St. Mary's Honor Center v Hicks Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1992

47 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. St. Mary's Honor Center v Hicks Brief for Respondent, 1992. fe66e27f-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d701b0b6-bd45-4dbd-b46a-8c7ac777f920/st-marys-honor-center-v-hicks-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

Suprem e Court of ti)e ^Bmtcb S ta tes

October T erm , 1992

Melvin H icks,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

MELVIN HICKS

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C, (202) 347-8203

*Charles R. Oldham

Louis Gilden

E laine R. Jones

Charles Stephen Ralston

E ric Schnapper

Marina Hsieh

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

317 N. 11th Street

Suite 1220

St. Louis, MO 63101

(314) 231-0464

Counsel fo r Respondent

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ..................................... 1

SUMMARY OF A R G U M EN T..................................... 8

ARGUMENT ................................................................... 9

I. A TITLE VII PLAINTIFF IS ENTITLED

TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW

IF HE PROVES THAT EVERY NON-

D I S C R I M I N A T O R Y R E A S O N

PROFFERED BY THE DEFENDANT

WAS NOT CREDIBLE...................................... 13

A. By Process of Elimination, McDonnell

Douglas Narrows the Factual Issues to

Determine Whether There was

Discrimination.......................................... 13

B. Allowing a Plaintiff Who Proves Only

a Prima Facie Case Against a Silent

Defendant to be in Better Position

than a Plaintiff Who Proves a Prima

Facie Case And Rebuts all Proffered

Reasons of a Dishonest Defendant is

Illogical...................................................... 19

C. It is Well-Established that Rebuttal of

the Articulated Reasons Serves to

Discharge the Plaintiffs Ultimate

Burden of Proof of Discrimination. . . . 21

D. The Court of Appeals Correctly

Followed McDonnell Douglas in

Holding that Respondent’s Rebuttal of

the Petitioner’s Reasons Entitled Him

to Judgment.............................................. 24

u

II. C R E D I T I N G U N A R T I C U L A T E D

REASONS DEPRIVES A PLAINTIFF OF

HIS FULL AND FAIR OPPORTUNITY TO

PROVE HIS CASE.............................................. 25

A. McDonnell Douglas Requires the

Employer to Frame Clearly the

Factual Issues so the Plaintiff Has a

Full and Fair Opportunity for

Rebuttal..................................................... 25

B. Allowing the Defendant to Benefit

from Unarticulated Reasons by

Escaping Scrutiny for Pretext is

Detrimental to Truth-Seeking and

Efficiency.................... 28

C. The Confusion of the Present Record

Demons t ra t es Why Credi t ing

Unarticulated Reasons Undermines

the Truth-Seeking Function of the

Adversarial Process.................................. 32

III. ADOPTION OF THE "PRETEXT PLUS"

RULE WOULD REQUIRE DIRECT

P R O O F OF D I S C R I M I N A T O R Y

MOTIVE............................................................... 36

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED AS A

MATTER OF LAW IN HOLDING THAT

THE EVIDENCE DEMONSTRATED AN

ABSENCE OF DISCRIMINATION................. 38

CONCLUSION 39

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Bazemore v. Friday,

478 U.S. 385 (1986) .......................................... 19

Benzies v. Illinois Dept, of Mental Health and

Developmental Disabilities, 810 F.2d

146 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 483 U.S.

1006 (1987) ................................................... 29, 30

Castaneda v. Partida,

430 U.S. 482 (1977) 38

Equal Employment Opportunity Comm’n v. West Bros.

Dept. Store, 805 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1986) . . . 28

Fumco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

438 U.S. 567 (1978) passim

Galbraith v. Northern Telecom,

944 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1991) ............................ 24

Jackson v. RKO Bottlers of Toledo, Inc.,

743 F.2d 370 (6th Cir. 1984) ............................ 28

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath,

341 U.S. 123 (1951) 29

La Montagne v. American Convenience Products, Inc.,

750 F.2d 1405 (7th Cir. 1984)............................. 10

Lankford v. Idaho,

500 U .S.__ , 114 L. Ed. 2d 173 (1991)............ 26

Lanphear v. Prokop,

703 F.2d 1311 (D.C. Cir. 1983) 27, 28

McDonnell Douglas,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) ................................... passim

Mesnick v. General Electric,

950 F.2d 816 (1st Cir. 1991).............................. 24

Michigan v. Lucas,

500 U .S .___, 114 L. Ed. 2d 205 (1991)............ 31

Miles v. M.N.C. Corp.,

750 F.2d 867 (5th Cir. 1985) ............................ 35

Nation-wide Check v. Forest Hills Distribs.,

692 F.2d 214 (1st Cir. 1982).............................. 30

Oxman v. WLS-TV,

846 F.2d 448 (7th Cir. 1988) ............................ 10

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) ..................................... 22, 26

Patton v. Mississippi,

332 U.S. 463 (1947) .......................................... 19

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins,

490 U.S. 490 (1989) .......................................... 22

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) ..................................... passim

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) ................................... passim

iv

Pages:

Trans World Airlines v. Thurston,

469 U.S. I l l (1985) ___ 25

United Postal Service Bd. of Governors v. Aikens,

460 U.S. 711 (1983) ................................... passim

University of Pennsylvania v. EEOC,

493 U.S. 182 (1990) 30

Uviedo v. Steves Sash & Door Co.,

738 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1984) ..................... 27, 28

Statutes: Pages:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c)....................................................... 30

Fed. R. Evid. 3 0 1 ............................................................ 20

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. 102-166,

105 Stat. 1073 ................................................ 24, 31

42 U.S.C. § 1621 ............................................................ 30

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ....................................................... 2, 7, 8

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII,

42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq................................... passim

Miscellaneous: Pages:

Catherine J. Lanctot, The Defendant Lies and the Plaintiff

Loses: The Fallacy of the ‘Pretext-Plus’ Rule in

Employment Discrimination Cases,

43 Hastings L.J. 57 (1991) ................................ 36

V

Pages:

vi

Pages:

Marina C. Szteinbok, Indirect Proof of Discriminatory

Motive in Title VII Disparate Treatment

Claims after Aikens,

88 Colum. L. Rev. 1114 (1988).......................... 29

Recent Developments in Disparate Treatment Theory,

EEOC Advance Policy Guidance N 915.002, Lab.

L. Rep. (CCH) 449 Issue No. 493 ..................... 23

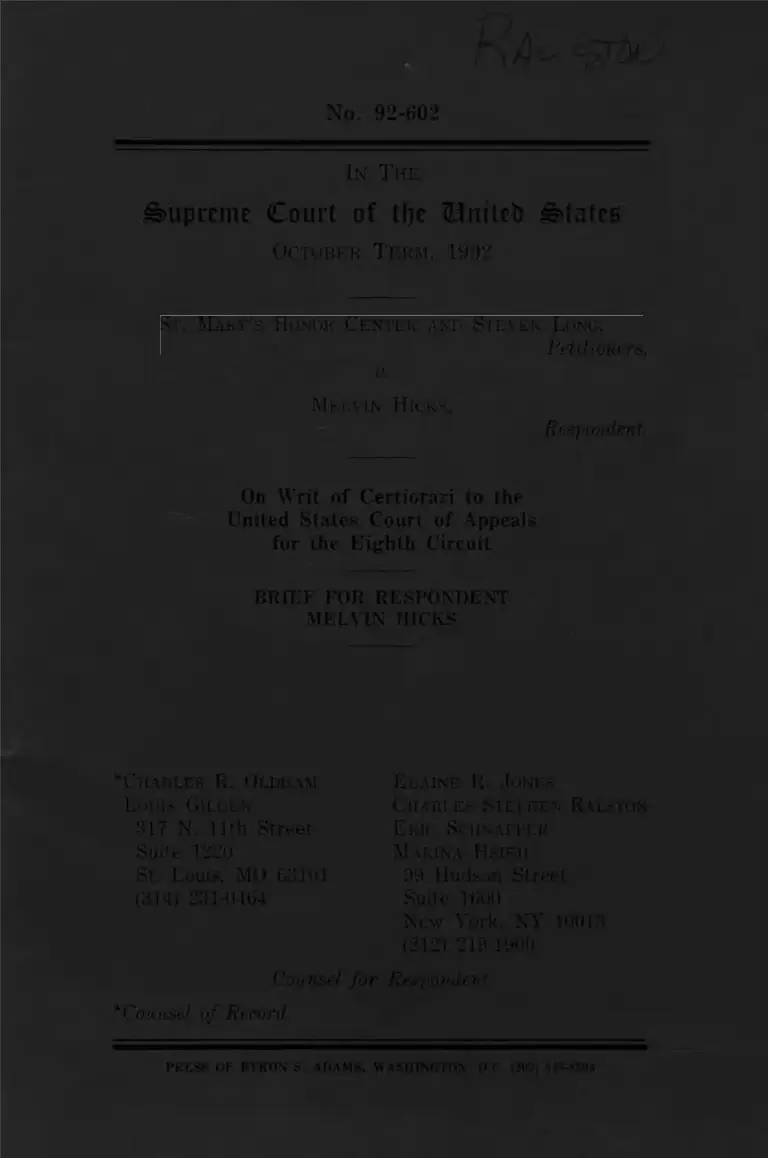

No. 92-602

In The

Suprem e Court of tfje Untteb S ta te s

October Term, 1992

St . Mary’s Honor Center and Steven Long,

Petitioners,

v.

Melvin Hicks,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

MELVIN HICKS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondent Melvin Hicks, an African-American,

began working as a correctional officer at St. Mary’s Honor

Center, a facility of the Missouri Division of Corrections, in

1978. In 1980, he was promoted to shift commander. In

1984, Hicks was demoted and then discharged from this

position. He filed suit against Petitioners St. Mary’s Honor

Center and Steven Long, Superintendent of St. Mary’s,

alleging that Petitioners had demoted and discharged him on

the basis of his race and in retaliation for his filing a

complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity

2

Commission, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq. The complaint also alleged

that Petitioner Long had violated Hicks’ rights under 42

U.S.C. §1983. Order and Memorandum of the District

Court, Appendix to Petition for Writ of Certiorari ("Pet."),

at pages A-14 to A-15, A-18.

In 1981, the Deputy Director of the Missouri Division

of Corrections, in Jefferson City, Missouri, requested a

statewide study of the correctional facilities that, inter alia,

addressed the "organizational stability" of St. Mary’s. Joint

Appendix ("J.A.") at 68-70; 81-85. The study measured

"shares of power" held by black and white supervisors [levels

2-6] and correctional officers (CO-ls) at St. Mary’s, noting

that at level 2, the custody sergeants, there were no whites:

6. W

5. B

4. W W B W W

3. B B B B B B B

2. B B B

I. B B B B B B B B B W B B B B B W B B B B B

J. A. 82-83. The study concluded that although the

"executive positions are racially balanced (one White and

one Black), because "the majority of the program staff

(63.64%) is black ... the potential for subversion of the

Superintendent’s power — should the staff become racially

polarized — is very real." J.A. 85. The Director and

Deputy Director of the Division of Corrections discussed the

report with management and circulated copies to

Superintendents of the Centers. J.A. 70, 71, 73.

In late 1983, there were numerous complaints to the

Division about the conditions and operations at St. Mary’s.

Pet. A-15. Among the complainants were two white

correctional officers from St. Mary’s who called and visited

Jefferson City because "they wanted to make promotion, but

3

they said blacks were in the way, so they couldn’t be

promoted." Record ("R.") at page 1-21. After

investigations, in January 1984 the Superintendent at St.

Mary’s was transferred and replaced by Petitioner Steven

Long. Pet. A-15. John Powell, a white male, became the

Chief of Custody, over the three Shift Commanders. Pet. A-

15.

Supervisory personnel in the custody section of St.

Mary’s changed dramatically after Petitioner Long’s

appointment. During the four months between Long’s

arrival and Hicks’ departure, the custody supervisors

underwent the following transformation:

6. Superintendent

5. Asst. Superintendent

3. Chief of Custody

2. Shift Supervisor

Jan. 1984 April 1984

W - Schulte W — Long

B - Banks B - Banks

B - Greenlee W — Powell

B - Woodward W — Hefele

B - MacAvoy W — Wilson

B - Hicks W

Pet. A-15, A-27; J.A. 56-57, 82.

The trial court found that when Long arrived in

January 1984 there were 30 blacks employed, and when he

left the facility in May, 1985 there were 29 blacks employed.

R. 2-111. In the first year after Long and Powell took

charge, twelve blacks were fired and one demoted, but only

one white was terminated. R. 3-10 to 3-11.

The testimony revealed that while Long could

effectively terminate employees, he did not control the hiring

for level 1 CO-ls, the bulk of the positions. That was done

pursuant to merit system lists by the central personnel office

in Jefferson City:

QUESTION: You’re the one that recommends the

CO-ls?

4

THE WITNESS: Not CO-ls. They come directly

from Jefferson City. They have a

central pool.

J.A. 67 (testimony of Vincent Banks).

The district court found that Hicks established a

prima facie case, under McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S. 792

(1973), by showing that he is a member of a protected class;

that he met the job qualifications of a shift commander, as

proven by his experience, satisfactory record, and ratings;

that he suffered adverse actions in his demotion and

termination; and that after his demotion, the position

remained open and was then filled by a white male. Pet. A-

22 to A-23.

The court found that the burden then shifted to the

Petitioners to set forth a legitimate, non-discriminatory

reason for the adverse employment decisions. Pet. A-23.

Petitioners set forth two reasons for the adverse action: "the

severity and the accumulation of violations committed by

plaintiff." Pet. A-23. Long testified that the reasons for

termination were:

Mainly, an accumulation of the infractions by

Mr. Hicks, of the problems that had been

accounted (sic) to that point, without any

appearance of any improvement in his

conduct, and the seriousness of that individual

incident.

R. 2-104.

In the six years before the arrival of Long and

Powell, Hicks had not been suspended or disciplined, Pet. A-

16, but was disciplined three times in March 1984: (i) for

being the shift commander on duty when a front door officer

was away from his post, for which he received a five day-

suspension, Pet. A-15, A-16; (ii) for failing to correct the log

of a subordinate’s use of St. Mary’s vehicle, for which he was

5

demoted to CO-1, Pet. A-17; and (iii) for allegedly failing to

investigate a fight between inmates, for which he received a

reprimand letter, Pet. A-18. Around April 11, 1984 Hicks

filed an EEOC complaint complaining of racial

discrimination in employment conditions. Amended

Complaint, H 10.

The district court compared the plaintiffs disciplinary

violations with actions taken against others for similar or

more serous violations. The court noted that the plaintiff

was the only supervisor disciplined for violations committed

by his subordinates, Pet. A-24, that far more serious

infractions by other supervisors and CO-ls (many of whom

where white) were punished far less severely, Pet. A-25.

These included allowing guests with guns into the institution,

allowing inmates to escape and allowing inmates access to

personal files and the Center’s power room, and were

punished less severely, if at all. Pet. A-25 to A-26.

On April 19,1984 Steven Long and John Powell met,

in Assistant Superintendent Vincent Banks’ office, with

Hicks to inform him of his demotion to CO-1 status and

reduction in his salary. Pet. A-18. Powell and Long

assigned Hicks be a front door officer and informed him he

would have to perform custodial duties. J.A. 43. Powell

testified that custodial duties had never been assigned to a

front door officer before. J.A. 43. After the meeting,

Powell followed Hicks and heated words were exchanged.

Hicks left without further incident. Pet. A-18.

At trial, Powell denied any personal difficulty with

Melvin Hicks: "I can’t say that there was difficulties between

he and I. At no time was there any kind of personal —"

J.A. 46. Although Powell also denied any instigating role in

the confrontation with Hicks, J.A. 46, the district court

stated that the evidence suggested that Powell had

"manufactured the confrontation between plaintiff and

himself in order to terminate plaintiff." Pet. A-26. Powell

6

wanted to take disciplinary action against Hicks for the

incident. Pet. A-18. Hicks filed a second EEOC complaint

on May 7, 1984, alleging demotion of the basis of race and

amended it to add the discharge claim. Am. Comp. If 15.

On May 9, 1984 a four person disciplinary review

board, composed of two blacks, recommended a three day

suspension of Hicks for the confrontation.- Pet. A-18 to A-

19. Petitioner Long testified that he looked at Sgt. Hicks’

entire record and no questions were raised in his mind about

the propriety of Mr. Hick’s dismissal under those

circumstances, [R. 2-155], although the disciplinary board,

had recommended a far lesser sanction, R. 2-156. He

"disregarded their vote and recommended termination." Pet.

A-18 to A-19. Donald Wyrick, Director of the Division of

Adult Institutions, approved the final discharge decision. R.

2-109.

The trial court concluded, based on its extensive

comparison of the application and degree disciplinary

practices at St. Mary’s, that the reasons proffered by

Petitioners were pretextual. Pet. A-23. However, after

finding pretext by Petitioners, the court held that plaintiff

nonetheless had to prove that race was the reason for the

action against him. Pet. A-26. The court stated:

It is clear that John Powell had placed

plaintiff on the express track to termination,

but that it is also clear that Powell received

the aid of Ed Ratliff [white] and Steve Long

in this endeavor. The question remains,

however, whether plaintiffs race played a role

in their campaign.

Pet. A-26. The court further noted that "although plaintiff

has proven the existence of a crusade to terminate him, he

has not proven that the crusade was racially rather than

personally motivated." Pet. A-27.

7

In reaching its final conclusion that Hicks had failed

to prove by "direct evidence or inference that his unfair

treatment was motivated by his race," Pet. A-29, the district

court discounted the disproportionate firing of blacks at St.

Mary’s because it thought that Defendant Long had hired

blacks also; the court noted that CO-1 blacks were not

disciplined for violations occurring on plaintiffs shift, that

blacks sat on the disciplinary review boards, that a large

number of black supervisors were fired because nearly all

the supervisors were black at the beginning of 1984, and that

both Long and Powell testified that they did not know of the

study regarding racial balance. Pet. A-27 to A-28.

The court entered judgment for St. Mary’s Honor

Center on Respondent’s claim of race discrimination in

violation of Title VII, Pet. A-29, and also entered judgment

for Steve Long on the claim of racial discrimination under

42 U.S.C. §1983 for the same reasons, Pet. A-30. No

mention was made in the findings about the judgment of

plaintiffs claim of retaliation under Title VII.

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit reversed, finding that once plaintiff proved a prima

facie case and that the employer’s articulated reasons were

pretextual, plaintiff was entitled to judgment as a matter of

law. Pet. A-12. The Court of Appeals did not address the

question whether the district court’s "assumption" of the

unarticulated personal reason of animosity was proper,

because it found that the that reason was never claimed by

defendants. Pet. A-10. The appellate court did not review

the findings of the trial court for clear error and did not rule

on the issue of retaliation because it reversed the district

court on the basis of plaintiffs disparate treatment theory.

Pet. A-12, n.9:

In this circuit, if the plaintiff has met his or

her burden of proof at the pretext stage —

that is, if the plaintiff has proven by a

8

preponderance of the evidence that all of the

defendant’s proffered nondiscriminatory

reasons are not true reasons for the adverse

employment action — then the plaintiff has

satisfied his or her ultimate burden of

persuasion. No additional proof of

discrimination is required.

Pet. A -ll. The court of appeals reversed the judgement of

the district court on the merits of plaintiffs Title VII claim

against St. Mary’s, and the §1983 claim against Long. Pet.

A-12.

The defendants, St. Mary’s Honor Center and Steven

Long, filed a petition for certiorari with the Supreme Court

of the United States, this petition was granted and the case

set for argument.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The McDonnell Douglas/Burdine line of cases requires

that judgment be entered for a Title VII plaintiff if the

reasons articulated by the defendant as the "legitimate,

nondiscriminatory" reasons for the disputed employment

decision are proven to be false. This follows because upon

the establishment of a prima facie case, prohibited

discrimination is established as one of the possible reasons

for the decision. All other possible reasons except the ones

articulated and relied upon by the employer necessarily drop

out of the case. Therefore, if the articulated reasons are

demonstrated to be false and therefore pretextual, the only

reason remaining in the case is prohibited discrimination.

II.

It is inconsistent with the purpose of the McDonnell

9

Douglas/Burdine line of cases to permit a defendant to rely

on a reason not articulated as being the one for making the

employment decision. A central purpose of the McDonnell

Douglas!Burdine order of proof is to eliminate all reasons

not relied on and to permit full exploration of the reasons

articulated by the employer. A plaintiff is unable to do so

if the trial court relies on a reason not advanced by the

employer. Thus, the truth-seeking function of the inquiry is

undermined.

III.

It is clear that a plaintiff may prove pretext either

through direct evidence of discrimination or by

demonstrating that the articulated reasons are in fact not the

real reasons. The adoption of the "pretext-plus" rule

advanced by Petitioners would, in effect, require that

plaintiffs adduce direct evidence of racist motivation in order

to prevail. Such a result is directly contrary to the

unanimous decisions of this Court in the McDonnell

Douglas/Burdine line of decisions.

IV.

The district court erred as a matter of law in holding

that additional evidence proved that racial discrimination

was not a motivating factor in the discharge of Respondent.

These errors required the reversal of the decision of the

district court.

ARGUMENT

Our nation’s commitment to enforcing fully Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and other anti-discrimination laws

has required the courts and Congress to address the

difficulties of proving subtle, as well as blatant, cases of

10

discrimination.1 In McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973), Justice Powell, wrote for a unanimous

Court, setting forth rules that would govern the order of

proof and the allocation of the evidentiary burdens in cases

alleging intentional discrimination. This Court further

explained the McDonnell Douglas inquiry, again in a

unanimous opinion, in Texas Dept, o f Community Affairs v.

Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981).

Under the McDonnell Douglas inquiry, the plaintiff

carries the initial burden of proving, by a preponderance of

the evidence, a prima facie case of the forbidden

discrimination. The prima facie requirements vary

depending on the factual situation and the adverse action at

issue, for example, in a failure to hire case a plaintiff would

‘Some cases of intentional discrimination can be proved by direct

evidence of discrimination, e.g., Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324 (1977), but, in most cases only indirect evidence will be available.

Because Title VII prohibits all forbidden discrimination, not only in

cases where there is a "smoking gun,” standards that guide the courts’

evaluation of indirect proof of discrimination are crucial. For

example,

Age discrimination may be subtle and even

unconscious. Even an employer who knowingly

discriminates on the basis of age may leave no

written records revealing the forbidden motive and

may communicate it orally to no one. When

evidence is in existence, it is likely to be under the

control of the employer, and the plaintiff may not

succeed in turning it up. The indirect method [of

proof] compensates for these evidentiary difficulties

by permitting the plaintiff to prove his case by

eliminating all lawful motivations, instead of proving

directly an unlawful motivation.

Oxman v. WLS-TV, 846 F.2d 448 (7th Cir. 1988), quoting La

Montagne v. American Convenience Products, Inc., 750 F.2d 1405,1410

(7th Cir. 1984).

11

show

(i) that he belongs to a racial minority; (ii)

that he applied and was qualified for a job for

which the employer was seeking applicants,

(iii) that, despite his qualifications, he was

rejected; and (iv) that, after his rejection, the

position remained open and the employer

continued to seek applicants from persons of

complainant’s qualifications.

McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S., at 802.2 Proof of a prima

facie case establishes a legally mandatory, rebuttable

presumption, which, if the defendant remains silent, requires

judgment for the plaintiff. Burdine, 450 U.S., at 254 n.7.

Next, if the plaintiff succeeds in proving the prima

facie case, the burden must shift to the defendant "to

articulate some legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason for the

employee’s rejection." McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S., at 802.

This is a burden of production, under which "the defendant

must clearly set forth, through the introduction of admissible

evidence, the reasons for the plaintiffs rejection." Burdine,

450 U.S., at 254-55. Although the reasons need not be

proved by a preponderance of evidence at this stage, they

must be legally sufficient to justify a judgment for the

defendant. Id. 450 U.S., at 255. Meeting this burden

serves simultaneously to meet the plaintiffs

prima facie case by presenting a legitimate

2The facts required to make out a prima facie case will necessarily

vary in Title VII cases. Burdine, 450 U.S., at 253 n.6. Thus, in this

discharge case, the district court found that Respondent had proven

that (i) he was a member of a protected class, (ii) met the

qualifications for his job, (iii) was nonetheless demoted and

discharged, and (iv) the position remained open after his demotion

and was then filled by a white male. Pet. App. A-22 to -23.

12

reason for the action and to frame the factual

issue with sufficient clarity so that the plaintiff

will have a full and fair opportunity to

demonstrate pretext.

Id., at 255-56 (emphasis added). The defendant’s evidence

must serve these two functions in order to be sufficient to

discharge its burden and to rebut the presumption of

discrimination. Id., at 256.

Finally, if the defendant meets its burden of

production, the burden shifts back to the plaintiff. In

Burdine, this Court explained the plaintiffs ultimate burden.

of persuasion in a single paragraph that concluded its

discussion of the three-part test:

The plaintiff retains the burden of

persuasion. She now must have the

opportunity to demonstrate that the proffered

reason was not the true reason for the

employment decision. This burden now

merges with the ultimate burden of persuading

the court that she has been the victim of

intentional discrimination. She may succeed

in this either directly by persuading the court

that a discriminatory reason more likely

motivated the employer or indirectly by

showing that the employer’s proffered

explanation is unworthy of credence. See

McDonnell Douglas, 411 U.S., at 804-05.

Burdine, 450 U.S. at 256 (emphasis added). The

interpretation of this paragraph lies at the heart of the

controversy of this case.

13

I. A TITLE VII PLAINTIFF IS ENTITLED TO

JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW IF HE

PROVES THAT EVERY NON-DISCRIMINATORY

REASON PROFFERED BY THE DEFENDANT

WAS NOT CREDIBLE.

After a plaintiff has proven a prima facie case and a

defendant proffers its reason for the allegedly discriminatory

action, a plaintiff under McDonnell Douglas "may succeed ...

by showing that the employer’s proffered explanation is

unworthy of credence." Burdine, 450 U.S., at 256. The court

of appeals held, correctly in Respondent’s view, that a

plaintiff is entitled to judgment if he or she convinces the

court — as concededly occurred here - that all of the

employer’s proffered explanations were unworthy of

credence. Pet. App. A-26. Petitioners contend, on the other

hand, that a plaintiff must do far more. A Title VII plaintiff

is not entitled to judgment, Petitioners urge, unless the

plaintiff "eliminate[s] all lawful reasons for the employment

decision." Brief for the Petitioners ("Pet. Br.") at 16

(emphasis added).

A. By Process of Elimination, McDonnell Douglas

Narrows the Factual Issues to Determine

Whether There was Discrimination.

Petitioners’ argument that a plaintiff must eliminate

all conceivable legitimate explanations is inconsistent with

the fundamental methodology of McDonnell Douglas and its

progeny. McDonnell Douglas does not contemplate that the

evidence or findings of fact and conclusions of law in a Title

VII case must canvas all, or even most, conceivable

explanations for a disputed employment practice. Rather,

the serial ordering and allocation of burdens in McDonnell

Douglas "is intended progressively to sharpen the inquiry

into the elusive factual question of intentional

discrimination." Burdine, 450 U.S., at 354 n.8.

14

The three-part McDonnell Douglas inquiry is

structured as a process of elimination. As then-Justice

Rehnquist explained in Fumco Construction Corp. v. Waters,

438 US. 567 (1978), the primary principle guiding the inquiry

is to evaluate evidence "in light of common experience as it

bears on the critical question of discrimination." Fumco, 438

U.S., at 577. The Fumco Court explained the fundamental

methodology of the McDonnell model of indirect proof:

more often than not people do not act in a

totally arbitrary manner, without any

underlying reasons, especially in a business

setting. Thus, when all legitimate reasons for

rejecting an applicant have been eliminated as

possible reasons for the employer’s actions, it

is more likely than not the employer, who we

generally assume acts only with some reason,

based his decision on an impermissible

consideration such as race.

Fumco, 438 U.S., at 577. Against this understanding, each

step of the inquiry is designed to present the litigants and

fact finder with questions that progressively narrow all

possible reasons for the employer’s action until the "real"

reason is revealed. These presumptions, burdens, and

inferences "reflect judicial evaluations of probabilities and ...

conform with a party’s superior access to the proof."

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 359 n.45 (1977)

(citations omitted). If, at the end of the three-step inquiry,

no nondiscriminatory reason remains, the necessary

inference is that invidious discrimination was in reality the

motive for the disputed action.

The first step of McDonnell Douglas requires the

plaintiff, in order to proceed further, to prove a prima facie

case. This "serves a important function in the litigation: it

eliminates the most common nondiscriminatory reasons for

the plaintiffs rejection." Burdine, 450 U.S., at 253-54.

15

Those reasons are (i) that there was no job vacancy, and (ii)

that the plaintiff was absolutely or relatively unqualified.

Teamsters, 431 U.S., at 358 n.44. Those facts, coupled with

the additional prima facie evidence that the plaintiff was a

member of a protected class and was bypassed or replaced

by a person not from that class, creates a presumption of

discrimination. Discrimination is presumed because "we

presume these acts, if otherwise unexplained, are more likely

than not based on the consideration of impermissible

factors." Fumco, 438 U.S., at 577.

Once a plaintiff has established a prima facie case,

the focus of the judicial inquiry, and the proof required of

each party, narrows. The inquiry now focuses on the

particular explanations that the employer itself chose to

proffer through admissible evidence. Placing the burden on

the employer reflects the ability and motivation of the

employer to identify any legitimate, nondiscriminatory

explanations for which there may be substantial evidentiary

support:

[Tjhe employer [i]s in the best position to show why

any individual employee was denied an employment

opportunity.... [In some instances] the company’s

records [are] the most relevant items of proof. If the

[disputed action] was based on other factors, the

employer and its agents kn[o]w best what those

factors were and the extent to which they influenced

the decisionmaking process.

Teamsters, 431 U.S., at 359 n.45. The litigation decision of

the employer to place in controversy only those particular

explanations eliminates from further consideration the

alternative explanations that the employer chose not to

advance. These discarded reasons must now be presumed

not to be possible reasons in fact for the challenged action.

16

McDonnell Douglas is deliberately framed to assure

that the list of possible explanations to be addressed at trial

is winnowed down; the defendant cannot put a possible

explanation into issue merely by mentioning it in a pleading

or a brief, but must specifically frame the proffered reason

and support it with admissible evidence. Burdine, 450 U.S.,

at 255. These requirements would be meaningless if

plaintiffs and courts were obligated to consider "all" possible

reasons or any of a myriad of explanations that a defendant

itself chooses not to proffer. The potentially infinite inquiry

suggested by Petitioners would be impossible for any

plaintiff to complete, and unwieldy for any court to assess.

The discovery necessary merely to attempt to disprove "all"

possible reasons would be boundless.

"The factual inquiry proceeds to a new level of

specificity" once the employer discharges its burden of

articulating a particular reason or reasons for its actions.

Burdine, 450 U.S., at 255. The litigation then focuses

exclusively on the specific reasons proffered by the employer.

At this point, the issue before the court is narrow,

albeit at times difficult: "In short, the district court must

decide which party’s explanation of the employer’s

motivation it believes." United Postal Service Bd. o f

Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 716 (1983) (emphasis

added).

At the final step of the McDonnell Douglas inquiry

the plaintiff must address the employer’s articulated reasons

for the challenged action. Burdine quite clearly explains how

this task "merges with" the plaintiffs ultimate burden of

persuasion to allow two courses of action, which it states in

the disjunctive. Burdine, 450 U.S., at 255. The plaintiff may

either prove that • discrimination was more likely than the

articulated reasons to have been the employer’s real

motivation, or prove simply that those stated reasons were

not in fact the employer’s motivations. The latter option,

17

proof that the stated reasons are not credible, proves by

inference that discrimination was the reason, since all

possible nondiscriminatory reasons have been eliminated

from the case either because they were not articulated by

defendant or because they were proved to be false. No

reasons remain but the discrimination that we infer from our

common experience. See Fumco, 438 U.S., at 577. That

factual finding discharges the ultimate burden of persuasion

and compels a judgment for the plaintiff.3 Additional proof

of discrimination, direct or indirect, would be redundant.

In this case, Petitioners concede, the district court

proceeded to reject as not truthful the explanations they

proffered at trial. Pet. Br. 11, 17, 26; Pet. App. A-26.

Having eliminated the only lawful reasons properly before

the court under McDonnell Douglas, Respondent was under

no obligation to go further and address "all," or any, other

conceivable explanations that Petitioners had chosen not to

assert. Having eliminated the only non-discriminatory

explanation in issue, respondent was entitled to a judgment

that the only remaining motive at issue -- racial

discrimination -- had been established.

The following diagram illustrates the narrowing of

issues in a case, like this one, in which a plaintiff proves a

prima facie case which is met by articulated reasons by the

employer, which are then proved to be unworthy of

credence.

Petitioner’s semantic argument that proof of "pretext" must

instead mean proof of "pretext for discrimination" confuses separate

analytical steps: The plaintiffs evidentiary burden is to prove only

that the articulated reasons were not the employer’s true reasons; the

consequence of so doing creates the inference that discrimination was

the reason.

18

MODEL OF PROOF FOR CASE WHERE

ARTICULATED REASONS ARE PROVEN FALSE

UNIVERSE OF POSSIBLE REASONS

Discrimination Articulated, P o s s i b l e

Legitimate, Reasons

Nondiscrimin- 1 no vacancy

atory Reasons 2 not quali-

fied

No. 3....

No. n.

In Because

of Prima

Facie Case

In Upon

Articulation

Nos. 1 & 2 Out

Because of

Prima Facie Case;

Remainder Out

Because Not

Articulated

Discrimination Articulated,

Legitimate,

Nondiscrimin-

atory Reasons

Remains in

Evidence

Out because Shown to

Be Pretextuai

Discrimination

Sole Remaining Reason

Plaintiff Must Win

19

B. Allowing a Plaintiff Who Proves Only a

Prima Facie Case Against a Silent Defendant

to be in Better Position than a Plaintiff Who

Proves a Prima Facie Case And Rebuts all

Proffered Reasons of a Dishonest Defendant

is Illogical.

Petitioners’ assertion that an employee is not entitled

to judgment unless he or she eliminates all possible

legitimate explanations is inconsistent with McDonnell

Douglas' holding that an unrebutted prima facie case

requires the entry of judgment for the plaintiff.

Establishment of the prima facie case in

effect creates a presumption that the

employer unlawfully discriminated against the

employee. If the trier of fact believes the

plaintiffs evidence, and if the employer is

silent in the face of that presumption, the

court must enter judgment for the plaintiff

because no issue of fact remains in the case.

Burdine, 450 U.S. at 254.

In the circumstances described by Burdine, the

plaintiff clearly has not - as petitioners argue a plaintiff

must -- eliminated all possible legitimate reasons for the

disputed action. On the contraiy, the prima facie case only

"eliminates the two most common nondiscriminatory reasons

for the action." Burdine, 450 U.S. at 254. The theoretical

possibility that some nondiscriminatoiy reason underlies the

conduct at issue is not sufficient to create an issue of fact, or

prevent entry of judgment for plaintiff, since mere

speculation as to the existence of some legitimate

explanation is not sufficient to overcome the weight of the

evidence creating the prima facie case. See Bazemore v.

Friday, 478 U.S. 385, 403 n.14 (1986); Patton v. Mississippi,

332 U.S. 463, 466-468 (1947). A "possible" legitimate

20

explanation is sufficient to create an issue of fact only if and

when it is set forth by the defendant through the

introduction of admissible evidence.

When an employer does articulate, through evidence,

a particular non-discriminatory reason, it creates an issue of

fact with regard to that proffered reason. But the

articulation and substantiation of one such reason does not

create an issue of fact with regard to all, or any, of the other

conceivable reasons. If the petitioners in this case had

offered no defense whatever, the district court could not

have ruled for petitioners on the theory, for example, that

respondent had failed to prove he was not dismissed for

chronic absenteeism.

In the instant case, petitioners, as contemplated by

McDonnell Douglas, articulated through admissible evidence

two specific alleged legitimate motives -- the severity and

accumulation of disciplinary infractions. As to each but only

as to these there was undeniably an issue of fact. These

proffered reasons were the primary focus of the trial, and

the district judge decided in favor of respondent with regard

to both of those factual issues, holding that neither of the

articulated reasons was the actual basis for respondent’s

dismissal. But, once the district court had rejected the two

proffered reasons the case returned to a similar evidentiary

posture to where it was before the petitioners offered any

explanation of their conduct.4 Indeed, the position of

4 Of course the original presumption legally mandated by the

creation of the prima facie case under McDonnell Douglas was

discharged when the petitioners met the burden of production. See

Fed. R. Evid. 301. However, the evidence which gave rise to the

original prima facie case remained in the record unrebutted. The

inference that evidence generated continued to be that employers are

likely to act for some reason, and absent any legitimate reason, it is

more likely than not that the basis of the decision was impermissible

discrimination. Fumco, 438 U.S. at 577.

21

respondent following the trial was even better than would

have been the case had the petitioners merely remained

silent, because the district judge had affirmatively rejected

two possible explanations. As Petitioners candidly concede,

the unsuccessful proffer of "a phony reason" provides

support for an inference "that the employer is trying to

conceal a discriminatory reason for his action." Pet.Br. 15

n.3.

A defendant which unsuccessfully offers a "phony

reason" logically cannot be in a better legal position that a

defendant who remains silent, and offers no reasons at all

for its conduct. In both situations there is no articulated

non-discriminatory reason to explain away the evidence and

inference offered by plaintiffs. The theoretical possibility,

present in both situations, that there is some unarticulated

legitimate reason is not by itself sufficient to create an issue

of fact.

C. It is Well-Established that Rebuttal of the

Articulated Reasons Serves to Discharge the

Plaintiff’s Ultimate Burden of Proof of

Discrimination.

Petitioners’ argument that a plaintiff must eliminate

all legitimate reasons for a disputed employment action

squarely contradicts the entire line of McDonnell Douglas

cases, which require a plaintiff only to discredit the

employer’s proffered explanation. In Aikens, a more recent

application of McDonnell Douglas, all members of the Court

agreed that it was error to require that the plaintiff submit

direct evidence of discriminatory intent. Aikens, 460 U.S., at

714 n.3, 717. The Aikens Court reaffirmed that plaintiff

discharges of his ultimate burden of persuasion by either of

two choices: proving directly that a discriminatory reason

more likely motivated the employer "‘or indirectly by

showing that the employer’s proffered explanation is

22

unworthy of credence.’" Id., at 716, quoting Burdine, 450

U.S., at 256. See also Aikens, 460 U.S., at 717, 718

(Blackmun, J., concurring) ("the McDonnell Douglas

framework requires that a plaintiff prevail when at the third

stage of a Title VII trial he demonstrates that the legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reason given by the employer is in fact

not the true reason for the employment decision.")

Recently, in Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491

U.S. 164, 187 (1989), the Court again affirmed the plaintiffs

right to demonstrate that the employer’s proffered reasons

for its decision "were not its true reasons." The Patterson

Court found too narrow the district court’s instruction that

plaintiff could carry her burden of persuasion only by

showing that she was better qualified than the while

applicant who got the job; the majority held that the plaintiff

"may not be forced to pursue any particular means of

demonstrating that respondent’s stated reasons are

pretextual." Id., 491 U.S., at 188. See also Price Waterhouse

v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 490, 247 n.12 (1989) (plurality opinion

by Brennan, J.) (noting that a plaintiff may prevail under

Burdine if she proves "that the employer’s stated reason for

its decision is pretextual); Id., 490 U.S., at 261 (1989)

(O’Connor, J., concurring) (distinguishing mixed-motive

cases as "a supplement to the careful framework established

by our unanimous decisions" in McDonnell Douglas and

Burdine)- Id., 490 U.S., at 287 (Kennedy, J., dissenting)

(emphasis in original) (restating the Burdine test that "a

plaintiff may succeed in meeting her ultimate burden of

persuasion ‘either directly by persuading the court that a

discriminatory reason more likely motivated the employer or

indirectly by showing that the employer’s proffered

explanation is unworthy of credence.’"). And -

notwithstanding the recent decisions of the few circuits

relied on by Petitioner - the overwhelming majority of the

courts of appeals agree with the court below that McDonnell

Douglas dictates entry of judgment for the plaintiff upon

proof that all of the employer’s articulated reasons are a

23

unworthy of credence.5 &

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

the agency responsible for enforcement of Title VII, last

year also explicitly reaffirmed the McDonnell Douglas model

of indirect proof. See Recent Developments in Disparate

Treatment Theory, EEOC Advance Policy Guidance

N 915.002 (approved by 4-0 vote July 7, 1992), Lab. L. Rep.

(CCH) 449 Issue No. 493, Part 2 (July 20, 1992). The

5See, e.g., King v. Palmer, 778 F.2d 878, 881 (D.C. Cir. 1985)

("Burdine makes it absolutely clear that a plaintiff who establishes a

prima facie case of intentional discrimination and who discredits the

defendant’s rebuttal should prevail."); Lopez v. Metropolitan Life Ins.

Co., 930 F.2d 157, 161 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, ___ U.S. ___, 116

L.Ed.2d 185 (1991) (explaining that to show "pretext, a plaintiff need

not directly prove discriminatory intent. It is enough for the plaintiff

to show that the articulated reasons were not the true reasons for the

defendant’s actions”); Ibrahim v. New York State Dep’t o f Health, 904

F.2d 161, 168 (2d Cir. 1990) (demonstrating that defendant’s

proffered explanation was not the true reason for its decision meets

plaintiffs ultimate burden of persuasion); Carden v. Westinghouse

Electric Corp., 850 F.2d 996, 1000 (3rd Cir. 1988) ("A showing that a

proffered justification is pretextual is itself equivalent to finding that

the employer intentionally discriminated."); Thombrough v. Columbus

& Greenville R. Co., 760 F.2d 633, 639-40 (5th Cir. 1985) (disproving

the proffered reasons "recreates the situation that obtained when the

prima facie case was initially established: in the absence of any known

reasons for the employer’s decision, we presume that the employer

was motivated by discriminatory reasons"; "Thus, in our view, unlike

Humpty Dumpty, the employee’s prima facie case can be put back

together, through proof that the employer’s proffered reasons are

pretextual"); MacDissi v. Balmont Industries, 856 F.2d 1054, 1059 (8th

Cir. 1988) (once fact finder is persuaded that proffered reason is not

true reason, proof of intentional discrimination "unjustifiably

multiplies the plaintiffs burden"); Caban-Wheeler v. Elsea, 904 F.2d

1549, 1554 (11th Cir. 1990) (proving the proffered reason is not

worthy of belief "satisfies the required ultimate burden of

demonstrating by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she has

been the victim of intentional racial discrimination").

24

EEOC found the command of Aikens and Burdine "clear":

"a plaintiff can prevail either by proving that discrimination

more likely motivated the decision or that the employer’s

articulated reason is unworthy of belief." Id., at 4 n.5

(emphasis in original). It concluded:

Thus the Commission disagrees with those

courts that have held that this is not enough

to prevail for a plaintiff to disprove the

employer’s articulated reason. See, e.g.,

Galbraith v. Northern Telecom, 944 F.2d 275,

282-83 (6th Cir. 1991); ... Mesnick v. General

Electric, 950 F.2d 816, 824 (1st Cir. 1991) ....

Ibid.

Congress has not altered the McDonnell Douglas-

Burdine test and its widespread use in the court of appeals.

This silence, in light of its recent and extensive amendments

of the burdens of proof and persuasion in other types of

Title VII claims, suggests its approval of this method of

indirect proof of Title VII claims. See, e.g., The Civil Rights

Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, § 105, 105 Stat. 1074,

1074-75 (overruling Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490

U.S. 642 (1989), with respect to the burden of proof in

disparate impact cases); Id. § 107, 105 Stat., at 1075-76

(overruling Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989),

regarding proof and remedies in mixed motive cases).

D. The Court of Appeals Correctly Followed

McDonnell Douglas in Holding that

Respondent’s Rebuttal of the Petitioner’s

Reasons Entitled Him to Judgment.

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit correctly

applied the McDonnell Douglas analysis to this case. Pet.

App. A-l to -12. The court accepted the district court’s

findings, which are undisputed here, that Respondent had

25

proved a prima facie case of discrimination in his demotion

and termination, that the Petitioners had articulated only

two reasons for their actions, and that Respondent had

proved by a preponderance of the evidence that both of

those reasons were not credible. Pet. App. A-8.

However, rather than concluding its inquiry, the

district court added speculations of its own, suggesting that

although Respondent had proven the existence of a crusade

to terminate him "he has not proven that the crusade was

racially rather than personally motivated." Pet. App. A-27.

The court of appeals found that the district court’s

"assumption" of a motivation was never claimed by

defendants. Pet. App. A-10. Following McDonnell Douglas,

the court below correctly held that the defendant must

introduce evidence to clearly frame its reasons for the

plaintiffs rejection. Ibid. Following Fumco and Burdine,

the court then properly held that since the Respondent met

his burden of rebutting all of the defendants’ proffered

reasons, as a matter of law he "satisfied his ... ultimate

burden of persuasion. No additional proof of discrimination

is required." Pet. App. A -ll.

II. CREDITING UNARTICULATED REASONS

DEPRIVES A PLAINTIFF OF HIS FULL AND FAIR

OPPORTUNITY TO PROVE HIS CASE.

A. McDonnell Douglas Requires the Employer to

Frame Clearly the Factual Issues so the

Plaintiff Has a Full and Fair Opportunity for

Rebuttal.

A plaintiff would not in any meaningful sense be

accorded "his day in court" if he does not know what

explanations by his employer he must disprove at trial.

Trans World Airlines v. Thurston, 469 U.S. I l l , 121 (1985).

Fundamental fairness demands that the plaintiff have

26

sufficient notice to develop and present evidence, and

effectively examine witnesses at trial.6

The McDonnell Douglas inquiry safeguards both

parties opportunity to respond to relevant issues by requiring

each party to frame the facts. In order to discharge

satisfactorily its burden of production under McDonnell

Douglas, the employer must "frame the factual issue with

sufficient clarity so that the plaintiff will have a full and fair

opportunity to demonstrate pretext." Burdine, 450 U.S., at

255-56. See also Aikens, 460 U.S. at 716 n.5 {quoting

Burdine, 450 U.S. at 256) (cautioning that "[o]f course, the

plaintiff must have an adequate ‘opportunity to demonstrate

that the proffered reason was not the true reason...’");

Patterson, 491 U.S., at 187 ("Although petitioner retains the

ultimate burden of persuasion, our cases make clear that she

must also have the opportunity to demonstrate that

respondent’s proffered reasons for its decision were not its

true reasons.")

The clarity of the proffered reasons is sharpened by

the additional requirement that, to be legally sufficient, the

employer’s explanations must be admitted into evidence; "the

defendant cannot meet its burden merely through an answer

to the complaint or by argument of counsel." Burdine, 450

U.S., at 255 n.9. Insofar as the relevant question is what

motivated the employer at the time of the action, there is no

reason to allow employers, after trial, to have a second bite

at the apple.

6Cf. Lankford v. Idaho, 500 U.S. ___, 114 L.Ed.2d 173 (1991)

(holding that capital defendant, in preparing for sentencing hearing,

did not have the notice required by due process that the judge might

sentence him to death based on facts in the trial record, when the

state had responded in the negative to the court’s earlier order

requiring it to reveal whether it would seek death).

27

The denial of an opportunity to rebut an explanation

is even more egregious when the explanation is first

"proffered" in the decision of the district court. In Lanphear

v. Prokop, 703 F.2d 1311 (D.C. Cir. 1983), the court of

appeals reviewed a decision in which the district court had

granted judgement for the defendant on a ground

completely different from that which the employer claimed.

Finding that the defendant’s omission of this reason failed

to meet the notice requirement of Burdine, Judge Wilkey,

writing for an unanimous court, held: "It should not be

necessary to add that the defendant cannot meet its burden

by means of a justification articulated for the first time in

the district court’s opinion." Id., 703 F.2d, at 1317 & n.39.7

Judge Wilkey summed up the fundamental flaw of

the district court’s sua-sponte defense:

The district court’s substitution of a

reason of its own devising for that proffered

by appellees runs directly counter to the

shifting allocation of burdens worked out by

the Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas and

Burdine. The purpose of that allocation is to

''Lanphear’s reasoning that a non-articulated reason cannot meet

the defendant’s step two burden is analytically consistent with the

presumption of discrimination that governs cases in which a

defendant articulated no reasons at all. In Uviedo v. Steves Sash &

Door Co., 738 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1984), the defendant had never

articulated reasons for its failure to promote plaintiff, despite its

argument on appeal that such reasons could be found in plaintiffs

witnesses’ testimony. The court of appeals found that even though

it was possible that these facts could be legitimate reasons, the

"difficulty" in this case was that "the defendant never articulated to

the magistrate that these were in fact the reasons for the particular

challenged action." Id., 738 F.2d, at 1429 (emphasis in original). The

court affirmed the district court’s finding of discrimination because

the defendant had failed to rebut plaintiffs prima facie case. Id. at

1430-31.

28

focus the issues and provide plaintiff with ‘a

full and fair opportunity’ to attack the

defendant’s purported justification. That

purpose is defeated if defendant is allowed to

present a moving target or, as in this case,

conceal the target altogether.

Lanphear, 703 F.2d, at 1316.

Other courts of appeals have recognized that

McDonnell Douglas precludes trial judges from crediting

speculative explanations never offered by a defendant. See,

e.g., Equal Employment Opportunity Comm’n v. West Bros.

Dept. Store, 805 F.2d 1171, 1172 (5th Cir. 1986) ("The trial

court may not assume this task [of articulating a legitimate

reason]; ‘[i]t is beyond the province of a trial or a reviewing

court to determine -- after the fact -- that certain facts in the

record might have served as the basis for an employer’s

personnel decision’.... We are concerned with what an

employer’s actual motive was; hypothetical or post hoc

theories really have no place in a Title VII suit."){quoting

Uviedo v. Steves Sash & Door Co., 738 F.2d 1425, 1430 (5th

Cir. 1984)); Jackson v. RKO Bottlers o f Toledo, Inc., 743 F.2d

370, 376 (6th Cir. 1984) (Trial court’s "finding" of an

instance of plaintiffs poor judgment was irrelevant, "since

defendant never claimed that the incident was a reason for

failing to promote plaintiff”);

B. Allowing the Defendant to Benefit from

Unarticulated Reasons by Escaping Scrutiny

for Pretext is Detrimental to Truth-Seeking

and Efficiency.

The clear articulation of an employer’s reasons, in

rebuttal to a plaintiffs prima facie case, helps narrow the

focus of the litigation. The burden-shifting process will flush

out, on plaintiffs rebuttal, relevant evidence about the

proffered reasons and best reveal whether a given answer is

29

true.8 Unarticulated reasons that are allowed to remain

hidden from the harsh light of this adversarial process

should not be given evidentiary weight. See Marina

Szteinbok, Indirect Proof o f Discriminatory Motive in Title VII

Disparate Treatment Claims after Aikens, 88 C o l u m . L. R e v .

1114, 1130-32 (1988) (allowing defendants to prevail on

unarticulated reasons "would distort the truth seeking

process by failing to test factual premises adversarially.")

In addition, crediting only those legitimate

nondiscriminatory reasons timely and clearly articulated --

and discrediting all others — acknowledges the superior

knowledge of the employer. The employer is in full control

of the knowledge and evidence of its actions. See Teamsters,

431 U.S., at 359 n.45. A judicial process unrelated to an

employer’s actual proffered explanations has none of the

indicia of reliability accorded to normal, adversarial

proceedings. Given the court’s customary reliance on a

litigant to select the interpretation of the facts most

favorable to his own case, to allow a fact finder to ascribe to

the employer reasons it did not articulate would jeopardize

the truth-seeking functions.

Respondent agrees that "Title VII does not compel

every employer to have good reasons for its deeds,"9 but

surely Title VII compels every employer to articulate what

those reasons are. "Ferreting out this kind of invidious

discrimination is a great, if not compelling, governmental

8"No better instrument has been devised for arriving at the truth

than to give a person in jeopardy of serious loss notice of the case

against him and opportunity to meet it." Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee

Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 171-72 (1951) (Frankfurter, J.)

9Pet. Br. at 21, quoting Benzies v. Illinois Dept, o f Mental Health

and Developmental Disabilities, 810 F.2d 146, 148 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied, 483 U.S. 1006 (1987).

30

interest," and it is reasonable and logical to place the burden

of articulating reasons for hiring decisions on defendant

employers. University o f Pennsylvania v. EEOC, 493 U.S.

182, 193 (1990) (unanimously holding that the EEOC may

subpoena peer review materials from a university in spite of

its common law, evidentiary, and First Amendment

objections).10

Petitioners present a litany of reasons that Title VII

defendants might prefer not to articulate. Pet. Br. at 18.

What Petitioners fail to provide is any explanation of why an

employer should be exempted from articulating those

reasons, however embarrassing or inconvenient, as

McDonnell Douglas requires. If employers could withhold

knowingly their real reasons with no fear of consequence,

even if a plaintiff proved its proffered reasons to be

pretextual, then the truth-seeking inquiry would cease to

have any meaning.11 This rule would create incentives that

are directly counter to the truth-seeking process.

Basic principles of evidence and common law waiver

support a policy of disallowing belated reasons. The

defendant is the master of his case and controls the evidence

relating to the real reasons for its actions. It fairly bears the

responsibility for its choices and the risk that plaintiff will

disprove any pretextual reasons and therefore prevail.

Where an employer deliberately chooses, for whatever

tactical or other reason, not to advance some additional

plausible justification for its actions, that waiver is binding

on the employer and court alike. See, e.g., Nation-wide

Check v. Forest Hills Distribs., 692 F.2d 214, 217 (1st Cir.

10Tactics less draconian than silence, such as protective orders,

may ameliorate employers’ concerns. See Fed . R. Civ. P. 26(c).

“Deliberately misleading the court with sham testimony in order

to meet the burden of production could, of course, risk other

penalties. E.g., 42 U.S.C. § 1621 (perjury).

31

1982) (iquoting Wigmore on Evidence § 291, at 228

(Chadbourn rev. 1979) that non-production of a relevant

document "‘is evidence from which alone its contents may be

inferred to be unfavorable to the possessor’"). See also

Michigan v. Lucas, 500 U.S. __ , 114 L.Ed.2d 205 (1991)

(statute requiring a rape defendant to file written notice and

an offer of proof regarding a prior relationship with alleged

victim within ten days of arraignment or risk possible

preclusion of that evidence did not per se violate the Sixth

Amendment, and might serve legislative ends, increase

evidence, and enhance fairness).

Finally, articulation of reasons by the employer

reduces the number of issues for the parties and fact finder,

which conserves resources while focusing the parties on the

most relevant issues. Petitioner argues that, in addition to

proof of pretext, it is the plaintiffs burden to "prove the

absence of any other justification supported by the record."

Pet. Br. 16. Petitioner would allow -- indeed, oblige -- the

finder of fact to consider not only the defendant’s articulated

reasons for its action and the plaintiffs allegation of a

discrimination, but also to consider and reject all conceivable

reasons that could have motivated the employer.

Petitioners’ approach would squander judicial

resources. All factual issues, even if vehemently denied by

all parties, would remain in play. The plaintiff and fact

finder would have to assume responsibility for extracting

from the record and resolving every conceivable reason for

the action. The courts would be plunged standardless into

a sea of defenses where every possible motivation and every

shred of indirect and direct evidence might matter,

multiplying litigation. This would be particularly ill-advised

just as Congress has provided a right to jury trials in Title

VII, see Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. 102-166 § 102(c),

32

105 Stat. 1073.12

C. The Confusion of the Present Record

Demonstrates Why Crediting Unarticulated

Reasons Undermines the Truth-Seeking

Function of the Adversarial Process.

The central factual question of this litigation is one

that Petitioners, three years after trial, still have not

answered: What in fact was the reason that Steve Long and

St. Mary’s Honor Center demoted and fired Melvin Hicks?

If Petitioners’ answer is that personal animosity of John

Powell was the reason, then Mr. Long and other defense

witnesses gave false testimony at the trial, yet now seek the

additional reward of escape from the judgment below. If

Petitioners’ answer is not John Powell’s personal animosity,

then Petitioners’ factual basis for defeating the inference of

discrimination dissolves.

The confusion in the factual record on which this

petition rests — illustrates the danger of bypassing

McDonnell Douglas' requirement of producing sufficient

notice of the employer’s reasons for its actions. Had the

reason found by the district court been timely articulated by

Petitioners, there is no doubt that the trial below would have

been completely different.

The district court found that:

It is clear that John Powell had placed

plaintiff on the express track to termination.

It is also clear that Powell received the aid of

Ed Ratliff and Steve Long in this endeavor.

The question remains, however, whether

12One can imagine the chaos if each juror, each on the basis of a

different speculative reason, found for a defendant.

33

plaintiffs race played a role in their

campaign.

Pet. App. A-26. Of course, the question that the district

court posed probably would have been answered during the

trial had the Petitioners ever expressed that Powell’s

personal animosity or his endeavors against the plaintiff

were the reason for their actions.

However, Respondent had no notice that Petitioners,

much less the trial judge, might suggest that personal, rather

than racial, animosity motivated them.13 Certainly the

testimony would not suggest that Petitioners would defend

the charges on that ground. John Powell flatly denied any

personal difficulty with Melvin Hicks: "I can’t say that there

was difficulties between he and I. At no time was there any

kind of personal —" J.A. 46.

More importantly, Petitioners never claimed that any

decisionmaker had personal animus or took Powell’s

purported animosity into account in demoting or discharging

the Respondent. Vincent Banks, a member of the

disciplinaiy committee that had recommended suspension

when Respondent was terminated, did not mention any

animus of Powell, himself, or the other committee members.

Tr. 3-2 to 3-51. Similarly, Petitioner Long did not mention

any animosity by Powell - or himself - towards Respondent,

13With proper notice, Respondent could have examined whether

the "crusade" that the district court found against Hicks was "racially

rather than personally motivated," Pet. A-27, and could have explored

the extent to which the personal animosity was related to

Respondent’s race. With fair notice and opportunity to prove his

case, Respondent could have investigated the actions of Powell and

the actions and motivations of other white men who the court found

assisted him -- Ed Ratliff and Petitioner Long. Respondent could

have discovered whether other "crusades" were carried on against

other supervisors and officers at St. Mary’s.

34

and claimed that Respondents’ history of infractions

motivated him, a reason found incredible by the district

court.* 13 14

Five months after trial, Respondents’ counsel, Gary

Gardner, summarized defendants’ position consistent with

their trial testimony. Defendants’ Proposed Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law (Nov. 30, 1989). Not one of the 41

proposed findings or conclusions allege that any of the

defendants harbored personal animus toward Mr. Hicks. Id. ,

1-13.15 Similarly, in the court of appeals, Petitioners

reported that they had "adduced evidence of legitimate, non-

discriminatory reasons for Hick’s demotion and discharge,

14The Director of the Division of Adult Institutions, Donald

Wyrick, who would make the final discharge decision, did not testify

at all.

13The proposed conclusions regarding defendants’ burden read in

full:

"Defendants produced evidence, however, of legitimate

and nondiscriminatory reason [sic] for each of their

employment decisions, the shift change, suspension,

demotion and dismissal. The shift change was ordered to

broaden the experience of plaintiff, the suspension was order

as a result of plaintiffs not performing his duties as shift

commander on March 3, 1984, to have the front officer at

this post, to have the roving patrol officer make periodic

reports, and to keep the visiting areas lights on. The

demotion was order as a result of plaintiff not ensuring on

March 17, 1984 that the use of a state vehicle, and the

purpose of its use, was logged in the vehicle control and shift

chronological logs. The dismissal was ordered as a result of

plaintiff offering violence to his commanding officer on April

27, 1984, by inviting him to step outside. Though plaintiff

denied such an offer, the encounter between plaintiff and his

commanding officer was witnessed by a third employee, who

testified that plaintiff used words to that effect." Defendants’

Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 14-15

(Nov. 30, 1989).

35

which were the severity and accumulation of violations of

institutional rules," while they stated that the trial court had

found John Powell’s personal animosity. Hicks v. St. Mary’s

Honor Center, 91-1571, Brief of Appellees 3, 15 (Aug. 16,

1991).

In light of the fact that Long, Banks and Wyrick,

made the critical decision, and all of their claimed reasons

for the actions at issue were found to be pretextual, it is

difficult to understand how petitioner can be exonerated on

the assumption that Powell had a grudge against

Respondent. Respondent, of course, had no notice that the

relationship of Powell to these decisionmakers would be at

issue.

In any event, Powell’s personal animosity, otherwise

unexplained, is not mutually exclusive of racial

discrimination. Indeed, courts recognize that it is often the

very expression of discriminatory motive. Cf. Miles v. M.N.C.

Corp., 750 F.2d 867, 871-72 (5th Cir. 1985) ("subjective

evaluations involving white supervisors provide a ready

mechanism for racial discriminatiort. This is because the

supervisor is left free to indulge a preference, if he has one,

for one race of workers over another").16

This undeveloped record turns the factual inquiry of

McDonnell Douglas on its head: Petitioners themselves lead

the rebuttal of the reason ascribed to them by the district

court. This vague, post-hoc reason cannot, as a matter of

law, serve to rebut Respondent’s prima facie case evidence

16The court of appeals did question "whether such a hypothetical

reason based upon personal motivation even could be stated and still

be ‘legitimate’ and ‘nondiscriminatory.’" Because the court of appeals

found that defendants did not meet Burdine’s requirement of a clear

articulation with regard to this reason, it found no reason to resolve

this question. A-10.

36

of discrimination.17

III. ADOPTION OF THE "PRETEXT PLUS" RULE

WOULD REQUIRE DIRECT PROOF OF

DISCRIMINATORY MOTIVE.

At the heart of the McDonnell Douglas/Burdine model

is the principle that intentional discrimination can be

established indirectly through circumstantial evidence, and

does not require direct proof of motive. The "pretext plus"

rule urged by petitioners and adopted by the First, Sixth,

and Seventh Circuits undermines this principle.

Petitioners, their amici and, indeed, the courts that

have adopted pretext plus are notably reticent in explaining

precisely what kind of evidence a plaintiff must introduce in

order to establish the "plus." Their position is clearly that

proving pretext, that is, that the reasons offered are not the

true reasons, is insufficient. It is necessary to adduce some

additional quantum of evidence to establish that the pretext

was advanced for the purpose of discrimination.

Respondent urges that the reticent is not inadvertent; it is

clear that the inevitable consequence of adopting the

"pretext plus" rule is to require direct evidence of

discriminatory motive.18

17If, contrary to the opinion below, personal animosity in this case

is held to be legally relevant, then remand for review of this factual

finding would be necessary. The court of appeals characterized the

district court’s view of the motivations as an "assumption" without

evidence to support it. A-10.

lBSee generally, Catherine Lanctot, The Defendant Lies and the

Plaintiff Loses: The Fallacy of the ‘Pretext-Plus’ Rule in Employment

Discrimination Cases, 43 Hastings LJ. 57, 99 (1991). Lanctot notes

that some pretext-plus courts have usurped the role of the fact finder

in determining the credibility and weight of statements, and have kept

37

As discussed in Part I, supra, Burdine holds that a

plaintiff may demonstrate pretext "either directly by

persuading the court that a discriminatory reason more likely

motivated the employer or indirectly by showing that the

employer’s proffered explanation is unworthy of credence."

450 U.S. at 256 (emphasis added). Respondent maintains

that Burdine’s use of the disjunctive, on its face, means

simply that a plaintiff may discharge his ultimate burden of

persuasion by proof of either of the stated options. That is,

a plaintiff may prove directly that discrimination was the

motive, or may, to equal effect, demonstrate discrimination

indirectly by proving that the stated reasons are themselves

not credible. Thus, for the reasons discussed above at

length, proof of pretext without more discharges the

plaintiffs ultimate burden of persuasion, and compels

judgment for him.

Petitioner and their amici, in contrast, deny that

rebuttal of the employer’s articulated reasons is necessarily

sufficient to discharge plaintiffs burden of persuasion. Their

argument necessarily negates the second part of the Burdine

rule as an alternative method of proceeding, and submerges

it into the first method of proving pretext, namely through

direct evidence of motive. Imposing an utterly new

requirement of some undefined additional proof of

discrimination onto the final step of the McDonnell

Douglas!Burdine test, would effectively overrule the entire

line of McDonnell Douglas cases. Thus, the reach of Title

VII would be limited to only the most blatant "smoking gun"

violations.