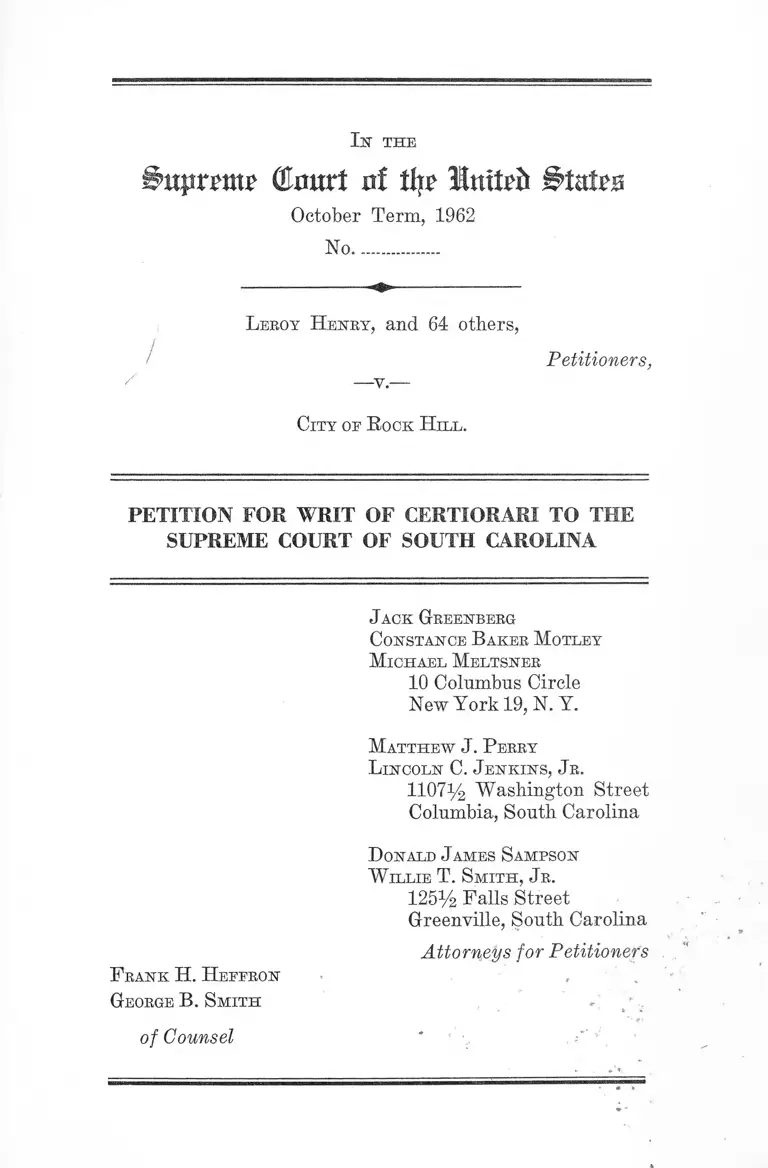

Henry v. City of Rock Hill Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. City of Rock Hill Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1962. 1252abff-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d6e51419-cf4f-4fc2-bd40-ac7c013899c5/henry-v-city-of-rock-hill-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(Emtrt nf % Imtpft Btnlza

October Term, 1962

No................

/

L eboy H enry, and 64 others,

— v . —

City op R ock H ill.

Petitioners,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

F rank H. H eefron

George B. Smith

of Counsel

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Matthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

D onald J ames Sampson

W illie T. Sm ith , J r.

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinions Below .....-..................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Questions Presented .... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ................................ 2

Statement ........................................................................ 2

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided 5

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................................... 8

I. Edwards v. South Carolina Requires Reversal

Since the Facts Here Are Almost Identical to

Those of That Case, Petitioners Having Been

Convicted of South Carolina’s Vague Crime of

Common Law Breach of the Peace While As

serting Rights of Free Speech and Assembly

Secured by the Fourteenth Amendment .......... 8

II. The Convictions of the Petitioners for Breach

of Peace Violate the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment in That They Rest on No

Evidence of Public Disorder, Disturbance, or

Violence, Actual or Threatened ......................... 11

Conclusion ...................................................................... 13

Appendix ......................... -........................... - ............... la

Order of the York County Court................................... la

11

PAGE

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina ...... 4a

Denial of Petition for Rehearing ................................ 7a

Table of Cases

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ....:................... 9

Dejonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ................................ 9

Edwards v. South Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week 4225 —.2, 6, 8,

9,10,11

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 ............................... 12

Gitlow y. New York, 268 U. S. 652 ................................ 9

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 9

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154................................ 12

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ......................... 12

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ............................ 9

I n the

Ihtprtfm? (to rt nf % Inttrft ^ ta te

October Term, 1962

No................

L ekoy H enby, and 64 others,

Petitioners,

City oe R ock H ill.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

entered in the above entitled case on December 7, 1962,

rehearing of which was denied on January 3, 1963.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina is

reported at 128 S. E. 2d 775 and is set forth in the appendix

hereto, infra, pp. 4a-6a. The Order of the York County

Court is unreported and is set forth in the appendix hereto,

infra, pp. la-3a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered on December 7, 1962, infra, pp. 4a-6a. Petition

for rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on January 3, 1963, infra, p. 7a.

2

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below and claiming here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether the arrests and convictions of the petitioners

under South Carolina’s vague common law concept of breach

of the peace denied their rights of free expression secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment where the facts are almost

identical to those of Edwards v. South Carolina decided by

this Court on February 25,1963?

2. Whether petitioners were denied due process of law

by their conviction for common law breach of the peace on

a record devoid of evidence of any of the essential elements

of the crime ?

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

Petitioners, sixty-five Negro students, were arrested in

two groups on March 15, 1960 in front of the City Hall

of Eock Hill, South Carolina and charged with common

law breach of the peace. The warrant (E. 2) stated that the

petitioners “did willfully and unlawfully commit a breach

of the peace by assembling with others in a large group

upon the public streets, singing in a loud, boisterous, and

3

tumultuous manner and refusing to disperse upon order of

a police officer contrary to the peace and dignity of the State

of South Carolina, and in violation of the ordinances of

the City of Bock Hill.”

Petitioner Henry was tried and convicted on March 24,

1960. The other petitioners appeared in several groups in

the Recorder’s Court of the City of Bock Hill on March

31st, 1960, April 7th, April 14th, April 21st, April 28th,

1960, May 5th and May 26th, 1960 (R. 1). Upon the ap

pearance of each group it was stipulated that the testimony

in the trial of Leroy Henry was applicable to and incorpo

rated by reference into the remaining trials (B. 1, 192).

All of the petitioners were found guilty and sentenced to

pay fines of thirty-five to forty-five dollars or to serve

thirty days in prison (B. 1).

The cases were heard on appeal to the York County

Court by the Honorable George T. Gregory, Jr. On Decem

ber 29, 1961, Judge Gregory issued an Order affirming the

convictions (B. 193).

On December 7, 1962 the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina affirmed the convictions. Rehearing was denied on

January 3,1963.

A. The First Group

On March 15, 1960 around 1 :00 P. M. (R. 40, 118) sixty

Negro students gathered near the curb (R. 126) in front

of the City Hall of Rock Hill, South Carolina to protest

against racial segregation (R. 115,150,151,192). They sang

several songs—The National Anthem, My Country ’Tis of

Thee, God Bless America, What a Friend We Have in Jesus,

and America The Beautiful (R. 20, 91, 113). Some of the

petitioners carried signs (R. 44). After approximately 15

minutes a police officer asked the leader of the group to

4

tell the students to disperse (E. 95). When they did not,

he arrested them (E. 95).

The arresting officer, Lt. J. B. Brown, testified that he

arrested petitioners “in view of the public peace,” and be

cause there was immediate danger to the public peace

(E. 92).

The arresting officer testified that the petitioners were

singing in a “loud tone of voice” (E. 91). Another officer

said that they sang in a “loud, boisterous manner” (E. 20).

But the singing was described by the defendant’s witnesses

as “very moderate” in tone (E. 145), low in volume (E. 147),

and “in a very sweet, soft voice” (E. 166).

A car horn which was blowing could be heard distinctly

above the singing (E. 125) which seemingly grew louder

because of the horn (E. 92, 107). No complaints were made

about the singing or any other of petitioners’ actions, by

persons within the City Hall or onlookers (E. 64, 65).

There was no evidence that the petitioners’ conduct or

the onlookers’ threatened the public peace. While there

was testimony that work was disrupted by the singing

(E. 41, 62, 119), no complaint about this was made (E. 64,

65). Petitioners were not profane, insulting, discourteous,

or anything of the kind (E, 63). The white onlookers “were

just standing there to see what was going to happen”

(E. 71). Five policemen were at the scene, and there is no

evidence that more were called for or needed to control

the situation (E. 108,109).

No white persons were arrested nor was any attempt

made to arrest any, even though some were blowing horns

and others did not disperse when ordered to (E. 68, 71,

106,107,109,110).

5

Petitioners were on the sidewalk in front of City Hall

and did not prevent anyone from passing (E. 20, 41, 55,

57, 126). Nor did they block vehicular traffic (R. 126). The

white onlookers on the other side of the street did not block

traffic or pedestrians (E. 66). When some of the onlookers

spilled out onto the street they were moved back with no

trouble (R. 66, 67, 68). One of the state’s witnesses who

testified that cars could not pass (E. 120), testified that

the students did not block traffic (R. 126). Nor were per

sons prevented from using parking meters (E. 56). Traffic

was cut out of Hampton Street which is located in front of

City Hall only around the time the arrests were made

(E. 67).

B. The Second Group

The second group consisted of five persons who appar

ently arrived after the others had been arrested. They

acted in much the same manner as the first group, singing

patriotic and religious songs (E. 43, 96), but apparently

for less time than the first group. Police asked them to

leave and when they refused, they were arrested; at this

time the street was fairly clear of citizens (R. 96).

No ordinance requires a permit to sing in front of City

Hall (E. S3).

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

Before the commencement of the trial defendants made

a motion to quash the information and dismiss the war

rants on the ground that they were vague, indefinite, and

uncertain (E. 6, 7). The motion was denied (R. 8, 18, 19).

At the close of the prosecution’s case, a motion to dis

miss the warrants was made on the grounds that the Four

6

teenth Amendment had been violated in that there was no

evidence showing a breach of the peace by the defendants

(R. 141), and that the defendants were asserting rights of

freedom of speech and assembly. The motion was over

ruled (R. 143).

At the close of the defendant’s case, defendant renewed

his motion to dismiss on grounds previously given (R. 188).

The motion was overruled (R. 189).

After the verdict defendants moved for a new trial based

on all the objections raised during the course of the pro

ceedings (R. 189). The motion was overruled (R. 189).

In affirming the convictions, the York County Court,

relied on Edwards v. South Carolina (R. 194), 123 S. E.

2d 247, reversed, 31 U. S. L. Week 4225, and stated that

all the legal objections had been properly overruled.

In their appeal to the South Carolina Supreme Court de

fendants in the following exceptions contended that the

Fourteenth Amendment had been violated because of the

vagueness of the charge, the right of freedom of expression

and the lack of any evidence to convict (R. 196):

1. “The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

warrants are vague, indefinite and uncertain and do

not plainly and substantially set forth the offense

charged, thus failing to provide appellants with suf

ficient information to meet the charge against them

as is required by Article I, Section 16, Constitution of

the State of South Carolina and in violation of appel

lants’ rights to due process of law, secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.”

# # * * *

6. “The Court erred in refusing to hold that appellants

were convicted upon a record devoid of any evidence

of the commission of any of the essential elements of

7

the crime charged, in violation of appellants’ rights

to dne process of law, guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, and by

Article I, Section 5, Constitution of the State of South

Carolina.”

# # # # #

8. “The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

evidence shows conclusively that by the arrest and

conviction of appellants the State of South Carolina

used its police powers to deprive appellants of the

right of freedom of assembly and the right of freedom

of speech, guaranteed them by the First Amendment

to the United States Constitution, and further secured

to them under the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.”

The South Carolina Supreme Court held that there was

ample evidence to support the conclusion that the police

acted in good faith, dismissed all the exceptions and af

firmed the convictions, infra, p. 6a.

8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Edwards v. South Carolina Requires Reversal Since

the Facts Here Are Almost Identical to Those of That

Case, Petitioners Having Been Convicted of South Caro

lina’s Vague Crime of Common Law Breach of the Peace

While Asserting Rights of Free Speech and Assembly

Secured by the Fourteenth Amendment,

In Edwards v. South Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week 4225,

decided February 25, 1963, this Court decided that the

arrest and conviction of Negro students under South Caro

lina’s vague concept of breach of the peace, while they

were peacefully protesting against racial segregation, vio

lated their rights of freedom of expression and petition

for redress of grievances secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In this case, decided by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on December 7, 1962, subsequent to that court’s

decision in Edwards and before this Court’s decision re

versing it, Negro students also assembled to protest against

racial segregation (R. 115, 150, 151, 192), this time in front

of the City Hall of Rock Hill, South Carolina. Review of

the facts and circumstances in each case demonstrates that

the arrests and convictions of the students here were, if

anything, even more unjustifiable than those in Edtvards.1

One hundred eighty-seven persons assembled in Edwards;

sixty-five were present here. The Negro students in Ed

wards registered their protest by marching, singing, and

carrying placards. The two groups arrested here limited

themselves to singing and carrying placards (R. 20, 44,

91, 113). While the students in Edwards demonstrated

forty-five minutes to an hour, the first group here dem

1 The following references to Edwards are taken from the opin

ion of the court, 31 IT. S. L. Week 4225 and 4226.

9

onstrated fifteen to thirty minutes, and the second group

for a shorter period (R. 44, 95). Nor was there any clapping

of hands, stamping of feet, or “religious harangue” like

that found in Edwards.

In both cases the crowd could only be described as

curious. In Edwards the onlookers numbered two hundred

to three hundred persons while here there were one hundred

and fifty “at the greatest gathering” when the first group

was singing (R. 66). When the second group was arrested,

“the street was fairly clear as far as citizens were con

cerned . . . ” (R. 96). There was testimony in Edwards

by the city manager that “possible troublemakers” were

present in the crowd, but similar evidence is lacking here.

Police officers were at the scene and in control in both

cases, thirty being present in Edwards, five or six here

(R. 108,109).

No disruption of traffic can be found in either case. Even

the slowing down of traffic which occurred in Edwards is

missing here.

What was said by this Court in Edwards, 31 U. S. L.

Week 4227 is equally true here,

“It has long been established that these First Amend

ment freedoms are protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment from invasion by the States. Gitlow v. Neiv York,

268 U. S. 652; Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357;

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359; DeJonge v.

Oregon, 299 U. S. 353; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

U. S. 296. The circumstances in this case reflect an

exercise of these basic constitutional rights in their

most pristine and classic form.”

Moreover if singing before the City Hall of Rock Hill in

protest against racial segregation is enough to arrest and

10

convict these petitioners, South Carolina’s use of common

law breach of the peace is subject to the vice of vagueness.

No ordinance or statute prevented petitioners from singing

in front of City Hall (R. 83). Thus this Court is not asked

to review “criminal convictions resulting from the even-

handed application of a precise and narrowly drawn regu

latory statute evincing a legislative judgment that certain

specific conduct be limited or proscribed.” Edwards v.

South Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week at 4227. The South Caro

lina Supreme Court in this case defined breach of the peace,

as it did in Edwards, in this way (infra, p. 5a):

“ ‘In general terms, a breach of the peace is a viola

tion of public order, a disturbance of the public tran

quility, by any act or conduct inciting to violence . . .,

it includes any violation of any law enacted to preserve

peace and good order. It may consist of an act of vio

lence. It is not necessary that the peace be actually

broken to lay the foundation for a prosecution for this

offense. If what is done is unjustifiable and unlawful,

tending with sufficient directness to break the peace,

no more is required. Nor is actual personal violence

an essential element in the offense . . . ’ ”

This Court rejected such a vague definition as insuffi

cient to convict persons engaged in the exercise of rights of

freedom of speech and expression holding:

“These petitioners were convicted of an offense so gen

eralized as to be, in the words of the South Carolina

Supreme Court, ‘not susceptible of exact definition.’

And they were convicted upon evidence which showed

no more than that the opinions which they were peace

ably expressing were sufficiently opposed to the views

of the majority of the community to attract a crowd

11

and necessitate police protection.” Edwards v. South

Carolina, 31 U. S. L. Week 4227.

Certiorari should be granted because the opinion of the

Supreme Court of South Carolina is in direct conflict with

this Court’s decision in Edwards. These petitioners, like

those in Edwards, were asserting rights of free expression

which South Carolina has abridged by means of a crime

so vaguely defined as to be repugnant to the Fourteenth

Amendment.2

II.

The Convictions of the Petitioners for Breach of

Peace Violate the Dee Process Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment in That They Rest on No Evidence

of Public Disorder, Disturbance, or Violence, Actual or

Threatened.

Even under South Carolina’s amorphous definition of

breach of the peace there is no evidence to support the

petitioners’ convictions. The testimony of the police was

that petitioners were well mannered (R. 63). The onlookers

made no move actual or threatened which suggested that

they were hostile to the petitioners. They made no com

plaints (R. 64, 65). They “were just standing there to see

what was going to happen” (R. 71). Moreover, none were

arrested by the police (R. 68, 71, 109, 110). The situation

was so controlled that only five policemen were at the scene

and no more were called to control the students and the

crowd (R. 108,109). * 18

2 Moreover, petitioners respectfully submit that since the legal

and factual issues here are essentially the same as those found in

Fields v. South Carolina, 31 U.S.L. Week 3297, decided on March

18, 1963, the same disposition made in that case should be made

in this.

12

There was no disruption of traffic since it was able to

move freely both on the sidewalk and in the streets (R.

41, 55, 56, 57, 66, 67, 68, 126). One street was blocked

off only around the time the arrests were made (R. 67).

There is testimony that some of the drivers blew their

horns (R. 92, 106,107, 125). But the arresting officer stated

that this lasted only a matter of seconds (R. I l l ) , nor

were any arrests made of persons blowing horns (R. 109).

There was testimony of police officers and a city em

ployee who helped take petitioners to jail that the singing

was loud and work was disrupted (R. 20, 21, 62, 91, 119,

125). But the singing was not loud enough nor work dis

rupted enough to cause any complaints to be made (R. 64,

65). The onlookers, both on the sidewalk and in the build

ings, can only be termed willing listeners. Even the testi

mony of the police was that petitioners were orderly,

courteous, and polite (R. 63).

Certiorari should be granted and the decision below re

versed for the additional reason that due process of law

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment was denied in that

there was no evidence to sustain the convictions. Thompson

v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157, Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. 8. 154.

13

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted that the petition for writ of certiorari should

be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Matthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Donald J ames Sampson

W illie T. Smith , J r.

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

F rank H. H eefron

George B. Smith

of Counsel

APPENDIX

A P P E N D I X

I n the

YORK COUNTY COURT

T he City of R ock H ill

-v.-

L eroy H enry, et al.

Order

This Court now has before it for consideration a total

of seventy-one cases which were heard by the Recorder’s

Court for the City of Rock Hill. The convictions of all

defendants were in due time appealed to this Court and

heard together by this Court on an agreed Transcript of

Record. By occurrence and charge the cases are grouped

as follows:

1. Sixty-five breach of peace charges, upon the public

streets at City Hall, on March 15, 1960.

2. Three breach of peace charges, upon the public streets

at Tollison-Neal Drug Store, on February 23, 1961.

3. One Trespass charge within McCrory’s variety store,

on April 1, 1960, before enactment of the 1960 Trespass

Act (No. 743). 4

4. Two Trespass charges, wfithin McCrory’s variety

store on June 7, 1960, after enactment of the 1960 Trespass

Act.

2a

An examination of the Transcript of Record on Appeal

discloses no real distinction between the first sixty breach

of peace cases at City Hall, the next five on the same day

at the same place only a short time later, and the three

breach of peace cases on the public streets at Tollison-

Neal Drug Store. In all of these cases it appears from

the record that the public peace was endangered, that the

defendants were properly forewarned by a police officer

to cease and desist from further demonstrations at that

time and place, and move on, which they failed and re

fused to do, despite allowance of ample time within which

to have complied with the order, and that thereafter they

were arrested and charged with breach of peace as con

tinuance of their activities under the circumstances then

existing, as shown by the record, constituted open defiance

of proper and reasonable orders of a police officer and

tended with sufficient directness to breach the public peace.

The offense charged in each of the sixty-eight breach of

peace cases is clearly made out under the facts shown by

the Transcript of Record and the law of force in this state,

particularly as the law is shown by the recent decision of

the South Carolina Supreme Court in the case of State v.

Edwards et al., Opinion No. 17853, filed December 5, 1961.

In like manner this Court finds no distinguishing fea

tures between the one trespass case, which occurred at

one time and place and the two later trespass cases at

the same place. In all three cases each defendant was asked

to leave the premises by the Manager of the store, this

occurred in the presence of a City police officer, who then

himself requested each defendant to leave and explained

that arrest would follow upon failure to leave. After each

defendant failed to leave the private premises involved,

following allowance of a reasonable opportunity after re

quest so to do, first by the Manager and then by the police

officer, each defendant was arrested and charged with tres

pass. Here again, under the facts disclosed in the record

3a

and the law of force in this state, the charge of trespass

is properly made out as to each defendant. See City of

Greenville v. Peterson et al., S. C. Supreme Court Opinion

No. 17845, filed November 10, 1961 and City of Charleston

v. Mitchell et al., S. C. Supreme Court Opinion No. 17856,

filed December 13, 1961.

A number of specific legal questions were raised by the

Defendants, including particularly a question as to ade

quacy and sufficient (sic) of the warrants and whether or

not the Defendants were properly advised of the charges

pending against them. An examination of the warrants

discloses that in each case the facts constituting the of

fense charged were stated with reasonable and sufficient

particularity. It is the opinion of this Court that the va

rious legal objections raised in the court below, which are

not set forth in detail herein, were properly overruled.

See State v. Randolph et al., 239 S. C. 79, 121 S. E. (2d)

349, filed August 23, 1961, other authorities cited herein,

and other applicable decisions of our Courts referred to

in the cited authorities.

Accordingly, it is hereby ordered and decreed that the

convictions by the Recorder’s Court of the City of Rock

Hill in all of the seventy-one cases under appeal are hereby

affirmed, and each of the cases is remanded for execution

of sentence as originally imposed.

This Court takes note, from published reports, of the

untimely death of the defendant, Rev. C. A. Ivory, since

hearing of the appeals herein and before rendering judg

ment thereon.

All of which is duly ordered.

George T. Gregory, J r.,

Residing Judge,

Sixth Judicial Circuit.

Chester, S. C.

December 29,1961.

4a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

T he State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

T he City of R ock H ill,

—v.-

Respondent,

L eroy H enry, et al.,

Appellants.

Appeal from York County. George T. Gregory, J r.,

Residing Judge, Sixth Judicial Circuit. Affirmed.

T aylor, C.J.: Appellants here are sixty-five Negroes who

were arrested March 15, 1960, and convicted by the City

of Rock Hill, South Carolina, of the common law offense

of breach of peace.

The record reveals that on the day in question all of

those arrested were engaged in singing patriotic and re

ligious songs in a loud and boisterous manner in the city

of Rock Hill; that the crowd assumed such proportions that

it spread from the sidewalk into the street; that tension

was present in the community resulting from previous dem

onstrations and threats of bombings had been made; that

the singing was done in such loud and boisterous manner

that work in the City Hall was completely disrupted. This

demonstration had been going on from 25 to 30 minutes

before they were forewarned by police officers to desist

from further demonstrations. They failed and refused to

comply with the request of the police and were arrested

and charged with breach of peace.

“In general terms, a breach of the peace is a viola

tion of public order, a disturbance of the public tran

quility, by any act or conduct inciting to violence # # * ,

it includes any violation of any law enacted to preserve

peace and good order. It may consist of an act of

violence. It is not necessary that the peace be actually

broken to lay the foundation for a prosecution for this

offense. If what is done is unjustifiable and unlawful,

tending with sufficient directness to break the peace,

no more is required. Nor is actual personal violence

an essential element in the offense * * # .

“By ‘peace’, as used in the law in this connection, is

meant the tranquility enjoyed by citizens of a munici

pality or community where good order reigns among

its members, which is the natural right of all persons

in political society.” 8 Am. Jur. 834, Section 3; State

v. Edwards, 239 S. C. 339, 123 S. E. (2d) 247. See also

State v. Brown,----- S. C .------ , 126 S. E. (2d) 1; City

of Sumter v. McAllister, ----- S. C. -——, 128 S. E.

(2d) 419, filed November 28, 1962; City of Sumter v.

Lewis, ----- S. C. ----- , 128 S. E. (2d) 684, filed De

cember 1,1962.

Appellants in their brief contend principally that they

were discriminated against because they were Negroes;

second, that there was no breach of peace in that what

they were doing was not within itself unlawful.

Appellants were not convicted under a statute designed

to perpetuate segregation but were convicted of the com

mon law offense of breach of peace, and this applies to

any person irrespective of race. The singing of patriotic

songs and religious hymns is, of course, not unlawful if

done in a lawful manner, but even such praiseworthy acts

may be done at a time and place and in such manner as

6a

to be unjustifiable and unlawful resulting in a breach of

the peace. There is ample evidence here to support the

conclusion that the police acted in good faith to maintain

the public peace, to assure the availability of the streets

for their primary purpose of usage by the public, and to

maintain order in the community.

For the foregoing reasons, we are of opinion that all

exceptions should be dismissed; and It Is So Ordered.

J udgment Affirmed.

Moss, L ewis and B railsford, JJ., concur. Bussey, A.J.,

did not participate.

7a

Order of Denial of Rehearing

I n the

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

City oe R ock H ill,

-v.—

Respondent,

Leroy H enry, et al.,

Appellants.

(Endorsed on Back of Petition for Rehearing)

None of the matters referred to in this petition were

either overlooked or misapprehended.

The petition is therefore denied.

C. A. T aylor, C.J.

J oseph R. Moss, A.J.

J. W oodrow L ewis, A.J.

J. M. Brailsford, A.J.

<̂S1Ŝ “ '38