Duffield v. Robertson Stephens & Company Brief for Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

August 7, 1997

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Duffield v. Robertson Stephens & Company Brief for Amici Curiae, 1997. f9369b49-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d6d8d359-638d-4f53-951c-e7828adc4dcc/duffield-v-robertson-stephens-company-brief-for-amici-curiae. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

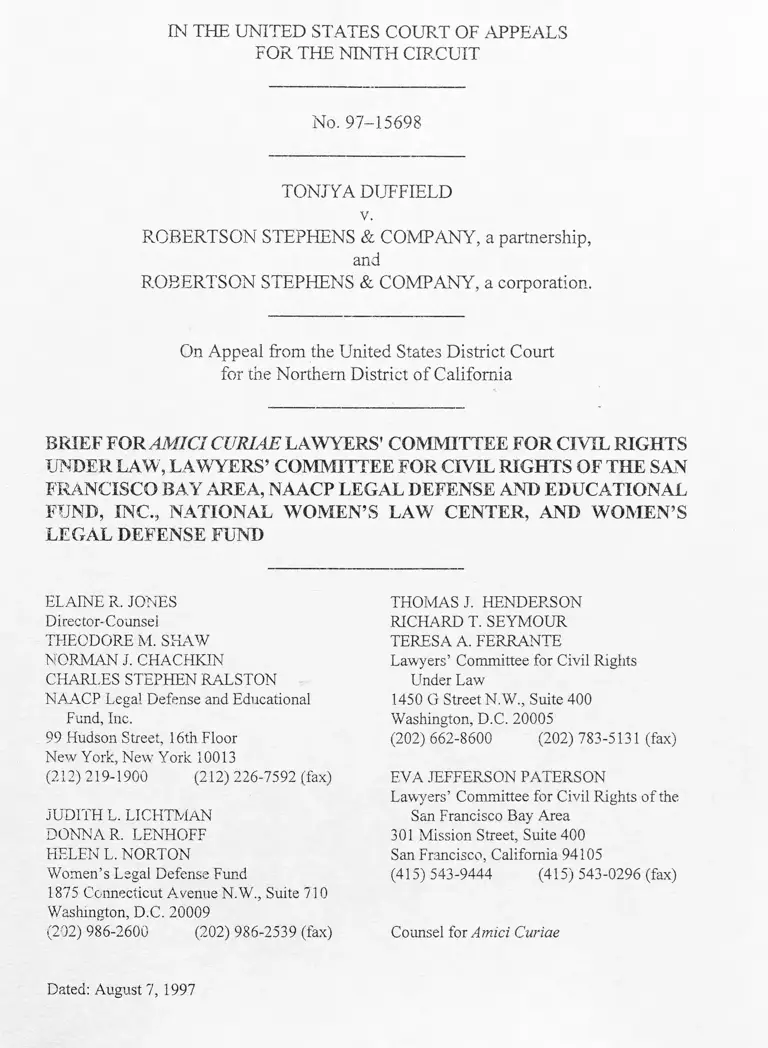

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 97-15698

TONJYA DTJFFIELD

v.

ROBERTSON STEPHENS & COMPANY, a partnership,

and

ROBERTSON STEPHENS & COMPANY, a corporation.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

BRIEF FOR AM ICI CURIAE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS OF THE SAN

FRANCISCO BAY AREA, NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER, AND WOMEN’S

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

THEODORE Ivl. SHAW

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900 (212) 226-7592 (fax)

JUDITH L. LICHTMAN

DONNA R. LENHOFF

HELEN L. NORTON

Women’s Legal Defense Fund

1875 Connecticut Avenue N.W., Suite 710

Washington, D.C. 20009

(202) 986-2600 (202) 986-2539 (fax)

THOMAS J. HENDERSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

TERESA A. FERRANTE

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Linder Law

1450 G Street N.W., Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8600 (202) 783-5131 (fax)

EVA JEFFERSON PATERSON

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the

San Francisco Bay Area

301 Mission Street, Suite 400

San Francisco, California 94105

(415) 543-9444 (415) 543-0296 (fax)

Counsel for Amici Curiae

Dated: August 7, 1997

Certificate of Compliance

In compliance with Ninth Circuit Rule 32(e)(4), amicus certifies that this

brief is double-spaced, and was printed in the proportional Times New Roman

type face, with 14-point type. The word count for the brief as a whole, exclusive

of the cover, this Certificate, the Table of Contents and Table of Authorities, and

the Certificate of Service, is 6,281 words. The average number of words per page

for the 32 pages of this brief is 196.3 words per page.

- 1 -

Table of Contents

Interest of A m ic i...................................................................... 1

Statement of the Case ...................................................................... 4

Summary of the Argument .......................................................................... 4

A rgum ent.............................................................................. 8

A. The Arbitration Procedures in Question Are Subject to the

Requirements of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause ........ 8

1. The Lower Court Itself Engaged in State A ction..................... 8

2. Independently, the SEC’s Regulation Constituted State

Action Because It Barred the Parties from Renegotiating

the Arbitration Provision and Agreeing on judicial

Enforcement of Plaintiffs’ C la im s............................. 13

3. Independently, the Imposition on Employees of an

Exclusive Procedure for the Enforcement of Employees’

Statutory and Common-Law Rights Imposes Due

Process-Type Obligations on the NYSE and on

Employers Like the A ppellee......................................................15

B. The Record Llerein Raises Serious Due Process Concerns,

Which the District Court Did Not Adequately A ddress................... 17

1. Compelling Victims to Use Procedures Violating Due

Process Is Likely to Chill the Willingness of Victims to

Assert Their R ights...................................................................... 17

2. The District Court Erroneously Ignored Plaintiffs

Evidence that the Actual Application of NYSE

Procedures Results in Violations of Due Process ....................19

C. The Legislative History of § 118 of the Civil Rights Act of

1991 Makes Clear that Mandatory Pre-Dispute Arbitration

Provisions Are Not an Appropriate Means of Enforcing the

Statute ......................................................................................................29

- ii -

Conclusion 32

Table of Authorities

1. Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ..............................................3

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)......................................... 15

Bates v. State Bar o f Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1 9 7 7 )............................................... 11

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1 9 7 1 )............................................... 9, 23, 24

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715 (1961) ..........................12

Christians burg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) ............................ . 28

Cole v. Burns In t’l Security’ Services, 105 F.3d 1465 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 9 7 )......... 26, 27

Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 5 00 U .S .6 1 4 (1 9 9 1 ).................................. 11

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community Organization,

420 U.S. 50 (1975) ......................................................................................... 16

Gilmer v. Interstate / Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991) . . . . 8, 19, 20, 23

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956)................................................................ 23, 25

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1 9 7 1 )..................................................... 3

In t’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ............................ 26

J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B., 511 U.S. 127 (1994) ............................................. 11

Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public Schools, 487 U.S. 450 (1988)................................ 24

- iii -

Little v. Streater, 452 U.S. 1 (1981) .........................................................................24

Lugar v. Edmondson Oil Co., 457 U.S. 922 (1982)............................................... 11

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) .................................... 3

McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co.,

__ U .S.__, 115 S. Ct. 879 (1995).....................................................................3

Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc.,

473 U.S. 614(1985) .................................................................................. 20, 23

M.L.B. v. S.L.J.,__U .S.__ , 117 S. Ct. 555 (1996) ............................................. 24

NAACPv. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .................................................................... 2

National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Tarkanian, 488 U.S. 179 (1988) . . . 10

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968) ................... 25, 28

Oldham v. West, 47 F.3d 985 (8th Cir. 1995).......................................................... 28

Ortwein v. Schwab, 410 U.S. 656 (1973)................................................................ 24

Shankle v. B—G Maintenance Management,

74 FEP Cases 94 (D. Colo. 1997)................................................................ 25

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1 9 4 8 ).................................................................... 12

Smithv. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ................................................................ 11

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944) .............................. 16

Lindsey v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 (1972) ............... ................................................... 24

- iv -

Tomsic v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co.,

85 F.3d 1472 (10th Cir. 1996) ................................ .'.............. .....................28

Tunstall v. Bhd. o f Locomotive Firemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944) ............................ 16

United States v. Kras, 409 U.S. 434 (1973)............................................................ 24

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1967).................................................................... 16,17

2. Constitutional, Statutory, and Regulatory Provisions

Fifth Amendment to the Constitution . ...................................................................5,8

Seventh Amendment to the Constitution .................................................................. 5

Fourteenth Amendment to the C onstitution............................................................11

Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution.................................................................. 11

42U.S.C. § 1983 ......................................................................................................... 10

Civil Rights Act of 1991, 105 Stat. 1071 ..............................................................4, 8

§ 118 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 .......................................................... 29,30,31

Family and Medical Leave A c t .....................................................................................4

National Labor Relations Act .................................................................................. 16

Pregnancy Discrimination Act .....................................................................................4

Railway Labor A c t......................................................................................... 16

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)...................................................................... 11

- v -

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .................................................................. 28

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq............................................ 3, 7, 8, 15, 28, 29, 30,31

Sec. 706(f)(1) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(l) ......................................... 25

17 C.F.R. § 250.15b7-l ............................................................................................13

3. Legislative Materials

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 755, 101st Cong., 2d Sess. 26 (1 9 9 0 ).................................. 29

H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part I, 102d Cong., 1st Sess. 97 (1991)

(House Education and Labor Committee) ................................................... 30

H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part II, 102d Cong., 1st Sess. 41 (1991)

(House Judiciary Com m ittee).................................................................... .. 30

137 Cong. Rec. H9526, 9530 (daily ed., Nov. 7, 1 9 9 1 )........................................ 30

4. Other Materials

Jacobs, Margaret, M en’s Club: Riding Crops and Slurs: How Wall Street Dealt

with a Sex Bias Case, WALL STREET JOURNAL, June 9, 1994, p. 1 ...........18

Ninth Circuit Advisory Committee’s Note to Ninth Circuit Rule 29 -1 ...............4

Reuben, Richard C., Public Justice: Toward a State Action Theory o f Alternative

Dispute Resolution, 85 CALIF. L. REV. 579 (1 9 9 7 )...................................... 9

Securities Industry Conference on Arbitration,

The Arbitrator’s Ma n u a l ..................................................... 20, 21,27, 28

- VI

Interest of Amici

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. was founded in 1963 by

the leaders of the American bar, at the request of President Kennedy, in order to help

defend the civil rights of minorities and the poor. Our Board of Trustees presently

includes several past Presidents of the American Bar Association, past Attorneys

General of the United States, numerous law school deans, and many of the nation’s

leading lawyers. Our litigation docket includes numerous civil rights cases across the

country, including a large number of cases challenging discrimination in employment

on the basis of race or sex. The Lawyers’ Committee is a private, tax-exempt,

nonprofit civil rights organization. It has either represented a party, or has filed an

amicus brief, in the majority of the civil rights decisions handed down by the

Supreme Court over the last three decades. It has testified on numerous occasions

before Congressional committees holding hearings on the enforcement of the civil

rights laws. The Lawyers’ Committee makes concentrated efforts to enlist the private

bar in efforts to ensure civil rights, including litigation on behalf of the victims of

discrimination, and so has a particularly strong interest in questions affecting access

to the courts, the availability of an impartial and law-governed forum for the

adjudication of civil rights claims, the availability of an adequate process for

- 1 -

reviewing determinations on liability, and the availability of full relief in all fora, for

the alleged victims of civil rights violations.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area

(hereafter, “San Francisco Lawyers’ Committee”) is a non-profit, tax-exempt civil

rights organization devoted to advancing the rights of people of color, immigrants,

and refugees, and other under-represented individuals and groups. As the Northern

California affiliate of the national Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

founded on the request of President Kennedy in 1963, the San Francisco Lawyers’

Committee was founded in 1968 by leading attorneys from Bay Area law firms. The

Lawyers’ Committee has maintained an extensive civil rights litigation docket for the

thirty years of its existence. It is committed to the vindication of rights through the

courts.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“the Fund”), is a non

profit corporation that was established for the purpose of assisting African Americans

in securing their constitutional and civil rights. The Supreme Court has noted the

Fund’s “reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions of

law that frequently arise in civil rights litigation.” NAACP v. Button, 371U.S. 415,

422 (1963). The Fund has taken a leading role in the development of the law of

- 2

employment discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other

statutes, acting as counsel in many of the leading cases brought under these statutes.

See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); McDonnell Douglas Corp.

v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975);

and McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing C o .,__U.S. __ 115 S. Ct. 879

(1995).

The National Women’s Law Center (“NWLC”) is a nonprofit legal advocacy

organization dedicated to the advancement and protection of women’s rights and the

corresponding elimination of sex discrimination from all facets of American life.

Since 1972, NWLC has worked to secure equal opportunity in the workplace through

the full enforcement of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as amended. NWLC

has a deep and abiding interest in assuring the eradication of discrimination against

women in the workplace.

Established 25 years ago, the Women’s Legal Defense Fund (“WLDF”) is a

national advocacy organization that promotes policies to ensure equal opportunity

and economic security for women, especially low-income women and women of

color. Throughout its history, WLDF has placed special emphasis on ensuring

effective and vigorous enforcement of Title VII and other antidiscrimination laws by

- 3 -

monitoring agencies’ enforcement efforts, challenging sex discrimination through

litigation, and leading efforts to promote federal employment policies such as the

Pregnancy Discrimination Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, and the Family and

Medical Leave Act.

Both the appellant and the appellees have consented to this filing. The letters

of consent have been lodged with the Clerk.

Statement of the Case

In light of the Ninth Circuit Advisory Committee’s Note to Ninth Circuit Rule

29 -1 , amici adopt the appellant’s Statement of the Case.

Summary of the Argument

Amici have examined the record and the filings of the parties in the district

court, and agree with the positions advanced by the appellant and by the U.S. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission. In light of the Ninth Circuit Advisory

Committee’s Note to Ninth Circuit Rule 29 -1, amici have not attempted to duplicate

those arguments. We file this brief to focus on three issues of great concern arising

from the district court’s disposition of this action.

First, the district court misunderstood the presence of state action in this case,

and as a result failed to measure the particular arbitral practices of the New York

- 4 -

Stock Exchange (hereafter, “NYSE”) against the standards of due process required

by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. The judicial enforcement of the

arbitration provision is itself governmental action triggering the protections of the

Fifth Amendment’s due process clause. Unlike the judicial enforcement of routine

contractual provisions, the arbitration provision at issue here involves a traditionally

exclusive governmental function—the resolution of disputes involving rights enacted

by Congress— and a risk against which government traditionally guards—that a

change of procedure forced on employees by the superior economic power of their

employers will amount to a forced waiver of the rights granted by Congress.

While individuals remain free to decide existing disputes by flipping a coin or

by any other procedure not comporting with due process, we submit that different

standards must apply to the entry of a judicial order barring an individual from

exercising her constitutional and statutory right to jury trial, and barring her from the

protections of a neutral and inexpensive judicial forum, where she has never

consented to such deprivations or to a waiver of her Seventh Amendment right to jury

trial in light of the particular dispute in question. At least where the plaintiff has

presented substantial evidence that the procedure sought to be compelled does not

meet the standards of due process, the Fifth Amendment requires at a minimum that

- 5 -

the lower court examine the evidence and determine that the compelled procedure

meets the minimum standards of due process before compelling plaintiff to submit her

claim to that procedure and depriving plaintiff of her right to trial by jury.

Moreover, the district court adopted too limited a view of the role of

regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission in determining whether state

action was present in this case. While amici agree with the plaintiffs’ arguments

below on state action, we believe that state action through the SEC is present herein

even if the SEC did not require registration with a stock exchange at the time

appellant joined the appellee brokerage firm. It is undisputed that, at the time

plaintiff made her claim, the SEC’s regulations did require such registration, and thus

deprived her and the appellee of any ability to enter into a new contract providing for

the judicial resolution of employment disputes.

Because governmental action was clearly involved, on this record the district

court was obligated to examine the actual—not just the theoretic—operation of the

NYSE procedures to ensure that they comported with due process before entering an

order subjecting the plaintiff to these procedures and depriving her of the right to jury

trial.

Second, the district court failed to explain its conclusory finding that the

- 6 -

procedures of the New York Stock Exchange “adequately protect plaintiffs Title VII

rights.” August 26, 1996 Order Vacating and Modifying Order of August 6, 1996,

at 14, C.R. 68. The appellant has raised serious factual questions as to the adequacy

of the NYSE procedures. If such a finding were entered after an evidentiary hearing,

it would be too conclusory to permit reasoned review, and would thus fail to meet the

standard of Rule 52, FED. R. ClV. P. Because no evidentiary hearing was held, the

district court was not free to reject any of plaintiffs supported allegations. Instead,

it was required to accept all such allegations as true for the purposes of its decision.

The finding is therefore the equivalent of a conclusion that the procedures of the New

York Stock Exchange are adequate to protect Title VII rights even where all of the

arbitrators in a Title VII case lack knowledge of the law, are explicitly not expected

to learn anything about the law they are applying, are expressly advised that they can

substitute their own judgment for that of Congress and the courts as to the facts

necessary to establish a violation of Title VII and the appropriate remedy for a

violation, and are advised that they do not need to set forth the reasons for their

decisions, effectively precluding review for manifest disregard of the law. If due

process can be satisfied by such a procedure, it is difficult to imagine any procedure,

short of corruption, that would violate due process.

7 -

The decision in Gilmer v. Interstate/ Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991),

was entered without benefit of the information produced by plaintiff below, and does

not authorize the disregard of basic elements of due process.

Based on their decades of experience in the enforcement of the civil rights

laws, amici strongly believe that subjecting the victims of Title VII violations to the

protracted delay and expense of the type of NYSE arbitration shown in the record will

deter the victims from pressing meritorious claims.

Third, in enacting the Civil Rights Act of 1991, Congress made the judgment

that mandated pre-dispute arbitration agreements are not appropriate for the

resolution of Title VII claims. Gilmer required the lower court to respect that

judgment.

Argument

A. The Arbitration Procedures in Question Are Subject to the

Requirements of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause

1. The Lower Court Itself Engaged in State Action

The routine judicial enforcement of a routine contractual provision does not

involve governmental action. This case presents the opposite extreme: under the

authority of the Federal Arbitration Act, the lower court compelled the plaintiff to

- 8

submit to the resolution of her claims by a private body and will enforce the decision

of that private body. See generally Reuben, Richard C., Public Justice: Toward a

State Action Theory o f Alternative Dispute Resolution, 85 CALIF. L. REV. 579 (1997).

The use of governmental compulsion to resolve disputes, and governmental

enforcement of the outcome, is traditionally an area reserved for the government.

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 375 (1971), referred to “the State’s monopoly

over techniques for binding conflict resolution” and stated that the monopoly “could

hardly be said to be acceptable” without the guarantee of due process.

The appellee cannot escape the obligations of due process by insisting that the

NYSE engaged in a private decision to require the arbitration of employment

disputes. In addition to the arguments made by the appellant as to the role of the

Securities Exchange Commission, it is elementary that there is purely private action

here. The plaintiff s signature on the arbitration provision has been govemmentally

enforced, the government has deprived her of her Seventh Amendment right to jury

trial, and the outcome of the arbitration will be protected by governmental action

from anything like the type of review a judicial resolution of her claim would have

received. Through its enforcement, the government is inextricably involved in this

supposedly private dispute resolution.

9 -

In National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Tarkanian, 488 U.S. 179 (1988),

the University of Nevada at Las Vegas suspended its basketball coach, Jerry

Tarkanian, for two years in order to avoid NCAA sanctions, based on the NCAA’s

findings that Tarkanian had violated NCAA rules. Tarkanian sued both the

University and the NCAA under 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The Court held that the public

University was a state actor even though it was enforcing a private decision with

which it otherwise disagreed, and that its enforcement of the NCAA’s decision

imposing a serious disciplinary sanction on one of its tenured employees triggered the

protections of the due process clause. Id. at 192. As the Court pointed out, the

University “engaged in state action when it adopted the NCAA’s rules to govern its

own behavior.” Id. at 194. The Court remanded the case for further proceedings

against the University. Id. at 199.

Similarly, the conduct of elections is a function traditionally reserved

exclusively to the government. If a State delegates to private political parties or other

private bodies the task of conducting primary elections to determine who will run as

a political party’s candidates in the general election, or to solidify the support of

white voters behind a particular white candidate who will then run in the public

primary, the “White Primary” cases determined that the actions of the private parties

- 1 0 -

or other private bodies were nevertheless state action subject to the prohibitions of

racial discrimination in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953).

The lower court’s entanglement with the arbitration process by its compulsion

of the plaintiff to engage in arbitration is therefore State action. Lugar v. Edmondson

Oil Co., 457 U.S. 922, 941-42 (1982), found that private parties’ use of a

prejudgment attachment procedure was state action because their choice of the

procedure was enforced by the court. Bates v. State Bar o f Arizona, 433 U.S. 350,

361-63 (1977), held that the Arizona Supreme Court’s adoption and enforcement of

the American Bar Association’s recommended prohibitions on advertising by lawyers

constituted state action that both immunized the Arizona Supreme Court’s action

from challenge under the antitrust laws and exposed the prohibitions to challenge

under the First Amendment. Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., 500 U.S. 614

(1991), and J.E.B. v. Alabama exrel. T.B., 511 U.S. 127 (1994), held that the court’s

enforcement of a civil litigant’s exercise of a peremptory challenge to a juror based

on race or sex, respectively, is state action subject to constitutional restrictions. “By

enforcing a discriminatory peremptory challenge, the court ‘has not only made itself

a party to the [biased act], but has elected to place its power, property and prestige

- 11 -

behind the [alleged] discrimination.”’ Edmonson, 500 U.S. at 624, quoting Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725 (1961). Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1 (1948), held that judicial enforcement of a racially restrictive covenant on the

use and occupancy of real property was state action. “That the action of state courts

and of judicial officers in their official capacities is to be regarded as action of the

State within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, is a proposition which has

long been established by decisions of this Court.” Id. at 14. The key in each of these

cases is that, like the case at bar, the judicial enforcement inextricably intertwined the

court with the disputed private actions.

We do not argue that a court must examine every contractual provision and

procedure for potential violations of due process before enforcing it. We urge only

that, where a colorable due process problem is either apparent on the face of the

provision sought to be enforced or is brought to the attention of the court by adequate

evidence, a court must satisfy itself by appropriate means, capable of meaningful

review, that the provision or procedure in fact comports with due process before

compelling the plaintiff to submit to it.

The lower court fundamentally misconceived the role of state action in this

case, requiring reversal and a remand with instructions to allow the plaintiff to try her

- 1 2 -

claims in court.

2. Independently, the SEC’s Regulation Constituted State

Action Because It Barred the Parties from

Renegotiating the Arbitration Provision and Agreeing

on Judicial Enforcement of Plaintiffs’ Claims

The district court also erred in deciding that the Securities and Exchange

Commission had not engaged in governmental action constraining the plaintiff

because the plaintiff signed her original arbitration provision in 1988, prior to the

Commission’s May 11, 1993, adoption of 17 C.F.R. § 250.15b7—1. The lower court

erred because it considered only the parties’ entry into the arbitration clause, and

failed to consider the parties’ inability to rescind the provision after May 11, 1993.

An analogy may be useful. If a person enters into a traditional 30-year

mortgage, he or she is contractually required to make 360 monthly payments in the

agreed amounts. However, the mortgagor and the mortgagee are free to negotiate a

new interest rate, and the mortgagor is generally free to refinance his or her home by

entering into a new mortgage at a lower rate and paying off the old mortgage. If a

governmental body imposed a regulation barring the refinancing of the house, no one

could reasonably argue that such an action was not state action, or that it did not

cause a significant injury to the mortgagor.

- 1 3 -

So too, here. The plaintiff has a cause of action of undetermined value,

contingent on her prevailing. She has had such a cause of action since the actions

giving rise to it occurred. Governmental interference with that cause of action— such

as by a retroactive shortening of the period of limitations so as to wipe out otherwise

timely claims, or by compelling her to resolve her claims by arbitrary means like

flipping a coin—would clearly violate due process.

Many of plaintiffs claims arose in December 1993 and later. The Complaint

alleged that a partner of the defendant “licked the back of plaintiffs neck” in

December 1993 while she was on the telephone trading securities (CR 1, ^ 14), that

shortly before that time the same partner stared at plaintiffs breasts and claimed to

plaintiff that he was distracted by their shape (f 16), that another partner thereafter

complained of the licking incident, that plaintiff cooperated with the investigation,

and that plaintiff was subsequently treated in a hostile manner 19, 20), and that

in June 1994 plaintiff was denied her full bonus (̂ f 25). At all of these times, the

SEC’s regulation stood as an absolute bar to plaintiffs ability to negotiate with the

defendant to end the requirement that she submit to arbitration.

Contrary to the view of the district court, the SEC’s post-dispute coercion

independently triggered the protections of the due process clause.

- 1 4 -

3. Independently, the Imposition on Employees of an

Exclusive Procedure for the Enforcement of Employees’

Statutory and Common-Law Rights Imposes Due

Process-Type Obligations on the NYSE and on

Employers Like the Appellee

Finally, through the operation of the Federal Arbitration Act and judicial

compulsion, the NYSE seeks to have its arbitration system become the exclusive

means for employees to enforce their statutory and other rights. The Constitution

does not allow any entity to limit the means of enforcing publicly granted rights in

a manner that prejudices those rights. The NYSE and the appellee could not, for

example, require employees to waive their right to the substantive protections of Title

VII as a condition of obtaining or keeping their jobs. There can be no advance

waivers of statutory rights. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 51

(1974). The same principle necessarily bars the imposition of procedural

requirements having the effect of waiving statutory rights.

Congress has demonstrated its concern with the protection of relatively weak

and impecunious applicants and employees against the overwhelming economic

power of employers, through the enactment in Title VII of provisions providing for

the award of attorneys’ fees and costs to the prevailing party and providing for the

appointment of counsel to represent the complainant in court. It is simply not

- 1 5 -

conceivable that Congress would have looked with equanimity on employers

engaging in “stealth” repeals of the fair employment laws.

The duty of fair representation cases present another useful analogy. The

Railway Labor Act and the National Labor Relations Act provide that a duly certified

collective bargaining representative is the exclusive bargaining representative of the

employees in the collective bargaining unit. Groups of employees within the

bargaining unit do not have the freedom to engage in their own bargaining about

issues of concern to them, even issues of concern involving their civil rights.

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community Organization, 420 U.S. 50

(1975). The unions enjoying such publicly enforced exclusive authority have a

concomitant obligation to treat their members fairly, and not to discriminate

arbitrarily against any member or group of members. Steele v. Louisville & Nashville

R. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944), and Tunstall v. Bhd. o f Locomotive Firemen, 323 U.S.

210 (1944), held that unions exercising such exclusive power under color of statute

are subject to the duty of fair representation.

This principle is as ancient as the Constitution. Power must not be given by

a governmental body unless it is accompanied by responsibility. Grants of great

power require the exercise of great responsibility. Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171, 190

- 1 6 -

(1967), held that a union breaches its duty of fair representation “only when a union’s

conduct toward a member of the collective bargaining unit is arbitraiy,

discriminatory, or in bad faith.” The Court held that a union may breach its duty if

it ignores a meritorious grievance or processes it in a perfunctory manner. Id. at 191.

We submit that the same standard must be applied in arbitration cases in which either

the employer or a third party are using governmental coercion to force employees to

arbitrate their claims of discrimination.

From this standpoint as well, the district court was under an obligation, which

it did not meet, to assess the fairness of the NYSE procedures as they have actually

been applied.

B. The Record Herein Raises Serious Due Process Concerns, Which the

District Court Did Not Adequately Address

Amici do not argue that the securities industry cannot develop a program of

arbitration that will pass muster under the standards of due process. We argue merely

that the industry has not yet done so, and that due process does not allow the

enforcement of the NYSE arbitration procedures until the industry has done so.

1. Compelling Victims to Use Procedures Violating Due

Process Is Likely to Chill the Willingness of Victims to

Assert Their Rights

- 1 7 -

The defendant’s argument that the NYSE procedures are entitled to a

presumption of fairness would be correct if there were no contrary factual record;

Gilmer followed just this approach. In the strong light of plaintiffs contrary

evidence, however, any such presumption has been rebutted.

Moreover, the threat of being compelled to submit to these procedures

inevitably has a chilling effect on the victims of civil rights violations. Instead of

enjoying the protections Congress meant them to enjoy, they have little alternative but

to “grin and bear it” or to leave their jobs and go to work in an industry where such

procedures are not used and they can once again enjoy the protections of the law. The

threat of a chilling effect is substantial, and will grow more substantial over time as

more and more victims become aware of the types of problems shown by the record

herein. In a free society, this type of information must inevitably become known over

time. The WALL STREET JOURNAL’S June 9, 1994, page-one article, M en’s Club:

Riding Crops and Slurs: How Wall Street Dealt with a Sex Bias Case, by Margaret

Jacobs, has already enlightened many victims and attorneys, and the experiences of

many victims with meritorious claims, who were victimized once again in unfair

arbitrations, are inevitably passed on widely to other women, minorities, and older

employees.

1 8 -

The victims of employment discrimination and their attorneys simply cannot

be presumed to be so unaware of reality that they do not now have-—and will never

in the future have—-any idea of the extent to which the NYSE procedures stack the

deck against them. The fundamental unfairness of arbitration in the securities

industry is widely known among civil rights organizations and among a growing

number of plaintiffs’ attorneys. Based on the experience of amici, this situation will

certainly chill the willingness of victims to press meritorious claims. Unfair

arbitration procedures actually have the capability of resulting in what is in effect a

unilateral, partial repeal of essential civil rights protections. This is why plaintiff s

evidence of the procedures actually followed is critically important.

2. The District Court Erroneously Ignored Plaintiffs

Evidence that the Actual Application of NYSE

Procedures Results in Violations of Due Process

The district court did not seriously consider plaintiff s well-supported showing

of due process violations in the NYSE procedures. First, it seems to have believed

that Gilmer had blessed “the very same NYSE arbitration procedures at issue in the

present case.” August 26, 1996, Order at 14, C.R. 68. To the contrary, the Supreme

Court had made clear that there was no record in Gilmer supporting any of the

challenges, and that it would not assume in the absence of a record that the NYSE

- 1 9 -

procedures would be inadequate “to guard against potential bias,” 500 U.S. at 31, or

that the discovery provisions “will prove insufficient to allow ADEA claimants such

as Gilmer a fair opportunity to present their claims,” id. at 31, or that the awards

would be too cursory to permit effective judicial review, id. at 32 n.4.

If the evidence in the case at bar had been before the Supreme Court in Gilmer,

the Court would have been hard-pressed to reach the same result. The Court’s

acceptance of arbitration as an enforceable alternative to judicial enforcement has

always been explicitly dependent on the concept that all that is changed is the forum,

the extent of discovery, and the strictness of the rules of evidence. “In these cases we

recognized that ‘ [b]y agreeing to arbitrate a statutory claim, a party does not forgo the

substantive rights afforded by the statute; it only submits to their resolution in an

arbitral, rather than a judicial, forum..’” Id. at 26, quoting Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v.

Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc.,473 U.S. 614, 628 (1985). This concept simply cannot

be squared with the instruction in THE ARBITRATOR’S MANUAL (Securities Industry

Conference on Arbitration, plaintiffs exhibit 1 to the Masucci deposition, Exhibit A

to the November 2, 1995, Declaration of Michael Rubin, CR 33) at 26:

Arbitrators are not strictly bound by case precedent or statutory

law. Rather, they are guided in their analysis by the underlying policies

of the law and are given wide latitude in their interpretation of legal

- 2 0

concepts. On the other hand, if an arbitrator manifestly disregards the

law, an award may be vacated.

The MANUAL goes on to state that an arbitrator is not required to give a reason for the

decision. Id. at 30. The arbitration awards attached to plaintiff s summary-judgment

declaration demonstrate that the NYSE arbitrators as a rule do not provide such

reasons. In the ordinary case, therefore, there is no possibility of meaningful judicial

review or of the growth of arbitral precedent. Astronomers have informed us that

“black holes” are so massive that not even light can escape their gravity, and

astronomers are therefore deprived of any direct information on how such phenomena

operate. All we know about “black holes” is what we can learn from their secondary

effects on objects near them. The same can be said about the NYSE arbitration

awards: the absence of reasoned written decisions means that no light can penetrate

into the process and reveal whatever reasoning may have been used by the arbitrators;

we can see only the secondary effects revealed by this record.

The statements in the MANUAL cannot fairly be construed in the rosy glow of

defendants’ protestations of good faith and innocence; they were intended for laymen

and women— most of whom are present or former employees of the securities

industry— and must be given the same construction the intended recipients would

-21 -

take from this language: an arbitrator can substitute his or her own judgment of what

is right and wrong, based on his or her personal understandings of the policies of the

fair employment laws, as long as he or she is not too obvious about it, and that the

arbitrator’s substitution of his or her own personal morality or beliefs for the letter of

the enactments of Congress and for judicial constructions of those enactments can be

concealed by the simple expedient of giving no reasons for the decision.

Moreover, the plaintiff made a well-supported showing that arbitrators are not

required to submit to training as to the meaning or application of the fair employment

laws, or of the policies underlying them, and that there is no effort to ensure that at

least one arbitrator know anything about the fair employment laws. Thus, the

arbitrator’s officially-authorized substitution of his or her judgment for the law can

be based on notions of “underlying policies” that are totally unlinked to reality. This

is neither more nor less than a power to negate or revise the commands of the law, in

an ad hoc manner for which the arbitrator will never be accountable.

If the school desegregation cases had been decided on such a basis by

arbitrators chosen from among the present and former principals and teachers in

segregated schools, can anyone reasonably doubt that de jure segregation would still

be the law of the land? Similarly, if sexual harassment cases against brokers are

- 2 2 -

decided by present or former fellow brokers on such a basis, can anyone reasonably

doubt that sexual harassment in brokerage firms will continue unabated?

In the absence of any record suggesting otherwise, Gilmer presumed that

“competent, conscientious” arbitrators would be available. 500 U.S. at 30, quoting

Mitsubishi, 473 U.S. at 634. Here, the record shows that the NYSE has chosen to

allow the use of arbitrators who have declined to study the fair employment laws. In

logic, it is hard to consider such arbitrators as either competent or conscientious.

Nevertheless, the NYSE procedures allow arbitrators, who are not conscientious

enough to acquire competence by studying the fair employment laws, to exercise the

powers of negation and revision of these laws.

The undisputed fact that arbitration panels have the freedom to visit heavy

forum fees on complainants whether or not they succeed on their claims presents

additional due process problems. The Supreme Court has held that conditioning the

right to appellate review of a criminal conviction on the defendant’s ability to pay for

a trial transcript violates the due process and equal protection rights of indigent

defendants, Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956), that even a $60 fee for filing a

divorce action is an unconstitutional denial of due process to an indigent claimant

who has no recourse but to use the procedure subject to the fee, Boddie v.

2 3 -

Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971), that a double-bond requirement for tenants seeking

to appeal adverse decisions in eviction actions violated the equal protection clause,

Lindsey v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 (1972), and that a $250 fee for obtaining a blood

grouping test is an unconstitutional denial of due process to an indigent defendant in

a paternity case who might be exonerated by the test, Little v. Streater, 452 U.S. 1,

14 n.10, 17 (1981). Distinguishing these cases, Kadrmas v. Dickinson Public

Schools, 487 U.S. 450, 460 (1988), stated that “each involved a rule that barred

indigent litigants from using the judicial process in circumstances where they had no

alternative to that process.” Just this past Term, the Court reiterated these principles

in M.L.B. v. S.L.J.,__U .S .__ , 117 S. Ct. 555 (1996), holding that a State may not

condition an aggrieved parent’s appeal from a decision terminating his or her parental

rights on his or her ability to pay record preparation fees. This line of cases does not

cover the broad run of civil litigation, and is less likely to be applied as the rights in

question are less fundamental, as more alternatives to public adjudication exist, and

as the amount in question becomes smaller. Ortwein v. Schwab, 410 U.S. 656 (1973)

(upholding an Oregon statute requiring civil appellants to pay a $25 fee); United

States v. Kras, 409 U.S. 434 (1973) (upholding a $50 fee for obtaining a discharge

in bankruptcy).

- 2 4

Here, we are dealing with rights Congress considered of the highest national

importance. It has described plaintiffs in civil rights cases as private attorneys

general. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). Sec.

706(f)(1) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(l), provides for the waiver of filing

fees and the appointment of counsel in appropriate cases. Congress has clearly made

the judgment that the rights at stake are similar to the rights at stake in Griffin,

Boddie, and their progeny.

Sexual harassment plaintiffs are often women in relatively low-paid jobs; when

they are directed to pay an unaffordable deposit of over a thousand dollars for future

forum fees, with an unlimited1 further amount in store, it is obvious that they will

simply drop their claims.2 It is also obvious that victims of discrimination, aware

from office scuttlebutt of the immense fees they may eventually have to pay even i f

they prevail, will simply be discouraged from even filing a claim in the first place.

In a different context, the Supreme Court has recognized the reality that victims can

1 While the parties agree that the largest forum fee imposed on a prevailing

complainant was $82,000, that is, like sports records, only a temporary ceiling.

2 Shankle v. B—G Maintenance Management, 74 FEP Cases 94, 96 (D. Colo.

1997), stated that the requirement that the plaintiff bear responsibility for one-half

of the arbitrators’ fees “operates as a disincentive to his submitting a

discrimination claim to arbitration.”

- 2 5 -

be discouraged from taking action—there, from applying for work when the employer

has a reputation for discrimination and the application would have been futile— and

has held that the courts have an obligation to provide relief, where possible, for even

the discouraged victims. In t’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324,

366-67 (1977).

Amici recognize that the plaintiff in this case is not low-paid. Perhaps no low-

paid plaintiff could ever obtain the counsel who would invest the time and resources

necessary to pull together the record herein; if so, this Court will never have a case

in which a low-paid plaintiff could present these important questions. The plaintiff

here is injured by the imposition of high forum fees, and this Court’s ruling will be

applied to women and members of minority groups who are low-paid. It is critical

that this problem be addressed in this case.

The only Circuit to address this issue to date has held that otherwise valid

arbitration agreements are not enforceable if they require complainants to pay fees

beyond the types of filing fees they would have to pay in court, or that require any

fees not subject to ready waiver in the case of financial hardship. Cole v. Burns Int 7

Security Services, 105 F.3d 1465, 1483—84 (D.C. Cir. 1997). There, the court

construed an ambiguous provision as requiring the employer to pay the forum fees,

- 2 6 -

in order to save the agreement. Id. at 1485-86. There is no such ambiguity here.

Cole also held that arbitration was inappropriate for statutory discrimination

claims unless there is judicial review “sufficiently rigorous to ensure that arbitrators

have properly interpreted and applied statutory law.” Id. at 1487. No such review is

possible under the NYSE procedures that allow covert rationales and never require

the true basis for the decision to see the light of day. In passing, amici must note that

Cole vastly overstates the role of purely factual determinations in employment

discrimination cases; most cases are actually decided on mixed questions of law and

fact. Findings of fact, themselves entitled to deference just as are judicial findings

and jury determinations, are essential to any determination whether the arbitrators

have correctly applied the law.

Finally, the routine denial of arbitral awards of attorneys’ fees to prevailing

complainants is yet another departure from the substantive protections of the civil

rights laws. The negative wording of THE ARBITRATOR’S MANUAL on awards of fees,

like its negative wording on compensatoiy damages and failure to mention damages

for the humiliation of discrimination, virtually guarantee that arbitral panels will

routinely deny such relief. Again, this negates the intent of Congress. Congress has

decided that successful claimants should not have to bear their own fees, and enacted

2 7 -

fee-award provisions designed to assist persons with meritorious claims to obtain

capable counsel. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. at 401-02

(public accommodations case under Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). The

Supreme Court has construed Title VII’s fee provision as meaning that “a prevailing

plaintiff ordinarily is to be awarded attorney’s fees in all but special circumstances,”

while awards to prevailing defendants are tightly limited, Christians burg Garment

Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412, 417, 421-22 (1978) (emphasis omitted), but the MANUAL

makes no recognition of the Supreme Court’s dual standard and seems to presume

that no fees should be awarded to either side.

The district court erred in failing to address these problems. Its conclusory

finding of adequacy of the NYSE procedures is too cursory in light of this record to

permit meaningful review. Moreover, without an evidentiary hearing, the district

court lacked the power to resolve disputed questions of fact. Cf. Oldham v. West, 47

F.3d 985, 988-89 (8th Cir. 1995) (reversing the grant of summary judgment because

the lower court had impermissibly decided factual issues without an evidentiary

hearing); Tomsic v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., 85 F.3d 1472,

1478 (10th Cir. 1996) (reversing the grant of summary judgment because the district

court impermissibly drew inferences from disputed evidence).

- 2 8 -

C. The Legislative History of § 118 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991

Makes Clear that Mandatory Pre-Dispute Arbitration Provisions

Are Not an Appropriate Means of Enforcing the Statute

Congress set its face against the extracted surrender of the right to bring future

Title VII claims to the public authorities in enacting § 118 of the Civil Rights Act of

1991. That section “encourages” the use of arbitration to resolve civil rights claims

where “appropriate.” But the legislative history makes explicit that a pre-dispute

commitment to arbitrate, extracted as a condition of employment, is not appropriate

within the meaning of the statute.

The text of § 118 appeared verbatim in the proposed Civil Rights Act of 1990,

which was adopted by both houses of Congress prior to the veto requiring another

year of legislative activity before its eventual enactment. The Conference Report, in

explaining the effect of the provision, stated: “any agreement to submit disputed

issues to arbitration . . . in an employment contract, does not preclude the affected

person from seeking relief under the enforcement provisions of Title VII.”3 President

Bush vetoed the bill because he was dissatisfied with its other provisions. The bill

was reintroduced in 1991 with changes in those other provisions, but with § 118

3 H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 755, 101st Cong., 2d Sess. 26 (1990) (emphasis added).

The provision was Section 18 in that bill.

- 2 9 -

intact.

The two Committee reports in the House in 1991 repeated this same

explanation of § 118.4 (There were no Committee reports in the Senate in 1991). In

the debate just prior to enactment of the 1991 bill, Rep. Edwards explained: “The

section contemplates the use of voluntary arbitration to resolve specific disputes after

they have arisen, not coercive attempts to force employees in advance to forego

statutory rights.”5 Not a single member of Congress voiced the contrary view, viz,

that the bill would permit preclusive effect to be given to pre-dispute agreements

extracted as a condition of employment. Indeed, the “dissenting” members of the

House Judiciary Committee, led by Representative Hyde, lamented that § 118 is

“nothing but an empty promise” to those who had sought a greater substitution of

arbitration for litigation.6

The lower court proceeded without even considering the meaning and effect

4 H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part I, 102d Cong., 1st Sess. 97 (1991) (House

Education and Labor Committee); H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part II, 102d Cong., 1st

Sess. 41 (1991) (House Judiciary Committee). The provision was § 216 in the bill

as reported by the first committee, and § 18 in the bill as reported by the second.

5 137 Cong. Rec. H9526, 9530 (daily ed., Nov. 7, 1991).

6 H.R. Rep. No. 102-40, Part II, supra, at 52, 78.

- 3 0 -

of Title VII in this regard. That, we submit, was clear error with the gravest

consequences. A great deal of legislative effort was expended in the effort to expand

the remedies for intentional violations of Title VII and to provide the right to a jury

trial. While a truly voluntary post-dispute agreement to arbitrate the dispute under

a fair procedure meeting the standards of due process is consistent with § 118 and

should be respected, a coerced “agreement” is neither voluntary nor consistent with

§118. As the EEOC has concluded, such an “agreement” violates Title VII.

- 3 1 -

Conclusion

For the reasons stated above, amici pray that this Court reverse the decision

below and remand the case for trial on the merits.

Respectfully submitted,

THOMAS J. HENDERSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

TERESA A. FERRANTE

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

1450 G Street N.W., Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8600 (202) 783-5131 (fax)

EVA JEFFERSON PATERSON

San Francisco Lawyers’ Committee for Urban Affairs

301 Mission Street, Suite 400

San Francisco, California 94105

(415) 543-9444 (415) 543-0296 (fax)

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

THEODORE M. SHAW

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900 (212) 226-7592 (fax)

- 3 2 -

JUDITH L. LICHTMAN

DONNA R. LENHOFF

HELEN L. NORTON

Women’s Legal Defense Fund

1875 Connecticut Avenue N.W., Suite 710

Washington, D.C. 20009

(202) 986-2600 (202) 986-2539 (fax)

Dated: August 7, 1997

- 3 3 -

Certificate of Service

I certify that I have this 7th day of August, 1997, served two copies of this brief

on all counsel of record herein, by depositing them in the U.S. Mail, first-class

postage prepaid, addressed as follows:

Michael Rubin, Esq.

Jeffrey B. Demain, Esq.

Altshuler, Berzon, Nussbaum, Berzon & Rubin

177 Post Street

Suite 300

San Francisco, California 94108

Cliff Palefsky, Esq.

McGuinn, Hillsman & Palefsky

535 Pacific Avenue

San Francisco, California 94133

F. Curt Kirschner, Esq.

David B. Newdorf, Esq.

O’Melveny & Myers LLP

275 Battery Street

San Francisco, California 94111

Robert J. Gregory, Esq.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Office of the General Counsel, Appellate Services Division

1801 L Street N.W.

Room 7032

Washington, D.C. 20507