlton, Problems of Jury Discretion in Capital

Cases, 101 IT. Pa. L. Rev. 1099 (1953) ____________ 67

Letter of Deputy Attorney General Ramsey Clark to

the Honorable John L. McMillan, Chairman, House

Committee on the District of Columbia, July 23,1965,

reported in New York Times, July 24, 1965 ............ 40

Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations, 1963

S uprem e C ourt R eview 101 _______ ___ ________ _____59-60

M a t t ic k , T he U n exam ined D eath (1966) ...... ............... 39

N ew Y ork S tate T em porary C ommission on R evision

op th e P en al L aw and Cr im in al Code I nterim R e

port (Leg. Doc. 1963, No. 8) (February 1, 1963) ..... 67

New York Times Magazine, Sunday, April 2, 1967 ....... 40

Note, 109 U. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) .................. ..... ............. 60

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime, 77

Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964) ...... ...... ............ ..... .......... 64,65

Polls, International Review on Public Opinions, Yol.

II, No. 3 (1967) 39

PAGE

R oyal C ommission on Capital P u n is h m e n t , 1949-1953,

R eport (H.M.S.O. 1953) (Cmd. No. 8932) ............... 67

S ellin , T he D eath P en alty (1959), published as an

appendix to American Law Institute, Model Penal

Code, Tent. Draft No. 9 (May 8, 1959) ....................... 39

tenBroek. Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, 39 Calif. L. Rev. 171 (1951) .... 45

U nited N ations, D epartm ent oe E conomic and S ocial

A ffairs , Capital P u n is h m e n t (ST/SOA/SD/9-10)

(1968) ............................................................................. 37,39

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Pris

ons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 32; Execu

tions, 1962 (April 1963) .... ....................... ............. .....22, 37

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Pris

ons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 42; Execu

tions, 1930-1967 (June 1968) ............. ................. 22,39,40

Wiehofen, The Urge to Punish (1956) ........................... 40

In t h e

(tart nf Imtei*

October T e rm , 1968

No..............

W illiam L. M axw ell ,

Petitioner,

— v . —

0. E. B ishop , Superintendent,

Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit entered on July 11, 1968.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas denying petitioner’s appli

cation for a writ of habeas corpus is reported at 257 F.

Supp. 710, and is set out in Appendix A hereto, pp. la-22a

infra. The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit affirming the denial of petitioner’s

application is not yet reported and is set out in Appendix

A hereto, pp. 24a-55a infra.

2

Opinions at earlier stages of this proceeding are re

ported. The opinion of the Supreme Court of Arkansas

affirming petitioner’s conviction for the crime of rape and

sentence of death is found sub nom. Maxwell v. State, 236

Ark. 694, 370 S.W. 2d 113 (1963). Opinions on disposition

of an earlier application for habeas corpus are found

sub nom,. Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F. Supp. 205 (E. D.

Ark. 1964), aff’d, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), cert, denied,

382 U.S. 944 (1965).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit was entered July 11, 1968. Juris

diction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether petitioner’s proof that Arkansas juries have

followed a systematic practice of racial discrimination in

sentencing men to death for the crime of rape establishes

a prima facie case which, in the absence of any rebuttal

or explanation by the State, requires the constitutional

invalidation of the death sentence imposed upon petitioner,

a Negro convicted of rape of a white woman! This ques

tion is framed by a record of uneontradieted expert sta

tistical testimony based upon an exhaustive study of the

patterns of capital sentencing by Arkansas juries in rape

cases. It is presented against the background of Arkansas’

procedures for capital sentencing which leave unfettered

and undirected discretion to the jury to bring in a verdict

of death or life, and which deny the defendant a separate

hearing for the presentation of evidence upon which ra

tional sentencing choice may be based. The question sub

sumes the issues:

3

(a) Whether the courts below correctly held that the

principles developed by this Court in several contexts rela

tive to a prima facie showing of racial discrimination are

inapplicable to proof of racial discrimination by juries in

capital sentencing ?

(b) Whether the showing by petitioner below did not

make out a prima facie case which, under proper consti

tutional standards for the evaluation of proof, compelled

a finding of racial discrimination in the absence of any

rebuttal evidence?

(c) Whether the courts below correctly held that peti

tioner could not prevail upon an accepted showing of state

wide discrimination in capital sentencing for rape, because

he did not in addition prove (i) a similar pattern of dis

crimination in the particular county in which he was tried

(where the cases were too few to establish a pattern), or

(ii) that the particular jury which sentenced him was

racially motivated?

(d) Whether the Court of Appeals correctly held that

petitioner could not prevail as a matter of law on his

challenge to his death sentence as discriminatorily im

posed, because the consequence of his argument would

temporarily leave only white defendants subject to the

death penalty under present Arkansas procedures?

2. Whether Arkansas’ practice of permitting the trial

jury absolute discretion, uncontrolled by standards or di

rections of any kind, to impose the death penalty violates

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

3. Whether Arkansas’ single-verdict procedure, which

requires the jury to determine guilt and punishment simul

taneously and a defendant to choose between presenting

mitigating evidence on the punishment issue or maintain-

4

4. Whether the Arkansas scheme of juror selection em

ployed at petitioner’s trial provided the opportunity for

racial discrimination proscribed by Whitus v. Georgia, 385

U.S. 545 (1967)?

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

2. The case also involves Arkansas Statutes Annotated

§§3-118, 3-227, 39-208, 41-3403, 43-2153. The text of these

provisions is set forth in Appendix B hereto, pp. 57a-60a,

infra.

mg his privilege against self-incrimination on the guilt

issue, violates the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments?

Statement

A. The History of the Case.

1. Trial and Appeal.

Petitioner, William L. Maxwell, a Negro, was tried in

the Circuit Court of Garland County, Arkansas, in 1962

for the rape of a 35 year old, unmarried white woman.

Pursuant to Arkansas statutes and practice, the issues of

guilt and punishment were simultaneously tried and sub

mitted to the jury, which was given no instructions limit

ing or directing its absolute discretion, in the event of

conviction, to impose a life sentence (by returning the

“verdict of life imprisonment” authorized by Ark. Stat.

Ann. §43-2153 (1964 Repl. vol.), App. B., p. 60a infra),

or a death sentence (which follows as a matter of course

5

The jury convicted petitioner of rape and failed to

return a life verdict, whereupon he was sentenced to

death. His motion for a declaration of the unconstitu

tionality of §43-2153, on the grounds that Arkansas juries

had followed a pattern of racial discrimination in the

application of the death penalty for rape, was overruled

by the trial court. This contention was raised, together

with numerous other federal and state-law claims, on his

appeal to the Supreme Court of Arkansas. That court

rejected the contention on the merits, taking the view that

petitioner’s then available evidence of racial discrimina

tion—Arkansas prison statistics showing 19 executions of

Negroes for rape and one execution of a white for rape

between 1913 and 1960—failed factually to support the

claim that Arkansas juries were acting discriminatorily,

at least in the absence of “ evidence . . . even remotely

suggesting that the ratio of violent crimes by Negroes

and whites was different from the ratio of the executions.”

Maxwell v. State, 236 Ark. 694, 701, 370 S.W.2d 113, 117

(1963). Finding petitioner’s other claims without merit,

the court affirmed his conviction and death sentence. No

petition for certiorari was filed here seeking review of that

decision.

2. First Federal Habeas Corpus Proceeding.

In 1964, petitioner filed an application for federal habeas

corpus, raising among other contentions the claims (a)

that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment was violated by his death sentence pursuant to a

practice of systematic racial discrimination in the exer

cise of capital sentencing discretion by Arkansas juries;

(b) that the Due Process Clause and its incorporated

from the jury’s failure to return a verdict of life imprison

ment).

6

prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment were vio

lated by the imposition of the death penalty for rape;

and (c) that the Equal Protection Clause was violated by

the systematic exclusion of Negroes from his trial jury,

in particular because the jurors had been selected under

Arkansas statutory procedures by reference to poll tax

books in which racial identifications were required by law.

The district court found that no sufficient showing of racial

discrimination in capital sentencing had been made and,

rejecting petitioner’s other federal contentions, denied the

writ. Maxwell v. Stephens, 229 F. Supp. 205 (E. D. Ark.

1964). The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

affirmed after considering and rejecting petitioner’s avail

able evidence in support of his claim of racial discrimina

tion in capital sentencing. This included both the statis

tics which he had previously presented relating to the

number of Negro and white executions in Arkansas for

the crime of rape since 1913, and sentencing statistics cov

ering Garland, Pulaski and Jefferson Counties, Arkansas

from January 1, 1954, to the date of petitioner’s habeas

corpus hearing in 1964. Petitioner had attempted to dem

onstrate on the basis of these statistics, by reference to the

race of the defendants who had been sentenced to death and

of the victims of the crimes of which they had been con

victed, that there was a state-wide pattern of discriminatory

capital sentencing for Negroes; but the court found, on that

record, that petitioner’s “ statistical argument is not at all

persuasive” , 348 F.2d 325, 330 (8th Cir. 1965).1

1 Petitioner’s then available evidence in support of his claim of

racial discrimination was summarized in the court’s opinion as

set forth below:

“ The evidence as to the state at large, showed that, in the

50 years since 1913, 21 men have been executed for the crime

of rape; that 19 of these were Negroes and two were white;

that the victims of the 19 convicted Negroes were white fe

males; and that the victims of the two convicted whites were

7

3. Second Federal Habeas Corpus Proceeding.

July 21, 1966 the present application for federal habeas

corpus was filed, alleging that new evidence had become

available since the disposition of petitioner’s prior habeas

appeal with respect to the claim of systematic racial dis

crimination in the exercise of capital sentencing discre

tion by Arkansas juries. Petitioner also raised two re

lated claims not previously made: (1) That Arkansas’

“ single-verdict” procedure for capital sentencing, under

which the issues of guilt and punishment are simultane

ously tried and submitted to the trial jury, is federally

also white females. As to Garland County, for the decade

beginning January 1, 1954, Maxwell’s evidence was to the

effect that seven whites were charged with rape (two of white

women and the race of the. other victims not disclosed), with

four whites not prosecuted and three sentenced on reduced

charges; that three Negroes were charged with rape, with one

of a Negro woman not prosecuted and another of a Negro

receiving a reduced sentence, and the third, the present defen

dant, receiving the death penalty. With respect to Pulaski

County for the same decade, there were 11 whites (two twice)

and 10 Negroes charged, with the race of the victim of two

whites and one Negro not disclosed. Three whites received a

life sentence. One white was acquitted of rape of a Negro

woman. One received a sentence on a reduced charge, two

were dismissed, two cases remained pending, one was not

prosecuted, and the last was executed on a conviction of

murder. Of the Negroes, three, with white victims and two

with Negro victims received life. One case was dismissed, one

was not arrested, two with Negro victims were sentenced on

reduced charges, and one, Bailey, with a white victim, was

sentenced to death. In Jefferson County eight Negroes were

charged, with the cases against five dismissed, another dis

missed when convicted on a murder charge, and two receiving

sentences on reduced charges. Sixteen whites were charged.

One was charged three times with respect to Negro victims

and as to two of these charges received five years suspended

on a guilty plea. Two others received three year sentences.

One is pending, one was executed, and the rest were dismissed.

The race of four defendants was not disclosed; three of these

cases were dismissed and one is pending.” 348 F.2d at 330

(footnotes omitted).

unconstitutional because it deprives the defendant of a

fair trial on either issue and compels his election between

his privilege against self-incrimination and his rights of

allocution and to present evidence necessary for rational

sentencing choice; (2) that Arkansas’ practice of allowing

juries absolute, uncontrolled, standardless discretion to

sentence to life or death affronts the fundamental rule of

law expressed by the Due Process Clause. Petitioner also

renewed his claim of unconstitutional jury selection in

light of this Court’s grant of certiorari the previous month

in Sims v. Georgia, 384 U.S. 998 (1966).2

Following a full evidentiary hearing of the new evidence

proffered, the district court rejected all of petitioner’s

claims in an opinion filed on August 26, 1966, and re

ported at 257 F. Supp. 710. The court, in the exercise

of its discretion under Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1

(1963), entertained those claims dealing with Arkansas’

death-sentencing procedures and with the exercise by Ar

kansas juries of sentencing discretion in the imposition of

the death penalty. However, the court declined to review

again the claim of racial discrimination in jury selection,

stating at 257 F. Supp. 713, App. A, p. 5a infra, that:

“ [tjliis court sees no occasion to reexamine the question and

is not persuaded to do so by the action of the Supreme

2 This Court granted certiorari to review the following question,

among others:

“ Is a conviction constitutional where: (a) local practice pur

suant to state statute requires racially segregated tax books

and county jurors are selected from such books;”

Though this question was briefed and argued in the Sims case,

the Court initially decided the case on a different ground, Sims v.

Georgia, 385 U.S. 538 (1967). It dealt with the question in another

ease decided at the same time, Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967), discussed more fully infra, Argument II at pp. 75-79; and

in a later stage of the Sims ease, the Court held that Sims’ juries

were unconstitutionally selected, citing Whitus. Sims v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 404 (1967).

9

The district court refused to issue a certificate of prob

able cause for appeal and also refused to stay petitioner’s

execution, then scheduled for September 2,1966. On August

30, 1966, Judge Matthes of the Eighth Circuit Court of

Appeals refused applications for a certificate and for

stay of the death sentence. On September 1, 1966, Mr.

Justice White granted a stay of petitioner’s execution,

and on January 23, 1967, this Court reversed Judge

Matthes and ordered that a certificate of probable cause

be granted. Maxwell v. Bishop, 385 U.S. 650 (1967).

The appeal proceeded in the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. There petitioner pressed

his constitutional claims relating to the discriminatory

exercise by Arkansas juries of capital sentencing discre

tion, to the facial invalidity of the Arkansas capital sen

tencing procedures, and to racial discrimination in jury

selection. All of petitioner’s claims were rejected by the

Court of Appeals in an opinion filed July 11, 1968.

B. The District Court Proceedings Below.

Petitioner’s second federal habeas corpus petition, giv

ing rise to the proceedings now sought to be reviewed, al

leged that new evidence had become available with respect

to his claim of racial discrimination in capital sentencing.

It averred, specifically, that a systematic study of Arkan

sas rape convictions during a twenty-year period had been:

“ conducted in the summer of 1965, as part of a study

of the application of the death penalty for rape in

eleven southern states. This comprehensive study re

quired the work of 28 law students throughout the

summer, the expenditure of more than $35,000 and

Court in recently granting certiorari in the case of Sims v.

Georgia, 384 TJ.S. 998. . . . ”

10

numerous hours of consultative time by expert crimi

nal lawyers, criminologists and statisticians. Peti

tioner, who is an indigent, could not have himself at

any time during the prior proceedings in his cause

conducted such a study.” (Petition, para. 7(b), quoted

by the Court of Appeals, App. A, p. 29a infra. [The

study is described in detail at pp. 13-27 infra.])

At a pre-trial conference, the district court was advised

that petitioner intended to present at an evidentiary hear

ing the results of this comprehensive study. Its pre-trial

conference order reflected that petitioner’s evidence would

consist in part of “ the testimony of Dr. Marvin E. W olf

gang, a criminologist and statistician on the faculty of

the University of Pennsylvania, and . . . certain studies

and a report made by Professor Wolfgang,” which in

turn were based upon “ [b]asic data . . . gathered by law

student field workers from various sources and . . . re

corded on individual case schedules.” Accordingly, the

order provided for procedures to facilitate the establish

ment of “ the validity and accuracy of the individual case

schedules” 3:

3 The “ individual case schedules” referred to are the completed

forms, for each case of conviction of rape, of the printed schedule

captioned “ Capital Punishment Survey” admitted as Petitioner’s

Exhibit, P-2 (TV. 57). [Tr. — references in this petition are to the

original transcript of the district court proceedings.] The use of

this printed schedule in the process of data-gathering was ex

plained by Dr. Wolfgang at Tr. 22-25. Instructions given the

field researchers in use of the schedule are included in the record

as an exhibit, Petitioner’s Exhibit P-3 (Tr. 25-27, 57), but, in

view of the respondent’s concession that the facts gathered by

the researchers were accurate, see text infra, no effort was made

in the testimony to demonstrate the steps taken in gathering the

data to assure reliability. See Tr. 25-27. Also, in light of the

court’s pre-trial conference order, text, immediately infra, the

completed “ individual case schedules” were not introduced in

evidence.

1 1

“It was agreed that counsel for Maxwell will make

those schedules available for the inspection of coun

sel for Respondent not later than August 10 and will

also furnish the names and addresses of the field work

ers who assembled the original data in Arkansas. Not

later than August 15 counsel for Respondent will

advise opposing counsel and the Court as to whether,

to what extent, and on what grounds he questions

any individual case schedule.

“ Subject to objections on the ground of relevancy

and materiality, and subject to challenges to individual

case schedules, Professor Wolfgang will be permitted

to testify as an expert witness and to introduce his

report as a summary exhibit reflecting and illustrat

ing his opinions. Again subject to objections or chal

lenges to individual schedules there will be no occa

sion for Petitioner to introduce the schedules in evi

dence or prove the sources of the information re

flected thereon or therein, or to call the individual

field workers as witnesses.” (Pre-Trial Conference

Order, p. 4.)

When the case came on for hearing, counsel for peti

tioner announced that no objections had been filed by the

respondent to any of the individual case schedules, so

that “ all of the facts in the schedules are treated as

though they are true, and Dr. Wolfgang’s testimony is

to be treated as though based not on schedules, but on

facts which are established of record . . . As I under

stand it, the basic facts on which Dr. Wolfgang’s testi

mony and his analysis are made are treated as estab

lished for the purpose of this case” (Tr. 8). Counsel for

respondent and the court agreed with this statement (Tr.

8-9), the court settling that:

12

“ The basic facts—that is, the age of the victim, the

race, and so on, of the individual defendants, or the

alleged victims— the basic evidentiary facts, as the

Court understands it, stand admitted, and that Dr.

Wolfgang in testifying, or anybody else who testifies

about these basic figures, will not be faced with an

objection as to the authenticity of his basic data.”

(Tr. 9.)4 * 6

On this understanding, Dr. Marvin E. Wolfgang was

called as a witness for petitioner. In its written opinion,

the district court termed him a “well qualified sociologist

and criminologist on the faculty of the University of

Pennsylvania” and noted that his “ qualifications to testify

as an expert are not questioned and are established” (257

F. Supp. at 717-718; App. A, p. 14a infra).* (Similarly,

the Court of Appeals was later to find that Dr. Wolfgang

“ obviously is a man of scholastic achievement and of ex

perience in his field,” whose “ ‘qualifications as a criminol

ogist have [concededly] never been questioned by the re

spondent.’ ” App. A, p. 30a infra.) Dr. Wolfgang’s testi

mony occupies some ninety pages of the transcript of the

hearing (Tr. 10-99); in addition, “ a written report pre

pared by him, together with certain other relevant docu

mentary material, was received in evidence without ob

jection” (257 F. Supp. at 717-718; App. A, pp. 14a-15a

infra). The written report referred to, Petitioner’s Exhibit

P-4, was received as substantive evidence (Tr. 57), and will

4 The Court of Appeals accepted this procedure without ques

tion. App. A, p. 29a infra.

6 Interrogation of Dr. Wolfgang establishing his qualifications is

at Tr. 10-14. In addition, Petitioner’s Exhibit P-1, a curriculum

vitae of Dr. Wolfgang, was received in evidence to establish his

qualifications, Tr. 14-16. Dr. Wolfgang is one of the foremost

criminologists in the country.

13

be relied upon together with Dr. Wolfgang’s testimony

in the summary of evidence that follows.

The district court’s opinion fairly summarizes the “back

ground facts of the Wolfgang study” :6

“In early 1965 Dr. Wolfgang was engaged by the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. to

make a study of rape convictions in a number of south

ern States, including Arkansas, to prove or disprove

the thesis that in those States the death penalty for

rape is disproportionately imposed upon Negro men

convicted of raping white women. Dr. Wolfgang was

apprised of the fact that the results of his study might

well be used in litigation such as the instant ease.

“As far as Arkansas is concerned, Dr. Wolfgang

caused Mr. John Monroe, a qualified statistician, to

select a representative sample of Arkansas counties

with reference to which the study would be made. The

sample drawn by Mr. Monroe, who testified at the

hearing, consisted of 19 counties in the State.

“During the summer of 1965 law students interested

in civil rights problems were sent into Arkansas to

gather basic data with respect to all rape convictions

in the sample counties for a period beginning January

1, 1945, and extending to the time of the investigation.

Data obtained as to individual cases were recorded on

individual case schedules. When the work was com

pleted, the individual schedules were turned over to

Dr. Wolfgang for evaluation.

6 The general scope of the study, which gathered data concerning

every case of conviction for rape during a 20-year period in 250

counties in eleven States, is described more fully in the affidavit

of Norman C. Amaker, Esq., attached as Exhibit 2 to the petition

for habeas corpus. For other descriptions, see the Memorandum

and Order, dated July 18, 1966, appended to the opinion in Moorer

V South Carolina, 368 F.2d 458 (4th Cir. 1966) ; and the opinion

in Matter of Sims and Abrams, 389 F.2d 148 (5th Cir. 1967).

14

“ The investigation brought to light 55 rape convic

tions during the study period involving 34 Negro men

and 21 white men. The offenses fell into three cate

gories, namely: rapes of white women by Negro men;

rapes of Negro women by Negro men; and rapes of

white women by white men. No convictions of white

men for raping Negro women were found.” (257 F.

Supp. at 718, App. A, pp. 15a-16a infra. See also the

opinion of the Court of Appeals, App. A, pp. 30a-31a

infra.)

The design of the investigation was described by Dr.

Wolfgang as a function of its objectives “ to collect the

appropriate kind of data necessary to provide some kind

of empirical study, either in support of, or in rejection

of, the underlying assumption” (Tr. 17)—i.e., that there is

racially differential imposition of the death penalty for

rape in the States studied (Tr. 16-17)—and “ to give the

empirical data the appropriate kind of statistical analysis

that would satisfy scientific requirements” (Tr. 17). The

basic research methodology involved these several stages:

(1) identification of the cases to be studied; (2) collection

of data concerning the critical variables (race of defen

dant, race of victim, sentence imposed) in each case, and

statistical analysis of the relationship between these vari

ables; (3) collection of data concerning other variables

(“ control” variables) in each case, and statistical analysis

of the relationship between each such variable and the

critical variables (race and sentence) to determine whether

the operation of the control variables could explain or

account for whatever relationship might be observed be

tween the critical variables; (4) reporting of results of

the analysis. It is convenient to summarize the evidence

presented to the district court under these four heads,,

with respect to the Arkansas study. Such a summary can

15

only imperfectly portray the character and range of the

Wolfgang study. We respectfully invite the Court’s at

tention to the whole record of the hearing below.

1. Identification of the Cases to Be Studied.

Data were gathered concerning every case of conviction

for rape during a 20-year period (January 1, 1945 to the

summer of 1965) in a representative sample of Arkansas

counties (Tr. 21). Two points should be noted here.

First, because the study begins with cases of conviction

for rape, it addresses itself at the outset to the possibility

suggested by the Supreme Court of Arkansas on the direct

appeal in petitioner’s case, Maxivell v. State, 236 Ark. 694,

370 S.W.2d 113 (1963), that any showing that Negroes are

more frequently sentenced to death for rape than whites

might be accounted for by the supposition that Negroes

commit rape, or are convicted of rape, more frequently

than whites. What is compared in this study is the rate

of capital sentencing of Negro and white defendants all of

whom have been convicted of rape.

Second, in order to give a valid basis for generalization

about the performance of Arkansas juries, every case of

conviction for rape in a randomly selected sample of Ar

kansas counties was included in the study (Tr. 62-63). The

county sampling procedure was employed because re

sources available for the field study did not permit the

gathering of data in every county in the State (Tr. 21,

107-111), and because it is “unnecessary to collect every

individual case, so long as the sample is presumed to be

a valid representation—a valid representative one” (Tr.

21). At Dr. Wolfgang’s request, a random sample (Tr.

128) of Arkansas’ 75 counties was drawn by Mr. John Mon

roe, a “qualified statistician” (257 F. Supp. at 718; App. A,

p. 15a infra), with seventeen years experience in sampling

16

and surveys (App. A, pp. 34a-35a infra).1 Testifying below,

Mr. Monroe described in detail the sampling- process used

(Tr. 107-141) to draw counties “ in such a manner that the

sample counties within each state would provide a repre

sentative sampling for that state so that inferences could

be drawn for each state in the sample and for the region

as a whole” (Tr. 107). Nineteen counties in the State (Tr.

28, 118; 122-123; Petitioner’s Exhibit P-5, appendices C,

D ; Petitioner’s Exhibit P-7) containing more than 47 per

cent of the total population of Arkansas (Petitioner’s Ex

hibit P-4, p. 1; Tr. 130) were drawn by a “ theoretically

unbiased” random method (Tr. 118). See App. A, pp. 35a-

36a infra. Mr. Monroe testified that “ a sample is the pro

cedure of drawing* a part of a whole, and if this sample

is drawn properly according to the law of chance, or with

known probability, by examining a small part of this whole,

and using the appropriate statistical methods, one can

make valid inferences about the whole population from

examining a small part” (Tr. 116). He concluded that his

own sample of Arkansas counties “ is a very reliable sample

under the restrictions that we were confined to, the num

ber of counties that could be investigated during the time

allotted. In other words, for the size of the sample, the

19 counties, it was a very reliable and highly acceptable

sample insofar as sampling statistics are concerned” (Tr.

118; see also Tr. 130, 132). “ I would say that, as far as

the sample is concerned, the inferences drawn from this

sample, as described, are valid for the State of Arkansas”

(Tr. 135).

(These conclusions were not questioned by the courts

below, although, as we shall see, both courts were con- 7

7 Mr. Monroe’s qualifications appear at Tr. 104-106. His biog

raphy, in summary form, was admitted as Petitioner’s Exhibit P-10

(Tr. 144-145).

17

cerned over the circumstance that Mr. Monroe’s areal

sampling methods resulted in the selection of counties that

lie principally in the southern and eastern portions of the

State. This circumstance was apparently not thought to

impugn the sample’s factual representativeness—to the

contrary, as the record shows and the district court found

(257 F. Supp. at 720, App. A, p. 19a infra), the sampling

method was “acceptable statistically”—but it was given

importance by the legal theory of both courts that peti

tioner was required to show that Garland County, not the

State of Arkansas as a whole, applied the death penalty

for rape discriminatorily. The legal issue thus raised is

one of those on which this petition for certiorari seeks

review. See pp. 55-56 infra. What it is important to note

here is simply that neither court below contested the un

contradicted factual assertions of Mr. Monroe, as an ex

pert statistician, that conclusions drawn from data gathered

in his sample counties would be valid for the State of

Arkansas. See App. A, p. 35a infra.)

2. Data Concerning the Critical Variables (Race

and Sentence) and Statistical Analysis of the

Relationship Between Them.

For each individual case of conviction of rape, data were

gathered as to race of defendant, race of victim, and sen

tence imposed (Tr. 28-30).8 Using approved statistical

techniques, analysis was performed to determine the re

lationship among these variables (Petitioner’s Exhibit P-4, * 10

8 The sources from which these data, and other data relating to

the individual cases of rape convictions studied, were obtained is

described in detail in Petitioner’s Exhibit P-3, pp. 1-6. See note

10, infra. Because the accuracy of all the basic data was con

ceded by the respondent below, see text supra at pp. 10-12, methods

of data collection and data sources were, not developed at the

hearing, and Exhibit P-3 was put in merely for the information

of the court.

18

pp. 2-4). Briefly, the analysis involved these steps: (a)

erection of a scientifically testable “null hypothesis” “as

serting there is no difference in the distribution . . . of the

sentence of death or life imprisonment imposed on Negro

or white defendants” (Tr. 30-31; see also Tr. 31-32); (b)

calculation of a “ theoretical or expected frequency” (Tr.

33) which represents the number of Negro defendants and

the number of white defendants (or, more specifically, the

number of Negro defendants convicted of rape of white

victims, and of all other defendants) who would be ex

pected to be sentenced to death if the null hypothesis (that

sentence is not related to race) were valid (Tr. 32-33) ; (c)

comparison of this “ theoretical or expected frequency” with

the frequency of death sentences actually observed in the

collected data for each racial combination of defendants

and victims; and (d) determination whether the discrep

ancy between the expected and observed frequencies is suf

ficiently great that, under generally accepted statistical

standards, that discrepancy can be said to be a product

of the real phenomena tested, rather than of the operation

of chance within the testing process, sampling, etc. (Tr.

33-37). “ I f that difference reaches a sufficiently high pro

portion, sufficiently high number, then the assertion can be

made, using again the traditional cut-off point,9 that the

difference is significant and could not have occurred by

9 Dr. Wolfgang explained in considerable detail the procedures

by which relations among items of observed data are tested statis

tically for reliability, “not only in sociology and social sciences,

but other disciplines as well, . . . such as medical research” (Tr.

36). The basic procedure used in the present study—the chi-square

method of statistical analysis and the traditional measure of statis

tical “significance” which treats as real observed relationships that

could not have occurred more than five times out of one hundred

by chance (expressed in the formula P < .05)— is described at

Tr. 33-37, with explication of these matters by reference to the

familiar example of head-or-tail coin tossing.

19

chance” (Tr. 34). See App. A, pp. 30a-31a infra. The result

of this analysis, then, is the determination whether there

is a relationship or “ association” between Negro defend

ants convicted of rape of white victims and the death sen

tence imposed by Arkansas juries; and if so, whether that

relationship or association is “ significant” in the statistical

sense that the possibility of its occurrence by chance is so

slight as properly to be discounted. (See Petitioner’s Ex

hibit P-4, pp. 2-4.) (As we shall see infra, such a relation

ship, showing disproportionately frequent death sentencing

of Negroes convicted of rape of white victims, was in

fact established by the data.)

3. Data Concerning “ Control” Variables.

Data gathering did not stop, however, with the facts of

race and sentence. As explained by Dr. Wolfgang, data

were collected on numerous other circumstances attending

each case of conviction for rape that “were felt to be rele

vant to the imposition of the type of sentence” (Tr. 40).

These data were sought by the exhaustive inquiries that

occupy 28 pages of small type on the data-gathering form

that is Petitioner’s Exhibit P-2—inquiries concerning the

defendant (age; family status; occupation; prior criminal

record; etc.), the victim (age; family status; occupation;

husband’s occupation if married; reputation for chastity;

etc.), defendant-victim relationship (prior acquaintance if

any; prior sexual relations if any; manner in which defen

dant and victim arrived at the scene of the offense), cir

cumstances of the offense (number of offenders and vic

tims; place of the offense; degree of violence or threat

employed; degree of injury inflicted on victim if any;

housebreaking or other contemporaneous offenses com

mitted by defendant; presence vel non at the time of the

offense of members of the victim’s family or others, and

threats or violence employed, or injury inflicted if any,

20

upon them; nature of intercourse; involvement of alcohol

or drugs; etc.), circumstances of the trial (plea; presenta

tion vel non of defenses of consent or insanity; joinder of

defendant’s rape trial with trial on other charges or trial

of other defendants; defendant’s representation by counsel

(retained or appointed) at various stages of trial and sen

tencing; etc.), and circumstances of post-trial proceedings

if any. See App. A, pp. 31a-32a infra.

The district court aptly characterized these factors as

“ Generally speaking, and subject to certain exceptions, . . .

variables . . . which reasonably might be supposed to either

aggravate or mitigate a given rape” (257 F. Supp. at 718

n. 8; App. A, p. 16a infra). Their exhaustive scope appears

upon the face of Petitioner’s Exhibit P-2, and from Dr.

Wolfgang’s testimony: “ The principle underlying the con

struction of the schedule [Petitioner’s Exhibit P-2] was

the inclusion of all data that could be objectively collected

and transcribed from original source documents that were

available to the investigators—the field investigators— such

as appeal transcripts, prison records, pardon board rec

ords, and so forth, and whatever was generally available

was included. In this sense, it was a large eclectic ap

proach that we used for the purpose of assuring ourselves

that we had all available data on these cases” (Tr. 96-97;

see also Tr. 65-70). Dr. Wolfgang conceded that some data

potentially pertinent to sentencing choice were not collected

__for example, strength of the prosecution’s case in each

individual rape trial—but explained that this was because

such items were not information “that we could objectively

collect” (Tr. 97). See App. A, p. 32a infra.

The pertinency of these data to the study was that some

of the many circumstances investigated, “ rather than race

alone, may play a more important role in the dispropor-

21

tionate sentencing to death of Negro defendants convicted

of raping white victims” (Tr. 40).

“ These factors, not race, it could be argued, may be

determining the sentencing disposition; and Negroes

may be receiving death sentences with disproportionate

frequency only because these factors are dispropor

tionately frequent in the case of Negro defendants.

For example, Negro rape defendants as a group, it

may be contended, may employ greater violence or do

greater physical harm to their victims than do white

rape defendants; they may more frequently be repre

sented at their trials by appointed rather than retained

counsel, and they may more frequently commit con

temporaneous offenses, or have a previous criminal rec

ord, etc.” (Dr. Wolfgang’s written report, Petitioner’s

Exhibit P-4, p. 5.)

In order to determine whether the control variables ex

plained or accounted for the racial disproportion in death

sentencing, analysis had to be made of the relationship

between each such factor for which data were available

and sentence on the one hand, race on the other. Dr. W olf

gang explained that no variable could account for the sig

nificant association between Negro defendants with white

victims and the death sentence unless that variable “was

significantly associated with the sentence of death or life”

(Tr. 41), and unless it also was significantly associated

with Negro defendants convicted for rape of white victims

(Tr. 41-42).

A variable, even though associated with such Negro de

fendants (i.e., found disproportionately frequently in their

cases), could not furnish a non-racial explanation for their

over-frequent sentence to death unless it was itself affect

ing the incidence of the death sentence (as evidenced by

22

its significant association with the death sentence) (see,

e.g., Tr. 45-46); while a variable which was not associated

with Negro defendants convicted of rape of white victims

could also not explain the frequency with which they, as

a class, were sentenced to death (e.g., Tr. 49-52). (See gen

erally Petitioner’s Exhibit P-4, pp. 6-7.)

4. Results and Conclusions.

Based on his study of the data gathered for the past

twenty years in the State of Arkansas, Dr. Wolfgang con

cluded categorically that “compared to all other rape de

fendants, Negroes convicted of raping white victims were

disproportionately sentenced to death,'” (Dr. Wolfgang’s

written report, Petitioner’s Exhibit P-4, p. 8, para. 3 (origi

nal emphasis).) ‘W e found a significant association be

tween Negro defendants having raped white victims and

the disproportionate imposition of the death penalty in com

parison with other rape convictions” (Tr. 52; see also Tr.

37-39). Indeed, the disparity of sentencing between Negroes

with white victims and all other racial combinations of con

victed defendants and victims was such that it could have

occurred less than twice in one hundred times by chance

(Tr. 37-38)—i.e., if race were not really related to capital

sentencing in Arkansas, the results observed in this twenty-

year study could have occurred fortuitously in two (or

less) twenty-year periods since the birth of Christ. Thus,

the Wolfgang study for the first time documents the dis

crimination which previously available data—not collected

systematically or in a form permitting rigorous scientific

analysis—could only suggest: for example, the Federal

Bureau of Prisons’ National Prisoner Statistics for execu

tions during the period 1930-1962 (Petitioner’s Exhibit

P-6, Tr. 99-101), which disclose that more than nine times

as many Negroes as whites were put to death for rape dur

23

ing this period in the United States, although the numbers

of Negroes and whites executed for murder were almost

identical.

A considerable part of Dr. Wolfgang’s testimony was ad

dressed to the question whether this disproportion could be

explained away or accounted for by the operation of other,

non-racial (“control” ) variables. He testified that after the

Arkansas data were collected, he considered and subjected

to analysis every such variable or factor about which suf

ficient information was available to support scientific study

(Tr. 56, 64-65, 78-80, 97). With respect to a substantial

number of the variables investigated by the field research

ers, their exhaustive exploration10 failed to provide enough

information for study. (E.g., victim’s reputation for

10 By reason of the court’s pre-trial order and respondent’s con

cession under the procedures fixed by that order that the responses

recorded by the field researchers on the individual case schedules

were accurate (see pp. 10-12, supra), petitioner did not present in

any systematic fashion below testimony relating to the data-gather-

ing procedures. The concession, of course, included the accuracy

of the response “ unknown” wherever that appeared on a schedule,

and—as counsel for petitioner pointed out in the district court,

without disagreement from respondent or the court—the response

“unknown” “means that research, using the State’s records and

using all of the resources that we have poured into this ease, is

unable to make any better case than this” (Tr. 155-156).

The nature of the research effort involved is indicated by Peti

tioner’s Exhibit P-3 (Tr. 25-27, 57), the instructions to the field

researchers. Those instructions include the following, at pp. 4-6:

“Whether the work is done by a single researcher or divided

among more than one, the course of investigation of any spe

cific case will ordinarily involve the following steps:

“ (1) Inspection of the county court docket books for en

tries relating to the case.

“ (2) Inspection of all other records relating to the case

available at the county court: file jackets, transcripts, witness

blotters, letter files, pre-sentence reports.

“ (3) Inspection of appellate court records in any case where

appeal was taken. Appellate court records include the doeket

of the appellate court, its file jacket, record on appeal (if

24

chastity, Tr. 79.) Notwithstanding respondent’s pre-trial

concession of the accuracy of the field researchers’ re

maintained on file in the appellate court), court opinion or

opinions if any, and appellate court clerk’s letter file.

“ (4) Inspection of prison records of the defendant if he

was incarcerated in a prison which maintains records.

“ (5) Inspection of pardon board records in any case where

the defendant submitted any application for executive clem

ency.

“ (6) If the foregoing sources fail to provide sufficient in

formation to complete the schedule on the ease, interview of

defense counsel in the case.

“ (7) If the foregoing sources fail to provide sufficient in

formation to complete the schedule on the case, inspection of

local and area newspaper files for items pertaining to the case.

“Three general directives should be kept in mind:

“ (A ) We are concerned with the sentencing decision, in

each case, of a particular official body at a particular time

(i.e., the trial judge or jury; the pardon board). Every such

body acts— can act— only on the facts known to it at the time

it acts. For this reason, the “facts” of a ease called for by

the schedule mean, so far as possible, the facts perceived by

the sentencing body. Facts which we know to have been

known to the sentencing body are preferred facts, and sources

which disclose them are preferred sources. (A trial transcript,

where it exists, is therefore the most desirable source of facts.)

Other sources are of decreasing value as the likelihood de

creases that the facts which they disclose were known to the

sentencing body. (A newspaper story which purports to re

port trial testimony, therefore, is to be preferred to one which

purports to report the facts of the offense on the basis of

other sources of information.)

“ (B) After this survey is completed, its results will be made

the basis for allegations of fact in legal proceedings. If the

allegations are controverted, it will be necessary to prove them,

and the proof will have to be made within the confines of

ordinary evidentiary rules, including the hearsay principle,

best evidence rule, etc. For this reason, sources of facts which

are judicially admissible evidence to prove the facts which

they disclose are preferred sources. Official records are most

desirable in this dimension; then the testimony of witnesses

having knowledge of the facts (for example, defense counsel),

finally, secondary written sources (for example, newspapers).

25

sponses on the individual case schedules, including the

response “unknown” where that appeared (see note 10

supra), counsel for respondent attempted to suggest in

cross-examination of Dr. Wolfgang that these gaps in in

formation impugned the underlying data-gathering process.

Dr. Wolfgang replied:

“ the absence of information, I would be unwilling to as

sert is due to lack of any effort. Very diligent efforts

were made by the field investigators to collect the in

formation—from court clerks, from police records,

from prisons, from other sources available in the com

munity—and they were instructed to follow down each

piece of information, each source of information to its

fullest extent, so that I have no reason to doubt that

the effort was made to collect the data” (Tr. 80).

Wherever an official record or document may contain perti

nent information, inspect it yourself if you can; don’t take

somebody’s word for what is in it.

“ (C) Many of the faets you need to know will have been

contested in the judicial and post-judicial proceedings lead

ing to a defendant’s sentence and its execution. We have no

method for resolving factual disputes or, ordinarily, for know

ing how the triers of fact resolved them. As an invariable

rule, then, the facts should be reported in the light most

favorable to the prosecution, and most unfavorable to the

defendant, in every case. If a trial transcript exists, and if

it contains the testimony of the complaining witness and of

the defendant, resolve all conflicts of testimony in favor of

the complaining witness and report the facts as they might

reasonably have been found by a jury which credited the

complaining witness, drew all rational inferences from her

testimony most strongly against the defendant, discredited

the defendant, and refused to draw any disputable inferences

in his favor. Treat all other sources in a similar fashion. In

interviews with defense counsel, try to impress upon counsel

that you have to have the facts as they might have appeared

in the worst light for his client. In reading newspaper items

which give conflicting versions of the facts, adopt the version

most unfavorable to the defendant.”

2 6

His testimony as a whole makes it clear that— although, as

he put it: “ Information is always limited” (Tr. 72)—he

was confident that he had enough of it to support his con

clusions. (See particularly Tr. 76-79.)

He was able to subject twenty-two “quite relevant vari

ables” (Tr. 78)—in addition to race of defendant, race of

victim, and sentence—to analysis. (See Petitioner’s Ex

hibit P-4, Appendix A ; Tr. 29, 52.) Most of these were not

significantly associated with sentence, and so Dr. W olf

gang could assert categorically that they did not account

for or explain the disproportionately frequent death sen

tencing of Negroes with white victims (Tr. 42-46, 53-54).

These variables included the defendant’s age, whether he

was married, whether he had dependent children, whether

he had a prior criminal record; the victim’s age, whether

she had dependent children; whether the defendant and

victim were strangers or acquaintances prior to the offense;

place where the offense occurred (indoors or outdoors),

whether the defendant committed an unauthorized entry in

making his way to that place; whether the defendant dis

played a weapon in connection with the offense; degree of

seriousness of injury to the victim; and the defendant’s

plea (guilty or not guilty), type of counsel (retained or

appointed), and duration of trial (Tr. 47, 53; Petitioner’s

Exhibit P-4, p. 9, para. 5; Petitioner’s Exhibit P-5). Two

variables were shown to bear significant association with

sentence: death sentences were more frequent in the eases

of defendants who had a prior record of imprisonment, and

in the cases of defendants who committed other offenses

contemporaneously with the rape. But because these vari

ables were not associated with race,11 Dr. Wolfgang con-

11 Statistical analysis of the association between these variables

and race of the defendant disclosed no significant association.

When defendant-victim racial combinations were considered, the

27

eluded that they also could not account for the fact that

Negroes convicted of rape of white victims were dispropor

tionately often sentenced to death (Tr. 47-52, 54; Peti

tioner’s Exhibit P-4, pp. 8-9, para. 4; Petitioner’s Exhibit

P-5). Other variables appeared so frequently or so in

frequently in the total population of cases studied that

statistical analysis of them was “unnecessary and impos

sible” : the fact that they appeared to characterize all cases

(or no cases), irrespective of sentence or of racial com

binations of defendant and victim, pointed to the conclu

sion that they were not available explanations for the re

lationship observed between death sentences and Negroes

with white victims. These variables included the victim’s

reputation for chastity and prior criminal record; whether

the defendant and victim had had sexual relations prior

to the occasion of the rape; the degree of force employed by

the defendant; whether the victim was made pregnant by

the rape; and whether the defendant interposed a defense

of insanity at trial (Tr. 54-55, 94-95, Petitioner’s Exhibit

P-5). Summarizing, Dr. Wolfgang found that no variable

of which analysis was possible could account for the ob

served disproportionate frequency of sentencing to death

of Negroes convicted of rape of white victims (Tr. 56-57).

His ultimate conclusion was:

“ On the basis of the foregoing findings, it appears

that Negro defendants who rape white victims have

been disproportionately sentenced to death, by reason

of their race, during the years 1945-1965 in the State

of Arkansas.” (Dr. Wolfgang’s written report, Peti

tioner’s Exhibit P-4, pp. 13-14 (emphasis added).)

numbers of cases for which information was available became too

small for statistical treatment, but on the basis of trend of as

sociation, Dr. Wolfgang concluded that here too there was no

association of significance.

28

C. The Opinions Below.

1. The Issue of Racial Discrimination in

Capital Sentencing for Rape.

Although respondent presented no evidence of any sort

in rebuttal, the district court disagreed with Dr. W olf

gang’s conclusions. It accepted his finding that the differ

ential sentencing to death of Negroes with white victims

“ could not be due to the operation of the laws of chance”

(257 F. Supp. at 718; App. A, p. 16a infra) ; but supposed,

again without any sort of evidentiary presentation by the

State, that it might be due to some factor respecting which

statistical analysis had not been possible, such as the issue

of consent in rape cases (257 F. Supp. at 720-721; App. A,

p. 21a infra). The Court remarked that the “variables

which Dr. Wolfgang considered are objective . . . broad and

in instances . . . imprecise” ; that in many of the individual

rape cases studied “ the field workers were unable to obtain

from available sources information which might have been

quite pertinent” ; and that “Dr. Wolfgang’s statistics really

reveal very little about the details” of comparative indi

vidual cases of rape. (257 F. Supp. at 720; App. A, p.

20a infra.) While recognizing that “the sample drawn by

Mr. Monroe seems to have been drawn in a manner which

is acceptable statistically” (257 F. Supp. at 720; App. A,

p. 19a infra), the court noted that the counties ran

domly chosen had turned out not to be evenly geographically

dispersed, and not to include many counties of sparse Negro

population {ibid.). Garland County, which was not itself in

cluded in the sample, is a county of sparse Negro popula